Abstract

Background

Preserving patient dignity is a sentinel premise of palliative care. This study was conducted to gain a better understanding of factors influencing preservation of dignity in the last chapter of life.

Methods

We conducted an open-ended written survey of 100 multidisciplinary providers (69% response rate) and responses were categorized to identify 2 main themes, 5 subthemes, and 10 individual factors that were used to create the preservation of dignity card-sort tool (p-DCT). The 10-item rank order tool was administered to a cohort of community dwelling Filipino Americans (n = 140, age mean = 61.3, 45% male and 55% female). A Spearman correlation matrix was constructed for all the 10 individual factors as well as the themes and subthemes based on the data generated by the subjects.

Results

The individual factors were minimally correlated with each other indicating that each factor was an independent stand-alone factor. The median, 25th and 75th percentile ranks were calculated and “s/he has self-respect” (intrinsic theme, self-esteem subtheme) emerged as the most important factor (mean rank 3.0 and median rank 2.0) followed by “others treat her/him with respect” (extrinsic theme, respect subtheme) with a mean rank = 3.6 and median = 3.0.

Conclusion

The p-DCT is a simple, rank order card-sort tool that may help clinicians identify patients' perceptions of key factors influencing the preservation of their dignity in the last chapter of life.

Introduction

Death and dying are often understood and experienced within a complex cultural web1–4 that includes culturally determined beliefs, rituals and practices, family values, power structures, and acculturation status (when relevant). While language and socioeconomic barriers are recognized as clear concerns for minority populations,5–7 diverse health and illness belief systems are gaining increasing recognition as important factors that influence health care of patients who have a diverse cultural heritage.8,9 Irrespective of their ethnic and cultural background, preservation of dignity at life's end has been long acknowledged to be a key priority10–14 for all persons. Preservation and augmentation of patient dignity may increase the patient's sense of value and meaning.

The concept of dignity is a very subjective one and much influenced by an individual's personal, cultural, social, and spiritual constructs. It has also been recognized that patient dignity does not exist in a vacuum15 and that it is greatly influenced by the perceptions and behaviors of the clinicians caring for them. We propose that the first step in conserving patient dignity is to prevent or mitigate the erosion of dignity. In an earlier study,16 the factors thought to influence erosion of dignity at life's end were identified and used to create a simple dignity card-sort tool (DCT) that can be easily used at the bedside. As the next step, the current study was undertaken to: (1) explore both patients' and multidisciplinary health professionals' perceptions of factors influencing preservation of patient dignity at life's end and (2) to create and validate the “preservation of dignity card-sort tool” (p-DCT), a simple card sort tool that busy clinicians can use at the bedside to gain a better understanding of an individual's perception of factors that preserve their dignity. All phases of this study were approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board.

Phase 1: Preliminary Work: Open-Ended Surveys of Health Professionals

Early exploratory work involved conversations with multiethnic patients and families about the concepts of dignity, death with dignity, and erosion of dignity at life's end. They endorsed the need for this line of research, stated that health professionals' perceptions and behaviors are likely to have a significant influence on patients' perception of their dignity and recommended that we first analyze the health professionals' perceptions. The exploratory work with patients and families led to identification of the study questions which were then used to conduct an open-ended written survey of 100 multidisciplinary (from the disciplines of nursing, medicine, psychology, social work, chaplaincy, occupational therapy, and massage therapy) clinicians (69% response rate) in geriatrics and palliative care to identify key factors thought to influence preservation and erosion of dignity at life's end. The survey responses were transcribed and analyzed using the NVivo software (QSR International Pty Ltd [QSR] ABN 47 006 357 213, Melbourne, Australia). Transcripts of sessions were analyzed according to grounded theory using an open coding approach. Two main themes/domains 5 subdomains/and 10 individual dignity factors were identified independently by two of the authors (V.S.P. and A.M.N.) based on frequency of occurrence and salience. Actual words and phrases used by participants were used to name subthemes17 as much as possible. Relationships between themes and subthemes were proposed based on patterns emerging from extensive transcript review. Any conflicts were resolved by a series of discussions mediated by another author (H.C.K.) until consensus was obtained.

Phase 2: Creating the Underlying Theoretical Model

Based on the themes that emerged from the data and based on review of existing literature,18–21, dignity was broadly classified as intrinsic or extrinsic. All people are born with intrinsic dignity and most are treated in a manner that bestows extrinsic dignity upon them. Thus:

Extrinsic dignity can be thought to rest outside the person. Extrinsic dignity may thus be greatly influenced by the way others (including clinicians) treat the person.

Intrinsic dignity is thought to be an innate property/possession of the individual. For example, newborn infants who could not have developed dignity through personal performance are thought to intrinsically possess dignity.22 Similarly all persons including patients with cognitive impairment and those who are completely dependent on others for all their activities of daily living do possess intrinsic human dignity.

As mentioned before, everyone is born with intrinsic dignity and should be treated by others with extrinsic dignity. Thus in an ideal situation every individual possesses both intrinsic and extrinsic dignity.

Proposed model for dignity

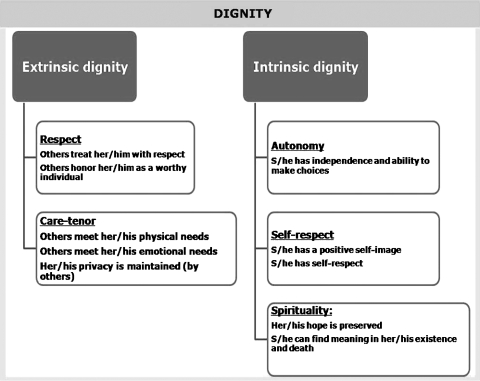

Based on the survey responses, extrinsic dignity and intrinsic dignity were determined to be the two main themes. Extrinsic dignity was further categorized into the following subthemes: (1) respect and (2) care-tenor (the attitude others demonstrate when interacting with the patient). Extrinsic dignity was thought to be preserved when others treated the subject with respect, met the subject's physical and emotional needs, honored the subject's wishes, and made attempts to maintain their privacy/confidentiality. Intrinsic dignity was further categorized into the following sub-themes: (1) autonomy, (2) self-esteem, and (3) spirituality. Intrinsic dignity was thought to be preserved when the subject had self-esteem, when they were able to exercise autonomy and if their sense of hope and meaning was preserved (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Theoretical model of themes and subthemes of factors influential in preservation of dignity.

Phase 3: Creation of the p-DCT

The 10 individual dignity preservation factors (Table 1) were used to create a card sort rank order tool. Refer to Appendix A for user instructions for the p-DCT.

Table 1.

Factors Influential in Preserving Dignity at Life's End

| Dignity theme (first order category) | Dignity subtheme (second order category) | A dying person's dignity is preserved when: | Mean rank | SD | Median rank | 25th percentile rank | 75th percentile rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extrinsic | Respect | Others treat her/him with respect | 3.6 | 2.4 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 5.0 |

| Others honor her/him as a worthy individual | 5.3 | 2.6 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 7.0 | ||

| Care-tenor | Others meet her/his physical needs | 7.6 | 2.5 | 9.0 | 6.0 | 9.5 | |

| Others meet her/his emotional needs | 7.2 | 2.5 | 8.0 | 5.0 | 9.0 | ||

| Her/his privacy is maintained (by others) | 5.6 | 2.4 | 5.5 | 4.0 | 7.5 | ||

| Intrinsic | Autonomy | S/he has independence and ability to make choices | 4.9 | 2.5 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 7.0 |

| Self-esteem | S/he has a positive self-image | 5.9 | 2.3 | 6.0 | 4.0 | 8.0 | |

| S/he has self-respect | 3.0 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 4.0 | ||

| Spirituality | Her/his hope is preserved | 5.3 | 2.6 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 7.0 | |

| S/he can find meaning in her/his existence and death | 6.7 | 3.1 | 7.0 | 4.0 | 10.0 |

SD, standard deviation.

Accordingly, each tool item was written on a separate card and the 10 cards were shuffled thoroughly to create a random order. Next we identified a large Filipino American community in the San Francisco Bay Area and recruited a convenience sample of subjects. Personal health information was not collected and thus we cannot comment on the health status of these subjects. The card sort tool was administered to a sample of 140 Filipino Americans (age mean = 61.3, standard deviation [SD] = 7.6 and median = 60.0; 45% male and 55% female). Each participant was requested to arrange (stack) the cards in the order of most important factor (top most card) to least important factor (bottom most card) influential in preservation of dignity at life's end.

Results

In an attempt to reduce the length of the p-DCT tool, a Spearman correlation matrix were constructed for all the ten individual factors as well as the themes and sub-themes based on the data generated by the subjects (n = 140 Filipino Americans). Eight of the 10 factors were only minimally correlated with each other, indicating that each factor was an independent stand-alone factor. The following two extrinsic factors from the “care-tenor” subtheme were moderately correlated with each other:

Others meet her/his physical needs

Others meet her/his emotional needs.

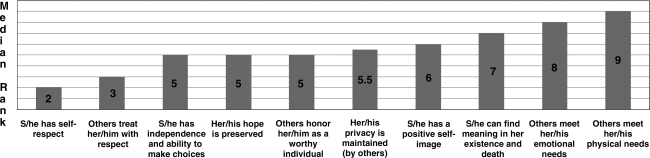

However, as these two factors were only moderately correlated (Spearman correlation coefficient = 0.39 and p <0.0001) with each other, we refrained from combining the two factors into a single item. Thus the final p-DCT tool retained all ten original items (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Rank order of factors influential in preserving dignity at life's end in a cohort of Filipino Americans.

Next, the mean, standard deviation, median, 25th, and 75th percentile ranks were computed (Table 1). “S/he has self-respect” (intrinsic theme, self-esteem subtheme) emerged as the most important factor (mean rank 3.0 and median rank 2.0) followed by “others treat her/him with respect” (extrinsic theme, respect subtheme) with a mean rank = 3.6 and median = 3.0 (Fig. 2). “S/he has a positive self-image” (intrinsic theme, self-esteem subtheme) ranked seventh of the 10 items (mean rank 5.9, median rank = 6). In reviewing the differences between the concepts of “self-respect” and “self-image” note that self-image is defined in the Merriam-Webster Dictionary23 dictionary as “one's conception of oneself or of one's role.” Self-respect is defined as “regard for one's own standing or position" or "respect for oneself as a human being.” Practically speaking, self-image is thought to be how a person views herself and self-respect is how a person treats herself. Being treated with respect by others (extrinsic dignity) ranked as the second most important factor. Interestingly, for this cohort of Filipino Americans, “others meet her/his physical needs” emerged as the least important factor (mean rank = 7.6, median = 9.0).

Discussion

In summary, we have empirically explored the concept of dignity at the end of life with both patients and multidisciplinary health professionals. We have developed and initially validated the p-DCT, a rank order card-sort tool to assess perceptions of factors influential in the preservation of dignity at life's end in a cohort of community dwelling Filipino Americans.

Surprisingly, the factor “others meet her/his physical needs” (extrinsic theme, care-tenor subtheme) was ranked to be the least important factor in preserving dignity. However, our previous work16 on erosion of dignity revealed that the cohort of patients studied felt that receiving poor medical care and dying in pain led to erosion of their dignity. We thus posit that practical and concrete factors like excellent pain and symptom management as well as access to quality palliative care prevent erosion of dignity, and also bolster more abstract factors like self-esteem and self-respect, which are instrumental in preserving and augmenting personal dignity.

Our study is noteworthy for the following reasons: first, we have systematically identified the factors that are influential in preserving dignity and used these to create a simple card-sort tool that can be administered rapidly at the bedside by clinicians or family members; second, we have demonstrated that the factors that influence perception of preservation of dignity are different from those that cause perception of erosion of dignity. Third, to the best our knowledge, our study is the first to systematically validate the concept of dignity at life's end in a cross-cultural cohort of Filipino Americans.

There are several limitations to the generalizability of this study. First, the study subjects were community dwelling and were not necessarily facing a serious life-limiting illness. Therefore, their opinions about the factors influencing and preserving dignity at life's end was probably conceptual (as opposed to experiential). Second, this is a cross-sectional study. We acknowledge that the perception of factors leading to preservation of dignity may be subject to change depending on proximity to death and better studied longitudinally through the trajectory of serious life limiting illness. Third, the study subjects belonged to a single ethnic group (Filipino Americans). While this is a strength of the study, it is also a limitation in that the findings related to the rank ordering component may be specific to this ethnicity. However, it is to be noted that the first phase of the study that yielded the theoretical model and the ten item tool was based on a multiethnic cohort of patients and families and thus the p-DCT tool can be used on subjects belonging to any ethnic and cultural group. Fourth, while the exploratory phase of this study involved patients and families in several informal discussions, phase one involved only multidisciplinary clinicians.

Before recommending this tool for more general use, it should be validated by others in various clinical settings and on larger samples of ethnically diverse populations to test the generalizability of our results. Also, multiple factors like age, level of education, income, acculturation status, state of health, socioeconomic status as well as past experiences with the health care system are likely to influence perceptions of dignity and these variables need to be studied. It would also be desirable to track the changes in patient responses over time while concurrently tracking key variables like pain, nonpain symptoms, functional status, emotional and spiritual distress, and quality of life. Finally, and most importantly, it is also crucial to ascertain whether the determination of patients' perceptions of factors influential in the preservation of dignity is of any clinical utility and whether such information will result in clinician behaviors that will preserve patients' extrinsic dignity.

Conclusion

The population of ethnic minorities and especially ethnic elders is growing in leaps and bounds. As a result of profound demographic changes in the United States with the population of minority elders increasing significantly, clinicians will increasingly care for patients from cultural backgrounds other than their own. Clinicians caring for aging and seriously ill patients need a sound knowledge base regarding patients' cultural values, beliefs and practices regarding death and dying, in order to be able to provide effective care that preserves and augments patient dignity. Effective palliation of pain and other distressing symptoms and provision of quality medical care prevents erosion of patient dignity. Treating patients with respect and maximizing the tenor of care provided preserves and augments dignity at life's end. The p-DCT is a promising tool that may help clinicians identify key factors influencing preservation of dignity in adult palliative care patients. We hope that such identification will lead to a better understanding of the concept of dignity across cultures and thereby result in culturally effective care that that will help preserve and augment patient dignity at life's end.

Appendix

Appendix A.

User Instructions for the Preservation of Dignity Card-Sort Tool(p-DCT)

| Please take a set of 12 identical 4 × 6 size index cards. Listed below is the tool trigger statement and the 10 items in the final tool. Write 1 item per card. Keep the cards that state “most important factor” and “least important factor” separately. Shuffle the other 10 cards a few times to create a random order. Instruct the subject to rank (stack) the 10 cards in the order of importance, with the most important factor to be placed first (on the top), the next one second, and so on. Finally instruct the subject to place the card that states “most important factor” on the top of the stack and the card that states “least important factor” at the bottom of the stack and hand it to the health professional. Care should be taken not to misplace the “most important factor” and the “least important factor” cards as this will lead to errors in ranking. We recommend that the health professional verify the rank order of importance once the patient has completed stacking the set of cards. |

| Trigger question: In your opinion, a dying patient's dignity is preserved when: |

| • Most important factor |

| • Least important factor |

| • Others treat her/him with respect |

| • Others honor her/him as a worthy individual |

| • Others meet her/his physical needs |

| • Others meet her/his emotional needs |

| • Her/his privacy is maintained (by others) |

| • S/he has independence and ability to make choices |

| • S/he has a positive self-image |

| • S/he has self-respect |

| • Her/his hope is preserved |

| • S/he can find meaning in her/his existence and death |

| Please note the patient's preferred ranking order and then consider asking exploratory questions about each of the items as appropriate (e.g., What can clinicians do to demonstrate respect to you?) and note down the patient's responses. Subsequent care given to the patient should be responsive to the patient's stated wishes and designed to preserve patient's sense of dignity. |

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute Grant RCA115562A, the National Library of Medicine Grant GO8LM007882, the Sierra-Pacific Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC), the VA Palo Alto Hospice Care Center and the VA Palo Alto Health Care System (Extended Care Services).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Allmark P. Death with dignity. J Med Ethics. 2002;28:255–257. doi: 10.1136/jme.28.4.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barthow C. Negotiating realistic and mutually sustaining nurse-patient relationships in palliative care. Int J Nurs Pract. 1997;3:206–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172x.1997.tb00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson G. Patients dignity exposed. NATNEWS. 1990;27:22–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davidson L. Patients clothing: Time for a change. Nurs Times. 1989;85:26–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coventry ML. Care with dignity: A concept analysis. J Gerontol Nurs. 2006;32:42–48. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20060501-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franklin LL. Ternestedt BM. Nordenfelt L. Views on dignity of elderly nursing home residents. Nurs Ethics. 2006;13:130–146. doi: 10.1191/0969733006ne851oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abiven M. Dying with dignity. World Health Forum. 1991;12:375–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madan TN. Dying with dignity. Soc Sci Med. 1992;35:425–432. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90335-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacelon CS. Connelly TW. Brown R. Proulx K. Vo T. A concept analysis of dignity for older adults. J Adv Nurs. 2004;48:76–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chochinov HM. Dignity-conserving care: A new model for palliative care. JAMA. 2002;287:2253–2260. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.17.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chochinov HM. Dignity and the eye of the beholder. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1336–1340. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chochinov HM. Defending dignity. J Support Palliat Care. 2004;1:307–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chochinov HM. Hack T. Hassard T. Kristjanson L. McClement S. Harlos M. Dignity and psychotherapeutic considerations in end of life care. J Palliat Care. 2004;20:143–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chochinov HM. Krisjanson LJ. Hack TF. Hassard T. McClement S. Harlos M. Dignity in the terminally ill: Revisited. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:666–672. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pokorny ME. The Effects of Nursing Care on Human Dignity in the Critically Ill Adult [dissertation] Virginia: University of Virginia; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Periyakoil VS. Kraemer HC. Noda AM. Creation and the empirical validation of the dignity card-sort tool (DCT) to assess factors influencing erosion of dignity at life's end. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:1125–1130. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strauss A. Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spiegelberg H. Human dignity: A challenge to contemporary philosophy. In: Gotesky R, editor; Laszlo E, editor. Human Dignity: This Century and the Next. New York: Gordon and Breach; 1970. pp. 39–64. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chochinov HM. Hack T. McClement S. Kristjanson L. Harlos M. Dignity in the terminally ill: A developing empirical model. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:433–443. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gallagher A. Dignity and respect for dignity—Two key health professional values: Implications for nursing practice. Nurs Ethics. 2004;11:587–599. doi: 10.1191/0969733004ne744oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harcum ER. Rosen EF. Perception of human dignity by college students and by direct-care providers. J Psychol. 1992;126:27–36. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harcum ER. Rosen EF. Perceived dignity of persons with minimal voluntary control over their own behaviors. Psychol Rep. 1990;67(3 Pt 2):1275–1282. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merriam-Webster [online] www.merriam-webster.com/ [Sep 8;2009 ]. www.merriam-webster.com/