Summary

Background

Among the 40 million people with epilepsy worldwide, 80% reside in low-income regions where human and technological resources for care are extremely limited. Qualitative and experiential reports indicate that people with epilepsy in Africa are also disadvantaged socially and economically, but few quantitative systematic data are available. We sought to assess the social and economic effect of living with epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa.

Methods

We did a cross-sectional study of people with epilepsy concurrently matched for age, sex, and site of care to individuals with a non-stigmatised chronic medical condition. Verbally administered questionnaires provided comparison data for demographic characteristics, education, employment status, housing and environment quality, food security, healthcare use, personal safety, and perceived stigma.

Findings

People with epilepsy had higher mean perceived stigma scores (1·8 vs 0·4; p<0·0001), poorer employment status (p=0·0001), and less education (7·1 vs 9·4 years; p<0·0001) than did the comparison group. People with epilepsy also had less education than their nearest-age same sex sibling (7·1 vs 9·1 years; p<0·0001), whereas the comparison group did not (9·4 vs 9·6 years; p=0·42). Housing and environmental quality were poorer for people with epilepsy, who had little access to water, were unlikely to have electricity in their home (19% vs 51%; p<0·0001), and who had greater food insecurity than did the control group. During pregnancy, women with epilepsy were more likely to deliver at home rather than in a hospital or clinic (40% vs 15%; p=0·0007). Personal safety for people with epilepsy was also more problematic; rape rates were 20% among women with epilepsy vs 3% in the control group (p=0·004).

Interpretation

People with epilepsy in Zambia have substantially poorer social and economic status than do their peers with non-stigmatised chronic medical conditions. Suboptimum housing quality differentially exposes these individuals to the risk of burns and drowning during a seizure. Vulnerability to physical violence is extreme, especially for women with epilepsy.

Introduction

Among neuropsychiatric disorders, epilepsy contributes substantially to the global burden of disease.1 80% of the 40 million people with epilepsy worldwide reside in low-income regions2 where resources for care are extremely limited. In sub-Saharan Africa, although basic diagnostic services, such as neuroimaging and electroencephalography, were available in 70–80% of countries surveyed in 2004,3 such services are located almost exclusively in urban areas, often in association with private hospitals, and are de facto not available to most people with epilepsy.4 The treatment gap (proportion of people with active epilepsy who warrant but who are not receiving treatment) among people with epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa remains at more than 90%,5 despite the affordability of phenobarbital (less than US$10 per person per year). For individuals who do not respond to or who cannot tolerate phenobarbital, second-line drugs are often not available. This enormous treatment gap in the face of at least one reasonably priced drug is likely to be associated with a lack of trained healthcare providers and traditional belief systems that direct care-seeking outside of medical facilities.3,6,7 Adherence to chronic medication use might also be further limited by the reality that for people with seizure disorders, especially in less developed regions, the condition encompasses far more than a simple medical problem requiring tablets. Traditional medical systems in such regions might be more adept at addressing these larger issues even if their treatments fail to improve seizure control.8

Untreated seizures in low-income regions have significant consequences in terms of medical morbidity and mortality. Severe burns, fractures, and other seizure-related traumas occur commonly, especially among individuals with long-standing untreated epilepsy.9 In Tanzania, a follow-up study undertaken in the pre-HIV era showed that over a 30 year period 80% of people with epilepsy who had been receiving treatment at an established clinic died, with around 50% of deaths related to status epilepticus, burns, or drowning.10 The psychosocial and economic consequences of epilepsy in less developed countries are generally acknowledged to contribute substantially to the burden of this highly stigmatised disease.11 People with epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa may have fewer educational, marital, and employment opportunities.12–18 Epilepsy-associated stigma and loss of personhood could even exacerbate the effects of regional famine and food insecurity.19 A cross-cultural review of epilepsy-associated stigma and stigma sequelae lend support to reports of a detrimental effect of epilepsy on health-related quality of life.20

Although qualitative and experiential reports indicate substantial negative social and economic consequences associated with epilepsy in low-income regions,14,21,22 little quantitative systematic research has been done. To assess the social and economic effect of living with epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa, we completed a cross-sectional study of adults with epilepsy in Zambia.

Methods

Participating sites

Four outpatient sites providing epilepsy care as part of their primary and multi-specialty healthcare services were included in this study—two urban, one rural, and one mixed site. The urban sites included the outpatient specialty clinics at the University of Zambia’s University Teaching Hospital in Lusaka and four small free-standing clinics scattered throughout Lusaka associated with Chainama Hills Hospital. Monze Mission Hospital, located on the main tarmac road between Lusaka and Livingstone, serves a mixed peri-urban and rural population in its outpatient department. Chikankata Health Service, located 31 km off the tarmac road 120 km south of Lusaka, operates a busy outpatient department serving a rural population of subsistence farmers. Each site provides care for people with epilepsy as well as for those with a range of medical problems common in the region.

This study was approved by the University of Zambia’s Research Ethics Committee and Michigan State University’s Committee for Research involving Human Subjects. Consent was sought in the potential participants’ preferred language (English, Tonga, Bemba, or Nyanja). The written consent form was provided and was read and discussed orally. Signed consent forms could include a formal signature, an “X”, or a thumbprint based on responder preference.

Procedures

The questionnaire was designed for verbal delivery and included demographic characteristics, use of pregnancy-related healthcare services, and items from previously validated instruments to measure economic status,23–26 personal safety,27,28 and stigma.29 For people with epilepsy, clinical characteristics were assessed. For education, the number of years of formal education attained by the respondent as well as their same sex sibling closest to them in age was assessed to provide an intra-household comparison in addition to the control group. To assess healthcare use, women were asked about their use of prenatal care and the site of delivery for their most recent childbirth. The economic assessment included measures of housing quality, food security, access to water, power source, waste management, and accumulated wealth. A composite score for housing quality was developed on the basis of a ranked and then summed score for three housing features (materials used for walls, floor, and roof). Food security inquiries included four standard questions regarding present food access as well as a question assessing food access during the hunger season (generally February to April before crops are harvestable but when last season’s produce has been consumed). To determine overall household wealth accumulation, a list of commonly owned items was reviewed with the respondent and market values applied. The three-item stigma scale comprises three dichotomous questions in which a positive response is indicative of felt or perceived stigma with an overall possible score ranging from 0 to 3. To assess personal safety we questioned respondents about physical abuse, rape, and transactional sex. Personal safety questions addressing rape were restricted to women since no standard validated questions for male rape in the region could be identified. The question addressing transactional sex did not include reference to cash payment for sex because local piloting indicated that this question was frequently interpreted as referring to commercial sex work (webappendix).

Enrolment and interviews were undertaken at each of the four sites between Sept 1, and Dec 31, 2005. Research staff consisted of local healthcare workers fluent in both English and the applicable local languages (Bemba, Tonga, or Nyanja). All research staff received a week of intensive training together as a group to decrease intersite variability. Potential cases were patients at least 18 years of age who were receiving care for an established diagnosis of epilepsy and who were able to answer questions without assistance from a proxy respondent. At each site, clinical staff registering patients for outpatient visits as well as healthcare workers in the clinic alerted potential participants about the study, their possible eligibility, and where the research office could be found. Potential study participants who presented to the research staff were given further details about participation and eligibility was assessed. For each enrolled case, research staff provided outpatient clinic staff and care providers with the sex and age range needed for a matched control. Inclusion criteria for controls, matched by sex, age (+/−2 years), and site of care included care-seeking for an established chronic condition that was not thought to be associated with stigma (specifically asthma, rheumatic heart disease, hypertension, or diabetes mellitus). Patients who had AIDS or HIV-related problems, tuberculosis, or sexually transmitted diseases and those with a history of prior epilepsy were excluded. Potential controls identified by clinic staff and healthcare providers were referred for screening. Clinical staff notified each potential control about the study until a qualifying control presented to the research team, consented, and completed the enrolment interview. Study participants were given K5000 (around US$1) for participation. Interviewers of the same sex as the study participant read the questionnaire and recorded their responses in a private location without other patients or staff present and no identifying data were collected. If female participants were accompanied by friends or relatives into the interview, the questions about rape and transactional sex were omitted.

Answers to interview questions were recorded on paper copies of the instrument along with study identification numbers. Names were not recorded on the instrument, but clinic staff made note in their outpatient file of who had already been referred to the study team to avoid duplicate interviews. Completed questionnaires were copied and copies stored in the central study office at Chikankata. Original hardcopies were used to double-enter data into Microsoft Access before importation into EPI INFO 3.2.2 for analysis.

Statistical analysis

We did two-tailed comparisons between cases and controls using the student’s t test, the Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test, or the Kruskal-Wallis test when applicable. Since hypertension and diabetes mellitus could represent disorders more likely to occur in wealthier individuals with more access to high-fat processed foods, we repeated the analysis of economic variables excluding these controls.

Role of the funding source

The sponsor of this study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

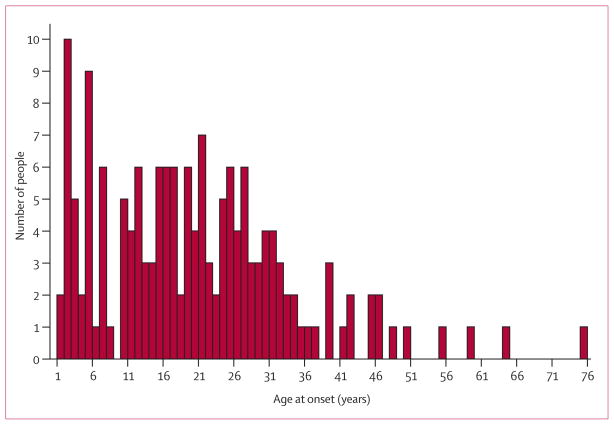

A total of 338 people (47% men) were enrolled and interviewed during the study period (table 1). Chronic medical problems among controls included asthma (37%), diabetes mellitus (28%), hypertension (24%), and rheumatic heart disease (11%). Just over a third of people with epilepsy had evidence of physical stigmata (usually burn scars) as per the interviewers’ assessment (table 2). The mean stigma score for cases was 1·8 versus 0·4 among controls (p<0·0001) and the groups differed significantly in their responses to all three questions (table 3). People with epilepsy were less likely to marry and remain married, had fewer living children, and reported fewer years of formal education than did the control group as well as their nearest age, same-sex sibling (table 1). Notably, the control group did not differ from their siblings in educational attainment. The figure shows the range of ages at which epilepsy developed.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics

| Epilepsy group | Control group | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years (SD) | 35·5 (12·6) | 36·0 (12·7) | 0·75 |

| Marital status | 0·02 | ||

| Missing | 1 (1%) | 2 (1%) | |

| Never | 57 (34%) | 48 (28%) | |

| Monogamous | 47 (28%) | 76 (45%) | |

| Polygamous | 10 (6%) | 12 (7%) | |

| Previously married* | 47 (28%) | 26 (15%) | |

| Remarried | 7 (4%) | 5 (3%) | |

| Mean number of living children (SD) | 2·5 (2·4) | 3·4 (3·0) | 0·02 |

| Mean number of dead children (SD) | 1·2 (1·1) | 2·8 (1·7) | 0·79 |

| Mean number of adults in household (SD) | 3·7 (1·9) | 4·1 (2·2) | 0·07 |

| Mean number of children in household (SD) | 3·3 (2·4) | 3·5 (2·5) | 0·47 |

| Mean education, years (SD) | |||

| For self | 7·1 (3·1) | 9·4 (2·8) | <0·0001 |

| For same sex sibling | 9·1 (3·0) | 9·6 (2·9) | <0·0001† |

Data are mean (SD) or number (%).

Divorced, widowed, or separated and not remarried.

p=0·42 for educational difference for respondents and their siblings for cases and controls.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics among people with epilepsy (n=169)

| Number (%) | |

|---|---|

| Physical stigmata of epilepsy present* | 63 (37%) |

| Median age epilepsy developed, years (IQR)† | 6 (10–28) |

| Experiences generalised tonic-clonic seizures | 81 (48%) |

| Seizure frequency | |

| <1 per month | 77 (46%) |

| 1–3 per month | 60 (36%) |

| 1 per week | 11 (7%) |

| >1 per week | 20 (12%) |

| Experiences an aura | 136 (80%) |

| Reports a history of seizure-related injury | 67 (40%) |

| Disclosure status (Do people in your community know you have epilepsy?) | |

| Yes, because I told them | 8 (5%) |

| Yes, because others told them or they saw me have a seizure | 147 (87%) |

| No | 14 (8%) |

Data are number (%) unless otherwise specified.

Interviewer assessment.

See the figure for distribution.

Table 3.

Stigma scores on the three-point stigma scale (n=338)

| Epilepsy group | Control group | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Because of my (insert condition)…” | |||

| I feel some people are uncomfortable with me | 105 (62%) | 28 (17%) | <0·0001 |

| I feel some people treat me like an inferior person | 101 (60%) | 17 (10%) | <0·0001 |

| I feel some people would prefer to avoid me | 98 (58%) | 16 (10%) | <0·0001 |

Data are number (%) of “yes” responses.

Figure.

Mean age of onset of epilepsy

People with epilepsy seemed to be relatively underemployed compared with controls (table 4). A similar, non-significant difference was evident in the spouses of people with epilepsy. Housing quality significantly differed between the epilepsy group and the control group and people with epilepsy had poorer access to water with fewer resources than did controls. For those respondents without water in the home, the mean time to walk to the water source was longer for people with epilepsy than for the comparison group. Waste management was also poorer among the epilepsy group with more than 20% lacking any means of human waste management compared with around 6% in the control group. Half the control group had electricity in their home compared with fewer than 20% of people with epilepsy. Consequently, more than 80% of those with epilepsy use wood and charcoal sources for cooking. Accumulated household wealth was lower for the households of people with epilepsy than for the control households (around US$232 vs US$517). Those with epilepsy reported poorer food security on all four immediate measures. Over a quarter of all respondents reported consuming fewer meals during the hunger season and the food deficit was more pronounced among people with epilepsy than controls. Although prenatal care visits did not differ, women with epilepsy were more likely to have home deliveries than were controls.

Table 4.

Economic comparisons (n=338)

| Epilepsy group | Control group | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Job classification | 0·0001 | ||

| Missing | 17 (10%) | 8 (5%) | |

| Professional | 1 (1%) | 7 (4%) | |

| Skilled | 8 (5%) | 27 (16%) | |

| Lower skilled | 20 (12%) | 30 (18%) | |

| Unskilled | 123 (73%) | 94 (56%) | |

| Not previously employed | 0 | 3 (2%) | |

| Spouse’s job classification | 0·09 | ||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | |

| Professional | 3 (2%) | 11 (7%) | |

| Skilled | 14 (8%) | 29 (17%) | |

| Lower skilled | 13 (8%) | 25 (15%) | |

| Unskilled | 139 (82%) | 104 (62%) | |

| Not previously employed | 0 | 0 | |

| Mean housing quality score (SD) | 6·6 (3·2) | 8·2 (3·0) | <0·0001 |

| Water source | <0·0001 | ||

| Running in home | 22 (13%) | 71 (42%) | |

| Pump | 53 (31%) | 40 (24%) | |

| Tap | 52 (31%) | 39 (23%) | |

| Well | 21 (12%) | 9 (5%) | |

| Stream/river | 21 (12%) | 10 (6%) | |

| Mean travel time to water if not in dwelling, min (SD) | 10·6 (14·1) | 6·1 (11·7) | <0·0001 |

| Waste management | <0·0001 | ||

| Missing | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Toilet in dwelling | 25 (15%) | 65 (39%) | |

| Toilet nearby | 13 (8%) | 8 (5%) | |

| Pit latrine | 96 (57%) | 85 (50%) | |

| Bush | 34 (20%) | 10 (6%) | |

| Electricity in dwelling | 32 (19%) | 86 (51%) | <0·0001 |

| Cooking source | <0·0001 | ||

| Missing | 0 | 1 (1%) | |

| Electric stove | 29 (17%) | 79 (47%) | |

| Wood | 85 (50%) | 59 (35%) | |

| Charcoal | 55 (33%) | 30 (18%) | |

| Wealth (mean kwacha) | 814 273 (US$232) | 1 811 142 (US$517) | <0·0001 |

| Healthcare use* | |||

| Prenatal care | 68 (91%) | 76 (97%) | 0·07 |

| Home delivery | 30 (40%) | 12 (15%) | 0·0007 |

| Food security | |||

| Eats two or more meals per day | 96 (57%) | 167 (99%) | <0·0001 |

| Skipped meals in past week | 114 (68%) | 84 (50%) | 0·0001 |

| ≥1 day without food in past week | 94 (56%) | 56 (33%) | 0·008 |

| Number of meat, poultry, or fish meals per month | 21 (12%) | 33 (20%) | <0·0001 |

| Fewer meals in hunger season | 58 (34%) | 33 (20%) | 0·002 |

Data are number (%) or mean (SD).

Applicable population of women who had had at least one child (n=75 in epilepsy group, n=78 in control group).

People with epilepsy reported higher rates of physical abuse from members of their households (37% vs 15%, p≤0·0001) and more than 20% of women with epilepsy reported a history of rape compared with around 3% of controls (table 5). Reported rates of transactional sex for survival goods did not differ (49% vs 53%, p=0·05).

Table 5.

Personal safety characteristics

| Epilepsy group | Control group | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abuse (n=338) | <0·0001 | ||

| Missing | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | |

| Never | 104 (62%) | 141 (83%) | |

| Sometimes | 47 (28%) | 24 (14%) | |

| Often | 16 (10%) | 2 (1%) | |

| Rape (n=176)* | 0·004 | ||

| Missing | 0 | 1 (1%) | |

| Never | 70 (80%) | 84 (96%) | |

| Sometimes | 17 (19%) | 3 (3%) | |

| Often | 1 (1%) | 0 | |

| Transactional sex (n=176) | 0·05 | ||

| Missing | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Never | 44 (50%) | 41 (47%) | |

| Sometimes | 37 (42%) | 45 (51%) | |

| Often | 6 (7%) | 1 (1%) |

Data are number (%).

Women only.

Note that all women attended the interview alone and therefore the rape and transactional sex questions were asked of all 176.

In the sensitivity analysis, which excluded people with diabetes mellitus or hypertension, only the number of meals skipped in the past week and the finding of worsening food insecurity during the hunger season lost statistical significance, although the trend remained the same (webtable).

Discussion

The findings of this study lend support to the long-held supposition that people with epilepsy in developing regions carry a heavy burden of stigma with associated poor social and economic status. This cross-sectional study matched individuals by age, sex, and site of care and allowed us to assess the differential burden of epilepsy relative to non-stigmatised, chronic, health conditions. Future work to investigate epilepsy stigma versus other disease stigma is needed.

Since many people with epilepsy in Zambia do not seek medical care, the cases might not be representative of the general population of people with epilepsy in the region. Furthermore, because of confidentiality concerns for people seeking epilepsy care, we do not know the proportion or characteristics of eligible people alerted to the study who chose not to inquire about participation. Although recruitment estimates based on the numbers of people seeking epilepsy care in the past at each clinic suggest that most people chose to participate, the study population is a self-selected group. Finally, in this cross-sectional design, we cannot determine the temporal relation between low socioeconomic status and epilepsy. Certain poverty related exposures described here, such as poor antenatal care and waste management, could predispose people to epilepsy through birth-related CNS injury or parasitic infections such as neurocysticercosis. Studies in high-income countries have shown higher rates of epilepsy in economically deprived populations.30,31

Although we categorised water and power source among the economic variables, people with uncontrolled seizures who obtain water from open bodies of water and cook over open fires actually have a high risk to personal safety. This finding illustrates even further the devastating positive-feedback loop between poverty and epilepsy-related morbidity and mortality among people in sub-Saharan Africa. This is further evident among women with epilepsy who, despite being at risk of seizures and anticonvulsant-related haemorrhage,32 are more likely to deliver at home where vitamin K supplementation and adequate seizure management are unlikely to be available.

The high prevalence of rape experienced by women with epilepsy in our study is of particular concern. In prior focus group discussions, women with epilepsy reported feeling very vulnerable to rape since many had been abandoned by their husbands or their male relative typically charged with their “protection”. As such, they felt that any man who found them alone could assault them without consequences—which would usually entail a male relative seeking financial retribution through traditional leaders or the legal system. The potential fatal consequences of rape in this population with HIV rates of 25–29% among people aged 15–49 years33 add a dimension to the burden associated with being a person with epilepsy in this environment that has not previously been considered. We are not aware of comparable data for women with other stigmatised disorders, but this certainly deserves further consideration and study. Unfortunately, valid quantitative assessments of emotional abuse and male rape in Zambia were not possible with existing methods34 and we did not attempt to quantify these outcomes in this study.

WHO defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”. Clearly, people with epilepsy in Zambia are faced with multiple social and economic challenges that negatively affect their capacity for health. Strategies to improve the well-being of people with epilepsy in the region need to be multi-modal in nature, addressing stigma-mediated disadvantage through education and advocacy of influential groups (those with the social and economic power), promoting empowerment among people with epilepsy, expanding opportunities for education and employment, improving housing and environmental quality, and decreasing violence towards women.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH NS48060 and NS46086. G Birbeck also received support as a Charles E Culpeper Medical Scholar through the Goldman Philanthropic Partnerships during this work. We thank Michelle Powell for her leading role in training interviewers, Jamey Hardesty for his assistance in data management, and Kennedy Malama of Monze Mission Hospital for his supervision and administrative support.

Footnotes

Contributors

GB, EC, MA, and AH participated in the conceptualisation of the research. GB, EC, MA, EM, and AH participated in instrument development, provided input into the analytical plan, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. GB, EC, EM, and AH directed enrolment of study participants.

Conflicts of interest

We have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Gretchen Birbeck, Michigan State University’s International Neurologic and Psychiatric Epidemiology Program, East Lansing, MI, USA.

Elwyn Chomba, Department of Pediatrics and Child Health, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia.

Masharip Atadzhanov, UNZA, Department of Medicine, Lusaka, Zambia.

Edward Mbewe, Chainama Hills Hospital, Lusaka, Zambia.

Alan Haworth, University of Zambia, Department of Psychiatry and Chainama Hills Hospital, Lusaka, Zambia.

References

- 1.Eisenberg L. Global burden of disease. Lancet. 1997;350:143. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61848-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leonardi M, Ustun TB. The global burden of epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2002;43 (suppl 6):21–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.43.s.6.11.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO, IBE, ILAE. Atlas: epilepsy care in the world, 2005. Geneva: WHO; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birbeck GL, Munsat T. Neurologic services in Sub-Saharan Africa: a case study among Zambian primary healthcare workers. J Neurol Sci. 2002;200:75–78. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(02)00132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyer A, Birbeck G. Determinants of the epilepsy treatment gap in developing countries. Neurology. 2006;66 (5 suppl 2):A343. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diop AG, de Boer HM, Mandlhate C, Prilipko L, Meinardi H. The global campaign against epilepsy in Africa. Acta Trop. 2003;87:149–59. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(03)00038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chomba E, Haworth A, Atadzhanov M, Mbewe E, Birbeck G. Zambian healthcare workers’ knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and practices regarding epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.phyletb.2003.10.071. published online Oct 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baskind R, Birbeck G. Epilepsy care in Zambia: a study of traditional healers. Epilepsia. 2005;46:1121–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.03505.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birbeck GL. Seizures in rural Zambia. Epilepsia. 2000;41:277–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jilek-Aall L, Rwiza HT. Prognosis of epilepsy in a rural African community: a 30-year follow-up of 164 patients in an outpatient clinic in rural Tanzania. Epilepsia. 1992;33:645–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1992.tb02341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amoroso C, Zwi A, Somerville E, Grove N. Epilepsy and stigma. Lancet. 2006;367:1143–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68503-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Birbeck G, Chomba E, Atadzhanov M, Mbewe E, Haworth A. Zambian teachers-What do they know about epilepsy and how can we work with them to decrease stigma? Epilepsy Behav. 2006;9:275–80. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atadzhanov M, Chomba E, Haworth A, Mwewe E, Birbeck G. Knowledge, attitudes, behaviors and practices (KABP) regarding epilepsy among Zambian clerics. EpilepsyBehav. 2006;9:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baskind R, Birbeck GL. Epilepsy-associated stigma in sub-Saharan Africa: the social landscape of a disease. Epilepsy Behav. 2005;7:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.IOM. Neurological, psychiatric, and developmental disorders: meeting the challenge in the developing world. 1. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jilek-Aall L, Jilek M, Kaaya J, Mkombachepa L, Hillary K. Psychosocial study of epilepsy in Africa. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:783–95. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00414-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matuja WB, Rwiza HT. Knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) towards epilepsy in secondary school students in Tanzania. Cent Afr J Med. 1994;40:13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ndour D, Diop AG, Ndiaye M, Niang C, Sarr MM, Ndiaye IP. A survey of school teachers’ knowledge and behaviour about epilepsy, in a developing country such as Senegal. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2004;160:338–41. doi: 10.1016/s0035-3787(04)70909-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Birbeck GL, Kalichi EM. Famine-associated AED toxicity in rural Zambia. Epilepsia. 2003;44:1127. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.22403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacoby A, Snape D, Baker GA. Epilepsy and social identity: the stigma of a chronic neurological disorder. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:171–78. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)01014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernet-Bernady P, Tabo A, Druet-Cabanac M, et al. Epilepsy and its impact in northwest region of the Central African Republic. Med Trop. 1997;57:407–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jilek WG, Jilek-Aall LM. The problem of epilepsy in a rural Tanzanian tribe. Afr J Med Sci. 1970;1:305–07. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamano T, Jayne T. Measuring the impact of working age adult mortality in Kenya. World Development. 2004;31:91–119. [Google Scholar]

- 24.UNECA/SSD. Building food security and policy information portals for Africa. Symposium of the African Agricultural Association of Agricultural Economists; Nairobi, Kenya. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO. Health in sustainable developing planning. Geneva: WHO; 2002. Issue-specific indicators: housing and settlements; pp. 121–35. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benincio M, Ferriera M, Cardosa M, Konno S, Montiero C. Wheezing conditions in early childhoof: prevalence an risk factors in the city of São Paolo, Brazil. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:516–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.WHO. Sexual violence: global report on violence and health. Geneva: WHO; 2004. pp. 148–81. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jewkes R, Penn-Kekana L, Levin J, Ratsaka M, Schrieber M. Prevalence of emotional, physical and sexual abuse of women in three South African provinces. S Afr Med J. 2001;91:421–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacoby A. Felt versus enacted stigma: a concept revisited. Evidence from a study of people with epilepsy in remission. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:269–74. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90396-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hesdorffer DC, Tian H, Anand K, et al. Socioeconomic status is a risk factor for epilepsy in Icelandic adults but not in children. Epilepsia. 2005;46:1297–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.10705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heaney DC, MacDonald BK, Everitt A, et al. Socioeconomic variation in incidence of epilepsy: prospective community based study in south east England. BMJ. 2002;325:1013–16. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7371.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pennell PB. Pregnancy in the woman with epilepsy: maternal and fetal outcomes. Semin Neurol. 2002;22:299–308. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-36649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sandoy IF, Kvale G, Michelo C, Fylkesnes K. Antenatal clinic-based HIV prevalence in Zambia: declining trends but sharp local contrasts in young women. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11:917–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization. Global report on violence and health. Geneva: WHO; 2004. [Google Scholar]