Abstract

HIV-1 is known to package several small cellular RNAs in addition to its genome. Previous work consistently demonstrated that the host structural RNA 7SL is abundant in HIV-1 virions but has yielded conflicting results regarding whether 7SL is present in minimal, assembly-competent virus-like particles (VLPs). Here, we demonstrate that minimal HIV-1 VLPs retain 7SL RNA primarily as an endoribonucleolytic fragment, referred to as 7SL remnant (7SLrem). Nuclease mapping showed that 7SLrem is a 111-nucleotide internal portion of 7SL, with 5′ and 3′ ends corresponding to unpaired loops in the 7SL two-dimensional structure. Analysis of VLPs comprised of different subsets of Gag domains revealed that all NC-positive VLPs contained intact 7SL while the presence of 7SLrem correlated with the absence of the NC domain. Because 7SLrem, which maps to the 7SL S domain, was not detectable in infected cells, we propose a model whereby the species recruited to assembling VLPs is intact 7SL RNA, with 7SLrem produced by an endoribonuclease in the absence of NC. Since recruitment of 7SL RNA was a conserved feature of all tested minimal VLPs, our model further suggests that 7SL's recruitment is mediated, either directly or indirectly, through interactions with conserved features of all tested VLPs, such as the C-terminal domain of CA.

Retroviruses such as HIV-1 exist as a collection of proteins and RNA; as such, they can be considered to be ribonucleoprotein complexes, assembled and released from the host cell under the direction of the viral genome. The viral structural protein Gag forms the core of the particle (reviewed in reference 13). Gag is expressed as a polyprotein consisting of six domains: matrix (MA), capsid (CA), spacer protein 1 (SP1), nucleocapsid (NC), spacer protein 2 (SP2), and p6. The domains of Gag are known to function in assembly as follows: MA binds to the plasma membrane via a cotranslationally added myristate moiety; CA and SP1 promote Gag multimerization by protein-protein interactions; NC functions both in protein-protein interactions required for Gag multimerization and in genomic RNA recruitment; and p6 mediates virion release. Gag is the only viral protein required to form virus-like particles (VLPs) both in vivo and in vitro, but RNA is required for assembly under physiological conditions (6, 37). Furthermore, a minimal Gag—containing only the first 12 amino acids of MA, the C terminus of CA plus SP1, and a leucine zipper motif replacing NC—efficiently produces VLPs in 293T cells (1).

The primary RNA present in viral particles is the genomic RNA (gRNA). Retroviruses package gRNA as a dimer, and HIV-1 gRNA packaging is mediated via interactions between a region of gRNA known as the packaging signal (Ψ) and the NC domain of Gag (2, 10, 21). Although gRNA and NC are both dispensable for virus assembly, in vitro studies show some sort of RNA is required for assembly (26, 37). This implies that cellular RNAs are capable of playing some role in assembly, and, indeed, up to 30% of the mass of RNA in retrovirus particles is of cellular origin (22). These include specific cellular RNAs which are present in concentrations that differ from those in the cell, implying that they are packaged specifically rather than randomly (4, 16, 22, 29, 30). The majority of cellular RNAs known to be packaged by retroviruses are small, noncoding polymerase III (Pol III) products that serve structural or enzymatic functions in the cell (29). The only cellular RNA present in retroviral particles whose viral function is known is the tRNA used to prime reverse transcription (20, 24).

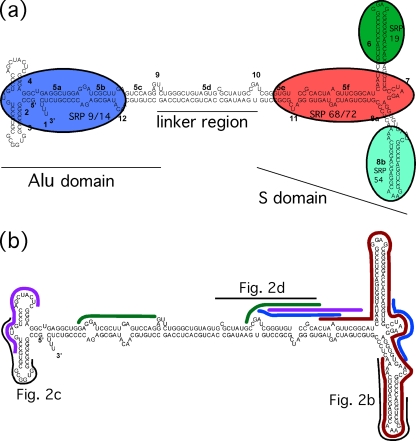

One highly abundant cellular RNA, which is packaged by a broad range of retroviruses, is 7SL RNA, a component of the signal recognition particle (SRP). In the cell, the SRP serves to target nascent secretory or membrane polypeptides to the endoplasmic reticulum (reviewed in references 9 and 23). 7SL is composed of three domains: the Alu domain, the S domain, and the linker region which separates the two (Fig. 1 a). 7SL is the structural scaffold upon which the six proteins of the SRP bind. There is some evidence that a highly conserved region of 7SL RNA catalyzes the binding of SRP to its receptor, SR (for SRP receptor), and that this RNA stimulates the GTPase activities of the SRP-SR complex without the presence of a GTPase-activating protein (32, 33). Previous work has determined that 7SL is present in HIV-1 particles at 6 to 8 copies per genomic RNA, or approximately 14 copies per virion, and that encapsidated 7SL lacks its p54 protein component and thus is not packaged as part of the SRP (30).

FIG. 1.

7SL. (a) Schematic of human 7SL RNA, showing domains, nomenclature, and binding locations of signal recognition particle (SRP) proteins (23). (b) Locations of probes and RT-PCR primers used to determine the presence of 7SL in minimal virus-like particles. Thick lines represent RPA and RT-PCR studies performed previously: red, RPA from Onafuwa-Nuga et al. (30); blue, RT-PCR from Wang et al. (38, 39) and Bach et al. (3); purple, RT-PCR from Bach et al. (3); green, RT-PCR from Crist et al. (8). Thin lines represent probes used in this study, labeled to indicate which figure depicts the relevant experiment.

A recent publication that concludes that minimal virus-like particles lack detectable RNA seems to rule out the possibility that 7SL may be important to the virus (8). However, in the current study we demonstrate that a fragment of 7SL corresponding to the S domain is retained in minimal VLPs at the same copy number as full-length 7SL in intact Gag forms of HIV-1. These and other data support a model in which 7SL RNA is recruited into assembling virions via portions of Gag that are retained in minimal VLPs, the nucleocapsid region of Gag subsequently protects the majority of 7SL from processing, and a host endonuclease interacts with HIV-1 at some point during assembly.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and plasmids.

293T cells were cultured and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gemini). Cells were grown at 37°C under 5% CO2. Virions containing processed Gag and Gag-Pol were produced by the plasmid pCMVΔR8.2, a Ψ-negative, env-negative proviral vector driven by the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter (27). VLPs containing intact Gag were produced by the plasmid pVR1012x/s Gag/h, which produces a protein identical to the Gag sequence of HXB2 (GenBank accession number K03455) but whose nucleotide sequence has been optimized for production in human cells (17). Minimal ΔNC VLPs, constructed by H. Gottlinger and colleagues, were described previously (1, 30). The pNL4-3/Fyn(10) constructs, which produce Gag containing 10 amino acids from fyn kinase, were a generous gift from A. Ono (University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI) (5, 31).

Transfection.

Transfections of 293T cells were carried out on 100-mm plates. Virus and minimal ΔNC VLPs were produced by CaPO4 transfection, as described previously (30). Fyn(10) virions were produced by polyethylenimine (PEI) transfection. For transfection by PEI, plasmid DNA was mixed with 4 μg of polyethylenimine (Polysciences) per μg of DNA in 1 ml of 150 mM NaCl by vortexing at medium speed for 10 s. After room temperature incubation for 15 min, the mixture was added dropwise to medium on cells. The transfection mixture was not removed prior to virus harvesting.

Viral processing and RNA isolation.

Tissue culture medium was harvested at 24 h, and at 48 h posttransfection, the culture was pooled and filtered through 0.2-μm-pore-size filters. Virus was concentrated by centrifugation of virus-containing medium through a 2-ml 20% sucrose cushion in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 2 h at 4°C and 25,000 rpm using a Sorvall Surespin 630 rotor in a Sorvall Discovery 90 ultracentrifuge. Viral pellets were suspended in 0.5 ml of Trizol reagent (Invitrogen), and RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cellular RNA was obtained by harvesting cells 48 h after transfection by scraping cells into 2 ml of Trizol reagent per 100-mm plate, and RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Northern blotting.

Cellular and viral RNAs were separated by 8% polyacrylamide-8 M urea gel electrophoresis in 1× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer at 350 V for 2 h. The amount of viral RNA loaded in each lane was normalized to the volume of virus-containing medium harvested, with each lane containing half of the RNA isolated from the virus produced by one transfected 100-mm plate over a 48-h period. The amount of cellular RNA loaded per lane was 0.6% of the total RNA isolated from a confluent 100-mm plate. RNA was transferred by electroblotting onto Zeta-probe GT nylon membranes (Bio-Rad) in 0.5× TBE buffer. After transfer, membranes were air dried and UV cross-linked (Stratalinker; Stratagene). Prehybridization was performed at 52°C for 1 h in 6× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)-5× Denhardt's solution-0.5% (SDS)-0.025 M sodium phosphate (pH 6.5)-625 μg/ml of denatured salmon sperm DNA. Oligonucleotide probes were denatured by boiling at 100°C for 5 min and then radiolabeled using [γ-32P]ATP (Perkin-Elmer) and T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs). The Alu domain probe used in the experiment shown in Fig. 2c was 5′-GACTACAGGCACGCGCCACCG-3′. The S domain probe used in the experiments shown in Fig. 2b and 4 was 5′-TTTTGACCTGCTCCGTTTCCGACCT-3′. The linker region probe used for the experiment shown in Fig. 2d was 5′-TGCGGACACCCGATCGGCATAGCGC-3′. Radiolabeled probes were added to the hybridization buffer, and hybridization was carried out at 52°C for 16 h. After hybridization, the blots were washed in 2× SSC-0.1% SDS at 50°C for 15 min, then 0.5× SSC-0.1% SDS at 50°C for 15 min, and finally 0.33× SSC-0.1% SDS at 50°C for 15 min. Damp blots were wrapped in Saran Wrap and exposed to phosphorimager screens. If reprobing with a new oligonucleotide probe was required, blots were stripped by washing three times in 0.1% SDS in double-distilled H2O (ddH2O) at 80°C and then prehybridized and probed as described above. Images were acquired by scanning with a Typhoon Trio Variable Mode Imager (Amersham Biosciences), and quantification was performed using the one-dimensional (1D) gel imaging feature of ImageQuant TL, version 7.0 (GE Healthcare).

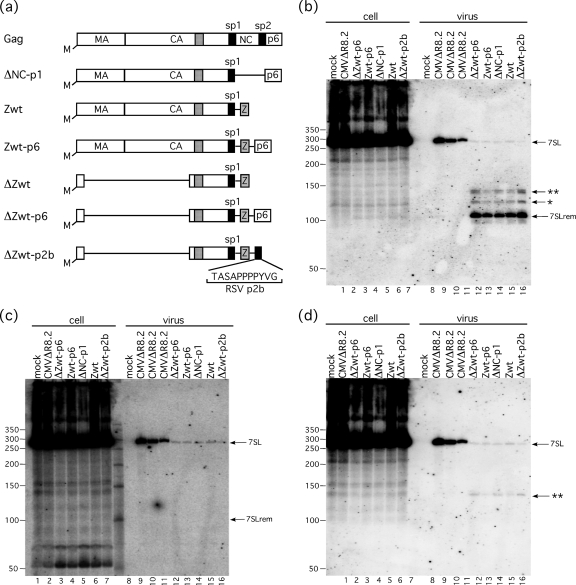

FIG. 2.

Retention of a fragment of 7SL in minimal virus-like particles. (a) Schematic representation of constructs here used to produce minimal virus-like particles. The dotted box within CA represents the major homology region. Lines represent deleted sequences. The myristate moiety (M) is indicated. (Adapted from reference 1 with permission.) (b, c, and d) Northern blots of RNA isolated from transfected cells and minimal VLPs. RNAs loaded in each lane are indicated at the top. Lanes 9 to 11 are 3-fold serial dilutions of virus from cells transfected with pCMVΔR8.2; RNAs in lanes 12 to 16 were from the same volume of transfected cell medium as lane 9. Probes used were specific to the S domain (b), Alu domain (c), and linker region (d), as indicated in Fig. 1. Full-length 7SL, 7SLrem, and the two remaining fragments (* and **) are indicated with arrows. RSV, Rous sarcoma virus.

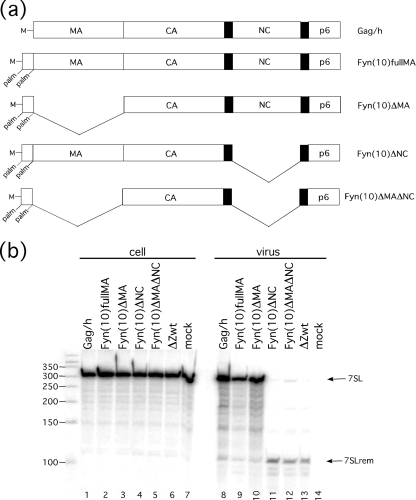

FIG. 4.

Packaging of 7SL in ΔMA virions. (a) Schematic of Gag derivatives with the addition of the N-terminal 10 amino acids of Fyn kinase. Myristate (M) and palmitate (palm) moieties are shown. (b) Northern blot of RNA from Fyn(10) constructions, as well as ΔZwt, a minimal VLP seen in Fig. 3, using a probe specific to the S domain.

S1 nuclease mapping.

A probe specific to the 3′ half of 7SL was created by digesting the plasmid p7SL30.1 (41) with Bsu36I, which cleaves within the 7SL coding region between residues C170 and T171. The linearized plasmid was radiolabeled on both ends using [α-32P]dTTP (Perkin-Elmer) and Klenow DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) and then further digested with EcoRI at a site downstream of 7SL. The resulting 160-bp fragment was separated into single strands by boiling for 5 min and purified by strand separation electrophoresis on a nondenaturing 5% polyacrylamide gel. S1 nuclease digestion to map an endoribonucleolytic fragment of 7SL, 7SLrem (for 7SL remnant), using this probe and cell and VLP-derived RNA samples, was carried out according to Green and Struhl (14). After S1 nuclease digestion, the samples were separated on a denaturing 8% polyacrylamide sequencing gel and exposed to a phosphorimager screen.

Primer extension to map the 5′ end of 7SLrem.

An oligonucleotide probe specific to the S domain of 7SL, 5′-TTTTGACCTGCTCCGTTTCCGACCT-3′, was radiolabeled using [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase and mixed with viral RNA. The probe-RNA mixture was ethanol precipitated, resuspended in 20 μl of 1× murine leukemia virus (MLV) reverse transcriptase (RT) buffer [60 mM Tris (pH 8.3), 24 mM dithiothreitol, 0.7 mM MnCl2, 75 mM NaCl, 0.06% NP-40, 6 μg/ml oligo(dT), 12 μg/ml poly(rA)], plus a 0.5 mM concentration of the deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), and 1 μl of RNasin was added. After 2 min at 42°C, 200 U of MLV RT (Promega) was added. The reaction mixture was incubated at 42°C for 50 min and stopped by heating to 70°C for 15 min; then the samples were ethanol precipitated, run on a denaturing 8% polyacrylamide sequencing gel, and exposed to a phosphorimager screen.

RESULTS

Minimal virus-like particles contain a fragment of 7SL.

We previously reported that 7SL RNA is present in minimal virus-like particles and wild-type (WT) HIV-1 at indistinguishable levels (30). However, several subsequent studies, which also examined minimal VLPs for 7SL, observed vastly reduced or undetectable levels (3, 8, 36, 38, 39). In our initial work here, we sought to resolve these differences. Our earlier study used an RNase protection assay (RPA) to detect 7SL RNA, whereas 7SL was detected via RT-PCR in other published studies (Fig. 1b). The region protected by the RPA probe and the regions amplified by the reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) primers were not equivalent. We reasoned that the discrepancies could be explained if only a fragment of 7SL—one that was recognized by the RPA probe but not encompassed by the RT-PCR primers—was present in minimal VLPs.

To test this notion, the RNA content of authentic HIV-1 Gag particles and minimal VLPs was examined by Northern blotting (Fig. 2 a). Virus-like particles were produced by transient transfection of VLP expression plasmids into 293T cells. The constructs used were a series developed by Accola et al. (1) to address minimal, assembly-competent forms of HIV-1. As a positive control, intact Gag was provided by a Ψ-negative proviral construct, pCMVΔR8.2 (27). RNA was isolated from extracellular particles enriched by centrifugation through a sucrose cushion and examined by Northern blotting. The Northern blot was first probed with a radiolabeled oligonucleotide specific to the S domain of 7SL (Fig. 2b). The results showed that while both virions containing intact Gag and virus-like particles with minimal Gag packaged full-length 7SL, the principal components of minimal VLPs were three fragments of 7SL, with the primary fragment migrating at approximately 100 nucleotides (nt) and two slightly larger fragments at lower abundance (Fig. 2b, **, *, and 7SLrem). The same blot was then stripped and reprobed with an oligonucleotide specific to the Alu domain of 7SL (Fig. 2c); this revealed only a small amount of full-length 7SL in the minimal VLPs and no smaller fragments, indicating that the VLPs did not contain detectable fragments of 7SL which contain the Alu domain. Further probing of this blot, using a probe specific to the top strand of the 7SL linker region and a portion of the contiguous S domain, revealed only the largest of the three fragments (Fig. 2d), indicating that the increase in size comes from additional nucleotides on the 5′ end of the fragments.

Quantifying probe hybridized to VLP RNA indicated that 2% of the total 7SL in the minimal VLPs was full-length, the largest fragment was 9%, the second-largest fragment was 8%, and the smallest fragment was 81% of the total of both the full-length and fragmented 7SL proteins. We have termed the smallest and most abundant fragment 7SL remnant, or 7SLrem.

Comparing the amount of 7SLrem in VLPs (Fig. 2b, lanes 12 to 16) to the signal in an equal volume of virions containing authentic Gag (lane 9) suggested that the molar amount of 7SL RNA and 7SL RNA derivatives in authentic and minimal Gag particles differed by less than 2-fold. It should be noted that, whereas the changes introduced into some of these minimal VLP constructs were initially reported to result in large reductions in particle release (1), several other investigators have reported subsequently that under high-level transfection in 293T cells, effects on virus release are not observed (reviewed in reference 12). Our laboratory's previous Western blot analyses of particles released from 293T cells transfected with the series of constructs used here have confirmed that particle release is not impaired detectably for these constructs, including the NC deletion, ΔNCp1, and the NC replacement, Zwt-p6 (30). These findings on virus release were confirmed in immunoprecipitation controls performed in support of the current work (data not shown).

No change in size or distribution of 7SLrem was detected in early-harvest virus collected from virus-producing cells 1 h after a change to fresh medium, compared to virus harvested after 24 h (data not shown), indicating that the apparent processing of 7SL to 7SLrem likely occurred at or before particle release.

The primary fragment of 7SL contained in minimal VLPs corresponds to 111 nt of the S domain.

The RNA contents from virions containing intact Gag produced by the proviral vector pCMVΔR8.2, VLPs containing intact Gag produced by the Gag-only expression plasmid pVR1012x/s Gag/h, or minimal VLPs produced by pZwt-p6 were compared further to determine the identity of 7SLrem. Specifically, the 3′ and 5′ ends of 7SL were mapped by S1 nuclease digestion and primer extension, respectively.

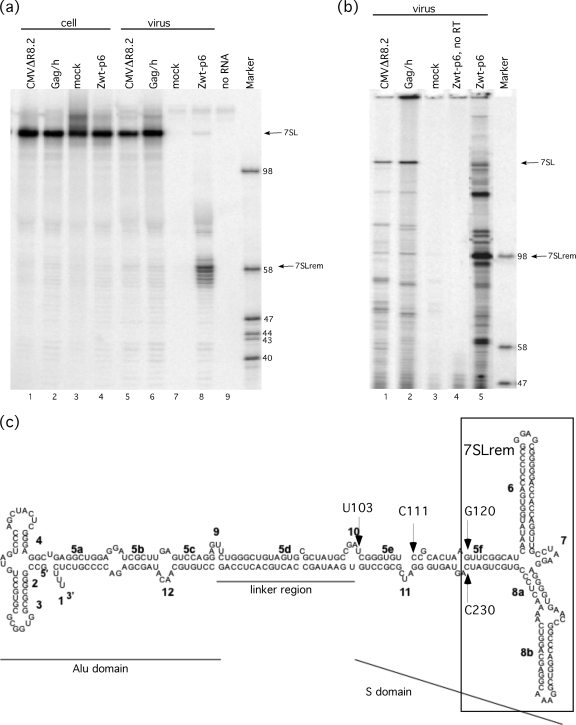

Figure 3 a shows the results of S1 mapping used to determine the 3′ end of 7SLrem. As evidenced by the 129-base fragment in lanes 1 to 6, all cell samples and both virions and VLPs that contain intact Gag contained only full-length 7SL and no detectable 7SLrem. This suggests that 7SLrem is not present as a discrete species within cells. Furthermore, the presence of intact 7SL RNA in VLPs that lack protease (Fig. 3a, lane 6) demonstrated that Gag processing is not required for incorporation of intact 7SL. The major band isolated from the minimal VLP Zwt-p6 (lane 8) was 58 bases, which indicated that the 3′ end of 7SLrem was C230.

FIG. 3.

Identification of 7SLrem. (a) Sequencing gel of RNA fragments that have been hybridized to a probe specific to helix 8 of 7SL and digested with S1 nuclease in order to determine the 3′ end of 7SLrem. (b) Sequencing gel of RNA fragments that have been hybridized to an oligonucleotide specific to helix 8 of 7SL and a primer extended by murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase in order to determine the 5′ end of 7SLrem. (c) A schematic of 7SL showing the 5′ and 3′ ends of 7SLrem determined as described above, as well as the inferred ends of the two larger 7SL fragments (indicated by arrows).

Figure 3b shows results of the primer extension analysis used to map the 5′ end of 7SLrem. Similar to the blot shown in Fig. 3a, the major band in both species containing intact Gag, CMVΔR8.2 and Gag/h (Fig. 3b, lanes 1 and 2), which was 216 bases, corresponds to full-length 7SL. The major band from the minimal VLP Zwt-p6 (lane 5) is 98 bases, which indicates that the 5′ end of 7SLrem was G120. Whether the numerous minor bands visualized for the Zwt-p6 sample were due to pausing by RT on this highly structured RNA, alternate 7SL cleavage products, or other causes was not determined. The 5′ ends of the two larger fragments were not determined with precision, but based on their mobilities on gels and hybridization patterns with additional probes (Fig. 2d), they were indicated to be approximately C111 and U103. Therefore, 7SLrem can be mapped to 111 nt contained within the S domain of 7SL (Fig. 3c).

Full-length 7SL is present in ΔMA mutants containing NC, and 7SLrem is present in ΔMAΔNC mutants.

The Gag mutants used in the above experiments retained the N-terminal 12 amino acids of MA to promote membrane localization. Thus, work with these mutants could not rule out interactions between 7SL and these residues of MA. Therefore, we examined the RNA content of viruses which did not contain any portion of MA. In the mutant Gag proteins used here, the first 10 amino acids of Fyn kinase were fused onto the polyprotein N terminus in order to recapitulate the membrane binding function of MA (Fig. 4 a). Fyn(10) constructs recruit myristate moieties as MA does in the context of Gag, as well as two palmitate moieties, allowing binding to the plasma membrane, viral assembly, and release of viral particles (5).

The RNA content of Fyn(10) VLPs was examined by Northern blotting (Fig. 4b). In virions produced by Fyn(10) constructs that contained an intact NC domain (Fig. 4b, lanes 9 and 10), full-length 7SL was present at levels comparable to those found in VLPs containing authentic Gag expressed by the plasmid pVR1012x/s Gag/h (lane 8). In virions produced by Fyn(10) constructs which were lacking the NC domain (Fig. 4b, lanes 11 and 12), 7SLrem was present at levels comparable to those found in the minimal VLP ΔZwt (lane 13), regardless of whether the constructs contained the MA domain. Although these data were not normalized for viral particle production and band intensities are therefore not indicative of molar amounts of 7SL and 7SLrem, these data demonstrate that the packaging of neither full-length nor processed 7SL was dependent upon any portion of matrix.

DISCUSSION

We have examined the RNA content of minimal virus-like particles and determined that they contain three fragments of 7SL RNA. The primary fragment, termed 7SLrem, mapped to 111 nt within the S domain of 7SL, and the two secondary fragments were approximately 8 nt and 15 nt longer on the 5′ end. 7SLrem was not detected in cells, nor does 7SL contain any regulatory sequences known to be capable of expressing only the 7SLrem region (11). Therefore, intact 7SL is probably the species recruited during assembly, and 7SLrem is likely processed from full-length 7SL while in association with viral components. This work was performed using virions produced by the highly transfectable 293T cell type, which is known to release highly elevated levels of minimal VLPs (12). Due to the low yield of these VLPs from cells other than 293T cells, we have been unable to test the universality of the 7SLrem phenotype thus far.

Previous work assessing the RNA content of minimal VLPs yielded contradictory results, with nuclease protection revealing 7SL in minimal VLPs (30) but RT-PCR repeatedly failing to detect 7SL under similar circumstances (3, 8, 36, 38, 39). The data here resolve this conflict by demonstrating that while full-length 7SL is present in only small amounts in minimal VLPs, discrete 7SL fragments are observed in VLPs at the same molar levels as intact 7SL in authentic Gag particles. This explains why a probe previously used to detect 7SL by RPA (30), which lies within the primary, and smallest, fragment of 7SL in VLPs, did detect this RNA, whereas the primers used for RT-PCR, which lie either completely or partially outside the retained sequence, detected little or no 7SL. In the study by Crist et al., the primers used lay completely outside the 7SL fragments reported here, and no 7SL was detected in minimal VLPs (8). In Wang et al. (38, 39) primers lay outside all but the largest retained fragment. Our results (Fig. 2b) suggest that this largest of the 7SL fragments, plus intact 7SL, comprised 11% of the total 7SL in the VLPs, which is in good agreement with the approximately 10-fold decrease reported in Wang et al. (38, 39). Bach et al. used two sets of primers, one completely outside the retained fragments and one outside all but the largest retained fragment, and reported 7SL levels in VLPs reduced 2- or 12-fold relative to levels in WT virions (3). Crist et al. not only failed to detect appreciable 7SL but also presented data showing no detectable RNA of any sort present in minimal VLPs. However, the reagent they used to monitor RNA, RiboGreen (Invitrogen), has been demonstrated to have low efficiency at quantifying RNAs around 100 bases or shorter, which is the approximate size of 7SLrem (18). The dependency of the packaging of the cytosine deaminase APOBEC3G on NC reported by Wang et al. (40) and Bach et al. (3) may also be explained by 7SLrem, and there is some evidence that packaging of APOBEC3G by HIV-1 may be dependent on 7SL (38, 40), although this remains controversial (19).

The ends of 7SLrem map to bulges in the secondary structure of the full-length 7SL RNA where nucleotides remain unpaired. This, combined with the apparent precision with which the ends of 7SLrem are cleaved, implies processing by a single-strand endonuclease. This endonuclease cannot be viral RNase H as 7SLrem is found in Gag-only particles that lack this enzyme. Although no endonuclease has yet been identified in viral particles, the genomic RNA of retroviruses is often nicked when released from virions, implying encounters with an endonuclease (7, 28). Whether this endonuclease is the same as the endonuclease that appears to be acting on 7SL and whether the endonuclease(s) in question is packaged into viral particles or associate only during assembly remain to be determined.

It is interesting that the same processing of 7SL occurs whether the minimal VLP lacks only NC (as in ΔNCp1) or lacks the majority of Gag (ΔZwt). This indicates that nucleocapsid plays a role in protecting the full-length RNA from processing. This protection does not require maturation to NCp7, as Gag+ PR− VLPs contained intact 7SL. It has been established that mutations to NC, specifically to the conserved CCHC motif of the zinc finger domains, severely reduce the packaging of genomic RNA and result in the production of noninfectious virus (reviewed in reference 35). When examined by electron microscopy, these viral particles exhibit a disordered, globular core rather than the compact, cone-shaped structure seen in WT particles (15). NC zinc finger mutants exhibit severe budding delays and can initiate reverse transcription before the virion has fully released from the host cell (34). The proposed model for NC regulation of reverse transcription is that the CCHC motifs of NC zinc fingers promote the formation of a highly condensed core structure whereby reverse transcription is prevented until the dissolution of such a structure upon entry into the target cell (25). Such a model may explain 7SL processing in ΔNC VLPs as well. Without the dense core structure produced by a fully intact NC domain, the endonuclease responsible for processing 7SL into 7SLrem may be able to function.

The processed forms of 7SL were retained in VLPs even when only a few domains of Gag were present. The VLP containing the least amount of Gag studied here (ΔZwt) contained only 8 amino acids of matrix, the C-terminal domain of capsid, and spacer protein 1. A role for the 8 amino acids of MA were ruled out using Fyn(10) constructs. Thus, the determinants of 7SL recruitment into HIV-1 must be either the C-terminal domain (CTD) of CA and/or SP1 and/or the myristate moiety attached to the N terminus of the polyprotein or resulting membrane localization. It remains to be shown whether 7SLrem interacts directly with Gag or is retained in the virion through other means, such as in complex with another protein present in the viral particle.

Acknowledgments

We thank V. Larson for her help in mapping the ends of 7SLrem, G. N. Llewellyn for his help with immunoprecipitation, and H. G. Göttlinger, V. Chukkapalli, and A. Ono for their generous gifts of viral constructs.

This work was supported by NIH grant R21 AI080276 and a Gates Grand Challenges Exploration Grant to A.T and NIH grant T32 GM 07544 to S.E.K.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 7 July 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Accola, M. A., B. Strack, and H. G. Gottlinger. 2000. Efficient particle production by minimal Gag constructs which retain the carboxy-terminal domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid-p2 and a late assembly domain. J. Virol. 74:5395-5402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aldovini, A., and R. A. Young. 1990. Mutations of RNA and protein sequences involved in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 packaging result in production of noninfectious virus. J. Virol. 64:1920-1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bach, D., S. Peddi, B. Mangeat, A. Lakkaraju, K. Strub, and D. Trono. 2008. Characterization of APOBEC3G binding to 7SL RNA. Retrovirology 5:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berkowitz, R., J. Fisher, and S. P. Goff. 1996. RNA packaging. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 214:177-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chukkapalli, V., I. B. Hogue, V. Boyko, W. S. Hu, and A. Ono. 2008. Interaction between the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag matrix domain and phosphatidylinositol-(4,5)-bisphosphate is essential for efficient Gag membrane binding. J. Virol. 82:2405-2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cimarelli, A., S. Sandin, S. Hoglund, and J. Luban. 2000. Basic residues in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid promote virion assembly via interaction with RNA. J. Virol. 74:3046-3057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coffin, J. M. 1979. Structure, replication, and recombination of retrovirus genomes: some unifying hypotheses. J. Gen. Virol. 42:1-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crist, R. M., S. A. Datta, A. G. Stephen, F. Soheilian, J. Mirro, R. J. Fisher, K. Nagashima, and A. Rein. 2009. Assembly properties of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag-leucine zipper chimeras: implications for retrovirus assembly. J. Virol. 83:2216-2225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cross, B. C., I. Sinning, J. Luirink, and S. High. 2009. Delivering proteins for export from the cytosol. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10:255-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D'Souza, V., and M. F. Summers. 2005. How retroviruses select their genomes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:643-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Englert, M., M. Felis, V. Junker, and H. Beier. 2004. Novel upstream and intragenic control elements for the RNA polymerase III-dependent transcription of human 7SL RNA genes. Biochimie 86:867-874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freed, E. O. 2002. Viral late domains. J. Virol. 76:4679-4687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganser-Pornillos, B. K., M. Yeager, and W. I. Sundquist. 2008. The structural biology of HIV assembly. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 18:203-217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green, J. M., and K. Struhl. 1992. S1 Analysis of messenger RNA using single-stranded DNA probes, p. 4-14. In F. M. Ausubel, R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.), Short protocols in molecular biology, 2nd ed. John Wiley and Sons, New York, NY. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Grigorov, B., D. Decimo, F. Smagulova, C. Pechoux, M. Mougel, D. Muriaux, and J. L. Darlix. 2007. Intracellular HIV-1 Gag localization is impaired by mutations in the nucleocapsid zinc fingers. Retrovirology 4:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Houzet, L., J. C. Paillart, F. Smagulova, S. Maurel, Z. Morichaud, R. Marquet, and M. Mougel. 2007. HIV controls the selective packaging of genomic, spliced viral and cellular RNAs into virions through different mechanisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:2695-2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang, Y., W. P. Kong, and G. J. Nabel. 2001. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific immunity after genetic immunization is enhanced by modification of Gag and Pol expression. J. Virol. 75:4947-4951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones, L. J., S. T. Yue, C. Y. Cheung, and V. L. Singer. 1998. RNA quantitation by fluorescence-based solution assay: RiboGreen reagent characterization. Anal. Biochem. 265:368-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan, M. A., R. Goila-Gaur, S. Opi, E. Miyagi, H. Takeuchi, S. Kao, and K. Strebel. 2007. Analysis of the contribution of cellular and viral RNA to the packaging of APOBEC3G into HIV-1 virions. Retrovirology 4:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kleiman, L. 2002. tRNA(Lys3): the primer tRNA for reverse transcription in HIV-1. IUBMB Life 53:107-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lever, A., H. Gottlinger, W. Haseltine, and J. Sodroski. 1989. Identification of a sequence required for efficient packaging of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA into virions. J. Virol. 63:4085-4087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linial, M. L., and A. D. Miller. 1990. Retroviral RNA packaging: sequence requirements and implications. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 157:125-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luirink, J., and I. Sinning. 2004. SRP-mediated protein targeting: structure and function revisited. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1694:17-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mak, J., and L. Kleiman. 1997. Primer tRNAs for reverse transcription. J. Virol. 71:8087-8095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mougel, M., L. Houzet, and J. L. Darlix. 2009. When is it time for reverse transcription to start and go? Retrovirology 6:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muriaux, D., J. Mirro, D. Harvin, and A. Rein. 2001. RNA is a structural element in retrovirus particles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:5246-5251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naldini, L., U. Blomer, P. Gallay, D. Ory, R. Mulligan, F. H. Gage, I. M. Verma, and D. Trono. 1996. In vivo gene delivery and stable transduction of nondividing cells by a lentiviral vector. Science 272:263-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Onafuwa-Nuga, A., and A. Telesnitsky. 2009. The remarkable frequency of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genetic recombination. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 73:451-480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Onafuwa-Nuga, A. A., S. R. King, and A. Telesnitsky. 2005. Nonrandom packaging of host RNAs in Moloney murine leukemia virus. J. Virol. 79:13528-13537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Onafuwa-Nuga, A. A., A. Telesnitsky, and S. R. King. 2006. 7SL RNA, but not the 54-kd signal recognition particle protein, is an abundant component of both infectious HIV-1 and minimal virus-like particles. RNA 12:542-546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ono, A., S. D. Ablan, S. J. Lockett, K. Nagashima, and E. O. Freed. 2004. Phosphatidylinositol (4,5) bisphosphate regulates HIV-1 Gag targeting to the plasma membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:14889-14894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peluso, P., D. Herschlag, S. Nock, D. M. Freymann, A. E. Johnson, and P. Walter. 2000. Role of 4.5S RNA in assembly of the bacterial signal recognition particle with its receptor. Science 288:1640-1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peluso, P., S. O. Shan, S. Nock, D. Herschlag, and P. Walter. 2001. Role of SRP RNA in the GTPase cycles of Ffh and FtsY. Biochemistry 40:15224-15233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas, J. A., W. J. Bosche, T. L. Shatzer, D. G. Johnson, and R. J. Gorelick. 2008. Mutations in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein zinc fingers cause premature reverse transcription. J. Virol. 82:9318-9328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas, J. A., and R. J. Gorelick. 2008. Nucleocapsid protein function in early infection processes. Virus Res. 134:39-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tian, C., T. Wang, W. Zhang, and X. F. Yu. 2007. Virion packaging determinants and reverse transcription of SRP RNA in HIV-1 particles. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:7288-7302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang, S. W., and A. Aldovini. 2002. RNA incorporation is critical for retroviral particle integrity after cell membrane assembly of Gag complexes. J. Virol. 76:11853-11865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang, T., C. Tian, W. Zhang, K. Luo, P. T. Sarkis, L. Yu, B. Liu, Y. Yu, and X. F. Yu. 2007. 7SL RNA mediates virion packaging of the antiviral cytidine deaminase APOBEC3G. J. Virol. 81:13112-13124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang, T., C. Tian, W. Zhang, P. T. Sarkis, and X. F. Yu. 2008. Interaction with 7SL RNA but not with HIV-1 genomic RNA or P bodies is required for APOBEC3F virion packaging. J. Mol. Biol. 375:1098-1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang, T., W. Zhang, C. Tian, B. Liu, Y. Yu, L. Ding, P. Spearman, and X. F. Yu. 2008. Distinct viral determinants for the packaging of human cytidine deaminases APOBEC3G and APOBEC3C. Virology 377:71-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zwieb, C., and E. Ullu. 1986. Identification of dynamic sequences in the central domain of 7SL RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 14:4639-4657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]