Abstract

The Millennium Declaration, adopted by the United Nations (UN) in 2000, set a series of Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) as priorities for UN member countries, committing governments to realising eight major MDGs and 18 associated targets by 2015. Progress towards these goals is being assessed by tracking a series of 48 technical indicators that have since been unanimously adopted by experts. This concept paper outlines the role member Health and Demographic Surveillance Systems (HDSSs) of the INDEPTH Network could play in monitoring progress towards achieving the MDGs. The unique qualities of the data generated by HDSSs lie in the fact that they provide an opportunity to measure or evaluate interventions longitudinally, through the long-term follow-up of defined populations.

Keywords: Health and Demographic Surveillance Systems, Millennium Development Goals, longitudinal data, monitoring MDG progress

In September 2000, the Millennium Declaration, endorsed by 189 countries, was adopted by the United Nations (UN) (1). The associated Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) represent the current priorities of UN member countries, and governments are committed to realising eight major goals and 18 targets by 2015. The MDGs represent human needs and basic rights that every individual in the world should be able to enjoy. According to current assessments (2), the Millennium Declaration in 2000 was a milestone in international cooperation, inspiring development efforts that have improved the lives of hundreds of millions of people around the world. However, it is clear that improvements in the lives of the poor have been unacceptably slow, and some hard-won gains are being eroded by climatic, food, and economic crises. Indeed, progress remains uneven with sub-Saharan Africa trailing behind.

Progress towards the MDGs is being assessed by tracking a series of 48 technical indicators that have been unanimously adopted by experts. Of course, a systematic assessment of the progress made in each country towards these goals would necessitate the existence of empirical data allowing measurement over time of the accomplishment of various targets, based on changes in indicators. However, many low-income and developing countries lack the conventional data sources for systematic assessment of the MDGs. In the absence of reasonably operational vital registration systems, censuses and surveys have dominated as the main source of demographic information and these have a limited degree of accuracy (3, 4). Recent years have seen escalating waves of national surveys across developing countries, conducted under the auspices of the World Fertility Survey (WFS), the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), and the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) programmes. Despite the contributions made by these surveys, their utility is limited by their cross-sectional nature, which to some extent works against long-term evaluations of interventions that could provide systematic indicators of progress towards the MDGs.

This concept paper outlines the role that Health and Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS) centres, such as those operated as members of the INDEPTH Network, could play in monitoring progress towards achieving the MDGs. The HDSS centres collect longitudinal data within defined populations on the core components of population change – births, deaths, and migrations, as well as indicators of nuptiality such as marriage. In addition to these core indicators that are collected at regular intervals (the interval varying at different centres, from one to four times a year), on an annual basis there are regular updates of educational status of all persons of school age and parameters such as socio-economic status of households within the defined populations that are also collected.

The unique qualities of these data lie in the fact that they provide an opportunity to measure and evaluate interventions through the long-term follow-up of populations. For instance, epidemiologists and social scientists are often interested in changes and their underlying causal relationships. So if change is the subject of study, as in the case of evaluating the MDGs, the surest way to investigate it is by observing subjects from one point in time to another point in time over long periods (5). The evolution of change cannot be ascertained without having data available from repeated observations on the same individuals over time. The HDSS data provide the best opportunity for this. Further, to attribute causality, for assessing whether a certain intervention is responsible for an observed impact, longitudinal data as provided by HDSS centres is essential. It is in this vein that we see the contribution of this paper.

Background on Health and Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS) data

Reliable and timely data are needed in any democratic society to guide policy deliberations. However, in most developing countries the vital registration system and comprehensive socio-demographic data needed to assess progress in social policy and practice are often inadequate. Because the lives and well-being of people are dynamic in nature, HDSSs offer a unique window on the processes of change in various communities. Indeed, longitudinal data collection efforts attempt to reproduce the wealth of information that is afforded by the continuous recording of events and their causes (6).

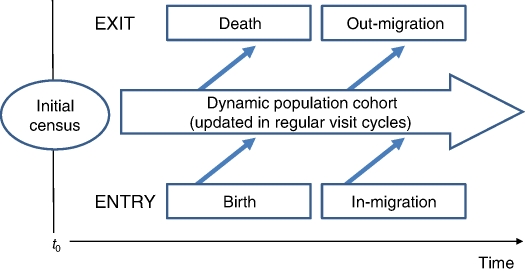

The HDSSs consist of a series of field operations that entail longitudinal follow-up of well-defined entities (individuals, households, and residential units) and all related demographic and health outcomes within a well-defined geographic area (3). An HDSS usually starts with a baseline census that defines the initial population. This population is subsequently followed up at regular intervals to record whatever changes may be occurring in the population. Changes to the initial population may result either from people being born or migrating into the population or dying or migrating out of the population as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The concept of a longitudinal Health and Demographic Surveillance System.

In order to ascertain causes of death (which are generally not ascertained or recorded in most parts of the developing world), the deaths that occur in HDSS populations are followed up with interviews of relatives or caretakers at the time of death to ascertain the circumstances leading to those deaths. This process, known as verbal autopsy, has allowed INDEPTH to provide cause of death data unparalleled in the developing world (7).

A typical HDSS may also include registration of marriages, divorces, and changes in status and household relationships. Such additional information is critical for a better understanding of the demographic dynamics under observation. By monitoring new health threats, tracking population changes through fertility rates and migration, and measuring the effect of policy interventions on communities, HDSSs allow policy makers to make decisions that can have a real impact on communities and to adapt those decisions to changing conditions.

Health and Demographic Surveillance Systems (HDSSs) and Millennium Development Goal (MDG) indicators

The HDSSs provide the requisite infrastructure in low- and middle-income countries for monitoring progress towards the MDGs, as well as for evaluating nationally driven health interventions. We have summarised (Tables 1 and 2) some of the measurable indicators of progress relating to core HDSS data and supplementary HDSS data, respectively. For each of these indicators, some member centres are in a position to provide information needed for monitoring progress. For example, INDEPTH is in the process of publishing a monograph on mortality (both child and adult) and 29 of our member sites have provided data that are being used to generate various indices of childhood and adult mortality. By country these are: Africa Centre; Agincourt and Digkale (South Africa); Ballabgarh and Vadu (India); Chakaria, Matlab, and Abhoynagar-Mirsaria (Bangladesh); Dodowa, Kintampo, and Navrongo (Ghana); Nairobi, Kilifi, and Kisumu (Kenya); Filabavi (Vietnam); Iganga/Mayuge (Uganda); Ifakara, Magu, and Rufiji (Tanzania); Karonga (Malawi); Kanchanaburi (Thailand); Nouna (Burkina Faso); Farafenni and Kiang West (The Gambia); Bandim (Guinea Bissau); Purworejo (Indonesia); Wosera (Papua New Guinea); Manhica (Mozambique); and Butajira (Ethiopia). In Table 3, we provide a list of INDEPTH member centres, with year of establishment, and total population under surveillance. We discuss below some of the MDGs, their indicators of progress, and the role longitudinal data generated from INDEPTH member centres could play in evaluating these.

Table 1.

MDG indicators that can be produced regularly by typical HDSS centres

| MDG indicators | Capacity of HDSS to provide data | |

|---|---|---|

| Goal 2: Achieve universal primary education | ||

| Indicator 6. Net enrolment ratio in primary education | Core | |

| Indicator 7. Proportion of pupils starting grade 1 who reach grade 5 | ||

| Indicator 7 (alternate). Primary completion rate | ||

| Indicator 8. Literacy rate of 15–24 year olds | ||

| Goal 3: Promote gender equality and empower women | ||

| Indicator 9. Ratios of girls to boys in primary, secondary, and tertiary education | Core | |

| Indicator 10. Ratio of literate females to males 15–24 year olds | ||

| Goal 4: Reduce child mortality | ||

| Indicator 13. Under-five mortality rate | Core | |

| Indicator 14. Infant mortality rate | ||

| Goal 5: Improve maternal health | ||

| Indicator 16. Maternal mortality ratio | Core | |

| Indicator 17. Proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel | ||

| Goal 6: Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases | ||

| Indicator 18. HIV prevalence among 15–24-year-old pregnant women | Core | |

| Indicator 19. Condom use rate of the contraceptive prevalence rate | ||

| Indicator 21. Prevalence and death rates associated with malaria | Core | |

| Indicator 22. Proportion of population in malaria risk areas using effective malaria prevention and treatment measures | ||

| Indicator 23. Prevalence and death rates associated with tuberculosis | ||

Table 2.

MDG indicators that can be produced by typical HDSS centres using additional or special modules

| MDG indicators | Capacity of HDSS to provide data | |

|---|---|---|

| Goal 1: Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger | ||

| Indicator 4. Prevalence of underweight children under 5 years of age | Needs sample module | |

| Indicator 5. Proportion of population below minimum level of dietary energy consumption | ||

| Goal 3: Promote gender equality and empower women | ||

| Indicator 11. Share of women in wage employment in the non-agricultural sector | Needs sample module | |

| Goal 4: Reduce child mortality | ||

| Indicator 15. Proportion of 1-year-old children immunised against measles | Core with immunisation module | |

| Goal 6: Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases | ||

| Indicator 18. HIV prevalence among 15–24-year-old pregnant women | Core with HIV module | |

| Indicator 19. Condom use rate of the contraceptive prevalence rate | ||

| Indicator 20. Ratio of school attendance of orphans to school attendance of non-orphans aged 10–14 | Core with education module | |

| Indicator 24. Proportion of tuberculosis cases detected and cured under DOTS | Needs special studies | |

| Goal 7: Ensure environmental sustainability | ||

| Indicator 25. Proportion of land area covered by forest | Core with GIS module | |

| Indicator 26. Ratio of area protected to maintain biological diversity to surface area | ||

| Indicator 27. Energy use (kg oil equivalent) per US$1,000 GDP | Core with asset survey module | |

| Indicator 29. Proportion of population using solid fuels | ||

| Indicator 30. Proportion of population with sustainable access to an improved water source, urban and rural | Core with asset-environment study module | |

| Indicator 32. Proportion of households with access to secure tenure | ||

| Goal 8: Develop a global partnership for development | ||

| Indicator 45. Unemployment rate of 15–24-year-olds, each sex and total | Core | |

| Indicator 46. Proportion of population with access to affordable essential drugs on a sustainable basis | ||

| Indicator 47. Telephone lines and cellular subscribers per 100 population | Core with asset survey module | |

| Indicator 48. Personal computers in use per 100 population and Internet users per 100 population | ||

Table 3.

Network membership and population under surveillance

| INDEPTH HDSS member name | Country | Year established | Year of INDEPTH membership | Approximate population under surveillance | Institutional affiliation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa Centre (CDIS) | South Africa | 1999 | 1999 | 90,000 | University of Natal and Durban |

| Agincourt | South Africa | 1992 | 1998 | 70,000 | University of Witwatersrand |

| Ballabgarh | India | 1972 | 2003 | 41,000 | All India Institute of Medical Sciences in Collaboration with State Government of Haryana |

| Bandim | Guinea Bissau | 1978 | 1998 | 101,000 | MoH/Staten Serum Institut |

| Bandafassi | Senegal | 1970 | 2001 | 11,200 | IRD |

| Butajira | Ethiopia | 1987 | 1999 | 40,000 | Addis Ababa University |

| Chililab | Vietnam | 2003 | 2003 | 64,000 | Hanoi School of Public Health |

| Chakaria | Bangladesh | 1999 | 2007 | 47,000 | ICDDR,B |

| Dikgale | South Africa | 1995 | 1998 | 8,000 | University of Limpopo |

| Dodowa | Ghana | 2005 | 2005 | 101,000 | Ghana Health Service/Ministry of Health |

| Farafenni | The Gambia | 1981 | 1981 | 17,000 | UK Medical Research Council (MRC) |

| Filabavi | Vietnam | 1998 | 1998 | 52,000 | Centre for Social Sciences in Health (MoH), Hanoi; Hanoi Medical University |

| AMK (HSID) | Bangladesh | 1982 | 1998 | 275,000 | ICDDR,B |

| Ifakara | Tanzania | 1996 | 1998 | 72,000 | Own Institute |

| Kanchanaburi | Thailand | 2000 | 2004 | 45,000 | Mahidol University, IPSR |

| Karonga | Malawi | 2002 | 2003 | 40,000 | London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine |

| Iganga/Mayuge | Uganda | 2004 | 2005 | 67,000 | Makerere University Institute of Public Health |

| Kiang West | The Gambia | 2004 | 2010 | 14,000 | UK Medical Research Council (MRC) |

| Kilifi | Kenya | 2001 | 2005 | 220,000 | Kenya Medical Research Institute/Wellcome Trust |

| Kintampo | Ghana | 2003 | 2004 | 145,000 | Ghana Health Service/Ministry of Health |

| Kisumu | Kenya | 1992 | 1998 | 135,000 | Kenya Medical research Institute/CDC |

| Manhica | Mozambique | 1996 | 1998 | 80,000 | National Institute of Health Clinic (University Hospital) Barcelona |

| Magu | Tanzania | 1994 | 2001 | 22,000 | TANESA Programme (an HIV/AIDS project) |

| Matlab | Bangladesh | 1966 | 1998 | 225,000 | ICDDR,B |

| Mlomp | Senegal | 1985 | 2001 | 7,500 | IRD |

| Nairobi | Kenya | 2002 | 2002 | 68,600 | NGO—APHRC |

| Navrongo | Ghana | 1993 | 1998 | 144,000 | Ghana Health Service/Ministry of Health |

| Niakhar | Senegal | 1962 | 1999 | 35,000 | IRD |

| Nouna | Burkina Faso | 1992 | 1998 | 76,800 | Ministry of Public Health and University of Heidelberg |

| Ouagadougou | Burkina Faso | 2002 | 2003 | 80,000 | ISSP, University of Ouagadougou |

| Purworejo | Indonesia | 1994 | 1998 | 55,000 | Gajah Mada University in collaboration with the Ministry of Health District of Purworejo and Belu |

| Rufiji | Tanzania | 1998 | 1998 | 90,000 | TEHIP, MoH |

| Rakai | Uganda | 1988 | 1999 | 12,000 | MoH, Makerere, Columbia and Johns Hopkins University |

| Sapone | Burkina Faso | 2004 | 2005 | 68,000 | Centre National de Recherche et de Formation Sur le Paludisme (CNRFP) MoH |

| Vadu | India | 2002 | 2003 | 68,000 | KEM Hospital |

| Wosera | Papua New Guinea | 1999 | 2003 | 140,000 | PNG Institute of Medical Research |

Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 1: eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

The first MDG focuses on eradication of the extreme poverty and hunger to which more than a billion people were subject in 2000. Allied to this goal are two targets that envision reducing by half the proportion of persons living on less than US$1 a day as well as reducing by half the proportion of persons suffering from extreme hunger. Progress towards this goal is assessed by using five technical indicators. While surveillance data may not be able to capture all the important indicators of poverty, many of our member centres collect information on household socio-economic status indicators and in special modules data on anthropometry. With this information it is possible to compute poverty indices over time and the proportion of children underweight as a proxy for dietary intake. The Rufiji centre in Tanzania and the Niakhar in Senegal have been collecting information on food security for quite some time now. A food security module, incorporated into a major SES tool developed by INDEPTH, is now in use in many INDEPTH member centres to collect data.

Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 2: achieve universal primary education

Education for all, particularly for women and children, has been underscored as a driving force for development and the elimination of obstacles to which some population groups are subjected. Hence, education is considered a major factor in the achievement of almost all the MDGs. Consistent with the goal of achieving universal primary education for all is the target to ensure that children everywhere, boys and girls alike, are able to complete a full course of primary schooling and that girls and boys will have equal access to all levels of education. Almost all INDEPTH member centres collect (on an annual basis) information on the educational status on all persons of school age. Key indicators that could be computed are completion, attainment, and progression rates. With these measures, it is possible to evaluate progress in education over time.

Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 3: promote gender equality and empower women

Promoting gender equality and empowering women is considered an effective way to combat poverty, hunger, and disease and stimulate truly sustainable development. Consistent with the goal is target 4 that envisions the elimination of gender disparity in primary and secondary education and, preferably, all levels of education by 2015. As noted in Table 1, two of the four agreed indicators for assessing progress on this goal can easily be obtained from core data in typical HDSSs. With additional effort – hopefully in the near future – the third indicator (share of women in wage employment in the non-agricultural sector) can also be obtained through the introduction of a special food security module mentioned under MDG 1.

Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 4: reduce child mortality

The goal envisioned here is to reduce child mortality by two-thirds by 2015 compared with 1990 levels. To ensure a reliable estimate of the resident population at any time, HDSSs collect information on three core events: births, deaths, and migration. Pregnancies and their outcomes for all women residents in the HDSS populations are recorded irrespective of the place of occurrence of such events. Similarly, the deaths of all registered and eligible individuals are recorded. Hence, the first two indicators under this goal are obtainable from routinely available core HDSS data while the last one is obtainable from most HDSS centres thanks to the immunisation module currently being implemented.

Measurable indicators for attaining MDG 4 are infant and child mortality that HDSS centres are uniquely placed to provide. Centres collect information on all deaths including neonatal, infant, child, and indeed, adult deaths. This information is collected continuously and many of our HDSS sites have been collecting this information for more than 10 years, some since the 1990 comparison point (see Table 3). It is therefore possible to evaluate trends in these indicators leading to empirical assessments of MDG 4. In addition, for all children born within HDSS populations, information is collected on an annual basis about their immunisation status, which is one of the key indicators for measuring child survival. Recent publications from two of our member centres have aptly demonstrated how HDSS data can be used to measure MDG 4 and 5 (8–10).

Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 5: improve maternal health

For maternal mortality, a reduction of three-quarters is envisioned by 2015. As noted previously, an HDSS starts with an initial census of its population. Subsequently, all pregnancies and their outcomes as well as deaths are recorded. As such the HDSSs have the potential to provide accurate up-to-date estimates of maternal mortality and trends. However, as is evident from Table 1, in order to estimate one of the indicators (proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel) we will need a new module that can be easily incorporated into routine procedures.

Measurable indicators for MDG 5 are maternal mortality rates or ratios and proportion of births attended by skilled personnel. Since HDSS centres collect information on all deaths including those related to maternal causes, it is possible to compute maternal mortality ratios over time across many sites. This information will allow for monitoring progress in maternal mortality. It is also possible to determine the proportion of deaths that are attended by skilled personnel because for each death that occurs within the HDSS area, information is asked about where it happened (at home, in a clinic, hospital, or at the premises of a TBA, etc.).

Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 6: combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases

This goal envisioned that the threat of infectious disease such as malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS could be held in check and indeed reversed. In order to monitor progress on this goal, a set of seven indicators was proposed. The measurable indicators for this MDG include the prevalence and death rates associated with malaria, proportion of the population in malaria risk areas using effective malaria prevention and treatment measures, as well as the prevalence and death rates associated with tuberculosis (indicators 21–23). Indeed, in many HDSSs there is substantial ongoing malaria surveillance along with studies evaluating the impact of malaria interventions. Hence, data on malaria prevalence can readily be provided. Secondly, INDEPTH is taking advantage of antiretroviral therapy (ART) roll-out programmes across Africa to evaluate their impact on individuals using ART, their relatives, households, and the population in general. To date, there has been no evaluation of the impact of this natural experiment being rolled out on such a massive scale. With its population surveillance infrastructure, INDEPTH is uniquely placed in the developing world for evaluating this programme.

Discussion and conclusion

Although the countdown to the MDG targets now has less than 5 years to run, very little is understood as to where nations of the world stand in their trajectories towards attaining the goals set out by the UN in 2000. Even if the measurable indicators of progress are well understood, there are very limited data in many parts of the world, particularly in developing countries, to carefully monitor progress. National censuses covering entire populations might be regarded as good sources of data for measuring national progress towards the MDGs in the absence of complete vital registration. Unfortunately censuses are usually only conducted every 10 years and so are insufficient sources of data for monitoring progress due to their widely spaced periodicity. In addition, the scope of data collected in censuses is often limited to a few variables. Recognition of these limitations led to the widespread implementation of DHS, as well as other periodic national cross-sectional surveys. The DHS programme is a US-sponsored global initiative that undertakes relatively large and complex cross-sectional surveys of demographic and health parameters on nationally representative samples in poor and middle-income countries (http://www.measuredhs.com). Except for country-specific variables, the underlying methodology has been standardised. Unlike the HDSS approach, a fresh sample is usually taken within selected clusters for each DHS round (normally at 5-year intervals).

However, while the DHS and other national sample surveys such as the MICS provide alternate sources of data for generating periodic indicators that can be used to measure progress towards the MDGs, they are rather limited by being cross-sectional in nature. They lack the critical attribute of being able to follow the same individuals and households over a long period of time, allowing monitoring of real changes that occur to individuals and the households within which they live in.

It is within the context of the above limitations that the advantages of longitudinal surveillance data collected by INDEPTH member centres become apparent. For instance, household formation and dissolution and concomitant events that happen to individuals within those households can be captured by HDSS data. The unique qualities of INDEPTH data stem from the fact that they are longitudinal in nature and span many years (back in many cases prior to 1990) the reference point for several MDGs. Apart from the key data that demographers are often interested in – fertility, mortality, and migration – the HDSS centres also collect data on various health and socio-economic issues, including data related to reproductive health, malaria, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, and household economics on a regular basis. Hence, it is possible to have measures for many of the MDG indicators from 1990 until the present and ultimately up to 2015. We have identified that HDSS data could provide evidence for monitoring many key indicators of progress and thus assist prioritisation in health reforms. These include indicators of child and adult mortality (including maternal mortality), reproductive health, HIV/AIDS, malaria, education, poverty, and gender inequality.

However, it is important to consider that while data from INDEPTH member centres provide nuances that many national level surveys do not, most of the INDEPTH centres are located at district level and may therefore provide information that is not necessarily representative of the entire country. However, in many countries there are multiple HDSS locations where longitudinal data are collected representing different geographical regions. Indeed, in countries such as South Africa, Ghana, Tanzania, Burkina Faso, and Bangladesh, where there are multiple HDSS locations, governments are utilising them as sentinel sites to collect data for informing national health priorities. Tatem et al. (11) investigated the comprehensiveness in coverage of the network of rural HDSS centres in Africa in terms of the range of ecological zones found across the continent, and have shown that the current INDEPTH HDSS network in Africa spans all the major environmental zones.

While we argue for the unique advantages of HDSS data for evaluating the MDGs, we recognise the role of other sources (censuses, DHS, MICS, etc.) in providing other good measures that may not necessarily be collected by the HDSSs. To this end, analysts have started arguing for the triangulation of various sources of data that may allow for a more comprehensive understanding of various measures. In this regard, a few analytic comparisons between HDSS and other cross-sectional data have been conducted either for the purposes of ascertaining whether results could be comparable or to establish complementarity. A few studies have specifically compared HDSS data with other sources such as DHS or census data. Bairagi et al. (12) conducted a validation study comparing fertility and infant mortality rates from a special 1994 Matlab DHS and compared their results with the Matlab HDSS for the period 1990–1994. While they found consistent estimates for fertility and mortality, results of the special DHS underestimated contraceptive rates. Hammer et al. (13) found comparable estimates for childhood mortality between the Nouna HDSS data and the 1998–1999 Burkina Faso DHS. Nhacolo et al. (14) compared Manhica HDSS data with the Mozambican national census and DHS data for the same region, with comparable results. Byass et al. (15) compared mortality estimates from Butajira HDSS with estimates from two rounds of Ethiopian national DHS data and found basically comparable results.

While the above studies broadly showed that that DHS data can produce similar results to HDSS data for overall parameters, the unique advantage of the HDSS data is its longitudinality and, hence, relative lack of recall bias. It is also important to note that within these overall comparable results, HDSS data can also reveal local level variations that cannot be captured from DHS data (12, 15, 16).

What is needed now is to harness the potential that INDEPTH HDSS centres offer, together with other national level data, to inform national programmes monitoring the achievement of MDGs. However, we argue that HDSSs have a huge potential to become the key data source for monitoring the MDGs, particularly if countries set up multiple HDSS centres within their boundaries to serve as sentinel centres (17).

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry to conduct this study.

References

- 1.United Nations 2000. United Nations millennium declaration: resolution adopted by the General Assembly, 55th Session; 2000. Sep 18, [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations. New York: United Nations; The millennium development goals report 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.INDEPTH Network. Population and health in developing countries. Vol. 1. Population, health, and survival at INDEPTH sites. Ottawa: IDRC; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sankoh OA, Binka F . on behalf of the INDEPTH Network. INDEPTH network: generating empirical population and health data in resource-constrained countries in the developing world. In: Becher H, Kouyate B, editors. Health research in developing countries. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Verlag; 2005. pp. 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bawah AA. Spousal communication and family planning behaviour in Navrongo: a longitudinal assessment. Stud Fam Plann. 2002;33:185–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2002.00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mbacke CS, Phillips JF. Longitudinal community studies in Africa: challenges and contributions to health research. Asia Pacific Popul J. 2008;23:23–38. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adjuik M, Smith T, Clark S, Todd J, Garrib A, Kinfu Y, et al. Cause-specific mortality rates in sub-Saharan Africa and Bangladesh. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84:181–8. doi: 10.2471/blt.05.026492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Binka FN, Bawah AA, Phillips JP, Abraham H, Adjuik M, MacLeod B. Rapid achievement of the child survival millennium development goal: evidence from the Navrongo experiment in northern Ghana. Trop Med and Int Health. 2007;12:578–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bawah AA, Phillips JF, Adjuik M, Vaughan-Smith M, MacLeod B, Binka FN. The impact of immunization on the association of poverty with child survival: evidence from Kassena-Nankana District of Northern Ghana. Scand J Public Health. 2010;38:95–103. doi: 10.1177/1403494809352532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masanja H, de Savigny D, Smithson P, Schellenberg J, John T, Mbuya C, et al. Child survival gains in Tanzania: analysis of data from demographic and health surveys. Lancet. 2008;371:1276–83. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60562-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tatem AJ, Snow RW, Hay SI. Mapping the environmental coverage of the INDEPTH demographic surveillance system network in rural Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11:1318–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01681.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bairagi R, Becker S, Kantner A, Allen KB, Datta A, Purvis K. An evaluation of the 1993–94 Bangladesh demographic and health survey within the Matlab area. Asia Pacific Popul Res Abstracts. 1997;11:1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammer GP, Kouyate B, Ramroth H, Becher H. Risk factors for childhood mortality in sub-Saharan Africa: a comparison of data from a demographic and health survey and from a demographic surveillance system. Acta Tropica. 2006;98:212–8. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nhacolo AQ, Nhalungo DA, Saccoor CN, Aponte JJ, Thompson R, Alonso P. Levels and trends of demographic indices in southern rural Mozambique: evidence from demographic surveillance in Manhica district. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:291. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Byass P, Worku A, Emmelin A, Berhane Y. DSS and DHS: longitudinal and cross-sectional viewpoints on child and adolescent mortality in Ethiopia. Popul Health Metrics. 2007;5:12. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-5-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Becher H. Analyses of mortality clustering at member HDSSs within the INDEPTH Network – an important public health issue. Global Health Action Suppl 1. 2010 doi: 10.3402/gha.v3i0.5476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonita R. Strengthening NCD prevention through risk factor surveillance. Global Health Action Suppl 1. 2009 doi: 10.3402/gha.v2i0.2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]