Abstract

Morphogen gradients provide embryos with positional information, yet how they form is not understood. Binding of the morphogen to receptors could affect the formation of the morphogen gradient, in particular if the number of morphogen binding sites changes with time. For morphogens that function as transcription factors, the final distribution can be heavily influenced by the number of nuclear binding sites. Here, we have addressed the role of the increasing number of nuclei during the formation of the Bicoid gradient in embryos of Drosophila melanogaster. Deletion of a short stretch of sequence in Bicoid impairs its nuclear accumulation. This effect is due to a ∼4-fold decrease in nuclear import rate and a ∼2-fold reduction in nuclear residence time compared with the wild-type protein. Surprisingly, the shape of the resulting anterior-posterior gradient as well as the centre-surface distribution are indistinguishable from those of the normal gradient. This suggests that nuclei do not shape the Bicoid gradient but instead function solely during its interpretation.

Keywords: Morphogen, Pattern formation, Bicoid, Drosophila melanogaster

INTRODUCTION

A gradient of the transcription factor Bicoid provides the Drosophila embryo with positional information along the anterior-posterior axis (Driever and Nusslein-Volhard, 1988a; Driever and Nusslein-Volhard, 1988b; Grimm et al., 2010). This gradient arises from an anteriorly localised source of bicoid mRNA within 2 hours in a syncytial embryo of 500 μm length (Driever and Nusslein-Volhard, 1988b; St Johnston et al., 1989; Ephrussi and St Johnston, 2004; Grimm et al., 2010). The homeodomain transcription factor encoded by this mRNA moves from its site of production and accumulates in nuclei during each interphase, when it binds to its target sites on genes such as hunchback and possibly many more non-specific sites. The environment in which the Bicoid gradient forms is highly dynamic; the first eight nuclear divisions occur in the yolky interior of the embryo, following which the nuclei move to the surface where they continue their synchronous division cycles. The number of nuclei changes by three orders of magnitude from fertilisation to cycle 14, reaching ∼6000 surface nuclei in cycle 14. Even though nuclei continue to increase in number from 750 to 6000 at the surface of the embryo, the gradient is stable with respect to nuclear concentrations of Bicoid from cycle 10 to 14 (Gregor et al., 2007). Both nuclear transport and binding to DNA could affect the passage of Bicoid through the embryo. Moreover, given that the final number of nuclei is constant even when egg length varies, it has been suggested that nuclear-specific degradation of Bicoid could scale the gradient and contribute to its robustness in eggs of differing sizes (Gregor et al., 2005; Gregor et al., 2007). Here, we explore the role of nuclei in the formation of the Bicoid gradient.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Transgenes

ΔK50-57 (see Fig. S1 in the supplementary material) was synthesized by GenScript and subcloned into the rescuing Bicoid construct (Hazelrigg et al., 1998). Venus- and ECFP-Bicoid were generated by replacing GFP in pCAS-GFP-bicoid (Hazelrigg et al., 1998). For ΔSumo and ΔPEST, see Fig. S1 in the supplementary material.

Imaging

Embryos were imaged using the 20× HC PL APO Gly NA 0.7 objective on a Leica SP5 laser-scanning confocal microscope. Excitation wavelengths were 514 nm (Venus) and 456 nm (ECFP).

Western blotting

Dechorionated cycle 14 embryos were analysed by western blot following a standard protocol. Primary antibodies were rabbit anti-GFP (1:5000; Millipore, AB3080P) and mouse anti-α-tubulin (1:5000; Sigma clone DM 1a). Approximately 20 embryos were loaded per lane.

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP)

Nuclei were bleached by temporarily focusing a laser beam (514 nm) onto an individual nucleus. Fluorescence recovery was recorded in 5-second intervals. The bleached area was ∼6 μm in diameter; duration of the bleach pulse was 5×1.3 seconds. Nuclei were identified by the colocalisation of ECFP-wt Bicoid. FRAP curves were normalised as described (Axelrod et al., 1976).

Fluorescence quantification

Fluorescence intensities were extracted from images using software routines (Matlab) (Gregor et al., 2007; Houchmandzadeh et al., 2002). Fluorescence background was established by imaging fluorescent and non-fluorescent embryos side by side. Fluorescence always reaches background levels at 80-90% egg length. This position was routinely used to establish the background.

Measuring nuclear and cytoplasmic concentrations

Embryos were imaged at cycle12 when nuclei are sufficiently separated in space. We measured nuclear concentrations in the inner 50% of in-focus nuclei at the beginning of interphase.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

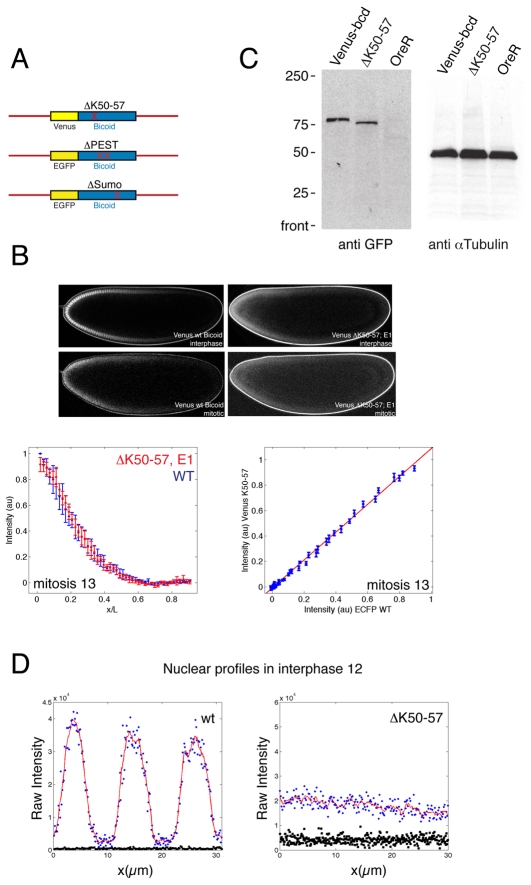

To test the effect of nuclear localisation of Bicoid on the overall shape of the gradient we generated three mutant Bicoid constructs that we expected would alter the nuclear accumulation and tagged them with the fluorescent proteins Venus and EGFP (Heim et al., 1995; Nagai et al., 2002). The first is a mutation (referred to as Sumo) of a high-probability sumoylation site (Fig. 1A and see Fig. S1 in the supplementary material) (Melchior, 2000). Mutation of a sumo-conjugating enzyme (Semushi; Lesswright – FlyBase) has been shown to eliminate Bicoid nuclear localisation (Epps and Tanda, 1998), raising the possibility that it is direct modification of Bicoid by sumoylation that controls nuclear transport. In a second construct, we deleted the PEST domain (Rogers et al., 1986) of Bicoid, which we expected would change its stability (Fig. 1A and see Fig. S1 in the supplementary material). As Bicoid is thought to be degraded inside nuclei (Gregor et al., 2007), we anticipated an alteration of nuclear accumulation in this mutant. The third construct is a deletion of a putative nuclear localisation signal (NLS) (Fig. 1A). Although Bicoid does not contain a canonical NLS, we reasoned that, as is the case for other homeodomain proteins, the information to localise to nuclei resides within the homeodomain (Abu-Shaar et al., 1999; Moede et al., 1999). Within the Bicoid homeodomain is a stretch of eight amino acids (homeodomain K50-57: KNRRRRHK) that is enriched in lysines and arginines (see Fig. S1 in the supplementary material), the latter being frequently found in NLSs (Lange et al., 2007). We found that deleting K50-57 changes the distribution of Bicoid from predominantly nuclear to uniform throughout the nucleo-cytoplasmic space (Fig. 1B). The distribution of this mutant in interphase resembled that of wild-type (wt) Bicoid during mitosis, when nuclear structures are absent (Fig. 1B). As expected of a transcription factor in which nuclear accumulation is altered, the ΔK50-57 transgene did not rescue the sterility of females homozygous for loss-of-function alleles of bicoid. Cuticles from mothers homozygous for bicoid that carry two copies of the mutant transgene resemble the null phenotype (data not shown). By contrast, the Sumo and PEST mutants showed normal nuclear accumulation and gradients, and importantly both constructs rescued embryos that were devoid of endogenous Bicoid (see Fig. S1 in the supplementary material).

Fig. 1.

Impaired nuclear localisation of ΔK50-57 Bicoid. (A) Outline of the mutant Bicoid constructs. Bicoid is tagged with either Venus or EGFP and flanked with the normal 5′ and 3′ regulatory regions. (B) Drosophila embryos expressing Venus-wt Bicoid and Venus-ΔK50-57 Bicoid in interphase and mitosis. Intensity profiles of ECFP-wt Bicoid and Venus-mutant Bicoid in mitosis 13 as a function of egg length (left). Plots of fluorescence intensities of ECFP-wt and Venus-ΔK50-57 in mitosis 13 (right). (C) Western blot of total embryo extract. The ΔK50-57 mutant is expressed at the predicted size of ∼75 kDa, with slightly higher mobility than wt Bicoid. (D) To compare Bicoid distribution between nucleus and cytoplasm, the imaging settings were chosen to maximise the dynamic signal range in each embryo. Shown are intensity profiles of Venus-wt and Venus-ΔK50-57 Bicoid. The nuclear concentration in wt embryos is ∼8-fold higher than in the cytoplasm, whereas in ΔK50-57 embryos there is no apparent difference between nucleus and cytoplasm. Blue is raw intensity, red is the local average of the raw intensity, and black is background.

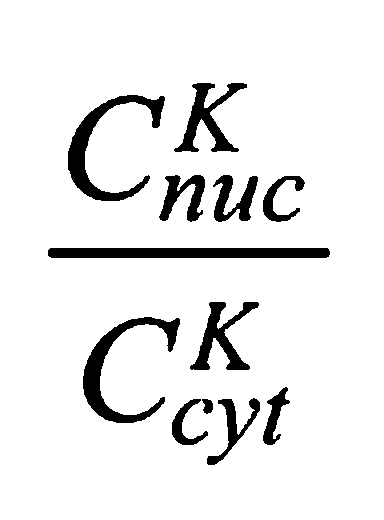

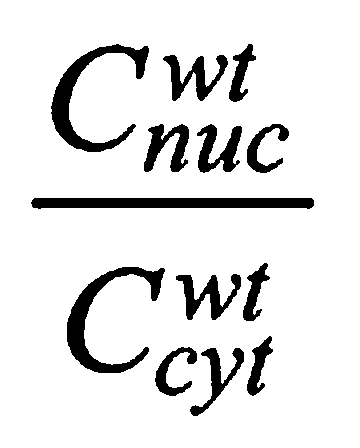

To quantify the effects of the K50-57 deletion, we compared its nucleo-cytoplasmic ratio to that of a Venus-wt Bicoid expressed using the same 5′ and 3′ control sequences. The nucleo-cytoplasmic ratio of ΔK50-57

|

in interphase was ∼1 (Fig. 1D), whereas the nucleo-cytoplasmic ratio of Venus-wt Bicoid

|

in interphase in cycle 12 was ∼8 (Fig. 1D). This value of the nucleo-cytoplasmic ratio is larger than previously reported (Gregor et al., 2007) and might reflect differences in the fluorescent proteins used, the type of microscope used and the cell cycle at which these measurements were made. Because nuclei represent only a small fraction of the total cytoplasm when we measure it at cycle 12, the total amount of wt Bicoid is roughly similar to that of ΔK50-57, consistent with the relative protein levels detected by western blotting (Fig. 1C). The apparent size of the ΔK50-57 mutant (∼75 kDa) is close to that expected for Venus plus Bicoid (Fig. 1C), indicating that we are detecting the full-length protein and not a degradation product of the fusion between Venus and Bicoid.

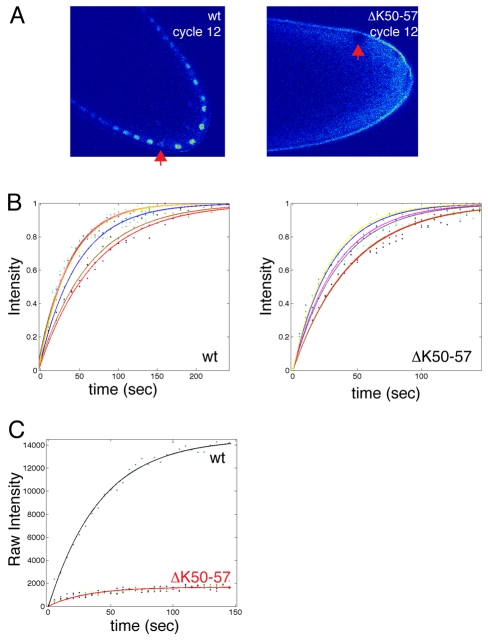

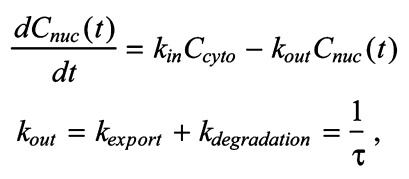

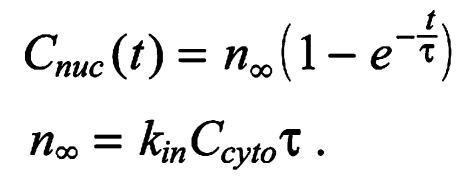

The 8-fold reduced nuclear accumulation in the ΔK50-57 mutant could be due to alterations in nuclear import, nuclear retention and/or nuclear export. To distinguish between these possibilities, we conducted fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments of individual nuclei to compare the nuclear dynamics of Venus-ΔK50-57 and Venus-wt Bicoid (Fig. 2A). We consider a model in which Bicoid is imported into the nucleus at a rate that is proportional to its cytoplasmic concentration (kinCcyto) and leaves the nucleus by export and/or intranuclear degradation (at rate kout=kexport+kdegradation) (Gregor et al., 2007). The change in nuclear concentration Cnuc(t) of Bicoid with time is given by:

Fig. 2.

Nuclear import and export rates are reduced for ΔK50-57 Bicoid. (A) FRAP of individual nuclei in wt and ΔK50-57 Drosophila embryos, both tagged with Venus. The recovering nuclei are indicated with an arrow. (B) Normalised recovery curves for wt and ΔK50-57 Bicoid. The coloured curves represent fits to the data from different experiments. (C) Raw recovery curves for wt and ΔK50-57, imaged at identical settings. The signal in nuclei containing wt Bicoid is ∼8-fold higher than for ΔK50-57.

|

where τ is the nuclear lifetime of Bicoid. The cytoplasmic concentration of Bicoid is approximately constant during these FRAP experiments. Under these conditions, the model predicts an exponential recovery:

|

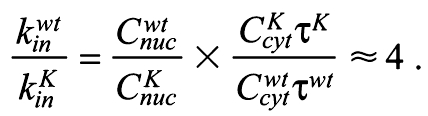

By fitting this model to our data we obtain a value for the nuclear lifetime of wt Bicoid, which is 73.9±21.9 seconds (n=7) (Fig. 2B), a value almost identical to that measured previously (68.9±17.6 seconds) (Gregor et al., 2007); by contrast, the nuclear lifetime of ΔK50-57 is 34.7±11.1 seconds (n=6) (Fig. 2B). A ∼2-fold difference in nuclear lifetime is significant but does not explain the ∼8-fold difference in nuclear concentration observed between wt and ΔK50-57 (Fig. 2C, Fig. 1D). The nucleo-cytoplasmic ratio during interphase, when it is at steady state [dCnuc(t)/dt=0], is determined by the ratio of nuclear import to export (Cnuc/Ccyt=kin/kout). Then, as we know both the nucleo-cytoplasmic ratio (Fig. 1D) and the nuclear lifetime (see above) (Fig. 2) for both wt and mutant Bicoid, we obtain a value for the relative nuclear import rate, which is:

|

In summary, deletion of K50-57 from Bicoid impairs both its nuclear import ability by ∼4-fold and reduces its nuclear lifetime by ∼2-fold.

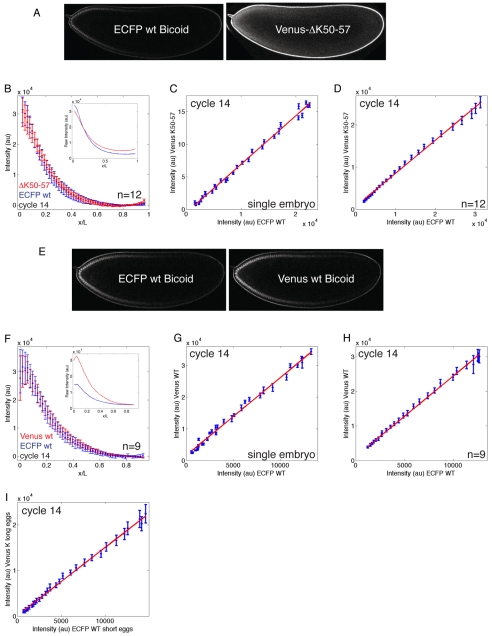

The effect of our mutant is obvious with respect to its altered nucleo-cytoplasmic localisation, but is difficult to assess with respect to the overall shape of the gradient. Therefore, we directly compared ΔK50-57 to wt Bicoid by expressing a Venus-tagged ΔK50-57 and a wt Bicoid tagged with enhanced cyan fluorescent protein (ECFP) (Heim and Tsien, 1996) within the same embryo (Fig. 3A). We extracted the respective intensity profiles from embryos expressing both ECFP-wt and Venus-ΔK50-57 Bicoid in interphase 14, when perturbation of the Bicoid gradient by nuclei is expected to be maximal (because the total nuclear volume is maximal), and plotted them as a function of egg length (Fig. 3B). To compare the mutant and wt gradient more directly, we generated plots of the fluorescence intensities from wt and mutant Bicoid gradients (Fig. 3C,D). If the gradients are identical then there should be a linear relationship between the two; if, however, the gradients are different this relationship should be non-linear. It is apparent from Fig. 3C,D that the ECFP-wt and Venus-ΔK50-57 Bicoid gradients are identical within the limits of error.

Fig. 3.

The anterior-posterior gradient of ΔK50-57 Bicoid is indistinguishable from that of wt Bicoid. (A) The same cycle 14 Drosophila embryo expressing both ECFP-wt Bicoid and Venus-ΔK50-57 Bicoid. Owing to differences in both wavelength and power of the excitation laser, the vitelline membrane appears brighter on the left-hand side. (B) Intensity profiles of ECFP-wt and Venus-ΔK50-57 Bicoid in cycle 14 as a function of egg length. (C) Fluorescence intensities of ECFP-wt and Venus-ΔK50-57 Bicoid from a single cycle 14 embryo. (D) As in C, but data are from 12 different cycle 14 embryos. (E) The same cycle 14 embryo expressing both ECFP- and Venus-wt Bicoid. (F) Intensity profiles of ECFP-wt and Venus-wt Bicoid in cycle 14 as a function of egg length. (G) Fluorescence intensities of ECFP-wt and Venus-wt Bicoid from a single cycle 14 embryo. (H) As in G, but data are from 9 different cycle 14 embryos. (I) Fluorescence intensities of ECFP-wt Bicoid from short eggs (<420 μm; n=9) and Venus-ΔK50-57 Bicoid from long eggs (>520 μm; n=5). Intensities are a function of egg length. In all plots, gradients were corrected for background. Error bars are s.d. (B,F) or s.e.m. (C,D,G,H,I; red line is linear fit to data) and represent equal numbers of data points.

Interaction of wt Bicoid with mutant Bicoid in the cytoplasm could cause the observed normal distribution of the mutant Bicoid. To test this possibility, we compared mutant Bicoid gradients in embryos devoid of any wt Bicoid to those of embryos expressing wt Bicoid (see Fig. S1 in the supplementary material). The distributions of mutant and wt Bicoid across embryos were indistinguishable (see Fig. S1 in the supplementary material), ruling out an interaction between wt and mutant Bicoid proteins.

It is a formal possibility that the gradients of ECFP-wt and Venus-ΔK50-57 are different but could be masked if different maturation times (Remington, 2002) of the fluorescent proteins were to counterbalance this effect. Such effects were however excluded by comparing wt versions of Venus- and ECFP-Bicoid (Fig. 3E-H). Thus, despite a ∼8-fold difference in nuclear import and retention rates, the mutant and wt proteins make indistinguishable anterior-posterior gradients from cycle 10 (when we can first observe it) to cycle 14. We therefore conclude that nuclei do not play an active role in shaping the Bicoid gradient.

Nuclei have been proposed to contribute to scaling of the Bicoid gradient in embryos of different length (Gregor et al., 2005; Gregor et al., 2007). Defects in scaling might easily escape our attention because the normal range/variation in embryo length is very subtle (the normal range of embryo length along the anterior-posterior axis is ∼490-510 μm). To look at scaling more directly, we obtained embryos from mothers heterozygous for Cyo513 (Schupbach and Wieschaus, 1989), which carries a temperature-sensitive mutation that produces a larger range in egg length (∼400-530 μm). As before, the mothers contributed both ECFP-wt and Venus-ΔK50-57 Bicoid. In plots of mutant gradients from long eggs (>520 μm) versus wt gradients from short eggs (<420 μm), there was a linear relationship (Fig. 3I), suggesting that scaling occurs independently of the nuclear accumulation of Bicoid.

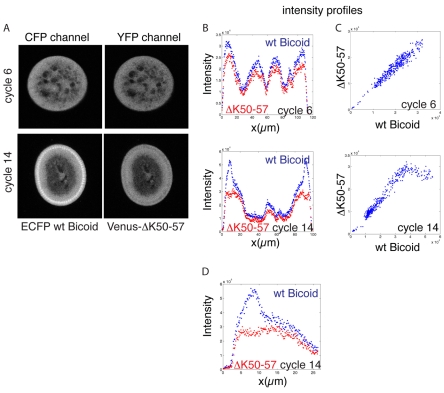

Bicoid is initially distributed uniformly along the centre-to-surface axis. When nuclei first appear at the surface of the embryo at cycle 10, this uniform distribution begins to change and Bicoid starts accumulating at the surface, possibly because Bicoid redistributes from the centre to the nuclei at the surface (Gregor et al., 2007). To test whether nuclear trapping or retention causes this centre-to-surface redistribution, we compared the distribution of wt and ΔK50-57 Bicoid (using the same ECFP versus Venus approach within the same sample) in cut sections of fixed embryos (Fig. 4A). We extracted intensity profiles for both ECFP-wt and Venus-ΔK50-57 Bicoid across the same section for slices at different stages and different anterior-posterior positions (Fig. 4B). The overall distribution of the mutant Bicoid appeared indistinguishable from wt Bicoid with the exception of protein levels inside nuclei (Fig. 4C,D). The intensity profiles of mutant and wt Bicoid exhibited a linear relationship everywhere except within nuclei (Fig. 4C,D). Thus, we conclude that nuclear import and/or retention does not cause the centre-to-surface redistribution of Bicoid.

Fig. 4.

Centre-to-surface distribution of Bicoid. (A) Wt and mutant Bicoid in sections of fixed Drosophila embryos in cycle 6 and in cycle 14. (B) Intensity profiles across the centre of the section for cycle 6 and cycle 14 embryos. (C) The relation between the wt and mutant intensities is linear at cycle 6. In cycle 14, this linear relationship is lost within the nuclear layer, where wt levels are high (>40,000 units) and mutant levels are low (∼25,000 units). (D) Intensity profiles for wt and mutant Bicoid within the nucleo-cytoplasmic area (∼25 μm). x-axis plots distance from the embryo surface; nuclei are located between ∼5 and ∼15 μm.

In this paper, we have addressed the role of nuclear import and retention on the formation of the Bicoid gradient by generating a mutant form of Bicoid that does not accumulate within nuclei. We used dual-colour imaging of mutant and wt Bicoid within the same embryo to reduce the variability due to timing in cross-embryo observations. Our principal finding is that nuclei do not affect the anterior-posterior or the centre-to-surface distribution of the protein. Our failure to detect an effect makes it unlikely that nuclei represent a major site of Bicoid degradation, or that they play a significant role in shaping or scaling the morphogen gradient. Instead, nuclei appear to be passive sensors of the Bicoid gradient. This is a surprising finding given that the transcription factor Bicoid accumulates in nuclei, the number of which increases by three orders of magnitude in less than ∼2 hours from fertilisation to cycle 14. Unfertilised eggs provide an alternative means of testing a role of nuclei in the formation of the Bicoid gradient. Previous observations were, however, inconclusive (Driever and Nusslein-Volhard, 1988a; Gregor et al., 2007), possibly reflecting the difficulties associated with staging and imaging the Bicoid gradient in unfertilised eggs.

One interpretation of our results is that the gradient reaches its steady state before cycle 10, at a stage when the number of nuclei is still low (∼750 nuclei) and therefore trapping of Bicoid by nuclei would not affect the shape of the gradient. However, the subsequent increase in nuclear density that occurs between cycles 10 and 14 might still have been predicted to alter the distribution of Bicoid if trapping or degradation became more efficient as the number of nuclei increased with each cycle. Such an effect has been observed for the Torso-dependent gradient of activated MAPK, which is activated at the two poles of the egg and sharpens with each round of mitosis in the embryo (Coppey et al., 2008). Whether such a sharpening would also be expected for the Bicoid gradient depends on its mobility and its lifetime and whether its distribution in the final cleavage stages continues to depend on movement from an anterior source. Using previously measured parameters (Gregor et al., 2007) and an assumed lifetime significantly longer than that of activated MAPK, Coppey et al. have calculated that the shape of the Bicoid gradient would be refractory to the number of nuclei (Coppey et al., 2007), and Spirov et al. have argued that the late distribution of Bicoid protein at cycle 14 reflects local synthesis from a graded mRNA source (Spirov et al., 2009). Distinguishing these and other models will require more accurate measurements of the relevant parameters (Grimm et al., 2010), but our exclusion of nuclear import, retention and degradation in shaping the gradient greatly simplifies such an analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Stas Shvartsman, Trudi Schupbach, Christine Sample, Stefano Di Talia, Mathieu Coppey, Jeff Drocco, Stephan Thiberge, Thomas Gregor, Jonathan Eggenschwiler and members of the E.W. laboratory for helpful discussions. This work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and NIH grants RO1 GM077599 and P50 GM 071508. Deposited in PMC for release after 6 months.

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/dev.052589/-/DC1

References

- Abu-Shaar M., Ryoo H. D., Mann R. S. (1999). Control of the nuclear localization of Extradenticle by competing nuclear import and export signals. Genes Dev. 13, 935-945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod D., Koppel D. E., Schlessinger J., Elson E., Webb W. W. (1976). Mobility measurement by analysis of fluorescence photobleaching recovery kinetics. Biophys. J. 16, 1055-1069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppey M., Berezhkovskii A. M., Kim Y., Boettiger A. N., Shvartsman S. Y. (2007). Modeling the bicoid gradient: diffusion and reversible nuclear trapping of a stable protein. Dev. Biol. 312, 623-630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppey M., Boettiger A. N., Berezhkovskii A. M., Shvartsman S. Y. (2008). Nuclear trapping shapes the terminal gradient in the Drosophila embryo. Curr. Biol. 18, 915-919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driever W., Nusslein-Volhard C. (1988a). The bicoid protein determines position in the Drosophila embryo in a concentration-dependent manner. Cell 54, 95-104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driever W., Nusslein-Volhard C. (1988b). A gradient of bicoid protein in Drosophila embryos. Cell 54, 83-93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ephrussi A., St Johnston D. (2004). Seeing is believing: the bicoid morphogen gradient matures. Cell 116, 143-152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epps J. L., Tanda S. (1998). The Drosophila semushi mutation blocks nuclear import of bicoid during embryogenesis. Curr. Biol. 8, 1277-1280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregor T., Bialek W., de Ruyter van Steveninck R. R., Tank D. W., Wieschaus E. F. (2005). Diffusion and scaling during early embryonic pattern formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 18403-18407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregor T., Wieschaus E. F., McGregor A. P., Bialek W., Tank D. W. (2007). Stability and nuclear dynamics of the bicoid morphogen gradient. Cell 130, 141-152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm O., Coppey M., Wieschaus E. (2010). Modelling the Bicoid gradient. Development 137, 2253-2264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazelrigg T., Liu N., Hong Y., Wang S. (1998). GFP expression in Drosophila tissues: time requirements for formation of a fluorescent product. Dev. Biol. 199, 245-249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim R., Tsien R. Y. (1996). Engineering green fluorescent protein for improved brightness, longer wavelengths and fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Curr. Biol. 6, 178-182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim R., Cubitt A. B., Tsien R. (1995). Improved green fluorescence. Nature 373, 663-664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houchmandzadeh B., Wieschaus E., Leibler S. (2002). Establishment of developmental precision and proportions in the early Drosophila embryo. Nature 415, 798-802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange A., Mills R. E., Lange C. J., Stewart M., Devine S. E., Corbett A. H. (2007). Classical nuclear localization signals: definition, function, and interaction with importin alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 5101-5105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melchior F. (2000). SUMO-nonclassical Ubiquitin. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 16, 591-626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moede T., Leibiger B., Pour H. G., Berggren P., Leibiger I. B. (1999). Identification of a nuclear localization signal, RRMKWKK, in the homeodomain transcription factor PDX-1. FEBS Lett. 461, 229-234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai T., Ibata K., Park E. S., Kubota M., Mikoshiba K., Miyawaki A. (2002). A variant of yellow fluorescent protein with fast and efficient maturation for cell-biological applications. Nat. Biotechnol. 20, 87-90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remington S. J. (2002). Negotiating the speed bumps to fluorescence. Nat. Biotechnol. 20, 28-29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers S., Wells R., Rechsteiner M. (1986). Amino acid sequences common to rapidly degraded proteins: the PEST hypothesis. Science 234, 364-368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schupbach T., Wieschaus E. (1989). Female sterile mutations on the second chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster. I. Maternal effect mutations. Genetics 121, 101-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spirov A., Fahmy K., Schneider M., Frei E., Noll M., Baumgartner S. (2009). Formation of the bicoid morphogen gradient: an mRNA gradient dictates the protein gradient. Development 136, 605-614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Johnston D., Driever W., Berleth T., Richstein S., Nusslein-Volhard C. (1989). Multiple steps in the localization of bicoid RNA to the anterior pole of the Drosophila oocyte. Development 107Suppl, 13-19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.