SUMMARY

This article presents a summary history and context of the CHAMP Family Program. Primarily, CHAMP was created and developed in response to rising levels of HIV and AIDS in inner-city communities of color. Concurrently, major changes in the field of psychology were underway during the late 1980s and early 1990s including new perceptions of the effect of culture and context on development; the birth of development psychopathology as a field; and increasing interest in–and recognition of—adolescent psychology. It is within the context of these transformations that this article places the design and implementation of CHAMP. The evolution of the CHAMP Family Program a relatively small, cyclical study in Chicago, to a major, multi-site project is discussed, with particular emphasis on the role of community collaboration in the transitions that CHAMP has experienced thus far.

Keywords: Community collaborative partnerships, culture, context, adolescent psychology, family-based intervention, HIV-prevention

Adolescents are among the fastest growing population at risk for HIV/AIDS (Centers for Disease Control, 2003; 2000; 1998). Females and minority youth are disproportionately affected by STDs and the AIDS epidemic (Centers for Disease Control, 2001; 2003; DiLorenzo & Hein, 1993; Jemmott & Jemmott, 1992; 1998). Over the last decade, the incidence of HIV and AIDS infection has risen dramatically in low income, minority neighborhoods. African American and Latino youth are over represented among those living in poor neighborhoods with increased likelihood of exposure to HIV due to higher overall rates of neighborhood prevalence, along with poorer access to preventive health care, early detection and treatment services (Rotheram-Borus, Mahler & Rosario, 1995).

Prevention scientists have developed and tested a number of sexual risk reduction and STD or HIV prevention programs targeting urban minority youth. However, efforts to transport empirically supported prevention programs have encountered numerous obstacles, including insufficient school-based resources, poor community participation or tensions and suspicions between community residents and outside researchers (Dalton, 1989; Galbraith, Stanton, Feigelman, Ricardo, Black & Kalijee, 1996; Thomas & Quinn, 1991). As a result, it is becoming clear that community-based prevention programs targeting urban minority youth are likely to fail if they attempt to provide interventions in a non-collaborative manner (Aponte, 1988; Boyd-Franklin, 1993; Fullilove & Fullilove, 1993) or neglect to design and implement programs which do not appreciate stressors, scarce contextual resources or target groups’ core values (Boyd-Franklin, 1993), Therefore, two steps are necessary to increase chances of success of HIV prevention efforts focused on urban youth. First, the establishment of strong community partnerships to support youth health prevention efforts is critical so that effective adolescent sexual risk prevention programs will be well received within urban communities. Second, any preventatively oriented program has increased chances for effectiveness if it is devised based upon empirical findings drawn directly from youth living in targeted communities.

Thus, the CHAMP (Collaborative HIV prevention and Adolescent Mental health Project; Paikoff, McKay & Bell, 1994; McKay, Paikoff, Bell, Madison & Baptiste, 2000) Family Program has been designed with these two steps as its foundation across national and international sites. More specifically, community collaborative research principles have guided the design, delivery and testing of the family-based HIV preventative intervention. In addition, the program has been continually informed by empirical findings derived directly from inner-city youth and their families living within target CHAMP communities. CHAMP focuses on building the capacities of community members to deliver a family-based HIV prevention program targeting preadolescent youth and their families living within inner-city U.S. communities and within countries hardest hit by the HIV/AIDS epidemic. The CHAMP Collaborative Board, consisting of urban parents, school staff, representatives from community-based organization and university-based researchers ensures that key stakeholders in the community are involved in every step of the research process, thereby, building further capacity for future prevention research oriented collaborations and community-level leadership. The CHAMP Collaborative Board oversees all aspects of the research project, including design and implementation of the intervention and evaluation of outcomes.

Further, the CHAMP Family Program is also informed by a developmentally grounded theoretical model of youth sexual risk taking that incorporates an understanding of multiple influences at the level of the child, peer group, family and community that impact initiation of youth sexual activity and risk behavior. Empirical findings identifying salient risk and protective factors related to youth sexual health protective behaviors and sexual risk taking informed the content, format and evaluation of the CHAMP Family Program. In this volume, seventeen articles overview the CHAMP program of research. The current chapter, written by Dr. Roberta Paikoff sets the stage for understanding the CHAMP program by providing a “History of Us: CHAMP, Moving from Chicago to Collaborative.” It is the intention of the authors to provide an overview of the transition of the program over the years of its development. Next, Drs. Tolou-Shams, Piakoff, McKirnan and Holbeck report on key findings from basic research that, inform some of the targets of the CHAMP Family Program. Findings related to mental health, youth sexual activity, racial socialization parenting practices, family communication about sensitive topics and social support are summarized by the next four articles. In the next three articles we describe mechanisms, motivators, and challenges to involving urban parents as collaborators in university based HIV prevention research efforts. The volume concludes with five articles addressing the translation of the CHAMP Family Program into a community operated intervention. The first of these five articles details the specific challenges and benefits that CHAMP experienced in the process of its move from a university lab to a community mental health agency. Secondly, Dr. Kerkorian contextualizes community experiences and perceptions of HIV prevention efforts, drawing on a study entitled Knowledge of the African American Research Experience (KAARE). The authors of “Voices from the Community” distill the ten most, essential ingredients necessary for successful community collaboration. Dr. Baptiste follows with a discussion of an international Family-Based HIV/AIDS prevention intervention, working with teens in Trinidad and Tobago. Finally, Dr. McKay and her co-authors conclude with a discussion of the adaptation of family-based HIV Prevention programs for HIV pre-adolescents and their families. Dr. Kerkorian follows with an article about parent’s experiences and motivation for allowing their children to participate in research studies like CHAMP. The volume concludes with three articles addressing the translation of the CHAMP Family Program into a community operated intervention, an intervention that can be used internationally, and an intervention that can be used with HIV+ youth. In the next article, Dr. Bell provides a commentary on using the Triadic Theory of Influence as a guide for adapting collaborative HIV prevention programs for new contexts and populations.

In order to interpret the findings of the CHAMP Family Program and to understand the mechanisms of collaboration and translation, it is necessary to provide the reader with a description of how the program came into existence, why it was developed, key intervention variables and essential modes of service delivery. The history of CHAMP (Collaborative HIV prevention and Adolescent Mental health Project) had its humble beginnings in three tiny cramped offices on the third floor of the old (now defunct) Institute for Juvenile Research, and a one bedroom apartment in the Lincoln Park neighborhood of Chicago. From these two venues, many dedicated collaborators, students and staff worked to bring together the ideas which shaped two parallel lines of study: A basic longitudinal study focused on developmental process, and a family-based preventative intervention based on findings from the longitudinal study. These lines of inquiry were influenced by the authors training and experiences, as well as some of the scientific trends in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Changes in prevailing views of three areas in developmental psychology-were of particular importance to the design and early approaches of CHAMP: (1) the role of culture/context in development, the importance of within sub-group variation, and the study of mechanisms toward adaptation within a subculture; (2) the promise of the newly developing fields of applied developmental psychology and developmental psychopathology; and (3) the growth in recognition of adolescent developmental psychology.

ROLE OF CULTURE AND CONTEXT

The recognition of the importance of culture within development had been recognized for some time, but was just beginning to be applied to diverse cultures within the United States. While prior applications of diversity in development had focused on evaluation of development relative to a particular standard (for the most part, white, male, middle class, and, two parent nuclear family structures), newer approaches emphasized the importance of looking within a particular subgroup for the important variations and predictive value of differences in development. A number of influential scientists (Spencer & Dornbusch, 1990; McLloyd, 1990) had written extensively about the importance of evaluating minority and other diverse subgroups separately as subpopulations in order to determine the relative importance of particular developmental processes and factors in determining adaptive outcomes.

In order to study developmental processes within the context of particular subgroups, additional theoretical models were needed and derived. In particular, numerous theoretical models focused on the perspective of risk and protective factors (Garmezy 1993a; 1993b; Cicchetti & Garmezy 1993; Masten 2003; 2000). From this perspective, examinations of subgroups of children and adolescents could be undertaken with particular hypotheses about the effects of social, cognitive, biological, or mental health aspects of development that might yield different links between process and outcome, allowing for the possibility that factors which would affect some subgroups of youth negatively, might, in fact, have positive effects on other youth. Perhaps the most well-known of these studies is the Steinberg and colleagues (1992) study examining parenting styles among diverse groups of youth, and finding that authoritarian parenting, while less effective than authoritative parenting for White youth, was actually more effective in contributing to achievement levels among other youth (Asians and African Americans). The difference between these studies was primarily along the lines of interpretation: whereas prior studies might have focused on the important differences between groups in terms of pathology or health, these studies focused on important links within subgroups, allowing for the possibility of health across all cultures, thus changing the nature of the links to adaptation without assuming that any one culture is more or less adaptive than any another.

APPLIED DEVELOPMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY AND DEVELOPMENTAL PSYCHOPATHOLOGY

The field of developmental psychopathology (a term coined by Alan Sroufe and Sir Michael Rutter in their collected volume of Child Development in 1984) was at its very beginning, with key principles that were somewhat comparable to issues of cultural context above. Rather than examining discrete subgroups of children, with assumptions regarding separateness, developmental psychopathologists argued persuasively that adaptation should be considered on a continuum; that behavior that was diagnosed as “abnormal” or “dysfunctional” seldom represented a discrete break from normative development, but rather helped to elucidate principles of development. This theory raised an idea that, continues to be popular today, that development should be thought of in sync with functionality, and that cases where development is less functional have much to tell us about the nature of development itself, just as normative development may help us to further understand the meanings and causes of functionality. Similar to the cultural context discussion above, theoretical models of developmental psychopathology often emphasize variation within groups of children, or conceiving of a range of development rather than discrete groupings, though they may also involve direct comparisons of particular groups of children, based on more applied characteristics (e.g., comparing children who have received different diagnoses with each other and with children considered to be typically developing, to discern where and whether these diagnoses and groupings have implications for functional development).

The potential importance of basic developmental studies for their promise of informing clinical and preventive interventions, as well as for influencing public policies, was just beginning to take shape (Brooks-Gunn et al., 1991; Chase-Lansdale et al., 1991). The study of prevention science was also becoming popular, primarily through its links with mental health and community psychology (Tolan & Gorman-Smith, 2002; Tolan, 2001; Tolan et al., 2000), A number of scholars in community psychology, in particular, became interested in cyclical models of prevention research, with basic studies being derived from applied questions in conjunction with theoretical models. Once basic studies were completed, the goal was to use targeted data to assist in developing and implementing prevention and intervention studies. These studies, in turn, were expected to raise new questions, and to inform further basic research, as well as assist in developing progressively more refined and definitive intervention and prevention programs to implement and ascertain effectiveness. Ironically, given the history of CHAMP that, follows, I was very interested in these theoretical and pragmatic models, but did not pay particular attention to the other aspects of community psychology models that stress the importance of collaboration with a community. Rather, my collaborative interests stemmed from my more traditional developmental psychology training, which emphasized the importance of considering community and context from the perspective of getting reliable and accurate data on development.

ADOLESCENT PSYCHOLOGY

In addition, the field of adolescent development had begun to take on an importance of its own, with the increasing recognition of developmental psychologists that important, changes continue to take place after childhood (Hill, 1987; Steinberg, 1987). The initial meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence was held in 1986, and the Society grew extremely rapidly, providing many opportunities for those who were interested in development during the second decade of life, both from basic and applied perspectives, and encompassing a wide range of disciplines.

What these changes in the landscape of developmental psychology meant for young faculty members, such as myself, was that the academic world was split wide open, with huge new areas of potential study. It was certainly the case at that time that few studies had been conducted examining large subgroups of gender or minority groupings in order to determine appropriate links between developmental process and adaptive outcome within particular groups of children and adolescents. It was also the case that, although much was known about normative developmental process, very little of this basic science had been undertaken using methodologies that could be of help for more applied uses. Very little discussion or interplay took place between basic research scientists and more clinical or applied faculty (e.g., educators, psychologists, social workers, or program developers/intervention specialists).

Although many would agree that the level of interdisciplinary communication between basic and applied scientists (and, perhaps, more critically, between academics in general and those who are actually developing and implementing programs) still leaves much to be desired, it is important to recall that it was not so long ago when such communications essentially did not occur. Thus, while there is much room for improvement, one of the most stunning changes in the academic landscape of today is the need for all basic scientists to justify their social and behavioral science work, not just in terms of rationale, but also in terms of basic use in applied settings.

There was substantial work to be done, and many of us eager to do it. For myself, a number of critical experiences shaped ray particular interests, and the methods by which I went about designing the initial CHAMP basic longitudinal study. First and foremost, was my personal belief that there was much that developmental psychology, and a developmental approach more generally, had to offer to fields that actually attempted to promote development (particular prevention and intervention programs aimed at significant public health issues for children and adolescents). My belief stemmed from my excellent undergraduate and graduate training, and my mentors, Andy Collins, Megan Gunnar, and Ritch Savin-Williams. It was fortified and nurtured through my post-doctoral experiences at Educational Testing Service with Jeanne Brooks-Gunn.

During my time at Educational Testing Service, I had several experiences that proved pivotal in my design of future work. First, I conducted a literature review on the effectiveness on programs aimed at preventing initial and repeat teenage pregnancies. In addition, I served as a consultant to the NYC Mayor’s Committee on Teenage Pregnancy Prevention. Through these two experiences, I was able to understand and document, first-hand, how very little the domains of developmental psychology, program development and evaluation, and program design and implementation, had spoken to one another, and how potentially problematic that was for all disciplines. Those of us in developmental psychology had not yet learned to conduct our studies or discuss our findings in ways that could be straightforwardly helpful to program developers and implementers. Those developing programs at that time, had, for the most part, very little experience or consultation from people who could discuss their developmental relevance or rigorously evaluate their effects.

In addition to my work on teenage pregnancy prevention, other work aimed at adolescent development within a private parochial boys’ school in Harlem affected me in other ways. I found an incredible disconnect between what I would see in my travels within Harlem and what I would watch on the news in my New Jersey living room. The depiction of urban teenage boys on the evening news was one of pathology and despair, and served largely to make them appear different and pathological relative to other cultural subgroups (stories on gang violence, urban destruction, etc.). In my travels in Harlem, I met young boys and their families, and found them more similar to than different from suburban families I knew, both in their values and in their hopes and dreams for their children and their family as a whole. I became very interested in doing the kind of research that would inform other cultures about the more normative aspects of inner city family life, and that would, at the same time, take a perspective of enhancing family strengths rather than focusing on documenting weakness or pathology. Given my interest in teenage pregnancy prevention, the growing concerns regarding HIV infection among teenagers, I chose to focus my work prospectively, on prevention of HIV risk and delay of initial sexual activity.

Another factor that highly influenced the development of the theoretical models of CHAMP, was an interest of mine of mapping out the role of context in contributing to youth sexual behavior. I was interested in two different aspects of context: one, the demographics of a context, and two, the specific social situations that children were exposed to. For the first, I became interested in locating my work in communities and neighborhoods of highest contextual risk, (e.g., where highest HIV seroprevalence rates were found). With regard to the second, I was concerned in my reading of the literature on early sexual experience that we did not have a sense of the actual contexts in which early sexual risk taking occurs, that is, what do these experiences “look like”? What is their meaning for youth? I began developing a theoretical model that would describe the progression through different social contexts that would influence sexual risk taking and sexual debut.

When the opportunity arose to consider a position at the Institute for Juvenile Research (IJR) at University of Illinois at Chicago, I was particularly excited given the work of Patrick Tolan and colleagues (in particular, Deborah Gorman-Smith) in the area of antisocial behavior and adolescent violence. The approach they took in working on the Chicago Youth Development Study (CYDS) and the Metropolitan Area Community Study (MACS) was a direct application of the community psychology prevention and intervention model, and served as an excellent example for me, a young faculty member with interests in this model as relevant to early sexuality and HIV/AIDS prevention.

Both at ETS and at IJR, I worked persistently over several years to get funding. Over the course of 3 years, I wrote 7 different proposals (9 if you include amended applications), and received a couple of small, seed grants that allowed me to formulate ideas and working plans, until one of the larger grants was funded. Within one year, I was funded by two granting agencies, the NIMH Office on AIDS and the William T. Grant Foundation. I was able to begin the first of the CHAMP studies, a basic study of approximately 300 families, examining associations between family process, social, cognitive, and biological (pubertal) development, as well as mental health of caregiver and child, in their contribution healthy relationship and heterosexual development during the transition to adolescence.

All the CHAMP studies have focused on a specific age range: the transition to adolescence, ages 10–15. We have done this for a specific reason: in many prior studies of teenage pregnancy and sexual risk taking, studies were begun after youth were already pregnant or had reported being sexually active. In order to study the development of sexual risk taking or sexual health, we needed to begin our studies earlier, prior to initial sexual activity. However, we also needed to begin them at an age that most families would find acceptable, and within a time frame where we could reasonably expect some change in sexual activity. Therefore, we aimed our studies at this initial period of pre/early adolescence, where we expected some changes in behavior that could presumably be linked to health or to risk taking, but we also expected that the majority of youth would NOT be sexually active in the initial years of the study. This has allowed us to look prospectively at the development of heterosocial and heterosexual behaviors related to sexual health and sexual risk taking.

Early on, we learned several important lessons that would shape our basic study and our methods of beginning prevention and intervention work. One important and empowering lesson was, if you build it WELL, they will come! Over and over senior people told me, early in my career that good ideas paired with persistence will meet with success. It’s hard to believe it, though, until you see it for yourself. The literal and figurative change in fortune that funding permits allows one to create a program and truly see one’s ideas unfold before one’s very eyes. The beauty of the NIMH system is that thoughtful peer review serves to improve and refine good ideas so they are doable.

A second key lesson was, NEVER work alone! One of the most important things I did in the years while I was working on small seed grants was to involve students, colleagues, community members and stakeholders in the development of research ideas and implementation plans. Doing so was not merely a gesture of good will (as I had thought initially it would be), but ended up being a critical factor in decision making regarding methodological issues, such as where particular aspects of the study would take place, and how different measures would be administered. For example, at the time we were preparing to examine HIV risk behavior in 10–12 year olds, a measure called the “secret ballot” was highly regarded in academic circles. This method recommended the administration of sexual behavior measures with a series of “yes-no” questions, each contained in a separate sealed envelope. Items were sequenced in what was assumed to be the logical progression of sexual behaviors up to and including sexual intercourse, Children were to open items only until they answered “no” to a question. In this way, we would not be exposing children to questions about sensitive behavior any more than was necessary (e.g., only up to the next behavior in a presumed sequence).

The parent and school-community liaison who worked with me at one of our schools, were both against this procedure. They felt strongly that it was our staff’s responsibility to “protect” the children from items that were inappropriate based on their experiences, and should not be left to the children themselves. They gave several persuasive reasons, chief among them that for some children, reading items by themselves would not be possible based on literacy levels, and, for those children who could read the items, it would be too much of a temptation to continue the process and “uncover” all the information presented in the envelopes. Based on this, we developed our interview on Sexual Possibility Situations, which required trained interviewers to present to youth with a variety of detailed skip patterns aimed at keeping less sexually involved youth from answering more detailed and sensitive questions.

The lessons learned here served us very well in our later community collaborative intervention work. In the following sections, I will provide a brief overview of the CHAMP projects, primarily to assist readers in understanding the background in which the studies contained in this issue were undertaken.

CHAMP I:BASIC RESEARCH ON FAMILIES, MENTAL HEALTH FACTORS, AND HIV RISK

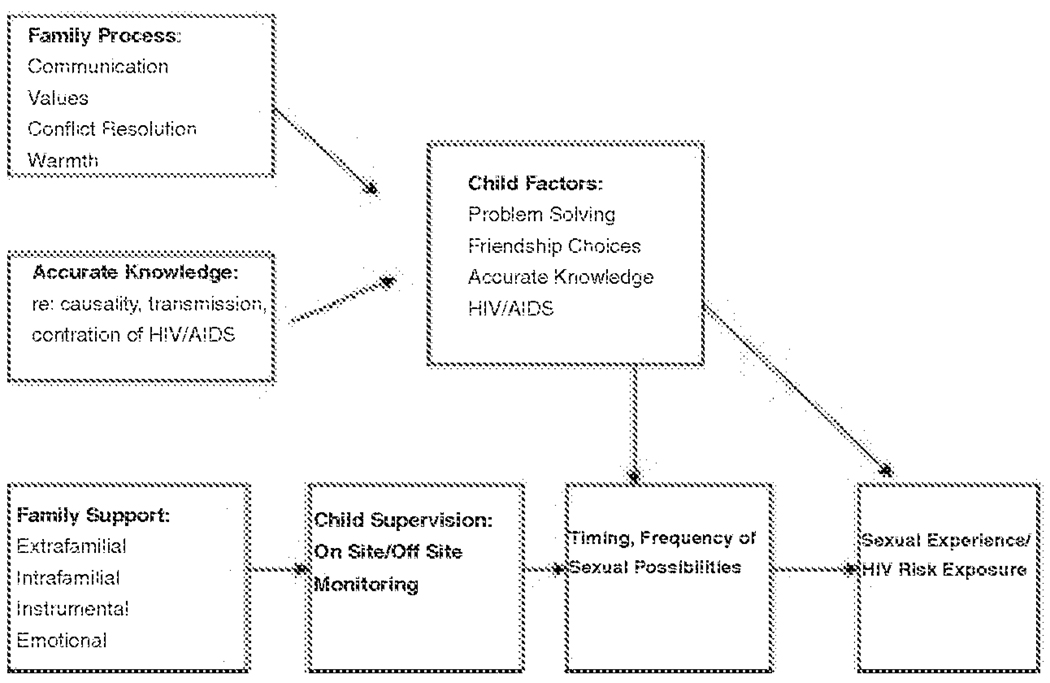

In this initial, basic research study, the goal was to develop knowledge regarding key intervenable variables for HIV risk prevention programs. To that end, a sample of 315 urban, African American families with pre-adolescent children was recruited from the South and West side of Chicago. All families were recruited via their child’s attendance at a school on or near a major public housing project in Chicago, an area with higher than average city wide rates of HIV infection that is primarily African American and poor (with high rates of joblessness, as well as other major health and social welfare concerns). This sample has now been interviewed three times; ages 10–12, 12–14, and 17–19 (refer to McBride, Paikoff & Holmbeck, 2003; Paikoff, 1997; Paikoff et al., 1997; Sagrestano et al., 1999; or Delucia, Paikoff & Holmbeck, and Tolou-Shams, Paikoff et al., in this volume, this volume for more information about sample recruitment and retention rates). At each data wave, age appropriate questions related to the theoretical model below were addressed (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual Model of Family Influences on HIV Risk Exposure

These data has been used to address a variety of research questions in numerous areas:

Family Demographics: Both parent education (HS/GED vs. No HS/GED) and parent employment (work since the child’s birth vs. no work since the child’s birth) were associated with youth participating in sexual possibility situations. Children least likely to have participated in these situations were more likely to have parents who reported an education through high school completion or GED and who had worked since the child’s birth (Paikoff, Parfenoff, Williams, McCormick, Greenwood, & Holmbeck, 1997). In addition, females were slightly more likely (p < .10) than males to be in these situations (Paikoff et al., 1997).

-

Family Relationships: Four aspects of family relationships were associated with pre-adolescent participation in sexual possibility situations: (1) family interactions; (2) children’s reports of parental control in decision making; (3) family support for children of teenaged mothers; and (4) parental communication and knowledge regarding HIV/AIDS.

Family Interactions: Videotaped interactions of family problem solving were rated by two coders, both African American, and one from the target community (e.g., a parent without children in the sample). Family interaction scales that focused on family emotions (e.g., parent and child warmth and humor) as well as the overall health of the family have been associated with exposure to sexual possibility situations, with more healthy and more positive emotional interactions associated with lack of exposure to sexual possibility situations (Paikoff et al., 1997).

Parental Control: In addition to family interaction, parent and child reports about family conflict, decision making, discipline and supervision were assessed at pre and early adolescence: Most parent and child reports about the family were uncorrelated with one another, and the only association with exposure to sexual possibility situations at preadolescence was the child report of family decision making. Children who reported that their parents had more control over family decision making also reported less exposure to sexual possibility situations (Paikoff et al., 1997). Parent reports of control were unassociated with children’s exposure to sexual possibility situations (Paikoff et al., 1997, 1997).

Family Support and Teenage Motherhood: For pre-adolescents whose mothers were teenagers at their first childbirth, greater family support was associated with lack of exposure to sexual possibility situations. For those preadolescents whose mothers were not. teenagers at the time of their first childbirth, however, greater family support was associated with increased exposure to sexual possibility situations (Paikoff et al., 1997).

Family Communication: Parents also were asked to rate whether or not they had discussed a variety of risk behavior topics with their child, and their comfort in doing so. Parents completed a 28 question measure regarding their own AIDS knowledge. Children who had not experienced sexual possibility situations had parents with more HIV/AIDS knowledge than children who had experienced sexual possibility situations (Parfenoff & McCormick, 1997). In addition, children who had been in sexual possibility situations were more likely to have parents who reported having discussed abstinence (staying away from sex) with them than those who had not been in these situations. Overall, parents were less likely to have discussed sexuality and related topics (including MV/AIDS) with their children than other risk topics (e.g., alcohol or drug use, cigarette smoking: Parfenoff & McCormick, 1997).

Friendship Relationships: Relationship maintenance (i.e., extent to which child will tolerate risk behavior to maintain relationship) and likelihood of peer pressure in children’s friendships were linked to exposure to sexual possibility situations. Youth who had not been in sexual possibility situations reported prioritizing resisting peer pressure over maintaining friendships and less likelihood of pressure from their friends; however, they also reported lower levels of friendship support overall (Paikoff, Holmbeck, Parfenoff, Bhorade, & Gillming, 1997). This finding regarding peer pressure and relationship maintenance is highly robust and is of particular interest, as it suggests that those pre-adolescents who experience sexual possibility situations are likely to perceive themselves as less motivated to resist pressure to engage in risk behaviors, and more like to experience such pressure.

Child Individual Processes: Within our model, 3 individual child processes were examined: pubertal maturation, social problem solving, and mental health. We are just beginning to examine data with regard to child mental health and social problem solving; pubertal maturation has not been associated with exposure to sexual possibility situations in our analyses to date (Sagrestano, McCormick, Paikoff, & Holmbeck, 1999), This is not particularly surprising as participants were in pre-to early puberty at the pre-adolescent data wave. With regard to mental health, children with Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD), and particularly girls, were more likely to be in sexual possibility situations (Donahue, Parfenoff, & Holmbeck, 1998). Depressive affect is not linked to exposure to sexual possibility situations; other aspects of child mental health have not been examined to date (Sagrestano, Paikoff, Fendrich, Parfenoff, & Holmbeck, 1997).

In addition to our early adolescent, a number of longitudinal studies have been conducted.

First, a longitudinal study of youth’s sexual debut and links to individual and family factors was completed and published in the Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology (McBride, Paikoff, & Holmbeck, 2003). In this study, pre-adolescent family and individual factors, such as family conflict, positive affect, and pubertal development, were studied longitudinally as linked to early sexual debut among urban African American young adolescents. Results indicated that girls were more likely to delay sexual debut past early adolescence than boys, and that more developed preadolescents with greater family conflict and less positive affect were least likely to delay sexual debut.

Second, a longitudinal study of family factors in contributing to depression among urban adolescents has appeared in the Journal of Family Psychology (Sagrestano, Paikoff, Holmbeck, & Fendrich, 2003). In this study, parent and adolescent levels of depression were examined in association with changes in family functioning, finding that increases in conflict and decreases in parental monitoring were associated with increases in child depressive symptomatology, and increases in conflict and decreases in positive parenting were associated with increases in parental depressive symptomatology.

In addition, two longitudinal studies on these data are reported in the current volume. DeLucia, Paikoff, and Holmbeck (this volume) use our longitudinal data to discuss methods of studying individual growth curves and trajectories of experience for our youth. Tolou-Shams, Paikoff et al., (this volume) talk about the role of parenting and adolescent mental health problems in contributing to adolescent HIV risk during the transition from early to late adolescence. Each of these studies takes advantage of the wealth of longitudinal data to conduct research which has direct implications for HIV prevention program development.

The basic CHAMP study has thus provided the background data and experiences for the development of the CHAMP family-based interventions. Additional findings from studies using baseline data from the intervention study have further helped to refine the intervention (Miller et al.; Traube et al.; McKay, Bannon et al.; in current volume).

CHAMP II: FAMILY BASED INTERVENTION TO PREVENT ADOLESCENT HIV RISK

Funding to study the design, delivery and outcome of the CHAMP Family Program is now in its’ ninth year. The initial proposal requested funding to involve African American pre-adolescents (4th and 5th graders) and their families in a test of a three-year preventive intervention. The CHAMP Family Program was delivered at the 4th and 5th grade (at an age where the vast majority of youth were not expected to have engaged in sexual behavior) and then the same cohort of children and families were followed to early adolescence (6th/7th grade) to participate in a second exposure of the program. Program effects are being tested within a longitudinal, experimental design with random assignment to the CHAMP Family Program or a longitudinal interview condition occurring in the fall of 4th/5th grade for youth in 4 elementary schools on the southside of Chicago. The impact of the program in relation to proximal outcomes (e.g., family process, parent and child AIDS knowledge and attitudes, use of social supports for assistance with parenting, child assertiveness and peer social problem solving skills) and distal outcomes (time spent in sexual possibility situations at pre-adolescence and sexual activity and HIV risk exposure behavior at early adolescence) continue to be examined.

To date, the following goals have been met: (1) Two CHAMP curricula (pre and early adolescence) have been developed; (2) A sample of 4th and 5th graders and their families have been recruited to participate in the study, randomly assigned to receive the CHAMP Family Program or a longitudinal interview condition and followed over time; (3) Preliminary analyses of programmatic effects are underway; (4) A CHAMP Collaborative Board, consisting of parents, school staff, community-based agencies and university-based researchers has met at least monthly over the last nine years and overseen the development, delivery and evaluation of the research study; (5) Opportunities to increase the leadership and research capacities of CHAMP Collaborative Board Members have been created; (6) A CHAMP Collaborative Board have been developed in the Bronx, New York; (7) There has been an ongoing translation of research to inform program development; and (8) Investigators and Board members have been involved in dissemination activities.

More specifically, two family-based HIV prevention curricula have been developed, extensively pilot tested and delivered. A 12-week 4th/5th grade family intervention and guiding protocol was created in collaboration with urban parents. The 4th/5th grade curriculum was pilot tested in three separate trials, with the final pilot involving Collaborative Board members and their children as participants. This was done for two reasons. First, the Board was committed to providing the community with an intervention of the highest quality, therefore, they wanted to experience firsthand the content and format of the program to ensure that it would be acceptable. Second, their participation was seen as the first step in training Board members to co-deliver the program with mental health interns when the CHAMP Family Program was brought to the field.

Next, a sample of 4th and 5th graders and their families were recruited to participate in the study, randomly assigned to receive the CHAMP Family Program or a longitudinal interview condition and followed longitudinally. A sample of 500 4th and 5th graders and their families were identified for participation in the study, with 324 children randomly assigned to receive the CHAMP Family Program and the remaining youth and their families assigned to a comparison condition. Of the 324 youth assigned to CHAMP, 274 (85%) could be located and invited to participate in the program. Factors that interfered with location included: (1) demolition of four of sixteen high-rise housing units within the target community; and (2) relocation of hundreds of families out of the community due to massive re-vitalization efforts by the city.

Of the 274 families located, 214 came to at least one meeting of the program (78%); 211 attended more than 3 sessions (77%); and 201 families (73% of families located) completed the program. In order to achieve these high rates of participation within the target inner-city community, university researchers and community parents developed intensive outreach strategies (McCormick et al., 2000). Involvement strategies included: (1) community parents in leadership roles making initial contacts with participant families (either via home visits or telephone calls), (2) multiple contacts with families prior to the first CHAMP meeting to establish familiarity and trust, (3) extensive discussions of purpose of study, funding sources, privacy issues, informed consent and prior experiences with universities and researchers to address hesitancies to participate, and (4) joint training (both mental health interns and community parents) in the use of systematic engagement strategies developed within other urban focused research projects (McKay et al., 2004).

In addition, a study to examine the impact of specific barriers, both within the family and the community, as well as resources that predicted program attendance in order to fine tune recruitment strategies was conducted. Data collected from CHAMP staff regarding their initial contacts with the first three cohorts of families (n = 227) invited to participate in CHAMP were analyzed to identify barriers and facilitators of program attendance and retention (Pinto et al., this volume). Briefly, parental concerns related to discussions about sex or HIV/AIDS was negatively related to total number of CHAMP sessions attended (r = −.47; p = .00), as well as presence of family stressors (r = −.16; p = .04). Multivariate analyses revealed parental motivation to participate (b = .97; p = .00) and parental understanding of the purpose of CHAMP (b = −1.5: p = .02) to be significant predictors of ongoing attendance (R2 = .24; p = .00). Based upon these findings, outreach and engagement strategies were developed in order to enhance participation. Preliminary analyses of programmatic effects have begun.

Delivery of the 4th and 5th grade intervention has been completed in Chicago. Preliminary effects are reported in McKay et al. (2004), and in this volume (McBride et al.). At the proximal level, preliminary findings already offer encouragement for the continued development and refinement of the CHAMP Family Program (McKay et al. 2004). More specifically, preliminary analyses reveal significant increases from pre to post assessment in the following domains: family decision making; attitudes regarding HIV/AIDS; family comfort related to discussions of sensitive topics; parental off-site monitoring (e.g., via phone, neighborhood supports; and disruptive behavioral difficulties. Parental anxiety and depression also decreased significantly from pre to post test (Paikoff, 1997). When posttest scores of families in the CHAMP Family Program are compared to those in the no treatment control condition, program effects for family decision making, with parents more likely to make decisions within the family, were significant (CHAMP mean 27.1 vs. control mean 34.0). In addition, families in CHAMP held significantly more positive attitudes about interacting with persons with AIDS (mean = 5.3) in comparison to control families (mean = 5.8). Off-site monitoring scores also significantly favored participation in the CHAMP program (mean = 6.2) in comparison to families in the control condition (mean = 5.0) (McKay et al., 2004).

Community collaboration has been critical to every aspect of CHAMP. This is an area where we have learned an enormous amount and at this point have reached a level of community partnerships where community members participate in the direction and focus of the research. More specifically, the entire program development, delivery and current evaluation phase of our project has been overseen by the CHAMP Collaborative Board. Since its inception, the Board has met at least monthly. Board members and other community parents have been trained along with mental health interns (e.g., undergraduate and graduate level social work and psychology students) to implement the program at schools and community sites. In addition to delivering the program, community members participate on committees that make key personnel and budget decisions, create project policies concerning personnel and data collection, design the intervention curriculum, and review proposals for research using the intervention data (see McKay, Hibbert et al., in this volume). Additionally, community Board members have participated in new “professional” roles as conference presenters, and as part-time and full-time project staff.

In addition, opportunities to increase the leadership and research collaboration capacities of CHAMP Collaborative Board Members have been created over the course of the projects. For example, in the second and third year of the initial funding cycle, the investigative team, including the CHAMP Collaborative Board received a small grant, “Strengthening Inner-city Communities Research Capacity: A Collaborative Partnership Model.” The primary purpose was to enhance urban parents, teachers and researchers’ capacities to collaborate in the development of community-based programming and research. In order to achieve this goal, a series of seminars and technical assistance workshops (a total of 36 hours) were conducted for all members of the CHAMP Collaborative Board. These seminars provided information and practical experience in identifying pressing community needs, exploring options for programming and understanding the program evaluation processes. In addition, homework writing and discussion exercises were developed. Small working groups of parents, teachers and researchers were formed and bi-monthly contacts were scheduled in order to facilitate development of writing skills and grant proposal development skills. A key outcome of the project was the development of small grant proposals. In addition to knowledge and skill acquisition related to research, the project provided an opportunity for Board members to develop personal leadership skills. A model developed by Carl Bell, M.D., for the development of human capabilities was used to encourage: (1) development of self (motivation, awareness, confidence, positive expectancy); (2) goal directedness; and (3) enhancement of skills (problem solving, decision making and communication).

A series of assessment measures and goal attainment rating scales were developed explicitly to assist Board members in tracking their learning and skill development. In addition, two grant proposals have been funded as a result of these efforts. First, funding was received from the NIMH for a longitudinal study, “Informed consent in urban AIDS and mental health research.” This project examines factors that influence the process of informed consent, initial and ongoing involvement in prevention research efforts for inner-city children and their adult caregivers. A particular emphasis of this study is to examine the influence of perceptions of racism and historical events such as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. The project is co-directed by a university trained staff member and a community parent. All project interviews are conducted by community parents (see Kerkorian et al., in this volume).

CHAMP III: IMPACT OF COLLABORATIVE PARTNERSHIPS

Next, Dr. McKay’s move to New York precipitated an opportunity to test the community collaborative model of HIV prevention along with the program. Thus, new funding from the National Institute of Mental Health was obtained to study the development and impact of CHAMP Collaborative Boards in two urban epicenters of the virus (New York and Chicago). At both sites, 2 major research aims will be addressed: Program design, adaptation to particular community need, delivery, outcome and transfer of ownership of the CHAMP Family Program are being examined.

The project is a multi-site study, jointly conducted by the current investigative team of CHAMP. The P.I. (McKay) coordinates the Bronx, New York site where a new CHAMP Collaborative Board has been formed in consultation with current Chicago Collaborative Board Members. The Co-P.I. (Paikoff) coordinates the expansion of CHAMP to a new urban community on the westside of Chicago with the current CHAMP Board providing primary leadership.

At both sites, the CHAMP Collaborative Boards now meet bi-monthly to review and adapt the CHAMP Family Program content to respond to emerging research data from the CHAMP Family Study and pressing community needs related to HIV risk. In addition, at both sites, the CHAMP Collaborative Board oversees the replication test of the impact of CHAMP with 4th and 5th grade children randomly assigned to the 3 year, developmentally focused intervention or longitudinal follow-up (see McKay, Hibbert et al., in this volume). Finally, the CHAMP Collaborative Boards are in the process of creating and executing a longitudinal plan for sustainability and linkage with existing resources (see Baptiste et al., in this volume).

A two site study was necessary in order to understand the process of replication of the Collaborative Board as a vehicle for urban, HIV prevention programming within diverse (e.g., geographically, racially/culturally) low-income communities. Two sites also provide the opportunity to examine issues related to local primacy (e.g., specific adaptations made to HIV prevention programs to ensure high cultural and contextual sensitivity) vs. the ability to transport a protocol-driven HIV preventive intervention from one community to another. This is particularly important as community level characteristics could impact the development of community-university partnerships (e.g., moving from a Midwestern city with high levels of racial segregation and concentrated high rise public housing to a large, eastern city with similar high concentrations of poverty, yet higher levels of racial/ethnic integration).

As the HIV epidemic began devastating other parts of the world, CHAMP investigators began to consider how adaptation the family-based approaches to HIV prevention could be made via collaborations within international contexts (see Bell et al., and Baptiste et. al., in this volume for a description of CHAMP projects in Trinidad and South Africa). In all, the CHAMP projects have proven to be both a serious opportunity to create knowledge regarding youth HIV prevention, but also a journey about learning how to conduct, research that has cultural and contextual relevance, recognized the strengths and protective influences of families and communities and provide maximum opportunities for collaboration among investigators and with communities.

Acknowledgments

Funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH55701; P. I. Paikoff; R01 MH63622; P. I. McKay; R01 MH58566; P. I. McKay; R01 MH64872; P. I. Bell) and the W. T. Grant Foundation is gratefully acknowledged. Dorian Traube is currently a pre-doctoral fellow at the Columbia University School of Social Work supported by a training grant from the National Institutes of Mental Health (5T32MH014623-24).

Footnotes

COPYRIGHT NOTICE: The copy law of the United States (Title 17 U.S. Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship or research”. Note that in the case of electronic files, “reproduction” may also include forwarding the file by email to a third party. If a user makes a request for, or later uses a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of “fair use”, that user may be liable for copyright infringement. USC reserves the right to refuse to process a request if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. By using USC’s Integrated Document Delivery (IDD) services you expressly agree to comply with Copyright Law.

This body of work is the result of the dedication of CHAMP Co-Investigators: Roberta Paikoff, PhD, Mary M. McKay, PhD, Carl C. Bell, MD, Donna Baptiste, PhD and Sybil Madison-Boyd, PhD. In addition, the significant contributions of CHAMP Project Directors (D. Coleman, McKinney, I. Coleman, Hibbert, Leachman, Lawrence and Miranda). CHAMP staff and participants is significant. Finally, CHAMP Collaborative Board members have worked tirelessly over the last decade to ensure the success of this work.

REFERENCES

- Aponte HJ, Zarski J, Bixenstene C, Cibik P. Home/community based services: A two-tier approach. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1991;61(3):403–408. doi: 10.1037/h0079270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptiste D, Paikoff R, McKay M, Madison-Boyd S, Coleman D, Bell C. Collaborating w/ an urban community to develop an HIV and AIDS Prevention Program for black youth & families. Behavior Modification. 2005;29:370–416. doi: 10.1177/0145445504272602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd-Franklin N. Black Families. In: Walsh F, editor. Normal Family Process. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Phelps E, Elder GH. Studying lives through time: Secondary data analyses in developmental psychology. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27(6):899–910. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control. New Study Profiles Hispanic Births in America. [Released February 13, 1998];National Center for Health Statistics. 1998 Retrieved from the World Wide Web: http://www.cdc.gov/cchswww/releases/98/facts/98sheets/hisbirth.htm.

- Center for Disease Control. Atlanta, Georgia: Center for Disease Control; 2000. Tracking the hidden epidemics: Trends in STDs in the United States, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control. Atlanta, G A: Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2001. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report. [Google Scholar]

- Chase-Lansdale PL, Mott FL, Brooks-Gunn J, Phillips DA. Children of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth: A unique research opportunity. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27(6):918–931. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Garmezy N. Prospects and promises in the study of resilience. Development & Psychopathology. 1993;5(4):497–502. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton HL. AIDS in Blackface. Daedalus. 1989;118(3):205–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delucia C, Paikoff RL, Holmbeck GN African American youth: Results from the CHAMP Basic Study. Social Work in-Mental Health. 1/2. Vol. 5. The Haworth Press, Inc.; 2007. Individual growth curves of frequency of sexual intercourse among urban, adolescent; pp. 59–80. Published simultaneously in Community Collaborative Partnerships and Empirical Findings: The Foundation for HIV Prevention Research Eforts. [Google Scholar]

- DiLorenzo T, Hein K. Adolescents: The leading edge of the next wave of the HIV epidemic. In: J.L. Wallender LJ, editor. Adolescent Health Problems: Behavioral Perspectives. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 117–140. [Google Scholar]

- Donahue BB, Parfenoff SH, Holmbeck GN. Oppositional-defiant disorder and risk for early sexual experience in preadolescents; Presentation submitted to Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence; San Francisco, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fullilove MT, Fullilove RE. Understanding sexual behaviors and drug use among African Americans: A case study of issues for survey research. In: Ostrow DG, Kessler RC, editors. Methodological Issues in AIDS Behavioral Research. New York: Plenum Press; 1993. pp. 117–132. [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith J, Stanton B, Feigelman S, Ricardo l, Black M, Kalijee K. Challenges and rewards of involving community in research: An overview of the “Focus on Kids” HIV-Risk Reduction Program. Health Education Quarterly. 1996;23(3):383–394. doi: 10.1177/109019819602300308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garmezy N. Vulnerability and resilience. In: Funder DC, Parke RD, editors. Studying lives through time: Personality and development. APA science volumes. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 1993. pp. 377–398. [Google Scholar]

- Garmezy Norman. Developmental psychopathology: Some historical and current perspectives. In: Magnusson D, Casaer P, editors. Longitudinal research on individual development: Present status and future perspectives. European network on longitudinal studies on individual development. New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press; 1993. pp. 95–126. [Google Scholar]

- Hill JP. Research on adolescents and their families: Past and prospect. In: Irwin CE, editor. Adolescent social behavior and health. New Directions for Child Development no.37. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemmott JB, Jemmott US. Increasing condom-use intentions among sexually active Black adolescent women. Nursing Research. 1992;41:273–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemmott JB, Jemmott L, Fong GT. Abstinence and safer sex HIV risk reduction interventions for African American Adolescents. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;270:1529–1536. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.19.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison S, Bell C, Sewell S, Nash G, McKay M, Paikoff R. “True community/academic partnerships.”. Psychiatric Services. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Madison S, McKay M, Paikoff RL, Bell C. “Community collaboration and basic research: Necessary ingredients for the development of a family-based HIV prevention program.”. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2000;12:281–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten Ann S, Powell Jenifer L. A resilience framework for research, policy, and practice. In: Luthar S, editor. Resilience and vulnerability: Adaptation in the context of childhood, adversities. New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press; 2003. pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Curtis WJ. Integrating competence and psychopathology: Pathways toward a comprehensive science of adaption in development. Development & Psychopathology. 2000;12(3):529–550. doi: 10.1017/s095457940000314x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride CK, Paikoff RL, Holmbeck GN. Individual and Familial Influences on the Onset of Sexual Intercourse Among Urban African American Adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(1):159–167. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick A, McKay M, Gilling G, Paikoff R. “Involving families in an urban HIV preventive intervention: How community collaboration addresses barriers to participation.”. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2000;12:299–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Chasse KT, Paikoff RL, McKinney L, Baptiste D, Coleman D, Madison S, Bell CC. Family-level impact of the CHAMP family program: A community collaborative effort to support urban families and reduce youth HIV risk exposure. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2004.04301007.x. (under review) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay M, Hibbert R, Hoagwood K, Rodriguez J, Murray L. “Integrating evidence-based engagement interventions into ‘real world’ child mental health settings. Journal of Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention. 2004;4:177–186. [Google Scholar]

- McKay M, Paikoff R, Baptiste D, Bell C, Coleman D, Madison S, McKinney L CHAMP Collaborative Board. “Family-level impact of the CHAMP Family Program: A community collaborative effort to support urban families and reduce youth HIV risk exposure.”. Family Process. 2004:77–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2004.04301007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay M, Paikoff R, Bell C, Madison S, Baptiste D. Community Partnership to Reduce Urban Youth HIV Risk. National Institute of Mental Health, Office on AIDS funded grant; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. The impact of economic hardship on Black: families and children: Psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Development. 1990;61:311–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paikoff RL. Applying developmental psychology to an AIDS prevention model for urban African American youth. Journal of Negro Education. 1997;65:44–59. [Google Scholar]

- Paikoff R, McKay M, Bell C. The Chicago HIV prevention and adolescent mental health project (CHAMP) family-based intervention. National Institute of Mental Health, office on AIDS and William T. Grant Foundation funded grants; 1994

- Paikoff RL, Parfenoff SH, Williams SA, McCormick A, Greenwood GL, Holmbeck GN. Parenting, parent-child relationships, and sexual possibility situations among urban African American Pre-Adolescents: Preliminary Findings and Implications for HIV Prevention. Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11:11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Parfenoff SH, McCormick A. Presentation at the Biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development. Washington, D.C.: 1997. Parenting preadolescents at risk: Knowledge, attitudes, and communication about HIV/AIDS. [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Mahler KA, Rosario M. AIDS prevention and adolescents families. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1995;7(4):320–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagrestano LM, et al. The role of depression in family relationships among inner-city African American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- Sagrestano LM, McCormick SH, Paikoff RL, Holmbeck GN. Pubertal development and parent-child conflict in low-income, urban, African American Adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1999;9(1):85–107. [Google Scholar]

- Sagrestano LM, Paikoff RL, Hombeck GN, Fendrich M. A longitudinal examination of familial risk factors for depression among inner-city African American adolescents. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17(1):108–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB, Dornbusch SM. Challenges in studying minority youth. In: Feldman SS, Elliott GR, editors. At the Threshold: The Developing Adolescent. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1990. pp. 123–146. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. Impact of puberty on family relations: Effects of pubertal status and pubertal timing. Developmental Psychology. 1987;23(3):451–460. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Lamborn SD, Dornbusch SM, Darling N. Impact of parenting practices on adolescent achievement: Authoritative parenting, school involvement, and encouragement to succeed. Child Development. 1992;63(5):1266–1281. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson HC, White JJ. AIDS prevention struggles in ethnocultural neighborhoods: Why research partnerships with community based organizations can’t wait. AIDS Education & Prevention. 1994;6:126–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SB, Quinn SC. The Tuskegee syphilis study, 1932 to 1972: Implications for HIV education and AIDS use education programs in the black community. American Journal of Public Health. 1991;81(11):1495–1505. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.11.1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D. What violence prevention research can tell us about developmental psychopathology. Developmental & Psychopathology. 2002;14(4):713–729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH. Emerging themes and challenges in understanding youth violence involvement. Journal of Clinical and Child Psychology. 2001;30(2):233–239. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3002_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D, Loeber R. Developmental timing of onsets of disruptive behaviors and later delinquency of inner-city youth. Journal of Child & Family Studies. 2000;9(2):203–220. [Google Scholar]

- Tolou-Shams M, Paikoff RL, McKirnan DJ, Holmbeck GN. Mental health and HIV risk among African American Adolescents: The role of parenting. Social Work in Mental Health. 2005;5(1/2):25–56. [Google Scholar]