Abstract

In 2007, Kaiser Permanente's (KP) Southern California Region designed and implemented a systematic in-reach program, the Proactive Office Encounter (POE), to address the growing needs of its three million patients for preventive care and management of chronic disease. The program sought staff from both primary and specialty care departments to proactively identify gaps in care and to assist physicians in closing those gaps. The POE engaged the entire health team in a proactive patient-care experience, creating standard work flows and using information technology to identify gaps in patient care. The goals were to improve consistency of preventive care and improve quality of care for chronic conditions and to improve reliability of staff support for physicians. The POE has been implemented in all outpatient settings in KP's Southern California Region's 13 medical centers and 148 medical office buildings. The program has contributed to significant improvements in key clinical quality metrics, including cancer screenings, blood pressure control, and tobacco cessation. It is now being extended into the inpatient setting and is being shared with other KP Regions.

Introduction

“The necessity of living with a limited supply of physicians in the face of increasing demand forces us to focus on the need for a medical care delivery system that utilizes scarce and costly medical manpower properly.”1 Sidney Garfield, MD, the co-founder of Kaiser Permanente (KP), wrote those words in 1970 for an article that appeared in Scientific American (reprinted in the Summer 2006 issue of The Permanente Journal), but they could well have been written today to describe the growing demands on primary care, particularly for preventive care and management of chronic disease.

The medical literature reports that for a primary care physician to ensure that all patients on a hypothetical panel of 2000 receive the preventive screenings and treatment of chronic diseases that they need, the primary care physician would need to devote an estimated 18 hours per day.2,3 That being the case, it is hardly surprising that only 54.9% of adult patients receive the preventive care recommended by medical evidence.4

Southern California Permanente Medical Group (SCPMG) now serves more than three million KP patients, generating 12 million visits to outpatient offices with 60% of these visits occurring outside of primary care. The concept of the Proactive Office Encounter (POE) began as a question: How can we turn each of these encounters, in either primary or specialty care, into preventive screenings and care for chronic conditions?

This is a simple idea to describe, but implementing it meant a cultural shift. The POE, a regionwide in-reach program, gave ancillary staff and specialty departments more responsibility for preventive screenings and management of chronic care. To succeed, the team had to convince administrators, physicians, and staff of its potential value. Other key elements included:

Electronic tools to identify gaps in any patient's care, regardless of which department they visited

New work flows and training modules to proactively identify gaps in care to draw them to a physician's attention

Reports to monitor improvement in closing gaps and to identify areas needing more support.

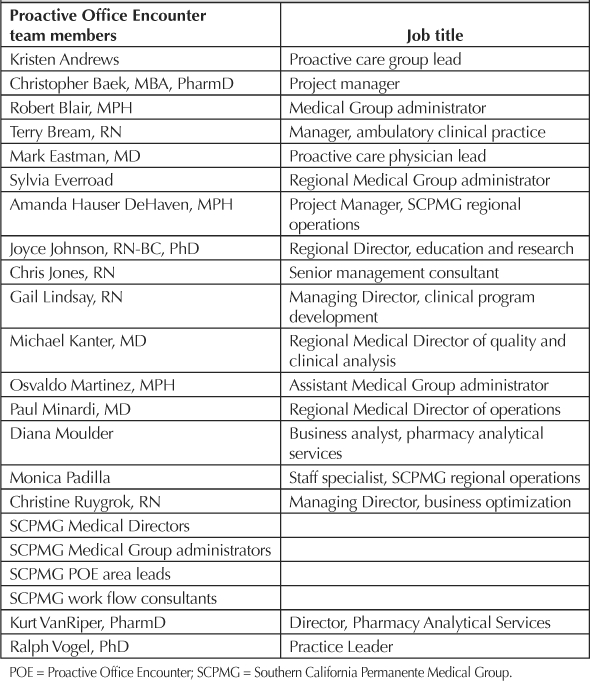

Team members are noted in Table 1. Staff now play a more active role in patient care and the culture has changed so that specialty departments are also responsible for identifying and addressing preventive screenings and chronic care needs. Since its inception, POE has contributed to sharp improvement in the Southern California Region's clinical quality performance, including double-digit improvements in colorectal cancer screening, advice to quit smoking, and blood pressure control.

Table 1.

Proactive Office Encounter team members

Electronic Tools: Step 1 in the Proactive Office Encounter

Early attempts made to systematically identify and address preventive care needs were less comprehensive than the POE; for example, a few years ago, identifying needs required a manual search through a patient's chart and use of a paper checklist (the Care Management Summary Sheet) to identify preventive screenings and gaps in chronic care. The Pharmacy Analytic Services group converted the paper to an electronic checklist on its Permanente Online Interactive Network Tools (POINT) database, though it was not used consistently in all medical offices until integrated into KP HealthConnect, the electronic medical record (EMR).

The electronic POE tools provide physicians and staff with adult primary care, specialty care, and pediatric care checklists (Figure 1), which identify gaps to be addressed and recommended actions. For example, a patient due for a bone-density test or mammogram had a pending order set up and an appointment made for the required examination.

Figure 1.

Computer-screen view of a Proactive Office Encounter checklist for adult primary care.

Additionally, the POE team created shortcuts known as SmartTools within KP HealthConnect to improve efficiency in the medical office. By scrolling through a list of common preventive care needs, a nurse or medical assistant can set up pending orders for screening examinations or supplies, immunizations, or laboratory tests and can select and print appropriate patient information on topics ranging from body mass index to tobacco cessation. Using “SmartPhrases,” staff can document preventive or chronic care actions taken.

Early Technical Challenges

Initially, patient information in POINT and KP HealthConnect was not integrated, creating confusion and mistrust early in the implementation of the POE tool, because alerts were sometimes inaccurate or redundant. The project team worked with Pharmacy Analytics Services and the KP HealthConnect team to integrate the POINT database and the EMR.

The team added functionality to document or to set up pending orders, streamlining these processes to make the POE tool more efficient and user-friendly.

… specialty departments are also responsible for identifying and addressing preventive screenings and chronic care needs.

Methods

Developing and Implementing New Work Flows: Step 2 in the Proactive Office Encounter

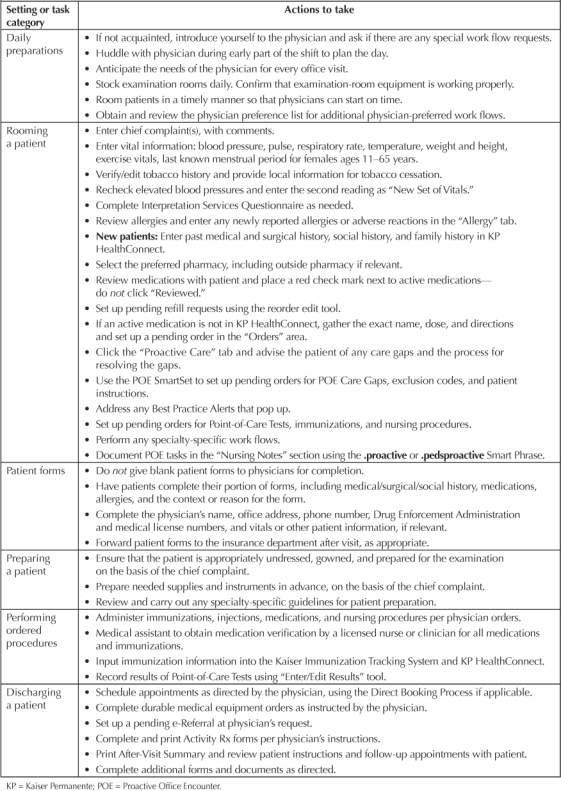

Information technology alone is not sufficient to transform the approach to preventive and chronic care. A standardized structure of work flows and processes was built to address individual care gaps in every outpatient setting (Table 2), to increase efficiency and to improve the reliability and consistency of staff support for physicians.

Table 2.

Standard work flows for all office visits

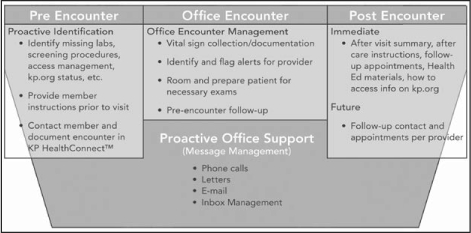

The POE includes three main components, detailed in the next section (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Summary of main components of the Proactive Office Encounter.

Before an Encounter (Pre Encounter)

Before a patient comes in, a medical assistant or nurse reviews the patient's record to identify needed laboratory tests and health screenings, and to determine whether the patient is registered with KP.org, which gives the patient online access to most laboratory results, prescription and immunization status, and the opportunity to e-mail the physician's office.

During an Encounter (Office Encounter)

In the office, the nurse or medical assistant follows a standard workflow (Figure 3) that includes reviewing and updating documentation of the patient's chief complaint, vital signs, physical activity levels, medications, allergies, and preferred pharmacy. The nurse or medical assistant then:

identifies gaps in care using decision-support tools

sets up any necessary pending orders and/or exclusion codes for the clinician

flags needed screenings and/or uncontrolled conditions for the clinician to discuss during the visit

prepares the patient and examination room for procedures (eg, Papanicolaou test, diabetic foot examination, etc), and

assists the clinician through the process.

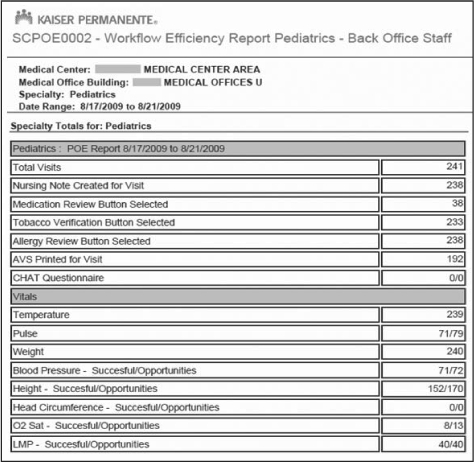

Figure 3.

Computer-screen view of Proactive Office Encounter work-flow efficiency for pediatrics.

After an Encounter (Post Encounter)

Immediately after the visit, the medical assistant or nurse ensures that the patient receives information to obtain preventive screenings or to address health issues, including providing an after-visit summary, after-care instructions, health education materials, information on accessing KP.org, and follow-up appointments or referrals. In addition, the patient may be contacted after the visit at the clinician's direction.

Managing the Change

Because the POE represented a cultural shift, it therefore required a comprehensive change in management approach. In 2007, the POE team widely presented the concept to internal audiences, including Medical Directors, Chiefs, nonphysician administrative leaders, and department managers.

One challenge was ensuring that tasks remained within the scope of practice for medical assistants and nurses. They identified physicians and administrators who could serve as POE team leads at the local level.

The team also developed extensive training materials for both preventive screenings and management of chronic conditions. Participants learned to use the tools and to perform new tasks, for example, communication tips about sensitive patient issues, such as weight. It also provided instructions on how to prepare the patient and the examination room for specific procedures, such as a diabetic foot examination.

Persuading people to work in a new way meant engaging them emotionally. To demonstrate the difference that nonphysician staff can make identifying care gaps, the POE team worked with California's Multimedia Department to produce videos of patients telling how an early screening made a difference in their lives. The videos, which have since been shown in internal meetings and are available on KP's Intranet, included patients' physicians and key staff (including receptionists, medical assistants, and nurses).

By the end of 2007, all primary care offices trained for the POE. The following year, specialty care staff trained on a streamlined version of the program. In 2009, staff in Urgent Care and Emergency Departments (ED) used work flows for the POE. Those concepts now extend to inpatient settings, with four pilot studies underway.

Persuading people to work in a new way meant engaging them emotionally.

Results

Measuring Improvement: Step 3 in the Proactive Office Encounter

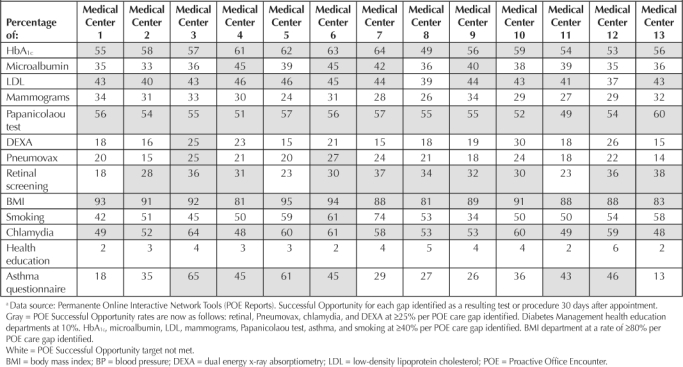

SCPMG measured the program's success by tracking Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set results on a bimonthly basis. In addition, SCPMG developed a new set of reports (dubbed “Successful Opportunities”) to measure improvements specific to the POE (Table 3). These reports monitor the frequency of care gaps closure within 30 days of an appointment, including lead, chlamydia, and osteoporosis screening (dual energy x-ray absorptiometry, or DEXA); pneumococcal immunizations; documentation of height and weight to capture body mass index; asthma questionnaire completion; and health education class attendance. These reports are e-mailed to regional leaders, medical center leaders, and local POE leads for identification of strengths and areas for improvement. Specialists in SCPMG have some of their at-risk moneys contingent on their performance on the Successful Opportunities Report. This has been an important step in getting the specialists involved in the POE.

Table 3.

Proactive Office Encounter: successful opportunity care gap targets met for July 2009 a

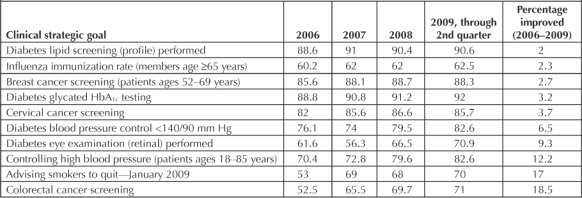

The conclusions drawn from the analysis of these data reveal increased success in closing care gaps at every opportunity resulting in a 2% to 18.5% range of improvement in clinical quality for the conditions of diabetes, cancer, immunization, blood pressure, and smoking (Table 4).

Table 4.

Improvements on key quality measures since implementation of the Proactive Office Encounter

Future Potential for the Proactive Office Encounter

In the outpatient setting, the POE allowed a shift from a reactive care-delivery model to one that is consistently proactive in addressing preventive and chronic care needs. Because SCPMG is part of an integrated system that includes Kaiser Foundation Health Plan and Hospitals, there are more opportunities to expand and embed this approach throughout the organization where patients may seek care, from appointment call centers to hospital discharge.

In the near future, SCPMG intends to implement the POE in pharmacy and inpatient settings. Deployment in EDs and urgent-care settings is already in progress. Pre-encounter automated telephone calls were also piloted in 2008 and were deployed throughout SCPMG by year end. Automated pre-encounter calls target patients with HbA1c, lipid, and/or microalbumin laboratory care gaps and ask that they complete the necessary tests before their office visit to maximize their encounter with their clinician.

Implementing a proactive approach to care also involves continual improvement to the work flows already developed and requires refining the outpatient encounter with specialty-specific work flows, which are in development, for obstetrics, oncology, and nephrology.

With modification of the work flow training materials for SCPMG, other KP Regions could adopt a similar pro-active approach, because other Regions have access to the same KP HealthConnect functionality and SmartTools required to support proactive care. Fully implementing this would require processes and structures for staff and physicians to use those electronic tools to close care gaps. That will require a comprehensive change in management approach, including a communication strategy and an extensive training program. More information and educational videos, job aides, and reference sheets are available from: http://proactivecare.kp.org.

KP's Hawaii Region is now adopting a proactive care approach, embracing principles of the POE. In KP's Mid-Atlantic Region, an ophthalmologist who saw an 82-year-old patient ordered a DEXA scan, which showed osteoporosis (Janice M Beaverson, MD, personal communication, March 2010).a There is much external interest, including in community clinics in Southern California and professional and national health organizations.

Conclusion

The project's impact has been widespread and positive, changing the organization's culture and providing a powerful tool for physician's, staff, and patients. Proactive care is now an expectation of care delivery. Barriers encountered by the team were overcome through a collaborative approach, which involved labor partners, physicians, and leaders in the implementation from the early stages. Correlation data show a positive impact on the delivery of quality care.

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments

Katharine O'Moore-Klopf, ELS, of KOK Edit provided editorial assistance.

References

- Garfield SR. The delivery of medical care. Sci Am. 1970 Apr;222(4):15–23. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0470-15. (Reprinted in Perm J 2006 Summer;10[2]:46–55.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Østbye T, Yarnall KS, Krause KM, Pollak KI, Gradison M, Michener JL. Is there time for management of patients with chronic diseases in primary care? Ann Fam Med. 2005 May–Jun;3(3):209–14. doi: 10.1370/afm.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarnall KS, Pollak KI, Østbye T, Krause KM, Michener JL. Primary care: is there enough time for prevention? Am J Public Health. 2003 Apr;93(4):635–41. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.4.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003 Jun 26;348(26):2635–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]