Abstract

Paliperidone palmitate is a new long-acting antipsychotic injection for the treatment of acute and maintenance therapy in schizophrenia. Paliperidone (9-hydroxyrisperidone) is the major active metabolite of risperidone and acts at dopamine D2 and serotonin 5HT2A receptors. As with other atypical antipsychotics, it exhibits a high 5HT2A:D2 affinity ratio. It also has binding activity as an antagonist at α1-and α2 adrenergic receptors and H1 histaminergic receptors, but has virtually no affinity for cholinergic receptors. Paliperidone palmitate has been shown to be effective in reducing Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total scores in four short-term trials in acute schizophrenia. It was also effective as maintenance therapy in a long-term trial in which time to recurrence of symptoms was significantly longer in paliperidone-treated patients compared with placebo. In addition, paliperidone was shown to be noninferior to risperidone long-acting injection in one study, but this noninferiority was not established in another longer study comparing the two drugs. Treatment should be initiated with 234 mg on day 1 and 156 mg on day 8, followed by a recommended monthly maintenance dose of 39–234 mg based on efficacy and tolerability. Paliperidone palmitate is generally well tolerated, although it can cause weight gain and a rise in prolactin levels, which is generally greater in women than in men. Overall, paliperidone palmitate may have advantages over other currently available long-acting injections, and therefore may be a useful alternative for the treatment of schizophrenia, although further long-term trials comparing it with active treatments are warranted.

Keywords: paliperidone palmitate, injection, schizophrenia, long-acting

Introduction

Poor compliance with medication remains a major cause for concern in the management of schizophrenia. It has been shown that more than 35% of patients experience compliance problems within the first few weeks of therapy, and only 25% are fully compliant after two years.1 A combination of factors may contribute to this problem, including lack of insight, negative symptoms, cognitive decline, and poor tolerability of available agents. These have a major negative impact on compliance which, in turn, leads to considerable risk of relapse, thus reducing the likelihood of full recovery to the baseline level of functioning.1

Conventional antipsychotic depot formulations were first introduced in the 1960s as a means to improve compliance with therapy. However, the negative symptoms of schizophrenia are not adequately managed by these older drugs, and their high propensity to cause extrapyramidal symptoms and raised prolactin levels has limited their use over time. Of late, after many years of research and development, pharmaceutical companies have also succeeded in formulating certain atypical antipsychotics into long-acting injections. Risperidone was the first atypical agent to be formulated as a long-acting injection, administered every two weeks. However, supplementary oral treatment is required for the first 4–6 weeks of intramuscular therapy due to the delay in reaching steady-state plasma levels. In addition, although the three licensed doses (25 mg, 37.5 mg, and 50 mg every two weeks) have been shown to be equally effective in clinical trials, the lowest dose (25 mg every two weeks) has been shown to be relatively less effective in practice.2

Olanzapine has also been recently formulated into a pamoate suspension for intramuscular administration every 2–4 weeks. With this product, a safety risk emerged during clinical trials known as “post-injection syndrome”, consisting of an unexpected high degree of sedation, confusion, dizziness, altered speech, and/or unconsciousness occurring in a small number of patients following injection.3 The incidence of this has been estimated as 1.2% of patients treated, or 0.07% of injections given.4 The formulation went on to gain its license despite this adverse effect, but with the recommendation that a three-hour patient observation period follow each injection, a restriction that will most likely limit its use for practical reasons, as well as the safety issues involved.4

While the introduction of atypical antipsychotic drugs has been of some benefit to patients, the use of these new agents has been accompanied by serious adverse effects also limiting their clinical use. Atypical antipsychotics have been implicated in the development of metabolic disorder,5 consisting of raised cholesterol and triglycerides alongside impaired glucose tolerance.6 The likelihood of experiencing these adverse effects varies amongst the different drugs in this class. Furthermore, considerable weight gain7 is an additional risk, often leading to early treatment discontinuation and poor compliance with therapy. As a result, despite the increasing number of agents being developed for the management of schizophrenia, there are still many individuals who are not receiving adequate benefit or not able to tolerate currently available agents. The introduction of paliperidone once-monthly injections is therefore a welcome addition to the market. In this paper, the pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and safety of paliperidone palmitate are reviewed, and its potential place in the treatment of schizophrenia is discussed.

Paliperidone palmitate

Paliperidone palmitate is the most recent atypical antipsychotic to be developed as a long-acting injection and was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in August 2009 for acute and maintenance therapy in adult patients with schizophrenia. A marketing authorization application has been submitted to the European Medicines Agency, whereby following approval, it will be marketed in Europe, and marketing applications in other areas of the world are ongoing.

Pharmacology

Paliperidone, also described as 9-hydroxyrisperidone, is the major active metabolite of risperidone. Its pharmacology and mechanism of action are therefore believed to be similar to that of risperidone. Paliperidone acts as an antagonist at dopamine D2 and serotonin 5HT2A receptors, exhibiting a high 5HT2A:D2 affinity ratio, as with other atypical agents.8 It also has binding activity as an antagonist at α1- and α2-adrenergic receptors and H1-histaminergic receptors, but has virtually no affinity for cholinergic receptors.8–10 Paliperidone’s activity profile suggests that it has the potential to cause orthostatic hypotension, weight gain, and sedation. However, because it has no antagonistic activity at cholinergic receptors, it has a low propensity to cause anticholinergic adverse effects and cognitive impairment.

Pharmacokinetics

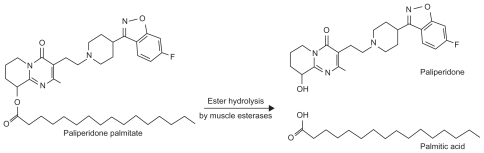

Paliperidone palmitate is a benzisoxazole derivative which is hydrolyzed to the active moiety, paliperidone, and absorbed into the systemic circulation (see Figure 1). The palmitate ester of paliperidone is an aqueous suspension which utilizes nanoparticle technology. The resulting increased surface area leads to rapid release of medication and therefore a relatively short time to steady state. Following an injection, active paliperidone plasma levels have been detected from day 1, therefore coadministration with oral paliperidone on initiation of therapy is not required. Following the intramuscular administration of single doses in the deltoid muscle, on average a 28% higher peak concentration is observed compared with injection in the gluteal muscle. However, after four injections, there is no difference between the time to maximum plasma concentration and area under the curve between the two injection sites.11,12 Thus, the two initial deltoid muscle injections on days 1 and 8 (see Table 1) help to attain therapeutic drug concentrations rapidly.13

Figure 1.

Formation of paliperidone from paliperidone palmitate.

Table 1.

Paliperidone palmitate injection dose and administration information13

| Initiation | Dose | Administration route |

|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | 234 mg | Deltoid muscle only |

| Day 8 (±2 days) | 156 mg | Deltoid muscle only |

| Maintenance | ||

| From Day 36 every four weeks (±7 days) | 39–234 mg | Either gluteal or deltoid muscle |

| Equivalent paliperidone dosages | ||

| Oral (mg/day) | Intramuscular (every four weeks) | |

| 2 | 39 mg (25 mg eq) | |

| 4 | 78 mg (50 mg eq) | |

| 6 | 117 mg (75 mg eq) | |

| 9 | 156 mg (100 mg eq) | |

| 12 | 234 mg (150 mg eq) | |

Notes: Although commercially available product dosage strengths of paliperidone palmitate are labeled in milligrams (mg) of paliperidone, all current published poster presentations and clinical trials have doses reported as milligram equivalents (mg eq) of paliperidone.

Abbreviation: mg eq, milligram equivalents.

Paliperidone is largely excreted unchanged in the urine. Four metabolic pathways have been identified for the metabolism of paliperidone including dealkylation, hydroxylation, dehydrogenation, and benzisoxazole scission, although none accounted for more than 10% of the oral dose administered.13 While cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 and CYP3A4 have been implicated in the metabolism of paliperidone in in vitro studies, these isoenzymes play a limited role in the metabolism of paliperidone in vivo. The nanocrystal molecules which make up the paliperidone palmitate suspension also allow it to undergo slow dissolution, yielding a half-life of 25–49 days (see Table 2).13–16 The relatively long half-life allows for the monthly administration of paliperidone intramuscular injections.

Table 2.

| Median time to maximum plasma concentration | 13 days |

| Plasma protein binding (racemic paliperidone) | 74% |

| Mean apparent volume of distribution | 391 L |

| Median apparent half-life (after single-dose administration) | 25–49 days |

| Metabolism | Minimal metabolism occurs in the liver (dose adjustment needed only in severe hepatic impairment) |

| Excretion | Up to 60% excreted unchanged by kidneys (lower doses needed in renal impairment) |

Efficacy in schizophrenia

Efficacy in clinical trials

The therapeutic efficacy of paliperidone palmitate once-monthly injection has been evaluated in four short-term (nine- and 13-week) multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials in acute schizophrenia.14,17–19 In all four trials, the injection was administered on days 1, 8, and 36 and, in the 13-week trials, also on day 64. Paliperidone palmitate’s efficacy as maintenance therapy in schizophrenia has also been evaluated in a 52-week recurrence prevention study20 and a further 52-week, open-label extension phase of this study.21 In addition, two studies compared its clinical efficacy with intramuscular long-acting risperidone injection.22,23 Many of these studies are currently only available as poster presentations. The main efficacy findings from the trials are summarized below (and also in Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of efficacy studies for paliperidone palmitate

| Authors | Study details | Number of patients (n) | Length | Paliperidone palmitate dose and route |

Outcome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doses† (mg eq) | (mg) | route | |||||||

| Kramer et al14 | RCT, DB, PC Efficacy and safety study |

247 (197 ITT analysis) | 9 weeks | Gluteal | Mean PANSS total (SD) | ||||

| Baseline | Change from baseline | ||||||||

| 50 | 78 | 88.0 (12.39) | −5.2 (21.5) (P = 0.001)* | ||||||

| 100 | 156 | 85.2 (11.09) | −7.8 (19.4) (P < 0.001)* | ||||||

| Placebo | 87.8 (13.90) | 6.2 (18.3) | |||||||

| Gopal et al17 | RCT, DB, PC Dose-response study |

388 | 13 weeks | Gluteal | Mean PANSS total (SD) | ||||

| Baseline | Change from baseline | ||||||||

| 50 | 78 | 90 (10.8) | −3.5 (2.67) (P = 0.19) | ||||||

| 100 | 156 | 90 (11.7) | −6.9 (2.65) (P = 0.019)* | ||||||

| 150 | 234 | 92 (11.7) | −5.5 (3.61) | ||||||

| Placebo | 92 (12.6) | −4.1 (1.83) | |||||||

| Pandina et al18 | RCT, DB, PC Dose-response study |

652 | 13 weeks | Deltoid/gluteal | Mean PANSS total (SD) | Estimated effect sizes versus pbo | |||

| Baseline | Change from baseline | ||||||||

| 25 | 39 | 86.9 (11.99) | −8.1* | (0.28) | |||||

| 100 | 156 | 86.2 (10.77) | −11.6* | (0.49) | |||||

| 150 | 234 | 88.4 (11.70) | −13.2* | (0.55) | |||||

| Placebo | 86.8 (10.31) | −2.9 (*P ≤ 0.034) | |||||||

| Hough et al20 | RCT, DB, PC, study to evaluate efficacy in prevention of recurrence of symptoms | 312 included in the interim analysis 408 included in final analysis |

52 weeks | 25 | 39 | Gluteal | Time to relapse in PP patients versus placebo (P < 0.0001, Chi-square = 29.41) Relapse event rates: PP: 10% versus pbo: 34% Hazard ratio at final analysis (pbo/PP) was 3.60 (95% CI 2.45, 5.28) |

||

| 5 phases | 50 | 78 | |||||||

| 100 | 156 | ||||||||

| Gopal et al21 | Long-term, open-label, extension-phase study (see Hough et al20) | 388 | 52-week extension (median treatment duration 338 days) | Mode doses | OLE Baseline PANSS total score (SD) for total PP group: 58.1 (18.33) Mean (SD) of change from OLE baseline to endpoint in PANSS total score: −4.3 (15.43) Greatest improvement in PANSS total score was observed in PP pts who had been on pbo in DB phase: −8.4 (19.43) |

||||

| 100: 56% | 156 | ||||||||

| 50: 34% | 78 | ||||||||

| 75: 9% | 117 | ||||||||

| 25: 1% | 39 | ||||||||

| Poster presentations | |||||||||

| Nasrallah et al19,27 | RCT, DB, PC, parallelgroup, dose-response study | 518 (514 ITT population) | 13 weeks | Gluteal | Mean PANSS total (SD) | ||||

| Baseline | Change from baseline | ||||||||

| 25 | 39 | 90.7 (12.2) | −13.6 (21.45) (P = 0.02)* | ||||||

| 50 | 78 | 91.2 (12.0) | −13.2 (20.14) (P = 0.02)* | ||||||

| 100 | 156 | 90.8 (11.7) | −16.1 (20.36) (P < 0.001)* | ||||||

| Placebo | 90.7 (12.2) | −7.0 (20.07) | |||||||

| Comparison with RLAI | |||||||||

| Fleischhacker et al22 | RCT, parallel-group, noninferiority study of PP compared with RLAI | 749 | 53 weeks | PP: 39, 78, 117 or 156 mg/four weeks (+ oral pbo and IM pbo/two weeks) RLAI: 25, 37.5 or 50 mg/two weeks (+ oral risperidone) |

Mean (SD) change from baseline to endpoint (LOCF) in PANSS total (60–120 at baseline): PP: −12 (21.2) RLAI: −14 (19.8) Least-squares means change in PANSS total score was 2.6 points lower (95% CI 5.84, 0.61) for RLAI than PP group. Predetermined margin for noninferiority was not met (by 0.84 points). |

||||

| Pandina et al23 | RCT, DB, parallel-group, multicenter comparative study with RLAI | 1220 total 913 (ITT analysis) |

13 weeks | PP: 78, 156 or 234 mg/four weeks (+ oral pbo and IM pbo/two weeks) RLAI: 25, 37.5 or 50 mg/two weeks (+ oral risperidone) |

Baseline PANSS total score, mean (SD): PP: 84.1 (12.09); RLAI: 83.6 (11.28) Lower limit of 95% CI of treatment difference for change in PANSS total score exceeded protocol prespecified noninferiority margin (−5) PP demonstrated to be noninferior to RLAI (point estimate [95% CI]: 0.4 [−1.62; 2.38]) |

||||

Notes: Statistically significant;

Commercially available product dosage strengths of paliperidone palmitate are labeled in milligrams (mg) whereas current published poster presentations and clinical trials use doses reported as milligram equivalents (mg eq) to paliperidone.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; DB, double-blind; ITT, intention to treat; LOCF, last observation carried forward; OLE, open label extension; Pp, paliperidone palmitate; pbo, placebo; PC, placebo-controlled; PANSS, positive and negative symptom scale; pts, patients; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RLAI, risperidone long-acting injection; SD, standard deviation.

Acute efficacy

The primary efficacy endpoint in all studies was the mean change in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score24 from baseline to endpoint. Secondary endpoints included changes in Clinical Global Impression of Severity (CGI-S),25 PANSS factor and subscale scores, and Personal and Social Performance Scale (PSP).26

In the largest dose-response study, intramuscular paliperidone was effective in the treatment of adult patients with acute schizophrenia, producing significant (P ≤ 0.034) and dose-related changes in PANSS total score from baseline for each of the three paliperidone groups (39, 156, and 234 mg) compared with placebo.18 A significant change in PANSS total score was observed as early as day 8 for paliperidone 39 and 234 mg and from day 22 for paliperidone 156 mg, and was maintained until the endpoint. Significantly more patients on paliperidone responded to treatment (39 mg 33.5%, P = 0.007; 156 mg 41.0%, P < 0.001; 234 mg 40.0%, P < 0.001) compared with placebo (20.0%).18

These findings are supported by two smaller, published, dose-response studies.14,17 In the first study, both doses of paliperidone (78 mg and 156 mg) produced significant (P ≤ 0.001) mean changes from baseline in PANSS total score (−5.2 [21.5)] and −7.8 [19.4], respectively) compared with placebo (6.2 [18.3]).14 In the second study, significant changes in PANSS total score compared with placebo were noted with the 156 mg dose (P = 0.019) but not with the 78 mg dose (P = 0.19).17 No statistical comparison was performed for the 234 mg treatment group, therefore a dose-response relationship could not be ascertained from this study.

Long-term efficacy

There has also been a long-term maintenance study of recurrence prevention using paliperidone palmitate, which consisted of five phases, including a seven-day screening, washout, and tolerability period, a nine-week, open-label transition phase during which intramuscular paliperidone was initiated, a 24-week, open-label, maintenance phase with flexible dosing until week 21, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase of variable duration,20 and an optional 52-week, open-label extension phase.21 A recurrence event was defined as time to the first emergence of one or more of the following: hospitalization (for symptoms of schizophrenia), prespecified changes in PANSS scores or clinically significant deliberate self-injury or aggressive behavior. The primary outcome measure was time from randomization to the first recurrent event. A preplanned interim analysis was carried out in order to minimize the number of patients exposed to placebo. In the interim analysis (planned after 68 relapse events) paliperidone palmitate was superior to placebo, with recurrence of events seen in 15 (10%) patients in the paliperidone group compared with 53 (34%) patients in the placebo group,20 yielding a numbers needed to treat of five (95% confidence interval [CI] 4–7).27

In the open-label extension phase of this study, improvements from baseline to the endpoint were observed on PANSS, PSP, and CGI-S assessment.21 Overall improvements in PANSS total scores observed during the previous study phases were maintained during the open-label phase for patients treated with paliperidone (mean ± SD of the change in PANSS total score −4.3 ± 15.43). The greatest improvement in PANSS total score occurred in patients who were treated with placebo in the double-blind phase (−8.4 ± 19.43). Functional improvement as measured by the PSP scale, also continued during the open-label phase, with the greatest improvement observed in patients previously on placebo in the double-blind phase (change in PSP score 6.0 ± 13.20). The authors reported that the majority of patients stayed in this open-label phase for one year, and demonstrated maintenance of symptoms as well as functional improvements.

Efficacy compared with active comparator

Paliperidone palmitate injection was compared with risperidone long-acting injection (RLAI) in a 53-week noninferiority study.22 Patients were randomized (1:1) to receive double-blind flexible doses of paliperidone 39–156 mg every four weeks by gluteal injection (after two initiation doses of 78 mg on days 1 and 8) or RLAI 25, 37.5, or 50 mg every two weeks. Oral supplementation with risperidone was provided to the RLAI patients (as well as a placebo injection on day 1), and matched paliperidone patients received oral placebo and two-weekly placebo injections to coincide with RLAI frequency.

Although both agents resulted in decreases in PANSS total score (−12 ± 21.2 for paliperidone and −14 ± 19.8 for RLAI), paliperidone was not shown to be noninferior to RLAI, based on the predetermined margin of 5 points. Least-squares means change in PANSS total score was 2.6 points lower (95% CI −5.84, 0.61) for RLAI compared with paliperidone. As such, the predetermined margin for noninferiority (lower limit of the 95% CI should be greater than −5 points) was not met (by 0.84 points). However, the authors concluded that noninferiority was not established because patients had been initiated with suboptimal initial dosing of paliperidone, substantially lower than the initiation doses currently recommended in the product labeling. Therefore, this may have resulted in lower plasma concentrations until day 260 compared with those in the RLAI group. In addition, the authors believed that utilization of the gluteal initiation site may have also led to lower plasma levels of paliperidone, because this site of administration is associated with lower initial exposure.

Consequently, another noninferiority study between paliperidone palmitate and RLAI was performed, acknowledging the optimized initiation dosing regimen for paliperidone.23 This was a randomized (1:1), double-blind, double-dummy, active- controlled, parallel-group, 13-week comparative Phase III study. Paliperidone deltoid injections of 234 mg on day 1 and 156 mg on day 8 were given, followed by once-monthly flexible dosing (78–234 mg) as either deltoid or gluteal injections (and placebo injections matched to RLAI). The other group received RLAI starting at 25 mg on day 8, followed by biweekly injections which could be increased up to 37.5 mg on day 36 and up to 50 mg on day 64 (and placebo injections matched to the paliperidone initiation regimen). Patients on RLAI received oral risperidone supplementation (1–6 mg from days 1–28), while the paliperidone group received a matching oral placebo.

The primary endpoint was the change in PANSS total score from baseline to the double-blind endpoint. Noninferiority of paliperidone compared with RLAI was to be concluded if the lower limit of the two-sided 95% CI exceeded −5. Additional secondary endpoints included PANSS subscales, CGI-S, and PSP. Unlike the previous study, the lower limit of the 95% CI of the treatment difference for the change in PANSS total score did exceed the prespecified protocol noninferiority margin of −5, and therefore paliperidone was shown to be noninferior to RLAI (point estimate [95% CI] 0.4 [−1.62; 2.38]). In addition, both groups showed similar improvements in CGI-S and PSP, as well as other secondary measures.23 Limitations of this study include its relatively short duration, lasting only 13 weeks compared with 53 weeks in the previous one, and therefore the longer-term efficacy of paliperidone palmitate cannot be compared with RLAI from these findings. Furthermore, doses above 25 mg were not allowed in the RLAI group for several weeks, despite evidence to show that RLAI 25 mg may be ineffective in the majority of patients.2 In fact, many patients in clinical practice nowadays are being initiated on 37.5 mg of RLAI, and the higher doses are generally used a lot sooner in the therapeutic regimen.

Safety and tolerability

The safety and tolerability of paliperidone palmitate were also assessed in the studies already described. The main findings are summarized in this section (and in Table 4). Treatment emergent adverse effects (TEAEs) occurring more frequently in the paliperidone palmitate groups than in the placebo group included insomnia, headache, dizziness, sedation, vomiting, schizophrenia, injection site pain, extremity pain, myalgia, and extrapyramidal symptoms.14,17

Table 4.

Summary of safety studies for paliperidone palmitate

| Authors | Study details | Number of patients (n) | Safety outcomes for paliperidone palmitate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kramer et al14 | RCT, DB, PC Nine-week, efficacy and safety study |

247 | Incidence of TEAEs:

Predose:

Predose:

|

| Hough et al28 | Randomized, 25-week, crossover study comparing deltoid and gluteal administration of PP 78, 117, and 156 mg | 252 (ITT: 249) | Overall incidence of TEAEs:

|

| Gopal et al17 | RCT, DB, PC 13 weeks Dose-response study |

388 | Incidence of TEAEs:

|

| Pandina et al18 | RCT, DB, PC 13 weeks Dose-response study |

652 | Similar TEAE rates:

PP groups

|

| Hough et al20 | RCT, DB, PC 52-week study to evaluate efficacy in prevention of recurrence of symptoms |

408 | Abnormal weight increase (≥7%):

Blood glucose increase (≥2% difference):

|

| Gopal et al21 | Open-label, extension-phase (see Hough et al20) | 388 | Weight change for total PP group: 0.9 ± 4.26 kg 13% of patients experienced ≥7% weight increase at endpoint. Prolactin levels increased in patients on PP who were on pbo in previous phase (pbo/PP) compared with those on PP in previous phase (PP/PP):

|

| Poster presentations | |||

| Nasrallah et al19 | RCT, DB, PC 13-week, parallel-group, dose-response study |

514 | Discontinuation due to TEAEs:

|

| Coppola et al29 | One-year, open-label study evaluating long-term safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of PP 234 mg monthly | 212 | A total of 184 pts (87%) experienced ≥1 TEAE. 27 pts (13%) discontinued due to TEAEs. 11 pts (5%) discontinued due to serious TEAEs. No deaths were reported during the study. The most frequent TEAEs (in ≥5% patients) were:

Overall body weight increases of ≥7% in 65 patients (31%). Mean body weight increased by 3.9% from baseline to endpoint. Prolactin-related adverse effects in 41 patients (19%). Incidences were higher in women (32.8%) than men (14.3%) |

| Comparison with RLAI | |||

| Fleischhacker et al22 | RCT, 53-week, parallel-group, noninferiority study of PP compared with RLAI | 747 (included in safety analysis) | Rates of TEAEs:

|

| Pandina et al23 | RCT, DB, parallel-group, noninferiority study with RLAI 13 weeks | 1214 (safety analysis set) | Rate of TEAEs:

Incidence of glucose-related TEAEs (<1% patients), EPS, mean [SD] increases in body weight at endpoint (PP: 1.1 [3.36] kg, RLAI: 1.0 [3.14] kg) and injection site tolerability were similar in both groups. |

Abbreviations: DB, double-blind; ECG, electrocardiogram; EPS, extrapyramidal symptoms; ITT, intention to treat; PP, paliperidone palmitate; pbo, placebo; PC, placebocontrolled; RC, randomized controlled trial; SD, standard deviation; TEAE, treatment emergent adverse effect.

Safety in acute therapy

In the nine-week study, parkinsonian-type adverse effects, including drooling and hypertonia, were the most common extrapyramidal side effects, and occurred more frequently in the paliperidone groups than placebo.14 Other extrapyramidal side effects occurred similarly in all groups and were not considered severe in intensity. Median prolactin levels remained elevated for the paliperidone treatment groups compared with median predose treatment values, whereas prolactin levels decreased to pretreatment values in the placebo patients (see Table 4). The percentage of patients with a > 7% increase in weight was reported to be 6–8% of patients in the paliperidone groups versus 4% for placebo-treated patients. Although the authors considered this weight increase to be low, it was still up to twice that seen in the placebo patients, therefore may be of clinical significance and a potential cause of metabolic complications. In addition, significant mean increases in body weight and body mass index from baseline to endpoint were observed for the 156 mg dose (P ≤ 0.001 for both measures) and increases for the 78 mg dose compared with placebo were P = 0.036 for body mass index and P = 0.059 for weight (see Table 4). The incidence of increased heart rate was higher for paliperidone-treated patients (17%) than for placebo (8%), as was the incidence of orthostatic hypotension (9% versus 4%, respectively), although none of the latter were reported as adverse effects or symptomatic, and the incidence of tachycardia was low (<2%). In addition, although the study was not powered to assess safety, cardiac tolerability appeared to be good, with no patients on paliperidone experiencing QTc prolongation or a QTc > 450 msec during the study.14

In the small 13-week trial, the frequency of glucose-related adverse effects was the same (2%) in the placebo and paliperidone groups.17 As in the previous study, clinically relevant weight increases (>7% from baseline to endpoint) were more common among patients in the paliperidone groups (78 mg 12%, 156 mg 10%, 234 mg 4%) compared with placebo (2%), although the percentage of people with clinically relevant weight increases did not rise with increasing dose. In addition, mean increases in weight from baseline to endpoint were modest, and ranged from 0.9 to 1.5 kg but did not appear to be dose-related (see Table 4). However, mean increases in prolactin levels from baseline to endpoint were seen in all paliperidone groups, and increases were larger for the 156 mg and 234 mg groups than for the 78 mg group in both women and men, suggesting a dose-related relationship. There were no clinically relevant changes in vital signs, electrocardiogram (ECG) recordings, or other clinical laboratory parameters, and local injection site tolerability was reported to be good.

In the largest dose-response study, the incidence of TEAEs leading to study discontinuation was similar across treatment groups (placebo 6.7%, paliperidone 6.1%–8%).18 However, the incidence of serious TEAEs was higher in the placebo group (14%) than in the paliperidone groups (39 mg 9.4%, 156 mg 13.3%, 234 mg 8%). The most commonly reported serious TEAEs for paliperidone were worsening or exacerbation of schizophrenia (4.9%) and psychotic disorder (2.9%), although these figures were lower than those reported for placebo (6.1% and 4.3%, respectively). Unlike the previous study, a weight increase of 7% or higher was found to occur more frequently with the higher doses of paliperidone (see Table 4). There were no clinically relevant changes from baseline in vital signs, ECG recordings, or other laboratory parameters (including fasting glucose levels and serum lipids) in the paliperidone groups. In addition, injection site tolerability was said to be good, with investigators rating injection site pain similar to that with placebo.

Safety in long-term therapy

Findings from the long-term relapse prevention study showed that weight increase occurred more frequently in patients treated with paliperidone palmitate (7%) than placebo (1%), as did the blood glucose increase in the paliperidone group (3%) versus placebo (1%).20 Mean weight, from transition baseline to the double-blind endpoint, increased by 1.9 kg for paliperidone-treated patients, but remained unchanged for placebo patients. Abnormal weight increases (≥7%) also occurred in twice as many paliperidone patients as placebo patients from both transition and double-blind baselines (see Table 4). There were no clinically relevant changes from transition baseline to the double-blind end-point in extrapyramidal symptom rating scales and no reports of orthostatic hypotension or ECG changes during the double-blind phase (although ECG changes were seen in the transition and maintenance open-label paliperidone phases). In accordance with other studies, prolactin levels increased for the paliperidone group, again more in women than in men, while levels decreased in the placebo group (see Table 4). No other laboratory parameter changes were noted, and injection site tolerability was similar in all groups.20

Other safety data

The safety and tolerability of initiating treatment with paliperidone palmitate via either deltoid or gluteal injections were investigated in a study comparing the two administration routes.28 This crossover trial included 252 stable outpatients randomly assigned 1:1:1 to three dose groups of paliperidone (see Table 4) and two treatment sequences including deltoid muscle injection (13 weeks), followed by gluteal muscle injection (12 weeks), or the reverse. The proportion of patients with injection-site pain appeared to be higher after deltoid administration compared with gluteal administration (41% deltoid, 26% gluteus), based on the 90% CI of investigator evaluations of the presence of local symptoms at the injection site. The overall incidence of TEAEs did not differ significantly between deltoid injections (period 1 = 64%, period 2 = 51%) and gluteal injections (period 1 = 63%, period 2 = 46%), and there was no dose-dependent increase in the incidence of TEAEs. Evaluation of pain by patients revealed slightly more intense pain following deltoid injections compared with gluteal injections for the 78 mg and 117 mg doses of paliperidone, but no difference was detected for the 156 mg dose. There were no clinically significant changes in extrapyramidal symptom rating scales regardless of the injection site or the dose.28

Safety compared with active comparator

In the two noninferiority studies of paliperidone palmitate and RLAI, the overall rates of TEAEs were found to be similar between the two groups. In the first study, rates of TEAEs were 76% in the paliperidone group and 79% in the RLAI group,22 whereas in the second study, rates of TEAEs were 57.9% in the paliperidone group and 52.8% in the RLAI group.23 Therefore, neither drug can be associated with a higher incidence of adverse effects based on these results. In both studies, the incidence of extrapyramidal symptoms was similar in both groups, with the exception of hyperkinesias which was less common in the paliperidone group than in the RLAI group in the first study (6% versus 10%, respectively).22 With regard to weight changes, weight actually decreased in the paliperidone palmitate group in the first study compared with RLAI (which caused a slight weight increase), whereas in the second study, mean body weight increases were similar at the endpoint between the two treatment groups (see Table 4). In addition, in the second study, there were no clinically relevant changes in vital signs or ECG, and the incidence of glucose-related TEAEs, as well as investigator assessments of the injection site, were similar in both treatment groups.23 Overall, it appears that both paliperidone palmitate and RLAI have comparable adverse effect profiles. However, the second study only lasted 13 weeks, and so long-term comparisons cannot be made. In addition, both studies are currently only available in poster format, thus not allowing for a thorough evaluation of the data.

Summary of safety data

In summary, paliperidone is relatively well tolerated but, like many other antipsychotics, and as expected from its pharmacological profile, it can cause weight gain and an increase in prolactin levels. Whether weight gain is dose-related or not is still debatable based on the current evidence. However, the rise in prolactin has been shown to be greater with higher doses. In all studies, there were no clinically relevant changes in vital signs, ECG recordings, or other clinical laboratory parameters, and local injection site tolerability was reported to be good. The majority of currently available trials are short-term, therefore additional longer trials are required in order to assess paliperidone palmitate’s long-term safety profile, in particular with regard to changes in metabolic parameters because these may not be picked up in short-term studies. Paliperidone injection and RLAI were found to have comparable adverse effect profiles. Table 5 compares the adverse effects of paliperidone with other antipsychotic agents.

Table 5.

Adverse effects of paliperidone compared to other antipsychotics

| Drug | QTc prolongation | Hypotension | Sedation | Weight gain | Metabolic syndrome | Extrapyramidal symptoms | Anticholinergic | Prolactin elevation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amisulpride | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | +++ |

| Aripiprazole | − | − | − | +/− | +/− | +/− | − | − |

| Asenapine | + | − | + | − | − | + | − | +/− |

| Chlorpromazine | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ |

| Clozapine | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | − | +++ | − |

| Haloperidol | +++ | + | + | + | + | +++ | + | +++ |

| Olanzapine | + | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | +/− | + | + |

| Paliperidone | −/+ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | + | + | +++ |

| Quetiapine | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | − | + | − |

| Risperidone | + | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | + | + | +++ |

| Sulpiride | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | +++ |

Abbreviations: +++, high incidence/severity; ++, moderate incidence/severity; +, low incidence/severity; −, very low incidence/severity. Adapted from The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines 10th Edition.30

Discussion

Paliperidone palmitate has been shown to be effective in reducing PANSS total scores in both acute and maintenance treatment of schizophrenia. Improvements in PANSS total scores observed in the majority of studies were greater with higher doses of paliperidone, suggesting a dose-response relationship. Paliperidone injection is generally well tolerated but can cause weight gain and dose-related raised prolactin levels. In two noninferiority studies comparing paliperidone with RLAI, paliperidone injection only proved to be noninferior to RLAI in one study. Paliperidone and RLAI were shown to have comparable adverse effects. Additional long-term trials comparing paliperidone palmitate’s efficacy and safety with active comparators are required. The fact that some of the current data for paliperidone injection are only available as poster presentations is an important limitation for its evaluation.

Conclusion

Given the importance of treatment adherence in schizophrenia, and taking into consideration the compliance problems that often accompany the illness, long-acting antipsychotic injections are a valuable form of therapy. Paliperidone palmitate once-monthly injections may be a useful alternative in a currently limited market. The recommended dosage regimen is 234 mg on day 1 followed by 156 mg a week later, both administered in the deltoid muscle. The recommended maintenance dose is 117 mg monthly, which may be adjusted, based on efficacy and tolerability, within a 39–234 mg range, administered in either the deltoid or gluteal muscle. Paliperidone palmitate has some advantages over available agents, including a faster onset of action than RLAI and the absence of a requirement for oral supplementation at the start of therapy. Therefore, it may be a suitable option in patients who refuse oral treatment. In addition, it is available in a wider variety of strengths than RLAI, allowing for a more specialized and patient-specific dose titration regimen. Since paliperidone can be given either in the deltoid or gluteal muscle after initiation has been established, this improves flexibility of administration. It also has the added advantage of not requiring refrigeration for safe storage. Furthermore, unlike with olanzapine pamoate, “post-injection syndrome” was not reported during the clinical trials with paliperidone, which makes it a suitable agent when a postinjection observation period is not practical.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The author reports no conflict of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Nasrallah HA. The case for long-acting antipsychotic agents in the post-CATIE era. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;115(4):260–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor DM, Young C, Patel MX. Prospective 6-month follow-up of patients prescribed risperidone long-acting injection: Factors predicting favourable outcome. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;9(6):685–694. doi: 10.1017/S1461145705006309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eli Lilly and Company Limited. Summary of Product Characteristics. Zypadhera 210 mg, 300 mg, and 405 mg, powder and solvent for prolonged release suspension for injection. 2009. [Accessed on Jul 14, 2010]. Available at: http://emc.medicines.org.uk/

- 4.Bishara D, Taylor D. Upcoming agents for the treatment of schizophrenia. Mechanism of action, efficacy and tolerability. Drugs. 2008;68(16):2269–2296. doi: 10.2165/0003495-200868160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nasrallah HA. Atypical antipsychotic-induced metabolic side effects: Insights from receptor-binding profiles. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13(1):27–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haddad PM. Antipsychotics and diabetes: Review of non-prospective data. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2004;47:S80–S86. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.47.s80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor DM, McAskill R. Atypical antipsychotics and weight gain – a systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101(6):416–432. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.101006416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leysen JE, Janssen PM, Megens AA, Schotte A. Risperidone: A novel antipsychotic with balanced serotonin-dopamine antagonism, receptor occupancy profile, and pharmacologic activity. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55(Suppl):5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schotte A, Janssen PF, Gommeren W, et al. Risperidone compared with new and reference antipsychotic drugs: In vitro and in vivo receptor binding. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;124:1–2. 57–73. doi: 10.1007/BF02245606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Beijsterveldt LE, Geerts RJ, Leysen JE, et al. Regional brain distribution of risperidone and its active metabolite 9-hydroxyrisperidone in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1994;114(1):53–62. doi: 10.1007/BF02245444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cleton A, Rossenu S, Crauwels H, et al. Assessment of the dose proportionality of paliperidone palmitate 25, 50, 100 and 150 mg EG. A new long-acting injectable antipsychotic, following administration in the deltoid or gluteal muscles. Poster presented at American Society for Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics; Orlando, FL. 2008 Apr 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cleton A, Rossenu S, Hough D, et al. Evaluation of the pharmacokinetic profile of deltoid versus gluteal intramuscular injections of paliperidone palmitate in patients with schizophrenia. Poster presented at the American Society for Pharmacology and Therapeutics; Orlando, FL. 2008 Apr 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janssen. Once-monthly Invega Sustenna: Paliperidone palmitate extended-release injectable suspension. 2009. [Accessed on Jul 14, 2010]. Available at: http://www.invegasustenna.com/invegasustenna/assets/hcp/01PM09110.pdf.

- 14.Kramer M, Litman R, Hough D, et al. Paliperidone palmitate, a potential long-acting treatment for patients with schizophrenia. Results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled efficacy and safety study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;13(5):635–647. doi: 10.1017/S1461145709990988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samtani MN, Vermeulen A, Stuyckens K. Population pharmacokinetics of intramuscular paliperidone palmitate in patients with schizophrenia: A novel once-monthly, long-acting formulation of an atypical antipsychotic. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2009;48(9):585–600. doi: 10.2165/11316870-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sedky K, Nazir R, Lindenmayer JP, Lippman S. Paliperidone palmitate: Once monthly treatment option for schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry Online. 2010;9(3):48–50. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gopal S, Hough DW, Xu H, et al. Efficacy and safety of paliperidone palmitate in adult patients with acutely symptomatic schizophrenia: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010 Apr 10; doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e32833948fa. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pandina GJ, Lindenmayer JP, Lull J, et al. A randomized, placebocontrolled study to assess the efficacy and safety of 3 doses of paliperidone palmitate in adults with acutely exacerbated schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(3):235–244. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181dd3103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nasrallah HA, Gopal S, Gassmann-Mayer C, et al. Efficacy and safety of three doses of paliperidone palmitate, an investigational longacting injectable antipsychotic in schizophrenia. Poster presented at the Institute on Psychiatric Services Annual Meeting; Chicago, IL. 2008 Oct 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hough D, Gopal S, Vijapurkar U, Lim P, Morozova M, Eerdekens M. Paliperidone palmitate maintenance treatment in delaying the time-to-relapse in patients with schizophrenia: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res. 2010;116:2–3. 107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gopal S, Vijapurkar U, Lim P, Morozova M, Eerdekens, Hough D. A 52-week open-label study of the safety and tolerability of paliperidone palmitate in patients with schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacol. 2010 Jul 8; doi: 10.1177/0269881110372817. Online-First. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleischhacker WW, Gopal S, Samtani M, et al. Optimization of the dosing strategy for the long-acting injectable antipsychotic paliperidone palmitate: Results of two randomized double-blind studies and population pharmacokinetic simulations. Poster presented at the American Society for Pharmacology and Therapeutics; Scottsdale, AZ. 2008 Dec 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pandina G, Lane R, Gopal S, et al. A randomized, double-blind, comparative study of flexible doses of paliperidone palmitate and risperidone long-acting therapy in patients with schizophrenia. Poster presented at the 48th American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; Hollywood, FL. 2009 Dec 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haro JM, Kamath SA, Ochoa S, et al. The Clinical Global Impression-Schizophrenia scale: A simple instrument to measure the diversity of symptoms present in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2003;(416):16–23. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.107.s416.5.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patrick DL, Adriaenseen I, Morosini PL, Gagnon D, Rothman M. Reliability, validity and sensitivity to change of the Personal and Social Performance scale in patients with acute schizophrenia. Poster presented at Collegium Internationale Neuropsychopharmacologicum; Chicago, IL. 2006 Jul 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Citrome L. Paliperidone palmitate – review of the efficacy, safety and cost of a new second-generation depot antipsychotic medication. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64(2):216–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hough D, Lindenmayer JP, Gopal S, et al. Safety and tolerability of deltoid and gluteal injections of paliperidone palmitate in schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33(6):1022–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coppola D, Liu Y, Gopal S, et al. Long-term safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of paliperidone palmitate 234mg (150 mg eq.), the highest marketed dose: A one-year open-label study in patients with schizophrenia. Poster presented at the American Society for Pharmacology and Therapeutics; Atlanta, GA. 2010 Mar 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor D, Paton C, Kapur S. The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines. 10th Edition. London: Informa Healthcare; 2009. [Google Scholar]