Abstract

Haemophilus ducreyi, the etiological agent of chancroid, has a strict requirement for heme, which it acquires from its only natural host, humans. Previously, we showed that a vaccine preparation containing the native hemoglobin receptor HgbA purified from H. ducreyi class I strain 35000HP (nHgbAI) and administered with Freund's adjuvant provided complete protection against a homologous challenge. In the current study, we investigated whether nHgbAI dispensed with monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL), an adjuvant approved for use in humans, offered protection against a challenge with H. ducreyi strain 35000HP expressing either class I or class II HgbA (35000HPhgbAI and 35000HPhgbAII, respectively). Pigs immunized with the nHgbAI/MPL vaccine were protected against a challenge from homologous H. ducreyi strain 35000HPhgbAI but not heterologous strain 35000HPhgbAII, as evidenced by the isolation of only strain 35000HPhgbAII from nHgbAI-immunized pigs. Furthermore, histological analysis of the lesions showed striking differences between mock-immunized and nHgbAI-immunized animals challenged with strains 35000HPhgbAI but not those challenged with strain 35000HPhgbAII. Mock-immunized pigs were not protected from a challenge by either strain. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) activity of the nHgbAI/MPL antiserum was lower than the activity of antiserum from animals immunized with the nHgbAI/Freund's vaccine; however, anti-nHgbAI from both studies bound whole cells of 35000HPhgbAI better than 35000HPhgbAII and partially blocked hemoglobin binding to nHgbAI. In conclusion, despite eliciting lower antibody ELISA activity than the nHgbAI/Freund's, the nHgbAI/MPL vaccine provided protection against a challenge with homologous but not heterologous H. ducreyi, suggesting that a bivalent HgbA vaccine may be needed.

Chancroid is one of the genital ulcer diseases and is transmitted through sexual contact. Lesions caused by chancroid initially appear as papules, which evolve within several days into pustules. If left untreated, chancroid pustules develop into painful, bleeding ulcers with soft, irregular borders. Chancroid is prevalent in certain developing countries but is rarely found in the United States (47, 62). Several studies have shown that chancroid serves as an important independent cofactor in the heterosexual transmission of HIV where both diseases are endemic (29, 35, 48, 51, 66). Commercial sex workers serve as the reservoir of chancroid, and control of disease in this population strikingly reduces the number of cases of chancroid in their male clients (58). Thus, one possible approach to control chancroid is to implement a limited vaccination program to control infection in this reservoir; however, no vaccine for chancroid currently exists.

Haemophilus ducreyi, the etiologic agent of chancroid, is a fastidious Gram-negative bacterium and a strict human pathogen. An interesting biologic feature of H. ducreyi is its obligate requirement for heme. Heme (for H. ducreyi) and iron are critical nutrients required for most pathogenic bacteria. Many Gram-negative bacteria obtain heme/Fe through systems that include TonB-dependent outer membrane receptors specific for heme/Fe compounds. The relatively small genome of prototypical H. ducreyi strain 35000HP encodes only three TonB-dependent receptors; in comparison, other bacterial genomes can encode more than 30 (14). Using isogenic mutants, the Spinola and Elkins laboratories surveyed the ability of H. ducreyi TonB-dependent receptor mutants to initiate infection in the human experimental model of chancroid. An H. ducreyi mutant that does not express the gene encoding the hemoglobin (Hb) receptor, hgbA, did not establish human infection (3). In contrast, an isogenic double mutant lacking the genes encoding the two other TonB-dependent receptors of H. ducreyi, tdhA and tdX, was fully virulent, indicating that HgbA is the only TonB-dependent receptor of H. ducreyi to be a virulence factor in the human experimental model of chancroid (38). Since HgbA is required for the utilization of heme from Hb by H. ducreyi (17), these data suggest that Hb is the most important source of heme in the early stages of the human experimental model of chancroid and that HgbA is a potential vaccine candidate.

HgbA is a large, 100-kDa outer membrane protein that has a complex structure similar to that of other TonB-dependent receptors whose structure has been solved (10, 12, 20, 21, 40). HgbA is believed to contain 22 transmembrane beta sheets and 11 putatively surface-exposed loops. A recent study in our laboratory using H. ducreyi mutants expressing single loop deletions in HgbA provided evidence for surface exposure of loops 4, 5, 6, and 7 (44). Moreover, deletions of loops 5 and 7 but not of the other 9 loops of HgbA abrogated the binding of human Hb to HgbA. We also found that IgG from pigs immunized with native HgbA (nHgbA) bound loops 4, 5, and 7 and that antibodies directed at loops 4 and 5 partially blocked Hb binding to HgbA in vitro. Thus, a central domain of the primary sequence of HgbA is immunogenic, required for binding Hb, and surface exposed.

H. ducreyi strains exist in two groups, designated class I and class II, based on striking primary sequence differences in certain outer membrane proteins, such as DsrA (ducreyi serum resistance A) and NcaA (necessary for collagen adhesion A), and on their lipooligosaccharide (LOS) structures (49, 50, 53, 67). In contrast, the HgbA proteins of different classes of H. ducreyi strains are more than 95% identical. Prototypical H. ducreyi strain 35000HP, a class I isolate, is the strain used for most studies, including isogenic mutant construction and the experimental human model of chancroid. 35000HP is the only H. ducreyi strain whose genome has been sequenced.

Previously, we showed that immunization of swine with native HgbA from class I strain 35000HP (nHgbAI) in Freund's adjuvant provided complete protection from a homologous challenge infection with H. ducreyi strain 35000HP (1). The antibodies elicited by nHgbAI/Freund's showed modest bactericidal activity, bound to the cell surface of both class I and class II H. ducreyi strains, and partially blocked Hb binding to nHgbA (1). nHgbAI antisera did not recognize the surface of, nor did they show bactericidal activity against the isogenic hgbA mutant, demonstrating specificity of the humoral response to HgbA.

In the current study, we pursued two objectives. First, we investigated the effectiveness of monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL), an adjuvant approved for use in humans, to elicit an immune response to the nHgbAI vaccine that is protective against an H. ducreyi challenge in the experimental swine model of chancroid. Second, we examined the ability of this vaccine to protect swine from a challenge infection with H. ducreyi strain 35000HP expressing either class I hgbA (hgbAI) or class II hgbA (hgbAII) from H. ducreyi strain DMC111 (homologous versus heterologous challenge, respectively).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

H. ducreyi strain 35000HP (human-passaged variant, class I strain) (4, 25) used in this study was obtained from Stanley Spinola, Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN. H. ducreyi class II strain DMC111 is an isolate from Bangladesh (67). The construction of isogenic hgbAI mutant H. ducreyi strain FX547 was previously described (44). FX547 contains a complete deletion of the hgbAI open reading frame, replaced with a chloramphenicol resistance cassette insert, and cannot grow on Hb plates (100 μg/ml) as a sole source of heme (44). For routine growth, H. ducreyi strains were maintained on chocolate agar plates containing gonococcal medium base (GCB; Difco, Detroit, MI) and 1% bovine Hb (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) and supplemented with 1% GGC (0.1% glucose, 0.001% glutamine, 0.026% cysteine) and 5% Fetalplex (Gemini Bio-Products, West Sacramento, CA). Cultures were incubated at 34.5°C with 5% CO2.

Construction of H. ducreyi strain 35000HP expressing the hgbAII gene from strain DMC111.

A class I H. ducreyi strain expressing the class II hgbA gene (hgbAII), 35000HPhgbAII, was constructed in the following fashion: PCR was used to amplify hgbAII from H. ducreyi strain DMC111 using class II-specific hgbA primers that contain restriction sites (underlined) (5′-TAACACTTAAGGAATACGTAATGAAAACGAATAAACTC-3′ and 5′-GAGAAATCATATGACAAAAAAGGGCACCGAAGT-3′) and cloned into the AflII and NdeI sites of pUNCH1411 (44) to create pUNCH1413. pUNCH1413 contains the open reading frame of class II hgbA with class I hgbA flanking sequences. pUNCH1413 DNA was digested with EcoRI and XhoI, and the hgbA fragment isolated. This DNA fragment was electroporated into H. ducreyi FX547, and cells plated on Hb agar plates. Transformants that grew on Hb as a sole source of heme were screened for the expression of HgbA by Western blotting. A single colony was chosen, isolated, and sequenced. Two mutations were detected during sequencing. The first mutation was silent and the second mutation changed amino acid 21 of the mature protein from valine to glutamic acid. This change is in the “plug” region of mature HgbA and is thought not to be surface exposed. The HgbAII protein functions normally for growth on medium with Hb as the sole heme source in 35000HP, and H. ducreyi strain 35000HPhgbAII is fully virulent in the swine model. For the purpose of this report, wild-type H. ducreyi strain 35000HP will be referred to as 35000HPhgbAI. To ensure that HgbAII was expressed at the same level as HgbAI in the 35000HP background, outer membrane proteins were prepared from low-heme liquid cultures of strains 35000hgbAI, 35000HPhgbAII, and the hgbA isogenic null mutant 35000HPΔhgbA and subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie staining. HgbAII is expressed at a level similar to that of HgbAI in the 35000HP background in both whole cells and outer membrane protein preparations (data not shown).

HgbA purification.

Purification of nHgbAI and nHgbAII from H. ducreyi strains 35000HPhgbAI and 35000HPhgbAII was performed as previously described (1). The purity of both nHgbAI and nHgbAII was greater than 95% (data not shown).

Animals.

Eight Yorkshire Cross pigs were used in two separate immunization experiments (four pigs per experiment). Pigs were obtained at 3 weeks of age and housed at ambient temperature (20° to 25°C) in individual pens at the North Carolina State University (NCSU) School of Veterinary Medicine. Pigs were given water and antibiotic-free high-protein feed ad libitum starting 6 weeks prior to the start of and continuing throughout the study. During inoculation and biopsy procedures, pigs were sedated with 2 mg of ketamine HCl (Fort Dodge Laboratories, Fort Dodge, IA) and 2 mg of xylazine (Miles Laboratories, Shawnee Mission, KS) per kg of body weight, injected intramuscularly. Pigs at challenge generally weighed between 70 and 100 lbs. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at NCSU approved the use of animals for these experiments.

Immunization protocol.

The immunization protocol used in this study was exactly replicated from the original nHgbAI vaccine trial so that the results from the current study would be directly comparable to the one from the previous study (1). In each of 2 experiments, 2 pigs were mock immunized with buffer (1% octylglucoside [Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA] in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) and adjuvant alone and 2 pigs received nHgbAI in buffer and adjuvant. The MPL adjuvant (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions. The immunogen was prepared by mixing 250 μg of nHgbAI in 500 μl PBS containing 1% octylglucoside with 500 μl of MPL adjuvant. Each pig received three intramuscular injections in the nuchal region in two sites 21 days apart. Pigs were bled prior to each of the three immunizations, as well as before challenge and biopsies. Pigs were euthanized immediately following biopsies in accordance with IACUC protocols.

Challenge infection.

Challenge infection was performed 21 days after the third immunization. H. ducreyi strains 35000HPhgbAI and 35000HPhgbAII were grown overnight at 34.5°C and 5% CO2 on chocolate agar plates supplemented with 1% GGC and 5% FetalPlex. For each strain, a cell suspension at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.5 (approximately 1 × 109 CFU/ml) was prepared in GC broth, along with a 1:10 dilution (approximately 1 × 108 CFU/ml). Multi-Test skin test applicators (Lincoln Diagnostics, Decatur, IL) were used to inoculate 10 μl of each bacterial suspension at multiple sites on the pig ears. Since the efficiency of dose delivery by the Multi-Test skin test applicator has been estimated at 1:1,000, 10 μl of a 109 CFU/ml bacterial suspension delivers approximately 104 CFU, and 10 μl of a 108 CFU/ml bacterial suspension delivers an estimated 103 CFU dose (55). Prior to inoculation, the ears of the pigs were cleaned thoroughly with alcohol wipes and lesion sites were marked with an ethanol-resistant pen. Each pig was inoculated with H. ducreyi strain 35000HPhgbAI on the left ear and strain 35000HPhgbAII on the right ear. The viability of bacterial suspensions was determined prior to and after each experiment, and no decrease in CFU was observed.

Biopsy processing.

Pig ear lesions were biopsied 1 week after infection using disposable 6-mm skin biopsy punches (Acuderm, Ft. Lauderdale, FL). Biopsied tissues were either placed in 0.5 ml of GC broth for bacterial recovery or in 0.5 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde for histological studies. In order to recover H. ducreyi from biopsied lesions, tissues were thoroughly minced in GC broth using a sterile scalpel and spread on chocolate agar plates supplemented with 1% GGC, 5% FetalPlex, and 3 μg/ml vancomycin to reduce contaminants (1). Plates were incubated at 34.5°C with 5% CO2 for up to 72 h, the presence/absence of H. ducreyi colonies was noted, and representative colonies were subcultured for confirmatory PCR.

Sections of biopsy specimens preserved in 4% paraformaldehyde were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (Histology Laboratory, College of Veterinary Medicine, North Carolina State University). Each slide was coded and graded blindly by 2 authors according to a previously described protocol (1, 52). The appearance of normal skin received a score of 1; the presence of perivascular and interstitial mononuclear cell infiltrate received a score of 2; the presence of an intraepidermal pustule with neutrophils, fibrin, and necrotic debris received a score of 3; the presence of an epidermal pustule with keratinocyte cytopathology and mononuclear and polymorphonuclear infiltrate received a score of 4; and ulceration or epidermal necrosis and dermal erosion with confluence of immune cells was scored a 5. All slides were viewed using a Leica DM IRB inverted microscope (Leica Microsystems, Bannockburn, IL), and images were saved using QCapture software (QImaging, Surrey, BC, Canada). The scores were compared using Cohen's kappa, which indicated that the similarity between the evaluators (κ = 0.541) was in moderate agreement.

ELISA.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were performed as previously described (1), except that plates were coated with 100 ng/well of nHgbAI instead of 200 ng/well. Each sample was run in duplicate, and the assay was performed on at least 3 different days.

Hb-blocking ELISA.

An ELISA was used to determine the ability of anti-HgbAI to block Hb binding to HgbA (1). One hundred nanograms of nHgbAI or nHgbAII in 0.1 M carbonate buffer (pH 9.5) was added to wells and incubated overnight at 4°C. The next morning, wells were blocked for 1 h with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA)-PBS. Twenty micrograms of anti-nHgbAI IgG was added to wells before a 30-min incubation at room temperature. Digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled human Hb (400 ng in 1% BSA-PBS) was added to wells, and plates were incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Three washes with PBS-0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T) were followed by the addition of alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-DIG antibodies (100 μl, 1:5,000 in PBS) (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). The plates were incubated for 1 h at room temperature and washed thrice with PBS-T. One hundred microliters of alkaline phosphatase substrate (1-Step PNPP [p-nitrophenyl phosphate]) (Pierce, Rockford, IL) was added to wells, and the optical density at 405 nm was measured after 45 min using a 1420 VICTOR2 multilabel counter (Wallac Oy). The Hb was labeled with DIG according to the manufacturer's instructions (DIG protein labeling kit; Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). IgG was purified from pig antisera using protein A/G resin according to the manufacturer's instructions (ExAlpha Biologicals, Watertown, MA).

Whole-cell binding ELISA.

H. ducreyi strains 35000HPhgbAI and 35000HPhgbAII, isogenic hgbAI mutant FX547, and H. ducreyi class II strain DMC111 were grown overnight at 34.5°C with 5% CO2 and shaking for 15 h in GC broth supplemented with 1% GGC and 5% Fetalplex. The whole-cell binding ELISA was performed as previously described (1) with the following changes: two hundred microliters of each strain of H. ducreyi (OD600 = 0.2) was added in triplicate to a Multiscreen HTS 96-well plate (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Fifty microliters of anti-nHgbA antisera was added to wells (final dilution 1:2,000 in 0.25% Tween 20-GC broth) and incubated for 90 min at room temperature with gentle rocking. Wells were washed 4 times with 0.1% Tween 20-GC broth using a vacuum manifold. One hundred microliters of rabbit anti-pig IgG-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (product no. A5670; Sigma, St. Louis, MO), diluted 1:20,000 in 0.25% Tween 20-GC broth, was added to wells, and the plate incubated at room temperature for 60 min with gentle rocking. Wells were washed 4 times with 0.1% Tween 20-GC broth, and 100 μl of HRP substrate (Amersham ECL; GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) was added to wells. Chemiluminescence was detected using the Wallac 1420 VICTOR2 plate reader.

Bactericidal assay.

In order to determine the bactericidal activity of the nHgbAI antisera against H. ducreyi strains, an immune bactericidal assay was performed as previously described (1, 18). Percent killing was determined by dividing the number of colonies that survived in fresh normal human serum (NHS) by the number of colonies that survived in heat-treated NHS and multiplying by 100. There was no decrease in CFU for the heated NHS control compared to the count in the GC broth control.

PCR amplification of loop 4 of the hgbA gene.

To confirm strain identity, H. ducreyi colonies obtained from biopsy specimens were subjected to PCR using primers specific for the conserved flanking regions of loop 4 hgbAI and hgbAII. The upstream and downstream hgbA primers (5′-CTAACCCTTCTGGGCTATAC-3′ and 5′-GCTAGGTAAATACACACGGC-3′, respectively) generated a PCR product of approximately 350 bp from either strain. The PCR steps used for amplification are as follows: an initial 5-min 94°C denaturing step was followed by 30 cycles of 1 min of denaturation at 94°C, annealing for 30 s at 45°C, and extension for 30 s at 72°C. A final polishing step for 5 min at 72°C was used prior to completion. PureTaq Ready-To-Go PCR beads (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) were used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Ten picomoles of PCR primers were used, along with 1 μl of cells (OD600 of 0.2 in 50 μl of water) as template. PCR products were purified using a Qiagen PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and sequenced using the upstream PCR primer at the UNC Genome Analysis Facility.

Whole-cell immunoprecipitation.

H. ducreyi strains were grown overnight in heme-limiting conditions to induce the expression of HgbA at 34.5°C in 50-ml broth cultures of GC broth, 5% Fetalplex, 1% GGC in the presence of 5% CO2 (17). Whole-cell immunoprecipitation was performed as previously described with the following modifications (26, 44, 60): H. ducreyi cultures were centrifuged and the pellets suspended to an OD600 of 1.0 (approximately 5 × 108 CFU/ml) in GC broth. Ten microliters of serum was added to 1 ml of the bacterial suspension and rocked at room temperature for 20 min. Bacterial cells were centrifuged, and the supernatant discarded to remove unbound antibody and serum components. The washed cell pellet was resuspended in 100 μl PBS, and 1 ml of 2% Zwittergent 3-14 (ZW 3-14) (Calbiochem) in TEN buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, pH 8.0) was added to solubilize proteins. After incubation at 37°C with agitation for 1 h, the tube was centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 rpm to remove insoluble debris. The supernatant containing ZW 3-14-soluble total cellular proteins and antigen/antibody complexes was moved to a new tube containing 25 μl of a 50% slurry of protein A/G agarose beads (ExAlpha Biologicals, Shirley, MA). The tubes were incubated for 2 h or overnight to allow binding of antigen/antibody complexes to the protein A/G beads. The tubes were centrifuged and washed thrice using 0.5% ZW 3-14 in TEN. The agarose pellet was then resuspended in 1 ml TEN, moved to a fresh tube, and centrifuged, and the supernatant discarded. Forty microliters of Laemmli sample buffer lacking any reducing agents was added to the washed agarose, the tubes boiled for 5 min at 95°C, and 20 μl of the mixture subjected to SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining.

Western blotting.

Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose, which was blocked in 0.5% Tween 20-PBS for 1 h. Rabbit anti-N-terminal HgbA peptide antiserum diluted at 1:500 was used as the primary antibody (17). The sequence of the peptide used to generate the anti-N-terminal antiserum is identical in both classes of HgbA proteins and should therefore bind HgbAI and HgbAII equally. Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) diluted at 1:20,000 was used as the secondary antibody. Protein bands were visualized using Lumi-Phos (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL).

Statistics.

Statistical analyses were performed using the SigmaStat program (version 3.5; Systat Software, CA). A Mann-Whitney rank sum test was performed for the nonparametric data obtained in the ELISAs and for histology scoring. Fisher's exact test was used to compare bacterial recovery at the animal and lesion levels (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Recovery of H. ducreyi 35000HPhgbAI and 35000HPhgbAII from biopsy specimens

| HgbA class | Expt | Mock immunization |

HgbA immunization |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pig | No. of H. ducreyi-positive specimens/total no. of specimens |

Pig | No. of H. ducreyi-positive specimens/total no. of specimens |

||||

| 104 CFU inoculum | 103 CFU inoculum | 104 CFU inoculum | 103 CFU inoculum | ||||

| I | 1 | 1 | 2/3 | 3/3 | 3 | 0/4 | NDa |

| 2 | 3/3 | 2/3 | 4 | 0/4 | ND | ||

| 2 | 5 | 4/4 | 2/4 | 7 | 0/4 | 0/4 | |

| 6 | 4/4 | 2/4 | 8 | 0/4 | 0/4 | ||

| Total | 13/14b | 9/14d | 0/16b | 0/8d | |||

| II | 1 | 1 | 2/3 | 3/3 | 3 | 3/4 | ND |

| 2 | 3/3 | 2/3 | 4 | 1/4 | ND | ||

| 2 | 5 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 7 | 3/4 | 4/4 | |

| 6 | 1/4 | 1/4 | 8 | 3/4 | 1/4 | ||

| Total | 10/14c | 10/14e | 10/16c | 5/8e | |||

ND, not determined.

P < 0.001, Fisher's exact test.

P = 0.709, Fisher's exact test.

P = 0.006, Fisher's exact test.

P = 1.000, Fisher's exact test.

RESULTS

Construction of H. ducreyi strain 35000HP expressing the hgbA gene from class II strain DMC111.

In preliminary swine challenge experiments using H. ducreyi strains other than 35000HP, all tested strains from either class were less infectious than strain 35000HP (data not shown). Furthermore, H. ducreyi wild-type strain 35000HP grows faster than the class II strains. Therefore, because of these and other phenotypic differences between classes of H. ducreyi strains, we engineered an isogenic 35000HP strain expressing the class II hgbA gene from strain DMC111 (35000HPhgbAII) to determine if the nHgbAI vaccine would be protective against a class II HgbA-expressing strain. In preliminary pig virulence studies, lesions produced by strain 35000HPhgbAII were indistinguishable from lesions caused by the 35000HP parent strain and the HgbAII protein was expressed at the same level as HgbAI in the 35000HP background (data not shown).

The nHgbAI/MPL vaccine reduced lesion severity after a homologous challenge.

Pigs were immunized and challenged as described in Materials and Methods using a protocol identical to that of the previous HgbA vaccine study (1). The following parameters were analyzed: pig ear lesions were examined at both the macroscopic and microscopic levels; recovery of H. ducreyi was determined; and antisera from nHgbAI-immunized animals were subjected to several in vitro immunological assays, including different types of ELISAs, to measure antibody activity to nHgbAI, binding to whole cells of H. ducreyi, and the ability of IgGs from immunized animals to block Hb binding to both nHgbAI and nHgbAII. The bactericidal activity of anti-nHgbAI antisera was measured using a classic bactericidal assay.

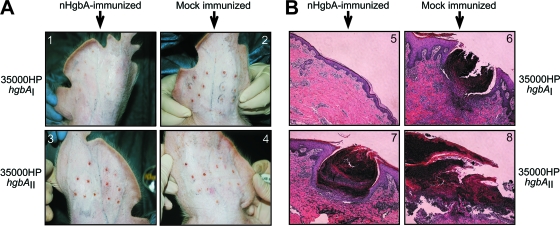

Figure 1A shows representative photographs of lesions from pigs challenged with both strains of H. ducreyi taken immediately prior to biopsy. In animals immunized with nHgbAI, inoculation with homologous strain 35000HPhgbAI produced small lesions (Fig. 1A1), and in some cases, lesions were undetectable, save for puncture wounds from the applicator device. In contrast, infection of mock-immunized animals with both strains of H. ducreyi (Fig. 1A2 and 4) produced raised, visible lesions, much larger than those found in nHgbAI-immunized animals challenged with strain 35000HPhgbAI, indicating that both challenge strains are virulent in the experimental swine model of chancroid. The lesions of nHgbAI-immunized animals challenged with heterologous strain 35000HPhgbAII (Fig. 1A3) appeared similar to those from mock-immunized pigs.

FIG. 1.

nHgbAI/MPL vaccine reduces lesion severity of experimental chancroid at the macroscopic and microscopic levels. (A) Photographs of pig ear lesions. Pigs were either mock immunized with MPL adjuvant only (2 and 4) or immunized with nHgbAI/MPL (1 and 3) and challenged with either H. ducreyi strain 35000HPhgbAI (1 and 2) or 35000HPhgbAII (3 and 4). Photos were taken 1 week after challenge and immediately prior to biopsy. (B) H&E-stained biopsy sections from pig ears 1 week after infection. Pigs were either mock immunized with MPL adjuvant only (6 and 8) or immunized with nHgbAI/MPL (5 and 7) and challenged with either H. ducreyi strain 35000HPhgbAI (5 and 6) or 35000HPhgbAII (7 and 8) (magnification, ×50).

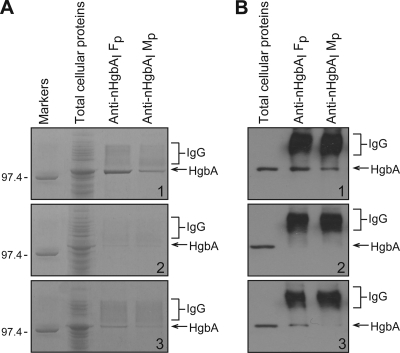

FIG. 4.

nHgbAI/MPL antiserum immunoprecipitates only HgbAI from whole cells of H. ducreyi. The ability of anti-nHgbAI antisera to immunoprecipitate HgbA from different H. ducreyi strains is shown in a Coomassie blue-stained 10% SDS-PAGE gel (A) and a Western blot probed with an antiserum to full-length rHgbAI (19) (B). The H. ducreyi strains used in these immunoprecipitation assays were 35000HPhgbAI (1), 35000HPhgbAII (2), and DMC111 (3). Antisera used in these experiments were either pooled anti-nHgbAI/Freund's (Fp) purified from antisera obtained in a previous study (1) or pooled anti-nHgbAI/MPL (Mp). Molecular size markers are shown in kilodaltons.

Figure 1B shows representative histological sections of lesion biopsy specimens stained with H&E. In nHgbAI-immunized animals challenged with homologous strain 35000HPhgbAI (Fig. 1B5), a low level of inflammatory cell infiltrate was present in the lesions, and the basement membrane was intact, resembling healthy sections (52). In mock-immunized animals challenged with either strain (Fig. 1B6 and 8), there was a dense infiltrate of neutrophils and the epidermal-dermal border was completely destroyed, which left the dermis exposed, similar to previous results (1) and comparable to natural and experimental infection in humans (34, 56). In the nHgbAI-immunized heterologous challenge group (Fig. 1B7), the lesions appeared to be similar to those of mock-immunized animals.

We used a previously described grading system based on a 1-to-5 range (for lesion scores, see Materials and Methods) to judge the severity of lesions in each group of animals (52). The mean lesion grade of mock-immunized animals challenged with the homologous strain was 4.0 ± 0.76, whereas the nHgbAI-immunized group challenged with the same strain had a score of 2.6 ± 0.78 (P = 0.002). The mean lesion grade for the control group challenged with the heterologous strain was 4.1 ± 1.3, compared to a score of 3.7 ± 1.3 for nHgbAI-immunized animals (P = 0.442).

Viable H. ducreyi cells were not recovered from lesions of nHgbAI-immunized pigs challenged with a homologous H. ducreyi strain.

The recovery of viable H. ducreyi cells from biopsy specimens is shown in Table 1. At both challenge inocula (104 and 103 CFU), no H. ducreyi cells were isolated from nHgbAI-immunized animals challenged with homologous strain 35000HPhgbAI, whereas all mock-immunized animals yielded viable H. ducreyi (P < 0.001). In heterologous challenge experiments, all pigs, whether nHgbAI or mock immunized, yielded strain 35000HPhgbAII (P = 1.000).

Analysis of bacterial recovery at the lesion level revealed striking differences between nHgbAI- and mock-immunized animals infected with the homologous H. ducreyi strain. In the control group, 13 of 14 lesions yielded H. ducreyi strain 35000HPhgbAI at an inoculum of 104 CFU. In the nHgbAI-immunized group, 0 of 16 lesions yielded H. ducreyi (P < 0.001). At the lower dilution (103 CFU), 9 of 14 lesions in mock-immunized animals yielded H. ducreyi strain 35000HPhgbAI, whereas 0 of 8 lesions yielded H. ducreyi strain 35000HPhgbAI in nHgbAI-immunized animals (P = 0.006). Thus, the nHgbAI vaccine provided protection against a bacterial challenge of at least 10 times the minimum infectious dose. In heterologous challenge experiments, 10 of 14 lesions in the control group yielded H. ducreyi strain 35000HPhgbAII, compared to 10 of 16 lesions from the nHgbAI-immunized group at a 104 CFU inoculum (P = 0.709). Therefore, based on macroscopic examination, histological sections, and recovery of H. ducreyi cells, there was homologous protection against strain 35000HPhgbAI but no protection against the genetically engineered heterologous strain 35000HPhgbAII by the nHgbAI vaccine.

The activity of the antiserum from nHgbAI/MPL-immunized animals was lower than the activity of antiserum of nHgbAI/Freund's-immunized pigs.

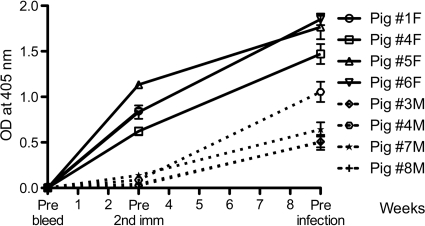

We analyzed the humoral immune response of nHgbAI-immunized animals in a number of in vitro assays. An ELISA was performed to compare the antibody activity developed in response to our current MPL adjuvant HgbA vaccine to that of antiserum generated from the previous study using Freund's adjuvant (Fig. 2). The Freund's antiserum activity was approximately 7-fold higher than the MPL antiserum activity prior to the second immunization (P = 0.029) and approximately 2 to 3 times higher than the MPL activity after the third immunization (prior to infection) (P = 0.057). Of note, one of the four pigs immunized with nHgbAI/MPL (pig 4M) showed ELISA activity twice as high as that found for the other three MPL-immunized pigs after the third immunization, indicating that different animals can respond differently to the vaccine preparation. Preimmune and mock-immune pig sera were free of anti-nHgbAI antibodies (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

The activity of the nHgbAI/MPL antisera is lower than that of the antisera from nHgbAI/Freund's-immunized animals. Sera were collected preimmunization (prebleed), before the second immunization, and prior to challenge infection (three weeks after the third immunization). Data are expressed as OD405 readings and given as median ± variance. Solid lines represent data from each pig immunized with nHgbAI/Freund's adjuvant (1F, 4F, 5F, and 6F) (1), whereas dotted lines represent data from pigs immunized with nHgbAI/MPL adjuvant (3M, 4M, 7M, and 8M). ELISA data for week 6 (prior to 3rd immunization) are not shown due to an incomplete data set for nHgbAI/Freund's antiserum samples. P values comparing anti-nHgbAI antibodies using Freund's and MPL adjuvants after one and after three immunizations (just prior to challenge) were 0.029 and 0.057, respectively, and were determined using the Mann-Whitney rank sum test (n = 3).

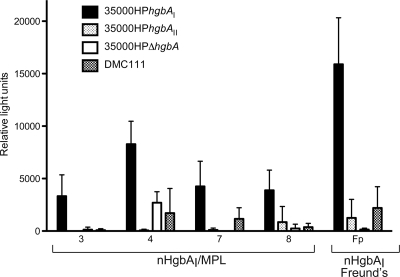

Two different assays were employed to determine whether antisera from nHgbAI/MPL-immunized pigs recognized surface-exposed epitopes of HgbA in the context of whole cells of H. ducreyi. The first technique, a whole-cell binding ELISA, measured the relative amounts of antibodies bound to the surface of different H. ducreyi strains expressing either class I (wild-type strain 35000HPhgbAI) or class II (strain 35000HPhgbAII) HgbA or expressing class II HgbA in the native class II H. ducreyi background (wild-type strain DMC111), as detected by a secondary antibody conjugate (Fig. 3) and compared to an H. ducreyi strain that does not express HgbA (strain 35000HPΔhgbA). Antisera from all four nHgbAI/MPL-immunized pigs and pooled anti-nHgbAI/Freund's antisera showed greater reactivity with strain 35000HPhgbAI than with strains 35000HPhgbAII, 35000HPΔhgbA, or DMC111 (Fig. 3). As was observed in the solid-phase ELISA, there was also a statistically significant difference between the reactivity of pooled nHgbAI/Freund's antiserum and all four nHgbAI/MPL antisera with strain 35000HPhgbAI (P values range from < 0.001 to 0.005) (Fig. 3). Antisera taken from mock-immunized pigs and prebleeds from nHgbAI/MPL-immunized pigs reacted poorly with all strains of H. ducreyi tested (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

nHgbAI/MPL antisera bind HgbAI but not HgbAII in the context of whole H. ducreyi cells. Antisera from individual pigs (pigs 3, 4, 7, and 8), obtained after three immunizations with nHgbAI/MPL, and pooled antiserum from pigs immunized with nHgbAI/Freund's (Fp; obtained from a previous study) (1) were tested for binding to whole cells of H. ducreyi strains 35000HPhgbAI, 35000HPhgbAII, 35000HPΔhgbA, and DMC111. The antisera used in these assays were from preinfection bleeds. Experiments were performed in triplicate on at least three different days. Data are expressed as relative light units and given as median ± variance. A P value of 0.005 was found for the difference between the binding of nHgbAI/MPL and nHgbAI/Freund's antisera to whole cells of H. ducreyi strain 35000HPhgbAI (Mann-Whitney rank sum test).

The second method used to examine the interaction between anti-nHgbAI and surface-exposed epitopes on H. ducreyi whole cells was an immunoprecipitation assay. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Coomassie blue staining (Fig. 4A) and Western blotting (Fig. 4B). Pooled anti-nHgbAI/MPL antisera precipitated nHgbAI from H. ducreyi strain 35000HPhgbAI but with less reactivity than with pooled antisera from pigs immunized with nHgbAI/Freund's (Fig. 4A1 and B1). Neither antibody preparation precipitated nHgbAII in a 35000HP background (Fig. 4A2 and B2). Only pooled anti-nHgbAI/Freund's was able to immunoprecipitate nHgbAII from the wild-type strain DMC111 (Fig. 4A3 and B3).

Antiserum elicited by the nHgbAI/MPL vaccine partially inhibited the binding of DIG-Hb to nHgbA.

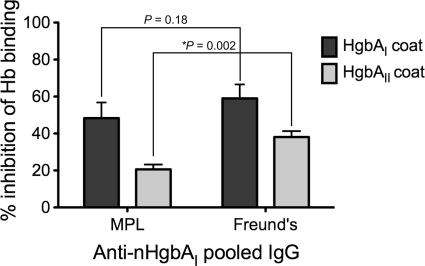

We examined the ability of purified anti-nHgbAI IgG to block the binding of Hb to immobilized nHgbAI or nHgbAII in an ELISA format (1). Pooled IgG purified from serum of nHgbAI/Freund's-immunized pigs (1) blocked 59% of DIG-Hb/nHgbAI binding, while pooled IgG purified from nHgbAI/MPL-immunized pigs blocked 48% of binding (P = 0.180) (Fig. 5). There was a significant difference between IgGs purified from nHgbAI/Freund's-immunized (38.1% inhibition) and nHgbAI/MPL-immunized pigs (20.6% inhibition) (P = 0.002) (Fig. 5) in blocking Hb/nHgbAII interactions. IgG purified from pooled sera of mock-immunized pigs failed to interfere with the binding of Hb to either nHgbAI or nHgbAII (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

IgGs from nHgbAI/MPL-immunized animals partially inhibit Hb binding to nHgbA. The ability of pooled IgGs from pigs immunized with either nHgbAI/MPL or nHgbAI/Freund's to inhibit the binding of Hb to immobilized nHgbAI or nHgbAII was measured. P values comparing the ability of anti-nHgbAI IgG to block Hb binding to nHgbAI and nHgbAII were determined using the Mann-Whitney rank sum test. Pooled nHgbAI/Freund's IgG was purified from antisera obtained in a previous study (1) (n = 3).

Antisera from nHgbAI/MPL pigs did not exhibit bactericidal activity.

We performed immune bactericidal assays using purified IgG from nHgbAI/MPL-immunized pigs as previously described (1, 18). We were unable to demonstrate bactericidal killing in the presence of human complement using either H. ducreyi strain as a target (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Administering the nHgbAI vaccine with an adjuvant approved for use in humans was as effective as using Freund's adjuvant.

This study is similar to a previous vaccine study conducted in our laboratory, which demonstrated complete protection using purified nHgbAI as immunogen (1). In the previous study, we used Freund's adjuvant, while MPL was used as adjuvant in the present study. Monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL) is a detoxified lipopolysaccharide analog isolated from Salmonella enterica serovar Minnesota R595. The structure, mechanism of action, and immunologic responses to MPL have been the subjects of intense investigation for many decades (11), and the safety of MPL has been extensively documented (5, 65). MPL has been successfully utilized as an adjuvant in numerous human vaccines, including vaccines for human papillomavirus 16/18 (HPV) (27, 28, 46), hepatitis B virus (HBV) (36, 61), and herpes simplex virus (HSV) (57). In these trials, MPL was used in combination with alum in the GSK proprietary AS04 adjuvant system (23). MPL has also been examined as an adjuvant in vaccines against malaria (24, 30, 59), leishmania (9), anthrax (32), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) (54), and HIV (39, 43) and against allergies to house dust mites (6), ragweed pollen (7), and grass pollen (16). All of these studies showed that MPL is a successful and safe adjuvant.

The nHgbAI vaccine administered with MPL protected only against a homologous H. ducreyi strain.

The current study advances the findings from the original nHgbAI vaccine study in that we examined the ability of this vaccine to protect against strain 35000HP expressing a (heterologous) class II HgbA protein (HgbAII). In alignments of HgbA from 10 strains of H. ducreyi, HgbA was highly conserved, showing ≥95% identity between strain classes (67). Based on this high degree of identity, we anticipated that nHgbAI would provide cross-protection against strains expressing HgbA from either class of H. ducreyi strains. Surprisingly, this is not what we observed. Immunization with the nHgbAI/MPL vaccine offered full protection to pigs when challenged with H. ducreyi strain 35000HPhgbAI (homologous), but not from a challenge with H. ducreyi strain 35000HPhgbAII (heterologous). Since these are isogenic strains, except for the HgbA protein (HgbAI versus HgbAII), two conclusions can be drawn from the results: (i) slight dissimilarities in the amino acid sequence between these 2 proteins are responsible for the difference in protection, and (ii) the observed protection cannot be the result of a protective response elicited by minor antigens contaminating the vaccine preparation.

In another of our previous studies, we found that loop 4 of HgbA is surface exposed and the largest, most immunodominant and variable loop among the 11 putatively exposed loops of HgbA (44). Including the highly conserved membrane-spanning segments, loops 4 of HgbA proteins are 91% identical between strains (16 of 186 amino acids are different). These results suggest that at least part of the protective response against HgbAI lies in exposed epitopes from loop 4. Such divergence between strains in protective epitopes of surface-exposed outer membrane proteins has been shown in the development of gonococcal and meningococcal protein vaccines (15, 42, 64) and resulted in the requirement for multivalent vaccines in the latter.

Because preliminary experiments showed that wild-type class II strains were either weakly or noninfectious in the swine model (data not shown), an H. ducreyi class I strain expressing a class II HgbA protein was constructed in the current study in order to determine the possibility of heterologous protection. However, the use of an isogenic class II construct has certain limitations. Class II strains typically grow more slowly than class I strains, which may explain why they were less infectious in the swine model. Moreover, class II strains have a truncated LOS compared to that of class I strains (50, 53, 67), and it is possible that HgbAII may be more exposed in a truncated LOS background. In data not presented here, anti-HgbA monoclonal antibody 1.51 binds poorly to whole cells of wild-type 35000HPhgbAI but binds a 35000HP gmhA mutant (an isogenic mutant with a short LOS) (8) and two of four class II strains containing truncated LOS, including strain DMC111 (data not shown). These data suggest that the presence of a longer LOS molecule is responsible for the lack of monoclonal antibody 1.51 binding to HgbA on the surface of H. ducreyi. As shown by the results in Fig. 4, polyclonal anti-nHgbAI antibodies bound better to strain DMC111 than to strain 35000HPhgbAII, consistent with this notion. Thus, if additional HgbA epitopes are exposed in the context of a class II LOS, then it is possible that the nHgbAI vaccine might offer some cross-protection for wild-type class II H. ducreyi strains.

Despite activity lower than that of antiserum from anti-nHgbAI/Freund's immunization, antiserum from animals immunized with the nHgbAI/MPL vaccine partially blocked DIG-Hb binding to HgbA.

The ELISA activity of antiserum from HgbAI/MPL-immunized pigs to nHgbAI was lower than the activity of antiserum from our earlier study using Freund's adjuvant after the first and third immunizations. These results are consistent with the results of two other immunization studies using other protein antigens in rabbits, which showed higher ELISA activity obtained using Freund's adjuvant (33, 41). We attempted to compare the antibody response of nHgbAI/MPL antiserum to immobilized nHgbAII in an ELISA format to determine if this might correlate with protection. However, the two HgbA proteins did not appear to bind the ELISA plates equally or may not have been equally in native conformation, either of which may have skewed the results. Variability in binding and folding of the different classes of HgbA proteins also prevented us from making valid conclusions about the results obtained in the ELISA measuring blocking of Hb binding (Fig. 5), even though some comparisons were statistically significant. Further work is necessary to elucidate the causes of the different binding capabilities of classes of HgbA proteins.

Instead of making comparisons of antiserum binding to purified protein, we compared the binding of nHgbAI/MPL antisera to whole cells of the isogenic pair of 35000HP strains. As predicted, the homologous strain bound more antibodies than the heterologous strain in both whole-cell ELISA and the immunoprecipitation assay (Fig. 3 and 4). Similar to the activity measured by ELISA, the whole-cell antibody binding activity from the previous nHgbAI/Freund's immunization study was higher than the activity from the present nHgbAI/MPL study.

The ability of antibodies to block Hb binding to immobilized nHgbAI and nHgbAII was measured using an ELISA-based assay. Antibodies from both MPL and Freund's adjuvant groups modestly blocked Hb binding to either class of HgbA protein (Fig. 5). Despite significantly higher ELISA activity with Freund's antiserum, there was no significant difference in the ability of either IgG pool to inhibit Hb binding to homologous HgbAI. However, Freund's pooled IgG significantly inhibited the binding of Hb to heterologous HgbAII compared to the inhibition by MPL pooled IgG.

The lack of bactericidal and opsonophagocytic killing of H. ducreyi is well documented in the literature (2, 22, 31, 37, 45, 63, 68). In this study, bactericidal activity was not observed using antisera from nHgbAI/MPL-immunized pigs. This differed from the results of a previous study that showed modest bactericidal activity using antiserum from nHgbAI/Freund's-immunized pigs (1). The lack of bactericidal activity using nHgbAI/MPL antisera may be due to lower antibody titers, lower antibody affinity, or inability to fix complement.

We previously studied opsonophagocytosis by nHgbAI/Freund's pooled antisera. In a luminol-enhanced chemiluminescence assay, human neutrophils were not significantly stimulated in the presence of nHgbAI/Freund's antiserum and complement, whereas controls stimulated neutrophils (data not shown). Furthermore, human neutrophils failed to kill H. ducreyi cells opsonized with nHgbAI/Freund's antiserum and complement, while control bacteria were killed (data not shown). Since nHgbAI/Freund's antiserum, which has a higher activity than nHgbAI/MPL antiserum, did not exhibit any bactericidal activity, we did not test the opsonic activity of nHgbAI/MPL antiserum obtained in the current study.

Future studies.

Anti-nHgbAI antibodies bound better to class I-specific epitopes and failed to protect against a heterologous challenge, which suggests that the protective epitopes lie in the divergent central domain of HgbA. Studies are under way to determine whether a vaccine containing the central domain of HgbA (loops 4 through 7) is protective for class I strains.

The mechanism of protection of the HgbA vaccine (cellular versus humoral) is not known. However, the results of a previous study using passively transferred serum from thrice-infected pigs suggested that the humoral response was sufficient to protect from an H. ducreyi challenge (13). Studies are under way in our laboratory to determine whether protection using passively transferred serum from nHgbAI-immunized pigs is sufficient to provide protection.

Based on our results, it remains unclear whether a single HgbA protein will protect against both classes of H. ducreyi, and it is possible that a bivalent vaccine might be needed. While anti-nHgbAI antibodies did not bind well to class II HgbA in the genetically engineered 35000HP background, they bound moderately well to class II HgbA in the wild-type class II (DMC111) background, possibly due to differences in LOS or other antigens. Thus, based on our previous (1), present, and a third study under way (unpublished data), binding to whole cells and blocking Hb binding to HgbA are the two in vitro assays that correlate with the protection of the nHgbAI vaccine.

The immune response to nHgbAI/MPL was relatively modest, similar to the results of other studies using different antigens. Newer vaccines using MPL have overcome this problem by including alum in the vaccine mixtures with MPL (termed AS04), and we will examine this in our system. Despite these limitations, we have proof of concept that nHgbAI in conjunction with an adjuvant approved for use in humans can provide complete homologous protection in a highly relevant animal model, paving the way toward phase I clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christopher Thomas for critical comments on the manuscript. We thank Annice Rountree for excellent technical support.

This work was supported by grant 5-R01-AI 05393 from the NIH to C.E.

Editor: J. N. Weiser

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 June 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Afonina, G., I. Leduc, I. Nepluev, C. Jeter, P. Routh, G. Almond, P. E. Orndorff, M. Hobbs, and C. Elkins. 2006. Immunization with the Haemophilus ducreyi hemoglobin receptor HgbA protects against infection in the swine model of chancroid. Infect. Immun. 74:2224-2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed, H. J., C. Johansson, L. A. Svensson, K. Ahlman, M. Verdrengh, and T. Lagergard. 2002. In vitro and in vivo interactions of Haemophilus ducreyi with host phagocytes. Infect. Immun. 70:899-908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Tawfiq, J. A., K. R. Fortney, B. P. Katz, A. F. Hood, C. Elkins, and S. M. Spinola. 2000. An isogenic hemoglobin receptor-deficient mutant of Haemophilus ducreyi is attenuated in the human model of experimental infection. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1049-1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Tawfiq, J. A., A. C. Thornton, B. P. Katz, K. R. Fortney, K. D. Todd, A. F. Hood, and S. M. Spinola. 1998. Standardization of the experimental model of Haemophilus ducreyi infection in human subjects. J. Infect. Dis. 178:1684-1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baldrick, P., D. Richardson, G. Elliott, and A. W. Wheeler. 2002. Safety evaluation of monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL): an immunostimulatory adjuvant. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 35:398-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baldrick, P., D. Richardson, and A. W. Wheeler. 2001. Safety evaluation of a glutaraldehyde modified tyrosine adsorbed housedust mite extract containing monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL) adjuvant: a new allergy vaccine for dust mite allergy. Vaccine 20:737-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baldrick, P., D. Richardson, S. R. Woroniecki, and B. Lees. 2007. Pollinex Quattro ragweed: safety evaluation of a new allergy vaccine adjuvanted with monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL) for the treatment of ragweed pollen allergy. J. Appl. Toxicol. 27:399-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bauer, B. A., M. K. Stevens, and E. J. Hansen. 1998. Involvement of the Haemophilus ducreyi gmhA gene product in lipooligosaccharide expression and virulence. Infect. Immun. 66:4290-4298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertholet, S., Y. Goto, L. Carter, A. Bhatia, R. F. Howard, D. Carter, R. N. Coler, T. S. Vedvick, and S. G. Reed. 2009. Optimized subunit vaccine protects against experimental leishmaniasis. Vaccine 27:7036-7045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buchanan, S. K., B. S. Smith, L. Venkatramani, D. Xia, L. Esser, M. Palnitkar, R. Chakraborty, D. van der Helm, and J. Deisenhofer. 1999. Crystal structure of the outer membrane active transporter FepA from Escherichia coli. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6:56-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casella, C. R., and T. C. Mitchell. 2008. Putting endotoxin to work for us: monophosphoryl lipid A as a safe and effective vaccine adjuvant. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65:3231-3240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chimento, D. P., A. K. Mohanty, R. J. Kadner, and M. C. Wiener. 2003. Substrate-induced transmembrane signaling in the cobalamin transporter BtuB. Nat. Struct. Biol. 10:394-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cole, L. E., K. L. Toffer, R. A. Fulcher, L. R. San Mateo, P. E. Orndorff, and T. H. Kawula. 2003. A humoral immune response confers protection against Haemophilus ducreyi infection. Infect. Immun. 71:6971-6977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cornelis, P., and S. Matthijs. 2002. Diversity of siderophore-mediated iron uptake systems in fluorescent pseudomonads: not only pyoverdines. Environ. Microbiol. 4:787-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cornelissen, C. N., J. E. Anderson, and P. F. Sparling. 1997. Characterization of the diversity and the transferrin-binding domain of gonococcal transferrin-binding protein 2. Infect. Immun. 65:822-828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drachenberg, K. J., A. W. Wheeler, P. Stuebner, and F. Horak. 2001. A well-tolerated grass pollen-specific allergy vaccine containing a novel adjuvant, monophosphoryl lipid A, reduces allergic symptoms after only four preseasonal injections. Allergy 56:498-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elkins, C. 1995. Identification and purification of a conserved heme-regulated hemoglobin-binding outer membrane protein from Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect. Immun. 63:1241-1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elkins, C., N. H. Carbonetti, V. A. Varela, D. Stirewalt, D. G. Klapper, and P. F. Sparling. 1992. Antibodies to N-terminal peptides of gonococcal porin are bactericidal when gonococcal lipopolysaccharide is not sialylated. Mol. Microbiol. 6:2617-2628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elkins, C., K. Yi, B. Olsen, C. Thomas, K. Thomas, and S. Morse. 2000. Development of a serological test for Haemophilus ducreyi for seroprevalence studies. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1520-1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferguson, A. D., R. Chakraborty, B. S. Smith, L. Esser, D. van der Helm, and J. Deisenhofer. 2002. Structural basis of gating by the outer membrane transporter FecA. Science 295:1715-1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferguson, A. D., E. Hofmann, J. W. Coulton, K. Diederichs, and W. Welte. 1998. Siderophore-mediated iron transport: crystal structure of FhuA with bound lipopolysaccharide. Science 282:2215-2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frisk, A., H. J. Ahmed, E. Van Dyck, and T. Lagergard. 1998. Antibodies specific to surface antigens are not effective in complement-mediated killing of Haemophilus ducreyi. Microb. Pathog. 25:67-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcon, N. 2010. Preclinical development of AS04. Methods Mol. Biol. 626:15-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordon, D. M., T. W. McGovern, U. Krzych, J. C. Cohen, I. Schneider, R. LaChance, D. G. Heppner, G. Yuan, M. Hollingdale, M. Slaoui, et al. 1995. Safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of a recombinantly produced Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein-hepatitis B surface antigen subunit vaccine. J. Infect. Dis. 171:1576-1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hammond, G. W., C. J. Lian, J. C. Wilt, and A. R. Ronald. 1978. Comparison of specimen collection and laboratory techniques for isolation of Haemophilus ducreyi. J. Clin. Microbiol. 7:39-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hansen, E. J., C. F. Frisch, and K. H. Johnston. 1981. Detection of antibody-accessible proteins on the cell surface of Haemophilus influenzae type b. Infect. Immun. 33:950-953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harper, D. M., E. L. Franco, C. Wheeler, D. G. Ferris, D. Jenkins, A. Schuind, T. Zahaf, B. Innis, P. Naud, N. S. De Carvalho, C. M. Roteli-Martins, J. Teixeira, M. M. Blatter, A. P. Korn, W. Quint, and G. Dubin. 2004. Efficacy of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine in prevention of infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 364:1757-1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harper, D. M., E. L. Franco, C. M. Wheeler, A. B. Moscicki, B. Romanowski, C. M. Roteli-Martins, D. Jenkins, A. Schuind, S. A. Costa Clemens, and G. Dubin. 2006. Sustained efficacy up to 4.5 years of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine against human papillomavirus types 16 and 18: follow-up from a randomised control trial. Lancet 367:1247-1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayes, R., K. Schulz, and F. Plummer. 1995. The cofactor effect of genital ulcers on the per-exposure risk of HIV transmission in sub-Saharan Africa. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 98:1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heppner, D. G., D. M. Gordon, M. Gross, B. Wellde, W. Leitner, U. Krzych, I. Schneider, R. A. Wirtz, R. L. Richards, A. Trofa, T. Hall, J. C. Sadoff, P. Boerger, C. R. Alving, D. R. Sylvester, T. G. Porter, and W. R. Ballou. 1996. Safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of Plasmodium falciparum repeatless circumsporozoite protein vaccine encapsulated in liposomes. J. Infect. Dis. 174:361-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hiltke, T. J., M. E. Bauer, J. Klesney-Tait, E. J. Hansen, R. S. Munson, Jr., and S. M. Spinola. 1999. Effect of normal and immune sera on Haemophilus ducreyi 35000HP and its isogenic MOMP and LOS mutants. Microb. Pathog. 26:93-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ivins, B. E., M. L. Pitt, P. F. Fellows, J. W. Farchaus, G. E. Benner, D. M. Waag, S. F. Little, G. W. Anderson, Jr., P. H. Gibbs, and A. M. Friedlander. 1998. Comparative efficacy of experimental anthrax vaccine candidates against inhalation anthrax in rhesus macaques. Vaccine 16:1141-1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnston, B. A., H. Eisen, and D. Fry. 1991. An evaluation of several adjuvant emulsion regimens for the production of polyclonal antisera in rabbits. Lab. Anim. Sci. 41:15-21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.King, R., J. Gough, A. Ronald, J. Nasio, J. O. Ndinya-Achola, F. Plummer, and J. A. Wilkins. 1996. An immunohistochemical analysis of naturally occurring chancroid. J. Infect. Dis. 174:427-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kreiss, J. K., R. Coombs, F. Plummer, K. K. Holmes, B. Nikora, W. Cameron, E. Ngugi, J. O. Ndinya-Achola, and L. Corey. 1989. Isolation of the human immunodeficiency virus from genital ulcers in Nairobi prostitutes. J. Infect. Dis. 160:380-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kundi, M. 2007. New hepatitis B vaccine formulated with an improved adjuvant system. Expert Rev. Vaccines 6:133-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lagergard, T., A. Frisk, M. Purven, and L. A. Nilsson. 1995. Serum bactericidal activity and phagocytosis in host defence against Haemophilus ducreyi. Microb. Path. 18:37-51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leduc, I., K. E. Banks, K. R. Fortney, K. B. Patterson, S. D. Billings, B. P. Katz, S. M. Spinola, and C. Elkins. 2008. Evaluation of the repertoire of the TonB-dependent receptors of Haemophilus ducreyi for their role in virulence in humans. J. Infect. Dis. 197:1103-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liao, H. X., G. J. Cianciolo, H. F. Staats, R. M. Scearce, D. M. Lapple, S. H. Stauffer, J. R. Thomasch, S. V. Pizzo, D. C. Montefiori, M. Hagen, J. Eldridge, and B. F. Haynes. 2002. Increased immunogenicity of HIV envelope subunit complexed with alpha2-macroglobulin when combined with monophosphoryl lipid A and GM-CSF. Vaccine 20:2396-2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Locher, K. P., B. Rees, R. Koebnik, A. Mitschler, L. Moulinier, J. P. Rosenbusch, and D. Moras. 1998. Transmembrane signaling across the ligand-gated FhuA receptor: crystal structures of free and ferrichrome-bound states reveal allosteric changes. Cell 95:771-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mallon, F. M., M. E. Graichen, B. R. Conway, M. S. Landi, and H. C. Hughes. 1991. Comparison of antibody response by use of synthetic adjuvant system and Freund complete adjuvant in rabbits. Am. J. Vet. Res. 52:1503-1506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McGuinness, B., A. K. Barlow, I. N. Clarke, J. E. Farley, A. Anilionis, J. T. Poolman, and J. E. Heckels. 1990. Deduced amino acid sequences of class 1 protein (PorA) from three strains of Neisseria meningitidis. Synthetic peptides define the epitopes responsible for serosubtype specificity. J. Exp. Med. 171:1871-1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moore, A., L. McCarthy, and K. H. Mills. 1999. The adjuvant combination monophosphoryl lipid A and QS21 switches T cell responses induced with a soluble recombinant HIV protein from Th2 to Th1. Vaccine 17:2517-2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nepluev, I., G. Afonina, W. G. Fusco, I. Leduc, B. Olsen, B. Temple, and C. Elkins. 2009. An immunogenic, surface-exposed domain of Haemophilus ducreyi outer membrane protein HgbA is involved in hemoglobin binding. Infect. Immun. 77:3065-3074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Odumeru, J. A., G. M. Wiseman, and A. R. Ronald. 1985. Role of lipopolysaccharide and complement in susceptibility of Haemophilus ducreyi to human serum. Infect. Immun. 50:495-499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paavonen, J., D. Jenkins, F. X. Bosch, P. Naud, J. Salmeron, C. M. Wheeler, S. N. Chow, D. L. Apter, H. C. Kitchener, X. Castellsague, N. S. de Carvalho, S. R. Skinner, D. M. Harper, J. A. Hedrick, U. Jaisamrarn, G. A. Limson, M. Dionne, W. Quint, B. Spiessens, P. Peeters, F. Struyf, S. L. Wieting, M. O. Lehtinen, and G. Dubin. 2007. Efficacy of a prophylactic adjuvanted bivalent L1 virus-like-particle vaccine against infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: an interim analysis of a phase III double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 369:2161-2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Plummer, F. A., L. J. D'Costa, H. Nsanze, P. Karasira, I. W. MacLean, P. Piot, and A. R. Ronald. 1985. Clinical and microbiologic studies of genital ulcers in Kenyan women. Sex. Transm. Dis. 12:193-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Plummer, F. A., J. N. Simonsen, D. W. Cameron, J. O. Ndinya-Achola, J. K. Kreiss, M. N. Gakinya, P. Waiyaki, M. Cheang, P. Piot, A. R. Ronald, and E. N. Ngugi. 1991. Cofactors in male-female sexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Infect. Dis. 163:233-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Post, D. M., and B. W. Gibson. 2007. Proposed second class of Haemophilus ducreyi strains show altered protein and lipooligosaccharide profiles. Proteomics 7:3131-3142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Post, D. M., R. S. Munson, Jr., B. Baker, H. Zhong, J. A. Bozue, and B. W. Gibson. 2007. Identification of genes involved in the expression of atypical lipooligosaccharide structures from a second class of Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect. Immun. 75:113-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ronald, A. R., and F. A. Plummer. 1985. Chancroid and Haemophilus ducreyi. Ann. Intern. Med. 102:705-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.San Mateo, L. R., K. L. Toffer, P. E. Orndorff, and T. H. Kawula. 1999. Neutropenia restores virulence to an attenuated Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase-deficient Haemophilus ducreyi strain in the swine model of chancroid. Infect. Immun. 67:5345-5351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scheffler, N. K., A. M. Falick, S. C. Hall, W. C. Ray, D. M. Post, R. S. Munson, Jr., and B. W. Gibson. 2003. Proteome of Haemophilus ducreyi by 2-D SDS-PAGE and mass spectrometry: strain variation, virulence, and carbohydrate expression. J. Proteome Res. 2:523-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sokal, E. M., K. Hoppenbrouwers, C. Vandermeulen, M. Moutschen, P. Leonard, A. Moreels, M. Haumont, A. Bollen, F. Smets, and M. Denis. 2007. Recombinant gp350 vaccine for infectious mononucleosis: a phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of an Epstein-Barr virus vaccine in healthy young adults. J. Infect. Dis. 196:1749-1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spinola, S. M., A. Orazi, J. N. Arno, K. Fortney, P. Kotylo, C. Y. Chen, A. A. Campagnari, and A. F. Hood. 1996. Haemophilus ducreyi elicits a cutaneous infiltrate of CD4 cells during experimental human infection. J. Infect. Dis. 173:394-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Spinola, S. M., L. M. Wild, M. A. Apicella, A. A. Gaspari, and A. A. Campagnari. 1994. Experimental human infection with Haemophilus ducreyi. J. Infect. Dis. 169:1146-1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stanberry, L. R., S. L. Spruance, A. L. Cunningham, D. I. Bernstein, A. Mindel, S. Sacks, S. Tyring, F. Y. Aoki, M. Slaoui, M. Denis, P. Vandepapeliere, and G. Dubin. 2002. Glycoprotein-D-adjuvant vaccine to prevent genital herpes. N. Engl. J. Med. 347:1652-1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Steen, R. 2001. Eradicating chancroid. Bull. World Health Organ. 79:818-826. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stoute, J. A., K. E. Kester, U. Krzych, B. T. Wellde, T. Hall, K. White, G. Glenn, C. F. Ockenhouse, N. Garcon, R. Schwenk, D. E. Lanar, P. Sun, P. Momin, R. A. Wirtz, C. Golenda, M. Slaoui, G. Wortmann, C. Holland, M. Dowler, J. Cohen, and W. R. Ballou. 1998. Long-term efficacy and immune responses following immunization with the RTS,S malaria vaccine. J. Infect. Dis. 178:1139-1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Swanson, J., L. W. Mayer, and M. R. Tam. 1982. Antigenicity of Neisseria gonorrhoeae outer membrane protein(s) III detected by immunoprecipitation and Western blot transfer with a monoclonal antibody. Infect. Immun. 38:668-672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tong, N. K., J. Beran, S. A. Kee, J. L. Miguel, C. Sanchez, J. M. Bayas, A. Vilella, J. R. de Juanes, P. Arrazola, F. Calbo-Torrecillas, E. L. de Novales, V. Hamtiaux, M. Lievens, and M. Stoffel. 2005. Immunogenicity and safety of an adjuvanted hepatitis B vaccine in pre-hemodialysis and hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 68:2298-2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Trees, D. L., and S. A. Morse. 1995. Chancroid and Haemophilus ducreyi: an update. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 8:357-375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vakevainen, M., S. Greenberg, and E. J. Hansen. 2003. Inhibition of phagocytosis by Haemophilus ducreyi requires expression of the LspA1 and LspA2 proteins. Infect. Immun. 71:5994-6003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van der Ley, P., J. E. Heckels, M. Virji, P. Hoogerhout, and J. T. Poolman. 1991. Topology of outer membrane porins in pathogenic Neisseria spp. Infect. Immun. 59:2963-2971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Verstraeten, T., D. Descamps, M. P. David, T. Zahaf, K. Hardt, P. Izurieta, G. Dubin, and T. Breuer. 2008. Analysis of adverse events of potential autoimmune aetiology in a large integrated safety database of AS04 adjuvanted vaccines. Vaccine 26:6630-6638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wasserheit, J. 1992. Epidemiological survey. Interrelationships between human immunodeficiency virus infection and other sexually transmitted diseases. Sex. Transm. Dis. 19:61-77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.White, C. D., I. Leduc, B. Olsen, C. Jeter, C. Harris, and C. Elkins. 2005. Haemophilus ducreyi outer membrane determinants, including DsrA, define two clonal populations. Infect. Immun. 73:2387-2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wood, G. E., S. M. Dutro, and P. A. Totten. 2001. Haemophilus ducreyi inhibits phagocytosis by U-937 cells, a human macrophage-like cell line. Infect. Immun. 69:4726-4733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]