Abstract

Histone-like protein H1 (H-NS) family proteins are nucleoid-associated proteins (NAPs) conserved among many bacterial species. The IncP-7 plasmid pCAR1 is transmissible among various Pseudomonas strains and carries a gene encoding the H-NS family protein, Pmr. Pseudomonas putida KT2440 is a host of pCAR1, which harbors five genes encoding the H-NS family proteins PP_1366 (TurA), PP_3765 (TurB), PP_0017 (TurC), PP_3693 (TurD), and PP_2947 (TurE). Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) demonstrated that the presence of pCAR1 does not affect the transcription of these five genes and that only pmr, turA, and turB were primarily transcribed in KT2440(pCAR1). In vitro pull-down assays revealed that Pmr strongly interacted with itself and with TurA, TurB, and TurE. Transcriptome comparisons of the pmr disruptant, KT2440, and KT2440(pCAR1) strains indicated that pmr disruption had greater effects on the host transcriptome than did pCAR1 carriage. The transcriptional levels of some genes that increased with pCAR1 carriage, such as the mexEF-oprN efflux pump genes and parI, reverted with pmr disruption to levels in pCAR1-free KT2440. Transcriptional levels of putative horizontally acquired host genes were not altered by pCAR1 carriage but were altered by pmr disruption. Identification of genome-wide Pmr binding sites by ChAP-chip (chromatin affinity purification coupled with high-density tiling chip) analysis demonstrated that Pmr preferentially binds to horizontally acquired DNA regions. The Pmr binding sites overlapped well with the location of the genes differentially transcribed following pmr disruption on both the plasmid and the chromosome. Our findings indicate that Pmr is a key factor in optimizing gene transcription on pCAR1 and the host chromosome.

Nucleoid-associated proteins (NAPs) have architectural and regulatory functions in bacterial cells. Bacterial chromosomal DNA is folded into a compact nucleoid body by NAPs (9, 11). Because of their DNA-binding ability, NAPs can also influence the expression of genes (9, 11). Histone-like protein H1 (H-NS), a NAP family member, is an oligomeric DNA-binding protein identified in Escherichia coli because of its effect on transcription in vitro (13, 16). H-NS acts as a global repressor and binds to horizontally acquired DNA regions (28). Plasmid-encoded H-NS can function as a “stealth” protein to switch off gene expression on chromosomes or plasmids and to maintain host cell fitness (15). H-NS also interacts with paralogous proteins, such as StpA and Hfp in E. coli, or other NAPs (12, 16, 27).

Tendeng et al. (39) suggested that conserved MvaT proteins from Pseudomonas bacteria belong to the H-NS family, despite their limited sequence similarity with H-NS. Recently MvaT and MvaU from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, functional homologous H-NS proteins from Pseudomonas bacteria, were shown to interact with each other (44). Castang et al. (5) reported that these two H-NS family proteins bind to the same chromosomal regions and that they function coordinately. Interestingly, P. putida KT2440 has five genes encoding H-NS family proteins, and recently Renzi et al. (30) named them as follows: PP_1366 (turA), PP_3765 (turB), PP_0017 (turC), PP_3693 (turD), and PP_2947 (turE). TurA and TurB were copurified as the TOL plasmid (pWW0) upper operon repressors A and B, respectively, and both bound to the Pu promoter (a σ54-dependent promoter of the operon encoding enzymes for the upper pathway of toluene degradation in pWW0), suggesting that these two proteins could interact with each other (31). Renzi et al. (30) proposed that TurA and TurB belonged to groups I and II, respectively, and that these groups contained orthologous H-NS family proteins present in all Pseudomonadaceae species. Conversely, TurC, TurD, and TurE belonged to group III, which contained species-specific H-NS family proteins (30).

The self-transmissible pCAR1, an IncP-7 archetypal plasmid, endows the host strain with carbazole-degrading ability (23, 36, 38). pCAR1 carries the pmr gene, encoding the H-NS family protein designated Pmr (plasmid-encoded MvaT-like regulator) (25) and belonging to the above-mentioned group III. The effect of plasmid carriage on host strains may change in different hosts, and therefore, we performed transcriptome comparisons between pCAR1-free and pCAR1-containing KT2440 strains (25, 35). Based on the comparisons, pCAR1 carriage affected the iron acquisition system of the host KT2440 strain, enhanced resistance to chloramphenicol by inducing the mexEF-oprN operon, and induced the transcription of PP_3700 (parI) (35). We also discovered that pmr was transcribed in four distinct Pseudomonas host bacterial strains (26, 35). These data suggest that Pmr could interact with other H-NS family proteins, such as TurA, TurB, TurC, TurD, and TurE, encoded on the KT2440 chromosome.

In the present study, we assessed the in vivo transcriptional profiles of genes encoding H-NS family proteins on both pCAR1 and the KT2440 chromosome. Additionally, we investigated the in vitro interaction of Pmr with itself and with other H-NS family proteins. Furthermore, we assessed the effect of pmr disruption on the transcriptome of the host strain and identified genome-wide Pmr-binding sites. Taken together, we clarified the role of Pmr as a horizontally acquired H-NS family protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli strains for cloning and expression of genes were grown in L broth (LB) (32) at 37°C or 25°C, and the Pseudomonas strains were cultivated with LB at 30°C. Ampicillin (Ap) (50 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (Cm) (30 μg/ml), kanamycin (Km) (50 μg/ml), gentamicin (Gm) (120 μg/ml), rifampin (Rif) (250 μg/ml), streptomycin (Sm) (450 μg/ml), or tetracycline (Tc) (12.5 μg/ml) was added to the selective medium. For plate cultures, the above media were solidified with 1.6% agar (wt/vol).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | F− φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 endA1 recA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) deoR thi-1,supE44 gyrA96 relA1 λ−phoA | Toyobo |

| BL21(DE3) | F−ompT hsdS(rB− mB−) gal dcm λ (DE3) | Novagen |

| P. putida | ||

| KT2440 | Naturally Cmr | 2 |

| KT2440(pCAR1) | KT2440 harboring pCAR1 | 31 |

| KT2440(pCAR1Δpmr) | KT2440 harboring pCAR1 carrying disrupted pmr gene by Gmr gene cassette | This study |

| KT2440(pCAR1pmrHis) | KT2440(pCAR1) carrying gene encoding His-tagged Pmr | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pET-26b(+) | Kmr, T7 promoter, lacI, pBR322 replicon | Novagen |

| pET-C-His-pmr | pET-26b(+), NdeI-XhoI fragment containing pmr | This study |

| pFLAG-CTC | Apr, lacI, tac promoter expressing FLAG tag | Sigma |

| pFLAG0017 | pFLAG-CTC, NdeI-SalI fragment containing PP_0017 | This study |

| pFLAG1366 | pFLAG-CTC, NdeI-SalI fragment containing PP_1366 | This study |

| pFLAG2947 | pFLAG-CTC, NdeI-SalI fragment containing PP_2947 | This study |

| pFLAG3693 | pFLAG-CTC, NdeI-SalI fragment containing PP_3693 | This study |

| pFLAG3765 | pFLAG-CTC, NdeI-SalI fragment containing PP_3765 | This study |

| pFLAGpmr | pFLAG-CTC, NdeI-SalI fragment containing pmr | This study |

| pFLP2 | Apr, ori1600 oriT(RP4), Flp recombinase expression vector | 16 |

| pFLP2Km | pFLP2, Kmr gene cassette inserted into its ScaI site | This study |

| pK19mobsacB | Kmr, oriT(RP4) sacB lacZα, pMB1 replicon | 29 |

| pK19mobsacBpmrHis | pK19mobsacB containing gene encoding Pmr with 6× His at its C-terminal end with Gmr gene cassette and FRT site at its 3′-terminal end | This study |

| pK19mobsacBpmrGm | pK19mobsacB, containing 3.8-kb EcoRI-PstI fragment including Gmr gene cassette inserted pmr flanking region (77486-77909 region of pCAR1 was replaced by Gmr gene) | This study |

| pSJ12 | pBluescript II KS(−) with 0.7-kb SmaI fragment containing a nonpolar Gmr gene cassette | 17 |

| pT7Blue T-vector | Apr, lacZα, T7 promoter, f1 origin, pUC/M13 priming sites | Novagen |

| pTKm | pT7Blue T-vector, Kmr gene cassette | 43 |

| pUC18 | Apr, lacZα, pMB9 replicon | 28 |

| pUB11 | pUC18 containing 75211-80781 region of pCAR1 | This study |

DNA manipulations.

Plasmid DNA extraction from E. coli was performed using the alkaline lysis method (32), and total DNA from Pseudomonas strains was extracted using hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide as described previously (1). Restriction enzymes (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA; Toyobo, Tokyo, Japan) and the Ligation High reagent (Toyobo) were used according to the manufacturers' instructions. DNA fragments were extracted from agarose gels using the Ezna gel extraction kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR was performed with Ex Taq Hot Start polymerase (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. All other experiments were performed according to standard methods (32). All primers used are presented in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

RNA extraction.

RNA extractions from strain KT2440, KT2440(pCAR1), or KT2440(pCAR1Δpmr) were performed as follows: an overnight culture of each strain in LB was washed and transferred into 100 ml NMM-4 buffer (37) supplemented with 0.1% succinate by adjusting the turbidity to 0.05 at 600 nm and then incubated at 30°C in a rotating shaker at 120 rpm. At early log phase growth (turbidity of 0.15 to 0.20 at 600 nm), we used the RNAprotect bacterial reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) to stabilize the total RNA in the bacterial cultures, and subsequently, RNA extraction was performed using the RNeasy Midi kit (Qiagen) or Nucleospin RNA II (Macherey-Nagel GmbH & Co. KG, Düren, Germany) according to the manufacturers' instructions. The eluted RNA was treated with RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega, Fitchburg, WI) at 37°C for 30 min. Following inactivation of the DNase by the addition of the stop reagent and subsequent incubation at 65°C for 10 min, RNA samples were repurified with the RNeasy Mini column (Qiagen) or Nucleospin RNA binding column (Macherey-Nagel) according to each manufacturer's RNA cleanup protocol.

Primer extension and pmr disruption.

We identified the transcription start point (tsp) of pmr by primer extension analysis, performed as described previously (25). We used the IRD800-labeled primer PMR-R (Aloka Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), which anneals to the coding region of pmr from +218 to +237 (77782 to 77763 on pCAR1; see Table S1). The extension reaction was performed with 4 μl of 5× First Strand buffer containing 10 μg of total RNA, 2 pmol of the labeled primer, 100 U of SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 40 U of RNaseOUT (Invitrogen), 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 0.5 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) (Toyobo). After denaturation of the RNA and the labeled primer at 65°C for 5 min, the remaining reagents were added, and then the mixture was incubated at 50°C for 30 min. The extended product was purified by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation and then dissolved in 2 μl of H2O and 1 μl of IR2 stop solution (Li-Cor Inc., Lincoln, NE). The solution was then denatured at 95°C for 2 min and subjected to electrophoresis using a Li-Cor model 4200L-2 automated DNA sequencer (Li-Cor). A sequence ladder was obtained using the same primer and the template plasmid pUB11 (Table 1).

pmr disruption in pCAR1 was designed by removing the region containing the tsp (77486 to 77909). The 3.8-kb EcoRI-PstI fragment from 75681 to 79457 in pCAR1 (GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ accession number AB0088420) was inserted into pK19mobsacB (33), and then the SmaI fragment containing the nonpolar Gm resistance cassette of pSJ12 (21) was inserted into blunt-ended SalI-SacI sites from 77486 to 77909 in the opposite direction to yield pK19mobsacBpmrGm. Using a method described previously (29), pK19mobsacBpmrGm was introduced into KT2440(pCAR1) by filter mating with E. coli S17-1(λpir) transformants, and subsequently, double-crossover recombinants were screened.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using the ABI 7300 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) as described previously (25). The primers used for qRT-PCR are shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material, and all of the products were between 100 and 150 bp in length. 16S rRNA was used as an internal normalization standard. All of the reactions were carried out at least in triplicate, and the data were normalized using the average of the internal standard.

Preparation of a KT2440(pCAR1) derivative containing a gene encoding the His-tagged Pmr protein.

The construction of the KT2440(pCAR1) derivative strain expressing Pmr containing six histidine (His) residues at the C terminus was performed using a homologous recombination-based gene replacement system with suicide vectors, antibiotic resistance selection, and sucrose counterselection (33). The preparation of the DNA region to replace the pmr gene with a modified gene that expresses His-tagged Pmr was performed by overlap extension PCR as described by Choi and Schweizer (6). Briefly, the primers Pmr-His01 and Pmr-His02 were used to amplify the His-tagged pmr gene. The primers Pmr-His03 and Pmr-His04 were used to amplify the downstream region of the untagged pmr gene. Simultaneously, the primers Gm-F and Gm-R were used to amplify the Gm cassette flanked by flippase recognition target (FRT) sites from pPS856 (20). The primers used are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. These three partially overlapping DNA fragments were amplified and then spliced together by in vitro overlap extension PCR. The resulting DNA fragment was cloned into the pT7Blue T vector. After verification of the inserted sequence, the fragment was excised and then recombined into the suicide vector pK19mobsacB to yield pK19mobsacBpmrHis. The pK19mobsacBpmrHis construct was introduced into KT2440 by filter mating with E. coli S17-1(λpir) transformants, and double-crossover recombinants were subsequently screened by sucrose counterselection to yield the KT2440(pCAR1) derivative, replacing the pmr gene with a gene encoding the His-tagged Pmr protein. Finally, the Gm resistance gene was removed by site-specific recombination of FRT sites with Flp recombinase supplied from E. coli S17-1(λpir) transformants containing pFLP2Km. Then, pFLP2Km was constructed by insertion of the EcoRV fragment of pTKm (47) containing the Km resistance gene cassette into the ScaI site of pFLP2 (20). PCR analyses were performed to confirm the final construction of the derivative strain.

Western blot analysis for growth phase-dependent expression of Pmr.

Cell lysates for Western blot analyses were prepared using the B-Per reagent (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc., Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The protein samples were quantified using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay reagent kit (Pierce), and 40 μg of protein sample for Pmr or 5 μg of protein sample for the RNA polymerase α subunit was loaded in each lane. Proteins were separated on a 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a Sequi-Blot polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Bio-Rad, Foster City, CA). Anti-His antibody (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Piscataway, NJ) or anti-RNA polymerase α subunit (NeoClone, Madison, WI) was used as the primary antibody, and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) peroxidase-labeled anti-mouse antibody (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences) was used as the secondary antibody. Proteins were detected using the Immobilon Western chemiluminescent horseradish peroxidase (HRP) substrate (Millipore, Billerica, MA), and LAS1000 plus (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan) was used for imaging analyses.

Overexpression of Pmr and other H-NS family proteins in E. coli cells.

To construct the C-terminal-His-tagged Pmr expression plasmid, the pET-26b(+) vector (Novagen, San Mateo, CA) was used. The insert was amplified by PCR using the pCAR1-covered clone pUB11 as template DNA and the primer set with artificial NdeI and XhoI sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the pmr gene. The nucleotide sequence of the insert was confirmed, and the resultant expression plasmid was designated pET-C-His-pmr. To express each C-terminal-FLAG-tagged H-NS family protein (Pmr, PP_0017 [TurC], PP_1366 [TurA], PP_2947 [TurE], PP_3693 [TurD], PP_3765 [TurB]), pFLAG-CTC (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used as a vector. Each insert was amplified by PCR using the primer set with artificial NdeI and SalI sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends of each gene and pUB11 (for pmr) or total DNA of the P. putida strain KT2440 (for others) as a template. The resulting expression plasmids were designated pFLAGpmr, pFLAG0017, pFLAG1366, pFLAG2947, pFLAG3693, pFLAG3765, and expressed FLAG-tagged forms of Pmr, PP_0017 (TurC), PP_1366 (TurA), PP_2947 (TurE), PP_3693 (TurD), and PP_3765 (TurB), respectively. Transformed E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring each expression plasmid of H-NS family proteins was grown at 25°C to a cell turbidity at 600 nm of 0.6 to 0.8 and was induced overnight by the addition of isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) at a final concentration of 0.5 mM. The expression level of each protein was confirmed by Tricine-SDS-PAGE (34).

Pull-down assays.

Pull-down assays were performed using the MagneHis protein purification system (Promega). Cells expressing His-tagged or FLAG-tagged H-NS family proteins were harvested by centrifugation and washed twice with 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0, 4°C) containing 2 mM EDTA and 10% glycerol. Cells were then resuspended in 700 μl of MagneHis binding/wash buffer and broken by ultrasonication, and crude extracts were obtained by centrifugation (17,000 × g, 15 min, 4°C). Protein concentrations were estimated with the Bio-Rad protein assay reagent (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Crude extract (200 μg) containing His-tagged Pmr was mixed with the following amounts of crude extract containing FLAG-tagged proteins, according to each protein expression level: Pmr, 225 μg; TurC, 900 μg; TurA, 450 μg; TurE, 225 μg; TurD, 1350 μg; and TurB, 225 μg. After the addition of 30 μl of MagneHis Ni particles (Promega), the protein mixture was incubated at 4°C and centrifuged (10 rpm, 1 h). Elution of His-tagged Pmr was done according to the manufacturer's instructions. Each protein sample was separated by Tricine-SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane (iBlot gel transfer stack, PVDF, regular; Invitrogen) using the iBlot gel transfer system (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Anti-His antibody (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences) or monoclonal anti-FLAG M2 antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as the primary antibody, and ECL peroxidase-labeled anti-mouse antibody (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences) was used as the secondary antibody. Detection of the proteins was performed similarly to that described above for Western blot analyses.

Phenotype MicroArray (PM) analyses.

Phenotypic differences between KT2440(pCAR1) and KT2440(pCAR1Δpmr) in carbon metabolism were compared for cell respiration of each strain using 96-well plate microarrays (Biolog PM1 and PM2; Biolog, Hayward, CA) (4). Each plate well contained defined medium with a unique carbon compound plus indicator dye for cell respiration, and each medium was made at Biolog. Excluding carbon-free wells (negative controls), the PM1 and PM2 Biolog assays can assess the ability to use 190 carbon compounds as the sole carbon source. Experiments were performed in duplicate, according to the manufacturer's instructions, except that the strains were precultured on R2A plates (1.5% agar) and data collection was performed manually using the Biolog MicroLog MicroStation system.

Tiling array transcriptome analyses of pCAR1 and the KT2440 chromosome.

Transcriptome analyses with our custom-made tiling arrays were performed as described previously (26, 35). Briefly, total RNA was extracted in parallel from samples of each host culture (1 × 109 cells from two exponential-phase cultures [the turbidity of each culture was 0.15 to 0.20 at 600 nm] derived from two independent precultures). cDNAs reverse transcribed from these RNAs were hybridized individually with each microarray chip using the GeneChip hybridization oven 640 (Affymetrix, Inc., Santa Clara, CA) at 60 rpm and at 50°C for 16 h with the KT2440 chromosomal tiling array or at 45°C for 16 h with the pCAR1 tiling array. After washing, staining, and scanning of the chips, the signal intensities for each probe were computed using the Affymetrix Tiling Analysis Software program, v.1.1 (TAS). We used the median signal intensities of the probes located within each gene as an indicator of the expression level. Comparisons between two conditions were performed using each of the biologically duplicated data, and we identified upregulated and downregulated open reading frames (ORFs) with fold changes of >1.5 in the four data comparisons (between replicate 1 of KT2440(pCAR1) and replicate 1 of KT2440(pCAR1Δpmr) and between replicate 1 of KT2440(pCAR1) and replicate 2 of KT2440(pCAR1Δpmr); see Tables S2 to S4 in the supplemental material). The data were visualized using the IGB software package (Affymetrix). The fold change of pmr expression levels between KT2440(pCAR1) and KT2440(pCAR1Δpmr) was only −4.5 to −5.5 (see Table S2) because the Gm resistance gene introduced into the pmr gene was transcribed in the counterdirection to the pmr gene, and the read through from the Gm resistance gene was detected (see Fig. S2).

Chromatin affinity purification coupled with high density tiling chip (ChAP-chip) analysis.

An overnight culture of the KT2440(pCAR1) derivative expressing 6-His-tagged Pmr in LB at 30°C was inoculated into 200 ml NMM-4 supplemented with 0.1% (wt/vol) succinate to obtain an initial turbidity at 600 nm of 0.05 and then incubated at 30°C in a rotating shaker at 120 rpm for 4 h to a turbidity at 600 nm of 0.20 to 0.30. The His-tagged Pmr and DNA in the cells were in vivo cross-linked by the addition of formaldehyde to a final concentration of 1% for 15 min with shaking at 30°C. The cross-linking reaction was quenched by the addition of glycine to a final concentration of 125 mM for 5 min, and then the cells were washed twice with chilled Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer (pH 8.0). The resulting harvested cells were disrupted by sonication on ice in 2.4 ml of QuickPick Imac wash buffer (Bio-Nobile, Turku, Finland). After centrifugation (17,000 × g, 20 min), the supernatant was affinity purified using the QuickPick Imac metal affinity kit (Bio-Nobile) according to the manufacturer's instructions to yield 6-His-tagged Pmr. Cross-links were dissociated by heating at 65°C for 4 h, and the resulting DNA was purified using the Qiaquick kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Terminal labeling of the purified DNA fragments and hybridization to the pCAR1 and KT2440 chromosomal tiling arrays were performed as described above. Signal intensities of DNA hybridization on the arrays were computed to identify protein-binding sites using TAS, which uses nonparametric quantile normalization and a Hodges-Lehmann estimator for fold enrichment (Affymetrix Tiling Array Software v1.1 User's Guide) with the biologically duplicated affinity-purified fractions (treatment DNA) and those of DNA isolated from the biologically duplicated whole-cell extract fractions before purification (control DNA).

Microarray data accession number.

The array data reported in this article have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (GEO; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under the GEO Series accession no. GSE21968.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Transcriptional profiles of pmr and other H-NS family genes in P. putida KT2440.

Transcriptional levels of H-NS family proteins change in the presence or absence of other H-NS homologous proteins, and they are not always transcribed under the same growth condition (7, 27, 44). First, we determined the transcription start point (tsp) of pmr to construct a pmr disruptant strain by extinguishing its transcription (see Materials and Methods). The tsp of pmr (+1) was located 69 bp upstream of the annotated start codon of Pmr (nucleotide at 77571 of pCAR1; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), corroborating our findings using a previous tiling array analysis (26). To clarify the transcriptional profiles of the H-NS family genes, qRT-PCR analyses were performed for KT2440, KT2440(pCAR1), and KT2440(pCAR1Δpmr), along their growth curves. As demonstrated in Fig. 1A and B, the transcriptional levels of turA (PP_1366), turC (PP_0017), and turD (PP_3693) in early log-phase growth were higher than those in the stationary phase, whereas turB (PP_3765) and turE (PP_2947) were transcribed in the late log and stationary growth phases, compared with the early log phase growth in KT2440, confirming a previous report (48). In KT2440(pCAR1), pmr was transcribed in early log phase growth (the cell turbidity was about 0.18 at 600 nm), and its transcription was reduced in the stationary phase (the cell turbidity was 0.56) (Fig. 1A and B). The transcriptional profiles of other H-NS-encoding genes did not change with pCAR1 carriage or with pmr disruption (Fig. 1A and B). Similar results were also obtained by transcriptome analysis using tiling arrays with these three strains in early log phase growth: the signal intensities of the H-NS family proteins did not change with pCAR1 carriage or with pmr disruption (Fig. 1C). Taken together with the results of the transcriptional profiles of pmr, turA, turB, turC, turD, and turE, pmr and turA were the primary transcribed genes in the early log phase growth, whereas turB was transcribed in the late log and stationary growth phases in KT2440(pCAR1) (Fig. 1B and C).

FIG. 1.

Transcriptional profiles of the genes encoding H-NS family proteins and translational profiles of Pmr. (A) Growth curves of KT2440 (diamond), KT2440(pCAR1) (square), and KT2440(pCAR1Δpmr) (triangle). The turbidity of each cell culture was measured at 600 nm. (B) The mRNA levels of the genes encoding H-NS family proteins (Pmr, PP_0017 [TurC], PP_1366 [TurA], PP_2947 [TurE], PP_3693 [TurD], and PP_3765 [TurB]) were measured by qRT-PCR. Means and standard deviations (error bars) of triplicate data are shown. (C) Signal intensities of genes encoding H-NS family proteins in tiling array analyses with KT2440 (black), KT2440(pCAR1) (white), and KT2440(pCAR1Δpmr) (gray). Biologically duplicated data are shown. (D) The amount of Pmr-His protein was monitored at different points in the growth curve of KT2440(pCAR1). Results of Western blot analysis using anti-His are shown in the upper panel, and those with use of an anti-RNA polymerase α subunit as a control for sample loading are shown in the lower panel.

Translational profiles of Pmr in P. putida KT2440(pCAR1).

Because previous reports indicated that the translational profiles of some H-NS family proteins were different from their transcriptional profiles (7, 44), we confirmed the translational profiles of Pmr. Western blot analysis was performed with the crude extract from KT2440(pCAR1) cells in the growth phase that expressed C-terminal-6-His-tagged Pmr. Pmr signals in KT2440(pCAR1) were detected throughout the growth phase, and translational levels of Pmr were higher in the late log and stationary growth phases than in early log phase growth (Fig. 1A and D). Notably, the translational profile of Pmr differed from the transcriptional profile (Fig. 1B and D) and from those of other previously reported H-NS family proteins (7, 44). Currently, we could not explain the physiological meaning(s) of the discrepancy between pmr transcription and translation. Reciprocal transcription and translation of a gene encoding an H-NS-like protein, Sfh of pSF-R27, have been investigated in detail before (14). Those authors showed that a blockade of sfh mRNA translation occurred in early exponential growth and was relieved at the onset of stationary phase, responsible for the expression pattern of Sfh (14). They proposed that confinement of Sfh expression may ensure that the conjugative plasmid pSF-R27 carrying sfh minimizes the disruption on the physiology of the host cell (14). It is therefore possible that Pmr translation may have been regulated in a similar manner to reduce effects on the host cell; however, further investigations are still necessary to clearly explain the Pmr translation mechanism.

Pmr interacts with itself and with three other H-NS family proteins.

Many reports have indicated that H-NS family proteins can interact with themselves and with paralogous proteins, such as StpA, Hfp, or MvaU (7, 22, 27, 44). Thus, Pmr may interact with itself or other H-NS family proteins expressed from the host chromosome. To assess this possibility, we performed pull-down assays followed by Western blot analyses to clarify whether Pmr interacted with itself and/or other H-NS family proteins. As revealed in Fig. 2B (lane 1 of each sample), we detected anti-FLAG signals from each crude extract, indicating that each H-NS family protein was expressed in E. coli. Anti-His signals were also detected in each eluant after the pull-down assays, indicating that His-tagged Pmr existed in each eluant (data not shown). In contrast, anti-FLAG signals in the eluants were detected only in the mixtures of His-tagged Pmr with FLAG-tagged Pmr, TurA, TurB, and TurE, whereas those with FLAG-tagged TurC and TurD were not detected (Fig. 2B, lane 2 of each sample). This result indicates that the strength of the interactions between Pmr and itself or between Pmr and TurA, TurB, or TurE is higher than those between Pmr and TurC or TurD. One important feature of H-NS family proteins is their modular structure (10). Additionally, KT2440 proteins have putative structures similar to that of H-NS: a well-conserved amino-terminal oligomerization domain (see Fig. S3A, blue box, in the supplemental material), a conserved carboxyl-terminal nucleic acid-binding domain (see Fig. S3A, red box), and a poorly conserved flexible linker that connects the two aforementioned domains (see Fig. S3A). When the amino acid sequences of the H-NS family proteins of KT2440 were aligned, their putative oligomerization domains at the N-terminal regions were well conserved (see Fig. S3A), although the identity between H-NS family proteins of KT2440, including Pmr and the H-NS protein of E. coli, was low (see Fig. S3B). Although it was difficult to predict why Pmr could have heteromeric interactions with three H-NS family proteins but not with two other H-NS family proteins, some residues from the latter may be important for the interaction. Notably, the homologous proteins of TurA and TurB are conserved in all Pseudomonadaceae species, but TurC, TurD, and TurE are species-specific proteins (30) encoded in the putative horizontally acquired DNA region (24). Taken together with the result that turA and turB were transcribed primarily in the early log and late log growth phases, respectively, Pmr may primarily interact with TurA and TurB, although the functional significance of TurE is presently unclear. Considering the reciprocal transcription and translation of Pmr (Fig. 1B and D), it is necessary to analyze the translational levels of Tur proteins in vivo.

FIG. 2.

Identification of the interaction among H-NS family proteins by in vitro pull-down assays. (A) Tricine-SDS-PAGE profiles of each H-NS family protein expressed in E. coli. “M” indicates protein marker (XL ladder Low, APRO Life Science Institute, Inc., Tokushima, Japan), and “1” and “2” indicate the crude extract of cells expressing each FLAG-tagged H-NS family protein and the sample after the pull-down assay, respectively. “His” indicates the crude extract of cells expressing His-tagged Pmr. (B) Western blot analysis using anti-FLAG and the same samples in Tricine-SDS-PAGE shown in panel A.

Phenotypic alteration by pmr disruption.

To assess the effects of pmr disruption on the phenotypes of KT2440(pCAR1), comparisons of the catabolic abilities of KT2440(pCAR1) and KT2440(pCAR1Δpmr) were performed using Biolog PM analyses by measuring the absorbance of colored cultures derived from a tetrazolium dye used as a reporter of cell respiration. From the comparisons for each of the 190 substrates as a sole carbon source, reproducible reductions of the maximum absorbance of the color were observed in the KT2440(pCAR1Δpmr) culture, compared with results for the KT2440(pCAR1) culture, with nine compounds (d-fructose, l-serine, l-valine, saccharic acid, d-malic acid, pyruvic acid, methyl pyruvate, d-ribono-1,4-lactone, and inosine; see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). We did not detect any difference between the two strains in the culture using the other carbon sources (for example, the result with d-glucose was shown in Fig. S4). These results indicated that pmr disruption affected the catabolic abilities of KT2440(pCAR1) with several carbon sources, suggesting that Pmr may function as a global regulator of many genes.

Transcriptome alteration by pmr disruption.

To confirm the effects of pmr disruption on the host cells, we performed transcriptome comparisons between KT2440(pCAR1) and KT2440(pCAR1Δpmr) using custom-made tiling arrays of genome sequences of pCAR1 and the KT2440 chromosome (26, 35). To evaluate the transcriptional and translational profiles of pmr (Fig. 1), transcriptome comparisons were performed for cells in early log phase growth.

Overview.

We found that the transcription of 31 genes on pCAR1 and 159 genes on the KT2440 chromosome were altered by pmr disruption, with a fold change of >1.5 (see Materials and Methods; see also Tables S2 and S3 in the supplemental material). We identified 2 and 19 upregulated genes on pCAR1 and the KT2440 chromosome, respectively, and 29 and 140 downregulated genes on pCAR1 and the KT2440 chromosome, respectively. Based on our previous study (35), we identified 112 genes altered by pCAR1 carriage with a fold change of >1.5 in both of the duplicate data (see Table S3). Notably, the number of downregulated genes following pmr disruption was larger than that with pCAR1 carriage (see Fig. S5), suggesting that Pmr may play an important role in mediating the transcription of the chromosomal genes of the host KT2440 by pCAR1 carriage. The comparison of the transcriptome changes with pCAR1 carriage with those with pmr disruption enabled us to classify 5,398 genes of KT2440 (after rRNA and tRNA removal) based on their transcriptional patterns. First, the transcription of 5,146 genes was not affected by pCAR1 carriage or by pmr disruption. Among the remaining 252 genes, 43 (group A) or 50 (group B) were upregulated or downregulated by pCAR1 carriage, respectively, but neither of their transcription levels was affected by pmr disruption (Fig. 3; see also Table S4). Only one gene (group D) was downregulated by both pCAR1 carriage and pmr disruption (no gene was classified into group C) (Fig. 3 and Table 2; see also Table S4). Seventeen genes (group E) were upregulated by pCAR1 carriage but downregulated by pmr disruption, and one gene (group F) was the reverse (Fig. 3; see also Table S4). In total, 122 genes (group G) or 18 genes (group H) were upregulated or downregulated by pmr disruption, respectively, but neither group was affected by pCAR1 carriage (Fig. 3; see also Table S4). Doyle et al. (15) proposed that these H-NS proteins encoded on plasmids have “stealth” functions to minimize the effect on host strain fitness, comparing the number of genes whose transcriptional levels were altered in the presence or absence of the H-NS protein. Regarding KT2440(pCAR1), the number of differentially transcribed genes with pmr disruption (159 genes on the chromosome) was larger than that with pCAR1 carriage (112 genes). Additionally, 88% of them (belonging to group G or H) were altered only by the absence of Pmr, suggesting that Pmr had a “stealth” function, as mentioned above. The transcription levels of only 12% of the differentially transcribed genes with pmr disruption (18 genes) reverted to levels similar to those in pCAR1-free KT2440 (groups E and F in Fig. 3; see also Table S4), suggesting that these genes were regulated primarily by Pmr itself, directly or indirectly. These results suggest that Pmr is a key global regulator of many genes, both on pCAR1 and on the host chromosome.

FIG. 3.

Classification of the differentially transcribed genes by pCAR1 carriage and/or pmr disruption. Blue, red, and green bars indicate the relative transcription levels in KT2440, KT2440(pCAR1), and KT2440(pCAR1Δpmr), respectively.

TABLE 2.

Number and percentage of ORFs on the putative horizontally acquired DNA region in each group

| Category | No. (%) of ORFs |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | Group B | Group C | Group D | Group E | Group F | Group G | Group H | Total ORFs | |

| ORFs on putative horizontally-acquired DNA region | 5 (12) | 14 (28) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (24) | 0 (0) | 47 (39) | 5 (28) | 1,105 (20) |

| ORFs classified | 43 | 50 | 0 | 1 | 17 | 1 | 122 | 18 | 5,398 |

Martins dos Santos et al. (24) demonstrated that KT2440 had many putative horizontally acquired DNA regions. These regions include 1,105 ORFs, corresponding to about 20% of the total ORFs in KT2440. Because H-NS family proteins bind to horizontally acquired DNA regions (16, 28), we calculated the ratio of ORFs in the regions in the above differentially transcribed genes (Fig. 3). Of the 112 genes (Fig. 3, groups A to F) differentially transcribed by pCAR1 carriage, 23 (21%) were located in the putative horizontally acquired DNA region (Table 2; see also Table S4 in the supplemental material). Conversely, 56 (35%) of 159 genes differentially transcribed by pmr disruption (Fig. 3, groups C to H) were in this region (Table 2; see also Table S4). Notably, the proportions of groups B, G, and H were high: 28%, 39%, and 28%, respectively (Table 2; see also Table S4). The average G+C content of pCAR1 and the KT2440 chromosome is 56.3% and 61.6%, respectively. We then calculated the G+C content in the 500 bp upstream of each ORF. The G+C content of pCAR1-borne genes differentially transcribed by pmr disruption was significantly below the average: for most upstream regions of 30 among 31 affected ORFs (Table 3), it was below 61.6%, and for those of 27 ORFs, including the car or parAB genes (see Table S2), it was even below 56.3% (Table 3). Concerning the ORFs on the KT2440 chromosome, the G+C content of the upstream regions of 92 (58%) among 159 ORFs was below 61.6%, and that for 37 ORFs was below 56.3% (Table 3). As revealed in Table 3, the ratio of these ORFs to the total affected ORFs was higher (87% in pCAR1 and 23% in the KT2440 chromosome) than the ratio of the ORFs whose upstream regions were low in G+C content (below 56.3%) to the total ORFs (64% in pCAR1 and 17% in the KT2440 chromosome). Notably, the ORFs with a ratio of <56.3% in the upstream region (16 ORFs) among the ORFs affected by pCAR1 carriage (112 ORFs) was 14% (Table 3). Thus, some ORFs with low-G+C regions may be specifically regulated by Pmr.

TABLE 3.

Classification of KT2440 chromosomal and pCAR1-borne ORFs by G+C contents of their 500-bp regions upstream of the putative start codon

| % G+C content of 500-bp upstream regions of ORFs | No. (%) of ORFs affected by: |

No. (%) of total ORFs |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pCAR1 carriage |

pmr disruption |

|||||

| pCAR1 | KT2440 chromosome | pCAR1 | KT2440 chromosome | pCAR1 | KT2440 chromosome | |

| >61.6 | NDa | 45 (40) | 1 (3) | 67 (42) | 25 (14) | 2,444 (45) |

| <61.6 | ND | 67 (60) | 30 (97) | 92 (58) | 167 (87) | 2,954 (55) |

| <56.3 | ND | 16 (14) | 27 (87) | 37 (23) | 122 (64) | 935 (17) |

| Total | ND | 112 | 31 | 159 | 192 | 5,398 |

ND, not determined.

Downregulated genes on pCAR1 with pmr disruption.

The transcription levels of the genes on the car operon, involved in carbazole degradation, were downregulated (Fig. 4A; see also Table S2 in the supplemental material). When KT2440(pCAR1) is grown with succinate, the car operon is constitutively transcribed from the PcarAa promoter (26, 35), and it is induced by anthranilate, an intermediate of the carbazole degradation pathway, from the Pant promoter, further upstream (42). Thus, the constitutively expressed carbazole-degrading enzymes will be required to produce anthranilate. This suggests that the downregulation of the constitutive transcription levels of car genes may have caused the growth delay with carbazole. In fact, the growth rate of KT2440(pCAR1Δpmr) was delayed compared with that of KT2440(pCAR1) in NMM-4 buffer with carbazole as a sole carbon source (data not shown). The transcriptional levels of the parAB genes were also reduced in the pmr disruptants (Fig. 4B; see also Table S2). The parAB genes are required for the stable maintenance of pCAR1 in the host strain (36), and thus, the downregulation of these genes may cause instability of pCAR1. However, we did not detect changes in the stability of pCAR1 or pCAR1Δpmr in KT2440 cells (data not shown), suggesting that the effects of the downregulation of the parAB genes on plasmid stability may be insignificant. It is also possible that the chromosomally encoded ParAB system (ParABKT2440) for the partition of the KT2440 chromosome may have been involved in plasmid partition; however, the transcriptional levels of these genes were unaltered in the pmr disruptant (data not shown). Additionally, the cis-acting centromere-like parS sequence is indispensable for the function of ParABKT2440; however, the 16-nucleotide (nt) parS sequence of P. putida KT2440 (5′-TGTTNCACGTGAAACA-3′) (3, 18) was not found in the pCAR1 sequence (data not shown). The reason pCAR1Δpmr was stable in the host strain was not clear. Notably, the transcriptional levels of the car and parAB genes were altered in different host strains (26, 35), and the transcription of these genes may be related to the Pmr concentration.

FIG. 4.

RNA maps of downregulated genes on pCAR1 by pmr disruption of the flanking regions of the car operon (A) or parAB genes (B). The x axis indicates the position in pCAR1, and the y axis indicates the signal intensities of hybridization with single-stranded cDNA. Each bar denotes the signal intensity of each probe: red bars represent RNA maps of pCAR1-containing KT2440, and green bars represent those of the pmr disruptants. The results of two biological replicates (Replicate-1 and -2) are shown. Pentagons indicate the directions and locations of the annotated genes.

pmr disruption alters chromosomal gene transcription that is upregulated by pCAR1 carriage.

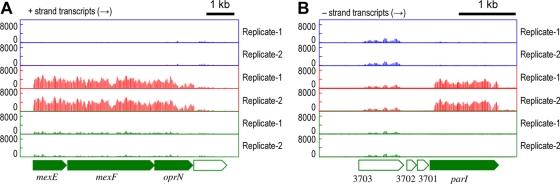

The mexEF-oprN operon, encoding the efflux pump, was upregulated in KT2440(pCAR1) and downregulated in KT2440(pCAR1Δpmr) (Fig. 5 A; see also group E of Table S4 in the supplemental material). In our previous study, these gene products enhanced the chloramphenicol (Cm) resistance of the host strain; KT2440(pCAR1) showed resistance to concentrations of Cm higher than 300 μg/ml, although KT2440 was not able to grow with that concentration. (35). Therefore, we assessed the Cm resistance (300 μg/ml) of the pmr disruptants. Cm resistance reverted to the levels of pCAR1-free KT2440, indicating that the downregulation of the mexEF-oprN operon may occur with the loss of resistance at that concentration. Westfall et al. (45) reported that the transcription of mexEF-oprN orthologous genes in P. aeruginosa PAO1 (normally untranscribed) was induced in the mvaT (PA4315) mutant on the PAO1 chromosome. Thus, H-NS family proteins may be involved in the transcriptional regulation of these genes in PAO1. Although our case contrasted with the PAO1 case, i.e., pmr disruption caused the downregulation of the mexEF-oprN operon, Pmr may have contributed to the transcriptional regulation of these genes. Herrera et al. (19) recently reported that PhhR (PP_4489), a transcriptional regulator of phenylalanine hydroxylase phhAB genes, modulates the level of expression of mexEF-oprN together with MexT (PP_2826). Notably, the transcriptional levels of both phhR and mexT were not changed by pCAR1 carriage or by pmr disruption (data not shown), suggesting that Pmr may be the third element for the regulation of the mexEF-oprN operon.

FIG. 5.

RNA maps of the flanking regions of the mexEF-oprN (A) or parI (B) gene on the KT2440 chromosome. Blue, red, and green bars represent the signal intensities of each probe detected in the RNA maps of KT2440, KT2440(pCAR1), and KT2440(pCAR1Δpmr) with the two biological replicates (Replicate-1 and -2), respectively. Pentagons indicate the directions and locations of annotated genes.

The parI gene encodes a putative ParA-like ATPase containing an N-terminal DNA-binding motif, and its transcription was upregulated in KT2440(pCAR1) but downregulated in KT2440(pCAR1Δpmr) (Fig. 5B; see also group E of Table S4 in the supplemental material). This corroborated our previous results that the parI promoter was activated in the presence of pCAR1 because of the parA product from pCAR1 (25). Therefore, the decrease in the parI transcriptional level in KT2440(pCAR1Δpmr) was caused by the reduced parA transcription (Fig. 4B; see also Table S2), although the reasons for the parA gene downregulation in KT2440(pCAR1Δpmr) remain unclear.

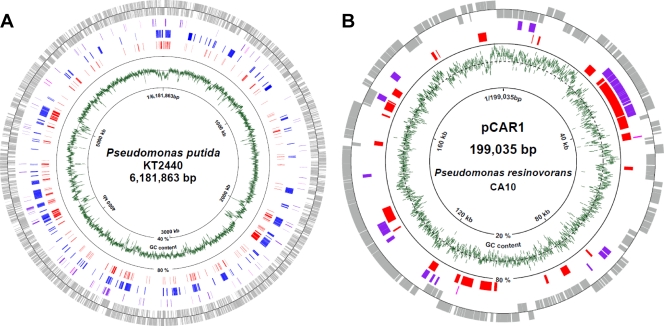

Pmr preferentially binds to foreign DNA and low-G+C regions of the host chromosome.

Because the transcription of many genes was affected by pCAR1 carriage and by pmr disruption, we identified genome-wide Pmr-binding DNA regions on both pCAR1 and the KT2440 chromosome. We performed ChAP-chip analyses to identify the Pmr-binding sites on the KT2440 chromosome and in pCAR1 in early log phase growing cells, as well as transcriptome analyses, although the translational levels of Pmr were higher in the late log and stationary growth phases than in early log phase growth (Fig. 1D).

Consequently, 241 and 26 Pmr-binding sites were detected (with a P value of <0.01) on the KT2440 chromosome and in pCAR1, respectively (see Table S5 in the supplemental material). First, we calculated the G+C content of the regions identified. The average G+C content of the 241 Pmr-binding regions in the KT2440 chromosome was significantly lower (52.5%) than that of the entire KT2440 chromosome (61.6%). The 26 Pmr-binding regions in pCAR1 also demonstrated an average G+C content (52.5%) that was lower than that of the entire pCAR1 plasmid (56.3%). Indeed, a high association was found between the Pmr-binding sites on the KT2440 chromosome and the putative foreign DNA region (Fig. 6A). Notably, 73% of the Pmr-binding sites in the KT2440 chromosome were located in foreign DNA regions.

FIG. 6.

Distribution of Pmr-binding sites on the P. putida KT2440 chromosome (A) or pCAR1 (B). Genes or ORFs (gray) outside the circle are coded clockwise, while those inside are coded counterclockwise. Genes upregulated or downregulated by pmr disruption are shown in purple and magenta, respectively. Putative horizontally acquired DNA regions in the KT2440 chromosome (24) are shown in blue. The Pmr-binding regions detected in this study are shown in red. The green line indicates the average G+C content of genomic DNA (KT2440, 1,000-nt span; pCAR1, 100-nt span). The broken-line circle indicates the average G+C content of the entire KT2440 (61.6%) or pCAR1 (56.3%) genome.

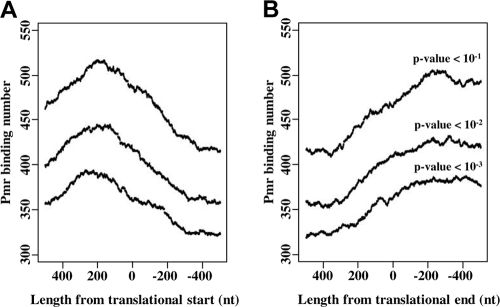

Interestingly, many Pmr binding sites in pCAR1 overlapped with the localization of the differentially transcribed genes with pmr disruption (Fig. 6B). Similarly, many binding sites in the KT2440 chromosome were also found near regions where the differentially transcribed genes localized, although not every gene near a binding-site region was affected by pmr disruption (Fig. 6A). These data indicate that Pmr regulates the transcription of many genes by binding to intergenic or intragenic regions of target genes. To determine the relative positions of the Pmr-binding sites to each intergenic or intragenic region of the ORFs, distribution analyses were performed for the ChAP-chip analysis data (Fig. 7). The Pmr binding site number peaked at around 200 bp upstream from the translational start point and at around 300 bp downstream from the translational endpoint (Fig. 7), which was similar in the ChAP-chip analysis when different P-value thresholds were used (Fig. 7). This analysis indicated that Pmr may bind preferentially to intergenic regions rather than to intragenic regions of ORFs, confirming many reports that H-NS family proteins regulate gene expression by binding to target promoter regions (10, 16).

FIG. 7.

Distribution of Pmr-binding regions near the translation start (A) or end (B) points. Pmr-binding regions located 500 bp upstream and downstream of the translation start (or end) points were plotted. Pmr-binding numbers (y axis) were estimated for each nucleotide position in the range from 500 bp up- and downstream of the translation start (end) points by vertical integration of the binding regions around the translation start (end) points.

Our ChAP-chip analysis demonstrated that Pmr bound preferentially to DNA with a low G+C content in KT2440(pCAR1) and that Pmr bound to intergenic regions and regulated the transcription of genes in the flanking regions of the binding sites.

We also performed ChAP-chip analysis to identify the binding sites of the TurA and TurB proteins, which are encoded on the KT2440 chromosome. However, the detected TurA- and TurB-binding sites were almost identical to those of Pmr, and most of them were DNA regions with low G+C content (data not shown). These results were similar to those observed with E. coli or P. aeruginosa PAO1, in which the two H-NS family proteins (H-NS and StpA or MvaT and MvaU) bound to the same regions of the chromosome (5, 43). Recently Dillon et al. (8) reported that the DNA binding sites of plasmid-encoded Sfh of Salmonella overlapped with those of H-NS. Sfh does not bind uniquely to any site, and the number of binding sites in Sfh is smaller than that in H-NS. Although Sfh binding sites are located within H-NS, the DNA binding sites greatly expand in the absence of H-NS, suggesting that Sfh may play a “backup” role for H-NS (8). These facts suggest that the three proteins Pmr, TurA, and TurB may function coordinately as global regulators in the cells and that Pmr may also perform “backup” functions for the other proteins, different from those of H-NS and Sfh, because the binding sites of Pmr, TurA, and TurB are identical. However, previous genome-wide analyses of the binding sites of H-NS family proteins, including ours, did not necessarily take into account the in vivo protein-protein interaction(s). In other words, the detected sites are not necessarily showing how they bind to the DNA sequences by forming the homo- or heteromultimer of the H-NS family proteins in vivo. Considering the coordinate functions for DNA binding and transcriptional regulation by Pmr and TurA to TurE, analyses from protein structure viewpoints will be necessary to understand how they compose the homo- or heteromultimer in vivo in the presence or absence of target DNA.

Conclusions.

In this study, we demonstrated that the plasmid-encoded H-NS family protein Pmr forms homomeric and heteromeric oligomers in vitro and that pmr, turA, and turB are the primary transcribed genes at different growth phases. We also revealed that pmr disruption affected the carbon catabolism of KT2440(pCAR1) and that Pmr is a key factor that regulates the transcription of genes on both pCAR1 and the host chromosome in two ways: (i) Pmr may alter the transcriptional levels of genes in group E or F, such as mexEF-oprN and parI, and (ii) Pmr may minimize the effect of the transcription of many genes in group G or H, such as those in the putative foreign DNA regions. The identification of genome-wide binding sites in Pmr by ChAP-chip analysis indicated that Pmr binds to putative foreign DNA regions with low G+C content. Additionally, Pmr binds preferentially to intergenic regions and may regulate many genes in the flanking regions of the binding sites. These findings indicate that Pmr is involved in the regulation of the expression of many genes, directly or indirectly, and that this regulation may be closely related to its DNA-binding regions and its interaction with other H-NS family proteins, primarily TurA and TurB. Recently three H-NS family proteins in pathogenic E. coli, the endogenous hns and stpA genes and the horizontally acquired hfp gene, were shown to be differentially transcribed at distinct temperatures (27). Thus, we must further analyze the transcriptional and translational levels of Pmr, TurA, TurB, TurC, TurD, and TurE under conditions other than those we have used to date.

Notably, the pmr gene is conserved in another IncP-7 plasmid, pWW53 (46), indicating that Pmr is an important protein for IncP-7 plasmids. Moreover, H-NS family proteins are expressed from other plasmids, such as H-NS from R27 (IncHI) (17), Sfh from pSf-R27 (IncHI) (15), Orf4 from R446 (IncM) (41), or an undeposited ORF from pQBR103 (IncP-3) (40). A key function of H-NS expressed from mobile genetic elements is maintaining host cell fitness (15). H-NS is a member of the NAP family, and its coordinate functions with other NAPs are also important for host cell fitness maintenance (9, 11). In the case of the R27 studies, the Hha-like protein, a protein-protein modulator of H-NS activity, is encoded on the plasmid (17); however, no candidates for Pmr modulator-encoding genes are found on pCAR1. Interestingly, pCAR1 harbors two other genes encoding putative NAPs other than Pmr, although their transcriptional levels were unaltered by pmr disruption. Analyses of the function(s) of these gene products are necessary to understand how these H-NS family proteins behave when pCAR1 is introduced into the host cell by conjugative transfer. Such information would help to explain the adaptive and evolutionary mechanisms of bacteria acquiring foreign genes by horizontal gene transfer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Akira Yokota of the Institute of Molecular and Cellular Biosciences, the University of Tokyo, for use of his Biolog MicroLog MicroStation system.

This study was supported by the Program for Promotion of Basic Research Activities for Innovative Biosciences (PROBRAIN) in Japan. Y.T. was supported by research fellowships from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) for Young Scientists.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 July 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.). 1990. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY.

- 2.Bagdasarian, M., R. Lurz, B. Ruckert, F. C. H. Franklin, M. M. Bagdasarian, J. Frey, and K. N. Timmis. 1981. Specific-purpose plasmid cloning vectors. II. Broad host range, high copy number, RSF1010-derived vectors, and a host-vector system for gene cloning in Pseudomonas. Gene 16:237-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartosik, A. A., K. Lasocki, J. Mierzejewska, C. M. Thomas, and G. Jagura-Burdzy. 2004. ParB of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: interactions with its partner ParA and its target parS and specific effects on bacterial growth. J. Bacteriol. 186:6983-6998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bochner, B. R. 2009. Global phenotypic characterization of bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33:191-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castang, S., H. R. McManus, K. H. Turner, and S. L. Dove. 2008. H-NS family members function coordinately in an opportunistic pathogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:18947-18952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi, K. H., and H. P. Schweizer. 2005. An improved method for rapid generation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa deletion mutants. BMC Microbiol. 23:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deighan, P., C. Beloin, and C. J. Dorman. 2003. Three-way interactions among the Sfh, StpA and H-NS nucleoid-structuring proteins of Shigella flexneri 2a strain 2457T. Mol. Microbiol. 48:1401-1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dillon, S. C., A. D. Cameron, K. Hokamp, S. Lucchini, J. C. Hinton, and C. J. Dorman. 2010. Genome-wide analysis of the H-NS and Sfh regulatory networks in Salmonella Typhimurium identifies a plasmid-encoded transcription silencing mechanism. Mol. Microbiol. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07173.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Dillon, S. C., and C. J. Dorman. 2010. Bacterial nucleoid-associated proteins, nucleoid structure and gene expression. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8:185-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorman, C. J. 2004. H-NS: a universal regulator for a dynamic genome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:391-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorman, C. J. 2009. Nucleoid-associated proteins and bacterial physiology. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 67:47-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dorman, C. J. 2010. Horizontally acquired homologues of the nucleoid-associated protein H-NS: implications for gene regulation. Mol. Microbiol. 75:264-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dorman, C. J., and K. A. Kane. 2008. DNA bridging and antibridging: a role for bacterial nucleoid-associated proteins in regulating the expression of laterally acquired genes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33:587-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doyle, M., and C. J. Dorman. 2006. Reciprocal transcriptional and posttranscriptional growth-phase dependent expression of sfh, a gene that encodes a paralogue of the nucleoid-associated protein H-NS. J. Bacteriol. 188:7581-7591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doyle, M., M. Fookes, A. Ivens, M. W. Mangan, J. Wain, and C. J. Dorman. 2007. An H-NS-like stealth protein aids horizontal DNA transmission in bacteria. Science 315:251-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fang, F. C., and S. Rimsky. 2008. New insights into transcriptional regulation by H-NS. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11:113-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forns, N., R. C. Baños, C. Balsalobre, A. Juárez, and C. Madrid. 2005. Temperature-dependent conjugative transfer of R27: role of chromosome- and plasmid-encoded Hha and H-NS proteins. J. Bacteriol. 187:3950-3959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Godfrin-Estevenon, A. M., F. Pasta, and D. Lane. 2002. The parAB gene products of Pseudomonas putida exhibit partition activity in both P. putida and Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 43:39-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herrera, M. C., E. Duque, J. J. Rodríguez-Herva, A. M. Fernández-Escamilla, and J. L. Ramos. 2010. Identification and characterization of the PhhR regulon in Pseudomonas putida. Environ. Microbiol. 12:1427-1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoang, T. T., R. R. Karkhoff-Schweizer, A. J. Kutchma, and H. P. Schweizer. 1998. A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally-located DNA sequences: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. Gene 212:77-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jain, S., and D. E. Ohman. 1998. Deletion of algK in mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa blocks alginate polymer formation and results in uronic acid secretion. J. Bacteriol. 180:634-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johansson, J., S. Eriksson, B. Sondén, S. N. Wai, and B. E. Uhlin. 2001. Heteromeric interactions among nucleoid-associated bacterial proteins: localization of StpA-stabilizing regions in H-NS of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:2343-2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maeda, K., H. Nojiri, M. Shintani, T. Yoshida, H. Habe, and T. Omori. 2003. Complete nucleotide sequence of carbazole/dioxin-degrading plasmid pCAR1 in Pseudomonas resinovorans strain CA10 indicates its mosaicity and the presence of large catabolic transposon Tn4676. J. Mol. Biol. 326:21-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martins dos Santos, V. A. P., K. N. Timmis, B. Tümmler, and C. Weinel. 2004. Genomic features of Pseudomonas putida strain KT2440, p. 77-112. In J. L. Ramos (ed.), Pseudomonas, vol. 1. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyakoshi, M., M. Shintani, T. Terabayashi, S. Kai, H. Yamane, and H. Nojiri. 2007. Transcriptome analysis of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 harboring the completely sequenced IncP-7 plasmid pCAR1. J. Bacteriol. 189:6849-6860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyakoshi, M., H. Nishida, M. Shintani, H. Yamane, and H. Nojiri. 2009. High-resolution mapping of plasmid transcriptomes in different host bacteria. BMC Genomics 10:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Müller, C. M., G. Schneider, U. Dobrindt, L. Emödy, J. Hacker, and B. E. Uhlin. 2010. Differential effects and interactions of endogenous and horizontally acquired H-NS-like proteins in pathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 75:280-293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Navarre, W. W., S. Porwollik, Y. Wang, M. McClelland, H. Rosen, S. J. Libby, and F. C. Fang. 2006. Selective silencing of foreign DNA with low GC content by the H-NS protein in Salmonella. Science 313:236-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pinyakong, O., H. Habe, A. Kouzuma, H. Nojiri, H. Yamane, and T. Omori. 2004. Isolation and characterization of genes encoding polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon dioxygenase from acenaphthene and acenaphthylene degrading Sphingomonas sp. strain A4. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 238:297-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Renzi, F., E. Rescalli, E. Galli, and G. Bertoni. 2010. Identification of genes regulated by the MvaT-like paralogues TurA and TurB of Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Environ. Microbiol. 12:254-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rescalli, E., S. Saini, C. Bartocci, L. Rychlewski, V. De Lorenzo, and G. Bertoni. 2004. Novel physiological modulation of the Pu promoter of TOL plasmid: negative regulatory role of the TurA protein of Pseudomonas putida in the response to suboptimal growth temperatures. J. Biol. Chem. 279:7777-7784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 33.Schäfer, A., A. Tauch, W. Jäger, J. Kalinowski, G. Thierbach, and A. Pühler. 1994. Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145:69-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schägger, H. 2006. Tricine-SDS-PAGE. Nat. Protoc. 1:16-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shintani, M., Y. Takahashi, H. Tokumaru, K. Kadota, H. Hara, M. Miyakoshi, K. Naito, H. Yamane, H. Nishida, and H. Nojiri. 2010. Response of the Pseudomonas host chromosomal transcriptome to carriage of the IncP-7 plasmid pCAR1. Environ. Microbiol. 12:1413-1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shintani, M., H. Yano, H. Habe, T. Omori, H. Yamane, M. Tsuda, and H. Nojiri. 2006. Characterization of the replication, maintenance, and transfer features of the IncP-7 plasmid pCAR1, which carries genes involved in carbazole and dioxin degradation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:3206-3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shintani, M., T. Yoshida, H. Habe, T. Omori, and H. Nojiri. 2005. Large plasmid pCAR2 and class II transposon Tn4676 are functional mobile genetic elements to distribute the carbazole/dioxin-degradative car gene cluster in different bacteria. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 67:370-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takahashi, Y., M. Shintani, H. Yamane, and H. Nojiri. 2009. The complete nucleotide sequence of pCAR2: pCAR2 and pCAR1 were structurally identical IncP-7 carbazole degradative plasmids. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 73:744-746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tendeng, C., O. A. Soutourina, A. Danchin, and P. N. Bertin. 2003. MvaT proteins in Pseudomonas spp.: a novel class of H-NS-like proteins. Microbiology 149:3047-3050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tett, A., A. J. Spiers, L. C. Crossman, D. Ager, L. Ciric, J. M. Dow, J. C. Fry, D. Harris, A. Lilley, A. Oliver, J. Parkhill, M. A. Quail, P. B. Rainey, N. J. Saunders, K. Seeger, L. A. Snyder, R. Squares, C. M. Thomas, S. L. Turner, X. X. Zhang, D. Field, and M. J. Bailey. 2007. Sequence-based analysis of pQBR103; a representative of a unique, transfer-proficient mega plasmid resident in the microbial community of sugar beet. ISME J. 1:331-340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tietze, E., and H. Tschäpe. 1994. Temperature-dependent expression of conjugation pili by IncM plasmid-harbouring bacteria: identification of plasmid-encoded regulatory functions. J. Basic Microbiol. 34:105-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Urata, M., M. Miyakoshi, S. Kai, K. Maeda, H. Habe, T. Omori, H. Yamane, and H. Nojiri. 2004. Transcriptional regulation of the ant operon, encoding two-component anthranilate 1,2-dioxygenase, on the carbazole-degradative plasmid pCAR1 of Pseudomonas resinovorans strain CA10. J. Bacteriol. 186:6815-6823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Uyar, E., K. Kurokawa, M. Yoshimura, S. Ishikawa, N. Ogasawara, and T. Oshima. 2009. Differential binding profiles of StpA in wild-type and h-ns mutant cells: a comparative analysis of cooperative partners by chromatin immunoprecipitation-microarray analysis. J. Bacteriol. 191:2388-2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vallet-Gely, I., K. E. Donovan, R. Fang, J. K. Joung, and S. L. Dove. 2005. Repression of phase-variable cup gene expression by H-NS-like proteins in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:11082-11087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Westfall, L. W., N. L. Carty, N. Layland, P. Kuan, J. A. Colmer-Hamood, and A. N. Hamood. 2006. mvaT mutation modifies the expression of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa multidrug efflux operon mexEF-oprN. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 255:247-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yano, H., C. E. Garruto, M. Sota, Y. Ohtsumo, Y. Nagata, G. Zylstra, P. A. Williams, and M. Tsuda. 2007. Complete sequence determination combined with analysis of transposition /site-specific recombination events to explain genetic organization of IncP-7 TOL plasmid pWW53 and related mobile genetic elements. J. Mol. Biol. 369:11-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoshida, T., Y. Ayabe, M. Yasunaga, Y. Usami, H. Habe, H. Nojiri, and T. Omori. 2003. Genes involved in the synthesis of the exopolysaccharide methanolan by the obligate methylotroph Methylobacillus sp. strain 12S. Microbiology 149:431-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yuste, L., A. B. Hervás, I. Canosa, R. Tobes, J. L. Jiménez, J. Nogales, M. M. Pérez-Pérez, E. Santero, E. Díaz, J. L. Ramos, V. De Lorenzo, and F. Rojo. 2006. Growth phase-dependent expression of the Pseudomonas putida KT2440 transcriptional machinery analysed with a genome-wide DNA microarray. Environ. Microbiol. 8:165-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.