Abstract

The frequency of acute HIV infection (AHI) among HIV-1 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)-negative samples received from general hospital patient admissions was assessed. Of 3,005 samples pooled for nucleic acid testing, a prevalence of 0.13% was found. Pooled nucleic acid testing may be feasible for low-cost identification of AHI in high-prevalence settings.

The prevalence of HIV infection in the general South African population above 2 years of age was estimated at 10.9% in 2008, showing a degree of stabilization compared with 2005 figures (10.8%) (1). Despite such a high prevalence, acute HIV infection (AHI), characterized by the absence of anti-HIV antibodies, is rarely diagnosed (15). The situation is even further complicated by a lack of symptoms or the presence of nonspecific symptoms within the patient (8), leading to most individuals being unaware of their HIV status (16).

AHI represents the period during which initial HIV-1 reservoirs are established in anatomical sites of the body (12) and is associated with transiently high viremia that increases the probability of sexual transmission (4, 17). HIV-1 viral loads after acquisition of infection frequently are in excess of 1 million RNA copies/ml (log 6.0 copies/ml) (11).

To facilitate earlier initiation of surveillance and treatment strategies and enhance prevention efforts, diagnosis of AHI should be a primary concern (16). In the past, strategies for detecting AHI have included identification of “at-risk” patients with mononucleosis-like symptoms or monitoring high-risk cohorts over time, “waiting” for seroconversion or the onset of symptoms (6). Both of these strategies have proven inadequate. To efficiently detect HIV in the pre-seroconversion phase of infection requires nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) to detect HIV RNA before antibodies develop. Implementation of NAAT over and above standard antibody assays has been shown to increase detection of AHI by 8% (14, 16). However, NAAT is currently not routine for adult HIV diagnosis due to its costs and the specialized laboratory infrastructure needed to perform these tests (2).

Grouping NAAT by pooling samples together and testing the entire pool will lead to a decrease in the average number of tests performed and may also lead to higher specificity and positive predictive values (3, 18).

In 2004, Motloung et al. proposed the adoption of NAAT pooling for detecting AHI in high-risk groups as a possible way of curbing transmission rates in the context of a low-resource environment (7). Karim et al. in 2007 went on to demonstrate the benefit of such a pooling strategy for identifying AHI in a “high-risk” cohort in South Africa, where 23 of 245 sex workers monitored over time were diagnosed with AHI (5). A similar study performed among patients attending primary health care clinics in Johannesburg, for treatment of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), showed 0.99% of individuals were acutely infected. This translated to an incidence rate of 12.9% per year and enforced the feasibility of using pooled NAAT testing in this context (15).

Pooling reduces the total cost per individual specimen tested, but the impact of this cost needs to be determined, especially in the developing world. More recently, a study in China (Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region) (19) showed an extra cost of $2.90 per specimen screened using a pooled NAAT strategy and $6,575.00 per additional case of AHI identified among patients at STD clinics. This approach supported the feasibility of using pooled RNA testing but added that cost-effectiveness should be carefully considered.

We have conducted a study of HIV-1 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)-negative samples randomly received from a tertiary hospital's general patient admissions to investigate the frequency of AHI in a high-HIV-endemicity hospital laboratory setting and to determine whether routine pooling of NAAT is warranted.

Serum samples from all patients admitted to the Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital, sent to the Microbiology Laboratory at the National Health Laboratory Service (NHLS) for routine HIV ELISA, were collected and pooled into lots of 20. A total of 3,005 samples were received between the years 2007 and 2008 which had been tested by the Abbott Axsym fourth-generation ELISA (Abbott Laboratories, Wiesbaden-Delkenheim, Germany).

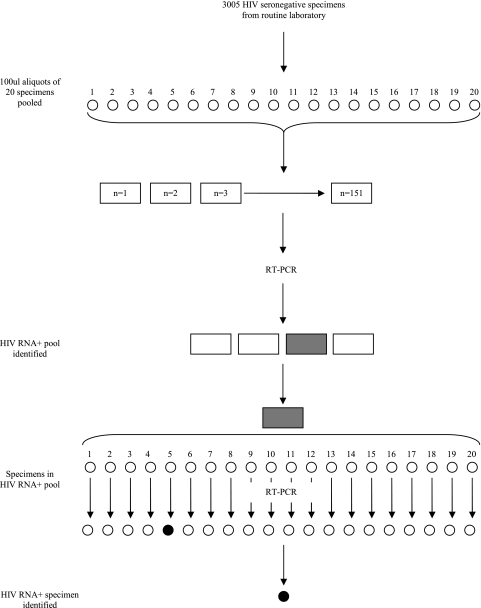

The NAAT pooling strategy adopted for this study is illustrated in Fig. 1. An amount of 100 μl from each of 20 serum samples was pooled to create a final specimen pool volume of 2 ml. Each pool was tested for viral load quantification using the COBAS Ampliprep/COBAS Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor test version 1.5 standard (F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Diagnostics Division, Basel, Switzerland), which has a dynamic range of 400 to 750,000 copies/ml. If a pool tested negative, all specimens in that pool were declared negative. If a pool tested positive, each specimen in that pool was retested individually for confirmation of positive specimens. Acute infection was defined by an HIV-1 RNA-positive result paired with an HIV antibody-negative result.

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram of the NAAT pooling strategy. RT-PCR, reverse transcription-PCR.

Out of 151 pools tested (n = 3,005), 3 pools tested positive for HIV RNA and were individually tested. This resulted in four HIV RNA-positive samples with viral loads determined beyond the limits of the assay from 8.41E1 to 3.43E3 to 1.19E4 and 1.87E6 copies/ml.

There are clear advantages to group testing strategies, especially within high-throughput laboratories. Primarily, pooling strategies can increase the specificity of RNA assays as they lead to repeat testing of the specimens during deconstruction of the pools (2), as well as lowering the cost needed per test.

In this study, the prevalence of AHI is 0.13% (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.258 to 0.002%). Although lower than that in the first study performed in STD clinics, which are high-risk areas (15), this prevalence is still relatively high considering the cohort arose from all hospital admissions and not from “high-risk” populations. This prevalence was, however, much higher than those found in China (0.04%) (19) and the United States (0.06%) (9).

Although the Abbott fourth-generation ELISA has increased sensitivity in seroconverters, the detection of two samples classified as AHI by definition in this study, which had low viral loads, may be explained by deterioration of RNA under storage conditions typical of plasma tested by ELISA (4°C).

In the Chinese study (19), the cost of AHI case detection varies depending on the HIV prevalence within each population setting. In South Africa, the laboratory cost for an HIV ELISA is R126.50 (∼$17.10). In this study, 211 nucleic acid tests were sufficient to screen 3,005 specimens and diagnose 4 acute cases at a cost per test of R756.41 (∼$102.22) compared to a total testing cost of R159,602.51 (∼$21,567.91) for individual testing. The pooling cost relates to an added R53 ($7.16) per specimen screened, over and above ELISA, using this particular pooling strategy. The adoption of a different testing algorithm—for example, one similar to that employed by Pilcher et al. (10)—may further help to decrease costs.

When one looks at the lifetime and overall cost of treatment of an advanced case of late-diagnosed HIV presenting with complications versus the lifetime cost of treating a patient with early diagnosis, the benefits become far more apparent (such as earlier access to treatment and reduction in opportunistic infections). The lifetime cost of treating an HIV-positive person in the developed world was estimated at ∼$618,000.00 (2004 U.S. dollars), of which 73% of the total cost accounts for antiretroviral (ARV) treatment, 13% accounts for inpatient care, and 9% accounts for outpatient care (13). This calculation does not take into account costs due to loss in productivity and the patient's time. In addition, considering acutely infected patients are 10 times more likely to transmit HIV per coital act than those individuals with established infection (17), diagnosis of AHI not only will allow earlier initiation of treatment strategies and lead to increased survival benefits but also may help curb secondary infection by identifying exposed sexual partners suitable for postexposure prophylaxis (10).

To reduce transmission rates of HIV, identification of persons with acute infection should be a priority. Therefore, we indicate that pooling strategies integrated with antibody testing would be cost-effective for laboratories with large testing volumes compared to individual testing. Targeting high-risk groups and pregnant women, which conventional ELISA methods may miss, could have a further impact on cost-effectiveness.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by the generous support of the American people through the U.S. Agency for International Development.

The contents of this article are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the U.S. government.

We thank Lara Noble for assistance with the collection and pooling of samples.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 7 July 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.AVERT. Accessed January 2010. AIDS and HIV informaton from AVERT. AVERT, Horsham, United Kingdom. http://www.avert.org/safricastats.htm.

- 2.Fiscus, S. A., C. D. Pilcher, W. C. Miller, K. A. Powers, I. F. Hoffman, M. Price, D. A. Chilongozi, C. Mapanje, R. Krysiak, S. Gama, F. E. Martinson, and M. S. Cohen. 2007. Rapid, real-time detection of acute HIV infection in patients in Africa. J. Infect. Dis. 195:416-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghirardini, A., M. Pagano, R. Bellocco, E. Litvak, M. Gonzales, and X. Tu. 1998. Cost effectiveness of pooling blood samples for HIV screening among blood donors, abstr. 33201. Int. Conf. AIDS, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 4.Gray, R. H., M. J. Wawer, R. Brookmeyer, N. K. Sewankambo, D. Serwadda, F. Wabwire-Mangen, T. Lutalo, X. Li, T. vanCott, and T. C. Quinn. 2001. Probability of HIV-1 transmission per coital act in monogamous, heterosexual, HIV-1-discordant couples in Rakai, Uganda. Lancet 357:1149-1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karim, S. S., K. Mlisana, A. B. Kharsany, C. Williamson, C. Baxter, and Q. A. Karim. 2007. Utilizing nucleic acid amplification to identify acute HIV infection. AIDS 21:653-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lavreys, L., M. L. Thompson, H. L. Martin, Jr., K. Mandaliya, J. O. Ndinya-Achola, J. J. Bwayo, and J. Kreiss. 2000. Primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection: clinical manifestations among women in Mombasa, Kenya. Clin. Infect. Dis. 30:486-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Motloung, T., M. Myers, F. Venter, S. Delany, H. Rees, and W. Stevens. 2004. Identifying acute HIV infection—a major new public health challenge. S. Afr. Med. J. 94:531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patterson, K. B., P. A. Leone, S. A. Fiscus, J. Kuruc, S. I. McCoy, L. Wolf, E. Foust, D. Williams, J. J. Eron, and C. D. Pilcher. 2007. Frequent detection of acute HIV infection in pregnant women. AIDS 21:2303-2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pilcher, C. D., S. A. Fiscus, T. Q. Nguyen, E. Foust, L. Wolf, D. Williams, R. Ashby, J. O. O'Dowd, J. T. McPherson, B. Stalzer, L. Hightow, W. C. Miller, J. J. Eron, Jr., M. S. Cohen, and P. A. Leone. 2005. Detection of acute infections during HIV testing in North Carolina. N. Engl. J. Med. 352:1873-1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pilcher, C. D., J. T. McPherson, P. A. Leone, M. Smurzynski, J. Owen-O'Dowd, A. L. Peace-Brewer, J. Harris, C. B. Hicks, J. J. Eron, Jr., and S. A. Fiscus. 2002. Real-time, universal screening for acute HIV infection in a routine HIV counseling and testing population. JAMA 288:216-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pilcher, C. D., M. A. Price, I. F. Hoffman, S. Galvin, F. E. Martinson, P. N. Kazembe, J. J. Eron, W. C. Miller, S. A. Fiscus, and M. S. Cohen. 2004. Frequent detection of acute primary HIV infection in men in Malawi. AIDS 18:517-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pilcher, C. D., H. C. Tien, J. J. Eron, Jr., P. L. Vernazza, S. Y. Leu, P. W. Stewart, L. E. Goh, and M. S. Cohen. 2004. Brief but efficient: acute HIV infection and the sexual transmission of HIV. J. Infect. Dis. 189:1785-1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schackman, B. R., K. A. Gebo, R. P. Walensky, E. Losina, T. Muccio, P. E. Sax, M. C. Weinstein, G. R. Seage III, R. D. Moore, and K. A. Freedberg. 2006. The lifetime cost of current human immunodeficiency virus care in the United States. Med. Care 44:990-997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stekler, J. D., P. D. Swenson, R. W. Coombs, J. Dragavon, K. K. Thomas, C. A. Brennan, S. G. Devare, R. W. Wood, and M. R. Golden. 2009. HIV testing in a high-incidence population: is antibody testing alone good enough? Clin. Infect. Dis. 49:444-453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens, W., E. Akkers, M. Myers, T. Motloung, C. D. Pilcher, and F. Venter. 2005. High prevalence of undetected, acute HIV infection in a South African primary health care clinic, abstr. MoOa0108. IAS Conf. HIV Pathog. Treat., Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

- 16.Truong, H. M., R. M. Grant, W. McFarland, T. Kellogg, C. Kent, B. Louie, E. Wong, and J. D. Klausner. 2006. Routine surveillance for the detection of acute and recent HIV infections and transmission of antiretroviral resistance. AIDS 20:2193-2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wawer, M. J., R. H. Gray, N. K. Sewankambo, D. Serwadda, X. Li, O. Laeyendecker, N. Kiwanuka, G. Kigozi, M. Kiddugavu, T. Lutalo, F. Nalugoda, F. Wabwire-Mangen, M. P. Meehan, and T. C. Quinn. 2005. Rates of HIV-1 transmission per coital act, by stage of HIV-1 infection, in Rakai, Uganda. J. Infect. Dis. 191:1403-1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Westreich, D. J., M. G. Hudgens, S. A. Fiscus, and C. D. Pilcher. 2008. Optimizing screening for acute human immunodeficiency virus infection with pooled nucleic acid amplification tests. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:1785-1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yin, Y. P., X. S. Chen, H. C. Wang, M. Q. Shi, W. H. Wei, B. Y. Zhu, Y. H. Yu, J. D. Tucker, and M. S. Cohen. 2008. Detection of acute HIV infections among sexually transmitted disease clinic patients: a practice in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China. Sex. Transm. Infect. 84:350-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]