Abstract

Migraine affects as many as 37% of reproductive-age women in the United States. Hormonal contraception is the most frequently used form of birth control during the reproductive years, and given the significant proportion of reproductive-age women affected by migraine, there are several clinical considerations that arise when considering hormonal contraceptives in this population. In this review, key differences among headache, migraine, and migraine with aura, as well as strict diagnostic criteria, are described. The recommendations of the World Health Organization and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists regarding hormonal contraception initiation and continuation in women with these diagnoses are emphasized. Finally, information about the effect of hormonal fluctuations on headache is provided with recommendations regarding contraception counseling in patients who experience headache while taking hormonal contraception.

Key Words: Migraine without aura, Migraine with aura, Hormonal contraceptives, Stroke, Estrogen, Progesterone

Forty-three percent of women in the United States are affected by migraine.1 The prevalence of migraine increases with age: 22% of women age 20 to 24 years, 28% age 25 to 29 years, 33% age 30 to 34 years, and as many as 37% of women age 35 to 39 years are affected.1 During these reproductive years, hormonal contraception is the most prevalent form of birth control used, with 43% of contracepting US women using hormone-containing pills, patches, ring, shots, implants, or intrauterine devices.2 Given the significant proportion of reproductive-age women affected by migraine, there are several clinical considerations that arise when considering hormonal contraceptives in this population. Key considerations include physician selection of appropriate candidates for initiation of hormone-containing contraceptives, and decision making about method continuation in patients complaining of headache while taking hormonal contraceptives.

It is critical for physicians prescribing hormonal contraception to distinguish among common headache, migraine, and migraine with aura, to decide when the use of estrogen-containing contraception is appropriate. In addition, headache is a frequently reported side effect of hormonal contraception and a leading reason cited for contraceptive discontinuation.3 Contraceptive discontinuation is thought to account for 20% of the 3.5 million unplanned pregnancies in the United States annually.4 Separate from the risk of unintended pregnancy, women who discontinue hormonal contraceptives due to headaches are unable to reap the noncontraceptive benefits of these medications, including relief of chronic pelvic pain, and endometrial protection in polycystic ovary syndrome and other anovulatory states.

This review outlines key differences among headache, migraine, and migraine with aura, and describes the strict diagnostic criteria. Society recommendations for hormonal contraception initiation and continuation in women with these diagnoses are emphasized. Finally, we provide information about the effect of hormonal fluctuations on headache, and recommendations regarding contraception counseling in patients who experience headache while taking hormonal contraception.

Diagnosis of a Headache

Migraine Without Aura (Previously Known as Common or Simple Migraine)

Migraine headache is distinguished from other headaches as a benign and recurring syndrome of headache, nausea, vomiting, and/or other symptoms of neurologic dysfunction. According to the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention study, the 1-year prevalence of migraine in women is about 17.1%, and highest at 24.4% in reproductive-age women.5 The 1-year prevalence rate for migraine without aura, the common migraine, is 11% in women, making it the most frequent subset of migraine diagnoses.6 To make the diagnosis of migraine, neurologists follow the International Classification of Headache Disorders II (ICHD II) criteria, the official criteria of the International Headache Society (IHS).7

Migraine With Aura (Previously Known as Complex Migraine)

Migraine with aura has a 1-year prevalence rate of 5% in women.6 Aura specifically describes a complex of neurologic symptoms that occur just before or with the onset of migraine headache, and most often resolves completely before the onset of headache. Neurologists have long hypothesized that a phenomenon called cortical spreading depression (waves of altered brain function triggered by changes in cellular excitability) is responsible for migraine aura.8 Visual symptoms are the most common aura, and are a feature of 99% of auras.9 According to the ICHD II criteria, migraine with aura is a recurrent disorder manifesting in attacks of reversible focal neurologic symptoms that develop gradually over 5 to 20 minutes, and last for less than 60 minutes. Headache with the features of migraine without aura usually follows the aura, although less commonly, the headache may lack migrainous features or be completely absent.7 The IHS Diagnostic Criteria for Migraine with Aura are depicted in Table 1.

Table 1.

The IHS Diagnostic Criteria for Migraine

| Without Aura | ||

| Recurring headache with at least 5 attacks fulfilling the following criteria: | ||

| Attacks last 4–72 h (untreated or unsuccessfully treated) | ||

| At least 2 of the following: | ||

| –Unilateral location | ||

| –Pulsating quality | ||

| –Moderate or severe pain intensity | ||

| –Aggravated by routine physical activity | ||

| At least 1 of the following during attack: | ||

| –Nausea and/or vomiting | ||

| –Photophobia and phonophobia | ||

| –Not attributed to another disorder | ||

| With Aura | ||

| Must fulfill criteria for migraine listed above, and in addition, at least 2 attacks fulfilling the following criteria: | ||

| Aura consisting of at least 1 of the following, but no motor weakness: | ||

| 1. Fully reversible visual symptoms including positive features (flickering lights, spots, or lines) and/or negative features (ie, loss of vision) | ||

| 2. Fully reversible sensory symptoms including positive features (ie, pins and needles) and/or negative features (ie, numbness) | ||

| 3. Fully reversible dysphasic speech disturbance | ||

| At least 2 of the following other characteristics: | ||

| 1. Homonymous visual symptoms and/or unilateral sensory symptoms | ||

| 2. At least 1 aura symptom develops gradually over ≥ 5 min, and/or different aura symptoms occur in succession over ≥ 5 min | ||

| 3. Each symptom lasts ≥ 5 and < 60 min | ||

| Headache fulfilling the criteria for migraine without aura begins during the aura or follows aura within 60 min | ||

| Not attributed to another disorder | ||

IHS, International Headache Society.

Risk of Stroke in Women With Migraines

Migraine is an independent risk factor for ischemic stroke.10–19 However, the absolute risk of ischemic stroke is low in women of reproductive age, with reported incidence rates ranging from 5 to 11.3 per 100,000 woman-years.20,21 Often, a history of migraine may be the only significant risk factor for stroke in women younger than age 35 years, whereas more traditional atherogenic risk factors for ischemic stroke (ie, hypertension, dyslipidemia) dominate after age 35, with history of migraine losing relevance in this older cohort.17 Although 2 case-control studies suggest the association between migraine and stroke may be limited to women younger than age 45 years,17,18 a large prospective cohort study of women age ≥ 45 years found that active migraine with aura was associated with a significantly increased risk of major cardiovascular disease, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and death due to ischemic cardiovascular disease.14

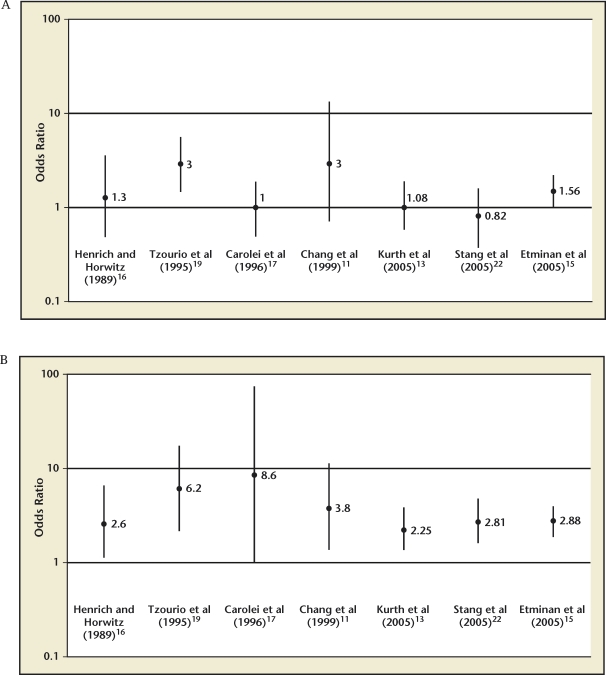

Studies offer conflicting evidence with respect to risk of ischemic stroke in migraine without aura.11,13,14,16,22 There is, however, a preponderance of evidence that migraine with aura is associated with a significantly elevated relative risk (RR) of ischemic stroke.11–18,22 A meta-analysis of 11 case-control studies and 3 cohort studies suggest that the RR of ischemic stroke in all migraineurs is 2.16 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.89–2.48); migraine with aura carried a RR of 2.27 (95% CI, 1.61–3.19) for ischemic stroke, and migraine without aura had a RR of 1.83 (95% CI, 1.06–3.15) of ischemic stroke.15 Figure 1 depicts the odds ratios (OR) for ischemic stroke in the setting of migraine without aura and migraine with aura.

Figure 1.

(A) Migraine without aura and stroke risk. (B) Migraine with aura and stroke risk. Reproduced with permission from MacGregor EA.6

Combination Estrogen-Progesterone Contraceptives and Stroke Risk

Does Combination Estrogen-Progesterone Contraception Increase Stroke Risk Regardless of Migraine Status?

Combination contraceptives have been found to be an independent risk factor for ischemic stroke in some studies.23–27 However, a large population-based, case-control study, and a pooled analysis of data from 2 US case-control studies found that low-estrogen contraceptives (ie, preparations containing < 50 µg of estrogen) were not associated with an increased risk of stroke in the absence of migraine.21,28

Does Combination Estrogen-Progesterone Contraception Increase Stroke Risk in Women With Migraine?

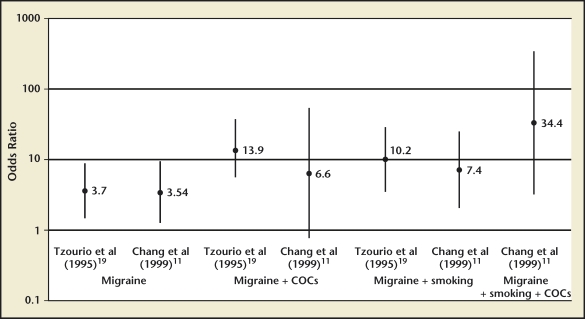

No studies have been adequately powered to directly compare stroke risk in migraineurs with aura taking combination estrogen-progesterone contraceptives with that of migraineurs without aura taking combination contraception. Many studies have reported increased odds of stroke in migraineurs who use combination hormonal contraception, particularly among active smokers (Figure 2).11,12,19,23,28,29 Reported ORs for ischemic stroke in migraineurs using combination contraception range from 2 to nearly 14, compared with nonusers. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 9 studies found that the pooled RR of ischemic stroke in women age < 45 years with migraine ± aura was 3.6, and the risk of ischemic stroke was further increased to 7.2 among women currently using oral contraceptives.30

Figure 2.

Effect of combined oral contraceptives (COC), migraine, and smoking on stroke risk. Reproduced with permission from MacGregor EA.6

A case-control study by Tzourio and colleagues compared 72 women aged 18 to 44 years presenting with first ischemic stroke with 173 hospital-matched controls. They found the odds of ischemic stroke were nearly 14 times higher in migrainous women using oral contraceptives.19 In a pooled analysis of data from 2 US case-control studies, Schwartz and colleagues studied 175 women aged 18 to 44 years with ischemic stroke and 1191 controls. They found that women with a history of migraine and current low-dose contraceptive use (< 50 µg estrogen) had twice the odds of stroke compared with nonusers of combination contraception.28 Chang and colleagues compared 291 women aged 20 to 44 years with ischemic, hemorrhagic, or unclassified arterial stroke to 736 age- and hospital-matched controls. They found that women with migraine using low-dose oral contraceptives (< 50 µg estrogen) had nearly 7 times the odds of ischemic stroke, and this risk increased nearly exponentially if the women were smokers (Figure 2).11 Another case-control study by MacClellan and colleagues examined the effect of smoking on stroke risk in migraineurs, comparing 386 women ages 15 to 49 years with first ischemic stroke with 614 age- and ethnicity-matched controls. This study found that migraineurs with aura who were current combination contraceptive users and smokers had 7 times higher odds of stroke compared with migraineurs with aura who did not smoke and did not use oral contraceptives, and 10 times higher odds of stroke compared with women without migraine who did not smoke and did not use oral contraceptives.12

Finally, it is important to note that at least 2 studies found that the use of combination contraceptives did not further elevate the risk of ischemic stroke in women with migraines.14,31

The Impact of the Estrogen Dose on Stroke Risk

Although there is a preponderance of evidence that pill formulations containing ≥ 50 µg of ethinyl estradiol are associated with an elevated risk of ischemic stroke compared with formulations with < 50 µg, the data are not as clear regarding risk of stroke associated with 20 µg versus 30 or 35 µg formulations. A large, Danish population-based, case-control study by Lidegaard and colleagues found that, among women with a history of migraine headaches, use of combination contraception containing 50 µg of ethinyl estradiol increased odds of stroke nearly three-fold, whereas use of 30 to 40 µg pill formulations increased odds of stroke nearly 2-fold.23,29 In the few studies that examined ischemic stroke risk associated with 20 µg ethinyl estradiol formulations compared with 30 to 40 µg formulations, the data are conflicting. Tzourio and colleagues reported a lower OR of stroke in 20 µg formulations (OR 1.7 compared with OR of 2.7 for 30–40 µg formulations),19 whereas Lidegaard and colleagues reported a similar OR of ischemic stroke for 20 µg (OR 1.7) and 30 to 40 µg (OR 1.6) formulations.24 Further research with modern hormonal contraceptive methods is needed to draw conclusions regarding the impact of estrogen dose on stroke risk.

The Impact of Progesterone on Stroke Risk

Similarly, there are conflicting data regarding whether type of progesterone influences stroke risk in low-estrogen formulations. The IHS Task Force concludes in their consensus statement that there is no difference in the ischemic stroke risk between low-estrogen formulations containing second-generation progestogens (eg, ethynodiol diacetate, levonorgestrel, and norethisterone) versus third-generation progestogens (desogestrel, gestodene, norgestimate).20

Although studies are limited, there is no evidence to suggest that progesterone-only contraceptives increase the risk of stroke, even in women who have multiple risk factors (including age µ 35 years, tobacco use, and migraines with aura). The World Health Organization (WHO) considers progesterone-only pills, implants, intrauterine devices, and injectables to be Category 2 for women who have migraines with aura, regardless of a woman’s age, smoking status, or comorbidities.32 There is general consensus that progesterone-only contraceptives are safe for use in women who have migraine with aura, even in the presence of other risk factors for stroke (Table 2).29,33,34

Table 2.

WHO Medical Eligibility for Combination Estrogen-Progesterone Contraceptive Use: Women With Headache and Migraine

| Category | Description | Headache/Migraine-Specific Recommendation |

| 1 | A condition for which there is no restriction for the use of the contraceptive method | Non-migrainous headache |

| 2 | A condition where the advantages of using the method generally outweigh the theoretical or proven risks | Migraine without aura, age <35 y, nonsmoker |

| Non-migrainous headaches develop after initiating CC | ||

| 3 | A condition where the theoretical or proven risks generally outweigh the advantages | Migraine with aura, age ≥35 y Migraines without aura develop after initiating CC |

| 4 | A condition which represents an unacceptable health risk if the contraceptive is used | Migraines with aura, any age |

| Migraines with aura develop after initiating CC |

CC, combination estrogen-progesterone contraception; WHO, World Health Organization.

Professional Recommendations Regarding Hormone Use in Women With Migraines

Due to the preponderance of evidence that migraine with aura is associated with an elevated stroke risk compared with migraine without aura, and the assumption that this risk would be further elevated by use of estrogen-containing contraceptives, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the WHO have considered migraines with aura to be an absolute contraindication to the use of combined hormonal contraception.34,35 The IHS Task Force on Combined Oral Contraceptives and Hormone Replacement Therapy, however, has slightly more liberal guidelines, stating, “There is a potentially increased risk of ischemic stroke in women with migraine who are using combination hormonal contraception and have additional risk factors which cannot easily be controlled, including migraine with aura. One must individually assess and evaluate these risks.”20 Thus, use of combination hormonal contraception in women experiencing migraine with aura is not strictly contraindicated by the IHS. In assessing the risk of estrogen-containing contraception or hormone therapy in patients who have migraine and migraine with aura, the IHS suggests that other independent risk factors for stroke also be assessed and taken into consideration, including age > 35 years, tobacco use, dyslipidemia, family history of arterial disease age < 45 years, and other relevant medical comorbidities (ie, obesity [body mass index > 30], diabetes, known vascular disease). Table 3 summarizes the recommendations of the WHO, ACOG, and the IHS Task Force regarding combined estrogen-progesterone contraceptive use in women with headache and migraine.

Table 3.

WHO/ACOG/IHS Task Force Recommendations Regarding Combined Estrogen-Progesterone Contraceptive (CC) Use in Women With Headache and Migraine

| Variable | ACOG | WHO | IHS |

| Headache (non-migrainous) | No contraindication | No contraindication | No contraindication |

| Migraine Without Aura | |||

| Age < 35 y | No contraindication | No contraindication | Individualized assessment of risk |

| Age ≥ 35 y | Risk usually outweighs benefits | Risk usually outweighs benefits | Individualized assessment of risk, depends on number of risk factorsa |

| Smokers | Risk usually outweighs benefits | Risk usually outweighs benefits | Women with migraine who smoke should stop smoking before starting combination contraception |

| Additional risk factors for ischemic stroke: hypertension, obesity, diabetes, hyperlipidemia | Risk usually outweighs benefits | Risk usually outweighs benefits | Individualized assessment of risk, depends on number of risk factors.b Risk factors such as hypertension and hyperlipidemia should be treated |

| Migraine With Aura | |||

| Age < 35 y | Risk unacceptable | Risk unacceptable | Individualized assessment of risk, depends on number of risk factors |

| Age ≥ 35 y | Risk unacceptable | Risk unacceptable | Individualized assessment of risk, depends on number of risk factors |

| Smokers | Risk unacceptable | Risk unacceptable | Women with migraine who smoke should stop smoking before starting combination contraception |

| Additional risk factors for ischemic stroke: hypertension, obesity, diabetes, hyperlipidemia | Risk unacceptable | Risk unacceptable | Individualized assessment of risk, depends on number of risk factors. Risk factors such as hypertension and hyperlipidemia should be treated |

Risk factors include age >35 y, ischemic heart disease or cardiac disease with embolic potential, diabetes mellitus, family history of arterial disease at age <45 y, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, migraine aura, obesity (body mass index >30), smoking, systemic diseases associated with stroke including sickle cell disease and connective tissue disorders.

Consider non-ethinyl estradiol methods in women at increased risk of ischemic stroke, particularly those who have multiple risk factors. ACOG, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; IHS, International Headache Society; WHO, World Health Organization.

Special Considerations

New-Onset Migraines Following Initiation of Exogenous Hormones

Exogenous hormone-induced headache is defined as either new onset of headache or exacerbation of existing headache within the first 3 months of initiating hormonal therapy.7 There is evidence that patients who have migraines with aura have 4 times the odds of developing worsening headaches after initiation of combination oral contraceptives, compared with women who have migraines without aura.36,37 Exogenous hormone-induced headaches are also more common in women age > 35 years and women with a family history of migraines.38 Headache associated with combination contraceptive use typically will improve as use continues. A Scandinavian study suggests that if a headache or migraine occurs in the first cycle of combination hormonal contraceptive use, there is only a 1 in 3 risk of headache reoccurrence in the second cycle, and a 1 in 10 chance of headache in the third cycle.6

However, a recent systematic review suggests that studies on exogenous hormone-induced headache are generally of low quality, have studied older contraceptive formulations with higher estrogen doses that do not reflect those in current use, have failed to distinguish migraine from other headaches, and have failed to control for baseline estimates of migraine incidence or prevalence, both of which are high and increase with age in women. The majority of studies did not include control groups of women using nonhormonal or no contraception, to capture the baseline incidence of headache in reproductive-aged women. The review concludes that we lack reliable evidence about the effects of hormonal contraception on headache and migraine.39 Until better data are available, ACOG and the IHS Task Force recommend reevaluation or discontinuation of combination contraceptive use for women who develop escalating severity/frequency of headaches, particularly outside of the pill-free interval; new-onset migraine with aura symptoms; or nonmigrainous headaches persisting beyond 3 months of use.20,35 For these women, consideration should be given to a progesterone-only or hormone-free method.

The effect of exogenous progesterone on headache and migraine is not well understood. It has been noted that migraines may occur during episodes of uterine bleeding in women taking progestogens, even if ovulation is suppressed.6,40 However, it is unclear whether this effect is secondary to estrogen fluctuation due to incomplete suppression of ovulation, or increased prostaglandin within the endometrium.6 Because progesterone-only methods may not suppress ovulation, estrogen fluctuations can occur. It has been noted that, in women taking progestogen-only pills, headache and migraine improve most often in those who have achieved amenorrhea.40,41 However, even when ovulation is completely suppressed, estrogen fluctuations have still been noted in women using progesterone-only methods.42 Third-generation progestogens may be associated with fewer headaches per cycle, compared with second-generation progestogens.43

Estrogen-Withdrawal Headache

In women who are not taking hormonal contraception, estrogen withdrawal during the late luteal phase is a well-recognized trigger of headache and menstrual migraines.44 Estrogen-withdrawal headaches have also been observed in women taking estrogen-containing contraceptives as well as postmenopausal women taking estrogen-containing hormone therapy.45 Estrogen may not be the only culprit in perimenstrual headaches; increased prostaglandin release during menses has also been implicated in headaches that begin a few days before the onset of menses and end a few days after menses start.6,46,47 Estrogen-withdrawal headaches are defined as headaches that appear within the first 5 days of estrogen cessation, start after daily exogenous estrogen exposure for 3 weeks or more, and typically resolve within 3 days of their onset.7 Estrogen-withdrawal headaches may also be associated with other hormone withdrawal symptoms, including breast tenderness and pelvic pain. Additional estradiol during the perimenstrual interval can effectively reduce or prevent estrogen-withdrawal headaches.48 Reducing the hormone-free interval to 3 to 4 days instead of 7 days, or eliminating the hormone-free interval entirely has been successful in the prevention of estrogen-withdrawal headaches.37,45,49

Menstrual Migraines

Menstrual migraines are a subset of estrogen-withdrawal headaches, typically occurring 2 days before the onset of menses, lasting through the third day of menstrual bleeding. The association of migraines with menses must occur in at least two-thirds of cycles to be classified as menstrual migraines.7 Although menstrual migraines by definition fulfill the IHS criteria for migraine, they typically are not associated with an aura, even in women who experience migraine with aura at other times in their cycle.50 Before attempting hormone supplementation, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), triptans, and ergot derivatives may be attempted as initial prophylaxis and abortive therapy for women who experience menstrual migraines.51–53 A small, randomized, placebo-controlled trial found that 550 mg naproxen twice daily for migraine prophylaxis, beginning 7 days before onset of menses and continued for 13 days, significantly decreased the frequency, severity, and duration of menstrual migraines compared with placebo.53 Triptans have been extensively studied in treatment of menstrual migraine, and found to be superior to placebo.54 Rizatriptan and sumatriptan have been the best studied. A small, randomized, placebo-controlled trial found that mefenamic acid—also effective in treatment of dysmenorrhea—is superior to placebo in the treatment of menstrual migraine.55 An NSAID/triptan combination may be another first-line therapy in women with menstrual migraines and dysmenorrhea.56 For women whose menstrual migraines do not respond to nonhormonal therapy, supplemental estradiol during the late luteal phase of the menstrual cycle (day 28, 29) through cycle day 3 may reduce the severity and frequency of menstrual migraines.57

Strategies to avoid hormone withdrawal and consequent migraine include continuous use of combination contraception, or use of estrogen alone during the perimenstrual period. Use of percutaneous estradiol gel beginning 48 hours prior to anticipated migraine attack and used for 7 days was found to be superior to placebo in double-blind controlled studies.47,58–60 A transdermal estrogen patch has also been shown to be effective in preventing menstrual migraines.57 The minimum effective dose of estrogen in a transdermal patch has been shown to be 0.1 mg/d. Of note, patches, gels, and other hormone supplementation to prevent menstrual migraines should begin no more than 2 days before the anticipated onset of menses; starting estrogen supplementation early (ie, 6 days before the first day of menses) has been associated with an increased incidence of migraine after the estrogen supplementation is withdrawn.47

Pregnancy and Migraine

Pregnancy is both a high-progesterone and a high-estrogen state in which ovulation is completely suppressed. The elevated estrogen and progesterone levels of pregnancy decline suddenly after delivery. Thus, migraine and headache symptoms might be expected to improve during pregnancy and potentially to recur during the puerperium, if one believes the hypothesis that menstrual migraines occur when estrogen levels decline rapidly after sustained exposure to estrogen throughout the menstrual cycle. There are conflicting data in this regard. The majority of available literature suggests that women typically experience improvement or no change in frequency or severity of migraines during pregnancy.61 The percentage of women whose migraines improve in pregnancy ranges vastly in the literature, from 18% to 86%.62 To date, no objective criteria have been established to determine which women are likely to have improvement of headaches/migraine in pregnancy. It is a consistent finding that migraine with aura is less likely to improve in pregnancy,36,63,64 perhaps related to increased endothelial reactivity in these patients.62 Findings from a large, population-based study of Norwegian women suggest that headache, both migrainous and nonmigrainous, is less prevalent in pregnancy, although this association was only true in the third trimester, and in primigravidas. The decreased prevalence of headaches in pregnancy was not seen in primiparous or multiparous pregnant women.65

Conclusions

Migraine affects as many as 37% of reproductive-age women in the United States. Hormonal contraception is the most frequently used form of birth control during reproductive years, with up to 43% of US women selecting a hormonal method. A preponderance of evidence suggests that migraine, particularly migraine with aura, is associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke, and that this risk may be further elevated in the setting of combined estrogen-progesterone contraceptive use. There are no studies that directly compare the risk of stroke in migraineurs with and without aura using estrogen-containing contraception. The majority of studies regarding stroke risk in women with migraine using combination contraception are retrospective case-control studies. Thus, the data are subject to recall bias and classification bias, and must be interpreted with caution.

ACOG and the WHO state that the use of combination estrogen-progesterone contraception may be considered for women with migraine headache only if they do not experience aura, do not smoke, are otherwise healthy, and are younger than age 35 years. The IHS Task Force does not state that migraine with aura is an absolute contraindication to use of combination contraception, and suggests that decisions regarding contraceptive choice be made on a case-by-case basis.

Headaches associated with combination hormonal contraceptives typically will improve as use continues. Reevaluation or discontinuation of combination hormonal contraception is advised for women who develop escalating severity/frequency of headaches, new-onset migraine with aura, or nonmigrainous headaches persisting beyond 3 months of use. For patients with estrogen-withdrawal headaches and menstrual migraines, reducing the hormone-free interval to 3 to 4 days, or eliminating the hormone-free interval entirely, has been demonstrated to reduce the severity, frequency, and duration of headache. For menstrual migraines, traditional abortive and prophylactic therapies for migraine, including naproxen and mefenamic acid, triptans, and ergot alkaloids have also been shown to be more effective than placebo. These methods can be first-line therapy, particularly in women for whom estrogen use is contraindicated.

In considering the risks of combination estrogen-progesterone hormonal contraception in women with migraine, it is critical to keep the cardiovascular risks of pregnancy (often the result of lack of effective contraception) in mind. The age-adjusted incidence of venous thromboembolic phenomena is 4 to 50 times as great in pregnant and peripartum women compared with nonpregnant women.66–70 Pregnancy, delivery, and the postpartum period are also associated with a significantly elevated RR of both ischemic (RR = 8.7) and hemorrhagic (RR = 28.3) stroke, with greatest risk in the postpartum period.71 Thus, pregnancy likely poses a far greater risk to women’s cardiovascular health than does the use of estrogen-containing contraception, even in the high-risk group of migraineurs with aura.

Main Points.

Migraine headache is distinguished from other headaches as a benign and recurring syndrome of headache, nausea, vomiting, and/or other symptoms of neurologic dysfunction. Migraine with aura specifically describes a complex of neurologic symptoms that occur just before or with the onset of migraine headache, and most often resolves completely before the onset of headache.

A preponderance of evidence suggests that migraine, particularly migraine with aura, is associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke, and that this risk may be further elevated with combined estrogen-progesterone contraceptive use. The majority of studies are retrospective case-control studies; thus, the data are subject to recall bias and classification bias, and must be interpreted with caution.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the World Health Organization state that the use of combination estrogen-progesterone contraception may be considered for women with migraine headache only if they do not experience aura, do not smoke, are otherwise healthy, and are age < 35 years. However, the International Headache Society Task Force does not indicate that migraine with aura is an absolute contraindication for use of combination contraception, and suggests that decisions regarding contraceptive choice should be made on a case-by-case basis based on other independent risk factors for stroke.

Headaches associated with combination hormonal contraceptives typically will improve as use continues. Reevaluation or discontinuation of combination hormonal contraception is advised for women who develop escalating severity/frequency of headaches, new-onset migraine with aura, or nonmigrainous headaches persisting beyond 3 months of use.

References

- 1.Stewart WF, Wood C, Reed ML, et al. Cumulative lifetime migraine incidence in women and men. Cephalalgia. 2008;28:1170–1178. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finer LB, Frohwirth LF, Dauphinee LA, et al. Reasons U.S. women have abortions: quantitative and qualitative perspectives. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2005;37:110–118. doi: 10.1363/psrh.37.110.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenberg MJ, Waugh MS. Oral contraceptive discontinuation: a prospective evaluation of frequency and reasons. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:577–582. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenberg MJ, Waugh MS, Long S. Unintended pregnancies and use, misuse and discontinuation of oral contraceptives. J Reprod Med. 1995;40:355–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, et al. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007;68:343–349. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000252808.97649.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacGregor EA. Migraine and use of combined hormonal contraceptives: a clinical review. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2007;33:159–169. doi: 10.1783/147118907781004750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society, authors. The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(suppl 1):9–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2003.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charles A. Advances in the basic and clinical science of migraine. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:491–498. doi: 10.1002/ana.21691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Russell MB, Olesen J. A nosographic analysis of the migraine aura in a general population. Brain. 1996;119(Pt 2):355–361. doi: 10.1093/brain/119.2.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merikangas KR, Fenton BT, Cheng SH, et al. Association between migraine and stroke in a large-scale epidemiological study of the United States. Arch Neurol. 1997;54:362–368. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1997.00550160012009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang CL, Donaghy M, Poulter N. Migraine and stroke in young women: case-control study. The World Health Organisation Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. BMJ. 1999;318:13–18. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7175.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacClellan LR, Giles W, Cole J, et al. Probable migraine with visual aura and risk of ischemic stroke: the stroke prevention in young women study. Stroke. 2007;38:2438–2445. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.488395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurth T, Slomke MA, Kase CS, et al. Migraine, headache, and the risk of stroke in women: a prospective study. Neurology. 2005;64:1020–1026. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000154528.21485.3A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurth T, Gaziano JM, Cook NR, et al. Migraine and risk of cardiovascular disease in women. JAMA. 2006;296:283–291. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Etminan M, Takkouche B, Isorna FC, Samii A. Risk of ischaemic stroke in people with migraine: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ. 2005;330:63–66. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38302.504063.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henrich JB, Horwitz RI. A controlled study of ischemic stroke risk in migraine patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 1989;42:773–780. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(89)90075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carolei A, Marini C, De Matteis G. History of migraine and risk of cerebral ischaemia in young adults. The Italian National Research Council Study Group on Stroke in the Young. Lancet. 1996;347:1503–1506. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90669-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tzourio C, Iglesias S, Hubert JB, et al. Migraine and risk of ischaemic stroke: a case-control study. BMJ. 1993;307:289–292. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6899.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tzourio C, Tehindrazanarivelo A, Iglésias S, et al. Case-control study of migraine and risk of ischaemic stroke in young women. BMJ. 1995;310:830–833. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6983.830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bousser MG, Conard J, Kittner S, et al. Recommendations on the risk of ischaemic stroke associated with use of combined oral contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy in women with migraine. The International Headache Society Task Force on Combined Oral Contraceptives & Hormone Replacement Therapy. Cephalalgia. 2000;20:155–156. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2000.00035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petitti DB, Sidney S, Bernstein A, et al. Stroke in users of low-dose oral contraceptives. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:8–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199607043350102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stang PE, Carson AP, Rose KM, et al. Headache, cerebrovascular symptoms, and stroke: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Neurology. 2005;64:1573–1577. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000158326.31368.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lidegaard Ø. Oral contraception and risk of a cerebral thromboembolic attack: results of a case-control study. BMJ. 1993;306:956–963. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6883.956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lidegaard Ø, Kreiner S. Contraceptives and cerebral thrombosis: a five-year national casecontrol study. Contraception. 2002;65:197–205. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(01)00306-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gillum LA, Mamidipudi SK, Johnston SC. Ischemic stroke risk with oral contraceptives: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2000;284:72–78. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heinemann LA, Lewis MA, Spitzer WO, et al. Thromboembolic stroke in young women. A European case-control study on oral contraceptives. Transnational Research Group on Oral Contraceptives and the Health of Young Women. Contraception. 1998;57:29–37. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(97)00204-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ischaemic stroke and combined oral contraceptives: results of an international, multicentre, case-control study, authors. WHO Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. Lancet. 1996;348:498–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwartz SM, Petitti DB, Siscovick DS, et al. Stroke and use of low-dose oral contraceptives in young women: a pooled analysis of two US studies. Stroke. 1998;29:2277–2284. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.11.2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lidegaard Ø. Oral contraceptives, pregnancy and the risk of cerebral thromboembolism: the influence of diabetes, hypertension, migraine and previous thrombotic disease. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;102:153–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1995.tb09070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schürks M, Rist PM, Bigal ME, et al. Migraine and cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b3914. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Donaghy M, Chang CL Poulter N on behalf of the European Collaborators of the World Health Organisation Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease, authors; Steroid Hormone Contraception, authors. Duration, frequency, recency, and type of migraine and the risk of ischaemic stroke in women of childbearing age. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:747–750. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.73.6.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization, authors. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use. 3rd edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.MacGregor EA. Menstrual migraine: a clinical review. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2007;33:36–47. doi: 10.1783/147118907779399684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cardiovascular disease and use of oral and injectable progestogen-only contraceptives and combined injectable contraceptives, authors. Results of an international, multicenter, case-control study. World Health Organization Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. Contraception. 1998;57:315–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology, authors. Practice Bulletin ACOG. No. 73: Use of hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1453–1472. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200606000-00055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Granella F, Sances G, Pucci E, et al. Migraine with aura and reproductive life events: a case control study. Cephalalgia. 2000;20:701–707. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2000.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loder EW, Buse DC, Golub JR. Headache and combination estrogen-progestin oral contraceptives: integrating evidence, guidelines, and clinical practice. Headache. 2005;45:224–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Larsson-Cohn U, Lundberg PO. Headache and treatment with oral contraceptives. Acta Neurol Scand. 1970;46:267–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1970.tb05792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Loder EW, Buse DC, Golub JR. Headache as a side effect of combination estrogen-progestin oral contraceptives: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(3 Pt 1):636–649. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Somerville BW, Carey HM. The use of continuous progestogen contraception in the treatment of migraine. Med J Aust. 1970;1:1043–1045. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1970.tb84395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davies P, Fursdon-Davies C, Rees MC. Progestogens for menstrual migraine. J Br Menopause Soc. 2003;9:134. doi: 10.1177/136218070300900315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Croxatto HB, Mäkaräinen L. The pharmacodynamics and efficacy of Implanon. An overview of the data. Contraception. 1998;58:91S–97S. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(98)00118-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fotherby K. Twelve years of clinical experience with an oral contraceptive containing 30 micrograms ethinyloestradiol and 150 micrograms desogestrel. Contraception. 1995;51:3–12. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(94)00010-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.MacGregor EA, Frith A, Ellis J, et al. Incidence of migraine relative to menstrual cycle phases of rising and falling estrogen. Neurology. 2006;67:2154–2158. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000233888.18228.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sulak PJ, Scow RD, Preece C, et al. Hormone withdrawal symptoms in oral contraceptive users. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:261–266. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00524-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.MacGregor EA, Hackshaw A. Prevalence of migraine on each day of the natural menstrual cycle. Neurology. 2004;63:351–353. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000133134.68143.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.MacGregor EA, Frith A, Ellis J, et al. Prevention of menstrual attacks of migraine: a double-blind placebo-controlled crossover study. Neurology. 2006;67:2159–2163. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000249114.52802.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.MacGregor EA, Hackshaw A. Prevention of migraine in the pill-free interval of combined oral contraceptives: a double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study using natural oestrogen supplements. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2002;28:27–31. doi: 10.1783/147118902101195974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Edelman A, Gallo MF, Nichols MD, et al. Continuous versus cyclic use of combined oral contraceptives for contraception: systematic Cochrane review of randomized controlled trials. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:573–578. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Johannes CB, Linet MS, Stewart WF, et al. Relationship of headache to phase of the menstrual cycle among young women: a daily diary study. Neurology. 1995;45:1076–1082. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.6.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Facchinetti F, Bonellie G, Kangasniemi P, et al. The efficacy and safety of subcutaneous sumatriptan in the acute treatment of menstrual migraine. The Sumatriptan Menstrual Migraine Study Group. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86:911–916. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00288-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Solbach MP, Waymer RS. Treatment of menstruation-associated migraine headache with subcutaneous sumatriptan. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82:769–772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sances G, Martignoni E, Fioroni L, et al. Naproxen sodium in menstrual migraine prophylaxis: a double-blind placebo controlled study. Headache. 1990;30:705–709. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1990.hed3011705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ashkenazi A, Silberstein S. Menstrual migraine: a review of hormonal causes, prophylaxis and treatment. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2007;8:1605–1613. doi: 10.1517/14656566.8.11.1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Al-Waili NS. Treatment of menstrual migraine with prostaglandin synthesis inhibitor mefenamic acid: double-blind study with placebo. Eur J Med Res. 2000;5:176–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mannix LK, Martin VT, Cady RK, et al. Combination treatment for menstrual migraine and dysmenorrhea using sumatriptan-naproxen: two randomized controlled trials. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:106–113. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181a98e4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Massiou H, MacGregor EA. Evolution and treatment of migraine with oral contraceptives. Cephalalgia. 2000;20:170–174. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2000.00038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pringsheim T, Davenport WJ, Dodick D. Acute treatment and prevention of menstrually related migraine headache: evidence-based review. Neurology. 2008;70:1555–1563. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000310638.54698.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.de Lignières B, Vincens M, Mauvais-Jarvis P, et al. Prevention of menstrual migraine by percutaneous oestradiol. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;293:1540. doi: 10.1136/bmj.293.6561.1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dennerstein L, Morse C, Burrows G, et al. Menstrual migraine: a double-blind trial of percutaneous estradiol. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1988;2:113–120. doi: 10.3109/09513598809023619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Menon R, Bushnell CD. Headache and pregnancy. Neurologist. 2008;14:108–119. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e3181663555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Contag SA, Mertz HL, Bushnell CD. Migraine during pregnancy: is it more than a headache? Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5:449–456. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kelman L. Women’s issues of migraine in tertiary care. Headache. 2004;44:2–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.04003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Scharff L, Marcus DA, Turk DC. Headache during pregnancy and in the postpartum: a prospective study. Headache. 1997;37:203–210. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1997.3704203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Aegidius K, Zwart JA, Hagen K, Stovner L. The effect of pregnancy and parity on headache prevalence: the Head-HUNT study. Headache. 2009;49:851–859. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Marik PE, Plante LA. Venous thromboembolic disease and pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2025–2033. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Greer IA. Thrombosis in pregnancy: maternal and fetal issues. Lancet. 1999;353:1258–1265. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10265-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kujovich JL. Hormones and pregnancy: thromboembolic risks for women. Br J Haematol. 2004;126:443–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Heit JA, Kobbervig CE, James AH, et al. Trends in the incidence of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy or postpartum: a 30-year population-based study. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:697–706. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-10-200511150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Prevention of venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, authors. NIH Consensus Development. JAMA. 1986;256:744–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kittner SJ, Stern BJ, Feeser BR, et al. Pregnancy and the risk of stroke. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:768–774. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609123351102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]