Abstract

Uncovering mechanisms that regulate ecdysone production is an important step toward understanding the regulation of insect metamorphosis and processes in steroid-related pathologies. We report here the transcriptome analysis of Drosophila melanogaster dAda2a and dAda3 mutants, in which subunits of the ATAC acetyltransferase complex are affected. In agreement with the fact that these mutations lead to lethality at the start of metamorphosis, both the ecdysone levels and the ecdysone receptor binding to polytene chromosomes are reduced in these flies. The cytochrome genes (spookier, phantom, disembodied, and shadow) involved in steroid conversion in the ring gland are downregulated, while the gene shade, which is involved in converting ecdysone into its active form in the periphery, is upregulated in these dATAC subunit mutants. Moreover, driven expression of dAda3 at the site of ecdysone synthesis partially rescues dAda3 mutants. Mutants of dAda2b, a subunit of the dSAGA histone acetyltransferase complex, do not share phenotype characteristics and RNA profile alterations with dAda2a mutants, indicating that the ecdysone biosynthesis genes are regulated by dATAC, but not by dSAGA. Thus, we provide one of the first examples of the coordinated regulation of a functionally linked set of genes by the metazoan-specific ATAC complex.

The steroid hormone ecdysone (E) controls insect molting and metamorphosis through its timely release into the circulating hemolymph from the prothoracic gland. It is thought that circulating E is converted to the active form, 20-hydroxyecdysone (20E), at the target tissues, where it binds its nuclear receptor (EcR) to elicit specific changes in gene transcription (14, 18, 29, 33). The biosynthesis of 20E from cholesterol is mediated by the P450 cytochrome enzymes (CYPs) encoded by members of the Halloween gene family: spook/Cyp307A1 (spo), spookier/Cyp307A2 (spok), phantom/Cyp306A1 (phm), disembodied/Cyp302A1 (dib), shadow/Cyp315A1 (sad), and shade/Cyp314A1 (shd) (10, 31). The transcriptional changes elicited by EcR require its ligand-dependent dimerization with another nuclear receptor, USP, encoded by ultraspiracle, and lead to the upregulation of the so-called ecdysone-induced genes, most of which encode transcription factors (15, 33). The widespread effects of 20E and steroid hormone signaling in general, including their pathological consequences, justify the search for regulatory mechanisms that could coordinate the multiple transcriptional events resulting from changes in their titers during development (1, 30).

Histone acetyltransferase (HAT) complexes are suitable candidates to mediate this coordination because of their role in the chromatin structural changes required to activate gene transcription (6). HAT complexes acetylate specific lysine (K) residues at the N termini of histones. The recognition that tagging specific residues by acetylation and other types of posttranslational covalent modifications results in changes in transcription has led to the concept of “histone code” as a mechanism to determine specific gene activation (3, 19, 28). Furthermore, some HAT components are also present in transcription factors (TFs), reflecting what is thought to be a sequential transformation of HATs into TFs (11). One class of shared components in several HAT complexes is the ADA (alteration/deficiency in activation) adaptor proteins (2). In Drosophila melanogaster, the HAT complexes dATAC and dSAGA appear to be specific for histones H4 and H3, respectively. dSAGA contains dADA2b, which is required for the acetylation of H3K9 and H3K14, while dATAC contains dADA2a, which is required for the correct acetylation of H4K5 and H4K12 (7, 25). Both HAT complexes, however, share dADA3, and mutants in this adaptor protein show deficient acetylation of H3K9, H3K14, and H4K12, but not H4K5 (12). This suggests that the functional role of dADA3 in the context of acetylation targeting may be different in each HAT complex. Thus, it is important to identify which genes belong to the domain of action of each HAT complex as a function of its ADA components. Studies at this level of gene expression control are particularly relevant because of their pathological implications. In this context, it is significant that mammalian ADA3 binds to the estrogen receptor (ER), recruiting other HAT components, which leads to excessive estrogen-dependent cell proliferation in breast cancer (22). ADA3 also binds to the retinoid X receptor (RXR), where it can be targeted by an oncoprotein of papillomavirus, leading to cervical cancer (9, 20, 35). Indeed, mammalian ADA3 can bind nuclear (ER and RXR), as well as nonnuclear (p53), receptors (24).

In addition to defective acetylation of specific lysines in H3 and H4 histones, loss-of-function mutations in dAda2a and dAda3 cause a sharp lethal phase at the L3/prepupa transition (7, 12, 25). These traits are also exhibited by mutations in dGcn5, the common catalytic subunit of the dATAC and dSAGA HAT complexes, providing the first indication that defective metamorphosis could result from the loss of acetyltransferase activity (5). In contrast, mutations in dAda2b, encoding a component of dSAGA, are able to initiate metamorphosis and show a later lethality phase in pupal stages P4 and P5 (25). Here, we characterize the transcriptional profile of dAda2a, dAda2b, and dAda3 mutants and focus on the experimental analysis of the “Halloween” genes implicated in E biosynthesis. The transcriptional effects of dAda3 are very similar to those of dAda2a and very different from those of dAda2b, indicating that the dATAC, but not the dSAGA, complex regulates this set of genes. While dATAC is indispensable for the transcriptional activation of all genes that are involved in the synthesis of E in the prothoracic gland, it plays a role in the downregulation of the gene that converts E into 20E in the peripheral tissues. This represents an insight into the coordination between production of the prohormone E and its active form, 20E, whose regulated equilibrium determines the normalcy of metamorphosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fly strains.

Cultures were raised at 25°C on standard Drosophila medium. The lethal allele dAda32 has been referred to previously (12) as l(1)7688. The additional dAda3 mutant alleles Δ6 and Δ9 were kindly provided by Pilar Carrera (IGBMC, Strasbourg, France). They were generated by imprecise excision of P{Mae-UAS.6.11}CG7536GG01344, which is located 5′ in the dAda3 coding sequence. Both deletions remove the 5′ end of dAda3 and parts of the second exon of the gene CG7536, within which dAda3 is nested. The alleles dAda2a189 and dAda2b842 have been described previously (25). All mutant alleles were maintained using balancers with markers visible in larval stages. The coding sequence of dAda3 was cloned in the pUAST vector and injected into y w embryos to obtain transgenic lines (UAS-dAda3). Primer sequences used for cDNA cloning are available upon request. The driver phantom-Gal4 was used to overexpress dAda3 in the prothoracic gland. Other fly lines used were obtained from the Drosophila stock center in Bloomington (Fly Base [http://flybase.bio.indiana.edu]). Animals from each genotype (w1118, dAda2a189, dAda2b842, and dAda32) were synchronized for spiracle eversion at the third-instar larval stage before pupariation. For this, 100 larvae were selected at L2-L3 molting within a narrow 30-min interval and kept at 25°C for approximately 45 h. Ten larvae were collected within a 15-min period during spiracle eversion and used for RNA isolation.

Animal harvesting and quantification of ecdysteroid levels.

Eggs of mutant or control fly strains or crosses were collected on agar plates with yeast and kept in an incubator at 25°C and 75% humidity in batches of 2-h egg-laying periods. For the 20E quantitative assays, larvae from either 112 h or 120 h after egg laying (AEL) were classified as mutant or sibling control according to the marker of the balancer chromosomes (either GFP or Tb), washed, shock frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored in high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade methanol for further investigation. For pupae, careful staging was achieved by collecting white prepupae hourly for 12 consecutive hours. Each harvest included experimental and control genotypes in order to ensure an objective developmental age. Ecdysteroid levels were quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), following the procedure previously described (26) and further adapted (27). 20E (Sigma) and 20E-acetylcholinesterase (Cayman Chemical) were used as the standard and enzymatic tracer, respectively. The ecdysteroid antiserum (Cayman Chemical) was used at a dilution of 1:50,000. Absorbance was read at 450 nm using a Multiscan Plus II Spectrophotometer (Labsystems). The antiserum has the same affinity for ecdysone as for 20E (26), but because the standard curve was obtained with the latter compound, the results are expressed as 20E equivalents. For sample preparation, 15 to 20 staged larvae and pupae were weighed and preserved in 600 μl of methanol. Prior to the assay, samples were homogenized and centrifuged (10 min at 18,000 × g) twice, and the resulting methanol supernatants were combined and dried. Samples were resuspended in 50 μl of enzyme immunoassay (EIA) buffer (0.4 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% bovine serum albumin [BSA] in 0.1 M phosphate buffer).

DNA microarrays.

Total RNA was isolated from groups of 10 larvae using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). Hybridization was performed on a Drosophila 2 microarray plate, and scanning was performed at the Institut de Génétique et de Biologie Moléculaire et Cellulaire (IGBMC) DNA CHIP Facility following the recommended standard Affymetrix protocols. Three biological replicates for each genotype (w1118, dAda2a189, dAda32, and dAda2b189) were analyzed. The genes with a “present” call in at least two samples were included in the statistical analysis.

QRT-PCR assays.

For the quantitative determination of transcripts of the early-response ecdysone genes w1118 and dAda3, larvae were staged at late third-instar stage, and total RNAs were isolated with an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg RNA using a First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Amersham Bioscience). Quantitative real-time PCR (QRT-PCR) was performed (ABI7500 RT-PCR System) using primers specific for the respective cDNAs and 18S rRNA as an internal control, following the incorporation of SYBR green or using TaqMan probes (Table 1). CT values were set against a calibration curve. The ΔΔCT method was used for the calculation of the relative abundances (32). Primers were designed using Primer Express software (ABI). The sequences of primers BR-C, Eig74A, and Eig 75B have been described previously (7).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used as PCR primers for plasmid construction and for the determination of RNA levels by QRT-PCR

| Primer | Direction | Sequence (5′→3′) |

|---|---|---|

| spo | Forward | TATCTCTTGGGCACACTCGCTG |

| Reverse | GCCGAGCTAAATTTCTCCGCTT | |

| phm | Forward | GGATTTCTTTCGGCGCGATGTG |

| Reverse | TGCCTCAGTATCGAAAAGCCGT | |

| dib | Forward | TGCCCTCAATCCCTATCTGGTC |

| Reverse | ACAGGGTCTTCACACCCATCTC | |

| sad | Forward | CCGCATTCAGCAGTCAGTGG |

| Reverse | ACCTGCCGTGTACAAGGAGAG | |

| shd | Forward | CGGGCTACTCGCTTAATGCAG |

| Reverse | AGCAGCACCACCTCCATTTC | |

| mld | Forward | AGCAGCGATAATGCCGTCGACT |

| Reverse | ACACATTTCCGCCGGAACTTGG | |

| ptth | Forward | CACTCCACATCCCACAGAGATGGCGATG |

| Reverse | GTAACTGCCGGCTGCTTCTGCACAA | |

| nvd | Forward | GGAAGCGTTGCTGACGACTGTG |

| Reverse | TAAAGCCGTCCACTTCCTGCGA | |

| usp | Forward | CAGTATCCGCCTAACCATCC |

| Reverse | TTCCTCTGCCGCTTGTCTAT | |

| ecd | Forward | CTGGCGGAGTTCTTAGATCG |

| Reverse | GCATGGAGGGATTCTTCTTG | |

| BR-C | Forward | GCCCTGGTGGAGTTCATCTA |

| Reverse | CAGATGGCTGTGTGTGTCCT | |

| Eig74A | Forward | GTTGCCGGAACATTATGGAT |

| Reverse | ATCAGCCGAACATTATGGAT | |

| Eig75B | Forward | GCGGTCCAGAATCAGCAG |

| Reverse | GAGGATGTGGAGGAGGATGA | |

| RpII 140 | Forward | ACTGAAATCATGATGTACGACAACGA |

| Reverse | TGAGAGATCTCCTCGGCATTCT | |

| TaqMan | TCCTCGTACAGTTCTTCC | |

| Eig78C | Forward | GCGCCAGCAGCTTGAG |

| Reverse | CGTGTTGGCAAAGTTCAGCAA | |

| TaqMan | ACTCTACGATTCTGACTTTGTC | |

| Eig71EA | Forward | CTACAATAATGCGCCTGAAAACAGT |

| Reverse | GATCTTGACCAGCAACCAGAGT | |

| TaqMan | CATCTTTTTCGCCATATCGC | |

| EcRA | Forward | CGAACAAAAGACCGCGACTT |

| Reverse | GCCTGGACTAGGAGTGGACAT | |

| TaqMan | CAGTCCTCGGTAACATC | |

| E74-ex8 | Forward | TGTCCGCGTTTCATCAAGT |

| Reverse | GTTCATGTCCGGCTTGTTCT | |

| E75-ex8 | Forward | CAACTGCACCACCACTTGAC |

| Reverse | GCCTTGCACTCGTTCTTCTC | |

| Rp49 | Forward | AGCGCACCAAGCACTTCATC |

| Reverse | GACGCACTCTGTTGTCGATACC |

To measure the responses of ecdysone-induced genes to 20E treatment in matched larval samples, salivary glands were dissected from homozygous dAda2a189, dAda32, or heterozygous control larvae 36 h after the L2-L3 molt. The two glands were separated and incubated for 2 h at 25°C in Schneider's insect medium (Sigma) containing either 20 μM 20E (Sigma) or ethanol vehicle only. Total RNA was prepared using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). First-strand cDNA was synthesized with TaqMan Reverse Transcription Reagent (ABI) using random hexamer primers after DNase I (Fermentas) treatment of the RNA samples. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed with gene-specific primers (E74-ex8 and E75-ex8) (Table 1) in an ABI 7500 RT-PCR System using Power SYBR green PCR Mastermix (ABI). Transcript levels of ecdysone response genes were quantitated by setting the CT values against a calibration curve and normalizing to the expression level of the Rp49 housekeeping gene. The level of induction upon 20E treatment was determined by comparing the matched samples.

The primer sequences used to detect transcript levels of Halloween genes are shown in Table 1. For validation of microarray data, QRT-PCRs were performed in duplicate on three independent samples using primers specific for the respective cDNAs (21) and 18S rRNA as an internal control. CT values were set against a calibration curve. The ΔΔCT method was used for the calculation of the relative abundances.

Ecdysone and cholesterol feeding assay.

For ecdysone treatment, larvae were synchronized at the second to third larval molting, collected 24 h later at the middle L3 stage, and transferred into new vials. A 5-mg/ml 20E stock was diluted with 60% ethanol and added to standard medium at 0.5 mM 20E final concentration. The control contained solvent only. For cholesterol feeding, 30 staged larvae were collected and placed into glass vials containing either standard food or food plus cholesterol at a final concentration of 0.14 mg/g (16). The experiments were conducted blind; larval development was monitored at 25°C, and the lethal phase was noted.

Cholesterol transport assay.

For Filipin staining, tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature (RT), washed 3 times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and stained with 50 μg/ml Filipin (Sigma) for 45 min at RT, followed by 2 washes in PBS (17). The samples were mounted on Vectashield mounting medium, and pictures were taken using an Olympus FV1000 confocal microscope.

Ring gland staining and quantification of polytene cells.

Synchronized larvae at the middle of L3 stage were collected, and the brains, together with the ring gland, were dissected in PBS. The samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at RT, followed by 2 washes in PBS supplemented with 0.3% Tween 20. 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was added to the samples for 10 min at RT, followed by 2 washes in PBS. The samples were mounted on Vectashield mounting medium, and pictures were taken using an Olympus FV1000 confocal microscope. The polytene cells were counted in 10 ring glands for each genotype.

RESULTS

Ecdysone levels are reduced in dATAC mutants.

The ecdysteroid hormone 20E acts as a major regulator of Drosophila development, controlling almost all developmental transitions. Thus, at the end of larval development, a pulse of 20E induces puparium formation, and a second peak, approximately 10 h after the formation of the puparium, signals the prepupal-pupal transition. Since dAda2a and dAda3 mutants have their lethal phase at metamorphosis, we decided to measure the ecdysteroid levels in these mutants (Fig. 1A). The data show that at 112 h AEL, the ecdysteroid titers in dAda3 and dAda2a mutants were significantly reduced compared to their respective sibling controls. In contrast, no significant differences were observed between dAda2b heterozygotes and null mutants. Ecdysteroid levels of dAda2a and dAda3 mutants were maintained slightly lower than their controls at 120 h AEL and during pupation (data not shown). To further analyze the molecular mechanism that causes the phenotype of either the dAda2a or the dAda3 mutant, we analyzed the binding of the 20E nuclear receptor, EcR, to DNA by immunostaining polytene chromosomes with an antibody that recognizes all EcR isoforms. We found that the in situ localization of EcR to chromosomes is severely reduced in both dAda2a and dAda3 mutants (Fig. 1B; see also Fig. 4E in reference 7).

FIG. 1.

dATAC mutants have reduced ecdysteroid levels. (A) Ecdysteroid titers measured for different mutant genotypes (dAda3, dAda2a, and dAda2b) and their corresponding sex-matched sibling controls (FM7i, and TM6 and Tb) at 112 h AEL, as determined by ELISA. The values are expressed as the means of 20E equivalents per mg of larvae. The error bars indicate the standard errors of the mean (SEM) (n = 3 samples of 15 larvae each). The asterisks indicate statistically significant differences at P ≤ 0.006 (t test). (B) EcR immunostaining of polytene chromosomes from dAda32 and control larvae. Note the reduction of EcR signal in the mutant (similarly reduced EcR binding to chromosomes can be observed in dAda2a mutants [7]).

FIG. 4.

mRNA levels of ecdysone (ecd)- related genes in dAda3 mutants. The mRNA levels were determined by QRT-PCR using TaqMan probes. The results of three independent experiments are shown as ratios between mutant (dAda32) and control (w1118). In addition to the EcR isoforms and USP (A), representative early ecdysone-induced genes (Eig) (B) were included in these sets of assays. The error bars indicate the SEM.

Mutations in several subunits of dATAC change the expression of ecdysone-regulated genes.

Decreased levels of ecdysteroids and EcR binding to chromosomes can cause transcription failures in a number of vital genes. Lethality at the initiation of metamorphosis, however, could also be a secondary effect of defective regulation of genes positioned anywhere along the 20E-mediated gene regulatory hierarchy. In order to gain information on the complete set of dATAC targets, we analyzed total transcriptional profiles in several dAda mutants.

For gene expression profile comparisons, we performed microarray hybridization of total RNA samples obtained from dAda2a189, dAda32, dAda2b842, and w1118 late third-instar larvae to Affymetrix Drosophila total genome microarrays. All hybridizations were performed in triplicate using RNA samples obtained from groups of 10 L3 stage larvae synchronized to spiracle eversion (microarray data are available at http://www.ebi.ac.uk/microarray-as/ae/, referred to as E-MEXP-2765 [dAda32 and dAda2a189] or E-MEXP-2125 and E-MEXP-2126 [dAda2b842]). The analysis of dAda2b samples has been described recently (37). In dAda2a and dAda3 mutants, we found a very high fraction of genes either down- or upregulated. Out of the 18,000 transcripts detected at late L3, the levels of 4,737 and 2,912 were decreased to less than 50% of the control in dAda2a and dAda3 mutants, respectively (Fig. 2A). Somewhat fewer, but still a very high number of genes (2,569 and 2,653 RNAs) were upregulated at least 2-fold in dAda2a and dAda3 mutants, respectively, compared to controls. In contrast, the number of affected genes in the dSAGA-specific dAda2b mutants was lower by an order of magnitude. Although a large number of genes were affected in dAda2a and dAda3 mutants, the two large sets of genes correlated in both the types of genes affected and the magnitude of the expression changes (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Transcriptional changes in dADA mutants. (A) Venn diagrams showing the numbers of activated or repressed genes in dAda2b, dAda3, or dAda2a mutant larva. (B) Distribution of genes with different expression patterns compared to the control in the absence of dAda2a and dAda3. The genes were categorized based on the level of changes (in log2 scale) in their expression.

The expression changes of genes affected by dAda2a and dAda3 mutations revealed coregulation with either increased or decreased levels, as shown among the genes involved in cuticle formation or among those activated by ecdysone (Fig. 3A and B). Some of these changes clearly resulted from, and reflected, a delay in mutant development. This could explain the overall increased level of messages of larval cuticle proteins. Similar changes were observable in the levels of genes encoding proteins involved in chitin metabolic processes and to a lesser extent in the levels of mRNAs of ribosomal, mitochondrial, and cytochrome enzymes (Fig. 3C and data not shown). On the other hand, genes involved in compound-eye development were downregulated, and similarly, but for a less obvious reason, a decrease in the levels of most of the genes of proteasome subunits was detectable in the mutants (Fig. 3D and data not shown). Significantly, most of the genes known to be under the control of 20E were downregulated in dAda2a and dAda3 mutants (Fig. 3B and Table 2). The microarray data also indicated drastic changes—up to 1,000-fold decrease—in the levels of 20E primary and secondary response genes. A less dramatic, but significant, decrease was observable in the level of EcR expression and, significantly, that of a number of genes involved in 20E metabolism. In view of these suggestive indications from the microarray data, we focused on the genes belonging to the 20E-regulated pathway to validate the apparent transcriptional effects.

FIG. 3.

Gene expression changes in ATAC mutants show tight coordination. The scatter plots show gene expression changes in dAda2a- and dAda3-null animals as detected by microarray hybridization. The mRNA levels (log2) of genes involved in cuticle formation (A), regulated by ecdysone (B), and encoding cytochrome enzymes (C) and proteasome subunits (D) are plotted.

TABLE 2.

Expression changes of selected ecdysone-related genes in dAda2a, dAda3, and dAda2b mutantsa

| Gene symbol | Gene name | Expression level |

log2 expression change |

P value (t test) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| w1118 | Ada2a189 | Ada32 | Ada2b842 | Ada2a189 | Ada32 | Ada2b842 | P(Ada2a) | P(Ada3) | P(Ada2b) | ||

| PTTH hormone: Ptth | Prothoracicotropic hormone | 19 | 19 | 21 | 17 | 0.0 | 0.2 | −0.1 | 4.6E−01 | 1.4E−01 | 1.2E−01 |

| Ring gland PG cells PTTH activated (G-protein) cascade members | |||||||||||

| CG40190 | MAP kinase | 461 | 293 | 208 | 411 | −0.7 | −1.1 | −0.2 | 2.0E−02 | 3.1E−03 | 3.8E−01 |

| chico | Flipper | 122 | 115 | 126 | 118 | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 3.2E−01 | 3.7E−01 | 4.4E−01 |

| Dsor1 | Downstream of raf1 | 93 | 62 | 63 | 85 | −0.6 | −0.6 | −0.1 | 5.8E−03 | 4.8E−03 | 4.5E−01 |

| eIF-4E | Eukaryotic initiation factor 4E | 1,199 | 1,130 | 1,105 | 1,102 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 1.7E−01 | 4.6E−02 | 2.1E−01 |

| Mekk1 | Mekk1 | 104 | 198 | 166 | 131 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 8.7E−03 | 1.4E−02 | 3.2E−01 |

| phl | Pole hole | 112 | 63 | 55 | 98 | −0.8 | −1.0 | −0.2 | 1.5E−02 | 7.8E−03 | 4.9E−01 |

| Pten | Pten | 134 | 53 | 64 | 124 | −1.3 | −1.1 | −0.1 | 1.9E−05 | 1.0E−04 | 3.6E−01 |

| Ras85D | Ras GTPase | 987 | 347 | 373 | 1,008 | −1.5 | −1.4 | 0.0 | 1.4E−04 | 8.3E−05 | 2.0E−01 |

| RpS6 | Ribosomal protein S6 | 3,886 | 3,900 | 3,626 | 3,641 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 4.8E−01 | 2.0E−01 | 1.3E−01 |

| Tor | Target-of-rapamycin | 100 | 68 | 76 | 116 | −0.6 | −0.4 | 0.2 | 4.1E−02 | 6.7E−02 | 8.9E−02 |

| Cholesterol uptake | |||||||||||

| NPC1 | Niemann-Pick type C-1 | 496 | 131 | 128 | 398 | −1.9 | −2.0 | −0.3 | 2.8E−06 | 1.4E−06 | 4.6E−01 |

| NPC2 | Epididymal secretory protein | 1,866 | 439 | 560 | 1,696 | −2.1 | −1.7 | −0.1 | 4.0E−05 | 4.7E−05 | 3.4E−01 |

| Start1 | Start1 | 383 | 104 | 119 | 383 | −1.9 | −1.7 | 0.0 | 6.9E−05 | 7.1E−05 | 2.3E−01 |

| Ecdysone biosynthesis (enzymes and woc transcription factor) | |||||||||||

| dare | ADXRDTASE | 44 | 64 | 97 | 49 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 6.5E−03 | 1.5E−04 | 4.7E−01 |

| dib | Disembodied | 9 | 8 | 10 | 3 | ||||||

| ecd | Ecdysoneless | 138 | 53 | 63 | 120 | −1.4 | −1.1 | −0.2 | 3.8E−03 | 4.7E−03 | 4.4E−01 |

| mld | Molting defective | 142 | 49 | 46 | 155 | −1.5 | −1.6 | 0.1 | 3.1E−02 | 2.3E−02 | 2.0E−01 |

| phm | Phantom | 84 | 19 | 21 | 62 | −2.1 | −2.0 | −0.4 | 4.6E−03 | 5.3E−03 | 4.1E−01 |

| sad | Shadow | 103 | 5 | 6 | 95 | −4.5 | −4.1 | −0.1 | 1.5E−03 | 1.5E−03 | 3.3E−01 |

| shd | Shade | 79 | 162 | 153 | 114 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 4.9E−03 | 1.6E−02 | 2.7E−01 |

| spo | spook | 6 | 1 | 1 | 5 | −2.1 | −2.3 | −0.1 | 5.2E−02 | 3.8E−02 | 3.7E−01 |

| woc | Without children | 314 | 141 | 146 | 284 | −1.2 | −1.1 | −0.1 | 2.2E−03 | 2.4E−03 | 4.0E−01 |

| Genes expressed in the ring gland (transcription factors) | |||||||||||

| ap | Xasta | 178 | 40 | 30 | 138 | −2.2 | −2.6 | −0.4 | 2.4E−06 | 1.9E−06 | 4.5E−01 |

| cpo | Couch potato | 28 | 12 | 19 | 21 | −1.2 | −0.6 | −0.4 | 4.3E−02 | 1.2E−01 | 4.3E−01 |

| crc | Cryptocephal | 2,493 | 2,218 | 1,969 | 2,248 | −0.2 | −0.3 | −0.1 | 7.2E−02 | 7.1E−03 | 7.1E−02 |

| crol | Crooked legs | 223 | 69 | 56 | 246 | −1.7 | −2.0 | 0.1 | 3.6E−04 | 2.2E−04 | 1.4E−01 |

| EcR | Ecdysone receptor | 58 | 55 | 84 | 67 | −0.1 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 3.7E−01 | 5.5E−03 | 2.0E−01 |

| Eip74EF | Ecdysone-inducible protein | 639 | 118 | 208 | 1,170 | −2.4 | −1.6 | 0.9 | 3.2E−04 | 3.4E−04 | 4.0E−03 |

| Eip75B | Ecdysone-induced protein 75B | 157 | 59 | 66 | 180 | −1.4 | −1.2 | 0.2 | 2.7E−02 | 3.4E−02 | 1.6E−01 |

| Eip75B | Ecdysone-induced protein 75B | 109 | 19 | 20 | 99 | −2.5 | −2.5 | −0.1 | 9.8E−04 | 1.1E−03 | 3.5E−01 |

| gl | Glass | 27 | 4 | 3 | 18 | −2.8 | −3.2 | −0.5 | 1.2E−03 | 5.2E−04 | 3.0E−01 |

| Gsc | Muenster 72 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 7 | −0.3 | −0.4 | −0.1 | 2.1E−01 | 2.6E−01 | 3.8E−01 |

| gt | Giant | 3 | 6 | 3 | 5 | ||||||

| Hr4 | Hr4 | 14 | 6 | 4 | 24 | −1.3 | −1.9 | 0.8 | 4.4E−02 | 3.3E−02 | 1.5E−02 |

| Hr46 | Complementation group D | 60 | 0 | 1 | 62 | −8.5 | −5.6 | 0.0 | 2.3E−05 | 2.7E−05 | 2.1E−01 |

| per | Period | 6 | 4 | 6 | 8 | ||||||

| retn | Dead ringer | 43 | 14 | 18 | 47 | −1.6 | −1.3 | 0.1 | 2.3E−02 | 3.4E−02 | 2.0E−01 |

| sbb | Scribble | 296 | 70 | 75 | 292 | −2.1 | −2.0 | 0.0 | 8.5E−03 | 9.4E−03 | 2.9E−01 |

| so | Medusa | 29 | 14 | 20 | 32 | −1.0 | −0.6 | 0.1 | 1.5E−02 | 5.3E−02 | 1.8E−01 |

| srp | A-box-binding factor | 503 | 177 | 164 | 402 | −1.5 | −1.6 | −0.3 | 4.7E−04 | 4.0E−04 | 4.4E−01 |

| tim | Timeless | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | ||||||

| ttk | Tramtrack-69 | 292 | 125 | 117 | 265 | −1.2 | −1.3 | −0.1 | 4.5E−03 | 3.2E−03 | 3.8E−01 |

| Genes expressed in the ring gland (other genes) | |||||||||||

| Akh | Adipokinetic hormone | 29 | 27 | 38 | 31 | ||||||

| ap | Xasta | 178 | 40 | 30 | 138 | −2.2 | −2.6 | −0.4 | 2.4E−06 | 1.9E−06 | 4.5E−01 |

| betaTub60D | Beta-tubulin | 2,398 | 212 | 425 | 1,717 | −3.5 | −2.5 | −0.5 | 1.6E−05 | 3.5E−05 | 4.2E−01 |

| brat | Brain tumor | 215 | 33 | 32 | 285 | −2.7 | −2.8 | 0.4 | 9.1E−05 | 9.1E−05 | 6.3E−02 |

| Cam | Calmodulin | 1,928 | 2,520 | 2,151 | 1,705 | 0.4 | 0.2 | −0.2 | 7.8E−03 | 7.4E−02 | 7.6E−02 |

| dawdle | dActivin2 | 210 | 164 | 187 | 201 | −0.4 | −0.2 | −0.1 | 6.9E−02 | 2.4E−01 | 4.1E−01 |

| dpp | Shortvein | 67 | 35 | 47 | 59 | −1.0 | −0.5 | −0.2 | 9.7E−04 | 3.4E−03 | 4.9E−01 |

| ecd | Ecdysoneless | 138 | 53 | 63 | 120 | −1.4 | −1.1 | −0.2 | 3.8E−03 | 4.7E−03 | 4.4E−01 |

| Ef1alpha48Ds | Elongation factor 1-alpha F1 | 5,820 | 6,509 | 5,811 | 5,646 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.5E−02 | 4.9E−01 | 1.7E−01 |

| Eip63E | Pftaire | 480 | 26 | 214 | 671 | −4.2 | −1.2 | 0.5 | 4.3E−06 | 2.3E−05 | 4.1E−02 |

| Fmr1 | Fragile X | 254 | 100 | 91 | 243 | −1.3 | −1.5 | −0.1 | 5.5E−04 | 3.4E−04 | 3.0E−01 |

| Gprk2 | G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 | 143 | 54 | 64 | 93 | −1.4 | −1.2 | −0.6 | 6.8E−05 | 1.2E−04 | 1.8E−01 |

| hdc | Fusion-6 | 85 | 45 | 86 | 92 | −0.9 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.3E−01 | 4.9E−01 | 2.7E−01 |

| mr | Morula | 70 | 47 | 62 | 69 | −0.6 | −0.2 | 0.0 | 9.2E−03 | 2.0E−02 | 2.8E−01 |

| msn | Mishapen | 526 | 127 | 102 | 409 | −2.0 | −2.4 | −0.4 | 4.1E−04 | 3.2E−04 | 4.6E−01 |

| NPC1 | Niemann-Pick type C-1 | 496 | 131 | 128 | 398 | −1.9 | −2.0 | −0.3 | 2.8E−06 | 1.4E−06 | 4.6E−01 |

| Nrg | Neuroglian | 216 | 243 | 176 | 169 | 0.2 | −0.3 | −0.4 | 3.3E−01 | 1.8E−01 | 1.3E−01 |

| Pigment-dispersing factor | 17 | 18 | 7 | 15 | 0.0 | −1.2 | −0.2 | 4.5E−01 | 2.9E−02 | 2.5E−01 | |

| Phm | Peptidyl glycine alpha hydroxylating monooxygenase | 331 | 231 | 296 | 376 | −0.5 | −0.2 | 0.2 | 2.3E−03 | 7.4E−02 | 4.5E−02 |

| Pi3K92E | PI 3-kinase | 263 | 143 | 179 | 320 | −0.9 | −0.6 | 0.3 | 7.4E−03 | 1.8E−02 | 7.3E−02 |

| Pka-C1 | Protein kinase A | 70 | 157 | 81 | 91 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 8.0E−03 | 2.8E−01 | 3.9E−01 |

| Ras85D | Ras GTPase | 987 | 347 | 373 | 1,008 | −1.5 | −1.4 | 0.0 | 1.4E−04 | 8.3E−05 | 2.0E−01 |

| sog | Short gastrulation | 5 | 7 | 6 | 11 | ||||||

| spin | Spinster | 285 | 188 | 193 | 244 | −0.6 | −0.6 | −0.2 | 4.4E−04 | 5.8E−04 | 3.5E−01 |

| Traf1 | TNF-receptor-associated factor 1 | 133 | 28 | 38 | 106 | −2.2 | −1.8 | −0.3 | 1.9E−04 | 3.0E−04 | 5.0E−01 |

| TrpA1 | Transient receptor potential A1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 7 | ||||||

| Vha16 | Ductin | 1,138 | 2,670 | 1,881 | 1,044 | 1.2 | 0.7 | −0.1 | 5.5E−06 | 6.8E−04 | 1.7E−01 |

| wit | Wishful thinking | 90 | 89 | 93 | 103 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 4.7E−01 | 3.2E−01 | 1.8E−02 |

| Receptors | |||||||||||

| EcR | Ecdysone receptor | 58 | 55 | 84 | 67 | −0.1 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 3.7E−01 | 5.5E−03 | 2.0E−01 |

| Hr38 | Hormone receptor-like in 38 | 3 | 27 | 25 | 5 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 5.1E−03 | 3.2E−04 | ||

| usp | Ultraspiracle | 188 | 81 | 106 | 189 | −1.2 | −0.8 | 0.0 | 3.3E−04 | 3.2E−04 | 2.2E−01 |

| Ecdysone-inducible genes and receptor signaling | |||||||||||

| alt | CG18212 | 489 | 170 | 142 | 764 | −1.52 | −1.79 | 0.64 | 3.1E−04 | 3.0E−05 | 7.9E−03 |

| Art4 | Arginine methyltransferase 4 | 168 | 83 | 117 | 158 | −1.0 | −0.5 | −0.1 | 9.8E−04 | 1.0E−02 | 3.6E−01 |

| Atg1 | I(3)00305 | 358 | 75 | 87 | 577 | −2.3 | −2.0 | 0.7 | 1.6E−03 | 1.8E−03 | 2.2E−02 |

| b | Black | 2,820 | 20 | 23 | 3,129 | −7.1 | −7.0 | 0.1 | 1.8E−06 | 1.9E−06 | 1.4E−01 |

| bchs | Beached | 95 | 19 | 30 | 139 | −2.3 | −1.7 | 0.5 | 2.2E−03 | 4.1E−03 | 3.1E−02 |

| bib | Big brain | 116 | 5 | 7 | 114 | −4.6 | −4.1 | 0.0 | 5.1E−04 | 5.4E−04 | 2.5E−01 |

| Blimp-1 | Blimp-1 | 34 | 10 | 16 | 50 | −1.7 | −1.1 | 0.6 | 5.2E−03 | 1.1E−02 | 2.6E−02 |

| br | Broad complex | 407 | 17 | 21 | 435 | −4.6 | −4.3 | 0.1 | 5.6E−04 | 5.6E−04 | 1.8E−01 |

| br | Broad complex | 912 | 95 | 106 | 1,137 | −3.3 | −3.1 | 0.3 | 2.0E−03 | 2.1E−03 | 9.3E−02 |

| br | Broad complex | 163 | 25 | 27 | 197 | −2.7 | −2.6 | 0.3 | 3.8E−03 | 4.1E−03 | 1.1E−01 |

| br | Broad complex | 110 | 17 | 14 | 105 | −2.7 | −2.9 | −0.1 | 1.6E−02 | 1.5E−02 | 3.3E−01 |

| br | Broad complex | 86 | 16 | 16 | 86 | −2.4 | −2.4 | 0.0 | 5.0E−02 | 4.9E−02 | 3.3E−01 |

| cbt | Cabut | 424 | 684 | 578 | 317 | 0.7 | 0.4 | −0.4 | 6.2E−03 | 1.1E−02 | 1.4E−02 |

| CG10444 | CG10444 | 308 | 168 | 182 | 451 | −0.9 | −0.8 | 0.6 | 2.4E−04 | 4.8E−04 | 1.2E−02 |

| CG11509 | CG11509 | 167 | 11 | 7 | 212 | −3.90 | −4.53 | 0.34 | 2.1E−03 | 1.9E−03 | 8.9E−02 |

| CG11529 | CG11529 | 157 | 92 | 23 | 622 | −0.76 | −2.77 | 1.99 | 7.5E−02 | 7.7E−03 | 5.1E−05 |

| CG11737 | CG11737 | 500 | 82 | 82 | 558 | −2.60 | −2.61 | 0.16 | 8.0E−04 | 7.8E−04 | 1.4E−01 |

| CG12539 | CG12539 | 127 | 1 | 1 | 194 | −6.57 | −6.44 | 0.61 | 3.3E−04 | 3.3E−04 | 3.9E−02 |

| Ecdysone-inducible genes and receptor signaling | |||||||||||

| CG13252 | CG13252 | 1,054 | 261 | 226 | 1,305 | −2.01 | −2.22 | 0.31 | 6.1E−05 | 5.2E−05 | 6.2E−02 |

| CG1342 | CG1342 | 2,463 | 5 | 6 | 1,363 | −8.83 | −8.71 | −0.85 | 9.2E−05 | 9.2E−05 | 2.7E−01 |

| CG14073 | Nirvana | 122 | 36 | 50 | 164 | −1.76 | −1.30 | 0.42 | 8.1E−04 | 1.7E−03 | 4.7E−02 |

| CG15287 | CG15287 | 28 | 9 | 24 | 36 | −1.70 | −0.22 | 0.37 | 1.1E−02 | 2.5E−01 | 1.7E−01 |

| CG16995 | CG16995 | 86 | 48 | 107 | 139 | −0.83 | 0.32 | 0.69 | 3.2E−03 | 1.3E−01 | 1.2E−02 |

| CG17834 | CG17834 | 177 | 90 | 100 | 171 | −0.97 | −0.83 | −0.05 | 1.4E−03 | 2.1E−03 | 3.0E−01 |

| CG2016 | CG2016 | 1,041 | 17 | 22 | 438 | −5.92 | −5.57 | −1.25 | 8.1E−05 | 8.3E−05 | 1.6E−01 |

| CG2444 | CG2444 | 4,817 | 118 | 284 | 5,047 | −5.35 | −4.09 | 0.07 | 8.0E−06 | 9.7E−06 | 1.8E−01 |

| CG30015 | CG30015 | 327 | 161 | 146 | 419 | −1.02 | −1.16 | 0.36 | 7.6E−03 | 5.4E−03 | 4.8E−02 |

| CG33090 | CG33090 | 33 | 75 | 81 | 37 | 1.18 | 1.28 | 0.16 | 2.3E−03 | 1.6E−04 | 3.8E−01 |

| CG3348 | CG3348 | 112 | 2,081 | 1,967 | 186 | 4.21 | 4.13 | 0.73 | 7.9E−07 | 2.8E−05 | 2.5E−01 |

| CG3714 | CG3714 | 302 | 193 | 153 | 369 | −0.64 | −0.98 | 0.29 | 1.5E−03 | 1.3E−04 | 3.3E−02 |

| CG4822 | CG4822 | 735 | 57 | 50 | 756 | −3.69 | −3.87 | 0.04 | 2.7E−06 | 2.6E−06 | 2.0E−01 |

| CG5171 | CG5171 | 4,156 | 80 | 65 | 4,348 | −5.69 | −6.00 | 0.07 | 7.2E−05 | 7.1E−05 | 1.8E−01 |

| CG5391 | CG5391 | 434 | 277 | 69 | 1,504 | −0.65 | −2.65 | 1.79 | 4.0E−02 | 2.9E−05 | 1.7E−05 |

| CG8483 | CG8483 | 1,001 | 142 | 131 | 500 | −2.81 | −2.93 | −1.00 | 1.4E−04 | 4.0E−05 | 1.9E−01 |

| CG8501 | CG8501 | 1,245 | 161 | 387 | 1,235 | −2.95 | −1.69 | −0.01 | 3.8E−05 | 1.0E−04 | 2.3E−01 |

| CG8788 | CG8788 | 1,763 | 255 | 294 | 1,223 | −2.79 | −2.58 | −0.53 | 7.5E−04 | 8.2E−04 | 3.8E−01 |

| CG9005 | CG9005 | 337 | 35 | 57 | 405 | −3.28 | −2.56 | 0.27 | 8.8E−05 | 1.2E−04 | 9.2E−02 |

| CG9192 | CG9192 | 47 | 11 | 12 | 107 | −2.07 | −1.97 | 1.19 | 3.3E−04 | 4.7E−04 | 6.6E−03 |

| CG9801 | CG9801 | 1,028 | 37 | 67 | 756 | −4.80 | −3.93 | −0.44 | 3.8E−05 | 4.3E−05 | 4.7E−01 |

| CG9989 | CG9989 | 1,821 | 20 | 24 | 1,230 | −6.48 | −6.25 | −0.57 | 1.7E−05 | 1.7E−05 | 4.0E−01 |

| CRMP | Dihydropyrimidine amidohydrolase | 321 | 154 | 155 | 415 | −1.05 | −1.05 | 0.37 | 1.9E−04 | 2.2E−04 | 4.9E−02 |

| csul | Capsuleen | 53 | 62 | 72 | 43 | 0.2 | 0.4 | −0.3 | 7.8E−02 | 1.6E−03 | 6.5E−03 |

| DopEcR | DopEcR | 6 | 16 | 18 | 5 | 1.29 | 1.45 | −0.31 | 5.3E−03 | 1.8E−03 | 1.7E−01 |

| dre4 | Suppressor of Ty element 16 | 136 | 115 | 141 | 143 | −0.24 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 1.6E−01 | 4.1E−01 | 2.5E−01 |

| dre4 | Suppressor of Ty element 16 | 57 | 90 | 98 | 71 | 0.67 | 0.80 | 0.33 | 2.5E−02 | 7.0E−03 | 1.8E−01 |

| Dro2 | Drosomycin-2 | 3,488 | 1 | 16 | 3,436 | −11.77 | −7.73 | −0.02 | 7.2E−05 | 7.3E−05 | 2.4E−01 |

| E(bx) | Nucleosome remodeling factor | 113 | 77 | 93 | 106 | −0.54 | −0.28 | −0.09 | 2.3E−02 | 8.4E−02 | 4.8E−01 |

| E23 | Early gene at 23 | 479 | 17 | 15 | 665 | −4.8 | −5.0 | 0.5 | 2.5E−04 | 2.4E−04 | 5.6E−02 |

| Edg78E | Ecdysone-dependent gene 78E | 5 | 6 | 10 | 6 | 0.37 | 2.7E−01 | ||||

| Edg91 | Ecdysone-dependent gene 91 | 25 | 94 | 91 | 31 | 1.93 | 1.89 | 0.32 | 3.2E−03 | 4.2E−03 | 2.8E−01 |

| Eig71Ea | Gene I | 2,555 | 2 | 3 | 1,955 | −10.04 | −9.66 | −0.39 | 6.6E−04 | 6.6E−04 | 4.8E−01 |

| Eig71Eb | Gene II | 2,392 | 3 | 4 | 1,712 | −9.65 | −9.20 | −0.48 | 3.0E−04 | 3.0E−04 | 4.6E−01 |

| Eig71Ec | Gene III | 1,986 | 4 | 4 | 441 | −8.97 | −8.98 | −2.17 | 7.5E−04 | 7.5E−04 | 7.9E−02 |

| Eig71Ed | Gene IV | 1,844 | 3 | 3 | 463 | −9.26 | −9.05 | −1.99 | 2.5E−03 | 2.5E−03 | 1.0E−01 |

| Eig71Ee | Gene VII | 1,271 | 588 | 13 | 3,385 | −1.11 | −6.64 | 1.41 | 5.2E−02 | 4.7E−05 | 1.7E−04 |

| Eig71Ef | Gene V | 988 | 1 | 1 | 545 | −10.10 | −9.81 | −0.86 | 1.2E−03 | 1.2E−03 | 2.9E−01 |

| Eig71Eg | Gene VI | 1,478 | 1 | 2 | 1,680 | −10.04 | −9.46 | 0.18 | 3.1E−04 | 3.1E−04 | 1.4E−01 |

| Eig71Eh | Eig71Eh | 7 | 3 | 3 | 2 | ||||||

| Eig71Ei | Eig71Ei | 5 | 5 | 6 | 3 | −0.69 | 1.0E−01 | ||||

| Eig71Ek | Eig71Ek | 7 | 3 | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Eip55E | Ecdysone-induced protein 40kD | 313 | 572 | 455 | 221 | 0.87 | 0.54 | −0.50 | 8.0E−04 | 6.2E−04 | 3.6E−02 |

| Eip63E | Ecdysone-induced protein 63E | 480 | 26 | 214 | 671 | −4.20 | −1.17 | 0.48 | 4.3E−06 | 2.3E−05 | 4.1E−02 |

| Eip63F-1 | Ecdysone-induced protein 63F 1 | 100 | 73 | 99 | 159 | −0.45 | −0.01 | 0.68 | 5.9E−02 | 4.7E−01 | 6.4E−04 |

| Eip63F-2 | Ecdysone-induced protein 63F 2 | 2 | 18 | 20 | 2 | 3.08 | 3.24 | 1.3E−03 | 2.8E−03 | ||

| Eip71CD | Methionine-S-sulfoxide reductase | 663 | 147 | 265 | 589 | −2.17 | −1.32 | −0.17 | 3.5E−03 | 6.4E−03 | 4.2E−01 |

| Eip74EF | Ecdysone-inducible protein 74EF | 70 | 3 | 8 | 906 | −4.7 | −3.2 | 3.7 | 1.6E−02 | 2.0E−02 | 5.5E−06 |

| Eip74EF | Ecdysone-inducible protein 74EF | 639 | 118 | 208 | 1,170 | −2.4 | −1.6 | 0.9 | 3.2E−04 | 3.4E−04 | 4.0E−03 |

| Eip75B | Ecdysone-induced protein 75B | 109 | 19 | 20 | 99 | −2.5 | −2.5 | −0.1 | 9.8E−04 | 1.1E−03 | 3.5E−01 |

| Eip75B | Ecdysone-induced protein 75B | 157 | 59 | 66 | 180 | −1.4 | −1.2 | 0.2 | 2.7E−02 | 3.4E−02 | 1.6E−01 |

| Eip78C | Nuclear hormone receptor | 847 | 13 | 5 | 1,360 | −6.01 | −7.53 | 0.68 | 9.3E−04 | 8.9E−04 | 3.3E−02 |

| Eip93F | Eip93F | 102 | 0 | 0 | 51 | −8.00 | −9.26 | −0.99 | 1.6E−03 | 1.6E−03 | 2.4E−01 |

| Eo | Ecdysone oxidase | 19 | 30 | 46 | 25 | 0.67 | 1.27 | 0.37 | 2.0E−03 | 1.1E−02 | 3.6E−01 |

| ftz-f1 | Ftz-interacting protein 1 | 9 | 37 | 23 | 6 | 2.09 | 1.41 | −0.43 | 1.3E−03 | 5.7E−04 | 1.4E−01 |

| GstE3 | GlutathioneS-transferase E3 | 286 | 1,087 | 614 | 173 | 1.93 | 1.10 | −0.73 | 3.1E−04 | 2.0E−04 | 1.3E−01 |

| gt | Giant | 3 | 6 | 3 | 5 | ||||||

| h | Hairy | 1,231 | 945 | 399 | 856 | −0.38 | −1.62 | −0.52 | 8.7E−02 | 1.4E−03 | 1.4E−01 |

| hfw | Singed wings | 184 | 136 | 164 | 201 | −0.43 | −0.16 | 0.13 | 5.2E−03 | 5.8E−02 | 8.8E−02 |

| Hnf4 | Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 | 160 | 180 | 197 | 164 | 0.17 | 0.30 | 0.04 | 1.4E−01 | 4.1E−02 | 5.0E−01 |

| Hr39 | Hormone receptor-like in 39 | 433 | 64 | 67 | 498 | −2.76 | −2.68 | 0.20 | 9.6E−05 | 9.0E−05 | 1.2E−01 |

| Hr39 | Hormone receptor-like in 39 | 214 | 37 | 38 | 238 | −2.53 | −2.48 | 0.15 | 1.8E−03 | 1.9E−03 | 1.7E−01 |

| Hr39 | Hormone receptor-like in 39 | 110 | 32 | 31 | 121 | −1.79 | −1.82 | 0.14 | 2.6E−03 | 2.8E−03 | 1.8E−01 |

| Hr39 | Hormone receptor-like in 39 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 9 | −1.47 | −2.23 | 0.13 | 3.5E−03 | 2.4E−03 | 1.4E−01 |

| Hr46 | Hormone receptor-like in 46 | 60 | 0 | 1 | 62 | −8.5 | −5.6 | 0.0 | 2.3E−05 | 2.7E−05 | 2.1E−01 |

| Hr78 | X receptor at 78E/F | 446 | 226 | 233 | 501 | −0.98 | −0.93 | 0.17 | 5.7E−05 | 6.2E−04 | 8.3E−02 |

| Hr96 | Hormone receptor-like in 96 | 84 | 127 | 139 | 99 | 0.59 | 0.72 | 0.23 | 1.6E−02 | 1.4E−04 | 2.6E−01 |

| ImpE1 | Y1-like | 374 | 9 | 10 | 363 | −5.36 | −5.17 | −0.04 | 1.4E−03 | 1.4E−03 | 2.7E−01 |

| ImpE1 | Y1-like | 19 | 1 | 1 | 16 | −4.91 | −4.41 | −0.30 | 3.8E−06 | 5.2E−06 | 4.3E−01 |

| ImpE1 | Y1-like | 26 | 1 | 2 | 19 | −4.13 | −4.10 | −0.44 | 3.1E−04 | 3.4E−04 | 4.6E−01 |

| ImpE2 | Ecdysone-inducible gene E2 | 2,717 | 13 | 10 | 2,777 | −7.76 | −8.11 | 0.03 | 9.5E−09 | 9.2E−09 | 2.0E−01 |

| ImpE3 | Ecdysone-inducible gene E3 | 570 | 14 | 18 | 464 | −5.33 | −5.01 | −0.30 | 1.6E−07 | 9.2E−08 | 4.3E−01 |

| ImpL1 | Ecdysone-inducible gene L1 | 181 | 21 | 24 | 69 | −3.11 | −2.90 | −1.39 | 4.2E−03 | 4.7E−03 | 1.2E−01 |

| ImpL2 | Neural and ectodermal development factor | 512 | 410 | 202 | 723 | −0.32 | −1.34 | 0.50 | 1.5E−01 | 8.1E−03 | 1.6E−02 |

| ImpL3 | Lactic DH | 155 | 2,311 | 1,434 | 98 | 3.89 | 3.21 | −0.67 | 4.3E−05 | 5.4E−06 | 2.0E−01 |

| Iswi | ISWI ATPase | 203 | 72 | 103 | 231 | −1.50 | −0.98 | 0.18 | 3.3E−05 | 1.2E−04 | 1.1E−01 |

| JIL-1 | Suppressor of variegation 3-1 | 36 | 17 | 19 | 62 | −1.07 | −0.89 | 0.79 | 2.2E−03 | 1.3E−03 | 3.9E−03 |

| Kr-h1 | Krueppel-homolog alpha-isoform | 288 | 55 | 46 | 301 | −2.39 | −2.64 | 0.06 | 1.4E−04 | 1.2E−04 | 2.1E−01 |

| lama | Lamina ancestor | 354 | 212 | 257 | 677 | −0.74 | −0.46 | 0.93 | 8.4E−03 | 1.0E−02 | 3.6E−03 |

| MESR3 | Misexpression suppressor of ras 3 | 657 | 135 | 132 | 688 | −2.29 | −2.31 | 0.07 | 6.9E−04 | 6.7E−04 | 1.9E−01 |

| mld | Molting defective | 142 | 49 | 46 | 155 | −1.52 | −1.63 | 0.13 | 3.1E−02 | 2.3E−02 | 2.0E−01 |

| Nurf-38 | Pyrophosphatase | 841 | 1,511 | 1,187 | 800 | 0.85 | 0.50 | −0.07 | 2.1E−04 | 4.5E−05 | 1.7E−01 |

| Pep | 74F gene | 717 | 396 | 409 | 561 | −0.86 | −0.81 | −0.36 | 3.4E−03 | 3.8E−03 | 2.8E−01 |

| ph-p | Polyhomeotic | 241 | 63 | 78 | 272 | −1.95 | −1.64 | 0.17 | 6.1E−03 | 8.0E−03 | 1.5E−01 |

| Ptp52F | Ptp52F | 93 | 86 | 101 | 113 | −0.12 | 0.11 | 0.28 | 3.0E−01 | 3.0E−01 | 1.0E−01 |

| Pu | GTP cyclohydrolase | 3,381 | 152 | 64 | 3,917 | −4.48 | −5.73 | 0.21 | 8.5E−06 | 7.6E−06 | 1.1E−01 |

| ras | IMP dehydrogenase | 1,235 | 243 | 289 | 1,163 | −2.35 | −2.10 | −0.09 | 2.9E−05 | 4.4E−05 | 3.0E−01 |

| rdgBbeta | rdgBbeta | 42 | 41 | 50 | 40 | −0.05 | 0.26 | −0.08 | 3.0E−01 | 3.2E−02 | 4.0E−01 |

| rhea | Tendrils | 689 | 355 | 664 | 926 | −0.96 | −0.05 | 0.43 | 3.5E−04 | 2.7E−01 | 1.5E−02 |

| rig | Rigor mortis | 88 | 63 | 61 | 88 | −0.49 | −0.54 | 0.00 | 4.2E−03 | 4.0E−03 | 2.5E−01 |

| rpr | Reaper | 286 | 22 | 18 | 144 | −3.69 | −3.96 | −0.99 | 9.0E−04 | 8.5E−04 | 2.0E−01 |

| sage | Salivary gland-expressed bHLH | 106 | 84 | 46 | 157 | −0.33 | −1.21 | 0.57 | 1.8E−01 | 2.7E−05 | 1.5E−04 |

| scu | Scully | 27 | 3 | 11 | 24 | −2.98 | −1.23 | −0.17 | 2.3E−04 | 4.0E−03 | 3.5E−01 |

| scu | Scully | 1,049 | 1,184 | 1,189 | 928 | 0.17 | 0.18 | −0.18 | 2.7E−02 | 2.3E−02 | 2.6E−02 |

| Sgs1 | Salivary gland secretion 1 | 9 | 86 | 1 | 12 | 3.29 | −3.65 | 0.44 | 7.7E−02 | 7.4E−03 | 2.4E−01 |

| Sgs3 | Group IV | 1,010 | 806 | 9 | 2,066 | −0.33 | −6.74 | 1.03 | 3.2E−01 | 9.6E−06 | 1.2E−01 |

| Sgs4 | Salivary gland secretion protein 4 | 819 | 298 | 5 | 1,571 | −1.46 | −7.29 | 0.94 | 2.5E−02 | 1.1E−04 | 1.4E−02 |

| Sgs5 | Salivary gland secretion 5 | 2,151 | 317 | 10 | 2,851 | −2.76 | −7.76 | 0.41 | 1.6E−03 | 4.4E−04 | 5.0E−02 |

| Sgs7 | Group III | 4,721 | 2,437 | 21 | 5,144 | −0.95 | −7.83 | 0.12 | 7.4E−02 | 7.2E−05 | 1.1E−01 |

| Sgs8 | gRoup II | 3,768 | 1,286 | 7 | 3,885 | −1.55 | −9.09 | 0.04 | 1.4E−02 | 1.3E−04 | 2.0E−01 |

| slmb | Pingiel | 326 | 85 | 89 | 451 | −1.93 | −1.87 | 0.47 | 1.2E−04 | 1.1E−04 | 2.3E−02 |

| Smr | SMRTER | 81 | 66 | 77 | 100 | −0.29 | −0.08 | 0.31 | 1.1E−01 | 3.0E−01 | 3.5E−02 |

| Sox14 | Sox box protein 14 | 723 | 47 | 77 | 882 | −3.95 | −3.23 | 0.29 | 9.8E−04 | 1.2E−03 | 1.0E−01 |

| swi2 | swi2 | 16 | 40 | 55 | 23 | 1.29 | 1.75 | 0.47 | 7.7E−03 | 4.9E−03 | 4.6E−01 |

| vri | Vrille | 266 | 68 | 52 | 245 | −1.97 | −2.36 | −0.11 | 1.7E−03 | 1.0E−03 | 3.4E−01 |

| W | Head involution defect | 75 | 11 | 17 | 84 | −2.83 | −2.12 | 0.16 | 1.2E−04 | 2.4E−04 | 1.4E−01 |

| zip | Myosin II | 1,496 | 315 | 271 | 1,699 | −2.25 | −2.47 | 0.18 | 2.0E−04 | 1.7E−04 | 1.2E−01 |

Boldface, repression; italics, activation.

Genes of the ecdysone biosynthesis pathway are downregulated in dATAC mutants.

We carried out QRT-PCR assays to validate the microarray data. The assays were focused on genes related to 20E signaling and biosynthesis in order to analyze the role of dATAC in metamorphosis. In dATAC mutants, the three isoforms of EcR and the coreceptor usp appeared somewhat downregulated (Fig. 4A). This moderate decrease in their corresponding mRNAs is not comparable to the almost complete absence of binding of the EcR protein to the polytene chromosomes (Fig. 1B). Thus, the observed reduction of EcR binding is most likely a combined effect of (i) the nonavailability of the EcR ligand, 20E; (ii) an average of approximately 50% reduction of EcR subunit levels; and (iii) a reduction of the level of EcR coreceptor, USP. In addition, the expression of several ecdysone-induced genes (Eig) was downregulated by severalfold (Fig. 4B and Table 2). These effects further indicate that most of the transcriptome changes could originate from the observed reduction of 20E levels in the mutants. Thus, we tested the genes involved in 20E biosynthesis.

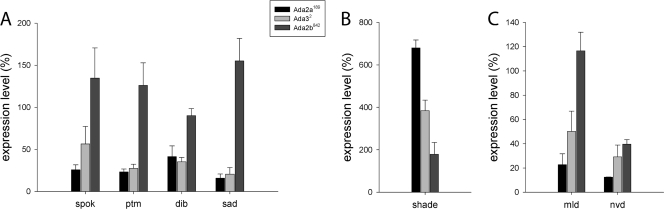

The microarray data had indicated a reduced level of mRNAs corresponding to the Halloween genes spookier, phantom, disembodied, and shadow, while some increase in the shade mRNA level was evident. In contrast to the Halloween genes, many other members of the large cytochrome gene family (Cyp450) showed an increase or no change in their expression (Fig. 3C). QRT-PCR analysis confirmed these data, showing a strong reduction in the levels of those Halloween genes, which are expressed in the prothoracic gland, in both dAda2a and dAda3 mutants (Fig. 5A). In contrast, the expression of shade, the product of which transforms E into 20E at the peripheral tissues, but not in the prothoracic gland, was increased in both dATAC mutants. Significantly, neither of the prothoracic gland-specific Halloween genes showed reduced expression in the dAda2b mutant, nor was the expression of shade significantly changed in the dAda2b mutant (Fig. 5B). This differential effect of dATAC on all known E biosynthesis genes versus the E-to-20E transforming gene may indicate a role of dATAC in the fine regulation of the equilibrium between the inactive and active forms of the hormone. In this context, we analyzed by QRT-PCR two additional genes whose mutants showed reduced levels or activity of 20E, although their precise enzymatic substrates are not yet known: molting defective (mld) and neverland (nvd) (Fig. 5C). Both genes are severely downregulated in the two dATAC mutants, consistent with the other Halloween genes. Only in the case of nvd, however, did the dSAGA mutant dAda2b also show downregulation of its expression. The similar effects of dATAC and dSAGA on the regulation of this gene may reflect its peculiar role in the biosynthesis of E. Indeed, the gene nvd does not participate in E production during midembryogenesis, while all other Halloween genes do (34). Thus, all the genes known to play a role in E biosynthesis require dATAC for their proper expression. On the other hand, the gene transforming E to 20E seems to be repressed in the presence of dATAC subunits.

FIG. 5.

Expression of Halloween genes in dATAC mutants. The mRNA levels were determined by QRT-PCR in three independent experiments and are shown as ratios between mutant and control (w1118). (A) The four Halloween genes show consistent downregulation in dAda32 and dAda2a189, in contrast to dAda2b842, mutants. (B) The gene responsible for the E-to-20E conversion, shade, exhibits effects opposite to those of the genes in panel A. (C) The expression levels of two relatively uncharacterized genes of the ecdysone-synthesizing pathway, molting defective and neverland, in dATAC mutants are similar to those of the prothoracic gland-specific Halloween genes. The error bars indicate the SEM.

To further support the hypothesis that the defect of ecdysone biosynthesis in ATAC mutants is at least partially responsible for the reduced expression of ecdysone-induced genes, we investigated whether induction of ecdysone response genes could be rescued by 20E treatment. We dissected salivary glands from dAda2a189, dAda32, and heterozygous control larvae; separated the two glands; and incubated them with 20E or vehicle control. We compared the mRNA level of the Eig74 (Fig. 6A) and Eig75 (Fig. 6B) genes in the matched 20E/mock-treated sample pairs and found that both genes could be induced in the dAda2a mutant and that Eig75 could be induced in the dAda3 mutant, although the rescue was not complete.

FIG. 6.

Effects of 20E treatment on gene expression and pupariation in dATAC mutants. Dissected salivary glands of dAda2a189, dAda32, or heterozygous control L3 larvae were separated, and the two parts were incubated with 20E or vehicle control, respectively. The transcript levels of the ecdysone response genes Eig74 (A) and Eig75 (B) were measured by QRT-PCR, and the average and standard error of the induction in 20E- versus mock-treated matched samples were plotted. At least four matched samples were measured per genotype. (C) The chart shows the ratio of dAda2a189, dAda32, or heterozygous control larvae in which pupariation was initiated after feeding on 20E or vehicle control containing food in mid-L3 stage. The averages and standard errors of four feeding experiments with a sum of 30 larvae in each category are shown.

dATAC mutants do not alter prothoracic gland structure or cholesterol transport.

The transcriptional features observed in the dATAC mutants could result from structural defects in the ring gland, the organ from which E is synthesized and secreted. To test this possibility, we compared the morphologies of ring glands of dAda2a and dAda3 mutants and the w1118 control. Within the ring gland, the hormone is produced by a subset of cells constituting the prothoracic gland, whose large polytene cells can be identified easily. The general morphology of the gland and the numbers of polytene cells were comparable in all four genotypes investigated (data not shown). Further evidence of the normal condition of the ring gland in the mutants is the fact that the transcription levels of the calmodulin gene, which is expressed exclusively in this tissue at this stage of development, was not affected in the microarray data set.

Ecdysone is synthesized in the prothoracic gland from dietary cholesterol in response to the prothoracicotropic hormone (PTTH) signal produced by specific brain cells. Thus, the failure to activate the E-synthesizing genes could originate from the lack of either its metabolic precursor or the signal itself. Indeed, a failure in the transport of cholesterol has been reported in start, NPC1, and NPC2 mutants, and the mRNA levels of all three genes are decreased in dAda2a and dAda3 mutants (Table 2). We addressed these possibilities in several experimental assays. First, we fed cholesterol to dAda2a and dAda3 mutants, aiming for a potential rescue. No rescue occurred. On the contrary, addition of 20E to the medium of dAda2a or dAda3 larvae extended their development by more than doubling the number of larvae initiating pupariation (Fig. 6C). Second, we stained the mutant tissue samples with Filipin, searching for the possible accumulation of cholesterol granules. No accumulation was detected (data not shown). Finally, the mRNA levels of PTTH were analyzed in the microarray data and found to be normal in the mutants (Table 2). Thus, we conclude that the mutant transcriptional phenotypes of the E-synthesizing genes do not result from defective cholesterol transport or PTTH signaling.

Directed expression of dADA3 in the prothoracic gland rescues metamorphosis.

In order to validate the role of dADA3 in the regulation of E-synthesizing genes, we restored dAda3 expression specifically in the prothoracic gland on a dAda32 mutant background. To that end, we used the Gal4/UAS system with phantom-Gal4 as the driver (23). Similarly to the native phantom gene, this driver is selectively expressed in the prothoracic gland. The transgenic expression of dADA3 resulted in a partial rescue of the null mutant (Fig. 7). In this genotype, the mutant progressed through metamorphosis, reaching the stage of pharate adults. Fully viable adults are not to be expected, since the dADA3 function is not restored in other tissues. Thus, this result provides in vivo evidence that dADA3 is required in the cells in which E is biosynthesized.

FIG. 7.

dADA3 expression rescues the mutant when driven in the ring gland. (A) Expression of the ADA3 transgene in the phantom domain at the larval stage visualized with GFP. Note the selective expression in the ring gland. (B) Lethality phase of dAda3 mutants. The dAda32 allele fails to pupariate or forms abnormal pupae. (C) Normal pupae at the P4 and P5 stages shown for comparison. (D) Rescue of dAda32 mutants by driving transgene expression in the phantom domain. (E) Phenotype quantifications. The fractions of animals that perished in the indicated developmental stages are shown. The error bars indicate the SEM.

DISCUSSION

HAT complexes as regulators of gene ensembles across species.

Drosophila and Arabidopsis cells, and mammalian cells as well, contain SAGA-type complexes, which harbor ADA2b, and at least one functionally distinct ADA2a-containing complex, ATAC. This diversity of GCN5-containing complexes in multicellular eukaryotes raises questions about their functional diversity. Mutations of the Drosophila dAda2 and dAda3 genes result in striking differences in phenotypes and in alterations in histone acetylation. Recently, we have shown that in the dSAGA-specific dAda2b mutants the expression of a relatively small number of genes is affected (37). Here, we show the expression profiles of mutants in the other GCN5-containing complex, dATAC. A comparison of Gcn5, Nurf301, and the ATAC-specific Ada2a mutant transcriptomes was published previously by Carré et al. (4). In sharp contrast to dSAGA, mutations in dATAC-specific subunits have a profound effect on the expression of a large number of genes. It is intriguing that apparently similar extents of reductions in H3 and H4 acetylation levels in dSAGA and dATAC mutants, respectively, give rise to such different effects on transcription (7, 12, 13, 25). The coordinated decreases and increases of mRNA levels representing sets of functionally related genes might indicate that histone modifications by dATAC play a direct role in the transcription of these sets of genes or a master switch placed higher up in the regulatory hierarchy. While some of the genes that play a role in cholesterol transport and those coding for subunits of ecdysone receptors are negatively affected by dATAC mutations, the extent of the expression changes in these genes can hardly explain the dramatic decreases observed in the mRNA levels of many E-regulated genes. On the contrary, (i) the decreased ecdysteroid levels observed; (ii) the partial rescue of phenotypes resulting from 20E, but not cholesterol, feeding of mutants; and, most relevant, (iii) the QRT-PCR-validated downregulation of Halloween Cyp450 mRNA levels in contrast to the unchanged or slightly elevated levels of other Cyp450 mRNAs strongly indicate a failure of E synthesis in dATAC mutants. The unchanged PTTH level and prothoracic gland morphology do not indicate that either the signal for E synthesis or a lack of development of the gland is the cause of E synthesis failure. Rather, a coordinated downregulation of those Halloween genes participating in E synthesis in the prothoracic gland is characteristic of dATAC mutants. In sharp contrast with the low mRNA level of spookier/Cyp307A2, phantom/Cyp306A1, disembodied/Cyp302A1, and shadow/Cyp315A1, the gene transforming E into its active form in the peripheries (shade/Cyp314A1) is upregulated in dATAC mutants. This might reflect either a compensatory effect or a lack of feedback inhibition of shd expression. In accord with this, ectopic expression of dADA3 under the control of a prothoracic gland-specific promoter partially rescued dAda3 mutants. Thus, our data provide an example of coordinated regulation of a set of functionally linked genes by a metazoan GCN5-containing HAT complex. These data also demonstrate that, in this function, the two GCN5-containing HAT complexes dATAC and dSAGA play strikingly different roles. GCN5 association with dADA2a and other components of the dATAC complex makes it highly specific in regulating the expression of Halloween genes in the prothoracic gland. At present, our data do not resolve whether dATAC affects the expression of Halloween genes directly by modifying the chromatin structure in the regulatory region(s) of these transcription units or by modulating the level or activity of a master transcriptional regulator acting on these genes. Results demonstrating ATAC subunits localized at actively transcribed regions and in interaction with transcription activators on one hand and transcription induction in the lack of a functional ATAC complex on the other hand suggest that at different genes ATAC might function by different, or more than one, mechanism. This might be true for the Halloween genes, as well. These data are highly significant, since, combined with our earlier data on the effect of dSAGA on the transcription profile (37), they represent one of the first demonstrations of the very different effects of two HAT complexes sharing the same catalytic subunit in gene expression regulation.

dATAC on metamorphosis.

It is interesting that dATAC mutants arrest development at the larval-prepupal transition and that they do not present any evident defect during larval development. Given that in Drosophila pulses of 20E signal arise in all developmental transitions, including larval molting and puparium formation (30), our results suggest that the mechanisms coordinating the production of ecdysteroids in larval-larval and larval-pupal transitions are different. Our data highlight the fact that dADA2a and dADA3 are necessary for stage-specific control of ecdysteroid production through the induction of the Halloween Cyp450 genes at the onset of puparium formation. Importantly, both factors are also important for the correct activation of a number of genes that belong to the 20E-triggered genetic hierarchy during metamorphosis. dATAC mutants strongly affect the expression, for example, of one of these factors, Broad, which specifies progression through pupal development and hence is necessary for the activation of pupal-specific genes, as well as for the inhibition of larval and adult genes (8). Taken together, the results presented here indicate that dADA2a and dADA3 are central proteins in metamorphosing insects. The characterization of the developmentally controlled mechanisms that coordinate the synthesis of ecdysteroids and the response to such hormones, specifically during metamorphosis, could be relevant to understanding how complete metamorphosis has evolved. In this context, it would be interesting to analyze the role of Ada2a and Ada3 orthologue genes in hemimetabolous insects that do not present the intermediate pupal stage.

Finally, in vertebrates, SAGA-type complexes have been involved in the activation of several different nuclear receptor-regulated genes (36). By analogy to the experiments presented above, showing a key role of dATAC in E synthesis, further experiments in mammalian cells would help to understand the role of ATAC in steroid hormone synthesis.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Christen Mirth (Janelia Farm) for fly strains, to Christelle Thibault for carrying out the Affymetrix expression analyses, and to Gabriella Pankotai-Bodo and Zita Nagy for critically reading the manuscript.

Binational grants between Spain and Hungary (HH2006-0025) and Hungary and France (FR-33/08) provided support to B.G., L.T., and I.B. L.B. was supported by the Hungarian State Science Fund (OTKA PD72491). Research was supported by funds from the FRM and the European Community (HPRN-CT 00504228, STREP LSHG-CT-2004-502950, and EUTRACC LSHG-CT-2007-037445) and Réseau National des Génopoles (no. 260) and by INCA (2008-UBICAN) grants to L.T.; Spanish Ministry of Research BFU2006-10180 and TAF-CHROMATIN European Network MRTN-CT-2004-504288 grants to A.F. and I.B.; and the Hungarian State Science Fund (OTKA K77443) to I.B.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 June 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baehrecke, E. H. 1996. Ecdysone signaling cascade and regulation of Drosophila metamorphosis. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 33:231-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balasubramanian, R., M. G. Pray-Grant, W. Selleck, P. A. Grant, and S. Tan. 2002. Role of the Ada2 and Ada3 transcriptional coactivators in histone acetylation. J. Biol. Chem. 277:7989-7995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berger, S. L. 2007. The complex language of chromatin regulation during transcription. Nature 447:407-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carré, C., A. Ciurciu, O. Komonyi, C. Jacquier, D. Fagegaltier, J. Pidoux, H. Tricoire, L. Tora, I. M. Boros, and C. Antoniewski. 2008. The Drosophila NURF remodelling and the ATAC histone acetylase complexes functionally interact and are required for global chromosome organization. EMBO Rep. 9:187-192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carré, C., D. Szymczak, J. Pidoux, and C. Antoniewski. 2005. The histone H3 acetylase dGcn5 is a key player in Drosophila melanogaster metamorphosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:8228-8238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carrozza, M. J., R. T. Utley, J. L. Workman, and J. Cote. 2003. The diverse functions of histone acetyltransferase complexes. Trends Genet. 19:321-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ciurciu, A., O. Komonyi, T. Pankotai, and I. M. Boros. 2006. The Drosophila histone acetyltransferase Gcn5 and transcriptional adaptor Ada2a are involved in nucleosomal histone H4 acetylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:9413-9423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erezyilmaz, D. F., L. M. Riddiford, and J. W. Truman. 2006. The pupal specifier broad directs progressive morphogenesis in a direct-developing insect. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:6925-6930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Germaniuk-Kurowska, A., A. Nag, X. Zhao, M. Dimri, H. Band, and V. Band. 2007. Ada3 requirement for HAT recruitment to estrogen receptors and estrogen-dependent breast cancer cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 67:11789-11797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilbert, L. I. 2004. Halloween genes encode P450 enzymes that mediate steroid hormone biosynthesis in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 215:1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grant, P. A., D. Schieltz, M. G. Pray-Grant, D. J. Steger, J. C. Reese, J. R. Yates III, and J. L. Workman. 1998. A subset of TAF(II)s are integral components of the SAGA complex required for nucleosome acetylation and transcriptional stimulation. Cell 94:45-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grau, B., C. Popescu, L. Torroja, D. Ortuno-Sahagun, I. Boros, and A. Ferrus. 2008. Transcriptional adaptor ADA3 of Drosophila melanogaster is required for histone modification, position effect variegation, and transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28:376-385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guelman, S., T. Suganuma, L. Florens, S. K. Swanson, C. L. Kiesecker, T. Kusch, S. Anderson, J. R. Yates III, M. P. Washburn, S. M. Abmayr, and J. L. Workman. 2006. Host cell factor and an uncharacterized SANT domain protein are stable components of ATAC, a novel dAda2A/dGcn5-containing histone acetyltransferase complex in Drosophila. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:871-882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haase, J., M. M. van der Linden, C. Di Mario, W. J. van der Giessen, D. P. Foley, and P. W. Serruys. 1993. Can the same edge-detection algorithm be applied to on-line and off-line analysis systems? Validation of a new cinefilm-based geometric coronary measurement software. Am. Heart J. 126:312-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall, B. L., and C. S. Thummel. 1998. The RXR homolog ultraspiracle is an essential component of the Drosophila ecdysone receptor. Development 125:4709-4717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang, X., K. Suyama, J. Buchanan, A. J. Zhu, and M. P. Scott. 2005. A Drosophila model of the Niemann-Pick type C lysosome storage disease: dnpc1a is required for molting and sterol homeostasis. Development 132:5115-5124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang, X., J. T. Warren, J. Buchanan, L. I. Gilbert, and M. P. Scott. 2007. Drosophila Niemann-Pick type C-2 genes control sterol homeostasis and steroid biosynthesis: a model of human neurodegenerative disease. Development 134:3733-3742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huet, F., C. Ruiz, and G. Richards. 1993. Puffs and PCR: the in vivo dynamics of early gene expression during ecdysone responses in Drosophila. Development 118:613-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ito, T. 2007. Role of histone modification in chromatin dynamics. J. Biochem. 141:609-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar, A., Y. Zhao, G. Meng, M. Zeng, S. Srinivasan, L. M. Delmolino, Q. Gao, G. Dimri, G. F. Weber, D. E. Wazer, H. Band, and V. Band. 2002. Human papillomavirus oncoprotein E6 inactivates the transcriptional coactivator human ADA3. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:5801-5812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McBrayer, Z., H. Ono, M. Shimell, J. P. Parvy, R. B. Beckstead, J. T. Warren, C. S. Thummel, C. Dauphin-Villemant, L. I. Gilbert, and M. B. O'Connor. 2007. Prothoracicotropic hormone regulates developmental timing and body size in Drosophila. Dev. Cell 13:857-871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meng, G., Y. Zhao, A. Nag, M. Zeng, G. Dimri, Q. Gao, D. E. Wazer, R. Kumar, H. Band, and V. Band. 2004. Human ADA3 binds to estrogen receptor (ER) and functions as a coactivator for ER-mediated transactivation. J. Biol. Chem. 279:54230-54240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mirth, C., J. W. Truman, and L. M. Riddiford. 2005. The role of the prothoracic gland in determining critical weight for metamorphosis in Drosophila melanogaster. Curr. Biol. 15:1796-1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nag, A., A. Germaniuk-Kurowska, M. Dimri, M. A. Sassack, C. B. Gurumurthy, Q. Gao, G. Dimri, H. Band, and V. Band. 2007. An essential role of human Ada3 in p53 acetylation. J. Biol. Chem. 282:8812-8820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pankotai, T., O. Komonyi, L. Bodai, Z. Ujfaludi, S. Muratoglu, A. Ciurciu, L. Tora, J. Szabad, and I. Boros. 2005. The homologous Drosophila transcriptional adaptors ADA2a and ADA2b are both required for normal development but have different functions. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:8215-8227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porcheron, P., J. Foucrier, C. Gros, P. Pradelles, P. Cassier, and F. Dray. 1976. Radioimmunoassay of arthropod moulting hormone:beta-ecdysone antibodies production and 125 I-iodinated tracer preparation. FEBS Lett. 61:159-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Romana, S. P., M. Mauchauffe, M. Le Coniat, I. Chumakov, D. Le Paslier, R. Berger, and O. A. Bernard. 1995. The t(12;21) of acute lymphoblastic leukemia results in a tel-AML1 gene fusion. Blood 85:3662-3670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strahl, B. D., and C. D. Allis. 2000. The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature 403:41-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Talbot, W. S., E. A. Swyryd, and D. S. Hogness. 1993. Drosophila tissues with different metamorphic responses to ecdysone express different ecdysone receptor isoforms. Cell 73:1323-1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thummel, C. S. 1995. From embryogenesis to metamorphosis: the regulation and function of Drosophila nuclear receptor superfamily members. Cell 83:871-877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warren, J. T., A. Petryk, G. Marques, M. Jarcho, J. P. Parvy, C. Dauphin-Villemant, M. B. O'Connor, and L. I. Gilbert. 2002. Molecular and biochemical characterization of two P450 enzymes in the ecdysteroidogenic pathway of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:11043-11048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winer, J., C. K. Jung, I. Shackel, and P. M. Williams. 1999. Development and validation of real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction for monitoring gene expression in cardiac myocytes in vitro. Anal. Biochem. 270:41-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yao, T. P., B. M. Forman, Z. Jiang, L. Cherbas, J. D. Chen, M. McKeown, P. Cherbas, and R. M. Evans. 1993. Functional ecdysone receptor is the product of EcR and Ultraspiracle genes. Nature 366:476-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshiyama, T., T. Namiki, K. Mita, H. Kataoka, and R. Niwa. 2006. Neverland is an evolutionally conserved Rieske-domain protein that is essential for ecdysone synthesis and insect growth. Development 133:2565-2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zeng, M., A. Kumar, G. Meng, Q. Gao, G. Dimri, D. Wazer, H. Band, and V. Band. 2002. Human papilloma virus 16 E6 oncoprotein inhibits retinoic X receptor-mediated transactivation by targeting human ADA3 coactivator. J. Biol. Chem. 277:45611-45618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao, Y., G. Lang, S. Ito, J. Bonnet, E. Metzger, S. Sawatsubashi, E. Suzuki, X. Le Guezennec, H. G. Stunnenberg, A. Krasnov, S. G. Georgieva, R. Schule, K. Takeyama, S. Kato, L. Tora, and D. Devys. 2008. A TFTC/STAGA module mediates histone H2A and H2B deubiquitination, coactivates nuclear receptors, and counteracts heterochromatin silencing. Mol. Cell 29:92-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zsindely, N., T. Pankotai, Z. Ujfaludi, D. Lakatos, O. Komonyi, L. Bodai, L. Tora, and I. M. Boros. 2009. The loss of histone H3 lysine 9 acetylation due to dSAGA-specific dAda2b mutation influences the expression of only a small subset of genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:6665-6680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]