Abstract

We developed 2bF9 transgenic mice in a hemophilia B mouse model with the expression of human factor IX (FIX) under control of the platelet-specific integrin αIIb promoter, to determine whether ectopically expressing FIX in megakaryocytes can enable the storage of FIX in platelet α-granules and corrects the murine hemophilia B phenotype. FIX was detected in the platelets and plasma of 2bF9 transgenic mice by both antigen and activity assays. Approximately 90% of total FIX in blood was stored in platelets, most of which is releasable on activation of platelets. Immunostaining demonstrated that FIX was expressed in platelets and megakaryocytes and stored in α-granules. All 2bF9 transgenic mice survived tail clipping, suggesting that platelet-derived FIX normalizes hemostasis in the hemophilia B mouse model. This protection can be transferred by bone marrow transplantation or platelet transfusion. However, unlike our experience with platelet FVIII, the efficacy of platelet-derived FIX was limited in the presence of anti-FIX inhibitory antibodies. These results demonstrate that releasable FIX can be expressed and stored in platelet α-granules and that platelet-derived FIX can correct the bleeding phenotype in hemophilia B mice. Our studies suggest that targeting FIX expression to platelets could be a new gene therapy strategy for hemophilia B.

Introduction

Hemophilia B is an X-linked, recessive bleeding disorder that results from a deficiency of blood coagulation factor IX (FIX). Gene therapy is an attractive alternative for hemophilia B treatment because it may provide a continuous level of FIX expressed from the genetically modified cells. Currently, the most common gene therapy strategy for hemophilia B trials attempts to produce FIX with constitutive secretion into plasma to achieve therapeutic effects. Muscle and liver are the 2 main targets for hemophilia B gene therapy using adeno-associated virus vector.1–4 The development of inhibitory antibodies against the exogenous protein or the viral vector remains a major problem in clinical gene transfer trials.5

Platelets, which are produced through hematopoiesis by budding off from megakaryocytes,6 can be a unique target for gene therapy for some diseases because of their special characteristics serving as both storage “depot” and trafficking “vehicle.” α-Granules are the most numerous storage granules in platelets, and many different kinds of protein are stored in α-granules.7 These proteins are either synthesized in platelets or endocytosed from plasma, and they can be secreted after stimulation.8,9 Recent evidence indicates that there are different types of α-granules containing different proteins with distinct functions.10,11

Previous work on factor VIII (FVIII) in hemophilia A mice done by our group and others has demonstrated that targeting FVIII expression to platelets results in storage of FVIII in α-granules12–15 and that this corrects murine hemophilia A even in the presence of high titers of anti-FVIII inhibitory antibodies.15,16 Although coexpression with the FVIII carrier protein, von Willebrand factor (VWF), is important for optimal FVIII synthesis and/or storage in platelets, FVIII can still be stored in α-granules even in the absence of VWF.15,17 These results suggest that α-granules can serve as a storage pool for proteins and can be used as part of a gene therapy strategy. Normally, FIX is synthesized in hepatocytes and is secreted constitutively into the blood circulation. We wanted to explore expression of FIX in platelets to determine whether FIX is stored, released, and effective. We hypothesize that expressing FIX in platelets will enable storage of FIX in platelet α-granules and that it will be locally released on injury, increasing FIX concentration at the local injury site. We developed transgenic mice on a FIX-deficient (FIXnull) background with the expression of FIX under control of the platelet integrin αIIb gene promoter. With this transgenic mouse model, we examined the properties and activity of platelet-derived FIX and evaluated its efficacy.

Methods

Vector construction

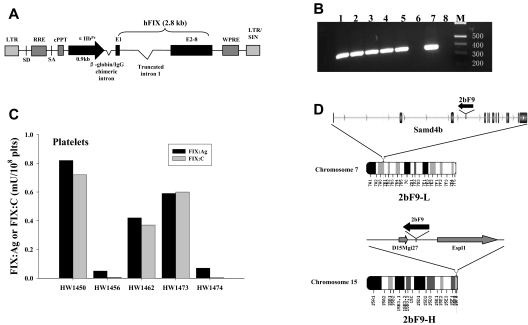

The human FIX cDNA was previously developed by Monahan et al.18 An XhoI site was introduced at the 5′ end of the FIX cDNA by site-directed mutagenesis. FIX cDNA was excised by XhoI and SalI and subcloned into plasmid αIIb-pCIneo generated in our laboratory previously,14 placing the FIX cDNA under control of the αIIb promoter (2bF9). The 2bF9 expression cassette was then excised by I-PpoI and SalI and cloned into lentiviral vector pWPT-2bF8 in place of the 2bF8 cassette13 (Figure 1A). 2bF9 lentivirus (2bF9 LV) was packaged using a similar approach to that previously described for 2bF8 LV.13

Figure 1.

Generation of 2bF9 transgenic mice. (A) Schematic representation of 2bF9 lentiviral vector. A 2.8-kb hFIX cDNA, including a 1.4-kb truncated intron 1 between exon 1 (E1) and the remaining exons (E2-8) is under control of the αIIb promoter (αIIbPr). (B) PCR analysis of mouse genomic DNA showing that 2bF9 transgene is detected in 5 founder mice. The expected 0.35-kb band is seen. Lanes 1 to 5 indicate 5 founder mice; lane 6, FIXnull mouse control; lane 7, pWPT-2bF9 plasmid DNA control; lane 8, water control; and M, Hi-Lo DNA marker. (C) FIX expression in the platelets of 5 founders. Founders HW1473 and HW1474 were developed into the 2 transgenic lines referred to in Figure 2A as 2bF9-H and 2bF9-L, respectively. plts indicates platelets. (D) Integration sites of 2bF9 transgene. (Top) 2bF9 transgene integration site of 2bF9-L mice in the third intron of the Samd4b gene on chromosome 7. Transgene is in reverse transcriptional orientation to Samd4b. (Bottom) Transgene integration site of 2bF9-H mice between the hypothetical gene D15Mgi27 and the Espl1 gene on chromosome 15. 2bF9 was oriented reverse to both genes.

Animal procedures

Animal studies were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Medical College of Wisconsin. Transgenic mice were generated in the Transgenic Core Facility of the Blood Research Institute and Medical College of Wisconsin. All mice used in this study were on the C57BL/6 background. Isoflurane or 2.5% avertin was used for anesthesia.

Lentivirus-mediated transgenesis.

2bF9 transgenic mice were produced by lentivirus-mediated transgenesis as reported.19 Briefly, fertilized eggs were collected from the oviducts of wild-type C57BL/6 mice. Approximately 10 to 100 pL of concentrated 2bF9 LV was injected into the perivitelline space of single-cell mouse embryos. After 24-hour incubation at 37°C, a maximum of 30 2-cell–stage embryos were transferred into 0.5D pseudopregnant females, and then gestation was allowed to continue until pups were born. Transgene-positive mice were identified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of blood-derived genomic DNA using primers in the αIIb promoter and the first exon of FIX cDNA (forward: 5′-AGGTAGCCTTGCAGAAGTTGGTCG-3′; reverse: 5′-ACATTCAGCACTGAGTAGATATCCTAAA-3′). 2bF9 transgenic mice were then bred with FIXnull mice (The Jackson Laboratory) to generate single copy 2bF9 transgenic mice on a FIXnull background. The copy number of 2bF9 transgene was determined by quantitative real-time PCR as previously described13,20 using primers (forward: 5′-GAACCTTGAGAGAGAATGTATGGAAGA-3′; reverse: 5′-GCAACTGCCGCCATTTAAAC-3′) specific for sequence located within the FIX region of the vector to determine copy number of proviral LV DNA. All transgenic mice used in this study were transgene heterozygous.

BMT.

Bone marrow transplantation (BMT) was performed as previously reported15,16 using 1 × 107 bone marrow (BM) mononuclear cells isolated from donor mice for transplantation into lethally irradiated recipients by retro-orbital venous injection in a volume of 400 μL per mouse. BM mononuclear cells from FIXnull mice were used as a transplantation control. Recipient mice were analyzed beginning at 3 weeks after BMT.

Mouse immunization to human FIX.

Mouse immunization was performed by intraperitoneal injection of 200 U/kg recombinant hFIX (rhFIX; BeneFIX, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals) in the presence of adjuvant (Sigma-Aldrich). Two or 3 injections were given at 3-week intervals. Mouse plasma was collected 10 days after the last immunization to determine the titer of FIX antibodies by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and Bethesda assay.

Splenocyte transplantation.

Splenocyte transplantation was performed as previously described.15 Donor mice for splenocyte transplantation were immunized with rhFIX 3 times before transplantation. Splenocytes of immunized FIXnull mice were isolated and transplanted into sublethally irradiated recipients by retro-orbital injection. Two weeks after transplantation, recipients were analyzed for the titer of FIX antibodies and phenotypic correction by tail clip test.

Integration site analysis

The 2bF9 transgene integration site was determined by inverse PCR. Details are provided in the supplemental data (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

FIX assays

FIX:Ag assay.

Blood samples were collected from mice, and plasma or platelet isolation was performed as previously described.15 Platelet lysate was prepared by lysing platelet pellets in 100 μL of 0.5% CHAPS (the zwitterionic detergent, 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate, MP Biomedicals) per 108 platelets. Platelet releasate was prepared as previously described.15 FIX antigen (FIX:Ag) was measured using a human FIX-specific ELISA. A 96-well plate was coated with a mouse anti–hFIX monoclonal antibody (AHIX-5041, Haematologic Technologies) at 2 μg/mL and incubated at 4°C overnight. A total of 100 μL of diluted plasma, platelet lysate, or platelet releasate was added to the anti-hFIX–coated plate and incubated at room temperature for 2 hours. An affinity-purified horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat-anti-hFIX polyclonal antibody (Affinity Biologicals) was used as a detecting antibody. Normal human reference plasma (Precision BioLogic) was used as the standard. This assay is human FIX specific and does not cross-react with mouse FIX. Platelets or plasma from wild-type mice and FIXnull mice were used as negative controls.

FIX activity (FIX:C) assays.

FIX:C was determined by a chromogenic assay and the activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT). The FIX:C chromogenic assay was performed using the BIOPHEN Factor IX kit (Aniara) following the manufacturer's instructions. APTT assays were performed on a STart 4 Hemostasis Analyzer (Diagnostica Stago). Details are provided in the Supplemental data. A standard curve was constructed using serial dilutions of normal human reference plasma in appropriate buffer.

Quantification of antibodies to FIX.

Anti-hFIX antibodies were quantitated by ELISA. A 96-well plate was coated with 1 U/mL rhFIX; 100 μL diluted mouse plasma (1:100 in Tris–bovine serum albumin) was added in duplicate wells and incubated at room temperature for 2 hours. Bound antibodies were detected by a horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti–mouse IgG antibody (Pierce Chemical) at 1:3000 for 2 hours. The plate was developed with ortho-phenylenediamine substrate and read at 490 nm. A standard curve was constructed by plotting a known amount of anti–human FIX monoclonal antibody AHIX-5041.

Quantification of FIX inhibitory antibodies.

The titers of FIX inhibitory antibodies were determined by modified Bethesda assay.21 Sequential dilutions of mouse plasma were incubated with an equal volume of normal human plasma at 37°C for 2 hours, and residual FIX:C was subsequently measured using the chromogenic assay. One Bethesda unit (BU) is the amount of antibody that will inactivate 50% of normal human FIX:C.

Immunostaining and Western blot analysis of FIX

The localization of FIX transgene protein in 2bF9 mice was determined by immunofluorescent confocal microscopy, immunogold-labeled electron microscopy, and immunohistochemical (IHC) staining. The physical properties of FIX were analyzed by Western blot. Details are provided in the Supplemental data.

Phenotypic correction

Tail clip survival tests were performed to assess phenotypic correction as previously described.15 Eight- to 20-week-old mice were selected for the test. For BMT recipients, the test was performed 8 weeks after BMT. For splenocyte-recipient mice, the test was performed 5 to 6 weeks after transplantation. For platelet or rhFIX infusion studies, infusions were performed by retro-orbital injections. Tail clipping was carried out 10 minutes, 24 hours, and 48 hours after platelet infusion or 5 minutes after rhFIX infusion. Whole blood clotting time (CT) was determined by rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) analysis. Details are provided in the Supplemental data.

Statistical analysis

All results are shown as mean plus or minus SD, and the significance of differences was evaluated by a 2-tailed Student t test. A P value less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Generation of 2bF9 transgenic mice

2bF9 LV in which hFIX cDNA is under control of the αIIb promoter was used to generate 2bF9 transgenic mice. Five founder mice were identified as transgene positive by PCR analysis (Figure 1B). FIX expression was demonstrated in the platelets of the 5 founders by platelet lysate FIX:Ag assay. The detection limit of this assay is 0.04 mU/108 platelets. The FIX:Ag in the founders ranged from 0.05 to 0.82 mU/108 platelets. The FIX:C in platelet lysates were determined by APTT assay. The FIX:C levels were comparable with their corresponding FIX:Ag levels, except for 2 founders with lower FIX:Ag levels that had undetectable FIX:C (Figure 1C).

FIX expression in 2bF9 transgenic mice

The founders were mated with FIXnull mice to breed 2bF9 transgene into a hemophilia B mouse model. Two lines of 2bF9 transgenic mice with one copy of 2bF9 transgene per haploid genome stably expressing FIX in platelets were chosen for the subsequent studies. The platelet FIX:Ag in the 2 lines was 0.7 plus or minus 0.1 mU/108 platelets (named 2bF9-L, derived from HW1474) and 14.4 plus or minus 2.9 mU/108 platelets (named 2bF9-H, derived from HW1473; Figure 2A). Single 2bF9 transgene integration sites were determined in the 2 lines by inverse PCR (Figure 1D). The transgene insertion site of 2bF9-L mice is on chromosome 7, within the third intron of the sterile α-motif domain containing 4B (Samd4b) gene. The transgene is in reverse transcriptional orientation to the gene. For 2bF9-H mice, the insertion site is in an intergenic region of chromosome 15. The nearest flanking genes are a hypothetical gene D15Mgi27, 4.3 kb from the 3′ end of the transgene, and extra spindle poles-like 1 (Espl1) gene, 10.9 kb from the 5′ end of the transgene. The transgene was in reverse transcriptional orientation to both of these genes.

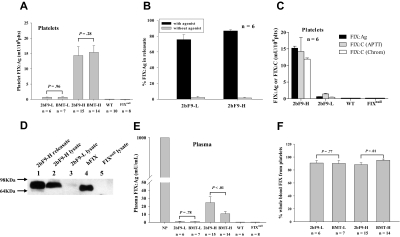

Figure 2.

Characterization of FIX in 2bF9 transgenic mice and BMT recipients. (A) Quantitative evaluation of human FIX:Ag levels in mouse platelets. FIX:Ag was detected in platelet lysates from 2bF9 mice and BMT recipients. BMT-L indicates FIXnull mice that received 2bF9-L BM; BMT-H, FIXnull mice that received 2bF9-H BM; and WT, wild-type mice. (B) Platelet FIX was released from 2bF9-L and 2bF9-H mice by platelet agonist activation. (C) Comparison of platelet FIX:C with FIX:Ag level in 2bF9-L and 2bF9-H mice. FIX:C were measured by APTT assay and chromogenic assay (Chrom). Platelets from WT and FIXnull mice were used as negative controls. (D) Western blot of FIX in platelet releasate and lysates. Lane 1 indicates releasate of stimulated platelets from 2bF9-H mice; lane 2, platelet lysate of 2bF9-H mice; lane 3, platelet lysate of 2bF9-L mice; lane 4, FIX from normal human plasma (Haematologic Technologies) as a control; and lane 5, platelet lysate from FIXnull mice. (E) Quantitative evaluation of FIX:Ag levels in mouse plasma. FIX:Ag was detected in both 2bF9 and BMT recipient plasma. (F) Platelet FIX:Ag as a percentage of whole blood FIX:Ag in 2bF9 and BMT mice. These results demonstrate that FIX was detected in 2bF9 transgenic platelets and is releasable.

By assuming plasma is 50% of the whole blood volume and the average platelet number of 2bF9 transgenic mice is approximately 7 × 108 platelets/mL, the levels of platelet FIX:Ag in the 2 lines are equivalent to approximately 1% and 20% of FIX in normal whole blood, respectively. To ensure this platelet FIX can be released after agonist-induced platelet activation, platelets from 2bF9 mice were incubated with agonist mixture (epinephrine, adenosine diphosphate, and the thrombin receptor-activation peptide) or buffer control. The releasates and residual platelets were collected after stimulation for the FIX:Ag assay. Approximately 75.7% plus or minus 6.3% and 86.7% plus or minus 1.5% of platelet FIX in 2bF9-L and 2bF9-H mice, respectively, were released under agonist stimulation (Figure 2B), demonstrating that most of the platelet FIX is releasable.

The functional activity of platelet FIX was examined by both APTT assay and chromogenic assay (Figure 2C). We found that the chromogenic assay gave higher sensitivity and less variable results. Comparing FIX:C with FIX:Ag, platelet FIX had greater than 75% activity relative to antigen for both 2bF9-L and 2bF9-H mice. This suggests that most of the FIX can undergo γ-carboxylation in mouse platelets. To evaluate the properties of platelet FIX protein, mouse platelet lysates and releasates were analyzed by Western blot for FIX. The results show that the apparent molecular weight of platelet FIX is slightly larger than normal human plasma FIX (Figure 2D), which agrees with a previous in vitro study done in a human hematopoietic cell line by others,22 suggesting the existence of a different pattern of glycosylation in megakaryocytes compared with the normal FIX synthesis in hepatocytes.

FIX:Ag was also detectable in the plasma of 2bF9 transgenic mice. The average levels were 1.0 plus or minus 0.3 mU/mL and 24.3 plus or minus 7.3 mU/mL in 2bF9-L and 2bF9-H mice, respectively (Figure 2E). The detection limit of this assay is 0.08 mU/mL. To evaluate the distribution of FIX between plasma and platelets, we normalized FIX:Ag levels to total whole blood FIX content and compared platelet-lysate FIX:Ag to total FIX:Ag. Approximately 90% of whole blood FIX was stored in platelets of both 2bF9-L and 2bF9-H mice (Figure 2F).

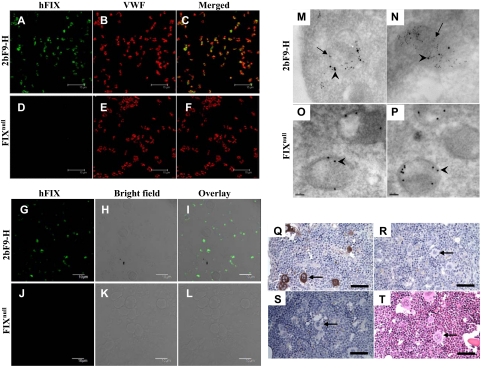

The localization of FIX in 2bF9 transgenic platelets

To address the localization of FIX protein in platelets, immunofluorescent confocal microscopy was performed to visualize FIX in transgenic platelets. FIX was detected in the platelets of 2bF9 transgenic mice and appeared to be colocalized with mouse endogenous VWF as observed in merged images of FIX and VWF staining (Figure 3A-F), suggesting an α-granule localization. No FIX was detected in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (Figure 3G-L).

Figure 3.

Immunostaining of FIX in 2bF9 mice. (A-F) Confocal microscopy study of FIX in platelets. Platelets isolated from 2bF9-H (A-C) and FIXnull mice (D-F) were immunofluorescently stained for FIX (green) and VWF (red). The merged images (C,F) show that FIX was expressed in 2bF9 transgenic platelets and colocalized with VWF. Bars represent 15 μm. (G-L) Confocal microscopy study of FIX in mononuclear cells. Mononuclear cells and platelets isolated from 2bF9-H (G-I) or FIXnull (J-L) mice were stained for FIX (green). FIX was detected in 2bF9-H platelets, but no FIX was detected in mononuclear cells. Bars represent 10 μm. (M-P) Immunoelectron microscopy study of FIX in platelets. Platelets from 2bF9-H (M-N) and FIXnull mice (O-P) were immunogold stained for FIX (5-nm colloidal gold, indicated by arrows) and VWF (10-nm colloidal gold, indicated by arrowheads). FIX colocalized with VWF in α-granules. Bars represent 100 nm. (Q-T) Femoral marrow from 2bF9-H (Q,S-T) and FIXnull mice (R) were immunostained for FIX (Q-R) or with an isotype control (S). 2bF9-H marrow was also stained with hematoxylin and eosin (T) to demonstrate the morphology of megakaryocytes. FIX protein was demonstrated in megakaryocytes of 2bF9-H mice. Arrows point to representative megakaryocytes in each figure. Bars represent 50 μm. These results demonstrate that FIX was expressed in platelet lineage cells and stored in the platelet α-granules of 2bF9 transgenic mice. Confocal images (A-L) were acquired using an Olympus FV-1000-MPE Multiphoton Confocal Microscope (Olympus Corporation) with a 100×/1.4 NA oil objective with 2×digital zoom into Imaging Software FV10-ASW Version 2.00a (Flowview Software) using Vectashield Mounting Medium (Vector Labs). Cofocal specimens were mounted using Vectashield Mounting Medium (Vector Labs). EM images (M-P) were acquired using a JEOL JEM2100 Electron Microscope (JEOL USA Inc.) at 100 000× magnification with a Gatan Ultrascan 1000 CCD Camera (Gatan Inc) into Digital Micrograph Software Version GMS 1.8.4 (Gatan Inc). Immunohistochemistry images (Q-T) were acquired using a Nikon Eclipse E600 Microscope (Nikon) with a 40×/0.75 NA objective using a SPOT Insight Firewire Color Mosaic Model 11.2 Digital Camera (SPOT Insight Solutions) into SPOT Software Version 4.1. Immunohistochemistry specimens were mounted using Mounting Medium (Pierce).

Electron microscopy was performed to further confirm the intracellular localization of FIX in 2bF9 transgenic platelets. The results demonstrated that FIX was stored in α-granules together with VWF (Figure 3M-N). FIX was absent from platelets of FIXnull control mice, but VWF storage appeared normal (Figure 3O-P).

To determine whether FIX was expressed in megakaryocytes in BM, femoral BM from 2bF9-H and FIXnull mice was examined by IHC staining. FIX staining was clearly observed in megakaryocytes of 2bF9-H mice, but no observable FIX staining was found in other BM cells examined (Figure 3Q). No staining of FIX was observed in megakaryocytes in FIXnull mice (Figure 3R) or isotype controls (Figure 3S).

BMT from 2bF9 mice to FIXnull mice

To determine whether the clinical efficacy of 2bF9 can be transferred by hematopoietic stem cells, we transplanted BM mononuclear cells from 2bF9 transgenic mice into lethally irradiated FIXnull mice. As expected, the levels of platelet FIX:Ag in recipients were similar to their corresponding donor mice (0.7 ± 0.1 mU/108 platelets in BMT-L mice and 15.4 ± 2.2 mU/108 platelets in BMT-H mice, Figure 2A). FIX:Ag was also detected in the plasma of recipients. No difference of plasma FIX:Ag was found between BMT-L and 2bF9-L mice (Figure 2E). The level of plasma FIX:Ag in BMT-H mice (10.8 ± 2.7 mU/mL) was significantly lower than in 2bF9-H donors (P < .01, Figure 2E). Consequently, the proportion of total FIX stored in platelets was higher in BMT-H mice than in 2bF9-H mice (95% vs 90%, P < .01; Figure 2F). To determine whether this phenomenon was caused by the development of FIX antibodies, we measured FIX antibodies in the plasma of BMT recipients by ELISA. No FIX antibody was detected in either BMT-L or BMT-H mice, suggesting that the decrease of plasma FIX in BMT-H recipients was not caused by host immunity.

To explore whether the plasma FIX in 2bF9 mice is still maintained after the endogenous BM cells were ablated, we transplanted BM mononuclear cells from FIXnull mice into lethally irradiated 2bF9-H mice (named FIXnull/2bF9-H). FIX:Ag in platelets and plasma was measured 5 weeks after transplantation. As expected, no FIX:Ag was detected in the platelets of recipients, whereas FIX:Ag was still detected in the plasma (14.9 ± 1.4 mU/mL, n = 6), with a level lower than that in 2bF9-H mice (P < .01), indicating that this portion of plasma FIX might not originate from platelets or other BM-derived cells, but from some other as-yet undetermined cell type. We also collected organs from FIXnull/2bF9-H mice and analyzed the FIX expression by quantitative real-time (RT)-PCR, IHC, ELISA, and Western blot. The transgene mRNA was detected by quantitative RT-PCR with the highest level in liver, which was only 0.0017-fold of that in 2bF9 transgenic platelets, followed by lung and kidney, with only a trace amount in the heart (supplemental Figure 1). No FIX protein was detected by IHC in any of these tissues (supplemental Figure 2). FIX was also not detected by ELISA or Western blot in tissue lysates (data not shown).

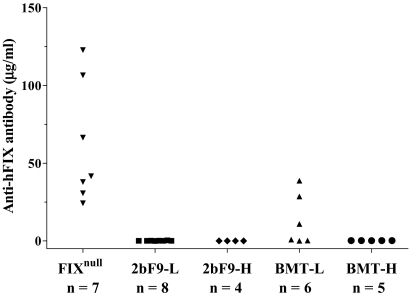

The fact that FIX antibody was undetectable in both BMT-L and BMT-H mice suggests that FIX expression driven by the αIIb promoter did not elicit a measurable immune response in recipient mice. To further investigate whether the recipients were tolerized to FIX, we immunized mice with rhFIX in the presence of adjuvant. After 2 immunizations, 3 of 6 BMT-L mice developed anti-FIX antibodies, but no BMT-H mice developed FIX antibody. In the controls, all of the immunized FIXnull mice developed high levels of FIX antibodies. No 2bF9-L or 2bF9-H transgenic mice developed FIX antibody (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The development of FIX-specific antibodies after identical immunizations with rhFIX in the presence of adjuvant. All of these mice received 2 immunizations of rhFIX (BeneFIX) with adjuvant. All FIXnull mice and 3 of 6 BMT-L mice developed FIX antibodies. None of the 2bF9-L, 2bF9-H, or BMT-H mice developed antibodies. These results indicate that, at some threshold level of expression, 2bF9 may induce immune tolerance in FIXnull mice.

Phenotypic correction by platelet-derived FIX

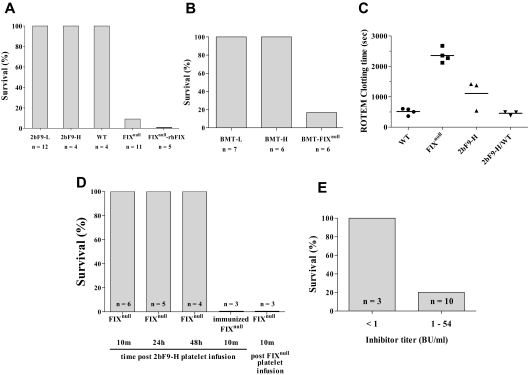

To determine whether platelet-derived FIX can improve hemostasis in hemophilia B mice, we challenged 2bF9 mice and BMT mice with tail clip survival tests. Like wild-type mice, all of the 2bF9-L, 2bF9-H, BMT-L, and BMT-H mice survived the tail clipping challenge, whereas only 1 of 11 FIXnull mice and 1 of 6 BMT-FIXnull (FIXnull mice received BMT from FIXnull mice) control mice survived the same challenge (Figure 5A-B). In the 2bF9-L mice, the total blood FIX is equivalent to only 1.1% of the FIX in normal whole blood. To determine whether a similar level of FIX in plasma can have the same effect, we infused FIXnull mice with rhFIX to a whole blood level of 1.6% and then challenged the mice with tail clipping. In contrast to 2bF9-L, none of the 5 rhFIX-infused FIXnull mice survived tail clipping (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Phenotypic correction of hemophilia B mice. (A) All 2bF9-L and 2bF9-H mice survived the tail clip test. FIXnull-rhFIX are FIXnull mice infused with 1.6% rhFIX (BeneFIX) intravenously. (B) All BMT-L and BMT-H mice survived the tail clip test. BMT-FIXnull are FIXnull mice that received BMT from FIXnull mice as a control. (C) ROTEM clotting time of whole blood. 2bF9-H/WT indicates 2bF9-H mice on wild-type background. Bars represent the mean in each group. Clotting times were significantly decreased in 2bF9-H compared with FIXnull mice (P < .01). No difference was found between WT and 2bF9-H/WT (P = .46). (D) Washed mouse platelets were transfused into FIXnull mice to attain the level of 30% of total recipient platelets. Tail clippings were performed at 10 minutes (10m), 24 hours (24h), and 48 hours (48h) after 2bF9-H platelet infusion. 2bF9-H platelets were also infused into rhFIX-immunized FIXnull mice (immunized FIXnull), which had developed anti-FIX inhibitors ranging from 2 to 12 BU/mL. FIXnull platelets were infused into FIXnull mice (FIXnull platelet infusion) as a control. For the latter 2 groups, tail clippings were performed 10 minutes after infusion. No mice survived in these 2 groups. (E) 2bF9-H mice that received splenocytes from immunized FIXnull mice and had developed FIX inhibitory antibodies were challenged with tail clipping. Splenocyte-transplanted mice with inhibitor titers less than 1 BU/mL were used as controls. Only 2 of 10 mice that maintained inhibitors higher than 1 BU/mL survived tail clipping. These results demonstrate that platelet-derived FIX improved hemostasis in hemophilia B mice but is less effective in mice with anti-FIX inhibitory antibodies.

To further investigate the function of platelet-derived FIX, CT was determined by ROTEM analysis. In contrast to FIXnull mice, the mean CT was shortened from 2357 seconds to 1109 seconds in 2bF9-H mice (P < .01). There were no significant differences between WT and 2bF9-H in wild-type background (2bF9-H/WT) in which normal murine FIX is expressed in addition to platelet FIX (P = .46; Figure 5C).

To examine whether ectopic platelet FIX expression would interfere with normal platelet function or potentially cause prothrombotic complications, we kept 4 2bF9-H mice in a wild-type background and monitored them for more than 1.5 years. All of the mice were healthy until the end of the study with no overt evidence of tumors or health problems related to thrombogenesis. Litter size and survival rate for transgene-positive mice were the same as transgene negatives. These observations, together with the data we obtained from ROTEM analysis, suggest that the current FIX expression levels do not cause any notable gross defects of platelet function and the level is safe for the mice.

To further confirm the benefit of platelet FIX in phenotypic correction, platelets from 2bF9-H mice were transfused into FIXnull mice to attain a 30% proportion of total recipient platelets, and groups of mice were then challenged by tail clipping 10 minutes, 24 hours, and 48 hours after the infusion. All 3 groups survived tail clipping. No FIXnull control mice that received FIXnull platelets survived the same challenge (Figure 5D). These results demonstrate that platelet FIX can be transferred not only by BMT but also by platelet infusion alone.

To assess whether platelet-derived FIX is still functional in the presence of FIX inhibitory antibodies, we repeated the platelet infusion study with rhFIX immunized FIXnull mice, which had developed FIX inhibitory antibodies. None of these mice survived tail clipping after platelet infusion (Figure 5D). We also transplanted splenocytes from immunized FIXnull mice into sublethally irradiated 2bF9-H mice. Two weeks after transplantation, all recipients developed FIX inhibitory antibodies with titers between 1 BU/mL and 124 BU/mL. At 5 to 6 weeks, the inhibitor titers had decreased in all of the recipients, and in 3 mice had dropped to less than 1 BU/mL. At this time, tail clip survival tests were performed. The 3 mice that had inhibitor titers less than 1 BU/mL survived tail clipping, whereas only 2 of 10 mice with inhibitor titers higher than 1 BU/mL survived the test (Figure 5E). Platelet counts in both of these groups were normal (data not shown). The measured platelet FIX:Ag levels in splenocyte recipients were lower than pretransplantation levels (data not shown), but this was thought to be the result of interference in the ELISA assay by the inhibitory antibodies.

Discussion

As a monogenic disorder, hemophilia B is an excellent candidate for gene therapy. Sustained therapeutic expression of FIX has been achieved in preclinical studies using various gene transfer technologies targeted at different tissues, all of which rely on correcting the level of plasma FIX,1–4,23–27 but the results from clinical trials were less promising because of immune response problems.24,28–31 Our studies of FVIII have demonstrated that targeting FVIII expression to platelets can result in a therapeutic, releasable pool in platelet α-granules that corrects the murine hemophilia A phenotype even in the face of inhibitory antibodies.15,16 We wanted to know whether a similar approach can be applied to gene therapy of hemophilia B and hemophilia B with inhibitors. In the current study, we developed transgenic mice expressing FIX under control of the platelet αIIb promoter. We demonstrated that targeting expression of FIX under control of the αIIb promoter results in the releasable storage of FIX in platelet α-granules with a small proportion of constitutively secreted FIX in plasma. Platelet-derived FIX was shown to ameliorate the bleeding phenotype in murine hemophilia B mice but may have limited clinically efficacy in the presence of inhibitory antibodies.

Approximately 90% of the total FIX in 2bF9 transgenic mice is stored in platelets, and most of this is releasable when platelets are activated by agonist stimulation. Confocal microscopy and electron microscopy studies demonstrated that FIX was colocalized with endogenous VWF in platelet α-granules. Unlike FVIII, for which VWF is a carrier protein, no platelet proteins were found to directly associate with FIX by coimmunoprecipitation of platelet lysates (data not shown). Studies of FVIII have shown that VWF is important for optimizing platelet-FVIII expression and/or storage, but the storage of FVIII still occurs, albeit at a lower level, even in the absence of VWF.15,17 Recent studies have shown that not all general secretory proteins are packaged within secretory granules when synthesized by megakaryocytes. Ohmori et al showed that FVII, which is also a vitamin K-dependent protein and shares a high degree of structural and sequence homology with FIX, is found in the cytoplasm rather than in granular storage when targeted to the platelet lineage.32 The storage difference between FIX and FVII is interesting, but the mechanisms are still not yet known. The releasable storage of transgene products makes platelets a unique target for gene therapy of hemophilia because coagulation protein (FVIII or FIX) will be delivered to the right place at the right time, where and when it is needed. The local concentration of these proteins might therefore be greater than if the same concentration of protein were just in plasma.

In 2bF9-L mice, total FIX in blood, including platelet FIX (90%) and plasma FIX (10%), is only approximately 1.1% of FIX in normal whole blood. But even this very low level of 2bF9 transgenic FIX protein is sufficient to normalize hemostasis in the tail clip injury model, whereas a similar level of rhFIX infused in plasma does not have the same efficacy. This demonstrates the advantage of platelet-stored FIX, which can be released under platelet activation, locally increasing the level of FIX at the site of injury and providing improved local hemostatic effectiveness. Furthermore, the life span of platelets is 12 days,33 but the half-life of circulating free FIX is only 18 hours.34 In our studies, the protective effect of platelet FIX can last for 48 hours after platelet infusion, demonstrating that the efficacy of platelet FIX may be maintained longer than plasma FIX. In addition, the existence of a small amount of plasma FIX in 2bF9 gene-transferred animals might be of extra benefit for hemostasis at the site of injury. The level of platelet FIX in 2bF9-H mice is 14.4 mU/108 platelets, which is 20-fold higher than that in 2bF9-L mice. We maintained some 2bF9-H mice on a wild-type background. Although this kind of situation would not occur in the clinic, it is of note that platelet FIX on a wild-type mouse background was not thrombogenic, at least at this level of expression.

Approximately 10% of the total FIX in 2bF9 transgenic mice is found in plasma. A similar level of plasma FIX was detected in BMT-L, but a lower level of plasma FIX was seen in BMT-H mice, indicating that this proportion of plasma FIX is derived from hematopoietic cells, whereas the higher plasma levels measured in BM donors (2bF9-H) may also be derived from other sources. Immunofluorescent confocal microscopy of platelets and IHC staining of BM cells demonstrated that FIX was found only in platelets and megakaryocytes, but not in peripheral mononuclear cells or other BM cells. Therefore, this plasma FIX might be “leaked” from platelet lineage cells because no other protein associates with and helps retain platelet FIX, unlike FVIII, which binds to endogenous platelet VWF that is naturally stored in α-granules. The fact that plasma FIX was decreased in BMT-H, along with the observation that plasma FIX was detected in FIXnull/2bF9-H mice, is indicative that some fraction of plasma FIX in 2bF9-H mice probably originates from expression of FIX in non–BM-derived cells. A small amount of 2bF9 transgene mRNA was detected by quantitative RT-PCR in several tested organs, but protein was not detected in those tissues. The GPIIb gene and αIIb promoter have been demonstrated to be megakaryocyte-platelet specific by many researchers,35–38 but GPIIb has also been found on immature hematopoietic progenitors39,40 and mast cells.41 It has been reported that, in adult mice, several extramedullary tissues were identified as hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell–containing organs, including the liver,42 spleen,43 muscle,44 thoracic duct,45 and adipose tissue.46 Thereby, it is still not clear whether the plasma FIX in 2bF9 mice is the result of the nature of the promoter, expression in extramedullary hematopoietic progenitors, or the transgene construct we used.

Although platelet-derived FIX was clinically effective, platelet-derived FIX has limited efficacy in the presence of anti-FIX inhibitory antibodies. In splenocyte transplantation experiments, platelet FIX was still detectable in recipient mice even though they developed FIX inhibitory antibodies, demonstrating that within the insulating environment of platelet storage, FIX was protected from destruction because of inhibitory antibodies in circulation. Furthermore, they were not thrombocytopenic. In contrast to our observations in FVIII studies, 2bF9 mice with inhibitors were less probable to survive tail clipping, indicating that FIX was inhibited quickly once released by platelets. It is known that inhibitory antibodies against FIX are not time and temperature dependent,21,47 which is supported by our in vitro studies (data not shown) as well. Unlike FVIII, which binds to and is protected by the VWF carrier protein in plasma,48,49 no protein protects FIX in plasma, so antibodies can bind freely to FIX once they encounter each other in the plasma when FIX is released from activated platelets. This may be the reason why platelet FIX behaves differently from platelet FVIII in the face of inhibitory antibodies.

Although platelet-derived FIX does not maintain its clinical efficacy in the face of inhibitory antibodies, targeting FIX expression to platelets should still be an attractive potential strategy for gene therapy of hemophilia B. BMT from 2bF9 mice into lethally irradiated FIXnull recipients demonstrates that phenotypic correction is maintained with exclusively hematopoietic expression of 2bF9 with neither inhibitory nor noninhibitory antibody development. Chang et al have recently reported that targeting FIX expression to erythrocytes results in therapeutic levels of plasma FIX and immune tolerance.31 Therefore, the plasma FIX in 2bF9 genetic modified mice may be beneficial in immune tolerance induction. This will be further investigated by our group. Platelet infusion studies showed that the clinical efficacy can be maintained at least for 48 hours even when only a fraction (30%) of the circulating platelets contain FIX. This level should be achievable because our previous study has demonstrated that our lentivirus-mediated platelet-specific gene transfer system can efficiently introduce transgene expression in greater than 50% of megakaryocytes.50 Our FVIII studies have demonstrated that lentivirus-mediated BM transduction and syngeneic BMT can efficiently introduce transgene FVIII expression in the platelet lineage, resulting in therapeutic levels of platelet-FVIII in hemophilia A mice. A similar approach will be applied to 2bF9 gene transfer to explore the feasibility of platelet-derived FIX gene therapy of hemophilia B.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that storage of FIX in platelet α-granules can be achieved by ectopically expressing FIX in the platelet lineage. Activation of platelets releases FIX, which is effective in correcting the phenotype of hemophilia B even at a very low expression levels. Ectopically expressing FIX in platelets could be a new choice in the gene therapy for hemophilia B. An ex vivo 2bF9 genetic modification of hematopoietic stem cells followed by autologous-transplantation strategy could be effective for hemophilia B patients. Furthermore, our studies demonstrated that the function of platelet FIX is maintained at least for 48 hours after infusion. If ex vivo production of platelets were established as a transfusion alternative in the clinic, platelets with 2bF9 could be used therapeutically in patients with hemophilia B and the half-life of that FIX would be prolonged.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants HL-44612 and HL-33721, R.R.M.), CSL Behring Foundation Fellowship Award (G.Z), Bayer Hemophilia Awards Program (G.Z.), American Heart Association National Center Scientist Development Award (0730183N, Q.S.), National Hemophilia Foundation Career Development Award (Q.S.), and Hemophilia Association of New York Inhibitor Research Grant (Q.S.).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: G.Z. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; Q.S. helped in the design of the project, performed research, and wrote the manuscript; S.A.F. performed research and made comments on the manuscript; E.L.K. performed research; C.E.W. provided the hFIX cDNA construct; and R.R.M. helped in the design of the project, provided research support, and made critical comments on the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Robert R. Montgomery, Blood Research Institute, BloodCenter of Wisconsin, 8727 Watertown Plank Rd, Milwaukee, WI 53226; e-mail: bob.montgomery@bcw.edu.

References

- 1.Kay MA, Rothenberg S, Landen CN, et al. In vivo gene therapy of hemophilia B: sustained partial correction in factor IX-deficient dogs. Science. 1993;262(5130):117–119. doi: 10.1126/science.8211118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herzog RW, High KA. Adeno-associated virus-mediated gene transfer of factor IX for treatment of hemophilia B by gene therapy. Thromb Haemost. 1999;82(2):540–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chao H, Walsh CE. AAV vectors for hemophilia B gene therapy. Mt Sinai J Med. 2004;71(5):305–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niemeyer GP, Herzog RW, Mount J, et al. Long-term correction of inhibitor-prone hemophilia B dogs treated with liver-directed AAV2-mediated factor IX gene therapy. Blood. 2009;113(4):797–806. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-181479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.High KA. Update on progress and hurdles in novel genetic therapies for hemophilia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2007:466–472. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2007.1.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cramer EM, Norol F, Guichard J, et al. Ultrastructure of platelet formation by human megakaryocytes cultured with the Mpl ligand. Blood. 1997;89(7):2336–2346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukami MH, Salganicoff L. Human platelet storage organelles: a review. Thromb Haemost. 1977;38(4):963–970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veljkovic DK, Cramer EM, Alimardani G, Fichelson S, Masse JM, Hayward CP. Studies of alpha-granule proteins in cultured human megakaryocytes. Thromb Haemost. 2003;90(5):844–852. doi: 10.1160/TH03-02-0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jurk K, Kehrel BE. Platelets: physiology and biochemistry. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2005;31(4):381–392. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-916671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Italiano JE, Jr, Richardson JL, Patel-Hett S, et al. Angiogenesis is regulated by a novel mechanism: pro- and antiangiogenic proteins are organized into separate platelet alpha granules and differentially released. Blood. 2008;111(3):1227–1233. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-113837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blair P, Flaumenhaft R. Platelet alpha-granules: basic biology and clinical correlates. Blood Rev. 2009;23(4):177–189. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yarovoi HV, Kufrin D, Eslin DE, et al. Factor VIII ectopically expressed in platelets: efficacy in hemophilia A treatment. Blood. 2003;102(12):4006–4013. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi Q, Wilcox DA, Fahs SA, et al. Lentivirus-mediated platelet-derived factor VIII gene therapy in murine haemophilia A. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(2):352–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi Q, Wilcox DA, Fahs SA, Kroner PA, Montgomery RR. Expression of human factor VIII under control of the platelet-specific alphaIIb promoter in megakaryocytic cell line as well as storage together with VWF. Mol Genet Metab. 2003;79(1):25–33. doi: 10.1016/s1096-7192(03)00049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi Q, Wilcox DA, Fahs SA, et al. Factor VIII ectopically targeted to platelets is therapeutic in hemophilia A with high-titer inhibitory antibodies. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(7):1974–1982. doi: 10.1172/JCI28416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi Q, Fahs SA, Wilcox DA, et al. Syngeneic transplantation of hematopoietic stem cells that are genetically modified to express factor VIII in platelets restores hemostasis to hemophilia A mice with preexisting FVIII immunity. Blood. 2008;112(7):2713–2721. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-138214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yarovoi H, Nurden AT, Montgomery RR, Nurden P, Poncz M. Intracellular interaction of von Willebrand factor and factor VIII depends on cellular context: lessons from platelet-expressed factor VIII. Blood. 2005;105(12):4674–4676. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monahan PE, Samulski RJ, Tazelaar J, et al. Direct intramuscular injection with recombinant AAV vectors results in sustained expression in a dog model of hemophilia. Gene Ther. 1998;5(1):40–49. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lois C, Hong EJ, Pease S, Brown EJ, Baltimore D. Germline transmission and tissue-specific expression of transgenes delivered by lentiviral vectors. Science. 2002;295(5556):868–872. doi: 10.1126/science.1067081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lizee G, Aerts JL, Gonzales MI, Chinnasamy N, Morgan RA, Topalian SL. Real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction as a method for determining lentiviral vector titers and measuring transgene expression. Hum Gene Ther. 2003;14(6):497–507. doi: 10.1089/104303403764539387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gadarowski JJ, Jr, Czapek EE, Ontiveros JD, Pedraza JL. Modification of the Bethesda assay for factor VIII or IX inhibitors to improve efficiency. Acta Haematol. 1988;80(3):134–138. doi: 10.1159/000205619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodriguez MH, Enjolras N, Plantier JL, et al. Expression of coagulation factor IX in a haematopoietic cell line. Thromb Haemost. 2002;87(3):366–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nathwani AC, Davidoff AM, Hanawa H, et al. Sustained high-level expression of human factor IX (hFIX) after liver-targeted delivery of recombinant adeno-associated virus encoding the hFIX gene in rhesus macaques. Blood. 2002;100(5):1662–1669. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hasbrouck NC, High KA. AAV-mediated gene transfer for the treatment of hemophilia B: problems and prospects. Gene Ther. 2008;15(11):870–875. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang AH, Stephan MT, Lisowski L, Sadelain M. Erythroid-specific human factor IX delivery from in vivo selected hematopoietic stem cells following nonmyeloablative conditioning in hemophilia B mice. Mol Ther. 2008;16(10):1745–1752. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bigger BW, Siapati EK, Mistry A, et al. Permanent partial phenotypic correction and tolerance in a mouse model of hemophilia B by stem cell gene delivery of human factor IX. Gene Ther. 2006;13(2):117–126. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu L, O'Malley T, Sands MS, et al. In vivo transduction of hematopoietic stem cells after neonatal intravenous injection of an amphotropic retroviral vector in mice. Mol Ther. 2004;10(1):37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qiu X, Lu D, Zhou J, et al. Implantation of autologous skin fibroblast genetically modified to secrete clotting factor IX partially corrects the hemorrhagic tendencies in two hemophilia B patients. Chin Med J (Engl) 1996;109(11):832–839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manno CS, Chew AJ, Hutchison S, et al. AAV-mediated factor IX gene transfer to skeletal muscle in patients with severe hemophilia B. Blood. 2003;101(8):2963–2972. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manno CS, Pierce GF, Arruda VR, et al. Successful transduction of liver in hemophilia by AAV-Factor IX and limitations imposed by the host immune response. Nat Med. 2006;12(3):342–347. doi: 10.1038/nm1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang AH, Stephan MT, Sadelain M. Stem cell-derived erythroid cells mediate long-term systemic protein delivery. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24(8):1017–1021. doi: 10.1038/nbt1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohmori T, Ishiwata A, Kashiwakura Y, et al. Phenotypic correction of hemophilia A by ectopic expression of activated factor VII in platelets. Mol Ther. 2008;16(8):1359–1365. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kutti J, Weinfeld A. Platelet survival in man. Scand J Haematol. 1971;8(5):336–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1971.tb00883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lambert T, Recht M, Valentino LA, et al. Reformulated BeneFix: efficacy and safety in previously treated patients with moderately severe to severe haemophilia B. Haemophilia. 2007;13(3):233–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2007.01458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berridge MV, Ralph SJ, Tan AS. Cell-lineage antigens of the stem cell-megakaryocyte-platelet lineage are associated with the platelet IIb-IIIa glycoprotein complex. Blood. 1985;66(1):76–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phillips DR, Charo IF, Parise LV, Fitzgerald LA. The platelet membrane glycoprotein IIb-IIIa complex. Blood. 1988;71(4):831–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tropel P, Roullot V, Vernet M, et al. A 2.7- kb portion of the 5′ flanking region of the murine glycoprotein alphaIIb gene is transcriptionally active in primitive hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood. 1997;90(8):2995–3004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilcox DA, Olsen JC, Ishizawa L, Griffith M, White GC. Integrin alphaIIb promoter-targeted expression of gene products in megakaryocytes derived from retrovirus-transduced human hematopoietic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(17):9654–9659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fraser JK, Leahy MF, Berridge MV. Expression of antigens of the platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa complex on human hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 1986;68(3):762–769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tronik-Le RD, Roullot V, Poujol C, Kortulewski T, Nurden P, Marguerie G. Thrombasthenic mice generated by replacement of the integrin alpha(IIb) gene: demonstration that transcriptional activation of this megakaryocytic locus precedes lineage commitment. Blood. 2000;96(4):1399–1408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berlanga O, Emambokus N, Frampton J. GPIIb (CD41) integrin is expressed on mast cells and influences their adhesion properties. Exp Hematol. 2005;33(4):403–412. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cardier JE, Barbera-Guillem E. Extramedullary hematopoiesis in the adult mouse liver is associated with specific hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cells. Hepatology. 1997;26(1):165–175. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morrison SJ, Wright DE, Weissman IL. Cyclophosphamide/granulocyte colony-stimulating factor induces hematopoietic stem cells to proliferate prior to mobilization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(5):1908–1913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McKinney-Freeman SL, Jackson KA, Camargo FD, Ferrari G, Mavilio F, Goodell MA. Muscle-derived hematopoietic stem cells are hematopoietic in origin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(3):1341–1346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032438799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Massberg S, Schaerli P, Knezevic-Maramica I, et al. Immunosurveillance by hematopoietic progenitor cells trafficking through blood, lymph, and peripheral tissues. Cell. 2007;131(5):994–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Han J, Koh YJ, Moon HR, et al. Adipose tissue is an extramedullary reservoir for functional hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Blood. 2010;115(5):957–964. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-219923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Briet E, Reisner HM, Roberts HR. Inhibitors in Christmas disease. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1984;150:123–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaufman RJ, Wasley LC, Dorner AJ. Synthesis, processing, and secretion of recombinant human factor VIII expressed in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 1988;263(13):6352–6362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Denis C, Methia N, Frenette PS, et al. A mouse model of severe von Willebrand disease: defects in hemostasis and thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(16):9524–9529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shi Q, Wilcox DA, Morateck PA, Fahs SA, Kenny D, Montgomery RR. Targeting platelet GPIbalpha transgene expression to human megakaryocytes and forming a complete complex with endogenous GPIbbeta and GPIX. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2(11):1989–1997. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.