Abstract

Infusions of antigen-specific T cells have yielded therapeutic responses in patients with pathogens and tumors. To broaden the clinical application of adoptive immunotherapy against malignancies, investigators have developed robust systems for the genetic modification and characterization of T cells expressing introduced chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) to redirect specificity. Human trials are under way in patients with aggressive malignancies to test the hypothesis that manipulating the recipient and reprogramming T cells before adoptive transfer may improve their therapeutic effect. These examples of personalized medicine infuse T cells designed to meet patients' needs by redirecting their specificity to target molecular determinants on the underlying malignancy. The generation of clinical grade CAR+ T cells is an example of bench-to-bedside translational science that has been accomplished using investigator-initiated trials operating largely without industry support. The next-generation trials will deliver designer T cells with improved homing, CAR-mediated signaling, and replicative potential, as investigators move from the bedside to the bench and back again.

Introduction

The systematic development and clinical application of genetically modified T cells is an example of how academic scientists working primarily at nonprofit medical centers are generating a new class of therapeutics. In this context, gene therapy has been used to overcome one of the major barriers to T-cell therapy of cancer, namely tolerance to desired target tumor-associated antigens (TAAs). This was achieved by the introduction of a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) to redirect T-cell specificity to a TAA expressed on the cell surface. The prototypical CAR uses a mouse monoclonal antibody (mAb) that docks with a designated TAA and this binding event is reproduced by the CAR to trigger desired T-cell activation and effector functions. Multiple early-phase clinical trials are now under way or have been completed to evaluate the safety and feasibility of adoptive transfer of CAR+ T cells (Table 1). These pilot studies have revealed challenges in achieving reproducible therapeutic successes which may be solved by (1) reprogramming the T cells themselves for improved replicative potential, effector function, and in vivo persistence, (2) manipulating the recipient to improve TAA expression and survival of infused T cells, and (3) adapting the gene therapy platform to deliver (1) CARs capable of initiating an antigen-dependent fully-competent activation signal, and (2) transgenes to improve safety, persistence, homing, and effector functions within the tumor microenvironment. Academic investigators who work to both develop and deliver investigational biologic agents such as CAR+ T cells are poised to further tighten the pace of discovery between the bench and the bedside to improve the therapeutic potential of genetically modified T cells with redirected specificity. This review builds upon recent articles that describe the immunobiology of CAR+ T cells (Table 2) and we highlight how the CAR technology has been adapted to meet the challenges of infusing genetically modified T cells in medically fragile patients with aggressive malignancies and what new directions the field will need to embrace to undertake multicenter trials to prove their therapeutic efficacy.

Table 1.

Clinical trials in the United States infusing CAR+ T cells under IND

| Antigen | Tumor target | Viral-specific T cell | Lympho-depletion | CAR generation | ClinicalTrial.gov identifier | Enrolling | SAE | Gene transfer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kappa light chain | B-NHL and B-CLL | No | Yes | First and second | NCT00881920 | Yes | TBM | Virus |

| 2 | CD19 | Lymphoma/leukemia (B-NHL) and CLL | No | No | First and second | NCT00586391 | Yes | TBM | Virus |

| 3 | CD19 | Advanced B-NHL/CLL | Yes | No | First and second | NCT00709033 | Yes | TBM | Virus |

| 4 | CD19 | Lymphoma and leukemia | No | Yes | Second | NCT00924326* | Yes | TBM | Virus |

| 5 | CD19 | ALL (post-HSCT) | Yes | No | Second | NCT00840853 | Yes | TBM | Virus |

| 6 | CD19 | Follicular NHL | No | Yes | First | NCT00182650 | No | No | Electroporation |

| 7 | CD19 | CLL | No | Yes/no | Second | NCT00466531* | Yes | Yes (1 Death) | Virus |

| 8 | CD19 | B-NHL/leukemia | No | Yes | First and second | NCT00891215 | Yes | TBM | Virus |

| 9 | CD19 | B-cell leukemia, CLL and B-NHL | No | No | Second | NCT01087294 | Yes | TBM | Virus |

| 10 | CD19 | B-ALL | No | Yes | Second | NCT01044069 | Yes | TBM | Virus |

| 11 | CD19 | B-lymphoid malignancies | No | Yes | Second | NCT00968760 | No | TBM | Electroporation (SB system) |

| 12 | CD20 | Relapsed/refractory B-NHL | No | Yes | First | NCT00012207* | No | No | Electroporation |

| 13 | CD20 | Mantle cell lymphoma or indolent B-NHL | No | Yes | Third | NCT00621452 | Yes | TBM | Electroporation |

| 14 | GD2 | Neuroblastoma | Yes | Yes | First | NCT00085930* | Yes | No | Virus |

| 15 | CEA | Adenocarcinoma | No | No | First | NCT00004178 | No | No | Virus |

| 16 | PSMA | Prostate cancer | No | Yes | First | NCT00664196 | Yes | TBM | Virus |

| 17 | CD171/L1-CAM | Neuroblastoma | No | No | First | NCT00006480 | No | No | Electroporation |

| 18 | FR | Ovarian epithelial cancer | No | No | First | NCT00019136 | No | No | Virus |

| 19 | CEA | Stomach carcinoma | No | No | Second | NCT00429078 | Yes | TBM | Virus |

| 20 | CEA | Breast cancer | No | No | Second | NCT00673829 | Yes | TBM | Virus |

| 21 | CEA | Colorectal carcinoma | No | No | Second | NCT00673322 | Yes | TBM | Virus |

| 22 | IL-13Rα2 | Glioblastoma | No | NA | Second | NCT00730613 | No | No | Electroporation |

| 23 | ERBB2 (HER2/neu) | Metastatic cancer | No | Yes | Third | NCT00924287 | No | Yes (1 Death) | Virus |

| 24 | HER2/neu | Lung malignancy | Yes | No | Second | NCT00889954 | Yes | TBM | Virus |

| 25 | HER2/neu | Advanced osteosarcoma | No | No | Second | NCT00902044 | Yes | TBM | Virus |

ALL indicates acute lymphoblastic leukemia; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; GD2, disialoganglioside; FR, alpha folate receptor; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; L1-CAM, L1 cell adhesion molecule; PSMA, prostate-specific membrane antigen; ERBB2, receptor tyrosine-protein kinase erbB-2; Her2, human epidermal growth factor receptor; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; NA, not available; SB, Sleeping Beauty; TBM, to be monitored; SAE, serious adverse event; and IND, investigational new drug.

Studies have been described to demonstrate a CAR-mediated antitumor effect based on reduction in tumor size. Other trials demonstrated a biologic effect of CAR+ T cells based on reduction in biologic markers of tumor activity.

Table 2.

Published reviews since 2003 on immunobiology and clinical applications of CAR+ T cells

| References | Authors | Year published | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11 | Rossig and Brenner | 2003 |

| 2 | 12 | Willemsen et al | 2003 |

| 3 | 13 | Baxevanis and Papamichail | 2004 |

| 4 | 14 | Rossig and Brenner | 2004 |

| 5 | 15 | Rivière et al | 2004 |

| 6 | 16 | Thistlethwaite et al | 2005 |

| 7 | 17 | Kershaw et al | 2005 |

| 8 | 18 | Dotti and Heslop | 2005 |

| 9 | 19 | Cooper et al | 2005 |

| 10 | 20 | Foster and Rooney | 2006 |

| 11 | 21 | Biagi et al | 2007 |

| 12 | 22 | Rossi et al | 2007 |

| 13 | 23 | Varela-Rohena et al | 2008 |

| 14 | 24 | Eshhar | 2008 |

| 15 | 25 | Marcu-Malina et al | 2009 |

| 16 | 26 | Berry et al | 2009 |

| 17 | 27 | Sadelain et al | 2009 |

| 18 | 28 | June et al | 2009 |

| 19 | 29 | Dotti et al | 2009 |

| 20 | 30 | Till and Press | 2009 |

| 21 | 31 | Vera et al | 2009 |

| 22 | 32 | Brenner and Heslop | 2010 |

| 23 | 33 | Westwood and Kershaw | 2010 |

Redirecting T-cell specificity through the introduction of a CAR

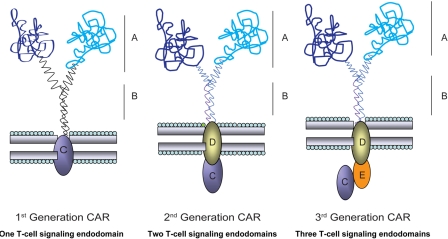

The generation of T bodies, or CARs, by Eshhar et al has been adapted by investigators as a tool to enable T cells, as well as other immune cells, to overcome mechanisms (eg, loss of human leukocyte antigen [HLA]1) by which tumors escape from immune surveillance of the patient's endogenous (unmanipulated) T-cell repertoire.2,3 The specificity of a CAR is achieved by its exodomain which is typically derived from the antigen binding of a mAb linking the VH and VL domains to construct a single-chain fragment variable (scFv) region. The exodomains of CARs have also been fashioned from ligands or peptides (eg, cytokines) to redirect specificity to receptors (eg, cytokine receptors), such as the IL-13Rα2–specific “zetakine.”4 The exodomain is completed by the inclusion of a flexible (hinge) sequence, such as from CD8α or immunoglobulin sequence5,6 and via a transmembrane sequence, the exodomain is fused to 1 or more endodomain(s) which may include cytoplasmic domains from CD3-ϵ, CD3-γ, or CD3-ζ from the T-cell receptor (TCR) complex or high-affinity receptor FcϵRI.7–9 When CARs are expressed on the cell surface of genetically modified T cells, they redirect specificity to TAA (including TAA on tumor progenitor cells10) independent of major histocompatibility complex (MHC). This direct binding of CAR to antigen ideally provides the genetically modified T cell with a fully-competent activation signal, minimally defined as CAR-dependent killing, proliferation, and cytokine production. Given that T cells targeting tumor through an endogenous αβTCR (and even introduced TCR chains34) exhibit such a fully-competent activation signal, investigators have iteratively designed and tested CARs, for example, with 1 or more activation motifs, to try and recapitulate the signaling event mediated by αβTCR chains. These changes to the CAR are enabled by the modular structure of a prototypical CAR and this has resulted in first-, second-, and third-generation CARs designed with 1, 2, or 3 signaling endodomains (Figure 1) including a variety of signaling motifs, such as chimeric CD28, CD134, CD137, Lck, ICOS, and DAP10.6,35–37 A listing of such CARs is provided by Berry et al26 and Sadelain et al.27 While the optimal CAR design remains to be determined, at present it is believed that the first-generation technology, in which a CAR signals solely through immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) domains on CD3-ζ, is insufficient to sustain in vivo persistence of T cells.38 This is supported by early clinical data which demonstrate that CD19-specific,39 CD20-specific,40 GD2-specific (not Epstein-Barr virus [EBV] bispecific),41 and L1-CAM (cell adhesion molecule)–specific42 T cells had apparently short-lived persistence in peripheral blood. The decision regarding which second- or even third-generation CAR design to use in clinical trials is predicated on the ability of a CAR to activate T cells for desired T-cell effector function, which at a minimum includes CAR-dependent killing. However, it is possible that next-generation CARs can be engineered to provide a supraphysiologic activation signal which may be detrimental to continued T-cell survival and perhaps even the well-being of the recipient.43

Figure 1.

Modular structure of prototypical CAR. CAR shown dimerized on the cell surface demonstrating the key extracellular (A-B) and intracellular (C-E) domains. CARs may express 1, 2, or 3 signaling motifs within an endodomain to achieve a CAR-dependent fully-competent T-cell activation signal. The modular structure of the CAR's domains, for example, the scFv (VL linked to VH) region (A) and the flexible hinge and spacer, for example, from IgG4 hinge, CH2, and CH3 regions (B), allow investigators to change specificity through swapping of exodomains and achieve altered function by varying transmembrane and intracellular signaling moieties (C-E).

Modifying the CAR to achieve a fully competent activation signal and reduce immunogenicity

The inclusion of 1 or more T-cell costimulatory molecules within the CAR endodomain is in response to the appreciation that genetically modified and ex vivo–propagated T cells may have down-regulated expression of desired endogenous costimulatory molecules (eg, CD28) or that the ligands for these receptors may be missing on tumor targets (eg, absence of CD80/CD86 on blasts from B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia). By way of example, chimeric CD28 and CD3-ζ,38,44 CD137 and CD3-ζ,23,36 or CD134 and CD3-ζ,45,46 have been incorporated into the design of second-generation CARs with the result that these CARs with multiple chimeric signaling motifs exhibited effector function stemming from a both a primary signal (eg, killing) and costimulatory signal (eg, IL-2 production) after an extracellular recognition event.47,48 Animal studies have demonstrated that T cells expressing a second-generation CD19-specific36,38 and carcinoembryonic antigen-specific CAR49 exhibited an improved antitumor effect compared with T cells bearing a first-generation CAR. In addition to altering the endodomains, investigators have also made changes to the scFv to improve affinity based on selecting high-affinity binding variants from phage arrays.50,51 The approach to developing CAR+ T cells with a calibrated increase in functional affinity may be necessary to enable genetically modified T cells to target tumors with low levels of antigen expression or perhaps to target a cell-surface molecule in the presence of soluble antigen.52,53 Because a CAR typically contains a murine scFv sequence which may be subject to immune recognition leading to deletion of infused T cells, investigators have developed humanized scFv regions to target carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)54,55 and ERBB2 (a member of epidermal growth factor receptor family).6 However, a benefit for using human or humanized scFv regions is yet to be established in the clinical setting.

Imaging CAR+ T cells by positron emission tomography

The ability to genetically modify T cells to redirect specificity provides investigators with a platform to express other transgenes such as for noninvasive imaging. Such temporal-spatial imaging is desired as a surrogate marker for a CAR-mediated antitumor effect and to serially determine number and localization of infused T cells. One imaging transgene coexpressed with CAR is thymidine kinase (TK) and associated mutants from herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1)56 which can be used to enzymatically trap radioactive substrates within the cytoplasm to image the locoregional biodistribution of T cells using positron emission tomography.57–59 The expression of TK also renders CAR+ T cells sensitive to conditional ablation using ganciclovir in a cell-cycle–dependent manner.60–62

Gene transfer of CARs

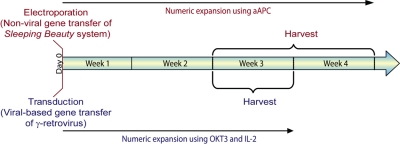

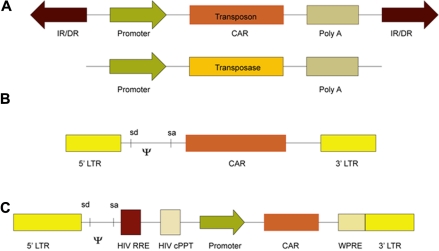

Approaches to the genetic manipulation of T cells for the introduction of CAR transgene use either viral-mediated transduction, or nonviral gene transfer of DNA plasmids or in vitro–transcribed mRNA species. The advantage of retrovirus63–65 or lentivirus23,36,66,67 to modify populations of T cells lies in the efficiency of gene transfer, which shortens the time for culturing T cells to reach clinically-significant numbers (Figure 2). Gamma retroviruses, the most common vector system used to genetically modify clinical grade T cells (Figure 3), have introduced CAR into T cells with a proven ability to exert a therapeutic effect.41 Self-inactivating lentiviral vectors (Figure 3) hold particular appeal as they apparently integrate into quiescent T cells.28 These recombinant viruses often have a high cost to manufacture at clinical grade in specialized facilities skilled in current good manufacturing practice (cGMP) which may preclude investigators from undertaking clinical trials. As an alternative to transduction, we and others have adapted electroporation as an approach to the nonviral gene transfer of DNA42,70,71 resulting in CAR+ T cells that have been attributed to have an antitumor effect in a clinical trial.40 Previously, the electrotransfer and integration of naked plasmid DNA into T cells was considered inefficient because it depended on illegitimate recombination for stable genomic insertion of nonviral sequences. As a result, lengthy in vitro culturing times were required to select for T cells bearing stable integrants72,73 during which period the T cell became differentiated, and perhaps terminally differentiated, into effector cells which may have entered into replicative senescence. This time in tissue culture can now be considerably shortened by using transposon/transposase systems such as Sleeping Beauty (SB)70,74,75 and piggyback76,77 to stably introduce CAR from DNA plasmids (Figure 3).71,76,78–84 We have shown that the SB system can be used to introduce CAR and other transgenes into human T cells with an approximately 60-fold improved integration efficiency compared with electrotransfer of DNA transposon plasmid without transposase74 and this provided the impetus to adapt the SB system for use in clinical trials.85 After electroporation, T-cell numbers from peripheral and umbilical cord blood can be rapidly increased in a CAR-dependent manner by recursive culture on γ-irradiated artificial antigen-presenting cells (aAPC) achieving clinically sufficient numbers of cells for infusion within 3 to 4 weeks after electroporation (Figure 2). Given that T cells transduced with γ-retrovirus are typically cultured with OKT3 and IL-2 for approximately 3 weeks before infusion, the use of the SB system with aAPC does not appear to greatly lengthen the ex vivo culturing process.

Figure 2.

Timeline for in vitro gene transfer and propagation of CAR+ T cells. The electrotransfer of transposon/transposase systems has narrowed the gap between nonviral and viral-based gene transfer for the amount of time in tissue culture needed to generate a clinically sufficient number of genetically modified CAR+ T cells. Cells transduced with virus (blue text) are typically propagated for 3 weeks before infusion.68,69 T cells that undergo nonviral gene transfer with the SB system (red text) can be typically harvested within 4 weeks.

Figure 3.

Schematic of vector systems to express CAR transgenes used in clinical trials. (A) Two SB DNA plasmids expressing a (CAR) transposon and a hyperactive transposase (eg, SB11). Transposition occurs at a TA dinucleotide sequence when the transposase enzymatically acts on the internal repeat flanking the transposon. (B) A recombinant retroviral vector showing the long terminal repeats (LTR) containing the promoter flanking the CAR. SD and SA are the splice donor and splice acceptor sites, respectively, and ψ is the viral packaging signal. (C) A self-inactivating recombinant lentiviral vector construct containing the LTR, ψ, SD and SA sites, HIV Rev response element (RRE), HIV central polypurine tract (cPPT), CAR under control of an internal promoter, and the wood-chuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element (WPRE).

Improving the therapeutic potential of CAR+ T cells

T cells and polarized T-cell subsets, such as TH1 and TH17 cells, may be genetically modified to be specific for a catalog of cell-surface TAAs as described in recent reviews (Table 2). To enable these CAR+ T cells to achieve their full therapeutic potential in clinical trials, there are 3 major challenges to be overcome.

Persistence

The adoptively transferred CAR+ T cells must survive and perhaps also numerically expand to achieve a robust antitumor effect. One approach to improving persistence is to alter the host environment into which the T cells are infused. For example, rendering the recipient lymphopenic, or even aplastic by chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy, improves the persistence of adoptively transferred T cells (and natural killer [NK] cells).86–90 Presumably, the infused T cells proliferate in the lymphopenic recipient through homeostatic mechanisms mediated by the removal of regulatory/suppressor cells and the ready availability of previously scarce homeostatic cytokines. This approach likely improves in vivo persistence and thus efficacy of CAR+ T cells as a published trial and animal studies have hinted.40 However, combining chemotherapy and T-cell therapy might increase toxicity and compromise the interpretation of an antitumor effect for it may be difficult to definitively attribute efficacy to the infused CAR+ T cells in trials enrolling small numbers of patients who received concomitant chemotherapy. Trials infusing T cells expressing a first-generation CAR design (signaling solely through chimeric CD3-ζ endodomain) revealed that these T cells appear to have limited long-term persistence and one way of circumventing this limitation is to engineer CAR endodomains to deliver an activation signal for sustained proliferation. This has been achieved by the design of second-generation CARs that signal through 2 signaling domains and these are now in multiple clinical trials. Third-generation CARs are now being evaluated in humans in a few trials (Table 1) which are composed of 3 chimeric signaling moieties.6,35 Rather than modifying the CAR design to sustain proliferation, investigators have used signaling molecules alongside CARs to achieve improved persistence. For example, constitutively expressed recombinant CD80 and CD137L alongside the CAR demonstrated coordinated signaling between these 2 introduced receptors with endogenous ligands CD28 and CD137 within the immunologic synapse on or between T cells, which could improve antitumor effects.91 CAR has been introduced into T cells expressing endogenous αβTCR that recognize allo-92 or viral antigens.41,93–95 Triggering such TCRs in vivo can be used to numerically expand T cells to achieve an improved antitumor effect delivered by the CAR as was recently demonstrated by infusing bispecific T cells which recognized EBV-specific antigens via the endogenous αβTCR and GD2 on neuroblastoma cells by the introduced CAR.41 Because T cells may require exogenous cytokines to sustain in vivo persistence,96 investigators have enforced expression of cytokines that signal through the common γ cytokine receptor chain. Animal experiments97 as well as clinical experience98,99 have shown that long-lived T cells are associated with expression of the IL-7Rα chain (CD127), but genetically modified and cultured T cells tend to down-regulate this receptor. Therefore, to enhance the ability of T cells to respond to IL-7, made available after inducing lymphopenia,100–102 investigators have enforced the expression of IL-7Rα to demonstrate improved survival of EBV-specific T cells in an animal model103 or introduced a novel membrane-bound variant of IL-7 that when expressed on the cell surface improved persistence of CAR+ T cells.104 Furthermore, overexpression of receptors for IL-2105 and IL-15106 as well as enforced expression of the cytokines themselves107 have improved persistence of T cells.108–110 However, when this approach was tested in a clinical trial infusing tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) genetically modified to constitutively secrete IL-2, the persistence of the adoptively transferred T cells was not improved compared with genetically unmodified TIL.111 As constitutive expression of cytokines and/or cytokine receptors is tested in early clinical trials, investigators will need to consider coexpressing transgenes for conditional ablation of these genetically modified T cells to guard against aberrant proliferation as unopposed cytokine signaling may lead to aberrant T-cell growth.109,112 The type of T cell into which the CAR is introduced may also impact persistence after adoptive immunotherapy. This has been demonstrated in the monkey by infusing autologous preselected central memory T cells which despite ex vivo numeric expansion retained superior in vivo persistence compared with adoptive transfer of differentiated effector T cells.113 These observations have been expanded upon by Hinrichs et al who showed that an infusion of naive murine T cells was associated with improved T-cell persistence.114 These animal observations are likely to influence the design of trials infusing genetically modified T cells as investigators seek to introduce CARs into T cells that preserve the functional capacity of central memory or naive T cells.

Homing

To act on and within the tumor, genetically modified T cells must home to the site(s) of malignancy. Migration may be compromised by the loss of desired chemokine receptors during genetic modification and passage ex vivo, or may result from the selection of T cells that are inherently unable to localize to certain tissues. Panels of tissue-specific homing receptors which are typically composed of integrins, chemokines, and chemokine receptors are associated with T-cell migration to anatomic sites of malignancy, and flow cytometry can therefore be used to describe the potential migration patterns of T cells before infusion.115,116 It is unclear whether T cells capable of expressing a desired matrix of endogenous homing receptors can be genetically modified to express CAR. Therefore, investigators are manipulating the homing potential of T cells through the enforced expression of chemokine receptors such as CCR4.117,118

Overcoming mechanisms of resistance

Once infused T cells persist and home, they must be able to execute and recycle their CAR-dependent effector function, which requires an ability to overcome the adverse regulatory effects within the tumor microenvironment. For example, investigators have introduced a dominant-negative receptor for TGFβ to enable genetically modified T cells can resist the suppressive effects of this pleiotropic cytokine.119 Recognizing that the tumor microenvironment contains regulatory T cells (Tregs), the CAR signaling motif has been adapted to resist the suppressive effects of these cells by the expression of chimeric CD28.120 The ability to engineer CAR+ T cells to successfully function within tumor deposits remains relatively underexplored as most clinical trials to date have used CAR+ T cells with specificity for hematopoietic malignancies. However, trials have been published and are under way which seek to treat solid tumors41,42,121 (Table 1) and systematic approaches to enabling infused T cells to effectively operate within a tumor microenvironment will be needed to reliably eliminate large tumor masses.

Reprogramming T cells

The ex vivo gene transfer and propagation (Figure 2) of T cells provides an opportunity to further manipulate T cells before infusion. The in vitro propagation of T cells provides investigators with an opportunity to numerically expand T cells from scant starting numbers, such as when T cells are genetically modified from umbilical cord blood with the intent to augment the graft-versus-tumor-effect after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT).61 However, the in vitro culturing process can also be adapted to modify T cells for desired effector function by the selective addition of a subset of soluble cytokines, for example, that bind via common γ chain receptor to the culture media during ex vivo culture.122,123 In addition, to help maintain a desired T-cell phenotype after gene transfer, investigators have provided costimulatory signals by the addition of CD28-specific mAb in addition to OKT3, often using beads conjugated to these mAbs. As an alternative, we and others have used immortalized cells in tissue culture, such as 3T3124,125 and K56274,126–128 which can be genetically modified to express desired T-cell costimulatory molecules and function when irradiated as aAPC.

Expressing CARs in cells other than αβ TCR+ T cells

Populations of hematopoietic cells other than T cells expressing αβTCR, such as NK cells, cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cells, monocytes, and neutrophils have been genetically modified to express CARs.27,28 Given the inherent lytic potential of NK cells, redirection of their specificity via a CAR is appealing.129–133 CAR signaling endodomain(s) can be specifically adapted or chosen to enhance NK-cell signaling versus those that activate T cells.134 One drawback to adoptive transfer of NK cells has been their limited survival in vivo after transfer. However, ex vivo NK-cell culturing using aAPC adapted from K562 may change this perception.135,136 Furthermore, the use of NK cells as a cellular platform for introducing CARs may be attractive after allogeneic HSCT as donor-derived NK cells do not appear to significantly contribute to graft-versus-host-disease (GVHD).137,138 T cells expressing γδTCR are another lymphocyte population with endogenous killing ability that has been modified to express CAR, and these cells can be selectively proliferated using an aminobiphosphonate (Zoledronate),139 raising the possibility that a Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved pharmacologic agent can be used to selectively propagate these infused CAR+ T cells in vivo. Instead of genetically modifying mature lymphocytes to express CAR, investigators have introduced CAR into developing thymocytes140 and immunoreceptors into hematopoietic stem cells (HSC)141–143 to avoid negative selection and improve immune-mediated surveillance. The approach of genetically modifying lymphoid precursors has also been adapted by Zakrzewski et al to make “universal T cells” in which CAR+ HSC can be adoptively transferred across MHC barriers.144 It is only a matter of time until embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells are genetically modified to express CAR and differentiated into T cells with redirected and desired specificity. The question remains, however, whether these other populations of cells have a therapeutic advantage over genetic modification and infusion of αβ+ T cells that are genetically modified to express CAR.

Safety of T cells expressing CAR

There are 4 levels of concern associated with the infusion of genetically modified T cells. The first is whether the introduced genetic material can lead to genotoxicity. This remains a theoretical concern for genetically modified T cells, in contrast to HSC.145 The stable expression of CAR requires the introduction of a promoter and the transgene cDNA which raises the possibility of insertional mutagenesis. However, to date, there have been no genotoxic events associated with serious adverse events attributed to genetically modified T cells that have been transduced by recombinant virus or electroporated to introduce DNA plasmid.146 The risk for insertional mutagenesis can be alleviated by the electrotransfer of in vitro transcribed mRNA coding for a CAR. The introduction of mRNA into activated T cells is efficient and as technologies improve to synchronously electroporate large numbers of cells, it may be possible to overcome the expected loss of CAR expression from transient transfection by repeatedly electroporating and administering CAR+ T cells and NK cells.133,147 Regarding the risks of transposition, a review has been published discussing the risks and benefits of the SB system for clinical application which addresses the low potential for genotoxicity.148 For additional reviews on insertional mutagenesis in genetically modified T cells, please refer to Table 2. A second area of concern is whether the CAR can exhibits deleterious effects by damaging normal structures. This remains a concern for all CARs infused in clinical trials as the targeted TAA may also be expressed on the cell surface of normal cells. A clinical trial demonstrated that a low level of carbonic anhydrase expression on normal liver cells led to hepatotoxicity when carbonic-anhydrase-IX (CAIX)–specific T cells were infused to treat metastatic renal cell carcinoma.149 Furthermore, evidence appears to indicate that low-level expression of ERBB2 on normal lung cells may be associated with the sudden death of a patient at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) who received autologous HER2-specific T cells expressing a third-generation CAR along with IL2.43 The risks versus benefits must be calculated for a given patient and a given CAR on case-by-case basis. For example, at present it remains an acceptable risk to infuse CD19-specific T cells, which will not distinguish between CD19 expressed on malignant B cells versus normal B cells, in patients with aggressive B-lineage malignancies, as the risk of loss of normal B-cell function is offset by the potential benefit from an antitumor effect. The third area of concern is the type of T cell being infused. For example, do the introduced transgenes render T cells capable of autonomous proliferation independent of binding TAA? Or, in the allogeneic setting, do the donor-derived T cells target major or minor histocompatibility antigens that can lead to GVHD? The risk of alloreactivity in the context of adoptive transfer of donor-derived CAR-modified T cells may be reduced using ex vivo educated virus-specific T cells which simultaneously provide antiviral protection against opportunistic viruses such as cytomegalovirus, adenovirus, and EBV, through their native αβTCRs, and antileukemia specificity through their transgenic CAR, thereby minimizing the risk of GVHD.150 The fourth risk is the associated therapy that the patient receives along with the CAR+ T cells. For example, the use of lymphodepleting chemotherapy, especially in patients with large amounts of disease and/or poor performance scores (often the case for patients enrolled in phase 1 trials) can lead to attendant toxicities. Recently, Brentjens et al shared their experience infusing autologous CD19-specific T cells expressing a second-generation CAR in a heavily pretreated patient with advanced-stage chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who apparently died from a sepsis-like syndrome associated with acute renal failure after cyclophosphamide to achieve lymphodepletion.151 In response to these serious adverse events, the Office of Biotechnology Activities (OBA) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) met on June 15, 2010 (http://oba.od.nih.gov/rdna_rac/rac_meetings.html) to discuss how to improve safety without compromising the potential efficacy of CAR+ T cells. The risks of adverse events caused by adoptive transfer of CAR+ T cells can also be mitigated by coexpression of a conditional suicide gene, such as HSV-1 TK expressed in haploidentical T cells after allogeneic HSCT to mitigate GVHD.152 A drawback, however, is that the introduced transgene (such as viral-derived TK) is potentially immunogenic which can, on occasion, lead to unwanted immune-mediated destruction, and thus loss of persistence of genetically modified T cells.153–155 However, the degree of immunosuppression induced in the recipient and level of transgene expression likely determine the immunogenicity of the genetically modified cell.156 There are potentially less-immunogenic approaches to rendering T cells sensitive to conditional ablation such as expressing a mutant of human thymidylate kinase157 as well as activating Fas (the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 6) and inducible caspase 9 using a commercial dimerizing agent, which is currently in a clinical trial and has been successfully coexpressed with CAR without impairing its function.158,159 Furthermore, CD20 has been introduced as a nonimmunogenic suicide mechanism as CD20+ T cells could be eliminated by rituximab.160,161 Given the rapidity of the 2 deaths after an infusion of CAR+ T cells (and that 1 death was not attributed to the T cells) it is likely that conditional ablation via a suicide gene would not have altered the kinetics or severity of these serious adverse events. Approaches to decreasing the probability of toxicity include interpatient and intrapatient T-cell dose escalation schemes and splitting a given T-cell dose over 2 or more days.

Combining CAR+ T cells with other immune-based therapies

The therapeutic potential of CAR+ T cells may benefit from the addition of other immune modulators and biologic agents. For example, Tregs cells that might suppress CAR-dependent effector function can be eliminated by lymphodepleting chemotherapy or mAb therapy. To improve persistence after adoptive transfer, virus-specific CAR+ T cells might be administered along with antigen-presenting cells, such as derived from autologous T cells (T-APC) genetically modified to present a viral antigen recognized by the endogenous αβ TCR to activate CAR+ T cells for proliferation.95 Similarly, alloreactive CAR+ T cells might be stimulated with alloantigen in vivo to improve persistence and therapeutic effect.92 CAR+ T cells may also benefit from concomitant mAb therapy162 or immunocytokine help to deliver targeted help.163 CAR+ T cells may also be given with other cells, such as invariant natural killer T cells (iNKT) to sculpt the tumor microenvironment to improve T-cell function.

Regulatory barriers

The safety of the research participants in trials infusing CAR+ T cells is of paramount importance. To maintain the well-being of patients multiple institutional and federal administrative layers of checks and balances have been developed. Thus, the trial's principal investigator and team not only need to develop the infrastructure to support infusing genetically modified T cells, but are required to also obtain approvals from institutional review committees (institutional review board [IRB] and institutional biosafety committee [IBC]) as well as federal regulatory authorities (NIH-OBA and FDA). Furthermore, the cGMP process itself contains checks and balances, as the manufacturing personnel are separate from the quality control program which in turn is separate from the quality assurance team. These processes have emerged to prevent serious adverse events from faults in production of genetically modified T cells. Working within this governance structure takes specialized expertise and consumes time and funding as large documents and copious data are prepared and reviewed. If CAR+ T cells are to enter the mainstream of clinical practice, the regulatory processes will need to adapt so that multi-institution trials can be readily undertaken by academic centers.

Conclusions

The decision to infuse CAR+ T cells is undertaken at the programmatic level as well as at the bedside. Currently, such genetically modified T cells are primarily infused in patients with aggressive malignancies who have received multiple prior therapies, although some pilot trials are investigating infusing CAR+ T cells in patients with minimal residual disease and to prevent relapse in patients at high risk for disease progression. The risk of adoptively transferring genetically modified T cells is justified in these clinical scenarios as the underlying malignancy is considered resistant to conventional therapies. Thus, tolerance by regulators and administrative authorities is needed and appreciated regarding the expected toxicities that are likely to occur as new therapeutic approaches are evaluated in early phase trials enrolling medically fragile patients. Investigator-initiated trials must balance the risks versus benefits, but the pace of genetic therapies needs to accelerate.164–166 One reason for the slow implementation of human studies using genetically modified T cells is that the design and activation of trials to infuse genetically modified T cells with redirected specificity has been expensive, but economies of scale and improvements in cGMP are rapidly driving down the associated costs. This is apparent from an application to the FDA for viral-specific T cells167 to achieve orphan-drug status and their cost compares favorably with current antiviral medications. Indeed, if one considers genetically modified T cells as “drugs,” the costs associated with their generation and delivery compares favorably with other biologic therapies such as mAbs and HSCT.

Scientists working with CAR+ T cells benefit from being able to develop and infuse designer “drugs” that are personalized to the patient's needs and can be manufactured to clinical standards on academic campuses to treat orphan diseases free of the encumbrances associated with manufacturing concerns that generate drugs for profit. This ability to apply cell therapy makes the science of CAR+ T cells compelling not just for redirecting T-cell specificity, but establishes a framework for how nonprofit academic centers can organize their laboratories and resources to operate for all intents and purposes as biotechnology companies to generate a clinical product. Clinical translation of CAR+ T cells is promising given the clinical responses described in early phase trials (Table 1). However, trials powered for efficacy need to be undertaken at multiple centers, to establish the potential of CAR+ T cells to treat malignant disease and to impact clinical practice. The immunobiology of CAR+ T cells has reached a level of maturity where it is now the decision to undertake multicenter gene therapy trials and overcome the associated issues of indemnification and monitoring of an investigational new drug (IND) that will be a major challenge to solve over the next few years.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Malcolm Brenner at the Baylor College of Medicine and Dr Stephen Forman at the City of Hope for helpful discussions and review.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants RO1CA124782 and R01CA120956.

Authorship

Contribution: B.J. and G.D. helped write the paper; and L.J.N.C. originated the concept and helped write the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: L.J.N.C. is the founder of InCellerate Inc. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Laurence J. N. Cooper, MD, PhD, Division of Pediatrics (Unit 907), M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030; e-mail: ljncooper@mdanderson.org

References

- 1.Vago L, Perna SK, Zanussi M, et al. Loss of mismatched HLA in leukemia after stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(5):478–488. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0811036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gross G, Waks T, Eshhar Z. Expression of immunoglobulin-T-cell receptor chimeric molecules as functional receptors with antibody-type specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86(24):10024–10028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.24.10024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eshhar Z, Waks T, Gross G, et al. Specific activation and targeting of cytotoxic lymphocytes through chimeric single chains consisting of antibody-binding domains and the gamma or zeta subunits of the immunoglobulin and T-cell receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(2):720–724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahlon KS, Brown C, Cooper LJ, et al. Specific recognition and killing of glioblastoma multiforme by interleukin 13-zetakine redirected cytolytic T cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64(24):9160–9166. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imai C, Mihara K, Andreansky M, et al. Chimeric receptors with 4-1BB signaling capacity provoke potent cytotoxicity against acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2004;18(4):676–684. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao Y, Wang QJ, Yang S, et al. A herceptin-based chimeric antigen receptor with modified signaling domains leads to enhanced survival of transduced T lymphocytes and antitumor activity. J Immunol. 2009;183(9):5563–5574. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Letourneur F, Klausner RD. T-cell and basophil activation through the cytoplasmic tail of T-cell-receptor zeta family proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(20):8905–8909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.8905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yun CO, Nolan KF, Beecham EJ, et al. Targeting of T lymphocytes to melanoma cells through chimeric anti-GD3 immunoglobulin T-cell receptors. Neoplasia. 2000;2(5):449–459. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abken H, Hombach A, Heuser C. Immune response manipulation: recombinant immunoreceptors endow T-cells with predefined specificity. Curr Pharm Des. 2003;9(24):1992–2001. doi: 10.2174/1381612033454289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown CE, Starr R, Martinez C, et al. Recognition and killing of brain tumor stem-like initiating cells by CD8+ cytolytic T cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69(23):8886–8893. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rossig C, Brenner MK. Chimeric T-cell receptors for the targeting of cancer cells. Acta Haematol. 2003;110(2–3):154–159. doi: 10.1159/000072465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Willemsen RA, Debets R, Chames P, et al. Genetic engineering of T cell specificity for immunotherapy of cancer. Hum Immunol. 2003;64(1):56–68. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(02)00730-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baxevanis CN, Papamichail M. Targeting of tumor cells by lymphocytes engineered to express chimeric receptor genes. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53(10):893–903. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0523-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rossig C, Brenner MK. Genetic modification of T lymphocytes for adoptive immunotherapy. Mol Ther. 2004;10(1):5–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riviere I, Sadelain M, Brentjens RJ. Novel strategies for cancer therapy: the potential of genetically modified T lymphocytes. Curr Hematol Rep. 2004;3(4):290–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thistlethwaite F, Mansoor W, Gilham DE, et al. Engineering T-cells with antibody-based chimeric receptors for effective cancer therapy. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2005;7(1):48–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kershaw MH, Teng MW, Smyth MJ, et al. Supernatural T cells: genetic modification of T cells for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(12):928–940. doi: 10.1038/nri1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dotti G, Heslop HE. Current status of genetic modification of T cells for cancer treatment. Cytotherapy. 2005;7(3):262–272. doi: 10.1080/14653240510027217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooper LJ, Kalos M, DiGiusto D, et al. T-cell genetic modification for re-directed tumor recognition. Cancer Chemother Biol Response Modif. 2005;22:293–324. doi: 10.1016/s0921-4410(04)22014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foster AE, Rooney CM. Improving T cell therapy for cancer. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2006;6(3):215–229. doi: 10.1517/14712598.6.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biagi E, Marin V, Giordano Attianese GM, et al. Chimeric T-cell receptors: new challenges for targeted immunotherapy in hematologic malignancies. Haematologica. 2007;92(3):381–388. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rossi JJ, June CH, Kohn DB. Genetic therapies against HIV. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(12):1444–1454. doi: 10.1038/nbt1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Varela-Rohena A, Carpenito C, Perez EE, et al. Genetic engineering of T cells for adoptive immunotherapy. Immunol Res. 2008;42(1–3):166–181. doi: 10.1007/s12026-008-8057-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eshhar Z. The T-body approach: redirecting T cells with antibody specificity. Hand Exp Pharmacol. 2008;181:329–342. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-73259-4_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marcu-Malina V, van Dorp S, Kuball J. Re-targeting T-cells against cancer by gene-transfer of tumor-reactive receptors. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2009;9(5):579–591. doi: 10.1517/14712590902887018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berry LJ, Moeller M, Darcy PK. Adoptive immunotherapy for cancer: the next generation of gene-engineered immune cells. Tissue Antigens. 2009;74(4):277–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2009.01336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sadelain M, Brentjens R, Riviere I. The promise and potential pitfalls of chimeric antigen receptors. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21(2):215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.June CH, Blazar BR, Riley JL. Engineering lymphocyte subsets: tools, trials and tribulations. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(10):704–716. doi: 10.1038/nri2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dotti G, Savoldo B, Brenner M. Fifteen years of gene therapy based on chimeric antigen receptors: “are we nearly there yet?”. Hum Gene Ther. 2009;20(11):1229–1239. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Till BG, Press OW. Treatment of lymphoma with adoptively transferred T cells. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2009;9(11):1407–1425. doi: 10.1517/14712590903260785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vera JF, Brenner MK, Dotti G. Immunotherapy of human cancers using gene modified T lymphocytes. Curr Gene Ther. 2009;9(5):396–408. doi: 10.2174/156652309789753338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brenner MK, Heslop HE. Adoptive T cell therapy of cancer. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22(2):251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Westwood JA, Kershaw MH. Genetic redirection of T cells for cancer therapy. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;87(5):791–803. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1209824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, et al. Cancer regression in patients after transfer of genetically engineered lymphocytes. Science. 2006;314(5796):126–129. doi: 10.1126/science.1129003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang J, Jensen M, Lin Y, et al. Optimizing adoptive polyclonal T cell immunotherapy of lymphomas, using a chimeric T cell receptor possessing CD28 and CD137 costimulatory domains. Hum Gene Ther. 2007;18(8):712–725. doi: 10.1089/hum.2007.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Milone MC, Fish JD, Carpenito C, et al. Chimeric receptors containing CD137 signal transduction domains mediate enhanced survival of T cells and increased antileukemic efficacy in vivo. Mol Ther. 2009;17(8):1453–1464. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yvon E, Del Vecchio M, Savoldo B, et al. Immunotherapy of metastatic melanoma using genetically engineered GD2-specific T cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(18):5852–5860. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kowolik CM, Topp MS, Gonzalez S, et al. CD28 costimulation provided through a CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor enhances in vivo persistence and antitumor efficacy of adoptively transferred T cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66(22):10995–11004. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jensen MC, Popplewell L, Cooper LJ, et al. Anti-transgene rejection responses contribute to attenuated persistence of adoptively transferred CD20/CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor re-directed T cells in humans [published online ahead of print March 18, 2010]. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.03.014. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Till BG, Jensen MC, Wang J, et al. Adoptive immunotherapy for indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma using genetically modified autologous CD20-specific T cells. Blood. 2008;112(6):2261–2271. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-128843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pule MA, Savoldo B, Myers GD, et al. Virus-specific T cells engineered to coexpress tumor-specific receptors: persistence and antitumor activity in individuals with neuroblastoma. Nat Med. 2008;14(11):1264–1270. doi: 10.1038/nm.1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park JR, Digiusto DL, Slovak M, et al. Adoptive transfer of chimeric antigen receptor re-directed cytolytic T lymphocyte clones in patients with neuroblastoma. Mol Ther. 2007;15(4):825–833. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morgan RA, Yang JC, Kitano M, et al. Case report of a serious adverse event following the administration of T cells transduced with a chimeric antigen receptor recognizing ERBB2. Mol Ther. 2010;18(4):843–851. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moeller M, Haynes NM, Trapani JA, et al. A functional role for CD28 costimulation in tumor recognition by single-chain receptor-modified T cells. Cancer Gene Ther. 2004;11(5):371–379. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Finney HM, Akbar AN, Lawson AD. Activation of resting human primary T cells with chimeric receptors: costimulation from CD28, inducible costimulator, CD134, and CD137 in series with signals from the TCR zeta chain. J Immunol. 2004;172(1):104–113. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pule MA, Straathof KC, Dotti G, et al. A chimeric T cell antigen receptor that augments cytokine release and supports clonal expansion of primary human T cells. Mol Ther. 2005;12(5):933–941. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Finney HM, Lawson AD, Bebbington CR, et al. Chimeric receptors providing both primary and costimulatory signaling in T cells from a single gene product. J Immunol. 1998;161(6):2791–2797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hombach A, Wieczarkowiecz A, Marquardt T, et al. Tumor-specific T cell activation by recombinant immunoreceptors: CD3 zeta signaling and CD28 costimulation are simultaneously required for efficient IL-2 secretion and can be integrated into one combined CD28/CD3 zeta signaling receptor molecule. J Immunol. 2001;167(11):6123–6131. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haynes NM, Trapani JA, Teng MW, et al. Rejection of syngeneic colon carcinoma by CTLs expressing single-chain antibody receptors codelivering CD28 costimulation. J Immunol. 2002;169(10):5780–5786. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Willemsen RA, Debets R, Hart E, et al. A phage display selected fab fragment with MHC class I-restricted specificity for MAGE-A1 allows for retargeting of primary human T lymphocytes. Gene Ther. 2001;8(21):1601–1608. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pameijer CR, Navanjo A, Meechoovet B, et al. Conversion of a tumor-binding peptide identified by phage display to a functional chimeric T cell antigen receptor. Cancer Gene Ther. 2007;14(1):91–97. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chmielewski M, Hombach A, Heuser C, et al. T cell activation by antibody-like immunoreceptors: increase in affinity of the single-chain fragment domain above threshold does not increase T cell activation against antigen-positive target cells but decreases selectivity. J Immunol. 2004;173(12):7647–7653. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vera J, Savoldo B, Vigouroux S, et al. T lymphocytes redirected against the kappa light chain of human immunoglobulin efficiently kill mature B lymphocyte-derived malignant cells. Blood. 2006;108(12):3890–3897. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-017061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nolan KF, Yun CO, Akamatsu Y, et al. Bypassing immunization: optimized design of “designer T cells” against carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)-expressing tumors, and lack of suppression by soluble CEA. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5(12):3928–3941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hombach A, Schneider C, Sent D, et al. An entirely humanized CD3 zeta-chain signaling receptor that directs peripheral blood t cells to specific lysis of carcinoembryonic antigen-positive tumor cells. Int J Cancer. 2000;88(1):115–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Heyman RA, Borrelli E, Lesley J, et al. Thymidine kinase obliteration: creation of transgenic mice with controlled immune deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86(8):2698–2702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yaghoubi SS, Jensen MC, Satyamurthy N, et al. Noninvasive detection of therapeutic cytolytic T cells with 18F-FHBG PET in a patient with glioma. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2009;6(1):53–58. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dobrenkov K, Olszewska M, Likar Y, et al. Monitoring the efficacy of adoptively transferred prostate cancer-targeted human T lymphocytes with PET and bioluminescence imaging. J Nucl Med. 2008;49(7):1162–1170. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.047324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Singh H, Najjar AM, Olivares S, et al. PET imaging of T cells derived from umbilical cord blood. Leukemia. 2009;23(3):620–622. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Munshi NC, Govindarajan R, Drake R, et al. Thymidine kinase (TK) gene-transduced human lymphocytes can be highly purified, remain fully functional, and are killed efficiently with ganciclovir. Blood. 1997;89(4):1334–1340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Serrano LM, Pfeiffer T, Olivares S, et al. Differentiation of naive cord-blood T cells into CD19-specific cytolytic effectors for posttransplantation adoptive immunotherapy. Blood. 2006;107(7):2643–2652. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cooper LJ, Ausubel L, Gutierrez M, et al. Manufacturing of gene-modified cytotoxic T lymphocytes for autologous cellular therapy for lymphoma. Cytotherapy. 2006;8(2):105–117. doi: 10.1080/14653240600620176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rosenberg SA, Aebersold P, Cornetta K, et al. Gene transfer into humans–immunotherapy of patients with advanced melanoma, using tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes modified by retroviral gene transduction. N Engl J Med. 1990;323(9):570–578. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199008303230904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rischer M, Pscherer S, Duwe S, et al. Human gammadelta T cells as mediators of chimaeric-receptor redirected anti-tumour immunity. Br J Haematol. 2004;126(4):583–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Turatti F, Figini M, Alberti P, et al. Highly efficient redirected anti-tumor activity of human lymphocytes transduced with a completely human chimeric immune receptor. J Gene Med. 2005;7(2):158–170. doi: 10.1002/jgm.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gyobu H, Tsuji T, Suzuki Y, et al. Generation and targeting of human tumor-specific Tc1 and Th1 cells transduced with a lentivirus containing a chimeric immunoglobulin T-cell receptor. Cancer Res. 2004;64(4):1490–1495. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Naldini L, Blomer U, Gallay P, et al. In vivo gene delivery and stable transduction of nondividing cells by a lentiviral vector. Science. 1996;272(5259):263–267. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kochenderfer JN, Feldman SA, Zhao Y, et al. Construction and preclinical evaluation of an anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor. J Immunother. 2009;32(7):689–702. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181ac6138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hollyman D, Stefanski J, Przybylowski M, et al. Manufacturing validation of biologically functional T cells targeted to CD19 antigen for autologous adoptive cell therapy. J Immunother. 2009;32(2):169–180. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318194a6e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Geurts AM, Yang Y, Clark KJ, et al. Gene transfer into genomes of human cells by the sleeping beauty transposon system. Mol Ther. 2003;8(1):108–117. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Huang X, Guo H, Kang J, et al. Sleeping Beauty transposon-mediated engineering of human primary T cells for therapy of CD19+ lymphoid malignancies. Mol Ther. 2008;16(3):580–589. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cooper LJ, Topp MS, Serrano LM, et al. T-cell clones can be rendered specific for CD19: toward the selective augmentation of the graft-versus-B-lineage leukemia effect. Blood. 2003;101(4):1637–1644. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jensen MC, Clarke P, Tan G, et al. Human T lymphocyte genetic modification with naked DNA. Mol Ther. 2000;1(1):49–55. doi: 10.1006/mthe.1999.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Singh H, Manuri PR, Olivares S, et al. Redirecting specificity of T-cell populations for CD19 using the Sleeping Beauty system. Cancer Res. 2008;68(8):2961–2971. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xue X, Huang X, Nodland SE, et al. Stable gene transfer and expression in cord blood-derived CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells by a hyperactive Sleeping Beauty transposon system. Blood. 2009;114(7):1319–1330. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-210005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Manuri PV, Wilson MH, Maiti SN, et al. piggyBac transposon/transposase system to generate CD19-specific T cells for the treatment of B-lineage malignancies. Hum Gene Ther. 2010;21(4):427–437. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nakazawa Y, Huye LE, Dotti G, et al. Optimization of the PiggyBac transposon system for the sustained genetic modification of human T lymphocytes. J Immunother. 2009;32(8):826–836. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181ad762b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ivics Z, Hackett PB, Plasterk RH, et al. Molecular reconstruction of Sleeping Beauty, a Tc1-like transposon from fish, and its transposition in human cells. Cell. 1997;91(4):501–510. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80436-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hackett PB, Ekker SC, Largaespada DA, et al. Sleeping beauty transposon-mediated gene therapy for prolonged expression. Adv Genet. 2005;54(0):189–232. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2660(05)54009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Frommolt R, Rohrbach F, Theobald M. Sleeping Beauty transposon system–future trend in T-cell-based gene therapies? Future Oncol. 2006;2(3):345–349. doi: 10.2217/14796694.2.3.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Geurts AM, Hackett CS, Bell JB, et al. Structure-based prediction of insertion-site preferences of transposons into chromosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(9):2803–2811. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hollis RP, Nightingale SJ, Wang X, et al. Stable gene transfer to human CD34(+) hematopoietic cells using the Sleeping Beauty transposon. Exp Hematol. 2006;34(10):1333–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wilber A, Linehan JL, Tian X, et al. Efficient and stable transgene expression in human embryonic stem cells using transposon-mediated gene transfer. Stem Cells. 2007;25(11):2919–2927. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Izsvak Z, Chuah MK, Vandendriessche T, et al. Efficient stable gene transfer into human cells by the Sleeping Beauty transposon vectors. Methods. 2009;49(3):287–297. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Williams DA. Sleeping beauty vector system moves toward human trials in the United States. Mol Ther. 2008;16(9):1515–1516. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Robbins PF, et al. Cancer regression and autoimmunity in patients after clonal repopulation with antitumor lymphocytes. Science. 2002;298(5594):850–854. doi: 10.1126/science.1076514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Miller JS, Soignier Y, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, et al. Successful adoptive transfer and in vivo expansion of human haploidentical NK cells in patients with cancer. Blood. 2005;105(8):3051–3057. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wrzesinski C, Paulos CM, Gattinoni L, et al. Hematopoietic stem cells promote the expansion and function of adoptively transferred antitumor CD8 T cells. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(2):492–501. doi: 10.1172/JCI30414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wallen H, Thompson JA, Reilly JZ, et al. Fludarabine modulates immune response and extends in vivo survival of adoptively transferred CD8 T cells in patients with metastatic melanoma. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(3):e4749. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wrzesinski C, Paulos CM, Kaiser A, et al. Increased intensity lymphodepletion enhances tumor treatment efficacy of adoptively transferred tumor-specific T cells. J Immunother. 2010;33(1):1–7. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181b88ffc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Stephan MT, Ponomarev V, Brentjens RJ, et al. T cell-encoded CD80 and 4-1BBL induce auto- and transcostimulation, resulting in potent tumor rejection. Nat Med. 2007;13(12):1440–1449. doi: 10.1038/nm1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kershaw MH, Westwood JA, Hwu P. Dual-specific T cells combine proliferation and antitumor activity. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20(12):1221–1227. doi: 10.1038/nbt756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Patel SD, Moskalenko M, Tian T, et al. T-cell killing of heterogenous tumor or viral targets with bispecific chimeric immune receptors. Cancer Gene Ther. 2000;7(8):1127–1134. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rossig C, Bollard CM, Nuchtern JG, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-specific human T lymphocytes expressing antitumor chimeric T-cell receptors: potential for improved immunotherapy. Blood. 2002;99(6):2009–2016. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cooper LJ, Al-Kadhimi Z, Serrano LM, et al. Enhanced antilymphoma efficacy of CD19-redirected influenza MP1-specific CTLs by cotransfer of T cells modified to present influenza MP1. Blood. 2005;105(4):1622–1631. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yee C, Thompson JA, Byrd D, et al. Adoptive T cell therapy using antigen-specific CD8+ T cell clones for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma: in vivo persistence, migration, and antitumor effect of transferred T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(25):16168–16173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242600099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Carrio R, Rolle CE, Malek TR. Non-redundant role for IL-7R signaling for the survival of CD8+ memory T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37(11):3078–3088. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Powell DJ, Jr, Dudley ME, Robbins PF, et al. Transition of late-stage effector T cells to CD27+ CD28+ tumor-reactive effector memory T cells in humans after adoptive cell transfer therapy. Blood. 2005;105(1):241–250. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cooper LJ. Long Live T Cells. Blood. 2005;105(1):8–9. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rosenberg SA, Sportes C, Ahmadzadeh M, et al. IL-7 administration to humans leads to expansion of CD8+ and CD4+ cells but a relative decrease of CD4+ T-regulatory cells. J Immunother. 2006;29(3):313–319. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000210386.55951.c2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sportes C, Hakim FT, Memon SA, et al. Administration of rhIL-7 in humans increases in vivo TCR repertoire diversity by preferential expansion of naive T cell subsets. J Exp Med. 2008;205(7):1701–1714. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Capitini CM, Chisti AA, Mackall CL. Modulating T-cell homeostasis with IL-7: preclinical and clinical studies. J Intern Med. 2009;266(2):141–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02085.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Vera JF, Hoyos V, Savoldo B, et al. Genetic manipulation of tumor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes to restore responsiveness to IL-7. Mol Ther. 2009;17(5):880–888. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hurton L, Singh H, Olivares S, et al. IL-7 as a Membrane-Bound Molecule for the Costimulation of Tumor-Specific T Cells. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) 2009;114(22):3035. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sogo T, Kawahara M, Tsumoto K, et al. Selective expansion of genetically modified T cells using an antibody/interleukin-2 receptor chimera. J Immunol Methods. 2008;337(1):16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rowley JMA, Hung CF, Wu TC. Expression of IL-15RA or an IL-15/IL-15RA fusion on CD8+ T cells modifies adoptively transferred T-cell function in cis. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39(2):491–506. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Markley JC, Sadelain M. IL-7 and IL-21 are superior to IL-2 and IL-15 in promoting human T cell-mediated rejection of systemic lymphoma in immunodeficient mice. Blood. 2010;115(17):3508–3519. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-241398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Liu K, Rosenberg SA. Transduction of an IL-2 gene into human melanoma-reactive lymphocytes results in their continued growth in the absence of exogenous IL-2 and maintenance of specific antitumor activity. J Immunol. 2001;167(11):6356–6365. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hsu C, Jones SA, Cohen CJ, et al. Cytokine-independent growth and clonal expansion of a primary human CD8+ T-cell clone following retroviral transduction with the IL-15 gene. Blood. 2007;109(12):5168–5177. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-029173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hoyos V, Savoldo B, Quintarelli C, et al. Engineering CD19-specific T lymphocytes with interleukin-15 and a suicide gene to enhance their anti-lymphoma/leukemia effects and safety. Leukemia. 2010;24(6):1160–1170. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Heemskerk B, Liu K, Dudley ME, et al. Adoptive cell therapy for patients with melanoma, using tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes genetically engineered to secrete interleukin-2. Hum Gene Ther. 2008;19(5):496–510. doi: 10.1089/hum.2007.0171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Quintarelli C, Vera JF, Savoldo B, et al. Co-expression of cytokine and suicide genes to enhance the activity and safety of tumor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Blood. 2007;110(8):2793–2802. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-072843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Berger C, Jensen MC, Lansdorp PM, et al. Adoptive transfer of effector CD8+ T cells derived from central memory cells establishes persistent T cell memory in primates. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(1):294–305. doi: 10.1172/JCI32103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hinrichs CS, Borman ZA, Cassard L, et al. Adoptively transferred effector cells derived from naive rather than central memory CD8+ T cells mediate superior antitumor immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(41):17469–17474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907448106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Brown CE, Vishwanath RP, Aguilar B, et al. Tumor-derived chemokine MCP-1/CCL2 is sufficient for mediating tumor tropism of adoptively transferred T cells. J Immunol. 2007;179(5):3332–3341. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.3332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Palendira U, Chinn R, Raza W, et al. Selective accumulation of virus-specific CD8+ T cells with unique homing phenotype within the human bone marrow. Blood. 2008;112(8):3293–3302. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-138040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kershaw MH, Wang G, Westwood JA, et al. Redirecting migration of T cells to chemokine secreted from tumors by genetic modification with CXCR2. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13(16):1971–1980. doi: 10.1089/10430340260355374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Di Stasi A, De Angelis B, Rooney CM, et al. T lymphocytes coexpressing CCR4 and a chimeric antigen receptor targeting CD30 have improved homing and antitumor activity in a Hodgkin tumor model. Blood. 2009;113(25):6392–6402. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-209650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Bollard CM, Rossig C, Calonge MJ, et al. Adapting a transforming growth factor beta-related tumor protection strategy to enhance antitumor immunity. Blood. 2002;99(9):3179–3187. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.9.3179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Loskog A, Giandomenico V, Rossig C, et al. Addition of the CD28 signaling domain to chimeric T-cell receptors enhances chimeric T-cell resistance to T regulatory cells. Leukemia. 2006;20(10):1819–1828. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kershaw MH, Westwood JA, Parker LL, et al. A phase I study on adoptive immunotherapy using gene-modified T cells for ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(20 Pt 1):6106–6115. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Liu S, Riley J, Rosenberg S, et al. Comparison of common gamma-chain cytokines, interleukin-2, interleukin-7, and interleukin-15 for the in vitro generation of human tumor-reactive T lymphocytes for adoptive cell transfer therapy. J Immunother. 2006;29(3):284–293. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000190168.53793.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Rochman Y, Spolski R, Leonard WJ. New insights into the regulation of T cells by gamma(c) family cytokines. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(7):480–490. doi: 10.1038/nri2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Brentjens RJ, Latouche JB, Santos E, et al. Eradication of systemic B-cell tumors by genetically targeted human T lymphocytes co-stimulated by CD80 and interleukin-15. Nat Med. 2003;9(3):279–286. doi: 10.1038/nm827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Hasan AN, Kollen WJ, Trivedi D, et al. A panel of artificial APCs expressing prevalent HLA alleles permits generation of cytotoxic T cells specific for both dominant and subdominant viral epitopes for adoptive therapy. J Immunol. 2009;183(4):2837–2850. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Numbenjapon T, Serrano LM, Singh H, et al. Characterization of an artificial antigen-presenting cell to propagate cytolytic CD19-specific T cells. Leukemia. 2006;20(10):1889–1892. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Suhoski MM, Golovina TN, Aqui NA, et al. Engineering artificial antigen-presenting cells to express a diverse array of co-stimulatory molecules. Mol Ther. 2007;15(5):981–988. doi: 10.1038/mt.sj.6300134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Butler MO, Lee JS, Ansen S, et al. Long-lived antitumor CD8+ lymphocytes for adoptive therapy generated using an artificial antigen-presenting cell. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(6):1857–1867. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Imai C, Iwamoto S, Campana D. Genetic modification of primary natural killer cells overcomes inhibitory signals and induces specific killing of leukemic cells. Blood. 2005;106(1):376–383. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Zhang T, Lemoi BA, Sentman CL. Chimeric NK-receptor-bearing T cells mediate antitumor immunotherapy. Blood. 2005;106(5):1544–1551. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Muller T, Uherek C, Maki G, et al. Expression of a CD20-specific chimeric antigen receptor enhances cytotoxic activity of NK cells and overcomes NK-resistance of lymphoma and leukemia cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57(3):411–423. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0383-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Pegram HJ, Jackson JT, Smyth MJ, et al. Adoptive transfer of gene-modified primary NK cells can specifically inhibit tumor progression in vivo. J Immunol. 2008;181(5):3449–3455. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Boissel L, Betancur M, Wels WS, et al. Transfection with mRNA for CD19 specific chimeric antigen receptor restores NK cell mediated killing of CLL cells. Leuk Res. 2009;33(9):1255–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Cooper LJ. Persuading natural killer cells to eliminate bad B cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(15):4790–4791. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Fujisaki H, Kakuda H, Shimasaki N, et al. Expansion of highly cytotoxic human natural killer cells for cancer cell therapy. Cancer Res. 2009;69(9):4010–4017. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Denman CJ, Kopp LM, Senyukov V, et al. Sustained ex vivo expansion of human peripheral blood NK cells using artificial APCs bearing membrane-bound IL-21. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) 2009;114(11) Abstract 3030. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Farag SS, Fehniger TA, Ruggeri L, et al. Natural killer cell receptors: new biology and insights into the graft-versus-leukemia effect. Blood. 2002;100(6):1935–1947. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Ruggeri L, Capanni M, Urbani E, et al. Effectiveness of donor natural killer cell alloreactivity in mismatched hematopoietic transplants. Science. 2002;295(5562):2097–2100. doi: 10.1126/science.1068440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Kondo M, Sakuta K, Noguchi A, et al. Zoledronate facilitates large-scale ex vivo expansion of functional gammadelta T cells from cancer patients for use in adoptive immunotherapy. Cytotherapy. 2008;10(8):842–856. doi: 10.1080/14653240802419328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Papapetrou EP, Kovalovsky D, Beloeil L, et al. Harnessing endogenous miR-181a to segregate transgenic antigen receptor expression in developing versus post-thymic T cells in murine hematopoietic chimeras. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(1):157–168. doi: 10.1172/JCI37216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Yang L, Baltimore D. Long-term in vivo provision of antigen-specific T cell immunity by programming hematopoietic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(12):4518–4523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500600102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Stolzer AL, Sadelain M, Sant'Angelo DB. Fulminant experimental autoimmune encephalo-myelitis induced by retrovirally mediated TCR gene transfer. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35(6):1822–1830. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]