Abstract

c4 is a derivative of the mouse hepatoma cell line, Hepa-1, that harbors a mutation in the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Nuclear Translocater gene (Arnt, or Hypoxia Inducible factor 1β {HIF-1β}) leading to loss of activity. Clone 3 cells were generated by introducing a doxycycline-repressible Arnt expression vector into c4 cells. Clone 3 cells were injected subcutaneously into immunosuppressed mice, which were treated with doxycyline a) throughout the growth of the subsequent tumor xenografts, or (b) from day 7 through to the end of the experiment (day 30), or not treated (c). Tumors in all groups grew exponentially between day 14 and day 30, and at rates that were indistinguishable from each other. However, tumors in group a were smaller than those of the other two groups throughout the measureable growth period, while tumor volumes in groups b and c were not significantly different from each other. The degrees of vascularity and apoptosis did not correlate with the differences in degrees of growth between the different groups. Thus Arnt is required during the early stages of growth of the tumors but less in later stages. Since Arnt does not detectably effect the growth kinetics of Hepa-1 cells either during hypoxia or normoxia, this requirement is unlikely to reflect a direct effect of Arnt on cell proliferation, and is therefore probably a consequence of altered interactions(s) between the tumor cells and the host. These studies suggest that Arnt (and HIF-1α/HIF-2α) inhibitors will be particularly effective against smaller tumors, including micrometastases.

INTRODUCTION

Mammalian cells and the whole organism exhibit an adaptive response to low oxygen tension (hypoxia), mediated in part by increases in mRNAs for a number of genes involved in glucose uptake and metabolism, angiogenesis and cell survival, including Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF). Activation of transcription is mediated principally by Hypoxia Inducible Factor (HIF), which consists of one α subunit (HIF-1α or HIF-2α) and one β subunit (HIF-1β{also called the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Nuclear Translocator, or ARNT} or ARNT2). HIF α/β dimers bind to hypoxia response elements (HREs) located in the regulatory regions of responsive genes, thereby stimulating their transcription. During normoxia, the hypoxic response is negated by a number of mechanisms, which mainly impact the α subunits. These mechanisms include, but are not limited to : (i) hydroxylation of the α subunits by oxygen-dependent prolyl hydroxylases, leading to binding of the Von Hippel-Lindau protein (VHL), which results in ubiquitination and proteosomal degradation of the α subunits, and (ii) the oxygen-dependent hydroxylation of an asparagine residue in the HIF-α subunits catalyzed by Factor Inhibiting HIF-1 (FIH) leading to the inhibition of interaction of the HIF-α subunits with the transcriptional coactivator p300. HIF-1α and HIF-2α are also up-regulated in many cancer cells under normoxic conditions, due to the effects of activated protooncogenes or the inactivation of tumor suppressor genes [1]. HIF-1α and ARNT are ubiquitously expressed, whereas HIF-2α and ARNT2 have a more limited expression, with the latter being restricted mainly to neural tissues and the kidney [2-3]. HIF-1α and HIF2-α induce overlapping but different spectra of genes, even within the same cell [4].

Besides HIF-1α and HIF-1β, ARNT is also a dimerization partner for the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR), which mediates induction of various xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes, including cytochrome P4501A1 (CYP2S1) by dioxin and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, such as benzo(a)pyrene.We previously described a mutant derivative, c4, of the mouse hepatoma cell line, Hepa-1, that harbors a point mutation in the Arnt gene that negates the encoded protein’s DNA binding activity and also decreases its stability [5-6]. The Hepa-1 parental cells (and therefore presumably c4 cells) do not express Arnt2 [7]. Soon after HIF-1 was cloned [8], experiments with the c4 mutant provided the first formal demonstration that HIF-1 mediates hypoxic induction of gene transcription [9-10]. The c4 mutant also provided the first evidence that HIF-1 activity is required for optimal growth of tumor xenografts [11]. A great majority of subsequent tumor xenograft experiments (mainly focusing on the HIF-1α subunit) support the notion that HIF-1 is a positive factor for tumor growth, although in a few studies, HIF-1, has been implicated as a negative regulator of tumor growth. {These differences may be due, at least in part, to cell-specific parameters [12-13]. Furthermore, upregulation of HIF-1α in many different types of cancer is generally associated with poor prognosis. These studies have established HIF-1 as a promising target for cancer therapy, and a number of HIF-1 inhibitors are in development [14].

We use here c4 cells harboring a doxycyline-regulatable Arnt cDNA to investigate whether a certain period of xenograft tumor growth is particularly susceptible to down-regulation of Arnt activity. Our results indicate that the most sensitive period is soon after injection of the cells into the animal and prior to the appearance of detectable tumors. These results have important implications for the application HIF-1 inhibitors as therapeutic agents for cancer.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Cell culture and Generation of c4 Tet-off Tre-mArnt cells

Cell lines were grown in alpha MEM media supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Life Technology, Foster City, CA). The mouse Arnt cDNA was cloned using standard cloning techniques into the multiple cloning site of the pRevTRE vector (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) at a Xho I site, forming pRevTRE-mArnt. 293 cells (human embryonic kidney) from ATCC (CRL-1573) were used as the retrovirus packaging cells. For infection with the retroviral vectors, cells were grown to 50% confluence, growth medium was replaced with undiluted viral supernatant, and the cells incubated with virus-containing supernatant for 5 hrs. Supplementary Figure 1 outlines the process of generating cells for the tumor implantation studies. For this procedure, c4 cells were treated with the pRevTet-Off vector and selected in 600 ug/ml G418 two days later. Surviving cells were expanded, infected with the pRevTRE-mArnt vector and selected in 400 ug/ml hygromycin. Surviving cells were expanded, treated with 10 nM dioxin, and then subjected to the reverse selection procedure by replacing the media with 0.75uM benzo[ghi]perylene (B[ghi]P) and then exposing the cells to 40 kJ/m2 near UV radiation [15]. Individual surviving clones were isolated with cloning cylinders, expanded in cell culture, and two days later subjected to selection with 10 ug/ml benzo(a)pyrene [16]. Individual c4 Tet Off TRE-mArnt clones were isolated and tested for stringent regulation of the Tet-Off system by treating them with and without doxycycline (1 ug/ml) for 48 hours, introducing 500ng of a TRE-luciferase reporter plasmid by transfection with 15ul Superfect transfection reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and 24 hours later assaying them for luciferase activity.

Cell Growth Assay

About 800 cells were plated in replicates of three into wells of tissue culture dishes containing treatment buffer (serum-free medium containing 0.1% BSA + either water vehicle or doxycycline at a final concentration of 1ug/ml). These cells were cultured under either normoxia or hypoxia (1% O2). At the day of harvest, the medium was replaced with phenol red-free complete medium + 10% MTS [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethonyphenol)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium] tetrazolium reagent (Owen’s reagent; Promega, Madison, WI). The MTS reagent is bioreduced by cells to a soluble formazan product which can be detected spectrophotometrically for the purpose of quantifying the number of viable cells in each well. After incubation at 37%C for 1 h, medium was removed from the wells, combined, and scored for absorbance at 490 nm using an EL-800 Universal Microplate Reader (Bio-Tek Instruments).

Analysis of Tumor Growth

1 × 106 clone 3 cells in 0.1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were injected subcutaneously into the flanks of athymic nu/nu mice (n=6 for each group) Tumor growth was measured daily with a digital caliper (Fisher Scientific). Tumor volume was calculated by using the standard formula [17] and plotted as a function of time. The formula used was: Tumor volume = (4/3) π (1/2 smaller diameter) 2 (1/2 larger diameter). Doxycycline was delivered in the drinking water (1 mg/ml), the supply of which was changed twice a week. At the indicated time-points, doxycycline was added to the drinking water, to turn off Arnt expression. Mice were sacrificed before tumors reached a diameter of 2.0 cm or at 30 days after tumor implantation.

Western blotting

For western blot analysis, cells were centrifuged and the pellet resuspended in a lysis buffer containing 20mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1mM PMSF, 5mM EDTA, and 1% Triton X-100. The suspension was incubated on ice and sonicated. Protein concentrations were determined and the suspensions loaded onto a polyacrylamide gel in 0.1% SDS. The proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane. Preincubation in a blocking buffer was performed, followed by an affinity-purified Arnt antibody [18] and then a secondary horseradish peroxidase antibody. The membranes were incubated for 1 min in the chemiluminescent substrate ECL and exposed to X-ray film for detection. The membranes were stripped and then tested in the standard method with a β-actin antibody.

Immunohistochemistry

For immunohistochemistry of Arnt and Vegf, tumor tissues that had been fixed with 10% (v/v) neutral buffered formalin were dehydrated and embedded in paraffin. 4-μm sections of fixed embedded tissues were cut on a Leica model 2165 rotary microtome (Leica, Nussloch, Germany), placed on glass slides, deparaffinized, stained, and treated in accordance with the instructions of the LSAB kit from DAKO corporation (Carpinteria, CA, USA). In brief, antigen retrieval was performed by immersing the slides in 0.01% sodium citrate pH 6.0 and incubation for five minutes in boiling water. Endogenous peroxidase activity was inhibited by immersing the slides in 3% H2O2 - methanol for 25 min, and the background nonspecific binding was reduced by incubating with 1% BSA in PBS for 60 min. The slides were incubated overnight at room temperature with antibodies against Arnt (1:250) (Santa Cruz biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), or Vegf (1:500) (Santa Cruz). Finally, the slides were washed five times in PBS, 0.1 M pH 7.4 for eight minutes. After washing, the slides were incubated with a biotinylated secondary antibody in the LSAB kit corporation for 30 minutes at room temperature, followed by an incubation with a streptavidin-HRP conjugate (contained in the LSAB kit) for 30 minutes at room temperature and then with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetra-hydrochloride (liquid DAB, DAKO corporation) for one to five minutes in the dark. The reaction was arrested with distilled water and the slides were counterstained with H&E. Thereafter, the tissues were washed in tap water for five minutes, dehydrated through ethanol baths (70, 90 and 100%), and in xylene, and then mounted with E-2 Mount medium (Shandon lab, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Finally, the slides were analyzed under light microscopy (Olympus BX-40). The analyses were performed by blinded observers. For quantification of the intensity of expression, we used Image-ProPlus 6.3 software (Media Cybernetics, Inc. MD). Briefly, five random 200μ2 fields of each tumor werer evaluated at 400 x magnification. The density of expression of Arnt (brown color) in each tumor is expressed as pixels/200 μ2. To minimize systemic errors and avoid cross-comparison of results of immunohistochemistry, analysis of samples from different experiments or samples processed at different times, immunohistochemical staining for the same antigen was done on all samples from one experiment as one batch at the same time.

Analysis of Blood Vessel Density and Necrosis

Immunohistochemistry staining using a rat anti-mouse CD31 (PECAM) antibody (Pharmingen, BD Biosciences, Toronto, ON) was used to study the blood vessel density in the tumors. Tumors were excised at autopsy, fixed in acetone, and embedded in Optimal Cutting Temperature compound (O.C.T., VWR Scientific), in plastic embedding molds, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and subsequently stored at −70 °C. Cryosections (5 um in thickness) were placed on siliconized microscope slides, fixed in ice-cold acetone, and then stained with the anti-mouse CD31 monoclonal antibody. Representative sections obtained from five tumors from each group were analyzed. Three different fields in each section were examined at 10x magnification. The number of vessels per mm2, average vessel size, and the relative area occupied by tumor blood vessels were measured using Image J software.

Necrotic regions in the tumor sections were identified based on H&E staining and the criteria of shrinkage or loss of the nucleus. The tumor necrotic index was calculated as the size of the encircled necrotic region divided by the size of the whole section.

Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR

Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (QPCR) analysis for Arnt in the snap frozen tumor samples was done using an I-Cycler machine (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA). The primer set was designed to hybridize to a unique sequence in the wild type mouse Arnt cDNA, and to minimize cross-hybridization to the mutant Arnt cDNA in the c4 cells. The primers used for Arnt detection were forward: 5′- AAT TCT GCC TAG TaG CCA TTG G-3′ and reverse: 5′-ACT CAT GTC TGT ACA GTT GGG A-3′. The conditions were; Step 1: 50.0 °C for 2 minutes, 95.0 °C for 2 minutes, followed by 45 cycles of step 2: 95.0 °C for 15 seconds and 60.0 °C for 30 seconds).The forward primer is not a perfect match to the Arnt cDNA, as it has one mismatch nucleotide as indicated by the lowercase letter (and therefore has two mismatch nucleotides for the c4 mutant Arnt cDNA because the c4 mutant Arnt differs from the wild-type sequence at the most 3′ nucleotide of the forward primer, containing an A instead of the most 3′ G in the sequence.) Note that primers with additional missmatches can better discriminate single base pair mutations [19]. The forward primer with the additional mismatch nucleotide indeed showed a much better capability to discriminate the wild-type and c4 mutant Arnt cDNAs (see the Results section). Each reaction was run in triplicate. Data analysis was done using the standard curve method. Amounts of Arnt were normalized to that of the constitutively expressed 36B4 mRNA, which was quantitated by PCR as described previously [20].

Histochemical Detection of Apoptotic Cells and Bodies

Apoptotic cells and bodies were visualized using the ApopTag Plus Peroxidase In Situ Apoptosis Kit (CHEMICON, Temecula, CA). Briefly, after routine deparaffinizaton and rehydration and washing in PBS (50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.4, 200 mM NaC1), tissues were treated with 3.0% hydrogen peroxide for 5 minutes and washed with PBS to quench endogenous peroxidase. After adding the equilibration buffer for 10 mm, TdT enzyme was pipetted onto the sections, which were then incubated at 37°Cfor 1 h. The reaction was stopped by putting sections in stop/wash buffer. After washing, anti-digoxigenin-peroxidase was added to the slides. Slides were washed, stained with diaminobenzine (BioGenex, San Ramon, CA) substrate, and counterstained with methyl green. A positive control slide was used as positive control for staining procedures. Substitution of TdT with distilled water was used as a negative control.

Statistical analysis

The single-factor ANOVA test was used to compare the results across groups. Linear regression model was used to compare tumor growth rates. The ANOVA test and the exponential growth test were performed using the Splus software (Insightful, Seattle, WA). In all analyses, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Generation of cells conditionally expressing Arnt

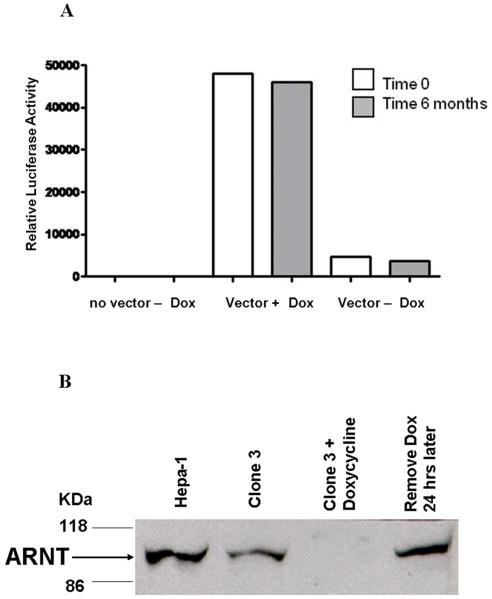

The c4 cell is a derivative of the Hepa-1 mouse hepatoma cell line that harbors a mutation that inactivates Arnt and also diminishes the stability of the protein [6]. The Hepa-1 parental cells (and therefore presumably c4 cells) do not express Arnt2 [7]. We used retroviral infection to sequentially introduce the pRevTet-Off and pRevTRE-mArnt (containing the full length mouse Arnt cDNA sequence) vectors into c4 cells, selecting for cells resistant to G418 and hygromycin, respectively. We used retroviral infection rather than transfection to introduce the vectors because in our experience retrovirally transduced sequences are more stably maintained in the Hepa-1 cell line and its derivatives than sequences introduce by transfection. We applied two selections to isolate a c4 TetOff TRE-mArnt clone in which Arnt was highly regulated by doxycycline (Supplementary Figure 1). First, the pool of c4 TetOff TRE-mArnt cells was subjected to the B[ghi] + near UV “reverse selection procedure” in the absence of doxycycline. This procedure selects for cells that are highly inducible for the Cyp1a1 gene by dioxin via Ahr/Arnt [15]. Second, cells surviving this selection were expanded and subjected to the benzo(a)pyrene selection in the presence of doxycycline. The benzo(a)pyrene selection kills cells that are inducible for Cyp1a1 [16]. Several clones were isolated from the benzo(a)pyrene selection, expanded in culture, grown with or without doxycycline for two days, transfected with the TRE-luciferase vector, and assayed for luciferase activity one day later. Clone 3 demonstrated a high degree of doxycycline repression for luciferase activity (Figure 1A). Importantly, this clone exhibited the same degree of doxycycline regulation of a transiently transfected TRE-luciferase plasmid even after a further six months in continuous culture in the absence of G418, hygromycin and doxycycline, demonstrating that its phenotype was stable. Doxycycline was found to down-regulate the Arnt protein in clone 3 cells at least ten-fold after a two-day treatment, while Arnt expression was fully restored after a further day of growth in the absence of doxycycline (Figure 1B). Clone 3 cells exhibited the same proliferation kinetics in culture as c4 cells and Hepa-1 cells, and doxycycline did not alter the proliferation kinetics of these cells (data not shown). We previously showed that c4 cells exhibit the same doubling time and attain the same maximal cell density in culture as Hepa-1 cells, and that c4 cells (and Hepa-1) cells grow in culture at the same rate under hypoxia (1% O2) as under normoxia [11]. These observations suggest that the differences in xenograft growth parameters between clone 3 cells treated and untreated with doxycycline that we report below are unlikely to be due to any direct effects of Arnt or doxycycline on cell proliferation, and that these differences are also not likely to reflect a cell-autonomous response to hypoxia.

Figure 1.

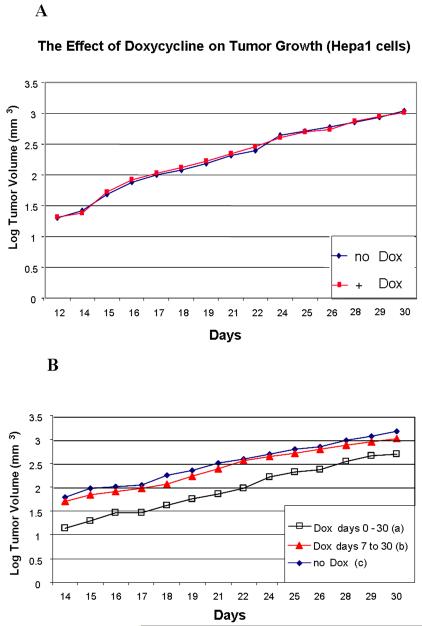

Doxycyline treatment does not affect the growth of xenografts

We implanted Hepa-1 cells into the flanks of nude mice (106 cells per mouse) and then treated the mice with or without doxycyline in the water for a total of 30 days (six mice per group, Figure 2A). We fit a linear regression for each individual tumor using log tumor volume as the outcome variable, and days as the predictor variable. The rate of increase in tumor volume was calculated for each treatment using this model. As a single measure of tumor size, we also calculated the tumor volume at the mid-point of tumor measurements (day 22), using this model. Neither the tumor growth rate nor the estimated mid-point tumor volume differed significantly between the two treatments (p = 0.54, and p = 0.16, respectively). Thus doxycycline had no detectable effect on the growth of these tumors.

Figure 2.

Arnt is required at early stages but only minimally at later stages of tumor growth

106 clone 3 cells were injected subcutaneously into nude mice and doxycycline was administered in the drinking water a) throughout the growth of the tumors (i.e., from day 0 to day 30), b) from day 7 to day 30, or c) not at all. Six mice were analyzed per group. Tumor dimensions were measured daily from day 14, when they were first of sufficient size, and the volumes of the tumors calculated. Mean log tumor volume for each group is plotted against days of growth in Figure 2B. These plots approximated linearity, indicating that the tumors grew exponentially throughout the time period when they were measured. Furthermore, the rates of tumor growth between days 14 and 30 did not differ significantly between the groups. However, the tumor volume in mice fed doxycycline from day 0 to day 30 (group a) was significantly smaller than the tumor volume in mice not fed doxycycline (group c) and those only fed doxycycline from day 7 through day 30 (group b) throughout the tumor growth period (see Table 1 in the Supplementary material). In order to provide a single parameter relating to tumor volume for each treatment regimen, we estimated the tumor volume at the mid time-point of tumor measurement (day 22), as described above. We also calculated the rate of increase in tumor volume for each group. These parameters were compared in each pair-wise combination of the three tumor groups. The slope of the increase in log tumor volume with time was not significantly different (i.e. p>0.05), for any pair-wise comparison (Table 1). However, the estimated tumor volume at the mid-point of tumor measurement was significantly different (i.e. p<0.05) between the group not fed doxycycline (group c) and that fed doxycycline throughout the tumor growth period (group a), and also between that fed doxcycyline only between days 7 and 30 (group b) and that fed doxycycline throughout the tumor growth period (group a), but was not significantly different between groups b and c (Table 1). These results indicate that Arnt is required more during the early stages of growth of these tumors than during the later stages.

Table 1.

The rates of increase in tumor volume and the tumor volume at the mid-point of tumor measurements (day 22) was determined as described in “Results.”

| Comparison Groups | p values from tests of :- | |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor volume at mid-point | Slope (log tumor volume against days) |

|

| Dox 0-30 versus no Dox (a versus c) |

0.0004 | 0.12 |

| Dox 0-30 versus Dox 7-30 (a versus b) |

0.011 | 0.10 |

| Dox 7-30 versus no Dox (b versus c) |

0.22 | 0.89 |

Analysis of Tumors

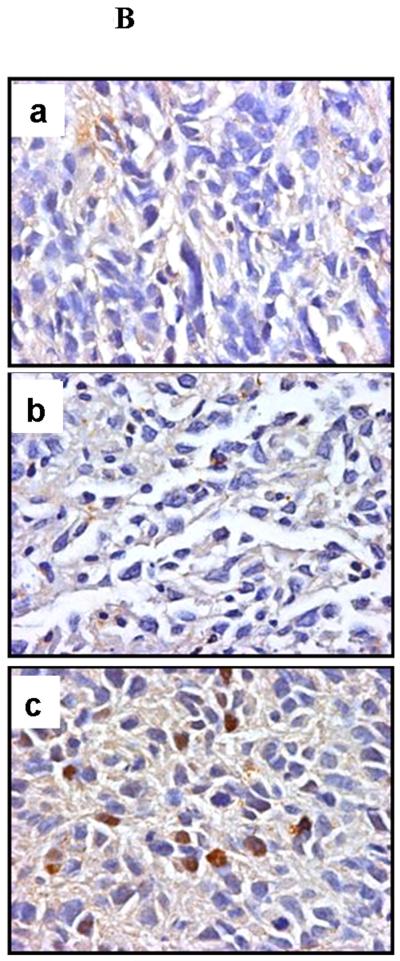

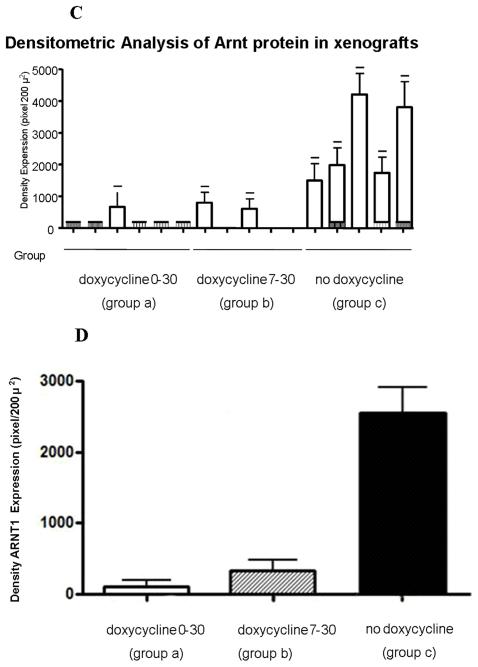

The c4 strain contains a single nucleotide substitution in the coding sequence compared with the wild-type sequence contained in the pRevTRE-mArnt vector. Using one primer with a single mismatch to the wild-type sequence but with two mismatches to the c4 sequence (note that primers with additional mismatches can better discriminate single base pair mutations [19], we established PCR conditions under which the wild-type sequence was amplified with ten-fold greater efficiency than the c4 mutant sequence. Real time PCR analysis using RNA from the tumor samples demonstrated that tumors treated with doxycycline throughout the 30 day period (group a), or from days 7 through 30 (group b), expressed considerably diminished levels of the Arnt transcript derived from the pRevTRE-mArnt vector (Figure 3A), relative to the group not fed doxycycline at all (group c). (Note that some of the signal generated in the first two types of xenograft may be due to amplification of the endogenous c4 Arnt cDNA.) Immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated that the levels of Arnt protein were also much reduced in the two groups fed doxycycline relative to the group not fed doxycycline (Figures 3B, 3C and 3D; note that the c4-derived Arnt protein exhibits enhanced lability), consistent with doxycycline regulation of Arnt expression.

Figure 3.

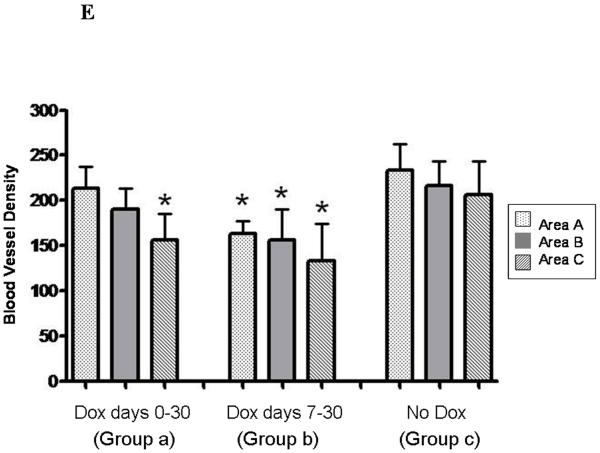

Tumors were immunohistochemically stained for the endothelial marker, CD31, and blood vessel density determined for peripheral (area A), middle (area B), and central (area C) portions of the tumors (Figure 3E). Vessel densities were reduced modestly for one or more portions of tumors derived from both types of doxycycline treatment, and thus blood vessel density did not correlate with magnitude of tumor growth. The degree of tumor necrosis and the proportion of apoptotic cells did not differ between the different types of tumor (data not shown). We also immunohistochemically stained the tumors for Vegf, but did not observe any consistent differences between the three groups with regard to degree of staining of this protein (data not shown). Thus, we did not identify any cellular parameter that could explain the diminution in extent of growth of tumors in animals treated with doxycycline between days 0 and 30. Of course, it is possible that some of the cellular parameters that we studied where diminished during the early growth period of the tumors, and were responsible for retarding tumor growth during this period, but that these parameters recovered during later tumor growth, and by the time we isolated the tumors for analysis.

DISCUSSION

We confirm previous observations that c4 Arnt-deficient cells generate smaller tumors than the Hepa-1 parental cell line [11,21-22]. Our data extend these observation to show (i) that the reduced growth of c4 tumors is mainly due to a requirement for Arnt-dependent processes during the very early stages of tumor expansion, and (ii) that after an initial lag period, the doubling time of c4 tumors is not detectably different from that of Hepa-1 tumors.

Since c4 cells grow at the same rate and achieve the same maximal cell density as Hepa-1 cells when cultured under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions (i.e. with 1% O2 in the atmosphere above the culture medium), the reduced growth of c4 tumors is unlikely to be due to a cell autonomous event (or events), but a consequence of altered interaction(s) between the tumor cells and the host. c4 cells have been shown to be deficient in the hypoxic induction of a number of genes in culture, including Vegf ([9-10]. We hypothesize that Arnt-dependent hypoxic induction of Vegf (or another secreted protein(s)) is required particularly during the early growth of the hepatoma-derived tumors, and its deficiency is at least one of the factors leading to the reduced expansion of c4-derived tumors during these early stages. In apparent conflict with this notion, the Arnt-deficient tumors in the current study did not exhibit a consistent deficiency in Vegf protein expression or vascular density compared with Arnt-proficient tumors. This observation contrasts with what we previously reported, where vascular density and Vegf mRNA expression were reduced in c4 tumors compared with Hepa-1 tumors [11], although it is in agreement with that of Griffiths and coworkers [22], who did not observe reduced vascular density in c4 tumors. A possible explanation for these apparently conflicting observations is that in our previous study the tumors were analyzed when they were considerably smaller than those analyzed in the present study and in the study of Griffiths and coworkers. A possible explanation for the absence of a consistent deficiency in Vegf expression in the Arnt-proficient tumors in the present study is that Vegf expression may recover in larger Arnt-deficient tumors via compensatory up-regulation of other factors that stimulate its expression.

Our observations that Arnt is particularly required early during tumor growth is consistent with experimental observations on certain other tumor types indicating that loss of either Vegf or HIF-1α more adversely affects early tumor growth than later tumor growth [23-24], and is also consistent with observations that very small tumors, but not larger tumors, are generally hypoxic [25].

As mentioned earlier, the great majority of studies indicate that like Arnt, HIF-1α represents a positive factor for tumor growth [12-14]. As a consequence, there is considerable effort in both academia and the pharmaceutical industry to develop HIF-1 inhibitors for the treatment of cancer [14]. However, Arnt may represent a better therapeutic target than HIF-1α for certain tumors, for several reasons. (i) Many cancer cell lines and most tumors express both HIF-1α and HIF-2α [26-27]. It may be necessary therefore to inhibit both subunits. Although information on Arnt and Arnt2 is less extensive, the expression of the latter is restricted to only certain tissues, and in order to inhibit HIF-1 in many cancers, it may therefore be sufficient to inhibit only Arnt. (ii) Arnt appears to act as a potent coactivator of estrogen receptor signaling [28] and negation of Arnt inhibits the response to estrogen receptor ligands as well as hypoxia [29]. Such an effect would be beneficial in certain female cancers. (iii) Arnt, via its interaction with AhR, mediates the genotoxic and non-genotoxic effects of a wide variety of environmental carcinogens [30]. Tumor cells in which Arnt activity is inhibited would be resistant to any stimulation of tumor progression elicited by these compounds.

Finally, our studies suggest that Arnt (and HIF-1α/ HIF-2α) inhibitors will be effective against small (but not well established) tumors, and would therefore be particularly useful in targeting micrometastases. However, our studies also indicate that such inhibitors would likely retard, but not completely eliminate such tumors, suggesting that Arnt (and HIF-1α/ HIF-2α) inhibitors might not be effective on their own, but would have to be used in conjunction with therapeutic drugs with different mechanisms of action.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funded by grant RO1 CA93471, an underrepresented minority supplement (K.H.-B.) to RO1 CA93471, and RO1 CA28868

REFERENCES

- 1.Gordan JD, Simon MC. Hypoxia-inducible factors: central regulators of the tumor phenotype. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17(1):71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirose K, Morita M, Ema M, et al. cDNA cloning and tissue-specific expression of a novel basic helix-loop-helix/PAS factor (Arnt2) with close sequence similarity to the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (Arnt) Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16(4):1706–1713. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drutel G, Kathmann M, Heron A, Schwartz JC, Arrang JM. Cloning and selective expression in brain and kidney of ARNT2 homologous to the Ah receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT) Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;225(2):333–339. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lofstedt T, Fredlund E, Holmquist-Mengelbier L, et al. Hypoxia inducible factor-2alpha in cancer. Cell Cycle. 2007;6(8):919–926. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.8.4133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Legraverend C, Hannah RR, Eisen HJ, Owens IS, Nebert DW, Hankinson O. Regulatory gene product of the Ah locus. Characterization of receptor mutants among mouse hepatoma clones. J Biol Chem. 1982;257(11):6402–6407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Numayama-Tsuruta K, Kobayashi A, Sogawa K, Fujii-Kuriyama Y. A point mutation responsible for defective function of the aryl-hydrocarbon-receptor nuclear translocator in mutant Hepa-1c1c7 cells. Eur J Biochem. 1997;246(2):486–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dougherty EJ, Pollenz RS. Analysis of Ah receptor-ARNT and Ah receptor-ARNT2 complexes in vitro and in cell culture. Toxicol Sci. 2008;103(1):191–206. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang GL, Jiang BH, Rue EA, Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(12):5510–5514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wood SM, Gleadle JM, Pugh CW, Hankinson O, Ratcliffe PJ. The role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT) in hypoxic induction of gene expression. Studies in ARNT-deficient cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(25):15117–15123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.25.15117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forsythe JA, Jiang BH, Iyer NV, et al. Activation of vascular endothelial growth factor gene transcription by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16(9):4604–4613. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maxwell PH, Dachs GU, Gleadle JM, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 modulates gene expression in solid tumors and influences both angiogenesis and tumor growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(15):8104–8109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.8104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liao D, Johnson RS. Hypoxia: a key regulator of angiogenesis in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26(2):281–290. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9066-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maxwell PH. The HIF pathway in cancer. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16(4-5):523–530. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Semenza GL. Development of novel therapeutic strategies that target HIF-1. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2006;10(2):267–280. doi: 10.1517/14728222.10.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Gurp JR, Hankinson O. Isolation and characterization of revertants from four different classes of aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase-deficient hepa-1 mutants. Mol Cell Biol. 1984;4(8):1597–1604. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.8.1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hankinson O. Single-step selection of clones of a mouse hepatoma line deficient in aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76(1):373–376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.1.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Streit M, Velasco P, Brown LF, et al. Overexpression of thrombospondin-1 decreases angiogenesis and inhibits the growth of human cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas. Am J Pathol. 1999;155(2):441–452. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65140-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Probst MR, Reisz-Porszasz S, Agbunag RV, Ong MS, Hankinson O. Role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator protein in aryl hydrocarbon (dioxin) receptor action. Mol Pharmacol. 1993;44(3):511–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta M, Song P, Yates CR, Meibohm B. Real-time PCR-based genotyping assay for CXCR2 polymorphisms. Clin Chim Acta. 2004;341(1-2):93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beedanagari SR, Bebenek I, Bui P, Hankinson O. Resveratrol inhibits dioxin-induced expression of human CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 by inhibiting recruitment of the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor complex and RNA Polymerase II to the regulatory regions of the corresponding genes. Toxicol Sci. 2009 doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hopfl G, Wenger RH, Ziegler U, et al. Rescue of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha-deficient tumor growth by wild-type cells is independent of vascular endothelial growth factor. Cancer Res. 2002;62(10):2962–2970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griffiths JR, McSheehy PM, Robinson SP, et al. Metabolic changes detected by in vivo magnetic resonance studies of HEPA-1 wild-type tumors and tumors deficient in hypoxia-inducible factor-1beta (HIF-1beta): evidence of an anabolic role for the HIF-1 pathway. Cancer Res. 2002;62(3):688–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoshiji H, Harris SR, Thorgeirsson UP. Vascular endothelial growth factor is essential for initial but not continued in vivo growth of human breast carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 1997;57(18):3924–3928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li L, Lin X, Staver M, et al. Evaluating hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha as a cancer therapeutic target via inducible RNA interference in vivo. Cancer Res. 2005;65(16):7249–7258. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li XF, Carlin S, Urano M, Russell J, Ling CC, O’Donoghue JA. Visualization of hypoxia in microscopic tumors by immunofluorescent microscopy. Cancer Res. 2007;67(16):7646–7653. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiesener MS, Turley H, Allen WE, et al. Induction of endothelial PAS domain protein-1 by hypoxia: characterization and comparison with hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha. Blood. 1998;92(7):2260–2268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Talks KL, Turley H, Gatter KC, et al. The expression and distribution of the hypoxia-inducible factors HIF-1alpha and HIF-2alpha in normal human tissues, cancers, and tumor-associated macrophages. Am J Pathol. 2000;157(2):411–421. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64554-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brunnberg S, Pettersson K, Rydin E, Matthews J, Hanberg A, Pongratz I. The basic helix-loop-helix-PAS protein ARNT functions as a potent coactivator of estrogen receptor-dependent transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(11):6517–6522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1136688100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jensen KA, Luu TC, Chan WK. A truncated Ah receptor blocks the hypoxia and estrogen receptor signaling pathways: a viable approach for breast cancer treatment. Mol Pharm. 2006;3(6):695–703. doi: 10.1021/mp0600438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hankinson O. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor complex. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1995;35:307–340. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.35.040195.001515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.