Abstract

A new bacterial xylanase belonging to family 5 of glycosyl hydrolases was identified and characterized. The xylanase, Xyn5B from Bacillus sp. strain BP-7, was active on neutral, nonsubstituted xylooligosaccharides, showing a clear difference from other GH5 xylanases characterized to date that show a requirement for methyl-glucuronic acid side chains for catalysis. The enzyme was evaluated on Eucalyptus kraft pulp, showing its effectiveness as a bleaching aid.

The catabolic breakdown of xylan is a critical step in the recycling of carbon in nature and has been targeted as a subject of intense research as a renewable energy resource as well as for bioconversion of plant biomass into high-added-value products (21, 29, 37, 40). Biodegradation of xylan is a complex process that requires the coordinate action of several enzymes, among which xylanases (1,4-β-D-xylan xylanohydrolase; EC 3.2.1.8), cleaving internal linkages on the β-1,4-xylose backbone, play a key role.

Most known xylanases are grouped into glycoside hydrolase (GH) families 10 and 11 (CAZy [Carbohydrate-Active enZYmes] database) (17), although a few xylanases have recently been ascribed to glycoside hydrolase families 5, 7, 8, and 43 (8, 9, 24). Among xylanases not grouped in the typical families GH10 and GH11, only two xylanases belonging to family GH5 have been biochemically characterized in detail. The enzymes XynA from Erwinia chrysanthemi (18, 39) and XynC from Bacillus subtilis (32) hydrolyze glucuronoxylan to branched xylooligosaccharides. The activity of Erwinia chrysanthemi XynA has also been evaluated on other substrates containing xylose, showing an absolute requirement for methyl-glucuronic substitutions. In this way, only methyl-glucuronic acid-branched oligosaccharides can be cleaved by XynA, whereas linear xylooligosaccharides or arabinoxylans are not cleaved by this enzyme (39). This type of xylanases must play an important role in complementing the action of GH10 and GH11 enzymes during depolymerization of glucuronoxylans in lignocellulosic fibers.

Xylanases are widely used in the pulp industry to enhance the effectiveness of bleaching agents, thereby reducing the generation of toxic wastes (adsorbable organic halogens; AOX) (1, 38). Several reports have evaluated the effectiveness of family GH10 and GH11 xylanases on the bleaching process, showing that GH11 xylanases usually display better performance (7, 12), although there are many other factors that contribute to the bleach-boosting effect of a xylanase, such as the source of the pulp and the pulping process itself (6, 11). Besides their contribution to the increase in brightness, an innovative aspect of the application of xylanases is their contribution to the removal of hexenuronic acids (HexA) produced during the kraft cooking process, which can accelerate the brightness reversion (yellowing tendency) of paper (35). However, it remains to be known if all xylanases are capable of removing HexAs and/or enhancing bleachability.

Bacillus sp. strain BP-7 is a xylanolytic strain isolated from agricultural soils (25). It shows a multiple enzymatic system for xylan degradation, including a GH11 xylanase cloned and characterized previously (13). In this work, we describe the identification and cloning of a second xylanase from the strain, belonging to the GH5 family. The enzyme hydrolyzes linear xylooligosaccharides, clearly differing from the two GH5 xylanases characterized up to date. The new enzyme has been tested on Eucalyptus pulps, showing good performance as a bleaching aid. The results obtained suggest an important role for the enzyme in xylan degradation and indicate the potential of this xylanase for biotechnological applications in the bioconversion of glucuronoxylan-containing biomass.

Cloning and sequence analysis of Xyn5B.

A gene library from Bacillus sp. strain BP-7, previously constructed in Escherichia coli (28), was screened for xylanase activity on agar LB plates containing 0.1% Remazol brilliant blue R-d-xylan. Two clones out of the 4,500 tested showed clear hydrolysis halos around the colonies and contained the same recombinant plasmid, carrying an 8.7-kbp DNA insert. Sequencing of this DNA fragment showed a 1,269-bp open reading frame coding for a protein of 423 amino acids with homology to xylanases from glycoside hydrolase family 5. The enzyme was named Xyn5B, in agreement with the proposed international nomenclature (CAZy). The deduced amino acid sequence of Xyn5B showed homology to XynC from Bacillus subtilis (92% identity) (NP_389697.1) (22), the protein sequences deduced from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens ynfF (91% identity) (ABS74177.1) (5) and Bacillus pumilus ynfF (86% identity) (ABV62419.1) (15), Aeromonas caviae W-61 endoxylanase (79% identity) (BAA13641.1) (26), and Aeromonas caviae ME-1 xylanase D (78% identity) (AAB63573.1) (33).

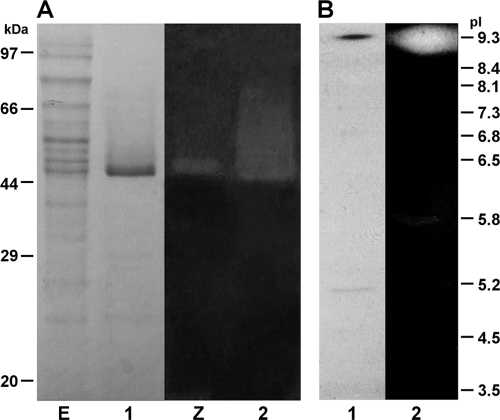

xyn5B was PCR amplified using Pfu polymerase (Stratagene) and cloned as described previously (16) in E. coli BLR(DE3) (Novagen) under the control of promoter T7 from plasmid pET11a. The expressed xylanase was purified to homogeneity from ammonium sulfate-concentrated cell extracts of E. coli BLR(DE3)/pET11a-xynB, after fractionation through gel filtration, anion-exchange chromatography, and cation-exchange chromatography on a fast protein liquid chromatography system (ÄKTA FPLC; GE Healthcare). The purified enzyme was analyzed by SDS-PAGE, isoelectric focusing (IEF), and zymographic analysis, as described previously (13, 23, 34). Purified Xyn5B showed an apparent molecular mass of 48 kDa and a pI of 9.3 (Fig. 1), in accordance with those deduced from the amino acid sequence.

FIG. 1.

Electrophoretic analysis of Xyn5B. (A) SDS-polyacrylamide gel; (B) isoelectric focusing gel. Lanes: 1, protein staining of purified Xyn5B; 2, zymogram of purified Xyn5B; E, protein staining of extracts from E. coli BLR(DE3)/pET11a-xynB; Z, zymogram of extracts from E. coli BLR(DE3)/pET11a-xynB. The positions of molecular mass standards and pI markers are indicated.

Substrate specificity of Xyn5B was determined using xylans, other polysaccharides, and aryl-glycosides, as described previously (3, 30, 34). The enzyme showed high hydrolytic activity on glucuronic acid-branched xylans (glucuronoxylans) from birchwood and beechwood, birchwood being the preferred substrate, with a specific activity of 34 xylanase units/mg. On the contrary, the enzyme did not show any detectable activity on arabinoxylans from oat spelt, rye, and wheat. The enzyme did not show activity on any of the other polysaccharides tested, such as crystalline or amorphous celluloses, pNP-β-d-xylopyranoside (pNPX), or other aryl-glycosides tested like pNPG and pNPAf.

Analysis of the effects of pH and temperature on hydrolytic activity of Xyn5B on birchwood xylan showed that optimal conditions for activity were 55°C and pH 6. The enzyme showed more than 60% of maximum activity in the temperature range from 45 to 65°C at its optimum pH. Thermostability assays revealed that Xyn5B remained highly stable up to 60°C at pH 6 for at least 3 h (data not shown).

Mode of action of Xyn5B.

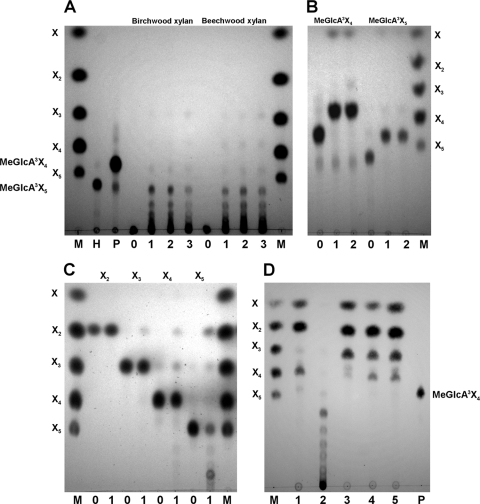

The products released after Xyn5B hydrolysis of glucuronoxylans were analyzed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC), as described previously (14). Birchwood and beechwood xylans were rapidly degraded to a mixture of products of intermediate mobility among linear xylooligosaccharides, indicating that they correspond to xylooligomers substituted with methyl-glucuronic acid (aldouronic acids) (Fig. 2 A).

FIG. 2.

Thin-layer chromatography analysis of the mode of action of Xyn5B. (A) Hydrolysis products from glucuronoxylans. Xyn5B (3.8 μM) was incubated with 1% birchwood or beechwood xylan at 55°C in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 6.0, and samples were taken at times 0 (lanes 0), 15 min (lanes 1), 1 h (lanes 2), or 24 h (lanes 3) and analyzed by TLC. (B) Hydrolysis products from branched xylooligosaccharides. Xyn5B (0.77 μM) was incubated with 7.7 mM aldopentaouronic acid (MeGlcA3Xyl4) or aldohexaouronic acid (MeGlcA3Xyl5) at 55°C in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 6.0, and samples were taken at times 0 (lanes 0), 1 h (lanes 1), or 18 h (lanes 2) and analyzed. (C) Hydrolysis products from linear xylooligosaccharides. Xyn5B was incubated with xylobiose, xylotriose, xylotetraose, or xylopentaose under the same conditions as described above, and samples were taken at times 0 (lanes 0) or 24 h (lanes 1). (D) Products released from glucuronoxylan by the combined action of Xyn5B and Xyn10A. Birchwood xylan (1.5%) was incubated at 50°C in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 6.0, for 18 h with Xyn5B (4.5 μM), Xyn10A (1.5 μM), or with the two enzymes consecutively or simultaneously, and the hydrolysis products were analyzed. Lanes: 1 products of Xyn10A; 2, products of Xyn5B; 3, products of Xyn10A followed by Xyn5B hydrolysis; 4, products of Xyn5B followed by Xyn10A; 5, products of simultaneous incubation with the two enzymes. M, size markers of xylose (X), xylobiose (X2), xylotriose (X3), xylotetraose (X4), and xylopentaose (X5); H, aldohexaouronic acid (MeGlcA3Xyl5); P, aldopentaouronic acid (MeGlcA3X4).

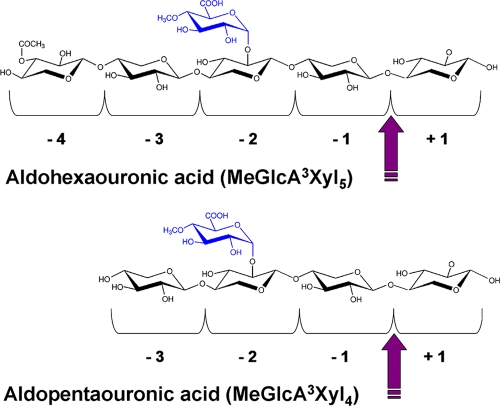

The mode of action of the enzyme on xylooligosaccharides branched with methyl-glucuronic acid was analyzed. Purified Xyn5B hydrolyzed these substrates to xylose plus the corresponding aldouronic acid shortened in one residue (Fig. 2B). In this way, aldopentaouronic acid was hydrolyzed to xylose and aldotetraouronic acid, while hydrolysis of aldohexaouronic acid released xylose and aldopentaouronic acid. The fact that hydrolysis of aldohexaouronic acid did not proceed further than aldopentaouronic acid even after long-term incubations indicates that a different position of the methyl-glucuronic acid branch in the oligosaccharide is required. Thus, while the aldopentaouronic acid used as a substrate has its methyl-glucuronic acid substitution at position 3 from the reducing end (MeGlcA3Xyl4), the aldopentaouronic acid released after hydrolysis of aldohexaouronic acid probably has the substitution at position 2 from the reducing end (MeGlcA2Xyl4), which makes it nonhydrolyzable by the enzyme.

The results obtained are in agreement with the proposed mode of action of GH5 xylanases (32, 39), which release products substituted in the penultimate xylose from the reducing end as a consequence of accommodation of the methyl-glucuronic decorations in the −2 subsite of the catalytic groove of these enzymes (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Schematic representation of cleavage of branched oligomers by Xyn5B. Arrows indicate the bond cleaved on aldohexaouronic or aldopentaouronic acids by the enzyme. −4, −3, −2, −1, and +1 correspond to the subsites of the catalytic groove of the enzyme.

Activity of Xyn5B was also tested on linear xylooligosaccharides up to five xylose units. Xylobiose was not cleaved by the enzyme, while longer oligosaccharides (xylotriose, xylotetraose, and xylopentaose) were hydrolyzed by Xyn5B (Fig. 2C). These substrates rendered xylobiose as major product, with smaller amounts of other xylooligosaccharides. Thin-layer chromatography analysis also revealed that the enzyme exhibited increasing activity on xylooligosaccharides of increasing size, as xylopentaose was degraded faster than xylotetraose, which in turn was degraded more rapidly than xylotriose. The activity shown by Xyn5B on nonsubstituted xylooligomers makes a clear difference with respect to other GH5 xylanases described to date like Erwinia chrysanthemi XynA (18, 39), an enzyme that shows an absolute requirement for methyl-glucuronosyl (MeGlcA) side residues for hydrolysis of xylan and oligosaccharides, and consequently does not degrade linear xylooligosaccharides. The differences in substrate specificity found between Bacillus sp. strain BP-7 Xyn5B and Erwinia chrysanthemi XynA could be justified by their low amino acid sequence identity (39%) (AAB53151.1) (19). On the contrary, GH5 xylanase XynC from Bacillus subtilis (32) shows 92% identity to Xyn5B. However, analysis of activity of Bacillus subtilis XynC on branched or linear xylooligosaccharides has not been reported to date, thus precluding a detailed comparison of the properties of the two enzymes. Two more GH5 xylanases from different Aeromonas caviae strains have also been identified, although the biochemical properties of the cloned enzymes have not been analyzed in detail (26, 33).

Interestingly, activity of Xyn5B on linear xylooligomers gave rise to products of higher degree of polymerization than the starting substrates. These larger compounds could be clearly observed among the products formed from xylopentaose and, to a lesser extent, from xylotetraose. This indicates that the enzyme displays transglycosidase activity on linear xylooligosaccharides.

To gain further knowledge about the mode of action of Xyn5B, the activity of the enzyme on the products released from xylan by a family GH10 xylanase, such as Xyn10A from Paenibacillus barcinonensis (2, 34), was analyzed (Fig. 2D). Birchwood xylan was cleaved by Xyn10A to xylose, xylobiose, and aldotetraouronic acid as the main hydrolysis products in long-term incubations, a typical product pattern of GH10 xylanases (20). When the products of Xyn10A hydrolysis were further incubated with Xyn5B, aldotetraouronic acid disappeared from the hydrolysates and, instead, a spot corresponding to aldotriouronic acid was observed, confirming the results concerning Xyn5B activity on branched oligosaccharides described above. When birchwood xylan was sequentially cleaved in the opposite order, Xyn5B followed by Xyn10A, the main hydrolysis products were xylose, xylobiose, aldotriouronic acid, and aldotetraouronic acid. The presence of aldotriouronic acid among the products released after Xyn10A hydrolysis of the xylooligomers produced by Xyn5B is remarkable, as aldotriouronic acid is not produced by GH10 enzymes (20). This finding is probably related to the structure of the substrates used in our work, compounds released by Xyn5B. These xylooligomers have MeGlcA side chains at the second xylose from the reducing end. These side chains can be accommodated in subsite +1 of the catalytic groove of Xyn10A, a subsite where GH10 xylanases admit decorations (27). This would locate the xylose of the reducing end at subsite +2, leaving an empty +3 subsite. Cleavage of the glycosidic bond located between the −1 and +1 subsites would release aldotriouronic acid (MeGlcA2Xyl2). This type of accommodation leaving an empty +3 subsite seems not to happen with GH10 xylanases acting on polymeric substrates, as production of aldotetraouronic acid (MeGlcA3Xyl3) as the shortest branched product involves accommodation at both the +1 and +3 subsites (20).

Evaluation of Xyn5B in pulp bleaching.

Xyn5B was previously tested in a partial bleaching sequence and compared to GH10 and GH11 xylanases (36). The good results found prompted us to go further with the evaluation of its effectiveness, testing the enzyme in a complete bleaching sequence. Oxygen-delignified Eucalyptus globulus kraft pulp (kappa number, 8.0; ISO [International Organization for Standardization] brightness, 51.1%; viscosity, 972 ± 20 ml g−1; hexenuronic acid contents [HexA], 38.8 ± 0.7 μmol g−1 oven-dried pulp [odp]) from Torraspapel S.A. (Spain) was washed with 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.0) and incubated with xylanase (3 U g−1 odp) at 10% pulp consistency in the same buffer at 50°C for 2 h, prior to a chemical bleaching. An XDEop bleaching sequence was applied, where X is the xylanase pretreatment and D and Eop are the chemical bleaching stages. A D stage with 3% odp of chlorine dioxide as active chlorine at 56°C for 60 min and an Eop stage with 0.3% odp of hydrogen peroxide, 1.1% odp of NaOH, in a pressurized reactor at 500 kPa, at 70°C for 65 min were carried out. When Xyn5B and Xyn11A were applied jointly, 3 U g−1 odp of each enzyme was applied. The kappa number, brightness, viscosity, and hexenuronic acid (HexA) content were determined as described previously (4, 36).

The effect of Xyn5B on kappa number and brightness was determined and compared to that produced by a family GH11 xylanase, Xyn11A from Bacillus sp. strain BP-7 (13), on the same pulps. Xyn5B was effective in boosting delignification and bleaching, as a decrease in kappa number and an increase of brightness were found (Table 1). The effect of Xyn5B was less pronounced than that produced by Xyn11A, which showed higher delignification and bleaching effectiveness. However, when the two enzymes were applied together, a synergistic effect was found in brightness that increased 2.3 ISO units over the control pulp (without enzyme treatment).

TABLE 1.

Properties of XDEop-bleached pulps

| Enzyme(s) | Kappa no. | Brightness (% ISO standard) | HexA concn (μmol/g odp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | 2.9 | 85.9 | 16.1 ± 0.6 |

| Xyn5B | 2.7 | 86.6 | 14.2 ± 1.1 |

| Xyn11A | 2.2 | 86.9 | 12.8 ± 0.6 |

| Xyn5B + Xyn11A | 2.1 | 88.2 | 12.6 ± 0.9 |

The effect of these enzymes on hexenuronic acid (HexA) content was also evaluated. Xylanase-treated pulps showed a decreased HexA content, indicating that xylanases contribute to the removal of these compounds, generated during kraft pulping. Similarly to the results found for delignification and brightness, Xyn5D had a less pronounced effect than Xyn11A in HexA removal (Table 1).

The two xylanases evaluated above belong to the xylan-degrading system of Bacillus sp. strain BP-7, where they probably act coordinately to improve xylan degradation and utilization. Synergistic action among different xylanases on xylan hydrolysis and on bleach boosting has previously been reported (10, 11). The contribution of Xyn5B to the removal of chromophores, lignin, and hexenuronic acids from pulps reveals the potential of GH5 xylanases in pulp bleaching. The preference of Xyn5B for glucuronoxylans makes it a good candidate for the bleaching of hardwood pulps, such as those from Eucalyptus, one of the main raw materials for the pulp industry in temperate regions of the world (31). Further experiments are in progress to understand the mechanism of xylan removal by GH5 xylanases and to optimize their application to paper biotechnology.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The DNA sequence of the xyn5B gene was submitted to GenBank under accession no. BankIt1365134 xyn5B HM594284.

Acknowledgments

We thank Peter Biely for kindly providing aldohexaouronic and aldopentaouronic acids and for scientific advice.

This work was supported in part by the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science, grant CTQ2007-68003-C02-02. Susana Valeria Valenzuela held a MAE AECI doctorate grant from the Spanish Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 July 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bajpai, P. 2004. Biological bleaching of chemical pulps. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 24:1-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanco, A., T. Vidal, J. F. Colom, and F. I. J. Pastor. 1995. Purification and properties of xylanase A from alkali-tolerant Bacillus sp. strain BP-23. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:4468-4470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chai, X. S., J. Y. Zhu, and J. Li. 2001. A simple and rapid method to determine hexenuronic acid groups in chemical pulps. J. Pulp Pap. Sci. 27:165-170. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, X. H., A. Koumoutsi, R. Scholz, A. Eisenreich, et al. 2007. Comparative analysis of the complete genome sequence of the plant growth-promoting bacterium Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42. Nat. Biotechnol. 25:1007-1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christopher, L., S. Bissoon, S. Singh, J. Szendefy, and G. Szakacs. 2005. Bleach-enhancing abilities of Thermomyces lanuginosus xylanases produced by solid state fermentation. Process Biochem. 40:3230-3235. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clarke, J. H., J. E. Rixon, A. Ciruela, H. J. Gilbert, and G. P. Hazlewood. 1997. Family-10 and family-11 xylanases differ in their capacity to enhance the bleachability of hardwood and softwood paper pulps. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 48:177-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins, T., C. Gerday, and G. Feller. 2005. Xylanases, xylanase families and extremophilic xylanases. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 29:3-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins, T., M. A. Meuwis, I. Stals, M. Claeyssens, G. Feller, and C. Gerday. 2002. A novel family 8 xylanase, functional and physicochemical characterization. J. Biol. Chem. 277:35133-35139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Vries, R. P., H. C. M. Kester, C. H. Poulsen, J. A. E. Benen, and J. Visser. 2000. Synergy between enzymes from Aspergillus involved in the degradation of plant cell wall polysaccharides. Carbohydr. Res. 327:401-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elegir, G., M. Sykes, and T. W. Jeffries. 1995. Differential and synergistic action of Streptomyces endoxylanases in prebleaching of kraft pulps. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 17:954-959. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esteghlalian, A. R., M. M. Kazaoka, B. A. Lowery, A. Varvak, B. Hancock, T. Woodward, J. O. Turner, D. L. Blum, D. Weiner, and G. P. Hazlewood. 2008. Prebleaching of softwood and hardwood pulps by a high performance xylanase belonging to a novel clade of glycosyl hydrolase family 11. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 42:395-403. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallardo, O., P. Diaz, and F. I. J. Pastor. 2004. Cloning and characterization of xylanase A from the strain Bacillus sp. BP-7: comparison with alkaline pI-low molecular weight xylanases of family 11. Curr. Microbiol. 48:276-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gallardo, O., F. I. J. Pastor, J. Polaina, P. Diaz, R. Łysek, P. Vogel, P. Isorna, B. González, and J. Sanz-Aparicio. 2010. Structural insights into the specificity of Xyn10B from Paenibacillus barcinonensis and its improved stability by forced protein evolution. J. Biol. Chem. 285:2721-2733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gioia, J., S. Yerrapragada, X. Qin, H. Jiang, et al. 2007. Paradoxical DNA repair and peroxide resistance gene conservation in Bacillus pumilus SAFR-032. PLoS One 2:E928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanahan, D. 1983. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 166:557-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henrissat, B., and G. Davies. 1997. Structural and sequence-based classification of glycoside hydrolases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 7:637-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hurlbert, J. C., and J. F. Preston. 2001. Functional characterization of a novel xylanase from a corn strain of Erwinia chrysanthemi. J. Bacteriol. 183:2093-2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keen, N. T., C. Boyd, and B. Henrissat. 1996. Cloning and characterization of a xylanase gene from corn strains of Erwinia chrysanthemi. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 9:651-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kolenová, K., M. Vršanská, and P. Biely. 2006. Mode of action of endo-β-1,4-xylanases of families 10 and 11 on acidic xylooligosaccharides. J. Biotechnol. 121:338-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kulkarni, N., A. Shendye, and M. Rao. 1999. Molecular and biotechnological aspects of xylanases. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 23:411-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kunst, F., N. Ogasawara, I. Moszer, A. M. Albertini, et al. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the Gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature 390:249-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larson, S. B., J. Day, A. P. Barba de la Rosa, N. T. Keen, and A. McPherson. 2003. First crystallographic structure of a xylanase from glycoside hydrolase family 5: implications for catalysis. Biochemistry 42:8411-8422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.López, C., A. Blanco, and F. I. J. Pastor. 1998. Xylanase production by a new alkali-tolerant isolate of Bacillus. Biotechnol. Lett. 20:243-246. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okai, N., M. Fukasaku, J. Kaneko, T. Tomita, K. Muramoto, and Y. Kamio. 1998. Molecular properties and activity of a carboxyl-terminal truncated form of xylanase 3 from Aeromonas caviae W-91. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 62:1560-1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pell, G., E. J. Taylor, T. M. Gloster, J. P. Turkenburg, C. M. G. A. Fontes, L. M. A. Ferreira, T. Nagy, S. J. Clark, G. J. Davies, and H. J. Gilbert. 2004. The mechanisms by which family 10 glycoside hydrolases bind decorated substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 279:9597-9605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prim, N., F. I. J. Pastor, and P. Diaz. 2001. Cloning and characterization of a bacterial cell-bound type B carboxylesterase from Bacillus sp. BP-7. Curr. Microbiol. 42:237-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sánchez, O. J., and C. A. Cardona. 2008. Trends in biotechnological production of fuel ethanol from different feedstocks. Bioresour. Technol. 99:5270-5295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spiro, R. G. 1966. The Nelson-Somogyi copper reduction method. Analysis of sugars found in glycoprotein. Methods Enzymol. 8:3-26. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stackpole, D. J., R. E. Vaillancourt, M. de Aguigar, and B. M. Potts. 2010. Age trends in genetic parameters for growth and wood density in Eucalyptus globulus. Tree Genet. Genom. 6:179-193. [Google Scholar]

- 32.St. John, F. J., J. D. Rice, and J. F. Preston. 2006. Characterization of XynC from Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis strain 168 and analysis of its role in depolymerization of glucuronoxylan. J. Bacteriol. 188:8617-8626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suzuki, T., K. Ibata, M. Hatsu, K. Takamizawa, and K. Kawai. 1997. Cloning and expression of a 58-kDa xylanase VI gene (xynD) of Aeromonas caviae ME-1 in Escherichia coli which is not categorized as a family F or family G xylanase. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 84:86-89. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Valenzuela, S. V., P. Diaz, and F. I. J. Pastor. 2010. Recombinant expression of an alkali stable GH10 xylanase from Paenibacillus barcinonensis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 58:4814-4818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valls, C., and M. B. Roncero. 2009. Using both xylanase and laccase enzymes for pulp bleaching. Bioresour. Technol. 100:2032-2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valls, C., T. Vidal, O. Gallardo, P. Diaz, F. I. J. Pastor, and M. B. Roncero. 2010. Obtaining low-HexA-content cellulose from eucalypt fibres: which glycosyl hydrolase family is more efficient? Carbohydr. Polym. 80:154-160. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Vleet, J. H., and T. W. Jeffries. 2009. Yeast metabolic engineering for hemicellulosic ethanol production. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 20:300-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Viikari, L., A. Kantelinen, J. Sundquist, and M. Linko. 1994. Xylanases in bleaching: from an idea to the industry. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 13:335-350. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vršanská, M., K. Kolenová, V. Puchart, and P. Biely. 2007. Mode of action of glycoside hydrolase family 5 glucuronoxylan xylanohydrolase from Erwinia chrysanthemi. FEBS J. 274:1666-1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang, J., B. Sun, Y. Cao, Y. Tian, and C. Wang. 2009. Enzymatic preparation of wheat bran xylooligosaccharides and their stability during pasteurization and autoclave sterilization at low pH. Carbohydr. Polym. 77:816-821. [Google Scholar]