Abstract

Rationale

Nitro-oleic acid (OA-NO2) is a bioactive, nitric-oxide derived fatty acid with physiologically relevant vasculo-protective properties in vivo. OA-NO2 exerts cell signaling actions due to its strong electrophilic nature, and mediates pleiotropic cell responses in the vasculature.

Objective

The present study sought to investigate the protective role of OA-NO2 in angiotensin II (Ang II)-induced hypertension.

Methods and Results

We show that systemic administration of OA-NO2 results in a sustained reduction of Ang II-induced hypertension in mice and exerts a significant blood pressure lowering effect on preexisting hypertension established by Ang II infusion. OA-NO2 significantly inhibits Ang II contractile response as compared to oleic acid (OA) in mesenteric vessels. The improved vasoconstriction is specific for the Ang II receptor (AT1R)-mediated signaling since vascular contraction by other G-protein coupled receptors is not altered in response to OA-NO2 treatment. From the mechanistic viewpoint, OA-NO2 lowers Ang II-induced hypertension independently of peroxisome proliferation-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) activation. Rather, OA-NO2, but not OA, specifically binds to the AT1R, reduces heterotrimeric G-protein coupling and inhibits IP3 and calcium mobilization, without inhibiting Ang II binding to the receptor.

Conclusions

These results demonstrate that OA-NO2 diminishes the pressor response to Ang II and inhibits AT1R-dependent vasoconstriction, revealing OA-NO2 as a novel antagonist of Ang II-induced hypertension.

Keywords: nitroalkenes, hypertension, angiotensin II, angiotensin II type 1 receptor, peroxisome proliferation-activated receptor-γ

Introduction

The nitrate-nitrite (NO2−)-nitric oxide (NO) pathway1 is emerging as an important mediator of cell signaling and bioenergetics events, with therapeutic implications in blood flow regulation, and tissue responses to hypoxia2, 3. Nitroalkene derivatives of unsaturated fatty acids represent the convergence of such NO pathway with lipids4 since they are formed by NO and NO2−-dependent redox reactions1. Thus, they constitute a subset of molecules in the emerging physiological pool of the nitric oxide derived metabolome5, 6 that control the physiological homeostasis by coordinating adaptive responses7, 8. At present, the mechanisms underlying the production of nitrated lipids under biological conditions, specific structural isomer distributions, nitrated fatty acid-susceptible proteome and detailed biological signaling actions are incompletely characterized6. It is agreed that under conditions in which O2 tension is low (e.g. ischemia and anoxia), the balance between peroxyl radical formation and coupling with •NO2 shifts toward nitration reactions9, 10. Thus, nitroalkenes are significantly increased in the heart after reperfusion in an ischemia-reperfusion injury model11 and these species are abundantly generated in the mitochondria of hearts exposed to ischemic preconditioning12, 13.

Nitroalkenes transduce signaling reactions by covalently modifying nucleophilic protein targets and altering their structure and function6. For instance, nitro derivatives of linoleic and oleic (OA-NO2) acids are activators of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ)14, 15, form covalent adducts with the p65 subunit of NF-κB16, and activate the Keap1/Nrf2 antioxidant response, reactions that promote adaptive responses in vascular cells17, 18. These derivatives of NO-mediated redox reactions represent an inflammatory-resolving adaptive response7. In the context of the vasculature, OA-NO2 inhibits neointimal hyperplasia19 and exerts vasorelaxation of preconstricted aortic rings20. For these reasons and due to the well-established vasorelaxant properties of pharmacological doses of nitrite21, it is plausible to suggest that nitroalkenes will have a significant impact in the regulation of blood pressure and vascular tone.

Herein, we determined whether a nitroalkene derivative ameliorate angiotensin II (Ang II)-induced hypertension. As the major component of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, deregulation of Ang II production plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of hypertension22. Thus, inhibition of the catalytic activity of the angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) or competitive inhibition of AT1R ligand binding by angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), are two prevalent treatment options for hypertension23. Also, molecular targets of nitroalkenes, such as PPARγ and the AT1R reported herein, reflect common signaling targets that influence the progression of hypertension and other cardiovascular and metabolic diseases24.

Methods

Ang II-induced hypertension model

Blood pressure (BP) in mice was measured by radiotelemetry. Mice were subjected to subcutaneous implantation of osmotic mini-pumps for delivery of OA-NO2 or oleic acid (OA) at a concentration supporting an infusion rate of 5 mg/kg/day and Ang II was administered at an infusion rate of 500 ng/kg/min.

In vivo infusion for blood pressure tracings and vessel contraction analysis

OA or OA-NO2 and the PPARγ inhibitor, GW9662 were delivered via the jugular vein. BP recordings were monitored before and after Ang II infusion (10μg/mL, infusion rate: 1μL/min) using a 1.4F micro-tip catheter sensor inserted into the right carotid artery. Second-order mesenteric arteries from SD rats were mounted onto a myograph. Vessels were pretreated with OA-NO2 or OA at 2.5 μmol/L and 5 μmol/L and then 10 min contracted with Ang II, phenylephrine (PE) or endothelin-1 (ET-1), respectively.

Analysis of OA-NO2 binding to the AT1R

The trans-alkylation reaction of AT1R-bound OA-NO2 was performed according to the methodology previously described13.

An expanded Methods Section is available in the online data supplement.

Results

OA-NO2 reduces Ang II-induced hypertension

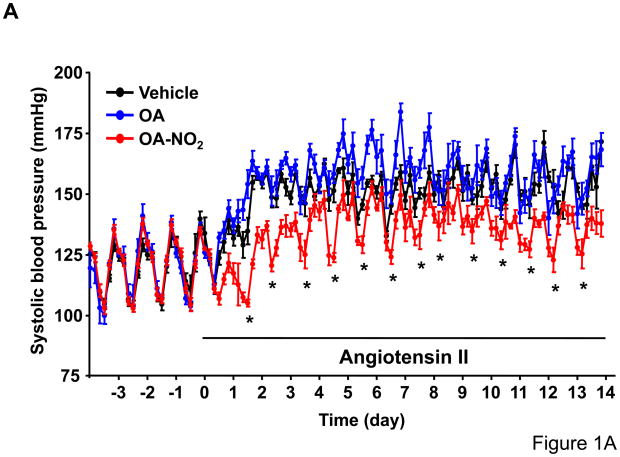

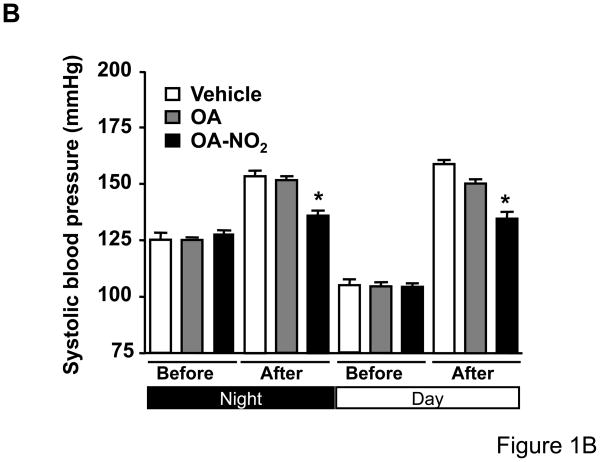

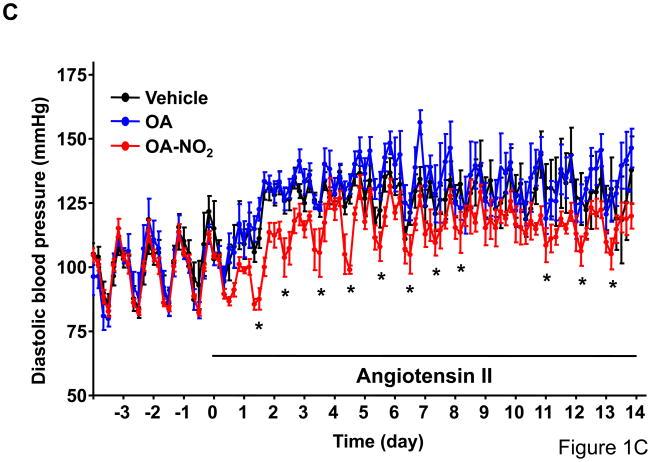

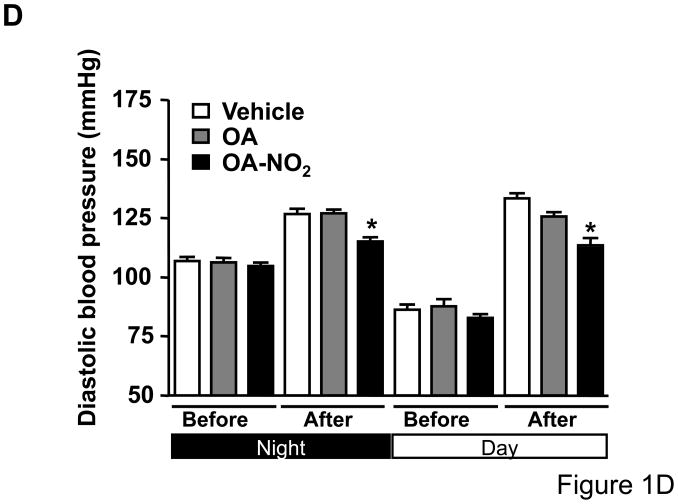

To determine whether OA-NO2 plays a role on Ang II-mediated hypertension, we delivered OA-NO2 (5 mg/kg/day) as well as its non-nitrated counterpart, OA, systemically via osmotic minipumps in C57/BL6 mice. Systemic delivery of OA and OA-NO2 did not affect baseline systolic or diastolic BP recordings measured by radiotelemetry during the first week of the analysis as compared with polyethylenglycol-treated group that served as vehicle control (Figure 1A and 1C). Subsequently, mice were further treated with Ang II supporting an infusion rate of 500 ng/kg/min for two additional weeks. Under these conditions, OA-NO2 but not OA significantly reduced Ang II-dependent increases in systolic (~15 mmHg reduction) and diastolic BP (~12 mmHg reduction) compared to control OA or vehicle treated animals (Figure 1B and 1D), without any apparent changes in the heart rate (Online Figure I). These results strongly indicate that OA-NO2 treatment has a significant impact on Ang II-induced hypertension through a prolonged and sustained reduction of BP.

Figure 1. OA-NO2 inhibits Ang II-induced hypertension.

Mice implanted with osmotic pumps adjusted to deliver 5 mg/kg/day OA-NO2 (red) or OA (blue) and vehicle control (black) were infused with Ang II at a pressor rate of 500 ng/kg/min. Systolic (A) and diastolic (C) blood pressure was measured by radiotelemetry. Data are shown as mean ± SEM, n=6 in each group, *P < 0.05. OA-NO2-treated mice showed significantly lower systolic (~15 mmHg reduction) (B) and diastolic pressure (~12 mmHg reduction) (D) after Ang II challenge than did OA and vehicle-treated mice as determined both at the night and day time periods. Data in B and D are shown as mean ± SEM of measurements collected before (3 days) and after Ang II (12 days), n=6 in each group, *P < 0.05.

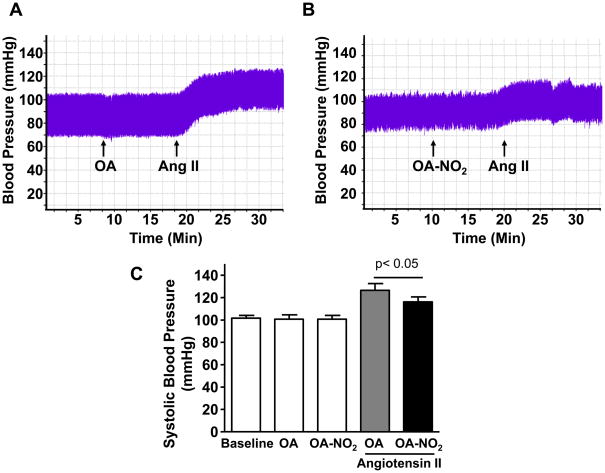

We then monitored BP in isoflurane-anesthetized mice by in vivo tracing recordings upon short term-infusion of Ang II, which results in a rapid increase in systemic BP. OA and OA-NO2 (1 mmol/L, infusion rate: 1 μL/min) administered before Ang II delivery (1μmol/L, infusion rate: 1μL/min) did not alter basal BP recordings (Figure 2A and 2B). Rather, OA-NO2 but not similar concentrations of the native OA significantly prevented BP elevation after short-term infusion of Ang II (Figure 2C). To determine whether OA-NO2 actually reduces the pressor response to Ang II, we then administered OA-NO2 to mice 3 days post-Ang II osmotic minipumps implantation (Figure 2D and 2E). Under these experimental conditions, OA-NO2 but not OA results in a dose-dependent reduction of BP to the preexisting Ang II-induced hypertension (Figure 2F). Taken together, these results demonstrate that OA-NO2 diminishes the pressor response to Ang II in vivo, regardless of whether the nitroalkene is administered before of after Ang II challenge.

Figure 2. OA-NO2 inhibits the pressor response to Ang II.

BP was monitored upon treatment with OA (A) and OA-NO2 (B) (10 mg/kg) before Ang II infusion (10μg/mL, infusion rate: 1μL/min). All drugs were delivered via jugular vein administration starting at the time indicated by the arrows. BP tracings were recorded by insertion of a micro-tip catheter sensor into the right carotid artery. (C) Systolic BP was averaged for a 10 min period before and after Ang II infusion (10μg/mL, infusion rate: 1μL/min). Data are shown as mean ± SEM, n=6 in each group. OA-NO2 significantly reduced the pressor response to Ang II infusion compared to OA. P < 0.05 (OA-NO2 vs. OA after Ang II infusion). (C) Hypertension was developed in mice in 3 days after implantation of osmotic pumps to infuse Ang II at a pressor rate of 500 ng/kg/min. OA (D) or OA-NO2 (E) were then delivered to mice via the jugular vein at increasing concentrations as indicated by the arrows. BP tracings were recorded as described above. (C) Data in D and E are summarized as systolic BP reduction (in mmHg) after either OA or OA-NO2 treatment as compared to maximal systolic pressure in Ang II hypertensive mice. OA-NO2 treatment but not OA dose-dependently reduced established hypertension upon Ang II delivery. Data are shown as mean ± SEM, n=4 in each group, *P < 0.05.

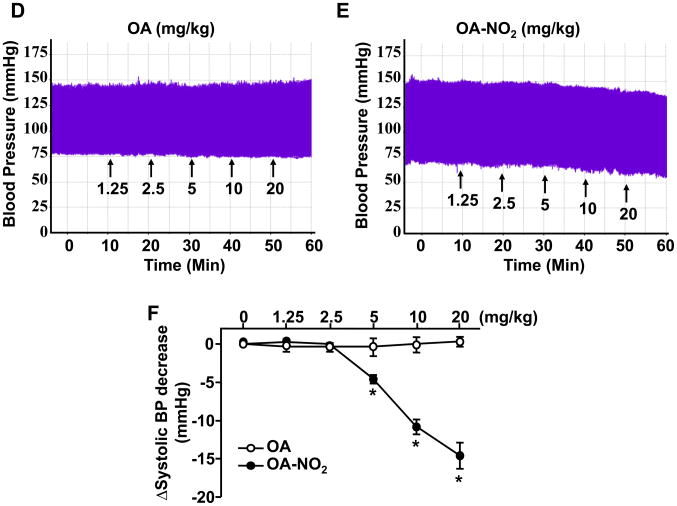

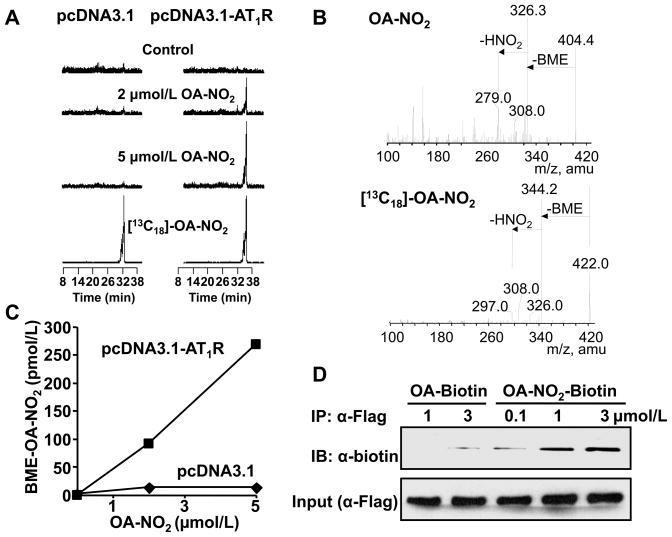

OA-NO2 specifically inhibits Ang II-induced vasoconstriction

To determine the specificity of OA-NO2 effects on Ang II-induced hypertension, we evaluated whether OA-NO2 may result in changes of vascular contractility. In isolated second-order rat mesenteric vessels, the presence of OA-NO2 (2.5 μmol/L) resulted in ~50% reduction of Ang II-mediated vasoconstriction at 10−7 mol/L (corresponding to ~70% of the contractile response induced by 50 mmol/L KCl), whereas 5 μmol/L OA-NO2 but not OA almost completely abolishes contraction induced by Ang II (Figure 3A and Online Figure IV). Thus, OA-NO2 treatment dose-dependently reduced Ang II-dependent vasoconstriction. Interestingly, vasoconstriction elicited by signaling through other members of the G-protein coupled receptor family (GPCR), such as by treatment with phenylephrine (PE) and endothelin-1 (ET-1), was not affected upon OA-NO2 treatment at any concentration given (Figure 3B and 3C and Online Figure IV). These results are clearly indicative that OA-NO2 reduces vasoconstriction by specifically interfering with Ang II signaling in the vasculature.

Figure 3. OA-NO2 reduces AT1R-dependent vessel contraction.

Second-grade mesenteric artery rings were mounted into a myograph as described in the Online Material. The mesenteric artery rings were preincubated for 10 min with 2.5 μmol/L or 5 μmol/L of either OA or OA-NO2 as indicated. Vascular contraction was induced by serial addition of increasing concentrations of Ang II (A), PE (B) or ET-1 (C) to the myograph. Contractile response was quantified and shown in the figure as % of the vessel contraction force afforded by 50 mmol/L KCl. OA-NO2 dose-dependently reduced Ang II induced vasoconstriction but not that of PE or ET-1. Data are shown as mean ± SEM, n=6 in each group, *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 (OA-NO2 vs. OA or vehicle (0.1% ethanol-treated arteries).

OA-NO2 reduction of Ang II-induced hypertension is a PPARγ independent phenomenon

Because 1) OA-NO2 activates PPARγ14, 25; 2) PPARγ activators downregulate AT1R in vascular cells26, 27; and 3) certain ARBs inhibit AT1R through PPARγ activity28–30, we assessed whether PPARγ activation by OA-NO2 contributes to the observed reduction of Ang II-induced hypertension in vivo28, 29. To this aim, we first monitored BP by tracing recordings upon stimulation with Ang II in response to the treatment with the PPARγ antagonist, GW9662 (Figure 4). Efficient inhibition of PPARγ by GW9662 was directly demonstrated monitoring PPARγ transcriptional activity by means of EGFP expression in the aorta of 3xPPRE-driven EGFP transgenic reporter mice (Online Figure V). Inhibition of PPARγ alone does not result in basal BP reduction in vivo (Figure 4A and 4B). Moreover, GW9662 administration (10 mg/kg) compared to vehicle treated mice at the same infusion rate did not attenuate BP increases after Ang II challenge (Figure 4 and Online Figure II). Of importance, pretreatment with OA-NO2 but not equimolar concentrations of OA persistently reduced approximately ~10mmHg of Ang-II-mediated BP elevation in the presence or absence of GW9662 (Figure 4C). Further experiments were performed to determine whether PPARγ activation by OA-NO2 affects already established hypertension. To this aim, we compared the BP lowering effect of OA-NO2 vs. rosiglitazone after preincubation with GW9662 in Ang II-induced hypertensive mice as described above. In response to rosiglitazone treatment, BP reduction (~7mmHg) was efficiently antagonized by GW9662 (Online Figure II), whereas OA-NO2 delivery in the presence of GW9662 results in a dose-dependent BP reduction comparable to the lack of the PPARγ antagonist (Online Figure III). Next, we determine the contractile response of mesenteric rings in response to partial inhibition of Ang II-mediated vasoconstriction by OA-NO2 (2.5μmol/L) upon treatment with GW9662 (10μmol/L). As shown in Figure 4D, OA-NO2 similarly diminished Ang II-dependent vasoconstriction with or without PPARγ antagonism by GW9662 treatment. This series of experiments indicate that PPARγ activation by OA-NO2 is not the major mechanism involved in OA-NO2 antagonism of both Ang II-mediated hypertension and vasoconstriction.

Figure 4. OA-NO2 reduces Ang II-induced hypertension independently of PPARγ activation.

BP in mice was monitored with a micro-tip catheter sensor inserted into the right carotid artery by arteriotomy upon treatment with OA (A) and OA-NO2 (B) (10 mg/kg) delivered via jugular vein administration after infusion of the PPARγ inhibitor, GW9662 (10 mg/kg). (A) and (B) show representative BP recordings of n=6 in each treatment before and after Ang II infusion (10μg/mL), delivered at an infusion rate of 1μL/min. (C) OA-NO2 delivery results in a significant reduction of Ang II-induced hypertension (~10 mmHg) independently of PPARγ inhibition by GW9662. Data are depicted as systolic BP increase (in mmHg) after Ang II infusion as compared to baseline systolic pressure and are shown as mean ± SEM, n=6 in each group, P < 0.01 (OA-NO2 vs. OA in either GW9662-treated or DMSO vehicle control-treated group after Ang II infusion). (D) The mesenteric artery rings were preincubated for 10 min with 10 μmol/L of GW9662 and then with 2.5 μmol/L of either OA or OA-NO2 as indicated. Vascular contraction was induced by serial addition of increasing concentrations of Ang II to the bath in the myograph. Contractile response was quantified and shown in the figure as % of the vessel contraction force afforded by 50 mmol/L KCl. OA-NO2 reduced Ang II induced vasoconstriction independent of the PPARγ antagonist, GW9662. Data are shown as mean ± SEM, n=6 in each group, *P < 0.05.

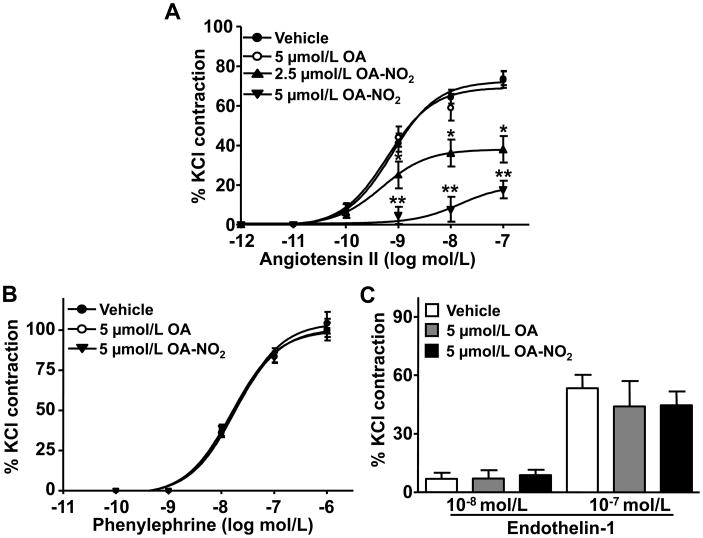

OA-NO2 forms covalent adducts with the AT1R receptor

Nitroalkenes are highly electrophilic and react with cellular nucleophiles via a reversible Michael addition reaction6. Thus, we hypothesized that OA-NO2 could directly modify nucleophilic residues of AT1R and impact the propagation of downstream signaling events. A covalent interaction between OA-NO2 and AT1R was revealed by treatment of HEK293 cells overexpressing AT1R with OA-NO2 or OA. Following immunoprecipitation of AT1R from cell lysates, a trans-alkylation reaction of AT1R-bound OA-NO2 permitted the detection and quantification of OA-NO2 adduction by HPLC-MS/MS (Online Methods). HEK293 cells treated with increasing concentrations of OA-NO2 revealed significantly increased levels of AT1R-adducted OA-NO2 compared with control cells (Figure 5A). OA-NO2 bound to the AT1R, quantified as a β-mercaptoethanol (BME) derivative upon nucleophilic exchange of OA-NO2 from the AT1R to BME13, revealed a ~20-fold increase of adducted OA-NO2 in AT1R-expressing cells when compared to controls (Figure 5C). The MS/MS-induced fragmentation of recovered BME-OA-NO2 adducts gave product ions and ion intensities similar to a synthetic BME-OA-NO2 standard and BME-[13C18]-OA-NO2 used as an internal control (Figure 5B). Thus, the presence of BME-exchangeable OA-NO2 demonstrates the direct adduction of the AT1R by OA-NO2. Moreover, immunoprecipitation of AT1R from HEK293 cells transfected with Flag-tagged-AT1R after treatment with biotin-labeled OA-NO2, showed a dose-dependent increase in biotin-OA-NO2-adducted to the AT1R compared with biotin-OA treated controls (Figure 5D). Thus, two independent approaches showed that AT1R is a relevant cellular target of OA-NO2 alkylation.

Figure 5. OA-NO2 forms covalent adducts with AT1R but does not affect Ang II binding to the receptor.

(A) HEK293 cells were transfected with 500 ng FLAG-tagged AT1R plasmid (pcDNA3.1-AT1R) versus control plasmid (pcDNA3.1) and treated with OA or OA-NO2 as indicated. Immunoprecipitated AT1R was subjected to a BME-based trans-nitroalkylation reaction13 as detailed in the Online Material. Adducted OA-NO2 to AT1R was released as BME-OA-NO2 and quantified using mass spectrometry. The chromatographic profile shows a dose-dependent increase of OA-NO2 after immunoprecipitation against AT1R and verified by coelution with [13C18]-OA-NO2 internal standard (lower panel). (B) The fragmentation pattern (upper panel) of AT1R-derived OA-NO2 (5 μmol/L treatment) adducted to BME was confirmed by comparison with that of [13C18]-OA-NO2 (lower panel). Enhanced levels of the ion products in the peaks and comparison to the internal standard confirmed the structure for the proposed adducts formed after trans-nitroalkylation. The data shown is a representative set of 3 independent experimental repetitions. (C) Quantification of the AT1R-derived BME adducts after nucleophilic exchange of OA-NO2 from the AT1R to BME, reveal a significant increase of adducted OA-NO2 to the AT1R (270 pmol/L vs. 13 pmol/L BME-OA-NO2, respectively after 5 μmol/L OA-NO2 treatment). (D) HEK293 cells were similarly transfected with the pcDNA3.1-AT1R plasmid and treated with biotin-labeled OA-NO2 or OA for 3 h at the indicated concentrations. Biotin-labeled adducts were visualized by Western blot after immunoprecipitation of the Flag-AT1R. OA-NO2 dose-dependently increased the covalent adduction to the immunoprecipitated AT1R. The data shown is a representative set of 3 independent experimental repetitions. (E) Competition binding assays were performed using confluent VSMC pretreated with 2.5μmol/L of OA or OA-NO2 for 10 min and then incubated for 30 min with 0.3 nmol/L 125I-[Sar1,Ile8]-Ang II and different concentrations of non-radiolabeled Ang II as indicated. Data are shown as % of maximal binding with 125I-[Sar1,Ile8]-Ang II. (F) Similarly, VSMC treated with different doses of OA or OA-NO2 as indicated were then incubated for 30 min at 37°C with 0.1 nmol/L of 125I-[Sar1,Ile8]-Ang II. The ARB losartan (1μmol/L) served as a positive control. In panels E and F, radioactivity was measured using a γ-counter and values are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=4). The experiments were performed three times with similar results.

OA-NO2 does not interfere with Ang II binding to the receptor

Next, we sought to determine whether the adduction of the AT1R by OA-NO2 interferes with Ang II binding. Unlike the ARB losartan, that inhibits Ang II binding to AT1R, neither OA-NO2 nor OA affected binding of radio-labeled Ang II to its receptor (Figure 5E). Furthermore, neither OA-NO2 nor OA influenced the displacement of [125I]-Ang II bound to AT1R in ligand-receptor binding competition analyses using non-radioactive Ang II (Figure 5F). This indicates that OA-NO2 adduction of the AT1R does not affect Ang II binding and represents a novel manner of AT1R antagonism that is distinct from competitive ARBs31.

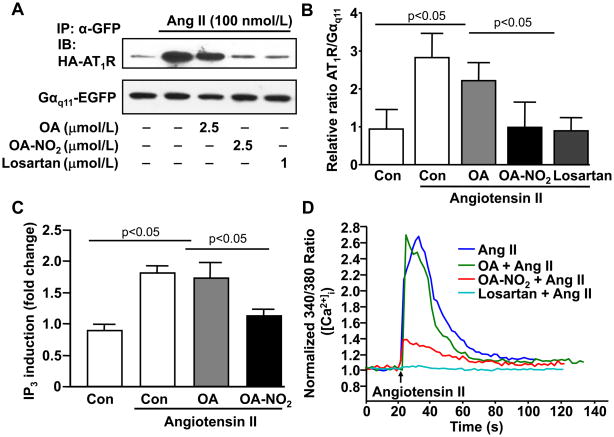

OA-NO2 interferes with G-protein coupling to the AT1R and prevents Ang II-mediated contractile responses in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC)

Since OA-NO2 adduction of the AT1R does not affect Ang II binding, we next examined whether OA-NO2 affects AT1R coupling to the heterotrimeric G-protein (Gαq11). To this aim, we treated HEK293 cells overexpressing HA-tagged-AT1R, Gαq11-EGFP, Gβ1 and HA-tagged-Gγ2 with OA-NO2 or OA and determined Gαq11 coupled to the AT1R following immunoprecipitation of Gαq11-EGFP and immunodetection of HA-tagged-AT1R by Western blot. OA-NO2 but not OA significantly reduced AT1R coupled to the immunoprecipitated Gαq11 after 1 min stimuli with Ang II (100 nmol/L) (Figure 6A and 6B). Taken together, adduction of OA-NO2 with the AT1R does not affect Ang II binding but reduces G-protein coupled to the AT1R. Finally, the impact of OA-NO2 on the contractile response of VSMC downstream of AT1R reaction was evaluated, where Ang II-triggered second messenger mobilization was measured. Competitive radioreceptor analysis showed that OA-NO2, but not OA, reduced Ang II-induced intracellular inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) mobilization (Figure 6C). Accordingly, we show a dose-dependent inhibition of Ang II-mediated increase in intracellular calcium mobilization ([Ca2+]i) upon OA-NO2 treatment, as determined by fluorescence imaging of fura-2 (Figure 6D). Pretreatment of VSMC with 2.5 μmol/L OA-NO2 significantly reduced the ratio of fura-2 fluorescent emission induced by Ang II (75%), while 1μmol/L losartan completely inhibited Ang II-mediated increases in [Ca2+]i. By comparison, OA had no impact in Ang II-induced [Ca2+]i increase (Figure 6D, Online Figure VI and Online Movies I–III).

Figure 6. OA-NO2 uncouples Gαq11 to the AT1R and inhibits Ang II-induced IP3 production and Ca2+ mobilization in VSMC.

(A) HEK293 cells cultured in 6-well plates were cotransfected with HA-tagged AT1R (0.3 μg), Gαq11-EGFP (0.3 μg), Gβ1 (0.1 μg) and Gγ2 (0.1 μg) plasmids and treated with either OA, OA-NO2 (2.5 μmol/L) or losartan (1μmol/L) 30min before stimulation with Ang II (100 nmol/L) for 1 min. Immunoprecipitated Gαq11 using a GFP antibody was subjected to deglycosylation before Western blot analysis for detection of HA-tagged AT1R. OA-NO2 but not OA reduced AT1R coupled to the immunoprecipitated Gαq11.The data shown is representative of 3 independent experiments. (B) Western blots were quantified using the ImageJ software after densitometric scanning of the films and expressed as relative ratio of AT1R vs. Gαq11. n=3. P < 0.05 OA-NO2 vs. OA in Ang II-treated cells and P < 0.05 Ang II-treated vs. vehicle control cells (Con). (C) VSMC were treated with either 2.5 μmol/L OA-NO2 or OA and then pulsed with 100 nmol/L Ang II for 45 min. IP3 production was monitored by radioreceptor assays. Ang II induced a 2-fold increase of intracellular IP3, whereas OA-NO2, but not OA blocked Ang II-mediated IP3 production, n=6. P < 0.05 OA-NO2 vs. OA in Ang II-treated cells and P < 0.05 Ang II-treated vs. vehicle control cells (Con). (B) VSMC were similarly treated with either OA-NO2 or OA (2.5μmol/L) and then pulsed with Ang II (100 nmol/L) in the presence of fura-2. Control experiments were performed with losartan (1 μmol/L) pretreated cells. Emission ratio between 340 nm and 380 nm was used to calculate intracellular calcium concentration as described in Online Material. The data shown depicts a representative time tracing of 6 independent experiments. The ratio-time traces were generated by averaging three typical cells in the field of view as described in Online Figure VI and Online Movies I through III).

Discussion

Early studies deciphering the physiological and/or pharmacological roles of nitrated fatty acids indicate that nitro-derivatives of fatty acids exert relevant biological effects in the vasculature32–34 (for review, see35). More recent data, using cardiovascular models of disease strongly support the notion that nitroalkenes serve as novel therapeutic tools associated with vascular and cardiac tissue damage11, 16, 19.

In the present study, we provide compelling evidence supporting that OA-NO2 reduces Ang II-mediated hypertension in a model of Ang II infusion in mice. Systemic delivery of pharmacological doses of OA-NO2 but not OA resulted in a prolonged and sustained reduction of BP throughout the 14 days of Ang II infusion. The differences in BP in the OA-NO2 group as compared to OA or vehicle group were more pronounced during the first week of Ang II infusion, when BP raised and remained highest, and persisted significantly lower during the second week of Ang II infusion, when physiological compensatory mechanisms might occur to reduce BP in response to a long-term hypertensive challenge36. Thus, our long-term radiotelemetry analysis confirmed that OA-NO2 diminished the pressor response to Ang II rather than simply delay Ang II dependent hypertension. Furthermore, comparative analysis with the inclusion of the OA-treated group, as the non-nitrated counterpart for OA-NO2 also indicates that OA alone at the dosage used in the present study did not reduce Ang II-mediated hypertension in contrast to previous studies indicating that OA or related species might be hypotensive37. Thus, at an infusion rate of 5mg/kg/day, reduction of Ang II-mediated hypertension is afforded by the nitrated but not free form of OA.

Under our experimental conditions, Ang II infusion did not result in significant changes of free nitroalkenes in plasma (data not shown); indicating that chronic infusion of Ang II might not generate sufficient systemic reactions to be detected at the serum level of these hypertensive mice. It has been previously shown that pro-inflammatory stimuli increases fatty acid nitration in macrophages38. In vivo, nitroalkene production is abundantly generated in the mitochondria of the heart after ischemia-reperfusion injury12, 13. Therefore, it seems critical to determine the local production of nitroalkenes in response to certain types of injury and on specific subcellular compartments locally in tissues. From the present study it cannot be excluded that local generation of nitrated fatty acids, for instance, within the vasculature, might occur in response to Ang II39.

In ex vivo vasoconstriction assays, OA-NO2 inhibited Ang II-mediated vascular contractility in an AT1R-dependent fashion. Specificity for the AT1R relies on the observations that OA-NO2 dose-dependently inhibited Ang II-mediated vessel contraction but did not reduced vascular contractility induced by vasoconstrictors signaling through other GPCR, such as the observed endothelin-1 and phenylephrine. Activation of PPARγ by OA-NO2 is a well-established mechanism that could account for the reduction of Ang II-induced hypertension and vascular contractility by OA-NO2. A reverse relationship between AT1R signaling and PPARγ has been recognized since genetic polymorphisms in the PPARγ locus cause hypertension40 and PPARγ agonists improve hypertension and vascular function41. Regardless, whereas pharmacological inhibition of PPARγ efficiently blunts rosiglitazone effects on BP, it did not reverse OA-NO2 reduction of Ang II-mediated hypertension. Moreover, experimental animal models clearly indicate that PPARγ regulates vascular contractility mediated not only by AT1R but also by other GPCR42, 43. Taking into account that OA-NO2 specifically reduced Ang II-mediated vascular contractility but did not interfere with the contractile properties of ET-1 and PE, it can be concluded that PPARγ activation by OA-NO2 is not the major mechanism involved in OA-NO2 effects on AngII-induced hypertension.

Notably, we demonstrate by two independent experimental approaches that OA-NO2 binds to the AT1R. Quantitative analysis of the adduction of OA-NO2 to the AT1R was demonstrated by the nucleophilic exchange of nitroalkenes from adducted proteins to BME, as extensively described13. The trans-nitroalkylation reaction of OA-NO2 from AT1R adduction to BME revealed a dose-dependent increase of bound OA-NO2 to the AT1R. These results were further confirmed by immunoprecipitation analysis of AT1R and detection of biotinylated-OA-NO2. However, adduction of the AT1R by OA-NO2 did not interfere with Ang II binding to its receptor, suggesting that the molecular interactions between OA-NO2 and AT1R are unlikely similar to typical competitive inhibitors of AT1R44, 45.

Crystal structures for some proteins of the seven transmembrane family, to which the AT1R belongs, show that monomers associate through a lipophilic interface with limited protein-protein contacts46. It is becoming increasingly evident that lipid/membrane structures interact with GPCR exerting posttranslational modification within the GPCR47. It is likely that these protein/lipid interactions48, 49 may serve as regulatory mechanisms with diverse impact on downstream signaling actions47. Thus, AT1R adduction by OA-NO2 may result in an allosteric inhibition by adducting to the hydrophobic interface in a fashion reminiscent of the A2A adenosine receptor antagonist50. This could promote an inactive state of the receptor, thus uncoupling Ang II binding from downstream activation47. Further studies will be aimed at dissecting the molecular mechanisms by which electrophilic fatty acid derivatives reduce Ang II-mediated hypertension, including biochemical and crystallographic approaches, thus aiding in the design of a new generation of AT1R antagonists with increased selectivity.

In summary, this is the first demonstration that OA-NO2 has a long-lasting impact on hypertension induced by Ang II infusion and exerts a significant BP lowering effect on preexisting hypertension. OA-NO2 antagonizes Ang II signaling due to the formation of stable adducts with the AT1R leading to a reduced vasoconstriction via uncoupling G-protein signaling and subsequently reducing second messenger mobilization.

Novelty and Significance.

What Is Known?

Nitroalkenes are nitric oxide derivatives of unsaturated fatty acids with pleiotropic biological activities of relevance for metabolic and cardiovascular diseases.

Nitro-oleic acid (OA-NO2) protects against vascular lesion, atherosclerosis, cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury and diabetes in experimental animal models.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

OA-NO2 reduces blood pressure and vasoconstriction in response to angiotensin II.

OA-NO2 binds angiotensin II receptor (AT1R) but it does not interfere with Ang II binding to the receptor unlike typical competitive angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), thus defining a novel mechanism for antagonism.

OA-NO2 and rosiglitazone reduce established hypertension through different pathways.

Inhibition of AT1R by OA-NO2 uncouples downstream G-protein signaling and calcium mobilization.

We demonstrate for the first time that OA-NO2 has a long-lasting impact on hypertension induced by Ang II infusion in an animal model where systemic delivery of pharmacological doses of OA-NO2, but not its parental fatty acid, oleic acid, results in a prolonged and sustained reduction of blood pressure. We show that OA-NO2 lowers blood pressure on preexisting hypertension and inhibits vascular contractility in an AT1R-dependent fashion. OA-NO2 shows specificity for the AT1R, since OA-NO2 dose-dependently inhibits Ang II-mediated vessel contraction but does not reduce vascular contractility induced by alternative vasoconstrictors, such as endothelin-1 and phenylephrine, signaling through other G-protein coupled receptors. We describe that OA-NO2 lowers Ang II-induced hypertension independent- of peroxisome proliferation-activated receptor-γ activation. Rather, OA-NO2 binds directly to the AT1R without interfering with angiotensin II binding, suggesting that the molecular interactions between OA-NO2 and AT1R are likely to differ from ARBs competitive inhibition. OA-NO2 reduces heterotrimeric G-protein coupling to the AT1R and inhibits downstream signaling. This novel regulatory mechanism of the AT1R by OA-NO2 could inform the design of a new generation of AT1R antagonists with increased selectivity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the NIH grants HL68878 and HL089544 (YEC), HL58115 and HL64937 (BAF), CA116592 (CXD), American Heart Association 0835237N (JZ), 09SDG2110143 (LC) and American Diabetes Association 7-08-JF-52 (FJS). YEC is an Established Investigator of American Heart Association (0840025N).

Abbreviations

- ACE

angiotensin converting enzyme

- Ang II

angiotensin II

- ARB

angiotensin receptor blocker

- AT1R

angiotensin II type 1 receptor

- BME

β-mercaptoethanol

- BP

blood pressure

- ET-1

endothelin-1

- IP3

inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate

- NO

nitric oxide

- NO2−

nitrate

- OA

oleic acid

- OA-NO2

nitro-oleic acid

- PPARγ

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ

- PE

phenylephrine

Footnotes

Disclosures

BAF acknowledges financial interest in Complexa, Inc.

References

- 1.Lundberg JO, Gladwin MT, Ahluwalia A, Benjamin N, Bryan NS, Butler A, Cabrales P, Fago A, Feelisch M, Ford PC, Freeman BA, Frenneaux M, Friedman J, Kelm M, Kevil CG, Kim-Shapiro DB, Kozlov AV, Lancaster JR, Jr, Lefer DJ, McColl K, McCurry K, Patel RP, Petersson J, Rassaf T, Reutov VP, Richter-Addo GB, Schechter A, Shiva S, Tsuchiya K, van Faassen EE, Webb AJ, Zuckerbraun BS, Zweier JL, Weitzberg E. Nitrate and nitrite in biology, nutrition and therapeutics. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:865–869. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cosby K, Partovi KS, Crawford JH, Patel RP, Reiter CD, Martyr S, Yang BK, Waclawiw MA, Zalos G, Xu X, Huang KT, Shields H, Kim-Shapiro DB, Schechter AN, Cannon RO, 3rd, Gladwin MT. Nitrite reduction to nitric oxide by deoxyhemoglobin vasodilates the human circulation. Nat Med. 2003;9:1498–1505. doi: 10.1038/nm954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jansson EA, Huang L, Malkey R, Govoni M, Nihlen C, Olsson A, Stensdotter M, Petersson J, Holm L, Weitzberg E, Lundberg JO. A mammalian functional nitrate reductase that regulates nitrite and nitric oxide homeostasis. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:411–417. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker PR, Schopfer FJ, O’Donnell VB, Freeman BA. Convergence of nitric oxide and lipid signaling: anti-inflammatory nitro-fatty acids. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:989–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudolph V, Schopfer FJ, Khoo NK, Rudolph TK, Cole MP, Woodcock SR, Bonacci G, Groeger AL, Golin-Bisello F, Chen CS, Baker PR, Freeman BA. Nitro-fatty acid metabolome: saturation, desaturation, beta-oxidation, and protein adduction. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1461–1473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802298200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeman BA, Baker PR, Schopfer FJ, Woodcock SR, Napolitano A, d’Ischia M. Nitro-fatty acid formation and signaling. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15515–15519. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800004200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bjorn G. Clues emerge about benefits of briefly blocking blood flow. Nat Med. 2009;15:132. doi: 10.1038/nm0209-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nathan C. The moving frontier in nitric oxide-dependent signaling. Sci STKE. 2004;2004:pe52. doi: 10.1126/stke.2572004pe52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rudolph TK, Freeman BA. Transduction of redox signaling by electrophile-protein reactions. Sci Signal. 2009;2:re7. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.290re7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rudolph V, Freeman BA. Cardiovascular consequences when nitric oxide and lipid signaling converge. Circ Res. 2009;105:511–522. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.202077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rudolph V, Rudolph TK, Schopfer FJ, Bonacci G, Woodcock SR, Cole MP, Baker PR, Ramani R, Freeman BA. Endogenous generation and protective effects of nitro-fatty acids in a murine model of focal cardiac ischaemia and reperfusion. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;85:155–166. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nadtochiy SM, Baker PR, Freeman BA, Brookes PS. Mitochondrial nitroalkene formation and mild uncoupling in ischaemic preconditioning: implications for cardioprotection. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;82:333–340. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schopfer FJ, Batthyany C, Baker PR, Bonacci G, Cole MP, Rudolph V, Groeger AL, Rudolph TK, Nadtochiy S, Brookes PS, Freeman BA. Detection and quantification of protein adduction by electrophilic fatty acids: mitochondrial generation of fatty acid nitroalkene derivatives. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:1250–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schopfer FJ, Lin Y, Baker PR, Cui T, Garcia-Barrio M, Zhang J, Chen K, Chen YE, Freeman BA. Nitrolinoleic acid: an endogenous peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2340–2345. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408384102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y, Zhang J, Schopfer FJ, Martynowski D, Garcia-Barrio MT, Kovach A, Suino-Powell K, Baker PR, Freeman BA, Chen YE, Xu HE. Molecular recognition of nitrated fatty acids by PPAR gamma. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:865–867. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cui T, Schopfer FJ, Zhang J, Chen K, Ichikawa T, Baker PR, Batthyany C, Chacko BK, Feng X, Patel RP, Agarwal A, Freeman BA, Chen YE. Nitrated fatty acids: Endogenous anti-inflammatory signaling mediators. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35686–35698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603357200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villacorta L, Zhang J, Garcia-Barrio MT, Chen XL, Freeman BA, Chen YE, Cui T. Nitro-linoleic acid inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation via the Keap1/Nrf2 signaling pathway. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H770–776. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00261.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kansanen E, Jyrkkanen HK, Volger OL, Leinonen H, Kivela AM, Hakkinen SK, Woodcock SR, Schopfer FJ, Horrevoets AJ, Yla-Herttuala S, Freeman BA, Levonen AL. Nrf2-dependent and -independent responses to nitro-fatty acids in human endothelial cells: identification of heat shock response as the major pathway activated by nitro-oleic acid. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:33233–33241. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.064873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cole MP, Rudolph TK, Khoo NK, Motanya UN, Golin-Bisello F, Wertz JW, Schopfer FJ, Rudolph V, Woodcock SR, Bolisetty S, Ali MS, Zhang J, Chen YE, Agarwal A, Freeman BA, Bauer PM. Nitro-fatty acid inhibition of neointima formation after endoluminal vessel injury. Circ Res. 2009;105:965–972. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.199075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lim DG, Sweeney S, Bloodsworth A, White CR, Chumley PH, Krishna NR, Schopfer F, O’Donnell VB, Eiserich JP, Freeman BA. Nitrolinoleate, a nitric oxide-derived mediator of cell function: synthesis, characterization, and vasomotor activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15941–15946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232409599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lundberg JO, Weitzberg E, Gladwin MT. The nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway in physiology and therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:156–167. doi: 10.1038/nrd2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehta PK, Griendling KK. Angiotensin II cell signaling: physiological and pathological effects in the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C82–97. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00287.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watanabe T, Barker TA, Berk BC. Angiotensin II and the endothelium: diverse signals and effects. Hypertension. 2005;45:163–169. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000153321.13792.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurtz TW. Beyond the classic angiotensin-receptor-blocker profile. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008;5 (Suppl 1):S19–26. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baker PR, Lin Y, Schopfer FJ, Woodcock SR, Groeger AL, Batthyany C, Sweeney S, Long MH, Iles KE, Baker LM, Branchaud BP, Chen YE, Freeman BA. Fatty acid transduction of nitric oxide signaling: multiple nitrated unsaturated fatty acid derivatives exist in human blood and urine and serve as endogenous peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor ligands. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:42464–42475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504212200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takeda K, Ichiki T, Tokunou T, Funakoshi Y, Iino N, Hirano K, Kanaide H, Takeshita A. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activators downregulate angiotensin II type 1 receptor in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circulation. 2000;102:1834–1839. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.15.1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sugawara A, Takeuchi K, Uruno A, Ikeda Y, Arima S, Kudo M, Sato K, Taniyama Y, Ito S. Transcriptional suppression of type 1 angiotensin II receptor gene expression by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma in vascular smooth muscle cells. Endocrinology. 2001;142:3125–3134. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.7.8272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benson SC, Pershadsingh HA, Ho CI, Chittiboyina A, Desai P, Pravenec M, Qi N, Wang J, Avery MA, Kurtz TW. Identification of telmisartan as a unique angiotensin II receptor antagonist with selective PPARgamma-modulating activity. Hypertension. 2004;43:993–1002. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000123072.34629.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schupp M, Janke J, Clasen R, Unger T, Kintscher U. Angiotensin type 1 receptor blockers induce peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma activity. Circulation. 2004;109:2054–2057. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000127955.36250.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imayama I, Ichiki T, Inanaga K, Ohtsubo H, Fukuyama K, Ono H, Hashiguchi Y, Sunagawa K. Telmisartan downregulates angiotensin II type 1 receptor through activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;72:184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vauquelin G, Van Liefde I, Vanderheyden P. Models and methods for studying insurmountable antagonism. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2002;23:514–518. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(02)02081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balazy M, Iesaki T, Park JL, Jiang H, Kaminski PM, Wolin MS. Vicinal nitrohydroxyeicosatrienoic acids: vasodilator lipids formed by reaction of nitrogen dioxide with arachidonic acid. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;299:611–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coles B, Bloodsworth A, Clark SR, Lewis MJ, Cross AR, Freeman BA, O’Donnell VB. Nitrolinoleate inhibits superoxide generation, degranulation, and integrin expression by human neutrophils: novel antiinflammatory properties of nitric oxide-derived reactive species in vascular cells. Circ Res. 2002;91:375–381. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000032114.68919.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coles B, Bloodsworth A, Eiserich JP, Coffey MJ, McLoughlin RM, Giddings JC, Lewis MJ, Haslam RJ, Freeman BA, O’Donnell VB. Nitrolinoleate inhibits platelet activation by attenuating calcium mobilization and inducing phosphorylation of vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein through elevation of cAMP. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5832–5840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105209200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Donnell VB, Freeman BA. Interactions between nitric oxide and lipid oxidation pathways: implications for vascular disease. Circ Res. 2001;88:12–21. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lifton RP, Gharavi AG, Geller DS. Molecular mechanisms of human hypertension. Cell. 2001;104:545–556. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Teres S, Barcelo-Coblijn G, Benet M, Alvarez R, Bressani R, Halver JE, Escriba PV. Oleic acid content is responsible for the reduction in blood pressure induced by olive oil. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13811–13816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807500105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferreira AM, Ferrari MI, Trostchansky A, Batthyany C, Souza JM, Alvarez MN, Lopez GV, Baker PR, Schopfer FJ, O’Donnell V, Freeman BA, Rubbo H. Macrophage activation induces formation of the anti-inflammatory lipid cholesteryl-nitrolinoleate. Biochem J. 2009;417:223–234. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laursen JB, Rajagopalan S, Galis Z, Tarpey M, Freeman BA, Harrison DG. Role of superoxide in angiotensin II-induced but not catecholamine-induced hypertension. Circulation. 1997;95:588–593. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.3.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsai YS, Xu L, Smithies O, Maeda N. Genetic variations in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma expression affect blood pressure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19084–19089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909657106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ryan MJ, Didion SP, Mathur S, Faraci FM, Sigmund CD. PPAR(gamma) agonist rosiglitazone improves vascular function and lowers blood pressure in hypertensive transgenic mice. Hypertension. 2004;43:661–666. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000116303.71408.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Diep QN, El Mabrouk M, Cohn JS, Endemann D, Amiri F, Virdis A, Neves MF, Schiffrin EL. Structure, endothelial function, cell growth, and inflammation in blood vessels of angiotensin II-infused rats: role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma. Circulation. 2002;105:2296–2302. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000016049.86468.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beyer AM, Baumbach GL, Halabi CM, Modrick ML, Lynch CM, Gerhold TD, Ghoneim SM, de Lange WJ, Keen HL, Tsai YS, Maeda N, Sigmund CD, Faraci FM. Interference with PPARgamma signaling causes cerebral vascular dysfunction, hypertrophy, and remodeling. Hypertension. 2008;51:867–871. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.103648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miura S, Fujino M, Hanzawa H, Kiya Y, Imaizumi S, Matsuo Y, Tomita S, Uehara Y, Karnik SS, Yanagisawa H, Koike H, Komuro I, Saku K. Molecular mechanism underlying inverse agonist of angiotensin II type 1 receptor. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:19288–19295. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602144200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Le MT, Pugsley MK, Vauquelin G, Van Liefde I. Molecular characterisation of the interactions between olmesartan and telmisartan and the human angiotensin II AT1 receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;151:952–962. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cherezov V, Rosenbaum DM, Hanson MA, Rasmussen SG, Thian FS, Kobilka TS, Choi HJ, Kuhn P, Weis WI, Kobilka BK, Stevens RC. High-resolution crystal structure of an engineered human beta2-adrenergic G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2007;318:1258–1265. doi: 10.1126/science.1150577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huynh J, Thomas WG, Aguilar MI, Pattenden LK. Role of helix 8 in G protein-coupled receptors based on structure-function studies on the type 1 angiotensin receptor. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;302:118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Escriba PV, Wedegaertner PB, Goni FM, Vogler O. Lipid-protein interactions in GPCR-associated signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:836–852. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hanson MA, Cherezov V, Griffith MT, Roth CB, Jaakola VP, Chien EY, Velasquez J, Kuhn P, Stevens RC. A specific cholesterol binding site is established by the 2.8 A structure of the human beta2-adrenergic receptor. Structure. 2008;16:897–905. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jaakola VP, Griffith MT, Hanson MA, Cherezov V, Chien EY, Lane JR, Ijzerman AP, Stevens RC. The 2.6 angstrom crystal structure of a human A2A adenosine receptor bound to an antagonist. Science. 2008;322:1211–1217. doi: 10.1126/science.1164772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.