Abstract

Mannheimia glucosida, M. haemolytica, and M. ruminalis were isolated from cases of acute mastitis in ewes. M. glucosida was found to be a common cause of clinical mastitis in sheep. Selected phenotypic tests in addition to genotyping were needed to definitively identify Mannheimia species causing ovine mastitis.

Mastitis is an important disease of sheep in dairy, wool, and meat production systems. Several studies have found that the prevalence of Mannheimia haemolytica as a cause of ovine mastitis is similar to or greater than that of Staphylococcus aureus (6, 7, 13, 14). In a preliminary study, our laboratory also demonstrated the significance of this species in mastitis in Poll Dorset ewes in southeastern Australia (7).

The genus Mannheimia contains several species from the family Pasteurellaceae that have been recently reclassified (4). The five named species within this genus are M. haemolytica, M. glucosida, M. ruminalis, M. varigena, and M. granulomatis (4). There are also several unnamed taxa that are distinct from these named species (2).

M. haemolytica is regarded as the most important species in this genus, as it is the major organism involved in pneumonia in feedlot cattle (10) and can cause pneumonia and mastitis in sheep (10, 14). The former species Pasteurella haemolytica was separated into two biotypes, A and T, based on the capacity to ferment arabinose or trehalose and the results of some other phenotypic tests (19). Sixteen serotypes within these two biotypes were originally defined using indirect hemagglutination assays (10), with a new serotype, A17, added later (22). Biotype A was divided into 9 biogroups (1). Biogroup 1 of the former P. haemolytica was later renamed M. haemolytica and includes serotypes 1, 2, 5 to 9, 12 to 14, and 16 (4, 5). Serotypes 3, 4, 10, and 15 of biotype T of the former P. haemolytica were classified as P. trehalosi (20) and later as Bibersteinia trehalosi (9).

Serotype A11, as well as biogroups 3A to H and 9 of the former P. haemolytica, were reclassified as M. glucosida (1), which is a heterogeneous species that has been isolated from in ruminants case of pneumonia (2) and from the nasal cavities of healthy sheep (2, 18).

M. ruminalis has not been associated with disease and can be isolated from the rumen of sheep (2), and M. ruminalis-like organisms have been isolated from the nasal cavities of healthy sheep (18).

This study investigated the phenotypic and genetic characteristics of Mannheimia species isolated from cases of clinical mastitis in sheep, with the aim of definitively identifying the most prevalent species responsible for this disease.

Twenty-four bacterial isolates from cases of mastitis, mainly in Poll Dorset ewes, were used in this study. The isolates were all Gram-negative rods with no significant growth on MacConkey agar and produced mucoid, gray colonies on sheep blood agar (SBA). Seventeen were from a previous survey of mastitis in Poll Dorset ewes (7), and the other seven isolates were collected from ewes with mastitis in 2008. The isolates were from 8 different farms, which were designated A to F, H, and I.

Each isolate was grown on SBA at 37°C overnight. A set of discriminative biochemical tests were chosen based on data from previous studies (1, 2, 8). The type strains of M. haemolytica and M. ruminalis (kindly provided by Pat Blackall) were used as positive controls, and uninoculated broths were used as negative controls. All tests were performed in duplicate and repeated twice. Peptone-sugar media were made using standard methods. India ink wet-film staining was used to detect the presence of a capsule (11).

The presence of the leukotoxin gene (lktA) was investigated using a pair of primers to amplify the full coding region and part of the flanking region of lktA (Table 1). Amplification was performed with 50-μl reaction mixtures containing 1 μM (each) primers, 200 μM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), 1.5 μM MgSO4, 5 μl of 10× High-Fidelity PCR buffer, and 1.5 U of Platinum Taq high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Promega). The DNA template was obtained by extracting DNA from an overnight growth of each strain in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth using High Pure PCR template preparation kits (Roche). Reaction mixtures were incubated at 94°C for 1 min and then subjected to 35 cycles of 94°C for 45 s, 60°C for 45 s, and 68°C for 3.5 min, followed by a final extension step at 72°C for 7 min. PCR products were visualized by electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel.

TABLE 1.

Primers used for amplification of two housekeeping genes, rpoB and rrnA, and the lktA (leukotoxin) gene

All strains were subjected to phylogenetic analysis by amplification and sequencing of two housekeeping genes, rpoB and rrnA (the 16S rRNA gene) (15, 16). The primers used are listed in Table 1. Amplification was performed in 25-μl volumes containing 1 μM (each) primers for rpoB or 0.25 μM (each) primers for rrnA, 200 μM (each) dNTPs, 2 μM MgCl2, 5 μl of 5× GoTaq Flexi buffer, and 1 U of Taq polymerase (Promega). A single colony was used as the template for the reaction. Amplification was performed in a Bio-Rad thermal cycler. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 94°C for 1 min and then subjected to 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 52°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 45 s for amplification from rpoB and 60 s for amplification from rrnA, with a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. Amplified DNA was purified using Qiaex II gel purification kits (Qiagen), and sequencing reactions were performed using BigDye Terminator version 3.1 kits.

Sequences were compared and aligned with published sequences for type strains (Table 2). Maximum-likelihood analysis was performed using the DNAml program in the Phylip package, and the best transition-transversion ratio was determined based on the value that yielded the best log likelihood. Bootstrap analysis of each set of sequences (from 100 resamplings) was performed using Phylip. Nucleotide distances were calculated using the Jukes-Cantor gamma distance model in MEGA version 4 (21), assuming that the rate of nucleotide substitution was the same for all pairs of the four nucleotides.

TABLE 2.

Mannheimia type strain sequences used for phylogenetic analysis

| Gene | Species | Strain | GenBank accession no. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rpoB | M. haemolytica | ATCC 33396 | AY170217.1 | 3 |

| M. glucosida | CCUG38457 | AY362959 | 15 | |

| M. ruminalis | CCUG38470 | AY362961 | 15 | |

| M. varigena | CCUG38462 | AY362962 | 15 | |

| M. granulomatis | ATCC 49244 | AY362960 | 15 | |

| rrnA | M. haemolytica | PH213a | DQ301920.1 | 17 |

| M. haemolytica | NCTC9380b | M75080 | 12 | |

| M. glucosida | CCUG38457 | AY362912 | 15 | |

| M. glucosida | P733 | AF053892 | 4 | |

| M. ruminalis | CCUG38470 | AF053900 | 4 | |

| M. varigena | CCUG38462 | AF053893 | 4 | |

| M. granulomatis | ATCC 49244 | AY362913 | 15 |

Serotype A1.

Serotype A2.

A summary of the phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of the isolates is shown in Table 3. Isolates were divided into those that produced and those that did not produce β-glucosidase. Nine (A2, A3, A4, A5, B1, D2, F1, H1, and H2) of these 24 isolates were β-glucosidase positive and also hydrolyzed selected glycosides.

TABLE 3.

Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of isolates of Mannheimia species from animals with ovine mastitis

| Characteristic | Resultb for: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. haemolytica (12 isolates) | M. glucosida (9 isolates) | M. ruminalis (2 isolates) | M. ruminalis-like strain (1 isolate) | |

| Beta-hemolysisa | w | w | − | w |

| Oxidase | + | + | − | + |

| Ornithine decarboxylase | − | V (6) | − | − |

| β-Glucosidase | − | + | − | − |

| Acid from: | ||||

| l-Arabinose | − | V (6) | + | + |

| Trehalose | − | − | − | − |

| Maltose | +/w | V (6) | V (1) | + |

| l-(+)-Rhamnose | − | − | V (1) | − |

| d-Sorbitol | +/w | + | − | + |

| d-Xylose | +/w | + | − | + |

| Hydrolysis of: | ||||

| Esculin | − | + | − | − |

| Salicin | − | + | − | − |

| Presence of capsule | + | + | + | + |

| lktA gene | + | + | − | + |

Hemolysis on SBA.

V, variable (numbers in parentheses show the number of isolates yielding a positive reaction); +, positive results within 2 days; w, weakly positive.

Twelve l-arabinose-negative isolates had similar capacities to ferment other selected sugars and were identified as M. haemolytica. All isolates were encapsulated. A 3-kbp product was amplified using the lktA PCR from all isolates except A6 and A7.

The distances between the DNA sequences of the rpoB genes from all the isolates obtained from cases of ovine mastitis and the rpoB genes from M. varigena and M. granulomatis were 9 to 12%, so these two species were omitted from phenotypic comparisons and phylogenetic analyses. Twelve isolates (C1, C2, C3, E1, G1, G2, I1, I2, F2, D1, A8, and A9) had rpoB sequences identical to that of M. haemolytica but could be divided into three groups on the basis of one or two nucleotide differences in their rrnA genes.

The distance between the rpoB sequences from isolates A6 and A7, which showed no hemolysis on SBA and were phenotypically similar to M. ruminalis, and that from M. ruminalis was 1.9%, but the distances between the rrnA sequences from these isolates, as well as that from isolate A1, which showed hemolysis on SBA, and that from M. ruminalis were less than 1%.

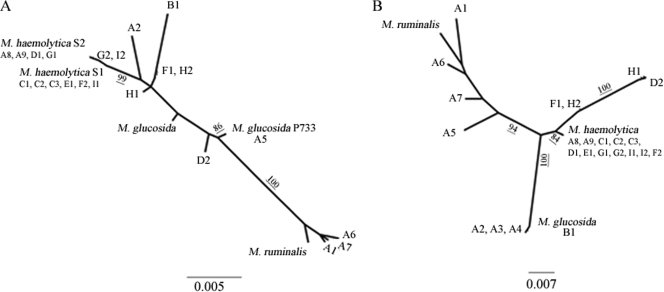

Of the β-glucosidase-producing isolates, A2, A3, A4, and B1 were the most similar to M. glucosida (with 0.2, 0.2, 0.2, and 0% nucleotide distances between rpoB sequences, respectively). The distance between the rpoB gene sequence from isolate A5 and that from M. glucosida was 5%, but the rrnA sequence from A5 was identical to that from M. glucosida strain P733. Phylogenetic trees for rrnA and rpoB sequences are shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Maximum-likelihood trees for rrnA (A) and rpoB (B) gene sequences, assuming transition-transversion ratios of 1.2 and 5, respectively. Bootstrap values for each branch are shown when they are greater than 75%.

The results of this study have established that M. glucosida is a significant cause of ovine mastitis. Previous studies have demonstrated the importance of Mannheimia (Pasteurella) species in ovine mastitis (6, 7, 13, 14). In 1998, Jones and Watkins (13) isolated different serotypes of M. (P.) haemolytica, including serotype A11, from cases of ovine mastitis in the United Kingdom. Nine (37.5%) of 24 Mannheimia isolates in our study were M. glucosida, with 6 isolated in pure culture, suggesting that this species can be as significant a cause of ovine mastitis as M. haemolytica.

In the study from which these isolates were derived, 74 of 166 milk samples from ewes with clinical mastitis yielded cultivable bacteria, 48 of which were Mannheimia species, 12 of these being M. glucosida. Only 1 of 1,900 milk samples from clinically healthy ewes yielded M. glucosida, and this sample had a somatic cell count of 6.7 million cells/ml. Thus, Mannheimia species and M. glucosida are significantly more prevalent in milk from ewes with acute mastitis than in milk from clinically normal ewes (P < 0.000001; Fisher's exact test).

The classification M. glucosida includes other members of the former P. haemolytica classification, in addition to members of serotype A11, and some strains within this species are not typeable by indirect hemagglutination. Thus, our study has established the association between this species and ovine mastitis for the first time since the definition of the species was published. M. glucosida is a heterogeneous species but is consistently β-glucosidase and meso-inositol positive. The M. glucosida isolates in our study differed in their capacities to ferment l-arabinose and produce ornithine decarboxylase.

There are no previous reports of any association between M. ruminalis and disease. Although the milk samples yielded light growths of the M. ruminalis and M. ruminalis-like organisms, the isolates were obtained in pure culture from animals with mastitis on the same farm.

To assess whether the isolates that were not M. haemolytica had any of the known virulence factors of M. haemolytica, we examined them for the presence of a capsule as well as the structural gene for the leukotoxin. The hemolytic M. ruminalis isolate (A1) and all the M. glucosida and M. haemolytica isolates contained the lktA gene. Although the two nonhemolytic M. ruminalis isolates did not contain the lktA gene, they, like all the other isolates, were encapsulated.

Korczak et al. suggested that rpoB sequences were more reliable for discrimination between genera within the family Pasteurellaceae than rrnA sequences (with 10 to 12% difference between rpoB gene sequences from different genera, compared to 6 to 7% between rrnA gene sequences) (15). M. haemolytica isolates were easily identified using rpoB sequencing, but identification of M. glucosida and M. ruminalis remained difficult, with some isolates, such as A5, unable to be identified to the species level. The phenotypic and genotypic heterogeneity of strains of M. glucosida suggests that this classification may consist of more than one taxon.

Definitive identification of isolates in this genus remains difficult (2), and we found that multiple phenotypic tests, including tests for production of β-glucosidase and ornithine decarboxylase, fermentation of l-arabinose, d-sorbitol, and d-xylose, and hydrolysis of salicin and esculin, were needed for differentiation of M. glucosida from M. haemolytica and M. ruminalis whenever there was any doubt about identification of isolates based on rpoB and rrnA sequences.

Acknowledgments

We thank Pat Blackall, Animal Research Institute, Queensland, Australia, for providing the reference strains.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 July 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angen, Ø., B. Aalbaek, E. Falsen, J. E. Olsen, and M. Bisgaard. 1997. Relationships among strains classified with the ruminant Pasteurella haemolytica-complex using quantitative evaluation of phenotypic data. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. 285:459-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angen, Ø., P. Ahrens, and M. Bisgaard. 2002. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of Mannheimia (Pasteurella) haemolytica-like strains isolated from diseased animals in Denmark. Vet. Microbiol. 84:103-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angen, Ø., P. Ahrens, P. Kuhnert, H. Christensen, and R. Mutters. 2003. Proposal of Histophilus somni gen. nov., sp. nov. for the three species incertae sedis ‘Haemophilus somnus’, ‘Haemophilus agni’ and ‘Histophilus ovis’. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:1449-1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angen, Ø., R. Mutters, D. A. Caugant, J. E. Olsen, and M. Bisgaard. 1999. Taxonomic relationships of the [Pasteurella] haemolytica complex as evaluated by DNA-DNA hybridizations and 16S rRNA sequencing with proposal of Mannheimia haemolytica gen. nov., comb. nov., Mannheimia granulomatis comb. nov., Mannheimia glucosida sp. nov., Mannheimia ruminalis sp. nov. and Mannheimia varigena sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 49:67-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angen, Ø., M. Quirie, W. Donachie, and M. Bisgaard. 1999. Investigations on the species specificity of Mannheimia (Pasteurella) haemolytica serotyping. Vet. Microbiol. 65:283-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arsenault, J., P. Dubreuil, R. Higgins, and D. Belanger. 2008. Risk factors and impacts of clinical and subclinical mastitis in commercial meat-producing sheep flocks in Quebec, Canada. Prev. Vet. Med. 87:373-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barber, S., J. Allen, P. Mansell, and G. Browning. 2006. Mastitis in the ewe, p. 127-132. In Proceedings of the Australian Sheep Veterinarians 2006 Conferences, vol. 16. Australian Sheep Veterinarians, Eight Mile Plains, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blackall, P. J., M. Bisgaard, and C. P. Stephens. 2002. Phenotypic characterisation of Australian sheep and cattle isolates of Mannheimia haemolytica, Mannheimia granulomatis and Mannheimia varigena. Aust. Vet. J. 80:87-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blackall, P. J., A. M. Bojesen, H. Christensen, and M. Bisgaard. 2007. Reclassification of [Pasteurella] trehalosi as Bibersteinia trehalosi gen. nov., comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57:666-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyce, J. D., R. Y. C. Lo, I. Wilkie, and B. Adler. 2004. Pasteurella and Mannheimia. In C. L. Gyles, J. F. Prescott, J. G. Songer, and C. O. Theon (ed.), Pathogenesis of bacterial infection, 3rd ed. Blackwell Publishing, Ames, IA.

- 11.Cowan, S. T., and K. J. Steel. 1965. Manual for the identification of medical bacteria. Cambridge University Press, London, United Kingdom.

- 12.Dewhirst, F. E., B. J. Paster, I. Olsen, and G. J. Fraser. 1993. Phylogeny of the Pasteurellaceae as determined by comparison of 16S ribosomal ribonucleic acid sequences. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. 279:35-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones, J. E. T., and G. H. Watkins. 1998. Studies on mastitis in sheep at the Royal Veterinary College, p. 83-90. In Proceedings of the Sheep Veterinary Society Committee Spring Meeting 1998, Scarborough, Yorkshire. Sheep Veterinary Society, Penicuik, United Kingdom.

- 14.Kirk, J. H., and J. S. Glenn. 1996. Mastitis in ewes. Compend. Contin. Educ. Pract. Vet. 18:582-591. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Korczak, B., H. Christensen, S. Emler, J. Frey, and P. Kuhnert. 2004. Phylogeny of the family Pasteurellaceae based on rpoB sequences. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54:1393-1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuhnert, P., S. E. Capaul, J. Nicolet, and J. Frey. 1996. Phylogenetic positions of Clostridium chauvoei and Clostridium septicum based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 46:1174-1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larsen, J., A. G. Pedersen, H. Christensen, M. Bisgaard, Ø. Angen, P. Ahrens, and J. E. Olsen. 2007. Evidence for vertical inheritance and loss of the leukotoxin operon in genus Mannheimia. J. Mol. Evol. 64:423-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poulsen, L. L., T. M. Reinert, R. L. Sand, M. Bisgaard, H. Christensen, J. E. Olsen, S. Stuen, and A. M. Bojesen. 2006. Occurrence of haemolytic Mannheimia spp. in apparently healthy sheep in Norway. Acta Vet. Scand. 47:70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith, G. R. 1961. The characteristics of two types of Pasteurella haemolytica associated with different pathological conditions in sheep. J. Pathol. Bacteriol. 81:431-440. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sneath, P. H. A., and M. Stevens. 1990. Actinobacillus rossii sp. nov., Actinobacillus seminis sp. nov., nom., rev., Pasteurella bettii sp. nov., Pasteurella lymphangitidis sp. nov., Pasteurella mairi sp. nov., and Pasteurella trehalosi sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 40:148-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tamura, K., J. Dudley, M. Nei, and S. Kumar. 2007. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24:1596-1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Younan, M., and L. Fodar. 1995. Characterisation of a new Pasteurella haemolytica serotype (A17). Res. Vet. Sci. 58:98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]