The authors report results from a systematic molecular analysis comparing the liver transduction efficiency of single-stranded and self-complementary AAV vectors in mice and nonhuman primates at early and late stages of gene transfer.

Abstract

Vectors based on several new adeno-associated viral (AAV) serotypes demonstrated strong hepatocyte tropism and transduction efficiency in both small- and large-animal models for liver-directed gene transfer. Efficiency of liver transduction by AAV vectors can be further improved in both murine and nonhuman primate (NHP) animals when the vector genomes are packaged in a self-complementary (sc) format. In an attempt to understand potential molecular mechanism(s) responsible for enhanced transduction efficiency of the sc vector in liver, we performed extensive molecular studies of genome structures of conventional single-stranded (ss) and sc AAV vectors from liver after AAV gene transfer in both mice and NHPs. These included treatment with exonucleases with specific substrate preferences, single-cutter restriction enzyme digestion and polarity-specific hybridization-based vector genome mapping, and bacteriophage ϕ29 DNA polymerase-mediated and double-stranded circular template-specific rescue of persisted circular genomes. In mouse liver, vector genomes of both genome formats seemed to persist primarily as episomal circular forms, but sc vectors converted into circular forms more rapidly and efficiently. However, the overall differences in vector genome abundance and structure in the liver between ss and sc vectors could not account for the remarkable differences in transduction. Molecular structures of persistent genomes of both ss and sc vectors were significantly more heterogeneous in macaque liver, with noticeable structural rearrangements that warrant further characterizations.

Introduction

Adeno-associated virus (AAV)-based vectors are the most promising for achieving safe and stable transgene expression in the liver. The discovery of several new AAV serotypes with strong hepatocyte tropism improved the utility of this technology for liver-directed gene transfer for a variety of inherited and acquired disorders (Gao et al., 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005). AAV vectors derived by trans-encapsidation of conventional single-stranded (ss) AAV vector genomes carrying AAV2 inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) with capsids from several new AAV serotypes such as AAV7, AAV8, and AAV9 significantly enhanced liver transduction in murine, canine, and nonhuman primate (NHP) models (Davidoff et al., 2005; Gao et al., 2005, 2006a; Alexander et al., 2008). The combination of those new AAV serotypes with the self-complementary (sc) vector genome design further improved transduction efficiency of AAV vectors in the liver of both small and large animals (Hirata and Russell, 2000; McCarty et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2003; Gao et al., 2006b; Nathwani et al., 2006).

Extensive studies with ss AAV2 vector have delineated a model for the primary pathways of AAV vector genome metabolism. AAV enters the cell through receptor-mediated endocytosis, trafficks to the nucleus, uncoats its capsid, and releases its transcriptionally inactive ss DNA genome (Summerford and Samulski, 1998; Qing et al., 1999; Summerford et al., 1999; Thomas et al., 2004). This is followed by conversion of its genome into a transcriptionally active double-stranded (ds) form through either a second-strand synthesis or a self-annealing pathway, which is bypassed in the design of the sc genome format (Ferrari et al., 1996; Fisher et al., 1996; Hirata and Russell, 2000; McCarty et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2003, 2007; Zhong et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2008). Because the only viral component in the vector genome is the ITR, the genomes take advantage of host cellular mechanisms such as DNA repair pathways to accomplish intra- or intermolecular nonhomologous end joining of their free ends. This leads to either circular or linear concatemeric products for genome stabilization (Yang et al., 1997, 1999; Song et al., 2001, 2004; Nakai et al., 2003). Cellular mechanisms contributing to AAV vector genome processing and its kinetics remain to be fully understood.

Molecular processes for genome metabolism and persistence of ss and sc AAV vector serotypes in mouse and NHP liver have not been systematically characterized in one study. In the present study, we used mouse liver as a model and the β subunit of macaque-derived choriogonadotrophic hormone (rhCG) as a quantitative reporter gene to compare liver transduction efficiency of different ss and sc AAV vector serotypes (Zoltick and Wilson, 2000). Molecular studies were performed with DNA-modifying and restriction enzymes, isothermal phage polymerase, and DNA hybridization analysis as tools to characterize vector genome structures in liver at early and late stages of gene transfer. A similar analysis was performed in macaques that received similar vectors delivered to the liver.

Materials and Methods

Molecular construction and production of ss and sc vectors

Molecular clones of ss and sc AAV vector genomes were kindly provided by X. Xiao (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA) into which rhCG gene was subcloned behind the cytomegalovirus (CMV)-enhanced chicken β-actin (CB) promoter and used for vector production as previously described (Gao et al., 2006b).

Animal experiments

C57BL/6 mice (male, 6–8 weeks old) were used for studying ss and sc vectors in liver-directed gene transfer at various doses (1 × 1010, 3 × 1010, and 1 × 1011 genome copies [GCs] per mouse). Cynomolgus (Cyno) macaques (Philippine origin and captive bred, 2.61–4.47 kg; ssAAV7, AJ62 and ATX2; scAAV7, AJ7R and AJ62; scAAV8, AT3E and AT3F) were treated and cared for at a contract NHP facility (Alphagenesis, Yemassee, SC) during the study. Both mouse and NHP experiments were performed according to study protocols approved by the Environment Health and Safety Office, the Institutional Biosafety Committee, and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, PA), and the IACUC of Alphagenesis. Vector administration (5 × 1011 GC/kg for both ss and sc vectors) and sample collection for the NHPs, and rhCG analysis for both murine and NHP studies, were performed as previously described (Gao et al., 2006a). A paper describing the NHP experiment in terms of rhCG expression, biodistribution, and copy number of vector genomes in liver has been published (Gao et al., 2006b).

Molecular analysis of vector genomes

Animal tissue collection and DNA extraction were carried out as previously described. Vector GCs in tissue samples were quantified by TaqMan polymerase chain reaction (PCR) under the conditions previously described. To study the molecular status of vector genomes in tissue DNAs, ExoI exonuclease (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA), Plasmid-Safe ATP-dependent DNase (Epicenter, Madison, WI), and bacteriophage ϕ29 DNA polymerase (Epicenter) were used as instructed by the manufacturers. Southern blot analyses were carried out as previously described by using probes that hybridized to different parts of ss and sc vector genomes. In some experiments in which limited amounts of tissue DNA were available, the first probe was stripped off the blots in 1 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA, and 0.1 × Denhardt's solution at 75°C for 2 hr, followed by hybridization with the second probe.

Results

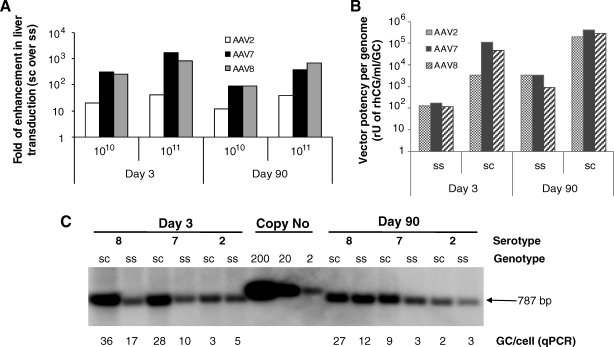

Self-complementary AAV vector genomes across different serotypes were substantially more efficient in transducing murine liver than vectors with single-stranded genomes

We first performed side-by-side studies in livers of C57BL/6 mice and cynomolgus macaques for efficiency of liver-directed rhCG gene transfer mediated by ss and sc AAV vectors packed with capsids from serotypes 2, 7, and 8, respectively. The transduction data of these vectors from 3 days to 7 months after vector perfusion in macaque liver has been reported previously (Gao et al., 2006b). In macaques the sc AAV7 vector yielded stable levels of expression that were about 2 logs higher than with the ssAAV7 vector (Gao et al., 2006b). As reported by several other groups, our comparison in mice revealed a difference of up to 3 logs of enhancement in serum rhCG levels by sc AAV vectors (Gao et al., 2006b) (Fig. 1A). Our study also indicated that the magnitude of enhancement by the sc genome was capsid dependent. When relative expression from an sc cassette was compared with that from an ss cassette, AAV7 and AAV8 produced 100- to 1000-fold increases in the mouse at both early (day 3) and late (day 90) time points as compared with a 10- to 20-fold increase with AAV2 (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, the abundance of sc AAV vector genomes at a dose of 5 × 1012 GC/kg in liver, as quantified by either Southern blot or TaqMan PCR, was no more than a few folds higher than that of ss genomes in mice (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

Comparison of improvement in liver transduction by AAV serotype vectors with a self-complementary (sc) genome over a conventional single-stranded (ss) genome; abundance of vector genomes detected in mouse liver and biological activities of the vectors on a per-genome basis at various stages of gene transfer. (A) Enhancement of liver transduction by AAV vectors with an sc genome over an ss genome in mouse liver. Four- to 6-week-old male C57BL/6 mice were treated via portal vein injection with AAV serotype 2, 7, and 8 vectors (1010 or 1011 genome copies [GC]/animal) carrying ss and sc genomes and expressing choriogonadotrophic hormone (rhCG) under the control of a CMV-enhanced chicken β-actin promoter. Sera were collected from the animals on days 3 and 90 after vector administration for an ELISA-based rhCG assay. Transgene expression data are presented as the fold increase in sc over ss genomes. (B) Comparison of biological activities of vectors on a per-genome basis between different AAV serotypes and genotypes at different stages of gene transfer. Only data from the animals that received high-dose vectors (1011 GC/mouse) were analyzed. (C) Comparison of genome abundance in mouse livers that had received sc and ss vectors; comparison done on days 3 and 90 after vector delivery. Total cellular DNAs were extracted from mouse livers and subjected to either real-time PCR quantification or DNA hybridization analysis after BamHI and HindIII digestion to drop an internal 787-bp fragment. An 800-bp rhCG cDNA fragment was used as a probe for hybridization.

We then analyzed biological activity of the vectors on a per-genome basis (i.e., serum rhCG level [rU/ml] divided by vector genome copy per liver cell as determined by qPCR quantification). Self-complementary vectors of all serotypes were more biologically potent than ss vectors both on days 3 (25- to 647-fold more) and 90 (61- to 304-fold more; Fig. 1B).

Vector genome metabolism of single-stranded and self-complementary AAV vectors in mouse liver

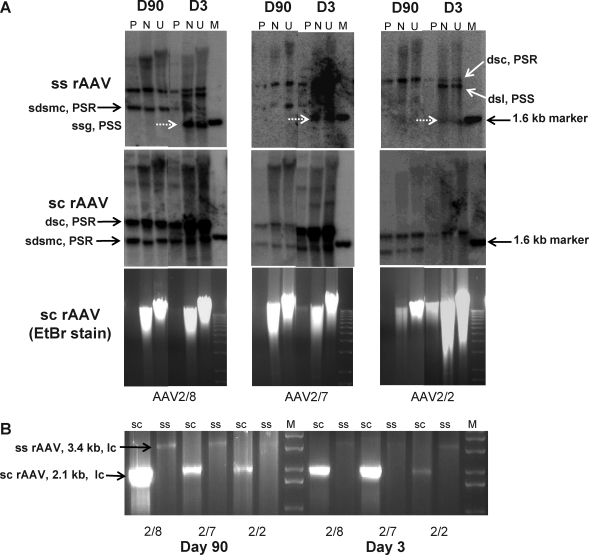

In an attempt to probe molecular forms of AAV vectors in mouse liver, we used an ATP-dependent exonuclease, Plasmid-Safe (PS). PS efficiently digests linear ds DNA, and circular and linear ss DNA, but has no hydrolytic activity on nicked or closed ds circular DNA. This enzyme has been used for the characterization of episomally persisting viral and vector genomes in animal tissues (Agron et al., 2001; Liles et al., 2003; Schnepp et al., 2003, 2005; DeLong et al., 2006). In this experiment, liver DNAs harboring ss and sc AAV vector genomes were treated with EcoRV, a noncutter in the genome, and PS at the amount that destroyed more than 99.5% of spiked-in linear vector genomes (10 units/μg of total cellular DNA; data not shown), followed by Southern blot analysis. Our data indicated that EcoRV digestion did not noticeably change the banding pattern and intensity of bands that were hybridized with the transgene probe (Fig. 2A). Whereas PS digestions efficiently hydrolyzed the cellular DNAs as illustrated by ethidium bromide (EtBr)-stained agarose gel images for liver DNAs from the animals receiving AAV vectors, Southern blot analysis for the ss and sc genomes at different stages of liver transduction depicted distinct molecular forms that were PS resistant (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Characterization of circular molecular forms of AAV vector genomes in mouse liver. (A) Mouse liver DNAs from the animals received AAVCBrhCG vectors (10 μg each) were either not treated (U) or treated with EcoRV, a restriction enzyme that does not cut within the vector genomes (N), or with Plasmid-Safe exonuclease (P), at 37°C overnight. M, molecular weight marker. The samples were then subjected to gel electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel followed by DNA hybridization analysis with an rhCG cDNA probe. (B) The PS-treated samples were also subjected to rolling circular linear amplification (RCLA). One-twentieth of each RCLA product was cut with NotI, a single-cutter in the vector genome, and analyzed on ethidium bromide (EtBr)-stained 1% agarose gels. PSR, Plasmid-Safe resistant; PSS, Plasmid-Safe sensitive; dsc, double-stranded circle; sdsmc, supercoiled double-stranded monomeric circle; ssg, single-stranded genome; lc, linearized circle; dsl, double-stranded linear genome.

The majority of bands from the ss groups were PS sensitive (PSS; Fig. 2A) on day 3. Two PSS bands detected in the ss AAV vector groups likely represented the newly formed ds linear genomes (right below the PSR ds circular genomes) and the incoming ss form of ss AAV vector genomes (right below the 1.6-kb marker band), respectively. The majority of bands from the sc groups were PS resistant (PSR). One common band appeared in all serotypes of sc AAV vector-treated liver, which seemed to consist of both PSR and PSS genomes as evidenced by the reduction in its intensity after PS treatment. However, one additional smaller PSR band was visible only in sc AAV7- and sc AAV8-treated liver, which could represent supercoiled ds circular genomes (Fig. 2A). By day 90, regardless of their original genotypes and serotypes, no more PSS genomes were detectable (Fig. 2A).

We then exploited an isothermal bacteriophage ϕ29 DNA polymerase to corroborate the presence of ds circular genomes (i.e., PSR). This enzyme specifically amplifies ds circular DNA substrate through a rolling circle linear amplification (RCLA) and strand displacement mechanism. In this analysis, PS-treated liver DNAs were subjected to random hexamer-mediated multiply primed RCLA (Nelson et al., 2002; Dahl et al., 2004; Inoue-Nagata et al., 2004; Rector et al., 2004; Schnepp et al., 2005). Abundance and identity of the amplified circular vector genomes were examined by NotI digestion, which cuts once in the circular genomes of both ss and sc AAVs, releasing unilength linear genomes (2.1 kb for sc genomes and 3.4 kb for ss genomes). The results verified that the RCLA products (i.e., circular ds genomes) were more prevalent with sc genomes than with ss genomes for all three serotypes, and with serotypes 7 and 8 than with AAV2 and on day 90 than on day 3 (Fig. 2B).

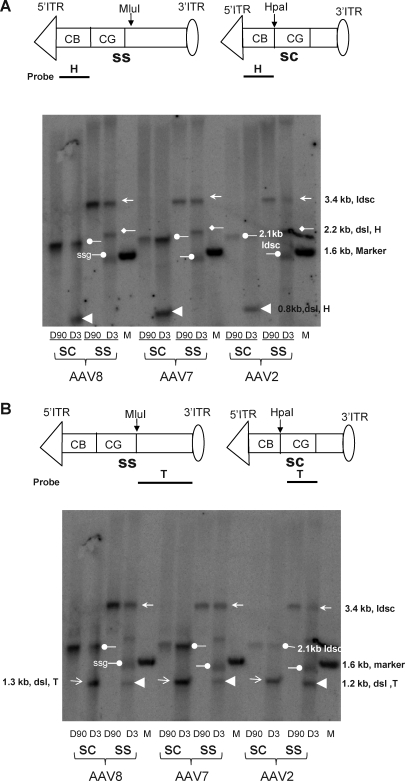

To further elucidate the molecular dynamics of genome processing and the persistence of ss and sc AAV, mouse liver DNAs were treated with single-cutter enzymes in the vector genomes, HpaI for sc AAVs and MluI for ss AAVs, followed by DNA hybridization analysis using separate probes that bind 5′ (H probe) or 3′ (T probe) to the cutting sites. These polarity probes allow us to differentiate linear genomes with free ends from other forms. Table 1 summarizes potential proviral genome structures and predicted bands after Southern blot analysis of liver DNAs treated with various single-cutter enzymes (MluI for ss genomes and HpaI for sc genomes) and their detection with various probes.

Table 1.

Provirus Structures and Predicted/Detected Bands by Various Restriction Enzyme Digestions and Probes in DNA Hybridization Analysis

| |

ss AAV |

sc AAV |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

5′ Probe |

3′ Probe |

5′ Probe |

3′ Probe |

||||||||

| |

MluI |

HpaI |

||||||||||

| |

|

Detected |

|

Detected |

|

Detected |

|

Detected |

||||

| Provirus structure | Predicted | Day3 | Day90 | Predicted | Day3 | Day90 | Predicted | Day3 | Day90 | Predicted | Day3 | Day90 |

| Circular monomer | 3.4 kb | 3.4 kb | 3.4 kb | 3.4 kb | 3.4 kb | 3.4 kb | 2.1 kb | 2.1 kb | 2.1 kb | 2.1 kb | 2.1 kb | 2.1 kb |

| Circular dimer head—head | 4.4 kb | ND | ND | 2.4 kb | ND | ND | 1.6 kb | ND | ND | 2.6 kb | ND | ND |

| Circular dimer tail–tail | 4.4 kb | ND | ND | 2.4 kb | ND | ND | 1.6 kb | ND | ND | 2.6 kb | ND | ND |

| Circular dimer head–tail | 3.4 kb | 3.4 kb | 3.4 kb | 3.4 kb | 3.4 kb | 3.4 kb | 2.1 kb | 2.1 kb | 2.1 kb | 2.1 kb | 2.1 kb | 2.1 kb |

| Linear monomer | 2.2 kb | 2.2 kb | ND | 1.2 kb | 1.2 kb | ND | 0.8 kb | 0.8 kb | ND | 1.3 kb | 1.3 kb | ND |

| Linear dimer head–heada | 4.4 kb | ND | ND | 1.2 kb | 1.2 kb* | ND | 0.8 kb | 0.8 kb* | ND | 2.6 kb | ND | ND |

| Linear dimer tail–taila | 2.2 kb | 2.2 kb* | ND | 2.4 kb | ND | ND | 1.6 kb | ND | ND | 1.3 kb | 1.3 kb* | ND |

| Linear dimer head–tailb | 2.2 kb | 2.2 kb | ND | 1.2 kb | 1.2 kb | ND | 0.8 kb | 0.8 kb | ND | 1.3 kb | 1.3 kb | ND |

| 3.4 kb | 3.4 kb | 3.4 kb | 3.4 kb | 3.4 kb | 3.4 kb | 2.1 kb | 2.1 kb | 2.1 kb | 2.1 kb | 2.1 kb | 2.1 kb | |

| Single-stranded genome | <1.6 kb | <1.6 kb | ND | <1.6 kb | <1.6 kb | ND | None | ND | ND | None | ND | ND |

Abbreviation: ND, not detected.

Because only one predicted fragment of the vector genome (indicated by asterisks) was detected on day 3 by the corresponding polarity probe, the results from DNA hybridization analysis rule out the presence of these two provirus structures at the levels that are detectable by the assay.

No detection of the predicted fragments on day 90 by the corresponding polarity probe suggests the absence of this molecular form at the detection sensitivity of the assay. However, our analysis cannot exclude the presence of this structure on day 3.

Our data showed that, in mouse liver that received ss AAV vector of different serotypes on day 3, the molecular forms detected with either H or T probe were the same, namely, ds circles in either monomeric or head–tail concatemeric form (3.4-kb band by both probes, indicated by left arrows), double-stranded linear monomer or concatemer (3.4-kb band by both probes, indicated by left arrows or 2.2- and 1.2-kb bands by H and T probes, pointed by left diamond and left arrowhead, respectively), and the input single-stranded genomes (below the 1.6-kb marker band by both probes, pointed by right circles) (Fig. 3A and B and Table 1).

FIG. 3.

DNA hybridization analysis of molecular forms of vector genomes in mouse liver DNA after digestion with a single-cutter restriction enzyme. Liver DNAs were extracted on days 3 and 90 from animals receiving various AAV serotype vectors with various genotypes and digested with either MluI (ss) or HpaI (sc). (A) DNA hybridization analysis with a 5′ probe (H probe). (B) DNA hybridization analysis with a 3′ probe (T probe). ldsc, linearized double-stranded circle; dsl, H: double-stranded linear genome, head; dsl, T: double-stranded linear genome, tail; ssg, single-stranded genome.

However, in the sc AAV vector-treated liver on day 3, only linear double-stranded monomer (0.8 and 1.3 kb by H and T probes, indicated by left arrowhead and right arrows, respectively) or H–T concatemer (2.1 kb by both probes, indicated by left circles; 0.8 and 1.3 kb by H and T probes, indicated by left and right arrows, respectively) as well as circular ds monomeric or H–T concatemeric genomes (2.1 kb by both probes, indicated by left circles) were detected in all serotype groups (Fig. 3A and B and Table 1). As expected, no ss molecular forms were present in the liver of those animals. In a good correlation with the real-time PCR data, the differences in genome abundance between the animals receiving AAV7 and AAV8 and those injected with AAV2 were significantly higher in the sc vector groups than in the ss vector groups (Fig. 3A and B and Fig. 1C). By day 90, molecular structures of persistent ss and sc AAV vector genomes became simplified; the molecular forms that represent either monomeric or H–T concatemeric circular genomes were primarily identified by both H and T probes for all serotypes and genotypes of AAV vectors (i.e., 3.4-kb band for ss genomes and 2.1-kb band for sc genomes, indicated by left arrows and left circles respectively; Fig. 3A and B and Table 1).

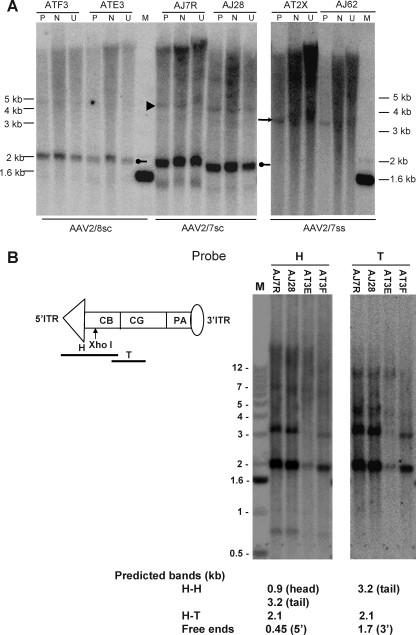

Molecular analysis of persistent vector genomes in macaque liver

Analysis of NHP liver was restricted to the time of necropsy of animals previously described (Gao et al., 2006b). The same PS digestion was applied to macaque liver samples. The result from Southern blot analysis indicated that, as observed in murine liver on day 90, the predominant molecular forms of the vector genomes were PSR (indicated by a right arrow for ss genome and left dot for sc genome) from all vector serotypes at the late time point (day 209; Fig. 4A). However, detection of some higher molecular weight PSR bands by the probe (indicated by a triangle) also suggested the presence of some concatemeric genomes (Fig. 4A). The abundance of a PSR population correlates well with the abundance of genomes as detected by real-time PCR and the data from transgene expression analysis as reported previously (Gao et al., 2006b).

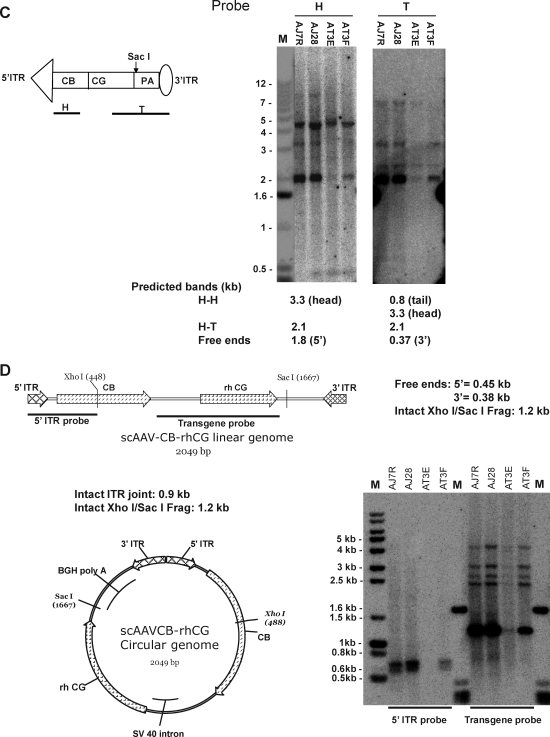

FIG. 4.

DNA hybridization analysis of molecular forms of vector genomes in the liver of macaques infused with ss and sc AAV vectors. Ten micrograms each of cellular DNAs from macaque livers harvested at the end of study were subjected to various exonuclease and restriction endonuclease digestions. (A) Detection of PS-resistant vector genomes by DNA hybridization analysis. Macaque liver DNAs from the animals that received AAVCBrhCG vectors (10 μg each) were either not treated (U) or treated with EcoRV, a restriction enzyme that does not cut within the vector genomes (N), or with Plasmid-Safe exonuclease (P) at 37°C overnight. M, molecular weight marker. (B and C) Diagnosis of molecular forms of vector genomes in macaque liver by various single- and double-cutter restriction enzyme digestions and DNA hybridization analysis. Liver DNAs from sc recombinant AAV (scrAAV)-treated animals (scrAAV7, AJ7R and AJ28; scrAAV8, AT3E and AT3F) were digested with two different single cutters individually, either XhoI or SacI [(B) and (C), respectively]. H–H, head-to-head; H–T, head-to-tail. (D) Liver DNAs from sc vector-treated animals were digested with two sets of single cutters together (XhoI + SacI). Those single cutters cut at the ends of vector genomes. The blots were hybridized with 5′ and 3′ probes separately.

Extensive characterization of NHP liver DNAs for molecular configurations of the persistent sc AAV vector genomes was carried out with a panel of single-cutter restriction enzymes and Southern blot analysis. The panel of selected single-cutter restriction enzymes were KpnI, XhoI, HpaI, PstI, SacI, and SphI for the scAAVCBrhCG genome and AleI, XhoI, HpaI, MluI, SacI, PstI, and SphI for the ssAAVCBrhCG genome. The digestion sites of those enzymes are located either close to 5′ or 3′ ITRs or elsewhere in the transgene. In addition, we focused our analysis on the regions near the ITR–ITR junctions to evaluate concatemerized molecules by double digestions with two different single cutters near the 5′ and 3′ ITR ends. The blots were hybridized with 5′-derived head (H) and 3′-originated tail (T) probes separately to identify different molecular forms and to detect free ends.

After digestion of liver DNAs from the animals that received sc vectors with the seven restriction enzymes listed previously in different combinations, DNA hybridization analyses were performed. The data revealed some unexpected and convoluted banding patterns, in addition to what was observed in mice (data not shown). A representative set of the results from the analyses of the sc genomes by two enzymes, XhoI and SacI, is presented in Fig. 4B and C, respectively. In the separate digestions, both H and T probes identified a strong band that was slightly smaller than the unilength genome size of 2.1 kb in all four liver samples (AJ7R and AJ28 received rcrAAV7; AT3E and AT3F were treated with scrAAV8), possibly representing either circular monomer or circular HT concatemers (Fig. 4B and C). Another band (∼3 kb) detected by the probes in both digestions could potentially be assigned to H–H circular concatemers because no right bands from free ends were noticed (Fig. 4B and C). Some other unexpected bands detected by either the H or T probe in SacI and XhoI single digestions could be explained only by recombination, deletion, and rearrangement events near the ITR junctions that might have compromised the integrity of those restriction sites (Fig. 4B and C and Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Summary of molecular fate of AAV vector genomes in mouse (A) and macaque (B) liver, based on the results of single-cutter digestion and DNA hybridization study. The dotted circles mark the regions in the persistent vector genomes that might have been deleted or rearranged.

The combined digestion of sc genomes in NHP liver with XhoI and SacI yielded two closely migrating fragments that appeared to be smaller than the expected 0.9-kb ITR junction band by the 5′ ITR probe (Fig. 4D). However, for all samples, in addition to the dominant internal band of 1.2 kb (Fig. 4D), multiple unexpected transgene bands were highlighted by the transgene probe, ranging from 2 to 4 kb in size (Fig. 4D). These digestions corroborated the observation from the separate single-cutter digestions, that is, a destabilizing impact of intra- and intermolecular recombination on the integrity of regions around the ITR junctions, which were previously documented in some mouse liver studies (Fig. 5B) (Yang et al., 1997, 1999; Song et al., 2001, 2004; Nakai et al., 2003). Because of the lower abundance of persisting genomes in the ss vector-treated livers (0.5–1 GC/cell), molecular structure analysis by DNA hybridization was less conclusive than that for the sc vector genomes (data not shown).

Discussion

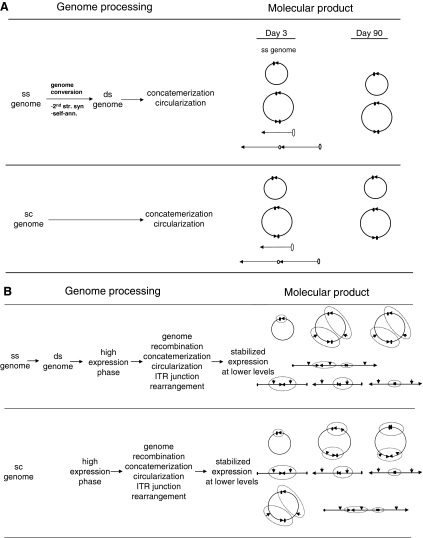

The main objectives of this study were to characterize genome structures of various serotypes of ss and sc AAV vectors in AAV-transduced mouse and NHP liver and to investigate potential molecular mechanism(s) that contribute to the enhanced transduction efficiency by sc vectors. To this end, we first compared various serotypes of ss and sc vector in murine liver for their efficiency in delivering a secreted reporter gene, rhCG. Our results not only confirmed significantly higher levels of transgene expression from sc over ss vectors as reported by other studies, but also illustrated higher biological potency of sc vectors on a per-genome basis. The question is, what molecular mechanism(s) contribute to such a difference in potency between the two genome forms? Although our data from the present study did not fully elucidate such a mechanism(s), it indeed revealed some important differences between mice and NHPs in the processing of rAAV genomes.

Previous studies have established that intra- and intermolecular circularization is the primary pathway for genome processing and persistence of AAV vectors in a variety of target tissues (Yang et al., 1997, 1999; Song et al., 2001, 2004; Nakai et al., 2003). Those studies also elegantly characterized three major cellular pathways for the removal of ds free ends from vector genomes in the murine liver (Yang et al., 1997, 1999; Song et al., 2001, 2004; Nakai et al., 2003). However, cellular pathways/mechanisms for AAV vector genome metabolism in primate liver remain to be elucidated.

In the present study, we proposed that the substrate for the formation of transcriptionally active and stabilized circular genomes is most likely the ds linear genomes. Substantially improved vector potency for sc over ss AAV vectors could be potentially attributed to differences in the efficiency of genome circularization. Whereas sc genomes, once uncoated in the nucleus, are immediately available for circularization, ss genomes need to undergo genome conversion to form ds molecules before circularization, the efficiency and kinetics of which appear to be serotype and target cell dependent (Ferrari et al., 1996; Fisher et al., 1996; Hirata and Russell, 2000; McCarty et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2003, 2007; Zhong et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2008). The limiting steps in uptake of vector are capsid specific but independent of the genome (i.e., ss and sc), but an additional downstream barrier for ss genomes would be their conversion into ds forms (Fig. 1).

In addition, our side-by-side analysis of persistent genomes of the same vectors in the liver of both species has elicited some differences between murine and primate livers in the metabolism of AAV vector genomes. The processes of genome conversion from ss to ds form might be less efficient in NHPs. Differences between sc and ss AAV7 vectors in the abundance of persistent vector genomes were noticeably more pronounced in the NHP liver (>10-fold vs. 2- to 3-fold in mice) (Gao et al., 2006b) (Fig. 1C). One of the important factors that might have confounded our analysis is that intravenously delivered rAAV, particularly rAAV7 and rAAV8 used in this study, has proven to efficiently transduce muscle, heart, and pancreas as well in mice (Wang et al., 2005, 2006; Zincarelli et al., 2008), although little is known about the transduction efficiency of systemically delivered rAAVs in nonliver tissues of NHPs. In our present study, because a ubiquitous chicken β-actin promoter was used to drive rhCG expression, the rhCG secreted from other transduced tissues also contributed to the total serum rhCG readout. This might have, at least partly, encumbered our attempt to correlate rhCG levels with the abundance of the persistent vector genomes in liver only. It is also possible that the larger differences observed in NHPs could be due to the differences in vector doses between the mouse and NHP experiments (10-fold greater in mice on a GC/kg basis) and resulting threshold effect/nonlinear dose response as reported for adenoviral vector-mediated liver gene transfer (Tao et al., 2001). Nevertheless, expression levels of rhCG from sc AAV7 vector-treated NHPs remained significantly higher than in those receiving ss AAV7 vector at both peak (519-fold on day 3) and stabilized levels (182-fold on day 209) (Gao et al., 2006b).

Extensive analyses of the structures of persisting genomes by different methods corroborated that AAV vector genome metabolism in mouse liver is relatively simple and that intramolecular circularization is the predominant fate for genome stabilization (Fig. 5A). Self-circularization represents a major pathway for AAV vector genome metabolism in NHP liver. When the same vectors were compared in mouse and NHP livers, the profiles of persistent molecular forms in NHP liver appeared to be more complicated (Fig. 4). Considerably more intermolecular recombination events were observed, most of which likely represented H–H or H–T circular concatemers because no free ends were detected. One alternative interpretation to these unpredicted banding patterns could be incomplete restriction enzyme digestion. However, additional analyses of the persistent sc AAV vector genomes with several other single-cutter restriction enzymes (i.e., AleI, HpaI, MluI, PstI, and SphI) in different combinations all gave rise to some inexplicable bands (data not shown), which could unlikely be explained by partial digestions for all the cases. Conversely, it may further corroborate the prevalence of intermolecular recombination pathways in the vector genome metabolism in NHP liver. It is worthwhile to point out that one of the potential genetic fates of vector genomes in primate liver could be recombination between the genomes of vector and endogenous AAVs, although the existence and consequences of this kind of recombination remain to be substantiated.

Nevertheless, our data revealed that both intramolecular (circularization) and intermolecular recombination (concatemerization) of AAV vector genomes in the NHP liver could cause deletions/rearrangements of ITR junctions and adjacent regions (Figs. 4B and 5B). This may impact on the integrity of a transgene cassette, particularly in the promoter and poly(A) regions for their close vicinity to the ITRs. Another possible cause for the undersized ITR junctions (i.e., smaller than 0.9 kb) as shown in Fig. 4B could be the formation of double-D ITR junctions in the process of inter- or intravector genome recombination (Yan et al., 2005), which remains to be substantiated by the next phase of our study: to rescue and sequence the ITR junctions in persistent vector genomes from macaque liver.

Taken together, molecular forms of persistent vector genomes in NHP liver were significantly more heterogeneous than those in murine liver. This might be indicative of different and possibly more complicated molecular pathways and mechanisms in the metabolism of vector genomes in NHP liver, which warrant further investigation. Further understanding of the interactions among vector–vector, vector–endogenous AAV, and vector–host genomes, as well as the host factors that are involved in such interactions, are among the critical paths toward clinical development of AAV vectors for liver gene therapy applications.

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly appreciate the technical support provided by Julio Sanmiguel. The contributions of the Vector and Immunology Cores, and of the NHP Program of the Gene Therapy Program of the University of Pennsylvania, are appreciated. This work was funded by grants to J.M.W. from NIDDK P30 DK47757, NHLBI P01 HL59407, NICHD P01 HD57247, and GlaxoSmithKline, Inc.

Author Disclosure Statement

G.P.G. is an inventor on patents licensed to various companies. J.M.W. is a consultant to ReGenX Holdings, and is a founder of, holds equity in, and receives a grant from affiliates of ReGenX Holdings; in addition, he is an inventor on patents licensed to various biopharmaceutical companies, including affiliates of ReGenX Holdings.

References

- Agron P.G. Walker R.L. Kinde H. Sawyer S.J. Hayes D.C. Wollard J. Andersen G.L. Identification by subtractive hybridization of sequences specific for Salmonella enterica serovar enteritidis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001;67:4984–4991. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.11.4984-4991.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander I.E. Cunningham S.C. Logan G.J. Christodoulou J. Potential of AAV vectors in the treatment of metabolic disease. Gene Ther. 2008;15:831–839. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl F. Baner J. Gullberg M. Mendel-Hartvig M. Landegren U. Nilsson M. Circle-to-circle amplification for precise and sensitive DNA analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:4548–4553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400834101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidoff A.M. Gray J.T. Ng C.Y. Zhang Y. Zhou J. Spence Y. Bakar Y. Nathwani A.C. Comparison of the ability of adeno-associated viral vectors pseudotyped with serotype 2, 5, and 8 capsid proteins to mediate efficient transduction of the liver in murine and nonhuman primate models. Mol. Ther. 2005;11:875–888. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLong E.F. Preston C.M. Mincer T. Rich V. Hallam S.J. Frigaard N.U. Martinez A. Sullivan M.B. Edwards R. Brito B.R. Chisholm S.W. Karl D.M. Community genomics among stratified microbial assemblages in the ocean's interior. Science. 2006;311:496–503. doi: 10.1126/science.1120250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari F.K. Samulski T. Shenk T. Samulski R.J. Second-strand synthesis is a rate-limiting step for efficient transduction by recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors. J. Virol. 1996;70:3227–3234. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.3227-3234.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher K.J. Gao G.P. Weitzman M.D. Dematteo R. Burda J.F. Wilson J.M. Transduction with recombinant adeno-associated virus for gene therapy is limited by leading-strand synthesis. J. Virol. 1996;70:520–532. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.520-532.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G.P. Alvira M.R. Wang L. Calcedo R. Johnston J. Wilson J.M. Novel adeno-associated viruses from rhesus monkeys as vectors for human gene therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:11854–11859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182412299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G. Alvira M.R. Somanathan S. Lu Y. Vandenberghe L.H. Rux J.J. Calcedo R. Sanmiguel J. Abbas Z. Wilson J.M. Adeno-associated viruses undergo substantial evolution in primates during natural infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:6081–6086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0937739100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G. Vandenberghe L.H. Alvira M.R. Lu Y. Calcedo R. Zhou X. Wilson J.M. Clades of adeno-associated viruses are widely disseminated in human tissues. J. Virol. 2004;78:6381–6388. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6381-6388.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G. Vandenberghe L.H. Wilson J.M. New recombinant serotypes of AAV vectors. Curr. Gene Ther. 2005;5:285–297. doi: 10.2174/1566523054065057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G. Lu Y. Calcedo R. Grant R.L. Bell P. Wang L. Figueredo J. Lock M. Wilson J.M. Biology of AAV serotype vectors in liver-directed gene transfer to nonhuman primates. Mol. Ther. 2006a;13:77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G.P. Lu Y. Sun X. Johnston J. Calcedo R. Grant R. Wilson J.M. High-level transgene expression in nonhuman primate liver with novel adeno-associated virus serotypes containing self-complementary genomes. J. Virol. 2006b;80:6192–6194. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00526-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata R.K. Russell D.W. Design and packaging of adeno-associated virus gene targeting vectors. J. Virol. 2000;74:4612–4620. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.10.4612-4620.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue-Nagata A.K. Albuquerque L.C. Rocha W.B. Nagata T. A simple method for cloning the complete begomovirus genome using the bacteriophage ϕ29 DNA polymerase. J. Virol. Methods. 2004;116:209–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2003.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liles M.R. Manske B.F. Bintrim S.B. Handelsman J. Goodman R.M. A census of rRNA genes and linked genomic sequences within a soil metagenomic library. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003;69:2684–2691. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.5.2684-2691.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty D.M. Monahan P.E. Samulski R.J. Self-complementary recombinant adeno-associated virus (scAAV) vectors promote efficient transduction independently of DNA synthesis. Gene Ther. 2001;8:1248–1254. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai H. Storm T.A. Fuess S. Kay M.A. Pathways of removal of free DNA vector ends in normal and DNA-PKcs-deficient SCID mouse hepatocytes transduced with rAAV vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 2003;14:871–881. doi: 10.1089/104303403765701169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathwani A.C. Gray J.T. Ng C.Y. Zhou J. Spence Y. Waddington S.N. Tuddenham E.G. Kemball-Cook G. McIntosh J. Boon-Spijker M. Mertens K. Davidoff A.M. Self-complementary adeno-associated virus vectors containing a novel liver-specific human factor IX expression cassette enable highly efficient transduction of murine and nonhuman primate liver. Blood. 2006;107:2653–2661. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson J.R. Cai Y.C. Giesler T.L. Farchaus J.W. Sundaram S.T. Ortiz-Rivera M. Hosta L.P. Hewitt P.L. Mamone J.A. Palaniappan C. Fuller C.W. TempliPhi, ϕ29 DNA polymerase based rolling circle amplification of templates for DNA sequencing. Biotechniques (Suppl.) 2002:44–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qing K. Mah C. Hansen J. Zhou S. Dwarki V. Srivastava A. Human fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 is a co-receptor for infection by adeno-associated virus 2. Nat. Med. 1999;5:71–77. doi: 10.1038/4758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rector A. Tachezy R. van Ranst M. A sequence-independent strategy for detection and cloning of circular DNA virus genomes by using multiply primed rolling-circle amplification. J. Virol. 2004;78:4993–4998. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.10.4993-4998.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnepp B.C. Clark K.R. Klemanski D.L. Pacak C.A. Johnson P.R. Genetic fate of recombinant adeno-associated virus vector genomes in muscle. J. Virol. 2003;77:3495–3504. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.6.3495-3504.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnepp B.C. Jensen R.L. Chen C.L. Johnson P.R. Clark K.R. Characterization of adeno-associated virus genomes isolated from human tissues. J. Virol. 2005;79:14793–14803. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14793-14803.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S. Laipis P.J. Berns K.I. Flotte T.R. Effect of DNA-dependent protein kinase on the molecular fate of the rAAV2 genome in skeletal muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:4084–4088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061014598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S. Lu Y. Choi Y.K. Han Y. Tang Q. Zhao G. Berns K.I. Flotte T.R. DNA-dependent PK inhibits adeno-associated virus DNA integration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:2112–2116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307833100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerford C. Samulski R.J. Membrane-associated heparan sulfate proteoglycan is a receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 virions. J. Virol. 1998;72:1438–1445. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1438-1445.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerford C. Bartlett J.S. Samulski R.J. αVβ5 integrin: A co-receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 infection. Nat. Med. 1999;5:78–82. doi: 10.1038/4768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao N. Gao G.P. Parr M. Johnston J. Baradet T. Wilson J.M. Barsoum J. Fawell S.E. Sequestration of adenoviral vector by Kupffer cells leads to a nonlinear dose response of transduction in liver. Mol. Ther. 2001;3:28–35. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C.E. Storm T.A. Huang Z. Kay M.A. Rapid uncoating of vector genomes is the key to efficient liver transduction with pseudotyped adeno-associated virus vectors. J. Virol. 2004;78:3110–3122. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.6.3110-3122.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. Buckley K.J. Yang X. Buchmann R.C. Bisaro D.M. Adenosine kinase inhibition and suppression of RNA silencing by geminivirus AL2 and L2 proteins. J. Virol. 2005;79:7410–7418. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7410-7418.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. Xie J. Lu H. Chen L. Hauck B. Samulski R.J. Xiao W. Existence of transient functional double-stranded DNA intermediates during recombinant AAV transduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:13104–13109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702778104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. Ma H.I. Li J. Sun L. Zhang J. Xiao X. Rapid and highly efficient transduction by double-stranded adeno-associated virus vectors in vitro and in vivo. Gene Ther. 2003;10:2105–2111. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. Zhu T. Rehman K.K. Bertera S. Zhang J. Chen C. Papworth G. Watkins S. Trucco M. Robbins PD others. Widespread and stable pancreatic gene transfer by adeno-associated virus vectors via different routes. Diabetes. 2006;55:875–884. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.04.06.db05-0927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z. Zak R. Zhang Y. Engelhardt J.F. Inverted terminal repeat sequences are important for intermolecular recombination and circularization of adeno-associated virus genomes. J. Virol. 2005;79:364–379. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.1.364-379.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C.C. Xiao X. Zhu X. Ansardi D.C. Epstein N.D. Frey M.R. Matera A.G. Samulski R.J. Cellular recombination pathways and viral terminal repeat hairpin structures are sufficient for adeno-associated virus integration in vivo and in vitro. J. Virol. 1997;71:9231–9247. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9231-9247.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. Zhou W. Zhang Y. Zidon T. Ritchie T. Engelhardt J.F. Concatemerization of adeno-associated virus circular genomes occurs through intermolecular recombination. J. Virol. 1999;73:9468–9477. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.11.9468-9477.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong L. Zhou X. Li Y. Qing K. Xiao X. Samulski R.J. Srivastava A. Single-polarity recombinant adeno-associated virus 2 vector-mediated transgene expression in vitro and in vivo: Mechanism of transduction. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:290–295. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X. Zeng X. Fan Z. Li C. McCown T. Samulski R.J. Xiao X. Adeno-associated virus of a single-polarity DNA genome is capable of transduction in vivo. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:494–499. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zincarelli C. Soltys S. Rengo G. Rabinowitz J.E. Analysis of AAV serotypes 1–9 mediated gene expression and tropism in mice after systemic injection. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:1073–1080. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoltick P.W. Wilson J.M. A quantitative nonimmunogenic transgene product for evaluating vectors in nonhuman primates. Mol. Ther. 2000;2:657–659. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]