Abstract

Previous work has proposed rhoptry protein 2 (ROP2) as the physical link that tethers host mitochondria to the parasitophorous vacuole membrane (PVM) surrounding the intracellular parasite, Toxoplasma gondii. A recent analysis of the ROP2 structure, however, raised questions about this model. To determine whether ROP2 is necessary, we created a parasite line that lacks the entire ROP2 locus consisting of the three closely related genes, ROP2a, ROP2b and ROP8. We show that this knockout mutant retains the ability to recruit host mitochondria in a manner that is indistinguishable from the parental strain, re-opening the question of which molecules mediate this association.

Keywords: Apicomplexa, ROP2, ROP8, Pseudokinase, Parasitophorous vacuole membrane, Mitochondria

Toxoplasma gondii is an obligate intracellular parasite with an almost unparalleled mammalian host range including humans. The rapidly proliferating form known as the tachzyoite invades almost any nucleated cell type. This is an active process involving an invagination of the host plasma membrane to create a parasitophorous vacuole (PV), within which the parasite undergoes several rounds of replication. The PV membrane (PVM), which constitutes the literal interface between the parasite and the host cell, is a highly specialized and unique membrane that generally lacks integral membrane proteins of host cell origin, but is extensively modified by secreted parasite proteins (Bradley and Sibley, 2007; Boothroyd and Dubremetz, 2008). These parasite proteins derive from rhoptries and dense granules, distinct secretory organelles that discharge their contents during invasion. Strikingly, Toxoplasma is able to extensively associate with host mitochondria at the PVM in a process that is pathogen-specific; Neospora caninum, another Apicomplexan parasite, does not exhibit this association. This phenomenon is observed in vitro and in cells from infected animals (Jones and Hirsch, 1972; de Melo et al., 1992)

One of the first proteins identified within the rhoptries was rhoptry protein 2 (ROP2) (Herion et al., 1993). This protein is part of an extensive family in Toxoplasma that all have a conserved protein kinase fold and many of which have an N-terminal extension that includes two to three amphipathic helices (El Hajj et al., 2006). The ROP2 gene is tandemly triplicated in the Toxoplasma RH strain genome and the three genes have been dubbed ROP2a, ROP2b and ROP8 (Beckers et al., 1997). Previous work implicated ROP2 as the molecule responsible for attaching host cell mitochondria to the PVM. It was postulated that ROP2 is a transmembrane protein that is anchored in the PVM and attaches to passing host mitochondria by virtue of its cytosolically exposed, processed N-terminus, which resembles a mitochondrial import signal. It was proposed that mitochondria recognize and begin to import ROP2 but cannot complete the process due to the firm anchoring in the PVM. Instead, the mitochondria are drawn down into close apposition with the PVM. This model was supported by reports showing that: i) the N-terminus of recombinant ROP2 is protected from trypsin cleavage after incubation with mitochondria in vitro (Sinai and Joiner, 2001) and ii) the targeted depletion of ROP2 using a ribozyme-modified antisense RNA strategy results in the loss of association of host cell mitochondria with the PVM (Nakaar et al., 2003). Neither study, however, proved the model and recent results on the structure of ROP2 (Labesse et al., 2009), its topology on the PVM (El Hajj et al., 2007) the function of its N-terminus (Reese and Boothroyd, 2009) and the finding that it is part of an extensive, conserved family of proteins (El Hajj et al., 2006) have called the model into question.

To definitively test whether ROP2 plays a crucial role in PVM-mitochondrial association, we created a line deficient in ROP2a, ROP2b and ROP8 expression and assayed for PVM-mitochondrial association. The results strongly suggest that none of these three genes are involved in PVM-mitochondrial association.

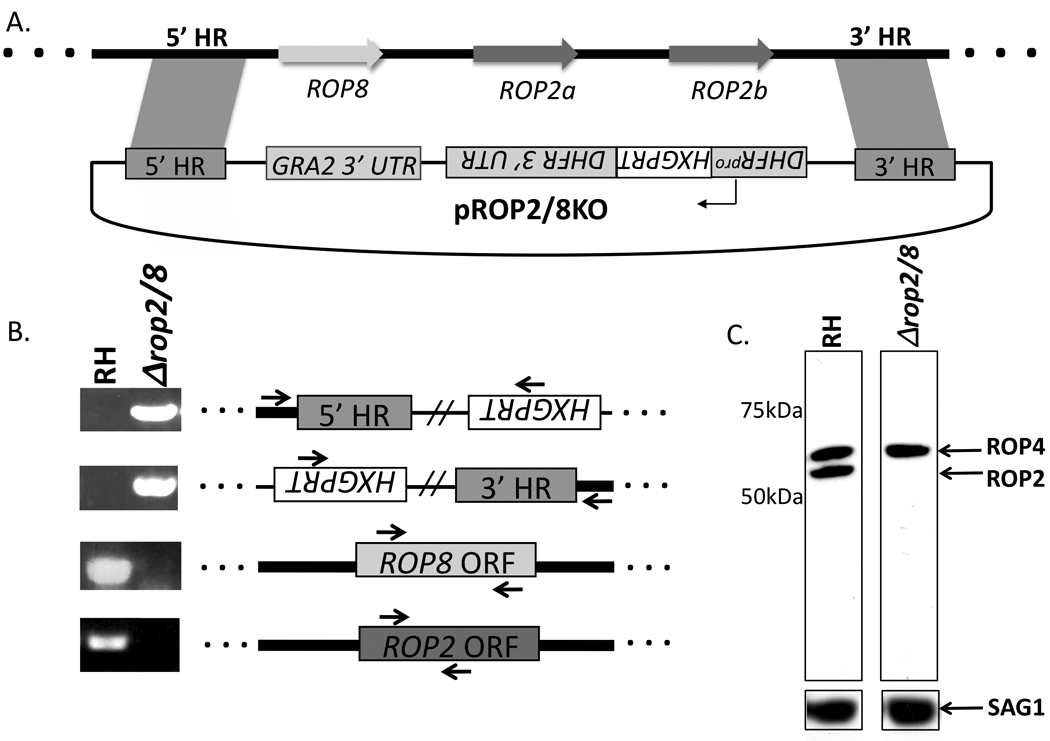

Early work led to the suggestion that ROP2 serves as the physical link between the Toxoplasma PVM and host mitochondria. To test this model we deleted the ROP2/8 locus and assessed the phenotype in RH strain tachyzoites, the same strain used in the earlier reports on ROP2’s involvement in PVM-mitochondrial association. At the ROP2 locus (Fig. 1A), there are three tandem copies of ROP2-related sequences identified by analysis of cosmids containing the ROP2 gene from RH parasites. The most upstream gene in this locus is ROP8 and it has 85% nucleic acid identity and 75% predicted amino acid identity to the downstream ROP2a and ROP2b. The latter two genes are reported to be identical to each other throughout the open reading frames (ORFs) and flanking 5’ and 3’ untranslated regions (UTRs) (Beckers et al., 1997). To avoid the possibility that homologous recombination directed at removing individual members of this trio of genes might result in misintegration due to sequence homology, the entire ROP2/8 region was targeted for deletion. This approach had the added benefit of avoiding issues of redundancy, given the similarity of the three genes (i.e., deletion of one gene might have no phenotype because its function was redundantly provided by the other two).

Fig. 1.

Generation of a Toxoplasma knockout (KO) line deficient in genes encoding rhoptry proteins 2a, 2b and 8 (ROP2/8). (A) Plasmid pROP2/8KO, used to transform the Toxoplasma RH wild type strain, contains an 811 bp homology region of 5’ ROP8 flanking sequence (5’ homology region or 5’HR) and 1,031 bp of 3’ ROP2b flanking sequence (3’ HR). Hypoxanthine-xanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase (HXGPRT) is the selectable marker driven by the Toxoplasma dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) promoter; the arrows represent the ROP8, ROP2a, and ROP2b open reading frames (ORFs). The thick black line flanked by dots represents genomic DNA (gDNA) and the thin black line symbolizes pROP2/8KO. Figure not drawn to scale. (B) gDNA from RH wild type and RHΔrop2/8 was PCR amplified for regions indicated by arrows and loaded on a 1% agarose gel. (C) RH and RHΔrop2/8 lysates corresponding to approximately 1 × 106 parasites were loaded in each lane. The membrane was probed with monoclonal antibody T3A47 against ROP2/4 and, after stripping, with polyclonal rabbit anti-SAG1 antibodies.

A construct for deletion of the ROP2/8 region was created from the parental pTKO vector (G. Zeiner and J.C. Boothroyd, unpublished data) that contains the selectable HXGPRT marker driven by the Toxoplasma dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) promoter (Donald and Roos, 1998). Briefly, an 811 bp region of genomic DNA corresponding to sequences upstream of the ROP8 start codon (5’ homology region or 5’ HR) and a 1,031 bp region of genomic DNA corresponding to sequences downstream of ROP2b (3’ HR) were cloned into NotI/EcoRV and HindIII/NheI restriction sites that flank the T. gondii HXGPRT gene and GRA2 3’ UTR in the pTKO vector, respectively (Fig. 1A). Primers for amplification of the 5’-insert were AAGCGGCCGCGGGCATCGAG and GATATCCTCTGCCGCAATCGT and for the 3’-insert, they were CCAAGCTTCGGGCAAGAGGCA and AAGCTAGCCGCAATCGCTGTA. After verification by sequencing, pROP2/8KO was electroporated into the parental RHΔhxgprt strain, deleted for the hypoxanthine-xanthine-guanine phosphoribosyl transferase (HXGPRT) gene and referred to as RH wild type in this text, with 20 µg of linearized pROP2/8KO. Parasites were maintained by serial passage in human foreskin fibroblast (HFF) monolayers. HFFs were grown in complete DMEM (cDMEM; (Invitrogen) supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin) and 10% heat-inactivated FCS. Clones that successfully integrated the knockout vector and were positive for HXGPRT expression were isolated by applying mycophenolic acid and xanthine selection (Donald et al., 1996), then clonally expanded.

To confirm double homologous integration of the pROP2/8KO vector and thus disruption of the ROP2/8 locus, a series of PCRs were performed on the genomic DNA isolated from selected clones (Fig. 1B). Primers were chosen that tested the integrity of both the 5’- and 3’-integration events as well as the absence of the coding region for each of the three genes. For the PCR, primers specific for HXGPRT and genomic DNA outside the 5’ HR and 3’ HR were used to test whether the pROP2/8KO vector had integrated by double homologous recombination. These primer pairs were CCTGCTTCCGTGCTGCGGAAG and CTGCCCGTCTCTCGTTTCCT, and CCTGTCGCGAAAGATTGAC and GGCCTCAGACGATCGACAGAA, respectively. Primers specific for the ROP2 arginine-rich amphipathic helix domain (RAH; GCGCGAATTCTCAGGAAGCGGCCGAGG and GCGCCTCGAGTCAAAACTCGTCGGGAGGGAATACAGG) (Reese and Boothroyd, 2009) and the ROP8 ORF (AGGCTCATGGTTGGAGCAGGAA and GCGGCGCGTCCTTGGTATT) were used to amplify the ROP2a/b and ROP8 genes, respectively. The results showed that the RHΔrop2/8 strain does indeed possess the correctly integrated HXGPRT gene and lacks the ROP2/8 coding regions.

For verification of the disruption of the locus and thus ablation of ROP8 and ROP2a/2b expression, Western blot analysis was performed using the monoclonal T34A7 antibody (Sadak et al., 1988). Cells were lysed in SDS buffer and resolved on an 8% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Following gel transfer, membranes were blocked with PBS-0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T) and 0.05% non-fat dry milk for 1 h and then incubated with monoclonal antibody (mAb) T34A7 (specific for ROP2a/b and ROP4) at a 1:1,000 dilution in blocking solution overnight. The blot was washed three times in PBS-T and then incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse antibodies at 1:1,500. The membrane was stripped (Invitrogen stripping buffer) and reprobed with rabbit anti-SAG1 antibody at a 1:10,000 dilution in blocking solution for 1 h. After three PBS-T washes, the blot was incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit antibodies at a 1:3,000 dilution and developed using a chemiluminescence system (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, Ill., USA). T34A7 recognizes two bands verified by mass spectrometry to be ROP2a/b (Fig. 1C; lower band) and ROP4 (upper band; Hajj et al., 2006). To control for equal loading, the blot was also probed with surface antigen 1 (SAG1) antibody. These data show that the RHΔrop2/8 is ablated for ROP2 expression as indicated by loss of the ROP2 band (Fig. 1C). Although we were unable to verify loss of ROP8 expression due to the lack of a ROP8-specific antibody, the PCR data unambiguously indicated a deletion of the ROP8 gene. Together, the genomic PCR and Western blot analysis confirmed the successful deletion of the ROP2/8 locus in the RHΔrop2/8 knockout parasite. These results also indicated that there were no additional genes present in the RH genome outside this region that, under these conditions, express detectable levels of co-migrating, cross-reactive ROP2 proteins.

If secreted ROP2 mediates the tight association between host mitochondria and PVM, then ROP2-deficient parasites should show a marked decrease in this association..To test this, we assessed the association with host cell mitochondria using fluorescence microscopy. HFFs were grown to confluency in 24-well plates. For staining with MitoTracker (Invitrogen), medium was replaced with pre-warmed cDMEM containing MitoTracker at a concentration of 50 nM. After 30 min of incubation at 37°C, cells were washed and then infected with RH wild type, RHΔrop2/8 or N. caninum parasites (the closely related genus N. caninum does not recruit host mitochondria (Lindsay et al., 1993) and so served as a negative control) in pre-warmed cDMEM.

To synchronize invasion, parasites were allowed to attach to HFF monolayers seeded on coverslips for 20 min in a high potassium buffer (44.7 mM K2SO4, 10 mM MgSO4, 106 mM sucrose, 5 mM glucose, 20 mM Tris–H2SO4, 3.5 mg/ml BSA, pH 8.2) (Endo et al., 1987) at room temperature (RT), after which the buffer was replaced with 37°C cDMEM and cells were shifted to 37°C. Invasion was allowed to proceed for 4 h, after which infected cells were washed in PBS and fixed in pre-warmed cDMEM plus 10% FCS containing 3.7% formaldehyde for 15 min. Cells were washed with PBS and mounted in VectaShield (Vector). Phase and fluorescence images were captured with a Hamamatsu Orca100 CCD on an Olympus BX60 (100x) and processed using Image-Pro Plus 2.0 (MediaCybernetics).

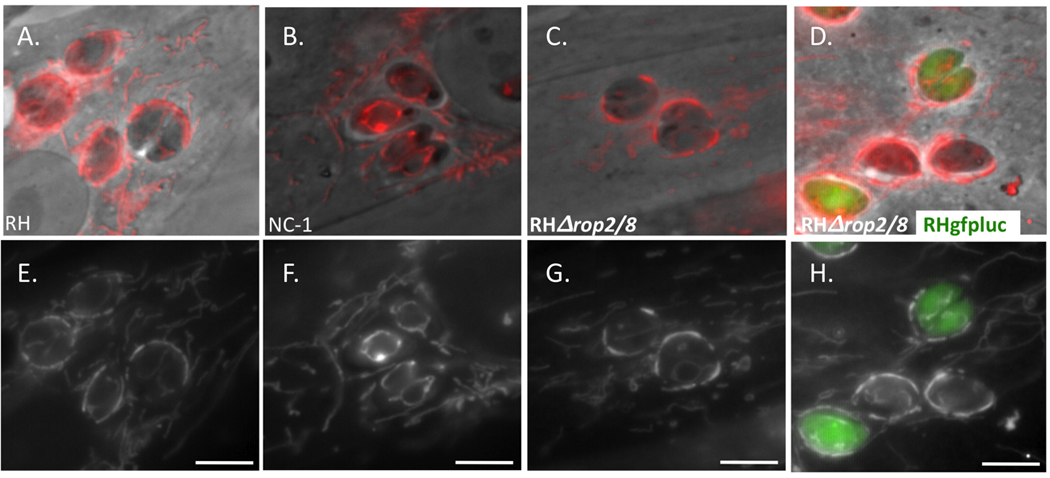

At 4 h p.i., the parental RH strain showed a strong and clear association of host mitochondria around the PVM perimeter (Fig. 2A). The N. caninum control showed the expected lack of such association (Fig. 2B); the parasite’s mitochondria were apparent (within the parasite, itself) but there was little to no staining on the periphery of the PVM. Surprisingly, the RHΔrop2/8 strain appeared to show the same, strong mitochondrial recruitment as the RH wild type parasites (Fig. 2C). To allow direct comparison within the same field, HFFs were co-infected with a strain of RH expressing GFP (RHgfpluc) generated using the plasmid described previously (Saeij et al., 2005), and RHΔrop2/8. Vacuoles containing these two strains were indistinguishable, both exhibiting similarly strong mitochondrial staining around the PVM (Fig. 2D). Examination of cultures infected for just 1 h revealed a similar lack of difference between the wild type and mutant vacuoles (data not shown) although the phenomenon is less obvious and, thus, less easily assessed at this early time. These data suggest that at least in this cell line and with this parasite strain, ROP2 and ROP8 do not play an important role in the interaction between host mitochondria and the PVM.

Fig. 2.

Vacuoles containing Toxoplasma RHΔrop2/8 tachyzoites show no defect in mitochondrial association by light microscopy. Human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs) were labeled for 30 min at 37°C with 50 nM MitoTracker and infected with (A) RH wild type, (B) Neospora caninum (NC-1), (C) RHΔrop2/8, or co-infected with (D) RHgfpluc and RHΔrop2/8. Four hours p.i. monolayers were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde for 15 min at 37°C. Each pair of images (A/E, B/F, C/G, D/H) represents phase contrast (A, B, C and D) or fluorescence (E, F, G and H) of the same field. All images of a particular sort (phase or fluorescence) were taken at the same exposure. Scale bar, 5 µm.

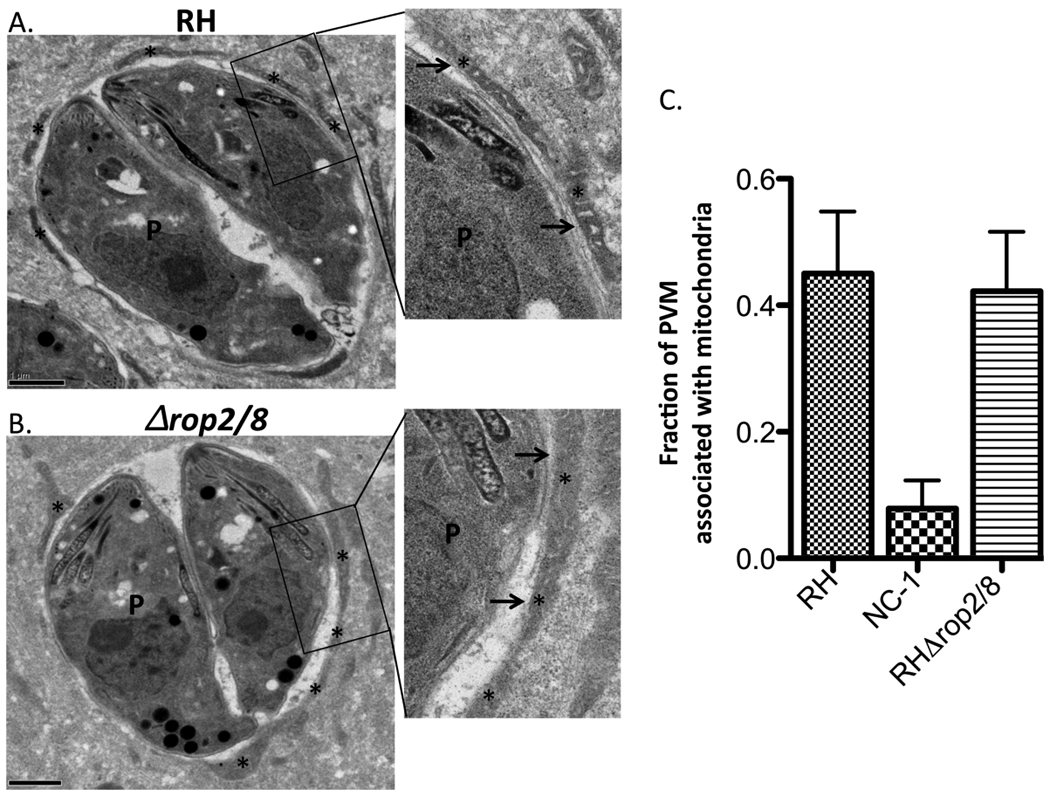

To refine the analysis and to determine whether subtle differences might exist in the nature of the association, electron microscopy was used to examine HFFs independently infected with RH, RHΔrop2/8, and N. caninum (not shown). Monolayers of HFFs grown on glass coverslips were synchronously infected with RH, RHΔrop2/8 and N. caninum parasites and at 6 h p.i. fixed in Karmovsky’s fixative, 2% glutaraldehyde and 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate pH 7.4 for 1 h at RT to reduce the possibility of disrupting the architecture of the association. Following this, the cultures were post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 h at RT, and processed for epon plastic embedding and thin sectioned for transmission electron microscopy using standard protocols. Samples were observed in the JEOL 1230 TEM at 80kV and photos were taken using a Gatan Multiscan 791 digital camera.

The results again showed no qualitative difference between RH and RHΔrop2/8 recruitment of host mitochondria. Additionally, there was no measurable difference in the distance separating the PVM and the host mitochondrial membrane (Fig. 3A, B). For quantification of this association, 50 images were taken of RH, RHΔrop2/8 and N. caninum PVs in infected cells and 30 were randomly selected for further analysis by ImageJ. The ImageJ program was used to measure the fraction of the PVM associated with host mitochondria (PVM associated with mitochondria/total PVM perimeter). As expected, the N. caninum control showed the expected lack of such association with a minor percentage of PVM bound to mitochondria. Consistent with the qualitative analyses, the fraction of PVM associated with mitochondria showed no significant difference between RH and RHΔrop2/8, arguing that the ROP2/8 cluster does not play a role in host mitochondrial association (Fig. 3C). Examination of the electron micrographs also revealed no apparent structural differences in the RHΔrop2/8 parasites; the rhoptries, in particular, showed a similar overall morphology (Fig. 3 and data not shown) which contrasts with what was seen in parasites lacking ROP1 where the rhoptries became thinner and more electron dense (Ossorio et al., 1992).

Fig. 3.

Vacuoles containing Toxoplasma RHΔrop2/8 tachyzoites show no defect in mitochondrial association or rhoptry morphology by electron microscopy. Transmission electron micrographs depicting the parasitophorous vacuole (PV) surrounding (A) RH wild type and (B) RHΔrop2/8 parasites grown in human foreskin fibroblasts. Boxes show enlarged regions of the PV membrane (PVM) and adjacent host and parasite features. Cells were fixed at 6 h p.i.. The PVM is indicated by the arrows and the host mitochondria are indicated by the asterisks. P, parasite. Scale bar, 1 µm. (C) Fraction of PVM associated with mitochondria in Neospora caninum (NC-1), RH wild type and RHΔrop2/8 as determined by ImageJ analysis of electron micrographs (n = 30 for each). Values shown are mean+/− S.D.

The data presented here show that parasites deficient in ROP2 and ROP8 expression retain the ability to recruit host mitochondria in a manner that is indistinguishable from the RH parental strain. These results strongly suggest that ROP2 is not an essential mediator of PVM-mitochondrial association, contrary to previously published data describing an inhibition of PVM-mitochondrial association following targeted depletion of ROP2 by antisense RNAs (Nakaar et al., 2003). One way to reconcile these different results is to consider the fact that ROP2 is the founding member of a family now known to comprise at least 12 similar genes (El Hajj et al., 2006). Thus, it may be that the antisense RNA-mediated depletion of ROP2 had off-target effects on other members of the ROP2 family, thereby producing the observed phenotype. This was not a possibility that could have been anticipated or checked prior to the recent sequencing of the Toxoplasma genome and proteomic analysis of the rhoptries.

Our results do not exclude the possibility that ROP2/8 play a role in mitochondrial recruitment but that there are redundant parasite factors that enable this association even in a ROP2/8 null background. There is no reason to invoke such a role for ROP2/8, however, as the only direct evidence implicating them in the mitochondrial recruitment was from the anti-sense ablation approach, which our results clearly refute. Hence, it would appear that Toxoplasma utilizes other, as yet unidentified factors to recruit host mitochondria to its PVM.

The antisense-ablation experiments also were used to argue that ROP2 is a key protein in proper biogenesis and maintenance of rhoptry structure, thereby affecting the ability of parasites to invade and grow once inside the host cell (Nakaar et al., 2003). Through repeated in vitro passaging, we observed no detectable differences in the growth of RHΔrop2/8 compared to RH wild type parasites and by electron microscopy, there was no apparent difference in rhoptry number or morphology. Hence, we believe that the disrupted rhoptry biogenesis and impairment of cytokinesis of the parasites subjected to the antisense ablation was due to some effect other than a reduction in the amount of ROP2 present. It seems likely that these additional phenotypes were again a result of off-target effects of the antisense RNA, perhaps on other members of the ROP2 family. We know of no evidence that any ROP2 family member is individually essential for in vitro growth but it would not be surprising if they were needed collectively.

Our results re-open two important questions: what is the true role of the ROP2/8 genes and what mediates mitochondrial recruitment to the PVM? The first question will need extensive phenotypic a were no morphological differences apparent. The second will likely require a combination of biochemical and genetic approaches that allow for the possibility that virtually any gene in the parasite could be involved but, based on the antisense data, start with the possibility that previously unstudied members of the ROP2 family serve this function.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the following Stanford colleagues for provision of reagents: Kerry Buchholz and Yi-Ching Ong for provision of the HXGPRT primers, Michael Reese for provision of the ROP2 RAH primers, Gus Zeiner for pTKO, Jon Boyle and Jeroen Saeij for RHgfpluc, John Perrino for help with the electron microscopy and to Carolina Caffaro and members of the Boothroyd laboratory for helpful discussions. We also gratefully acknowledge Jean-Francois Dubremetz (Montpelier, France) for the T34A7 antibody. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, USA (AI21423 and AI73756) and Stanford University, USA (a Stanford Graduate Fellowship to L.P.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Beckers CJ, Wakefield T, Joiner KA. The expression of Toxoplasma proteins in Neospora caninum and the identification of a gene encoding a novel rhoptry protein. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1997;89:209–223. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(97)00120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boothroyd JC, Dubremetz JF. Kiss and spit: the dual roles of Toxoplasma rhoptries. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:79–88. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley PJ, Sibley LD. Rhoptries: an arsenal of secreted virulence factors. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2007;10:582–587. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Melo EJ, de Carvalho TU, de Souza W. Penetration of Toxoplasma gondii into host cells induces changes in the distribution of the mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell Struct Funct. 1992;17:311–317. doi: 10.1247/csf.17.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donald RG, Roos DS. Gene knock-outs and allelic replacements in Toxoplasma gondii: HXGPRT as a selectable marker for hit-and-run mutagenesis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;91:295–305. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(97)00210-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donald RGK, Carter D, Ullman B, Roos DS. Insertional tagging, cloning, and expression of the Toxoplasma gondii hypoxanthine-xanthine-guanine-phosphoribosyltransferase gene. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:14010–14019. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.24.14010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Hajj H, Demey E, Poncet J, Lebrun M, Wu B, Galeotti N, Fourmaux MN, Mercereau- Puijalon O, Vial H, Labesse G, Dubremetz JF. The ROP2 family of Toxoplasma gondii rhoptry proteins: proteomic and genomic characterization and molecular modeling. Proteomics. 2006;6:5773–5784. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Hajj H, Lebrun M, Fourmaux MN, Vial H, Dubremetz JF. Inverted topology of the Toxoplasma gondii ROP5 rhoptry protein provides new insights into the association of the ROP2 protein family with the parasitophorous vacuole membrane. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:54–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo T, Tokuda H, Yagita K, Koyama T. Effects of extracellular potassium on acid release and motility initiation in Toxoplasma gondii. J Protozool. 1987;34:291–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1987.tb03177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herion P, Hernandez-Pando R, Dubremetz JF, Saavedra R. Subcellular localization of the54-kDa antigen of Toxoplasma gondii. J Parasitol. 1993;79:216–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones TC, Hirsch JG. The interaction between Toxoplasma gondii and mammalian cells. II. The absence of lysosomal fusion with phagocytic vacuoles containing living parasites. J Exp Med. 1972;136:1173–1194. doi: 10.1084/jem.136.5.1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labesse G, Gelin M, Bessin Y, Lebrun M, Papoin J, Cerdan R, Arold ST, Dubremetz JF. ROP2 from Toxoplasma gondii: a virulence factor with a protein-kinase fold and no enzymatic activity. Structure. 2009;17:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay DS, Mitschler RR, Toivio-Kinnucan MA, Upton SJ, Dubey JP, Blagburn BL. Association of host cell mitochondria with developing Toxoplasma gondii tissue cysts. Am J Vet Res. 1993;54:1663–1667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaar V, Ngo HM, Aaronson EP, Coppens I, Stedman TT, Joiner KA. Pleiotropic effect due to targeted depletion of secretory rhoptry protein ROP2 in Toxoplasma gondii. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:2311–2320. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossorio PN, Schwartzman JD, Boothroyd JC. A Toxoplasma gondii rhoptry protein associated with host cell penetration has unusual charge asymmetry. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;50:1–15. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90239-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese ML, Boothroyd JC. A helical membrane-binding domain targets the Toxoplasma ROP2 family to the parasitophorous vacuole. Traffic. 2009;10:1458–1470. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00958.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadak A, Taghy Z, Fortier B, Dubremetz JF. Characterization of a family of rhoptry proteins of Toxoplasma gondii. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1988;29:203–211. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(88)90075-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeij JP, Boyle JP, Grigg ME, Arrizabalaga G, Boothroyd JC. Bioluminescence imaging of Toxoplasma gondii infection in living mice reveals dramatic differences between strains. Infect Immun. 2005;73:695–702. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.2.695-702.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinai AP, Joiner KA. The Toxoplasma gondii protein ROP2 mediates host organelle association with the parasitophorous vacuole membrane. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:95–108. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200101073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]