Abstract

Background

Mechanisms promoting the transition from hypertensive heart disease (HHD) to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) are poorly understood. When inappropriate for salt status, mineralocorticoid (deoxycorticosterone acetate, DOCA) excess causes hypertrophy, fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction. As cardiac mineralocorticoid receptors (MR) are protected from mineralocorticoid binding by the absence of 11-ß hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, salt-mineralocorticoid induced inflammation is postulated to cause oxidative stress and mediate cardiac effects. While previous studies have focused on salt/nephrectomy in accelerating mineralocorticoid induced cardiac effects, we hypothesized that HHD is associated with oxidative stress and sensitizes the heart to mineralocorticoid, accelerating hypertrophy, fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction.

Methods and Results

Cardiac structure and function, oxidative stress and MR-dependent gene transcription were measured in SHAM operated and transverse aortic constriction (TAC; studied two weeks later) mice without and with DOCA administration, all in the setting of normal salt diet. Compared to SHAM mice, SHAM+DOCA mice had mild hypertrophy without fibrosis or diastolic dysfunction. TAC mice displayed compensated HHD with hypertrophy, increased oxidative stress (osteopontin and NOX4 gene expression) and normal systolic function, filling pressures and diastolic stiffness. Compared to TAC mice, TAC+DOCA mice had similar LV systolic pressure and fractional shortening but more hypertrophy, fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction with increased lung weights consistent with HFpEF. There was progressive activation of markers of oxidative stress across the groups but no evidence of classic MR-dependent gene transcription.

Conclusions

Pressure overload hypertrophy sensitizes the heart to mineralocorticoid excess which promotes the transition to HFpEF independent of classic MR-dependent gene transcription.

Keywords: Deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA); Pressure overload hypertrophy; Mineralocorticoid; Stress,oxidative; Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

BACKGROUND

Heart failure (HF) with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) comprises nearly 50% of HF and as yet, no effective therapy exists1. Hypertensive heart disease is a prominent risk factor for HFpEF but the mechanisms which contribute to the transition from compensated hypertensive heart disease to HFpEF are poorly understood2.

Aldosterone levels are associated with increased mortality in HFpEF3 and with incident hypertension in the population4. Mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) antagonists regressed hypertrophy, fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction in human and experimental hypertensive heart disease5–7. However, whether aldosterone itself causes adverse cardiac remodeling which could promote the transition from compensated hypertensive heart disease to HFpEF has been questioned8, 9.

The heart contains abundant MR but is not considered a mineralocorticoid target as it lacks significant amounts of 11-ß hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type II (11β-HSD2), an enzyme which confers aldosterone specificity in renal epithelial cells, vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells and circulating inflammatory cells10–13. Indeed, marked transient endogenous activation of aldosterone associated with volume depletion or chronic exogenous mineralocorticoid excess with salt deprivation to mimic volume depletion does not produce adverse cardiac remodeling 14, 15. However, exogenous excess mineralocorticoid (deoxycorticosteroid acetate (DOCA) or aldosterone) does induce cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction when inappropriate for salt intake, i.e. in the absence of salt deprivation. Above normal salt intake and unilateral nephrectomy (DOCA-Salt model) accelerate DOCA-induced cardiac effects 14, 15. From these observations, some have concluded that mineralocorticoid occupancy and activation of cardiac MR occurs in the DOCA-Salt model and human HF despite the lack of 11β-HSD2 13, 16, 17. Alternatively, it has been proposed that adverse cardiac remodeling in mineralocorticoid excess (inappropriate for salt status) is mediated not by mineralocorticoid binding to cardiac MR but by synergistic effects of sodium and mineralocorticoid on non-cardiomyocyte mineralocorticoid target (11β-HSD2 containing) tissues and that these non-cardiomyocyte effects ultimately increase myocardial oxidative stress 9, 10, 18,19. Oxidative stress is known to initiate multiple adverse signaling pathways and may lead directly to myocyte necrosis and fibrosis19 and/or may activate glucocorticoid-bound cardiac MR via redox sensitive corepressors 18, 20, 21.

While previous studies have focused on a pivotal role for increased salt/nephrectomy in accelerating mineralocorticoid induced cardiac effects, we hypothesized that hypertensive heart disease is associated with oxidative stress and thus, sensitizes the heart to mineralocorticoid, accelerating the development of hypertrophy, fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction. Further, we sought to determine if oxidative stress and/or mineralocorticoid excess in hypertensive heart disease are associated with classic genomic MR actions signified by serum-and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase-1 (SGK1) and sodium hydrogen exchanger (NHE-1) gene transcription in cardiac tissue. Accordingly, cardiac structure and function, markers of myocardial oxidative stress and MR-dependent gene transcription in the heart were measured in normal mice without or with exogenous mineralocorticoid (DOCA), in mice with hypertensive heart disease associated with endogenous aldosterone activation (transverse aortic constriction, TAC) and in TAC mice with exogenous mineralocorticoid (DOCA) administration, all in the setting of normal salt diet.

METHODS

All experimental procedures were designed in accordance with the National Institute of Health guidelines and approved by Mayo Foundation Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Minimally invasive transverse aortic constriction (TAC)

Eight week old male FVB/NJ mice (Jackson laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were subjected to minimally invasive TAC, wherein a ligature was placed in the arch of the aorta between the brachiocephalic trunk and left common carotid artery as previously described by Hu et al 22. Control mice underwent identical procedure without placement of a suture (SHAM).

SHAM (n=10) or TAC (n=25) mice assigned to DOCA underwent subcutaneous implantation of extended release deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA) pellets (2.4 mg/day; Innovative research of America, Sarasota, FL) immediately following TAC/sham procedure. SHAM (n=24) or TAC (n=27) mice not assigned to DOCA had no pellet placed. All mice were fed a normal salt diet (Rodent chow containing 0.3% sodium). Mice were studied two weeks after surgery.

A separate group (n=21) of normal mice underwent SHAM (n=9) or DOCA pellet (n=12) implantation (normal salt diet) with blood pressure (BP) measured daily by tail cuff method and averaged over the third week after surgery. These 21 mice were used solely for BP measurement and were not included in any other analyses.

Echocardiography

Mice (n=82, 95% of the first group of 86 mice) underwent 2-dimensional guided M-mode echocardiography (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) with a 13 MHz probe under light isoflurane anesthesia (0.5–1.0%) administered via nose cone. Digital images were analyzed off-line by EchoPAC software allowing anatomic M-mode measurements. Proximal descending aortic flow velocity (distal to constriction in TAC mice) was measured by pulse wave Doppler. Endocardial fractional shortening (FS) and LV mass were measured by standard formulae and mid-wall fractional shortening (mFS) was calculated by the ellipsoidal two shell method by Shimizu et al23, 24.

Echocardiographic images on 4 mice were suboptimal for quantitative measurement, and thus were not included in the analysis.

Hemodynamic Analysis

Immediately following echocardiography, isoflurane anesthetized mice were intubated and mechanically ventilated (Hugo Sachs Elektronik, Hugstetten, Germany). A conductance catheter (Millar instruments, Houston, TX) was inserted into the LV via the right carotid artery.

Data were acquired at steady states as well as during acute inferior vena caval (IVC) occlusions (variable loading conditions). Data analysis was performed by PVAN software (ADInstruments, Inc, Colorado Springs, CO). The end-systolic (ESPVR) and end-diastolic (EDPVR) pressure-volume relationships during IVC occlusions were used to calculate end-systolic (Ees) and end-diastolic stiffness (slope of linear fit of EDPVR). The LV pressure and echo measurements were used to calculate end-systolic wall stress as previously described25. Catheterization was attempted in all mice (n=86) and successful in 58 (67%).

Tissue and blood harvest

Following catheterization, blood was collected; organs weighed then flash frozen in liquid nitrogen with one left ventricular (LV) section preserved in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin and cross sectioned into 5μm sections.

Plasma aldosterone level was measured by RIA as previously described26.

Gene expression (Quantitative RT Real-Time PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from snap frozen LV tissue. RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA by an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad laboratories, Hercules, CA). cDNA was amplified and levels of gene expression were quantified by real-time quantitative PCR (TaqManR Gene Expression Assays and Universal Probelibrary Gene Assays). Primers for the following mRNAs were used: ANP, collagen I, collagen III (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN), osteopontin, NADPH oxidase subunit 2 (NOX2; gp91phox), NADPH oxidase subunit 4 (NOX4), p22phox, serum-and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase-1 (SGK1), sodium hydrogen exchanger-1 (NHE-1) and elongation factor RNA polymerase II (ELL), (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Histology and histomorphometry

LV sections were stained with picrosirius red. Peri-vascular and interstitial fibrosis were assessed independently by two blinded experienced observers by a semi-quantitative visual analogue fibrosis with 4 grades: 1–3 (1= No fibrosis, 2= Mild, 3=Moderate and 4= Severe fibrosis). Representative examples from previous studies showing each grade of fibrosis were used to enhance consistency of scoring between observers. Fibrosis analysis was performed in 77 (90%) of studied mice. Tissue slides for 9 mice were missing or un-interpretable, and thus were not included in the analysis.

Capillary density

LV sections were stained with biotinylated isolectin subunit 4 (1:100 dilution) and detected by peroxidase (Vector laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Capillary density was evaluated by a computer-assisted histomorphometry (Zeiss Vision, Hallbergmoos, Germany) and expressed as a percent of LV area in 32 (37%) of the studied mice.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. While most parameters appeared normally distributed, a few were not. Therefore, comparison between TAC and SHAM groups was by the Wilcoxon (Rank Sums) test with a 2-tailed alpha of 0.05. Comparison across all groups was performed by Kruskal Wallis test, followed by Wilcoxon (Rank Sums) test comparing SHAM vs SHAM+DOCA and TAC vs TAC+DOCA or test for linear trend between physiologic parameters and group (treated as an ordinal variable in the following order: SHAM, SHAM+DOCA, TAC, TAC+DOCA as physiologically appropriate, consistent with the magnitude and interaction of mineralocorticoid activation and pressure overload). The p-value for the linear trend was calculated based on Spearman’s rank correlation. The figures are displayed as Tukey (outlier) box plots where the whiskers extend to a length equal to 1.5 times the interquartile range or to the most extreme value if it falls within this boundary. Values that are above or below the whiskers are drawn as individual points.

RESULTS

Transverse aortic constriction (TAC): As compared to SHAM operated mice, TAC mice displayed expected findings of chronic pressure overload with higher maximum LV pressure and increased post-constriction flow velocity (Table 1). TAC mice displayed concentric hypertrophy (assessed by echo, autopsy heart and LV weights and LV ANP gene expression), which normalized wall stress. Cardiac fibrosis was increased (significant increases in picrosirius staining and increases in collagen I gene expression). The increase in collagen III gene expression was marginally significant (p=0.055).

Table 1.

Hypertensive Heart Disease due to Transverse Aortic Constriction

| SHAM | TAC | |

|---|---|---|

| Load | ||

| Maximum LV pressure (mmHg) | 80 ± 13 | 123± 36* |

| Aortic velocity (m/sec) | 0.6± 0.23 | 2.5± 0.94* |

| End-systolic wall stress (g/cm2) | 74± 20 | 80± 32 |

| LV Structure and Function | ||

| LV diastolic dimension (mm) | 3.7± 0.29 | 3.7± 0.23 |

| Relative wall thickness | 0.32± 0.07 | 0.44± 0.13* |

| Heart/body weight (mg/g) | 4± 0.29 | 5.1± 0.84* |

| LV/body weight (mg/g) | 2.6± 0.19 | 3.5± 0.66* |

| LV ANP gene expression (fold/SHAM) | 1.0± 0.84 | 11.5± 8.34* |

| Endocardial fractional shortening (%) | 32± 6 | 36± 5* |

| Midwall fractional shortening (%) | 16± 2.55 | 17± 2.13 |

| End-systolic elastance (mmHg/ul) | 1.4± 0.55 | 2.0± 0.93 |

| LV end-diastolic pressure (mmHg) | 11± 8.49 | 11± 9.22 |

| LV diastolic stiffness (mmHg/ul) | 0.17± 0.08 | 0.23± 0.12 |

| Lung/body weight (mg/g) | 6.2± 1.45 | 6.9±2.08 |

| Interstitial fibrosis grade | 1.9± 0.58 | 2.8± 0.67* |

| Perivascular fibrosis grade | 1±0.0 | 2± 0.9* |

| Collagen I gene expression (fold/SHAM) | 1.0± 0.38 | 3.8± 3 |

| Collagen III gene expression (fold/SHAM) | 1.0± 0.41 | 3.8± 3 |

| Vascularity (%) | 7.7± 1.1 | 5.8± 2.81 |

| Oxidative stress/inflammation | ||

| Osteopontin gene expression (fold/SHAM) | 1.0± 0.66 | 10.6± 10.55* |

| p22phox gene expression (fold/SHAM) | 1.0± 0.32 | 1.6± 0.95 |

| NOX2 gene expression (fold/SHAM) | 1.0± 0.39 | 2.2± 2.08 |

| NOX4 gene expression (fold/SHAM) | 1.0± 0.86 | 4.9± 2.95* |

| MR Signaling | ||

| Aldosterone (ng/dl) | 66± 30.12 | 109± 52.61* |

| SGK1 gene expression (fold/SHAM) | 1.0± 0.33 | 1.2± 0.38 |

| NHE-1 gene expression (fold/SHAM) | 1.0± 0.11 | 1.1± 0.09 |

| ELL gene expression (fold/SHAM) | 1.0± 0.21 | 1.1± 0.32 |

Mean ± SD

P<0.05 vs SHAM

However, this degree of TAC was well compensated with maintenance of endocardial and mid-wall fractional shortening, diastolic pressure and stiffness and lung weights. TAC was associated with evidence of increased oxidative stress with increased osteopontin and NOX4 gene expression. TAC was also associated with endogenous mineralocorticoid activation with increased serum aldosterone levels, likely secondary to renal hypoperfusion27. However, classic MR-dependent gene transcription, as assessed by LV SGK1 and NHE-1 gene expression, was not increased.

Effect of DOCA on LV load

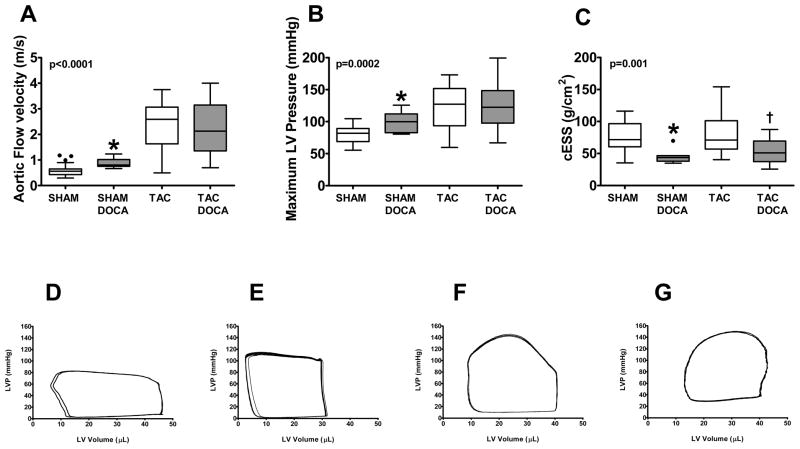

After 2 weeks, systolic BP was similar in mice without (136±3 mmHg) or with (142±3 mmHg) DOCA pellet implantation (p=0.17). However, maximum LV pressure measured at terminal hemodynamic study was slightly but significantly higher in SHAM+DOCA versus SHAM mice (Figure 1). Both the post-constriction flow velocity and maximum LV pressure were similar in TAC and TAC+DOCA mice. In contrast to TAC versus SHAM (Table 1) where wall stress was normalized by compensatory hypertrophy, end systolic wall stress was lower in SHAM+DOCA vs SHAM and in TAC+DOCA vs TAC owing to altered LV geometry, suggesting that hypertrophy was out of proportion to load.

Figure 1. LV Load.

Top panel shows proximal descending aortic flow velocity (A), maximum LV pressure (B) and end-systolic wall stress (cESS) (C) in the four groups. Bottom panel shows representative pressure-volume loops in SHAM (D), SHAM+DOCA (E), TAC (F) and TAC+DOCA (G) mice. * p < 0.05 SHAM+DOCA versus SHAM, † p < 0.05 TAC+DOCA versus TAC

Effect of DOCA on LV structure

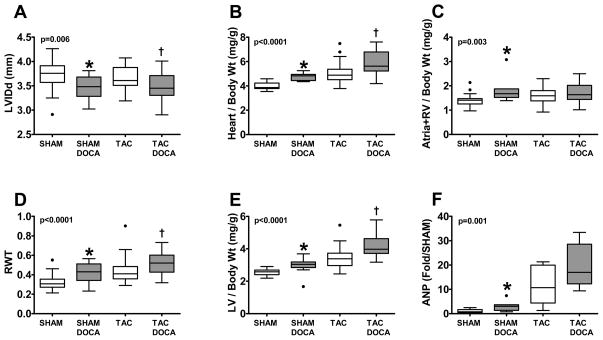

In SHAM mice, DOCA resulted in concentric remodeling with smaller LV dimension and increased relative wall thickness on echocardiographic study (Figure 2). Heart, LV and atria+right ventricular (RV) weights indexed to body weight were significantly increased as compared to SHAM with increased LV ANP gene expression.

Figure 2. LV Remodeling and Geometry.

LV internal diastolic dimension (LVIDd) (A), heart/ body weight (B), atria + right ventricle (RV)/body weight (C), relative wall thickness (RWT) (D), LV/body weight (E) and LV atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) gene expression (F) in the four groups. * p < 0.05 SHAM+DOCA versus SHAM, † p < 0.05 TAC+DOCA versus TAC

Similarly, in TAC mice, DOCA enhanced concentric remodeling with smaller LV dimension. DOCA also increased relative wall thickness, heart and LV weights. LV ANP gene expression was increased but the difference was not statistically significant.

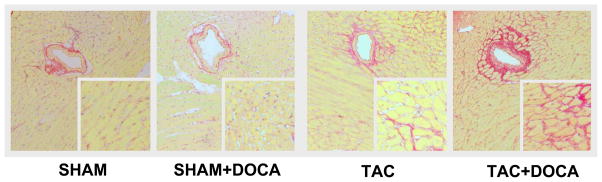

In agreement with previous studies, in SHAM mice, DOCA did not result in LV fibrosis as assessed by picrosirius staining (Figure 3) or LV collagen I or III gene expression. In contrast, in TAC mice, DOCA resulted in increased interstitial fibrosis. Peri-vascular fibrosis and LV collagen I and III gene expression increased but the difference was not statistically significant.

Figure 3. LV Fibrosis.

Top panel shows representative examples of peri-vascular and interstitial fibrosis in each of the four groups. Middle panel shows interstitial (A) and perivascular (B) fibrosis score group data in the four groups (all SHAM mice had no perivalvular fibrosis (score of 1), thus the box plots for this group is in the shape of a line). Bottom panel shows collagen I (D) and collagen III (E) gene expression in the four groups. * p < 0.05 SHAM+DOCA versus SHAM, † p < 0.05 TAC+DOCA versus TAC

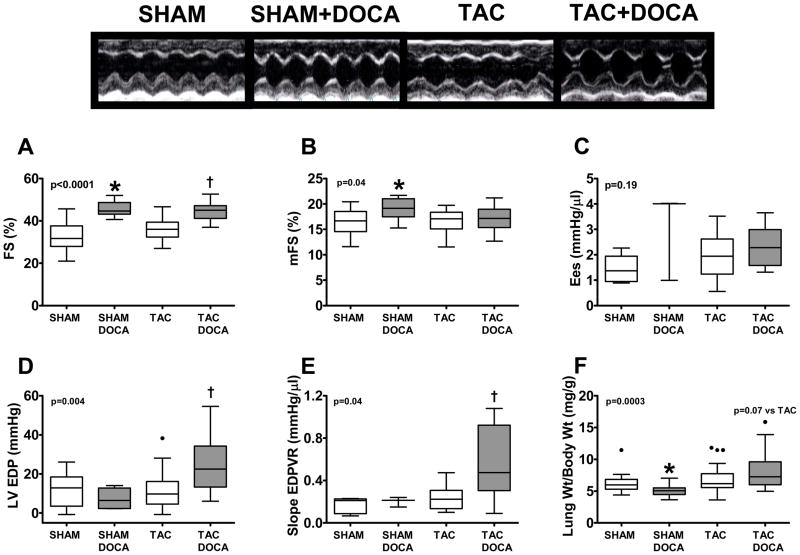

Effect of DOCA on systolic function

As compared to SHAM, SHAM+DOCA mice had higher endocardial and mid-wall fractional shortening as would be expected with lower wall stress but the load independent measure of contractility (end-systolic elastance) was not increased (Figure 4). As compared to TAC mice, TAC+DOCA mice had increased endocardial fractional shortening in association with lower wall stress but midwall fractional shortening and end-systolic elastance were similar to TAC. Thus, with DOCA, there was no evidence of adverse or favorable effects on systolic function independent of the effects of altered geometry on wall stress.

Figure 4. LV Systolic and Diastolic Function.

Top panel shows representative examples of m-mode echocardiograms in each of the four groups. Middle panel shows endocardial fractional shortening (eFS) (A), midwall fiber shortening (mFS)(B), end-systolic elastance (Ees)(C) in the four groups. Bottom panel shows LV end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP)(D), slope of the LV end-diastolic pressure-volume relationship (EDPVR)(E) and lung/body weight (F) in the four groups. * p < 0.05 SHAM+DOCA versus SHAM, †

p < 0.05 TAC+DOCA versus TAC

Effect of DOCA on diastolic function

As compared to SHAM, SHAM+DOCA mice had similar LV end-diastolic pressure, EDPVR slope (LV stiffness) and lung weight (Figures 1D and E and Figure 4). In contrast, as compared to TAC mice, each of these parameters was higher in TAC+DOCA mice (Figures 1F and G and Figure 4).

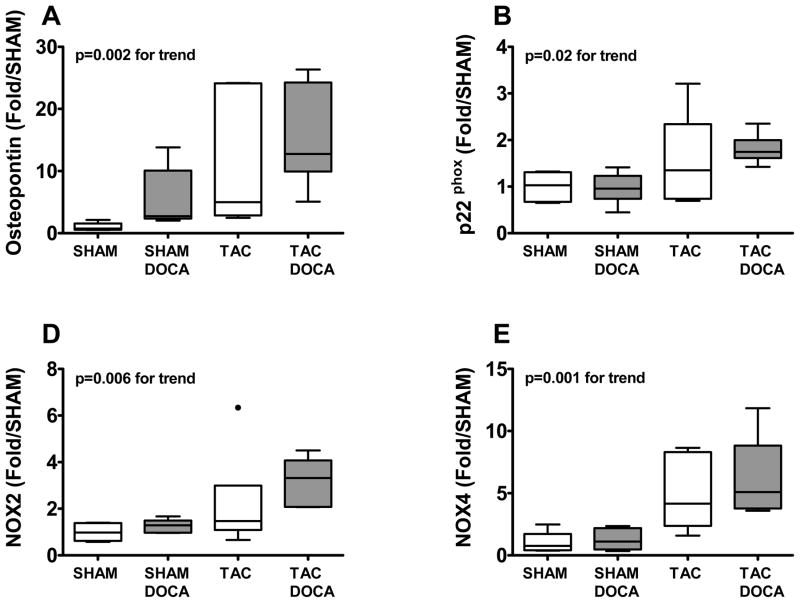

Vascular inflammation and oxidative stress

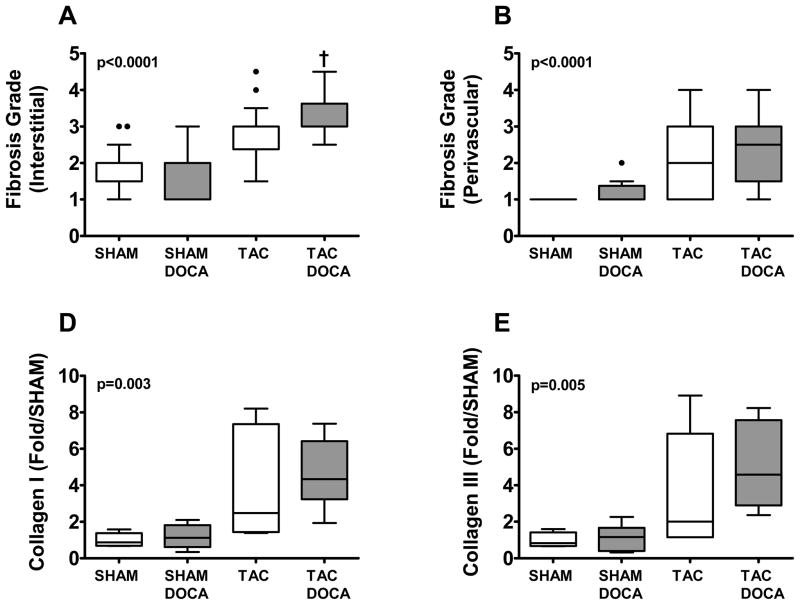

Osteopontin, a matricellular protein activated in the heart in the presence of mechanical, inflammatory or oxidative stress, showed significant progressive increase across SHAM+DOCA, TAC and TAC+DOCA mice (Figure 5). Likewise, markers of oxidative stress, specifically the membrane bound NADH oxidase subunit (p22phox) and the two NADH oxidase catalytic subunit isoforms (NOX2 and NOX4) showed similar progressive increases.

Figure 5. Oxidative stress.

LV gene expression of osteopontin (A), p22phox (B), NOX2 (C) and NOX4 (D) in the four groups.

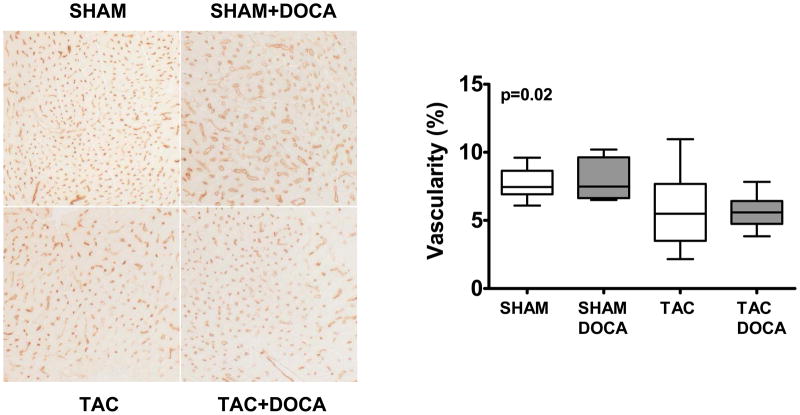

We examined capillary density to determine if DOCA altered angiogenesis or caused vascular rarefaction. While TAC mice tended to have decreased capillary density, this was not altered in TAC+DOCA and DOCA had no effect on capillary density in SHAM mice (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Vascular rarefaction.

Left panel shows representative examples of Lectin-D staining of LV myocardium showing microvascularture in each of the four groups. Right panel shows the percent of Lectin-D staining in the four groups.

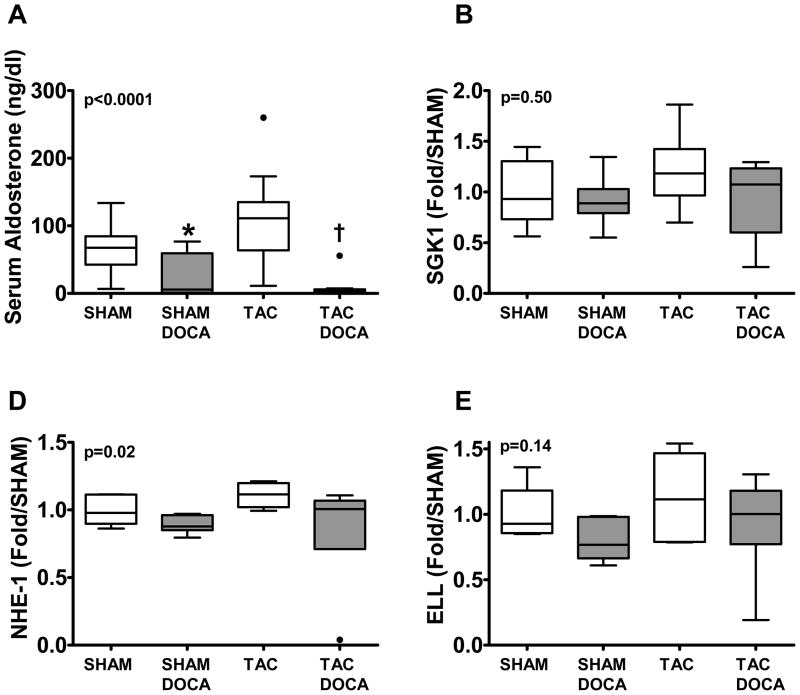

Classic mineralocorticoid receptor-dependent gene expression

Aldosterone levels were lower in both DOCA treated groups as compared to their respective controls, indicating expected negative feedback suppression of endogenous aldosterone production. However, neither SGK1 nor NHE-1 gene expression were increased in TAC (Table 1) as compared to SHAM nor in DOCA treated SHAM or TAC mice as compared to their respective controls (Figure 7). Further, there was no enhanced expression of a co-activator (ELL) thought to enhance MR responsiveness to mineralocorticoid17.

Figure 7. Mineralocorticoid receptor signaling.

Serum aldosterone levels (A) and LV gene expression for SGK1 (B), NHE-1 (C) and ELL (D) are shown in the four groups. * p < 0.05 SHAM+DOCA versus SHAM, † p < 0.05 TAC+DOCA versus TAC

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrate that exogenous mineralocorticoid, inappropriate for salt status, accelerated LV hypertrophy, fibrosis, and diastolic dysfunction in response to chronic pressure overload induced by TAC. Indeed, DOCA treated TAC mice had elevated filling pressures and lung weights with normal systolic indices consistent with HFpEF. In contrast, in the absence of TAC, exogenous mineralocorticoid alone caused mild cardiac hypertrophy without fibrosis or diastolic dysfunction. Exogenous mineralocorticoid, TAC and their combination were associated with progressive activation of markers of inflammation and oxidative stress in cardiac tissue. However, neither endogenous mineralocorticoid activation and oxidative stress evident in TAC nor exogenous mineralocorticoid plus TAC were associated with enhanced classical MR dependent-gene transcription in the heart. These data indicate that in the presence of pressure overload hypertrophy and cardiac oxidative stress, aldosterone may accelerate adverse cardiac remodeling independent of classical genomic MR signaling in the heart. We speculate that pathophysiologically relevant levels of aldosterone may have similar effects over the long term in patients with hypertensive heart disease and accelerate adverse remodeling and progression to HFpEF.

Mineralocorticoid and cardiac remodeling

Despite the proven benefit of MR antagonists in HF and human and experimental hypertension (including TAC7), it remains unclear whether aldosterone itself has direct cardiac effects independent of blood pressure. Purported mechanisms underlying the benefit of MR antagonism in cardiac disease include blockade of glucocorticoid-bound but redox-sensitive cardiac MR activated by the oxidative stress/altered redox status associated with hypertensive heart disease or heart failure (independent of aldosterone)9, 21 and/or blockade of mineralocorticoid activated MR in non-cardiomyocyte, mineralocorticoid target (11β-HSD2 containing) tissues that produce secondary cardiac effects (dependent on aldosterone)19, 28. These alternate hypotheses, while not mutually exclusive, underscore the controversy regarding the role of aldosterone itself in mediating cardiac remodeling in cardiovascular disease.

In the SHAM operated mice, mineralocorticoid excess inappropriate for the normal salt diet did produce mild LV hypertrophy as well as hypertrophy of the atria+RV; effects which occurred in the absence of vascular inflammation or classical MR-dependent gene transcription suggesting either a direct, non-genomic effect on cardiomyocytes or secondary effects from non-cardiac MR stimulation as outlined above. Indeed, the degree of hypertrophy was inappropriate to BP resulting in lower wall stress and increased endocardial and midwall fractional shortening. While previous studies of exogenous mineralocorticoid plus salt deprivation did not demonstrate hypertrophy, animals subjected to salt deprivation had markedly decreased body weight and reduced cardiac load 15. Previous studies have shown rapid but sustained non-genomic mineralocorticoid effects mediated by PKCε or ERK1/2 activation, both known to be involved in hypertrophic pathways29–33. Thus, the current data provide additional in vivo evidence that chronic, inappropriate (for salt status) mineralocorticoid excess results in myocardial effects but in the absence of classical MR-dependent gene transcription in the heart as discussed further below.

Intrinsic myocardial disease sensitizes the heart to mineralocorticoid excess

We previously demonstrated cardiac fibrosis with exogenous mineralocorticoid excess alone in experimental systolic dysfunction34 and increased fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction in renal wrapping induced hypertension35; although DOCA also increased BP in the renal hypertension model. Here we confirm and extend these findings in pressure overload induced produced by TAC, independent of further BP elevation or increased salt intake/nephrectomy and provide insight into the mechanism whereby pressure overload hypertrophy sensitizes the heart to mineralocorticoids.

Cardiac inflammation and oxidative stress with TAC and mineralocorticoid excess

In the current study, we saw evidence of progressive activation of genomic markers of inflammation and oxidative stress across the groups, suggesting that both chronic, inappropriate (for salt status) mineralocorticoid excess and TAC contribute to cardiac inflammation and increased oxidative stress. Aldosterone has been shown to increase osteopontin and/or other inflammatory cytokine production by vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells and peripheral blood mononuclear cells36–38. However, osteopontin is an ubiquitous, pro-inflammatory cytokine which is also activated in response to hemodynamic, inflammatory or oxidative stress and thus, one need not implicate the cardiomyocyte MR in elevating cardiac osteopontin gene expression37.

Vascular tissues contain 11β-HSD2 and some studies have shown a predominance of peri-vascular inflammation in the DOCA-Salt model suggesting that mineralocorticoid inappropriate for salt causes vascular inflammation which could contribute to oxidative stress and adverse cardiac remodeling39. As vascular tissues are susceptible to mineralocorticoid, it has been difficult to reconcile a lack of vascular inflammation or profibrotic effects of appropriate (to salt status) mineralocorticoid excess. Indeed, it may be that aldosterone accelerates the inflammatory response to vascular injury rather than initiating inflammation40. We observed marked peri-vascular fibrosis in TAC and a further trend towards increased peri-vascular fibrosis in TAC mice treated with DOCA. These data suggest that initial vascular injury initiates an inflammatory response which is then accelerated by mineralocorticoid excess. Interestingly, we also saw evidence of vascular rarefaction along with interstitial fibrosis suggesting diffuse vascular injury with TAC. While vascular rarefaction was not significantly enhanced with DOCA, the sensitivity of lectin staining and histomorphometric quantification of vascular density may be inadequate to detect increased vascular rarefaction with DOCA.

Alternatively or additionally, mineralocorticoid stimulation of epithelial MR causes divalent cation excretion and secondary hyperparathyroidism which ultimately promotes calcium overload in cardiomyocytes and peripheral blood mononuclear cells contributing to oxidative stress, cardiomyocyte injury and reparative fibrosis independent of non-genomic or genomic cardiac MR signaling41–44.

Adverse cardiac remodeling with mineralocorticoid excess is not associated with MR-dependent gene transcription in the heart

The importance of rapid and thus, non-genomic mineralocorticoid signaling in a variety of tissues is increasingly apparent 18, 31, 45. In vitro data suggests that these rapid mineralocorticoid effects may be mediated by classic MR in association with activation of PKCε or ERK1/2 or independent of classic MR in a manner associated with enhanced calcium ingress. In the current study, we found no evidence of enhanced transcription of two fairly well established MR-activated genes, SGK1 and NHE-1 with DOCA, TAC or TAC+DOCA8, 46. These data suggest that neither inappropriate mineralocorticoid excess, TAC nor their combination result in classic MR-dependent gene transcription in the LV.

Our findings are consistent with elegant in vitro studies by Grossmann et al, where rapid, non-genomic effects of MR activation on collagen synthesis were observed in cultured cells transfected with full length or truncated MR. Cells transfected with truncated MR constructs were incapable of genomic signaling but displayed intact non-genomic signaling. The truncated MR transfected cells displayed no increased collagen synthesis in the presence of aldosterone alone but increased collagen synthesis with oxidative stress, an effect which was augmented by adding aldosterone to oxidative stress. These in vitro findings are analogous to the fibrosis and collagen gene expression observed with TAC-induced oxidative stress, increased with TAC+DOCA but absent in DOCA+ SHAM groups here and provide in vivo evidence that non-genomic MR signaling enhances cardiac fibrosis associated with pressure overload induced cardiac injury and oxidative stress.

Limitations

We depend on SGK1 and NHE-1 as indicators of cardiac MR genomic signaling. Whether the rather striking diastolic dysfunction observed in the TAC+DOCA mice was mediated by increased hypertrophy and fibrosis, altered calcium handling or other effects is not addressed in the current study. We acknowledge that effects seen with exogenous administration do not necessarily replicate endogenous actions of aldosterone. The tail-cuff method may not accurately characterize blood pressure changes. Further, we can not exclude chronic changes in LV pressure in the DOCA+TAC group though none were apparent at LV catheterization under anesthesia. Anesthesia may also have influenced echocardiographic measurements.

Conclusions

We provide in vivo evidence that pressure overload hypertrophy induces oxidative stress and sensitizes the heart to inappropriate mineralocorticoid excess which promotes hypertrophy, fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction without activation of classic MR-mediated gene transcription. These data suggest that aldosterone may promote the transition from compensated hypertensive heart disease to HFpEF.

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE.

A wealth of data from human systolic heart failure (HF) as well as experimental models of hypertension and HF suggests that mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists reduce mortality, and attenuate hypertrophy, fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction. These data have led to the ongoing multicenter randomized “Trial of Aldosterone Antagonist Therapy in Adults With Preserved Ejection Fraction Congestive Heart Failure (TOPCAT)”.

Although, aldosterone levels are elevated in HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), whether aldosterone itself causes adverse cardiac remodeling which could promote the transition from hypertensive heart disease to overt HFpEF is controversial. In this study we show that oxidative stress is induced in the hypertensive heart and sensitizes the heart to exogenous mineralocorticoids.

In normal mice, exogenous mineralcorticoid had little effect on cardiac structure or function. Mice with pressure overload hypertrophy had increased myocardial oxidative stress and in these mice, exogenous mineralcorticoid accentuated hypertrophy, fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction suggesting an interaction between excess mineralocorticoid (inappropriate for salt status) and oxidative stress. Interestingly, this effect was observed without evidence of classic mineralocorticoid receptor -mediated gene transcription in the heart (“non-genomic” effects) and independent of changes in the magnitude of pressure overload.

These results suggest that aldosterone excess may promote the transition from compensated hypertensive heart disease to HFpEF via nongenomic effects or alternatively through effects on noncardiac cells. As the nongenomic effects of aldosterone are exerted both via the mineralocorticoid receptor as well independent from the mineralocorticoid receptor, development of novel antagonists that target both genomic as well as nongenomic effects may have benefit beyond mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists.

Acknowledgments

We are greatly indebted to Jimmy Storlie, Elise Oehler, Sharon M. Sandberg, Denise M. Heublein and Jilian L. Foxen for their technical expertise.

SOURCES OF FUNDING:

This study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL-76611-1, HL-07111 and HL-63281). This project was also supported by Grant Number 1 UL1 RR024150 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research and also the Japan Research Foundation for Clinical Pharmacology. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

Contributor Information

Selma F. Mohammed, Cardiorenal Research Laboratory, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Tomohito Ohtani, Cardiorenal Research Laboratory, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Josef Korinek, Cardiorenal Research Laboratory, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Carolyn S.P. Lam, Cardiorenal Research Laboratory, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Katarina Larsen, Cardiorenal Research Laboratory, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Robert D. Simari, Cardiorenal Research Laboratory, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Maria L. Valencik, University of Reno, Nevada.

John C. Burnett, Jr, Cardiorenal Research Laboratory, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Margaret M. Redfield, Cardiorenal Research Laboratory, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

References

- 1.Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:251–259. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Redfield MM. Understanding "diastolic" heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1930–1931. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guder G, Bauersachs J, Frantz S, Weismann D, Allolio B, Ertl G, Angermann CE, Stork S. Complementary and incremental mortality risk prediction by cortisol and aldosterone in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2007;115:1754–1761. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.653964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vasan RS, Evans JC, Larson MG, Wilson PW, Meigs JB, Rifai N, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Serum aldosterone and the incidence of hypertension in nonhypertensive persons. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:33–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohtani T, Ohta M, Yamamoto K, Mano T, Sakata Y, Nishio M, Takeda Y, Yoshida J, Miwa T, Okamoto M, Masuyama T, Nonaka Y, Hori M. Elevated cardiac tissue level of aldosterone and mineralocorticoid receptor in diastolic heart failure: Beneficial effects of mineralocorticoid receptor blocker. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R946–954. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00402.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pitt B, Reichek N, Willenbrock R, Zannad F, Phillips RA, Roniker B, Kleiman J, Krause S, Burns D, Williams GH. Effects of eplerenone, enalapril, and eplerenone/enalapril in patients with essential hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy: the 4E-left ventricular hypertrophy study. Circulation. 2003;108:1831–1838. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000091405.00772.6E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuster GM, Kotlyar E, Rude MK, Siwik DA, Liao R, Colucci WS, Sam F. Mineralocorticoid receptor inhibition ameliorates the transition to myocardial failure and decreases oxidative stress and inflammation in mice with chronic pressure overload. Circulation. 2005;111:420–427. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153800.09920.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Connell JM, Davies E. The new biology of aldosterone. J Endocrinol. 2005;186:1–20. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Funder JW. Why are mineralocorticoid receptors so nonselective? Current hypertension reports. 2007;9:112–116. doi: 10.1007/s11906-007-0020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahokas RA, Sun Y, Bhattacharya SK, Gerling IC, Weber KT. Aldosteronism and a proinflammatory vascular phenotype: role of Mg2+, Ca2+, and H2O2 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Circulation. 2005;111:51–57. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000151516.84238.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Funder JW, Pearce PT, Smith R, Smith AI. Mineralocorticoid action: target tissue specificity is enzyme, not receptor, mediated. Science (New York, NY. 1988;242:583–585. doi: 10.1126/science.2845584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arriza JL, Weinberger C, Cerelli G, Glaser TM, Handelin BL, Housman DE, Evans RM. Cloning of human mineralocorticoid receptor complementary DNA: structural and functional kinship with the glucocorticoid receptor. Science (New York, N Y. 1987;237:268–275. doi: 10.1126/science.3037703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lombes M, Alfaidy N, Eugene E, Lessana A, Farman N, Bonvalet JP. Prerequisite for cardiac aldosterone action. Mineralocorticoid receptor and 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase in the human heart. Circulation. 1995;92:175–182. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brilla CG, Weber KT. Mineralocorticoid excess, dietary sodium, and myocardial fibrosis. J Lab Clin Med. 1992;120:893–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brilla CG, Weber KT. Reactive and reparative myocardial fibrosis in arterial hypertension in the rat. Cardiovascular research. 1992;26:671–677. doi: 10.1093/cvr/26.7.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitagawa H, Yanagisawa J, Fuse H, Ogawa S, Yogiashi Y, Okuno A, Nagasawa H, Nakajima T, Matsumoto T, Kato S. Ligand-selective potentiation of rat mineralocorticoid receptor activation function 1 by a CBP-containing histone acetyltransferase complex. Molecular and cellular biology. 2002;22:3698–3706. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.11.3698-3706.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 17.Pascual-Le Tallec L, Lombes M. The mineralocorticoid receptor: a journey exploring its diversity and specificity of action. Molecular endocrinology (Baltimore, Md. 2005;19:2211–2221. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skott O, Uhrenholt TR, Schjerning J, Hansen PB, Rasmussen LE, Jensen BL. Rapid actions of aldosterone in vascular health and disease--friend or foe? Pharmacol Ther. 2006;111:495–507. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weber KT, Sun Y, Wodi LA, Munir A, Jahangir E, Ahokas RA, Gerling IC, Postlethwaite AE, Warrington KJ. Toward a broader understanding of aldosterone in congestive heart failure. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2003;4:155–163. doi: 10.3317/jraas.2003.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Q, Piston DW, Goodman RH. Regulation of corepressor function by nuclear NADH. Science (New York, N Y. 2002;295:1895–1897. doi: 10.1126/science.1069300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Funder JW. RALES, EPHESUS and redox. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;93:121–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu P, Zhang D, Swenson L, Chakrabarti G, Abel ED, Litwin SE. Minimally invasive aortic banding in mice: effects of altered cardiomyocyte insulin signaling during pressure overload. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H1261–1269. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00108.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shimizu G, Hirota Y, Kita Y, Kawamura K, Saito T, Gaasch WH. Left ventricular midwall mechanics in systemic arterial hypertension. Circulation. 1991;83:1676–1684. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.5.1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimizu G, Zile MR, Blaustein AS, Gaasch WH. Left ventricular chamber filling and midwall fiber lengthening in patients with left ventricular hypertrophy: overestimation of fiber velocities by conventional midwall measurements. Circulation. 1985;71:266–272. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.71.2.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borlaug BA, Lam CS, Roger VL, Rodeheffer RJ, Redfield MM. Contractility and ventricular systolic stiffening in hypertensive heart disease insights into the pathogenesis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:410–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen HH, Schirger JA, Chau WL, Jougasaki M, Lisy O, Redfield MM, Barclay PT, Burnett JC., Jr Renal response to acute neutral endopeptidase inhibition in mild and severe experimental heart failure. Circulation. 1999;100:2443–2448. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.24.2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lohmeier TE, Davis JO. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in experimental renal hypertension in the rabbit. The American journal of physiology. 1976;230:311–318. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1976.230.2.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weber KT. Efficacy of aldosterone receptor antagonism in heart failure: potential mechanisms. Current heart failure reports. 2004;1:51–56. doi: 10.1007/s11897-004-0025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grossmann C, Freudinger R, Mildenberger S, Husse B, Gekle M. EF domains are sufficient for nongenomic mineralocorticoid receptor actions. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:7109–7116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708751200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heineke J, Molkentin JD. Regulation of cardiac hypertrophy by intracellular signalling pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:589–600. doi: 10.1038/nrm1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mihailidou AS, Mardini M, Funder JW. Rapid, nongenomic effects of aldosterone in the heart mediated by epsilon protein kinase C. Endocrinology. 2004;145:773–780. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mochly-Rosen D, Wu G, Hahn H, Osinska H, Liron T, Lorenz JN, Yatani A, Robbins J, Dorn GW., 2nd Cardiotrophic effects of protein kinase C epsilon: analysis by in vivo modulation of PKCepsilon translocation. Circulation research. 2000;86:1173–1179. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.11.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takeishi Y, Ping P, Bolli R, Kirkpatrick DL, Hoit BD, Walsh RA. Transgenic overexpression of constitutively active protein kinase C epsilon causes concentric cardiac hypertrophy. Circulation research. 2000;86:1218–1223. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.12.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Costello-Boerrigter LC, Boerrigter G, Harty GJ, Cataliotti A, Redfield MM, Burnett JC., Jr Mineralocorticoid escape by the kidney but not the heart in experimental asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction. Hypertension. 2007;50:481–488. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.088534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shapiro BP, Owan TE, Mohammed S, Kruger M, Linke WA, Burnett JC, Jr, Redfield MM. Mineralocorticoid signaling in transition to heart failure with normal ejection fraction. Hypertension. 2008;51:289–295. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.099010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miura R, Nakamura K, Miura D, Miura A, Hisamatsu K, Kajiya M, Hashimoto K, Nagase S, Morita H, Fukushima Kusano K, Emori T, Ishihara K, Ohe T. Aldosterone synthesis and cytokine production in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Journal of pharmacological sciences. 2006;102:288–295. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fp0060801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schellings MW, Pinto YM, Heymans S. Matricellular proteins in the heart: possible role during stress and remodeling. Cardiovascular research. 2004;64:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sugiyama T, Yoshimoto T, Hirono Y, Suzuki N, Sakurada M, Tsuchiya K, Minami I, Iwashima F, Sakai H, Tateno T, Sato R, Hirata Y. Aldosterone increases osteopontin gene expression in rat endothelial cells. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2005;336:163–167. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fiebeler A, Luft FC. The mineralocorticoid receptor and oxidative stress. Heart failure reviews. 2005;10:47–52. doi: 10.1007/s10741-005-2348-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Armanini D, Fiore C, Calo LA. Mononuclear leukocyte mineralocorticoid receptors. A possible link between aldosterone and atherosclerosis. Hypertension. 2006;47:e4. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000197933.23193.31. author reply e4–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chhokar VS, Sun Y, Bhattacharya SK, Ahokas RA, Myers LK, Xing Z, Smith RA, Gerling IC, Weber KT. Hyperparathyroidism and the calcium paradox of aldosteronism. Circulation. 2005;111:871–878. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000155621.10213.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Selektor Y, Ahokas RA, Bhattacharya SK, Sun Y, Gerling IC, Weber KT. Cinacalcet and the prevention of secondary hyperparathyroidism in rats with aldosteronism. The American journal of the medical sciences. 2008;335:105–110. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318134f013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Selektor Y, Weber KT. The salt-avid state of congestive heart failure revisited. The American journal of the medical sciences. 2008;335:209–218. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181591da0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vidal A, Sun Y, Bhattacharya SK, Ahokas RA, Gerling IC, Weber KT. Calcium paradox of aldosteronism and the role of the parathyroid glands. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H286–294. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00535.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Losel RM, Feuring M, Falkenstein E, Wehling M. Nongenomic effects of aldosterone: cellular aspects and clinical implications. Steroids. 2002;67:493–498. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(01)00176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bhargava A, Fullerton MJ, Myles K, Purdy TM, Funder JW, Pearce D, Cole TJ. The serum- and glucocorticoid-induced kinase is a physiological mediator of aldosterone action. Endocrinology. 2001;142:1587–1594. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.4.8095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]