Abstract

Glucuronoarabinoxylans (GAXs) are the major hemicelluloses in grass cell walls, but the proteins that synthesize them have previously been uncharacterized. The biosynthesis of GAXs would require at least three glycosyltransferases (GTs): xylosyltransferase (XylT), arabinosyltransferase (AraT), and glucuronosyltransferase (GlcAT). A combination of proteomics and transcriptomics analyses revealed three wheat (Triticum aestivum) glycosyltransferase (TaGT) proteins from the GT43, GT47, and GT75 families as promising candidates involved in GAX synthesis in wheat, namely TaGT43-4, TaGT47-13, and TaGT75-4. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments using specific antibodies produced against TaGT43-4 allowed the immunopurification of a complex containing these three GT proteins. The affinity-purified complex also showed GAX-XylT, GAX-AraT, and GAX-GlcAT activities that work in a cooperative manner. UDP Xyl strongly enhanced both AraT and GlcAT activities. However, while UDP arabinopyranose stimulated the XylT activity, it had only limited effect on GlcAT activity. Similarly, UDP GlcUA stimulated the XylT activity but had only limited effect on AraT activity. The [14C]GAX polymer synthesized by the affinity-purified complex contained Xyl, Ara, and GlcUA in a ratio of 45:12:1, respectively. When this product was digested with purified endoxylanase III and analyzed by high-pH anion-exchange chromatography, only two oligosaccharides were obtained, suggesting a regular structure. One of the two oligosaccharides has six Xyls and two Aras, and the second oligosaccharide contains Xyl, Ara, and GlcUA in a ratio of 40:8:1, respectively. Our results provide a direct link of the involvement of TaGT43-4, TaGT47-13, and TaGT75-4 proteins (as a core complex) in the synthesis of GAX polymer in wheat.

Understanding plant cell wall polysaccharide biosynthesis has been hampered by a lack of information on how individual glycosyltransferases (GTs) might be organized into functional polysaccharide synthase complexes. The most successful study on such synthase complexes comes from the work on cellulose synthesis, where a multiprotein cellulose synthase complex (rosette) was successfully solubilized in an active form (Lai-Kee-Him et al., 2002). Genetic studies revealed the composition of these complexes, which is different depending on whether they are involved in primary or secondary cell wall synthesis (for review, see Somerville, 2006). In sharp contrast, the composition and function of hemicellulose synthase complexes are far from understood. For example, several xyloglucan (XyG) biosynthetic GTs have been characterized (Faik et al., 2002; Madson et al., 2003; Cavalier and Keegstra, 2006; Cocuron et al., 2007), but how these GTs work together is still unknown. It has been suggested that UDP-Gal is channeled to XyG biosynthesis through a complex formed by UDP-Glc 4-epimerase and XyG galactosyltransferase (MUR3; Seifert et al., 2002; Nguema-Ona et al., 2006); however, direct biochemical evidence of such a complex is still missing. Although the elaboration of the backbone of galacto(gluco)mannans and (1,3;1,4)-β-d-glucans (mixed-linkage glucans [MLG]) could be produced by a single protein (Dhugga et al., 2004; Liepman et al., 2005; Burton et al., 2006; Doblin et al., 2009), it is believed that multienzyme complexes, for which we do not yet know the composition, synthesize these polymers. We built upon the progress we had made in glucuronoarabinoxylan (GAX) biosynthesis (Zeng et al., 2008) to purify and analyze the GAX synthase complex in wheat (Triticum aestivum).

In general, xylans from grasses have a (1,4)-β-d-xylan backbone, substituted depending on the tissues and species, at the C-2 and/or C-3 positions, with α-l-arabinofuranosyl (Araf) residues or to a lesser extent with α-d-glucuronosyl (GlcA) or O-methyl-GlcA residues on the C-2 position (Carpita and Gibeaut, 1993; Ebringerova et al., 2005). Investigating the biosynthetic mechanism of these xylans has proven to be difficult. For example, biochemical studies over many years have succeeded in detecting xylan/GAX synthesis activity in microsomes (Bailey and Hassid, 1966; Dalessandro and Northcote, 1981; Porchia and Scheller 2000; Gregory et al., 2002; Urahara et al., 2004; Zeng et al., 2008), but these efforts did not identify any GT protein associated with the enzymatic activities. On the genetics side, the first hint connecting some GT genes to xylan biosynthesis came from microarray analysis using developing xylem tissues from hybrid aspen (Populus tremula × Populus tremuloides) and CAZy bioinformatics tools (http://afmb.cnrs-mrs.fr/CAZY; Aspeborg et al., 2005). This microarray analysis revealed the identities of 25 xylem-specific GT genes belonging to seven GT families in the CAZy database: the GT2, GT8, GT14, GT31, GT43, GT47, and GT61 families. At the same time, studies on Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) irregular xylem (irx) mutants confirmed members of the GT8, GT43, and GT47 families as potential glucuronoxylan (GX) biosynthetic genes (Brown et al., 2005; Zhong et al., 2005; Pena et al., 2007; Persson et al., 2007). However, the exact biochemical functions proposed for the gene products are still hypothetical.

The current outstanding question is whether dicots and monocots use the same mechanisms to synthesize their xylan polymers, and more specifically, whether members of the GT8, GT43, and GT47 families are also involved in the biosynthetic process in monocots. Mitchell et al. (2007) used differential expression of cereal orthologs of Arabidopsis GT genes to identify candidate GTs that are highly represented in grasses and thus might be involved in the biosynthesis of GAX, the most abundant hemicelluloses in their cell walls. Interestingly, in addition to the GT43 and GT47 families, this study also suggested that the GT61 family might be involved in AX biosynthesis in cereals. In this work, we used our GAX biosynthesis assay (Zeng et al., 2008) to develop a strategy for partial purification of the activity and determined the proteins associated with this activity through proteomics. We also took advantage of the public wheat EST databases to identify, by “digital northern” analysis, the most promising genes for AX synthesis. The combination of the two strategies revealed three wheat genes, TaGT43-4, TaGT47-13, and TaGT75-4, as the most promising candidates, and coimmunoprecipitation experiments provided supporting evidence for their involvement in GAX biosynthesis as a complex.

RESULTS

Partial Purification of Wheat GAX Synthase Activity and Proteomics Analysis

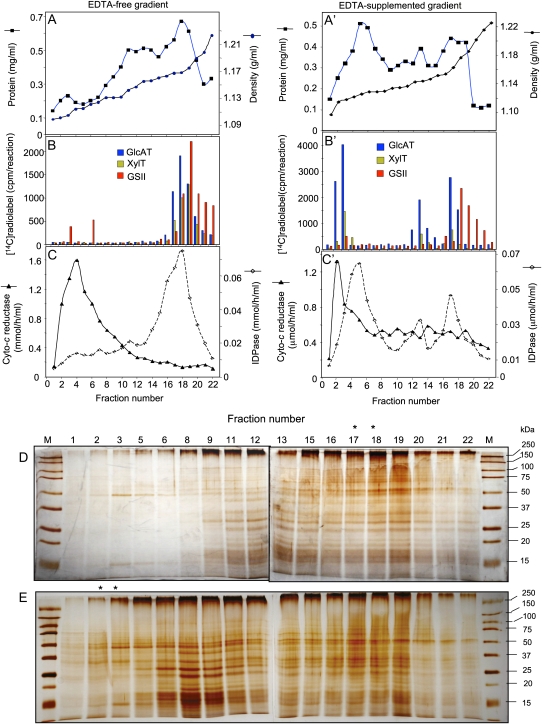

Zeng et al. (2008) developed a novel enzyme assay to measure the GAX synthesis activity in wheat microsomes. Here, we used that assay to enrich membrane fractions in glucuronosyltransferase (GlcAT) and xylosyltransferase (XylT) activities and used proteomics methods to identify the peptides associated with these activities. Our purification procedure involved two simple fractionation steps. First, the crude membranes prepared from etiolated wheat seedlings as described by Zeng et al. (2008) were fractionated on a discontinuous Suc density gradient using 1.1 and 0.25 m Suc solutions on the top of the crude membrane preparation. After centrifugation, the membranes located at the 1.1/0.25 m Suc interface contained about 50% of the total GlcAT and XylT activities, with specific activities of approximately 51 and approximately 2,400 pmol h−1 mg−1 protein, respectively, providing a purification of 5- to 8-fold for both activities. The second fractionation step consisted of further separation of the membranes collected at the 1.1/0.25 m Suc interface on a continuous 25% to 40% (w/v) Suc density gradient in the absence or the presence of 1 mm EDTA. We compared the GlcAT and XylT activity distribution with the distribution of marker enzyme activities for Golgi, endoplasmic reticulum, and plasma membranes, specifically inosine diphosphatase (IDPase), cytochrome c reductase, and callose synthase II (GSII), respectively. The distribution of endoplasmic reticulum and plasma membrane marker enzyme activities was not affected by the inclusion of EDTA but was stabilized at the expected densities, namely, approximately 1.12 g mL−1 (fraction 4) for endoplasmic reticulum and approximately 1.18 g mL−1 (fraction 19) for GSII (Fig. 1, compare B, B′, and C, C′). However, the inclusion of EDTA drastically affected the distribution of GlcAT, XylT, and IDPase activities across the gradient. For example, in the absence of EDTA, most GlcAT and XylT activities stabilized at density approximately 1.16 g mL−1 (fractions 17 and 18), along with the peak of IDPase activity (Fig. 1, B and C), while in the presence of EDTA, both GlcAT and XylT activities stabilized as two main peaks around density 1.12 g mL−1 (fractions 2 and 3) and around density 1.16 g mL−1 (fraction 17), with a minor peak around density 1.14 g mL−1 (fraction 13; Fig. 1B′). IDPase activity also showed a similar shift in the distribution, lending support to the localization of these activities to the Golgi compartments (Fig. 1C′). The presence of multiple peaks of activity could be explained by the separation of Golgi compartments (cis-, medial, and trans-cisterna) or the presence of Golgi from different cell types or cell developmental stages having different densities. However, since fractions 2 and 3 after the EDTA-supplemented gradient contained XylT and GlcAT activities but only a limited number of other proteins (as detected by SDS-PAGE; Fig. 1E), they were combined and used for peptide fingerprinting using multidimensional protein identification (Kislinger et al., 2005) and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (Sazuka et al., 2004). The strategy used in proteomics analysis is depicted in Supplemental Figure S1. Most of the proteins identified by these proteomics methods have no obvious role in GAX biosynthesis, except wheat members of the GT47 and GT75 families. Specifically, proteomics analysis produced the IEGSAGDVLEDDPVGR peptide sequence (score of 79), which was a perfect match with rice (Oryza sativa) protein Os01g0926700 (a member of the GT47 family), and several peptide sequences that were perfect matches to rice reversibly glycosylated polypeptides (RGPs), members of the GT75 family (GIFWQEDIIPFFQNATIPK, NLDFLEMWRPFFQPYHLIIVQDGDPSK, YVDAVLTIPK, TGLPYLWHSK, VPEGFDYELYNR, NLLSPSTPFFFNTLYDPYR, and EGAPTAVSHGLWLNIPDYDAPTQMVKPR, all with scores higher than 100). Because proteomics methods may have limitations in identifying all GT proteins, we used transcriptomic-based methods to complement this study.

Figure 1.

Partial purification of wheat GAX synthase activity. Microsomal membranes enriched in GAX synthase activity were fractionated on a linear (25%–40%) Suc density gradient in the absence (A–C) or in the presence (A′–C′) of 1 mm EDTA. The gradient was separated into 22 equal fractions of 1 mL. A and A′, Protein content and Suc density measurement in each fraction. B and B′, Incorporation (cpm reaction−1) of 14C radiolabel from UDP-[14C]GlcA, UDP-[14C]Xyl, or UDP-[14C]Glc by each fraction. C and C′, IDPase and cytochrome c reductase activities in each fraction. D and E, SDS-PAGE and silver staining analysis of the fractions from EDTA-free (D) or EDTA-supplemented (E) gradient. The fraction numbers are indicated on the top of the gels, and the molecular mass (M) markers (kD) are indicated on the right of the gels. The fractions with high GAX synthase activity are indicated by asterisks in D and E.

Identification of Wheat GT Genes and Transcriptional Profiling Analysis

Transcriptional profiling analysis would require that we first construct DNA sequences of several wheat candidate genes using EST databases. We focused on the GT2, GT8, GT43, GT47, GT61, and GT75 families because some members of these families are known to be involved in the biosynthesis of GX in dicots (e.g. GT8, GT43, and GT47; Brown et al., 2005, 2007; Zhong et al., 2005; Pena et al., 2007; Persson et al., 2007) or MLG in grasses (e.g. cellulose synthase-like [CSL]-F and CSL-H proteins, members of the GT2 family; Burton et al., 2006; Doblin et al., 2009). The GT61 family has been proposed as a (1,2)-β-XylT that transfers Xyl onto Araf side chains (Mitchell et al., 2007). Some GT75 members have been implicated in wall polysaccharide biosynthesis (Dhugga et al., 1997) and shown to possess UDP-Arap mutase activity that interconverts UDP-Arap and UDP-Araf (Konishi et al., 2007). To determine the DNA sequences of all wheat GT (TaGT) genes, we developed an in-house Java script to screen wheat EST databases (from The Institute for Genome Research [TIGR] and the National Center for Biotechnology Information [NCBI]). This script was successfully used to identify 34 fasciclin-like arabinogalactan proteins in wheat (Faik et al., 2006). Table I summarizes the number of ESTs identified, the number of unique contigs, the number of full-length sequences, and the number of the orthologs in the rice genome for each gene family/group described here.

Table I. List of the wheat gene sequences constructed from public EST databases using our bioinformatics script (described in Faik et al., 2006).

| Family/Group | Total ESTs | No. of Unique Contigsa | No. of Full-Length Genes | No. of Rice Orthologs |

| TaCSL-A | 30 | 5 | 3 | 9 |

| TaCSL-C | 49 | 3 | 1 | 10 |

| TaCSL-D | 20 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| TaCSL-E | 61 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| TaCSL-F | 40 | 5 | 1 | 9 |

| TaCSL-H | 17 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| TaGT8 | 184 | 20 | 7 | 39 |

| TaGT43 | 199 | 7 | 5 | 10 |

| TaGT47 | 264 | 20 | 5 | 35 |

| TaGT61 | 325 | 23 | 10 | 25 |

| TaGT75 | 631 | 4 | 4 | 6 |

Because bread wheat is hexaploid, each gene may have up to three copies. Here, we counted only one copy for each gene.

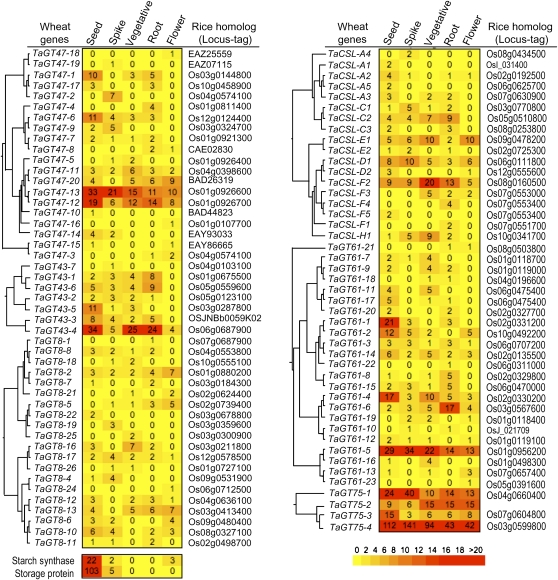

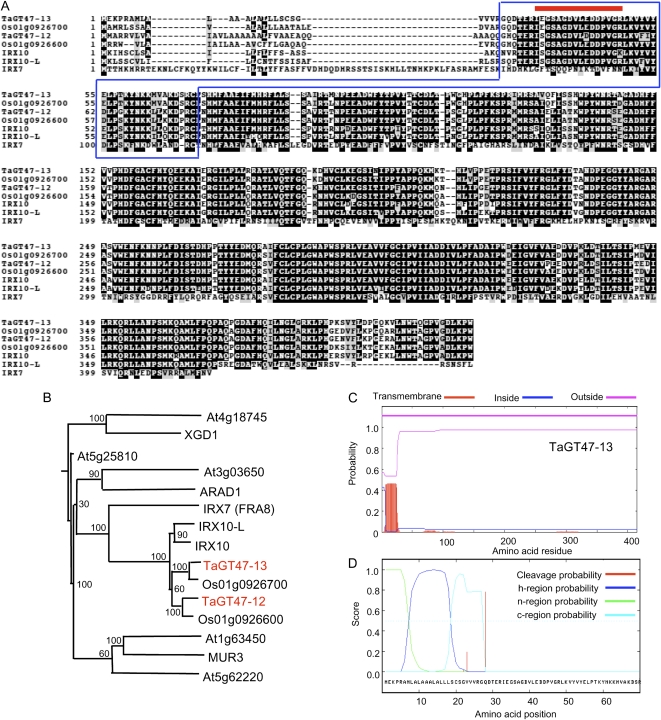

Next, we carried out a digital northern analysis (using the Wheat EST Anatomy Viewer program at TIGR) to determine which of the TaGT genes were relatively highly represented in the seed cDNA libraries (Fig. 2). The walls of the starchy endosperm tissues of the seeds are mainly composed of AX (approximately 70% [w/w]) and MLG (approximately 20% [w/w]). Thus, if a wheat GT gene is involved in AX biosynthesis, its expression would be expected to be up-regulated in seeds. In whole, the digital northern analysis presented in Figure 2 showed that the TaGT genes with the highest representation in seeds belong to the GT43, GT47, GT61, and GT75 families, and most of the TaCSL genes (with the exception of TaCSL-F2) and the TaGT8 genes appeared to be relatively underrepresented in seeds. Specifically, TaGT43-4, TaGT47-13, TaGT47-12, and TaGT75-4 genes were particularly highly represented in wheat seed cDNA libraries. More interestingly, the IEGSAGDVLEDDPVGR peptide sequence produced by proteomics analysis was a perfect match with TaGT47-13 and its orthologous rice protein Os01g0926700 (Fig. 3A). Because BLAST search and phylogenetic analysis showed that IRX7 (FRA8), IRX10, and IRX10-L proteins are the closest Arabidopsis protein homologs (Fig. 3B), we concluded that TaGT47-13 and TaGT47-12 are the functional orthologs of IRX10 and IRX10-L. TaGT47-13 protein sequence shared 92% and 83% amino acid identity with Os01g0926700 and IRX10 proteins, respectively. Arabidopsis IRX10 and rice Os01g0926700 proteins also shared 84% amino acid identity between them. Sequence alignment of these proteins supported the relatively high similarity between wheat, rice, and Arabidopsis proteins (Fig. 3A). In addition, protein sequence analysis using TMHMM2.0 and SignalP3.0 programs predicted that TaGT47-13 is lacking a membrane-anchoring transmembrane domain (TMD; Fig. 3C) and possesses a cleavable signal peptide (Fig. 3D). These predictions applied also to all the proteins from the same subgroup of the GT47 family (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Heat map representation of the relative EST counts of wheat members of the GT8, GT43, GT47, GT61, and GT75 families (CAZy database) along with six wheat cellulose synthase-like subfamilies (TaCSL-A, TaCSL-C, TaCSL-E, TaCSL-D, TaCSL-F, and TaCSL-H). The digital northern was performed using the Wheat EST Anatomy Viewer at the TIGR Web site. Because of the low EST abundance, the maximum intensity was set to 20 ESTs, allowing for better visualization of the lower EST counts. The accession numbers of rice homologs are indicated on the right. On the left of each GT family are indicated the phylogenetic trees generated with an in-house Java script (Faik et al., 2006). Bootstrap support values of 1,000 trials were used to determine the branching points. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

Figure 3.

Analysis of TaGT47-12 and TaGT47-13 protein sequences. A, Amino acid sequence alignment of TaGT47-12 and TaGT47-13 proteins with three Arabidopsis (IRX10, IRX10-L, IRX7) and two rice (Os01g0926700, Os01g0926600) proteins. The numbers on the left indicate the positions of amino acids. The line at the top of the sequence indicates the peptide sequence (IEGSAGDVLEDDPVGR) identified by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis. The boxed sequence locates the peptide sequence from TaGT47-13 used to generate the polyclonal anti-TaGT47-13 antibody. B, Phylogenetic tree of TaGT47-12, TaGT47-13, Os01g0926700, Os01g0926600, and Arabidopsis IRX10 and IRX10-L along with other Arabidopsis members of the GT47 family, namely XGD1 (At5g33290; a xylogalacturonan xylosyltransferase), ARAD1 (At2g35100; a putative arabinosyltransferase), and MUR3 (At2g20370; a xyloglucan galactosyltransferase), using an in-house Java script (Faik et al., 2006). The tree was constructed under the JTT substitution model using the PHYML program. Bootstrap support values of 1,000 trials are indicated. C, Prediction of TMDs using the TMHMM2.0 program. “Inside” is considered the cytosolic side of the membrane. D, Prediction of signal peptide cleavage sites using the SignalP3.0 program along with the scores for the n-region, h-region, and c-region of the signal peptide. According to this program, TaGT47-13 protein is predicted to have a signal peptide cleavable between amino acids 27 and 28 (VRG-QD).

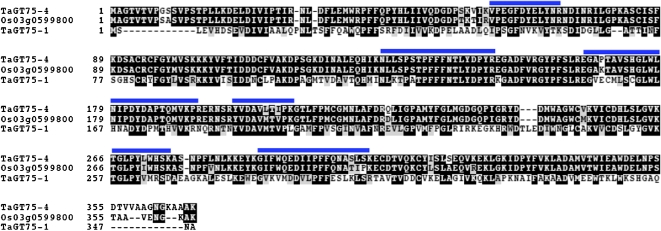

The relative EST counts of wheat members of the GT75 family (digital northern) also revealed that TaGT75-1 and TaGT75-4 genes were highly represented in seed cDNA libraries (Fig. 2). Similarly, proteomics experiments produced peptide sequences (GIFWQEDIIPFFQNATIPK, NLDFLEMWRPFFQPYHLIIVQDGDPSK, YVDAVLTIPK, TGLPYLWHSK, VPEGFDYELYNR, NLLSPSTPFFFNTLYDPYR, EGAPTAVSHGLWLNIPDYDAPTQMVKPR) that were perfect matches to wheat TaGT75-4 and its rice orthologous protein Os03g0599800 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Amino acid sequence alignment of wheat TaGT75-1 and TaGT75-4 proteins with the closest homologous protein from rice (Os03g0599800). The numbers on the left indicate the positions of amino acids. The lines at the top of the sequences indicate the seven peptide sequences identified by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis that were perfect matches with TaGT75-4 and its closest rice homolog but not with the TaGT75-1 protein. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

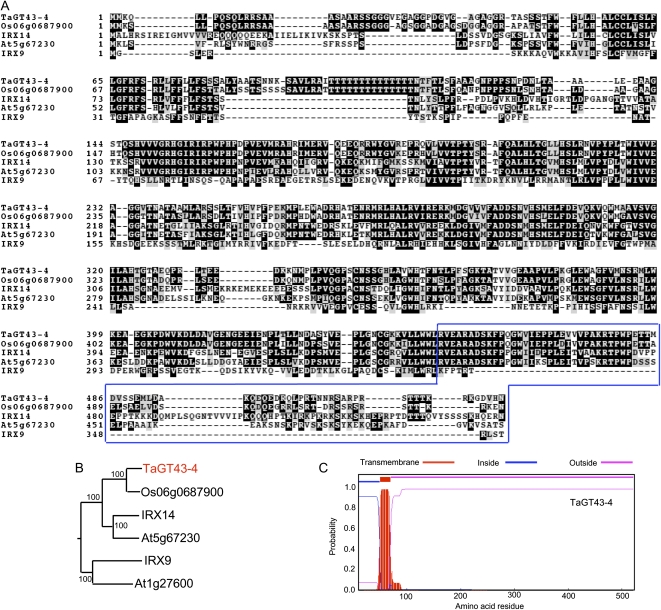

Although the proteomics strategy did not identify peptides related to TaGT43 proteins, digital northern analysis revealed that TaGT43-4 is highly represented in seed cDNA libraries (Fig. 2) and thus may be involved in AX biosynthesis. Because BLAST results and phylogenetic analysis indicated that IRX14 is the Arabidopsis protein most closely related to TaGT43-4 (Fig. 5B), we concluded that TaGT43-4 is the functional ortholog of IRX14. The rice protein orthologous to TaGT43-4 is Os06g0687900, with 83% shared identity at the amino acid level. Both wheat and rice proteins shared approximately 54% amino acid identity with Arabidopsis IRX14 protein and shared only approximately 25% amino acid identity with the Arabidopsis IRX9. Sequence alignment of these proteins supported these relative similarities between wheat, rice, and Arabidopsis proteins (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, both rice and wheat GT43 proteins are predicted to have one TMD at the N-terminal end (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Sequence analysis of the wheat TaGT43-4 protein. A, Amino acid sequence alignment of TaGT43-4 with three Arabidopsis (IRX9, IRX14, At5g67230) and one rice (Os06g0687900) proteins. The numbers on the left indicate the positions of amino acids. The boxed sequence located at the C-terminal end indicates the peptide sequence from TaGT43-4 used to generate the polyclonal anti-TaGT43-4 antibody. B, Phylogenetic tree of TaGT43-4 and its homologous proteins from Arabidopsis (IRX9, IRX14, At5g67230, At1g27600) and rice (Os06g0687900) using an in-house Java script (Faik et al., 2006). The tree was constructed under the JTT substitution model using the PHYML program. Bootstrap support values of 1,000 trials are indicated. C, Prediction of TMDs using the TMHMM2.0 program. “Inside” is considered the cytosolic side of the membrane. According to this program, TaGT43-4 protein is predicted to have a transmembrane anchoring domain between amino acids 48 and 78.

In conclusion, the combination of digital northern and proteomics experiments allowed us to identify three wheat genes, TaGT43-4, TaGT47-13, and TaGT75-4, as promising candidates for GAX biosynthesis.

Anti-TaGT43-4 Antibodies Immunoprecipitate the GAX Synthase Activity That Shows Cooperative Mechanism

Two antibodies were generated against selected regions at the C-terminal end of TaGT43-4 (boxed sequence in Fig. 3A) and the N-terminal end of TaGT47-13 (boxed sequence in Fig. 5A). Nucleotide sequences of the selected regions were heterologously expressed in Escherichia coli, and the produced peptides were purified and then used to immunize rabbits. The antibodies produced were further purified using columns made of their respective antigens (see “Materials and Methods”). Anti-TaGT43-4 antibodies are expected to be specific to TaGT43-4 protein because there is no significant sequence similarity (according to BLAST two-sequence program at NCBI) between the selected peptide sequence used to generate the antibodies and other wheat and rice proteins from the same subgroup in the GT43 family, including proteins homologous to Arabidopsis IRX9 (Fig. 5A). Similarly, anti-TaGT47-13 antibodies are specific to TaGT47-13 and TaGT47-12 proteins and would not recognize other wheat and rice proteins in the same subgroup in the GT47 family, including proteins homologous to Arabidopsis IRX7 (less than 35% shared identity with TaGT47-13; Fig. 3A).

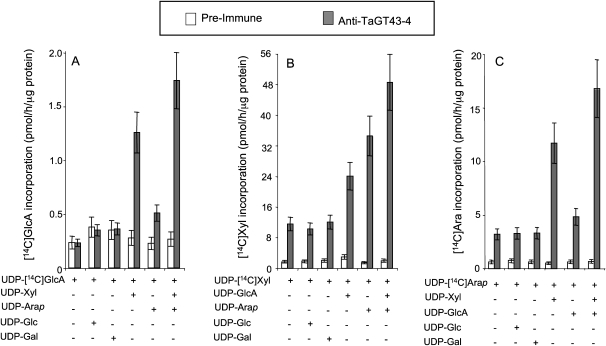

We anticipated that antibodies generated against the C-terminal region would have better accessibility to membrane proteins (such as TaGT43-4). Therefore, we choose to use anti-TaGT43-4 antibodies to carry out coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiments on detergent-solubilized proteins from Golgi-enriched membranes (at the 1.1/0.25 m Suc interface). Although both digitonin (1%) and Triton X-100 (0.5%) were efficient in solubilizing GAX synthase activity (Supplemental Fig. S2), we decided to carry out the analysis on 0.5% Triton X-100-solubilized extracts (designated TX100). These TX100 extracts were incubated with purified anti-TaGT43-4 antibodies cross-linked to a matrix, and the unbound proteins were extensively washed with buffer before eluting bound proteins (eluted fractions). The eluted fractions were then tested for GAX-XylT, GAX-AraT, and GAX-GlcAT activities. Our results showed that the eluted fractions have a GAX-GlcAT activity that incorporated [14C]GlcA from UDP-[14C]GlcA into ethanol-insoluble products in the presence of UDP-Xyl, and when UDP-Xyl was substituted with UDP-Glc or UDP-Gal, no [14C]GlcA incorporation was observed (Fig. 6A). While UDP-Arap alone has only a limited stimulatory effect on GlcAT, its combination with UDP-Xyl enhanced further the rate of [14C]GlcA incorporation compared with UDP-Xyl alone (Fig. 6A). The low incorporation of [14C]GlcA in the presence of UDP-Arap has an important implication, as it suggests that the eluted fractions did not have both UDP-Xyl 4-epimerase (UGE3; Burget et al., 2003) and UDP-Xyl synthase activities, because both activities would produce UDP-Xyl (from UGP-GlcA or UDP-Arap), which in turn would stimulate [14C]GlcA incorporation. To confirm this conclusion, the eluted fractions were incubated (under GAX synthase assay conditions) with either UDP-[14C]GlcA or UDP-[14C]Xyl, and then the reaction mixture was analyzed by high-pH anion-exchange chromatography (HPAEC) for the formation of UDP-Xyl (from UDP-GlcA) or UDP-Arap (from UDP-Xyl). As expected, we did not observe any production of UDP-Xyl or UDP-Arap from UDP-GlcA or UDP-Xyl, respectively (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Effects of various UDP-sugars on the incorporation of [14C]GlcA (A), [14C]Xyl (B), or [14C]Ara (C) into ethanol-insoluble products using the affinity-purified fractions from the anti-TaGT43-4 affinity column or from the preimmune column. Transfer reactions were carried out as described earlier (Zeng et al., 2008) and contained the affinity-purified fractions (approximately 5 μg of proteins) UDP-[14C]GlcA, UDP-[14C]Xyl, or UDP-[14C]Arap at specific radioactivity of 350, approximately 3, and approximately 3 cpm pmol−1, respectively. Details of the reaction conditions are indicated in “Materials and Methods.” Error bars represent the se of at least three biological replicates.

When GAX-XylT activity was monitored using UDP-[14C]Xyl, the inclusion of UDP-GlcA or UDP-Arap resulted in an approximately 2-fold or approximately 3-fold stimulation of [14C]Xyl incorporation, respectively (Fig. 6B). However, the presence of both UDP-GlcA and UDP-Arap resulted in even better stimulation (4-fold; Fig. 6B). As expected, the incorporation of [14C]Xyl was not enhanced by the inclusion of UDP-Glc or UDP-Gal in the reaction mixture (Fig. 6B).

GAX-AraT activity was investigated also using purified UDP-[14C]Arap (see “Materials and Methods”) as a source of 14C radiolabel in the GAX synthesis assay. Figure 6C indicates that [14C]Ara incorporation was not stimulated by the inclusion of UDP-Glc or UDP-Gal in the reaction mixture, but UDP-Xyl showed a clear stimulatory effect. On the other hand, UDP-GlcA alone had a limited stimulatory effect on [14C]Arap incorporation, but its combination with UDP-Xyl enhanced further the incorporation rate compared with UDP-Xyl alone (Fig. 6C). In all the assays, no 14C radiolabel incorporation was observed when the enzyme source was the fractions eluted from the preimmune column (Fig. 6). According to [14C]GlcA, [14C]Xyl, or [14C]Ara incorporation measured with the eluted fractions and the original TX100 fractions, only 10% of the GAX synthesis activity was retained on the affinity column. This could be explained by saturation of the column due to the limited amount of purified anti-TaGT43-4 linked to the matrix. Taken together, our results suggest that (1) the affinity-purified GAX synthesis activity involved a cooperative mechanism between GAX-XylT, GAX-AraT, and GAX-GlcAT activities, (2) the GAX synthase activity appeared to be free of sugar nucleotide-interconverting activities, and (3) coimmunoprecipitation may offer an opportunity to isolate and investigate the biochemical mechanism of other hemicellulose synthase complexes.

Affinity-Purified Fractions Contain TaGT43-4, TaGT47-13, and TaGT75-4 Proteins

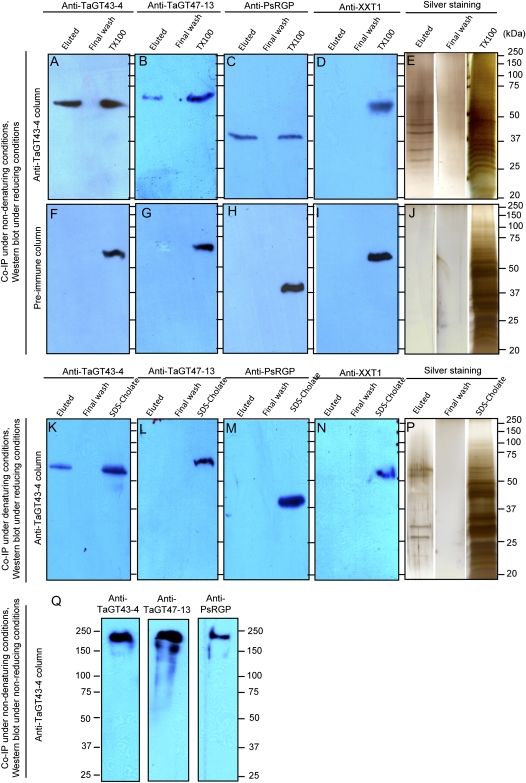

To demonstrate that TaGT43-4, TaGT47-13, and TaGT75-4 proteins are associated with the affinity-purified GAX synthase activity and interact physically, the co-IP experiments were repeated under nondenaturing (designated TX100 extracts) and denaturing conditions using a combination of 0.1% SDS and 0.5% cholate mixture (designated SDS-cholate extracts) that breaks up the quaternary structure of the complex without a complete denaturing of the polypeptides (Desprez et al., 2007). The eluted fractions (from anti-TaGT43-4 affinity or preimmune columns), the original extracts (TX100 or SDS-cholate), as well as the last step of the washing of unbound proteins (designated final wash) were then analyzed by western blot. Anti-TaGT43-4-, anti-TaGT47-13-, and anti-RGP-specific antibodies (generated against pea [Pisum sativum] protein; a gift from Dr. K. Dhugga) were used to detect the presence of TaGT43-4, TaGT47-13, and TaGT75-4 proteins, respectively. Furthermore, all fractions were analyzed for the presence of a non-xylan synthesis-related Golgi protein, XyG-xylosyltransferase (XXT). Arabidopsis XXT1, for which antibodies are available (anti-XXT1; a gift from Dr. K. Keegstra), is a Golgi-localized protein that is not related to xylan synthesis (Zeng and Keegstra, 2008). The wheat genome has a putative XXT gene (designated TaGT34-6) homolog to Arabidopsis XXT1 (At3g62720). The rice protein orthologous to XXT1 is Os03g030000. Wheat and rice proteins shared 81% amino acid identity and 64% to 71% amino acid identity with Arabidopsis XXT1. Immunoblotting data confirmed that anti-XXT1 antibodies recognized the rice Os03g030000 protein produced (as His-tagged protein) in a Pichia pastoris expression system (Supplemental Fig. S3). Therefore, we were confident that these anti-XXT1 antibodies would also recognize wheat protein (TaGT34-6).

The three antibodies, anti-TaGT43-4, anti-PsRGP, and anti-TaGT47-13, detected a single band in both TX100 extracts and the eluted fractions from the anti-TaGT43-4 column (Fig. 7, A–C). Anti-XXT1 antibodies, on the other hand, detected a single band only in TX100 extracts (Fig. 7D). Anti-TaGT43-4 and anti-TaGT47-13 recognized bands around 60 to 65 kD, while anti-PsRGP and anti-XXT1 detected bands around 40 and 55 kD, respectively (Fig. 7). Although the size of the bands detected by anti-PsRGP, anti-TaGT43-4, and anti-XXT1 agreed with the predicted size of TaGT75-4, TaGT43-4, and TaGT34-6 proteins (40, 60, and approximately 52 kD, respectively), the band detected by anti-TaGT47-13 (approximately 65 kD) was larger than its predicted size (approximately 50 kD). This could be due to protein-detergent interaction or extensive glycosylation of the protein. Because no signal bands were detected in the final wash fractions (Fig. 7, A–D and F–I), it indicates that the washing of unbound proteins was efficient. More importantly, the nondetection of signals with anti-XXT1 in the affinity-purified fraction (eluted fraction in Fig. 7D) supports the conclusion that the eluted fraction was free of certain known non-xylan synthesis-related Golgi proteins such as wheat XXT. When the preimmune serum was used in the co-IP experiments, no signal bands were detected by immunoblotting in the eluted fractions, while the TX100 extracts still showed the presence of the corresponding proteins (TaGT34-6, TaGT43-4, TaGT47-13, TaGT75-4, and TaGT34-6; Fig. 7, F–I).

Figure 7.

Immunoblot analyses of the affinity-purified complex from co-IP experiments. A to E and K to P, Co-IP was performed either under nondenaturing (A–E) or denaturing (K–P) conditions, and the proteins were separated under reducing conditions (+DTT) using standard SDS-PAGE (10% gels) followed by western-blot analyses. F to J, Co-IP experiments were performed using preimmune serum under nondenaturing conditions, and the proteins were analyzed by western blot under reducing conditions. Q, Co-IP experiments were carried out under nondenaturing conditions (Triton-solubilized proteins) using anti-TagT43-4 affinity column, and the proteins were separated under nonreducing conditions (−DTT), where SDS was substituted with 0.1% cholate on gels and proteins were not boiled. Four antibodies, anti-TaGT43-4, anti-TaGT47-13, anti-PsRGP, and anti-XXT1, were used at the appropriate dilutions. E, J, and P show analysis of protein bands by SDS-PAGE separation and silver staining. Molecular mass markers (kD) are indicated. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

Western-blot analysis of the fractions obtained from co-IP experiments performed on proteins extracted under denaturing conditions (SDS-cholate extracts) indicated that anti-TaGT43-4 was still detecting a signal band around 60 kD in the eluted fractions but no signal was detected by anti-TaGT47-13, anti-TaGT75-4, or anti-XXT1 antibodies (Fig. 7, K–N), showing that the denaturing conditions used were sufficient to dissociate the complex. Taken together, these findings suggest that the co-IP of TaGT47-13 and TaGT75-4 proteins with TaGT43-4 was not the result of a nonspecific coimmunopurification and that the three proteins physically interact with each other to form a GAX synthase core complex. However, to gain further support for this conclusion, the eluted fractions obtained under nondenaturing conditions (co-IP on TX100 extracts) were separated on polyacrylamide gels, but this time under nonreducing conditions (protein gels contained 0.1% cholate instead of SDS and no dithiothreitol [DTT], and the samples were not boiled). Figure 7Q shows that the three antibodies (anti-TaGT43-4, anti-TaGT47-13, and anti-PsRGP) detected the same band with a high molecular mass around 225 kD, indicating that the corresponding proteins comigrate as a complex. SDS-PAGE and silver staining analysis of these eluted fractions revealed the presence of limited protein bands (Fig. 7E), and no bands were stained in the eluted fractions from the preimmune column (Fig. 7J). Interestingly, eluted fractions from co-IP experiments carried out under denaturing conditions revealed the presence of four bands (Fig. 7P); two bands were around 60 kD and two other bands were around 30 to 35 kD (Fig. 7P). The two bands around 60 kD may correspond to TaGT43-4 isoforms, but the two other proteins are unknown. These results suggested that strong physical interactions exist between TaGT43-4 proteins and at least two smaller proteins.

In summary, the western-blot analyses along with enzymatic results lend support to the conclusion that the co-IP resulted in the purification of an active GAX synthase complex. Thus, in the rest of this paper, this multienzyme complex will be referred to as “affinity-purified complex.”

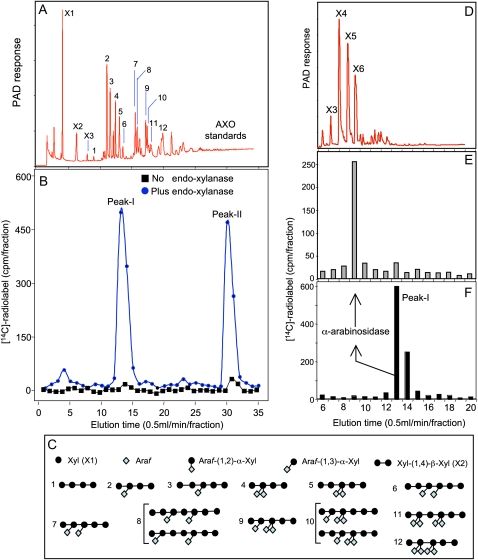

The Product Synthesized by the Affinity-Purified Complex Contains Xyl, Ara, and GlcA and Has a Regular Structure

In the next step, we sought to investigate the structure of the 14C-radiolabeled product formed by the affinity-purified complex. Thus, a 14C-radiolabeled product was generated by incubating the affinity-purified complex in the presence of UDP-[14C]Xyl (approximately 66 kBq mmol−1), UDP-[14C]Arap (approximately 66 kBq mmol−1), and UDP-[14C]GlcA (approximately 8 MBq mmol−1). This newly synthesized 14C-radiolabeled product was precipitable with cold 70% ethanol, which suggested a size that is larger than short oligosaccharides. The 14C-radiolabeled product was then analyzed by HPAEC fractionation before and after digestion with a purified and well-characterized endoxylanase III (GH11 family) from Aspergillus niger, and 14C radiolabel distribution was compared with the distribution of authentic AX oligosaccharides (AXOs) used as standards (Fig. 8, A and C). The endoxylanase III was free of hydrolase activities when tested on XyG, galactomannan, cellulose, gum arabic, and two pectins (rhamnogalacturonan and polygalacturonan) but showed approximately 10% activity against MLG (see “Materials and Methods”). However, since the affinity-purified complex does not incorporate [14C]Glc into ethanol-insoluble products (i.e. MLG; data not shown), the endoxylanase III was used without further purification.

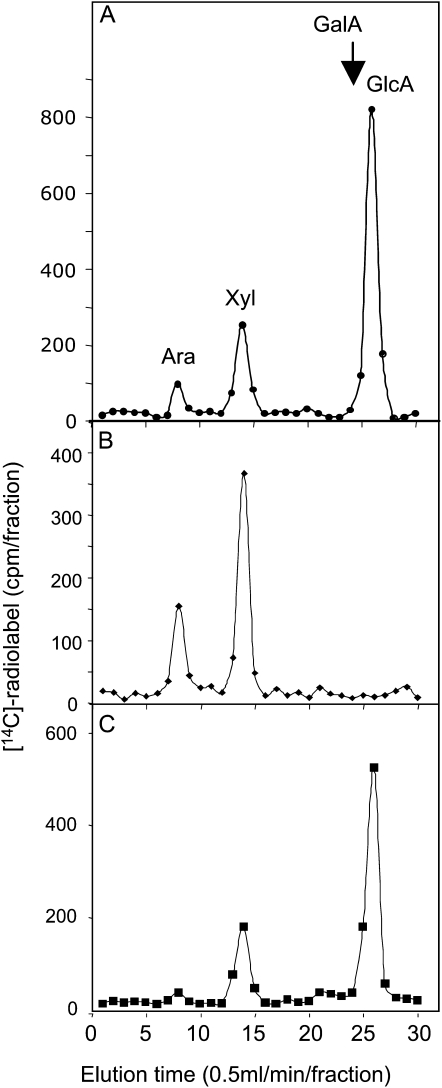

Figure 8.

Analysis of the [14C]GAX product formed by the affinity-purified complex. Ten glycosyl transfer reactions were combined to generate the [14C]GAX product (20,000 cpm), and each reaction (60 μL) contained the affinity-purified complex (50 μL, approximately 5 μg of proteins), UDP-[14C]GlcA (approximately 4.4 μm, approximately 8 MBq mmol−1), UDP-[14C]Xyl (approximately 0.75 mm, approximately 66 kBq mmol−1), and UDP-[14C]Arap (approximately 0.75 mm, approximately 66 kBq mmol−1). A, Typical HPAEC fractionation profiles of authentic oligosaccharides from wheat arabinoxylans (AXO standards) released by endoxylanase III. AXO standards are numbered from 1 to 12. B, Distribution of the 14C radiolabel released from the 14C product before and after endoxylanase III treatment on a CarboPac PA200 column as described by Zeng et al. (2008). The 14C radiolabel was monitored each minute at 30°C and eluted as two peaks around 13 min (peak I) and around 30 min (peak II). C, Schematic presentation of the chemical structures of AXO standards. D, Typical HPAEC separation of xylooligosaccharide series. E, Distribution of the 14C radiolabel released from [14C]peak I after treatment with α-l-arabinofuranosidase from Bifidobacterium species (Megazyme). X1 and X2 (in A) and X3, X4, X5, and X6 (in D) stand for Xyl, xylobiose, xylotriose, xylotetraose, xylopentaose, and xylohexaose, respectively. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

Fractionation data indicated that endoxylanase treatment released the 14C radiolabel as two peaks: peak I eluted around 13 min and peak II eluted around 30 min (Fig. 8B). 14C radiolabel in peak I coeluted with the AXO standard 6 (Fig. 8A), which contains six Xyl and two Ara residues (Fig. 8C). However, 14C radiolabel in peak II did not correspond to any of the known AXO standards, and detailed analysis will be required to determine its structure. These peaks (oligosaccharides) were absent in the HPAEC fractionation profile obtained from undigested 14C-radiolabeled product (Fig. 8B), which further confirmed that the newly synthesized 14C-radiolabeled product had a size larger than oligosaccharides. Additional confirmation of the structure of peak I was obtained by treating [14C]peak I with an α-l-arabinofuranosidase from Bifidobacterium species (Megazyme). The resulting fragments were analyzed again by HPAEC and showed that the 14C radiolabel coeluted as a single peak with the authentic xylohexaose (X6; Fig. 8, D and E). Furthermore, the 14C radiolabel eluted under peak X6 was solely associated with [14C]Xyl (after total acid hydrolysis, 2 m trifluoroacetic acid [TFA]; data not shown). These data demonstrate that peak I is indeed a GAX oligosaccharide containing six Xyl and two Ara residues.

The newly synthesized 14C-radiolabeled product along with peak I and peak II were also subjected to monosaccharide composition analysis by total acid hydrolysis (2 m TFA) and fractionation on a CarboPac PA20 column (Dionex). The results showed that all 14C-labeled monosaccharides from the newly synthesized 14C-radiolabeled product was recovered as [14C]Xyl, [14C]Ara, and [14C]GlcA residues in a ratio of 45:12:1, respectively (Fig. 9A), and no radioactivity coeluted with GalUA (GalA) under these conditions (Fig. 9A). 14C-labeled monosaccharides from peak I eluted as [14C]Xyl and [14C]Ara in a molar ratio of approximately 2.7:1, respectively (Fig. 9B), which fits the predicted composition of the AXO standard 6 (Fig. 8C). The hydrolysis of peak II, on the other hand, yielded Xyl, Ara, and GlcA in a ratio of 40:8:1, respectively (Fig. 9C), which may suggest a larger oligosaccharide.

Figure 9.

Monosaccharide composition analysis of [14C]GAX product (A), [14C]peak I (B), and [14C]peak II (C). Distribution of the 14C radiolabel as monosaccharides after total acid hydrolysis (2 m TFA) and fractionation of the hydrolysate on a CarboPac PA20 column (Dionex) were as described earlier (Zeng et al., 2008).

In summary, these results demonstrated that the affinity-purified complex produced, in vitro, a GAX polymer that has a regular structure, as endoxylanase III treatment released only two oligosaccharides. In addition, no 14C radiolabel was released as xylobiose (X2), xylotriose (X3), or xylotetraose (Fig. 8B), indicating the absence of long stretches of unbranched Xyl residues in the nascent GAX polymer. The ratio of Xyl to Ara (approximately 3:1) was in agreement with our previously published data (Zeng et al., 2008); however, the newly synthesized GAX polymers had a ratio of Xyl to GlcA (45:1) higher than our previous data. This discrepancy is unlikely to be the result of the presence of two synthase complexes, XylT/AraT and XylT/GlcAT, in the affinity-purified complex but rather to either an incomplete digestion of the polymer or incomplete synthesis during GAX synthesis reactions.

TaGT43-4, TaGT47-13, and TaGT75-4 Are Highly Expressed in Developing Wheat Endosperm

The deposition of AX and MLG polymers is well coordinated during endosperm development (Drea et al., 2005; Philippe et al., 2006). Thus, if a wheat GT gene is involved in AX biosynthesis, its expression would coincide with developmental stages corresponding to endosperm wall elaboration and AX biosynthesis. Therefore, we sought to investigate whether the expression of TaGT43-4, TaGT47-12, TaGT47-13, TaGT75-1, and TaGT75-4 genes is up-regulated in developing endosperm in wheat seeds, which would suggest involvement in endosperm cell wall elaboration.

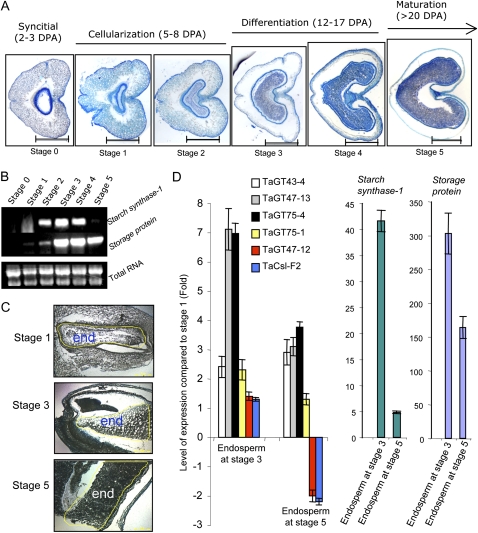

Using light microscopy, we visually monitored endosperm developmental status during seed development. For the purpose of this study, the endosperm developmental process was divided into a number of convenient stages (numbered from 0 to 5). At stage 0, the endosperm is at the syncytial stage, characterized by the multinucleate syncytium structure, which is usually observed in seeds in the first 3 d after anthesis (Fig. 10A). At stages 1 and 2, the endosperm cells are actively dividing (corresponding to endosperm cellularization), which occurs between 5 and 8 d after anthesis (Fig. 10A). Stages 3 and 4 correspond to the beginning and the end of endosperm differentiation, with the starchy endosperm having extended cells that are rapidly accumulating starch grains and storage proteins as judged by the increase in the size of the endosperm. Stages 0 to 4 are characteristic of approximately 2-week-old seeds (Fig. 10A). Finally, in stage 5, the endosperm occupies most of the seed and enters the maturation stage (Fig. 10A), which is characteristic of 21- to 25-d-old wheat seeds. Using semiquantitative one-step RT-PCR, expression patterns of two wheat endosperm-specific genes, namely the granule-bound starch synthase I (Wx-DI; accession no. AF163319) and Avenin-like storage protein (accession no. AF470351) genes, were investigated to confirm the observed developmental stages. The granule-bound starch synthase I and Avenin-like storage protein genes were up-regulated during the end of cellularization and the beginning of differentiation of the endosperm (Fig. 10B, stages 2–4), as expected.

Figure 10.

Relative determination of wheat seed developmental stages. The developmental process was divided into six stages (numbered 0–5). A, Light microscopy using transverse sections stained with toluidine blue of seeds at each developmental stage along with relative timing (DPA) indicated on the top of each stage. Bars = 1 mm. B, The expression patterns of two endosperm-specific wheat genes, starch synthase-1 and storage protein, using semiquantitative RT-PCR experiments. Total RNA was used as a loading control. C, Laser-capture microdissection of longitudinal sections of wheat seeds used to prepare endosperm tissues (indicated by “end”) for RNA extraction. D, Changes in the expression levels, as measured by quantitative RT-PCR, of the eight wheat genes (TaGT43-4, TaGT47-12, TaGT47-13, TaGT75-1, TaGT75-4, TaCSL-F2, starch synthase-1, and storage protein) in developmental stages 3 and 5 compared with stage 1 (set to 1). The concentration of the primers was 300 nm, and the RNA concentration was adjusted so that the cycle threshold for 18S RNA was approximately 16 for each stage. Error bars represent the se of at least two biological replicates. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

Next, we isolated endosperm tissues from three developmental stages corresponding to the beginning (stage 1), middle (stage 3), and end (stage 5) of endosperm development using laser microsectioning techniques (Fig. 10C). We then investigated the relative expression levels of TaGT43-4, TaGT47-12, TaGT47-13, TaGT75-1, and TaGT75-4 genes along with three control genes (TaCSL-F2, starch synthase-1, and storage protein) in these stages using quantitative RT-PCR. As expected, both starch synthase-1 and protein storage genes were largely up-regulated in the endosperm at stage 3 relative to stages 1 and 5 (with stage 1 set to 1 in Fig. 10D). Both TaCSL-F2 and TaGT47-12 had similar expression patterns, as their expression slightly increased in stage 3 but was down-regulated in stage 5 (Fig. 10D). On the other hand, transcript levels of TaGT47-13 and TaGT75-4 genes were strongly up-regulated (compared with stage 1) in the endosperm at developmental stages 3 (approximately 7-fold) and 5 (approximately 3-fold; Fig. 10D). This similarity in expression patterns of TaGT47-13 and TaGT75-4 is also compatible with the possible involvement of these genes in the same process.

DISCUSSION

Despite the fact that GAXs are one of the most abundant components of the primary cell walls in growing tissues in grasses, their biosynthetic mechanism at the biochemical level is still not completely elucidated and the isolation of a purified GAX synthase complex in its active form is still elusive. Thus, in this work, our goal was to combine three strategies (protein fingerprinting, bioinformatics, and biochemistry) to identify and link the potential candidate GTs to GAX biosynthase activity in wheat. Our investigation revealed three wheat genes as the most promising candidates, namely TaGT43-4, the closest homolog to Arabidopsis IRX14 (Fig. 3B), TaGT47-13, the closest homolog to Arabidopsis IRX10 and IRX10-L (Fig. 5B), and TaGT75-4. Mitchell et al. (2007) identified also rice homologs to these genes as candidates but not members of the GT75 family. In dicots, genetic studies have also shown the involvement of these members of the GT43 and GT47 families in GX biosynthesis but not GT75 members.

To experimentally link TaGT43-4, TaGT47-13, and TaGT75-4 proteins to wheat GAX synthase activity, we generated and purified specific antibodies against TaGT43-4 and TaGT47-13 proteins and carried out co-IP experiments. Using anti-TaGT43-4 antibodies, GAX synthase activity was immunopurified and TaGT47-13 and TaGT75-4 proteins were coimmunoprecipitated along with TaGT43-4. Since TaGT43-4 clustered with Arabidopsis IRX14, a protein that is required for xylan backbone synthesis of GX (Brown et al., 2007), it is conceivable that TaGT43-4 may have the same function in GAX synthesis in wheat. Also, given the fact that TaGT47-13 clustered with two Arabidopsis IRX proteins (IRX10 and IRX10-L) involved in GX synthesis, its co-IP with the GAX synthase activity is not surprising and may provide a direct link between TaGT47-13 and GAX synthesis. Recently, Konishi et al. (2007, 2010) provided evidence that some RGPs (GT75 family) are UDP-Arap mutases. Thus, close interactions with the GAX synthase complex are required to channel UDP-Araf to GAX-AraT enzyme. This report directly links RGPs to GAX biosynthesis and supports their mutase function. Although Porchia et al. (2002) reported reversible arabinosylation of a 41-kD protein (presumably an RGP) during their study on AX biosynthesis in wheat, no direct association with the activity was provided. Langeveld et al. (2002) identified also the TaGT75-4 gene in wheat endosperm and demonstrated that it was not involved in starch biosynthesis.

Several lines of evidence support the notion that TaGT43-4, TaGT47-13, and TaGT75-4 interact physically to form a complex. First, under native conditions, both TaGT47-13 and TaGT75-4 proteins coimmunopurified with TaGT43-4. Second, the three proteins comigrated in a similar way under different western-blot conditions. For example, separation of the eluted fractions on protein gels under nonreducing conditions showed that the three proteins comigrated with the same high molecular mass band around 225 kD (Fig. 7Q). Similarly, the three proteins comigrated (along with some of the GAX synthase activity) to a lower density during EDTA-supplemented Suc gradient separation and fractionated in the same fractions (fractions 2 and 3 in Fig. 1, C′ and E). The presence of the three proteins in fractions 2 and 3 was confirmed by immunoblot analysis (data not shown). Third, co-IP experiments carried out on proteins extracted under denaturing conditions (0.1% SDS and 0.5% cholate) did dissociate the complex (Fig. 7, K, L, and M). These denaturing conditions were also proven to be efficient in breaking protein-protein interactions between CESA subunits within the cellulose synthase complex in Arabidopsis (Desprez et al., 2007). More importantly, the physical interaction between TaGT43-4, TaGT47-13, and TaGT75-4 appears to be necessary because TaGT47-13 is predicted to have no TMD and has a cleavable signal peptide (Fig. 3, C and D). Consequently, close interactions of TaGT47-13 with one or several GT-anchored Golgi proteins (such as TaGT43-4, which is predicted to be anchored to the Golgi membranes by one TMD located at the N terminus; Fig. 5C) are a likely requirement to maintain Golgi localization. In this work, the copurification of TaGT47-13 with TaGT43-4 confirms this prediction. Similarly, RGPs (GT75 family) are predicted to be soluble proteins with no signal peptide sequence. Thus, close interactions with the GAX synthase complex are also required to maintain Golgi localization. Again, the co-IP results showed that TaGT75-4 copurified with GAX synthase activity, confirming these predictions. Further analysis, however, is needed to determine whether GT75-4 protein interacts directly with TaGT43-4 and/or TaGT47-13 proteins or indirectly via other unknown membrane proteins. Interestingly, SDS-PAGE and silver staining analysis indicated the presence of several bands in the affinity-purified complex (Fig. 7, compare E, J, and P). Some of these proteins may play a role in the assembly of the GAX synthase complex without any enzymatic activity. Further investigations are needed to determine the stoichiometry of these proteins in the GAX synthase complex and their topology. However, because the denaturing conditions used were sufficient to dissociate the complex without the need of any reducing agent, noncovalent bonds contribute to stabilizing the complex.

The biosynthesis of GAX (in vivo) would also involve other activities, such as UDP-Xyl synthase and UGE3, to produce the necessary precursors: UDP-Xyl and UDP-Ara. This work does not provide support for any association between the GAX synthase complex and UGE3 or UDP-Xyl synthase, which may suggest that these enzymes are most likely weakly associated with the GAX synthase complex.

This work confirms the cooperative mechanism previously observed with microsomal membranes (Zeng et al., 2008), indicating that wheat GAX synthesis proceeds by concomitant synthesis of xylan backbone and the addition of Ara and GlcA substituents. A similar cooperative mechanism was described in the case of XyG biosynthesis. Neither pea nor soybean (Glycine max) microsomal membranes could make XyG polymers without the presence of both UDP-Glc and UDP-Xyl (Ray, 1980; Hayashi and Matsuda, 1981; Gordon and Maclachlan, 1989; White et al., 1993; Faik et al., 2002). Furthermore, the cooperative mechanism often results in the formation of a polymer with a regular structure. For example, the newly synthesized XyG polymer has a basic repeating unit of four Glc and three Xyl residues (Ray, 1980; Gordon and Maclachlan, 1989). Similarly, the newly synthesized GAX polymer produced by the affinity-purified complex appeared to have a regular structure with a basic unit of six Xyl and two Ara residues (Fig. 8). The GlcA-containing oligosaccharide (peak II) observed could be a variation of peak I with additional substitutions. Examples in the literature (Carpita and Whittern, 1986; Vietor et al., 1994; Zeng et al., 2008) indicated that heteroxylans from the grasses are synthesized as highly substituted polymers. In this study, however, the affinity-purified complex produced a GAX polymer with a ratio of Xyl to Ara of only 3:1, which may suggest the existence of other GTs that incorporate additional Ara or GlcA to the “arabinosyl-Xyl” backbone produced by the GAX synthase complex. However, the possibility remains that by modifying the concentrations of sugar nucleotide precursors, the GAX synthase complex could generate, in vivo, a polymer that is highly substituted.

Although the affinity-purified complex had GAX-XylT, GAX-AraT, and GAX-GlcAT activities, directly connecting these activities to TaGT43-4 or TaGT47-13 proteins was not possible. Definitive proof of function would still require a demonstration of the biochemical activity of individual proteins in vitro, which might be problematic, especially if a cooperative mechanism is involved. However, our hypothesis is that TaGT43-4 protein is the XylT responsible for the synthesis of the xylan backbone of GAX polymers, and since the affinity-purified GAX synthase activity produces arabinosylated xylan polymer, the most logical function of TaGT47-13 is GAX-AraT. These biochemical functions are supported by the following observations: (1) GX from the Arabidopsis mutant irx14 shows a drastic reduction in xylan chain length (Pena et al., 2007); (2) microsomes from irx14 mutant plants have reduced capacity to transfer Xyl from UDP-Xyl onto xylooligosaccharide acceptors (Brown et al., 2007); (3) microsomes from the irx7 mutant (a member of the GT47 family) have XylT activity comparable to the wild type (Brown et al., 2007); and (4) the inverting mechanism of GT43 and GT47 families is compatible with both XylT and AraT requirements. In addition, the presence of an Arabidopsis putative AraT gene (At2g35100, called ARAD1) involved in the biosynthesis of pectic (1,5)-α-arabinan (Harholt et al., 2006) may give additional support to the possibility of a GAX-AraT gene being among the GT47 members. However, it is possible that proteins other than TaGT43-4 and TaGT47-13 catalyze these activities but were not identified by our methods.

In conclusion, this study extends our understanding of xylan biosynthesis, as it directly links members of the GT43 and GT47 families to the GAX synthase activity in grasses. Understanding how xylan polymers are synthesized in grasses could lead to many economically important applications, including improved utilization of cereal hemicelluloses and cereal grains (Faik, 2010). We show in this work that the transcripts of TaGT43-4, TaGT47-13, and TaGT75-4 genes are highly represented in endosperm tissues and could be good targets for improving the digestibility of the cell walls of these tissues.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and Kits

UDP-[14C]GlcA (6.67–11.58 GBq mmol−1) and UDP-[14C]Glc (11.21 GBq mmol−1) were purchased from MP Biomedicals, and UDP-[14C]Xyl (9.76 GBq mmol−1) was from NEN PerkinElmer. UDP-Xyl and UDP-Arap were from CarboSource (Complex Carbohydrate Research Center, University of Georgia [http://cell.ccrc.uga.edu/ approximately carbosource/CSS_items.html]). A solution of purified endoxylanase III from Aspergillus niger (323 μg mL−1, specific activity = 18 units mg−1 protein) and the authentic AXO standards were gifts from Dr. Henk Schols. This endoxylanase was tested on several polysaccharides and found to be free of activities (less than 0.5% of the control) against XyG, galactomannan, rhamnogalacturonan, cellulose, polygalacturonan, and gum arabic but showed some activity against MLG (10% of the control). The authentic AXO standards were prepared by digesting 20 mg of wheat (Triticum aestivum) arabinoxylan with endoxylanase III (0.012 units) for 16 h. Dowex 1-X80 resin and all the chemicals were purchased from Sigma. Nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose resin, plasmid maxiprep, and gel extraction kits were purchased from Qiagen. Highly purified monoclonal (albumin free) anti-6×His tag antibodies were purchased from Clontech. Immobilon-PSQ transfer membranes were purchased from Millipore. Protein concentrations were determined by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad) using bovine serum albumin as the standard. Silver staining kit PlusOne was purchased from GE Healthcare. Precision Plus Protein weight markers (Kaleidoscope) were purchased from Bio-Rad. Arcturus PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit (MDS Analytical Technologies) was used to extract total RNA from microdissected tissues.

UDP-[14C]Arap was prepared from UDP-[14C]Xyl using recombinant Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) UGE3 gene expressed in bacteria as His-tagged protein (a gift from Dr. Wolf-Dieter Reiter). Purified UGE3 (1–3 μg) was incubated with UDP-[14C]Xyl in 50 mm HEPES buffer, pH 7, for 5 min at room temperature. After denaturing UGE3 at 65°C (10 min), the mixture contained equal amounts of UDP-[14C]Arap and UDP-[14C]Xyl.

GAX Synthase Activity Assays

The assays were conducted as described earlier (Zeng et al., 2008) with minor modifications. To monitor [14C]GlcA incorporation, UDP-[14C]GlcA (approximately 4.4 μm, approximately 8 MBq mmol−1) was used as a source of 14C radiolabel, and cold UDP-Xyl and UDP-Arap were included in the assay at approximately 0.75 mm.

When monitoring [14C]Xyl incorporation during GAX synthesis, UDP-[14C]Xyl (approximately 0.75 mm, approximately 66 kBq mmol−1) was supplied to the reaction mixture containing cold UDP-GlcA (approximately 4.4 μm) and cold UDP-Arap (approximately 0.75 mm). Similarly, when monitoring GAX-AraT activity, purified UDP-[14C]Arap (approximately 0.75 mm, approximately 66 kBq mmol−1) was included in the reaction as 14C radiolabel source. As indicated above, UDP-[14C]Arap was generated from UDP-[14C]Xyl by the action of UGE3. UDP-[14C]Arap was then purified from the UDP-[14C]Arap and UDP-[14C]Xyl mixture after fractionation on a CarboPac PA10 (Dionex) using an isocratic concentration of 100 mm ammonium formate as described earlier (Zeng et al., 2008). The 14C radiolabel incorporation in products was estimated by counting the cpm in a liquid scintillation counter (Beckman Coulter LS 6500) after resuspending the pellets in 300 μL of water and mixing with 3 mL of scintillation fluid (Fisher).

When preparing large amounts of [14C]GAX polymer for structural analysis, the mixture UDP-[14C]Arap and UDP-[14C]Xyl (1:1 ratio) was directly included in the reaction mixture containing UDP-[14C]GlcA.

Partial Purification and Solubilization of GAX Synthase Activity

Crude wheat microsomal membranes were prepared as described earlier (Zeng et al., 2008). These membranes (protein content of approximately 5 μg μL−1) can be stored at −80°C until later use or fractionated further on a continuous Suc density gradient. The continuous gradient was carried out using a linear 25% to 40% (w/v) Suc density gradient (20 mL, made up in 0.1 m HEPES-KOH, pH 7) in the absence or presence of 1 mm EDTA. Wheat enriched Golgi membranes (1 mL) were loaded on top of this linear Suc gradient. After ultracentrifugation at 100,000g for 10 h at 4°C (Beckman Coulter SW32 rotor), 22 fractions (1 mL each) were collected from the top of the gradient. Each fraction was tested for Suc density, protein content, marker enzyme activities, and GAX synthase activity. Marker enzyme activities were measured according to Turner et al. (1998) with minor modifications. Triton-dependent IDPase (a Golgi membrane marker) was determined by using 100-μL membranes diluted in 0.9 mL of 50 mm Tris buffer containing 3 mm IDP, 1 mm MgCl2, and 0.01% Triton X-100. The reaction was incubated at room temperature for 1 h and stopped by 1 mL of 20% TCA, and the phosphate released was determined according to Taussky and Shorr (1952). Antimycin A-insensitive NADH-cytochrome c reductase activity (endoplasmic reticulum maker) was measured by mixing 50-μL membranes with 0.913 mL of 50 mm potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, containing 0.2 mm NADH, 0.02 mm oxidized cytochrome c, and 10 mm KCN and measuring the change in the A550. Callose synthase (GSII; plasma membrane marker) was measured according to Dhugga and Ray (1994). Protein content was estimated using Bradford reagent (Sigma) using a standard curve made of various bovine serum albumin concentrations.

Five detergents were tested for the ability to solubilize GAX synthase activity: digitonin, CHAPS, Triton X-100, cholate, and Nonidet P-40. Wheat enriched Golgi membranes containing GAX synthase activity (1.1/0.25 m Suc interface) were incubated with detergent at various concentrations on ice for 10 min, and then the detergent-soluble fraction was separated from the detergent-insoluble pellets (residual membranes) by ultracentrifugation (Sorvall RC M120) for 45 min at 100,000g at 4°C. Residual membranes were resuspended in the same volume of extraction buffer. Both detergent-soluble fractions and residual membranes were assayed for GAX synthase activity (Supplemental Fig. S2).

Proteomics Analysis

Proteomics analysis was carried out at the Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Facility (http://www.ccic.ohio-state.edu/MS/) at the Campus Chemical Instrument Center of Ohio State University. Membranes in fractions 2 and 3 (from EDTA-supplemented linear Suc density gradient) were combined and precipitated with TCA-acetone or chloroform-methanol. Protein pellets were sent to the Campus Chemical Instrument Center facility (See Supplemental Materials and Methods S1 for experimental details, see Supplemental Fig. S1).

SDS-PAGE (under Reducing and Nonreducing Conditions) and Western-Blot Analyses

For SDS-PAGE separation, proteins were treated under reducing conditions (boiled in the presence of the reducing agent DTT and SDS) or nonreducing conditions (no boiling and no reducing agent DTT was included in loading buffer) and separated by standard SDS-PAGE on a 7.5% or 10% gel. Under nonreducing conditions, SDS was substituted by 0.1% sodium cholate (an anionic nondenaturing detergent) on the stacking and separating gels to facilitate the mobility of protein complexes.

For immunoblotting, proteins were transferred from polyacrylamide gels onto Immobilon membranes (Millipore) using the Mini Protean3 system according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Both purified anti-TaGT43-4 and anti-TaGT47-13 antibodies were used at 1:2,000 dilution. Anti-XXT1 (a gift from Dr. Kenneth Keegstra, Michigan State University) was used at 1:2,000 dilution, and anti-PsRGP (a gift from Dr. K. Dhugga) was used at 1:10,000 dilution. Anti-XXT1 antibodies were generated against the region between amino acids 45 and 191 of Arabidopsis XXT1 (designated fragment A in Supplemental Fig. S3). Anti-XXT1 antibodies were further purified on Affi-gel Protein Agarose beads (Bio-Rad), and their specificity was determined by western blotting using purified fragment A and Arabidopsis microsomal membranes. To confirm that purified anti-XXT1 would recognize wheat (TaGT34-6) and rice (Oryza sativa; Os03g030000) homologous proteins to Arabidopsis XXT1 protein, a 6×His-tagged version of Os03g030000 was produced in Pichia pastoris as described earlier (Faik et al., 2002) and used in western-blot analysis (Supplemental Fig. S3). The secondary antibodies, consisting of goat anti-rabbit IgG-peroxidase, were used at 1:5,000 dilution. West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Thermo Scientific) was used to detect protein bands.

For protein visualization, the gels were silver stained according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (GE Healthcare).

HPAEC Analysis

The samples (14C-radiolabeled oligosaccharides or monosaccharides) were analyzed by HPAEC as described earlier (Zeng et al., 2008) using either a CarboPac PA20 column for monosaccharides or a CarboPac PA200 column for oligosaccharides. The columns were connected, in series with a CarboPac PA guard column (3 × 25 mm; Dionex), to a BioLC system using a pulse amperometic detection system (ED50 electrochemical detector; Dionex). Known monosaccharides were treated under the same conditions and used as standards. Under these conditions Ara, Xyl, GalA, and GlcA standards eluted around 7, 13, 24, and 26 min, respectively.

14C-radiolabeled oligosaccharides were prepared by treatment with endoxylanase III from A. niger (0.012 unit of purified enzyme) in 50 mm sodium acetate, pH 5, for 16 h at 40°C (Kormelink et al., 1993). The reactions were stopped by boiling for 10 min and centrifuging to remove insoluble materials before further analysis by HPAEC. Similarly, the composition of peak I (Fig. 9B) was analyzed by digestion with 7 units of α-l-arabinofuranosidase (specific activity = 28.3 units mg−1 protein, 200 units mL−1) from Bifidobacterium species (E-AFAM2; Megazyme) in 100 mm sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.5, for 16 h at 40°C. The reactions were stopped by boiling for 10 min and centrifuged to eliminate insoluble material before further analysis by HPAEC of the soluble oligosaccharides (in the supernatant).

Production and Purification of Anti-TaGT43-4 and Anti-TaGT47-13 Polyclonal Antibodies

Anti-GT47 antibody was generated against a 47-amino acid peptide at the N terminus of the TaGT47-13 protein (between the 28th and 70th amino acid residues), and the corresponding nucleic acid sequence was cloned by PCR using the forward primer 5′-CCTGGATCCCCCAGGACACCGAGAGGATCGAAG-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-CCCGAATTCCCTGGAGTCCTTGGCCACCATC-3′. Anti-GT43 antibody was generated against a 43-amino acid peptide at the C terminus of the TaGT43-4 protein (between the 450th and 526th amino acid residues), and the corresponding nucleic acid sequence was cloned via PCR-based strategy using the forward primer 5′-CCTGGATCCCCCGTGTTGAAGCCCGGGCCGAC-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-CCCGAATTCTCAGTTGTGGACGTCGCCCTTCC-3′. PCR products were inserted into pGEX-5X-1 vector (Amersham Biosciences) using BamHI and EcoRI sites (underlined in primer sequences). The constructs were transformed into Escherichia coli (BL21) competent cells (Invitrogen), and the peptides were produced as glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-peptide fusion by induction with 0.1 mm isopropylthio-β-galactoside at 30°C for 5 h. GST-peptides were solubilized in phosphate buffer containing 1.5% Sarkosyl (Acros) and 1% Triton X-100 (LabChem) and allowed to attach on the glutathione-agarose column (Sigma). After washing to remove unbound GST-peptides, the peptides were released by the action of the Factor Xa protease (Amersham Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The purified peptides were used to immunize rabbits (two rabbits per peptide) at Cocalico Biologicals.

Upon reception of the sera, the antibodies were tested for their titers and then purified on their respective truncated proteins (linked to AminoLink Plus resin). For this purpose, His-tagged versions of the truncated proteins (TaGT43 or TaGT47) were produced in E. coli (BL21) using pET28a vector (Novagen), purified on a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose column, and then cross-linked to AminoLink Plus resin (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The affinity-purified antibodies were tested for their specificity on the truncated proteins using western blotting. Each antibody recognized only its own antigen (no cross-reaction between the two antibodies), and both detected a single band in total wheat protein extracts.

co-IP Experiments

Purified anti-TaGT43 antibody (100 μg of protein) was chemically cross-linked to Protein A-agarose resin (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, this anti-TaGT43-affinity column was calibrated in 400 μL of extraction buffer (0.1 m HEPES-KOH, pH 7.0, 0.4 m Suc, 1 mm DTT, 5 mm MgCl2, and MnCl2) containing 0.5% detergent used to solubilize the GAX synthase activity.

Detergent-solubilized extract containing GAX synthase activity was incubated with anti-TaGT43-affinity column for 5 h at 4°C under gentle rotation. After washing with extraction buffer containing 0.5% detergent (until no activity was found in washing fractions), the column was eluted with 160 μL of elution buffer containing primary amine (Gly), pH 2.8, directly into tubes containing 1 m Tris, pH 9.5, to neutralize the pH. The affinity-purified fractions (160 μL) were tested for GAX synthase activity and analyzed for protein composition by PAGE (under reducing and nonreducing conditions; see above) and western blotting using purified anti-TaGT43, anti-TaGT47, and anti-PsRGP antibodies.

Transcriptomics-Based Identification of Putative TaGT Genes and Phylogenetic Analysis

We developed two in-house scripts, one used to screen wheat transcriptomes and the second for phylogenetic analysis (Faik et al., 2006). The script that screens the transcriptome performs a TBLASTN (NCBI) search using rice and Arabidopsis GT protein sequences as queries. For simplicity, we are using CAZy nomenclature to designate TaGT genes. For example, wheat GT gene is designated by TaGTx-y, where x indicates the CAZy GT family to which the wheat gene belongs and y is a number that we attributed to each of our genes within the same family. The script used for phylogenetic analysis is described by Faik et al. (2006). The phylogenetic tree was then visualized with TreeView software.

Electronic Expression Pattern (Digital Northern)

The digital northern analysis was carried out using Wheat EST Anatomy Viewer (http://www.tigr.org/tdb/e2k1/tae1/wheat_digital_northern_search.shtml) at TIGR (unfortunately, this project is no longer supported by the J. Craig Venter Institute). The total ESTs in each of the wheat libraries (as of November 2008) were as follows: root (87,907 ESTs), seed (203,877 ESTs), spike (132,128 ESTs), vegetative (234,215 ESTs), and flower (71,395 ESTs). EST counts were converted into heat maps using online software at http://bbc.botany.utoronto.ca/ntools/cgi-bin/ntools_heatmapper.cgi.

Light Microscopy

Developing wheat seeds were collected and sorted by weight (mg seed−1) into six stages according to fresh weight per seed: stage 0 (1–7 mg), stage 1 (8–15 mg), stage 2 (16–20 mg), stage 3 (21–25 mg), stage 4 (26–35 mg), and stage 5 (36–45 mg). Fresh seeds were fixed in Safefix II for 1 d at 4°C and then dehydrated in a graded ethanol series (30%, 50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, 90%, 95%, and 100%) for 2 h each. After dehydration, the seeds were infiltrated in xylene:paraffin solution (1:1 ratio) at 65°C for 1 h, followed by three baths of 100% paraffin, and maintained at 65°C for 5 to 7 d. The infiltrated seeds were then embedded individually in blocks filled with paraffin. Paraffin blocks were transversely sectioned (20 μm thickness) using a rotary microtome (American Optical). The sections were collected onto glass slides and dried on a hot plate maintained at 55°C overnight. The dried sections were dehydrated in a graded ethanol series (100%, 90%, 70%, 40%, and 30%) for 3 min each, followed by rinsing in distilled water and staining with 0.05% (w/v) toluidine blue solution for 3 min, rehydrated, and then mounted in a mounting medium, Histomount. The mounted sections were viewed with a Nikon EFD-3 microscope. Unless otherwise specified, all the sections were viewed under 2× magnification. Sections were viewed using SPOT Advanced software (Diagnostic Instruments) and processed using Adobe Photoshop (version. 7.0). Starch accumulation in endosperm was monitored using polarized light.

Laser Microdissection

Essentially, wheat seeds were prepared as described earlier (Kerk et al., 2003). Harvested seeds were immediately fixed in ethanol:acetic acid (3:1) solution under vacuum for 15 min (or until they sank). The seeds were kept in the fixation solution for 16 h before dehydration in a graded ethanol series (75%, 85%, and 100%) for 3 h each, and the last step was repeated twice. The seeds were then infiltrated in graded ethanol solutions containing 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100% Histoclear II (National Diagnostics) for 3 h each step, and the last stage was repeated twice. Seeds were placed in molten paraffin at 58°C under vacuum for 3 h, repeated nine times before embedding in Paraplast-X-Tra (Fisher Scientific). Embedded seeds (paraffin blocks) were kept at 4°C under dehydrating conditions until use for sectioning.

The paraffin blocks were sectioned at 20 μm thickness using an American Optical Spencer 820 microtome. Sections were floated in a 37°C water bath onto polyethylene naphthalate membrane slides (Leica Microsystems). The slides were deparaffinized using Histoclear II (Tang et al., 2006) and immediately stained with toluidine blue, and the tissues were dissected using a Leica LMD 6000 laser microdissection microscope (Leica Microsystems). The tissues were used for total RNA extraction.

One-Step RT-PCR and Real-Time Quantitative RT-PCR

One-step RT-PCR (Qiagen) was carried out according to the manufacturer’s recommendations using total RNA extracted from developing wheat seeds (100 mg). The RNAs were extracted using the RNeasy RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations and treated with the RNase-free DNase Set (Qiagen) before use. The extracted RNA was checked for quality and quantity on RNA Pico Chips using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). The resulting PCR products were sequenced to confirm the identity of the genes. The Stratagene Mx3000P QPCR with Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix Kit (ABI) was used to carry out quantitative RT-PCR experiments according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The cycle threshold values were calculated using the MxPro program (Stratagene). The primer sequences used are listed in Supplemental Table S1.

Sequence data from this article were deposited in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries with the following accession numbers: TaGT47-12 (HM236486), TaGT47-13 (HM236485), TaGT43-4 (HM236487), TaGT75-1 (HM236488), TaGT75-4 (HM236489).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Proteomics analysis strategy.

Supplemental Figure S2. Solubilization of GAX synthase activity from Golgi-enriched membranes.

Supplemental Figure S3. Analysis of wheat xyloglucan xylosyltransferase protein homolog to Arabidopsis XXT1.

Supplemental Table S1. Primer sequences used in quantitative RT-PCR analysis.

Supplemental Materials and Methods S1. Proteomics protocols.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kanwarpal Dhugga (Pioneer Hi-Bred) for providing anti-PsRGP antibodies and Dr. Wolf-Dieter Reiter (University of Connecticut) for providing the Arabidopsis UGE3 expressed in bacteria. Thanks to Dr. Henk Schols (Wageningen University) for generously providing purified endoxylanase III and AXO standards and to Dr. Sarah Wyatt (Ohio University) for her valuable comments and editing of the manuscript.

References

- Aspeborg H, Schrader J, Coutinho PM, Stam M, Kallas A, Djerbi S, Nilsson P, Denman S, Amini B, Sterky F, Master E, et al. (2005) Carbohydrate-active enzyme involved in the secondary cell wall biogenesis in hybrid aspen. Plant Physiol 137: 983–997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey RW, Hassid WZ. (1966) Xylan synthesis from uridine-diphosphate-D-xylose by particulate preparations from immature corn-cobs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 56: 574–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DM, Goubet F, Wong VW, Goodacre R, Stephens E, Dupree P, Turner S. (2007) Comparison of five xylan synthesis mutants reveals new insight into the mechanisms of xylan biosynthesis. Plant J 52: 1154–1168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DM, Zeef LAH, Ellis J, Goodacre R, Turner SR. (2005) Identification of novel genes in Arabidopsis involved in secondary cell wall formation using expression profiling and reverse genetics. Plant Cell 17: 2281–2295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burget EG, Verma R, Molhoj M, Reiter WD. (2003) The biosynthesis of l-arabinose in plants: molecular cloning and characterization of a Golgi-localized UDP-d-xylose 4-epimerase encoded by the MUR4 gene of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 15: 523–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton RA, Wilson SM, Hrmova M, Harvey AJ, Shirley NJ, Medhurst A, Stone BA, Newbigin EJ, Bacic A, Fincher GB. (2006) Cellulose synthase-like CslF genes mediate the synthesis of cell wall (1,3;1,4)-beta-d-glucans. Science 311: 1940–1942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpita NC, Gibeaut DM. (1993) Structural models of primary cell walls in flowering plants: consistency of molecular structure with the physical properties of the walls during growth. Plant J 3: 1–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpita NC, Whittern D. (1986) A highly substituted glucuronoarabinoxylan from developing maize coleoptiles. Carbohydr Res 146: 129–140 [Google Scholar]

- Cavalier DM, Keegstra K. (2006) Two xyloglucan xylosyltransferases catalyze the addition of multiple xylosyl residues to cellohexaose. J Biol Chem 281: 34197–34207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocuron JC, Lerouxel O, Drakakaki G, Alonso AP, Liepman AH, Keegstra K, Raikhel N, Wilkerson CG. (2007) A gene from the cellulose synthase-like C family encodes a β-1,4 glucan synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 140: 8550–8555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalessandro G, Northcote DH. (1981) Increase of xylan synthase activity during xylem differentiation of the vascular cambium of sycamore and poplar trees. Planta 151: 61–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desprez T, Juraniec M, Crowell EF, Jouy H, Pochylova Z, Parcy F, Höfte H, Gonneau M, Vernhette S. (2007) Organization of cellulose synthase complexes involved in primary cell wall synthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 15572–15577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhugga KS, Barreiro R, Whitten B, Stecca K, Hazebroek J, Randhawa GS, Dolan M, Kinney AJ, Tomes D, Nichols S, et al. (2004) Guar seed beta-mannan synthase is a member of the cellulose synthase super gene family. Science 303: 363–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhugga KS, Ray PM. (1994) Purification of 1,3-β-D-glucan synthase activity from pea tissue. Eur J Biochem 220: 943–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhugga KS, Tiwari SC, Ray P. (1997) A reversibly glycosylated polypeptide (RGP1) possibly involved in plant cell wall synthesis: purification, gene cloning, and trans-Golgi localization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 7679–7684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doblin MS, Pettolino FA, Wilson SM, Campbell R, Burton RA, Fincher GB, Newbigin E, Bacic A. (2009) A barley cellulose synthase-like CSLH gene mediates (1,3;1,4)-beta-D-glucan synthesis in transgenic Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 5996–6001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drea S, Leader DJ, Arnold BC, Shaw P, Dolan L, Doonan JH. (2005) Systematic spatial analysis of gene expression during wheat caryopsis development. Plant Cell 17: 2172–2185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebringerova A, Hromadkova Z, Heinze T. (2005) Hemicellulose. Adv Polym Sci 186: 1–67 [Google Scholar]