Abstract

In the process of translation of eukaryotic mRNAs, the 5′ cap and the 3′ poly(A) tail interact synergistically to stimulate protein synthesis. Unlike its cellular counterparts, the small mRNA (SmRNA) of Andes hantavirus (ANDV), a member of the Bunyaviridae, lacks a 3′ poly(A) tail. Here we report that the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) of the ANDV SmRNA functionally replaces a poly(A) tail and synergistically stimulates cap-dependent translation initiation from the viral mRNA. Stimulation of translation by the 3′UTR of the ANDV SmRNA was found to be independent of viral proteins and of host poly(A)-binding protein.

Eukaryotic mRNAs present a 5′ cap structure, and most also feature a 3′ poly(A) tail (11, 28, 42). Both elements play key roles in several important cellular processes, including translation initiation (11, 12, 16, 42, 50), in which they act synergistically to stimulate protein synthesis (14, 26, 27).

Translation initiation is a stepwise process by which the 40S ribosomal subunit is recruited to the mRNA and then scans in a 5′-to-3′ direction until the first initiation codon in a favorable context is encountered, at which point the 80S ribosome is assembled (18, 44). Critical to the process is eIF4F, a three-subunit complex composed of eIF4E, the cap-binding protein, eIF4A, a bidirectional helicase, and eIF4G, which serves as a scaffold for the coordinated assembly of translation initiation complexes (18, 44). The 3′ poly(A) tail of most transcripts is coated with multiple copies of poly(A)-binding protein (PABP), a ubiquitous 70-kDa protein that interacts with eIF4G, leading to mRNA circularization by bringing its 5′ and 3′ termini into close contact [cap-eIF4E/eIF4G/PABP-poly(A)] (20, 23). It is in this context that the poly(A) tail interacts with the 5′ cap and stimulates translation initiation (14, 26, 27).

The Bunyaviridae family of viruses exhibits a tripartite genome consisting of three different negative-polarity, single-stranded RNA segments designated large (L), medium (M), and small (S), that are packed into helical nucleocapsids (21, 37). Transcripts from the Bunyaviridae genome possess a 5′ cap structure; however, they lack a 3′ poly(A) tail (29, 34). In a recent report, the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) of the Bunyamwera virus (BUNV) small mRNA (SmRNA) was shown to act in a fashion analogous to that of a poly(A) tail, stimulating translation of viral mRNA (8). The mechanism of stimulation remains unknown, but it was shown to be PABP independent (8).

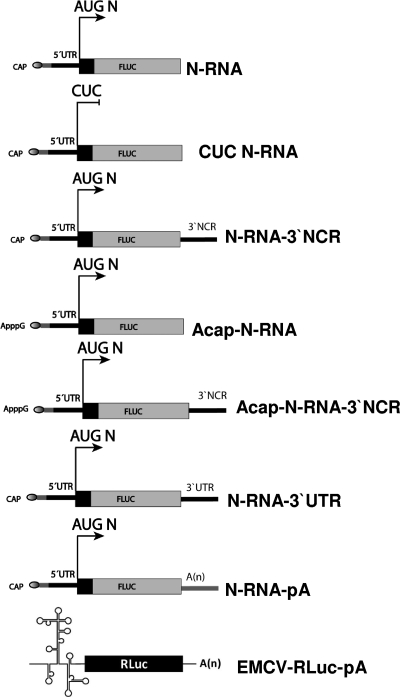

In this study, we undertook an analysis of the SmRNA of Andes virus (ANDV), a rodent-borne member of the Hantavirus genus of the Bunyaviridae, the major etiological agent of hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome (HCPS) in South America (36). Studies were conducted using mRNAs designed to mimic the ANDV SmRNA (Fig. 1), as previously described (3, 8, 49). Since Bunyaviridae mRNAs acquire their 5′ cap though a cap-snatching mechanism (7, 35), a process which adds additional nucleotides to the 5′ end of the viral mRNA, the RNAs used in this study were designed to contain 21 randomly selected nucleotides (5′-GGGAGACCCAAGCTGGCTAGC-3′; the gray regions in Fig. 1) between their 5′ cap and the first nucleotide of the ANDV sequence (GenBank accession no. NC_003466) (25), thereby mimicking the viral mRNA. In the N protein RNA (N-RNA), the SmRNA 5′UTR and the first 76 nucleotides (nt) downstream of the N protein initiation codon were inserted upstream of a firefly luciferase (FLuc) reporter gene (Fig. 1). The FLuc reporter was positioned in frame with the N protein initiation codon (AUGN) (Fig. 1). The authenticity of plasmids used in this study was confirmed by sequencing (Macrogen Corp., Rockville, MD).

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the recombinant monocistronic RNAs used in this study. Recombinant monocistronic RNAs designed to mimic the ANDV SmRNA contain 21 additional nucleotides (gray region) between the 5′ cap structure (oval at the 5′ end of the RNA) and the first nucleotide of the ANDV SmRNA sequence (black line). RNAs were capped with a functional 5′ m7GpppG cap structure or with a nonfunctional ApppG cap analog (Acap) (6). Additionally, the firefly luciferase (FLuc) reporter gene was fused to the N coding region in frame with the N initiation codon (AUGN; arrows). In CUC N-RNA, the AUGN initiation codon was mutated to CUC. The poly(A) tail is designated pA or (A)n, the 3′NCR corresponds to the full-length 3′ noncoding region of the ANDV cRNA, and the 3′UTR represents the ANDV cRNA 3′NCR with a 50-nt truncation. The control EMCV-RLuc-pA RNA is also shown.

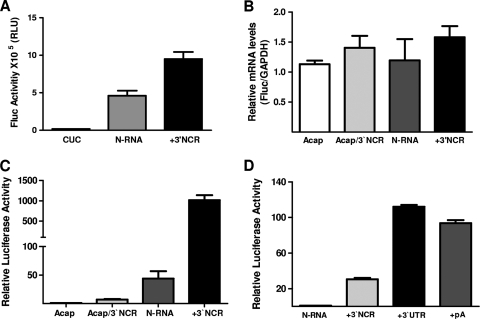

In Bunyaviridae, the process of RNA transcription generates two distinct RNA products, namely, the viral mRNA and the positive-sense antigenome (cRNA) (19, 21, 37). The first is recognized by the translational machinery and encodes the viral proteins, while the second acts as an intermediate for the synthesis of further copies of the genomic strands. The genome and antigenome replication products are exact complementary copies of each other. In contrast, the mRNAs are shorter than their respective genomic templates due to 3′-end truncation. In BUNV, the SmRNA is truncated by about 100 nt (8), while the extent of 3′ truncation of the ANDV SmRNA is currently unknown. For this reason and purely as a first approach, we studied the effect of the 3′ noncoding region (3′NCR) of the ScRNA on translation from the virus-like mRNAs. For this we designed construct N-RNA-3′NCR (Fig. 1), which harbors the full-length 3′NCR (542 nt) of ANDV ScRNA, positioned immediately 3′ of the FLuc gene (25). In the first series of experiments, we asked whether the ScRNA 3′NCR could enhance cap-dependent translation from the virus-like RNAs. The in vitro-generated transcripts capped N-RNA and capped N-RNA-3′NCR (0.06 pmol each) were translated in Flexi-rabbit reticulocyte lysate (RRL; 50% [vol/vol]; Promega) as previously described (45). Luciferase activity was measured using the dual-luciferase reporter (DLR) assay system (Promega) on a Sirius single-tube luminometer (Lumat 9507; Berthold Detection Systems GmbH, Germany) (5, 48). N-RNA-3′NCR exhibited significantly increased FLuc activity compared to its counterpart lacking the 3′NCR sequences (N-RNA) (Fig. 2 A). As an additional control, the N initiation codon, AUGN, was mutated to a CUC codon, resulting in no observable FLuc activity and confirming the absence of nonspecific FLuc expression (Fig. 2A). These data suggest that the 3′NCR of the ScRNA stimulates the in vitro translation of virus-like mRNAs.

FIG. 2.

The 3′UTR of the ANDV cRNA synergistically stimulates cap-dependent translation initiation from virus-like mRNAs. (A) In vitro-transcribed N-RNA, CUC N-RNA (CUC), and N-RNA-3′NCR (+3′NCR) RNAs depicted in Fig. 1 were translated in RRL (50% [vol/vol]), and luciferase activity was measured as described in the text. FLuc activity is expressed as raw data. Values are the means ± standard deviations (SD) of results from three independent experiments, each conducted in triplicate. (B and C) In vitro-transcribed Acap-N-RNA (Acap), Acap-N-RNA-3′NCR (Acap/3′NCR), N-RNA, and N-RNA-3′NCR (+3′NCR) RNAs depicted in Fig. 1 were transfected into HeLa cells. (B) Total RNA was extracted from transfected cells and used in an RT-qPCR assay for FLuc and GAPDH as previously described (41). The relative mRNA content is expressed as FLuc/GAPDH. (C) Protein extracts from transfected HeLa cells were used to determine FLuc activity. FLuc activity for the Acap-N-RNA was arbitrarily set to 1 (±SD). Values are the means ± SD of results from three independent experiments, each conducted in triplicate. (D) The in vitro-transcribed N-RNA, N-RNA-3′NCR (+3′NCR), N-RNA-3′UTR (+3′UTR), and N-RNA-pA (+pA) RNAs depicted in Fig. 1 were transfected in HeLa cells together with mRNA in which the β-globin 5′UTR is followed by the Renilla luciferase (RLuc) reporter gene. Protein extract from transfected HeLa cells was used to determine FLuc and RLuc activities. FLuc values were normalized to the RLuc activities, and the relative luciferase activity (RLU) for the cap-N-RNA was arbitrarily set to 1 (±SD). Values are the means ± SD of results from three independent experiments, each conducted in triplicate.

Next, we transfected HeLa cells with in vitro-synthesized N-RNA and N-RNA-3′NCR RNAs (0.4 pmol each) (Fig. 1), harboring either a functional 5′ m7GpppG (cap) or an ApppG cap analog (Acap) (6), using the Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen). Acap is not recognized by eIF4E and thus does not support cap-dependent translation initiation (6, 18, 44). Upon transfection (5 h), total RNA and total proteins were extracted (41) and used to quantify recombinant RNA by a reverse transcription quantitative PCR approach (RT-qPCR) and FLuc activity, respectively. The virus-like RNAs were amplified in parallel with the GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) housekeeping gene, as previously described (41). As shown in Fig. 2B, the levels of virus-like RNA did not significantly vary among the different assays, suggesting that the quantities and levels of stability of transfected RNAs were similar. Relative FLuc activity was determined, and that from Acap-N-RNA was arbitrarily set to 1 (Fig. 2C). The presence of 3′NCR sequences resulted in only a poor (7-fold) increase in translation from the Acap-N-RNA, suggesting that the ANDV ScRNA 3′NCR is incapable, by itself, of driving efficient translation initiation from the virus-like mRNAs (Fig. 2C). In the presence of a functional 5′ cap structure but in the absence of 3′NCR sequences (N-RNA), translation increased more than 40-fold compared to that of Acap-N-RNA, suggesting a cap dependency for translation. Strikingly, however, when a functional 5′ cap structure was combined with the 3′NCR, translation was increased by more than 3 logs, suggesting a strong synergic interaction between the 5′ cap and the 3′NCR (Fig. 2C). Together, these observations suggest that translation initiation from the virus-like mRNAs utilized in our study is cap dependent and that the presence of the 3′NCR of ANDV ScRNA stimulates protein synthesis.

A clear weakness in the data presented above is the use of 3′NCR sequences from ANDV ScRNA, which do not represent the 3′UTR of the viral SmRNA. However, in the knowledge that the 3′ and 5′ termini of hantavirus genomic S-segment RNA (gRNA) share complementarity and undergo base pairing to form a “panhandle” structure in the presence of viral proteins (4, 22, 32), it was supposed that the ANDV ScRNA may also form an equivalent intramolecular structure. We also reasoned that due to its 3′ truncation, the viral mRNA is unlikely to be capable of efficient 3′-5′ base pairing. Thus, to generate a 3′UTR more likely to be representative of the true viral 3′UTR, the cRNA 3′NCR sequence was systematically truncated (in silico) until the formation of the theoretical 3′-5′ base-paired RNA structure, predicted in mFold, was prevented (24, 51). Using this approach, we found that a 50-nt truncation in the ScRNA 3′NCR impeded efficient 3′-5′ base pairing. This prediction is in accordance with previous reports for other hantaviruses; a 42-nt truncation in the SgRNA 3′NCR of the Sin Nombre virus, for instance, hinders panhandle formation (30). Although the degree of ANDV SmRNA truncation is unknown and we cannot ascertain from currently published information whether a 50-nt truncation truly corresponds to the SmRNA 3′UTR, we took the view that the 3′NCR featuring the 50-nt truncation (herein named 3′UTR) better represents the viral SmRNA 3′UTR than the full ScRNA 3′NCR. Our next evaluation therefore centered on the effect of the 3′UTR on the translation initiation of the virus-like mRNAs (Fig. 1), in which we compared the translational activities of in vitro-generated capped N-RNAs either lacking 3′ sequences or featuring the full-length ANDV ScRNA 3′NCR (+3′NCR), the 3′NCR with the 50-nt truncation (+3′UTR), or a poly(A) tail (+pA). The poly(A) tail was added by means of a commercial poly(A) tailing kit (Applied Biosystems/Ambion). In vitro-transcribed RNAs were transfected into HeLa cells (0.4 pmol), and total RNA and proteins were recovered as described previously. Once more, the levels of virus-like RNA did not significantly vary among the different transfection assays (data not shown). Extracted protein was used to determine luciferase activities, and data are expressed as relative FLuc activities, where the activity of the cap-N-RNA was arbitrarily set to 1. In a pattern reminiscent of that seen in Fig. 2A and C, the presence of the ScRNA 3′NCR stimulated translation (30-fold) (Fig. 2D), while the presence of a poly(A) tail resulted in a 70- to 90-fold stimulation. These observations suggest that optimal translation from these virus-like mRNAs requires 5′-3′ interactions. To our surprise, mRNA featuring the 3′UTR sequence was translated at least as actively as that featuring the 3′ poly(A) tail [compare N-RNA-poly(A) with N-RNA-3′UTR in Fig. 2D]. These observations suggest that, much like the 3′UTR of BUNV SmRNA (8), the 3′UTR of ANDV SmRNA is capable of functionally replacing a eukaryotic poly(A) tail (Fig. 2D). Our data also suggest a functional difference between the 3′NCR from the ANDV ScRNA and the 3′UTR with respect to their abilities to stimulate translation from an RNA that mimics the SmRNA (compare the N-RNA-3′NCR with the N-RNA-3′UTR in Fig. 2D).

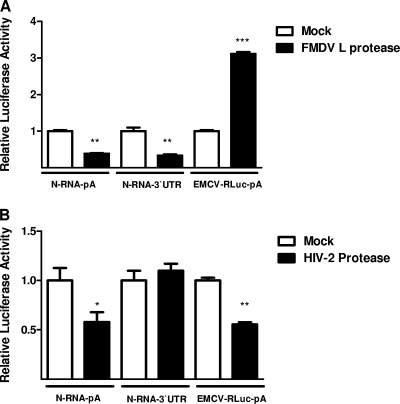

Blakqori et al. (8) showed that the 3′UTR of BUNV SmRNA stimulates the efficient synthesis of viral proteins independently of PABP or the presence of a poly(A) tail (8). So far we have established that a 3′UTR that mimics the ANDV SmRNA can functionally replace the poly(A) tail (Fig. 2D), which predicts that PABP is also not involved in ANDV SmRNA translation. In contrast, PABP is implicated in directly mediating mRNA 5′cap-3′UTR interactions in Dengue virus (DENV), a member of the Flaviviridae, whose mRNA, like that of the Bunyaviridae, is capped yet lacks a poly(A) tail (38). Based on this evidence, the possibility that PABP participates in the translation of ANDV SmRNA cannot be excluded. Thus, we set out to evaluate the role of PABP, if any, in the translation of the virus-like mRNAs described herein. In this set of experiments, we took advantage of the human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) and the foot and mouth disease virus (FMDV) L proteases. The cap-poly(A) tail interaction synergistically stimulates protein synthesis (14, 27) in a process which is mediated by eIF4G and PABP, as outlined above (20, 23). There are two known isoforms of eIF4G in mammalian cells, eIF4GI and eIF4GII (39). Both possess similar biochemical activities and are functionally interchangeable (39). The FMDV L protease cleaves both eIF4GI and eIF4GII (13, 15, 46), inactivating the eIF4F complex in terms of its ability to recognize capped mRNAs, which results in a reduction of cap-dependent translation initiation (15, 39). Interestingly, the carboxy-terminal fragment of eIF4G generated by FMDV L protease cleavage efficiently supports and indeed stimulates cap-independent translation initiation (9, 33). HIV-2 protease, on the other hand, cleaves eIF4GI and PABP but not eIF4GII (1, 2, 40, 43). As a control in this series of experiments, we used an uncapped RNA harboring the encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) internal ribosome entry site (IRES), positioned upstream of the Renilla luciferase (RLuc) reporter (Fig. 1). The rationale for choosing this control RNA relies on the established ability of the EMCV IRES to drive cap-independent translation initiation, which is also stimulated by the presence of a poly(A) tail (6, 17, 27, 47). Three mRNAs, cap-N-RNA-poly(A), cap-N-RNA-3′UTR, and EMCV IRES-RLuc-poly(A) (Fig. 3 A), were generated in vitro and transfected into HeLa cells (0.4 pmol of RNA) transiently expressing the FMDV L or HIV-2 protease. Cells were transfected with 200 ng of RNA encoding each protease 7 h prior to RNA transfections. Total proteins were recovered and reporter gene activity determined as described above. In agreement with extensive evidence (9, 10, 26, 33, 40), translation from the EMCV IRES-RLuc-poly(A) mRNA was stimulated by FMDV L protease activity, demonstrating the efficacy of the experimental system (Fig. 3A). Translation from both the cap-N-RNA-poly(A) and the cap-N-RNA-3′UTR RNAs was significantly reduced, as determined by a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett's post-ANOVA test, in the presence of the FMDV L protease (Fig. 3A), an observation consistent with the notions that translation from the ANDV-like mRNAs is cap dependent and that, in the absence of the viral N protein, the process requires intact eIF4G (31). In the presence of the HIV-2 protease (Fig. 3B), translation from cap-N-RNA-poly(A) and, perhaps surprisingly, the EMCV IRES-RLuc-poly(A) RNA was significantly reduced, again determined by a one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post-ANOVA test. The simplest way of interpreting these results is to assume that the drop in expression from EMCV IRES-RLuc-poly(A) RNA reflects PABP proteolysis by the HIV-2 protease (Fig. 3B), an activity reported previously (40). In summary, translation from both the cap-N-RNA-poly(A) and the EMCV IRES-RLuc-poly(A) RNAs was found to be PABP and poly(A) tail dependent. In contrast, translation of cap-N-RNA-3′UTR RNA was not influenced by HIV-2 protease, suggesting that translation from this mRNA is poly(A) independent and, furthermore, very probably PABP independent.

FIG. 3.

Stimulation of translation by the 3′UTR is PABP independent. (A) HeLa cells expressing the FMDV L protease were transfected with the N-RNA-pA, N-RNA-3′UTR, and EMCV-RLuc-pA RNAs depicted in Fig. 1. (B) HeLa cells expressing the HIV-2 protease were transfected with the N-RNA-pA, N-RNA-3′UTR, and EMCV-RLuc-pA RNAs depicted in Fig. 1. (A and B) Mock cells correspond to cells that do not express the viral protease yet were also transfected with the different RNAs. FLuc activity of the mock transfections was arbitrarily set to 1 (±SD). Values are the means ± SD of results from three independent experiments, each conducted in triplicate.

Taken together, our data suggest that the 3′UTR of ANDV SmRNA exerts functions typically ascribed to the 3′ poly(A) tail, akin to those observed for the 3′UTR of BUNV SmRNA, namely, the synergistic stimulation of cap-dependent translation initiation from the viral mRNA. In addition, it seems likely that the 5′-3′ interaction in ANDV SmRNA is mediated by an as-yet-unidentified host protein(s), since (i) the 5′ and 3′ ends of our recombinant mRNA cannot base pair to form a panhandle structure, (ii) viral proteins are not required for the 3′UTR-mediated stimulation of cap-dependent translation (Fig. 2D), and (iii) the 3′UTR-mediated stimulation of protein synthesis is independent of host PABP (Fig. 3B).

(This research was conducted by Jorge Vera-Otarola in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Ph.D. thesis for the Programa de Doctorado en Microbiología, Facultad de Química y Biología, Universidad de Santiago de Chile, 2010.)

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Rau (Oxford, United Kingdom) for critical reading and editing of the manuscript. We are grateful to Stephen C. St. Jeor (Department of Microbiology, University of Nevada) for kindly providing the plasmid containing the full-length ANDV SmRNA segment. We thank Nahum Sonenberg (Department of Biochemistry, McGill University, Canada) and G. Belsham (Institute for Animal Health, Pirbright, United Kingdom) for providing some of the plasmids used in this study.

This study was supported by Proyecto Núcleo Milenio (P-07-088-F), FONDECYT no. 1100756, and PHS grant 2U01AI045452-11 to M.L.-L. and a travel grant from MECESUP-USACH to J.V.-O. J.V.-O. was supported by a MECESUP-USACH doctoral fellowship. E.P.R. was supported by grants from the Fondation pour la Recherche Medicale (FRM) and the French Ministry (MENRT).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 July 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alvarez, E., A. Castello, L. Menendez-Arias, and L. Carrasco. 2006. HIV protease cleaves poly(A)-binding protein. Biochem. J. 396:219-226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez, E., L. Menendez-Arias, and L. Carrasco. 2003. The eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4GI is cleaved by different retroviral proteases. J. Virol. 77:12392-12400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barr, J. N. 2007. Bunyavirus mRNA synthesis is coupled to translation to prevent premature transcription termination. RNA 13:731-736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barr, J. N., and G. W. Wertz. 2004. Bunyamwera bunyavirus RNA synthesis requires cooperation of 3′- and 5′-terminal sequences. J. Virol. 78:1129-1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barria, M. I., A. Gonzalez, J. Vera-Otarola, U. Leon, V. Vollrath, D. Marsac, O. Monasterio, T. Perez-Acle, A. Soza, and M. Lopez-Lastra. 2009. Analysis of natural variants of the hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site reveals that primary sequence plays a key role in cap-independent translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:957-971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergamini, G., T. Preiss, and M. W. Hentze. 2000. Picornavirus IRESes and the poly(A) tail jointly promote cap-independent translation in a mammalian cell-free system. RNA 6:1781-1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bishop, D. H., M. E. Gay, and Y. Matsuoko. 1983. Nonviral heterogeneous sequences are present at the 5′ ends of one species of snowshoe hare bunyavirus S complementary RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 11:6409-6418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blakqori, G., I. van Knippenberg, and R. M. Elliott. 2009. Bunyamwera orthobunyavirus S-segment untranslated regions mediate poly(A) tail-independent translation. J. Virol. 83:3637-3646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borman, A. M., R. Kirchweger, E. Ziegler, R. E. Rhoads, T. Skern, and K. M. Kean. 1997. elF4G and its proteolytic cleavage products: effect on initiation of protein synthesis from capped, uncapped, and IRES-containing mRNAs. RNA 3:186-196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castello, A., E. Alvarez, and L. Carrasco. 2006. Differential cleavage of eIF4GI and eIF4GII in mammalian cells. Effects on translation. J. Biol. Chem. 281:33206-33216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cowling, V. H. 2010. Regulation of mRNA cap methylation. Biochem. J. 425:295-302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dreyfus, M., and P. Regnier. 2002. The poly(A) tail of mRNAs: bodyguard in eukaryotes, scavenger in bacteria. Cell 111:611-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foeger, N., E. Kuehnel, R. Cencic, and T. Skern. 2005. The binding of foot-and-mouth disease virus leader proteinase to eIF4GI involves conserved ionic interactions. FEBS J. 272:2602-2611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gallie, D. R. 1991. The cap and poly(A) tail function synergistically to regulate mRNA translational efficiency. Genes Dev. 5:2108-2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gradi, A., N. Foeger, R. Strong, Y. V. Svitkin, N. Sonenberg, T. Skern, and G. J. Belsham. 2004. Cleavage of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4GII within foot-and-mouth disease virus-infected cells: identification of the l-protease cleavage site in vitro. J. Virol. 78:3271-3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu, M., and C. D. Lima. 2005. Processing the message: structural insights into capping and decapping mRNA. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 15:99-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hruby, D. E., and W. K. Roberts. 1977. Encephalomyocarditis virus RNA. II. Polyadenylic acid requirement for efficient translation. J. Virol. 23:338-344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson, R. J., C. U. Hellen, and T. V. Pestova. 2010. The mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation and principles of its regulation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11:113-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jonsson, C. B., and C. S. Schmaljohn. 2001. Replication of hantaviruses. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 256:15-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kahvejian, A., G. Roy, and N. Sonenberg. 2001. The mRNA closed-loop model: the function of PABP and PABP-interacting proteins in mRNA translation. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 66:293-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khaiboullina, S. F., S. P. Morzunov, and S. C. St. Jeor. 2005. Hantaviruses: molecular biology, evolution and pathogenesis. Curr. Mol. Med. 5:773-790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohl, A., E. F. Dunn, A. C. Lowen, and R. M. Elliott. 2004. Complementarity, sequence and structural elements within the 3′ and 5′ non-coding regions of the Bunyamwera orthobunyavirus S segment determine promoter strength. J. Gen. Virol. 85:3269-3278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mangus, D. A., M. C. Evans, and A. Jacobson. 2003. Poly(A)-binding proteins: multifunctional scaffolds for the post-transcriptional control of gene expression. Genome Biol. 4:223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathews, D. H., D. H. Turner, and M. Zuker. 2007. RNA secondary structure prediction. Curr. Protoc. Nucleic Acid Chem. 28:11.2.1-11.2.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meissner, J. D., J. E. Rowe, M. K. Borucki, and S. C. St. Jeor. 2002. Complete nucleotide sequence of a Chilean hantavirus. Virus Res. 89:131-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michel, Y. M., A. M. Borman, S. Paulous, and K. M. Kean. 2001. Eukaryotic initiation factor 4G-poly(A) binding protein interaction is required for poly(A) tail-mediated stimulation of picornavirus internal ribosome entry segment-driven translation but not for X-mediated stimulation of hepatitis C virus translation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:4097-4109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michel, Y. M., D. Poncet, M. Piron, K. M. Kean, and A. M. Borman. 2000. Cap-poly(A) synergy in mammalian cell-free extracts. Investigation of the requirements for poly(A)-mediated stimulation of translation initiation. J. Biol. Chem. 275:32268-32276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Millevoi, S., and S. Vagner. 2010. Molecular mechanisms of eukaryotic pre-mRNA 3′ end processing regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 38:2757-2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mir, M. A., W. A. Duran, B. L. Hjelle, C. Ye, and A. T. Panganiban. 2008. Storage of cellular 5′ mRNA caps in P bodies for viral cap-snatching. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:19294-19299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mir, M. A., and A. T. Panganiban. 2006. The bunyavirus nucleocapsid protein is an RNA chaperone: possible roles in viral RNA panhandle formation and genome replication. RNA 12:272-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mir, M. A., and A. T. Panganiban. 2008. A protein that replaces the entire cellular eIF4F complex. EMBO J. 27:3129-3139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mir, M. A., and A. T. Panganiban. 2004. Trimeric hantavirus nucleocapsid protein binds specifically to the viral RNA panhandle. J. Virol. 78:8281-8288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohlmann, T., M. Rau, S. J. Morley, and V. M. Pain. 1995. Proteolytic cleavage of initiation factor eIF-4 gamma in the reticulocyte lysate inhibits translation of capped mRNAs but enhances that of uncapped mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:334-340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patterson, J. L., B. Holloway, and D. Kolakofsky. 1984. La Crosse virions contain a primer-stimulated RNA polymerase and a methylated cap-dependent endonuclease. J. Virol. 52:215-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patterson, J. L., and D. Kolakofsky. 1984. Characterization of La Crosse virus small-genome transcripts. J. Virol. 49:680-685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pini, N. 2004. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome in Latin America. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 17:427-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Plyusnin, A., O. Vapalahti, and A. Vaheri. 1996. Hantaviruses: genome structure, expression and evolution. J. Gen. Virol. 77:2677-2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Polacek, C., P. Friebe, and E. Harris. 2009. Poly(A)-binding protein binds to the non-polyadenylated 3′ untranslated region of dengue virus and modulates translation efficiency. J. Gen. Virol. 90:687-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prevot, D., J. L. Darlix, and T. Ohlmann. 2003. Conducting the initiation of protein synthesis: the role of eIF4G. Biol. Cell 95:141-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prevot, D., D. Decimo, C. H. Herbreteau, F. Roux, J. Garin, J. L. Darlix, and T. Ohlmann. 2003. Characterization of a novel RNA-binding region of eIF4GI critical for ribosomal scanning. EMBO J. 22:1909-1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ricci, E. P., F. Mure, H. Gruffat, D. Decimo, C. Medina-Palazon, T. Ohlmann, and E. Manet. 2009. Translation of intronless RNAs is strongly stimulated by the Epstein-Barr virus mRNA export factor EB2. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:4932-4943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shatkin, A. J., and J. L. Manley. 2000. The ends of the affair: capping and polyadenylation. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7:838-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith, R. W., and N. K. Gray. 2010. Poly(A)-binding protein (PABP): a common viral target. Biochem. J. 426:1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sonenberg, N., and A. G. Hinnebusch. 2009. Regulation of translation initiation in eukaryotes: mechanisms and biological targets. Cell 136:731-745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Soto Rifo, R., E. P. Ricci, D. Decimo, O. Moncorge, and T. Ohlmann. 2007. Back to basics: the untreated rabbit reticulocyte lysate as a competitive system to recapitulate cap/poly(A) synergy and the selective advantage of IRES-driven translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:e121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strong, R., and G. J. Belsham. 2004. Sequential modification of translation initiation factor eIF4GI by two different foot-and-mouth disease virus proteases within infected baby hamster kidney cells: identification of the 3Cpro cleavage site. J. Gen. Virol. 85:2953-2962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Svitkin, Y. V., H. Imataka, K. Khaleghpour, A. Kahvejian, H. D. Liebig, and N. Sonenberg. 2001. Poly(A)-binding protein interaction with elF4G stimulates picornavirus IRES-dependent translation. RNA 7:1743-1752. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vallejos, M., P. Ramdohr, F. Valiente-Echeverria, K. Tapia, F. E. Rodriguez, F. Lowy, J. P. Huidobro-Toro, J. A. Dangerfield, and M. Lopez-Lastra. 2010. The 5′-untranslated region of the mouse mammary tumor virus mRNA exhibits cap-independent translation initiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 38:618-632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weber, F., E. F. Dunn, A. Bridgen, and R. M. Elliott. 2001. The Bunyamwera virus nonstructural protein NSs inhibits viral RNA synthesis in a minireplicon system. Virology 281:67-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilusz, C. J., M. Wormington, and S. W. Peltz. 2001. The cap-to-tail guide to mRNA turnover. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2:237-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zuker, M. 2003. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:3406-3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]