Abstract

Oligomerization is a general characteristic of cell membrane receptors that is shared by G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) together with their G protein partners. Recent studies of these complexes, both in vivo and in purified reconstituted forms, unequivocally support this contention for GPCRs, perhaps with only rare exceptions. As evidence has evolved from experimental cell lines to more relevant in vivo studies and from indirect biophysical approaches to well defined isolated complexes of dimeric receptors alone and complexed with G proteins, there is an expectation that the structural basis of oligomerization and the functional consequences for membrane signaling will be elucidated. Oligomerization of cell membrane receptors is fully supported by both thermodynamic calculations and the selectivity and duration of signaling required to reach targets located in various cellular compartments.

Keywords: G protein-coupled receptors, phototransduction, rhodopsin, G protein, membrane receptors, signal transduction, hormone

Historical perspectives of G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) organization

Like other membrane receptors G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) exist in various oligomeric forms. Not only monomers, but also dimers and higher-order oligomers of GPCRs are assembled into stable and transient homo-oligomeric and hetero-oligomeric macromolecular structures that can accommodate up to 500 receptors. Encoded by about 800 genes in the human genome, GPCRs constitute a critical set of seven-transmembrane spanning proteins involved in nearly all physiological processes from sensory transduction to hormonal signaling. GPCRs are traditionally grouped into five major sub-family types based on their conserved primary sequences and overall topology 1. Activation of a GPCR triggers coupling with heterotrimeric GTP-binding proteins (G proteins) which then that promotes further downstream signaling 2, 3. Loose association of these different proteins can even take place before GPCR activation. Despite the high quality of original data concerning the oligomerization of GPCRs and G proteins 3, including disulfide-linked metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 dimers 4, it was long thought that GPCRs exist as monomeric units that undergo a large 10–15 Å conformational change upon activation before specifically coupling via intracellular loops to G proteins 5. Several undisputed observations, illustrated by studies of the retinal photoreceptor GPCR rhodopsin, indicated that a single photon that activated just one out of 108 receptor molecules could produce a reliable electrophysiological signal that was transmitted to secondary neurons 6. Moreover, theoretical models indicated that proper signaling requires monomeric and mobile receptors. However, the idea of unrestricted mobility of rhodopsin was decisively laid to rest recently by more precise experiments 7. Interestingly, activation of one rhodopsin molecule can trigger “high-gain” phosphorylation by a receptor kinase, wherein many un-illuminated rhodopsin molecules become phosphorylated 8. Further support comes from 2D crystals of rhodopsin, which form a two-dimensional lattice 9, indicating a preference of this receptor for high density packing similar to that seen in photoreceptors 10, 11. Additionally, many other features of GPCR signaling have emerged that argue against strictly monomeric GPCR signaling in vivo. One subtle observation is that the structures of GPCRs and G proteins are highly homologous, a finding which strongly implies that the mechanisms of activation are likely to be conserved among this family of receptors and their intrinsic coupling proteins. Significantly, fluorescent and bioluminescence energy transfer experiments in experimental cell lines also indicate dimerization or oligimerization for multiple membrane-bound GPCRs (reviewed in 12, 13).

The eminent German thinker Arthur Schopenhauer (1788 – 1860) wrote with philosophical clarity that all truth passes through three stages. First, it is ridiculed. Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as being self-evident. These observations aptly apply to GPCRs: an understanding of their oligomerization has evoked much passion and continuing investigation. We are now in an era in which oligomerization of biologically relevant GPCRs and the importance of this phenomenon is rapidly becoming ‘self evident’. Even so, solid experimental evidence obtained by multiple approaches must prevail before a scientific concept can be widely accepted.

The last decade has provided significant findings that make rethinking the role of dimerization/oligomerization mandatory for all researchers in the field of GPCR signaling. Here, because of space limitations, I summarize some recent scientific contributions that inspire me most. The focus is on critical results achieved by direct high-resolution methods and experimental findings obtained under physiological conditions. Progress in this field is so rapid that some statements in this review will undoubtedly require modification in the near future.

Imaging of GPCR clustering

The most direct approach to the oligomerization issue would be to observe clustering of GPCRs in native biological tissues directly by sensitive methods at sufficient resolution. This strategy successfully revealed cone pigments (rhodopsin homologs) in photoreceptor cells by X-ray diffraction. Corless and colleagues found that membrane-bound crystals form in cone cells when frog retinas are exposed to light 14. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) revealed para-crystalline patches within carefully isolated fresh disks from photoreceptors of mouse retina, wherein the building blocks consisted of rhodopsin dimers 10, 11. A symmetrical organization of rhodopsin also was imaged by electron microscopy 15, 16 and confirmed by various biochemical methods 17. Pezacki and colleagues, using near-field scanning optical microscopy of cardiac myocytes in situ, found nanoscale multiprotein complexes called signalosomes that contained a high density of β-adrenergic receptors that were most abundant in caveolae (Latin: ‘little caves’) 18. These invaginations are about 1000 Å across, and can accommodate a maximum of about 30×30 GPCRs because the area occupied by a single GPCR on the G protein-interacting surface is ~1,500 Å2. Although these imaging techniques are hardly accessible to all laboratories, their use for observing these structures in their natural environment is of paramount importance.

Functional evidence of GPCR oligomerization in vivo

A large number of direct binding assays indicating negative or positive cooperativity suggest clustering of GPCRs and/or G proteins; however the reproducibility and interpretations of the data varied from one laboratory to another. Although this approach clearly advanced the field, it was hardly free of over-interpretation 12, 13. Help in resolving the function of oligomerization arrived in the form of an absolute requirement for some receptors to heterodimerize. These include GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) receptors 19–21, and the taste receptors, umami (T1R1 +T1R3), sweet (T1R2 +T1R3) and bitter consisting of about 30 different types 22. The crystal structure of the extracellular ligand-binding region of metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR1) displayed disulfide-linked homodimers in active and resting conformations modulated through the dimeric interface 23. It was speculated that movements of four domains in the dimer lead to activation of the receptors sensed at intracellular regions 24.

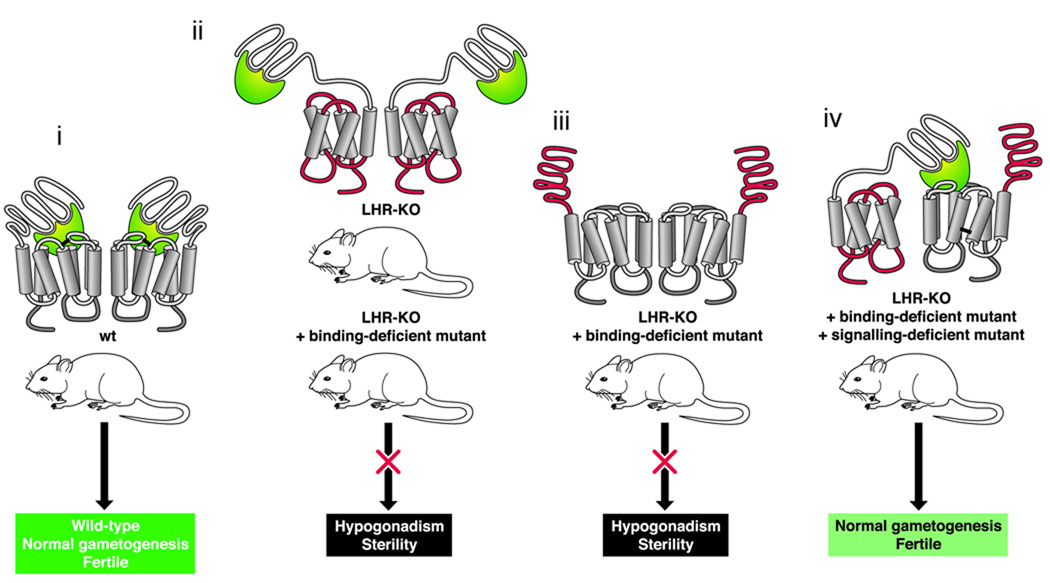

Rather than employing a quicker approach with experimental cell lines, Rivero-Müller et al. took a more definitive step toward demonstrating a requirement for oligomerization of family A (rhodopsin-like) GPCRs by using time-consuming, labor-intensive and expensive experiments involving transgenic mice to set a new standard for the field 25. In this elegant study, the mouse luteinizing hormone receptor (LHR) served as a model GPCR, and the authors demonstrated that transgenic mice co-expressing binding-deficient and signaling-deficient forms of LHR could reestablish normal LH actions through intermolecular functional complementation of the mutant receptors in the absence of functional wild-type receptors (Fig. 1). These results provide the clearest in vivo evidence for the physiological relevance of intermolecular functional cooperation in GPCR homodimerization. Hopefully this and complementary approaches will inspire similar experiments that will provide additional insights into the physiological roles of GPCR oligomerization. Because a large portion of the LHR sequence was removed to create the signaling-null mutant of this receptor, one concern might be the integrity of the structure of the assembled protein that results when two trans-helical segments are missing. A counter point can be made that fragments of a GPCR can fold properly, as demonstrated by Ridge and colleagues for rhodopsin 26. Perhaps future experiments will be designed wherein more subtle changes in the receptor might be used to preserve the topology of the mutant protein.

Figure 1.

In vivo dimerization of the luteinizing hormone receptor (LHR). This drawing depicts intermolecular cooperation of two molecules of the receptor. In wild-type mice (i), a signal is generated when hormone binds to the receptor and animals undergo normal gonadogenesis and are fertile. Mice with a knockout of the gene encoding LHR, or transgenic mice expressing a mutant LHR that cannot signal through G proteins because one of the transmembrane helices and two loops (residues 553–689) (ii) were eliminated, developed hypogonadism and sterility. Similarly, transgenic mice lacking the capability of binding luteinizing hormone because of mutations affecting the ectodomain (iii) also developed hypogonadism and sterility. However, when the binding- and signaling-deficient LHR mutants were cross-bred (iv), their offspring displayed partially-restored signaling and were fertile. Figure based on 25,

Biochemical and structural evidence of GPCR oligomerization

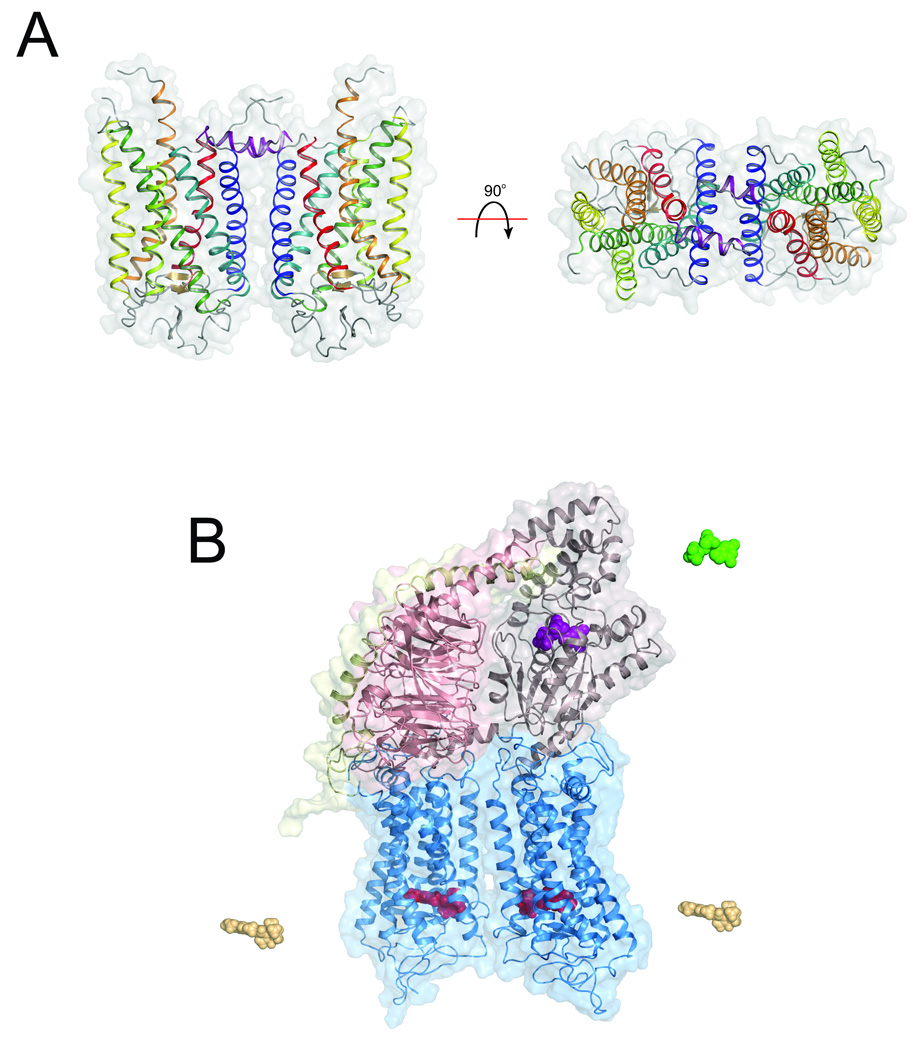

Arguably, crystallographic studies can provide additional evidence for the propensity of GPCRs to oligomerize. Rhodopsin oligomerizes in a non-physiological anti-parallel orientation in crystals 27, but can realign appropriately under different conditions 28. Thus, different solvents used for crystallization of these receptors can influence the orientation of monomers and their assembly. Oligomers were also found in crystals of engineered human β2-adrenergic receptor 29 and an engineered human A2A adenosine receptor 30. Obviously, crystallization per se brings proteins close together to form a crystal lattice, but the special orientation of monomeric units in the above cases cannot be ignored because of their crystalline 2D orientation in experimental membranes 9. In addition, crystal structures of extracellular domains clearly demonstrate dimerization that likely extends over the entire length of the receptor 23, 31. These studies contrast with others demonstrating the ability of monomeric GPCRs to activate G proteins. Such activation was observed within high-density lipoprotein particles (nano-discs) for several receptors including the β2-adrenergic receptor 32 and rhodopsin 33, 34 (Fig. 2A). However, if such monomeric units do not or rarely exist in vivo, the main value of these experiments is the demonstration that activation determinants are present in GPCR monomers. However, it is also possible to over-interpret these results because they are similar to those obtained by using several peptides for in vitro activation of heterotrimieric G proteins. By contrast, the dimer function can be visualized by fluorescence protein-fragment complementation, in which, for example, green fluorescent protein is split and each fragment is separately fused to a GPCR. Fluorescence would not emanate from the individual fragments, but only when two GPCRs come together to form a fluorescent product. Typically, the fluorescence background is very low and non-interacting receptors can be used as controls. This elegant approach was used to demonstrate that one G protein interacts with two GPCRs 35. It would be timely to see this technique employed in transgenic mice. Indeed, when combined with fluorescent tagging and deeply penetrating techniques of two-photon microscopy, the life cycle of GPCRs could potentially be monitored in the truly physiological setting of a transgenic mouse.

Figure 2.

Structural models of rhodopsin and its G protein. A. Atomic structure of dimeric forms of the prototypical GPCR, photoactivated rhodopsin. (i) The region above the receptor is the cytoplasmic face and below is the extracellular domain (PDB ID codes 2I35) 28. Helices are colored according to their primary sequence: helix-I, blue; helix-II, blue-green; helix-III, green; helix-IV, lime-green; helix-V, yellow; helix-VI, orange; helix-VII, red; cytoplasmic helix-8, purple. (ii) The cytoplasmic surface of the dimeric photoactivated rhodopsin in the crystal is shown. B. Schematic representation of the complex between photoactivated rhodopsin and Gt. Light illumination triggers structural changes in rhodopsin and promotes binding of Gt to the photoactivated rhodopsin/rhodopsin dimer. Activation of one rhodopsin subunit in the dimer is enough to induce Gt association, which stimulates GDP (green) release from the Gt nucleotide-binding pocket. This results in formation of the photoactivated rhodopsin-Gte complex with a free nucleotide-binding pocket. However, loading of GTP (not shown) causes complex dissociation. Photoactivated rhodopsin-Gte is amenable to ligand removal (all-trans-retinylidene chromophore depicted as a yellow structure) without dissociation of this complex exemplified by the empty chromophore-binding pocket and an empty nucleotide-binding pocket in opsin-Gte. The opsin-Gte complex can be regenerated with 11-cis-retinylidene (red) resulting in Rho-Gte complex without Gt dissociation. Only GTP breaks this complex once it is formed, suggesting high plasticity of the activated receptor and a complex that, once formed, becomes independent of the activating ligand.

Biochemical experiments have revealed other important findings relevant to GPCR oligomerization. For example, in detergent extracts, GPCRs can come together in the presence of lipids 36. Biochemical data also suggest another important property of GPCR oligomerization, namely that the two monomers comprising a GPCR dimer could be non-equivalent thereby allowing more refined regulation of GPCR activity37, 38. If this observation holds true under in vivo conditions, as it does for sub-family C GPCRs, it would indicate maximal GPCR signaling generated by single occupancy of a GPCR dimer with a full agonist at low to intermediate concentrations, lower signaling conferred by double occupancy of the dimer with the same agonist, and basal signaling activity in the absence of agonist. The complexity of functional consequences of GPCR oligomerization was revealed recently based on elegant crystallographic studies of the extracellular domain of the parathyroid hormone receptor (PTH1R), a class B GPCR. The results indicate that PTH1R forms constitutive dimers that are dissociated by ligand binding and that monomeric PTH1R is capable of activating G proteins 36. The activity of this GPCR stands at odds with other receptors, and so physiological evaluation of this mechanism will be essential.

Biochemical isolation of GPCR–G protein complexes

Ultimately, we must determine the structure of the fully activated receptor–G protein complex. Is it the receptor dimer with one monomer occupied by agonist? Is there an assembly of different conformations that would allow flexibility of GPCRs poised to pair with G proteins? How does a G protein affect the structure of a GPCR? Perhaps much to the surprise of those not directly investigating GPCR signaling, very little preliminary work has been done to characterize GPCR–G protein complexes, and most of this has concerned G protein activation readout, G protein association with membranes, immobilized receptors and similar topics. It was not until Jastrzebska developed several methods of reconstituting and assembling the G protein transducin with photoactivated rhodopsin in detergent solutions 39 that several important observations emerged: (i) the complex readily breaks apart into transducin’s individual α- and βγ-subunits along with different forms of rhodopsin; (ii) heterogeneous reconstitution occurs, but at very low yields; (iii) the most stable and homogeneous complex was isolated from membranes by simple solubilization with dodecyl-β-maltoside, suggesting that the natural membrane environment is critical for proper complex formation; and (iv) once the complex between photoactivated rhodopsin–transducin is formed, the GDP nucleotide can dissociate from the G protein without disrupting the complex. The last finding agrees with several studies involving membranes, wherein the chromophore, all-trans-retinal, can be removed from opsin, which in turn can be regenerated with another 11-cis-retinal molecule without breaking the complex. Moreover, (v) the GTP nucleotide can dissociate from the G protein in these preformed complexes, suggesting the presence of a competent interface between receptor and G protein (Fig. 2B). Further progress will require crystallizing entire GPCR–G protein complexes and analyzing them by high resolution methods.

Hetero-oligomerization of GPCRs

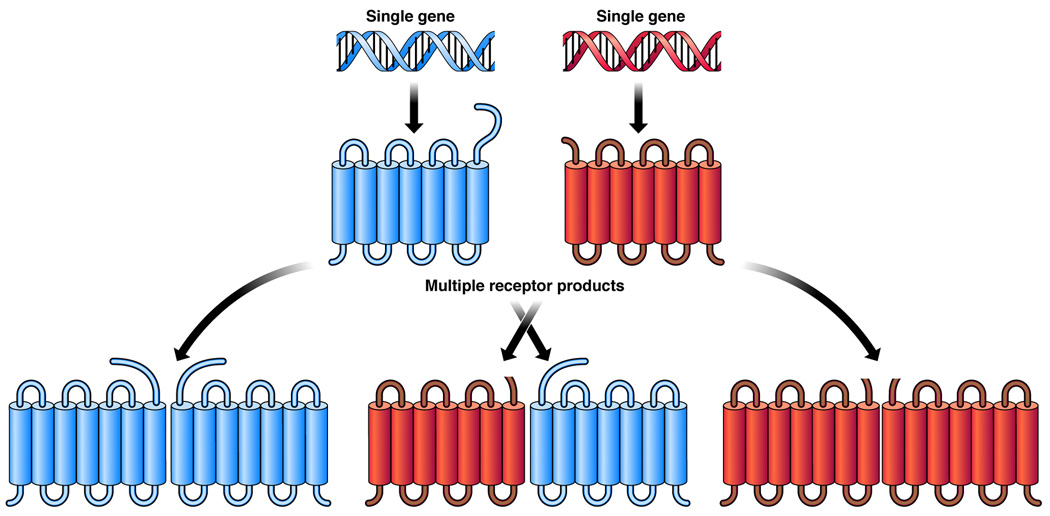

An interesting aspect of GPCR dimerization is that these receptors can form heterodimers as well as homodimers 40 with many dimers displaying modified pharmacology 41, altered responsiveness to viral entry through GPCRs 42, or attenuated signaling 43. The best known examples of heterodimer formation include the above-mentioned taste receptors and the GABA hetero-receptor complex, but many pairs of co-expressed GPCRs reciprocally modulate each other’s function, pharmacology and cellular biology. Therefore, it is apparent that the oligomeric potential of GPCRs allows further diversification of their repertoire as a result of more complex ligand–receptor relationships than envisioned for monomeric receptors (Fig. 3). Such heterodimerization has the potential to answer the pharmacological complexity observed in a number of cases involving native tissues derived from different organs, where one GPCR signals and the second forms a platform for G protein docking 24, 44. Salim et al. have clearly demonstrated that many family A GPCRs have a propensity to form oligomers in co-transfected experimental cell lines 45. Therefore, it will be critical to further investigate such heterodimerization under more physiological conditions, in cells in which they are endogenously expressed. Like many other issues in science, reproducibility by independent laboratories is also important. Filizola 46 developed and organized a database that can be very useful in disseminating information about homodimerization and heterodimerization of GPCRs.

Figure 3.

Diversity through oligomerization. A combination of functional receptor units can include homo-oligomers of a single gene product and hetero-oligomers of multiple gene products with unique physiological/signaling properties.

Theoretical and thermodynamic considerations about GPCR oligomerization

Considering the massive number of GPCRs within many different species, direct approaches will not soon yield a molecular understanding of exactly how high resolution experimental 3D models might be organized within membranes. But sophisticated computational approaches and molecular dynamic methods will play a vital role in generating new hypotheses and structural models that can be experimentally tested on a selective basis. The dynamics of these systems can also be approximated by computational methods44, 47. For example, we described how a G protein might dock onto an oligomeric GPCR, providing a mechanistically testable idea of how signal transduction involving these critically important proteins occurs 44.

Many GPCRs demonstrably have the propensity to self-assemble by forming dimers or higher-order oligomers. These membrane proteins can form specific homo- and hetero- oligomers not only because they have an intrinsic affinity for each other, but also because the energetically favorable exposure of ionizable residues to phospholipids promotes their oligomerization. We calculated that such aggregation would be prevented only if the thermal energy (0.8–1 kcal/mol at physiological temperatures) exceeded the energetic gain resulting from association 48. It is also important to remember that movement of membrane proteins is restricted in a more or less 2 dimensional environment. Such a restriction could be further amplified by the presence of caveolae and other membrane structures as well as by specific and non-specific phospholipid interactions. Considering all these factors, association of membrane proteins would be enhanced by orders of magnitude relative to soluble proteins because of the reduced freedom of movement conferred by the cellular membrane. GPCRs do not need to associate permanently 49; they need only to form transient higher-order structures for sufficient time to allow G protein coupling. Indeed, monomeric GPCRs and other membrane proteins cannot move freely without continuous exposure to energetic traps that involve transient or stable oligomerization/association. Clustered receptors would also act like a trap to retain agonist and induce activation, especially at very low agonist concentrations. Rapid rebinding of dissociated ligand with multiple activations would ensure that signaling is propagated. Calculations from studies in an experimental cell line indicate that the mean lifetime of a M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor dimer is 0.5 s 50 (for further reading about the transient nature of GPCR oligomerization, see 51).

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

It is fascinating to consider how the GPCR field has expanded since Rodbell’s and Gilman’s seminal discoveries 2, 3. Tedious cloning of one receptor at a time was quickly replaced by massive genome-wide sequencing of GPCRs and G proteins from many organisms. The availability of animal models with naturally occurring mutations and the generation of mice with specific genetic defects now allows biochemical assays to be performed within discrete pathophysiological frameworks. New high resolution imaging methods have opened up the possibility of studying the molecular events of signal transduction in physiological settings, and structural methods are continuously improving, allowing the acquisition of atomic information about the ‘hard to over-estimate group’ of enzymes, receptors and modulating proteins engaged in GPCR signaling. However, there are several important problems that can be addressed in the very near future, include:

Solving the structures of unmodified, non-rhodopsin GPCRs. Structural information gained from current GPCRs can be used to design both novel orthologs that occupy agonist binding sites and allosteric ligands that indirectly influence these sites.

Solving, at least at low resolution, the structure of a GPCR–G protein complex. This low resolution achievement will allow well-characterized high quality material to be prepared for high resolution crystallization methods. Solving the complex structure is essential for understanding the agonist-activated structures.

Studying GPCR oligomerization in vivo by using transgenic animal models. Work in experimental cell lines can generate initial possible models, but final proof requires systems located in their proper physiological environment.

Determining the impact of oligomerization on GPCR–G protein complex function so that computational methods can be used to generate initial hypotheses focused on understanding appropriate experimental systems. Theoretical estimates affecting issues such as stability and re-organization must be considered experimentally.

Improving in vivo imaging methods constitutes a high priority so that biochemistry can be observed in physiological settings at a sub-cellular level or individual protein level. Such methods could almost immediately be applied in tadpoles and zebrafish, at least for studying rhodopsin signaling in combination with multi-photon microscopy.

The functional consequences of GPCR oligomerization should also be considered in a broader context than ligand binding and G protein signaling because cell biological events are more complex than those simply emanating from receptor activation, desensitization and recycling. Oligomerization could affect the efficacy and rates of these events. High quality research geared toward answering these important biological questions would be highly desirable.

So, let’s get to work…

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Leslie T. Webster, Jr. (Case Western Reserve University) for valuable comments on the manuscript. This work was supported in part by NIH grants R01-EY0008061, and GM079191. KP is a Senior Fellow of the American Asthma Foundation and Sandler Program for Asthma Research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kobilka BK. G protein coupled receptor structure and activation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:794–807. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilman AG. G proteins: transducers of receptor-generated signals. Annual review of biochemistry. 1987;56:615–649. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.003151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodbell M. The role of hormone receptors and GTP-regulatory proteins in membrane transduction. Nature. 1980;284:17–22. doi: 10.1038/284017a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Romano C, et al. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 is a disulfide-linked dimer. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28612–28616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farrens DL, et al. Requirement of rigid-body motion of transmembrane helices for light activation of rhodopsin. Science. 1996;274:768–770. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baylor DA, et al. Responses of retinal rods to single photons. J Physiol. 1979;288:613–634. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Govardovskii VI, et al. Lateral diffusion of rhodopsin in photoreceptor membrane: a reappraisal. Molecular vision. 2009;15:1717–1729. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Binder BM, et al. Phosphorylation of non-bleached rhodopsin in intact retinas and living frogs. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19826–19830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.19826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krebs A, et al. Characterisation of an improved two-dimensional p22121 crystal from bovine rhodopsin. Journal of molecular biology. 1998;282:991–1003. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fotiadis D, et al. Atomic-force microscopy: Rhodopsin dimers in native disc membranes. Nature. 2003;421:127–128. doi: 10.1038/421127a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fotiadis D, et al. The G protein-coupled receptor rhodopsin in the native membrane. FEBS letters. 2004;564:281–288. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00194-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bouvier M. Oligomerization of G-protein-coupled transmitter receptors. Nature reviews. 2001;2:274–286. doi: 10.1038/35067575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park PS, et al. Oligomerization of G protein-coupled receptors: past, present, and future. Biochemistry. 2004;43:15643–15656. doi: 10.1021/bi047907k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corless JM, et al. Three-dimensional membrane crystals in amphibian cone outer segments: 2. Crystal type associated with the saddle point regions of cone disks. Experimental eye research. 1995;61:335–349. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(05)80128-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liang Y, et al. Organization of the G protein-coupled receptors rhodopsin and opsin in native membranes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:21655–21662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302536200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang Y, et al. Rhodopsin signaling and organization in heterozygote rhodopsin knockout mice. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48189–48196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408362200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suda K, et al. The supramolecular structure of the GPCR rhodopsin in solution and native disc membranes. Mol Membr Biol. 2004;21:435–446. doi: 10.1080/09687860400020291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ianoul A, et al. Imaging nanometer domains of beta-adrenergic receptor complexes on the surface of cardiac myocytes. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:196–202. doi: 10.1038/nchembio726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones KA, et al. GABA(B) receptors function as a heteromeric assembly of the subunits GABA(B)R1 and GABA(B)R2. Nature. 1998;396:674–679. doi: 10.1038/25348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuner R, et al. Role of heteromer formation in GABAB receptor function. Science. 1999;283:74–77. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5398.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White JH, et al. Heterodimerization is required for the formation of a functional GABA(B) receptor. Nature. 1998;396:679–682. doi: 10.1038/25354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yarmolinsky DA, et al. Common sense about taste: from mammals to insects. Cell. 2009;139:234–244. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kunishima N, et al. Structural basis of glutamate recognition by a dimeric metabotropic glutamate receptor. Nature. 2000;407:971–977. doi: 10.1038/35039564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kubo Y, Tateyama M. Towards a view of functioning dimeric metabotropic receptors. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rivero-Muller A, et al. Rescue of defective G protein-coupled receptor function in vivo by intermolecular cooperation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:2319–2324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906695106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ridge KD, et al. In vivo assembly of rhodopsin from expressed polypeptide fragments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92:3204–3208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palczewski K, et al. Crystal structure of rhodopsin: A G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2000;289:739–745. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salom D, et al. Crystal structure of a photoactivated deprotonated intermediate of rhodopsin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:16123–16128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608022103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cherezov V, et al. High-resolution crystal structure of an engineered human beta2-adrenergic G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2007;318:1258–1265. doi: 10.1126/science.1150577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jaakola VP, et al. The 2.6 angstrom crystal structure of a human A2A adenosine receptor bound to an antagonist. Science. 2008;322:1211–1217. doi: 10.1126/science.1164772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pioszak AA, et al. Structural basis for parathyroid hormone-related protein binding to the parathyroid hormone receptor and design of conformation-selective peptides. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:28382–28391. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.022905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whorton MR, et al. A monomeric G protein-coupled receptor isolated in a high-density lipoprotein particle efficiently activates its G protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:7682–7687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611448104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whorton MR, et al. Efficient coupling of transducin to monomeric rhodopsin in a phospholipid bilayer. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:4387–4394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703346200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bayburt TH, et al. Transducin activation by nanoscale lipid bilayers containing one and two rhodopsins. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:14875–14881. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701433200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vidi PA, Watts VJ. Fluorescent and bioluminescent protein-fragment complementation assays in the study of G protein-coupled receptor oligomerization and signaling. Molecular pharmacology. 2009;75:733–739. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.053819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mansoor SE, et al. Rhodopsin self-associates in asolectin liposomes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:3060–3065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511010103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rovira X, et al. The asymmetric/symmetric activation of GPCR dimers as a possible mechanistic rationale for multiple signalling pathways. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arcemisbehere L, et al. Leukotriene BLT2 receptor monomers activate the G(i2) GTP-binding protein more efficiently than dimers. J Biol Chem. 285:6337–6347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.083477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jastrzebska B, et al. Isolation and functional characterization of a stable complex between photoactivated rhodopsin and the G protein, transducin. FASEB J. 2009;23:371–381. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-114835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Milligan G. G protein-coupled receptor hetero-dimerization: contribution to pharmacology and function. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:5–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00169.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maggio R, et al. Heterodimerization of dopamine receptors: new insights into functional and therapeutic significance. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009;15 Suppl 4:S2–S7. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(09)70826-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vischer HF, et al. Viral hijacking of human receptors through heterodimerization. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;377:93–97. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.09.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang M, et al. A cell surface inactive mutant of the human lutropin receptor (hLHR) attenuates signaling of wild-type or constitutively active receptors via heterodimerization. Cell Signal. 2009;21:1663–1671. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Filipek S, et al. A concept for G protein activation by G protein-coupled receptor dimers: the transducin/rhodopsin interface. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2004;3:628–638. doi: 10.1039/b315661c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salim K, et al. Oligomerization of G-protein-coupled receptors shown by selective co-immunoprecipitation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:15482–15485. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201539200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Skrabanek L, et al. Requirements and ontology for a G protein-coupled receptor oligomerization knowledge base. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:177. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Filizola M. Increasingly accurate dynamic molecular models of G-protein coupled receptor oligomers: Panacea or Pandora's box for novel drug discovery? Life Sci. 2009;86:590–597. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Muller DJ, et al. Vertebrate membrane proteins: structure, function, and insights from biophysical approaches. Pharmacol Rev. 2008;60:43–78. doi: 10.1124/pr.107.07111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fonseca JM, Lambert NA. Instability of a class a G protein-coupled receptor oligomer interface. Molecular pharmacology. 2009;75:1296–1299. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.053876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hern JA, et al. Formation and dissociation of M1 muscarinic receptor dimers seen by total internal reflection fluorescence imaging of single molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107:2693–2698. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907915107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lambert NA. GPCR dimers fall apart. Sci Signal. 3:pe12. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3115pe12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]