Abstract

The IGF pathway plays a major role in cancer cell proliferation, survival and resistance to antineoplastic therapies in many human malignancies. As such, interference with this pathway is the target of many investigational pharmacologic agents. Cixutumumab, a monoclonal antibody to IGF-1R, utilizes this concept. In this review, we summarize preclinical, pharmacologic and early clinical data regarding this agent and discuss the impact this drug might have on the future treatment of human cancers.

Keywords: cixutumumab, IGF-1R, IMC-A12, monoclonal antibody

1. Introduction

The IGF pathway plays a major role in cancer cell proliferation, survival and resistance to antineoplastic therapies in many human malignancies. As such, interference with this pathway is the target of many investigational pharmacologic agents. Receptor blockade using a therapeutic monoclonal antibody represents one potential strategy. Currently, there are several anti-IGF-1R monoclonal antibodies that have been developed to block IGF-mediated proliferation. One such agent is cixutumumab (CIX), or IMC-A12. CIX is a fully human IgG1/λ monoclonal antibody directed at the type I IGF receptor (IGF-1R). CIX binds IGF-1R with high affinity and blocks interaction between IGF-1R and its ligands, IGF-1 and -II, and induces internalization and degradation of IGF-1R. CIX has demonstrated tumor growth inhibition in both in vitro and in vivo studies. Enhancement in efficacy of anticancer activity has also been shown when CIX is combined with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, inhibitors of EGFR or HER2, and other molecularly targeted agents [1]. In this review, we summarize pharmacologic and clinical data regarding this agent and discuss the impact this agent might have on current and future treatment regimens.

2. IGF and cancer

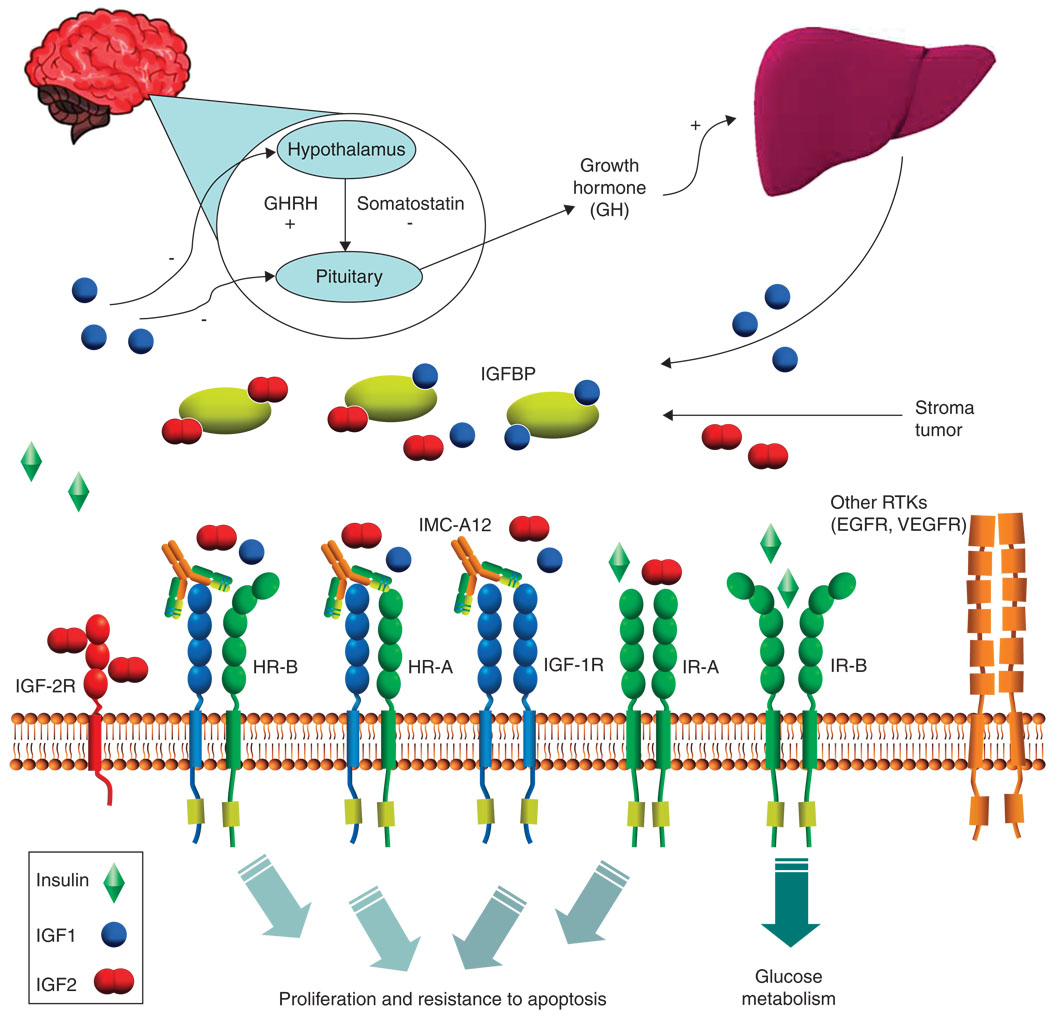

IGF-I and -II are potent mitogens for a broad range of cancers in vitro and their growth stimulating effects are mediated through various receptors. The IGF signaling systems is comprised of the circulating IGF ligands IGF-I and -II, IGF-1R, insulin receptor isoform A (IR-A), insulin receptor isoform B (IR-B), IGF-2R and IGF binding proteins (IGFBP) 1 through 6. The IGF-1R has been the main target of therapy directed against the IGF signaling system, as it is a major transducer of IGF signaling leading to proliferative and antiapoptotic effects. IR-A, however, also contributes to IGF signaling, mainly through the binding of IGF-II [2–6]. The contributory role IR isoforms play versus the IGF-1R and their hybrid receptors in human cancer is unknown and is an active area of research.

IGF-1R is expressed on the cell surface as a heterotetramer composed of two extracellular α chains and two membrane-spanning β chains in a disulfide-linked β-α-α-β. On binding to ligand, IGF-1R undergoes conformational changes and autophosphorylation. Ultimately, through subsequent phosphorylation of intracellular substrates, the MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways are activated. Activation of these pathways has been shown to lead to cell proliferation and resistance to apoptosis [3–5]. Although the MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways seem dominant in most cancer models of IGF signaling, other pathways such as p38, JNK and PKC may also be important in various model systems [7–9].

IGF-1R belongs to the IR family that includes the IR, IGF-1R (homodimer), IGF-1R/IR (hybrid receptor) and IGF-2R. IGF-1R/IR hybrids have biological activity similar to IGF-1R homoreceptors, preferentially binding and signaling with IGF ligands, rather than with insulin. The IR exists in two forms: IR-B, which is the ‘classic’ IR by which insulin exerts its metabolic effects, and IR-A, which is a fetal form that re-expressed in some tumors and binds IGF-II at physiologic concentrations. Activation of IR-A by IGF-II can lead to cell proliferation and resistance to apoptosis in a similar manner to IGF-I and -II mediated activation of IGF-1R. IGF-2R is a non-functioning receptor that acts to bind and limit the bioavailability of IGF-II [10,2,11,3–5].

While IGF-I and -II are abundant in the serum of adults, there are several proteins that limit their bioavailability, and thus ability to activate IGF-1R. Six well-characterized IGFBP bind circulating IGF-I and -II to limit their bioavailability. As a result, only ~ 2% of IGF ligands exist in the ‘free’ state. Additionally, local bioavailability of IGF-I and -II for IGF-1R signaling is also subject to regulation by IGFBP protease and presence of the non-signaling, IGF-II binding IGF-2R [3–5].

Evidence for involvement of the IGF signaling system in cancer development and progression comes from many different areas of research. High circulating levels of IGF-I have been associated with an increased risk of developing breast, prostate and colon cancer [3]. Experimental systems and studies of clinical tumor biopsy specimens suggest that cancer progression is associated with increased expression of the IGF-1R [12,6]. There are a broad range of tumor types such as breast, colon, sarcoma, lung, prostate, thyroid and myeloma that express IGF-1R and thus IGF inhibition strategies may have clinical relevance in a large number of tumors [13–16,3].

Due to the fact that receptor pairs within the IGF system are covalently bound, CIX has the ability to not only block and downregulate IGF-1R homodimers, but can also bind hybrid IGF-1R/IR receptors in tumor cells [13]. This is an important point as hybrid receptors preferentially bind IGFs over insulin, and, therefore, may behave similar to IGF-1R homodimers in that they can lead to increased proliferation and protection from apoptosis. Because CIX binds to the IGF-1R with high affinity (Kd = 0.04 nM) and causes subsequent internalization and degradation of the receptor, it is effective in blocking both IGF-I and -II mediated signaling. CIX has been shown to indirectly inhibit both the ERK-MAPK as well as the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway through IGF-1R receptor blockade. CIX does not bind to or recognize the IR, however, and thus ligand binding of IGF-II or insulin by IR isoforms is not inhibited by treatment with CIX [13,17].

Given the complexity of the IGF signaling system, there are several other possible targets for interference by pharmacologic agents. Other than blockade of IGF-1R with antibody such as CIX, tyrosine kinase inhibition, antisense of IGF-1R and neutralizing antibody to IGF-I and -II represent some of the other strategies that are being used to disrupt IGF signaling and thwart unchecked neoplastic growth. Tyrosine kinase inhibition, however, can potentially interfere with normal physiologic action of insulin by blocking signals intended by ligand binding to IR-B and could possibly increase unintended side effects such as hyperglycemia. Neutralization antibodies are theoretically an attractive option as they would block IGF-II binding to IR-A, while not affecting the binding of insulin to IR-B. However, it is not clear whether this strategy could be saturated by IGF ligand upregulation at doses of therapy that would be tolerable. Such an approach would be expected to disrupt the negative feedback loop to the hypothalamus and pituitary, leading to upregulation of growth hormone (Figure 1). Currently, no antisense oligonucleotide strategies are being tested in clinical trials.

Figure 1. IGF system and regulation.

GH: Growth hormone; IGFBP: IGF binding protein.

3. Preclinical studies involving CIX

As CIX is in the early stages of clinical development, most of the data published so far involves preclinical investigational work. Most studies done can be broken down into three categories: CIX used as a single agent, CIX in combination regimens, or pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic studies in tumor models.

In vitro, CIX treatment inhibited ligand-induced growth of various tumor cell lines, including breast, prostate, pancreatic, lung, colon and myeloma [13,18,19,17]. In vivo tumor growth inhibition has also been demonstrated against various xenograft models, including human breast, colon, lung, pancreatic, prostate and renal carcinomas. While growth inhibition was common in these studies, tumor regressions were infrequent [13,14,19,17].

When CIX was used in combination regimens, enhanced tumor control was seen. In some models, the combination of CIX with chemotherapy agents such as paclitaxel, 5-FU/LV, cisplatin and CPT-11 led to sustained tumor control and improvement in survival [14,18,17]. The combination of cetuximab (mAb against EGFR) and CIX in the pancreatic cancer model BxPC-3 led to not only better growth inhibition, but also an increase in tumor growth regression. In a study done by Wu et al., the effects of CIX in preclinical models of multiple myeloma were evaluated. CIX combined with either melphalan or bortezomib had much greater effects on diminishing tumor burden and prolonging survival than either melphalan or bortezomib alone [15]. CIX treated tumors had significantly decreased vascularization compared with control tumors. Inhibition of IGF-1R by CIX in vitro suppressed both constitutive and IGF-I induced secretion of VEGF, indicating that an antiangiogenic mechanism associated with CIX treatment might contribute to its antitumor effect [15]. Wang et al. evaluated CIX in combination with irinotecan in an animal model of anaplastic thyroid cancer. They found that single-agent treatment with irinotecan resulted in 57% decrease in tumor volume, whereas when combined with CIX, there was a 93% reduction. This reduction in tumor volume translated to an increase in survival advantage as well [14].

The concept of targeting multiple growth factor pathways with combination antibody treatment has been tested as well. In a study using triple-targeted antibody therapy using CIX, cetuximab and DC-101 (an antibody to the VEGF receptor-2), Tonra et al. demonstrated profound antitumor activity in 11 human tumor xenograft models, including colorectal, pancreas, and head and neck cancer that could not be achieved with high-dose single-agent therapy [20].

O’Reilly et al. have shown impressive interactions between inhibitors of mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) and IGF-1R. In this study, multiple human cancer derived cell lines (MDA-MB-468, DU-145 and MCF-7) were tested in vitro. IGF-1R targeting with CIX prevented rapamycin-induced AKT activation and was, therefore, sensitized to the anticancer activity of mTOR inhibitors. In contrast, IGF-I administration reversed the antiproliferative effects of mTOR inhibitors [21]. These results support the clinical use of an IGF-1R inhibitor and an mTOR inhibitor used simultaneously. A trial with temsirolimus (mTOR inhibitor) and CIX is currently underway in patients with metastatic breast cancer [22].

Important mechanistic work has been performed by Plymate and his group at the University of Washington. In a study of prostate cancer xenografts, they found that CIX inhibits both androgen-dependent LuCaP 35 and androgen-independent LuCaP 35V but by different mechanisms. In the androgen-dependent xenografts, CIX induced tumor cell apoptosis or G1 cycle arrest whereas G2-M cycle arrest occurred in androgen-independent xenografts [17]. A different study evaluated the effect of CIX in combination with docetaxel in androgen-independent prostate cancer xenografts and found that CIX markedly augmented the effect of docetaxel on tumor growth. Gene expression profiles indicated that the post-treatment suppression of tumor growth may have been owing to enhanced negative regulation of cell cycle progression and/or cell survival-associated genes, some of which have been shown to induce resistance to docetaxel [23].

Pharmacodynamic and PK studies of CIX suggest that optimal tumor control can be achieved at a steady-state level of 60 – 158 µg/ml. Pharmacodynamic changes in xenograft models included downregulation of the IGF-1R levels and phosphorylation, inhibition of the downstream signals (MAPK and AKT) as well as induction of cellular events such as apoptosis, G1 or G2-M arrest, and decrease in the proliferation index [13,17].

4. Rationale for CIX combined with additional agents

Reversal or prevention of resistance to clinically useful anticancer therapies is arguably one of the most promising possibilities that may result from inhibition of the IGF signaling pathway. Resistance to chemotherapy is a common occurrence for cancer patients. When tumors are exposed to cytotoxic chemotherapy, the fractional effect hypothesis suggests that while sensitive cells die, a subset of less sensitive cells persist and continue to proliferate [3]. Malignant cells may also acquire resistance in response to chemotherapy through the induction of other genes, which promote cell growth and inhibit apoptosis [24,23]. The IGF system is an example of a pathway that may be ‘upregulated’ and plays a role in chemotherapy resistance. For example, HBL 100 human breast cancer cells become resistant to 5-FU, methotrexate and camptothecin when treated with IGF-1 [24]. IGF-1 administration rescues MCF-7 cells from doxorubicin and paclitaxel treatment [25]. IGF-1 provided a growth advantage by either promoting cell proliferation or inhibiting apoptosis. Alternatively, IGF may affect the response to chemotherapy by altering the efficacy of the drug. For example, in hepatocellular carcinoma cells, IGF-1 upregulates the expression of glutathione transferase, quenching the redox-cycling potential of doxorubicin [26]. By way of the [27,28] translocation, Ewing’s sarcoma utilizes autocrine and paracrine production of IGF-1 to activate IGF-1R and overcome chemotherapy sensitivity [29]. Growth of Ewing’s sarcoma tumors in vivo results in significant growth inhibition with vincristine and the IGF-1R inhibitor NVP-AEW541, compared to single agents [30]. In a study done by Allen et al., CIX combined with radiation therapy was demonstrated as more effective than either treatment alone in non-small cell cancer cell lines [31].

Hormonal therapy plays a vital role in the treatment of estrogen-responsive breast cancers. Selective estrogen receptor modulators such as tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors such as anastrazole have been designed to inhibit the biological and proliferative effects of estrogen receptor signaling. Despite the efficacy of these hormonal agents, drug resistance continues to be problematic and may be partially explained by crosstalk between the estrogen receptor and IGF signaling pathways. Growth of the human breast cancer cell line HBL 100 is inhibited by tamoxifen; however, simultaneous treatment with IGF-1 increases survival [24]. One way in which IGF-1 treated breast cancer cells escape tamoxifen induced apoptosis may be through IGF-mediated activation of AKT and subsequent phosphorylation of ER at serine-167, which leads to ligand-independent activation of ER [32]. When the IGF signaling system is inhibited by an anti-IGF-1R antibody or an IGF-1R tyrosine kinase inhibitor, growth of tamoxifen resistant MCF-7 cells declines. In addition, IGF-1R inhibition significantly inhibits estrogen-stimulated breast cancer cell growth [33,34]. In estrogen receptor positive breast cancer xenografts, blockade of IGF-1R by monoclonal antibody enhances the activity of tamoxifen in vivo [35,47]. Massarweh et al. have shown that the mechanism by which IGF-1R promotes tamoxifen resistance might be through a direct interaction between IGF-1R and ER [35]. The above studies support the rationale for using CIX in combination with hormonal therapy and there are currently two clinical trials that are studying their combined activity [22].

The HER/erbB receptor pathway also can be overexpressed in certain cancers and lead to increased tumor cell proliferation and resistance to apoptosis. Trastuzumab, a monoclonal antibody to HER2, is an effective therapy for the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer. Nevertheless, tumor cell resistance to trastuzumab is a common clinical problem. Data has accumulated to suggest that bidirectional crosstalk pathways between the erbB family of receptors and IGF-1R may play a role in resistance to drugs that target these pathways [36–38]. Expression of IGF-1R can overcome the cytotoxic effects of trastuzumab in the HER2 positive breast cancer cell line SKBR3 [36]. Moreover, SKBR3 breast cancer cells exhibited more cell death with trastuzumab when cultured in combination with an anti-IGF1R antibody [37]. Of note, both activated EGFR and HER2 are able to cause resistance to the dual kinase IGF-1R/IR inhibitor, BMS-536924 [38]. Taken together, these data suggest that resistance to both the IGF-1R and erbB receptor pathways may occur in a reciprocating fashion, suggesting simultaneous inhibition of HER receptors and IGF system receptors may be needed to overcome resistance. This concept is being tested in a Phase II clinical trial in HER2 positive breast cancers comparing the efficacy of lapatanib and capecitabine ± CIX [22].

Interfering with the IGF signaling pathway also seems to enhance sensitivity to EGFR small molecule inhibitors or anti-EGFR antibodies. In a study done by Camirand et al., inhibition of IGF-1R signaling enhanced growth-inhibitory and proapoptotic effects of gefitinib in human breast cancer cells [39]. Chakravarti et al. demonstrated that resistance to EGFR therapy in human glioblastoma cells was mediated by IGF1-R through continued activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling [40]. Both of these studies demonstrate possible benefits of combining multiple targeted therapies to overcome upregulation of other signaling pathways when one has been disrupted. Investigation of the efficacy of this strategy is underway in a clinical trial involving CIX and erlotinib in a Phase II trial for patients with stage III and IV NSCLC. Further studies co-targeting IGF-1R and members of the erbB receptor family are ongoing or in development [22].

Both in vitro as well as in vivo studies have shown that treatment with mTOR inhibitors can lead to upregulation of AKT phosphorylation in tumors and that feedback activation of AKT is mediated by the IGF-1R/IGF pathway. Because IGF1-R inhibitors such as CIX can reduce the rapamycin-induced AKT phosphorylation, combination of the two agents is an ongoing strategy that is currently being evaluated in clinical trials [21,41,46]. O’Reilly et al. have shown impressive interactions between inhibitors of mTOR and IGF-1R. In this study, IGF-1R targeting with CIX prevented rapamycin-induced AKT activation and was, therefore, sensitized to the anticancer activity of mTOR inhibitors. In contrast, IGF-I administration reversed the antiproliferative effects of mTOR inhibitors [21]. These results support the clinical use of an IGF-1R inhibitor and an mTOR inhibitor used simultaneously and a clinical trial with temsirolimus (mTOR inhibitor) and CIX is currently underway in patients with metastatic breast cancer [22].

5. Early clinical data regarding CIX

CIX is in the early stages of clinical development and there have been two concurrent ImClone sponsored Phase I, single-agent studies performed in solid tumors so far. There are many ongoing studies with CIX either as a single agent or in combination with other targeted therapies or traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy [22].

In the first trial (CP13-0501), CIX was administered weekly with planned dose escalation from 3, 6, 10, 15 to 27 mg/kg. Side effects associated with the drug were few and are listed in detail in the section below. There were no objective responses among the 16 patients. Nine patients experienced stable disease (> 6 weeks): four patients at the 3 mg/kg dose, including two patients for > 9 months (male breast cancer and HCC); two patients at the 6 mg/kg dose (bladder and endometrial cancer); two patients at the 10 mg/kg dose (pancreatic cancer and pheochromocytoma); and one patient at a dose of 15 mg/kg (lymphagiomatosis). The maximal tolerated dose has not been reported; however, ongoing Phase II combination studies are proceeding at 6 mg/kg on a weekly schedule. [42].In the second trial (CP13-0502), CIX was given on a biweekly schedule for a total of 15 patients; 5 at the 6 mg/kg dose, 8 at the 10 mg/kg dose and 2 at the 15 mg/kg dose [43]. PK analysis showed dose-dependent elimination and nonlinear exposure, consistent with saturable clearance mechanisms. Dose escalation was halted without dose-limiting toxicity based on achievement of minimum target concentration of CIX. No objective responses were observed, but two patients experienced stable disease greater than 12 weeks. A patient with thymoma of the right anterior mediastinum and a patient with adenocarcinoma of the ovary were the two patients who had an extended period of stable disease attributed to the use of CIX. The maximal tolerated dose has not been reported [43].

6. Side effects associated with CIX

Overall, CIX has been well tolerated with a reasonable side effects profile. In the CP13-0501 trial described above, the most significant adverse effect was hyperglycemia and was observed in 4/16 and considered dose-limiting toxicity (grade 3) in two patients. Other adverse effects observed included infusion reaction, anemia, psoriasis, pruritis, rash, acne, arthralgia, dizziness, fatigue and nephrotoxicity (one instance each). A small increase in body fat percentage was noted in 5/6 patients for whom DEXA scan results were available both before and after 6 weeks of treatment (median 1% increase). Mild weight loss was noted in 7/9 with a median decrease of 1 kg (1% of body weight). No infectious adverse events have been noted during Phase I studies of CIX [42].

In the CP13-0502 trial, adverse effects of any grade believed to be related to CIX were reported in two patients. These included eructation, nausea, fatigue, headache, paresthesia, alopecia and acneform dermatitis. No adverse events of grade 3 or higher were considered related to CIX, and no patients discontinued therapy owing to an adverse event [43].

The mechanism of the hyperglycemic effects of CIX is unclear, although it is not probably owing to nonspecific binding of the IR. A potential mechanism involves the neo-glycogenic effects of human growth hormone, which seems to be upregulated in response to IGF-1R inhibition in some patients [28].

7. Pharmacodynamics/pharmacokinetics of CIX

PK analysis of CIX given on a weekly schedule in the Phase I study CP13-0501 demonstrated a mean half-life of 148 and 209 h, maximum concentration of 333 and 415 µg/ml, and AUC0 − ≈ of 51,317 and 80,727 (h µg)/ml at 3 and 6 mg/kg dosage levels, respectively. At the steady-states of 6 and 10 mg/kg doses, the trough levels reached were 145 and 259 µg/ml, respectively. CIX was well tolerated at doses up to 10 mg/kg. Monitoring of circulating markers revealed a marked elevation of growth hormone and IGF-I after treatment with CIX. There was also an increase in the levels of insulin and C-peptide post-treatment [42].

8. Future directions and ongoing studies with CIX

Currently, there are 26 ongoing clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of CIX as either a single agent or in combination with other targeted therapies or cytotoxic chemotherapy agents [22]. These initial studies are evaluating many of the high priority targets based on the preclinical and early clinical data described above (Table 1). While there are a few single-agent studies in sarcomas and liver cancer, most clinical investigations have been developed to test the hypothesis that IGF-1R inhibition is a major mechanism of resistance to the base treatment; thus, blockage of IGF-1R will enhance the overall activity of the regimen. It is likely that clinical investigations with CIX will continue as combinations for this reason. It is hoped that biomarker studies in these ongoing clinical trials will help identify subsets of patient populations who are more likely to experience benefits from targeting IGF-1R. It is anticipated that future investigations would involve validation of these markers and clinical investigations targeting these patient subpopulations.

Table 1.

Studies currently accruing patients with CIX.

| Agents | CIX dosing frequency |

Clinical setting | Phase |

|---|---|---|---|

| CIX | Every 2 weeks | Patients with tumors who no longer respond to treatment or for whom no further treatment is available* | I |

| CIX | Every 2 weeks | A five-tier, Phase II open-label study in advanced sarcomas (Ewing’s/PNET, rhabdomyosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, adipocytic sarcoma, synovial sarcoma) | II |

| CIX | Every 2 weeks | Adrenocortical carcinoma | I/II |

| CIX | Every 2 weeks | Metastatic prostate cancer with no previous cytotoxic chemotherapy§ | II |

| CIX | Every 1 week | Patients with tumors who no longer respond to treatment or for whom no other treatment is available§ | I |

| CIX | Every 1 week | Patients with malignant solid tumors with no curative/beneficial therapy available. Includes osteosarcoma, Ewing’s/PNET, rhabdomyosarcoma, synovial sarcoma, neuroblastoma, Wilms tumor, hepatoblastoma, adrenocortical carcinoma, retinoblastoma | II |

| CIX | Every 1 week | Advanced liver cancer | II |

| CIX | Every 1 week | Young patients with relapsed or refractory Ewing sarcoma/peripheral PNET or other solid tumor§ | I |

| CIX ± cetuximab | Every 2 weeks | Recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck | II |

| CIX ± cetuximab | Every 2 weeks | Recurrent of metastatic colorectal cancer following disease progression on EGFR-targeted therapy‡ | II |

| CIX or IMC-1121B + mitoxantrone and prednisone | Every 1 week | Metastatic androgen-independent prostate cancer, following disease progression on docetaxel-based chemotherapy | II |

| CIX + androgen deprivation therapy | Every 2 weeks | Preoperative treatment for prostate cancer | II |

| CIX + depot octreotide | Every 2 weeks | Metastatic carcinoid or islet cell cancer | II |

| Mitotane ± CIX | Every 2 weeks | Recurrent, metastatic, or primary adrenocortical cancer that cannot be removed by surgery (metastatic or primary unresectable)¶ | II |

| Cetuximab + irinotecan ± CIX | Every 2 weeks | Metastatic K-Ras wild-type colorectal cancer following progression on an oxaliplatin/bevacizumab-containing regimen | II |

| Gemcitabine + carboplatin + cetuximab ± CIX | Every 1 week | Frontline therapy in Stage IIIb or IV NSCLC¶ | II |

| CIX + temsirolimus | Every 1 week | Locally advanced or metastatic cancer (solid and hematological malignancies) | I |

| CIX + temsirolimus | Every 1 week | Locally recurrent or metastatic breast cancer | I/II |

| Erlotinib ± CIX | Every 1 week | Stage III or IV NSCLC | II |

| CIX + doxorubicin | Every 1 week | Unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic soft tissue sarcoma | I/II |

| CIX ± antiestrogens | Every 2 weeks | Metastatic breast cancer patients who progressed on antiestrogen therapy | II |

| Gemcitabine and erlotinib ± CIX | Every 1 week | Metastatic pancreatic cancer that cannot be removed by surgery | I/II |

| Capecitabine and lapatinib ± CIX | Every 1 week | Previously treated HER-2 positive stage IIIB, stage IIIC or stage IV breast cancer‡ | II |

| Cisplatin and etoposide ± GDC-0449 or CIX | Every 1 week | Standard therapy ± CIX or Hedgehog inhibitor GDC-0449 for extensive stage small cell lung cancer¶ | II |

| CIX + temsirolimus | Every 1 week | Advanced solid tumors | I |

| CIX + temsirolimus | Every 1 week | Young patients with solid tumors that have recurred or not responded to treatment | I |

Included are studies completed*, suspended‡, active but not accruing§ or not yet accruing¶ at the time of this report.

CIX: Cixutumumab; PNET: Primitive neuroectodermal tumor.

Abstracted from www.clinicaltrials.gov.

9. Expert opinion

CIX is a drug that shows promise not only as a single agent, but also in combination with other targeted and cytotoxic treatments. As a single agent, however, CIX arrests growth but rarely causes significant regression of a tumor. When combined with further agents, enhanced antitumor activity has been observed in preclinical models. As such, CIX as well as other IGF-1R inhibitors will probably find their niche in combination with other targeted therapies as well as in combination with cytotoxic agents. Preclinical studies as discussed above indicate that CIX will probably be most effective for the tumor types in which its use is currently being tested: Ewing’s sarcoma, NSCLC, sarcoma, breast cancer, head and neck cancer, pancreatic cancer, liver cancer and adrenocortical carcinoma. It is not clear at this time what advantage or disadvantage CIX will have over the other antibody antagonists against IGF-1R. The Pfizer anti-IGF-1R antibody has the distinction of not only being the most clinically developed, including demonstration of early efficacy in combination with chemotherapy in NSCLCA, but also has a longer half-life (~ 21 days), likely secondary to its IgG2 subtype [44,45]. However, CIX has similarities as far as IgG subtype and half-life to many of the other agents in development, such as MK-0646 and R1507, which necessitate a less convenient treatment schedule. Whether these differences will be overcome by unique benefits of CIX is unknown. Differences in the frequency and intensity of adverse events may be an important determinant in whether CIX will succeed in the current environment of similar IGF-1R-targeting agents competing for similar patient populations.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

P Haluska receives research funds from ImClone. He is an unpaid consultant for ImClone and Mayo and has received funds for research related to cixutimumab. KP McKian states no conflict of interest and has received no payment in preparation of this manuscript.

Bibliography

- 1.Rowinsky EK, Youssoufian H, Tonra JR, et al. IMC-A12, a human IgG1 monoclonal antibody to the insulin-like growth factor I receptor. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(18 Pt 2):5549s–5555s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pandini G, Frasca F, Mineo R, et al. Insulin/insulin like growth factor I hybrid receptors have different biological characteristics depending on the insulin receptor isoform involved. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(42):39684–39695. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202766200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pollak MN, Schernhammer ES, Hankinson SE. Insulin-like growth factors and neoplasia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:505–518. doi: 10.1038/nrc1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baserga R. The IGF-I receptor in cancer research. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253:1–6. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams TE, Epa VC, Garrett TP, Ward CW. Structure and function of the type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57:1050–1093. doi: 10.1007/PL00000744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blakesely VA, Butler AA, Koval AP, et al. IGF-I receptor function. In: Rosenfeld RG, Robers CT Jr, editors. The IGF system: molecular biology, physiology, and clinical applications. New Jersey: Humana Press; 1999. pp. 143–163. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Remacle-Bonnet M, Garrouste F, Baillat G, et al. Membrane rafts segregate pro- from anti-apoptotic insulin-like growth factor-I receptor signaling in colon carcinoma cells stimulated by members of the tumor necrosis factor superfamily. Am J Pathol. 2005;167(3):761–773. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62049-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang X, Lin M, van Golen KL, et al. Multiple signaling pathways are activated during insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) stimulated breast cancer cell migration. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;93(2):159–168. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-4626-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siri S, Chen MJ, Chen TT. Biological activity of rainbow trouth Ea4-peptide of the pro-insulin-like growth factor (pro-IGF)-I on promoting attachment of breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231) via alpha2- and beta1-integrin. J Cell Biochem. 2006;99(6):1524–1535. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pandini G, Vigneri R, Constantino A, et al. Insulin and insulin-like-growth factor-I (IGF-I) receptor overexpression in breast cancers lead to insulin/IGF-1 hybrid receptor overexpression: evidence for a second mechanism of IGF-I signaling. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;57:1935–1944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kido Y, Nakae J, Accili D. Clinical review 125: the insulin receptor and its cellular targets. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;863:972–979. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.3.7306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guerra FK, Eijan AM, Puricelli L, et al. Varying patterns of expression of insulin-like growth factors I an II and their receptors in murine mammary adenocarcinomas of different metastasizing ability. Int J Cancer. 1996;65:812–820. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960315)65:6<812::AID-IJC18>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burtrum D, Zhu Z, Lu D, et al. A Fully human monoclonal antibody to the insulin-like-growth factor I receptor blocks ligand-dependent signaling and inhibits tumor growth in vivo. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8912–8921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Z, Chakravarty G, Kim S, et al. Growth-inhibitory effects of human anti-insulin-like growth factor I receptor antibody (A12) in an orthotopic nude mouse model of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4755–4765. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu KD, Zhou L, Burtrum D, et al. Antibody targeting of the insulin-like-growth factor I receptor enhances the anti-tumor response of multiple myeloma to chemotherapy through inhibition of tumor proliferation and angiogenesis. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56:343–357. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0196-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weroha SJ, Haluska P. IGF-1 receptor inhibitors in clinical trials—early lessons. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2008;13:471–483. doi: 10.1007/s10911-008-9104-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu JD, Odman A, Higgins LM, et al. In vivo effects of the human type I insulin-like growth factor receptor antibody A12 on androgen-dependent and androgen-independent xenograft human prostate tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3065–3074. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anti-insulin-like growth factor-I receptor (IGF-1R) monoclonal antibody investigator’s brochure. Imclone Systems, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bertrand FE, Steelman LS, Chappell WH, et al. Synergy between an IGF-1R antibody and Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway inhibitors in suppressing IGF-1R mediated growth in hematopoietic cells. Leukemia. 2006;20:1254–1260. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tonra JR, Deevi DS, Corcoran E, et al. Combined antibody mediated inhibition of IGF-1R, EGFR, VEGFR2 for more consistent and greater anti-tumor effects. Eur J Cancer. 2006;4:207. [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Reilly KE, Rojo F, She QB, et al. mTOR inhibition induces upstream receptor tyrosine kinase signaling and activates AKT. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1500–1508. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Available from: www.clincaltrials.gov.

- 23.Wu JD, Haugk K, Coleman I, et al. Combine in vivo effect of A12, a type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor antibody, and docetaxel against prostate cancer tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(20 Pt 1):6153–6160. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunn SE, Hardman RA, Kari FW, Barret JC. Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) alters drug sensitivity of HBL100 human breast cancer cells by inhibition of apoptosis induced by diverse anticancer drugs. Cancer Res. 1997;57(13):2687–2693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gooch JL, Van Den Berg CL, Yee D. Insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) rescues breast cancer cells from chemotherapy-induced cell death-proliferative and anti-apoptotic effects. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1999;56(1):1–10. doi: 10.1023/a:1006208721167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee JY, Han CY, Yang JW, et al. Induction of glutathione transferase in insulin-like growth factor type I receptor-overexpressed hepatoma cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72(4):1082–1093. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.038174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Devita VT, Jr, Young RC, Canellos GP. Combination versus single agent chemotherapy: a review of the basis for selection of drug treatment of cancer. Cancer. 1975;35(1):98–110. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197501)35:1<98::aid-cncr2820350115>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vasilcanu R, Vasilcanu D, Rosengren L, et al. Picropodophyllin induces downregulation of the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor: potential mechanistic involvement of Mdm2 and beta-arrestin 1. Oncogene. 2008;2711:1629–1638. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yee D, Favoni RE, Lebovic GS, et al. Insulin-like growth factor I expression by tumors of neuroectodermal origin with the t(11:22) chromosomal translocation. A potential autocrine growth factor. J Clin Invest. 1990;86(6):1806–1814. doi: 10.1172/JCI114910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scotlandi K, Manara MC, Nicoletti G, et al. Antitumor activity of the insulin-like growth factor I receptor kinase inhibitor NVP-AEW541 in musculoskeletal tumors. Cancer Res. 2005;65(9):3868–3876. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allen GW, Saba C, Armstrong EA, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor signaling blockade combined with radiation. Cancer Res. 2007;67(3):1155–1162. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campbell RA, Bhat-Nakshatri P, Patel NM, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT mediated activation of estrogen receptor alpha: a new model for anti-estrogen resistance. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(13):9817–9824. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010840200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parisot JP, Hu XF, DeLuise M, Zalcberg JR. Altered expression of the IGF-1 receptor in a tamoxifen-resistant human breast cancer cell line. Br J Cancer. 1999;79(5–6):693–700. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knowlden JM, Hutcheson IR, Barrow D, et al. Insulin-like growth factor I receptor signaling in tamoxifen resistant breast cancer: a supporting role to the epidermal growth factor receptor. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4609–4618. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Massarweh S, Osborne CK, Creighton CJ, et al. Tamoxifen resistance in breast tumors is driven by growth factor receptor signaling with repression of classic estrogen receptor genomic function. Cancer Res. 2008;68(3):826–833. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu Y, Zi X, Zhao Y, et al. Insulin-like growth factor I receptor signaling and resistance to trastuzumab (Herceptin) J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(24):1852–1857. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.24.1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nahta R, Yuan LX, Zhang B, et al. Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 heterodimerization contributes to trastuzumab resistance of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65(23):11118–11128. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haluska P, Carboni JM, Ten Eyck C, et al. HER receptor signaling confers resistance to the insulin-like growth factor-I receptor inhibitor, BMS-536924. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7(9):2589–2598. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Camirand A, Zakikhani M, Young F, Pollak M. Inhibition of insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor signaling enhances growth-inhibitory and proapoptotic effects of gefitinib (Iressa) in human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7:R570–R579. doi: 10.1186/bcr1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chakravarti A, Loeffler JS, Dyson NJ. Insulin-like growth factor receptor 1 mediates resistance to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor therapy in primary human glioblastoma cells through continued activation of phospoinositide 3-kinase signaling. Cancer Res. 2002;62:200–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wan X, Harkavy B, Shen N, et al. Rapamycin induces feedback activation of AKT signaling through an IGF-1R dependent mechanism. Oncogene. 2006 doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Higano CS, Yu EY, Whiting SH, et al. A phase I, first in man study of weekly IMC-A12, a fully human insulin-like growth factor receptor IgG1 monoclonal antibody in patients with advanced solid tumors. ASCO. 2007:A269. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rothenberg ML, Poplin E, Sandler AB, et al. Phase I dose-escalation study of the anti-IGF-IR recominant IgG1 monoclonal antibody (Mab) IMC-A12, administered every other week to patients with advanced solid tumors. Mol Targets Cancer Ther. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karp DD, Paz-Ares LG, Novello S, et al. Phase II study of the anti-insulin-like growth factor type 1 receptor antibody CP-751,871 in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin in previously untreated, locally advanced, or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.9331. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haluska P, Shaw HM, Batzel GN, et al. Phase I dose escalation study of the anti insulin-like growth factor-I receptor monoclonal antibody CP-751, 871 in patients with refractory solid tumors. Clin Can Res. 2007;13(19):5834–5840. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frogen T, Jepsen JS, Larsen SS, et al. Antiestrogen resistant human breast cancer cells require activated protein kinase B/Akt for growth. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005;12:599–614. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ye JJ, Liang SJ, Guo N, et al. Combined effects of tamoxifen and a chimeric humanized single chain antibody against the type I IGF receptor on breast tumor growth in vivo. Horm Metab Res. 2003;35:836–842. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]