Abstract

Background and purpose:

SKF96365 (SKF), originally identified as a blocker of receptor-mediated calcium entry, is widely used diagnostically, as a blocker of transient receptor potential canonical type (TRPC) channels. While SKF has been used as a tool to define the functional roles of TRPC channels in various cell and tissue types, there are notable overlapping physiological and pathophysiological associations between TRPC channels and low-voltage-activated (LVA) T-type calcium channels. The activity of SKF against T-type Ca channels has not been previously explored, and here we systematically investigated the effects of SKF on recombinant and native voltage-gated Ca channel-mediated currents.

Experimental approach:

Effects of SKF on recombinant Ca channels were studied under whole-cell patch clamp conditions after expression in HEK293 cells. The effect of SKF on cerebellar Purkinje cells (PCs) expressing native T-type Ca channels was also assessed.

Key results:

SKF blocked recombinant Ca channels, representative of each of the three main molecular genetic classes (CaV1, CaV2 and CaV3) at concentrations typically utilized to assay TRPC function (10 µM). Particularly, human CaV3.1 T-type Ca channels were more potently inhibited by SKF (IC50∼560 nM) in our experiments than previously reported for similarly expressed TRPC channels. SKF also inhibited native CaV3.1 T-type currents in a rat cerebellar PC slice preparation.

Conclusions and implications:

SKF was a potent blocker of LVA T-type Ca channels. We suggest caution in the interpretation of results using SKF alone as a diagnostic agent for TRPC activity in native tissues.

Keywords: SKF 96365, T-type calcium channels, TRPC antagonist, T-type calcium channel inhibition

Introduction

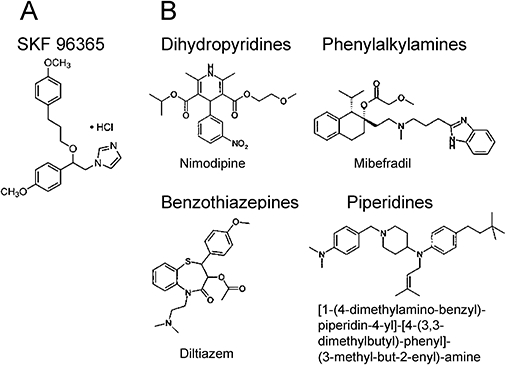

SKF96365 (SKF) was originally described as a selective blocker of receptor-mediated Ca entry (RMCE) over Ca release from internal stores in non-excitable cells such as platelets, endothelial cells and neutrophils (Merritt et al., 1990). In the interim, SKF has been used extensively to elucidate the contributions of RMCE or store-operated Ca entry (SOCE) in many physiological processes. Transient receptor potential canonical type (TRPC) channels (channel nomenclature follows Alexander et al., 2009) have been demonstrated to mediate RMCE and in some cases SOCE (alternatively known as capacitative Ca entry) (Clapham et al., 2001; Moran et al., 2004), and are thought to be a major molecular target underlying inhibition by SKF (Kiselyov et al., 1998; Zhu et al., 1998; Rychkov and Barritt, 2007). Although less bulky than classical voltage-gated Ca channel antagonists (Merritt et al., 1990; Doering and Zamponi, 2003) (Figure 1), SKF has been shown to inhibit high-voltage-activated (HVA) L-type Ca channels in GH3 pituitary cells and smooth muscle cells (Merritt et al., 1990). Additional reports indicate further blocking effects of SKF on K channels (Schwarz et al., 1994; Liu et al., 2007), the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca-ATPase (Mason et al., 1993), nicotinic receptors (Hong and Chang, 1994) and voltage-gated Na channels (Hong et al., 1994).

Figure 1.

Structure of SKF96365 compared to voltage-activated calcium channel antagonists. (A) SKF96365 (1{β-[3-(4-methoxyphenyl)propoxyl]-4-methoxyphenethyl}-1H-imidazole hydrochloride) consists of an alkylated imidazole ring which can be present in the phenylalkylamine class of Ca channel antagonists such as mibefradil. (B) Structure of various classes of Ca channel antagonists. Dihydropyridines typically consist of a core pyridine structure, phenylalkylamines consist of at least one phenyl ring linked to an amine head group by an alkyl chain, benzothiazepines have a rigid bulky tricyclic core with several substituents. Diphenylbutylpiperidines typically have one or more heterocyclic amine piperidine.

Accumulating lines of evidence indicate that in many cell and tissue types, TRPC channel family members share functional roles with low-voltage-activated (LVA) T-type Ca channels and also that both are over/re-expressed in certain pathological conditions such as cancer (Panner et al., 2005; Bomben and Sontheimer, 2008) and hypertension (Self et al., 1994; Liu et al., 2009). In many instances, the functional contribution of the TRPC channels has in part been assessed pharmacologically by blockade with SKF. SKF in the micromolar range (2–100 µM) inhibits Ca influx through TRPC channels heterologously expressed in human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293), as well as in many native systems (Okada et al., 1998; Zhu et al., 1998; Wang and Poo, 2005; Bomben and Sontheimer, 2008; Romero-Mendez et al., 2008). Given that both TRPC and voltage-gated Ca channels mediate Ca influx across overlapping membrane potentials, together with previous reports of SKF blockade of HVA L-type Ca channels, the use of SKF as a diagnostic tool for native TRPC channel activity requires further investigation. This becomes even more important in the case of T-type Ca channels which can generate Ca influx at resting membrane potentials and may contribute to processes attributed to TRPC such as the maintenance of intracellular Ca levels (Kim et al., 2007).

To the best of our knowledge, there has been no systematic study reporting the effects of SKF on the major classes of HVA and LVA Ca channels. In the present report, we have studied the effects of SKF on recombinant T-type, P/Q-type, N-type and L-type Ca channels. We have also utilized brain slices to investigate the effect of SKF on native CaV3.1 T-type Ca currents in rat cerebellar Purkinje cells (PCs). The results show that SKF is a potent blocker of LVA and HVA Ca channels. A detailed analysis of recombinant LVA hCaV3.1 T-type Ca channels shows that high-affinity blockade (IC50 = 563 nM) occurs largely in a state-independent manner. SKF also inhibits native CaV3.1 T-type currents in cerebellar PCs. Overall, our study found that SKF blocked T-type Ca channels more potently than recombinant TRPC channels similarly expressed in heterologous systems (Boulay et al., 1997; Okada et al., 1998; Zhu et al., 1998), and at similar or lower concentrations in native systems (Kim et al., 2003; Wang and Poo, 2005; Bomben and Sontheimer, 2008; Romero-Mendez et al., 2008). Given the sometimes overlapping physiological contributions of TRPC and T-type Ca channels, we conclude that caution should be exercised when utilizing SKF as the sole pharmacological agent to assess the contributions of RMCE and SOCE in native systems.

Methods

Cell culture and transient expression

HEK293 were grown in standard Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 50 units·mL−1 penicillin/streptomycin. The cells were grown up to ∼80% confluence and maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 95% room air and 5% CO2. Stable cell lines (in HEK293/tsa-201) expressing human CaV3.1, CaV3.2, CaV3.3 T-type (denoted as hCaV3.X), rat brain CaV3.1, CaV2.1 P/Q-type (+β4+α2δ2) and CaV2.2 N-type (+β1b+α2δ2) channels (denoted as rCaVX.X) were kindly provided by Neuromed Pharmaceuticals. Stable cell lines were maintained in supplemented DMEM containing appropriate antibiotics for selection: zeocin (25 µg·mL−1) for hCaV3.1; hygromycin (150 µg·mL−1), blasticidine (10 µg·mL−1), geniticin (600 µg·mL−1) for hCaV3.2; hygromycin (300 µg·mL−1) for hCaV3.3; zeocin (50 µg·mL−1) for rCaV3.1; hygromycin (150 µg·mL−1), blasticidine (10 µg·mL−1), zeocin (200 µg·mL−1) for rCaV2.1 P/Q-type channel; and hygromycin (300 µg·mL−1), blasticidine (10 µg·mL−1), zeocin (300 µg·mL−1) for rCaV2.2 N-type channel. Stable cell lines were plated on glass coverslips 24 h before recordings. hCaV3.2, rCaV2.1 and rCaV2.2 channels were induced with doxycycline at the time of plating. Rat brain CaV1.2 L-type Ca channels (denoted as rCaV1.2) were expressed transiently in HEK293 cells together with α2δ and β2A subunits using the standard Ca phosphate method. Cells transfected with rCaV1.2 channel complex were plated onto glass coverslips after 24 h of transfection and recorded 24 h after plating. As a reporter for transient L-type Ca channel expression, the CD8 marker plasmid was co-transfected.

Electrophysiological recordings from HEK293 cells and data analysis

Macroscopic currents were recorded using the whole-cell patch clamp technique with the external recording solution containing (in mM): 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 40 tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA Cl), 92 CsCl, 10 glucose, pH 7.4 with CsOH, ∼305 mOsm, and the internal pipette solution containing (in mM): 130 Cs-methanesulphonate, 11 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 2 MgCl2, 4 Mg-ATP, 0.3 Na-GTP, pH 7.2 with CsOH, ∼290 mOsm. Macroscopic currents were recorded using Axopatch 200B amplifiers (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA), controlled and monitored with Pentium IV personal computers running pClamp software version 9 (Axon Instruments). Fire-polished patch pipettes (borosilicate glass) had typical resistances of 3–5 MΩ when containing internal solution. The bath was connected to the ground via an Ag–AgCl pellet. Data were low-pass filtered at 2 kHz using the built-in Bessel filter of the amplifier and sampled at 10–20 kHz. The amplifier was also used for capacitive transient and series resistance compensation between 70 and 85% on each cell. Leak subtraction of leakage currents was either performed on-line using a P/4 protocol or else performed with Clampfit (Axon Instruments) during off-line analysis. All recordings were performed at room temperature (20–22°C). Current–voltage (I–V) relationships were obtained by holding the cells at a potential of −100 mV (for T-type and N-type channels) or −80 mV (for L-type and P/Q-type channels) before applying 150 ms pulses to potentials from −80 to +10 mV every 5 s in 5 mV increments. The potential that elicited peak current (Vmax) was obtained from this protocol and used as the test pulse voltage (peak potential) in subsequent protocols. Series resistance was also monitored with a 5 ms hyperpolarizing pulse immediately before the test pulse to ensure that this variable was relatively constant, and any changes in peak current levels were not because of significant changes in series resistance. Effects of different concentrations of SKF were investigated using 120 ms steps to peak potential every 5 s (0.2 Hz) from a holding potential of −100 mV (for T-type and N-type) or −80 mV (for L-type and P/Q-type). To quantify the per cent of channel inhibition during SKF or control solution perfusion, the following equation was used: % inhibition = [1 − (I(t)/Imax)]× 100, where Imax is the peak current magnitude at equilibrium (averaged 2–5 values) and I(t) is the equilibrium current after block.

I–V relationships were fitted with the modified Boltzmann equation, I = [Gmax× (Vm−Erev)]/{1 + exp[(Vm−V0.5a)/Ka]}, where Vm is the test potential, V0.5a is the half-activation potential, Erev is the extrapolated reversal potential, Gmax is the maximum slope conductance and Ka reflects the slope of the activation curve. Microcal Origin (version 7.5, Northampton, MA, USA) was used to analyse data and generate figures. Dose–response curves were fitted by non-linear curve fitting of the Hill equation to the data using the Origin software. Steady-state inactivation of hCaV3.1 channels was measured by holding the cells for 200 ms at various indicated potentials followed by a 90 ms test pulse to Vmax. Steady-state inactivation curves were analysed using the following Boltzman equation: I = Iss+ (1 −Iss)/[1 + exp(V−V0.5,inact/kinact)], where I is the peak current amplitude, Iss is the non-inactivating fraction, V is the membrane potential, V0.5,inact is the half-inactivation potential and kinact is the slope factor. Tail currents were measured over a range of negative potentials from −150 to −60 mV in 10 mV increments after a 9 ms depolarizing pulse to −30 mV.

Electrophysiological recordings from cerebellar slices

All animal care and experimental procedures were done in accordance with the recommendations of the Canadian Council on Animal Care and the animal care regulations and policies of the University of British Columbia. Cerebellar slices were obtained from male Wistar rats (9–11 days old) as previously described (Hildebrand et al., 2009). Briefly, the animals were anaesthetized with halothane, and decapitated, with the head being immediately chilled in a protective sucrose cutting solution containing (in mM): 50 sucrose, 92 NaCl, 5 KCl, 26 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 0.5 CaCl2, 7 MgSO4, 15 glucose, 1 kynurenate and bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2. All dissection and slicing were performed in this solution. The cerebellar vermis was then removed with a scalpel and glued in the sagittal orientation to the stage of a Vibratome 1500 Sectioning System (St Louis, MO, USA). Sagittal slices (300 µm) were cut from the cerebellar vermis and transferred to a recovery chamber with bicarbonate-buffered saline (BBS) solution at 34°C, containing (in mM): 125 NaCl, 3 KCl, 26 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 20 glucose, 1 kynurenate and 0.1 picrotoxin, and bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2. Once slicing was complete, the heating in the water bath containing the recovery chamber was turned off, and the recovery chamber was allowed to cool down to room temperature.

For electrophysiological recordings, the cerebellar slices were transferred to a Warner recording chamber (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT, USA) and perfused with bubbled BBS external solution containing 300 nM tetrodotoxin, 5 mM TEA Cl, 1 mM 4-aminopyridine and 30 µM CdCl2 to enable recordings of isolated T-type Ca channel currents. Cerebellar PCs were visually identified using a Zeiss Axioskop 2 with IR-DIC optics (Carl Zeiss, Inc., Gottinger, Germany), and whole-cell patch clamp recordings from PCs were performed using a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The internal pipette solution contained (in mM): 140 Cs-methanesulphonate, 5 TEA Cl, 0.5 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 4 MgATP, 0.5 Na3GTP and 0.3 EGTA, pH adjusted to 7.3, ∼290 mOsm. Borosilicate glass pipettes had typical resistances of 4–6 MΩ when filled with internal solution. To ensure the quality of the space clamp, modulatory effects were studied on T-type currents of moderate amplitude elicited every 10 s from a holding potential of −75 mV (with a 500 ms pre-pulse to −90 mV to remove inactivation) to depolarizing 200 ms test pulses ranging between −46 and −35 mV. Cells with leak current (voltage-clamped baseline current recorded from the holding potential period) above 300 pA at Vh = −75 mV were discarded. Data were low-pass filtered at 2 kHz using the built-in Bessel filter of the amplifier, with sampling at 20 kHz. Series resistance was compensated between 70 and 75% on every cell, while liquid junction potentials that were calculated to be approximately 9 mV (at 22°C) were left uncorrected. Leak subtraction was performed off-line using Clampfit 9 (Molecular Devices).

Data analysis

All averaged data are presented as mean ± SEM. Means were tested for significance with Student's two-tailed t-test, with P < 0.05 considered significant. P values were reported only where significance was observed.

Materials

A 100 mM stock of SKF96365 (Tocris Bioscience, Ellisville, MO, USA) was prepared in autoclaved water, aliquoted, stored at −20°C and used within 2 months. Dilutions in recording solution were made from the stock on the day of experiments to reach the final concentration. Gravity-driven perfusion occurred at a rate of ∼2 mL·min−1 in a coverslip chamber of 300 µL liquid volume.

Results

SKF potently and reversibly inhibits recombinant T-type calcium channels

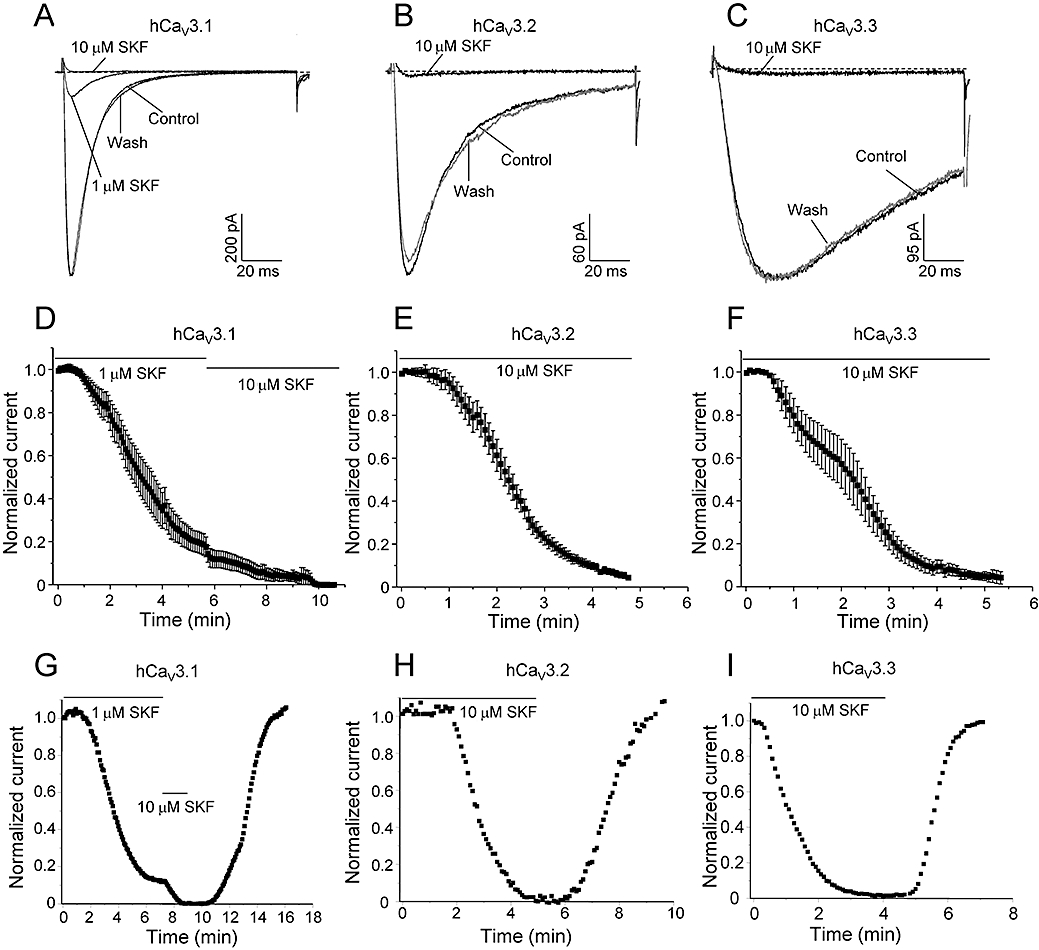

LVA T-type Ca channels and TRPC channels co-exist in many cell types where they play significant roles in relation to many physiological and pathophysiological conditions. Pharmacological blockade has been extensively used to explore the functional implications of Ca influx through both T-type and TRPC channels as it relates to various Ca-mediated signalling and excitatory pathways. Pharmacological blockade with SKF has been used to identify TRPC channels in many cell types, and we wished to determine whether T-type Ca channels could be affected by SKF. We initially utilized HEK293 cells stably expressing hCaV3.1 channels which under whole-cell patch clamp conditions generated currents ranging from ∼800 to 1000 pA (Figure 2A; in 2 mM extracellular Ca). Perfusion of 1 µM SKF reversibly inhibited 86.3 ± 0.1% (n = 15) of the current, reaching maximum inhibition in 6–7 min. Application of 2.5 µM (data not shown) and 10 µM SKF both completely abolished hCaV3.1 currents within 3–4 min (n = 6–7). Figure 2A shows representative inward Ca current (ICa) traces of block by 1 and 10 µM SKF, and subsequent recovery from inhibition upon washing with control external solution. Figure 2D shows the mean time-course of inhibition by 1 and 10 µM SKF on the same cells (n = 6), while Figure 2G shows a representative time-course of block and recovery from inhibition. Examining the other two T-type isoforms, hCaV3.2 (99.9% inhibition, Figure 2B,E,H and Figure 3D, n = 8) and hCaV3.3 (97.2% inhibition, Figure 2C,F,I and Figure 3D, n = 7) channels also showed potent block by 10 µM SKF that reached steady-state inhibition in approximately 5 min. As evident from the current traces, the macroscopic activation and inactivation kinetics of all three T-type Ca channels were not altered during SKF blockade (Figure 2A–C). For hCaV3.1 currents, tau activation and inactivation values were compared before and after perfusion of 1 µM SKF (Figure 2A, control, τ-act = 1.9 ± 0.1 ms, n = 15; 1 µM SKF, τ-act = 1.6 ± 0.8 ms, n = 15; control τ-inact = 11.9 ± 0.4 ms, n = 15; 1 µM SKF τ-inact = 12.3 ± 0.5 ms, n = 15). For hCaV3.2, tau activation and inactivation values were compared at 50% inhibition during perfusion of 10 µM SKF (Figure 2B, control, τ-act = 3.0 ± 0.1 ms, n = 8; 10 µM SKF, τ-act = 2.7 ± 0.1 ms, n = 8; control τ-inact = 15.8 ± 0.9 ms, n = 8; 10 µM SKF τ-inact = 17.3 ± 1.0 ms, n = 8). Macroscopic current kinetics also remain unchanged for hCaV3.3 currents compared at 50% inhibition during perfusion of 10 µM SKF (Figure 2C, control, τ-act = 11.5 ± 0.6 ms, n = 7; 10 µM SKF, τ-act = 11.7 ± 0.8 ms, n = 7; control τ-inact = 140.6 ± 2.8 ms, n = 7; 10 µM SKF τ-inact = 137.0 ± 9.9 ms, n = 7).

Figure 2.

SKF is a potent blocker of T-type calcium channels. Representative ICa during 120 ms depolarizations to Vmax from a holding potential of −100 mV before (control), after perfusion with different concentrations of SKF (as indicated) and after wash-out with control solution (wash) for hCaV3.1 (A), hCaV3.2 (B) and hCaV3.3 (C). Traces shown here after complete wash-out of SKF are taken at 6.5, 5.5 and 3.3 min for A, B and C respectively. (D) Mean time-course of ICa inhibition by 1 and 10 µM SKF for hCaV3.1. Mean time-course of ICa inhibition by 10 µM SKF for hCaV3.2 (E) and hCaV3.3 (F). Representative time-course of current inhibition and recovery from inhibition for hCaV3.1 (G), hCaV3.2 (H) and hCaV3.3 (I). Currents were elicited by depolarization to Vmax (−35 to −25 mV, 120 ms duration) applied every 5 s from a holding potential of −100 mV. The apparent rates of channel activation and inactivation did not differ before, during or after perfusion of SKF (see text for statistics).

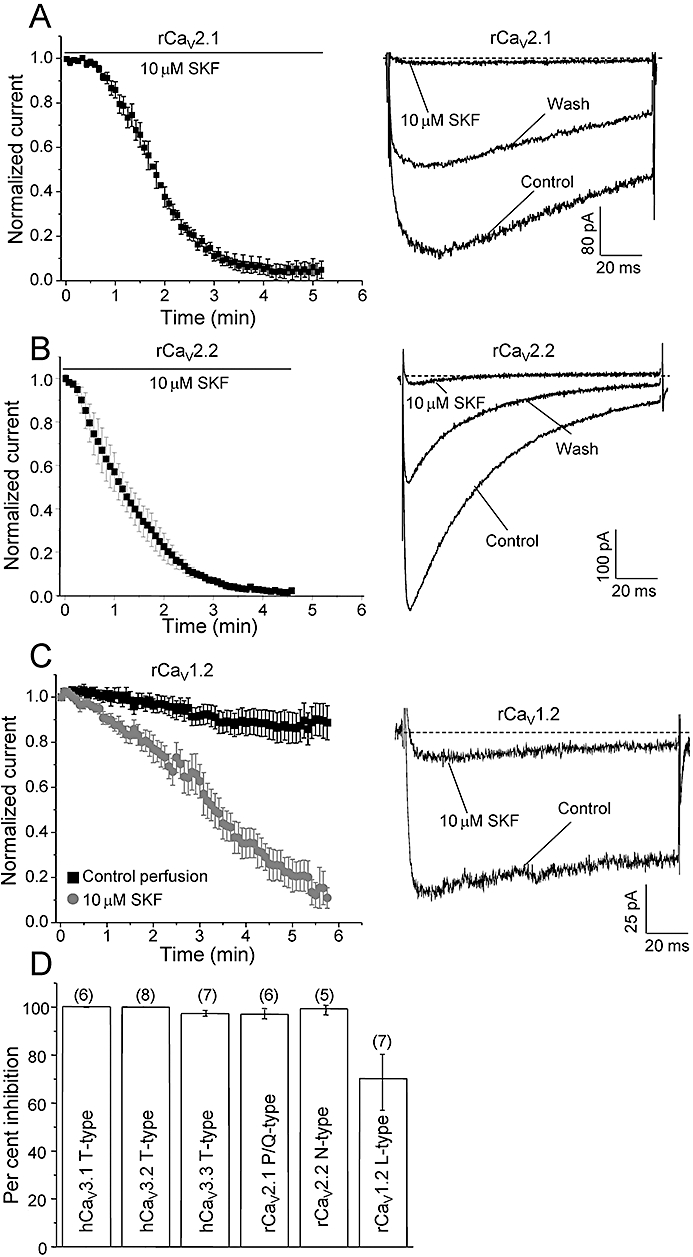

Figure 3.

SKF blocks rCaV2.1 P/Q-type, rCaV2.2 N-type and rCaV1.2 L-type calcium channels. Mean time-course of current inhibition of recombinant rCaV2.1 P/Q-type (A) and rCaV2.2 N-type Ca channels (B) by 10 µM SKF. Currents were elicited by depolarization to Vmax (0–5 mV for P/Q and 20 mV for N-type, 120 ms duration) applied every 5 s from a holding potential of −80 mV for P/Q-type and −100 mV for N-type. Right panel shows representative ICa during 120 ms depolarizations before, after perfusion of 10 µM SKF and after wash-out with control solution, as indicated. The rates of channel activation and inactivation did not differ before, during or after perfusion of SKF (see text for statistics). (C) Mean time-course of current inhibition of recombinant rCaV1.2 L-type Ca channels by 10 µM SKF (grey curve). Black curve represents the mean time-course of run-down during control perfusion. Right panel shows representative ICa during 120 ms depolarizations before and after perfusion of 10 µM SKF (see text for statistics). (D) Comparison of the effect of 10 µM SKF on four classes of Ca channels. Data for T-type Ca channels were taken from Figure 2. For calculating the mean % block of rCaV1.2 current by 10 µM SKF, the mean % run-down during 6 min of control perfusion (black plot in B) was subtracted from the mean % block observed during 10 µM SKF perfusion (grey plot in B). Error bars indicate SEM, Ns are given in parentheses.

SKF inhibits recombinant P/Q-, N- and L-type calcium channels

Potent inhibition of LVA T-type Ca channels by SKF motivated us to test whether SKF also blocks recombinant neuronal HVA Ca channels. Examining HEK293 cells stably expressing rCaV2.1 and rCaV2.2 channels showed that 10 µM SKF nearly completely abolished both P/Q-type and N-type currents within approximately 4 min (Figure 3A,B, n = 6, 5 respectively). Blockade was only partially reversible as inhibition by 10 µM SKF did not exhibit 100% wash-out, and which may be due to partially irreversible drug binding and/or channel run-down over the longer time period required for wash-out of SKF (Figure 3A,B, right panels). Some run-down during perfusion was also observed for rCaV2.2 channels during control perfusion (Figure 3B, left panel, see 0–0.5 min). The macroscopic activation kinetics of rCaV2.1 currents were not altered during SKF blockade (compared at 50% inhibition; control, τ-act = 3.8 ± 0.7 ms, n = 6; 10 µM SKF, τ-act = 3.9 ± 0.4 ms, n = 6). Although the τ-inact was not calculated because of less apparent inactivation, the rCaV2.1 inactivation kinetics did not seem to differ during SKF perfusion (Figure 3A, right panel). The macroscopic activation and inactivation kinetics of rCaV2.2 currents were also not altered during SKF blockade (compared at 50% inhibition; control, τ-act = 1.6 ± 1.2 ms, n = 5; 10 µM SKF, τ-act = 1.4 ± 0.2 ms, n = 5; control, τ-inact = 81.4 ± 6.9 ms, n = 5; 10 µM SKF, τ-inact = 66.9 ± 6.5 ms, n = 5).

We also examined the effects of 10 µM SKF on a member of the third evolutionary branch of mammalian Ca channel family, the rCaV1.2 L-type. L-type Ca channel blockade by 50 µM SKF in smooth muscle cells was reported in the original SKF study by Merritt et al. (1990). In contrast to the relatively fast time-course of SKF block of P/Q-type channels, 10 µM SKF inhibited rCaV1.2 L-type channels slowly (t1/2 to maximum block: 1.5 ± 0.2 min (n = 6) for rCaV2.1 P/Q-type versus 3.3 ± 0.5 min (n = 6) for rCaV1.2 L-type, P < 0.01), reaching ∼90% inhibition in about 6 min (Figure 3C, left panel, grey curve, n = 6). Under our experimental conditions, we observed a slow constant run-down of rCaV1.2 currents over the same time period (Figure 3C, left panel, black curve, n = 7). Therefore, in order to estimate the mean % block of rCaV1.2 by 10 µM SKF (Figure 3D), we subtracted the mean % run-down during 6 min of control perfusion from the mean % block observed during 10 µM SKF perfusion (Figure 3D). Although we did not observe any reversibility of SKF block on rCaV1.2 Ca channels for up to 4 min of control perfusion, it is possible that the recovery is too slow and in part masked by slow channel run-down, and therefore is not observed in our experimental conditions. Alternatively, SKF may bind irreversibly to HVA Ca channels such as rCaV1.2, rCaV2.1 and rCaV2.2 (Figure 3, right panels). As for other HVA Ca channels, the activation kinetics of rCaV1.2 channels were not altered during SKF block (compared at 50% inhibition; control, τ-act = 1.1 ± 0.1 ms, n = 10; 10 µM SKF, τ-act = 1.3 ± 0.1 ms, n = 6), and the inactivation kinetics do not appear to be altered by SKF block (Figure 3B, right panel). Comparison of the mean percentage block by 10 µM SKF across the different major classes of voltage-gated Ca channels indicated extensive block by SKF of the three isoforms of T-type Ca channels (97–100%), the rCaV2.1 P/Q-type Ca channel (97%) and the rCaV2.2 N-type channel (99.2%). Blockade was slightly less for the rCaV1.2.L-type Ca channel (70%) (Figure 3D). As T-type Ca channels and TRPC channels share a subset of expression profiles and physiological roles, we further investigated the mechanism of block of SKF on the hCaV3.1 subtype of T-type channel. In order to rule out possible species-dependent differences in SKF sensitivity across various classes of voltage-gated Ca channels, we also compared SKF effects on hCaV3.1 versus rCaV3.1 (see next section).

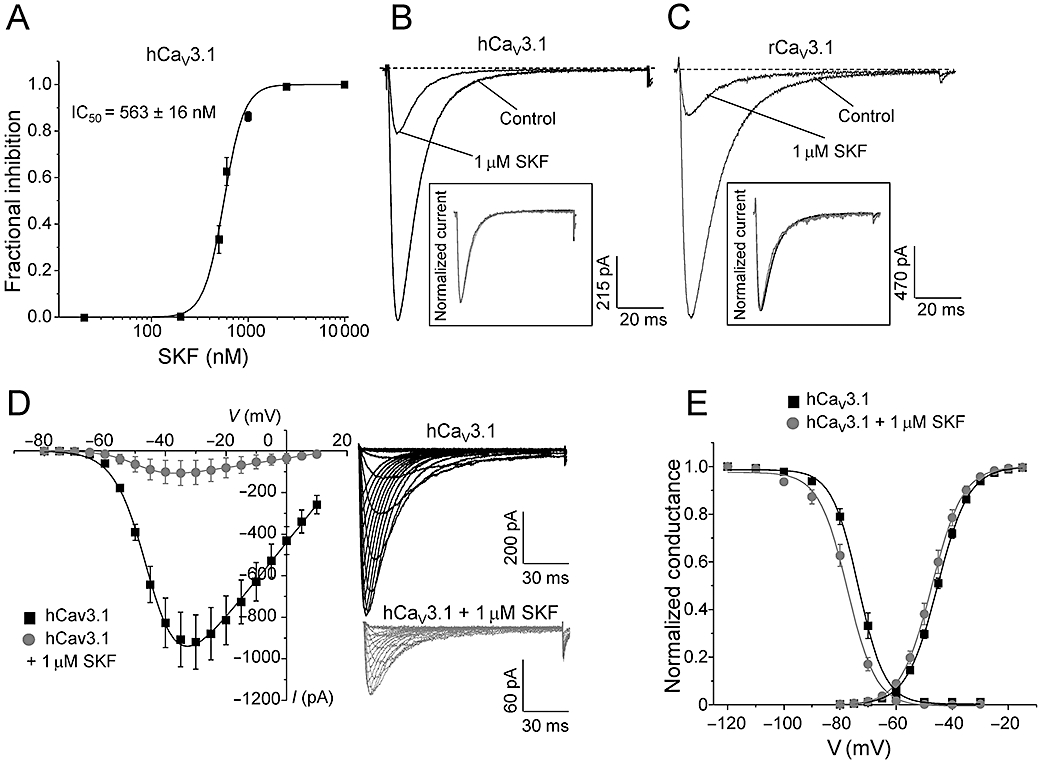

SKF inhibits hCaV3.1 T-type calcium channels dose-dependently and independent of the channel state

Examining the dose–response relationship of SKF block of hCaV3.1 channels showed a half maximal effect (IC50) at 563 ± 16 nM (n = 5–15, Figure 4A). The dose–response curve was quite steep (Hill coefficient 4.2 ± 0.7, n = 5–15), and block by SKF at lower concentrations was slow, taking up to 10–12 min to reach the maximal effect. Figure 4B inset shows representative normalized traces before and after 1 µM SKF block, confirming that SKF did not significantly alter hCaV3.1 activation or inactivation kinetics as previously described. The IC50 of SKF block on rCaV3.1 was very similar to hCaV3.1 (rCaV3.1, IC50: 579 ± 77 nM, n = 3–5, data not shown). As for hCaV3.1 channels, macroscopic activation and inactivation kinetics of rCaV3.1 channels were not altered during 1 µM SKF perfusion (Figure 4C, control, τ-act = 2.2 ± 0.2 ms, n = 6; 1 µM SKF, τ-act = 1.9 ± 0.1 ms, n = 6; control τ-inact = 15.6 ± 0.7 ms, n = 6; 1 µM SKF τ-inact = 15.0 ± 1.0 ms, n = 6). Finding no observable difference across species for CaV3.1 T-type Ca channels, we investigated the mechanism of SKF block on hCaV3.1 T-type Ca channels.

Figure 4.

Mechanism of block of SKF on hCaV3.1 calcium channels. (A) Dose–response curve of SKF on recombinant hCaV3.1 channels (n = 5–15). (B) Representative ICa during 120 ms depolarizations to Vmax (−30 mV) from a holding potential of −100 mV before and after perfusion of 1 µM SKF as indicated. Inset shows normalized traces for comparison of kinetics (see text for statistics). (C) Representative ICa during 120 ms depolarizations to Vmax (−30 mV) from a holding potential of −100 mV before and after perfusion of 1 µM SKF for rCaV3.1 as indicated. Inset shows normalized traces for comparison of kinetics (see text for statistics). (D) Mean I–V before and after 1 µM SKF block (control n = 8, 1 µM SKF n = 6). SKF inhibited hCaV3.1 currents at all test potentials. Right panel shows representative ICa traces (150 ms steps to potentials ranging from −80 to +10 mV in 5 mV increments) before (black) and after perfusion with 1 µM SKF (grey). (E) Normalized mean peak conductance at various test potentials before and after perfusion of 1 µM SKF. V0.5act in control conditions was not significantly different from after SKF block (see text for V0.5act statistics). Steady-state inactivation curves before and after 1 µM SKF block. Solid lines are fits to the Boltzmann relationship (see Methods). V0.5inact after 1 µM SKF was 4 mV more negative than control (see text for V0.5inact statistics).

The hCaV3.1-mediated Ca currents were inhibited at all potentials, indicative of a voltage-independent blocking mechanism (Figure 4D). The half-maximal voltage of activation (V0.5act) was unaffected by perfusion of 1 µM SKF (Figure 4D; control, V0.5act = −45.2 ± 0.5 mV, n = 13; 1 µM SKF, V0.5act = −47.3 ± 0.9 mV, n = 6). Unlike that for inhibitors that stabilize the inactivated state of Ca channels such as endogenous lipoamino acids (Barbara et al., 2009) and endocannabinoids (Chemin et al., 2001), SKF only slightly shifted the steady-state of inactivation to more negative potentials (Figure 4E; control, V0.5inact = −73.3 ± 1.0 mV, n = 9; 1 µM SKF, V0.5inact = −77.5 ± 1.0 mV, n = 6; P = 0.02). This small shift in the steady-state inactivation also slightly shifted the window current to more negative potentials. Although statistically significant, this small shift in the steady-state inactivation alone does not likely explain the marked inhibition of hCaV3.1 channels by SKF.

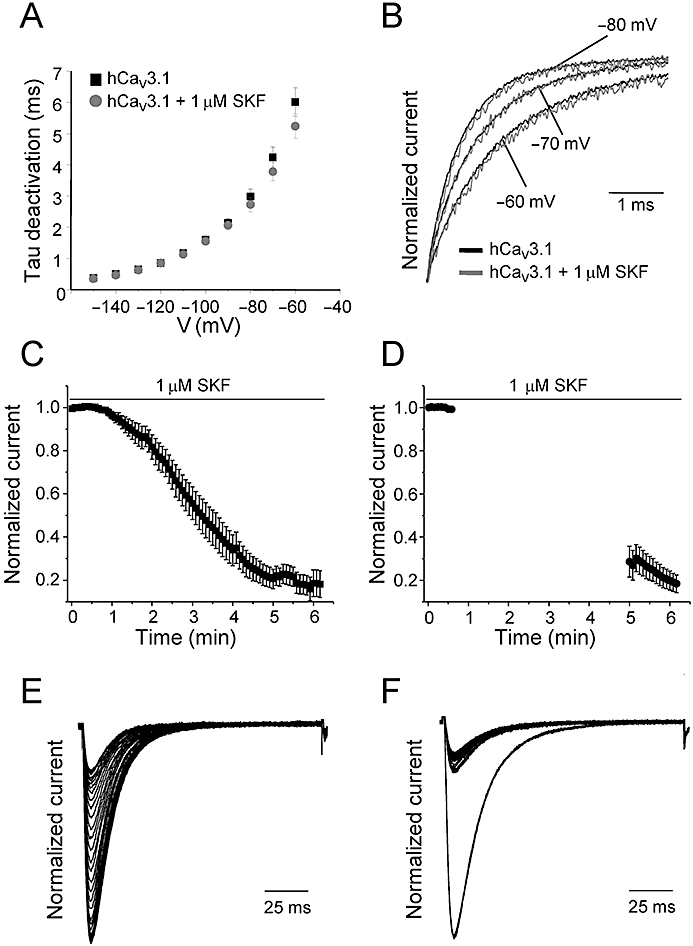

A hallmark of T-type Ca channels is their slow deactivation kinetics, which results in large tail currents that can underlie after depolarizing potentials and bursting behaviour. To examine the effects of SKF on the voltage dependence of deactivation kinetics, we measured tail currents over a range of membrane potentials from −150 to −60 mV after a 9 ms depolarizing pulse to −30 mV (Orestes et al., 2009). We did not observe any significant difference in the macroscopic deactivation kinetics of hCaV3.1 currents (Figure 5A,B).

Figure 5.

Voltage dependence of deactivation kinetics and tonic block of SKF on hCaV3.1 T-type calcium channels. (A) Mean values of tau deactivation plotted for hCaV3.1 before and after perfusion of 1 µM SKF. The values were obtained by a single exponential fit of the time-course of tail currents at the indicated test voltages. (B) Representative normalized tail current recorded during test voltages of −80, −70 and −60 mV (as indicated) before (black traces) and after perfusion of 1 µM SKF (grey traces). (C) Mean time-course of current inhibition during 0.2 Hz depolarizations to Vmax in the presence of 1 µM SKF (n = 8) to determine the use-dependent block of SKF on hCaV3.1 channels. Currents were elicited as described in Figure 2. The ICa reached steady-state inhibition in ∼6 min. (D) After 1 min of bath application of 1 µM SKF, the channels were held at −100 mV without depolarizations for ∼4 min. The depolarizations at 0.2 Hz were resumed after 4 min of rest period to determine tonic blockade of SKF on hCaV3.1 channels (n = 6). All data are presented as mean ± SEM. Representative normalized ICa traces during 6 min of 0.2 Hz depolarizations (E) or when the cells were held at −100 mV (F). Only alternate traces are shown for clarity.

SKF tonically inhibits hCaV3.1 T-type calcium channels

The largely voltage-independent mechanism of blockade prompted us to test whether SKF blocks hCaV3.1 channels in the closed/resting state. We examined the relative contributions of tonic and use-dependent block of hCaV3.1 currents by SKF. In one set of experiments, we used a protocol consisting of recording a train of depolarizations pulsed at a frequency of 0.2 Hz in the presence of 1 µM SKF until steady-state inhibition was reached (∼6 min in our conditions, Figure 5C,E) in order to assess the total inhibition by 1 µM SKF. In a separate set of experiments, 1 min of SKF application was followed by a rest period, during which time the holding potential was set to −100 mV (Figure 5D,F). At −100 mV, most hCaV3.1 channels would be in the closed state. After a 4 min resting period, an identical train of voltage clamp depolarizations was applied at a frequency of 0.2 Hz. Total blockade was considered to be the proportional difference between the first trace and the last trace after steady-state inhibition. The same amount of current inhibition (compared after 6 min of 1 µM SKF exposure) was observed under both conditions (0.2 Hz depolarizations, % inhibition = 81.2 ± 0.1%, n = 8; holding at −100 mV, % inhibition = 81.6 ± 0.04%, n = 6, Figure 5), suggesting that SKF inhibits T-type Ca channels in a tonic (state-independent) manner. Thus, it appears that SKF cannot be classified as an open channel blocker, and there is no strong evidence that it selectively stabilizes the inactivated state of hCaV3.1 channels. In this regard, the mechanism of action of SKF appears different from other LVA Ca channel blockers such as mibefradil (Jimenez et al., 2000) and isoflurane (Orestes et al., 2009). The tonic blockade indicates that SKF interacts with T-type Ca channels independent of their functional state, and thus T-type channels would be likely to be inhibited under most experimental conditions used to functionally measure TRPC channels and also independent of the applied stimulus.

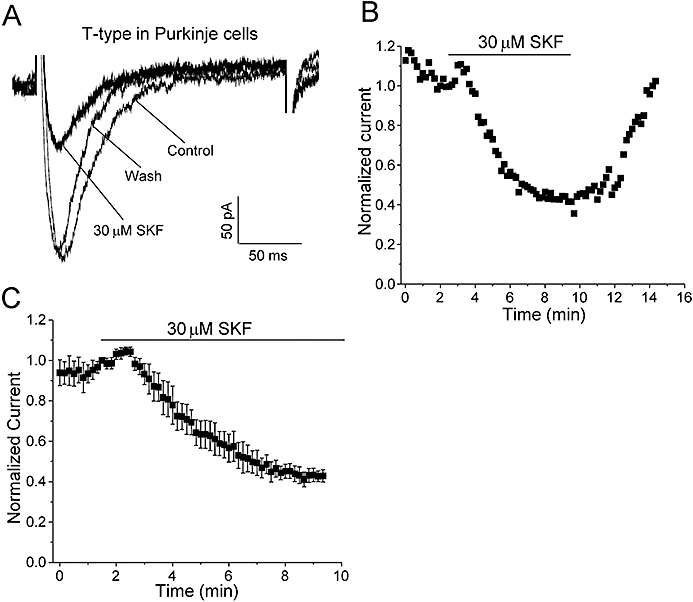

SKF inhibits native CaV3.1 T-type calcium currents in cerebellar PCs

Although heterologous systems such as HEK293 cells offer the advantage of studying specific drug actions in a defined environment, the observed effects may not reflect all the characteristics of the native system. In order to validate and complement the data from recombinant T-type Ca channels expressed in HEK293 cells, we studied the effects of SKF on rat cerebellar PCs that we have previously shown endogenously express CaV3.1 T-type channels (Hildebrand et al., 2009). To ensure that native T-type currents were well clamped and not contaminated by HVA Ca currents, we used depolarizing steps (average step = −43 ± 2 mV, n = 5) that elicited submaximal T-type Ca currents (Figure 6A; average T-type current amplitude = 238.2 ± 20.4 pA, n = 5). SKF inhibition was determined by applying the depolarizing pulses every 10 s. Figure 6A,B shows representative current traces and a representative time-course of inhibition of native CaV3.1 T-type currents by 30 µM SKF and subsequent wash-out respectively. Perfusion of 30 µM SKF reversibly inhibited 60.1 ± 1.8% (n = 5, P < 0.01) of the native T-type current reaching maximum inhibition in approximately 8 min of SKF application (Figure 6C). As observed for recombinant hCaV3.1 channels, SKF did not significantly alter macroscopic native T-type current activation or inactivation kinetics (control, τ-act = 4.0 ± 0.3 ms, n = 5; 30 µM SKF, τ-act = 3.7 ± 0.2 ms, n = 5; control τ-inact = 29.5 ± 1.6 ms, n = 5; 30 µM SKF τ-inact = 30.4 ± 2.9 ms, n = 5). In addition, perfusion of 50 µM SKF blocked over 90% of the native T-type current in PCs (data not shown). The higher SKF doses required for the inhibition of PC native T-type currents compared to exogenous CaV3.1 currents in HEK293 cells is a common phenomenon when comparing recombinant pharmacology data with in vitro slice data wherein both drug access and non-specific binding can alter access to the target. In addition, as native neuronal Ca currents likely represent a combination of functionally distinct splice variants, it is also possible that altered drug sensitivities between assay systems in part reflect differences in target molecules. Nevertheless, the doses used here on PCs are well within the range of SKF concentrations typically used to explore the roles of TRPC/RMCE in many native tissue preparations (Kim et al., 2003; Wang and Poo, 2005; Bomben and Sontheimer, 2008; Romero-Mendez et al., 2008).

Figure 6.

Effect of SKF on native T-type currents in cerebellar PCs. (A) Representative T-type current during 200 ms depolarizations to submaximal test potentials (as described in Methods) before, after perfusion of 30 µM SKF and after wash-out (as indicated). Currents were elicited by 200 ms depolarizations to −45 mV every 10 s from a holding potential of −75 mV (with a 500 ms prepulse to −90 mV to remove inactivation, as described in Methods). The apparent rates of channel activation and inactivation did not vary significantly before or during perfusion of SKF (for statistics, see text). (B) Representative time-course of T-type current inhibition by 30 µM SKF and subsequent wash-out with control solution. (C) Mean time-course of T-type current inhibition by 30 µM SKF (n = 5). The perfusion of 30 µM SKF inhibited 60.1 ± 1.8% of the T-type current during ∼8 min of SKF application.

Discussion

Numerous studies investigating the functional roles of TRPC channels and RMCE have utilized SKF blockade as part of their diagnostic criteria. SKF is often used in the concentration range of 2–100 µM with IC50 values (where reported) in the range of 5–30 µM (Merritt et al., 1990; Okada et al., 1998; Zhu et al., 1998; Wang and Poo, 2005; Bomben and Sontheimer, 2008; Romero-Mendez et al., 2008). Of note, reports show that in a wide variety of cell types including cerebellar PCs, midbrain dopamine neurons, vascular smooth muscle cells, as well as in various pathological states such as hypertrophic heart and gliomas, TRPC channels often co-exist with LVA T-type Ca channels (Kim et al., 2003; 2007; Cui et al., 2004; Panner et al., 2005; Ohba et al., 2007; Bomben and Sontheimer, 2008; Chiang et al., 2009). For example, in one study, inhibition of TRPC channels with 25 µM SKF in malignant gliomas resulted in growth arrest of glioma cells (Bomben and Sontheimer, 2008), while in another study the unequivocal role of T-type Ca channels in glioma and neuroblastoma proliferation using T-type blockers such as mibefradil was shown (Panner et al., 2005). Further, increased Ca entry into vascular smooth muscle from spontaneously hypertensive rats was reduced by 10 µM SKF and attributed to TRPC3 although up-regulation of T-type Ca channels has also been reported in this system (Self et al., 1994; Liu et al., 2009).

Structurally, SKF contains an alkylated imidazole ring which is also present in the class of compounds called phenylalkylamines known to block both HVA and LVA Ca channels (Figure 1). Interestingly, introduction of a substituted imidazole ring into dihydropyridines has been shown to increase their potency on Ca channels (Davood et al., 2006). While no reports concerning the specific interaction of the imidazole ring with the structural determinants of Ca channel inhibition have been published, it is possible that SKF inhibits Ca channels in a non-specific, allosteric manner. Although non-specific inhibitory effects of SKF on some HVA Ca channels (Merritt et al., 1990; Chan and Greenberg, 1991; Bannister et al., 2009) and other ion channels (Hong and Chang, 1994; Hong et al., 1994; Schwarz et al., 1994) have been reported, there has been no systematic analysis of the effects of SKF on the voltage-gated Ca channel family and there are no reports concerning T-type Ca channels. Given the co-existence of TRPC channels and other non-selective cation channels together with Ca channels in many native systems, and the non-specific effects of SKF, it is possible that in some studies wherein SKF was used to study RMCE, the roles of voltage-gated Ca channels have been underestimated and/or the contributions of non-selective cation channels might have been overestimated. In the present study, we have systematically determined the effect of SKF on T-, L- N- and P/Q-type Ca channels taking advantage of the HEK293 heterologous expression system, and have focused our studies on T-type Ca channels because of their expression and functional overlap with TRPC channels. We report for the first time that SKF blocks LVA T-type Ca channels even more potently than TRPC channels expressed in HEK293 cells [Figure 4A; IC50∼563 nM vs. IC50∼5 µM for TRPC3 (Zhu et al., 1998)]. At 10 µM, SKF also inhibited HVA P/Q-type (Figure 3A), N-type (Figure 3B) and L-type (Figure 3C) Ca channels by 96.9, 99.2 and 70% respectively.

While HEK293 cells offer many advantages in studying specific drug interactions on exogenously expressed targets, they are likely to differ from native systems because of the expression of specific alternative splice variants, interacting proteins and other factors that might affect channel biophysical properties, pharmacology and modulation. Block of TRPC1 channels by 30–50 µM SKF in cerebellar PCs has revealed their contribution to the slow EPSP generated following mGluR1 receptor activation (Kim et al., 2003). In our examination of PCs, we found that 30 µM SKF blocked approximately 60% of the native T-type current (Figure 6A,C). A recent study from our lab indicated that native CaV3.1 T-type Ca channels were potentiated by mGluR1 receptor activation in PC spines and underlie fast Ca signalling at parallel fibre–PC synapses (Hildebrand et al., 2009). Thus, in native tissues wherein T-type channels co-exist with TRPC channels, they may both exhibit similar sensitivities to SKF and also might overlap in their contributions towards Ca-dependent signalling pathways. Of note, the concentration of SKF required to block either T-type Ca channels (Figure 6) or TRPC channels (Kim et al., 2003) in cerebellar PCs was much higher compared to doses required to block recombinant Ca channels (Figure 2) or recombinant TRPC channels (Zhu et al., 1998) expressed in HEK293 cells. It is possible that splice variant differences across species together with other factors such as non-specific drug binding in part explain the different drug potencies when recording native currents. However, our experiments comparing sensitivity of recombinant hCaV3.1 and rCaV3.1 channels expressed in HEK293 cells to SKF (Figure 4B,C) support the view that any species differences alone do not account for the difference in the drug sensitivity.

Based upon our results, it is possible that the full contributions of T-type Ca channels have not been explored in some studies. SKF inhibition of T-type Ca channels was found to be only mildly voltage dependent (Figures 4D,E and 5), suggesting that SKF is likely to block T-type Ca channels under basal conditions such as those used to determine resting Ca influxes and spontaneous Ca oscillations. For example, 10 µM SKF has been used to identify the contribution of non-selective cation channels in maintaining intracellular Ca levels and spontaneous firing in midbrain dopamine neurons (Kim et al., 2007). The window current resulting from T-type Ca channels is well within the range of the resting membrane potential of these neurons. Thus, their contributions to the resting Ca levels should not be ruled out. Indeed, experiments with inorganic ions such as Ni2+ and Cd2+ (known to block T-type Ca channels) support this notion (Kim et al., 2007). Additionally, the reported inhibition of proliferation of glioma cells by 25 µM SKF may well have resulted from the additive inhibition of both TRPC and T-type Ca channels (Bomben and Sontheimer, 2008). Emerging roles of TRPC and T-type Ca channels in sensing hypoxia also further emphasize the overlapping expression and function of these channels, and that non-specific blockers such as SKF may not be the optimal choice to study TRPC channels in these tissues (Carabelli et al., 2007; Meng et al., 2008).

Taken together, the present study provided evidence that not only did SKF block HVA Ca channels at typically utilized test concentrations, but even more potently inhibited T-type Ca channels than the intended TRPC target. In light of these data, blockade by SKF alone should not be the defining criterion for assessing and interpreting the functional roles of TRPC channels in native systems.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by an operating grant (10677) from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to T.P.S. and a Canada Research Chair in Biotechnology and Genomics-Neurobiology. A.S. is supported by a fellowship from Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. We thank Janette Mezeyova and David Parker at Neuromed Pharmaceuticals for kindly providing HEK293 cell lines stably expressing calcium channel subtypes.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- Ca

calcium

- HVA

high-voltage-activated

- LVA

low-voltage-activated

- PC

Purkinje cell

- RMCE

receptor-mediated calcium entry

- SKF96365

1{β-[3-(4-methoxyphenyl)propoxyl]-4-methoxyphenethyl}-1H-imidazole hydrochloride

- SOCE

store-operated calcium entry

- TRPC

transient receptor potential canonical type

Conflicts of interest

The authors do not report any conflicts of interest concerning the contents of the present paper.

References

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 4th edn. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:S1–S254. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister RA, Pessah IN, Beam KG. The skeletal L-type Ca(2+) current is a major contributor to excitation-coupled Ca(2+) entry. J Gen Physiol. 2009;133:79–91. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200810105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbara G, Alloui A, Nargeot J, Lory P, Eschalier A, Bourinet E, et al. T-type calcium channel inhibition underlies the analgesic effects of the endogenous lipoamino acids. J Neurosci. 2009;29:13106–13114. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2919-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bomben VC, Sontheimer HW. Inhibition of transient receptor potential canonical channels impairs cytokinesis in human malignant gliomas. Cell Prolif. 2008;41:98–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2007.00504.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulay G, Zhu X, Peyton M, Jiang M, Hurst R, Stefani E, et al. Cloning and expression of a novel mammalian homolog of Drosophila transient receptor potential (Trp) involved in calcium entry secondary to activation of receptors coupled by the Gq class of G protein. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:29672–29680. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.47.29672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carabelli V, Marcantoni A, Comunanza V, de Luca A, Diaz J, Borges R, et al. Chronic hypoxia up-regulates alpha1H T-type channels and low-threshold catecholamine secretion in rat chromaffin cells. J Physiol. 2007;584:149–165. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.132274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J, Greenberg DA. SK & F 96365, a receptor-mediated calcium entry inhibitor, inhibits calcium responses to endothelin-1 in NG108-15 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;177:1141–1146. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)90658-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemin J, Monteil A, Perez-Reyes E, Nargeot J, Lory P. Direct inhibition of T-type calcium channels by the endogenous cannabinoid anandamide. EMBO J. 2001;20:7033–7040. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.24.7033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang CS, Huang CH, Chieng H, Chang YT, Chang D, Chen JJ, et al. The Ca(v)3.2 T-type Ca(2+) channel is required for pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy in mice. Circ Res. 2009;104:522–530. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.184051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham DE, Runnels LW, Strubing C. The TRP ion channel family. Nat Rev. 2001;2:387–396. doi: 10.1038/35077544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui G, Okamoto T, Morikawa H. Spontaneous opening of T-type Ca2+ channels contributes to the irregular firing of dopamine neurons in neonatal rats. J Neurosci. 2004;24:11079–11087. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2713-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davood A, Mansouri N, Rerza Dehpour A, Shafaroudi H, Alipour E, Shafiee A. Design, synthesis, and calcium channel antagonist activity of new 1,4-dihydropyridines containing 4-(5)-chloro-2-ethyl-5-(4)-imidazolyl substituent. Arch Pharm. 2006;339:299–304. doi: 10.1002/ardp.200600013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doering CJ, Zamponi GW. Molecular pharmacology of high voltage-activated calcium channels. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2003;35:491–505. doi: 10.1023/b:jobb.0000008022.50702.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand ME, Isope P, Miyazaki T, Nakaya T, Garcia E, Feltz A, et al. Functional coupling between mGluR1 and Cav3.1 T-type calcium channels contributes to parallel fiber-induced fast calcium signaling within Purkinje cell dendritic spines. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9668–9682. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0362-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong SJ, Chang CC. Facilitation of nicotinic receptor desensitization at mouse motor endplate by a receptor-operated Ca2+ channel blocker, SK & F 96365. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;265:35–42. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong SJ, Lin WW, Chang CC. Inhibition of the sodium channel by SK & F 96365, an inhibitor of the receptor-operated calcium channel, in mouse diaphragm. J Biomed Sci. 1994;1:172–178. doi: 10.1007/BF02253347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez C, Bourinet E, Leuranguer V, Richard S, Snutch TP, Nargeot J. Determinants of voltage-dependent inactivation affect mibefradil block of calcium channels. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00153-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SJ, Kim YS, Yuan JP, Petralia RS, Worley PF, Linden DJ. Activation of the TRPC1 cation channel by metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR1. Nature. 2003;426:285–291. doi: 10.1038/nature02162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Choi YM, Jang JY, Chung S, Kang YK, Park MK. Nonselective cation channels are essential for maintaining intracellular Ca2+ levels and spontaneous firing activity in the midbrain dopamine neurons. Pflugers Arch. 2007;455:309–321. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0279-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiselyov K, Xu X, Mozhayeva G, Kuo T, Pessah I, Mignery G, et al. Functional interaction between InsP3 receptors and store-operated Htrp3 channels. Nature. 1998;396:478–482. doi: 10.1038/24890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Freyer AM, Hall IP. Bradykinin activates calcium-dependent potassium channels in cultured human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L898–L907. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00461.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Yang D, He H, Chen X, Cao T, Feng X, et al. Increased transient receptor potential canonical type 3 channels in vasculature from hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2009;53:70–76. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.116947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason MJ, Mayer B, Hymel LJ. Inhibition of Ca2+ transport pathways in thymic lymphocytes by econazole, miconazole, and SKF 96365. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:C654–C662. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.3.C654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng F, To WK, Gu Y. Role of TRP channels and NCX in mediating hypoxia-induced [Ca(2+)](i) elevation in PC12 cells. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2008;164:386–393. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt JE, Armstrong WP, Benham CD, Hallam TJ, Jacob R, Jaxa-Chamiec A, et al. SK & F 96365, a novel inhibitor of receptor-mediated calcium entry. Biochem J. 1990;271:515–522. doi: 10.1042/bj2710515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran MM, Xu H, Clapham DE. TRP ion channels in the nervous system. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:362–369. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohba T, Watanabe H, Murakami M, Takahashi Y, Iino K, Kuromitsu S, et al. Upregulation of TRPC1 in the development of cardiac hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:498–507. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada T, Shimizu S, Wakamori M, Maeda A, Kurosaki T, Takada N, et al. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of a novel receptor-activated TRP Ca2+ channel from mouse brain. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10279–10287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orestes P, Bojadzic D, Chow RM, Todorovic SM. Mechanisms and functional significance of inhibition of neuronal T-type calcium channels by isoflurane. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75:542–554. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.051664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panner A, Cribbs LL, Zainelli GM, Origitano TC, Singh S, Wurster RD. Variation of T-type calcium channel protein expression affects cell division of cultured tumor cells. Cell Calcium. 2005;37:105–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Mendez AC, Algara-Suarez P, Sanchez-Armass S, Mandeville PB, Meza U, Espinosa-Tanguma R. Intracellular Ca2+-store depletion triggers a Na+ influx via SOCs in guinea pig tracheal smooth muscle. FASEB J. 2008;22:1206.1. 1_MeetingAbstracts. [Google Scholar]

- Rychkov G, Barritt GJ. TRPC1 Ca(2+)-permeable channels in animal cells. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2007;179:23–52. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-34891-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz G, Droogmans G, Nilius B. Multiple effects of SK & F 96365 on ionic currents and intracellular calcium in human endothelial cells. Cell Calcium. 1994;15:45–54. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(94)90103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self DA, Bian K, Mishra SK, Hermsmeyer K. Stroke-prone SHR vascular muscle Ca2+ current amplitudes correlate with lethal increases in blood pressure. J Vasc Res. 1994;31:359–366. doi: 10.1159/000159064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GX, Poo MM. Requirement of TRPC channels in netrin-1-induced chemotropic turning of nerve growth cones. Nature. 2005;434:898–904. doi: 10.1038/nature03478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Jiang M, Birnbaumer L. Receptor-activated Ca2+ influx via human Trp3 stably expressed in human embryonic kidney (HEK)293 cells. Evidence for a non-capacitative Ca2+ entry. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:133–142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]