Abstract

The ability to recognize a previously encountered stimulus is dependent on the structures of the medial temporal lobe and is thought to be supported by two processes, recollection and familiarity. A focus of research in recent years concerns the extent to which these two processes depend on the hippocampus and on the other structures of the medial temporal lobe. One view holds that the hippocampus is important for both processes, whereas a different view holds that the hippocampus supports only the recollection process and the perirhinal cortex supports the familiarity process. One approach has been to study patients with hippocampal lesions and to contrast old/new recognition (which can be supported by familiarity) to free recall (which is supported by recollection). Despite some early case studies suggesting otherwise, several group studies have now shown that hippocampal patients exhibit comparable impairments on old/new recognition and free recall. These findings suggest that the hippocampus is important for both recollection and familiarity. Neuroimaging studies and Receiver Operating Characteristic analyses also initially suggested that the hippocampus was specialized for recollection, but these studies involved a strength confound (strong memories have been compared to weak memories). When steps are taken to compare strong recollection-based memories with strong familiarity-based memories, or otherwise control for memory strength, evidence for a familiarity signal (as well as a recollection signal) is evident in the hippocampus. These findings suggest that the functional organization of the medial temporal lobe is probably best understood in terms unrelated to the distinction between recollection and familiarity.

The ability to recognize a stimulus as having been previously encountered depends on the structures of the medial temporal lobe (MTL) [61] and is widely assumed to involve two processes, recollection and familiarity [4, 28, 38]. The familiarity process underlies the almost universal experience of recognizing someone whom you are sure you have met before despite being unable to remember anything about the prior encounter. The recollection process underlies the successful retrieval of the contextual details that accompanied the encounter (such as the fact that you met at a conference in San Francisco last year). The degree to which the various structures of the MTL (hippocampus, dentate gyrus, and subicular complex, together with the entorhinal, perirhinal, and parahippocampal cortices) support these two processes of recognition memory is unresolved, and much recent research has focused particularly on the role played by the hippocampus.

By all accounts, the hippocampus plays an important role in the recollection process, but there is disagreement about whether or not it plays a role in the familiarity process. According to one view, the hippocampus is important for both recollection and familiarity [62]. In addition, the other structures of the MTL are assumed to contribute to both processes as well. By this view, bilateral hippocampal lesions would be expected to impair both recollection-based and familiarity-based recognition decisions. At the same time, even complete hippocampal lesions would be expected to spare some capacity for both processes (because adjacent MTL cortex also supports recognition memory). This view does not question the distinction between recollection and familiarity, nor does it assume that the different structures of the MTL have functionally identical roles. Rather, it holds that any functional differences that exist between MTL structures are not related to the distinction between recollection and familiarity.

According to another view, the hippocampus selectively and exclusively subserves the recollection process, whereas adjacent MTL cortex, the perirhinal cortex in particular, subserves the familiarity process [2, 8, 15]. By this view, complete bilateral hippocampal lesions would be expected to eliminate the capacity for recollection-based memory but have no impact on familiarity-based memory. A less extreme version of this same view holds that the hippocampus plays a larger role for recollection than it does for familiarity [10].

To investigate the neuroanatomical basis of recognition memory in humans, lesion studies, neuroimaging studies, and single-unit recording studies have been used in conjunction with various behavioral methods that are designed to isolate performance based on recollection and familiarity. Three behavioral methods have been used in this regard, and they differ mainly in the degree to which they depend on contested assumptions about the nature of recollection. One approach, which is the least problematic, involves comparing the overall level of performance achieved by memory-impaired patients and controls on tasks that are differentially supported by recollection and familiarity. A second approach, which is somewhat more problematic, compares neural activity associated with individual recollection-based and familiarity-based decisions. A third approach, which is the most problematic, uses a specific dual-process model to directly quantify recollection and familiarity in patients and controls. Recent evidence from each of these lines of investigation is considered below.

Comparing Performance on Recollection-Based vs. Familiarity-Based Tasks

A well established approach to investigating the role of the MTL in recognition memory has been to measure the relative degree of memory impairment exhibited by patients with hippocampal lesions on familiarity-based and recollection-based recognition tests. If the hippocampus subserves both memory processes, then performance on both kinds of test should be impaired to a similar degree, but if the hippocampus selectively subserves recollection, then performance on recollection-based tests should be differentially impaired. Typically, this approach has involved a comparison of performance on an old/new recognition task, which is widely thought to be supported by both recollection and familiarity, vs. performance on free recall, source memory, or associative recognition tasks, which are all thought to depend mainly on recollection (these and other commonly used memory tasks are described in Table 1). Because old/new recognition can be partially supported by familiarity, the question of interest is whether the performance of patients with hippocampal lesions is disproportionately better on an old/new recognition task in comparison to performance on one of the other recollection-based tasks. Such an outcome would not necessarily imply that familiarity is preserved because performance on these tasks can be differentially affected for reasons unrelated to the distinction between recollection and familiarity [e.g.,42]. However, if old/new recognition performance is relatively unimpaired, it would be consistent with the idea that familiarity remains intact in patients with hippocampal lesions.

Table 1.

Behavioral methods commonly used to investigate recollection and familiarity.

| Old/New Recognition | Targets ("old" items that appeared on the list) and foils ("new" items that did not appear on the list) are presented one at a time for either a binary old/new decision or for a confidence rating on a 6-point scale (1 = sure new, 2 = probably new, 3 = maybe new, 4= maybe old, 5 = probably old, 6 = sure old) |

| Forced-Choice Recognition | Each target is presented with one foil (in the 2-alternative version) or with multiple foils (in the multiple-choice version), and the task is to select the target |

| Remember/Know Procedure | A variant of the old/new procedure in which each "old" decision is followed by a subjective judgment indicating whether the decision was based on recollection ("Remember") or familiarity ("Know") |

| Source Recognition | List items are presented with different source attributes which can be external (e.g., presented in a male or female voice) or internal (e.g., imagined as part of an indoor or outdoor scene). An old/new recognition test follows, and the task is to recollect the source attribute for any item declared to be "old" |

| Associative Recognition | Pairs of items are presented for study. On the recognition test, the task is to distinguish intact pairs (which appeared on the list) from rearranged pairs (consisting of items that appeared on the list but as part of different pairs) |

| Free Recall | The task is to recall items from the list in any order |

Several case studies have investigated old/new recognition vs. free recall performance in patients with adult-onset bilateral lesions limited to the hippocampus according to quantitative magnetic resonance imaging. Although some have reported that old/new recognition memory is, indeed, relatively preserved [e.g., 3, 40], others have found that recall and recognition are both impaired [10]. Although case studies can offer suggestive evidence, group studies are more informative because the pattern of results from individual amnesic patients may reflect individual differences in recall vs. recognition that existed prior to the onset of amnesia -- differences that may also exist among unimpaired individuals [e.g., 71]. In the absence of information about premorbid memory performance, the only way to address that possibility is to use a group design.

Group studies of patients with adult-onset hippocampal lesions have consistently shown that the degree of impairment is approximately the same when old/new recognition and free recall are compared [37, 39, 90]. For example, Manns et al. [39] studied six amnesic patients with quantitative radiological evidence of bilateral hippocampal damage and normal parahippocampal gyrus volumes. Figure 1 shows the distribution of recall (percentage correct) and recognition (hit rate minus false alarm rate) scores for the 7 amnesic patients and 8 controls from Manns et al. [39], where each symbol represents the score of an individual subject. It is apparent from the figure that recall and recognition are both impaired in the patients, and the degree of impairment is similar. When the raw scores are converted to z-scores to place them on a common scale, the mean amnesic z-scores for recall and recognition were −1.83 and −1.91, respectively [82]. Both these scores reflect a considerable degree of impairment, and the degree of impairment does not differ depending on whether memory is tested by recall or recognition.

Figure 1.

Individual recall (A) and recognition scores (B) for hippocampal patients (n = 7) and healthy controls (n = 8) from [39] Manns, Hopkins, Reed, Kitchener, and Squire (2003).

Kopelman et al. [37] studied three amnesic patients with damage limited to the hippocampus and two patients with damage that extended into the parahippocampal gyrus. This study also found that free recall and old/new recognition were impaired to a similar degree in both patient subgroups. Yonelinas et al. [90] studied 56 hypoxic patients with damage believed to be limited to the hippocampus (no radiological information was available) and reported that the patients performed better on old/new recognition than on free recall. However, this conclusion was later shown to result from the conspicuously aberrant performance of a single one of the 55 control subjects [82]. With that one aberrant score removed from the analysis, the patients and controls exhibited indistinguishable levels of impairment on recall and recognition (the recognition z-score for the patients was −0.59, whereas the recall z-score was a statistically indistinguishable −0.68). Thus, all the available group studies are consistent in showing that the degree of memory impairment in patients with lesions limited to the hippocampus is similar for old/new recognition (which is substantially supported by familiarity) and for free recall (which is fully dependent on recollection).

Group studies involving other patient populations have sometimes reported that recall is more impaired than recognition. For example, Adlam et al. [1] reported this pattern in patients with developmental amnesia, and Tsivilis et al. [64] reported the same pattern in patients with reduced fornix and mammillary body volume. Nevertheless, group studies of patients with adult-onset hippocampal lesions have not found a differential recall deficit, which suggests that the hippocampus plays an important role in both recollection and familiarity.

Similar conclusions have been reached in group studies that compare performance on an old/new recognition task to performance on a recollection-based task that assesses source memory (Table 1). Specifically, the degree of impairment exhibited by patients with limited hippocampal lesions is similar for old/new recognition and for source memory [24]. This finding is also consistent with the idea that the hippocampus plays an important role for both recollection and familiarity. The data for old/new recognition vs. associative recognition (yet another recollection-based task, see Table 1) are more variable. Some studies suggest that performance on these two tasks is similarly impaired by hippocampal lesions [59], some suggest that associative recognition is differentially impaired [32], and some yield both patterns after manipulating seemingly unimportant procedural details [23]. Although the associative recognition data are variable for reasons that are not yet clear, the weight of evidence using this general approach (i.e., comparing performance on old/new recognition with performance on various recollection-based tasks) suggests that hippocampal lesions affect recollection-based and familiarity-based performance to a similar degree.

A related approach has involved comparing performance on old/new recognition and forced-choice recognition tests when highly similar targets and foils are used [40, 46, see Table 1]. The forced-choice condition in these experiments is often called the forced-choice "corresponding" (FC-C) condition because each target is paired with its similar foil. Thus, for example, a silhouette of a whale that appeared on the study list would be paired with a nearly identical silhouette of a whale that did not appear on the study list. Performance on the FC-C task is thought to be supported by familiarity to a greater extent than old/new recognition because of the correlated familiarity values of paired targets and foils. That is, on the FC-C task, the targets and foils appear together and will generate similar levels of familiarity, but the target item will have a familiarity signal that is slightly, yet reliably, stronger than its similar foil. Because of this small but reliable difference, familiarity can support good performance.

By contrast, in the old/new format, the strong familiarity of the foils will result in a large number of false alarms that can be overcome only by retrieving the memory of the target item (an act of recollection) and noting the small way in which it differs from the foil. If the hippocampus selectively supports recollection, then one would expect patients with hippocampal lesions to exhibit less impairment on the FC-C test than on the old/new test [46]. Two prior studies reported just this result, but one of the studies [27] involved only one hippocampal patient (Y.R.), and the other study [77] involved eight individuals with a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) for whom there were no anatomical data.

In two group studies, Bayley et al. [5] and Jenesen et al. [30] tested five patients with bilateral hippocampal lesions using the FC-C and old/new recognition test formats that were used in the two earlier studies [27, 77]. In addition, Jenesen et al. [30] included a forced-choice noncorresponding (FC-NC) test format in which targets were presented with dissimilar foils that were similar to other targets. As with the old/new format, good performance on the FC-NC format is thought to depend more on recollection than the FC-C format. Thus, if hippocampal damage impaired both old/new recognition and FNC recognition but spared FC-C recognition, it would suggest that the hippocampus selectively supports recollection. However, the patients were impaired on all types of recognition test, and there was no indication in either study that the patients were disproportionately benefited on the familiarity-based FC-C test. The fact that the FCC test conferred no measurable benefit to the patients suggests that the hippocampus supports both recollection and familiarity.

It should be noted that the hippocampal patient Y.R. [27], who exhibited preserved performance on the FCC test and impaired performance on old/new recognition, is also one of the patients who exhibited relatively preserved old/new recognition compared to free recall [40]. Thus, this patient has consistently exhibited greater impairment on tasks that depend more on recollection. Why the performance of this single hippocampal patient differs from that of the group studies [5, 30] is not known. The difference may reflect different subgroups of hippocampal patients (based, for example, on neuropathology) but, as noted earlier, the difference might also simply reflect individual differences that are evident even in the data of unimpaired controls. For example, in Jenesen et al. [30], we found that 2 of 14 unimpaired individuals exhibited distinctly better-than-average performance on FC-C tests but only average performance on old/new recognition. If such individuals sustained bilateral lesions of the hippocampus, they would exhibit the same differential pattern exhibited by patient Y.R. even if the hippocampus supports both recollection and familiarity. If such individual differences exist in both patients and controls, then the question of whether hippocampal damage typically affects recollection selectively should be addressed by a group design. The only group studies to have compared FC-C recognition to old/new recognition suggests that, for the typical hippocampal patient, impairment in the familiarity-based FC-C condition is comparable to that in the old/new (and more recollection-based) condition [5,30].

Neural Activity Associated with Recollection-Based and Familiarity-Based Decisions

In the tasks described above, the objective was to measure the degree of impairment exhibited by patients with hippocampal lesions on tests that vary in how much they depend on recollection and familiarity. A second approach attempts to separate individual recollection-based decisions from individual familiarity-based decisions so that brain activity associated with the two processes can be directly compared (using fMRI or, less frequently, single-unit recording). The two most common methods in this regard are source memory procedures and the Remember/Know procedure (Table 1). Confidence ratings have sometimes been used for this purpose as well. In these studies, as in most of the studies with amnesic patients discussed above, participants are typically presented with a list of items to study and are tested for their ability to remember the items following a short interval (usually on the order of a few minutes).

Source-Memory Procedures

Using a source memory procedure, it is often assumed that items that are correctly declared to be old and followed by a correct source judgment (item-plus-source trials) reflect a recollection-based decision, whereas items that are correctly declared to be old and followed by an incorrect source judgment (item-only trials) reflect a familiarity-based decision. In addition, list items that are mistakenly declared to be new (forgotten trials) are also assumed to reflect familiarity-based decisions, but it is supposed that familiarity was too low for these items to be recognized as old.

If the hippocampus selectively supports recollection, then hippocampal activity should be greater for item-plus-source trials than for item-only trials (a recollection vs. familiarity comparison), whereas activity for item-only trials and for forgotten trials should be similar (a high-familiarity vs. low-familiarity comparison). By contrast, if the perirhinal cortex selectively supports familiarity, then perirhinal activity should be similar for item-plus-source and item-only trials (because they differ in the presence or absence of recollection), but activity should be greater for item-only trials than for forgotten trials (because these trials differ in the degree of familiarity). In studies in which scanning occurred during the study phase, findings like these have been commonly observed [11, 34, 47], though Gold et al. [24] found elevated hippocampal activity for both item-only and item-plus-source trials. Similar results have also been observed when scanning was conducted during retrieval [9, 49, 76].

One problem with these studies is that the comparison between item-plus-source trials and item-only trials is likely confounded with memory strength. Specifically, it is known that confidence in an old/new decision is reliably higher for items that are subsequently associated with correct source judgments than for items that are subsequently associated with incorrect source judgments [24, 57]. Thus, activity associated with strong, recollection-based decisions (item-plus-source) has typically been compared with activity associated with comparatively weak, familiarity-based decisions (item-only). This consideration is critical because activity in both the hippocampus and the perirhinal cortex has been shown to increase with memory strength [55]. In addition, recollection and familiarity are independent of memory strength. That is, one can experience a strong sense of familiarity – and high-confidence that an item is old -- in the absence of recollection [38]. Thus, if the objective is to isolate recollection and familiarity, it is essential to control for memory strength.

Two recent studies have relied on the same source-memory procedure followed in the studies just discussed, except that these studies also took steps to address the strength confound that complicates the interpretation of prior studies. In one study [35], scanning was conducted during the encoding of items, which were presented in context A or context B. Memory was subsequently tested using a 6-point confidence scale for both the old/new question (1 = "Sure Old" to 6 = "Sure New") and the source question (1 = "Sure Source A" to 6 = "Sure Source B"). A first question was whether hippocampal activity would be evident when source recollection was absent but old/new memory was strong (presumably because of strong familiarity). To address this question, Kirwan et al. [35] identified regions of the MTL in which activity varied as a function of item memory strength for decisions in which source memory strength was held constant at chance levels. Specifically, they identified activity that varied as a function of old/new confidence for those trials in which source confidence was at its lowest levels (3 = "Maybe Source A" or 4 = "Maybe Source B") and source accuracy was near chance levels.

This analysis is unique in that it includes old/new decisions made with the highest level of confidence (i.e., a confidence rating of 6, indicating strong memory) despite the absence of source recollection. That is, for these items, subjects indicated that they were certain that the item appeared on the list (an old/new confidence rating of 6) but were uncertain as to whether the item had originally come from Source A or Source B (a source confidence rating of 3 or 4). Using this approach, regions were identified in both hippocampus and perirhinal cortex in which activity varied as a function of subsequent item memory strength while source memory strength was held constant at chance levels (Figure 3). These results may suggest that activity in several structures of the medial temporal lobe (including the hippocampus) is predictive of subsequent memory strength, even when memory strength is based on familiarity. Kirwan et al. [35] also identified regions in both medial prefrontal cortex and right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex/insula in which activity varied as a function of subsequent source memory strength while item memory strength was held constant at its highest level (i.e., 6). This result suggests that it is activity in prefrontal cortex, not the MTL, that is predictive of subsequent recollection and that this activity is independent of item memory strength.

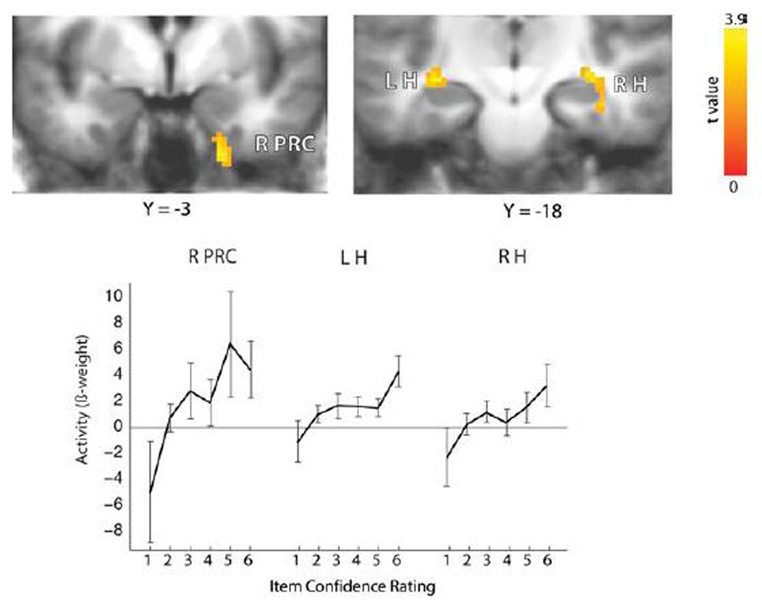

Figure 3.

During learning, activity in right perirhinal (R PRC), right hippocampus (R H), and left hippocampus (L H) varied as a function of the subsequent strength of item memory (confidence rating 1 – 6). Source memory strength was held constant by limiting the analysis to items missed in the old/new test (item confidence 1–3) and (for item confidence 4–6) items in which the source judgment was at chance. Brackets show ± SEM. From [35].

Wais et al. [74] conducted a conceptually similar study that measured activity at retrieval and that attempted to equate the memory strength of item-plus-source and item-only decisions. In this study, the old/new decision for each item was made using a 6-point confidence scale, and each old decision was followed by a binary source judgment ("Source A" or "Source B"). An item-plus-source decision occurred when an item had an old/new confidence rating of 4, 5 or 6 and was followed by a correct source judgment. An item-only decision occurred when an item had an old/new confidence rating of 4, 5 or 6 and was followed by an incorrect source judgment. Most correct source judgments were associated with old/new confidence ratings of 5 or 6, whereas most incorrect source judgments were associated with old/new confidence ratings of 4 or 5. That difference in average old/new confidence for correct and incorrect source decisions is the strength confound that has complicated most source memory studies. To eliminate this confound, Wais et al. identified areas of MTL activity associated with item-plus-source and item-only decisions, but they limited the analysis to items with old/new confidence ratings of 5 or 6 (i.e., old decisions made with relatively high confidence regardless of whether source recollection occurred). The finding was that hippocampal activity associated with both correct source judgments and incorrect source judgments exceeded the activity associated with forgotten items and did so to a similar extent (Figure 4). These results identify both a recollection signal in the hippocampus (elevated activity associated with the item-plus-source condition) and a familiarity signal in the hippocampus (elevated activity associated with the item-only condition). Unlike in the MTL, activation in prefrontal cortex increased differentially in association with source recollection even after equating for strength.

Figure 4.

Activity in left hippocampus identified for separate contrasts of correct source judgments vs. forgotten items and incorrect source judgments vs. forgotten items. To equate for memory strength, the source correct and source incorrect data were based on old decisions made with relatively high confidence (5 or 6 on a 6-point rating scale). Error bars for the two source categories represent the s.e.m. of the difference scores for each comparison, whereas the error bar for the forgotten items represents the root mean square of the s.e.m. values associated with the two individual comparisons (* denotes a significant difference relative to forgotten items, p-corrected< 0.05). From [74].

The studies discussed above used a source memory procedure to separate recollection-based from familiarity-based decisions. Although early fMRI studies using source memory procedures have specifically identified recollection-based activity in the hippocampus, subsequent studies that eliminated the strength confound [35, 74] identified familiarity-based activity in the hippocampus as well. These findings suggest that memory must be strong for activity to be reliably detected in the hippocampus by fMRI, whether memory is based on recollection or on familiarity. Perhaps fMRI is not sensitive to hippocampal activity when memory is weak.

Other measures of neural activity may be more sensitive for detecting hippocampal activity in association with weak, familiarity-based memories. For example, Rutishauser et al. [53, 54] measured activity in the hippocampus and the amygdala for item-plus-source and item-only decisions using depth electrodes in epileptic patients who were being evaluated for surgery. The finding was that some neurons in the hippocampus were sensitive to novelty (they increased their firing to new items), whereas other neurons were sensitive to prior occurrence (they increased their firing to old items). For both classes of neuron, the response to target items was most pronounced on item-plus-source trials and least pronounced on forgotten trials. However, unlike in the fMRI data, these neurons exhibited an intermediate response on item-only trials. These results provide evidence that hippocampal activity is associated with relatively weak, familiarity-based item recognition (activity that appears difficult to detect using fMRI).

Remember/Know Procedure

An advantage of the source memory procedure is that it involves an objective measure of the presence or absence of recollection. A disadvantage is that whenever recollection does not occur (on item-only trials), the argument could be made that those correct old decisions were not based on familiarity but were instead based on the recollection of some detail about the item other than its source (e.g., the recollection of thoughts that occurred when the item was presented). If so, then what appears to be familiarity-based activity might instead reflect activity associated with undetected recollection. An alternative method that can potentially address that issue is the Remember/Know procedure, which is based on subjective reports of whether or not recollection of any kind is available when an item is judged old [20]. The Remember/Know procedure was originally intended to distinguish between episodic and semantic memory [65, 66], but it is now widely used instead to distinguish between recollection and familiarity. Participants report Remember when they can recollect something about the original encounter with the item (e.g., its context, what thoughts they had), and they report Know when they judge the item to be familiar but cannot recollect anything about its presentation. In recent years, this convenient technique has frequently been used in neuroimaging studies in an effort to identify brain structures that underlie recognition memory processes.

A disadvantage of the remember/Know procedure is that no objective measure of recollective success or failure is obtained. In addition, as discussed in detail below, this procedure is also compromised by a strength confound. Still, this approach may offer a useful supplement to the source memory method of separating recollection-based and familiarity-based memories (once the strength confound is eliminated).

In many neuroimaging studies, activity at encoding and activity at retrieval has been found to be elevated in the hippocampus for Remember judgments (e.g., relative to activity associated with forgotten items) but not for Know judgments [e.g., 3, 16, 17, 26, 27, 45, 70, 72, 90]. This result is consistent with the idea that the hippocampus selectively subserves the recollection process. However, as with the source memory procedure discussed earlier, the Remember/Know procedure involves a well-documented strength confound. That is, when confidence judgments are obtained in the context of the Remember/Know procedure, it has been established that Remember judgments are generally associated with old decisions made with high confidence and high accuracy, whereas Know judgments are generally associated with old decisions made with lower confidence and lower accuracy [13, 14, 52, 65, 84]. Thus, the fMRI evidence suggesting that activity in the hippocampus is elevated for Remember judgments but not for Know judgments may reflect the fact that hippocampal activity is more readily detected for strong memories than for weak memories (whether recollection-based or familiarity-based). Indeed, much evidence suggests that Know judgments are actually associated with lesser degrees of recollection, not with the absence of recollection [e.g., 73]. If so, then the frequent failure to detect hippocampal activity for Know judgments means that weak memory, even if it involves recollection, is hard to detect in the hippocampus using fMRI.

Wixted [81] pointed out that the strength confound in the Remember/Know procedure could be eliminated in much the same way that it has been eliminated in source memory tasks [e.g., 74]. Some Know judgments (like most Remember judgments) are made with high confidence and high accuracy. The question is whether elevated hippocampal activity would be evident for these strong and largely familiarity-based memories. Eliminating the Remember/Know strength confound in this manner holds the promise of producing evidence that might be compelling to those who currently fall on different sides of this debate.

Directly Quantifying Recollection and Familiarity

A third approach to investigating the neuroanatomical basis of recognition memory attempts to directly quantify the contribution of recollection and familiarity to the recognition decisions made by patients with hippocampal lesions and controls. This approach is typically based on a specific dual-process model proposed by Yonelinas [87] to estimate the proportion of old decisions that were based on recollection and also to quantify the average familiarity of the list items. One version of this approach computes quantitative estimates of recollection and familiarity from Remember/Know judgments (the widely used "Independence Remember/Know" method), and a related version computes these estimates from the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC). The effort to directly quantify recollection and familiarity in this manner depends on a psychological model that makes strongly disputed assumptions about the nature of recollection. Specifically, the model assumes that recollection is a categorical process that either occurs (with high confidence) or does not occur. If recollection is found to be a continuous process instead, then the estimates of recollection and familiarity derived from Remember/Know judgments or from ROC analysis would not be valid and could not be used to advance our understanding of the neuroanatomical basis of recognition memory.

Recent evidence suggests that recollection is not a categorical process but is instead a continuous process [31, 41, 53, 54, 56, 80]. The problematic assumption about the nature of recollection likely explains why the Yonelinas [87] model has been repeatedly disconfirmed in the experimental psychology literature during the past 10 years [22, 25, 29, 33, 50, 57, 58, 60]. Still, the model remains in widespread use in the cognitive neuroscience literature as a way to quantify recollection and familiarity, and we turn now to a consideration of that work.

Remember/Know Judgments

When the independence Remember/Know method is used, recollection is estimated directly from the Remember hit rate (i.e., the proportion of target items that received a Remember judgment), or it is estimated from an adjusted Remember hit rate (by subtracting from it the Remember false alarm rate). The strength of familiarity is estimated by computing a d' score from adjusted hit and false alarm rates associated with Know judgments. The adjusted hit rate is equal to the Know hit rate divided by 1 minus the Remember hit rate, and the adjusted false alarm rate is equal to the Know false alarm rate divided by 1 minus the Remember false alarm rate. With this method, Remember/Know studies of memory-impaired patients with MTL damage extending beyond the hippocampus have been interpreted as showing that both recollection and familiarity are impaired but that the familiarity impairment is less severe than the recollection impairment [88, 89]. Of particular interest, though, is the effect of hippocampal lesions per se on estimates of recollection and familiarity.

Three group studies have been performed using Remember/Know judgments with patients thought to have lesions limited to the hippocampus. Yonelinas et al. [90] studied 4 hypoxic-ischemic patients and found that estimates of recollection based on the Remember/Know procedure were impaired relative to controls, whereas estimates of familiarity were comparable in the patients and controls. No radiological evidence was available to quantify the extent of the lesions or to establish that they were limited to the hippocampus. Manns et al. [39], by contrast, found that both recollection and familiarity estimates were reduced in 7 patients with bilateral lesions limited primarily to the hippocampal region (quantified by magnetic resonance imaging). More recently, Turriziani et al. [69] reported no difference in recollection or familiarity deficits using this same procedure in 4 patients with bilateral damage limited to the hippocampus. However, they attributed the failure to find a differential deficit to statistical noise, and they interpreted other aspects of their results as supporting the idea that recollection is differentially impaired in these patients.

Why these studies differ in their findings is not altogether clear, but it is important to keep in mind that a) the Remember/Know procedure suffers from a strength confound [13], b) Know judgments are not devoid of recollection [73], and c) the quantitative estimates of recollection and familiarity that are derived from Remember/Know judgments (using the Independence Remember/Know method) depend on the validity of a particular dual-process model that has been repeatedly rejected in recent years [e.g., 22, 25, 29, 51, 57, 58]. In future studies, a better approach might be to use Remember/Know judgments equated for confidence and accuracy (to eliminate the strength confound) and also to avoid the use of any psychological model to estimate recollection and familiarity. For example, one could, assess the frequency with which patients with hippocampal lesions experience high-confidence, familiarity-based recollection (e.g., an experience like "I am certain that I have seen you before, but I just can't place you"). The differing views of MTL function make contrasting predictions of how often this experience should occur in patients with hippocampal lesions relative to controls.

If hippocampal lesions selectively impair recollection, then patients with hippocampal lesions should have the experience of high-confidence, familiarity-based recognition unaccompanied by recollection quite frequently -- more frequently, in fact, than unimpaired controls. In unimpaired individuals, the experience of high-confidence familiarity-based recognition is relatively rare because, usually, when a very familiar item is encountered (e.g., a familiar face), details about the prior encounter are remembered as well. However, if hippocampal lesions impair recollection while leaving familiarity preserved, then hippocampal patients should experience a strong sense of familiarity as often as unimpaired individuals do but without the recollection typically associated with that experience. That is, they should, with unusual frequency, report being certain of having encountered a stimulus before without being able to recollect any associated details. Indeed, Holdstock et al. [27] seem to suggest that patient YR commonly has this experience:

It is therefore plausible to assume that YR's familiarity is unimpaired. This clear impression from the "Remember/ Know" procedure of normal familiarity in YR is consistent with observations of her memory in daily life, which showed that her recall was poor, but that after she had encountered objects and other items (e.g., peoples faces) subsequent encounters produced a clear sense of familiarity (p. 349)

In the only study to experimentally address this issue, Kirwan, Wixted and Squire [36] investigated the experience of high-confidence familiarity-based recognition in five patients with circumscribed hippocampal damage. The question of interest was whether this experience occurred more often in patients than in healthy controls, as should be the case if hippocampal lesions selectively impair recollection. After studying a list of 25 words in one of two contexts (source A or source B), old/new recognition memory for the words was tested using a 6-point confidence scale (1 = sure new, 6 = sure old). For items endorsed as old, participants were asked to make a source recollection decision. Old decisions made with high confidence but in the absence of successful source recollection would correspond to high-confidence, familiarity-based recognition. The results showed no increased tendency for this experience to occur in patients relative to controls. Instead, if anything, it occurred less often in the patients. The simplest explanation for this result is that hippocampal damage impairs familiarity as well as recollection. This issue could also be investigated using the Remember/Know procedure (do hippocampal patients experience high-confidence Know judgments more often than healthy controls?), but the relevant experiment has not yet been performed.

ROC Analysis

Another method that has been used to quantify recollection and familiarity has been to fit the Yonelinas [87] dual-process psychological model to ROC data (this is the same model that is often used to estimate recollection and familiarity with the Remember/Know procedure using the independence method). An ROC is a plot of the hit rate versus the false alarm rate across different decision criteria. Typically, multiple pairs of hit and false alarm rates are obtained by asking subjects to provide confidence ratings for their old/new recognition decisions. A pair of hit and false alarm rates is then computed for each level of confidence, and the paired values are plotted across the confidence levels. The points of an ROC typically trace out a curvilinear path, one that may be symmetrical about the negative diagonal (Figure 5A) but is more typically asymmetrical about the negative diagonal (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Hypothetical ROC Data Illustrating Symmetrical (A) and Asymmetrical (B) ROC Plots. The axis of symmetry is the negative diagonal (dashed line), and chance performance is indicated by the positive diagonal (solid line). The degree of symmetry is typically quantified by the "slope" parameter (s). The value of the slope parameter is equal to 1 if the data trace out a symmetrical path and differs from 1 if the data trace out an asymmetrical path. The dual process/detection model would yield a recollection parameter estimate of 0 for the symmetrical ROC (A) and an estimate greater than 0 for the asymmetrical ROC below (B).

The dual-process model proposed by Yonelinas [87, 89] holds that the degree of asymmetry in an ROC directly reflects the degree to which the recollection process is involved in recognition decisions. Accordingly, a symmetrical ROC indicates that recognition decisions were based solely on familiarity, and an asymmetrical ROC indicates that recollection occurred for some of the items as well. Other data suggest that memory-impaired patients [89, 90] or rats with hippocampal lesions [18] produce symmetrically curvilinear ROCs (as in Figure 2A), whereas controls produce asymmetrical curvilinear ROCs (as in Figure 2B). This finding has been interpreted to mean that the recollection process is selectively impaired by hippocampal lesions.

Figure 2.

Discriminability performance (d') by patients with limited hippocampal lesions (H) and controls (CON) on yes/no recognition (Y/N) and forced-choice recognition (FCC). The data represent performance on the first 24 trials of the yes/no object recognition test and on all 12 trials of the forced-choice object recognition test. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. From [5].

Although patient and control ROC curves differ with respect to symmetry, they also differ in that memory-impaired patients have weaker memories than controls. In ROC data, this lower level of memory performance is manifest as an ROC curve that falls closer to the positive diagonal. This is an important consideration because in studies using unimpaired controls, the ROC typically becomes more symmetrically curvilinear as memory strength weakens [75, see 22 for a review]. If symmetry of the ROC is related to memory strength, then the observed difference in symmetry between impaired and unimpaired subjects may simply reflect the difference between weak and strong memories (not qualitative differences in the integrity of underlying recognition memory processes). Thus, a question of interest is whether a difference in symmetry would still be evident even after overall memory performance was equated.

To investigate this issue, Wais et al. [75] analyzed the ROC produced by a group of patients with lesions limited to the hippocampus under two conditions. In one condition, patients studied 50-item words lists, as did matched controls. As expected, the controls achieved a higher level of memory performance than the patients. In addition (again as expected), the control ROC was asymmetrical (Figure 6C), and the patient ROC was symmetrical (Figure 6A). This outcome replicated prior work and might be taken to mean that recollection is selectively impaired in the patients, but this same outcome could also simply reflect the weaker memory performance of the patients. To equate for overall memory strength, a list-length manipulation was used, capitalizing on the fact that shorter lists generally lead to better memory performance. Accordingly, in addition to the 50-item lists, the patients also studied (and were tested on) lists of 10 items, which increased their memory performance to a level similar to that of the controls who had studied a 50-item list. If the patients achieved that higher level of performance primarily on the basis of familiarity (as should be the case if recollection is selectively impaired), and if the degree of asymmetry in an ROC reflects recollection, then the patient ROC for the 10-item condition should still be relatively symmetrical (theoretically reflecting familiarity-responding, even when memory is strong). However, the result was that the patient ROC for the 10-item condition was as asymmetrical as that of the controls (Figure 6B). Thus, the difference in ROC symmetry for the patients and controls in the 50-item condition does not reflect a selective deficit in recollection but instead reflects a difference in overall memory strength.

Figure 6.

ROC data produced by hippocampal patients in a recognition test following a 50-item word list (H-50) or a 10-item word list (H-10) and by controls following a 50-item word list (C-50). The slope of 1.14 for the H-50 ROC (A) was not different from 1.0 (p < 0.10), indicating that the ROC was symmetric. The slope of 0.83 for the H-10 ROC (B) and the slope of 0.83 for the C-50 ROC (C) were both less than the slope of 1.14 for the H-50 ROC (χ2[1] ≥ 4.70, p < 0.05) and were significantly less than 1.0 by a one-tailed test (χ2[1] ≥ 2.70, p ≤ 0.05). This result suggests that, once equated for strength, the component processes of recognition memory are comparable in patients and controls. From [75].

The findings reported by Wais et al. [75] conflict with the findings of a conceptually similar study by Fortin et al. [18], who tested odor recognition memory in rats and analyzed the shape of the ROC under different memory strength conditions. The ROCs in their experiment were produced by a biasing manipulation that consisted of varying both the reward magnitude for correct decisions and the effort needed to acquire the reward. Following a 30-minute retention interval, control rats produced an asymmetrical, curvilinear ROC, and rats with hippocampal lesions exhibited weaker memory and produced a symmetrical curvilinear ROC. Quantitative estimates of recollection and familiarity obtained from fitting the Yonelinas [87] dual-process model to these ROC data suggested that recollection was impaired in the hippocampal rats and that familiarity was preserved. The results described up to this point are similar to what has been observed in humans, and the authors recognized that the difference might also simply reflect a difference in memory strength.

To evaluate the importance of memory strength, the authors included a second condition where memory strength was matched. This was accomplished by testing control rats after a 75-min retention interval, which yielded a level of recognition memory performance similar to that of the hippocampal rats tested after a 30-minute retention interval. When this method of weakening memory is used in humans, the confidence-based ROC invariably becomes more symmetrically curvilinear [12, 19, 21, 67, 68, 75]. Thus, one might expect to find that the control ROC following the long retention interval in the odor recognition experiment would become symmetrically curvilinear as well (much like that of the hippocampal rats following a short retention interval). Instead, Fortin et al. [18] found that the ROC associated with the long retention-interval condition was not symmetrically curvilinear but was instead nearly linear. The dual-process model proposed by Yonelinas [87] interprets a linear ROC to reflect purely recollection-based responding. Accordingly, Fortin et al. [18] interpreted their findings for controls to mean that weak memory in the long-delay condition was based purely on recollection, presumably because familiarity faded rapidly as the retention interval increased. Because similarly weak memory in the hippocampal rats was associated with a symmetrical, curvilinear ROC (the signature of pure familiarity-based responding according to the Yonelinas dual-process model), Fortin et al. [18] concluded that the hippocampus selectively subserves the recollection process.

For several reasons, the meaning of this linear ROC is not clear. First, the linearizing effect of an increased retention interval on the shape of the ROC has never been reported previously in any study, even though the issue has been repeatedly investigated in humans and, occasionally, in experimental animals [79]. It is not clear why this result should occur uniquely for rats on an odor recognition task. Second, the model used to interpret the linear ROC as being indicative of recollection-based responding was developed to account for confidence-based ROCs in humans. In recent years, a large body of evidence has accumulated suggesting that the model is not valid [e.g., 25, 50, 57, 58, 60]. Indeed, Bird, Varghs-Khadem and Neil [6] recently showed that the ROC data produced by patient Jon (a developmental amnesic) implausibly suggested normal recollection and impaired familiarity, the opposite of what is suggested by Jon's impaired performance on tests of recall and much better performance on recognition tests. Third, recent evidence suggests that ROCs for human recognition memory produced by a biasing manipulation may sometimes be linear even on an ordinary old/new recognition task [7], which most would agree involves a considerable degree of familiarity-based responding. Thus, the meaning of a linear ROC produced by a biasing manipulation is not clear and should probably not be taken to reflect purely recollection-based responding [83]. In any case, the results reported by Wais et al. [75] suggest that, in humans, the shape of the ROC is not affected by hippocampal lesions once overall memory strength is equated.

Discussion

A considerable body of evidence has seemed to support the idea that the hippocampus plays a selective role in recollection while having no role in familiarity. For example, several case studies of patients with hippocampal lesions suggested that performance on old/new recognition was less impaired than performance on free recall [3, 40]; neuroimaging studies of source memory and Remember/Know judgments in unimpaired individuals suggested that hippocampal activity was elevated for decisions based on recollection but not for decisions based on familiarity [e.g., 3, 11, 16, 17, 47]; and theory-based quantitative analyses of ROC data and Remember/Know judgments produced by memory-impaired patients suggested that recollection was selectively impaired by hippocampal lesions [e.g., 90]. All of these findings provided converging evidence that the psychological distinction between recollection and familiarity maps directly on to the distinct functions of the hippocampus and perirhinal cortex.

In light of more recent evidence, the sharp anatomical distinction between recollection and familiarity in the MTL has become much harder to sustain. First, group studies involving patients with hippocampal lesions have consistently shown that old/new recognition and free recall are similarly impaired [37, 39, 90; see 82]. Because it is widely agreed that old/new recognition can largely be supported by familiarity, whereas free recall is supported only by recollection, and because group studies offer more compelling evidence than case studies, the current evidence using this approach cannot easily be reconciled with the proposal that the hippocampus selectively subserves the recollection process.

Second, neuroimaging studies that had seemed to find that recollection-based activity is consistently detectable in the hippocampus, whereas familiarity-based activity often is not, have involved a strength confound. That is, the recollection condition in these studies -- such as Remember judgments or item-plus-source decisions -- likely involved stronger memories (i.e., old decisions associated with higher confidence) than the familiarity condition. As such, the results are equally consistent with the notion that activity associated with strong memories is more detectable in the hippocampus than activity associated with weak memories. Because familiarity-based memories can be strong, this alternative proposal merits serious consideration. Two studies that attempted to address this strength confound both reported that strong, familiarity-based memory is associated with increased hippocampal activity [35, 74]. This result again suggests that the hippocampus subserves familiarity as well as recollection, though more work is needed to definitively resolve this issue. Indeed, it could be argued that in the conditions thought to involve strong familiarity, undetected recollection occurred (thereby accounting for hippocampal activity that appeared to be based on familiarity). The Remember/Know procedure, which relies on subjective reports of the presence or absence of recollection, may be able to resolve this issue. Although the standard version of the Remember/Know procedure also involves a strength confound, the confound could be addressed by testing for evidence of hippocampal activity after Remember and Know judgments are equated for confidence and accuracy. If the hippocampus subserves familiarity, then hippocampal activity should be associated with high-confidence Know judgments (just as hippocampal activity is typically associated with high-confidence Remember judgments).

Finally, attempts to quantify recollection and familiarity using Remember/Know judgments and ROC analysis have yielded a mixed picture. This circumstance may be partly due to the fact that the approach is fully dependent on the validity of the quantitative psychological model that is typically used to interpret the results, i.e., the dual-process, threshold-recollection model proposed by Yonelinas [87], and this model has been heavily questioned in recent years. As such, the estimates of recollection and familiarity generated by these methods are unlikely to be valid [e.g., 13, 14, 51]. Still, even if the estimates themselves are not valid, one can ask whether memory-impaired patients and unimpaired controls yield qualitatively different patterns of data (for whatever reason), beyond what could be expected from a difference in memory strength alone. For example, regardless of whether or not valid estimates of recollection and familiarity cannot be obtained from ROC data, one can ask whether the ROC data produced by hippocampal patients and controls differ once memory strength is equated. If a difference does exist even after equating strength, then an explanation for that difference would need to be found.

In humans, the finding to date is that differences in the pattern of ROC data produced by patients and controls disappear once memory strength is equated [75]. In rats, a different story has been reported. Fortin et al. [18] equated strength in hippocampal rats and control rats by using different retention intervals (30-min vs. 70-min, respectively). The ROC produced by control rats following the long retention interval was linear and did not correspond to the symmetrically curvilinear ROC produced by the hippocampal rats. A linear ROC following a long retention interval has never been observed in humans despite a long tradition of ROC research. Instead, in humans, a long retention interval invariably yields a symmetrically curvilinear ROC (the pattern often produced by patients and rats with hippocampal lesions). The findings reported by Fortin et al. [18] could mean that the function of the rat hippocampus differs fundamentally from that of the human hippocampus, but further investigation is needed before drawing that unlikely conclusion [83].

All of these considerations cast doubt on the idea that the functional organization of the MTL precisely coincides with the distinction between recollection and familiarity. It is worth asking whether an alternative view might better characterize the functional differences between the hippocampus and the adjacent structures that lie along the parahippocampal gyrus. Although a simple dichotomous functional distinction seems unlikely to apply, interesting clues about functional differences between the structures of the MTL have emerged from single-unit recording studies. For example, on some tasks, neurons in perirhinal cortex and the hippocampus differ in their response to novel stimuli and familiar stimuli. On these tasks, neurons in the perirhinal cortex tend to signal novelty by an increased their firing rate and then returning to baseline as an item is presented repeatedly and becomes more familiar. Hippocampal neurons have been reported to exhibit no such effect [48, 85]. This outcome was initially taken as evidence that the perirhinal cortex subserves familiarity, whereas the hippocampus plays no role in that process, but it now appears that hippocampal neurons can exhibit the same effect when more complex stimuli are used. For example, Wirth et al. [78] and Yanike et al. [86] recorded neural activity in the hippocampus and perirhinal cortex, respectively, of rhesus monkeys while they were repeatedly exposed to an initially novel scene (with no response required). Unlike earlier studies, they found that a similar proportion of neurons in the perirhinal cortex and the hippocampus initially exhibited elevated firing that subsequently decreased to baseline as the scene became more familiar (which occurred over the course of approximately 15 presentations). Yanike et al. [86] summarize these results in the following way: "Thus, we find that both perirhinal and hippocampal neurons represent information about the relative familiarity of the novel scene stimuli used in this task" (p. 1073). This result is consistent with what is a now a substantial body of work in amnesic patients suggesting that the hippocampus plays a role in the familiarity process [62].

Yanike et al. [86] attribute the failure of earlier studies to find such a familiarity effect in the hippocampus to the fact that most of those studies used stimuli consisting of simple geometric shapes. In contrast, Wirth et al. [78] used complex scenes. These findings suggest that task-specific details may determine whether the hippocampus and perirhinal cortex are differentially engaged in familiarity, and they would appear to weigh against the simple notion that one structure plays a role in familiarity and that the other plays no role whatsoever. Why different stimuli engage these two structures in different ways in not yet clear, and further work is needed to clarify this issue.

In addition to recording neural firing in response to repeated presentations of the same stimulus, Wirth et al. [78] and Yanike et al. [86] also recorded neural activity as monkeys learned location-scene associations. After viewing a complex scene, the monkeys were required to fixate on one of four screen locations to receive a reward, and their ability to remember the correct location increased with training. This associative learning task cannot be solved on the basis of familiarity alone and instead requires cross-modal (i.e., stimulus-motor or stimulus-location) associative learning, a capacity often thought to be specific to the hippocampus. We construe this task as an associative cued-recall task (perhaps more akin to semantic memory in humans than episodic memory), and, as discussed earlier, recall is generally thought to be supported by the recollection process. That is, in response to a learned scene, the monkey presumably recollects the correct screen location and makes an eye movement to the appropriate quadrant. Wirth et al. [78] found that hippocampal neurons signal newly learned associations by changing their firing rate in a way that correlated with the animal’s behavioral learning curve. This result is to be expected based on a large body of evidence suggesting that the hippocampus is involved in the recollection process. However, Yanike et al. [86] reported a similar result for perirhinal neurons, which suggests that the perirhinal cortex also plays a role in recollection.

In both the hippocampus and perirhinal cortex, some cells signaled learning by a significant change in their level of activity relative to baseline, whereas other cells did so by returning to baseline levels of activity as learning progressed. Although the perirhinal and hippocampal neurons were broadly similar in that respect, perirhinal neurons were more likely to code these newly learned associations by returning to baseline firing rate, whereas hippocampal neurons were more likely to code the associations by maintaining a firing rate that differed from baseline. These differences suggest that the two structures are not functionally identical, but it is too soon to know what these findings suggest about the functional differences that may exist.

Still another difference between the hippocampus and the perirhinal cortex lies in the degree to which the two structures code information in stimulus-specific or more abstract forms. Whereas perirhinal neurons often respond in a stimulus-selective manner [43, 44], the neurons of the hippocampus are less stimulus-selective and are more likely to signal prior occurrence, regardless of which stimulus is presented [e.g., 63]. Again, such findings suggest that the structures of the MTL do not play functionally identical roles, but the apparent differences between them do not seem to be related to the distinction between recollection and familiarity. An overemphasis on the distinction between recollection and familiarity may have drawn attention away from what may prove to be more productive lines of inquiry into the functional organization of the MTL. The last decade has witnessed a robust debate organized around the distinction between recollection and familiarity. One hopes that the next decade will witness a similarly robust inquiry organized around the subtle but intriguing differences in the firing properties of neurons in the hippocampus and the adjacent structures of the MTL.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Medical Research Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Institute of Mental Health Grants 24600 and 082892, and the Metropolitan Life Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing Interests Statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Adlam AR, Malloy M, Mishkin M, Vargha-Khadem F. Dissociation between recognition and recall in developmental amnesia. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47:2007–2210. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aggleton JP, Brown MW. Interleaving brain systems for episodic and recognition memory. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2006;10:455–463. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aggleton JP, Vann SD, Denby C, Dix S, Mayes AR, Roberts N, Yonelinas AP. Sparing of the familiarity component of recognition memory in a patient with hippocampal pathology. Neuropsychologia. 2005;43:1810–1823. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atkinson RC, Juola JF. Search and decision processes in recognition memory. In: Krantz DH, Atkinson RC, Suppes P, editors. Contemporary Developments in Mathematical Psychology. San Francisco: Freeman; 1974. pp. 243–290. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bayley PJ, Wixted JT, Hopkins RO, Squire LR. Yes/no recognition, forced-choice recognition, and the human hippocampus. J Cogn Neurosci. 2008;20:505–512. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bird CM, Vargha-Khadema F, Burgess N. Impaired memory for scenes but not faces in developmental hippocampal amnesia: A case study. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:1050–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bröder A, Schütz J. Recognition ROCs Are Curvilinear - or Are They? On Premature Arguments against the Two-High-Threshold Model of Recognition. J. Exp. Psych.: Learn., Mem. & Cogn. 2009;35:587–606. doi: 10.1037/a0015279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown MW, Aggleton JP. Recognition memory: what are the roles of the perirhinal cortex and hippocampus? Nature Rev. Neurosci. 2001;2:51–61. doi: 10.1038/35049064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cansino S, Maquet P, Dolan RJ, Rugg MD. Brain activity underlying encoding and retrieval of source memory. Cereb. Cortex. 2002;12:1048–1056. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.10.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cipolotti L, Bird C, Good T, Macmanus D, Rudge P, Shallice T. Recollection and familiarity in dense hippocampal amnesia: a case study. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44:489–506. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davachi L, Mitchell JP, Wagner AD. Multiple routes to memory: distinct medial temporal lobe processes build item and source memories. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:2157–2162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337195100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donaldson W, Murdock BB., Jr Criterion change in continuous recognition memory. J. Exp. Psychol. 1968;76:325–330. doi: 10.1037/h0025510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunn JC. Remember-Know: A matter of confidence. Psychol. Rev. 2004;111:524–542. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.2.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunn JC. The dimensionality of the Remember-Know task: A state-trace analysis. Psychol. Rev. 2008;115:426–446. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.2.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eichenbaum H, Yonelinas AR, Ranganath C. The medial temporal lobe and recognition memory. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;30:123–152. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eldridge LL, Engel SA, Zeineh MM, Bookheimer SY, Knowlton BJ. A dissociation of encoding and retrieval processes in the human hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:3280–3286. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3420-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eldridge LL, Knowlton BJ, Furmanski CS, Bookheimer SY, Engel SA. Remembering episodes: a selective role for the hippocampus during retrieval. Nature Neurosci. 2000;3:1149–1152. doi: 10.1038/80671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fortin NJ, Wright SP, Eichenbaum H. Recollection-like memory retrieval in rats is dependent on the hippocampus. Nature. 2004;431:188–191. doi: 10.1038/nature02853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Francis MA, Irwin RJ. Stability of memory for colour in context. Memory. 1998;6:609–621. doi: 10.1080/741943373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gardiner JM, Richardson-Klavehn A, Ramponi C. On reporting recollective experiences and "direct access to memory systems". Psychol. Sci. 1997;8:391–394. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gehring RE, Toglia MP, Kimble GA. Recognition memory for words and pictures at short and long retention intervals. Mem. Cogn. 1976;4:256–260. doi: 10.3758/BF03213172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glanzer M, Kim K, Hilford A, Adams JK. Slope of the receiver-operating characteristic in recognition memory. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 1999;25:500–513. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gold JJ, Hopkins RO, Squire LR. Single-item memory, associative memory, and the human hippocampus. Learning & Memory. 2006;13:644–649. doi: 10.1101/lm.258406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gold JJ, Smith CN, Bayley PJ, Shrager Y, Brewer JB, Stark CEL, Hopkins RO, Squire LR. Item memory, source memory, and the medial temporal lobe: Concordant findings from fMRI and memory-impaired patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:9351–9356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602716103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heathcote A. Item recognition memory and the ROC. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2003;29:1210–1230. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.29.6.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holdstock JS, Mayes AR, Gong Q, Roberts N, Kapur N. Item recognition is less impaired than recall and associative recognition in a patient with selective hippocampal damage. Hippocampus. 2005;15:203–215. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holdstock JS, Mayes AR, Isaac CL, Cezayirli E, Roberts N, O'Reilly R, Norman K. Under what conditions is recognition spared relative to recall after selective hippocampal damage in humans? Hippocampus. 2002;12:341–351. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacoby LL. A process dissociation framework: Separating automatic from intentional uses of memory. J. Mem. Lang. 1991;30:513–541. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jang Y, Wixted JT, Huber DE. Testing Signal-Detection Models of Yes/No and Two-Alternative Forced-Choice Recognition Memory. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2009;138:291–306. doi: 10.1037/a0015525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeneson A, Kirwan CB, Hopkins RO, Wixted JT, Squire LR. Recognition memory and the hippocampus: A test of the hippocampal contribution to recollection and familiarity. Learn. & Mem. 2010;17:63–70. doi: 10.1101/lm.1546110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson JD, McDuff SGR, Rugg MD, Norman KA. Recollection, familiarity, and cortical reinstatement: A multivoxel pattern analysis. Neuron. 2009;63:697–708. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kan IP, Giovanello KS, Schnyer DM, Makris N, Verfaellie M. Role of the medial temporal lobes in relational memory: Neuropsychological evidence from a cued recognition paradigm. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:2589–2597. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelley R, Wixted JT. On the nature of associative information in recognition memory. J. Exp. Psych. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2001;27:701–722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kensinger EA, Schacter DL. Amygdala activity is associated with the successful encoding of item, but not source, information for positive and negative stimuli. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:2564–2570. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5241-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kirwan CB, Wixted JT, Squire LR. Activity in the medial temporal lobe predicts memory strength, whereas activity in the prefrontal cortex predicts recollection. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28:10541–10548. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3456-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirwan CB, Wixted JT, Squire LR. A demonstration that the hippocampus supports both recollection and familiarity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:344–348. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912543107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kopelman MD, Bright P, Buckman J, Fradera A, Yoshimasu H, Jacobson C, Colchester ACF. Recall and recognition memory in amnesia: patients with hippocampal, medial temporal, temporal lobe or frontal pathology. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:1232–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mandler G. Recognizing: the Judgment of Previous Occurrence. Psychol. Rev. 1980;87:252–271. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manns JR, Hopkins RO, Reed JM, Kitchener EG, Squire LR. Recognition memory and the human hippocampus. Neuron. 2003;37:171–180. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01147-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mayes AR, Holdstock JS, Isaac CL, Hunkin NM, Roberts N. Relative sparing of item recognition memory in a patient with adult-onset damage limited to the hippocampus. Hippocampus. 2002;12:325–340. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mickes L, Wais PE, Wixted JT. Recollection is a continuous process: implications for dual-process theories of recognition memory. Psychol Sci. 2009;20:509–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mickes L, Wixted JT, Shapiro A, Scarff JM. The effects of pregnancy on memory: Recall is worse but recognition is not. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsych. 2009;31:754–761. doi: 10.1080/13803390802488111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller EK, Li L, Desimone R. A neural mechanism for working and recognition memory in inferior temporal cortex. Science. 1991;254:1377–1379. doi: 10.1126/science.1962197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller EK, Li L, Desimone R. Activity of neurons in anterior inferior temporal cortex during a short-term memory task. J. Neurosci. 1993;13:1460–1478. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-04-01460.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moscovitch D, McAndrews MP. Material-specific deficits in remembering in patients with unilateral temporal lobe epilepsy and excisions. Neuropsychologia. 2002;40:1335–1342. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(01)00213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O'Reilly RC, Rudy JW. Computational principles of learning in the neocortex and hippocampus. Hippocampus. 2000;10:389–397. doi: 10.1002/1098-1063(2000)10:4<389::AID-HIPO5>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ranganath C, Yonelinas AP, Cohen MX, Dy CJ, Tom SM, D'Esposito M. Dissociable correlates of recollection and familiarity within the medial temporal lobes. Neuropsychologia. 2004;42:2–13. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Riches IP, Wilson FA, Brown MW. The effects of visual stimulation and memory on neurons of the hippocampal formation and the neighboring parahippocampal gyrus and inferior temporal cortex of the primate. J. Neurosci. 1991;11:1763–1779. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-06-01763.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ross RS, Slotnick SD. The hippocampus is preferentially associated with retrieval of spatial context. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2008;20:432–446. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rotello CM, Macmillan NA, Hicks JL, Hautus M. Interpreting the effects of response bias on remember-know judgments using signal-detection and threshold models. Mem. Cogn. 2006;34:1598–1614. doi: 10.3758/bf03195923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rotello CM, Macmillan NA, Reeder JA, Wong M. The remember response: Subject to bias, graded, and not a process-pure indicator of recollection. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2005;12:865–873. doi: 10.3758/bf03196778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rotello CM, Zeng M. Analysis of RT distributions in the remember-know paradigm. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2008;15:825–832. doi: 10.3758/pbr.15.4.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rutishauser U, Mamelak AN, Schuman EN. Single-trial learning of novel stimuli by individual neurons of the human hippocampus-amygdala complex. Neuron. 2006;49:805–813. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rutishauser U, Schuman EM, Mamelak AN. Activity of human hippocampal and amygdala neurons during retrieval of declarative memories. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:329–334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706015105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shrager Y, Kirwan CB, Squire LR. Activity in both hippocampus and perirhinal cortex predicts the memory strength of subsequently remembered information. Neuron. 2008;59:547–553. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Slotnick SD. Remember source memory ROCs indicate recollection is a continuous process. Memory. doi: 10.1080/09658210903390061. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Slotnick SD, Dodson CS. Support for a continuous (single-process) model of recognition memory and source memory. Mem. Cogn. 2005;33:151–170. doi: 10.3758/bf03195305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smith DG, Duncan MJJ. Testing theories of recognition memory by predicting performance across paradigms. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2004;30:615–625. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.30.3.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stark CEL, Bayley PJ, Squire LR. Recognition memory for single items and for associations is similarly impaired following damage limited to the hippocampal region. Learn. Mem. 2002;9:238–242. doi: 10.1101/lm.51802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Starns JJ, Ratcliff R. Two dimensions are not better than one: STREAK and the univariate signal detection model of remember/know performance. J. Mem. Lang. 2008;59:169–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]