Abstract

Background: Few reports have addressed associations between family strengths during childhood and adolescent pregnancy and its consequences. We examined relationships among a number of childhood family strengths and adolescent pregnancy, risk behavior, and psychosocial consequences after adolescent pregnancy.

Methods: Our retrospective cohort of 4648 women older than 18 years (mean age, 56 years) received primary care in San Diego, CA. Outcomes included adolescent pregnancy and psychosocial consequences compared with number of the following childhood family strengths: family closeness, support, loyalty, protection, love, importance, and responsiveness to health needs.

Results: Of the cohort, 3082 participants (66%) reported 6 or 7 categories of childhood family strengths. Teen pregnancy occurred in 39%, 33%, 30%, 25%, 24%, 21%, and 19% of those with 0 or 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 childhood family strengths, respectively (p for trend < 0.00001). When childhood abuse and household dysfunction were present, adjusted odds ratios (ORs) for adolescent pregnancy demonstrated an increasingly protective effect as numbers of childhood family strengths increased from 0 or 1 to 2 or 3, 4 or 5, and 6 or 7 (1.0 to 0.80), (1.0 to 0.80, 0.60, and 0.54, respectively). These findings were partly explained by progressive delays in initiation of sexual activity as the number of childhood family strengths increased. Adjusted ORs for psychosocial problem occurring decades later decreased as the number of childhood family strengths increased from 0 or 1 to 2 or 3, 4 or 5, and 6 or 7 (job problems, 1.0, 0.8, 0.6, 0.4; family problems, 1.0, 1.1, 0.7, 0.6; financial problems, 1.0, 0.9, 0.9, 0.6; high stress, 1.0, 1.1, 0.9, 0.8; uncontrollable anger, 1.0, 0.7, 0.7, 0.4).

Conclusions: Childhood family strengths are strongly protective against adolescent pregnancy, early initiation of sexual activity, and long-term psychosocial consequences.

National data describing adolescent childbearing have been available for the US since 1940.1 Teen birth rates over the ensuing 60 years reached an all-time record low of 48.7 births per 1000 women age 15 to 19 years in the year 2000.1 In spite of noteworthy reductions in rates of adolescent pregnancy and birthrates during the 1990s, teen pregnancy rates in the US exceeded those of other industrialized countries by 2 to 15-fold.1–4 Of the approximately 900,000 pregnancies in a typical year,3 about half end in live births and the other half are associated with abortion, miscarriage, or stillbirth.5

Research in prevention since 1990 has identified a variety of factors, including individual, family, peer, and community influences, that protect against early sexual debut and adolescent pregnancy.3,6–11 Several reports have examined the role of adolescents' family context in building resilience and in providing protection against unfavorable reproductive outcomes.6–9,12 Adolescents reporting higher family assets have been significantly less likely to report early sexual debut or adolescent pregnancy. A limitation of these reports, however, is the absence of an analysis on whether the protective effect of family assets persists when the fuller constellation of negative family cofactors is considered.

Recent reports have used the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study to address the association between major causes of death and disability in the US and childhood abuse and family dysfunction.13–21 These and related reports demonstrate strong and graded associations between cumulative exposure to categories of ACE and many unfavorable reproductive health outcomes, including early onset of sexual activity, adolescent pregnancy, sexually transmitted diseases, increased risk of HIV infection, violence perpetration, unintended pregnancy in adulthood, and fetal death.13,14,16,22,23 Data collected in the second wave of the study also included measures of family strengths, which should protect against these unfavorable outcomes. Seven questions used to assess family strengths during childhood covered family closeness, support, loyalty, and protection; feelings of being loved and important; and responsiveness to needs for health care.

We recently reported that ACE had a dose-response effect on adolescent pregnancy and on long-term psychosocial outcomes commonly attributed to adolescent pregnancy.22 Here, we examine whether childhood family strengths protect against adolescent pregnancy, against sexual risk behavior leading to adolescent pregnancy, and against long-term psychosocial outcomes commonly attributed to adolescent pregnancy. Furthermore, we examine whether the protective effect of family strengths remains among women who were exposed to ACE (various types of abuse and household dysfunction, as detailed in the “Methods” section).

Methods

The methods used for the ACE Study have been described in detail.13–22 The study was a retrospective cohort study conducted among adults enrolled in a large health maintenance organization (Kaiser Permanente [KP] Medical Care Program) in San Diego, CA. Approval was granted by the institutional review boards of Emory University and KP and by the office of Human Research Protection, Department of Health and Human Services.

Each year, more than 50,000 adult KP members underwent a standardized biopsychosocial health evaluation, and more than 80% of continuously enrolled members obtained this service at least once over a typical four-year period. The evaluation included a health history, psychosocial evaluation, laboratory studies, and physical examination. The primary purpose of the evaluation is to perform a complete health assessment rather than to provide care that is based on symptoms or illness. The ACE Study sample was drawn from the Health Appraisal Center and consisted of two survey waves (wave I and wave II). Wave I was conducted among 13,494 consecutive KP members attending the Health Appraisal Center between August 1995 and March 1996, and the response rate was 70% (N = 9508). Wave II was conducted between June and October 1997 among 13,330 KP members, and the response rate was 65% (N = 8667). The overall response rate for both waves was 68%. Within two weeks after their clinic visit, participants received a mailed ACE questionnaire that assessed exposure to childhood abuse or household dysfunction and childhood family strengths. The wave II survey included questions on family strengths, which were not included in wave I. Therefore, this study report includes only wave II data. After the exclusion of women who had missing data on race or education (n = 21) or on all categories of childhood family strengths (n = 26), our sample included 4648 women.

Seven questions used to assess family strengths during childhood covered family closeness, support, loyalty, and protection; feelings of being loved and important; and responsiveness to needs for health care.

Definitions of Childhood Family Strengths, Adverse Childhood Experiences, Adolescent Pregnancy, and Psychosocial Consequences

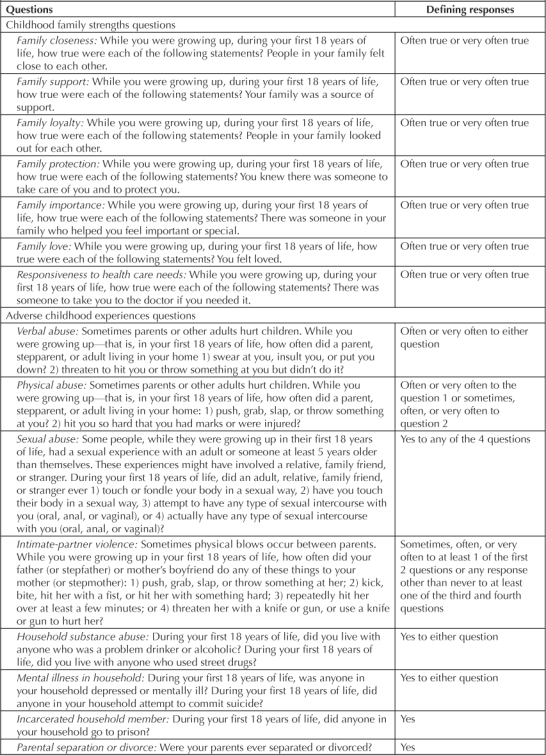

All questions about childhood family strengths and ACE pertained to the respondent's first 18 years of life (Table 1). For the childhood family strengths questions, participants were asked about how applicable to their lives each of seven statements was regarding closeness, support, loyalty, protection, importance, love, and responsiveness to health needs. Response categories included “never true,” “rarely true,” “sometimes true,” “often true,” and “very often true.” The questions about ACE dealt with verbal and physical abuse, contact sexual abuse, violence against one's mother, household substance abuse and mental illness, having an incarcerated household member, and parental separation or divorce. Each of these areas has been described in detail.13–22 Our questions regarding emotional and physical abuse, violence against one's mother,24 contact sexual abuse during childhood,25 and household substance abuse26 were adapted from previously used scales. The childhood family strengths questions were taken from the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire developed by Bernstein et al,27 which has been showed to have high reliability and validity.

Table 1.

Definitions of childhood family strengths and adverse childhood experiences

Information about adolescent pregnancy, defined as a pregnancy that occurs in a female between the ages of 11 and 19 years, was obtained through self-report. The question was “How old were you the first time you became pregnant?” Age of initiation of sexual activity was obtained through the question “How old were you the first time you had sexual intercourse?” Data describing psychosocial consequences were obtained from the Kaiser Health Appraisal questionnaire at the time of interview. Problems with family, jobs, or finances were defined as follows: “Are you now having serious or disturbing problems with your family (yes/no), job (yes/no), or financial matters (yes/no)?” The request used to define high stress was “Please fill in the circle that best describes your stress level (high/medium/low).” The question defining fear of uncontrollable anger was “Have you ever had reason to fear your anger getting out of control (yes/no)?”

Statistical Analyses

The unadjusted associations between each of the seven categories of childhood family strengths and adolescent pregnancy were estimated using relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Subsequently, logistic regression modeling was employed to evaluate the protective association between numbers of categories of childhood family strengths and adolescent pregnancy, as well as long-term psychosocial consequences associated with that event.28 The Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test for linear trend in proportions was used to evaluate whether increasing numbers of family strengths (classified as 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, or 7) were associated with reductions in adolescent pregnancy and with reductions in early initiation of sexual activity.29 Covariates in all models included age, education, and race (“other” vs “white”). Additionally, both ACE and adolescent pregnancy were included in models that examined whether there was a long-lasting protective effect of childhood family strengths on the psychosocial consequences described earlier. Maximum likelihood ratio χ2 were used to evaluate whether the effect of childhood family strengths was significantly modified by the presence of ACE.

Finally, we examined the protective association between childhood family strengths and both adolescent pregnancy and unfavorable psychosocial consequences persisted in analyses stratified by birth cohort, to assess whether our findings might have been influenced by changes in these outcomes over time.

Results

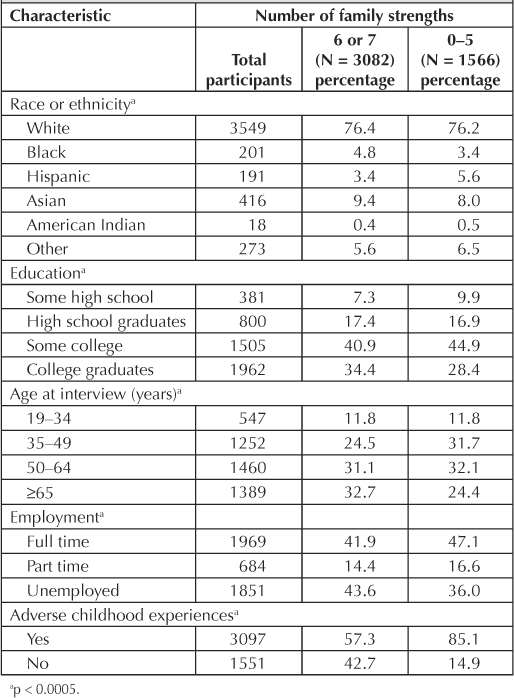

Our study population was racially mixed (76% white), most had attended or completed college, and more than half were age 50 years or older at the time of interview (Table 2). Those reporting 6 or 7 family strengths were significantly more likely than those reporting fewer family strengths to be age 65 years or older at interview and to be unemployed or retired. Although more than half of those with a high number of childhood family strengths (6 or 7) reported having 1 or more ACE, they were significantly less likely than the group with fewer family strengths (0–5) to report a history of ACE (57% vs 85%; p < 0.0005).

Table 2.

Distribution of demographic and behavioral characteristics by childhood family strengths

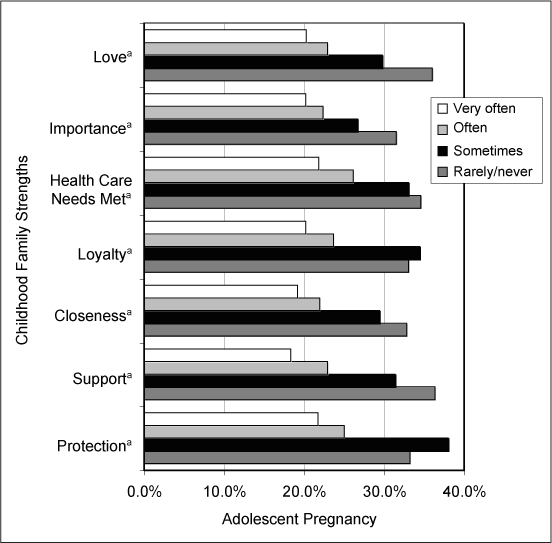

Exposure to each of the seven categories of childhood family strengths was associated with a significant 30% to 40% decreased risk of adolescent pregnancy (data not shown). Compared with women who experienced family strengths never, rarely, or sometimes (“no” in Table 2), those reporting such experiences often or very often (“yes” in Table 2) had reductions in teen pregnancy for each family strength: 37% reduction for protection (35.3% vs 22.0%; RR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.56–0.71); 42%, support (33.5% vs 19.6%; RR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.53–0.65); 34%, closeness (30.7% vs 20.1%; RR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.59–0.73); 37%, loyalty (33.6% vs 21.0%; RR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.56–0.70); 29%, feeling important (29.0% vs 20.8%; RR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.63–0.77); 34%, feeling loved (31.9% vs 21.0%; RR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.59–0.74); and 33%, responsiveness to health care needs (33.4% vs 22.2%; RR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.57–0.78). Furthermore, a significant trend effect on adolescent pregnancy was observed as the frequency of each childhood family strength increased, from “never/rarely” to “sometimes” to “often” to “very often” (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Risk of adolescent pregnancy according to characterization of childhood family strengths.

a p < 0.05.

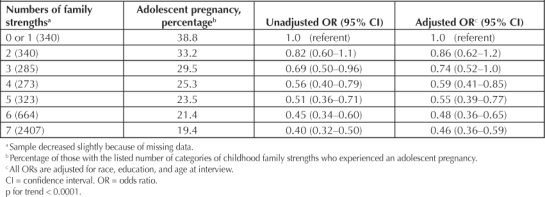

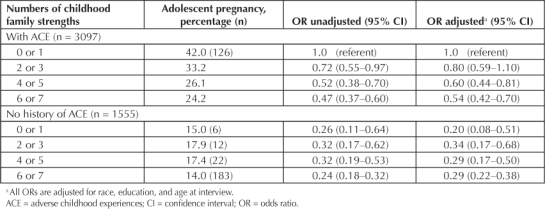

As the number of childhood family strengths increased, the risk of adolescent pregnancy decreased significantly (Table 3). Adjusted odds ratios (OR) for adolescent pregnancy were 1.0, 0.86, 0.74, 0.59, 0.55, 0.48, and 0.46, respectively, among those with 0 to 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 categories of family strengths. The absolute percentage of adolescent pregnancies for women with 7 family strengths (19%) was about half that for women with 0 or 1 family strengths (39%). We found that the magnitude of protective effect of childhood family strengths on adolescent pregnancy was significantly altered by the cofactor of ACE, which functioned as an effect modifier. Among those reporting one or more ACE, there was a highly significant protective (p < 0.000001) trend effect of childhood family strengths against adolescent pregnancy. Adolescent pregnancy rates among those women with ACE decreased from 42% to 33%, 26%, and 24%, respectively, for those reporting 1 to 2, 2 to 3, 4 to 5, and 6 to 7 categories of childhood family strengths (Table 4). After adjustment, we observed a 46% reduction in adolescent pregnancy rates (adjusted OR = 0.54) among with both high family strengths (6 or 7 categories) and coexisting ACE, compared with women with low childhood family strengths (0 or 1 category) and coexisting ACE.

Table 3.

Association between numbers of childhood family strengths and risk of adolescent pregnancy

Table 4.

Numbers of childhood family strengths and adolescent pregnancy until age 18 among women with adverse childhood experiences and those without adverse childhood experiences

Women without ACE, regardless of their family strengths, were at lower risk of adolescent pregnancy than the reference group (ACE, 0 or 1 family strengths; Table 4). No significant difference was seen in the risk of adolescent pregnancy among those with 6 or 7 family strengths (14%) and those with 0 to 5 (combined rate of 17.3%).

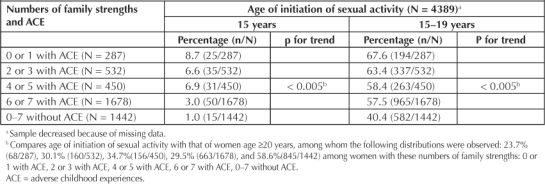

We also examined whether childhood family strengths were associated with delays in initiation of sexual activity in analyses that simultaneously considered ACE (Table 5). Among women with ACE, significant protective trends (p < 0.005) against initiation of sexual activity either before age 15 years or at ages 15 to 19 years (compared with initiation of sexual activity at ages 20 years and older) were seen with greater numbers of childhood family strengths; however, the lowest risk of early initiation of sexual activity was consistently observed among women without ACE and was consistent across the 0 to 7 range of childhood family strengths. Of those with ACE and 0 or 1 family strength, 67.6% initiated sex at age 15 to 19 years; among those with ACE and 6 or 7 family strengths, 57.5% initiated in this age range; among those without ACE and 0 to 7 family strengths, 40.4% of women initiated sexual activity at age 15 to 19 years.

Table 5.

Childhood family strengths and adverse childhood experience status as predictor of age of initiation of sexual activity

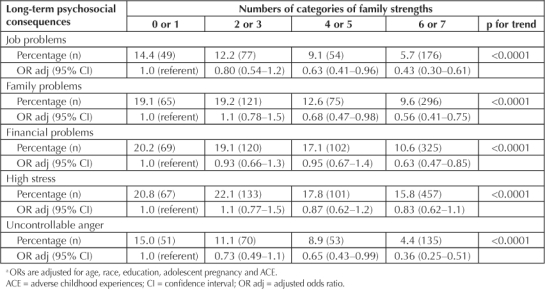

Finally, we analyzed long-term psychosocial consequences, which were measured at the time of interview, when the interviewees were at a mean age of 56 years. We found significant positive trends for childhood family strengths and each of the psychosocial outcomes considered, including serious or disabling problems with jobs, family, or finances, high stress, or uncontrollable anger (Table 6). After adjusting for age, race, education, adolescent pregnancy, and history of coexisting childhood abuse or family dysfunction, we found that a high number of family strengths (6 or 7) led to a significant protective effect against job, family, and financial problems, as well as uncontrollable anger. These findings did not vary by whether ACE were reported.

Table 6.

Numbers of childhood family strengths and long-term psychosocial problems a

In analyses stratified by age cohort (19–34, 35–49, 50–64, and ≥65 years), we found a significant trend for each age cohort when we compared the number of childhood family strengths with the rate of adolescent pregnancy (data not shown). For 0 or 1, to 2 or 3, 4 or 5, and 6 or 7 family strengths, we found that the risk of adolescent pregnancy was as follows (p for trend for each group < 0.0001): 19–34 years: 42.9%, 25.6%, 28.1%, and 16.1%; 35–49 years: 38.2%, 36.6%, 26.4%, and 21.0%; 50–64 years: 39.7%, 35.2%, 26.3%, and 24.0%; and ≥65 years: 36.6%, 22.7%, 18.0%, and 16.4%. Also, for each age cohort, the odds of psychosocial consequences decreased as numbers of family strengths increased (data not shown).

Discussion

Our study findings indicate that a positive childhood protects against adolescent pregnancy in a graded fashion when the character of that childhood is measured in identifiable family strengths. The progressively protective effects of childhood family strengths were especially noteworthy among those who reported ACE, where those with the highest level of family strengths had roughly half the risk of adolescent pregnancy of those with only one or no family strengths. We also found that childhood family strengths were especially protective of early initiation of sexual intercourse among those women who had experienced child abuse or household dysfunction, as measured by ACE. More than half of the women with high levels of childhood family strength reported one or more ACE, indicating that ACE are by no means incompatible with living in a family with numerous strengths. Moreover, we observed that increases in the number of childhood family strengths were associated with progressive reductions in long-term psychosocial problems that have been attributed to adolescent pregnancy, including serious problems with jobs, family, finances, and uncontrollable anger.

Our findings are consistent with those of previous reports, indicating that the quality of family relationships influences the adoption of sexual risk behaviors associated with adolescent pregnancy.7,9,30–34 Specifically, adolescents who perceive their family communication as good or their parents as supportive tend to engage in safer sexual behaviors, including having a later sexual debut, having fewer sex partners, and increasing condom use.7,9,30,31 Similarly, adolescent females who have positive perceptions of their parental relationships appear less likely to experience adolescent pregnancy.7,32 The fundamental role of family strengths in promoting adolescent health was persuasively demonstrated through the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health,6,33,34 which showed that family assets protected adolescents from young age at sexual debut, emotional distress, suicidal thoughts and behaviors, violence, cigarette use, alcohol use, and marijuana use.6

This report extends our previous work, which demonstrated that ACE have a cumulative detrimental effect on both adolescent pregnancy and long-term psychosocial problems that are often attributed to adolescent pregnancy.22,35 Here, we found that family strengths during childhood appear to be factors that protect women against both the harmful short-term (eg, adolescent pregnancy) and long-term effects (eg, psychosocial consequences) of ACE. Furthermore, our findings suggest that the behavioral mechanisms through which childhood family strengths act may delay initiation of sexual activity. Some of the same qualities believed to account for the success of youth-development programs in preventing adolescent pregnancy may explain the effectiveness of family strengths: Both may build competence and confidence by promoting supportive relationships with parents, peers, and/or mentors.3,36–38 It is also conceivable that strong familial interpersonal connectedness during childhood may reduce the tendency to seek that relational closeness by engaging in early sexual activity.

We considered limitations that might have biased our findings. The need to recall exposure to childhood family strengths and ACE might have led to either their under- or over-reporting, but we would not expect mistakes in reporting to differ between those who did and who did not experience an adolescent pregnancy. Thus, any errors in reporting would likely have led to underestimation of the strength of association between family childhood strengths and adolescent pregnancy. A second concern is that our interest in whether childhood family strengths protected against long-term psychosocial sequelae commonly associated with adolescent pregnancy required us to enroll a cohort whose exposure to these protective family strengths occurred three or more decades earlier. Given the many changes that have taken place in the decades since the older women in our cohort were children, the question of whether our findings can be generalized to adolescents or young women of today must be raised. However, even a prospective study addressing long-term sequelae would face this same limitation. The fact that our results regarding both adolescent pregnancy and long-term sequelae for each of the birth cohorts followed the same pattern seen in the general analysis suggests that our findings of a protective effect of family strengths against both adolescent pregnancy and long-term outcomes are robust and enduring.

At a national level, the Healthy People 2010 initiative proposed lowering pregnancy rates for 15- to 17-year-olds by approximately 35% by 2010,39 with programs strategically focused on youth development and/or changing sexual practices.3,38 Our findings suggest that reductions in teen pregnancy may be facilitated by including programs that build family strengths and that such programs appear to have particular potential for prevention among those who have experienced adversity as children. Interventions directed at strengthening the family have a unique potential to provide continuous, progressive, and timely guidance that should improve decision making about sexual and reproductive health matters among adolescents, including promotion of abstinence and prevention of pregnancy among adolescents. Olds et al40,41 have shown that interventions by public-health nurses directed at strengthening at-risk families by home visits can be effective. Public health, media, and Web-based programs that build family strengths in childhood have a strong potential to prevent adolescent pregnancy. Our findings suggest that such strengths have favorable consequences for women's health that likely persist for many years.

… family strengths during childhood appear to be factors that protect women against both the harmful short-term and long-term effects …

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The original study was funded by the US Department of Health & Human Services; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Foundation; and the Kaiser Permanente Garfield Memorial Fund.

Katharine O'Moore-Klopf, ELS, of KOK Edit provided editorial assistance.

Prevention and Cure

“Just say no” prevents teenage pregnancy the way “Have a nice day” cures depression.

— Anonymous

References

- Ventura SJ, Mathews TJ, Hamilton BE. Births to teenagers in the United States, 1940–2000. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2001 Sep 25;49(10):1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller FC. Impact of adolescent pregnancy as we approach the new millennium. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2000 Feb;13(1):5–8. doi: 10.1016/s1083-3188(99)00035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby D. Emerging answers: research findings on programs to reduce teen pregnancy. Washington, DC: The National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- McElroy SW, Moore KA. Trends over time in teenage pregnancy and childbearing: the critical changes. In: Maynard RA, editor. Kids having kids: economic costs and social consequences of teen pregnancy. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press; 1997. pp. 23–54. editor. p. [Google Scholar]

- Alan Guttmacher Institute. Sex and America's teenagers. New York, NY: Alan Guttmacher Institute; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm. Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA. 1997 Sep 10;278(10):823–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittus PJ, Jaccard J. Adolescents' perceptions of maternal disapproval of sex: relationship to sexual outcomes. J Adolesc Health. 2000 Apr;26(4):268–78. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearman PS, Brückner H. Power in numbers: peer effects on adolescent girls' sexual debut and pregnancy. Washington, DC: The National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Miller KS, Levin ML, Whitaker DJ, Xu X. Patterns of condom use among adolescents: the impact of mother–adolescent communication. Am J Public Health. 1998 Oct;88(10):1542–4. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.10.1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodine S, Oman RF, Tolma E, et al. Youth assets and sexual activity among Hispanic youth. Journal of Youth Development. 2008 Summer;3(1):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Oman RF, Vesely SK, Aspy DB, et al. Youth assets and sexual abstinence in Native American youth. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2006 Nov;17(4):775–88. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung EK, Matthew L, Elo IT, Coyne JC, Culhane JF. Depressive symptoms in disadvantaged women receiving prenatal care: the influence of adverse and positive childhood experiences. Ambul Pediatr. 2008 Mar–Apr;8(2):109–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis SD, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Nordenberg D, Marchbanks PA. Adverse childhood experiences and sexually transmitted diseases in men and women, a retrospective study. Pediatrics. 2000 Jul;106(1):E11. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.1.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz PM, Spitz AM, Anda RF, et al. Unintended pregnancy among adult women exposed to abuse or household dysfunction during their childhood. JAMA. 1999 Oct 13;282(14):1359–64. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.14.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anda RF, Croft JB, Felitti VJ, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and smoking during adolescence and adulthood. JAMA. 1999 Nov 3;282(17):1652–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.17.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis SD, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Marchbanks PA. Adverse childhood experiences and sexual risk behaviors in women: a retrospective cohort study. Fam Plann Perspect. 2001 Sep–Oct;33(5):206–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998 May;14(4):245–58. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Chapman DP, et al. Abused boys, battered mothers, and male involvement in teen pregnancy. Pediatrics. 2001 Feb;107(2):E19. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.2.e19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Chapman DP, Williamson DF, Giles WH. Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. JAMA. 2001 Dec 26;286(24):3089–96. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.24.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Edwards VJ, Croft JB. Adverse childhood experiences and personal alcohol abuse as an adult. Addict Behav. 2002 Sep–Oct;27(5):713–25. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Edwards VJ, Williamson DF. Exposure to abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction among adults who witnessed intimate partner violence as children: implications for health and social services. Violence Vict. 2002 Feb;17(1):3–17. doi: 10.1891/vivi.17.1.3.33635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis SD, Anda RF, Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Marchbanks PA, Marks JS. The association between adverse childhood experiences and adolescent pregnancy, long-term psychosocial consequences, and fetal death. Pediatrics. 2004 Feb;113(2):320–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.2.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke NN, Pettingell SL, McMorris BJ, Borowsky IW. Adolescent violence perpetration: associations with multiple types of adverse childhood experiences. Pediatrics. 2010 Apr;125(4):e778–86. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Gelles RJ. Physical violence in American families: risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8,145 families. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt GE. The sexual abuse of Afro-American and white-American women in childhood. Child Abuse Negl. 1985;9(4):507–19. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(85)90060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenborn CA. Exposure to alcoholism in the family: United States, 1988. Adv Data. 1991 Sep 30;(205):1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, et al. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. Am J Psychiatry. 1994 Aug;151(8):1132–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Morgenstern H. Epidemiologic research. New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold; 1982. pp. 255–7. p. [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss JL. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1981. pp. 143–6. p. [Google Scholar]

- Vesely SK, Wyatt VH, Oman RF, et al. The potential protective effects of youth assets from adolescent sexual risk behaviors. J Adolesc Health. 2004 May;34(5):356–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella LV, Conger RD, Simons RL, Whitbeck LB. Predicting risk for pregnancy by late adolescence: a social contextual perspective. Dev Psychol. 1998 Nov;34:1233–45. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.6.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MC. Family and adolescent childbearing. J Adolesc Health. 2001 Apr;28(4):307–12. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00198-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guijarro S, Naranjo J, Padilla M, Gutiérez R, Lammers C, Blum RW. Family risk factors associated with adolescent pregnancy: study of a group of adolescent girls and their families in Ecuador. J Adolesc Health. 1999 Aug;25(2):166–72. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieving RE, McNeely CS, Blum RW. Maternal expectations, mother–child connectedness, and adolescent sexual debut. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000 Aug;154(8):809–16. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.8.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotz VJ, McElroy SW, Sanders SG. The impacts of teenage childbearing on the mothers and the consequences of those impacts for government. In: Maynard RA, editor. Kids having kids: economic costs and social consequences of teen pregnancy. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press; 1997. pp. 55–94. editor. p. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Kuperminc G, Philliber S, Herre K. Programmatic prevention of adolescent problem behaviors: the role of autonomy, relatedness, and volunteer service in the Teen Outreach Program. Am J Community Psychol. 1994 Oct;22(5):617–38. doi: 10.1007/BF02506896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Philliber S, Hoggson N. School-based prevention of teenage pregnancy and school dropout: process evaluation of the national replication of the Teen Outreach Program. Am J Community Psychol. 1990 Aug;18(4):505–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00938057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitz K. Adolescent pregnancy prevention: a review of interventions and programs. Clin Psychol Rev. 1999 Jun;19(4):457–71. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health & Human Services (US) Healthy people 2010: understanding and improving health [monograph on the Internet] 2nd ed. Washington, DC: DHHS; 2000. [cited 2010 Jul 12]. Available from: www.healthypeople.gov/Document/tableofcontents.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Eckenrode J, Henderson CR, Jr, et al. Long-term effects of home visitation on maternal life course and child abuse and neglect. Fifteen-year follow-up of a randomized trial. JAMA. 1997 Aug 27;278(8):637–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Henderson CR, Jr, Chamberlin R, Tatelbaum R. Preventing child abuse and neglect: a randomized trial of nurse home visitation. Pediatrics. 1986 Jul;78(1):65–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]