Abstract

Objective:

To create a mechanism in British Columbia (BC) for youth and families to directly engage with key provincial committees that develop policy and implement service delivery for child and youth mental health.

Method:

In 2009, a plan was initiated to increase the involvement and influence of youth and families in research, policy, practices and programs related to child and youth mental health. This initiative, led by a provincial family advocacy society in partnership with representatives from health services and government, resulted in the establishment of the Provincial Family Council for Child and Youth Mental Health (PFC). Formation of the PFC occurred in two phases: initially, a Working Group co-chaired by a parent and a youth was tasked with developing the Terms of Reference and framework for the PFC; phase two involved ensuring important constituencies/demographics and competencies were represented in the membership of the PFC. Result: The Provincial Family Council is officially endorsed by the provincial government and is informing key provincial committees in British Columbia.

Conclusion:

In BC, the PFC is the vehicle through which youth and families can now work in partnership with “the system” to promote and improve the mental health of BC’s children and youth.

Keywords: early intervention, parenting, partnerships, family engagement

Résumé

Objectif:

Créer, en Colombie-britannique, un mécanisme de participation directe des adolescents et de leur famille aux principaux comités provinciaux qui établissent les politiques et appliquent les mesures relatives aux soins de santé mentale aux enfants et aux adolescents.

Méthodologie:

Le plan a été mis en place en 2009 pour tirer profit de la participation des adolescents et de leur famille à la recherche, à la politique, aux pratiques et aux programmes de santé mentale des enfants et des adolescents, et pour influer sur ces deivers éléments. Dirigée par une société provinciale de défense de la famille, cette initiative entre dans le cadre d’un partenariat avec des représentants des services de santé et du gouvernement. Elle a débouché sur la création du Conseil provincial de la famille – santé mentale de l’enfant et de l’adolescent (Provincial Family Council for Child and Youth Mental Health - PFC). Ce Conseil a été formé en deux étapes ; dans un premier temps un groupe de travail présidé par un parent et par un adolescent a défini le mandat et le cadre du Conseil; dans un deuxième temps on s’est assuré que le Conseil comptait parmi ses membres des représentants de la communauté et des divers groupes socio-économiques, et qu’il regroupait les compétences recherchées.

Résultat:

Le Conseil provincial de la famille reçoit l’appui officiel du gouvernement provincial et influence les principaux comités provinciaux de Colombie-britannique.

Conclusion:

En Colombie-britannique, le Conseil provincial de la famille est l’organisme qui permet aux adolescents et à leur famille de travailler en partenariat avec le système de santé à la promotion et à l’amélioration de la santé mentale des enfants et des adolescents de cette province.

Keywords: intervention précoce, rôle des parents, partenariat, engagement de la famille

Introduction

Some of the background information provided below is abstracted from an unpublished literature review of best, emerging and promising practices of family engagement in child and youth mental health completed by The Families Organized for Care Recognition and Equality Society for Kid’s Mental Health (The FORCE) to support this initiative and is reprinted with permission (Chovil, N., Engaging Families in Child & Youth Mental Health: A Review of Best, Emerging and Promising Practices, for The F.O.R.C.E. Society for Kids’ Mental Health, April, 2009).

The Need for a New Approach

The gap between the need and availability of child and youth mental health services in Canada is well known. The incidence of diagnosable psychiatric disorders in Canadian children and youth is 15% (Waddell & Shepherd, 2002), and as such, roughly two million Canadian children and youth struggle significantly with their ability to learn, make friends, participate in activities and function in their families as the result of a psychiatric disorder. This translates to four to five children/youth in every classroom of thirty; an incidence expected to increase by 50 percent over the next ten years (WHO, 2004). At least 3 out of 5 children and youth with mental health challenges do not receive mental health services—approximately 1.2 million children and youth in Canada (Waddell et al. 2002). In 2006, then Senator Michael Kirby stated that “the greatest omission in the work that I see is that it fails to stress the reality that most of the mental health disorders affecting Canadians today begin in childhood and adolescence. Failure to recognize this fact leads us to dealing with a stage-four cancer, often with major secondary effects, instead of a stage-one or stage-two disease. Like obesity, mental health issues, if not addressed early in life, threaten to bankrupt our health care system” (Kirby & Keon, 2006).

There is clearly a pressing need to improve our ability to promote mental health, prevent mental health problems, and effectively treat mental disorders in children and youth in Canada. Families are uniquely positioned to contribute to increasing the capacity of the mental health system of care through collaboration with service providers, policy makers and other families based on their personal experiences and their motivation to improve outcomes for their own children and youth. Most professionals working in the formal system of care have yet to fully recognize the benefits of actively engaging families as a way of developing system capacity and improving the quality of care. This potential deserves consideration and implementation.

Family Engagement

The family is a foundational institution across cultures; core similarities exist in a context of culturally defined configurations that continue to evolve in a rapidly changing world. As such, the responsibility for children’s physical, mental, emotional and spiritual development is generally entrusted to their families. It is not surprising therefore that when children and youth with mental health challenges enter treatment, family engagement positively influences the outcome (Kutash & Rivera, 1995; Pfeifer & Strzelecki, 1990) and empowers families to continue to nurture their child’s development while attending to their specialized needs (Osher, 2001).

As noted by the New York State Council on Children and Families (2008), family engagement can be defined as “any role or activity that enables families to have direct and meaningful input into and influence on systems, policies, programs, or practices affecting services for children and families.” A fully engaged family is motivated and empowered to recognize their own needs, strengths and resources and is prepared to take an active role in changing things for the better over the “often long and sometimes slow process of positive change” (Steib, 2004).

Evidence suggests that families are more likely to feel their child’s needs were met when they are able to participate in service planning (Koren et al., 1997), and to experience having more control over their child’s treatment when they are able to participate in their child’s care (Curtis & Singh, 1996; Thompson et al., 1997). In a state initiated review, the Virginia Commission on Youth (2003) identified a number of benefits related to family engagement including: an increased focus on the family’s role in treatment and recovery; more flexible delivery of services; greater cultural sensitivity; and improved service coordination, processes and outcomes.

Organizations such as the National Federation of Families for Children’s Mental Health in the United States represent a powerful movement influencing the provision of services for families with a child or youth with mental health issues. In the US, the benefits of family engagement are more widely recognized and child and youth mental health is undergoing a transformation, moving towards a system of care which integrates family involvement (Tannen, 1996; Hoagwood et al., 2010).

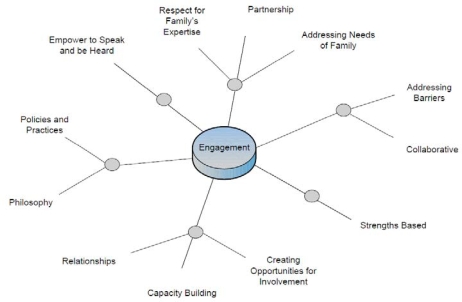

Figure 1 (adapted from Chovil, 2009) summarizes the many facets of full family engagement across the spectrum of care in child and youth mental health from promotion and prevention to intervention and treatment.

Figure 1.

Elements of Family Engagement (Adapted with permission from Chovil, 2009)

Subsequent to the implementation of the 2003 Child and Youth Mental Health Plan, a review of child and youth mental health services in BC, Berland (2008) recommended that “there should be a commitment to embed client and family perspectives and resources into the infrastructure both regionally and provincially, with a policy on expectations of family advisory committees at the regional and sub-regional level.”

In March 2009, The FORCE, a parent advocacy society established in 2000 to help families in British Columbia address their child or youth’s mental health issues, followed the lead of the National Federation of Families for Children’s Mental Health in the United States and took action related to Berland’s (2008) recommendations.

A representative of The FORCE approached key BC government and health services stakeholders and determined there was shared interest in developing mechanisms to facilitate the integration of British Columbian families’ perspectives to further improve mental health promotion and child and youth mental health care in BC. This partnership led to the creation of the Provincial Family Council (PFC) for Child and Youth Mental Health.

Methods

Increasing Family Engagement in British Columbia—Developing the Provincial Family Council for Child and Youth Mental Health

An advisory team was formed to assist in the development of this initiative and included representatives from The FORCE, BC Mental Health & Addiction Services and the Ministry of Children & Family Development.

The establishment of the Provincial Family Council occurred in two phases: An initial Working Group was tasked with developing the Terms of Reference and Framework for the PFC; the second phase involved identifying membership for the Provincial Family Council, ensuring that key constituencies/demographics and competencies identified by the Working Group were represented on the PFC.

For the purposes of this initiative family was defined as including both biological and non-biological members, encompassing children, youth, parents, grandparents, siblings, guardians, foster parents, extended family caregivers and youth who may have no family ties, biological or otherwise, for both the Working Group and the PFC.

Phase 1: The Working Group

A parent and youth were appointed to co-chair the Working Group with the assistance of the advisory team.

Call of Interest

A Call of Interest for the Working Group seeking youth and family/caregiver representation from across BC was released on July 22, 2009. Through the Call, the co-chairs sought to include various perspectives and voices, for example, in relation to family role, age, gender, ethno cultural background, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status and geographic location.

Forming the Working Group

From the 22 people who responded to the Call of Interest, 10 were short-listed and interviewed by the co-chairs of the Working Group. The individuals selected for the Working Group included three youth (ages 17—25) and five adults in addition to the co-chairs. Three provincial leaders from BC Mental Health & Addiction Services (BCMHAS), the Ministry of Children and Family Development (MCFD), and the Ministry of Health Services were also invited to participate as members of the Working Group.

In September 2009, the newly-formed Working Group was tasked with developing a framework for the creation of the Provincial Family Council (PFC). During a two-day orientation session, the group clarified their vision and developed a six month action plan that included priorities such as drafting a Terms of Reference, developing a financial plan, identifying PFC membership constituencies/demographics and competencies, and identifying key opportunities for family-system linkages.

BCMHAS provided seed funding to support the Working Group which facilitated both the two day orientation and the group meeting on a monthly basis through its six month tenure. These full day meetings were held on weekends to facilitate attendance by all members. The successful functioning of the working group was supported by common goals and a shared experience characterized by trust, equality, understanding and respect.

Phase 2: The Provincial Family Council for Child and Youth Mental Health

In May 2010, the BC Provincial Family Council for Child and Youth Mental Health was officially formed. To provide continuity, several members of the Working Group will stand as members on the PFC for one to two years, while additional members were identified through a Call of Interest. Seed funding provided by BCMHAS and MCFD, two key service providers with responsibility for child and youth mental health services in BC, will provide initial support for the work of the PFC.

Results

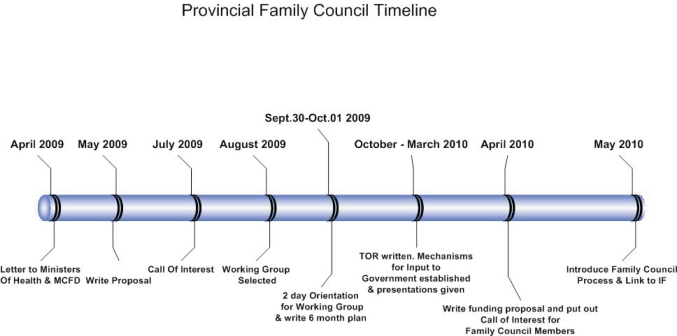

The experiences and lessons learned by the Working Group have the potential to support similar initiatives in other provinces or territories that are interested in creating a formal mechanism for family engagement in child and youth mental health. As highlighted in Figure 2, moving from concept to formation of a council is achievable in a relatively short period of time.

Figure 2.

The timeline for the establishment of the BC Provincial Family Council - moving from concept to reality in twelve months.

Lessons Learned from the Working Group

The successful experience of the Working Group was based on a number of elements:

Equality: All members of the Working Group were acknowledged as experts and equal participants in the group process. This facilitated trust and engagement within the group. In particular, the youth members expressed feeling valued due to their sense of being treated as equals.

Diversity: Varying experiences and perspectives increased the depth and wisdom of the group. There is great benefit in bringing parents and youth together with systems representatives. This facilitated a radical shift in perceptions that some individuals expressed having had about each other and strengthened the ability to work together, reflecting the foundational desired outcome of the Provincial Family Council.

Commitment: The commitment of individual members was supported by the dedication and momentum of the group. This was very important since some members faced periodic challenges. Their continued participation was facilitated by the acceptance and support of their colleagues as well as their recognition that the Working Group was continuing to make progress.

System Representation: It was critically important to have appropriately positioned system representatives as part of the Working Group to facilitate linkages to key committees and to support commitment from the formal mental health system.

Flexibility: Some members were not able to follow through to complete tasks that they had agreed to. This should be expected and accepted. The group needed to be flexible with expectations for participation given the unforeseen challenges that some individual members experienced. This is also an important point to consider in selection of members as youth and family members in crisis may not be in a position to contribute the required time or commitment needed to successfully participate in the Council.

Support for Youth: Youth members sometimes needed practical supports to enable them to participate fully. This included transportation, access to the internet, coaching to prepare for presentations and information—for example about system structures, government processes, etc. The youth were hard to find and it took several rounds of calls to parents and people working with youth to disseminate the Call of Interest with the youth and to support them to consider participating.

Administrative Support: A designated lead was required to facilitate the development of the group, handle administration and follow-up with group members to keep things moving and ensure that identified actions were completed. In addition, a core group of adults was required to manage the workload in the early stages of group formation.

Acknowledgment of Progress: The process of working together was very rewarding for everyone and appeared to build confidence and capacity in members, particularly the youth. It was important to take time to acknowledge the progress made by the group and to celebrate their hard work.

Allowing Time to Build System Linkages: It took time to share the vision of the Provincial Family Council with others within the broad mental health system; however this was essential to ensure support and engagement across the system. Having youth and family members of the Working Group present the information at key committee meetings was an effective dissemination strategy.

Members report that participating in the Working Group was a transformative experience.

“It was a life-changing experience,” said one member, whose son has mental health challenges. “Listening to others; including those working in the system, completely flipped around my point of view. Change won’t happen for my son, but maybe it will for his son.”

A youth in the group stated “I don’t want anyone to go through what I went through. I want my kids to have a better system. I believe being part of the Working Group was an important step in that direction.”

“Being a part of the family council has been a unique experience, not like the other committees I’ve been on,” said another youth member of the Working Group. “This is a group with a purpose—to improve the experience families have when dealing with child and youth mental health issues. Whether it’s opening up the dialogue, informing politicians or educating the public, we are making a difference. It’s exciting to know that progress is being made, since so many things we do have never been done before. I know my involvement is worth my time.”

One systems representative shared “When I think of the expectations and anxieties I had before participating as a member on this working group, and how much that experience has given to me personally, and informed my practice, I can’t imagine doing what I do without having had that experience . . . I am not anxious any-more to speak with youth and family members about what they need and how we can work together and I appreciate profoundly the untapped wisdom and capacities that youth and family members carry with them.”

Establishing the Provincial Family Council

Formation of the Provincial Family Council was announced on May 7th, 2010, National Child and Youth Mental Health Day. This was officially endorsed by the provincial government after which the inaugural members of the PFC were introduced.

The Provincial Family Council membership reflects “family” as defined and includes youth and other family members who have varied lived experiences related to mental health challenges, as well as connections, affiliations and skills that support their participation and enrich their knowledge and function of the PFC. Emphasis was placed on proactively recruiting members who represent the diversity of children, youth and families in BC who have, or may have, their mental health compromised.

The Provincial Family Council’s main function is to serve as the primary provincial resource in BC to contribute family perspectives and advice related to child and youth mental health regarding:

Innovative ways of addressing problems and issues that will support improvements.

Key issues/priorities/opportunities that are meaningful to children, youth, families and communities of care.

Ways in which policies and practices in service delivery can be enhanced to improve family experiences and outcomes.

Training and evaluation practices.

Approaches to improving family engagement.

Evaluation of the influence of PFC on systems.

These functions will be facilitated through representation of the PFC on key policy & planning and service delivery committees in BC including: the Child and Youth Mental Health and Substance Use Strategic Coordinating Committee; the BC Children’s Hospital Child and Adolescent Mental Health and Addiction Programs Community Advisory Committee; and, the Provincial Child and Youth Mental Health and Substance Use Care Advisory Network.

Conclusion

The desired outcome in establishing the Provincial Family Council in BC is to ensure effective mechanisms for dialogue and collaboration between families, service providers and policy makers, leading to increased understanding and cooperation between families and professionals and more effective and efficient planning to ensure that services meet family needs and priorities. The goal of the proposed Provincial Family Council is to support families to contribute to the design of policies, programs and practices to improve the mental health of all children, youth and their families in BC. The PFC will work toward developing a perspective where families are recognized as allies in the delivery of quality mental health promotion, prevention and care. In this approach, individual families are also valued as consistent advocates for their children and youth, particularly across key transitions, for example from childhood to adulthood or from tertiary services to community services.

The foundation is now in place, however the continued support of the provincial government—including key stakeholders in BC Mental Health & Addictions Services and the Ministry of Children and Family Development is essential to the future success of the Provincial Family Council.

Next Steps

In determining the most effective structure to support the family council and promote dissemination of the model in provinces and territories in Canada, the working group made the decision to become an affiliate of the National Institute of Families Foundation for Child and Youth Mental Health (the IF).

The newly launched Institute of Families is an independent, non-profit, national coordinating organization that will link health providers, policy makers, educators and researchers with families across Canada. The IF will provide families with formalized opportunities to access and engage with systems that support child and youth mental health in Canada. Using the collective expertise of its’ network, the IF will define, organize and mobilize the voice of families across Canada.

Nine key initiatives have been established for the IF:

Establishing annual recognition of National Child and Youth Mental Health Day on May 7th to help create public awareness and acknowledgement for the thousands of children, youth and families needing mental health support and care across Canada.

Supporting the development of Provincial/Territorial Family Councils in each province/territory in Canada.

Developing opportunities for recognizing and reducing the stigma associated with child and youth mental health issues.

Securing the “Family Smart™” trademark to identify evidence-based programs, policies and practices that are ‘family friendly,’ based on criteria determined by families.

Providing leadership and consultation about ways of engaging families to develop measures and outcomes that are meaningful to them. This includes increasing the inclusion of family perspectives in research, policies, practices and service planning.

Developing a Parent University to enhance the ability of parents and prospective parents to understand and support their child’s mental health.

Creating a library hub for leading practices, evidence-informed and “Family Smart™” programs across the continuum of child and youth mental health. This virtual reference library will provide access to leading evidence-informed programs and care pathways focused on prevention, promotion and early identification and intervention related to child and youth mental health. It will also provide expertise, information and support to provincial stakeholders in order to encourage the engagement of families in each province and territory.

Developing stakeholder engagement strategies to raise the profile of the Institute and to encourage families and systems to engage collaboratively.

A planning committee is currently under development to further define and build the infrastructure, governance model and long-term goals and objectives for the IF.

The establishment of the Provincial Family Council and the National Institute of Families for Child and Youth Mental Health are significant steps forward in engaging families more formally in mental health care and system improvement in Canada. The IF will play an important national coordinating role while the Provincial Family Council will actively seek opportunities for families to participate as partners in the planning, policy, research and delivery of mental health services for children and youth provincially in BC.

The hope is that Provincial/Territorial Family Councils will be established in other provinces and territories and be connected and coordinated through the IF. The lessons learned in BC will help streamline these processes and the BC Provincial Family Council is developing a written template and video that will support these efforts.

Change must take place at both the systems level and the practice level. At the systems level, the BC Provincial Family Council will lead efforts to build bridges between families and mental health services and systems. At the practice level, many clinicians already work actively with families as part of the therapeutic relationship, and it is expected that these practices will be further facilitated through regular contributions from families to improve approaches to family engagement.

The focus now must be on broadening an understanding of the capacity of families to contribute, the benefits of their direct involvement and ways their engagement can be incorporated into everyday practice and system structures. By recognizing the potential for families to contribute to improvements in child and youth mental health care and welcoming the participation of families, all stakeholders can embrace an urgently needed, and novel approach.

Acknowledgements/Conflict of Interest

The authors would like to acknowledge BC Mental Health and Addiction Services for the provision of seed funding for the Working Group and the Provincial Family Council and the Ministry of Children and Family Development for the provision of seed funding for the Provincial Family Council. Jana Davidson and Keli Anderson are Founding Directors of the National Institute of Families for Child and Youth Mental Health.

References

- Curtis IW, Singh NN. Family involvement and empowerment in mental health service provision for children with emotional and behavioral disorders. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1996;5:503–517. [Google Scholar]

- Hoagwood KE, Cavaleri MA, Olin SS, Burns BJ, Slaton E, Gruttadaro D, Hughes R. Family Support in Children’s Mental Health: A Review and Synthesis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2010;13:1–45. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby MJL, Keon WJ. Out of the shadows at last. Transforming mental health, mental illness and addictions services in Canada. Final Report of The Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Koren PE, Paulson RI, Yatchmonoff D, Gordon L, DeChillo N. Service coordination in children’s mental health: An empirical study from the caregiver’s perspective. Journal of Emotional & Behavioral Disorders. 1997;5(3):162–173. [Google Scholar]

- Kutash K, Rivera VR. Effectiveness of children’s mental health services: A review of the literature. Education and Treatment of Children. 1995;18:443–477. [Google Scholar]

- New York State. Council on Children and Families A definition of Family Involvement. 2008. http://www.ccf.state.ny.us/Initiatives/CCSIRelate/CCSIFamInvolv.htm#definition.

- Osher TW. Family participation in evaluating systems of care: family, research, and service system. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2001;9:6271. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer SI, Strzelecki SC. Inpatient psychiatric treatment of children and adolescents: A review of outcome studies. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1990;29:847–53. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199011000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannen N. National Technical Assistance Centre for Children’s Mental Health. Washington DC: 1996. Families at the Centre of the Development of a System of Care. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson L, Lobb C, Elling R, Herman S, Jurkidwewicz T, Helluza C. Pathways to family empowerment: Effects of family-centered delivery of early intervention services. Exceptional Children. 1997;64:99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Virginia Commission on Youth Key Components of Successful Treatment Programs. Collection of Evidence-Based Treatment Modalities For Children and Adolescents with Mental Health Treatment Needs. 2003. http://coy.state.va.us/Modalities/contents.htm.

- Waddell C, Shepherd C. Prevalence of Mental Disorders in Children and Youth. A Research Update Prepared for the British Columbia Ministry of Children and Family Development. Mental Health Evaluation & Community Consultation Unit, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, The University of British Columbia 2002 [Google Scholar]

- Waddell C, McEwan K, Hua J, Shepherd C. Child and Youth Mental Health: Population Health and Clinical Service Considerations A Research Report Prepared for the British Columbia Ministry of Children and Family Development Mental Health Evaluation & Community Consultation Unit, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine. The University of British Columbia. 2002.

- World Health Organization Prevention and Promotion in Mental Health. Mental Health Evidence and Research, Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence, WHO 2004 [Google Scholar]