Abstract

We developed and evaluated flocked nasal midturbinate swabs obtained from 55 asymptomatic and 108 symptomatic volunteers. Self-collected swabs obtained from asymptomatic volunteers yielded numbers of respiratory epithelial cells comparable to those of staff-collected nasal (n = 55) or nasopharyngeal (n = 20) swabs. Specific viruses were detected in swabs self-collected by 42/108 (38.9%) symptomatic volunteers by multiplex PCR.

We report herein the design and evaluation of a novel self-collected nasal midturbinate swab for respiratory virus diagnosis. We previously demonstrated that Copan flocked nasopharyngeal swabs (NPS) collected significantly more respiratory epithelial cells than conventional rayon swabs and improved sample collection for direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) testing of respiratory viruses (2). We observed that the cell yield obtained from sampling the nose using a flocked swab designed for nasopharyngeal sampling was equivalent to that obtained from nasopharyngeal sampling using rayon NPS. This led us to hypothesize that a flocked nasal swab designed to contact a larger nasal surface area would further improve cell sampling and enable self-collection.

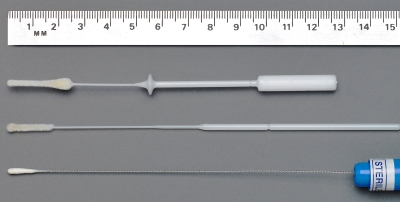

We measured the nasal passages of adult white cadavers at the Michael G. DeGroote School of Medicine anatomy laboratory, McMaster University, and designed a tapered cone-shaped swab with a greater length and diameter of flocked nylon (Fig. 1). A collar was added at 5.5 cm as a guide to maximum insertion depth for adults. The nasal swab samples a large surface area of respiratory mucosa, covering the inferior and middle turbinate bones, and is now commercially available in pediatric and adult sizes (FLOQSwabs; Copan Italia S.p.A., Brescia, Italy).

FIG. 1.

Flocked nasal midturbinate swab (top) compared to flocked nasopharyngeal (middle) and rayon nasopharyngeal (bottom) swabs, used for both nasal and nasopharyngeal sampling.

Our primary study objectives were to determine the feasibility, acceptability, and performance characteristics of self-sampled nasal midturbinate swabs. We tested the adequacy of self-collected flocked nasal swabs, the equivalence of nasal and nasopharyngeal sampling, and the diagnostic yield for specific respiratory viruses by multiplex PCR. The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Board at St. Joseph's Healthcare, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

To examine the adequacy of respiratory specimen self-collection, 55 healthy asymptomatic adult volunteers were recruited from hospital staff and visitors. After providing signed informed consent, volunteers self-collected two flocked nasal swabs by following the printed instructions with illustrations. Each swab was inserted up to 5.5 cm, as tolerated, into the same nostril of their choice. An experienced staff member then collected the following two additional nasal swabs, using the opposite nostril in randomized order: a flocked midturbinate nasal swab and a rayon pernasal swab. A self-administered questionnaire assessed the ease of self-collection, discomfort, and swab preferences.

All four nasal swabs were placed into universal transport medium (UTM; Copan Italia S.p.A.) and coded to maintain blinding. Samples were processed identically, according to current DFA testing protocols. Briefly, specimens were vortexed and centrifuged, and the pellet was resuspended in buffered saline. A total of 25 μl of suspension was added to glass slide wells, air dried, fixed, and stained with the negative control for DFA testing (Diagnostic Hybrids, Athens, OH). Respiratory epithelial cells were counted and averaged over four high-powered fields (HPF) at 400× magnification (2). No viral diagnostics were performed on swabs obtained from asymptomatic volunteers.

As shown in Table 1, cell yields varied significantly between the four nasal swabs collected (P < 0.001; one-way analysis of variance [ANOVA]). The first and second self-collected nasal swabs yielded mean epithelial cell counts ± standard deviations (SD) of 67 ± 43 and 117 ± 65 cells/HPF, respectively (P = 0.001; Dunnett's post hoc test). An adequate specimen, defined as >25 cells/HPF (7), was obtained with 48/55 (87.3%) first self-collected swabs and 54/55 (98.2%) second self-collected swabs. Staff-collected flocked nasal and rayon pernasal swabs yielded 136 ± 51 and 38 ± 25 cells/HPF, respectively (P < 0.001). The first self-collected nasal swab was superior to the staff-collected rayon swab (P = 0.001) but collected fewer cells than either the second self-collected swab (P < 0.001) or the staff-collected flocked nasal swab (P < 0.001). There was no significant difference between the second self-collected flocked nasal swab and the staff-collected flocked nasal swab (mean difference, >−14 cells/HPF; 95% confidence interval [CI], −46 to +18; P = 0.80).

TABLE 1.

Mean respiratory epithelial cell yields and beta-actin levels among volunteers sampled by self- or staff-collected swabs

| No. of volunteers | Mean log10 beta-actin DNA copies/reaction ± SD |

Mean no. of cells/HPF ± SD |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-collected nasal swabs |

Staff-collected nasal swabs |

Staff-collected NPS |

Self-collected nasal swabs |

Staff-collected nasal swabs |

Staff-collected NPS |

|||||||

| First flocked | Second flocked | Flocked | Rayon | Flocked | Rayon | First flocked | Second flocked | Flocked | Rayon | Flocked | Rayon | |

| 55 | 67 ± 43 | 117 ± 65 | 136 ± 51 | 38 ± 25 | ||||||||

| 20a | 4.48 ± 0.58 | 4.69 ± 0.46 | 4.82 ± 0.34 | 4.09 ± 0.36 | 4.83 ± 0.31 | 4.25 ± 0.33 | 86 ± 45 | 144 ± 55 | 136 ± 53 | 36 ± 22 | 145 ± 44 | 55 ± 30 |

A total of 20/55 volunteers consented to NPS sampling.

To directly compare self- and staff-collected nasal swabs to NPS, 20/55 asymptomatic volunteers consented to staff-collected NPS collection (Table 1). Immediately after obtaining the two self-collected and two staff-collected nasal swabs, staff collected the following two additional swabs in randomized order: a flocked pernasal NPS and a rayon pernasal NPS. Self-collected nasal swabs were obtained using one nostril, and all four staff-collected specimens were obtained used the opposite nostril. Among these 20 subjects, cell yields were significantly different among the 6 swabs (P < 0.001; one-way ANOVA). The mean cell yields ± SD obtained were 86 ± 45 and 144 ± 55 cells/HPF for the first and second self-collected flocked midturbinate nasal swabs, respectively (P < 0.001); 136 ± 53 and 36 ± 22 cells/HPF for staff-collected flocked and rayon nasal swabs, respectively (P < 0.001); and 145 ± 44 and 55 ± 30 cells/HPF for flocked and rayon NPS, respectively (P < 0.001). The first self-collected flocked swab cell yield was higher than that for rayon nasal swabs (P = 0.001) and comparable to that for rayon NPS (P = 0.96) but collected fewer cells than the second self-collected flocked nasal swab or the flocked NPS (all P = 0.003). The second self-collected flocked nasal swab was superior to the rayon NPS (P < 0.001) and equivalent to the flocked NPS (P = 0.89). The higher yield of the second self-collected swab, compared with that of the first one, may have reflected an increase in confidence of self-collection or perhaps an effect of “cleaning” from the first swab.

As an additional measure of sample adequacy, we quantitated beta-actin gene DNA copies by PCR (6) from the 20 volunteers undergoing concurrent nasal and nasopharyngeal sampling (Table 1). Epithelial cell counts were highly correlated with log-transformed beta-actin copy numbers (R = 0.9; P < 0.001). Beta-actin concentrations were similar in self- or staff-collected flocked nasal swabs and flocked NPS but lower in rayon nasal swabs or rayon NPS (P < 0.001).

A total of 65% of volunteers reported no or mild discomfort from self-swabbing, with the remainder reporting moderate (31%) or severe (4%) discomfort. Eighty-seven percent reported little or no difficulty in self-swabbing. Only 24% of volunteers preferred staff collection, 40% stated a preference for self-swabbing, and 36% expressed no preference.

To evaluate the self-collected flocked nasal swabs for diagnosis of viral infections, 250 hospital volunteers were given a kit consisting of two flocked nasal swabs, UTM, and printed instructions. Volunteers self-swabbed twice using the same nostril and placed swabs into appropriately labeled UTM. Over the following year, 108 symptomatic volunteers self-swabbed within 3 days of acute respiratory infection symptoms and returned the swabs within 5 days. We previously demonstrated that swabs in UTM are suitable for PCR diagnosis for 14 days at room temperature (K. Luinstra, unpublished data). Specimens were batch extracted with NucliSens easyMAG (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) and tested with the xTAG respiratory virus panel (Luminex, Austin, TX), which detects 16 virus types and subtypes (9).

A total of 42/108 (38.9%) symptomatic volunteers had viruses detected in their nasal swabs, including 25 rhino/enteroviruses, 3 influenza A viruses (one seasonal H1, one seasonal H3, and one pandemic H1N1 A/swine/California/04/2009 virus), 2 influenza B viruses, 3 metapneumoviruses, 5 coronaviruses (two 229E, one HKU1, and two NL63 viruses), and 1 each of respiratory syncytial virus type A, parainfluenza 2, parainfluenza 3, and adenovirus.

Among the 42 volunteers diagnosed with respiratory viruses, 35 submitted two swabs, and 7 submitted a single swab. Concordant virus infections were detected with both swabs in 29/35 (82.9%) volunteers (P = 1.0; McNemar test). For 6 volunteers with discrepant swab results, 3 were positive with the first swab (one rhino/enterovirus, one respiratory syncytial virus subgroup A [RSV A], and one pandemic H1N1 virus), while 3 were positive with the second swab (all rhino/enteroviruses). Thus, the first and second self-collected swabs were equivalent for diagnosing respiratory virus infections by multiplex PCR, despite the lower cell yields of first versus second self-collected swabs in asymptomatic volunteers. We did not perform antigen testing on nasal swabs, and the adequacy of first and second nasal swabs for antigen-based testing requires further research.

In summary, self-collected flocked nasal swabs were equivalent to staff-collected nasal swabs or NPS and superior to rayon NPS—the traditional reference standard—using respiratory epithelial cell yield as a proxy for specimen adequacy. Self-swabbing was feasible without previous training. Coupled with multiplex PCR, self-collection enabled early diagnosis of many symptomatic volunteers with common respiratory viruses.

These findings expand on those of previous studies of nasal sampling in children (1, 4, 5, 8, 10) and have implications for the diagnosis and study of respiratory viruses. First, nasal self-sampling was simple, was preferred to staff collection, and may enable testing of more people earlier in the course of their illnesses. Earlier testing may facilitate timely antiviral treatment for influenza and reduce influenza-associated complications and hospitalizations (3). Second, self-testing eliminates any biohazard to clinical staff from specimen collection, potentially reducing transmission to health care personnel. Third, as nasal swabs are minimally invasive, serial sampling may be feasible for outbreak investigations or for studies of transmission or response to therapy. We did not compare the diagnostic yield of nasal swabs to that of NPS among hospitalized patients and do not recommend them for such patients without further study.

In conclusion, the new flocked nasal midturbinate swab enabled self-collection of high-quality samples and facilitated the diagnosis of respiratory virus infections by PCR.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR).

We thank our volunteers for participating and Copan Italia, Brescia, Italy, for contributing all swabs and media.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 7 July 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abu-Diab, A., M. Azzeh, R. Ghneim, R. Ghneim, M. Zoughbi, S. Turkuman, N. Rishmawi, A. E. R. Issa, I. Siriani, R. Dauodi, R. Kattan, and M. Y. Hindiyeh. 2008. Comparison between pernasal flocked swabs and nasopharyngeal aspirates for detection of common respiratory viruses in samples from children. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:2414-2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daley, P., S. Castriciano, M. Chernesky, and M. Smieja. 2006. Comparison of flocked and rayon swabs for collection of respiratory epithelial cells from uninfected volunteers and symptomatic patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:2265-2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harper, S. A., J. S. Bradley, J. A. Englund, T. M. File, S. Gravenstein, et al. 2009. Seasonal influenza in adults and children—diagnosis, treatment, chemoprophylaxis, and institutional outbreak management: clinical practice guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48:1003-1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heikkinen, T., A. A. Salmi, and O. Ruuskanen. 2001. Comparative study of nasopharyngeal aspirate and nasal swab specimens for detection of influenza. BMJ 322:138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heikkinen, T., J. Marttila, A. A. Salmi, and O. Ruuskanen. 2002. Nasal swab versus nasopharyngeal aspirate for isolation of respiratory viruses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:4337-4339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jobin, C., S. Haskill, L. Mayer, A. Panja, and R. B. Sartor. 1997. Evidence of altered regulation of I kappa B alpha degradation in human colonic epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 158:226-234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landry, M. L., and D. Ferguson. 2003. Suboptimal detection of influenza virus in adults by the Directigen Flu A+B enzyme immunoassay and correlation of results with the number of antigen-positive cells detected by cytospin immunofluorescence. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3407-3409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macfarlane, P., J. Denham, J. Assous, and C. Hughes. 2005. RSV testing in bronchiolitis: which nasal sampling method is best? Arch. Dis. Child. 90:634-635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahony, J., S. Chong, F. Merante, S. Yaghoubian, T. Sinha, C. Lisle, and R. Janeczko. 2007. Development of a respiratory virus panel test for detection of twenty human respiratory viruses by use of multiplex PCR and a fluid microbead-based assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:2965-2970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spyridaki, I. S., I. Christodoulou, L. de Beer, V. Hovland, M. Kurowski, et al. 2009. Comparison of four nasal sampling methods for the detection of viral pathogens by RT-PCR-A GA(2)LEN project. J. Virol. Methods 156:102-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]