Abstract

cspA (for cell surface protein A) encodes a repeat-rich glycophosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored cell wall protein (CWP) in the pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. The number of repeats in cspA varies among isolates, and this trait is used for typing closely related strains of A. fumigatus. We have previously shown that deletion of cspA is associated with rapid conidial germination and reduced adhesion of dormant conidia. Here we show that cspA can be extracted with hydrofluoric acid (HF) from the cell wall, suggesting that it is a GPI-anchored CWP. The cspA-encoded CWP is unmasked during conidial germination and is surface expressed during hyphal growth. Deletion of cspA results in weakening of the conidial cell wall, whereas its overexpression increases conidial resistance to cell wall-degrading enzymes and inhibits conidial germination. Double mutant analysis indicates that cspA functionally interacts with the cell wall protein-encoding genes ECM33 and GEL2. Deletion of cspA together with ECM33 or GEL2 results in strongly reduced conidial adhesion, increased disorganization of the conidial cell wall, and exposure of the underlying layers of chitin and β-glucan. This is correlated with increasing susceptibility of the ΔcspA, ΔECM33, and ΔcspA ΔECM33 mutants to conidial phagocytosis and killing by human macrophages and hyphal damage induced by neutrophils. However, these strains did not exhibit altered virulence in mice with infected lungs. Collectively, these results suggest a role for cspA in maintaining the strength and integrity of the cell wall.

The saprophytic mold Aspergillus fumigatus is an emerging pathogen and the major causative agent of invasive aspergillosis, a life-threatening disease primarily affecting immunocompromised patients (12, 16, 38).

Molecular analyses have revealed numerous virulence attributes that enable A. fumigatus to infect the human host, including the production of toxins, the ability to acquire nutrients and iron under limiting conditions, and the presence of protective mechanisms that degrade oxygen radicals released by the host immune cells (7).

The fungal cell wall plays a crucial role in infection. In A. fumigatus, as in other pathogenic fungi, the cell wall protects the fungus and interacts directly with the host immune system. It is an elastic, dynamic, and highly regulated structure and is essential for growth, viability, and infection. The fungal cell wall is a unique structure and therefore a specific target for antifungal drugs. The cell wall of A. fumigatus is composed of a polysaccharide skeleton interlaced and coated with cell wall proteins (CWPs). The main building blocks of the polysaccharide skeleton are an interconnected network of glucan, chitin, and galactomannan polymers (26). The major class of fungal CWPs is the glycophosphatidylinositol (GPI)-modified proteins (8–11, 14).

We recently identified and characterized A. fumigatus CWPs containing tandem repeats (27). Repeats are hot spots of genetic change: because of replication slippage and recombination, repeats can undergo rapid changes in copy number, leading to natural variability among different isolates and allowing faster adaptation to new environments (23). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, for example, an increase in the number of coding repeats in the FLO1 adhesin-encoding gene correlates with an increase in adhesion to the plastics used in medical devices (44–46). Similarly, repeat variation in the Candida albicans ALS3 adhesin changes its cellular binding specificity (34). Moreover, clinical C. albicans isolates show variability in the number of repeats in various cell surface genes, suggesting that this recombination process could play a role during infection, allowing cells to adapt rapidly to a fluctuating environment and/or evade the host immune system (34, 49, 50).

We identified four genes encoding putative A. fumigatus GPI-anchored CWPs (AFUA_3G08990 [termed cspA for cell-surface protein A [4], AFUA_2G05150 [MP-2], AFUA_4G09600, and AFUA_6G14090) containing variable numbers of repeats among patient isolates (27). In A. fumigatus WT strain AF 293, cspA encodes a 433-amino-acid-long protein containing a putative leader sequence and GPI modification site. cspA lacks recognizable catalytic domains, and homologous genes are found only in species of Aspergillus. Most interesting is that the gene encodes a 188-amino-acid-long serine-threonine-proline-rich N-terminal region followed by a large size-variable six-amino-acid serine-proline [P-G-Q-P-S-(A/V)]-rich tandem repeat region showing significant homology to the repeat domains found in mammalian type XXI collagen. The number of repeats varies between 18 and 47 (24 to 65% of the length of the protein) in different isolates of A. fumigatus. The strains used in this study, AF 293 and CBS 144.89, contain 32 and 28 repeats, respectively.

Deletion of cspA resulted in a phenotype characterized by rapid conidial germination and reduced adhesion to extracellular matrix (ECM), which suggests that cspA participates in defining cell surface properties. Highlighting the importance of this gene, Balajee et al. (4) showed that variations in the cspA nucleotide repeat sequence can be used to type closely related pathogenic isolates of A. fumigatus and identify outbreak clusters occurring in hospitals (3, 4).

In this work, we undertook a detailed study of cspA. We analyzed the expression pattern of the protein encoded by cspA and its attachment to the cell wall. We prepared and analyzed A. fumigatus mutant strains in which cspA was overexpressed or deleted in combination with additional cell wall-associated genes. Results indicate that the protein encoded by cspA is GPI anchored to the cell wall and is unmasked during conidial germination. cspA deletion weakens the cell wall and results in rapid conidial germination, whereas cspA overexpression increases conidial resistance to protoplasting and inhibits conidial germination. cspA functionally interacts with the genes ECM33 and GEL2, which encode cell wall-associated proteins, resulting primarily in profound defects in conidial cell wall organization. The cspA ECM33 double mutant exhibited greater susceptibility to killing by human macrophages and hyphal damage induced by neutrophils. The implications of our findings are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions.

Strains (Table 1) were maintained in glycerol stock and cultured on YAG agar (0.5% [wt/vol] yeast extract, 1% [wt/vol] glucose, and 10 mM MgCl2) supplemented with trace elements and vitamins (2) at 37°C for 3 days to obtain conidia. Conidia were collected in double-distilled water (DDW) containing 0.02% (vol/vol) Tween 80, washed twice in DDW, and stored at 4°C. A. fumigatus liquid cultures used for genomic DNA and protein preparation were grown on YAG agar at 37°C.

Table 1.

List of A. fumigatus strains

| Strain or description | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| AF 293 | Wild type | G. S. May |

| AF 293.1 | pyrG deficient | G. S. May |

| CBS 144.89 | Wild type | J. P. Latge |

| AF 293 ΔcspA | Afu3g08990::hph | Levdansky et al. (27) |

| CBS 144.89 ΔcspA | Afu3g08990::phl | This work |

| ΔAfu6g14090 | Afu6g14090::hph | Levdansky et al. (27) |

| ΔcspA ΔAfu6g14090 | Afu3g08990::phl Afu6g14090::hph | This work |

| ΔAfu2g05150 | Afu2g05150::hph | Levdansky et al. (27) |

| ΔcspA ΔAfu2g05150 | Afu3g08990::phl Afu2g05150::hph | This work |

| ΔECM33 | Afu4g06820::hph | Romano et al. (37) |

| ΔcspA ΔECM33 | Afu3g08990::phl Afu4g06820::hph | This work |

| ΔGEL2 | Afu6g11390::phl | I. Mouyna (J. P. Latge) |

| ΔcspA ΔGEL2 | Afu3g08990::hph Afu6g11390::phl | This work |

| ΔChsG | Afu3g14420::phl | E. Mellado (J. P. Latge) |

| ΔcspA ΔChsG | Afu3g08990::hph Afu3g14420::phl | This work |

| cspA-ovx | pyrG1::AMA1-pyr4-Afu3g08990 | This work |

| cspA-myc | Afu3g08990::hph-Afu3g08990 (myc tagged) | Levdansky et al. (27) |

DNA analysis.

A. fumigatus genomic DNA was extracted using the MasterPure yeast DNA purification kit (Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison, WI) with modifications for A. fumigatus as described by Jin et al. (22). Southern hybridization analysis was performed as described previously (20). Briefly, 10 μg of fungal genomic DNA was digested with XhoI (pΔcspA-phl and pΔcspA-hyg plasmids) or XbaI (pΔECM33-phl plasmid) and run on a 1% (wt/vol) agarose gel. The cleaved DNA was transferred to a Nytran N nylon membrane (Schleicher & Schuell Bioscience Inc., Keene, NH) and hybridized with an [α-32P]dCTP-radiolabeled cspA 5′ or ECM33 5′ probe at 65°C. The probes were generated by PCR with primers cspA-S5′ and cspA-S3′ or ECM33-S5′ and ECM33-S3′, respectively (a comprehensive list of primers is given in Table 2).

Table 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer name | Sequence |

|

|---|---|---|

| 5′ primer | 3′ primer | |

| AscI-ECM33 | ATGGCGCGCCCCCGTAGTCCAGGTGATGAC | ATGGCGCGCCGACCGGTCGGTCCTTGTA |

| Acc65-phl | ATGGTACCACAGGCTCAAATCAATAAGAAG | ATGGTACCTGCACCATATGCGGTGTGAAATA |

| ECM33-S′ | TCATCATTCTTCTTCGTCCAACG | TTGATGGTCGAGCAGGAGGAGTAGC |

| AscI-cspA | ATGGCGCGCCAGGTAGCGGAATGGAAATAGACG | ATGGCGCGCCGTAAGGACAGACACCACCTGAC |

| AflII-phl | ATCTTAAGTGCACCATATGCGGT GTGAAATA | |

| CSP-S′ | TATCCAATCAAGAGAGATCCTTG | AGACTCTTATGTGAGAGCCTGTCG |

| NotI-cspA | ATGCGGCCGCAGGTAGCGGAATGGAAATAGACG | ATGCGGCCGCGTAAGGACAGACACCACCTGAC |

Gene deletion.

cspA deletion by the selectable marker phleomycin (phl) was performed as follows: a 5,215-bp DNA fragment flanking the A. fumigatus cspA gene was generated by PCR with the PfuUltraII fusion HS DNA polymerase (Stratagene, San Diego, CA) and primers AscI-cspA 5′ and AscI-cspA 3′. These primers were designed to contain an AscI restriction site at their 5′ end. The cspA gene, including 354 bp upstream and 399 bp downstream of the open reading frame (ORF), was then removed by digestion with Acc65I and AflII and replaced with a phleomycin-selectable marker to produce plasmid pΔcspA-phl. The phleomycin cassette, containing 5′ and 3′ Acc65I and AflII restriction sites, respectively, was generated by PCR amplification using primers Acc65I-phl 5′ and AflII-phl 3′. cspA deletion with the pΔcspA-hgh plasmid containing the hph cassette was performed as described previously (27). For ECM33 deletion, we generated an ∼4-kb fragment with PfuUltraII fusion HS polymerase (Stratagene) and primers AscI-ECM33 5′ and AscI-ECM33 3′. The ECM33-deleted strain was constructed with the phleomycin resistance gene phl as a selectable marker. The phl cassette was amplified by PCR with primers Acc65-phl 5′ and Acc65-phl 3′ and placed 211 bp downstream of the ECM33 ATG start codon and 180 bp upstream of the stop codon.

For transformation, 10 μg of spin-purified AscI-digested pΔcspA-hgh or pΔcspA-phl plasmid was used. Transformation was performed as described previously (37).

cspA overexpression.

We generated a 5,215-bp DNA fragment containing A. fumigatus cspA with its endogenous promoter and terminator by PCR, using PfuUltraII fusion HS DNA polymerase and primers NotI-cspA 5′ and NotI-cspA 3′. This fragment was cloned into NotI-digested pAMA-1, a self-replicating high-copy-number plasmid containing pyr4 as a selectable marker (35), to generate pAMA-1-cspA. pAMA-1-cspA was transformed into the uracil-auxotrophic strain AF 293.1, generating the cspA-ovx strain (cspA overexpresser strain).

Growth rate and conidial germination analysis.

Freshly harvested conidia were plated at a concentration of 103 to 105/ml onto 96-well plates in 200 μl liquid minimal medium (MM; 70 mM NaNO3, 1% [wt/vol] glucose, 12 mM KPO4 [pH 6.8], 4 mM MgSO4, 7 mM KCl, and trace elements) at 37°C. At various time points, growth was observed under a grid-mounted Olympus CK inverted microscope at a 200× magnification. The length of the germlings (n = 50) was measured in micrometers.

Conidial disruption by glass beads.

A. fumigatus conidia (5 × 107/ml) in 0.5 ml DDW plus 0.1% Tween 80 were mixed with 0.5 ml (packed volume) of acid-washed glass beads, 150 to 212 μm in diameter (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO). They were then vortexed at medium strength for up to 10 min. At each time point, a sample was taken, diluted to ∼5 × 103 conidia/ml, and plated (100 μl) on YAG plates in triplicate. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 to 36 h, colonies were counted, and survival rates were calculated with the following formula: [(number of colonies at time X)/(number of colonies at time zero)]·100.

Resistance of germinating conidia to protoplasting.

Freshly harvested conidia (5 × 108) were inoculated in 25 ml liquid YAG and incubated for 6 h at 32°C with shaking at 200 rpm. Germinating conidia were collected and incubated with shaking for between 30 and 120 min at 30°C in 20 ml protoplasting mix (1% [wt/vol] Driselase and 0.5% [wt/vol] lysing enzymes [Sigma-Aldrich], 10 mM MgSO4, 1% [wt/vol] bovine serum albumin [BSA]). At each time point, 1 ml protoplasts was collected, suspended in YAG containing 1 M sorbitol, counted, and diluted to 5 × 103 protoplasts/ml. A 0.1-ml aliquot of protoplasts was immediately plated on YAG or YAG-sorbitol (1 M) plates in triplicate, incubated at 37°C for 16 to 32 h, and counted. Colonies counted on YAG-sorbitol plates represented all cells that had undergone treatment (intact osmotically stable cells and osmotically sensitive protoplasts). Colonies counted on YAG plates represented only osmotically insensitive cells (i.e., cells with relatively undamaged cell walls). Survival rates were calculated with the following formula: [(number of colonies on YAG plates)/(number of colonies on YAG-sorbitol plates)]·100.

Adhesion assay.

Adhesion of A. fumigatus conidia to ECM derived from A549 human alveolar epithelial cells was tested in 96-well plates. ECM-coated plates were prepared as described by Wasylnka and Moore (48). Conidia at a concentration of 108/ml were added to the plates for 1 h at 37°C. The plates were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.05% Tween 80. Adherent conidia were counted under a grid-mounted Olympus CK inverted microscope at a ×200 magnification. Statistical analysis was performed by Student's two-tailed t test.

Electron microscopy.

For transmission electron microscopy (TEM), freshly harvested conidia were fixed in 2.5% (wt/vol) glutaraldehyde (Merck Inc., Whitehouse Station, NJ) in PBS. They were then washed, postfixed in 1% OsO4 in PBS, and washed again. After dehydration in graded ethanol solutions, the cells were embedded in glycidyl ether 100 (Serva Electrophoresis Gmbh, Heidelberg, Germany). Ultrathin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined with a Jeol 1200 EX TEM. For scanning electron microscopy (SEM), freshly harvested dormant conidia were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS, dehydrated in ethanol, CO2 critical-point dried, gold coated, and examined in a JEOL JSM 840A SEM.

Flow cytometry analysis of lectin- and antibody-labeled conidia.

Freshly harvested conidia (107/ml) were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled lectins (10 μg/ml) according to the manufacturer's protocol (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The lectins tested were Ulex europaeus agglutinin I (UEAI), Glycine max agglutinin (SBA), Dolichos biflorus agglutinin (DBA), Arachis hypogaea agglutinin (PNA), Ricinus communis agglutinin (RCA), wheat germ agglutinin (WGA), concanavalin A (ConA), and Sambucus nigra lectin (EBL).

For β(1-3)-glucan staining, 5 × 106 conidia/ml were incubated for 1 h with 20 μg/ml monoclonal antibody (MAb) 744 (19), followed by a goat anti-mouse IgM-Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate (Invitrogen Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA) diluted 1:400 in PBS with 1% BSA. The cells were washed in PBS containing 1% BSA and suspended in PBS. Cell surface fluorescence was quantified with a FACSort flow cytometer (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ). The results were summarized in fluorescence frequency distribution histograms (number of fungal cells versus relative fluorescence intensity expressed as arbitrary units on a logarithmic scale). The presented data correspond to mean values of the cell surface fluorescence calculated, in all experiments, from the analysis of about 10,000 cells per sample. The geometric mean of the fluorescence of each sample was calculated using FlowJo software (Ashland, OR).

CspA protein analysis.

To analyze the expression of cspA-encoded protein during germination and growth, À. fumigatus conidia with cspA-encoded myc-tagged protein (the cspA-myc strain) (27) were allowed to germinate in YAG liquid medium for the times indicated in Fig. 1. For cspA-myc conidial immunostaining, coverslips were incubated in fixation solution (37% formaldehyde, 50 mM HEPES [pH 6.7], 5 mM MgSO4, 25 mM EGTA [pH 7.0]) for 45 min and washed in phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% bovine serum albumin (PBS-BSA) for 5 min.

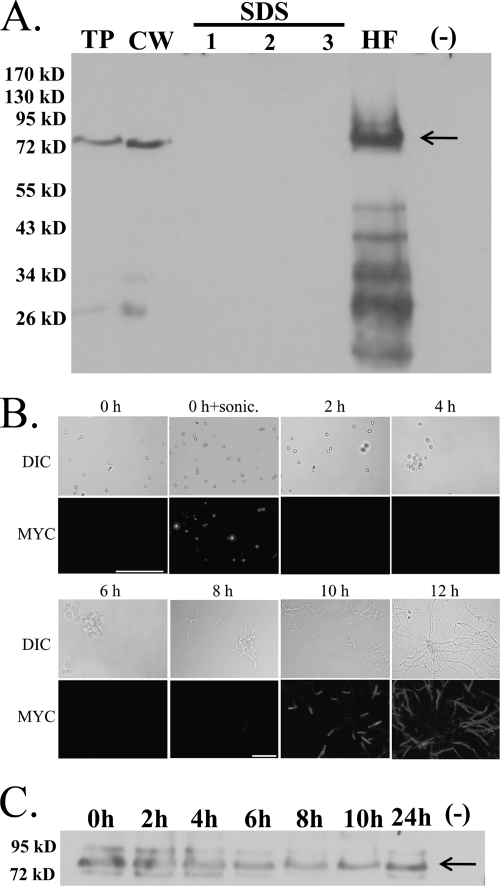

Fig. 1.

Analysis of the protein encoded by cspA. (A) cspA-encoded protein is removed by HF treatment, suggesting that it is GPI anchored to the cell wall. Total protein (TP) and cell wall (CW) were extracted from the A. fumigatus myc-tagged cspA strain after 24 h of growth. CW was isolated and extracted three times with SDS/β-mercaptoethanol buffer (SDS lanes 1 to 3) and HF pyridine (lane HF). Total protein extracted from the untagged parental strain (AF 293) grown for 24 h was used as a negative control (−). myc-tagged cspA-encoded protein was detected with a specific mouse-derived anti-c-myc monoclonal antibody. Molecular mass markers (kDa) are indicated on the left side of the blot. (B) cspA-encoded protein is localized to the hyphal tip cell wall in germinating A. fumigatus conidia. Immunofluorescence analysis of cspA protein localization was performed with freshly harvested, nongerminated (0 h) conidia, sonicated conidia (0 h + sonic), and germlings (2 to 12 h) expressing cspA-myc. No immunofluorescence was detectable in nontransformed control WT cells (data not shown). Top panels (DIC), Cells viewed by differential interfering contrast microscopy; bottom panels (MYC), cspA-myc-tagged fluorescent images. Bars, 20 μm. (C) cspA protein is found in the cell wall of dormant and growing A. fumigatus conidia. Cell wall was extracted from nongerminated (0 h) conidia and germlings (2 to 12 h) expressing cspA-myc protein and analyzed by Western blotting.

Mouse-derived primary antibody c-myc (9E10) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) was diluted 1:100 in PBS-BSA and added to the coverslips for 1 h. Coverslips were washed twice with PBS containing 0.1% (wt/vol) Nonidet P-40 for 5 min. Alexa Fluor 488 anti-mouse secondary antibodies were used according to the manufacturer's instructions (signal amplification kit for mouse antibodies; Invitrogen). Images were obtained by fluorescence microscopy on an Olympus BX40 microscope equipped for fluorescence at a total magnification of ×400.

The hydrophobin layer was dislodged as described by Paris et al. (36). Briefly, freshly harvested cspA-myc conidia were sonicated at 140 W for 20 min in a Vibra-cell VC500 sonicator (Sonics and Materials Inc., Danbury, CT) prior to immunostaining. Images were recorded with a digital Olympus DP70 camera. For Western analysis, fungal biomass was collected onto Miracloth (Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany), washed once in distilled water, and dried. Nongerminated, freshly harvested conidia were used for the 0-h time point. Fungal biomass was then frozen in liquid nitrogen and lyophilized overnight. The lyophilized pellets were weighed out to 10 mg (dry weight) per extraction reaction, and an equal volume of glass beads was added and ground with a sterile 1-ml tip in a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube for 2 min. To remove cytosolic contaminants, membrane proteins, and disulfide-linked cell wall proteins, the pellets were boiled three times in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) extraction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.8], 2% [wt/vol] SDS, 50 mM EDTA, and 40 mM β-mercaptoethanol). The cell walls were pelleted after extraction as described above, and the supernatants were dialyzed and freeze-dried. Cell walls were then washed six times with water, lyophilized, and weighed. Freeze-dried cell walls were incubated with 10 μl/mg (dry weight) HF-pyridine (Sigma) for 3 h at 0°C (8). After centrifugation, the supernatant containing the HF-extracted proteins was collected in 100-μl aliquots and proteins were precipitated by the addition of 9 volumes of 100% methanol buffer (100% [vol/vol] methanol, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.8) and subsequently incubated at 0°C for 2 h. Precipitated proteins were collected by centrifugation (15,000 × g, 10 min, at 4°C). The pellet was washed three times with 90% methanol buffer (90% methanol, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.8) and lyophilized. Protein was resuspended in urea sample-buffer prior to SDS-PAGE analysis as described previously (18).

Western blot analysis.

Western blot analysis was performed as described previously (18). cspA-encoded myc-tagged protein was detected following incubation of the blot with mouse-derived anti-c-myc monoclonal antibody (9E10) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., CA) for 1 h followed by two washes in TBST (2.5 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 15 mM NaCl, 0.005% Tween 20) for 15 min each. The tagged protein was visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch) at a 1:20,000 dilution.

Macrophage conidial uptake assay.

Conidial internalization by human monocyte-derived macrophages (HuMoDMs) was performed by the previously described biotin-calcofluor white staining method (28). Briefly, resting conidia were biotinylated with 10 mg/ml sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin (Molecular Probes, Karlsruhe, Germany) in 50 mM NaHCO3, pH 8.5, for 2 h at 4°C. The remaining reactive biotin molecules were inactivated by incubation in 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, for 40 min at 4°C.

For phagocytosis experiments, HuMoDMs were seeded on glass coverslips in 24-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 monocytes/well. After 10 days of differentiation, the macrophages were infected with biotinylated and calcofluor white-stained conidia at a 10:1 ratio of conidia to HuMoDMs for 2 h of incubation at 37°C. After three washes with PBS, extracellular conidia were labeled with Cy3-labeled streptavidin (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany) (diluted 1:100 in PBS, 30 min at 37°C). Following two washing steps with PBS, coverslips were observed under a fluorescence microscope. At least 100 macrophages were analyzed per slide, and the internalized conidia were counted. The phagocytosis index was calculated as the ratio of the total number of internalized conidia to the total number of HuMoDMs. Student's t test was used to determine the statistical significance of the observed inhibitory effects. Significance was defined at a P value of <0.05.

Macrophage conidial kill assay.

Conidia (5 × 104) were added to HuMoDMs in 24-well microtest plates at a 1:1 ratio for 2 h of preincubation at 37°C. Then, uningested conidia were aspirated and 0.5 ml PBS was added. The washing step was repeated twice, and finally 0.5 ml RPMI medium was added for 2 h of incubation at 37°C. Conidial killing was terminated by aspiration of the RPMI medium and addition of DDW with 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 to lyse the macrophages. Following vigorous scraping of the wells, lysate dilutions were plated on YAG agar plates for 16 h to detect viable fungal colonies. Viable counts were compared to those of conidia incubated with macrophages at the 0-h time point (after the 2-h preincubation).

PMNL hyphal damage assay.

The polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMNL) hyphal damage assay was performed as described previously (47). Briefly, conidia were allowed to germinate for 8 h at a concentration between 1 × 103 and 5 × 103/well in 96-well plates and then centrifuged at 400 × g for 10 min, the supernatants were aspirated, and 0.2 ml of PMNLs at 2.5 × 105 to 2 × 106 per ml in RPMI medium was added to the wells. Following incubation at 37°C for 14 h in a CO2 incubator, the plates were centrifuged, supernatants were aspirated, and 0.2 ml/well of distilled water was added. The centrifugation and washing step was repeated. Finally, 0.2 ml of XTT tetrazolium salt test solution (Biological Industries, Beit-Haemek, Israel) was added per well, cultures were incubated at 37°C until the solution turned orange, and the absorbance at 450 nm was recorded. Optical density (OD) values in the wells containing conidia alone (A) ranged from 0.2 to 0.8 and were compared to the coculture well's OD values (B). The cytotoxicity was calculated by the formula [(A − B)/A]·100.

Murine model for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis.

Six-week-old female ICR mice (Harlan Biotech, Rehovot, Israel) were injected intraperitoneally with cyclophosphamide (150 mg/kg in PBS) at 3 days before and at 2 days after conidial infection. Cortisone acetate (150 mg/kg PBS with 0.1% Tween 80) was injected subcutaneously at 3 days before conidial infection. Infection was performed by intranasal conidial administration. Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of a solution of 250 μl xylazine (VMD, Arendonk, Belgium) and ketamine (Imalgene, Fort Dodge, IA) at concentrations of 1.0 mg/ml and 10 mg/ml, respectively (dissolved in PBS). Following anesthesia, the mice were inoculated intranasally with 2.5 × 105 freshly harvested conidia of the AF 293, ΔcspA, ΔECM33, and ΔcspA ΔECM33 strains in PBS plus 0.1% Tween 80. The inoculum was verified by quantitative culture. An additional control group was mock infected with PBS plus 0.1% Tween 80 alone. Mice in this group remained alive throughout the duration of the experiment. The animals were monitored for survival for 28 days postinfection. Statistical analysis of mouse survival was performed with GraphPadPrism 4 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

cspA encodes a GPI-anchored CWP that is unmasked during conidial germination.

The cspA-encoded protein contains both an N-terminal leader sequence and a putative C-terminal GPI anchor motif. GPI-anchored CWPs can be extracted from the cell wall by treatment with hydrofluoric acid (HF), which cleaves the phosphodiester bond in the remnant of the GPI anchor. Extensively SDS–β-mercaptoethanol-extracted cell walls of A. fumigatus expressing myc-tagged cell surface protein (CSP) were incubated with HF-pyridine for 3 h on ice. HF-extracted CSP was detected by Western analysis with myc epitope-specific antibodies (Fig. 1A, lane HF). cspA-encoded protein was not extracted by repeated washes in SDS–β-mercaptoethanol (Fig. 1A, lanes 1 to 3). These results strongly suggest that the protein encoded by cspA is covalently attached to cell wall β-glucan via its GPI anchor. Notably, although the amino acid sequence of the cspA-encoded protein predicts a molecular mass of 45 kDa, its experimental size was approximately 75 kDa, suggesting that the protein is heavily glycosylated.

We analyzed the expression of myc-tagged cspA-encoded protein on the surface of germinating conidia by antibody labeling and fluorescence microscopy. This protein was found to be primarily expressed on the hyphal surface of germinating conidia (Fig. 1B, 6 to 12 h postgermination), surface expression increasing with hyphal growth and elongation. Interestingly, Western analysis of cell wall extracts indicated that this protein is abundant in dormant and swelling conidia (Fig. 1C), even though at that time it is not labeled on the cell wall surface (Fig. 1B). This suggested that in dormant conidia and during early germination, cspA-encoded protein is found below the cell wall surface, possibly masked by the outer layer of hydrophobins that coats the cell wall during these early stages of growth. To test this hypothesis, cspA-myc conidia were sonicated to dislodge the outer hypdrophobin layer as previously described (36). myc immunostaining of cspA-encoded protein following sonication revealed extensive binding of the antibody to the conidial surface (Fig. 1B, 0 h+sonic), validating our hypothesis.

Overexpression of cspA inhibits conidial germination and increases conidial resistance to protoplasting.

We previously showed that deletion of cspA accelerates the rate of conidial germination (27). We therefore reasoned that cspA overexpression might reduce this rate. To test this hypothesis, we transformed the uracil-auxotrophic strain AF 293.1 with the AMA-1-cspA high-copy-number plasmid containing cspA under its endogenous promoter, to generate the cspA-ovx (overexpresser) strain. Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analysis indicated that cspA mRNA levels increased 7-fold in the cspA-ovx strain compared to those of AF 293.1 transformed with the AMA-1 control plasmid (data not shown). Strikingly, the cspA-ovx strain showed a marked reduction in radial growth rates compared to the AF 293.1 wild-type strain (WT) or AF 293.1 wild type transformed with the AMA-1 control plasmid (AMA) or following FOA (5 fluoroorotic acid)-induced eviction of the AMA-1-cspA plasmid (cspA-ovx-ev) (Fig. 2A). As predicted, whereas cspA deletion induced early and rapid conidial germination and hyphal growth, cspA overexpression had the opposite effect (Fig. 2B and C). A simple explanation for these results is that elimination of cspA-encoded protein leads to the formation of a softer, more pliable cell wall, enabling germination to proceed more rapidly, whereas cspA overexpression hardens the cell wall, leading to delayed germination and hyphal growth. To test this idea, we compared the resistance levels of wild-type (AF 293), cspA-deleted (ΔcspA), and cspA-ovx conidia to cell wall-degrading enzymes (Fig. 3A) or physical disruption by glass beads (Fig. 3B) (see Materials and Methods for experimental details). ΔcspA conidia were hypersensitive to both enzymatic and physical insult, suggesting that their cell wall is substantially weaker than that of the WT strain. cspA overexpression resulted in enhanced conidial resistance to cell wall-degrading enzymes but reduced resistance to physical disruption by glass beads, relative to that of the WT strain. This suggests that while the overall structure of the cell wall is physically weakened in the cspA-ovx strain, the inner glucan- and chitin-rich cell wall layer may be less accessible to the degrading enzymes. Microscopic analysis revealed that cspA deletion or overexpression results in enhanced roughness and folding of the conidial cell wall, possibly increasing its physical fragility (Fig. 3C, SEM panels).

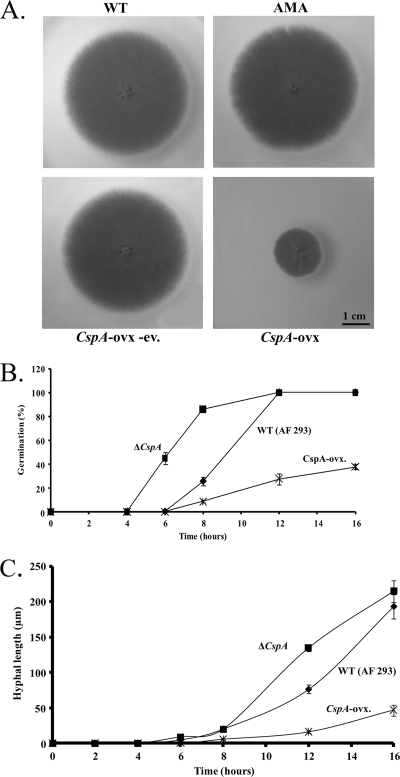

Fig. 2.

cspA overexpression results in slow growth and reduced rates of germination and hyphal elongation. (A) WT (AF 293.1), AMA (AF 293.1 transformed with the AMA-1 control plasmid), cspA-ovx (overexpression strain), and cspA ovx-ev (the cspA-ovx strain following FOA-induced eviction of the AMA-1-CSP plasmid) strains were grown for 72 h on YAG agar. (B) Germination rates of the WT, cspA-deleted (ΔcspA), and cspA-ovx A. fumigatus strains. (C) Quantitative analysis of hyphal growth of WT, ΔcspA, and cspA-ovx A. fumigatus strains. The results for each time point are calculated as the mean ± standard error (error bar) for 50 hyphae (see Materials and Methods for details). The experiments shown in panels B and C were repeated three times with similar results.

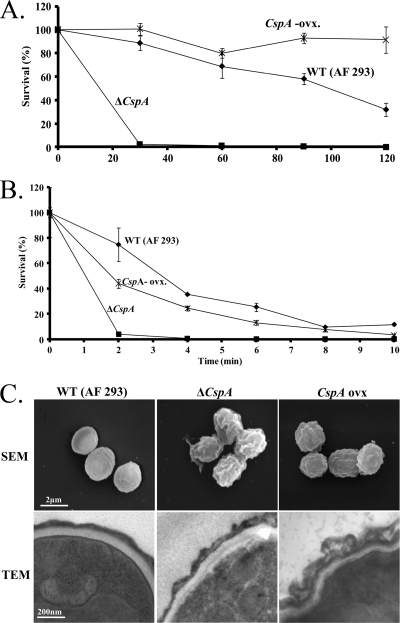

Fig. 3.

cspA overexpression enhances conidial resistance to enzymatic cell wall removal and affects the morphology of the cell wall. Wild-type (WT), cspA-deleted (ΔcspA), and cspA-overexpressing (cspA-ovx) A. fumigatus strains were incubated in the presence of cell wall-degrading enzymes (A) or physically disrupted by agitation in the presence of glass beads (B) for various times. The ΔcspA strain exhibited enhanced sensitivity to cell wall-degrading enzymes and to physical disruption by glass beads, whereas the cspA-ovx strain was more resistant to the former. The experiments shown in panels A and B were repeated three times in triplicate with similar results. A representative experiment is shown. (C) Scanning electron microscopy (top) and transmission electron microscopy (bottom) of WT, ΔcspA, and cspA-ovx conidia show that cspA deletion and overexpression affect cell wall morphology and structure.

In contrast, SEM and TEM analysis of WT, ΔcspA, and cspA-ovx 8-h germinating conidia showed no difference in cell wall morphology (data not shown), suggesting that the mutant cspA phenotypes are visible only in dormant conidia.

cspA functionally interacts with ECM33 and GEL2.

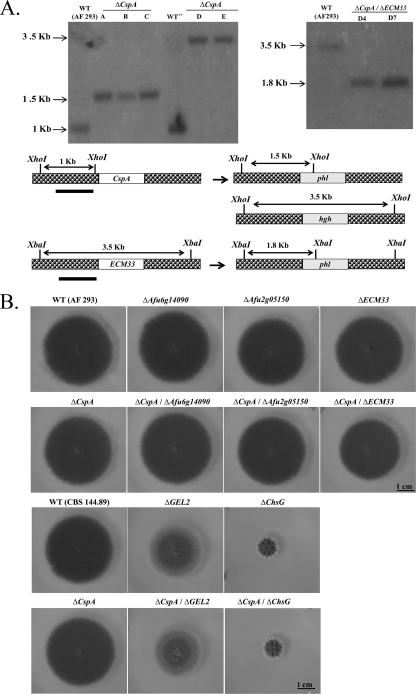

Functional interactions between cspA and genes that encode cell wall-associated proteins were analyzed by generating double-gene knockout strains and comparing their phenotypes. The following genes were selected for deletion in combination with cspA: Afu6g14090 and Afu2g05150 encoding repeat-rich wall proteins (27), ECM33 (5, 37), GEL2 encoding glucanosyltransferase (33), and chsG encoding chitin synthase (32). To generate the ΔcspA ΔAfu6g14090, ΔcspA ΔAfu2g05150, and ΔcspA ΔECM33 strains, ΔAfu6g14090, ΔAfu2g05150, and ΔECM33 single mutant strains (AF 293 background) were transformed with pΔcspA-phl. To generate the CBS 144.89 background ΔcspA, ΔcspA ΔGEL2, and ΔcspA ΔchsG strains, ΔGEL2 and ΔchsG single mutant strains (CBS 144.89 background) were transformed with pΔcspA-hgh. Southern analysis confirmed that double gene deletion had occurred (Fig. 4A and see Materials and Methods for a detailed description). Analysis of the gross hyphal morphology of the double mutants point inoculated on YAG agar plates (Fig. 4B) or grown in the presence of itraconazole, terbinafine, amphotericin B, caspofungin, SDS, Congo red, calcofluor white, H2O2, or menadione (data not shown) indicated no synthetic lethality or additivity compared to the single mutant strains. We therefore concentrated on analyzing conidial germination, morphology, and stability in the various strains, because those were the characteristics with the most notable phenotypic outcome after cspA deletion.

Fig. 4.

Generation of cspA double mutants in A. fumigatus. (A) Left, Southern blot analysis (top) and restriction map (bottom) of A. fumigatus strains after deletion of cspA by the hph (lanes A, B, and C) and phl (lanes D and E) selectable markers. Results are shown for A. fumigatus control AF 293 and CBS 144.89 wild-type strains and CBS 144.89 ΔcspA (lane A), ΔAfu6g14090 (lane B), ΔAfu2g05150 (lane C), ΔGEL2 (lane D), and ΔchsG (lane E) mutant strains. Genomic DNA was digested with XhoI and hybridized with 32P-labeled ΔcspA 5′ DNA probe (restriction map, filled black line), resulting in 1-kb fragments for the WT and 3.5-kb and 1.5-kb fragments for the ΔcspA hph-deleted and phl-deleted strains, respectively (see restriction map). Right, deletion of ECM33 by the phl cassette. Southern blot verification of the A. fumigatus control AF 293 WT strain (lane WT) and ECM33-deleted isolates (lanes D4 and D7) is shown. Genomic DNA was digested with XbaI and hybridized with 32P-labeled ECM33-5′ DNA probe, resulting in a 3.5-kb fragment for the WT and a 1.8-kb fragment for the ΔcspA phl-deleted strains, respectively (see restriction map). (B) WT and single and double mutant strains were spot inoculated on YAG agar and grown for 72 h. No differences in radial growth were detected between the WT (AF 293), the single-gene deletion mutants (ΔAfu6g14090, ΔAfu2g05150, ΔECM33, ΔcspA), and the double-gene deletion mutants (ΔcspA ΔAfu6g14090, ΔcspA ΔAfu2g05150, ΔcspA ΔECM33). Radial growth was reduced in the ΔGEL2 and ΔchsG mutant strains but was not further reduced by the additional deletion of cspA (ΔcspA ΔECM33 and ΔcspA ΔGEL2).

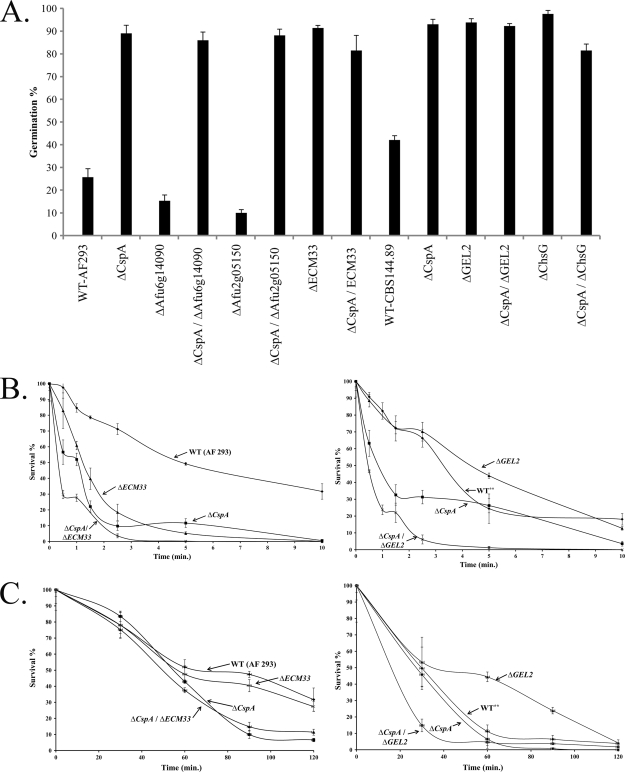

Deletion of cspA or ECM33 results in more rapid conidial germination (27, 37). Consequently, we compared the germination rates of WT, the ΔcspA strain, and the various single and double mutants. We found that deletion of ECM33, GEL2, or chsG alone results in increased rates of conidial germination compared to that of the WT strain and that these rates are not increased by also deleting cspA (Fig. 5A). In contrast, deletion of Afu6g14090 or Afu2g05150 slightly decreased germination rates compared to that of the WT strain (P < 0.05). Interestingly, deletion of cspA in these two strains was dominant, leading to high ΔcspA strain-like rates of germination (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Germination and resistance of WT and cspA single- and double-deletion mutant strains to cell wall disruption. (A) Percentage of germinated cells of WT and cspA single- and double-deletion mutant strains after 8 h of growth in MM at 37°C. Shown are the means + standard deviations (error bars) for three independent experiments. (B) Resistance of the various strains to physical disruption by glass beads. ΔcspA ΔECM33 and ΔcspA ΔGEL2 strains are more susceptible to glass bead disruption than the respective single-gene deletion mutants and AF 293 (WT) and CBS 144.89 (WT**) strains. (C) Resistance of the various strains to cell wall-degrading enzymes. The ΔcspA ΔGEL2 strain is more sensitive to cell wall-degrading enzymes than the single-gene deletion mutant and WT strain (right), whereas the ΔcspA ΔECM33 strain is not (left). The experiments in panels B and C were repeated three times with similar results. A representative experiment is shown.

We next compared the levels of resistance of the various strains to physical disruption by glass beads (Fig. 5B) and to cell wall-degrading enzymes (Fig. 5C). Conidia from strains carrying double mutations of cspA and Afu6g14090, Afu2g05150, or chsG were not more susceptible to glass bead disruption than the respective single-gene deletion mutants (data not shown), whereas the ΔcspA ΔGEL2 and ΔcspA ΔECM33 double mutants exhibited enhanced susceptibility (Fig. 5B). The former strain was also more sensitive to cell wall-degrading enzymes than the respective single-gene deletion mutants, whereas the latter was not more susceptible than the ΔcspA single mutant strain (Fig. 5C).

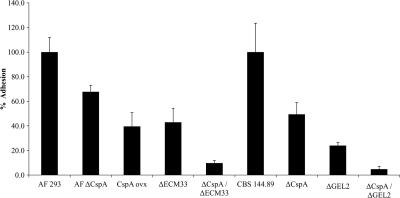

ΔcspA ΔECM33 and ΔcspA ΔGEL2 conidia adhere poorly to ECM.

To determine whether the deletion of cspA, together with that of ECM33 or GEL2, additively affects conidial adhesion, we performed conidial binding assays on culture-derived ECM. We have previously shown that deletion of cspA results in decreased adhesion to this substrate (27). We compared the relative levels of conidial binding of the ΔcspA, cspA-ovx, ΔGEL2, and ΔECM33 single mutants, the ΔcspA ΔGEL2 and ΔcspA ΔECM33 double mutants, and the isogenic WT strains (see Materials and Methods).

Conidial binding of each of the ΔcspA, ΔGEL2, and ΔECM33 single mutant strains was significantly reduced (P < 0.005) in comparison to their parental WT strain, as was the adhesion of the cspA-ovx mutant strain (Fig. 6). Strains containing double gene deletions (ΔcspA ΔGEL2 and ΔcspA ΔECM33 mutants) showed a further additive reduction (P < 0.0005) in conidial adhesion relative to each of their parental single mutant strains. Taken together, these results suggest that the conidial wall of the double-deletion mutant strains may have undergone severe structural changes that reduced their ability to adhere to ECM. We therefore performed a detailed microscopic structural analysis of the conidial wall structure in the strains we had generated.

Fig. 6.

The cspA single- and double-deletion mutant strains show reduced conidial adhesion to extracellular matrix (ECM). The levels of adhesion of the ΔcspA, cspA-ovx, ΔECM33, ΔGEL2, ΔcspA ΔECM33, and ΔcspA ΔGEL2 strains to ECM were compared to that of the WT AF 293 and CBS 144.89 strains. Shown are the means + standard deviations (error bars) for three independent experiments. Each mutant strain exhibited significantly reduced adhesion relative to its parental WT strain (P < 0.005). The adhesion of each of the double mutant strains was significantly reduced in comparison to their parental single mutant strains (P < 0.0005).

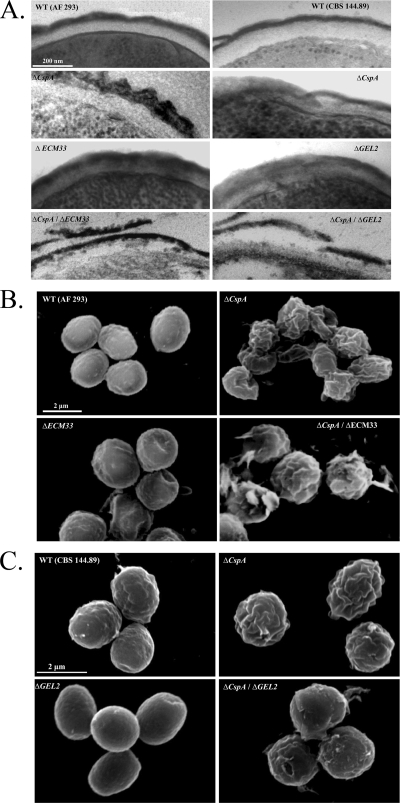

The conidial cell wall of the ΔcspA ΔGEL2 and ΔcspA ΔECM33 mutant strains exhibits striking morphological abnormalities.

TEM analysis (Fig. 7A) of the conidial cell walls of the ΔcspA ΔGEL2 and ΔcspA ΔECM33 double mutants, the ΔcspA, ΔGEL2, ΔECM33 single mutants, and their isogenic WT strains revealed that single gene deletion results in disruption of the layering of the conidial cell wall, which is characterized by a melanin-rich electron-dense outer layer and a carbohydrate-rich clear inner layer. Double gene deletion resulted in increased conidial cell wall fragility, characterized by peeling and shedding of the outer layer (Fig. 7A, lower panels). SEM analysis further confirmed these results: ΔcspA ΔECM33 and ΔcspA ΔGEL2 conidia were characterized by extensive fracturing and peeling of the outer cell wall layer (Fig. 7B and C, respectively). It is, however, important to note that the peeling observed, although indicative of cell wall damage, could be a result of sample fixation and dehydration prior to microscopy.

Fig. 7.

cspA functionally interacts with ECM33 and GEL2. Results of transmission electron microscopy (A) and scanning electron microscopy of WT (AF 293 [B] and CBS 144.89 [C]), ΔcspA, ΔECM33, ΔGEL2, ΔcspA ΔECM33, and ΔcspA ΔGEL2 strains are shown. ΔcspA ΔECM33 and ΔcspA ΔGEL2 double mutants show an additive phenotype characterized by severe damage to the conidial cell wall morphology and structure.

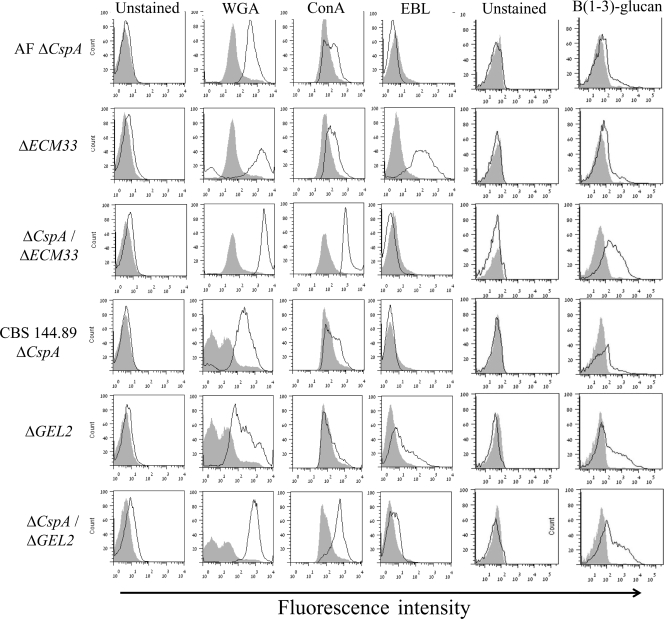

The outer conidial cell walls of the ΔcspA ΔGEL2 and ΔcspA ΔECM33 mutant strains contain high levels of exposed chitin, mannose, and glucan.

We hypothesized that the enhanced morphological differences seen in the cell walls of the ΔcspA ΔGEL2 and ΔcspA ΔECM33 double mutants change the carbohydrate composition of their conidial surface. To test this, we labeled dormant conidia from the WT and single and double mutants with FITC-labeled lectins (see Materials and Methods) or specific anti-β-glucan antibodies and analyzed them by flow cytometry. Conidia were labeled only with the FITC-labeled lectins WGA, ConA, and EBL, which specifically label N-acetylglucosamine (a component of chitin), α-mannose, and sialic acid residues, respectively, and with the β-glucan-specific antibodies. WGA, ConA, and β-glucan labeling was strongly enhanced in the ΔcspA ΔECM33 and ΔcspA ΔGEL2 double mutants relative to that of the single mutant and isogenic WT strains (Fig. 8 and Table 3). These results suggested that the surface of the double mutant conidia contains very high levels of exposed chitin, mannan, and glucan, possibly because of the substantial defects in the organization of their cell walls. Interestingly, ΔcspA and ΔECM33 conidia displayed heterogenous labeling intensities with ConA or WGA, respectively, indicating that there is some variability in the extent of polysaccharide surface exposure of individual mutant conidia. Labeling with EBL, which recognizes sialic acid residues, was enhanced only in the ΔECM33 mutant and, surprisingly, returned to low levels in the ΔcspA ΔECM33 double mutant. FITC-lectin labeling of the cspA-ovx strain did not show appreciable surface differences compared to the surface of the WT strain (data not shown).

Fig. 8.

The outer conidial cell walls of the ΔcspA ΔGEL2 and ΔcspA ΔECM33 mutant strains contain high levels of exposed chitin, mannose, and glucan. Conidia were stained with fluorescent lectins WGA, ConA, and EBL and anti-β-glucan-specific antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. The results are summarized in fluorescence frequency distribution histograms: the gray-filled histogram represents the relative signal of the corresponding WT conidia, whereas the unfilled black histogram represents the relative signal of mutant conidia (number of fungal cells versus relative fluorescence intensity expressed as arbitrary units on a logarithmic scale). A total of 10,000 cells were examined per sample in all experiments.

Table 3.

Geometric mean fluorescence intensity in conidia analyzed by flow cytometry

| Strain or genotype | Geometric mean fluorescence intensity in conidiaa |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstained | WGA | ConA | EBL | β(1-3)-glucan | |

| AF 293 (WT) | 3.91 | 48.63 | 71.75 | 5.37 | 13.95 |

| AF 293 ΔcspA | 4.38 | 369.88 | 134.6 | 3.27 | 23.34 |

| ΔECM33 | 5.43 | 229 | 163.25 | 111.47 | 29.99 |

| ΔcspA ΔECM33 | 5.27 | 2,285.14 | 1,219.4 | 3.16 | 51.78 |

| CBS 144.89 (WT) | 4.05 | 10.18 | 105.12 | 3.98 | 13.29 |

| ΔcspA | 4.73 | 146.29 | 182.61 | 3.06 | 12.31 |

| ΔGEL2 | 5.69 | 181.96 | 135.18 | 13.75 | 53.34 |

| ΔcspA ΔGEL2 | 7.47 | 684.32 | 437.55 | 5.14 | 66.8 |

Conidia were left unstained or were stained with WGA (chitin), ConA (α-mannose), EBL (sialic acid), or β(1-3)-glucan-specific antibody.

Increased internalization and killing of the ΔcspA, ΔECM33, and ΔcspA ΔECM33 mutant strains by HuMoDMs and increased hyphal damage by PMNLs.

We reasoned that the increased disorganization of the cell wall and exposure of surface β-glucan in the double mutant strains may increase their recognition and uptake by macrophages and make them more susceptible to killing. We selected the ΔcspA, ΔECM33, and ΔcspA ΔECM33 mutant strains for this analysis. Results indicated that (i) ΔcspA, ΔECM33, and ΔcspA ΔECM33 conidia were endocytosed more rapidly and in larger numbers by HuMoDMs throughout the 2 h of the experiment. The double mutant was endocytosed at the highest initial rate (Fig. 9A, see 40-min time point) (24). (ii) ΔcspA, ΔECM33, and ΔcspA ΔECM33 conidia were each more sensitive to HuMoDM killing (P < 0.05) than the WT (AF 293) strain (Fig. 9B), although the double mutant was not more susceptible than the single mutants. (iii) Hyphae of the ΔcspA ΔECM33 strain were more sensitive to hyphal damage induced by PMNLs than the WT strain (P < 0.01), whereas the ΔcspA and ΔECM33 single mutant strains were each not more sensitive than the WT strain (Fig. 9C). Together, these results suggest that increased surface expression of β-glucans in the ΔcspA and ΔECM33 single mutants and in the ΔcspA ΔECM33 double mutant may result in progressively faster conidial uptake in HuMoDM cells and enhanced killing.

Fig. 9.

Increased uptake and killing of the ΔcspA, ΔECM33, and ΔcspA ΔECM33 mutant strains by human monocyte-derived macrophages (HuMoDMs) and enhanced hyphal damage by neutrophils (PMNLs). (A) Conidial endocytosis by HuMoDMs over time; (B) conidial killing by HuMoDMs after 2 h of coincubation; (C) hyphal damage by human neutrophils after 14 h of coincubation. Shown are the means + standard deviations (error bars) for three independent experiments. **, P value of <0.05 for each mutant strain relative to the WT (AF 293) strain.

The ΔcspA, ΔECM33, and ΔcspA ΔECM33 mutant strains are not altered in virulence in infected mice.

We hypothesized that the increased internalization and killing of the ΔcspA, ΔECM33, and ΔcspA ΔECM33 mutant strains by HuMoDMs would result in reduced virulence in infected mice. To test this hypothesis, the virulence of these strains was tested in a mouse model of invasive aspergillosis. Mice were immunosuppressed with a combination of cyclophosphamide and cortisone acetate to induce neutropenia. Freshly harvested conidia from the WT (AF 293) and ΔcspA, ΔECM33, and ΔcspA ΔECM33 mutant strains were carefully counted and adjusted to the same density before intranasal administration. The number of live mice in each group was recorded daily throughout the 28-day study period. Figure 10 shows survival curves obtained during the course of the experiment. Although there was a slight increase in virulence of the ΔcspA and ΔcspA ΔECM33 mutant strains compared to that of the WT strain, these differences were not statistically significant (P > 0.2).

Fig. 10.

Deletion of cspA, ECM33, or both cspA and ECM33 does not affect virulence in a neutropenic murine model of pulmonary aspergillosis. Cyclophosphamide/cortisone acetate-treated mice (8 per group) were infected intranasally with an inoculum of 2.5 × 105 ΔcspA, ΔECM33, or ΔcspA ΔECM33 conidia/mouse. Percent survival was monitored throughout the 28-day study period. This experiment was repeated twice, with similar results.

DISCUSSION

We provide a comprehensive analysis of the A. fumigatus repeat-rich cspA gene, first described in our previous study (27). We performed a detailed characterization of the localization and expression of the protein encoded by cspA, the effects of cspA deletion and overexpression on the fungal phenotype, the protein's functional interactions with other CWPs, and the interaction of cspA null mutants with cells of the innate immune system. We show that cspA can be extracted by HF from the cell wall, suggesting that it is a GPI-anchored CWP. Interestingly, in dormant conidia, cspA-encoded protein is masked by the dense outer layer of hydrophobins that protect the conidium (42). The hydrophobin layer is shed during early germination, exposing underlying proteins such as cspA.

cspA participates in the organization and integrity of the conidial cell wall.

Lack of cspA resulted in more rapid conidial germination, structural cell wall damage, and weakening of the cell wall to physical and chemical agents, suggesting that the conidial cell wall is markedly weaker and more pliable in the absence of cspA. In contrast, overexpression of cspA resulted in delayed conidial germination and increased resistance to cell wall-degrading enzymes, suggesting that overexpression may harden the cell wall. Rapid conidial germination has been noted in several previously described A. fumigatus cell wall mutants, including strains deleted for ECM33 (37), AGS3 encoding α(1-3)-glucan synthase (31), the GDP-mannose pyrophosphorylase gene (21), and the transcription factor Ace2 that controls the expression of ECM33 and AGS3 (15).

cspA functionally interacts with ECM33 and GEL2, resulting in substantially increased damage to the conidial cell wall.

Analysis of synthetic sick/lethal (SSL) interactions, in which two nonessential functionally related genes are deleted in a single organism, is commonly used to analyze genetic interactions in model fungi (39, 43). We and others have shown that there is considerable redundancy for genes encoding CWPs in A. fumigatus due to their overlapping functions and compensatory responses (27, 32, 33). We therefore used the SSL approach to identify interactions among novel A. fumigatus CWPs. We created double-deletion strains with cspA deleted along with Afu6g14090 and Afu2g05150 encoding repeat-rich wall proteins (27), ECM33 (5, 37), GEL2 (glucanosyltransferase) (33), and chsG (chitin synthase) (32) and tested their phenotypes. The ΔcspA ΔGEL2 and ΔcspA ΔECM33 double mutants had the most noticeably altered conidial phenotypes compared to the isogenic WT and single mutant strains. These included (i) greater conidial susceptibility to physical disruption by glass beads and cell wall-degrading enzymes, (ii) drastically decreased conidial adhesion to ECM, and (iii) increased damage to the conidial wall ultrastructure, including apparent peeling of the outermost melanized layer consisting of interwoven rodlet fascicles containing hydrophobins (19), and increased surface exposure of chitin, mannose, and glucan. In WT conidia, these polysaccharides are masked by the outer electron-dense layer containing melanin and rodlet hydrophobins. This layer is normally revealed only during conidial germination or following treatment with the cell wall biosynthesis inhibitor caspofungin (17, 24, 40). Similar exposure of surface polysaccharides has also been shown in albino A. fumigatus mutants lacking conidial melanin (6, 29), but to the best of our knowledge, it has not been shown to characterize mutants in which genes encoding key wall proteins such cspA, ECM33, and GEL2 have been deleted.

We propose the following model to explain most of our findings: the cspA-encoded protein is primarily composed of serine-rich repeats and appears to be heavily glycosylated. We speculate that this may enable it to form cross-links with glucan or chitin, thus serving as a scaffold or cross-linker that enhances the strength of the fungal cell wall. Therefore, deletion of cspA results in cell wall weakening, loss of layering, and subsequent exposure of the underlying polysaccharides. Interestingly, a similar scaffolding role has been suggested for the PIR-encoded wall proteins in yeast which contain multiple glutamine-rich repeats that are covalently linked to β-glucan (10, 13). It is tempting to speculate that changes in the number of cspA-encoded repeats found in different isolates of A. fumigatus subtly affect their rates of conidial germination, the rigidity of their cell walls, and the extent of their recognition and killing by innate immune cells. We are currently testing this hypothesis.

Why does additional damage to the conidial wall occur when GEL2 or ECM33 is deleted together with cspA? ECM33 is found in both yeast and filamentous fungi and is involved in maintaining cell wall integrity (5, 30, 37, 41). In A. fumigatus, deletion of ECM33 results in the formation of enlarged, clumped, poorly adherent conidia which, like the ΔcspA mutant, undergo accelerated germination in liquid medium (5, 37). Here we demonstrate that the cell wall of the ΔECM33 mutant is structurally disorganized and physically weakened and contains exposed β-glucan, chitin, mannose, and sialic acid residues on its surface. Taking into account the additive phenotype of the ΔcspA ΔECM33 mutant, these results suggest that both cspA and ECM33 affect different nonoverlapping aspects of conidial wall organization and plasticity. GEL2 is a GPI-anchored glucanosyltransferase of the GAS/PHR/EPD family (26). Deletion of GEL2 results in slower growth and altered cell wall composition and architecture, including loss of conidial melanin in the outer layer (33). GEL2 is thought to participate in the elongation of β(1-3)-glucan, providing new ends for anchoring and cross-linking other polysaccharides to the cell wall network. We propose that the increased cell wall damage seen in the ΔcspA ΔGEL2 mutant is due to the loss of two nonoverlapping pathways involved in cross-linking the polysaccharide scaffolding of the cell wall.

Increased internalization and killing of the ΔcspA, ΔECM33, and ΔcspA ΔECM33 mutant strains by HuMoDMs and enhanced hyphal damage by PMNLs.

Previous studies have shown that increased exposure of cell surface carbohydrates and in particular β-glucan, as seen following germination or caspofungin pretreatment (1, 17, 24, 40) and in mutants lacking melanin or hydrophobins in the outer layer of the conidial cell wall (6, 7, 29), results in increased phagocytosis and cytokine release by macrophages and increased neutrophil-induced hyphal damage. Blocking experiments with soluble laminarin or anti-dectin 1 antibodies suggest that these effects are mediated through the interaction of exposed β-glucan on the fungal surface and dectin 1 receptors on the cells. We propose that similarly, the increased chitin/glucan/mannan exposure on the surface of the ΔcspA and ΔECM33 mutants compared to that of the WT strain and the further increase in exposure in the ΔcspA ΔECM33 double mutant result in their increased recognition and uptake by HuMoDMs. The higher killing rates of these mutants by HuMoDMs may be due to both faster conidial uptake and the increased weakness of their cell walls.

Although the above findings indicate that the ΔcspA, ΔECM33, and ΔcspA ΔECM33 mutant strains are more susceptible to recognition and killing by immune cells, this did not translate into a reduction in their virulence in a murine pulmonary model of infection. A possible explanation is that the immunosuppressive regimen used interferes with the ability of the immune system to preferentially identify the mutant strains.

In summary, further characterization of the cspA repeat-rich gene showed that it is involved primarily in organization of the conidial cell wall, providing it with resilience to both physical and chemical perturbations. Generation of double mutants suggested that cspA functionally interacts with the cell wall integrity genes ECM33 and GEL2. Loss of cspA-encoded protein following gene deletion exposes polysaccharides on the conidial surface, increasing conidial recognition, uptake, and killing by HuMoDMs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Marta Feldmesser for kindly providing anti-β-glucan MAb 744 and Jean-Paul Latge and Emilia Mellado for graciously providing us with A. fumigatus CBS 144.89 ΔGEL2 and ΔchsG mutant strains.

This work was supported by Israel Science Foundation (ISF) grant 186/09 and Israel Ministry of Health grant 3-5201 to N.O.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 July 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aimanianda V., Bayry J., Bozza S., Kniemeyer O., Perruccio K., Elluru S. R., Clavaud C., Paris S., Brakhage A. A., Kaveri S. V., Romani L., Latge J. P. 2009. Surface hydrophobin prevents immune recognition of airborne fungal spores. Nature 460:1117–1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bainbridge B. W. 1971. Macromolecular composition and nuclear division during spore germination in Aspergillus nidulans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 66:319–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balajee S. A., de Valk H. A., Lasker B. A., Meis J. F., Klaassen C. H. 2008. Utility of a microsatellite assay for identifying clonally related outbreak isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Microbiol. Methods 73:252–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balajee S. A., Tay S. T., Lasker B. A., Hurst S. F., Rooney A. P. 2007. Characterization of a novel gene for strain typing reveals substructuring of Aspergillus fumigatus across North America. Eukaryot. Cell 6:1392–1399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chabane S., Sarfati J., Ibrahim-Granet O., Du C., Schmidt C., Mouyna I., Prevost M. C., Calderone R., Latge J. P. 2006. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored Ecm33p influences conidial cell wall biosynthesis in Aspergillus fumigatus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:3259–3267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chai L. Y., Netea M. G., Sugui J., Vonk A. G., van de Sande W. W., Warris A., Kwon-Chung K. J., Jan Kullberg B. 23November2009, posting date Aspergillus fumigatus conidial melanin modulates host cytokine response. Immunobiology [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dagenais T. R., Keller N. P. 2009. Pathogenesis of Aspergillus fumigatus in invasive aspergillosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 22:447–465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Damveld R. A., Arentshorst M., VanKuyk P. A., Klis F. M., van den Hondel C. A., Ram A. F. 2005. Characterisation of CwpA, a putative glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored cell wall mannoprotein in the filamentous fungus Aspergillus niger. Fungal Genet. Biol. 42:873–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Groot P. W., Hellingwerf K. J., Klis F. M. 2003. Genome-wide identification of fungal GPI proteins. Yeast 20:781–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Groot P. W., Ram A. F., Klis F. M. 2005. Features and functions of covalently linked proteins in fungal cell walls. Fungal Genet. Biol. 42:657–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Groot P. W., Yin Q. Y., Weig M., Sosinska G. J., Klis F. M., de Koster C. G. 2007. Mass spectrometric identification of covalently bound cell wall proteins from the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast 24:267–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denning D. W. 1998. Invasive aspergillosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 26:781–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ecker M., Deutzmann R., Lehle L., Mrsa V., Tanner W. 2006. Pir proteins of Saccharomyces cerevisiae are attached to beta-1,3-glucan by a new protein-carbohydrate linkage. J. Biol. Chem. 281:11523–11529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eisenhaber B., Schneider G., Wildpaner M., Eisenhaber F. 2004. A sensitive predictor for potential GPI lipid modification sites in fungal protein sequences and its application to genome-wide studies for Aspergillus nidulans, Candida albicans, Neurospora crassa, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J. Mol. Biol. 337:243–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ejzykowicz D. E., Cunha M. M., Rozental S., Solis N. V., Gravelat F. N., Sheppard D. C., Filler S. G. 2009. The Aspergillus fumigatus transcription factor Ace2 governs pigment production, conidiation and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 72:155–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erjavec Z., Kluin-Nelemans H., Verweij P. E. 2009. Trends in invasive fungal infections, with emphasis on invasive aspergillosis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 15:625–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gersuk G. M., Underhill D. M., Zhu L., Marr K. A. 2006. Dectin-1 and TLRs permit macrophages to distinguish between different Aspergillus fumigatus cellular states. J. Immunol. 176:3717–3724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenstein S., Shadkchan Y., Jadoun J., Sharon C., Markovich S., Osherov N. 2006. Analysis of the Aspergillus nidulans thaumatin-like cetA gene and evidence for transcriptional repression of pyr4 expression in the cetA-disrupted strain. Fungal Genet. Biol. 43:42–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hohl T. M., Van Epps H. L., Rivera A., Morgan L. A., Chen P. L., Feldmesser M., Pamer E. G. 2005. Aspergillus fumigatus triggers inflammatory responses by stage-specific beta-glucan display. PLoS Pathog. 1:e30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jadoun J., Shadkchan Y., Osherov N. 2004. Disruption of the Aspergillus fumigatus argB gene using a novel in vitro transposon-based mutagenesis approach. Curr. Genet. 45:235–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang H., Ouyang H., Zhou H., Jin C. 2008. GDP-mannose pyrophosphorylase is essential for cell wall integrity, morphogenesis and viability of Aspergillus fumigatus. Microbiology 154:2730–2739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin J., Lee Y. K., Wickes B. L. 2004. Simple chemical extraction method for DNA isolation from Aspergillus fumigatus and other Aspergillus species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:4293–4296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kashi Y., King D. G. 2006. Simple sequence repeats as advantageous mutators in evolution. Trends Genet. 22:253–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamaris G. A., Lewis R. E., Chamilos G., May G. S., Safdar A., Walsh T. J., Raad I. I., Kontoyiannis D. P. 2008. Caspofungin-mediated beta-glucan unmasking and enhancement of human polymorphonuclear neutrophil activity against Aspergillus and non-Aspergillus hyphae. J. Infect. Dis. 198:186–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Latge J. P., Steinbach W. J. (ed.). 2009. Aspergillus fumigatus and aspergillosis. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 26.Latge J. P., Mouyna I., Tekaia F., Beauvais A., Debeaupuis J. P., Nierman W. 2005. Specific molecular features in the organization and biosynthesis of the cell wall of Aspergillus fumigatus. Med. Mycol. 43(Suppl. 1):S15–S22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levdansky E., Romano J., Shadkchan Y., Sharon H., Verstrepen K. J., Fink G. R., Osherov N. 2007. Coding tandem repeats generate diversity in Aspergillus fumigatus genes. Eukaryot. Cell 6:1380–1391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luther K., Rohde M., Sturm K., Kotz A., Heesemann J., Ebel F. 2008. Characterisation of the phagocytic uptake of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia by macrophages. Microbes Infect. 10:175–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luther K., Torosantucci A., Brakhage A. A., Heesemann J., Ebel F. 2007. Phagocytosis of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia by murine macrophages involves recognition by the dectin-1 beta-glucan receptor and Toll-like receptor 2. Cell Microbiol. 9:368–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martinez-Lopez R., Park H., Myers C. L., Gil C., Filler S. G. 2006. Candida albicans Ecm33p is important for normal cell wall architecture and interactions with host cells. Eukaryot. Cell 5:140–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maubon D., Park S., Tanguy M., Huerre M., Schmitt C., Prevost M. C., Perlin D. S., Latge J. P., Beauvais A. 2006. AGS3, an alpha(1-3)glucan synthase gene family member of Aspergillus fumigatus, modulates mycelium growth in the lung of experimentally infected mice. Fungal Genet. Biol. 43:366–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mellado E., Aufauvre-Brown A., Gow N. A., Holden D. W. 1996. The Aspergillus fumigatus chsC and chsG genes encode class III chitin synthases with different functions. Mol. Microbiol. 20:667–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mouyna I., Morelle W., Vai M., Monod M., Lechenne B., Fontaine T., Beauvais A., Sarfati J., Prevost M. C., Henry C., Latge J. P. 2005. Deletion of GEL2 encoding for a beta(1-3)glucanosyltransferase affects morphogenesis and virulence in Aspergillus fumigatus. Mol. Microbiol. 56:1675–1688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oh S. H., Cheng G., Nuessen J. A., Jajko R., Yeater K. M., Zhao X., Pujol C., Soll D. R., Hoyer L. L. 2005. Functional specificity of Candida albicans Als3p proteins and clade specificity of ALS3 alleles discriminated by the number of copies of the tandem repeat sequence in the central domain. Microbiology 151:673–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Osherov N., May G. 2000. Conidial germination in Aspergillus nidulans requires RAS signaling and protein synthesis. Genetics 155:647–656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paris S., Debeaupuis J. P., Crameri R., Carey M., Charles F., Prevost M. C., Schmitt C., Philippe B., Latge J. P. 2003. Conidial hydrophobins of Aspergillus fumigatus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:1581–1588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Romano J., Nimrod G., Ben-Tal N., Shadkchan Y., Baruch K., Sharon H., Osherov N. 2006. Disruption of the Aspergillus fumigatus ECM33 homologue results in rapid conidial germination, antifungal resistance and hypervirulence. Microbiology 152:1919–1928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Segal B. H. 2009. Aspergillosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 360:1870–1884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Son S., Osmani S. A. 2009. Analysis of all protein phosphatase genes in Aspergillus nidulans identifies a new mitotic regulator, fcp1. Eukaryot. Cell 8:573–585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steele C., Rapaka R. R., Metz A., Pop S. M., Williams D. L., Gordon S., Kolls J. K., Brown G. D. 2005. The beta-glucan receptor dectin-1 recognizes specific morphologies of Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS Pathog. 1:e42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Terashima H., Hamada K., Kitada K. 2003. The localization change of Ybr078w/Ecm33, a yeast GPI-associated protein, from the plasma membrane to the cell wall, affecting the cellular function. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 218:175–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thau N., Monod M., Crestani B., Rolland C., Tronchin G., Latge J. P., Paris S. 1994. rodletless mutants of Aspergillus fumigatus. Infect. Immun. 62:4380–4388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tong A. H., Boone C. 2006. Synthetic genetic array analysis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Mol. Biol. 313:171–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verstrepen K. J., Jansen A., Lewitter F., Fink G. R. 2005. Intragenic tandem repeats generate functional variability. Nat. Genet. 37:986–990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Verstrepen K. J., Klis F. M. 2006. Flocculation, adhesion and biofilm formation in yeasts. Mol. Microbiol. 60:5–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Verstrepen K. J., Reynolds T. B., Fink G. R. 2004. Origins of variation in the fungal cell surface. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:533–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vora S., Chauhan S., Brummer E., Stevens D. A. 1998. Activity of voriconazole combined with neutrophils or monocytes against Aspergillus fumigatus: effects of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2299–2303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wasylnka J. A., Moore M. M. 2000. Adhesion of Aspergillus species to extracellular matrix proteins: evidence for involvement of negatively charged carbohydrates on the conidial surface. Infect. Immun. 68:3377–3384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang N., Harrex A. L., Holland B. R., Fenton L. E., Cannon R. D., Schmid J. 2003. Sixty alleles of the ALS7 open reading frame in Candida albicans: ALS7 is a hypermutable contingency locus. Genome Res. 13:2005–2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao X., Oh S. H., Jajko R., Diekema D. J., Pfaller M. A., Pujol C., Soll D. R., Hoyer L. L. 2007. Analysis of ALS5 and ALS6 allelic variability in a geographically diverse collection of Candida albicans isolates. Fungal Genet. Biol. 44:1298–1309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]