Abstract

Collecting duct-derived ET-1 regulates salt excretion and blood pressure. We have reported the presence of an inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD)-specific enhancer region in the 5′-upstream ET-1 promoter (Strait, K. A., Stricklett, P. K., Kohan, J. L., Miller, M. B., and Kohan, D. E. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 293, F601–F606). The current studies provide further characterization of the ET-1 5′-upstream distal promoter to identify the IMCD-specific enhancer elements. Deletion studies identified two regions of the 5′-upstream ET-1 promoter, −1725 to −1319 bp and −1319 to −1026 bp, which were required for maximal promoter activity in transfected rat IMCD cells. Transcription factor binding site analysis of these regions identified two consensus nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) binding sites at −1263 and −1563. EMSA analysis using nuclear extracts from IMCD cells showed that both the −1263 and the −1563 NFAT sites in the ET-1 distal promoter competed for NFAT binding to previously identified NFAT sites in the IL-2 and TNF genes. Gel supershift analysis showed that each of the NFAT binding sites in the ET-1 promoter bound NFAT proteins derived from IMCD nuclear extracts, but they selectively bound different NFAT isoforms; ET-1263 bound NFATc1, whereas ET-1563 bound NFATc3. Site-directed mutagenesis of either the ET-1263 or the ET-1563 sites prevented NFAT binding and reduced ET-1 promoter activity. Thus, NFAT appears to be an important regulator of ET-1 transcription in IMCD cells, and thus, it may play a role in controlling blood pressure through ET-1 regulation of renal salt excretion.

Keywords: Gene Regulation, Kidney, NFAT Transcription Factor, Tissue-specific Transcription Factors, Transcription, Endothelin

Introduction

Endothelin-1 (ET-1) is a 21-amino acid peptide initially isolated from endothelial cells that functions as a potent vasoconstrictor (1). Since its discovery, it has become apparent that besides vasoconstriction, ET-1 exerts multiple effects, including regulation of mitogenesis, hypertrophy, synthesis of extracellular matrix, ion transport, and many others (2). In the vast majority of instances, ET-1 exerts its effects via autocrine or paracrine mechanisms, producing localized regulation of cellular functions.

Although most work on ET-1 regulation has been confined to endothelial cells of the vasculature, in the past several years, the kidney has also emerged as a major site of ET-1 actions (3). In the kidney, ET-1 has been shown to modulate a number of important physiological processes, including blood flow, glomerular filtration rate, salt and water excretion, and acid/base handling. Given the critical role ET-1 plays in renal physiology, it was not surprising to discover that almost every cell type in the kidney synthesizes ET-1 and/or contains ET-1 receptors. The kidney is also, by some accounts, 10 times more sensitive to ET-1 actions than the vasculature (4). Finally, within kidney, the inner medullary collecting duct cells may have the highest concentrations of ET-1 immunoreactivity of any cell type in the body (5).

In the nephron, collecting duct cells produce more ET-1 than any other cell type (6). In the collecting duct, ET-1 has been shown to inhibit both sodium (7, 8) and water reabsorption (9). The actions of ET-1 on sodium and water reabsorption make it a target in the study of renal-induced hypertension. Mice containing a collecting duct-specific deletion of the ET-1 gene are hypertensive and have impaired water and sodium excretion (10). Decreased ET-1 production in the collecting duct has also been reported in animal models of hypertension, whereas decreased ET-1 levels have been observed in the urine of patients with essential hypertension (3). These data indicate that collecting duct-derived ET-1 plays an important role in controlling systemic blood pressure by blocking salt and water reabsorption in the collecting duct. Several studies have shown that medullary ET-1 production is increased by salt (11, 12) and water loading (13, 14). However, the cellular factors regulating collecting duct ET-1 production are poorly understood.

ET-1 mRNA has a short half-life (∼15 min), which is directly related to the presence of three destabilizing AUUUA motifs in the 3′-untranslated region (15). This results in ET-1 expression being exquisitely sensitive to transcriptional regulation. To date, several cis-acting elements have been described within the ET-1 promoter. An activator protein (AP-1) site is located at −109 to −102 to which c-Jun-c-Fos binding is required for constitutive promoter activity (16). A GATA binding site is located further upstream (−131 to −136) and acts synergistically with the AP-1 site to produce basal ET-1 promoter activity that is endothelial cell-specific (17, 18). Lesser elements capable of enhancing the GATA-AP-1 induction of ET-1 expression have also been identified within this same proximal promoter region and include NF-κB (19), Smad (20), and Vezf1-DB1 (21), to name a few. The conclusion from these studies was that ET-1 transcription in endothelial cells was robust and driven primarily by cooperative interactions of the AP-1 and GATA sequences in conjunction with several lesser elements, all of which are located within the first 350 bp 5′-upstream of the start site of transcription.

In a previous study from our laboratory (22), we examined the regulation of the ET-1 promoter in endothelial as compared with renal IMCD2 cells. As anticipated from the previous studies cited above, we showed that maximal transcriptional activity of the rat ET-1 promoter in primary cultures of aortic endothelial cells was confined to the first −366 bp of 5′-upstream sequence; additional sequences up to 3.0 kb 5′-upstream produced no further enhancement of promoter activity. However, in similar studies using IMCD cells, we found that the −366-bp region did not produce maximal promoter activity. In IMCD cells, maximal promoter activity (5-fold greater than −366 bp) required additional sequences between 1.0 and 1.7 kb 5′-upstream of the ET-1 transcription start site. The observation that additional regions of the ET-1 promoter are transcriptionally active in IMCD cells may be a reflection of the unique role ET-1 plays in kidney regulation of salt and water homeostasis.

In the current studies, we have sought to further characterize the 5′-upstream region of the ET-1 promoter to identify the regulatory elements that appear selectively active in IMCD cells. Deletion analysis identified two regions of the 5′-upstream ET-1 promoter, −1725 to −1319 bp and −1319 to −1026 bp, which were required for maximal promoter activity in IMCD cells. Computer-assisted transcription factor binding site analysis of these regions identified two consensus NFAT binding sites at −1263 and −1563 bp upstream of the start site of transcription. Site-directed mutagenesis of either site produced a significant reduction in ET-1 promoter activity. EMSA analysis showed that both sites were capable of competing for NFAT binding to previously identified NFAT sites in the IL-2 and TNF genes. Finally, gel supershift analysis showed that each of the NFAT binding sites in the ET-1 promoter bind different NFAT isoforms. Thus, NFAT appears to be an important regulator of ET-1 transcription in IMCD cells, and therefore, it may be an important factor in the regulation of renal salt and water balance and blood pressure.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Type 1 collagenase was obtained from Worthington; penicillin, streptomycin, and glutamine were from Invitrogen; pGL3 and pGL4 vectors were from Promega (Madison, WI); and all other reagents and materials were obtained from Sigma unless stated otherwise.

Cell Culture

Rats were euthanized under anesthesia by cervical dislocation, using a protocol approved by the University of Utah Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. IMCD cells were isolated by first removing the inner medulla and then mincing and incubating it in 5 ml of sucrose buffer (250 mm sucrose, 10 mm triethanolamine, pH 7.4) containing 1 mg/ml Type I collagenase and 0.1 mg/ml DNase I at 37 °C for 40–60 min, with gentle shaking. At the end of the digestion, an additional 5 ml of sucrose buffer was added, and the digest passed through a 100-μm screen. The filtrate was centrifuged at 70 × g for 2 min, the supernatant was aspirated and discarded, and the pellet was washed twice by resuspending in 5 ml of sucrose buffer. The washed IMCD pellet was resuspended in 5 ml of Hanks' balanced salt solution containing 10 mm Hepes, pH 7.4, + 10% BSA and recentrifuged at 70 × g for 5 min. The final IMCD pellet was resuspended in renal epithelial growth medium (Cambex, Watersville, MD) and plated on plastic culture dishes. Cells were grown at 37 °C in 5% CO2 until confluent, ∼4–6 days. IMCD cell culture conditions were modified slightly for transfection experiments, as described under “Transient Transfection Assays”.

ET-1 Promoter-Luciferase Constructs

5′-Serial deletion constructs of the rat ET-1 upstream promoter sequences were generated using our previously described 3.2-kb rat ET-1 promoter construct (22), which contains 3048 bp of the 5′-flanking sequence and 189 bp of the untranslated region of the first exon. Briefly, our 3.2-kb construct (containing −3048 bp of 5′-flanking sequence) was generated using high fidelity Platinum Taq (Invitrogen) PCR from rat genomic DNA and ligated into the XhoI/NheI sites in the pGL3 basic vector (−3048 ET-1 pGL3). Serial deletions of the 5′-end of the 3048-bp flanking sequence were generated using a series of unique restriction enzyme sites: SacI (−1725), NcoI (−1320), SacII (−1026), NheI (−366), and MluI (−75). The fragment to be deleted was removed from the vector by utilizing the pGL3 multiple cloning site enzyme KpnI. The digested pieces were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, isolated, and blunt-ended with Klenow (Invitrogen), and the ends were religated and ultimately transformed into bacteria. All constructs were sequenced to ensure authenticity prior to transfection. The co-transfected control vector, pRL-TK (Promega), contained the promoter for the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (TK) gene linked to the Renilla luciferase reporter. For analysis of the upstream promoter elements, a construct containing only the upstream sequences from −1643 to −1144, ligated upstream of the heterologous TK promoter in the pGL4.23 vector (Promega), was used.

NFAT Consensus Binding Site Mutation

The NFAT consensus binding sites, located at −1263 and −1563 within the −1725 ET-1 luciferase construct, were mutated using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene; Santa Clara, CA). Complementary primers were synthesized to generate a 3-bp change (bold and underlined) within the −1263 and −1563 NFAT consensus GGAAAA sites, which produce G to T mutations at the contact G residues previously shown to disrupt NFAT binding (23). For the −1725 ET-1 Luc mutant NFAT −1263 construct, the mutagenesis primer sequence was 5′-GGCAAAATAGACAGGAAACTGTTCTTAAAACGTAAACACGTTATTAAACGG-3′, together with its reverse compliment, and for the −1725 ET-1 Luc mutant NFAT −1563 construct, the mutagenesis primer sequence was 5′-CTTGGCATCTACTCCCACTTAAAATCGGAGTAGAACAAGAGG-3′, together with its reverse compliment.

Transient Transfection Assays

DNA constructs were transiently transfected into primary cultures of rat IMCD cells. Briefly, cells were grown on 24-well tissue culture plates to greater than 90% confluence. Transfections, using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), were carried out for 18 h according to the manufacturer's protocol, using pRL-TK Renilla luciferase as a control. The following day, the culture medium was changed, and the cells were placed back into a 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator for an additional 24 h. Cells were lysed in passive lysis buffer (Promega) and subjected to freeze/thaw to ensure complete lysis. Luciferase activity in cell lysates was determined using the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay system (Promega). All assays were carried out in a DRC-1 single-sample luminometer (Digene Diagnostics). Data were normalized using pRL-TK, Renilla luciferase.

EMSA

Nuclear extracts were prepared from rat IMCD cell primary cultures or kidney papilla using the NE-PER nuclear protein isolation kit (Pierce Biotechnology). Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA protein assay (Pierce Biotechnology), and the nuclear protein extract was aliquoted and stored at −80 °C. Oligonucleotides containing NFAT binding sites were synthesized and HPLC-purified by the University of Utah peptide synthesis core facility. The following oligonucleotides were synthesized for use as EMSA probes: the interleukin (IL-2) NFAT enhancer sequence (23) 5′-CGCCCAAAGAGGAAAATTTGTTTCATA-3′, the tumor necrosis factor (TNF-76) NFAT enhancer sequence (24) 5′-TCGACAGAGGAAAACTTCCACTCGG-3′, the ET-1563 site 5′-CTACTCCCAGGGAAAATCGGAGTAGAA-3′, and the ET-1263 site 5′-AAACTGTTTGGAAAACGTAAACACGT-3′. Oligonucleotides were end-labeled with [γ-32P]ATP using polynucleotide kinase and purified on G-50 columns (Roche Diagnostics). DNA-protein binding reactions were performed by incubating 5–10 μg of nuclear extract with 15 fmol of 32P-end-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotides in 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA (pH 8), 1 mm DTT, 100 ng/μl poly(dI-dC), 1 mg/ml BSA, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, and 5% (v/v) glycerol. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 30 min at room temperature. Oligonucleotide competitors (200× excess) were added to the nuclear protein extract for 30 min prior to the addition of a radiolabeled probe. DNA-protein bands were resolved by electrophoresis on a 5% 29:1 acrylamide:bisacrylamide gel at 4 °C in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA running buffer. Gels were dried and subjected to autoradiography.

Statistics

All data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance using the Bonferroni correction. p < 0.05 was taken as significant. All data are expressed as means ± S.E. of the mean.

RESULTS

Characterization of the 5′-Upstream ET-1 Promoter

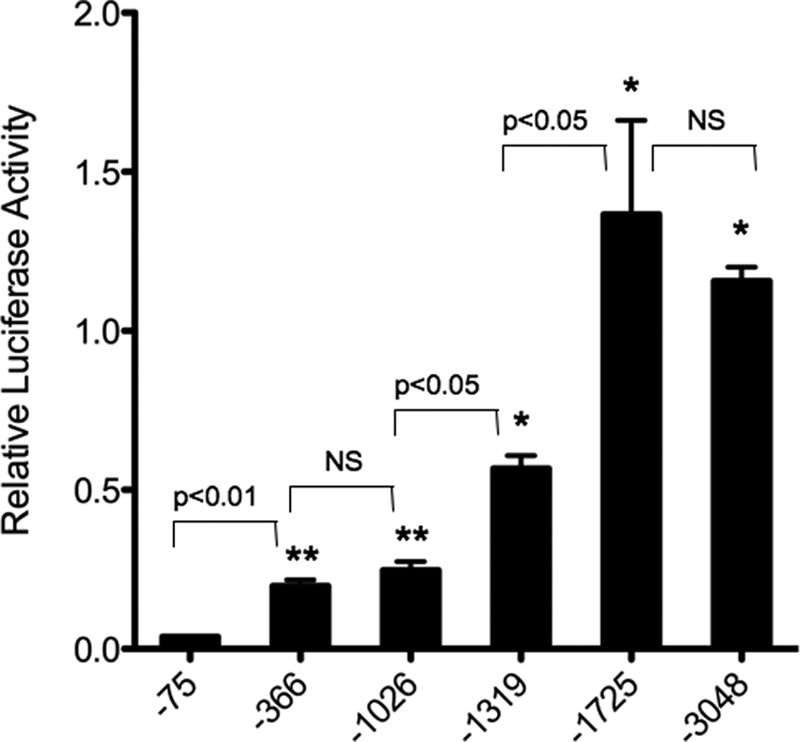

In our previous studies, we demonstrated that −366 bp of the 5′-upstream ET-1 promoter reporter construct (a region containing several enhancer elements previously identified in endothelial cells) produced similar transcriptional activity to a much larger −3048-bp construct when transfected into primary cultures of rat aorta endothelial cells. Similar transfection of primary cultures of rat kidney IMCD cells with the −3048-bp construct produced significantly greater transcriptional activity (5-fold) as compared with the −366-bp construct (22). To characterize/identify potential regulatory elements located in the distal upstream region, beyond −366 bp, which are preferentially active in kidney IMCD cells, a series of 5′-deletion mutants of the −3048-bp ET-1 promoter fragment was generated (Fig. 1). As a control for ET-1 promoter activity, we made a −75-bp ET-1 promoter reporter construct, which has previously been shown to contain only the minimal ET-1 TATA promoter required for correct transcriptional initiation (16). Transfection of the −3048-bp construct into kidney IMCD cells resulted in a 30-fold induction of luciferase reporter activity as compared with the −75-bp control. Deletion of the 5′-end to −1725 produced no significant change in activity as compared with the −3048 fragment. Further deletion to −1319 resulted in a 50% reduction in luciferase activity, whereas deletion to −1026 bp resulted in a further reduction in the activity as compared with the −1319 fragment. Finally, deletion to −366 yielded no difference in promoter activity as that seen with the −1026 construct. Transfection of the −366 construct did produce a 4-fold increase in activity as compared with the minimal −75-bp TATA promoter construct, an indication that the enhancer elements previously identified in endothelial cells are also active in IMCD cells. However, in addition, it appears from our deletion studies that an IMCD cell enhancer region is located between −1026 and −1725 of the ET-1 proximal promoter, far upstream of any of the previously identified ET-1 enhancer elements. Further, the fact that the −1319 construct only partially reduces the IMCD-specific enhancer activity of the −1725 fragment, whereas the −1026 deletion completely eliminates it, indicates that this region may contain multiple enhancer element.

FIGURE 1.

Deletion analysis of the ET-1 proximal promoter. Primary cultures of rat IMCD cells were transiently transfected with a series of 5′-restriction enzyme-generated deletion mutants (see “Experimental Procedures”) of the 3048-bp fragment of the ET-1 promoter region inserted into the pGL3-Basic luciferase-containing reporter vector. Relative transcriptional activity of the various constructs is shown. The minimal ET-1 promoter (−75 bp) containing only the start site for transcription was transfected as a base-line control. Data are expressed as relative luciferase activity. The results are the mean ± S.E. (n = 12). *, p < 0.001 versus −75 bp; **, p < 0.01 versus −75 bp. NS, nonspecific.

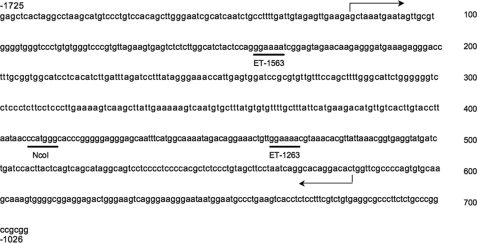

The sequence of the −1026 to −1725 region of the ET-1 proximal promoter, containing IMCD enhancer activity, is shown in Fig. 2. Computer-assisted analysis of this region using TRANSFAC 7.0 software was employed to search for potential enhancer elements. This search identified two sequences (GGAAAA) at −1263 (ET-1263) and −1563 (ET-1563) bp that have previously been shown, in several other genes, to be NFAT consensus binding sites (24, 25). In the distal ET-1 promoter, these two NFAT binding sequences are bisected by the NcoI site used to create the −1319 construct. The location of these two NFAT consensus sites is consistent with our deletion analysis as the loss of one site (ET-1563) in the −1319 construct is consistent with the reduced transcriptional activity of the −1319 construct as compared with the −1725 fragment (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 2.

Sequence analysis of the −1026 to −1725 region of the ET-1 proximal promoter. The 700-bp region from −1725 (SacI) to −1026 (SacII) is shown. Highlighted are the NFAT consensus sequences (GGAAAA) contained within this region, at −1563 and at −1263 (underlined). Also shown is the NcoI site used to generate the −1319 deletion fragment (Fig. 1) that bisects the sites. Finally, the arrows indicate the 5′- and 3′-ends of a 500-bp (−1643 to −1144) sequence that was used to drive expression of a minimal TK promoter vector in Fig. 3.

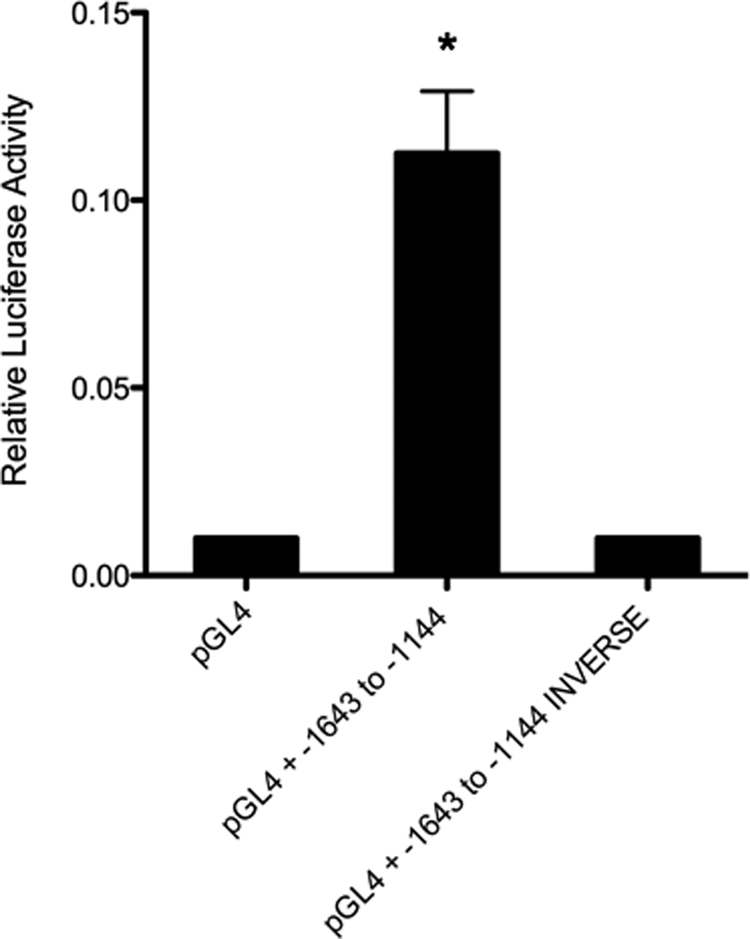

To test whether this distal IMCD enhancer region was capable of autonomous enhancer activity or whether it required the presence of the previously identified elements located within the −366-bp region, we inserted this region of the 5′-upstream ET-1 promoter into a heterologous TK promoter reporter vector. A 500-bp sequence (−1144 to −1643; Fig. 2, arrows) of the distal ET-1 promoter region was inserted upstream, in both orientations, and transfected into IMCD cells (Fig. 3). Transfection of the empty TK vector into IMCD cells produced low level luciferase expression that was induced by ∼10-fold when the 500-bp fragment (−1144 to −1643) was inserted upstream of the minimal TK promoter, in the correct orientation. Thus, this region of the ET-1 proximal promoter is capable of enhancing transcriptional activity in IMCD cells, independent of the previously identified enhancers in the −366-bp region. Furthermore, the enhancer activity contained within the −1144 to −1643 region appears to be orientation-dependent as inserting the fragment in the inverse direction to the TK promoter yielded no luciferase activity above that seen with the empty TK vector.

FIGURE 3.

A region of the ET-1 proximal promoter, −1643 to −1144 bp, is capable of transcriptional regulation of a heterologous promoter. A 500-bp region (Fig. 2) of the proximal ET-1 promoter was cloned, in both the correct and the reverse orientation, upstream of the minimal TK promoter in pGL4 luciferase. Relative transcriptional activity of the constructs is shown. The empty pGL4 luciferase vector was transfected as a base-line control. Data are expressed as relative luciferase activity. The results are the mean ± S.E. (n = 12). *, p < 0.01 versus pGL4 alone.

EMSA Analysis of NFAT Binding to Sequences within the ET-1 Promoter

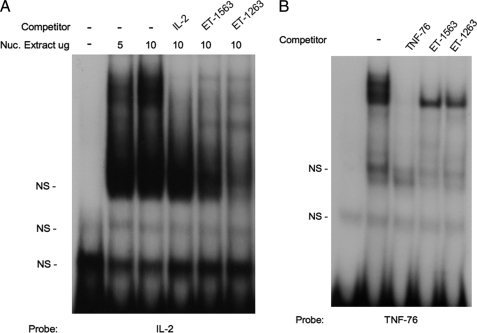

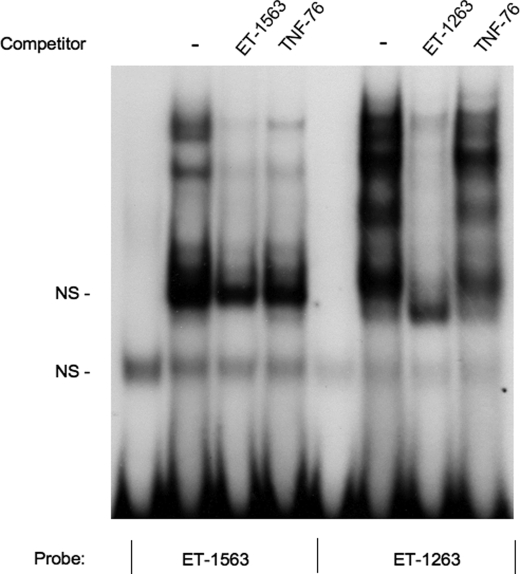

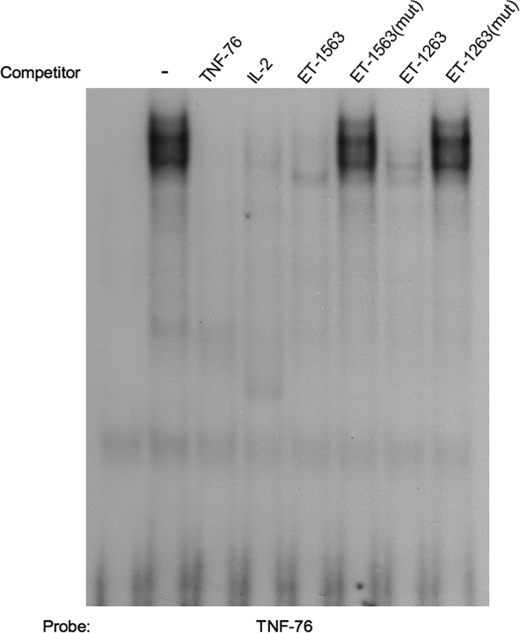

To determine whether the ET-1263 or ET-1563 NFAT sites can bind NFAT proteins in vitro, EMSAs were performed. Initially, we examined the ability of the ET-1 NFAT sequences to compete for NFAT protein binding to consensus sites previously identified in other genes (Fig. 4). Incubation of an oligonucleotide containing the NFAT consensus sequence from the murine IL-2 enhancer, with nuclear extracts from rat IMCD primary cultures, produced a gel retardation complex of the IL-2 oligonucleotide (Fig. 4A, lanes 2 and 3 from left), similar to what was reported (23). The addition of excess cold IL-2 oligonucleotide blocked formation of the DNA-protein retardation complex (Fig. 4A, lane 4 from left). The addition of cold excess oligonucleotide containing either the ET-1263 or the ET-1563 sequence to the IL-2 IMCD nuclear extract incubation also blocked formation of the gel shift complex (Fig. 4A, lanes 5 and 6 from left). Studies utilizing an oligonucleotide containing the NFAT consensus from the TNF gene (TNF-76 NFAT) (24) showed similar results (Fig. 4B). Incubation of labeled TNF oligonucleotide containing the NFAT consensus sequence with IMCD nuclear extracts produced a retardation band that was competed with cold TNF oligonucleotide, as well as with cold ET-1263 and ET-1563. The results from these gel shift competition studies show that both the ET-1263 and the ET-1563 sequences are capable of competing with known NFAT binding sites for nuclear protein binding. To test whether the ET-1 NFAT sequences can bind IMCD nuclear proteins directly, we performed EMSA analysis of each of them (Fig. 5). EMSAs using labeled ET-1563 NFAT (Fig. 5, lanes 1–4 from left) produced similar gel retardation band patterns to those seen in Fig. 4 with the IL-2 and TNF NFAT sequences. The retarded bands for the ET-1563 were competed with excess cold ET-1563 and with excess cold TNF-76 oligonucleotide containing the NFAT consensus sequence. A similar result was observed using labeled ET-1263 (Fig. 5, lanes 5–8 from left). Incubation of the labeled ET-1263 oligonucleotide with IMCD nuclear extracts resulted in the appearance of several retarded bands, which once again were competed with cold excess ET-1263 and the TNF-76 NFAT oligonucleotides.

FIGURE 4.

EMSA competition analysis using the ET-1 −1263 and −1563 NFAT sequences. A, 32P-labeled NFAT binding element from the murine IL-2 enhancer. Lane 1, probe alone; lane 2, incubated with 5 μg of IMCD nuclear protein extract (Nuc. Extract); lanes 3–6, incubated with 10 μg of IMCD nuclear protein extract (lanes numbered from left). NS, nonspecific. B, 32P-labeled NFAT binding element from the TNF promoter. Lane 1, probe alone; lanes 2–5, incubated with 5 μg of IMCD nuclear extract. All cold competitor oligonucleotides were added at 200× excess.

FIGURE 5.

Gel shift and competition analysis of 32P-labeled ET-1 −1263 and −1563 NFAT sequences. Oligonucleotides containing the ET-1263 or ET-1563 sequences were 32P-labled and incubated with nuclear extracts from IMCD cells in the presence and absence of cold excess competitor oligonucleotides. Lane 1, 32P-labeled ET-1563 oligonucleotide; lanes 2–4, labeled ET-1563 with the addition of 5 μg of IMCD nuclear protein extract; lane 5, 32P-labled ET-1263; lanes 6–8, labeled ET-1263 with the addition of 5 μg of IMCD nuclear extract (lanes numbered from left). All cold competitor oligonucleotides were added at 200 × excess. NS, nonspecific.

Identification of NFAT Isoform Binding to ET-1 Promoter Elements by Gel Supershift Analysis

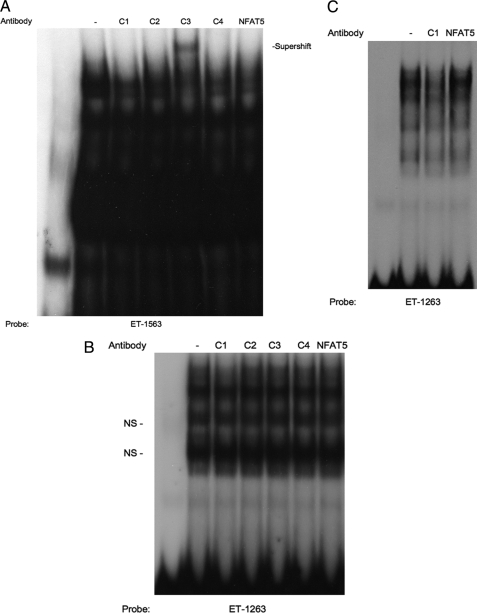

To identify the specific NFAT protein isoforms that bind to the −1263 and −1563 NFAT elements, gel supershift experiments were performed (Fig. 6). Labeled ET-1263 or ET-1563 NFAT oligonucleotides were incubated with IMCD cell nuclear extracts in the presence or absence of antibodies that recognize NFAT-c1, -c2, -c3, -c4, or NFAT5. As visible in panel A, the anti-NFAT-c3 antibody was able to supershift the ET-1563 IMCD protein complex. None of the other antisera supershifted or interfered with IMCD protein binding to the ET-1563 site. The fact that only a portion of the retarded band was supershifted, even in the presence of excess antibody, is a potential indication that other, non-NFAT proteins may also bind the ET-1563 site. This is consistent with preliminary experiments in our laboratory that indicate the ET-1563 oligonucleotide is able to compete for IMCD nuclear extract binding to an NF-κB consensus sequence (data not shown). Supershift analysis using ET-1263 (panel B) produced a very different result. None of the antibodies produced a supershifted band, including the NFAT-c3 antisera that supershifts the ET-1563 site. Thus, at least some of the proteins from IMCD nuclear extract that bind the ET-1263 are different from those that bind the ET-1563 site. Closer examination of the ET-1263 supershift gel (Fig. 6B) shows a slight decrease in intensity of the upper bands by the NFAT-c1 antibody. Loss of protein binding (as opposed to supershifting) with the NFAT-c1 antibody is consistent with previous reports in the literature using this antiserum (26). However, due to the presence of multiple nonspecific shifted bands, using IMCD cell extracts, it is difficult to definitively conclude that the NFATc1 antibody blocked NFAT binding to the ET-1263 site. In kidney inner medulla, the papilla is a rich source of IMCD cells as it is comprised predominately of collecting duct tubules. Therefore, we performed supershift analysis of the ET-1263 site using papilla nuclear extracts and the NFAT-c1 and NFAT5 antisera with the goal of providing a more definitive result in the hope that isolating nuclear extracts from a tissue source would allow us to obtain a more enriched nuclear extract (Fig. 6C). Using papilla extract, the competition by the NFAT-c1 antibody for binding to the ET-1263 site is much easier to distinguish due to the reduction in interference from the other nonspecific retarded bands. For reference, including the NFAT5 antibody had no effect on papilla nuclear protein binding to the ET-1263 site. Similar to what is seen with IMCD extract, incubating the NFAT-c2, -c3, and -c4 antisera with papilla nuclear extracts had no effect on the ET-1263 gel shift (data not shown). These results indicate that the ET-1 NFAT sites directly bind NFAT proteins. However, the data also point to the fact that although each of the ET-1 NFAT sites contains the same core NFAT consensus sequence, they bind different NFAT isoforms.

FIGURE 6.

Supershift analysis of 32P-labeled oligonucleotides containing the ET-1263 NFAT and ET-1563 NFAT sequences. A, 32P-labeled ET-1563 oligonucleotide incubated with 5 μg of IMCD nuclear protein extract. Lanes 3–7, IMCD nuclear protein extracts were preincubated for 1 h with anti-NFAT antibodies. All lanes are numbered from left. B, 32P-labeled ET-1263 oligonucleotide incubated with 5 μg of IMCD nuclear protein extract. Lanes 3–7, IMCD nuclear protein extracts were preincubated for 1 h with anti-NFAT antibodies. C, 32P-labeled ET-1263 oligonucleotide incubated with 5 μg of papilla nuclear protein extract was preincubated for 1 h with anti-NFAT antibodies. NS, nonspecific.

Mutational Analysis of the ET-1 Promoter NFAT Binding Sites

The EMSA data above indicate that although the ET-1263 and ET-1563 oligomers contain the same NFAT consensus binding sequence (GGAAAA), they bind different proteins when incubated with IMCD nuclear extracts. This difference in protein binding is seen by differences in their gel shift banding patterns and, more importantly, by supershift analysis that indicates that they even bind different isoforms of NFAT. Given the fact that the oligomers used in the gel shift assay are 26- and 27-mers, we thought it important to test whether the NFAT consensus sequence was required for NFAT binding. We synthesized a series of oligomers containing selective nucleotide mutations for use in EMSA competition assays. The mutation involved conversion of both guanine residues to thymidine within the NFAT consensus sequence (GGAAAA to TTAAAA). This mutation has previously been shown to prevent binding of all the NFAT isoforms and also eliminates NFAT transactivation in transfection assays (23). EMSA studies using the mutated ET-1 promoter oligonucleotides to compete for NFAT binding to the TNF-76 consensus sequence are shown in Fig. 7. As shown in the figure and previously demonstrated earlier in Fig. 4B, incubation of IMCD nuclear extract with TNF-76 oligonucleotide results in protein-DNA binding (lane 2 from left). The addition of excess cold TNF-76, wild type (WT) ET-1563, or WT ET-1263 competed for the protein binding (lanes 3, 5, and 7 from left, respectively). Mutation of the NFAT consensus sequence within the ET-1563 and ET-1263 elements eliminated their ability to successfully compete for protein binding (lanes 6 and 8 from left, respectively). These studies demonstrate that although these elements may bind proteins other than NFAT, the NFAT consensus sequence GGAAAA is critical for any protein binding to these sites. We must conclude that differences in the flanking sequences surrounding the consensus NFAT binding site play an important role in facilitating the binding of certain NFAT isoforms, either directly or by coordinating the binding of isoform-specific dimer partners.

FIGURE 7.

Gel shift competition using mutated ET-1263 and ET-1563 oligonucleotides. 32P-labeled NFAT binding element from the TNF promoter was incubated with 5 μg of IMCD nuclear extract. Competition for protein binding was performed by the addition of 200× cold competitor oligonucleotides containing either the WT NFAT consensus sequence (GGAAAA), found in both the ET-1263 and the ET-1563 promoter elements, or the same oligonucleotides containing a mutated (mut) NFAT consensus sequence (TTAAAA) in which both guanine nucleotides were replaced with thymidine.

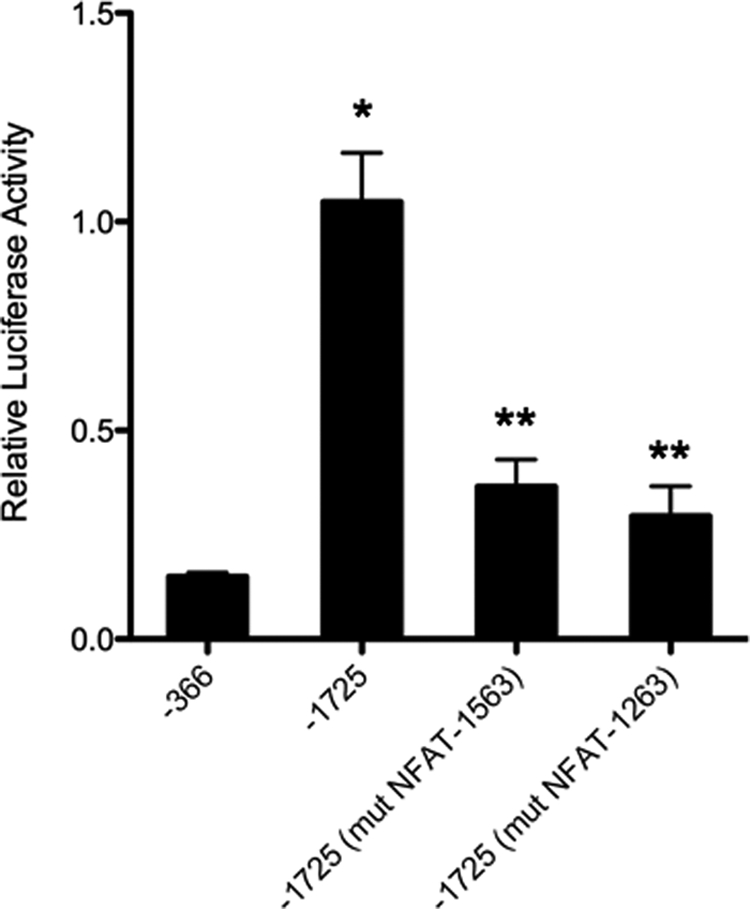

Finally, although the EMSA studies clearly demonstrate that both of these sites are capable of binding NFAT proteins, the question remains as to whether the NFAT consensus binding sites located at ET-1263 and ET-1563 bp regulate ET-1 promoter activity in IMCD cells. Therefore, we generated ET-1 promoter reporter constructs containing point mutations within the NFAT consensus sequences, at ET-1263 and ET-1563 bp. We introduced the same G to T mutations used in the EMSAs above into the −1725 ET-1 promoter luciferase construct and transfected them into IMCD cells (Fig. 8). We also transfected the −366-bp construct as a control. As shown previously, transfecting the WT −1725 promoter luciferase produced a large induction of luciferase reporter activity as compared with the control −366 ET-1 luciferase construct. Introducing mutations into the −1725 construct at either the ET-1563 or the ET-1263 NFAT consensus binding sequences resulted in a 60–70% decrease in promoter activity. We interpret these results to indicate that the NFAT consensus sites at ET-1563 and ET-1263 are functional DNA enhancer elements, capable of regulating transcription of the ET-1 gene in IMCD cells of the kidney.

FIGURE 8.

Mutation of the NFAT sequences in the ET-1 proximal promoter affects transcriptions. Primary cultures of rat IMCD cells were transiently transfected with the 1725-bp ET-1 promoter in pGL3 luciferase or the 1725-bp region containing the GG to TT mutation (mut) of the NFAT-consensus binding site at −1263 or −1563 (Fig. 7). Relative luciferase activity of the various constructs is shown. The −366-bp ET-1 promoter was transfected as a reference control. Data are expressed as relative luciferase activity. The results are the mean ± S.E. (n = 12). *, p < 0.001 versus −366 bp; **, p < 0.01 versus −1725 bp alone and p < 0.05 versus −366 bp.

DISCUSSION

Previously, using ET-1 promoter reporter transfection assays, we identified a distal region located −1.0 to −3.0 kb 5′-upstream of the ET-1 promoter that was required for maximal expression of ET-1 in IMCD cells (22). Transfection of this same region into primary cultures of aorta endothelial cells produced no increase in ET-1 promoter activity. In endothelial cells, maximal ET-1 promoter activity was achieved with as little as −366 of the proximal promoter, an indication that this region may also contain cell type-specific enhancer elements. In the present study, through the use of deletion and mutational analyses, we have identified two previously unrecognized consensus NFAT binding sites located at −1263 and −1563 bp upstream of the start site of transcription in the ET-1 promoter that appear to play a significant role in the increased distal ET-1 promoter activity observed in IMCD cells. In addition, to our knowledge, this constitutes the first detailed characterization of NFAT regulation of the ET-1 promoter in any cell type.

NFAT proteins are found in nearly every cell in the body and comprise a family of transcription factors (NFATs 1–5) that regulate the expression of genes involved in a wide range of cellular processes, such as immune response, vertebrate development, cell proliferation, and organ development (27). The NFAT proteins contain a DNA binding, Rel homology domain (RHR) and are, therefore, part of a larger superfamily of Rel domain proteins that include the NF-κB proteins. Members of the Rel family of transcription factors bind GGA core DNA motifs. For the NFAT proteins, the GGA motif is flanked at its 3′-end with an adenine tract to yield 5′-GGAAAA-3′ as the consensus NFAT binding site. In the ET-1 promoter, both the ET-1263 and the ET-1563 sites contain the consensus GGAAAA NFAT binding motif.

The NFAT proteins can bind to DNA as homo- and heterodimers, often with other members of the Rel family (28). Sites that can bind NFAT and NF-κB have been found in the HIV-LTR, IL-8, and IL-13 (27). In our EMSA studies, we observed a complex pattern of shifted bands similar to what several other laboratories have reported using other NFAT sites (29–31). The presence of multiple gel-shifted bands is consistent with the presence of NFAT monomer and dimer binding to DNA elements. Although the ET-1263 and ET-1563 enhancer elements both contain the same consensus GGAAAA site, the NFAT DNA binding at each site appears dramatically different, as evidenced by differences in the pattern and number of shifted bands between the ET-1263 and the ET-1563 sites and supershift analysis that indicates that NFATc3-NFAT4 preferentially binds the −1563 site, whereas NFATc1-NFAT2 binds the ET-1263 site.

NFAT proteins are also capable of forming strong cooperative complexes with unrelated transcription factors such as GATA, Maf, Oct, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ, and AP-1-Jun-Fos (25) on “composite” elements. Of the non-related binding partners, NFAT-Jun-Fos complexes have been the most extensively studied. Composite elements containing both NFAT and AP-1 binding sites have been identified in several genes (25). Complexes of NFAT-Jun-Fos serve as signal integrators for two of the major pathways in the cell: calcium/calcineurin activation of NFAT and the DAG/protein kinase C (PKC) activation of Jun-Fos. In the case of ET-1, there is extensive literature on the effects of PKC on the expression of both ET-1 mRNA and protein (18, 32, 33). As mentioned in the Introduction, an AP-1 site has previously been identified in the ET-1 proximal promoter region (−109 to −102) (16). The presence of multiple gel-shifted bands is consistent with both the presence of NFAT dimer binding and the presence of a composite NFAT element. Whether either of the identified ET-1 NFAT binding sites functions as a composite NFAT-AP-1 site or whether there is cooperative interaction between the ET-1563 and the ET-1263 sites and the AP-1 site in the proximal promoter or interaction with other distal AP-1 sites is an area of active investigation in our laboratory.

The inactive form of the NFAT proteins 1–4 is found in the cytoplasm. Activation is initiated by dephosphorylation of the NFAT regulatory domain by the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent phosphatase calcineurin. Activation of calcineurin in the cell is tied to increases in intracellular Ca2+ mediated by phospholipase C coupled to plasma membrane receptors and “store-operated” Ca2+ channels. Calcium is one of the most extensively studied regulators of ET-1 production (22, 33). Despite this, the effects of Ca2+ on ET-1 synthesis are quite variable between cell types. The current studies may help explain some of these differences in ET-1 regulation by Ca2+. In our previous studies on ET-1 promoter regulation in IMCD cells, the calmodulin inhibitor W7 completely blocked the activity of the distal regulatory elements located between −1026 and −3048 bp yet had no effect on the −1026 or the −366-bp ET-1 promoter fragments (22). The presence of NFAT enhancer elements at ET-1263 and ET-1563, within the −1026 to −3048 W7-sensitive region, suggests a mechanism for the actions of W7; W7 may block Ca2+/calmodulin activation of calcineurin, resulting in a loss of NFAT activity at the ET-1263 and ET-1563 enhancer elements. Furthermore, the variability in Ca2+ effects on ET-1 production, previously reported in the literature (6) may be accounted for by the fact that the distal enhancer region that contains the NFAT binding sites shows tissue-specific activity because it is active in IMCD cells, but not in endothelial cells (22). Full confirmation of this hypothesis awaits additional studies.

Published studies have shown that the tonicity-responsive enhancer-binding protein (TonEBP-NFAT5) is expressed in IMCD cells (34). Given the high tonicity environment in which the cells of the IMCD reside, we were somewhat surprised that we did not observe NFAT5-TonEBP binding to either of the ET-1563 or the ET-1263 elements in our supershift experiments. One possible explanation for the lack of observable NFAT5 binding could be due to obtaining nuclear extracts for gel shift from cultured IMCD cells grown in isotonic media, thereby lacking the high tonicity environment required for NFAT5 induction. Further studies are planned to address this possibility.

The current study provides convincing evidence that NFAT proteins regulate expression of ET-1 in IMCD by binding to the ET-1 promoter at both the ET-1563 and the ET-1263 elements. Ultimately, one must consider the physiologic relevance of this ET-1 regulatory system. As stated earlier, collecting duct ET-1 plays a vitally important role in controlling renal sodium excretion and maintaining normal blood pressure. Knock-out of ET-1 or both ETA and ETB receptors in the collecting duct causes severe salt-sensitive hypertension and sodium excretion (10, 35–37). Collecting duct ET-1 production is increased by high sodium or water intake, thereby stimulating ET-1 autocrine inhibition of collecting duct sodium and water reabsorption and preventing an increase in blood pressure (3, 6). Furthermore, reduced urinary ET-1 excretion is associated with hypertension in experimental animals and in humans (3). Thus, how collecting duct-derived ET-1 is regulated is a fundamentally important biologic question. Our current study suggests that NFAT is one factor that potentially plays a significant role in modulating collecting duct ET-1 production and that such regulation may be unique to this cell type (at least as compared with endothelial cells). Additional studies will be required to determine the functional significance of these NFAT binding sites in the physiologic regulation of ET-1 expression in kidney.

Taken together with our previous studies showing the importance of Ca2+ and calmodulin in controlling collecting duct ET-1 synthesis, the present study helps to build the framework of a signaling pathway that transmits external signals to the collecting duct, leading to alterations in ET-1 production. A key question is what is the nature of such external signals; although these are being actively investigated, the finding that NFAT isoforms are important suggests that continued efforts to understand how NFAT isoforms act and how they are regulated in the collecting duct will likely yield significant insight into how the ET-1 system in this cell type is controlled.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant DK96392 (to D. E. K.).

- IMCD

- inner medullary collecting duct

- NFAT

- nuclear factor of activated T-cells

- TK

- thymidine kinase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yanagisawa M., Kurihara H., Kimura S., Tomobe Y., Kobayashi M., Mitsui Y., Yazaki Y., Goto K., Masaki T. (1988) Nature 332, 411–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubanyi G. M., Polokoff M. A. (1994) Pharmacol. Rev. 46, 325–415 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kohan D. E. (2006) Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 15, 34–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pernow J., Franco-Cereceda A., Matran R., Lundberg J. M. (1989) J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 13, Suppl. 5, S205–S206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitamura K., Tanaka T., Kato J., Eto T., Tanaka K. (1989) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 161, 348–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kohan D. E. (1997) Am. J. Kidney Dis. 29, 2–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeidel M. L., Brady H. R., Kone B. C., Gullans S. R., Brenner B. M. (1989) Am. J. Physiol. 257, C1101–C1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallego M. S., Ling B. N. (1996) Am. J. Physiol. 271, F451–F460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomita K., Nonoguchi H., Marumo F. (1991) Contrib. Nephrol. 95, 207–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahn D., Ge Y., Stricklett P. K., Gill P., Taylor D., Hughes A. K., Yanagisawa M., Miller L., Nelson R. D., Kohan D. E. (2004) J. Clin. Invest. 114, 504–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang T., Terada Y., Nonoguchi H., Ujiie K., Tomita K., Marumo F. (1993) Am. J. Physiol. 264, F684–F689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Migas I., Bäcker A., Meyer-Lehnert H., Kramer H. J. (1995) Am. J. Hypertens 8, 748–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeiler M., Löffler B. M., Bock H. A., Thiel G. (1995) J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 26, Suppl. 3, S513–S515 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Modesti P. A., Cecioni I., Migliorini A., Naldoni A., Costoli A., Vanni S., Serneri G. G. (1998) Am. J. Physiol. 275, H1070–H1077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inoue A., Yanagisawa M., Takuwa Y., Mitsui Y., Kobayashi M., Masaki T. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264, 14954–14959 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee M. E., Bloch K. D., Clifford J. A., Quertermous T. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 10446–10450 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee M. E., Temizer D. H., Clifford J. A., Quertermous T. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 16188–16192 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee M. E., Dhadly M. S., Temizer D. H., Clifford J. A., Yoshizumi M., Quertermous T. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 19034–19039 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quehenberger P., Bierhaus A., Fasching P., Muellner C., Klevesath M., Hong M., Stier G., Sattler M., Schleicher E., Speiser W., Nawroth P. P. (2000) Diabetes 49, 1561–1570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodríguez-Pascual F., Reimunde F. M., Redondo-Horcajo M., Lamas S. (2004) J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 44, Suppl. 1, S39–S42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aitsebaomo J., Kingsley-Kallesen M. L., Wu Y., Quertermous T., Patterson C. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 39197–39205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strait K. A., Stricklett P. K., Kohan J. L., Miller M. B., Kohan D. E. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 293, F601–F606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Northrop J. P., Ho S. N., Chen L., Thomas D. J., Timmerman L. A., Nolan G. P., Admon A., Crabtree G. R. (1994) Nature 369, 497–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Falvo J. V., Lin C. H., Tsytsykova A. V., Hwang P. K., Thanos D., Goldfeld A. E., Maniatis T. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 19637–19642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hogan P. G., Chen L., Nardone J., Rao A. (2003) Genes Dev. 17, 2205–2232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu C., Rao K., Xiong H., Gagnidze K., Li F., Horvath C., Plevy S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 39372–39382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rao A., Luo C., Hogan P. G. (1997) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15, 707–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Macian F. (2005) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5, 472–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cockerill P. N., Bert A. G., Jenkins F., Ryan G. R., Shannon M. F., Vadas M. A. (1995) Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 2071–2079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jain J., McCaffrey P. G., Miner Z., Kerppola T. K., Lambert J. N., Verdine G. L., Curran T., Rao A. (1993) Nature 365, 352–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jain J., McCaffrey P. G., Valge-Archer V. E., Rao A. (1992) Nature 356, 801–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kawana M., Lee M. E., Quertermous E. E., Quertermous T. (1995) Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 4225–4231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tasaka K., Kitazumi K. (1994) Gen. Pharmacol. 25, 1059–1069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hasler U., Jeon U. S., Kim J. A., Mordasini D., Kwon H. M., Féraille E., Martin P. Y. (2006) J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 17, 1521–1531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ge Y., Ahn D., Stricklett P. K., Hughes A. K., Yanagisawa M., Verbalis J. G., Kohan D. E. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 288, F912–F920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ge Y., Bagnall A., Stricklett P. K., Strait K., Webb D. J., Kotelevtsev Y., Kohan D. E. (2006) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 291, F1274–F1280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ge Y., Stricklett P. K., Hughes A. K., Yanagisawa M., Kohan D. E. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 289, F692–F698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]