ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE

To understand and describe the menopause experiences and perspectives of First Nations women residing in northwestern Ontario.

DESIGN

Phenomenologic approach using in-depth qualitative interviews.

SETTING

Sioux Lookout, Ont, and 4 surrounding First Nations communities.

PARTICIPANTS

Eighteen perimenopausal and postmenopausal First Nations women, recruited by convenience and snowball sampling techniques.

METHODS

Semistructured interviews were audiotaped and transcribed. Themes emerged through a crystallization and immersion analytical approach. Triangulation of methods was used to ensure reliability of findings.

MAIN FINDINGS

This study confirms the hypothesis that menopause is generally not discussed by First Nations women, particularly with their health care providers. The generational knowledge gained by the women in this study suggests that a variety of experiences and symptoms typical of menopause from a medical perspective might not be conceptually linked to menopause by First Nations women. The interview process and initial consultation with translators revealed that there is no uniform word in Ojibway or Oji-Cree for menopause. A common phrase is “that time when periods stop,” which can be used by caregivers as a starting point for discussion. Participants’ interest in the topic and their desire for more information might imply that they would welcome the topic being raised by health care providers.

CONCLUSION

This study speaks to the importance of understanding the different influences on a woman’s menopause experience. Patient communication regarding menopause might be enhanced by providing women with an opportunity or option to discuss the topic with their health care providers. Caregivers should also be cautious of attaching preconceived ideas to the meaning and importance of the menopause experience.

RÉSUMÉ

OBJECTIF

Comprendre et décrire ce que les femmes des Premières nations du Nord-Ouest de l’Ontario connaissent et pensent de la ménopause.

TYPE D’ÉTUDE

Approche phénoménologique à l’aide d’entrevues qualitatives en profondeur.

CONTEXTE

Sioux Lookout, Ontario et 4 communautés des Premières nations des environs.

PARTICIPANTES

Dix-huit femmes périménopausées ou ménopausées des Premières nations, recrutées de façon informelle et par des techniques d’échantillonnage boule de neige.

MÉTHODES

Les entrevues semi-structurées ont été enregistrées sur ruban magnétique et transcrites. Les thèmes ont été extraits par une approche analytique de cristallisation et d’immersion. On s’est assuré de la fiabilité des observations par triangulation des méthodes.

PRINCIPALES OBSERVATIONS

Cette étude confirme l’hypothèse que les femmes des Premières nations ne discutent généralement pas de la ménopause, particulièrement avec les dispensateurs de soins. Les connaissances que les femmes de cette étude ont acquises de leur milieu laissent croire qu’une variété d’expériences et de symptômes qui, d’un point de vue médical, sont typiques de la ménopause pourraient ne pas être vus ainsi par les femmes des Premières nations. Lors des entrevues et de la consultation initiale avec traducteurs, on s’est aperçu qu’il n’y avait pas de terme uniforme pour ménopause en ojibway ou en oji-cri. Une expression communément rencontrée est « ce moment où les règles cessent » : cette phrase peut être utilisée par les soignants pour entamer la discussion. L’intérêt des participantes pour ce sujet et leur désir d’en savoir davantage semblent indiquer qu’elle souhaitent que leurs soignants soulèvent cette question.

CONCLUSION

Cette étude souligne l’importance de comprendre les différents éléments qui influencent la perception qu’une femme a de la ménopause. On pourrait amener les patientes à parler davantage de la ménopause si on leur donnait l’occasion ou l’option d’en discuter avec ceux qui les soignent. Les soignants devraient aussi prendre garde de ne pas associer d’idées préconçues à la signification et à l’importance de l’expérience de la ménopause.

Menopause is a universal and individualized experience. It is a complex process, influenced by biological, psychological, and cultural factors.

Research examining cross-cultural symptoms suggests that menopausal experiences vary among societies and groups.1–6 It is unclear whether reported menopausal differences among ethnicities relate to variations in occurrence, perception, or reporting of symptoms7,8 or to methodologic challenges of cross-cultural inquiry.9

This study was initiated by a group of caregivers in northwestern Ontario who identified a lack of both documented and anecdotal information on First Nations women’s experiences with menopause.

An anthropologic approach views biological processes, such as menopause, as being mediated through cultural understanding, socioeconomic conditions, and social circumstances.10 Kaufert, a Manitoba anthropologist, and Gilbert suggest a cultural stereotype of the menopausal experience can shape the individual experience, including the expected symptoms.10

A greater understanding of First Nations women’s experiences with and perspectives of menopause by primary health care providers is imperative to providing effective and holistic care to this underserviced population. This study might also have implications for further research in this area among aboriginal groups across Canada.

Literature review

Seven databases (HealthSTAR, HAPI [Hispanic American Periodicals Index], EMBASE, OVID MEDLINE, OVID Nursing Database, AMED [Allied and Complementary Medicine Database], and PsycINFO) were searched to find articles on North American aboriginal women and menopause published in the past 30 years. The search revealed scant findings: 1 literature review, 1 mixed-methods study, and 3 qualitative studies.

The 2002 literature review by Webster11 revealed 4 early studies between 1891 and 1963, which found that menopause had a small and possibly positive effect on aboriginal women’s way of life.11 There was documentation of fewer vasomotor symptoms in aboriginal women, but these summarized studies were small and had incomplete methodologies.

A primarily quantitative study of 150 Blackfeet women in Montana examined the timing of menopause. They found early age at menarche and low household income were associated with a delaying effect on menopause.12

Three interesting qualitative studies explored the experiences of aboriginal women: In 2000, 23 focus groups consisting of Hispanic, Navajo, and white women (N = 158) in New Mexico explored ethnic variations in women’s attitudes toward and experiences with menopause.13 The study revealed that women across cultures were much more alike than they were different regarding their attitudes toward menopause, but more traditional women (ie, Navajo women and Latina immigrants) did relate fewer or no menopausal symptoms. Factors differentiating traditional women from modern women included diet, lifestyle, parity, and experience of a ceremony upon menarche. All groups identified a lack of information, wished that women in their families had better prepared them for menopause, and expressed dissatisfaction with doctor-patient communication.13

A 2005 study in Nova Scotia employing focus groups with Mi’kmaq women (N = 42) revealed that participants “know little about the mechanics of menopause but understand a great deal about holistic change of life.”14 The menopausal time of life was marked by evolving and changing relationships, acceptance of aging and change, a time of rest, an increased focus on self, and a time of freedom from childbearing and the constraints of women’s roles. Women’s expectations of menopause were shaped by the experiences of women in their families, despite the fact that most family members did not talk about menopause or reproductive change. Misinformation and stories of suffering contributed to negative and fearful expectations. Self-perceptions were described as overwhelmingly positive; women who had entered menopause tended to experience an increased sense of autonomy and were viewed as respected elders. Doctors were perceived as knowing little about menopause beyond symptoms and details of hormone replacement therapy.14

In 1991, a focus group of 8 Mohawk women in Quebec, who met over an 8-week period, placed menopause in the continuum of life.15 Conceptions of time were important. These women’s menopausal experiences involved a time of shifting priorities from family to self, a desire to spend time meaningfully, and a perception of self along one’s life trajectory.15

METHODS

This study employed a phenomenologic approach using qualitative in-depth interviews. The semistructured interview questions were developed in a bicultural, interdisciplinary setting (Box 1). Additional consultation with a network of 5 interpreters was done to select appropriate wording of interview questions, particularly surrounding translation of the word menopause.

Box 1. Semistructured questions used in the interview process.

Can you tell us about the age at which you had your last period?

What did you know about it?

- Did your mother, sisters, aunts, or grandmothers ever tell you about it?

- When was that?

- What did they tell you?

- Did you know enough about it when it happened to you?

- How did you find out information?

- What did you need to know more about?

When it happened to you, what did you experience? How old were you then?

When it happened to you, how did you think about it? How did you feel about it?

Did you feel good or bad about it?

In your circle of friends and family, is it discussed? And what is said?

If you were going to explain it to a younger woman, what would you tell her?

Is there information that you would have liked to know before it started or during the early stages? Can you tell what sort of things might have been helpful?

Is there anything else you would like doctors and nurses to know about this topic?

First Nations consultation

The National Aboriginal Health Association’s research principles of ownership, control, access, and possession were respected and followed.16 The chiefs of each of the 4 targeted First Nations communities granted the team permission to interview women in their respective communities. The First Nations Health Advisor to the Sioux Lookout Meno Ya Win Health Centre (SLMHC) was involved in the design and analysis stages of the project and guided the team toward a culturally appropriate process, and also approved the final draft of the manuscript before submission for publication. Health directors of the communities were consulted and provided research support where available. The SLMHC Elders’ Council and 10 of the staff interpreters were involved in the project and were given the opportunity to provide feedback to the research team. Ethics approval was granted by the SLMHC.

Data collection

Convenience sampling techniques were used to recruit 18 First Nations women, 9 from Sioux Lookout and 9 from the 4 surrounding First Nations communities. Participants who were either perimenopausal or postmenopausal by way of natural or surgical menopause were asked to participate. Potential participants were identified by the research team, community health workers, community leaders, and by word of mouth.

Each interview was conducted by 2 female researchers, who took field notes and audiotaped interviews. All but 2 interviews were transcribed verbatim; the audio files of those 2 interviews were lost and analyses were based on the interviewers’ field notes alone. Interpreters were used as required.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed for thematic patterns. Five researchers independently analyzed the interviews for main concepts and assigned them codes. The collated codes were then organized into thematic categories and overarching themes by 3 researchers using an immersion and crystallization approach.

FINDINGS

The first thing we learned from our initial consultations with our First Nations researchers and elders was that there was no consistent word for menopause in the regional languages of Ojibway and Oji-Cree. It was commonly referred to as “that time when periods stopped.” We adopted this terminology and only used the word menopause when the participant introduced it. The second finding was that many participants began their narrative about menopause by discussing menarche experiences. These stories noted onset of menses with or without traditional ceremonies as well as residential school menarche experiences.

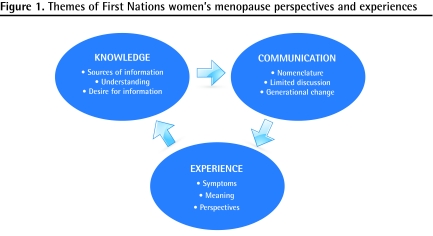

Thematic analysis delivered 3 overarching themes regarding menopause among First Nations women: knowledge, communication, and experience (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Themes of First Nations women’s menopause perspectives and experiences

Knowledge

Sources of information about menopause varied. Nine of the 18 women gained some sort of information from their mothers. One woman described open communication with her mother who also provided her with comprehensive information:

I knew it was the next stage in the woman’s stage[s] of life ... because my mother was very open with us like that. I mean talking about the woman, I mean the feminine side, I mean what happens to a female. So we would chat, and [with respect to] that part we knew what my mother was going through.

The other 8 women received information that was limited to the cessation of menstruation at a certain age or a description of the phases of life:

My mom just used to tell me that there’s a certain age that I wouldn’t get my period anymore. That’s about it. There were no stories or anything like that.

She, my grandmother, said, “as I’m sitting here, I have these different symptoms.” Again, I didn’t understand—I was about 12 or 13 and I was sitting with her, and she said to me, “One day your monthly cycle will go away and your body will just do things that you know [are] going to be different within you.” But she didn’t describe the different symptoms.

Other sources of information regarding menopause included books, other women (eg, older women, coworkers, and sisters), and health care providers. Some women received either no information or misinformation. One participant thought she was pregnant when her periods stopped and another heard from her aunt that premature menopause was caused by having “so much on your mind, so much anger, or [by being] upset or depressed or something.”

For many women information and understanding were limited:

And that time, when I’m feel[ing] sweaty and splash like that—really hot—I just came here and [a nurse] told me that I had the menopause … and I didn’t ask that much, what that mean[t], menopause. I told her “what’s that mean, menopause?” [laughter]

The only thing we know is the very first day and then menopause … it’s just not talked about.

I don’t really know much, like what to experience ... I just know about having hot flashes. I guess dry mouth too. I don’t know.

Oh gosh. It was not something that was talked about. The first time I heard about menopause must have been … I suppose maybe in my twenties, after I had had children already. I read books in the hospital. My grandmothers never talked about it. My mother never talked about it.

Many women described the need for more information and enhanced awareness about what to expect, a greater understanding about the process, and information on relevant medications:

It would be more helpful if they read something regarding menopause, and for them to know what it is that they’re going through and that it’s not going to hurt them, they’re not going to get a disease …. Some of them are probably scared about what’s happening to them.

But the medical part of it, I don’t really know, like what is it that’s happening inside you? And I don’t think that’s something that is known enough, or talked about enough.

Communication

Most participants described menopause as something that was not discussed:

I’m glad [the study is] being done, because it’s almost like [menopause is] hidden, hush-hush, especially when it comes to the older women. Some of them will not talk about that kind of thing.

And there’s so many of them … they don’t want to talk about it. I guess they feel ashamed with it, especially when they have irregular periods, and also when they have menopause .... [T]hey don’t know what to expect.

No. I’m very quiet, like I just take, take, take it, I don’t how to say it … like I know it’s going to happen, I don’t really want to talk about it, like, I know it’s not bugging me or anything about my body. Maybe if it was, I would talk to somebody.

Some women experienced open communication with their sisters and other women:

[W]e would share and comment on how we can help each other. So that nobody’s left out as sisters.

Yes, the girls that I work with, I tell them … I’m getting them ready now.

Many women implicitly identified a generational change in which menopause is increasingly discussed:

I don’t know about now—but those years when I was working and most of the women wouldn’t talk about it ... because of ... they don’t … they don’t even tell when they have a period. Now, today, my girls they’re telling every time they’re having [a] period.

Now that was her time, now my time … being a grandma, it’s [a] very sacred thing. You talk to your granddaughters or even your grandsons about it.

So, it’s all a matter of how you look at it and what generation you were raised to believe.

Several informants described health care provider communication as an element of their menopause experiences. Others identified a need for more information from doctors. A couple of the women expressed a need for doctors to be more holistic. One woman identified the need for doctors to recognize language barriers:

See, I speak English as a second language—I have to translate it up here [points to head] in order for me to understand what the doctor is trying to say to me ... so that way it takes time. But I know that the doctors are so busy and I have that common courtesy not to ask questions with the doctor.

I think doctors, all healers, should understand that it’s not just curative. It involves your mental, your emotional … you know? All that kind of stuff. And to look at it from all angles. They themselves need to understand that in order to be talking to me! [laughing] Because I have feelings, this is my body. This is my experience. Don’t just come to me at one angle.

Experience

Many participants viewed menopause in a neutral or positive way. Some did not identify any value attached to the experience and others saw it simply as the cessation of menstruation: “We didn’t think nothing of it, because we were told [about it] when we were young women. We didn’t think anything. We expected it.” It was described at times as a phase or stage in life. A couple of participants expanded on this concept as a time when women are more respected and seen as sacred:

At that stage too, where women are menopausing, they’re very respect[ed] people in the First Nations members, I guess …. You know, they look at you as a woman with wisdom, especially young girls. So that … I can see it coming with myself.

So you’re considered elderly—not elderly as in old and grey and wrinkled, but old and wise, because you’ve given birth how many times, and you have that knowledge to teach.

[B]elieving in my traditional ways and beliefs as a woman makes a big difference. I don’t think I would have gone through my menopause if I didn’t know my beliefs and my practices. Because in our belief, we hold the woman very sacred; she is the life giver.

Six women experienced no symptoms and 6 expressed symptoms as central to their menopause experience. Mood swings and hot flashes predominated:

[I would tell a younger woman] that they’ll experience moodiness; you cry easily, but you won’t know why they’re crying, I think.

[Y]ou have the night sweats and the irritability because you’re not rested half the time. So I don’t know if it’s the menopause or the diabetes, you know your sugars are going out of whack and you’re feeling … I don’t know.

Yeah, like a couple days now and today, this morning, [I had hot flashes]. I was kind of scared, like I didn’t know what was happening.

I still have this feeling of having your bones become really hot. They feel hot, and it’s very uncomfortable, very uncomfortable.

DISCUSSION

In conventional Western culture, menopause is a well-known term referencing a woman’s multifaceted experience. There is no word for this biological and emotional process in Oji-Cree or Ojibway. It is referred to as “that time when a woman’s bleeding or periods stop.” Whether this nomenclature references a limited characterization of menopause among First Nations women is unclear.

Symptoms reported included hot flashes and mood swings. Sometimes where medical knowledge was not present, folk knowledge or misinformation resided. Health care providers were characterized as having a role to play; however, they need to understand that no uniform term exists for menopause and that multiple symptoms might not always be viewed as connected to the experience.

We have identified a generational change in the patterns of communication, which might result from the medicalization and Westernization of menopause over time. Although most of the women interviewed received little to no information about menopause from previous generations, several women identified the importance of discussing menopause with future generations. The results of this study speak to the importance of understanding the different influences on a woman’s experience with menopause. Many women described thoughts of acceptance of the natural process, yet some did not attach any thoughts or values to menopause at all. Although few women spoke to caregivers, many identified the need for more caregiver information and resources.

Participants in this study told stories that referenced stages of a woman’s life. That several of the participants discussed menarche and pregnancies when asked about menopause is interesting. We had never experienced this in similar discussions with nonaboriginal patients in our clinical practices, where menopause can be discussed in isolation. This might speak to a holistic concept of “woman,” in which discussion of menopause incorporates the beginning of the woman’s story. This might have implications for how clinicians begin such discussions.

Limitations

The convenience sampling technique limits the transferability our findings to other groups, especially outside of the Nishnawbe Aski Nation region of northwestern Ontario. The uniqueness of both the menopause experiences and each of the First Nations communities, respectively, means that these findings might not be generalizable. Results are also limited by the translation of words and concepts across cultures.

Conclusion

Caregivers would be well served to recognize the multiple influences affecting First Nations women’s experiences with menopause and to exercise caution when attaching preconceived ideas of the meaning and importance of menopause to a woman’s personal experience. Some First Nations women might be coming from backgrounds in which menopause is not discussed, yet experience a desire for information and a greater understanding of menopause; or, as one participant put it, “answers to questions that might be hidden somewhere, [which we] are afraid to ask.”

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

North American First Nations women often have different experiences with and perceptions of menopause compared with other Western women; family physicians working in aboriginal areas need to take these differences into account in order to provide effective and comprehensive care for menopausal women.

The word menopause might not exist in many First Nations languages, and physical and emotional symptoms medically attached to the biological process might not be identified as connected to the menopausal experience.

Some First Nations women come from backgrounds in which menopause is not discussed and therefore might experience discomfort with the subject; however, these women might still experience a desire for information, particularly as communication practices regarding the subject of menopause have changed over time.

Health care providers can initiate discussion of menopause by referring to “that time when periods stop,” paying attention to language barriers and acknowledging the various stages in a woman’s life.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Les femmes des Premières nations de l’Amérique du Nord ont souvent une expérience et une perception de la ménopause qui diffèrent de celles des autres femmes des Amériques; le médecin de famille qui travaille chez les Autochtones doit tenir compte de ces différences s’il veut prodiguer des soins efficaces et complets aux femmes ménopausées.

Le terme ménopause pourrait ne pas exister dans plusieurs langues des Premières nations et les symptômes physiques et émotionnels qui accompagnent ce processus biologique pourraient ne pas être vus comme en lien avec la ménopause.

Certaines femmes des Premières nations viennent de milieux où on ne parle pas de ménopause et sont donc mal, à l’aise avec ce sujet; elles pourraient quand même désirer en être informées, surtout depuis que les façons de faire ont évolué avec le temps.

Les soignants peuvent entamer une discussion sur la ménopause et parlant « du temps où les règles cessent » tout en tenant compte des barrières linguistiques et en étant conscients des différentes étapes de la vie d’une femme.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Contributors

Dr Madden, Ms St Pierre-Hansen, Dr Kelly, Ms Cromarty, Ms Linkewich, and Ms Payne all contributed to concept and design of the study; data gathering, analysis, and interpretation; and preparing the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Anderson DJ, Yoshizawa T. Cross-cultural comparisons of health-related quality of life in Australian and Japanese midlife women: the Australian and Japanese Midlife Women’s Health Study. Menopause. 2007;14(4):697–707. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3180421738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dennerstein L, Lehert P, Koochaki PE, Graziottin A, Leiblum S, Alexander JL. A symptomatic approach to understanding women’s health experiences: a cross-cultural comparison of women aged 20 to 70 years. Menopause. 2007;14(4):688–96. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31802dabf0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parsons MA, Obermeyer CM. Women’s midlife health across cultures: DAMES comparative analysis. Menopause. 2007;14(4):760–8. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3180415e54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schnatz PF, Serra J, O’Sullivan DM, Sorosky JI. Menopausal symptoms in Hispanic women and the role of socioeconomic factors. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2006;61(3):187–93. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000201923.84932.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Obermeyer C, Reher D, Saliba M. Symptoms, menopause status, and country differences: a comparative analysis from DAMES. Menopause. 2007;12(4):788–97. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318046eb4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin MC, Block JE, Sanchez SD, Arnaud CD, Beyene Y. Menopause without symptoms: the endocrinology of menopause among rural Mayan Indians. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168(6 Pt 1):1839–43. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90699-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crawford SL. The roles of biologic and nonbiologic factors in cultural differences in vasomotor symptoms measured by surveys. Menopause. 2007;14(4):725–33. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e31802efbb2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Avis NE, Colvin A. Disentangling cultural issues in quality of life data. Menopause. 2007;14(4):708–16. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318030c32b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaufert PA. The social and cultural context of menopause. Maturitas. 1996;23(2):169–80. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(95)00972-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaufert PA, Gilbert P. Women, menopause, and medicalization. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1986;10(1):7–21. doi: 10.1007/BF00053260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Webster RW. Aboriginal women and menopause. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2002;24(12):938–40. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30591-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnston SL. Menopause in Blackfeet women—a life span perspective. Coll Antropol. 2003;27(1):57–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mingo C, Herman CJ, Jasperse M. Women’s stories: ethnic variations in women’s attitudes and experiences of menopause, hysterectomy, and hormone replacement therapy. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9(Suppl 2):S27–38. doi: 10.1089/152460900318740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loppie C. Grandmothers’ choices: Mi’kmaq women’s vision of mid-life change. Pmatisiwin. 2005;3(2):46–78. Available from: www.pimatisiwin.com/online/?page_id=410. Accessed 2010 Jul 21. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buck MM, Gottlieb LN. The meaning of time: Mohawk women at midlife. Health Care Women Int. 1991;12(1):41–50. doi: 10.1080/07399339109515925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.First Nations Centre . OCAP: ownership, control, access and possession. Ottawa, ON: National Aboriginal Health Organization; 2007. Available from: www.naho.ca/firstnations/english/documents/FNC-OCAP_001.pdf. Accessed 2010 Jul 21. [Google Scholar]