Abstract

The juxtacapsular bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (jcBNST) is activated in response to basolateral amygdala (BLA) inputs through the stria terminalis and projects back to the anterior BLA and to the central nucleus of the amygdala. Here we show a form of long-term potentiation of the intrinsic excitability (LTP-IE) of jcBNST neurons in response to high-frequency stimulation of the stria terminalis. This LTP-IE, which was characterized by a decrease in the firing threshold and increased temporal fidelity of firing, was impaired during protracted withdrawal from self-administration of alcohol, cocaine, and heroin. Such impairment was graded and was more pronounced in rats that self-administered amounts of the drugs sufficient to maintain dependence. Dysregulation of the corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) system has been implicated in manifestation of protracted withdrawal from dependent drug use. Administration of the selective corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 1 (CRF1) antagonist R121919 [2,5-dimethyl-3-(6-dimethyl-4-methylpyridin-3-yl)-7-dipropylamino-pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine)], but not of the CRF2 antagonist astressin2-B, normalized jcBNST LTP-IE in animals with a history of alcohol dependence; repeated, but not acute, administration of CRF itself produced a decreased jcBNST LTP-IE. Thus, changes in the intrinsic properties of jcBNST neurons mediated by chronic activation of the CRF system may contribute to the persistent emotional dysregulation associated with protracted withdrawal.

Introduction

The bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) has been implicated in the reinforcing effects of alcohol and drugs of abuse (Epping-Jordan et al., 1998; Carboni et al., 2000; Delfs et al., 2000; Eiler et al., 2003; Macey et al., 2003; Dumont et al., 2005) and supports brain self-stimulation in animals with a genetic alcohol preference (Eiler et al., 2007). The BNST has also been shown to be involved in stress-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior during protracted withdrawal (Erb and Stewart, 1999; Shalev et al., 2001; McFarland et al., 2004). Both drug withdrawal (Delfs et al., 2000; Olive et al., 2002; Erb et al., 2004) and stress (Stout et al., 2000) induce neurochemical changes in this brain region.

The juxtacapsular subdivision of the lateral BNST (jcBNST) is the only part of the BNST that receives dense glutamatergic projections from the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala (BLA) and, unlike other subregions of the lateral BNST, does not receive inputs from the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA) (Larriva-Sahd, 2004). In turn, the jcBNST projects back to the anterior BLA and to the CeA (Dong et al., 2000). The jcBNST also projects to the lateral hypothalamus, striatum, and nucleus accumbens, among other brain regions involved in the actions of drugs of abuse (Dong et al., 2000). The jcBNST, and the dorsolateral BNST in general, contain densely arrayed GABAergic neurons (Sun and Cassell, 1993; Veinante et al., 1997) and abundant corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF)-containing neurons (Sawchenko, 1987). Conversely, the jcBNST and the dorsolateral BNST in general are devoid of glutamatergic neurons (Hur and Zaborszky, 2005).

Neuronal activity can induce persistent modifications in the way a neuron reacts to subsequent inputs, both by changing synaptic efficacy and/or intrinsic excitability. The former has received greater attention in recent years, and it is generally accepted that changes in the strength of synaptic connections underlie memory storage and some of the maladaptive changes in reward processing induced by drugs of abuse (Thomas et al., 2000; Ungless et al., 2001; Melis et al., 2002; Saal et al., 2003; Malenka and Bear, 2004; Dumont et al., 2005). In many brain regions, neuronal activity has also been shown to induce long-term modifications of intrinsic neuronal excitability, i.e., the propensity of neurons to fire action potentials.

Long-term potentiation of the intrinsic excitability (LTP-IE) is a protracted increase in the probability of firing and/or in the efficacy of neuronal circuits (Turrigiano et al., 1994; Desai et al., 1999; Aizenman and Linden, 2000; Armano et al., 2000; Bekkers and Delaney, 2001; Ross and Soltesz, 2001; Daoudal et al., 2002; Egorov et al., 2002; Debanne et al., 2003; Mahon et al., 2003; Smith and Otis, 2003; Cudmore and Turrigiano, 2004; Chen et al., 2007). Here we tested the hypothesis that a history of drug self-administration may induce long-lasting changes in the excitability of jcBNST neurons in animal models of alcohol, cocaine, and heroin self-administration. We observed a reduced capacity for synchronously increasing jcBNST neuronal activity during protracted withdrawal that could result in inefficient feedback inhibition to the CeA and increased emotional arousal. These effects were blocked by repeated administration of a CRF receptor 1 (CRF1), but not CRF2, receptor antagonists and could be mimicked by repeated, but not acute, administration of CRF.

Materials and Methods

Electrophysiological techniques.

Acute brain slices were performed as described previously (Sanna et al., 2000, 2002b) with minor modifications. Briefly, coronal rat brain slices (350 μm) were collected from the rostral cerebrum of Wistar rats with a Leica VT1000E vibrating microtome, at the level shown in Figure 1A, in oxygenated artificial CSF (aCSF) [in mm: 130 NaCl, 3.5 KCl, 24 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2.2 CaCl2, 10 d-glucose, and 2 MgSO4, pH 7.4]. Slices were preincubated in aCSF for 1 h at 32°C and then maintained at room temperature for at least 30 min before being transferred to a submerged recording chamber at 31°C. Extracellular field potentials were recorded with microelectrodes filled with aCSF (3–5 MΩ) using an Axoclamp 2B head-stage amplifier (Molecular Devices). Bipolar stimulating electrodes were placed in the stria terminalis (Fig. 1B). Constant-current pulses of 0.08 ms duration were used for stimulation. The amplitude of the second negative component of the field potential (Fig. 1C) was measured at its trough. Acquisition and analyses were performed with the LABVIEW software package (National Instruments). For field potential recordings, input–output (I/O) curves were performed in each slice, and test stimulation intensity was adjusted to obtain field potentials approximately one-third of the maximum amplitude. The high-frequency stimulation (HFS) paradigm consisted of five trains at 100 Hz for 1 s at 10 s intervals at the test stimulation intensity. For occlusion experiments, after bath application of GABAA and GABAB inhibitors or 4-aminopyridine (4-AP), I/O curves were again determined, and stimulation intensity was adjusted as described to obtain one-third of maximum field potential amplitude before delivering the HFS. Intracellular recordings were made using sharp glass micropipettes filled with 2 m potassium acetate, pH 7.3 (180–200 MΩ), with an Axoclamp 2B head-stage amplifier in current-clamp mode. The threshold of the first action potential, evoked in response to single intracellular depolarizing pulses (500 ms at 15 s intervals) was measured at the sharp transition from prepotential to upstroke (Armano et al., 2000), as shown in Figure 2E. Input resistance (Rin) was measured with sharp electrodes in current-clamp mode at the end of 350 ms hyperpolarizing current pulses of −0.2 nA. This current value is in the linear part of the I–V curve. The slope of the depolarizing prepotential was measured over the 10 ms immediately preceding the action potential upstroke and expressed in millivolts per millisecond. After 20 min of a stable baseline of threshold recording, HFS was delivered to the stria terminalis. For whole-cell recordings, slices of brain tissue containing the BNST were placed in a superfusion chamber mounted on a Olympus microscope stage and were viewed using infrared differential interference contrast optics and video microscopy. Whole-cell recordings were made using patch pipette with resistances of 3–6 MΩ filled with a solution containing the following (in mm): 120 KMeSO4, 10 KCl, 3 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 phosphocreatine, 2 MgATP, and 0.2 GTP, pH 7.2 (osmolarity, 280–290 mOsm). Whole-cell access resistances were estimated from the peak current produced during voltage-clamp steps and were found to be 15–40 MΩ. Access and input resistances were monitored throughout the recordings to ensure stability. To isolate the α-dendrotoxin (α-DTX)-sensitive D-type K+ current (ID), the extracellular solution contained 0.5 μm TTX, 10 μm 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX), 100 μm CdCl2, and 10 mm tetraethylammonium to block interfering K+ and inward currents. For analysis, only the current trace for the +40 mV step was used, and the average current amplitude between 50 and 100 ms after application of the voltage step was measured. For morphological analysis, 1–2 mg/ml biocytin (Sigma) was added to the intracellular solution. Immediately after recording, slices were fixed in 0.1 m PBS, pH 7.4, containing 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.1% picric acid for 24 h. Slices were then processed for biotinylated horseradish peroxidase conjugated to avidin (ABC-elite, Vectastain; Vector Laboratories).

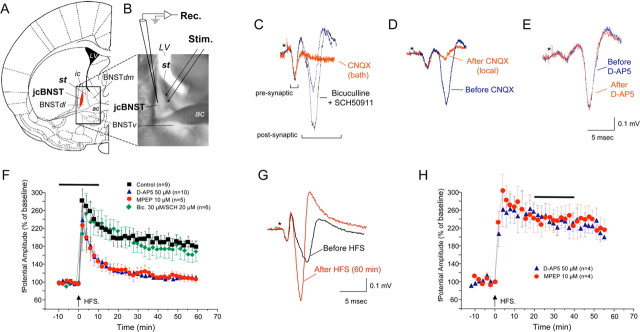

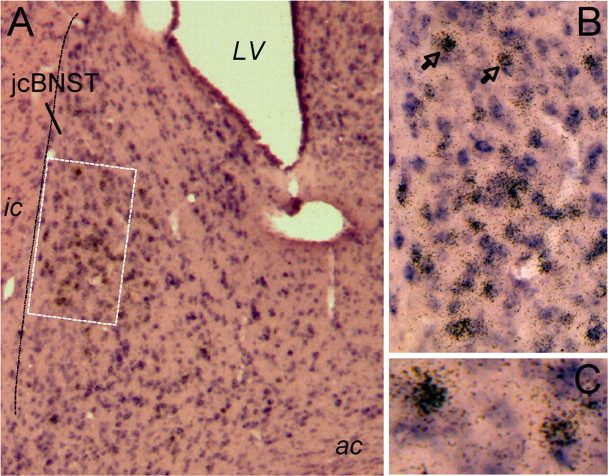

Figure 1.

Field potential in the jcBNST. A, Coronal brain slices were obtained from the rostral cerebrum of Wistar rats at the level indicated in the diagram (modified from Paxinos and Watson, 1998). st, Stria terminalis; jcBNST, juxtacapsular bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (shown in red); BNSTdl, dorsolateral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis; BNSTdm, dorsomedial bed nucleus of the stria terminalis; BNSTv, ventral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis; ac, anterior commissure; LV, lateral ventricle; ic, internal capsule. The boundary of the jcBNST is in good agreement with Dong et al. (2000) and was operationally defined by the area in which a glutamatergic field potential was readily evoked by stimulation of the stria terminalis. B, Photomicrograph of a brain slice at the level of the BNST demonstrating electrode placements for stimulation (Stim.) and electrophysiological recordings (Rec.). C, Field potential evoked in the jcBNST by stimulation of the stria terminalis in coronal brain slices is characterized by two fast negative components followed by a more variable slow positive deflection (blue trace). The second negative component of the field potential and the positive deflection were abolished by application of the AMPA glutamate receptor inhibitor CNQX in bath (20 μm) (red trace). Blocking GABAA and GABAB receptors with bicuculline (30 μm) and SCH50911 (20 μm), respectively, increased the size of the postsynaptic components of the field potential without altering the field morphology (black trace). D, Local application of CNQX by diffusion of the inhibitor included in the recording electrode (25 mm) blocked the second negative and the positive components of the field potential (red trace), suggesting they are postsynaptic responses that originate locally in the jcBNST. E, Bath application of the NMDA inhibitor d-AP-5 (50 μm) had no effect on the field potential (red trace). Stimuli artifacts were removed, and the asterisk indicates their location. F, Delivery of HFS (5 trains at 100 Hz for 1 s at 10 s intervals) resulted in a protracted potentiation of the amplitude of the postsynaptic component of the field potential (sample traces are shown in G). A transient application of either d-AP-5 or the mGluR5 inhibitor MPEP around the time of delivery of HFS (horizontal bar) prevented potentiation of the amplitude of the field potential. However, tetanization during continuous application of the GABAA and GABAB inhibitors bicuculline and SCH50911, respectively, resulted in the same degree of potentiation as controls (baseline renormalized). H, Application of either d-AP-5 or the mGluR5 inhibitor MPEP to an established LTP of field potential (horizontal bar) was ineffective.

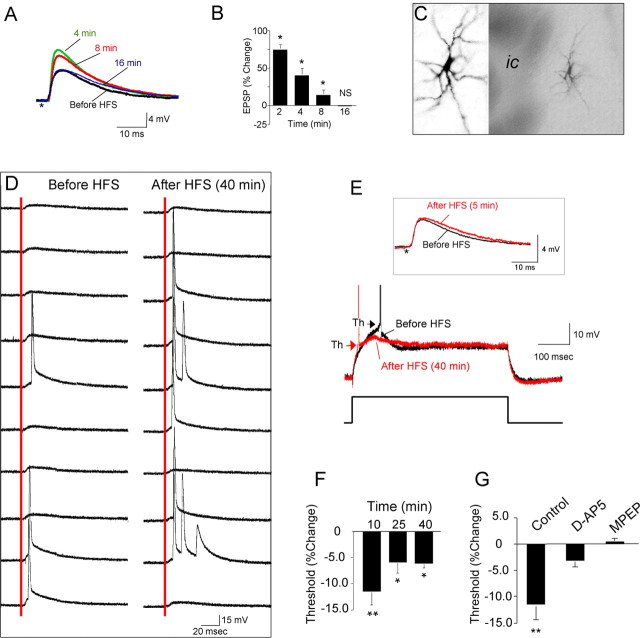

Figure 2.

LTP-IE in the jcBNST. A, HFS of the stria terminalis induced only a transient EPSP potentiation that reverted to basal levels within 16 min. Stimuli artifacts were removed, and the asterisk indicates their location. B, Quantification of EPSP amplitude changes in cells of the jcBNST at the indicated times after HFS of the stria terminalis (*p < 0.05 from baseline; NS, t(25) = 0.123). C, jcBNST neurons visualized by intracellular injection of biocytin after recording demonstrate a multipolar morphology (ic, internal capsula). D, HFS caused increased probability of firing in response to single stimuli (red line) applied to the stria terminalis. Traces shown are 10 sweeps representing evoked responses before and 40 min after HFS. E, Threshold (arrowheads) for action potential generation in response to a depolarizing current pulse (500 ms, 0.07 nA) was shifted to more hyperpolarized membrane potentials for a protracted time after HFS (red trace). Inset, Such a shift also could be observed even in the absence of potentiation of EPSP after HFS (red trace), as in the representative neuron shown (same neuron as in D). F, The shift of the threshold for action potential generation after HFS was significant for over 40 min after HFS (**p < 0.01 from baseline, n = 14, at 10 min, t = 4.26; *p < 0.05 from baseline at 25 min, t = 2.72, and at 40 min, t = 6.66). G, HFS-induced shift of the action potential threshold was prevented by a transient application for 20 min around the time of delivery of HFS (as in Fig. 1F) of either the NMDA inhibitor d-AP-5 (50 μm) or the mGluR inhibitor MPEP (10 μm) in the perfusion bath (t = −8.491,*p < 0.05 from control, n = 15; for d-AP-5, t = −1.376, n = 8, NS; and for MPEP, t = 1.044, n = 6, NS).

Alcohol self-administration.

Rats were trained to orally self-administer ethanol using a modification of the saccharin-fading procedure, as described previously (Roberts et al., 2000). After successful acquisition of operant responding, the animals were introduced to a free-choice task in which presses on one lever produced 0.1 ml of alcohol solution, whereas responses at the other lever resulted in delivery of an equal volume of water. Alcohol was alternated daily between the two levers. The criterion for stable baseline intake was ±20% across three consecutive 30 min sessions with a mean intake of >20 responses. Alcohol vapor chambers were used to induce dependence by intermittent exposure (14 h on/10 h off) to an air/ethanol mixture for a total of 4 weeks, which reliably produce alcohol dependence in rats (Gilpin et al., 2008). Intermittent alcohol exposure mimics human patterns of alcohol consumption (Slawecki et al., 1999; Sanna et al., 2002a; Repunte-Canonigo et al., 2007) and induces more rapid increases in self-administration than continuous exposure (O'Dell et al., 2004). Blood alcohol levels were measured with an oxygen-rate alcohol analyzer (Analox Instruments) and maintained at (mean ± SEM) 155 ± 15 mg%.

Intravenous self-administration.

Rats were prepared with chronic intravenous catheters as described previously (Ahmed et al., 2005; S. A. Chen et al., 2006). For cocaine self-administration, rats were allowed to self-administer cocaine on a fixed-ratio 1 (FR1) schedule (250 μg per injection in a volume of 0.1 ml delivered over 4 s). Each response on the lever resulted in a cocaine injection and was followed by a 20 s timeout period. Rats were allowed to self-administer cocaine either for 1 h short access (ShA) or 6 h long access (LgA) per day. For heroin self-administration, rats were allowed either 1 h (ShA) or 23 h (LgA) access on an FR1 schedule (60 μg/kg per 0.1 ml infusion, 20 s timeout) (S. A. Chen et al., 2006).

Analysis of gene expression.

Target RNA was generated with the BioArray High Yield RNA Transcript Labeling kit (Enzo). Quality of total RNA was assessed using the NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer for quantification of small samples and the Agilent Bioanalyzer. The jcBNST was dissected with minimal surrounding tissue from transilluminated vibratome-cut coronal rat brain slices (350 μm) kept cold but not frozen, as described by Cuello and Carson (1983). All BNST samples used for microarray and quantitative PCR (qPCR) were from animals in which the contralateral BNST was used for electrophysiological experiments. Similarly dissected jcBNST were used for Western blotting.

High density microarrays (Affymetrix RAE230A) were hybridized to target cRNA derived from double in vitro transcription as described previously (Sanna et al., 2005) with minor modifications and scanned according to the protocol of the manufacturer. Specifically, pools of three samples from alcohol-dependent animals and three matched control and three from cocaine LgA and three matched control were tested using RAE 230 Affymetrix arrays. Samples from each experimental group were pooled and run in duplicate. Signal intensities were scaled to a target intensity of 250 using the MAS 5.0 algorithm. Differentially expressed genes were obtained by the Affymetrix comparison analysis algorithm and t test analysis of GeneSpring 7.2-normalized expression values as described previously (Repunte-Canonigo et al., 2007).

Differentially expressed genes were validated by qPCR from individual animals with a history of dependence on the three drugs under study (alcohol, cocaine, and heroin) and matched controls. To this aim, we tested individual samples from a separate set of animals as previously done (Ahmed et al., 2005; Repunte-Canonigo et al., 2007). Primers were designed using the Beacon Designer Software (Premier Biosoft International). The iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) was used in 25 μl reaction volume with an iQ5 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad) using 0.2 ml 96-well thin-wall PCR plates (Bio-Rad). Reaction steps were 95°C for 3 min, 40× (95°C for 10 s, 60°C for 20 s, 72°C for 20 s). For quantification, the relative standard curve method (Livak, 1997) was used as described previously (Ahmed et al., 2005; Repunte-Canonigo et al., 2007). β-Actin was used as a reference mRNA for normalization. Standard curves for both the target and reference genes were generated for each qPCR run with 1-log serial dilutions (1 to 10−5) of first-strand cDNAs from a pooled control sample by plotting cycle threshold (Ct) versus the log of input amount. qPCR standard curves had slopes in the range of −3.5 to −3.0. Linear correlation coefficients (R2) ranged from 0.98 to 0.99. Sample Ct values were interpolated using the following formula: (Ct − b)/m, where b is the y-intercept of the standard curve line, and m is the slope of the standard curve line.

Western blotting was performed from individual animals as described previously (Sanna et al., 2000, 2002b) using a rabbit polyclonal specific for amino acids 417–499 of rat Kv1.2 (APC-010; Alomone Labs) at a dilution of 1:200; for control, β-actin was detected with a mouse monoclonal antibody (A1978; Sigma) at a dilution of 1:2000. Quantification of Western blot signal was done with the NIH Image software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image/).

Double in situ hybridization. Rats were perfused transcardially with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (PB), pH 7.3. Brains were postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 h at 4°C, rinsed with PB, and transferred sequentially to 12, 14, and 18% sucrose solutions in PB. In situ hybridization was performed as described previously (Morales et al., 2008). Cryosections were incubated for 10 min in PB containing 0.5% Triton X-100, rinsed two times for 5 min with PB, treated with 0.2 N HCl for 10 min, rinsed two times for 5 min with PB and then acetylated in 0.25% acetic anhydride in 0.1 m triethanolamine, pH 8.0, for 10 min. Sections were rinsed two times for 5 min with PB, postfixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, and, after a final rinse with PB, hybridized for 16 h at 55°C in hybridization buffer (50% formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, 5× Denhardt's solution, 0.62 m NaCl, 50 mm DTT, 10 mm EDTA, 20 mm PIPES, pH 6.8, 0.2% SDS, 250 μg/ml salmon sperm DNA, and 250 μg/ml tRNA) containing [35S] single-stranded antisense rat CRF riboprobes at 107 cpm/ml, together with the 600 ng mix of GAD65 and GAD67 digoxigenin-labeled antisense riboprobes. The antisense digoxigenin GAD65 and GAD67 were obtained by in vitro transcription using digoxigenin-11-UTP labeling mix (Roche) and T3 RNA polymerase. Sections were treated with 4 μg/ml RNase A at 37°C for 1 h, washed with 1× SSC, 50% formamide at 55°C for 1 h, and with 0.1× SSC at 68°C for 1 h. After the last SSC wash, sections were rinsed with TBS buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, 0.5 m NaCl, pH 8.2). Afterward, sections were incubated with an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antibody against digoxigenin (Roche Applied Science) overnight at 4°C; the alkaline phosphatase reaction was developed with nitroblue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (Roche Applied Science) yielding a purple reaction product. Sections were mounted on slides, air dried, and dipped in Ilford K.5 nuclear tract emulsion (Polysciences) (1:1 dilution in double distilled water) and exposed in the dark at 4°C for 4 weeks before development.

In vivo drug treatments.

The CRF1 antagonist R121919 [2,5-dimethyl-3-(6-dimethyl-4-methylpyridin-3-yl)-7-dipropylamino-pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine)] (Chen et al., 1996) (formerly referred to as NBI 30775) was administered subcutaneously at a dose of 20 mg/kg, three times in 20% hydroxypropyl β-cyclodextrin, pH 4.5, 12 h apart because of the extensive data available for this route of administration regarding doses sufficient to occupy brain CRF1 receptors (Gutman et al., 2003) and to produce behavioral effects in models of ethanol or drug dependence (Sabino et al., 2006; Funk et al., 2007; Skelton et al., 2007a,b). The CRF2 antagonist (Rivier et al., 2002) was administered by intracerebroventricular injections (4 μg in 2 μl), as done previously (Cottone et al., 2007; Fekete et al., 2007), because as a peptide does not cross the blood–brain barrier. CRF was administered intracerebroventricularly at a dose of 1 μg as previously done (Izzo et al., 2005).

Data analysis.

Student's t test (paired or unpaired as appropriate) or one-way or two-way ANOVA were used to analyze the behavioral and electrophysiological data using StatView (SAS Institute) or Microsoft Excel. ANOVA was followed by Fisher's LSD post hoc analysis. All results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Cutoff p values of <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant, and results are reported as either <0.05 or <0.01.

Results

LTP-IE in the jcBNST

In jcBNST brain slices from control rats, stimulation of the region of the stria terminalis (Fig. 1A,B) that conveys glutamatergic inputs from the BLA (Dong et al., 2000) evoked a field potential characterized by two fast negative components followed by a more variable slow positive deflection (Sawada et al., 1980), as shown in Figure 1C. The second negative and slow positive components of the field potential were abolished by application of the AMPA receptor inhibitor CNQX either in the bath (20 μm) (Fig. 1C) or locally by diffusion of the inhibitor (25 mm) included in the recording electrode (Fig. 1D). Bath application of the glutamatergic NMDA inhibitor d-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (d-AP-5) (50 μm) had no effect on the field potential (Fig. 1E). Blocking GABAA and GABAB receptors with bicuculline (30 μm) and SCH50911 [(2S)(+)5,5-dimethyl-2-morpholineacetic acid] (20 μm), respectively, considerably increased the size of the second negative components of the field potential without abolishing the positive component or altering the field morphology (Fig. 1C). Together, these observations indicate that the second negative and positive components of the field potential are postsynaptic responses mediated by AMPA receptors and originate locally in the jcBNST, whereas the first negative component of the field potential represents the presynaptic volley, i.e., the spike activity of the afferent fibers.

Delivery to the stria terminalis of an HFS paradigm consisting of five trains at 100 Hz for 1 s at 10 s intervals resulted in protracted potentiation of the amplitude of the negative postsynaptic component of the field potential (184 ± 1.6% at 60 min after HFS; n = 9) (Fig. 1F,G). A transient bath application of either d-AP-5 (50 μm) or the mGluR5 inhibitor 2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)-pyridine (MPEP) (10 μm) for 20 min around the time of delivery of HFS prevented potentiation of the field potential amplitude (110.9 ± 0.6%, n = 10 and 110.3 ± 1%, n = 5, 60 min after HFS for d-AP-5 and MPEP, respectively; not significantly different from baseline before delivery of HFS for d-AP-5, t test, t = 0.218, p = 0.416; and MPEP, paired t test, t = −1.265, p = 0.863) (Fig. 1F). However, HFS during continuous application of the GABAA and GABAB inhibitors bicuculline (30 μm) and SCH50911 (20 μm), respectively, resulted in the same degree of potentiation as controls (167.1 ± 2.7%, n = 6, 60 min after HFS) (Fig. 1F). Bath application of either d-AP-5 or the mGluR5 inhibitor MPEP 20 min after HFS was ineffective (Fig. 1H). Thus, tetanization of the stria terminalis resulted in a potentiation of the field potential in the jcBNST that was dependent on NMDA and mGluR5.

To determine the cellular and molecular mechanisms responsible for the potentiation of field potential in the jcBNST, we performed intracellular recordings from jcBNST neurons in current-clamp mode with sharp microelectrodes. Delivery of the HFS paradigm only transiently potentiated EPSP amplitude in jcBNST neurons, which declined to baseline levels within 16 min (Fig. 2A,B). Thus, the duration of potentiation of field potential amplitude in the jcBNST (Fig. 1F) was much more protracted than the transient EPSP potentiation seen by intracellular recordings (Fig. 2A,B). A potentiation of the field potential without a concomitant potentiation of EPSPs might result from an LTP-IE of jcBNST neurons, leading to more cells firing. On anatomical grounds, the multipolar neuronal morphology of jcBNST neurons (Fig. 2C) does not favor the summation of EPSPs into discernable field EPSPs. Together, these observations suggested the hypothesis that the postsynaptic component of evoked field potentials in the jcBNST was a primary manifestation of the summation of synaptically driven action potentials of jcBNST neurons, i.e., the population spike, as in other neuronal populations characterized by radial dendrites (Misgeld et al., 1979; Zhou and Poon, 2000; Walcott and Langdon, 2002).

Supporting this hypothesis, delivery of HFS induced a protracted increase in firing probability (Fig. 2D) without concomitant increases of the EPSP slope (Fig. 2E). Because activity-dependent LTP-IE of neurons leading to increased firing may be caused by decreased action potential thresholds (Aizenman and Linden, 2000; Armano et al., 2000; Cudmore and Turrigiano, 2004; Xu et al., 2005), we measured the threshold of the first action potential by intracellular recordings in jcBNST neurons before and after HFS. HFS induced a long-lasting shift toward hyperpolarization (4.9 ± 0.7 mV, n = 15) of the threshold for action potential generation in response to single intracellular depolarizing pulses selected to evoke one or two action potentials (500 ms at 15 s intervals) (Fig. 2E). Data showed that the action potential threshold measured at different times after HFS delivery was significantly lower than before HFS (at 10 min, t = 4.26, p < 0.01; at 25 min, t = 2.72, p < 0.01; at 40 min, t = 6.66, p < 0.01; n = 14; one-sample t test) (Fig. 2F). Input resistance measured by injection of a hyperpolarizing and depolarizing current pulses showed no significant changes after delivery of HFS (115.1 ± 8.5 MΩ before and 112.1 ± 10.2 MΩ 60 min after delivery of HFS, t = 0.52, NS, n = 11). Three different types of jcBNST neurons were recognized based on their rectification properties and rebound depolarization in response to hyperpolarizing current injections, as shown previously in both rat (Hammack et al., 2007) and mouse (Egli and Winder, 2003). A significant shift toward hyperpolarization of the threshold for action potential generation was induced by HFS in all the three types of neurons according to the classification of Hammack et al. (2007): type I, 5.63 ± 1.4 mV (t = −4.04, p < 0.01, n = 6); type II, 5.22 ± 1.0 mV (t = −5.49, p < 0.01, n = 6), and type III, 3.52 ± 1.0 mV (t = −3.44, p < 0.05, n = 4). A transient application of either the NMDA inhibitor d-AP-5 (50 μm) or the mGluR5 inhibitor MPEP (10 μm) applied for 20 min around the time of delivery of HFS as in Figure 1F blocked the HFS-induced shift of the action potential threshold (Fig. 2G), consistent with the requirement for these glutamatergic receptors for the potentiation of jcBNST field potential (Fig. 1F).

Protracted withdrawal from self-administration of alcohol, cocaine, and heroin impairs LTP-IE of jcBNST

To test the hypothesis that LTP-IE in the jcBNST would be altered in rats with a history of alcohol exposure sufficient to produce escalated self-administration, we first measured the amplitude of the field potentials, and we then performed intracellular measures of the threshold for action potential generation.

We used a validated animal model of escalated dependent alcohol intake induced by exposure to alcohol vapors (Roberts et al., 2000; O'Dell et al., 2004). Rats were trained to orally self-administer alcohol in a concurrent, two-lever, free-choice contingency using a modification of the sweet solution fading procedure. After acquisition of operant responding for ethanol, half of the rats were exposed to intermittent ethanol vapors for 4 weeks to induce dependence (dependent group), whereas the remaining rats were exposed to air in the same apparatus for the purpose of control (nondependent group). During protracted withdrawal (3–5 weeks after withdrawal), rats were again tested for operant responding for ethanol and used for electrophysiology experiments ∼1–2 weeks after testing. The average number of presses for ethanol in the post-dependent group during protracted withdrawal was significantly increased compared with the nondependent group (83.25 ± 6.3 vs 24.5 ± 7.4, p < 0.01) (Fig. 3A). As shown in Figure 3B, in dependent rats at 4–6 weeks after withdrawal, potentiation of the field potential, which as shown above reflects LTP-IE in the jcBNST, was significantly impaired at 60 min after HFS (104.9 ± 1.7%, n = 10, p < 0.05 from controls). Conversely, at 4–6 weeks after withdrawal, in nondependent control rats (161 ± 0.7%, n = 7), field potentials were not significantly different from controls at 60 min after HFS (183.6 ± 1.5%, n = 22). However, in dependent rats tested during acute withdrawal (3–6 h), potentiation of the field potential at 60 min after HFS (208.5 ± 1.9%, n = 7) was not significantly different from controls, whereas at 1–2 weeks after withdrawal, a significant impairment was observed in both dependent (127.4 ± 1.9%, n = 8, p < 0.05 from controls and dependents during acute withdrawal) and nondependent (129.7 ± 0.9%, n = 8) rats. Thus, alcohol dependence induces a protracted impairment of the capacity for plasticity in the jcBNST, whereas a transient impairment is seen after a history of nondependent alcohol intake.

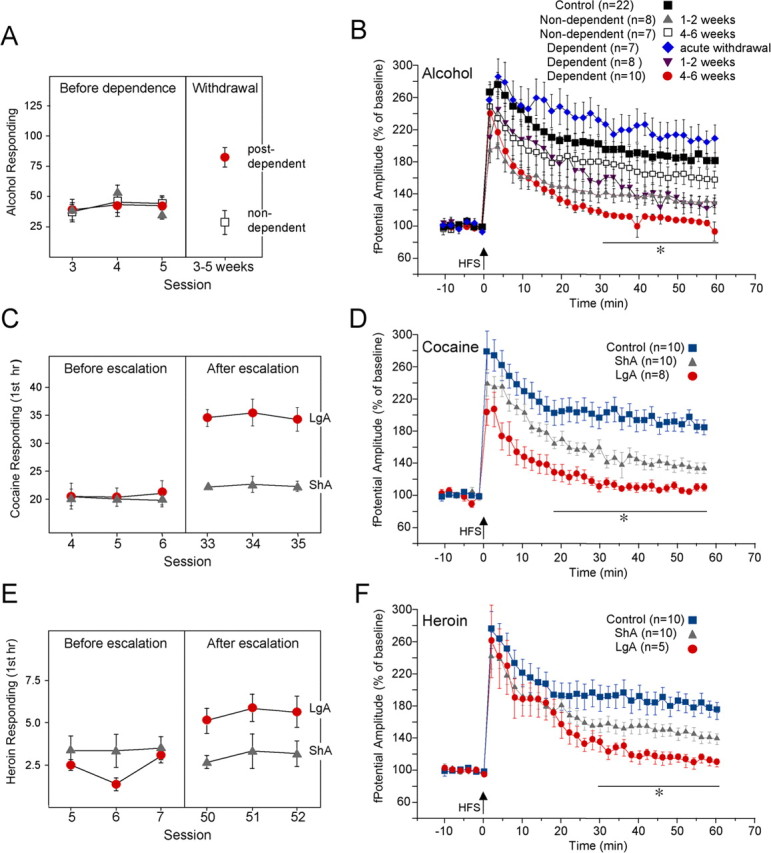

Figure 3.

Disruption of LTP-IE in the jcBNST during protracted withdrawal from self-administration of alcohol, cocaine, and heroin. A, Operant responding for ethanol over the last three self-administration sessions before induction of dependence (left panel) and 3–5 weeks after withdrawal (right panel). The average number of presses for ethanol in the post-dependent group during protracted abstinence (right panel) was significantly increased over the nondependent group (p < 0.01). B, In dependent rats, potentiation of the amplitude of the field potential in the jcBNST, which is a manifestation of LTP-IE, as shown in Figure 2, progressively declined over time and was completely abolished at 4–6 weeks after withdrawal 60 min after HSF. In dependent rats tested during acute withdrawal (3–6 h), the potentiation of the field potential was not impaired. In nondependent rats, potentiation of the field potential was impaired at 1–2 weeks after alcohol self-administration but was readily observed at 4–6 weeks after cessation of alcohol self-administration. Two-way ANOVA results partitioned for condition (F(5,1680,0.05) = 195.33, p < 0.001) and for time (F(29,1680,0.05) = 19.0, p < 0.001), with no significant interaction between these factors. *Dependent at 4–6 weeks different from control, dependent during acute withdrawal, and non-dependent at both 1–2 and 4–6 weeks (p < 0.01); dependent at 1–2 weeks different from control and dependent during acute withdrawal (p < 0.05); non-dependent at 1–2 weeks different from control and non-dependent at 4–6 weeks (p < 0.05). C, Rats were trained to self-administer cocaine on a fixed-ratio 1 schedule and allowed access to cocaine self-administration for either 1 h (ShA) or 6 h (LgA) per day; the latter induces an escalating pattern of cocaine intake. In the first hour of cocaine self-administration during the last three self-administration sessions (right panel), LgA rats averaged 35.0 ± 0.8 cocaine infusions versus 22.4 ± 0.3 in ShA rats (p < 0.01). D, Potentiation of field potential in the jcBNST of brain slices from LgA rats was impaired 1–2 weeks after cessation of cocaine self-administration. ShA rats showed a level of potentiation that was between that of control and LgA rats. Two-way ANOVA results partitioned for access to self administration (F(2,750,0.05) = 269.0, p < 0.001) and for time (F(29,750,0.05) = 13.5, p < 0.001), with no significant interaction between these factors. *LgA different from control and ShA (p < 0.01); ShA different from control (p < 0.01). E, Rats were similarly trained to self-administer heroin on a fixed-ratio 1 schedule and allowed access for either 1 h (ShA) or 23 h (LgA) per day. In the first hour of heroin self-administration during the last three self-administration sessions (right panel), LgA rats averaged 5.54 ± 0.2 infusions versus 3.05 ± 0.2 for ShA rats (p < 0.01). F, Also in LgA heroin self-administering rats, potentiation of the field potential in the jcBNST was impaired 1–2 weeks after withdrawal. ShA rats showed a partial level of impairment at the same time after cessation of self-administration. Two-way ANOVA results partitioned for access to self administration (F(2,690,0.05) = 114.42, p < 0.001) and for time (F(29,690,0.05) = 14.15, p < 0.001), with no significant interaction between these factors. *LgA different from control (p < 0.01) and ShA (p < 0.05); ShA different from control (p < 0.01).

To explore the generality of these findings, we investigated the induction of LTP-IE in rats with or without extended access to cocaine or heroin self-administration sufficient to produce dependence (Koob et al., 2004; Ahmed et al., 2005; R. Chen et al., 2006). Rats self-administering cocaine for 1 h per day (ShA) showed stable cocaine intake over time (Fig. 3C). Conversely, extended access to cocaine self-administration for 6 h per day (LgA) induced an increase in drug intake, previously correlated with a persistent decrease in brain reward function during withdrawal (Koob et al., 2004) (Fig. 3C). Similar to alcohol post-dependent rats, a strong impairment of potentiation of the field potential amplitude was observed in the jcBNST of LgA rats 1–2 weeks after cessation of cocaine self-administration (109.4 ± 3.3%, n = 8, 60 min after HSF), whereas ShA rats showed a level of potentiation (132.7 ± 5.6%, n = 10) that was intermediate between that of control and LgA rats (Fig. 3D). LTP-IE in LgA heroin self-administering rats 1–2 weeks after cessation of cocaine self-administration was also significantly impaired (110.2 ± 5.9%, 60 min after HFS, n = 5) compared with controls (176.7 ± 9.8%, n = 10) and ShA rats (140 ± 5.2%, n = 10, p < 0.05 from both control and ShA rats) (Fig. 3E,F). Again, ShA rats showed an intermediate level of potentiation impairment (p < 0.01 from controls). Thus, multiple drugs of abuse induced a common disruption of potentiation of the field potential in the jcBNST after delivery of HFS to the stria terminalis during protracted withdrawal.

The threshold for action potential generation in jcBNST neurons is regulated by the ID current

Consistent with the disruption of potentiation of the field potential in the jcBNST of rats with histories of dependence on alcohol or LgA intravenous self-administration of cocaine or heroin during protracted withdrawal, the HFS-induced shift toward hyperpolarization of the threshold for action potential generation that is required for the potentiation of the field potential in the jcBNST was not observed (Fig. 4A). The threshold for action potential in animals with a history of alcohol, cocaine, or heroin dependence before delivery of HFS (control, −50.9 ± 1.5 mV, n = 14; alcohol post-dependent, −50.7 ± 1.9 mV, n = 7; cocaine, −47.5 ± 1.7 mV, n = 9, heroin, −54.1 ± 1.9 mV, n = 7) did not differ from controls (two-tailed t test assuming equal variance: control vs alcohol post-dependent, t = 0.11, NS; control vs cocaine, t = 1.92, NS; control vs heroin, t = −1.25, NS), indicating that the observed lack of shift toward hyperpolarization in post-dependent animals reflects impaired capacity for LTP-IE rather than occlusion by a preexisting LTP-IE.

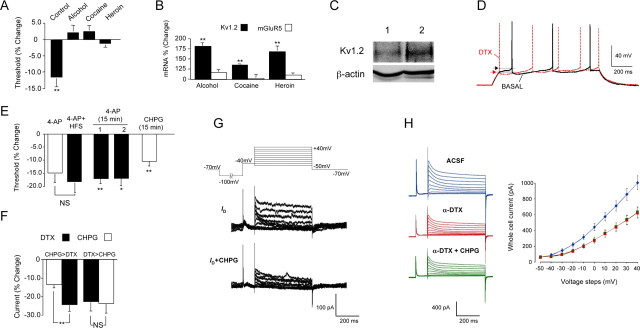

Figure 4.

The threshold for action potential generation in jcBNST neurons is regulated by the ID current. A, HFS-induced shift toward hyperpolarized threshold for action potential generation was not seen in brain slices from ethanol (n = 8), cocaine (n = 8), or heroin (n = 8) post-dependent rats, unlike in controls (n = 14) measured 10 min after HFS (t = 4.14, **p < 0.01 for baseline; alcohol, t = −0.99, NS; cocaine, t = −1.44, NS; heroin, t = 1.10, NS). B, Combined microarray and qPCR analyses demonstrated that expression of Kv1.2, a member of the Kv family of K+ channels implicated in mediating the ID current, was significantly increased in post-dependent rats, whereas the expression of mGluR5 and other genes potentially involved in ID regulation was unaltered. Bar graph represents a quantification of the qPCR validation of the microarray results. Kv1.2 (black bars): From control, t = −7.76, n = 15; for alcohol, t = −4.25, n = 5; and cocaine, t = −3.92, n = 5; n = 7 for heroin; **p < 0.01). mGluR5 (white bars): For alcohol, t = −0.621; for cocaine, t = −0.178; for heroin, t = −0.854. C, Kv1.2 was significantly increased in the jcBNST of ethanol post-dependent (2) rats versus control (1) rats by Western blotting (n = 5, one-tail t test, t = 2.07, n = 5–6, *p < 0.05). D, Pharmacological inhibition of the ID current by bath application of the ID blocker α-DTX (1 μm) shifted the action potential threshold toward more hyperpolarized membrane potentials (arrowheads indicate action potential threshold as in Fig. 2D), and the frequency of firing was increased. Patch whole-cell recordings were performed in current-clamp mode. Current pulses of 1 s duration were applied at the resting membrane potential (in this case, approximately −80 mV) to elicit action potentials. E, Application of 4-AP (40 μm) also induced a protracted shift of the threshold for action potential generation toward hyperpolarization (from −51.9 ± 2.6 mV before 4-AP application to −59.1 ± 2.4 mV 40 min after 4-AP application, n = 9, white bar labeled 4-AP) similarly to an LTP-IE-inducing HFS. Delivery of HFS in the presence of 4-AP (4-AP + HFS) did not further shift the action potential threshold (t = 0.21, NS, n = 9), suggesting that HFS acts at least in part by reducing ID. A transient (15 min) application of 4-AP (40 μm) also induced a persistent shift of the threshold for action potential generation from baseline that was significant for over 40 min after washout (column marked 1 in the graph; t = 3.379, n = 6, p = 0.010, at 40 min after washout). In a separate set of cells, synaptic transmission was blocked by application of the AMPA inhibitor CNQX (10 μm), the NMDA inhibitor d-AP-5 (50 μm), the mGluR5 inhibitor MPEP (10 μm), the GABAA inhibitor bicuculline (30 μm), and the GABAB inhibitor SCH50911 (20 μm) 15 min before the transient (15 min) application of 4-AP (40 μm). Again, a persistent shift of the threshold for action potential generation from baseline was observed that was significant for over 40 min after washout (column marked 2 in the graph; t = 2.92, n = 6, p = 0.017, at 40 min after washout). A persistent shift of the threshold for action potential generation was also induced by a transient (15 min) application of the specific mGluR5 agonist CHPG (200 μm) (t = 6.292, n = 5, p = 0.002, at 40 min after washout). F, Activation of mGluR5 by 200 μm CHPG reduced the whole-cell current by 13.2 ± 1.96% compared with control. Subsequent application of 1 μm α-DTX to block the ID current significantly reduced the whole-cell current to 23.9 ± 3.73% compared with control (t = 3.43, **p < 0.01, n = 8). When α-DTX was applied first, it reduced the whole-cell current by 22.7 ± 5.14%, and subsequent application of CHPG no longer had an effect on the whole-cell current (23.3 ± 5.18%, t = 1.04, NS, n = 6). Sample recordings are shown in G. G, Top panel shows the voltage protocol used in patch whole cell to obtain the records shown below and in I. Cells were held in voltage-clamp mode at −70 mV, and a 2000 ms pulse to −100 mV was applied so that a maximal amount of ID was available for activation during subsequent voltage steps. This was followed by a 100 ms pulse to −40 mV to inactivate the A-current. Voltage steps from −50 to +40 mV then were applied for 500 ms, and these were used for analysis of ID. Middle panel demonstrates ID by subtracting the recording made in the presence of α-DTX (1 μm) from the control recording (Bekkers and Delaney, 2001). Bottom panel shows ID during application of CHPG (200 μm) in the same cell as the panel above. CHPG blocked 56.9 ± 4.8% (n = 8) of the ID. H, CHPG had no effect on whole-cell current (left) and I–V relationship (right) when applied after application of α-DTX, indicating that CHPG did not affect currents other than the ID. Blue traces and blue line (diamond) in the graph represent total K+ whole-cell current in aCSF; red traces and red line (triangles) in the graph represent K+ whole-cell current in the presence of α-DTX; green traces and green line (squares) in the graph represent K+ whole-cell current in the presence of α-DTX and CHPG.

As shown in Figure 4B, using combined DNA microarray and qPCR, we observed increased expression of the potassium channel Kv1.2 in post-dependent rats at the time points indicated in Figure 3 (4–6 weeks for alcohol dependent; 1–2 weeks for cocaine and heroin LgA). Consistently, Kv1.2 protein was significantly increased in the jcBNST of rats with a history of alcohol dependence by Western blotting (Fig. 4C). Kv1.2 is a member of the Kv1 family of potassium channels implicated in mediating the slowly inactivating 4-aminopyridine- and α-DTX-sensitive D-type K+ current (Shen et al., 2004). The α-DTX-sensitive D-type K+ current is a slow inactivating transient current first identified by Storm (1988) in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons by its ability to delay firing action potentials. The ID current is selectively blocked by α-DTX and by micromolar concentrations of 4-aminopyridine (Storm, 1988; Coetzee et al., 1999). The ID current is known to be regulated by metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) (Wu and Barish, 1999) and controls action potential threshold in various neuronal types (Storm, 1988; Strom, 1993; Coetzee et al., 1999; Bekkers and Delaney, 2001; Kröner et al., 2005; Guan et al., 2007). Consistent with these previous findings, bath application of α-DTX (1 μm) or 4-AP (40 μm) induced a long-lasting shift of the threshold for action potential generation toward more hyperpolarized membrane potentials in jcBNST neurons (Fig. 4D,E). Delivery of HFS after application of 4-AP did not further shift the AP threshold (from −59.1 ± 2.4 mV before HFS to −60.9 ± 2.8 mV 40 min after HFS; t = 0.21, NS, n = 9) (Fig. 4E). A transient application (15 min) of 4-AP induced a protracted shift of the threshold for action potential generation toward hyperpolarization that was unchanged by previous application of inhibitors of synaptic transmission that were maintained for the duration of the recordings (Fig. 4E). This suggests that the persistent shift of the threshold for action potential generation induced by a transient application of 4-AP was attributable to inhibition of the postsynaptic ID current. A transient application (15 min) of the selective mGluR5 agonist (RS)-2-chloro-5-hydroxyphenylglycine (CHPG) (200 μm) also induced a protracted shift of the threshold for action potential generation toward hyperpolarization (Fig. 4E). The expression of the ID current in jcBNST neurons was confirmed in patch whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings according to the protocol of Bekkers and Delaney (2001) (Fig. 4F–H). As expected, bath application of CHPG (200 μm) reduced the ID current (56.9 ± 4.8%, n = 8) in jcBNST neurons (Fig. 4F,G). Application of α-DTX before application of CHPG resulted in whole-cell currents and I–V relationships that were identical (Fig. 4H), indicating that the effect of CHPG on the whole-cell current was mediated exclusively through the ID current. Together, these results indicate that the shift of action potential threshold that characterizes LTP-IE in jcBNST neurons is attributable to the inhibition of a mGluR5-modulated postsynaptic ID current.

Enhanced temporal fidelity of firing in jcBNST LTP-IE

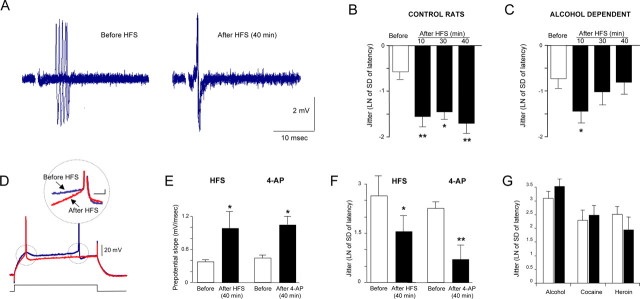

Using extracellular single-unit recordings in the jcBNST in response to stimulation of the stria terminalis, we investigated the variability of the latency to the first spike or “jitter of the spike,” a measure of the temporal fidelity of firing (Pouille and Scanziani, 2001; Sourdet et al., 2003). In the jcBNST of control rats, the jitter of the spike showed a significant and protracted reduction after delivery of HFS of the stria terminalis that lasted for up to 40 min and resulted in increased temporal fidelity of firing (Fig. 5A,B). In the jcBNST of alcohol-dependent rats, the HFS-induced reduction of jitter was only transient, returning to control levels by 30 min after HFS (Fig. 5C). Because extracellular recordings do not allow one to determine the cellular mechanism behind the reduced jitter of the spike that characterizes LTP-IE in the jcBNST, we performed concomitant measures of the prepotential slope and jitter in the same jcBNST neurons of normal rats by intracellular recordings. As shown in Figure 5D–F, we observed that HFS induced a significant increase in the slope of the depolarizing prepotential from 0.38 ± 0.04 to 0.98 ± 0.3 mV/ms 40 min after HFS (p < 0.01, n = 9) (Fig. 5E), which was associated with a significant decrease of the jitter of the spike (2.64 ± 0.6 ms before vs 1.56 ± 0.5 ms 40 min after HFS; p < 0.05, n = 9) (Fig. 5F). Changes in the latency to the first spike as well as in the depolarizing prepotentials may reflect either increases of inward currents, such as Na+ and/or Ca2+-mediated currents, or decreases of outward currents, like the K+-mediated IA or ID (Nisenbaum et al., 1994; Griffin et al., 1996). Therefore, we tested whether bath application of the ID blocker 4-AP at the concentration of 40 μm, which does not block the IA, could mimic both the increase of the slope of the prepotential and the decrease of the jitter. As shown in Figure 5, E and F, the slope of the prepotential of jcBNST neurons was significantly increased from 0.45 ± 0.048 to 1.05 ± 0.15 mV/ms (p < 0.01, n = 9) (Fig. 5E), and the jitter was decreased from 2.32 ± 0.3 to 0.78 ± 0.43 ms, 40 min after 4-AP (40 μm; p < 0.01; n = 9) (Fig. 5F). Conversely, in rats with a history of alcohol, cocaine, or heroin dependence, the jitter of the spike measured by intracellular recordings was not significantly changed at 40 min after HFS (Fig. 5G).

Figure 5.

Activity-dependent increase of temporal fidelity of firing of jcBNST neurons. Extracellular single unit (A–C) and intracellular recordings (D–G) were used to investigate temporal fidelity in the jcBNST. A, Five successive extracellularly recorded action potentials locked to the stimulus applied to the stria terminalis were superimposed. Delivery of HFS reduced the latency to the first spike and jitter of the spike in the jcBNST for a protracted time. B, Quantification of the jitter in jcBNST neurons after HFS in control rats. The natural logarithm of the SD of the latency of action potential was used as a measure of the jitter of spike. In the jcBNST, the jitter was significantly reduced from control for up to 40 min after HFS (after 10 min, t = 6.11, p < 0.01; after 30 min, t = 2.18, p < 0.05; and after 40 min, t = 6.49, p < 0.01; n = 7). C, Conversely, rats with a history of alcohol dependence had only a transient reduction of jitter after HFS (after 10 min, t = 3.68, p < 0.05; after 30 min, t = 1.33, NS from before HFS, and after 40 min, t = 0.53, NS from before HFS; n = 5). D, Sample traces showing action potentials evoked by a 350 ms depolarizing pulse in jcBNST neurons by intracellular recording in control rats before and 40 min after HFS of the stria terminalis demonstrating HFS induced shortening of spike latency. Inset shows superimposed traces from the same neuron showing increased depolarizing prepotential slope after HFS (40 min). E, Average depolarizing prepotential slope was significantly increased 40 min after HFS in control rats (t = −1.89, p < 0.05; n = 9) (left bars). Similarly, bath application of the ID blocker 4-AP (40 μm) mimicked the HFS-induced increase in depolarizing prepotential slope (t = 2.06, p < 0.05, n = 9) (right bars). F, The jitter was significantly decreased in the same recordings 40 min after HFS (t = 2.12, p < 0.05; n = 9) (left bars). Similarly, a decrease of the jitter from was also observed 40 min after 4-AP application (t = 2.97, p < 0.01; n = 9) (right bars). G, In rats with history of alcohol, cocaine, or heroine dependence no significant decreases of jitter were observed 40 min after HFS (t = −1.37, t = −0.83, t = 1.04, NS, respectively, for n = 8, n = 10, n = 9, respectively); white bars indicate jitter of spike before HFS, and black bars indicate jitter of the spike after HFS. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Thus, LTP-IE in the jcBNST is characterized by increased intrinsic excitability attributable to a decrease in the firing threshold and by increased temporal fidelity of firing, both of which depends on the K+-mediated ID and that were not seen in animals with a history of alcohol, cocaine, or heroin dependence.

The impairment of jcBNST LTP-IE in protracted abstinence is associated with activation of the CRF system

The increased anxiety-like behavior and drinking observed during acute withdrawal and protracted abstinence have been attributed to increased CRF activity (Rasmussen et al., 2001; Valdez et al., 2002), including within the BNST (Olive et al., 2002). Drug-seeking behavior previously maintained by various drugs of abuse, including alcohol, cocaine, and heroin, can be reinstated by either exposure to stress or by central administration of CRF in a CRF antagonist-reversible manner (Shaham et al., 2003). Therefore, we performed double in situ hybridization for GABA synthetic enzymes GAD65 and GAD67 and for CRF to investigate the distribution of GABA- and CRF-containing neurons in the jcBNST. We observed that GABAergic neurons are highly represented in the dorsolateral BNST including the jcBNST and show a high degree of colocalization with CRF, especially in the midsection of the dorsolateral BNST and jcBNST (Fig. 6). Previous studies also showed numerous CRF-containing neurons in the lateral BNST (Sawchenko, 1987) as well as a rich plexus of CRF-containing axons and axon collaterals throughout the BNST, suggesting that CRF may regulate neuronal activity in the nucleus. Next, we investigated the potential role of CRF in the impairment of jcBNST LTP-IE during protracted withdrawal in animals with a history of alcohol dependence. Repeated subcutaneous administration of the selective CRF1 receptor antagonist R121919 (formerly referred to as NBI 30775) (Chen et al., 1996) restored normal jcBNST LTP-IE in alcohol post-dependent rats (190.7 ± 1.4%, n = 8, 60 min after HFS), whereas vehicle (aCSF-containing 10% DMSO) had no effect (111.6 ± 1.7%, n = 4) (Fig. 7A). Three intracerebroventricular injections (4 μg in 2 μl) of the selective CRF2 receptor antagonist astressin2-B (A2-B) (Rivier et al., 2002) every 12 h was also ineffective (Fig. 7A). The dose of A2-B was based on previous work (Cottone et al., 2007; Fekete et al., 2007). Repeated intracerebroventricular administration of CRF, but not acute administration of CRF, induced a significant impairment of jcBNST LTP in drug-naive rats that resembled the post-dependent phenotype (Fig. 7B). Together, these results suggest that the CRF system may contribute to dependence-associated changes in the integration properties of jcBNST neurons that can be normalized by a CRF1 receptor antagonist and mimicked by repeated central CRF administration.

Figure 6.

Double in situ hybridization for GAD65 and GAD67 and for CRF in the dorsal BNST. A, A large number of GAD-containing neurons (shown in purple) are present in the jcBNST and in the dorsolateral BNST in general. In situ hybridization signal for CRF (brown grains) was seen in the dorsolateral BNST, including the jcBNST, and were primarily colocalized with GAD65 and GAD67. LV, Lateral ventricle. B, Higher magnification of the area in the dotted box in A shows high level of colocalization of CRF with GAD65 and GAD67 in the midsection of the jcBNST. C, Higher magnification of the two neurons containing CRF and GAD65 and GAD67 signal marked by the arrows in B.

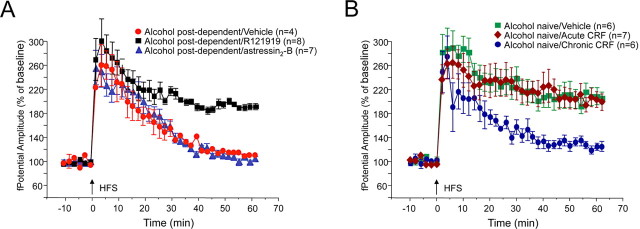

Figure 7.

Disruption of jcBNST LTP in protracted abstinence is attributable to activation of the CRF system. A, Subcutaneous administration of the selective CRF1 receptor antagonist R121919 (three 20 mg/kg injections, 12 h apart) restored normal jcBNST LTP in alcohol post-dependent rats 4 weeks after withdrawal, significantly increasing jcBNST LTP compared with vehicle (20% hydroxypropyl β-cyclodextrin, pH 4.5). Conversely, intracerebroventricular injection for 3 d of the selective CRF2 receptor antagonist A2-B (4 μg/μl in 2 μl every 12 h) did not restore capacity for potentiation of the amplitude of the field potential in alcohol post-dependent rats 4 weeks after withdrawal. BNST slices were prepared 1 h after the final antagonist injection. B, Repeated intracerebroventricular administration of CRF (2 daily injections of 1 μg for 10 d) induced a significant impairment of jcBNST LTP in drug-naive rats, whereas a single administration of CRF (1 μg 2 h before the animals were killed) had no effect.

Discussion

In the present study, we have observed that a history of drug exposure sufficient to produce escalated self-administration produced impairment in a novel form of activity-dependent LTP-IE in jcBNST neurons. This form of plasticity was characterized by a decrease in the firing threshold and an increase in the temporal fidelity of firing of jcBNST neurons that were both long lasting. LTP-IE in the jcBNST was differentially altered in animal models of controlled intake of an abusable drug versus animal models of dependent use at time points during protracted withdrawal that are characterized by behavioral manifestations of a negative emotional state (Koob et al., 2004), such as increased anxiety-like behavior (Zorrilla et al., 2001; Valdez et al., 2002; Zhao et al., 2007; Sommer et al., 2008) and intracranial self-stimulation reward thresholds (Ahmed et al., 2002). Additionally, rats with a history of heroin self-administration also show increased stress-induced reinstatement of heroin-seeking behavior at the time point investigated here (Shalev et al., 2001). Although mounting evidence suggests that changes in the intrinsic membrane properties of neurons may result from exposure to drugs of abuse (Cooper et al., 2003; Dong et al., 2005; Nasif et al., 2005), changes in the capacity for plasticity of intrinsic excitability have not been shown previously as consequences of drug exposure.

Consistent with classic studies showing that potentiation of the population spike can occur independently of EPSP potentiation (Bliss and Lomo, 1973; Miles et al., 2005), the protracted decrease in the firing threshold and increase in the temporal fidelity of firing of jcBNST neurons observed in LTP-IE were accompanied only by a transient EPSP potentiation. In a previous study, an LTP of the field potential in the mouse dorsolateral BNST was interpreted as a form of synaptic potentiation (Weitlauf et al., 2004). The present data show that the LTP of the field potential in the jcBNST is an a population spike manifesting the summation of action potentials of jcBNST neurons and cast a new interpretation on the previous work.

The decrease in the firing threshold of jcBNST neurons observed in LTP-IE was found to be regulated by the ID current. The repertoire, expression, and regulation of K+ channels are believed to be key factors in neuronal integration (Marder and Goaillard, 2006). Previous studies indicate that changes in K+ channel expression levels can alter intrinsic neuronal excitability (Dong et al., 2006) and capacity for plasticity of intrinsic excitability (Wang et al., 2006). Loss of LTP-IE of jcBNST neurons during protracted abstinence from alcohol, cocaine, and heroin self-administration was associated with increased expression of the Kv1.2 K+ channel, a main contributor to the ID current (Shen et al., 2004). Because increased expression of Kv1.2 was correlated with changes in excitability in other neuronal systems (Tsaur et al., 1992), this observation provides a potential mechanism contributing to Kv1.2 regulation. Additionally, a key mechanism of regulation of Kv1.2 appears to be phosphorylation-dependent trafficking of a fraction of the channel (Nesti et al., 2004). If this mechanism mediates the activity-dependent inactivation of Kv1.2 induced by HFS in jcBNST neurons, an increased pool of Kv1.2 consequent to its increased expression may be sufficient to prevent its downregulation in LTP-IE. Activity- and NMDA-dependent inactivation of another Kv1 channel, Kv1.1, has also been demonstrated in hippocampal CA1 neurons (Raab-Graham et al., 2006).

LTP-IE in the jcBNST was also found to be characterized by increased temporal fidelity of firing of jcBNST neurons, which also depended on the ID current and was impaired in animals with a history of alcohol, cocaine, or heroin dependence. At the circuit level, computational theory predicts that increased temporal fidelity of neuronal firing translates into more efficient use of the capacity of neural connections (Singer, 1999). At the cellular level, the ability to modify the extent and fidelity in which synaptic potentials are translated into activity outputs is believed to be a central feature of the integration properties of neurons (Singer, 1999). Forms of plasticity of intrinsic excitability have been proposed to be adaptive mechanisms directed toward maintaining the homeostasis of network excitability in the CNS in response to increases in synaptic inputs (Turrigiano, 1999). The glutamatergic projection to the jcBNST originates in the posterior BLA (Dong et al., 2000). In turn, the jcBNST projects back to the anterior BLA and to the CeA. Its lack of cells expressing glutamatergic markers (Hur and Zaborszky, 2005) and abundance of GABAergic cell bodies (Fig. 6) (Sun and Cassell, 1993; Veinante et al., 1997) suggest that the jcBNST is likely to play an inhibitory role on the amygdala. Therefore, the ability of jcBNST neurons to increase their ensemble activity through increased firing rate and temporal fidelity of their firing could provide a more efficient inhibitory influence on the CeA output at times of greater BLA activation. The BLA is activated in humans during drug craving elicited by exposure to drug-related environmental cues (Bonson et al., 2002) and is involved in contextual reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior in experimental animals (Hayes et al., 2003). Thus, reduced capacity for LTP-IE and temporal fidelity of firing of jcBNST neurons could be a compensatory response to excessive activation of the BLA in dependent animals and could result in inadequate feedback inhibition of the CeA. Unrestrained CeA activation would be expected to result in increased emotional arousal through its various projection areas, including the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus and the lateral hypothalamus that are believed to be key in the expression of “emotional memories” by interfacing central stress and autonomic systems (LeDoux, 1993). The lateral hypothalamus has been found to undergo structural changes during cocaine escalation (Ahmed et al., 2005). Loss of jcBNST LTP-IE also will directly affect target regions of the jcBNST itself and, indirectly, of other BNST nuclei that in part overlap with those of the CeA (Dong et al., 2000).

Symptoms of a negative emotional state that emerge during drug withdrawal are believed to be attributable to adaptive changes in the brain reward and stress neurocircuitry that develop during excessive drug intake and persist in a latent state after acute withdrawal (Koob et al., 1998). The alteration of jcBNST plasticity described here was not seen during acute withdrawal in alcohol-dependent rats but became manifest only during protracted withdrawal. Similarly, enhanced LTP in the BLA–CeA pathway was seen after 14 d but not 1 d withdrawal from a 7 d cocaine treatment (Fu et al., 2007). Together, these data suggest that, in addition to acute drug opponent-process adaptations (Koob et al., 1998), drug use also may produce delayed functional changes that are specific to protracted withdrawal. The latter may be especially significant for the neurobiology of vulnerability to relapse to drug-taking after the acute withdrawal syndrome has ceased. Spontaneous anxiety-like behavior in rats with a history of alcohol dependence has been found recently to increase during acute withdrawal, then transiently normalize, but then to resurge during protracted withdrawal and has been linked to changes in the extrahypothalamic CRF system (Zhao et al., 2007). Similarly, such anxiety-like states can be retriggered by mild stressors that do not affect animals without a history of dependence, and these stress-like responses are linked to the extrahypothalamic CRF system (Valdez et al., 2002). It is particularly noteworthy that, in protracted abstinence, the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis shows a blunted response, but the extrahypothalamic CRF system remains activated and may even sensitize (Koob and Kreek, 2007). Together, these observations support the hypothesis that distinct neurobiological mechanisms are recruited during early and protracted withdrawal and suggest that the alteration of the LTP-IE described may be specific to protracted withdrawal. In the rat, exposure to stressors reinstates drug-seeking behavior previously maintained by various drugs of abuse, including alcohol, cocaine, and heroin, and administration of CRF antagonists prevents reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior (Shaham et al., 2003). Extracellular CRF is increased during ethanol withdrawal in the BNST (Olive et al., 2002), which has been implicated in CRF-mediated anxiety-like behavior (Sahuque et al., 2006) and stress-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior depends on extrahypothalamic CRF in the BNST (Erb and Stewart, 1999; Leri et al., 2002; McFarland et al., 2004). Together with our results, these findings support the hypothesis that extrahypothalamic CRF signaling may regulate neuronal circuits associated with protracted abstinence and stress-induced reinstatement.

In conclusion, our results show that the integration properties of jcBNST neurons are regulated by a novel form of neural plasticity characterized by changes in the intrinsic excitability and temporal fidelity of jcBNST neurons, which was altered in a CRF-dependent manner during protracted withdrawal. These results suggest that CRF-mediated impairment of jcBNST neuronal plasticity are associated with the persistent emotional dysregulation after chronic drug exposure and provide a novel neurobiological target for the mechanisms by which stress and protracted abstinence symptoms perpetuate alcohol and drug dependence.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AA016587 (W.F.), DA013821, AA013191 (P.P.S.), AA008459, DA004043, DA004398, and AA006420 (G.F.K.) and by the Pearson Center for Alcoholism and Addiction Research. A portion of this work was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. We thank Drs. Floyd Bloom and Paul Kenny of The Scripps Research Institute, Elisabeth Walcott of the Neuroscience Institute, and Sascha du Lac of The Salk Institute for critical review of this manuscript, Drs. Bert Weiss and Tamas Bartfai of The Scripps Research Institute and Attila Szücs of the Institute for Nonlinear Science (University of California, San Diego) for discussion, and Dr. Caroline M. Lanigan for review of statistical analyses, Lena van der Stap for assistance with the analysis of microarray data, and Mike Arends for editorial assistance.

References

- Ahmed SH, Kenny PJ, Koob GF, Markou A. Neurobiological evidence for hedonic allostasis associated with escalating cocaine use. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:625–626. doi: 10.1038/nn872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed SH, Lutjens R, van der Stap LD, Lekic D, Romano-Spica V, Morales M, Koob GF, Repunte-Canonigo V, Sanna PP. Gene expression evidence for remodeling of lateral hypothalamic circuitry in cocaine addiction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11533–11538. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504438102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aizenman CD, Linden DJ. Rapid, synaptically driven increases in the intrinsic excitability of cerebellar deep nuclear neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:109–111. doi: 10.1038/72049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armano S, Rossi P, Taglietti V, D'Angelo E. Long-term potentiation of intrinsic excitability at the mossy fiber-granule cell synapse of rat cerebellum. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5208–5216. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-14-05208.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekkers JM, Delaney AJ. Modulation of excitability by alpha-dendrotoxin-sensitive potassium channels in neocortical pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:6553–6560. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-17-06553.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss TV, Lomo T. Long-lasting potentiation of synaptic transmission in the dentate area of the anaesthetized rabbit following stimulation of the perforant path. J Physiol. 1973;232:331–356. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonson KR, Grant SJ, Contoreggi CS, Links JM, Metcalfe J, Weyl HL, Kurian V, Ernst M, London ED. Neural systems and cue-induced cocaine craving. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26:376–386. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carboni E, Silvagni A, Rolando MT, Di Chiara G. Stimulation of in vivo dopamine transmission in the bed nucleus of stria terminalis by reinforcing drugs. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1–5. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-20-j0002.2000. RC102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Dagnino R, Jr, De Souza EB, Grigoriadis DE, Huang CQ, Kim KI, Liu Z, Moran T, Webb TR, Whitten JP, Xie YF, McCarthy JR. Design and synthesis of a series of non-peptide high-affinity human corticotropin-releasing factor1 receptor antagonists. J Med Chem. 1996;39:4358–4360. doi: 10.1021/jm960149e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Bohanick JD, Nishihara M, Seamans JK, Yang CR. Dopamine D1/5 receptor-mediated long-term potentiation of intrinsic excitability in rat prefrontal cortical neurons: Ca2+-dependent intracellular signaling. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:2448–2464. doi: 10.1152/jn.00317.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Tilley MR, Wei H, Zhou F, Zhou FM, Ching S, Quan N, Stephens RL, Hill ER, Nottoli T, Han DD, Gu HH. Abolished cocaine reward in mice with a cocaine-insensitive dopamine transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9333–9338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600905103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SA, O'Dell LE, Hoefer ME, Greenwell TN, Zorrilla EP, Koob GF. Unlimited access to heroin self-administration: independent motivational markers of opiate dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2692–2707. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee WA, Amarillo Y, Chiu J, Chow A, Lau D, McCormack T, Moreno H, Nadal MS, Ozaita A, Pountney D, Saganich M, Vega-Saenz de Miera E, Rudy B. Molecular diversity of K+ channels. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;868:233–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper DC, Moore SJ, Staff NP, Spruston N. Psychostimulant-induced plasticity of intrinsic neuronal excitability in ventral subiculum. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9937–9946. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-30-09937.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottone P, Sabino V, Nagy TR, Coscina DV, Zorrilla EP. Feeding microstructure in diet-induced obesity susceptible versus resistant rats: central effects of urocortin 2. J Physiol. 2007;583:487–504. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.138867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cudmore RH, Turrigiano GG. Long-term potentiation of intrinsic excitability in LV visual cortical neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:341–348. doi: 10.1152/jn.01059.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuello A, Carson S. Microdisection of fresh rat brain tissue slices. In: Cuello A, editor. Brain microdissection techniques. New York: Wiley; 1983. pp. 37–126. [Google Scholar]

- Daoudal G, Hanada Y, Debanne D. Bidirectional plasticity of excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP)-spike coupling in CA1 hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14512–14517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222546399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debanne D, Daoudal G, Sourdet V, Russier M. Brain plasticity and ion channels. J Physiol Paris. 2003;97:403–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jphysparis.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delfs JM, Zhu Y, Druhan JP, Aston-Jones G. Noradrenaline in the ventral forebrain is critical for opiate withdrawal-induced aversion. Nature. 2000;403:430–434. doi: 10.1038/35000212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai NS, Rutherford LC, Turrigiano GG. Plasticity in the intrinsic excitability of cortical pyramidal neurons. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:515–520. doi: 10.1038/9165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H, Petrovich GD, Swanson LW. Organization of projections from the juxtacapsular nucleus of the BST: a PHAL study in the rat. Brain Res. 2000;859:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02246-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Nasif FJ, Tsui JJ, Ju WY, Cooper DC, Hu XT, Malenka RC, White FJ. Cocaine-induced plasticity of intrinsic membrane properties in prefrontal cortex pyramidal neurons: adaptations in potassium currents. J Neurosci. 2005;25:936–940. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4715-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Green T, Saal D, Marie H, Neve R, Nestler EJ, Malenka RC. CREB modulates excitability of nucleus accumbens neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:475–477. doi: 10.1038/nn1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont EC, Mark GP, Mader S, Williams JT. Self-administration enhances excitatory synaptic transmission in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:413–414. doi: 10.1038/nn1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egli RE, Winder DG. Dorsal and ventral distribution of excitable and synaptic properties of neurons of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:405–414. doi: 10.1152/jn.00228.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egorov AV, Heinemann U, Müller W. Differential excitability and voltage-dependent Ca2+ signalling in two types of medial entorhinal cortex layer V neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:1305–1312. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiler WJ, 2nd, Seyoum R, Foster KL, Mailey C, June HL. D1 dopamine receptor regulates alcohol-motivated behaviors in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Synapse. 2003;48:45–56. doi: 10.1002/syn.10181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiler WJ, 2nd, Hardy L, 3rd, Goergen J, Seyoum R, Mensah-Zoe B, June HL. Responding for brain stimulation reward in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in alcohol-preferring rats following alcohol and amphetamine pretreatments. Synapse. 2007;61:912–924. doi: 10.1002/syn.20437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epping-Jordan MP, Markou A, Koob GF. The dopamine D-1 receptor antagonist SCH 23390 injected into the dorsolateral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis decreased cocaine reinforcement in the rat. Brain Res. 1998;784:105–115. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb S, Stewart J. A role for the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, but not the amygdala, in the effects of corticotropin-releasing factor on stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-20-j0006.1999. RC35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb S, Funk D, Borkowski S, Watson SJ, Akil H. Effects of chronic cocaine exposure on corticotropin-releasing hormone binding protein in the central nucleus of the amygdala and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. Neuroscience. 2004;123:1003–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekete EM, Inoue K, Zhao Y, Rivier JE, Vale WW, Szücs A, Koob GF, Zorrilla EP. Delayed satiety-like actions and altered feeding microstructure by a selective type 2 corticotropin-releasing factor agonist in rats: intra-hypothalamic urocortin 3 administration reduces food intake by prolonging the post-meal interval. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:1052–1068. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Pollandt S, Liu J, Krishnan B, Genzer K, Orozco-Cabal L, Gallagher JP, Shinnick-Gallagher P. Long-term potentiation (LTP) in the central amygdala (CeA) is enhanced after prolonged withdrawal from chronic cocaine and requires CRF1 receptors. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:937–941. doi: 10.1152/jn.00349.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk CK, Zorrilla EP, Lee MJ, Rice KC, Koob GF. Corticotropin-releasing factor 1 antagonists selectively reduce ethanol self-administration in ethanol-dependent rats. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin NW, Richardson HN, Cole M, Koob GF. Vapor inhalation of alcohol in rats. Curr Protoc Neurosci. 2008 doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0929s44. Chapter 9:Unit 9.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin JD, Kaple ML, Chow AR, Boulant JA. Cellular mechanisms for neuronal thermosensitivity in the rat hypothalamus. J Physiol. 1996;492:231–242. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan D, Lee JC, Higgs MH, Spain WJ, Foehring RC. Functional roles of Kv1 channels in neocortical pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:1931–1940. doi: 10.1152/jn.00933.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman DA, Owens MJ, Skelton KH, Thrivikraman KV, Nemeroff CB. The corticotropin-releasing factor1 receptor antagonist R121919 attenuates the behavioral and endocrine responses to stress. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304:874–880. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.042788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammack SE, Mania I, Rainnie DG. Differential expression of intrinsic membrane currents in defined cell types of the anterolateral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98:638–656. doi: 10.1152/jn.00382.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes RJ, Vorel SR, Spector J, Liu X, Gardner EL. Electrical and chemical stimulation of the basolateral complex of the amygdala reinstates cocaine-seeking behavior in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;168:75–83. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1328-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hur EE, Zaborszky L. Vglut2 afferents to the medial prefrontal and primary somatosensory cortices: a combined retrograde tracing in situ hybridization study [corrected] J Comp Neurol. 2005;483:351–373. doi: 10.1002/cne.20444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izzo E, Sanna PP, Koob GF. Impairment of dopaminergic system function after chronic treatment with corticotropinreleasing factor. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;81:701–708. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob G, Kreek MJ. Stress, dysregulation of drug reward pathways, and the transition to drug dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1149–1159. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.05030503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Sanna PP, Bloom FE. Neuroscience of addiction. Neuron. 1998;21:467–476. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80557-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Ahmed SH, Boutrel B, Chen SA, Kenny PJ, Markou A, O'Dell LE, Parsons LH, Sanna PP. Neurobiological mechanisms in the transition from drug use to drug dependence. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;27:739–749. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kröner S, Rosenkranz JA, Grace AA, Barrionuevo G. Dopamine modulates excitability of basolateral amygdala neurons in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93:1598–1610. doi: 10.1152/jn.00843.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larriva-Sahd J. Juxtacapsular nucleus of the stria terminalis of the adult rat: extrinsic inputs, cell types, and neuronal modules: a combined Golgi and electron microscopic study. J Comp Neurol. 2004;475:220–237. doi: 10.1002/cne.20185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux JE. Emotional memory: in search of systems and synapses. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;702:149–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb17246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leri F, Flores J, Rodaros D, Stewart J. Blockade of stress-induced but not cocaine-induced reinstatement by infusion of noradrenergic antagonists into the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis or the central nucleus of the amygdala. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5713–5718. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05713.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System, User Bulletin 2, PE Applied Biosystems. 1997 [Google Scholar]