Abstract

A large number of dendritic cell (DC) subsets have now been identified based on the expression of a distinct array of surface markers as well as differences in functional capabilities. More recently, the concept of unique subsets has been extended to the lung, although the functional capabilities of these subsets are only beginning to be explored. Of particular interest are respiratory DCs that express CD103. These cells line the airway and act as sentinels for pathogens that enter the lung, migrating to the draining lymph node, where they add to the already complex array of DC subsets present at this site. Here we assessed the contributions of these individual populations to the generation of a CD8+ T-cell response following respiratory infection with poxvirus. We found that CD103+ DCs were the most effective antigen-presenting cells (APC) for naive CD8+ T-cell activation. Surprisingly, we found no evidence that lymph node-resident or parenchymal DCs could prime virus-specific cells. The increased efficacy of CD103+ DCs was associated with the increased presence of viral antigen as well as high levels of maturation markers. Within the CD103+ DCs, we observed a population that expressed CD8α. Interestingly, cells bearing CD8α were less competent for T-cell activation than their CD8α− counterparts. These data show that lung-migrating CD103+ DCs are the major contributors to CD8+ T-cell activation following poxvirus infection. However, the functional capabilities of cells within this population differ with the expression of CD8, suggesting that CD103+ cells may be divided further into distinct subsets.

In order for the body to mount an adaptive immune response to a pathogen, T cells circulating through lymph nodes (LN) must be alerted to the presence of infection in the periphery. This occurs as a result of presentation of pathogen-derived epitopes on professional antigen-presenting cells (APC), primarily dendritic cells (DC). The DC that reside in the tissue continually sample the local environment for the presence of foreign/pathogenic antigens. In a noninfected tissue, DC exist in an immature state, i.e., they are highly phagocytic and have low levels of expression of costimulatory molecules (3). Following an encounter with infection-associated signals, e.g., pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and/or inflammatory cytokines, DC undergo maturation (3). This process results in upregulation of chemokine receptors, which promotes trafficking to the lymph node, as well as increased expression of costimulatory molecules and cytokines, which are necessary accessory signals for the activation of naive T cells (2, 3).

Unlike many other tissues, the lung is constantly assaulted with foreign antigens, both environmental and infectious. This includes a large number of viruses which spread via aerosolized droplets. As such, it is critical to understand how the immune system detects these infections and subsequently elicits an efficacious adaptive CD8+ T-cell response. While an important role for DC as the activators of naive T cells is clear, the contribution of distinct DC subsets in this process is less understood. Multiple DC subsets are present within the lung draining lymph nodes, and as such, all are potential regulators of T-cell activation (for a review, see references 14 and 32). These subsets are either resident in the lymph node or present at this site as a result of migration from the periphery, in this case, the lung. These DC subsets are defined by the array of molecules expressed at their surface. Among the subsets resident within the lymph nodes are those which express CD8α or CD4 or are double negative (express neither CD4 nor CD8α) (32). These subsets appear to be segregated in their capabilities to elicit T-cell responses. For example, previous studies have suggested that CD8α+ DC are the predominant DC subset involved in priming CD8+ T cells (4), while CD8α − CD4+ DC are more important in the regulation of CD4+ T cells (31). Further, CD8α+ DC are efficient at cross-presentation, a property shown to be critical in the generation of CD8+ T-cell responses in a number of infectious models (24, 33).

In addition to LN-resident populations, lung-resident DC that have migrated to the lymph node following infection make up a significant portion of LN DC. CD103 (an αE integrin)-expressing DC reside at the airway mucosa and surrounding pulmonary vessels (35). In contrast, CD103− CD11b+ DC are restricted to the lung parenchyma. Given the relatively recent identification of these distinct lung-resident DC populations, there is limited information available regarding their role in T-cell activation following infection. However, they have been assessed in several models, including influenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and Bordetella pertussis (1, 5, 15, 19, 23, 26, 37). At present, the relative contributions of migrating versus resident DC populations remain controversial. Earlier studies reported a role for LN-resident CD8α+ DC in priming naive CD8+ T cells in addition to lung-migrating DC (5). More recently, however, studies have suggested that activating potential is restricted primarily to lung-migrating DC (1, 23). The underlying cause of these discrepancies is currently unknown but may reflect differences in the markers used to identify the DC subsets or in the individual infection models. Regardless, our understanding of the role of these subsets remains incomplete.

We have analyzed the migration and maturation of DC following respiratory infection with the orthopoxvirus vaccinia virus (VV). These studies revealed that airway-resident CD103+ DC were the most efficient activators of virus-specific CD8+ T cells. Further studies determined that this was the result of both increased access to viral antigen and increased maturation within this subset. In our analyses, we found no evidence to support a role for LN-resident CD8α+ DC or lung-migrating CD11b+ DC in T-cell activation. Further, we found that CD103+ DC were heterogeneous with regard to their functional capabilities. Interestingly, this correlated with the expression of CD8α. While more-recent studies have found CD8α expression on CD103+ DC (30), none have looked at the functional capabilities of these cells separately from those of CD8α− CD103+ DC. Our findings are the first to suggest that CD8α expression within the CD103+ population may identify a distinct subset that differs in its functional capabilities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

C57BL/6 mice (Frederick Cancer Research Facility, National Cancer Institute, Fredrick, MD) were used throughout this study. OT-I mice were from a colony established with breeding pairs obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were maintained in the Wake Forest University School of Medicine animal facilities, under specific-pathogen-free conditions and in accordance with approved IACUC protocols. Mice used for these studies were between 6 and 10 weeks of age.

Virus and infection.

The recombinant VV.NP-S-eGFP virus was the kind gift of Jack Bennink (NIH). This virus expresses a fusion protein containing the NP protein from influenza virus, the SIINFEKL epitope from ovalbumin, and enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) (28). The recombinant VV.M and VV.P viruses express the M and P proteins from simian virus 5 (SV5), respectively, and were constructed on site, as previously described (17). For infection, mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of avertin, followed by intranasal administration of 1 × 107 PFU of virus in a volume of 50 μl. Mock-infected mice received equivalent volumes of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Intratracheal (i.t.) infections were performed following anesthetization with isoflurane by delivery of 107 PFU of virus in 30 μl PBS. Mice recover from infection with this dose of VV.NP-S-eGFP and generate a CD8+ T-cell response (our unpublished data).

Intratracheal instillation of Cell Tracker Orange.

Five hours following i.t. infection with vaccinia virus, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, and 50 μl of 1 mM Cell Tracker Orange (CTO) (Molecular Probes) was administered intratracheally. When the DC from the mediastinal LN (MLN) were analyzed on day 2 postinfection (p.i.), this pulse with CTO resulted in 9.7% ± 1.7% of the eGFP+ DC costaining for CTO.

DC isolation from the mediastinal LN.

At various days postinfection as indicated in the figures, MLN were isolated and pooled within each experimental condition. The tissue was mechanically disrupted and allowed to incubate in complete media supplemented with 1 mg/ml collagenase D (Roche) for 45 min at 37°C. Cells were then passed through a 70-μm nylon cell strainer (BD Falcon). Red blood cells (RBC) were removed by treatment with ACK lysis buffer (Lonza).

Analysis of DC maturation.

Cells obtained from the MLN following collagenase digestion were incubated for 5 h in the presence of GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences). Following the incubation, cells were stained with a combination of CD11c-allophycocyanin (HL3; BD) or phycoerythrin (PE)/Cy7 (HL3; BD), CD103-PE (M290; BD), CD11b-PE/Cy7 (M1/70; Biolegend), CD86-Pacific Blue (GL-1; BioLegend), CD80-PE (16-10A1; BD), and CD90.2-biotin (53-2.1; BD). Streptavidin 525 Qdots (Molecular Probes) were used to detect biotinylated antibodies. Expression of these fluorophores, along with eGFP expression from the virus, was assessed using a BD FACSCanto II instrument. Data were analyzed using FacsDiva software (BD Biosciences).

Naive T-cell activation.

Prior to sorting, CD11c-expressing cells were enriched by positive selection using a Miltenyi column system. Enriched populations were routinely 45 to 65% CD11c+. The enriched population was stained with CD11c-allophycocyanin and a combination of the following: CD8α-peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP)-Cy5.5, CD8α-V450, CD103-PE, CD103-PerCP-Cy5.5, and CD11b-PE/Cy7 along with biotinylated CD19, CD90.2, and CD49b antibodies (all from BD Biosciences). Streptavidin 525 Qdots (Molecular Probes) were used to detect biotinylated antibodies. Cells positive for the 525 Qdots were gated out of the analysis prior to sorting. This approach was shown in preliminary studies to increase purity in the isolated DC subsets. Thus, all sorted cells met the criteria of CD11c+ CD90.2− CD49b− CD19−. For the analysis of lung-derived cells in the lymph node, DC were sorted into four populations based on the presence of Cell Tracker Orange and the expression of CD103 and CD11b. For the analysis of CD8α+ CD103+ versus CD8α− CD103+ DC, cells were sorted based on CD8α and CD103 expression. All sorts utilized a BD FACsAria cell sorter, and all sorted cells were CD11c+ CD90.2− CD49b− CD19−. Sorted populations were routinely 94 to 99% pure. To assess the ability of the DC subsets to induce naive T-cell activation, carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labeled OT-I T cells were cocultured with sorted DC populations at a ratio of 1:5 DC-OT-I cells in a V-bottomed, 96-well plate. Cells were incubated for 60 h at 37°C. Following incubation, cells were stained with anti-CD8α-PerCP-Cy5.5 and anti-CD90.2-allophycocyanin antibodies. Samples were acquired using a BD FACsCalibur instrument. FlowJo softare (Treestar, Inc.) was used for analysis of cell division.

RESULTS

Respiratory infection with vaccinia virus results in a generalized increase in DC in the MLN.

Poxviruses are known to express an array of immunoregulatory molecules (10). These include numerous cytokine receptor homologs, inhibitors of complement, and chemokine binding proteins (10). As such, we first examined whether respiratory infection with the poxvirus vaccinia virus resulted in an influx of DC into the MLN, as has been reported for influenza virus infection (7). Mice were intranasally infected with a recombinant vaccinia virus construct (VV.NP-S-eGFP) expressing a fusion protein containing the influenza virus nucleoprotein, the Ova257-264 immunodominant ovalbumin epitope (SIINFEKL), and eGFP (28). MLN were harvested on days 1 to 4 postinfection (p.i.) and DC recovered following enzymatic digestion in the presence of collagenase D. The number of CD11c+ cells was calculated using flow cytometric data and the total number of cells recovered from the tissue (Fig. 1A). CD90.2+, CD19+, and CD49b+ cells were excluded by gating. As expected, by day 1 p.i., there was a significant increase in the number of CD11c+ cells in the MLN (Fig. 1A). The number of DC was similar at day 2 p.i., with a detectable, although not significant, transient decrease on day 3. MLN from animals at day 4 p.i. contained the largest number of CD11c+ cells (a >19-fold increase compared to the level for mock-infected mice) (Fig. 1A). Thus, infection with vaccinia virus resulted in a significant recruitment of DC to the draining lymph node that was detected as early as day 1 postinfection.

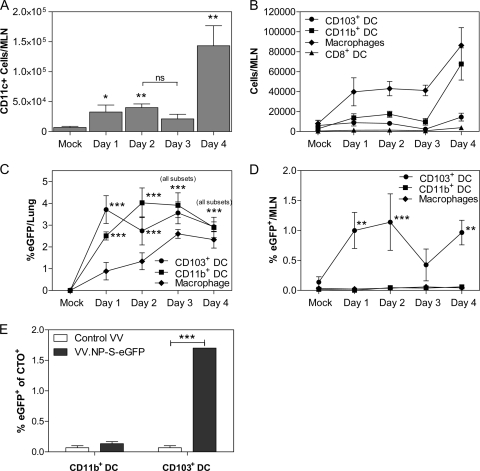

FIG. 1.

Dendritic cells increase in the lung draining MLN following VV infection. C57BL/6 mice were intranasally infected with 107 PFU of VV.NP-S-eGFP. On days 1 to 4 postinfection, MLN were isolated and CD11c+, CD90.2−, CD49b−, and CD19− populations analyzed for expression of CD103, CD11b, CD8, and F4/80. The total number of CD11c+ cells (A) and the number present within each DC subset as well as the number of macrophages (B) were calculated based on the total cells recovered. eGFP expression in the populations was analyzed in both the lung (C) and the MLN (D) and is graphed as a percentage of each APC type expressing eGFP. (E) Mice were infected, and 5 h later, CTO was administered intratracheally. Cells were pregated as CD11c+, CD90.2−, CD49b−, or CD19−, and subsequently CTO+ CD11b+ or CD103+ DC were analyzed for eGFP+ cells on day 2 postinfection. Data in panels A to D reflect the averages from 4 independent experiments. In these experiments, to be considered valid for analysis, the number of eGFP+ events in each population had to be 5-fold greater than that observed in mock-infected mice. Significant eGFP+ events among the different populations in the lung for individual mice ranged from 19 to 205 for day 1, from 17 to 588 for day 2, from 10 to 598 for day 3, and from 14 to 747 for day 4. The variation in cell number was the result of differences in the sizes of the different APC populations. For the MLN, significant eGFP+ events were observed only for CD103+ cells. For individual mice, these ranged from 9 to 29 on day 1, from 14 to 32 on day 2, from 16 to 24 on day 3, and from 13 to 39 on day 4. The data in panel E reflect 3 independent experiments, each utilizing between 23 and 25 pooled MLN for each condition. Significance for panels A to D was determined by 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Bonferroni posttest comparing values for subsets to values for mock infection. For panel E, Student's t test was used to compare levels of eGFP expression between control and day 2 results within each subset. Error bars represent the standard errors of the means (SEM). *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.005; ns, not significant.

We next evaluated the presence of defined DC populations. We used a panel of markers that included CD11c, CD103, CD8α, and CD11b to distinguish individual subsets. Lung airway-derived DC were identified as CD11c+ CD103+ CD11b− (here referred to as CD103+ DC) (35). In addition to this airway-derived population, a CD11c+ CD103− CD11b+ subset (here referred to as CD11b+ DC) has been reported to reside in the lung parenchyma (35). Of note, CD11b+ cells in this analysis also contain LN-resident, conventional DC or monocyte-derived DC. Finally, CD11c+ CD8α+ CD11b− lymph node-resident DC (here referred to as CD8α+ DC) were assessed. In addition to DC, we determined the number of macrophages in the draining lymph node. While these cells appear to play a limited role in the activation of vaccinia virus-specific T cells (28), they have the potential to transport antigen to the MLN. This analysis revealed an early increase in CD11b+ DC as well as macrophages (Fig. 1B). No significant increase in CD8α+ or CD103+ cells was detected, although this was challenging given the small sizes of these populations.

CD103+ DC in the MLN are enriched for eGFP+ cells.

The vaccinia virus construct utilized for these studies allowed us to monitor the presence of viral protein in the various populations via assessment of eGFP. We began by quantifying cells within the lung as an indicator of antigen-bearing cells with the potential to traffic to the MLN. In the lung, both the CD103+ and CD11b+ DC populations contained a significant percentage of cells that were eGFP+ on day 1 p.i. (Fig. 1C). eGFP+ cells were also detected within the macrophage population (Fig. 1C). The percentage of CD11b+ DC that was eGFP+ was increased at day 2, while the percentage of CD103+ DC that was eGFP+ was similar to that at day 1 p.i. Macrophages exhibited a continuous increase in the percentage of cells that were eGFP+ over all 4 days analyzed. As expected, there were few, if any, events that fell within the eGFP+ gate when cells from the mock-infected mice (or mice infected with a recombinant vaccinia virus that did not express eGFP [data not shown]) were analyzed.

eGFP+ CD103+ DC were also found in the MLN (Fig. 1D). Interestingly, the percentage of eGFP+ cells detectable in the CD11b+ DC and macrophage populations was never significantly above the background for mock-infected animals. Analysis of T, B, and NK cells in the MLN showed that there were no detectable eGFP+ cells in these populations (data not shown). Together, these data suggested that airway CD103+ DC are infected or acquire viral antigen in the lung and subsequently traffic to the draining LN, where they have the potential to serve as activators of naive T cells. In contrast, while eGFP+ parenchymal CD11b+ DC were detected in the lung, they were not present above background in the draining LN. One caveat to this result is the presence of a large number of LN-resident DC that bear this marker. Thus, it remained possible that eGFP+ lung-resident parenchymal DC were migrating to the MLN but were difficult to detect as a result of dilution within the LN-resident CD11b+ DC population.

To address this question, we labeled lung DC by intratracheal administration of Cell Tracker Orange (CTO). This approach was chosen to allow concurrent detection of lung-derived cells and eGFP positivity. Mice received virus by i.t. instillation and, 5 h later, received CTO by i.t. delivery. MLN were isolated and the percentages of eGFP+ cells within the CTO+ CD11b+ and CTO+ CD103+ populations determined. Of the analyzed CTO+ cells from the MLN, approximately 41% were CD11c+ DC; the remaining 59% were likely macrophages, as determined by their forward and side scatter profiles (data not shown). Of the total CD103+ DC and CD11b+ DC present in the MLN, approximately 23.0% ± 4.3% and 9.7% ± 1.8%, respectively, were labeled with CTO. The increase in CTO labeling of the CD103+ DC compared to that of the CD11b+ DC was likely due to CD103+ DC proximity to the airway. These studies showed that only a minimal percentage of the CTO+ CD11b+ cells were positive for eGFP (0.13% ± 0.03%, not significantly different than background) (Fig. 1E). In contrast, 1.7% ± 0.0% of CTO+ CD103+ cells were eGFP+, a percentage similar to that seen in the total CD103+ DC population of the MLN (Fig. 1D). These data suggest that while parenchymal CD11b+ DC in the lung showed evidence of infection, these eGFP+ cells did not appear to migrate to the draining LN.

CD103+ lung-resident DC are the most efficient activators of naive CD8+ T cells.

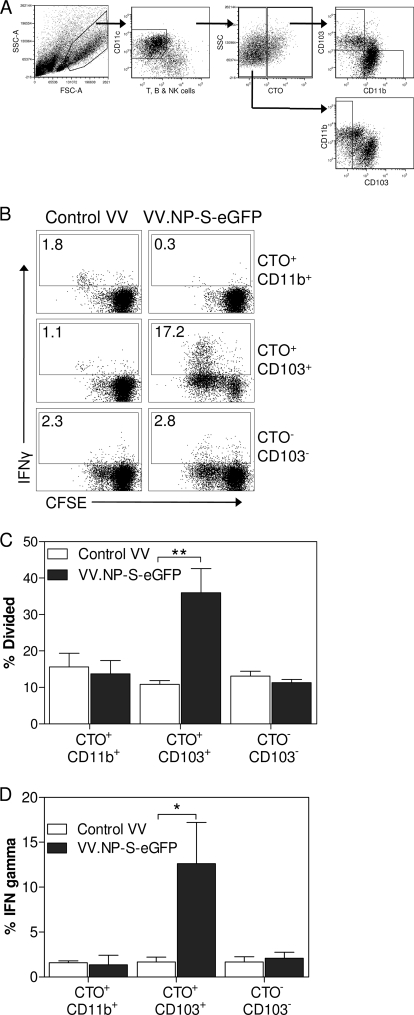

The above-described studies supported a potential role for lung-migrating DC in the activation of naive T cells. In order to determine the ability of these DC to activate naive CD8+ T cells following pulmonary infection with vaccinia virus, we isolated CTO+ CD11b+ and CTO+ CD103+ DC from the MLN of mice infected with VV.NP-S-eGFP. Although there were limited eGFP+ cells found in the CTO+ CD11b+ population, it remained formally possible that these cells contained viral antigen that had been processed for presentation, e.g., as a result of abortive infection or cross-presentation, that would allow them to activate naive T cells. For these studies, mice were infected either with a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing the P protein from SV5 (VV.P), as a control for nonspecific stimulation by DC isolated from a virus-infected environment, or with VV.NP-S-eGFP. DC were isolated into subsets based on their CTO signal and the expression of CD103 or CD11b (CTO+ CD103+ and CTO+ CD11b+) (Fig. 2A) and subsequently cocultured with CFSE-labeled OT-I cells for 3 days. Following the coculture, proliferation and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production in OT-I cells were assessed (Fig. 2B to D). The CD103+ DC from the lung were the only subset that was able to induce significant proliferation in the naive OT-I T cells, with an approximately 4-fold increase over that for OT-I cells incubated with CD103+ DC infected with the control virus (Fig. 2C). The CTO+ CD11b+ DC from the lungs of mice on day 2 showed no ability above those from the control mice to stimulate proliferation in naive OT-I T cells. Additionally, CD103− dendritic cells that were not labeled with CTO failed to induce proliferation in the OT-I T cells above the level seen with mock infection (Fig. 2B to D).

FIG. 2.

Airway-derived CD103+ DC are superior to parenchymal DC for priming naive CD8+ T cells ex vivo. Mice were intranasally infected with 107 PFU of either VV.NP-S-eGFP or the control virus VV.P. Five hours following infection, mice were given 1 mM Cell Tracker Orange i.t. Two days postinfection, mice were sacrificed and MLN harvested. Recovered cells were gated as CD11c+, CD90.2−, CD49b−, and CD19− and were sorted based on their expression of CTO, CD103, and CD11b (A). Sorted cells were then incubated with CFSE-labeled naive OT-I T cells for 3 days at a ratio of 1:5 DC-OT-I cells. OT-I cells were restimulated for 5 h with 10−6 M Ova peptide. Cells were analyzed to determine proliferation and IFN-γ production (representative data are shown in panel B and averaged data in panels C and D). The percent divided was calculated using FlowJo software. MLN from 23 to 25 animals were pooled for each sort. Error bars represent the SEM from 2 individual experiments. Significance was determined using Student's t test to compare results from mock infection and day 2. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01. FSC, forward scatter; SSC, side scatter.

The percentage of the OT-I T cells producing IFN-γ following culture with the sorted DC populations was also assessed to determine the ability of lung-migrating DC to stimulate function in CD8+ T cells. Similarly to the proliferation data, the CTO+ CD103+ DC were the only DC capable of inducing acquisition of IFN-γ production in OT-I naive T cells, with a >10-fold increase in the percentage of cells producing IFN-γ in OT-I cells cultured with the CD103+ DC compared to that of the CD11b+ or CTO− DC (Fig. 2D). Together, the data in Fig. 2 show that among CTO-labeled cells, only CD103+ DC were capable of activating OT-I cells for division and acquisition of effector function. These data suggest a model wherein airway-derived DC are the predominant migrating DC population capable of activating naive CD8+ T cells following a respiratory vaccinia virus infection.

eGFP+ CD103+ DC are enriched for mature cells.

Optimal activation of naive T cells requires accessory signals provided in part by CD28 engagement of CD80/CD86 (29). Thus, we assessed the expression of costimulatory molecules on the CD103+ DC present in the MLN. The data in Fig. 3 show the results from the analysis of CD80 and CD86 expression within the eGFP− and eGFP+ CD103+ populations. Overall, we found that nearly all eGFP+ cells expressed CD80 and CD86 at day 2 and beyond, demonstrating that these cells had undergone maturation (Fig. 3A, B, and D). eGFP− cells also exhibited significant expression of CD80 (Fig. 3B), but a much smaller percentage of cells expressed CD86 (Fig. 3D), suggesting that these cells may have been exposed to a distinct maturation signal in the lung. When the levels of CD80 and CD86 on a per-cell basis were examined, we found no significant difference between eGFP+ and eGFP− cells (Fig. 3C and E). Together, these data show that the presence of detectable eGFP in DC correlated with a program of maturation that included upregulation of both CD80 and CD86.

FIG. 3.

eGFP+ CD103+ DC are highly enriched for mature cells. Mice were intranasally infected with 107 PFU of VV.NP-S-eGFP or PBS as a control. On days 1 to 3 postinfection, MLN from animals were assessed for the maturation of CD103+ DC. eGFP+ and eGFP− cells within the CD11c+, CD103+, CD90.2−, CD49b−, and CD19− populations were analyzed for CD86 and CD80 expression. Representative data are shown in panel A. Isotype staining was performed using pooled cells from infected mice. The percentages of cells that were positive for CD80 (B) or CD86 (D) as well as the intensity of staining for CD80 (C) or CD86 (E) within the positive population are shown. Error bars represent the SEM from 4 or 5 independent experiments, each containing 2 to 5 animals per time point. For each graph, significance was determined using 2-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni posttest. For panels B and D, the percentages of eGFP+ versus eGFP− cells for each time point were compared. For panels C and E, significance determination was performed by comparing the value at each time point to the value for mock infection as well as comparing eGFP+ and eGFP− percentages, as indicated by the brackets. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.005; ns, not significant. For all data points, the following minimum numbers of eGFP+ events were analyzed: on day 1, 18 to 41; on day 2, 239 to 382; on day 3, 64 to 189. In addition, to be considered valid for analysis, the number of eGFP+ events had to be a minimum of 5-fold above that for the mock-infected samples, which ranged from 1 to 5. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

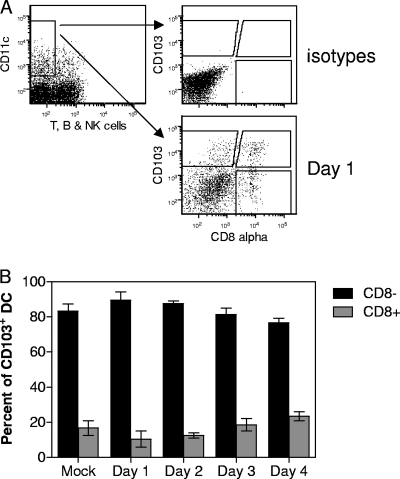

A portion of the CD103+ DC in the MLN expresses CD8α.

While examining the various populations of DC in the MLN, we noted that a portion of CD103+ DC (approximately 20%) costained with anti-CD8α antibody (Fig. 4A). Although the number of CD103+ DC in the MLN increased over time, the percentage of those that coexpressed CD8α+ remained relatively constant (Fig. 4B). This population was not dependent on infection with vaccinia virus, as it was present in the MLN at a similar frequency in mock-infected animals. This subset, while present in the MLN, was notably absent in the lungs (data not shown), in agreement with previous reports analyzing CD103+ cells in the lung (35).

FIG. 4.

A subset of CD103+ cells expressing CD8α+ is present in the MLN. MLN from mock-treated or infected (107 PFU of VV.NP-S-eGFP) animals were isolated on the indicated days. CD11c+, CD90.2−, CD49b−, and CD19− MLN cells were analyzed for the expression of CD8α and CD103. Representative data showing the gating strategy and expression of CD103 and CD8α are given in panel A. Averaged data from 4 independent experiments, each containing MLN cells pooled from 1 to 3 animals per time point, are shown in panel B. Error bars represent the SEM.

CD8α− CD103+ DC are superior stimulators of naive CD8+ T cells compared to CD8α+ CD103+ DC.

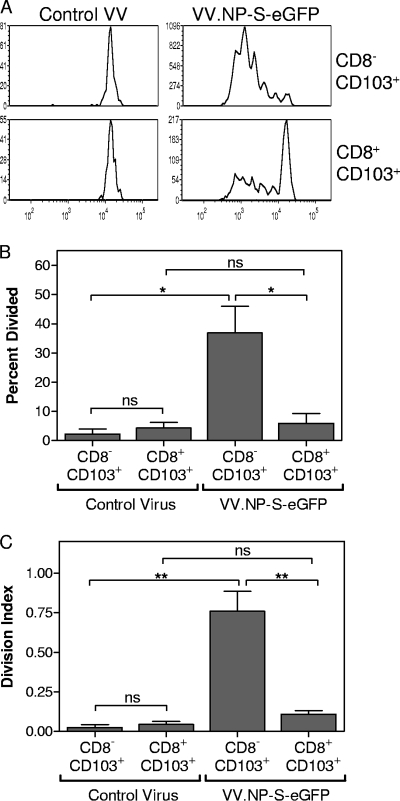

As we have demonstrated in Fig. 5, CD103+ migrating DC are superior to CD11b+ migrating DC with regard to the capacity to activate naive T cells. Given the presence of CD8α+ and CD8α− subsets within this population, we next determined whether there were differences in the abilities of these populations to promote activation of naive T cells. MLN were harvested from mice infected intranasally with VV.NP-S-eGFP or a control vaccinia virus (VV.M), and CD11c+ cells were enriched by column purification. The cells were stained and sorted based on their expression of CD8α and CD103. These sorted DC were then incubated with CFSE-labeled, naive OT-I T cells for 3 days, after which the CFSE signal was assessed to determine proliferation. We found that CD8α− CD103+ DC were the more potent stimulators of naive OT-I T-cell proliferation, as demonstrated by the significant increase in the percentage of OT-I cells that entered division as well as in the calculated division index following incubation with CD8α− CD103+ DC compared to results following incubation with CD8α+ CD103+ DC (Fig. 5B and C). CD8α+ CD103+ DC did not induce significant proliferation in the OT-I T cells above that observed with DC from animals infected with the control virus. In the absence of antigen (i.e., OT-I cells cultured with DC from control vaccinia virus-infected animals), naive T cells did not undergo division and exhibited poor survival during the 3-day culture period (Fig. 5). In the course of these studies, we also isolated lymph node-resident CD8α+ CD103− DC, as this population has been implicated in the activation of virus-specific CD8+ T cells (4). These DC did not induce proliferation of OT-I cells that was above that detected with the corresponding DC population isolated from mice infected with the control virus (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Functional divergence between CD8α+ CD103+ and CD8α− CD103+ DC. Mice were infected intranasally with either VV.NP-S-eGFP or VV.M (107 PFU). On day 2 postinfection, MLN cells were isolated and pooled, and CD11c+ cells were enriched by column purification. The enriched population was sorted into subsets based on CD11c+, CD90.2−, CD49b−, and CD19− staining together with expression of CD8α and CD103. Sorted cells were incubated for 3 days with CFSE-labeled naive OT-I T cells at a ratio of 1:4 DC-OT-I cells. Following culture, OT-I cells were identified by staining with CD90.2 and analyzed for CFSE expression. A representative experiment is shown in panel A, and average data from three independent experiments are shown in panel B. Between 22 and 25 mice were used for each group for each experiment. Error bars represent the SEM. Significance was determined using Student's t test. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ns, not significant.

DISCUSSION

The respiratory tract is a major route through which pathogens enter the body. The ability of DC to detect and respond to infection at this site is a key event in promoting an efficacious adaptive immune response. However, our understanding of how individual DC types contribute to this goal is far from complete. Previous studies have investigated the regulation of these subsets following infection with influenza virus, producing somewhat conflicting data with regard to the relative importance of migratory populations (1, 5, 15, 19). Recent studies in other infectious models, i.e., RSV and Bordetella pertussis, support a role for migratory DC (11, 26).

Respiratory infection with poxvirus poses a significant threat, and our understanding of the role of distinct DC subsets in this response is minimal. Certainly, properties like cytopathicity, permissivity, or the immunoregulatory capabilities of a virus have the potential to impact the contribution of distinct DC populations, making unclear the extent to which observations with one virus can be generalized. The goal of the work presented here was to determine the roles of airway-resident DC subsets versus lymph node-resident DC subsets in the generation of a CD8+ T-cell response following pulmonary poxvirus infection. We focused on four populations of DC: the airway-derived CD103+ DC, the parenchyma-derived CD103− CD11b+ DC, the lymph node-resident CD8α+ DC, and the lymph node CD11b+ DC. These populations were analyzed with regard to the presence of virally expressed eGFP, maturation state, and ability to activate naive T cells.

Our results demonstrated that eGFP+ cells in the draining lymph node were found predominantly among the lung-derived CD103+ DC populations. It was surprising that we found no evidence of the presence of parenchyma-derived eGFP+ DC in the MLN, given that these cells were readily detected in the lung. Further, we found no evidence to support a role for parenchymal DC in T-cell activation. This finding differs from what has been reported for influenza virus and RSV infections, where parenchymal DC were capable of activating CD8+ T cells (1, 23, 26). Interestingly eGFP− CTO+ CD11b+ cells were readily detected in the MLN following infection, suggesting that there was not a general migratory block for parenchymal DC (data not shown). At this time, the mechanism responsible for the absence of eGFP+ CD11b+ DC in the MLN is not known. One possibility is that the CD11b+ DC are more susceptible to the cytopathic effects of vaccinia virus infection and, as a result, undergo apoptosis prior to/during their emigration from the lung. Alternatively, migration of DC into the lymph node is dependent on the upregulation of chemokine receptors, e.g., CCR7 and CCR8 (18, 22, 27). As such, eGFP+ lung parenchymal DC may fail to upregulate these receptors, thereby preventing entry into the lymph node. Finally, emigration of lung DC has been reported to be dependent on sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) (21). The receptors for S1P (S1PR) on DC are known to be regulated in a maturation-dependent fashion (8). Thus, a failure to upregulate S1PR on eGFP+ parenchymal DC could impede egress from the lung. Direct testing of these possibilities awaits further study.

eGFP expression within DC subsets correlated strongly with the ability to induce T-cell activation. While the reason is unknown at this time, we favor the hypothesis that eGFP within DC is likely to identify infected cells. This is due to both the rapidity with which this protein can be denatured/degraded once taken up through the phagocytic pathway (9, 16) and the intensity of signal in the DC. However, given the finding that CD103+ DC are highly competent for cross-presentation (23), the relative contributions of direct presentation versus cross-presentation within the context of vaccinia virus infection is unknown. The very low number of eGFP+ cells within the lymph node makes this technically challenging to assess directly. If indeed eGFP marks infected cells, the finding that cells expressing eGFP were highly enriched for mature DC, as determined by the upregulation of CD80 and CD86, is noteworthy as it is in contrast to what has been reported for in vitro-generated bone marrow-derived DC (BMDC), where infection with vaccinia virus is cytopathic and fails to promote maturation (12, 40). The correlation between eGFP positivity and maturation also contrasts with what has been observed following intravenous administration of vaccinia virus, where generalized upregulation of CD80 and CD86 in DC in the spleen was observed (39, 41). The generalized maturation observed with intravenous infection was presumably the result of inflammatory cytokines or PAMPs present during active infection in this tissue. The different results from these two studies provide evidence that the route of infection has a profound effect on the DC populations that undergo maturation and are thus competent for T-cell activation. One potential mechanism through which VV infection could induce DC maturation is activation of cytoplasmic sensors, such as DAI (36, 38). Activation of DAI results in a robust type I IFN response (36), which is a signal for upregulation of CD80 and CD86 (13, 25). Although Toll-like receptor (TLR) engagement is a commonly utilized maturation signal, VV is reported to inhibit TLR signaling through production of A46R and A52R (6, 20, 34), seemingly making this mechanism less attractive. However, the ability of VV to activate innate immune responses via TLR2 has been reported previously (41), suggesting that inhibition via this pathway is incomplete. Thus, TLR-mediated maturation remains a possibility.

Prior studies have established that CD8α is absent on CD103+ DC in the lungs (30, 35; our unpublished data). However, these cells are readily detected in the lung draining MLN (references 1 and 23 and the studies reported here). In our analyses, CD8α+ CD103+ DC do not express the T-cell markers Thy1.2 and CD3 (data not shown), suggesting that they have not acquired CD8α through trogocytosis, as has been suggested previously (23). Interestingly, the active induction of CD8α expression in vitro on lung-derived DC has been reported previously (30). In this study, a portion of CD8α− lung-derived DC were capable of expressing CD8α following treatment with lipopolysaccharide (LPS). However, it is clear in our data, as well in those from the in vitro study, that upregulation of CD8α is not simply a by-product of maturation. Interestingly, we find that these two subpopulations of CD103+ DC differ in ability to activate CD8+ T cells following infection with VV. Our preliminary studies suggest that the CD8α− CD103+ DC exhibit greater maturation than their CD8α+ counterpart. Thus, this may contribute to their increased capacity to activate cells. Understanding the genesis of these two populations and their role in activation of T cells following infection is an important area for further investigation.

In summary, our data suggest that CD103+ lung-resident DC are the primary DC subset capable of stimulating vaccinia virus-specific CD8+ T-cell responses following respiratory infection. In the draining lymph node, this population had the greatest frequency of viral-antigen-positive cells and had undergone significant maturation. Further, these DC were the most efficient activators of naive T cells in vitro. Importantly, CD103+ DC exhibited heterogeneity in their ability to activate naive T cells, and this was negatively correlated with the expression of CD8α on a subpopulation of these cells, suggesting that this marker may identify populations of cells with distinct functional properties.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jack Bennink for provision of VV.NP-S-eGFP, Jim Wood and Beth Holbrook for help in sorting DC populations, and Beth Hiltbold Schwartz and Griff Parks for helpful discussions regarding the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants P01 AI060642 (to Steven B. Mizel) and R01 HL071985 (to M.A.A.-M.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 July 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ballesteros-Tato, A., B. Leon, F. E. Lund, and T. D. Randall. 2010. Temporal changes in dendritic cell subsets, cross-priming and costimulation via CD70 control CD8(+) T cell responses to influenza. Nat. Immunol. 11:216-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banchereau, J., F. Briere, C. Caux, J. Davoust, S. Lebecque, Y. J. Liu, B. Pulendran, and K. Palucka. 2000. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18:767-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banchereau, J., and R. M. Steinman. 1998. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature 392:245-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belz, G. T., C. M. Smith, D. Eichner, K. Shortman, G. Karupiah, F. R. Carbone, and W. R. Heath. 2004. Cutting edge: conventional CD8 alpha+ dendritic cells are generally involved in priming CTL immunity to viruses. J. Immunol. 172:1996-2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belz, G. T., C. M. Smith, L. Kleinert, P. Reading, A. Brooks, K. Shortman, F. R. Carbone, and W. R. Heath. 2004. Distinct migrating and nonmigrating dendritic cell populations are involved in MHC class I-restricted antigen presentation after lung infection with virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:8670-8675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowie, A., E. Kiss-Toth, J. A. Symons, G. L. Smith, S. K. Dower, and L. A. J. O'Neill. 2000. A46R and A52R from vaccinia virus are antagonists of host IL-1 and toll-like receptor signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:10162-10167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caux, C., B. Vanbervliet, C. Massacrier, M. Azuma, K. Okumura, L. L. Lanier, and J. Banchereau. 1994. B70/B7-2 is identical to CD86 and is the major functional ligand for CD28 expressed on human dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 180:1841-1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Czeloth, N., G. Bernhardt, F. Hofmann, H. Genth, and R. Forster. 2005. Sphingosine-1-phosphate mediates migration of mature dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 175:2960-2967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drecktrah, D., L. A. Knodler, R. Ireland, and O. Steele-Mortimer. 2006. The mechanism of Salmonella entry determines the vacuolar environment and intracellular gene expression. Traffic 7:39-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunlop, L. R., K. A. Oehlberg, J. J. Reid, D. Avci, and A. M. Rosengard. 2003. Variola virus immune evasion proteins. Microbes Infect. 5:1049-1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunne, P. J., B. Moran, R. C. Cummins, and K. H. Mills. 2009. CD11c+CD8alpha+ dendritic cells promote protective immunity to respiratory infection with Bordetella pertussis. J. Immunol. 183:400-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engelmayer, J., M. Larsson, M. Subklewe, A. Chahroudi, W. I. Cox, R. M. Steinman, and N. Bhardwaj. 1999. Vaccinia virus inhibits the maturation of human dendritic cells: a novel mechanism of immune evasion. J. Immunol. 163:6762-6768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallucci, S., M. Lolkema, and P. Matzinger. 1999. Natural adjuvants: endogenous activators of dendritic cells. Nat. Med. 5:1249-1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.GeurtsvanKessel, C. H., and B. N. Lambrecht. 2008. Division of labor between dendritic cell subsets of the lung. Mucosal Immunol. 1:442-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.GeurtsvanKessel, C. H., M. A. Willart, L. S. van Rijt, F. Muskens, M. Kool, C. Baas, K. Thielemans, C. Bennett, B. E. Clausen, H. C. Hoogsteden, A. D. Osterhaus, G. F. Rimmelzwaan, and B. N. Lambrecht. 2008. Clearance of influenza virus from the lung depends on migratory langerin+CD11b- but not plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 205:1621-1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gille, C., B. Spring, L. Tewes, C. F. Poets, and T. Orlikowsky. 2006. A new method to quantify phagocytosis and intracellular degradation using green fluorescent protein-labeled Escherichia coli: comparison of cord blood macrophages and peripheral blood macrophages of healthy adults. Cytometry A 69:152-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gray, P. M., G. D. Parks, and M. A. Alexander-Miller. 2001. A novel CD8-independent high-avidity cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response directed against an epitope in the phosphoprotein of the paramyxovirus simian virus 5. J. Virol. 75:10065-10072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hammad, H., and B. N. Lambrecht. 2007. Lung dendritic cell migration. Adv. Immunol. 93:265-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hao, X., T. S. Kim, and T. J. Braciale. 2008. Differential response of respiratory dendritic cell subsets to influenza virus infection. J. Virol. 82:4908-4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harte, M. T., I. R. Haga, G. Maloney, P. Gray, P. C. Reading, N. W. Bartlett, G. L. Smith, A. Bowie, and L. A. J. O'Neill. 2003. The poxvirus protein A52R targets Toll-like receptor signaling complexes to suppress host defense. J. Exp. Med. 197:343-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Idzko, M., H. Hammad, M. van Nimwegen, M. Kool, T. Muller, T. Soullie, M. A. Willart, D. Hijdra, H. C. Hoogsteden, and B. N. Lambrecht. 2006. Local application of FTY720 to the lung abrogates experimental asthma by altering dendritic cell function. J. Clin. Invest. 116:2935-2944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jakubzick, C., F. Tacke, J. Llodra, N. Van Rooijen, and G. J. Randolph. 2006. Modulation of dendritic cell trafficking to and from the airways. J. Immunol. 176:3578-3584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim, T. S., and T. J. Braciale. 2009. Respiratory dendritic cell subsets differ in their capacity to support the induction of virus-specific cytotoxic CD8+ T cell responses. PLoS One 4:e4204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin, M. L., Y. Zhan, A. I. Proietto, S. Prato, L. Wu, W. R. Heath, J. A. Villadangos, and A. M. Lew. 2008. Selective suicide of cross-presenting CD8+ dendritic cells by cytochrome c injection shows functional heterogeneity within this subset. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:3029-3034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luft, T., K. C. Pang, E. Thomas, P. Hertzog, D. N. Hart, J. Trapani, and J. Cebon. 1998. Type I IFNs enhance the terminal differentiation of dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 161:1947-1953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lukens, M. V., D. Kruijsen, F. E. J. Coenjaerts, J. L. L. Kimpen, and G. M. van Bleek. 2009. Respiratory syncytial virus-induced activation and migration of respiratory dendritic cells and subsequent antigen presentation in the lung-draining lymph node. J. Virol. 83:7235-7243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin-Fontecha, A., S. Sebastiani, U. E. Hopken, M. Uguccioni, M. Lipp, A. Lanzavecchia, and F. Sallusto. 2003. Regulation of dendritic cell migration to the draining lymph node: impact on T lymphocyte traffic and priming. J. Exp. Med. 198:615-621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norbury, C. C., D. Malide, J. S. Gibbs, J. R. Bennink, and J. W. Yewdell. 2002. Visualizing priming of virus-specific CD8+ T cells by infected dendritic cells in vivo. Nat. Immunol. 3:265-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nurieva, R. I., X. Liu, and C. Dong. 2009. Yin-yang of costimulation: crucial controls of immune tolerance and function. Immunol. Rev. 229:88-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pascual, D. W., X. Wang, I. Kochetkova, G. Callis, and C. Riccardi. 2008. The absence of lymphoid CD8+ dendritic cell maturation in L-selectin-/- respiratory compartment attenuates antiviral immunity. J. Immunol. 181:1345-1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schnorrer, P., G. M. Behrens, N. S. Wilson, J. L. Pooley, C. M. Smith, D. El Sukkari, G. Davey, F. Kupresanin, M. Li, E. Maraskovsky, G. T. Belz, F. R. Carbone, K. Shortman, W. R. Heath, and J. A. Villadangos. 2006. The dominant role of CD8+ dendritic cells in cross-presentation is not dictated by antigen capture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:10729-10734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Segura, E., and J. A. Villadangos. 2009. Antigen presentation by dendritic cells in vivo. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 21:105-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shen, X. F., S. B. J. Wong, C. B. Buck, J. W. Zhang, and R. F. Siliciano. 2002. Direct priming and cross-priming contribute differentially to the induction of CD8+ CTL following exposure to vaccinia virus via different routes. J. Immunol. 169:4222-4229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stack, J., I. R. Haga, M. Schroder, N. W. Bartlett, G. Maloney, P. C. Reading, K. A. Fitzgerald, G. L. Smith, and A. G. Bowie. 2005. Vaccinia virus protein Toll-like-interleukin-1 A46R targets multiple receptor adaptors and contributes to virulence. J. Exp. Med. 201:1007-1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sung, S. S., S. M. Fu, C. E. Rose, Jr., F. Gaskin, S. T. Ju, and S. R. Beaty. 2006. A major lung CD103 (alphaE)-beta7 integrin-positive epithelial dendritic cell population expressing Langerin and tight junction proteins. J. Immunol. 176:2161-2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takaoka, A., Z. Wang, M. K. Choi, H. Yanai, H. Negishi, T. Ban, Y. Lu, M. Miyagishi, T. Kodama, K. Honda, Y. Ohba, and T. Taniguchi. 2007. DAI (DLM-1/ZBP1) is a cytosolic DNA sensor and an activator of innate immune response. Nature 448:501-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsomides, T. J., A. Aldovini, R. P. Johnson, B. D. Walker, R. A. Young, and H. N. Eisen. 1994. Naturally processed viral peptides recognized by cytotoxic T lymphocytes on cells chronically infected by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Exp. Med. 180:1283-1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vilaysane, A., and D. A. Muruve. 2009. The innate immune response to DNA. Semin. Immunol. 21:208-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yammani, R. D., S. Pejawar-Gaddy, T. C. Gurley, E. T. Weimer, E. M. Hiltbold, and M. A. Alexander-Miller. 2008. Regulation of maturation and activating potential in CD8+ versus CD8− dendritic cells following in vivo infection with vaccinia virus. Virology 378:142-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yates, N. L., R. D. Yammani, and M. A. Alexander-Miller. 2008. Dose-dependent lymphocyte apoptosis following respiratory infection with vaccinia virus. Virus Res. 137:198-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhu, J., J. Martinez, X. Huang, and Y. Yang. 2007. Innate immunity against vaccinia virus is mediated by TLR2 and requires TLR-independent production of IFN-beta. Blood 109:619-625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]