Abstract

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) has an abysmal prognosis. We now know that the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling pathway along with loss of function of the tumor suppressor genes p16Ink4a/p19ARF and PTEN play a crucial role in GBM pathogenesis: initiating the early stages of tumor development, sustaining tumor growth, promoting infiltration and mediating resistance to therapy. We have recently demonstrated that this genetic combination is sufficient to promote the development of GBM in adult mice. Therapeutic agents raised against single targets of the EGFR signaling pathway have proven rather inefficient in GBM therapy, demonstrating the need for combinatorial therapeutic approaches. An effective strategy for concurrent disruption of multiple signaling pathways is via the inhibition of the molecular chaperone heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90). Hsp90 inhibition leads to the degradation of so-called client proteins of which many are key effectors of GBM pathogenesis. NXD30001 is a novel second generation Hsp90 inhibitor that demonstrates improved pharmacokinetic parameters. Here we demonstrate that NXD30001 is a potent inhibitor of GBM cell growth in vitro consistent with its capacity to inhibit several key targets and regulators of GBM biology. We also demonstrate the efficacy of NXD30001 in vivo in an EGFR driven genetically engineered mouse model of GBM. Our findings establish that the Hsp90 inhibitor NXD30001 is a therapeutically multivalent molecule, whose actions strike GBM at the core of its drivers of tumorigenesis and represent a compelling rationale for its use in GBM treatment.

Keywords: mouse glioblastoma, Hsp90, inhibitor, therapy

Introduction

GBM is the most common type of and most malignant primary astrocytic tumors. It is composed of poorly differentiated aggressive neoplastic cells, which are characterized by an explosive growth, invasiveness and an innate resistance to current therapies (1). At present, the standard-of-care treatment for GBM consists of surgical resection when possible, followed by ionizing radiation with concomitant and adjuvant administration of the alkylating chemotherapeutic agent temozolomide. This vigorous regimen only confers a median survival period of 14.6 months (2) reasserting the need for alternative measures.

Extensive molecular characterizations of GBMs have demonstrated a number of genetic mutations and signaling abnormalities that are now recognized as drivers of uncontrollable growth, invasiveness, angiogenesis and resistance to apoptosis (3, 4). GBMs are now categorized into Proneural, Neural, Classical and Mesenchymal subclasses according to recently characterized and specific gene expression-based molecular classifications (5, 6). In the Classical subtype of GBMs, aberrant expression of EGFR is observed in 100% of the cases (5). Deregulated, active EGFR results in overactivation of the Ras/Raf/MAPK and PI3K/Akt signal transduction pathways, which are both recognized as major contributors to GBM growth and resistance to therapy. Reinforcing the Akt survival pathway in these GBMs is the observation that 95% of these tumors exhibit deletions or mutations within the tumor suppressor gene PTEN and 100% are homozygously deleted or mutated in the INK4a/ARF (CDKN2a) locus (5). This triple combination of activated EGFR, loss of CDKN2a and PTEN loci is found in over a quarter of all GBM patients (5).

Loss of the INK4a/ARF (CDKN2a) locus corresponds to a key event in tumorigenesis. Allosteric binding of the INK4 class of cell-cycle inhibitors to the cyclin-dependent kinases CDK4/6 abrogates their binding to D-type cyclins, a pre-requisite for CDK4/6-mediated phosphorylation of retinoblastoma (Rb) family members and progression through the cell cycle. The tumor suppression activities of the INK4 class of proteins lies in the concept that deletion of p16INK4a in tumors facilitates CDK4/6-ClyclinD complexes formation, shifts Rb-family proteins in a hyperphosphorylated state and thus promotes unregulated cell-cycle progression (reviewed in (7)). In this context, inhibitors of CDK4/6 or CyclinD activities would counteract the effects of loss of INK4 class of proteins in tumor cells and represent an effective strategy against cancer (8).

Hsp90 is a molecular chaperone that maintains the conformation and activity of specific substrates (client proteins), including key proteins involved in signal transduction, cell cycle control and regulation of transcription. Many Hsp90 client proteins are responsible for initiation and maintenance of GBMs including EGFR, Akt, CDK4 and CyclinD1. Compounds that block Hsp90 ATPase activity have been shown to induce proteasomal degradation of cancer-related Hsp90 client proteins (recently reviewed in (9)) and are currently being assessed in clinical trials for cancer treatment (10). The ability of Hsp90 inhibitors to simultaneously target multiple signal transduction pathways involved in proliferation and survival of GBMs makes these compounds ideal therapeutic candidates for the treatment of GBMs and other cancers characterized by multifaceted etiologies.

In this report, we demonstrate that the novel small molecule, second-generation Hsp90 inhibitor NXD30001 (pochoximeA) (11–13) has potent pharmaceutical and pharmacological properties in a genetically engineered pre-clinical mouse model of GBM (14) where its mechanisms of action relate to an effective Hsp90 inhibition. These results provide a preclinical rationale to support escalation to clinical trials with NXD30001 in patients with GBM.

Materials and Methods

Transgenic Animals and Tumor Induction Procedures

All mouse procedures were performed in accordance with Tufts University’s recommendations for the care and use of animals and were maintained and handled under protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Intracranial glioblastoma tumors were induced as follows: adult compound Col1a1tm2(CAG-EGFR*)Char/tm2(CAG-EGFR*)Char; Cdkn2atm1Rdp/tm1Rdp; Ptentm1Hwu/tm1Hwu; Tg(CAG-luc)C6Char conditional transgenic animals (14, 15) of 3 months of age or above were anesthetized with an IP injection of Ketamine/Xylazine (ketamine 100–125 mg/kg, xylazine 10–12.5 mg/kg), mounted on a stereotaxic frame and processed for injections as described before (14) using a pulled glass pipet mounted onto a Nanoject II injector (Drummond Scientific Company) to inject 250 nL aliquot of an adeno-CMV-Cre virus (GTVC, U Iowa) over a period of 10 minutes. Following retraction of the pipet, the burr hole was filled with sterile bone wax, the skin is drawn up and sutured and the animal is placed in a cage with a padded bottom atop a surgical heat pad until ambulatory.

Cell culture

All mouse and human GBM primary cell cultures derived from tumors were maintained in DMEM media supplemented with 10% (v/v) of FBS as described (14, 16). Primary cultures of mouse astrocytes were established according to published protocols (17). 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-AAG) was obtained from Sigma.

Immunoblot analysis

Western blots were performed as follows: total cell lysates were harvested using RIPA buffer that is supplemented with 5 mM Na3VO4 and protease inhibitor cocktail. Concentrations of lysates were determined using protein quantification reagents (Bio-Rad). 40 µg of lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and electrotransfered to PVDF membrane (Immobilon P, Millipore). Blots were blocked in Tris-buffered saline 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20 (TBS-T), 1% (wt/v) BSA and 5% (wt/v) non fat dry milk (Bio-Rad) for 1 hour on a shaker. Primary antibodies were added to blocking solution and incubated overnight at 4°C on a shaker. Blots were washed several times with TBS-T-BSA and secondary antibodies were added at 1:10000 dilutions into TBS-T BSA and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature on a shaker. After several washes, enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reactions were performed as described by the manufacturer (Western Lightning Kit, Perkin Elmer). The antibodies and respective dilutions used in these studies are anti EGFR (#2232, Cell Signaling Technology 1:2000), anti total AKT (#9272, Cell Signaling Technology 1:5000), anti dynamin (#610245, BD Transduction Laboratories 1:2000), anti CDK4 (#SC-260, Santa Cruz Biotechnology 1:5000) and anti Cyclin D1 (#SC-450, Santa Cruz Biotechnology 1:250) cleaved-caspase 3 (#9661, Cell Signaling Technology 1:1000).

Cell proliferation and apoptosis analysis

GBM cells were seeded at a density of 5000 per well on 96-well plates, cultured in the presence of drugs or vehicle for 36 hours, and subjected to an XTT cell proliferation assay (Roche) in quadruplicates according to the manufacturer’s specifications. For detection of apoptosis, cells were plated in 8 wells Chamber slides (BD Biosciences) at a density of 10,000 cells per well and treated with NXD30001 for the indicated time, fixed with fresh 4% PFA for 15 minutes and stained with Hoechst 33258 dye (5µg/ml for 5 minutes) and scored for apoptosis. Apoptotic cells were visualized by fluorescence microscopy and reported as percent apoptotic pyknotic nuclei over total nuclei as averages of three independent areas.

Histology

Deeply anesthetized animals were transcardially perfused with cold PBS followed by freshly made 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were excised, rinsed in PBS, and post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 30 minutes. Serial 2 mm coronal sections were cut using a brain mold. Fixed tissues were embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5–10 µM and stained with H&E (Sigma) for histopathological analysis.

Pharmacokinetic Studies

PK experiments were conducted in mice to evaluate the exposure of NXD30001 in plasma and brain tissues following a single dose or a repeat dose schedule (every other day for a total of 7 doses) of intravenous administration. The study was performed at BioDuro (headquarters in San Diego, CA). CD-1 mice (8 weeks of age, male, body weight: 29–36 g) were used for the study. NXD30001 was reconstituted in the vehicle (6% DMA, 10% Soybean Oil, 5% Tween 80, and 79% water) at 7 mg/mL for the single dose regimen and 2.5 mg/mL for the repeat dose schedule. Three mice per time point were dosed at 70 mg/kg and dosing volume of the drug solutions was adjusted with vehicle such that dosage of each mouse is corrected for fasted body weight. The concentration of dosing solution was confirmed by LC-MS/MS. Blood samples via cardiac puncture and brain tissues were collected at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, and 48 hours following administration of the compound. The blood samples were temporarily put on ice and then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 3 to 5 minutes to separate for plasma. Plasma samples were stored at −20°C until bioanalysis. The brain samples were washed quickly with saline at 4°C and homogenized. The compounds in the plasma and brain homogenates were extracted with 10 volumes of MTBE (Methyl Tertiary Butyl Ether) and supernatants were dried under N2. The concentrations of the test compounds in plasma and brain were determined using a LC-MS/MS method. An Agilent Zorbax C18 column (2.1 × 50 mm, 3.5 µm) was used at a temperature of 25°C. The mobile phase A was water (0.1% formic acid) and the mobile phase B was methanol (0.1% formic acid). The flow rate was 400 µl/min and the injection volume was 10 µl. The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) of the bioanalytical method was 1 ng/mL for plasma and 0.5 ng/mL for brain. The range was 1–2000 ng/mL for plasma and 0.5–500 ng/mL for brain. All solvents and chemicals were of analytical grade or better. PK parameters were calculated using WinNonlin (V5.2.) and non-compartment model. Concentrations of NXD30001 and 17-AAG were measured in brain tissues of BT474 xenograft-bearing NCR-Nude mice after single i.p. injections at the indicated concentrations after 6, 12, 24 and 48 hours (13). Concentrations of drugs from brain homogenates were determined by LC/MS/MS. A Shimadzu VP System (column: 2 × 10 mm Peek Scientific Duragel G C18 guard cartridge) was used. The mobile phase A was water (0.2% formic acid) and the mobile phase B was methanol (0.2% formic acid). The flow rate was 400 µl/min and the injection volume was 100 µl. The gradient was 5% B for 0.5 minutes and then 5–95% B in 2 minutes. Applied Biosystems/MDS SCIEX API 3000 was used. The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) of the bioanalytical method was 4.6 ng/mL for both NXD30001 and 17-AAG.

Tumor Growth Monitoring by Bioimaging and NXD30001 treatment of mice

Growth of GBM tumors was monitored noninvasively using bioluminescence as described previously (15), using the IVIS 200 imaging system (Xenogen). Live imaging of animals was performed as follows: areas of focus for imaging were depilated using commercial depilatory creams. All of the images were taken 10 min after IP injection of luciferin (225 mg/kg, Xenogen) to allow proper distribution of luciferin, with a 60 seconds photon acquisition during which mice were sedated via continuous inhalation of 3% isoflurane. Signal intensity was quantified for defined regions of interest as photon count rate per unit body area per unit solid angle subtended by the detector (units of photons/s/cm2/steradian). All image analyses and bioluminescent quantification were performed using Living Image software v. 2.50 (Xenogen). NXD30001 was dissolved in vehicle (10% v/v N,N-Dimethylacetamide, 5% v/v Tween 20, 15% v/v Cremophor, 70% v/v Saline). Mice bearing tumors that have reached 106 relative light units were dosed by IP injections with 100 mg/kg thrice weekly for two weeks followed by twice weekly for the times indicated.

IC50 and Statistical analysis

IC50 values and curve-fitting were performed using Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software) with nonlinear regression analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using the two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test. Comparison of overall survival rates was done using a log-rank analysis and Kaplan-Meier curves generated using Prism 5.0. P values were calculated using a Mantel-Cox two-tailed test for significance.

Results

NXD30001 accumulates in brain tissue

A major impediment to robust drug efficacy against GBM is the inability for therapeutic compounds to access tumor cells that have migrated into healthy parenchyma and that are thus protected by an intact blood brain barrier (BBB). Pharmacokinetic studies of NXD30001 in mice indicate that intravenously (i.v.) administered NXD30001 disperses with favorable kinetics and accumulates well within brain tissues (Table 1A). We further assessed NXD30001’s ability to penetrate the BBB and its CNS retention by measuring its concentration in brain tissues following intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections (Table 1B). NXD30001 reached a maximal concentration of 823 ng/g after a single dose of 100mg/kg after 12 hr. Conversely, 17-AAG’s accumulation in mouse brain rapidly declines to undetectable levels 6 hours after a single i.p. dose. In addition, multiple dose PK experiment (seven every other day i.v. dosing at 25mg/kg) was conducted to determine if there is drug accumulation with repeat dosing (Table 1A). Despite lower dose used in the repeat dose experiment, plasma and brain concentrations after multiple doses are greater than or similar to those after a single i.v. dose at 70mg/kg. Similarly, plasma and brain AUC values are comparable for both single and repeat dose experiments. The ratios of brain/plasma AUC are not significantly different. These results suggest some accumulation of NXD30001 after the repeat dose although very little NXD30001 was detected in plasma or brain prior to the last dose (less than 10ng/mL or 10ng/g).

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetic study of NXD30001 in mice. (A) PK profile in plasma and brain tissues after a single intravenous injection of 70 mg/kg or after repeated intravenous injections at 25 mg/kg every other day for a total of 7 doses. (B) Brain concentrations of NXD30001 and 17-AAG following intraperitoneal injections.

| (A) PK | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC(0-t) (ng.hr/mL)* (ng.hr/g) |

Cmax (ng/g) | C0 (ng/mL) | Tmax (hr) | T1/2 (hr) | CL (mL/min/kg) |

Vd (L/kg) | Ratio of AUC(0-t) (brain/plasma) |

||

| Single Dose | |||||||||

| Plasma* | 5346 | NA | 2140 | NA | 2.74 | 217 | 51.5 | NA | |

| Brain | 1073 | 223 | NA | 0.5 | 4.07 | NA | NA | 0.201 | |

| Repeated Doses | |||||||||

| Plasma* | 6960 | NA | 4530§ | NA | 5.4 | 59.8 | 27.9 | NA | |

| Brain | 940 | 210 | NA | 0.25 | 8.99 | NA | NA | 0.135 | |

| (B) Brain | |||||||||

| Time (hr) | NXD30001 (ng/g) | 17-AAG (ng/g) | |||||||

| 100 mg/kg | 150 mg/kg | 75 mg/kg | |||||||

| 6 | 675.5 | 1439.5 | 2.6 | ||||||

| 12 | 823 | 3424 | ND | ||||||

| 24 | 271 | 899.5 | ND | ||||||

| 48 | 10.7 | 115.5 | ND | ||||||

Definitions, AUC0-t: Area under the curve from the time of dosing to the time of the last observation; Cmax: Maximum concentration; C0: Concentration at time 0; Tmax: Time of the maximum concentration; T1/2: Terminal half-life; CL: Clearance; Vd: Volume of distribution at terminal phase; (A) Concentrations of NXD30001 in plasma and brain homogenates were determined by LC/MS/MS after a single i.v. injection at 70 mg/kg or after repeared i.v. injections at 25 mg/kg every other day for a total of 7 doses. NA; not applicable.

the concentration shown is the average concentration at 0.5 hr rather than C0. (B) Brain concentrations of HSP90 inhibitors in mice. Concentrations of NXD30001 and 17-AAG in brain homogenates were determined by LC/MS/MS after a single i.p injection. ND; not detected

NXD30001 is a potent inhibitor of GBM cell proliferation in vitro

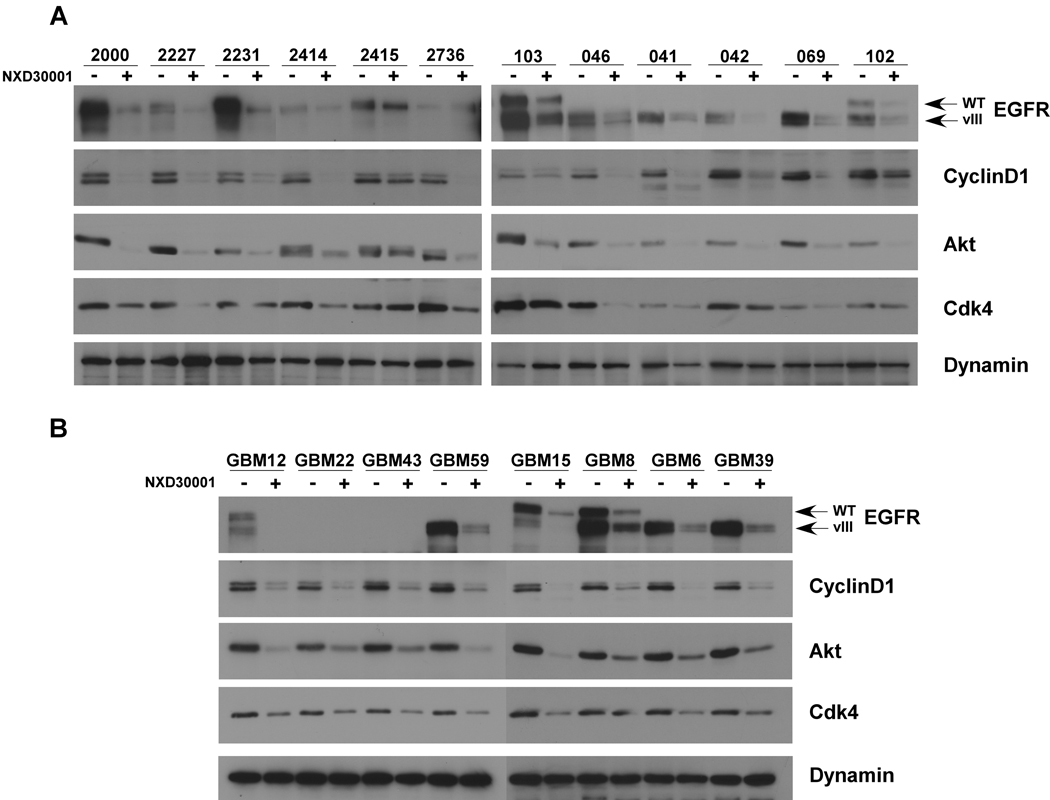

Having shown that NXD30001 has promising pharmacokinetic parameters in vivo, we treated EGFR-driven mouse GBM tumor primary cell cultures (14) and primary astrocytes cultures with NXD30001. Treatment of these cells with NXD30001 led to a dose and time dependent inhibition of GBM cell growth but not of astrocytes (Fig. 1A, B). The growth inhibition that is observed in Fig. 1A & B was concurrent with the degradation of the Hsp90 client proteins EGFR, Akt, Cdk4 and Cyclin D1 (Fig. 1C). It has been previously demonstrated that Hsp90 inhibition in gliomas can result in apoptosis (18). Similarly, the growth inhibition observed correlated with a 10-fold increase in apoptosis level in these cells as measured by the production of pyknotic nucleated cells and the appearance of cleaved-caspase 3 (Fig. 2). Taken together, these data demonstrate that NXD30001 prevents GBM cell growth by promoting apoptosis and degradation of Hsp90 client proteins. We then expanded these studies using a panel of primary GBM tumor lines established from mouse tumors as described (14). In these cells, NXD30001 inhibited cell proliferation with nanomolar IC50 potency and was reliably more potent than 17-AAG (Table 2). To correlate these results to human GBMs, we tested NXD30001 on a panel of human GBM primary cultured cells. Treatment of these cells with NXD30001 also demonstrated nanomolar potency and enhanced efficacy over 17-AAG (Table 2). When compared directly against 17-AAG, NXD30001 was between 0.4- and 9.8- fold more active at inhibiting GBM tumor cell growth. The cellular response to Hsp90 inhibition by NXD30001 were assessed by comparing the expression levels of the Hsp90 client proteins EGFR, Akt, CyclinD1 and CDK4 by immunoblot analysis before and after NXD30001 treatment (Fig. 3). In all cultures tested, treatment of GBM cells with NXD30001 led to a significant reduction in the levels of these client proteins.

Figure 1.

Efficacy of NXD30001 on GBM cells. Mouse primary cultures of astrocytes and GBM cell cultures (GBM-1 & -2) were grown in A, the presence of increasing concentrations of NXD30001 for 24 hours, counted and cell numbers plotted as percent of untreated cells. B, Cells were treated with 250 nM of NXD30001 for the indicated amount of time and viable cells counted and plotted as percent of untreated cells. C, Western blot showing the depletion of the indicated Hsp90 client proteins (and dynamin as a control) in GBM-1 & -2 cultures and primary mouse astrocytes treated with 250 nM of NXD30001 for the indicated times. GBM-1 cells co-express wild type and vIII EGFR and GBM-2 cells express EGFR vIII. All data points are reported as mean values of triplicates, error bars represent standard deviation, (S.D.). * and ** indicate P < 0.0001 t-test.

Figure 2.

NXD30001 treatment of GBM cells leads to apoptosis. A, Cells were exposed to 250 nM of NXD30001 for the indicated times, fixed, stained and levels of apoptosis reported as percentage of pyknotic cells relative to total number of cells. B, Cells were treated with 250 nM of NXD30001 for the indicated times and lysates processed for western blot analysis to detect the levels of cleaved-caspase 3.

Table 2.

Cytotoxicity of NXD30001 and 17-AAG in mouse and human GBM cultures as determined by cell proliferation assays

| NXD30001 | 17-AAG | |

|---|---|---|

| GBM Cultures | IC50 (nM)* | IC50(nM)* |

| Mouse | ||

| 2414 | 31.7 ± 4.9 | 205.1 ± 13.1 |

| 46 | 54.3 ± 12.5 | 91.9 ± 1.4 |

| 69 | 73.4 ± 2.5 | 91 ± 4.3 |

| 42 | 73.8 ± 0.7 | 165.5 ± 24.9 |

| 2736 | 77.6 ± 2.8 | 381 ± 24.1 |

| GBM-1 | 78.3 ± 8.3 | 207.5 ± 9.6 |

| 41 | 80.2 ± 5.9 | 100.2 ± 5.0 |

| GBM-2 | 110.8 ± 9.4 | 1096.4 ± 118.6 |

| 2000 | 115.4 ± 9.4 | 344.8 ± 75.5 |

| 2227 | 134.3 ± 7.7 | 712 ± 54.4 |

| 2231 | 146.1 ± 3.7 | 737.3 ± 72.0 |

| 2415 | 251.1 ± 57.7 | 328.8 ± 50.1 |

| 102 | 360.5 ± 21.6 | 626.2 ± 6.0 |

| 103 | 575.6 ± 14.8 | 793.5 ± 28.7 |

| Human | ||

| GBM15 | 60.7 ± 0.5 | 110.4 ± 13.4 |

| GBM43 | 86.3 ± 0.2 | 86.9 ± 2.3 |

| GBM39 | 111.6 ± 1.0 | 241.7 ± 1.2 |

| GBM59 | 232 ± 13.2 | 211.2 ± 11.0 |

| GBM6 | 1217.5 ± 35.1 | 531.7 ± 5.0 |

| GBM12 | 2334 ± 60.0 | 2575.9 ± 166.5 |

| GBM22 | 5261.6 ± 152.2 | 4668.2 ± 148.0 |

| GBM8 | 5691.3 ± 449.6 | 8010.8 ± 542.6 |

Results are presented as the mean of three independent experiments ± standard deviation.

Figure 3.

NXD30001 depletes Hsp90 client proteins in GBM cells. NXD30001 treatment of A, mouse and B, human primary GBM culture cells deplete the Hsp90 client proteins EGFR, Akt, Cdk4 and CyclinD1. Cells were treated with 250 nM of NXD30001 or vehicle for 24 hours before preparing lysates. Equivalent amount of lysates were subjected to western blot using antibodies against the indicated proteins.

NXD30001 treatment increases survival and induces GBM tumor regression in mice

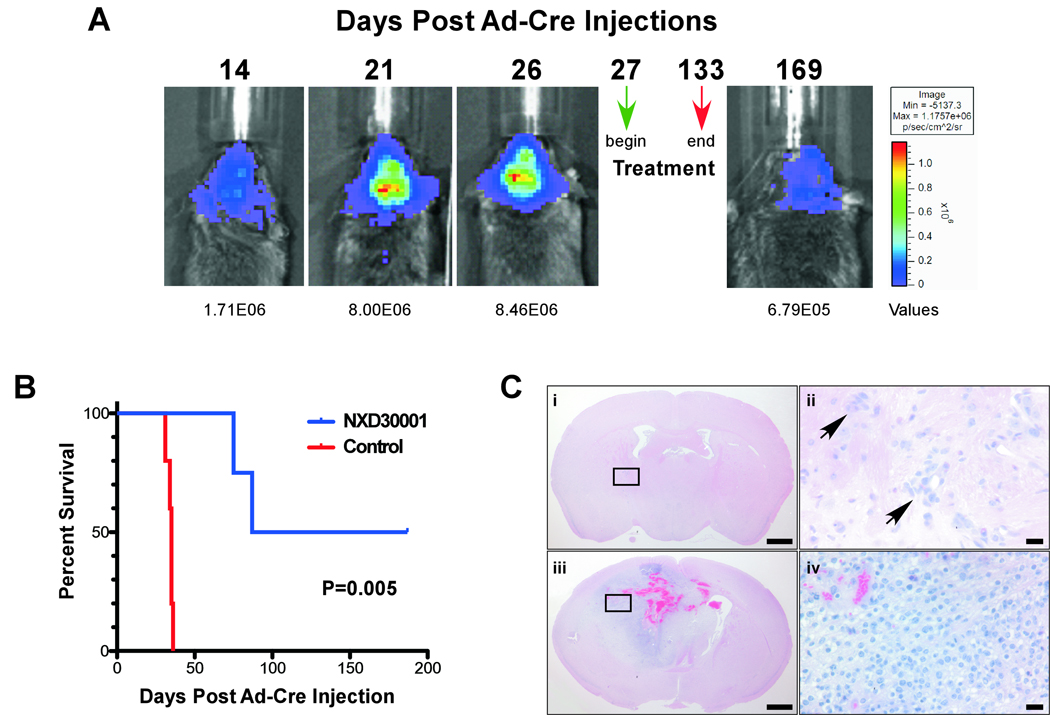

In light of these results, we then evaluated the efficacy of NXD30001 in mice bearing GBM tumors. First, we crossed our EGFR-based model to a conditional luciferase reporter strain that we have recently characterized (15) and in which we demonstrated a robust relationship between bioluminescent light emission and GBM tumor volume. Tumor growth is therefore monitored longitudinally and increases in bioluminescence imaging (BLI) output linearly correspond to GBM volume. More importantly, this approach allows for consistency in initiation of treatment. The rationale behind the utilization of this strain as a reporter of tumor size, is that only cells that are exposed to Cre recombinase, and therefore giving rise to EGFR-dependent GBMs expresses the bioluminescent marker luciferase. This approach provides a high signal to noise ratio, which is a foremost requirement for quantitative bioimaging.

Cohorts of animals were established and developing brain tumors were monitored periodically by BLI to assess relative tumor volumes and growth rates. Animals reaching a bioluminescent signal output of >8×106 p/sec/cm2/sr were randomized to treatment with either vehicle or 100 mg/kg of NXD30001 i.p. thrice weekly (X2) then twice weekly for the remaining course of treatment. Once treatment was initiated, BLI monitoring was suspended since luciferase is a client protein of Hsp90 (19), potentially inducing compromising read out accuracy. Mice were treated for over 100 days or until moribund and the surviving mice were reimaged periodically post treatment discontinuation until termination of study (Fig. 4A). Cohorts of treated and vehicle control untreated mice were monitored and Kaplan-Meier survival curves established (Fig. 4B). All of the vehicle control treated mice succumbed to GBM within ~30 days post Ad-Cre injection whereas half of the treated animals survived longer than 180 days (Fig. 4B), at which point they were processed for histopathological analysis. Treatment of brain tumor-bearing mice with NXD30001 resulted in a statistically significant prolongation in survival. For these surviving animals, histological analysis of H&E stained paraffin embedded brain sections revealed the presence of few remaining tumor cell clusters (Fig. 4C arrows). It has been reported that exposure to 17-AAG, which is currently in clinical evaluation for various cancers (20), results in dose-limiting hepatotoxicity. In contrast, both short and long term NXD30001 exposure in mice does not result in hepatotoxicity (data not shown and (13)).

Figure 4.

NXD30001 treatment of GBM tumor mice. A, Study paradigm. Example of BLI outputs for a given mouse imaged 14, 21 and 26 days post tumor induction to determine the time of treatment initiation (>8×106 p/sec/cm2/sr) (green arrow). Mice were dosed three times weekly (×2 weeks) and then twice weekly at 100 mg/kg in vehicle for >100 days. Control mice were given vehicle only. Animals were re-imaged periodically over a period of time post treatment (a 36 day post-cessation of Rx is shown). B, Kaplan-Meier survival curves of EGFRvIII-driven GBM-bearing mice treated with NXD30001 or placebo according to the paradigm in (A). N=5 control, N=4 treated. C, Photomicrographs of H&E-stained paraffin-embedded coronal brain sections (at the level of Ad-Cre injections) of treated (i & ii) and control vehicle-treated (iii & iv) mice. Panels’ ii & iv are high magnification photomicrographs of i & iii (insets) respectively. Scale bars, i & iii; 1 mM, ii & iv; 25 µM.

Discussion

The deadly nature of GBM lies in their inherent ability to migrate and infiltrate within the non-diseased brain. Recurrence is the norm and typically occurs within a few centimeters from the tumor margins, an area physiologically and physically protected from the effects of therapeutic agents by the BBB. As such, the ineffectiveness of systemically administered chemotherapeutic drugs in treating gliomas has long been attributed to the impermeability of the BBB (21, 22). Therefore, successful agents against GBM will require a heighten penetration of the BBB and superior CNS retention kinetics. The recent inclusion of the lipophilic compound temozolomide as a major component of first line treatment for GBM underscores these principles (23, 24).

Recent advances in the molecular characterization of GBMs, indicate that single target agent mono-therapies are less likely to produce significant impact on the treatment front (25). It is also becoming clear that successful treatments against GBM will arise from multi target approaches. Single agents capable of striking multiple targets at once will offer a tremendous advantage over combinatorial drug cocktails given the often synergistic multi drug toxicities.

Inhibition of Hsp90 activity results in the degradation of several proteins that play key roles in tumorigenesis. 17-AAG is a well-known Hsp90 inhibitor that is currently the farthest advanced in clinical evaluation for solid tumors (10). Given that efficient penetration through the BBB and prolonged CNS retention are absolutely necessary for successful treatment of gliomas, our findings that NXD30001 has superior brain PK to 17-AAG have significant clinical implications and underscore NXD30001 applicability for GBM treatment.

Our In vitro studies demonstrated a potent inhibition of GBM growth by NXD30001. This successful inhibition of cell growth and induction of cell death can be explained by the relative biological credence GBM cells impart on Hsp90 client protein targets for survival. For example, the EGFR-PI3K-Akt axis, which is reinforced by loss of PTEN, is a key driver of GBM survival through a variety of mechanisms (reviewed in (26)). Elimination of expression of both EGFR and Akt, considered a nodal point in this pathway, in GBMs, robs these cells from potent pro-survival signals. In addition, loss of Ink4a in these tumors shifts the CDK4/CyclinD equilibrium towards duplex formation and deregulated cell cycle progression. Similarly, inhibition of Hsp90 leads to considerable decreases in the levels of both CDK4 and CyclinD1, thus counteracting the effects of the functional loss of Ink4a in tumor cells.

These observations were correlated in vivo by a prolonged statistically significant survival of GBM-bearing mice when treated with NXD30001. The presence of these cells in the long-term surviving mice suggest that a protracted and sustained regimen in treating patients with NXD30001 may be required for complete tumor eradication or to maintain the remaining cells in a non-proliferative state. Given the absence of toxicity observed in the treated animals, extended treatment is realistic.

Strong biological rationales have driven the use of Hsp90 inhibitors for the treatment of solid tumors, some of which are in various phases of clinical trials (20). Our data demonstrate that NXD30001 treatment of EGFR, Ink4a/Arf-PTEN-null driven de novo GBM tumors in a genetically engineered mouse model is an effective therapeutic strategy. Given NXD30001’s promising pharmacokinetic profile, persistent treatment for GBM patients is therefore a realistic option. The preclinical work that is described herein suggests that NXD30001 may prove to have therapeutic efficacy in GBM patients and should be further pursued clinically.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Drs. Kenneth Hung and Jaime Acquaviva for critical review of the manuscript.

Grant Support: A.C. was supported by NIH grants U01CA141556-0109, ACS Research Scholar Grant 117409, Tufts Medical Center Research Award and The Neely Foundation for Cancer Care and Research.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: The following authors H.Z., S.W., R.T.B., S.B., N.W. and A.C. disclose no conflict of interest. R.C., A.E.R., and Z.J., are all employees of Nexgenix Pharmaceuticals Holdings Ltd., a privately held, for-profit entity which owns the rights to NXD30001 and its analog compounds and is pursuing a development program for these compounds for glioblastoma and other indications.

References

- 1.Kleihues P, Cavenee WK. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Nervous System. Lyon: IARC Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005 Mar 10;352(10):987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang X, et al. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science. 2008 Sep 26;321(5897):1807–1812. doi: 10.1126/science.1164382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLendon R, Friedman A, Bigner D, et al. Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2008 Oct 23;455(7216):1061–1068. doi: 10.1038/nature07385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verhaak RG, Hoadley KA, Purdom E, et al. Integrated genomic analysis identifies clinically relevant subtypes of glioblastoma characterized by abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell. Jan 19;17(1):98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phillips HS, Kharbanda S, Chen R, et al. Molecular subclasses of high-grade glioma predict prognosis, delineate a pattern of disease progression, and resemble stages in neurogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2006 Mar;9(3):157–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim WY, Sharpless NE. The regulation of INK4/ARF in cancer and aging. Cell. 2006 Oct 20;127(2):265–275. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirai H, Kawanishi N, Iwasawa Y. Recent advances in the development of selective small molecule inhibitors for cyclin-dependent kinases. Curr Top Med Chem. 2005;5(2):167–179. doi: 10.2174/1568026053507688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matts RL, Manjarrez JR. Assays for Identification of Hsp90 Inhibitors and Biochemical Methods for Discriminating their Mechanism of Action. Curr Top Med Chem. 2009 Oct 28; doi: 10.2174/156802609789895692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim YS, Alarcon SV, Lee S, et al. Update on Hsp90 Inhibitors in Clinical Trial. Curr Top Med Chem. 2009 Oct 28; doi: 10.2174/156802609789895728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barluenga S, Fontaine JG, Wang C, et al. Inhibition of HSP90 with pochoximes: SAR and structure-based insights. Chembiochem. 2009 Nov 23;10(17):2753–2759. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barluenga S, Wang C, Fontaine JG, et al. Divergent synthesis of a pochonin library targeting HSP90 and in vivo efficacy of an identified inhibitor. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2008;47(23):4432–4435. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang C, Barluenga S, Koripelly GK, et al. Synthesis of pochoxime prodrugs as potent HSP90 inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009 Jul 15;19(14):3836–3840. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu H, Acquaviva J, Ramachandran P, et al. Oncogenic EGFR signaling cooperates with loss of tumor suppressor gene functions in gliomagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Feb 24;106(8):2712–2716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813314106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woolfenden S, Zhu H, Charest A. A Cre/LoxP conditional luciferase reporter transgenic mouse for bioluminescence monitoring of tumorigenesis. Genesis. 2009 Oct;47(10):659–666. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarkaria JN, Carlson BL, Schroeder MA, et al. Use of an orthotopic xenograft model for assessing the effect of epidermal growth factor receptor amplification on glioblastoma radiation response. Clin Cancer Res. 2006 Apr 1;12(7 Pt 1):2264–2271. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinstein DE. Isolation and purification of primary rodent astrocytes. Curr Protoc Neurosci. 2001 May;Chapter 3(Unit 3):5. doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0305s00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nomura M, Nomura N, Newcomb EW, Lukyanov Y, Tamasdan C, Zagzag D. Geldanamycin induces mitotic catastrophe and subsequent apoptosis in human glioma cells. J Cell Physiol. 2004 Dec;201(3):374–384. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galam L, Hadden MK, Ma Z, et al. High-throughput assay for the identification of Hsp90 inhibitors based on Hsp90-dependent refolding of firefly luciferase. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007 Mar 1;15(5):1939–1946. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim YS, Alarcon SV, Lee S, et al. Update on Hsp90 Inhibitors in Clinical Trial. Curr Top Med Chem. 2009;9(15):1479–1492. doi: 10.2174/156802609789895728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muldoon LL, Soussain C, Jahnke K, et al. Chemotherapy delivery issues in central nervous system malignancy: a reality check. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Jun 1;25(16):2295–2305. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.9861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nies AT. The role of membrane transporters in drug delivery to brain tumors. Cancer Lett. 2007 Aug 28;254(1):11–29. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stupp R, van den Bent MJ, Hegi ME. Optimal role of temozolomide in the treatment of malignant gliomas. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2005 May;5(3):198–206. doi: 10.1007/s11910-005-0047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T, et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005 Mar 10;352(10):997–1003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stommel JM, Kimmelman AC, Ying H, et al. Coactivation of receptor tyrosine kinases affects the response of tumor cells to targeted therapies. Science. 2007 Oct 12;318(5848):287–290. doi: 10.1126/science.1142946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Engelman JA. Targeting PI3K signalling in cancer: opportunities, challenges and limitations. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009 Aug;9(8):550–562. doi: 10.1038/nrc2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]