Abstract

The purpose of this study was to compare prevalence of anxiety, depression and hostility among three clinically diverse elderly cardiac patient cohorts and a reference group of healthy elders. This was a multicenter, comparative study. A total of 1167 individuals participated: 260 healthy elders and 907 elderly cardiac patients who were at least three months from a hospitalization (478 heart failure patients, 298 post-myocardial infarction patients and 131 post-coronary artery bypass graft patients). Symptoms of anxiety, depression and hostility were measured using the Multiple Affect Adjective Checklist. Prevalence of anxiety, depression and hostility was higher in patients in each of the cardiac patient groups than in the group of healthy elders. Almost three-quarters of patients with heart failure reported experiencing symptoms of depression and the heart failure group had the greatest percentage of patients with depressive symptoms. The high levels of emotional distress common in cardiac patients are not a function of aging, as healthy elders have low levels of anxiety, depression and hostility.

Keywords: anxiety, depression, hostility, heart failure, myocardial infarction

Negative emotions—depression, anxiety and hostility—appear to be more common among cardiac patients than among healthy individuals. Whether this phenomenon is related to cardiac disease alone or to the older age of most cardiac patients is unclear. Cardiac disease incidence increases dramatically with age. Although some researchers have reported that aging is associated with a reduction in anxiety and depression levels, 1 others have documented higher levels of negative emotions in the elderly. 2, 3 Higher rates of suicide are seen in the elderly and the distinctive stresses of aging (e.g., loss of friends and loved ones, retirement) may contribute to substantially higher rates of emotional distress. 4

This argument is not simply academic. Negative emotional states adversely and independently affect quality of life, 5-7 adherence to recommended treatment, 8-10 costs of care 11, 12 and physical outcomes in patients with coronary heart disease and heart failure. 13-21 The risks engendered by negative emotional states may be equal to, or greater than, those seen with traditional risk factors such as presence of diabetes, smoking, elevated low-density lipoprotein and presence of co-morbidities. 5, 19 Despite the importance of negative emotional states to the quality of life, morbidity and mortality outcomes of cardiac patients, clinicians still do not routinely assess for emotional distress as a significant risk factor. 22, 23 One major factor limiting application by clinicians of the evidence regarding negative emotional states is the perception that major confounding factors like age obscure the impact of cardiac disease on emotional states. Thus, the purpose of this study was to determine the impact of cardiac disease on psychological adjustment by comparing the prevalence of depression, anxiety and hostility in 3 elderly cardiac patient groups (outpatients with heart failure, post-myocardial infarction patients, post-coronary artery bypass graft patients) with that of a group of healthy elders.

METHOD

In this multicenter, comparative study, data from three outpatient cohorts of community dwelling cardiac patients and a group of community dwelling elders without known cardiac disease were compared on anxiety, depression and hostility. A multicenter design was used to increase clinical diversity and heterogeneity in the sample in order to enhance generalizability.

Participants

After approval of the respective Institutional Review Boards, cardiac patients were recruited from outpatient clinics at academic medical centers in the Western, Mid-Western and Southern United States, and a cohort of elders without cardiac disease were recruited from senior centers. All participants gave written, informed consent. Cardiac patients who met the following inclusion criteria were enrolled: 1) at least three months from hospitalization; 2) community dwelling; 3) age ≥ 60 years; 4) no cognitive impairment (i.e., patients unable to converse appropriately or those diagnosed with dementia or Alzheimer’s disease); and 5) confirmed diagnosis. Elders without cardiac disease were community dwelling, had no cognitive impairments, were ≥ 60 years, and were free of known cardiac disease.

Measurement

Data were collected from all participants on sociodemographic characteristics by interview and questionnaire. Clinical data were collected about patients by patient interview and medical record review. Anxiety, depression and hostility were measured in participants using the Multiple Affect Adjective Checklist .

Multiple Affect Adjective Checklist

The Multiple Affect Adjective Checklist (MAACL) assesses state anxiety, depression, and hostility. 24, 25 The MAACL is a set of 132 positive and negative adjectives representing each of the three emotional states arranged in alphabetical order. Subjects read through the adjectives and check all those that reflect how they are currently feeling. The instrument is scored by calculating the number of negative adjectives checked and the number of positive adjectives not checked. Higher scores indicate that the respondent has higher levels of the given emotion. Respondents receive a separate score for anxiety, depression and hostility. Standard thresholds for anxiety, depression and hostility have been established at 7, 11, and 7, respectively. This instrument measures the intensity of symptoms of anxiety, depression and hostility and is not used to make a clinical diagnosis. Nonetheless, this instrument was chosen for use in this project because of its clinical utility, ease of comparison among sites, and because dysphoric symptoms, even in the absence of a clinical diagnosis, have been shown to negatively impact outcomes. 18, 26 The MAACL has been used extensively in research; sensitivity, reliability and validity repeatedly have been demonstrated. 24, 25, 27 Reliability was confirmed in this study with calculation of Cronbach’s alpha in each sample for each subscale of the MAACL. In each of the four groups and each of the three subscales, Cronbach’s alpha was > 0.85.

Data analysis

Non-normally distributed data were transformed to better approximate a normal distribution using log transformations as needed. Data were pooled for all sites, as there were no differences in outcomes among the site. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare mean anxiety, depression and hostility scores among the cardiac patient and healthy elder groups. This provided unadjusted comparison of the means. We adjusted for baseline age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, educational level and co-morbidities using subsequent ANCOVA models. When a significant difference was found, post hoc testing using Bonferroni comparisons identified specific group differences. All analyses were conducted using SPSS software, release 13.0. All tests for statistical significance were 2-tailed and α = 0.05.

RESULTS

A total of 1167 individuals participated in this study: 907 cardiac patients and 260 healthy elders. In the cardiac patient group, there were 478 heart failure patients, 298 post-myocardial infarction patients and 131 post-coronary artery bypass graft patients enrolled. Given our age criterion for enrollment in the study, there were no differences in age among the four groups. As expected, however, given the typical cardiac profiles seen in the community, there were a number of differences in baseline characteristics among the groups (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline sample characteristics.

| Characteristics | Healthy elders (n = 260) |

Coronary artery bypass graft (n = 131) |

Post- myocardial infarction (n =298) |

Heart failure (n = 478) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD, y | 67.3 ± 11.4 | 66.3 ± 6.7 | 65.8 ± 7.2 | 65.6 ± 9.2 | 0.078 |

| Female, % | 78.0 | 6.1 | 13.4 | 25.8 | 0.001 |

| ≤ High school, % | 33.7 | 31.7 | 39.4 | 33.6 | 0.393 |

| Married/cohabitate, % | 50.4 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 66.4 | 0.001 |

| Ethnicity | 0.001 | ||||

| Caucasian | 68.1 | 90.8 | 69.1 | 64.4 | |

| African American | 25.8 | 3.8 | 7.0 | 9.4 | |

| Hispanic | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.7 | 7.5 | |

| Other | 6.2 | 5.3 | 7.7 | 8.8 | |

| Hypertension, % | 55.8 | 29.6 | 35.7 | 51.5 | 0.001 |

| Diabetes, % | 16.1 | 14.9 | 12.2 | 38.1 | 0.001 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, mean ± SD, % |

Not assessed |

58.6 ± 10.9 | 50.5 ± 16.9 | 29.5 ± 12.2 | 0.001 |

Group differences in anxiety, depression and hostility scores

Examination of differences in anxiety, depression and hostility scores among the groups revealed significant group differences for each emotion (Table 2). For anxiety, the 3 cardiac patient groups were similar, and expressed significantly higher levels of anxiety than the healthy elders (p = 0.001), whose mean for anxiety was 40% lower than the normative threshold for anxiety. For depression, healthy elders expressed a mean level that was 8% below the threshold for depression, while the heart failure group expressed a mean depression level that was significantly higher than either of the other two cardiac patient groups (p = 0.001). Hostility levels were similar and highest in post-myocardial infarction and post-coronary artery bypass graft patients compared to the healthy elder group in whom hostility was lowest (p = 0.001) and 16% below the normative threshold.

Table 2. Comparison of anxiety, depression and hostility scores among the 3 cardiac patient groups and the healthy elder group.

| Healthy elders (n = 260) |

Coronary artery bypass graft (n = 131) |

Post- myocardial infarction (n =298) |

Heart failure (n = 478) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety score, mean ± SD (95% CI) |

4.2 ± 3.3 (3.8-4.6) |

6.8 ± 4.0 (6.1-7.5) |

6.9 ± 4.6 (6.4-7.4) |

6.9 ± 4.7 (6.3-7.4) |

0.001* |

| Depression score, mean ± SD (95% CI) |

10.2 ± 6.3 (9.4-11.0) |

13.0 ± 5.5 (12.0-13.9) |

12.6 ± 6.5 (11.8-13.3) |

14.2 ± 7.6 (13.4-15.1) |

0.001† |

| Hostility score, mean ± SD (95% CI) |

6.3 ± 3.5 (5.9-6.8) |

8.5 ± 4.1 (7.8-9.2) |

8.2 ± 4.3 (7.7-8.7) |

6.9 ± 4.3 (6.4-7.4) |

0.001‡ |

Higher scores indicate higher levels of anxiety, depression or hostility.

post hoc Bonferroni revealed differences between healthy elder group versus all others

post hoc Bonferroni revealed differences between heart failure and myocardial infarction; and between healthy elders versus all others

post hoc Bonferroni revealed differences between healthy elders versus myocardial infarction and coronary artery bypass; and between heart failure versus myocardial infarction and coronary artery bypass

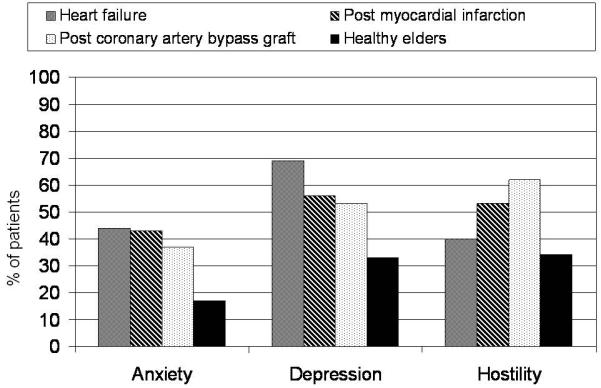

The percentage of cardiac patients in each group exceeding the threshold for anxiety was 37% to 44% compared to only 17% among the healthy elders (Figure 1). With regard to depression, 63% of heart failure patients exceeded the threshold for depression compared to 56% of post-myocardial infarction patients, 53% of post-coronary artery bypass graft patients and only 33% of healthy elders. A total of 62% of post-coronary artery bypass graft patients compared to 34% of healthy elders exceeded the hostility threshold.

Figure 1.

Percent of patients in each group exceeding the published threshold for anxiety, depression and hostility

In order to control for sociodemographic or clinical factors that might also affect anxiety, depression or hostility levels we used ANCOVA models with age as the covariate to adjust for gender, marital status, ethnicity, education level, presence of hypertension or diabetes, and medications used. Within this elderly sample, age did not affect levels of anxiety, depression or hostility, in any model.

There were no interactions between group (i.e., the 3 cardiac patient groups and the healthy elder group) and gender, although there was a main effect of gender for anxiety (p = 0.04) and depression (p = 0.03), but not for hostility. Women expressed significantly greater levels of anxiety and depression than men in all four groups (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of anxiety, depression and hostility scores by gender among the 3 cardiac patient groups and the healthy elder group.

| Healthy elders (n = 260) |

Coronary artery bypass graft (n = 131) |

Post- myocardial infarction (n =298) |

Heart failure (n = 478) |

p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety score, mean ± SD |

Women | 4.4 ± 3.4 | 7.6 ± 4.1 | 8.5 ± 4.6 | 7.2 ± 4.8 | 0.028* |

| Men | 3.6 ± 3.0 | 6.8 ± 4.0 | 6.6 ± 4.5 | 6.7 ± 4.5 | ||

| Depression score, mean ± SD |

Women | 10.4 ± 6.6 | 15.0 ± 4.5 | 14.1 ± 6.4 | 15.0 ± 7.5 | 0.037* |

| Men | 9.1 ± 5.3 | 12.8 ± 5.6 | 12.4 ± 6.5 | 13.9 ± 7.7 | ||

| Hostility score, mean ± SD |

Women | 6.4 ± 3.5 | 9.0 ± 3.1 | 8.8 ± 3.9 | 6.2 ± 4.0 | 0.616† |

| Men | 5.8 ± 3.7 | 8.5 ± 4.2 | 8.1 ± 4.4 | 7.2 ± 4.4 |

Higher scores indicate higher levels of anxiety, depression or hostility.

main effect of gender; no group by gender interaction

no interaction of group by gender, no gender main effect

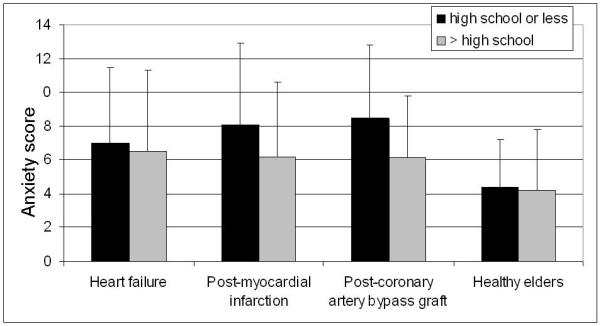

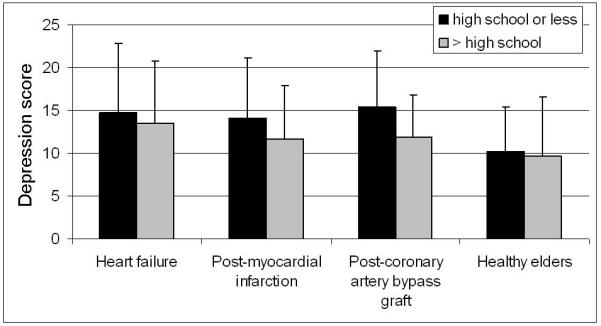

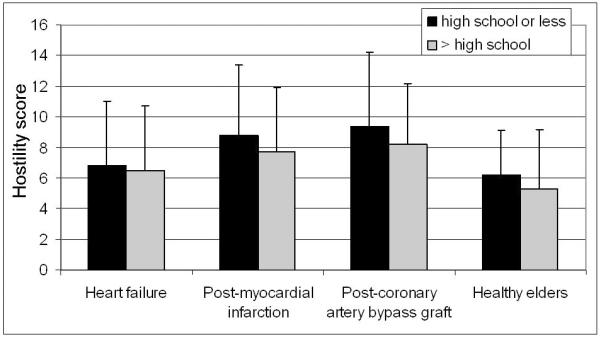

There was no education by group interaction, but there was a main effect of education level. Individuals in each group with only a high school or less education reported experiencing significantly higher levels of anxiety (p = 0.001), depression (p = 0.001) and hostility (p = 0.006) than those who had attended at least some college (Figure 2). In this sample, there was no interaction or main effect of marital status, ethnicity/race, hypertension or diabetes, or medications used on anxiety, depression or hostility level.

Figure 2.

Anxiety (panel A), depression (panel B) and hostility (panel C) levels in each group compared by education level. Individuals in each group with only a high school or less education reported experiencing significantly higher levels of anxiety (p = 0.001), depression (p = 0.001) and hostility (p = 0.006) than those who had attended at least some college.

DISCUSSION

Our findings demonstrate that the higher levels of emotional distress seen in older cardiac patients are not a function of aging, but are directly associated with cardiac disease. Patients with heart failure and patients who were post-myocardial infarction and post-coronary artery bypass grafting had substantially higher levels of anxiety and depression than did individuals in a group of healthy elders. Hostility levels were higher in post-myocardial infarction and post-coronary artery bypass grafting patients than in healthy elders who were similar to heart failure patients. In the healthy elders, mean levels of each emotion were well below the normative threshold for distress, while they were above the threshold for patients in each of the three distinct cardiac groups. Thus, aging does not account for the higher levels of emotional distress seen in cardiac patients.

Our findings demonstrated that of the sociodemographic and clinical variables considered, only gender and educational status affected level of anxiety, depression or hostility and they did so in a consistent fashion among the groups. Those with a high school education or less had higher levels of psychological distress than those with at least some college. Educational attainment often is considered a surrogate of socioeconomic status, which is associated strongly and inversely with poor cardiac outcomes. 28, 29 This relationship is driven not only by the poorer health habits and higher levels of cardiac risk factors seen in individuals of lower educational attainment, but by the chronic stresses of lower socioeconomic status 30 often manifested as depression, anxiety or hostility.

We also noted that women reported higher levels of anxiety and depression in all groups than did men. We and others have previously reported this phenomenon. 5, 31, 32 In each of the cardiac patient groups in this study, women consistently reported levels in excess of the thresholds for anxiety or depression. Given the consistency with the finding that women experience higher levels of psychological distress, future research should explore the relationship between poorer cardiac outcomes among women and higher levels of anxiety and depression. Of note, even though women’s levels of depression were higher than men’s, in each male cardiac patient group the mean level of depression also was higher than the threshold for depression.

Our data indicate that the majority of patients post-myocardial infarction, post-coronary artery bypass, and with heart failure have depressive symptoms, that about 40% of these cardiac patients experience anxiety, and that hostility is apparent in about half. These levels for depression are consistent with those reported in the literature when considering the combined prevalence of clinical diagnoses and symptoms of psychological distress. 33 Neither anxiety nor hostility have been studied in sufficient depth to provide reliable prevalence estimates. The high levels of depression, anxiety and hostility seen in these older cardiac patient samples are of concern for a number of reasons. First, both older age and negative emotions predict short- and long-term morbidity and mortality among heart failure, coronary artery bypass graft, and myocardial infarction patients. 5, 6, 13, 16-18, 21, 34-42 The combined impact of increasing age and negative emotions work together to substantially increase the risk faced by elder cardiac patients for poor quality of life, recurrent cardiac events and increased mortality. Under these circumstances it is imperative that clinicians recognize and appropriately manage negative emotions in their cardiac patients.

Second, emotional distress is modifiable, but only if it is recognized and treated. Although in some cases, anxiety or depression will diminish without treatment, investigators have documented poor resolution of either condition over the long-term. 10, 43 In current clinical practice, recognition and treatment of psychological distress is extremely poor even when levels are high as they are in the current patient sample. 22, 23, 43 There are a number of possible reasons for under-recognition and under-treatment of dysphoric states. 19, 33 Many clinicians believe that emotional distress after a cardiac event is a normal response to illness that will resolve with time. Others fail to appreciate the extent of the problem or believe that they will easily recognize serious emotional distress in their patients when it is present, despite evidence to the contrary. 22, 23 Finally, there is a general lack of knowledge among healthcare providers regarding appropriate assessment and treatment of emotional distress with many clinicians believing that assessment is too difficult and that treatment options are few.

Third, emotional distress, particularly anxiety and depression, are easily assessed in the clinical setting by non-psychiatrists and there are effective nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatments. 19, 33, 44 Despite the notable failure of some large-scale intervention trials to demonstrate a significant impact on outcomes, 45 others have demonstrated that reducing emotional distress with nonpharmacologic interventions can reduce mortality, 46 particularly in the subset of patients with high distress. 47 Pharmacologic management of depression and anxiety is effective and safe in the elderly 48 when medications appropriate for cardiac patients (e.g. selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) are used judiciously.

Limitations

This study had some potential limitations. We assessed for severity of symptoms of three dysphoric states, anxiety, depression and hostility, but did not make clinical diagnoses. However, existing evidence indicates that even symptoms of anxiety and depression are of major importance in predicting poor outcomes in cardiac patients. 5, 18, 49

There were some sociodemographic differences between the healthy elder group and the cardiac patient groups that were unavoidable given the demographics typical of healthy elders. These differences had the potential to affect our findings. There were significantly more women in the healthy elder group than in any of the cardiac patient groups, but given the higher levels of anxiety seen in all groups among women this probably resulted in over-estimation of levels of psychological distress in the healthy elder group. The end result of this bias would be to decrease the differences between the healthy elders and the cardiac patient groups, thus it likely that differences in psychological distress between healthy elders and cardiac patients are even more dramatic than we have shown here.

Conclusion

The emotional distress seen in elderly cardiac patients is not a function of aging, as healthy elders, even those with hypertension and diabetes, have low levels of anxiety, depression and hostility. Women and those of lower educational attainment are particularly at risk for psychological distress. Patients with heart failure exhibit the highest levels of depression, while heart failure and post-myocardial infarction patients experience the highest levels of anxiety, and post-coronary artery bypass patients the highest levels of hostility. The findings add to the burgeoning literature demonstrating the increased prevalence of negative emotions in cardiac patients, dispel the notion that negative emotions in elderly cardiac patients are a function of aging, and call for more aggressive assessment and management of psychological distress.

Acknowledgements

The project described was supported in part by (1) a Center grant, 1P20NR010679 from NIH, National Institute of Nursing Research. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Nursing Research or the National Institutes of Health, (2) Funding from a National American Heart Association Established Investigator Award, and (3) a Western Division American Heart Association grant (NCR,133-09).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Debra K. Moser, University of Kentucky, College of Nursing, Lexington, KY.

Kathleen Dracup, University of California, San Francisco, School of Nursing, CA.

Lorraine S. Evangelista, University of California, Los Angeles, School of Nursing, CA.

Cheryl Hoyt Zambroski, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL.

Terry A. Lennie, University of Kentucky, College of Nursing, Lexington, KY.

Misook L. Chung, University of Kentucky, College of Nursing, Lexington, KY.

Lynn V. Doering, University of California, Los Angeles, School of Nursing, CA.

Cheryl Westlake, California State University, Fullerton, School of Nursing, CA.

Seongkum Heo, Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN.

References

- 1.Jorm AF. Does old age reduce the risk of anxiety and depression? A review of epidemiological studies across the adult life span. Psychol Med. 2000;30(1):11–22. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799001452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller DK, Malmstrom TK, Joshi S, et al. Clinically relevant levels of depressive symptoms in community-dwelling middle-aged African Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(5):741–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barefoot JC, Mortensen EL, Helms MJ, et al. A longitudinal study of gender differences in depressive symptoms from age 50 to 80. Psychol Aging. 2001;16(2):342–5. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.16.2.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juurlink DN, Herrmann N, Szalai JP, et al. Medical illness and the risk of suicide in the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(11):1179–84. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.11.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mallik S, Krumholz HM, Lin ZQ, et al. Patients with depressive symptoms have lower health status benefits after coronary artery bypass surgery. Circulation. 2005;111(3):271–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000152102.29293.D7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rumsfeld JS, Havranek E, Masoudi FA, et al. Depressive symptoms are the strongest predictors of short-term declines in health status in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(10):1811–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rumsfeld JS, Magid DJ, Plomondon ME, et al. History of depression, angina, and quality of life after acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J. 2003;145(3):493–9. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2003.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ziegelstein RC, Fauerbach JA, Stevens SS, et al. Patients with depression are less likely to follow recommendations to reduce cardiac risk during recovery from a myocardial infarction. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160(12):1818–23. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.12.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(14):2101–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayou RA, Gill D, Thompson DR, et al. Depression and anxiety as predictors of outcome after myocardial infarction. Psychosom Med. 2000;62(2):212–9. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200003000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F, Gravel G, et al. Depression and health-care costs during the first year following myocardial infarction. J Psychosom Res. 2000;48(4-5):471–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sullivan M, Simon G, Spertus J, et al. Depression-related costs in heart failure care. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(16):1860–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.16.1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaput LA, Adams SH, Simon JA, et al. Hostility predicts recurrent events among postmenopausal women with coronary heart disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(12):1092–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strik JJ, Lousberg R, Cheriex EC, et al. One year cumulative incidence of depression following myocardial infarction and impact on cardiac outcome. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56(1):59–66. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00380-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barth J, Schumacher M, Herrmann-Lingen C. Depression as a risk factor for mortality in patients with coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(6):802–13. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000146332.53619.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strik JJ, Denollet J, Lousberg R, et al. Comparing symptoms of depression and anxiety as predictors of cardiac events and increased health care consumption after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(10):1801–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F, Gravel G, et al. Long-term survival differences among low-anxious, high-anxious and repressive copers enrolled in the Montreal heart attack readjustment trial. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(4):571–9. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000021950.04969.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lesperance F, Frasure-Smith N, Talajic M, et al. Five-year risk of cardiac mortality in relation to initial severity and one-year changes in depression symptoms after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2002;105(9):1049–53. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rozanski A, Blumenthal JA, Davidson KW, et al. The epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management of psychosocial risk factors in cardiac practice: the emerging field of behavioral cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(5):637–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaccarino V, Kasl SV, Abramson J, et al. Depressive symptoms and risk of functional decline and death in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38(1):199–205. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01334-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matthews KA, Gump BB, Harris KF, et al. Hostile behaviors predict cardiovascular mortality among men enrolled in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Circulation. 2004;109(1):66–70. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000105766.33142.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Brien JL, Moser DK, Riegel B, et al. Comparison of anxiety assessments between clinicians and patients with acute myocardial infarction in cardiac critical care units. Am J Crit Care. 2001;10(2):97–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ziegelstein RC, Kim SY, Kao D, et al. Can doctors and nurses recognize depression in patients hospitalized with an acute myocardial infarction in the absence of formal screening? Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005;67(3):393–7. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000160475.38930.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zuckerman M, Lubin B. Manual for the Multiple Affect Adjective Checklist. Educational and Industrial Testing Service; San Diego, CA: 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lubin B, Zuckerman M, Woodward L. Bibliography for the Multiple Affect Adjective Check List. Educational and Industrial Testing Services; San Diego, CA: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moser DK, Dracup K. Is anxiety early after myocardial infarction associated with subsequent ischemic and arrhythmic events? Psychosom Med. 1996;58(5):395–401. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199609000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacobsen BS, Munro BH, Brooten DA. Comparison of original and revised scoring systems for the Multiple Affect Adjective Check List. Nurs Res. 1996;45(1):57–60. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199601000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gonzalez MA, Rodriguez Artalejo F, Calero JR. Relationship between socioeconomic status and ischaemic heart disease in cohort and case-control studies: 1960-1993. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27(3):350–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/27.3.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Philbin EF, Dec GW, Jenkins PL, et al. Socioeconomic status as an independent risk factor for hospital readmission for heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87(12):1367–71. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01554-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marmot MG, Bosma H, Hemingway H, et al. Contribution of job control and other risk factors to social variations in coronary heart disease incidence. Lancet. 1997;350(9073):235–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)04244-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moser DK, Dracup K, McKinley S, et al. An international perspective on gender differences in anxiety early after acute myocardial infarction. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003;65(4):511–6. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000041543.74028.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gottlieb SS, Khatta M, Friedmann E, et al. The influence of age, gender, and race on the prevalence of depression in heart failure patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(9):1542–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dobbels F, De Geest S, Vanhees L, et al. Depression and the heart: a systematic overview of definition, measurement, consequences and treatment of depression in cardiovascular disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2002;1(1):45–55. doi: 10.1016/S1474-5151(01)00012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Albert CM, Chae CU, Rexrode KM, et al. Phobic anxiety and risk of coronary heart disease and sudden cardiac death among women. Circulation. 2005;111(4):480–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153813.64165.5D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gustafsson F, Torp-Pedersen C, Seibaek M, et al. Effect of age on short and long-term mortality in patients admitted to hospital with congestive heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2004;25(19):1711–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Faris R, Purcell H, Henein MY, et al. Clinical depression is common and significantly associated with reduced survival in patients with non-ischaemic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2002;4(4):541–51. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(02)00101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Junger J, Schellberg D, Muller-Tasch T, et al. Depression increasingly predicts mortality in the course of congestive heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7(2):261–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ariyo AA, Haan M, Tangen CM, et al. Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group Depressive symptoms and risks of coronary heart disease and mortality in elderly Americans. Circulation. 2000;102(15):1773–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.15.1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schulz R, Beach SR, Ives DG, et al. Association between depression and mortality in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(12):1761–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.12.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang W, Kuchibhatla M, Cuffe MS, et al. Prognostic value of anxiety and depression in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2004;110(22):3452–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000148138.25157.F9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martinez-Selles M, Garcia Robles JA, Prieto L, et al. Heart failure in the elderly: age-related differences in clinical profile and mortality. Int J Cardiol. 2005;102(1):55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rich MW, McSherry F, Williford WO, et al. Effect of age on mortality, hospitalizations and response to digoxin in patients with heart failure: the DIG study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38(3):806–13. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01442-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grace SL, Abbey SE, Irvine J, et al. Prospective examination of anxiety persistence and its relationship to cardiac symptoms and recurrent cardiac events. Psychother Psychosom. 2004;73(6):344–52. doi: 10.1159/000080387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Konstam V, Moser DK, De Jong MJ. Depression and anxiety in heart failure. J Card Fail. 2005;11(6):455–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Berkman LF, Blumenthal J, Burg M, et al. Effects of treating depression and low perceived social support on clinical events after myocardial infarction: the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients (ENRICHD) Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2003;289(23):3106–16. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Denollet J, Brutsaert DL. Reducing emotional distress improves prognosis in coronary heart disease: 9-year mortality in a clinical trial of rehabilitation. Circulation. 2001;104(17):2018–23. doi: 10.1161/hc4201.097940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cossette S, Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F. Clinical implications of a reduction in psychological distress on cardiac prognosis in patients participating in a psychosocial intervention program. Psychosom Med. 2001;63(2):257–66. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200103000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cervera-Enguix S, Baca-Baldomero E, Garcia-Calvo C, et al. Depression in primary care: effectiveness of venlafaxine extended-release in elderly patients; Observational study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2004;38(3):271–80. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bush DE, Ziegelstein RC, Tayback M, et al. Even minimal symptoms of depression increase mortality risk after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88(4):337–41. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01675-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]