Abstract

Lymphoproliferative disorders are heterogeneous malignancy characterized by the expansion of a lymphoid clone more or less differentiated. At the level of the oral cavity, the lymphoproliferative disorder can occur in various ways, most commonly as lymphoid lesions with extranodal externalization, but sometimes, oral lesions may represent a localization of a disease spread. With regard to the primary localizations of lymphoproliferative disorders, a careful examination of the head and neck, oral, and oropharyngeal area is necessary in order to identify suspicious lesions, and their early detection results in a better prognosis for the patient. Numerous complications have been described and frequently found at oral level, due to pathology or different therapeutic strategies. These complications require precise diagnosis and measures to oral health care. In all this, oral pathologists, as well as dental practitioners, have a central role in the treatment and long-term monitoring of these patients.

1. Introduction

Under the name of lymphoproliferative disorders various disease patterns are included which are characterized by the expansion of a lymphoid clone more or less differentiated. The application in recent times, of immunological methods for determining the phenotype of many cell components, together with the acquisitions of cytogenetic and molecular biology, as well as clinical behavior, have helped to relatively define a wide range of diseases that may present a heterogeneous clinical and morphological picture. In fact, the last classification of lymphoproliferative disorders lists 40 types of lymphoproliferative syndromes to immunophenotype B and 23 to immunophenotype T [1]. At the level of the oral cavity, the lymphoproliferative disorder can occur in various ways, most commonly as lymphoid lesions with extranodal externalization, but sometimes, oral lesions may represent a localization of a disease spread [2]. Under the key research that sees lymphoproliferative disorders associated with injury or events at the oral cavity, the present paper proposes a comprehensive classification as listed in Table 1 and deeply described below.

Table 1.

Classification of the oral pathologies associated with lymphoproliferative disorders (see text for details).

| Group | Primary disorder | Localization of the primary disorder | Secondary (a) or associated (b) disorder | Localization of the secondary or associated disorder |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lymphoproliferative disorders | Oral cavity | None | — |

| 2 | Lymphoproliferative disorders | Oral cavity | Lymphoproliferative disorders (a) | Other body districts |

| 3 | Lymphoproliferative disorders | Other body districts | Lymphoproliferative disorders (a) | Oral cavity |

| 4 | Oral lesions | Oral cavity | Lymphoproliferative disorders (b) | Other body districts |

| 5 | Lymphoproliferative disorders | Other body districts | Oral lesions (a) | Oral cavity |

| 6 | Lymphoproliferative disorders | Other body districts | Oral lesions secondary to the treatment of the primary disorder | Oral cavity |

| 7 | AIDS | — | AIDS-related lymphoproliferative disorders | Oral cavity |

Oral lesions refer to all of the diseases excluding lymphoproliferative disorders.

2. Classification and Related Aspects of the Oral Pathologies Associated with Lymphoproliferative Disorders

2.1. Group 1: Primary Oral Lymphoproliferative Disorders Limited to the Oral Cavity that Will not Invade Other Body Districts

Primary extranodal involvement can be seen in 10% to 35% of cases of non-Hodgkin lymphomas. These locations include the gastrointestinal tract, skin, testicles, kidneys, and bones [3, 4]; the NHL of the central nervous system account for 1% of cases [5, 6]. Although the oral involvement of NHL is rare, they are the second most common oral malignant disease after oral squamous cell carcinoma [7, 8], constituting of 2.2% of all malignancies of the head-neck, 3.5% of intraoral malignancies, 5% of tumors of the salivary glands, and 2.5% of all cases of NHL [8]. Although every other site may be affected, Ring Waldayer is the most commonly involved [9]. The WHO system classifies NHL as indolent, aggressive, and highly aggressive. Indolent lymphoma accounts for 40% af all NHL with the most common type being follicular lymphoma; aggressive lymphoma accounts for approximately 50% of cases and include diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and T-cell natural killer (NK) cell lymphoma; highly aggressive lymphoma includes EBV-associated Burkitt lymphoma and lymphoblastic lymphoma [10]. Even though each type of NHL can occur at the level of oral cavity, the most common types are large-cell lymphoma and lymphoma of small lymphocytes lymphoma; mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, Burkitt's lymphoma, and immunocytoma, immunoblastic lymphoma are also reported [8, 11, 12]. The most common signs and symptoms with which the NHL will have intraoral include tissue swelling, tooth loss, and paresthesia. The radiographic measurements can highlight widespread osteolysis with loss of lamina dura. Oral lesions may appear as exophytic neoplasms, erythematous, asymptomatic, often with superficial ulcerations secondary to chronic trauma [11] (Figure 1).

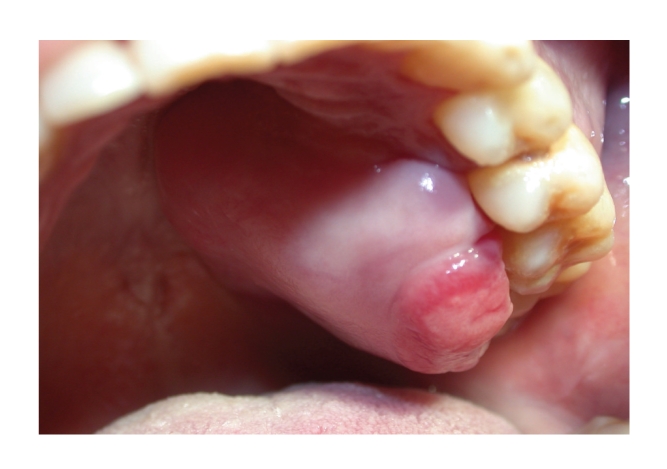

Figure 1.

Primary extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphoma: painless mass involving the left palate.

Hodgkin's disease is a form of malignancy characterized by proliferation of neoplastic cells (Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells) associated with a polymorphic cellular component (lymphocytes, histiocytes, eosinophils, neutrophils, and plasma cells), considered to be reactive [13]. From its initial description until the 1990s, the nature and lineage of the Reed-Sternberg cell and the inflammatory infiltrate that compromises Hodgkin disease were debated. The application of PCR technique revealed that Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells were clonal B cells in 98% of the patients, leading to the change of the designation of Hodgkin disease into Hodgkin lymphoma (LH) in the WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms [1]. Primary oral and oropharyngeal lesions are rare [14]. Since the Waldayer ring is commonly involved by NHL that sometimes shows cells of Reed-Sternberg cell-like, the diagnosis of LH is difficult, especially when there are only small biopsy specimens [15, 16]. The most common site involved is the ring of Waldayer followed by the lips [17], tongue base [18, 19], buccal mucosa [20, 21], and parotid gland [22, 23].

The oral manifestations by plasma cell tumors can occur in three different ways: as a consequence of the local manifestation of multiple myeloma, bone plasmacytoma as solitary, or as extramedullary plasmacytoma [24]. The primary manifestations of plasma cell neoplasms at the oral level are represented by solitary and extramedullary plasmacytoma.

The Plasmacytoma of bone can be considered a localized solitary myeloma (Figure 2). Solitary bone plasmacytoma is a malignant monoclonal gammopathy [25, 26]; it is a plasma cell cancer that occurs as a single osteolytic lesion without plasmacytosis of the bone marrow and that is capable of secreting monoclonal M protein [27, 28]. This disease accounts for 10% of all plasma cell tumors and can strike [25, 27, 28], although rarely, in the oral cavity, showing a predilection for the mandibular retromolar area [29]; its radiological appearance may have one of two patterns, as either an oval-shaped lytic image with destruction of the cortical bone, or as a hyperinsufflating lesion showing a convex bicortical bone [30].

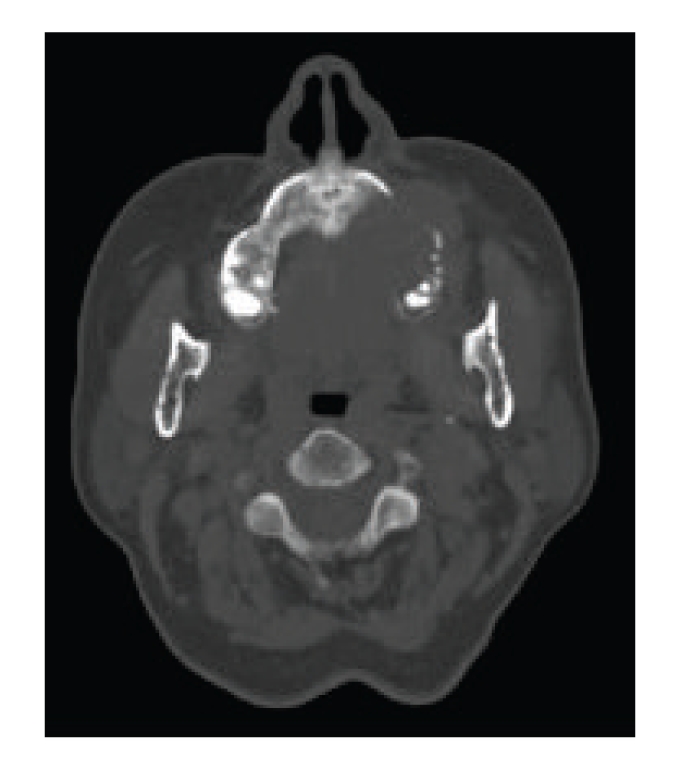

Figure 2.

Plasmacytoma: axial noncontrast CT image at the level of left maxillary sinus demonstrates an expansile, destructive intraosseous lesion involving the left maxillary sinus.

Instead, the extramedullary plasmacytoma is a plasma cell tumor located separately from the bone marrow [31]; it is found in all parts of the body where this lymphoid tissue [32–38], in 90% of the extramedullary plasmacytoma, is present in the head and neck. Clinically [39–41], the plasmacytoma extraosseous is present as a sessile or pedunculated exophytic neoformation, circumscribed or infiltrative, ranging in color from red-purple to gray or yellow-white [42–50].

2.2. Groups 2: Primary Oral Lymphoproliferative Disorders that May Eventually Invade Other Body Districts

The oral manifestations of multiple myeloma (MM), a disease characterized by the proliferation and accumulation in the bone marrow of a clone of plasma cells to produce a homogeneous monoclonal protein [13, 30, 51, 52], are extensively reported in the literature; the oral manifestations are the initial sign of submission in 12% to 15% of cases of MM [53–55]. The oral features include facial, oral, and dental pain, numbness and paresthesia, swelling, soft tissue neoplasms [56], tooth mobility, bleeding, and deposit of amyloid substance especially on the tongue [57–60]. Other examples of oral lesions as first manifestation of lymphoproliferative disorders may be the infiltration of the oral mucosa by a B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia [61], the lymphomatous papulosis, a condition mucocutaneous applicant, self-limited, characterized by papular eruptions [62], and Mycosis fungoides, T-cell cutaneous lymphoma in which the involvement of the oral cavity is a rare event but well documented [63, 64].

2.3. Group 3: Primary Systemic Lymphoproliferative Disorders That May Eventually Invade Oral Cavity

In addition to entering into this category, the previously treated lymphoproliferative disorders, where the diagnosis of oral lymphoid malignancy was subsequent to an indication of their early sign, mentioned in this regard a clinical-pathological entity of which we have evidence in the literature for over a century of mycosis fungoides (MF), chronic lymphoproliferative disorder with predominantly cutaneous involvement characterized by the proliferation of T lymphocytes that in advanced stages of the disease can accumulate also in lymphoid organs, bone marrow, and peripheral blood (Sezary Syndrome) [13]. Involvement in oral MF is an occasional finding observed from 7.4% to 18% of patients undergoing necropsy [65, 66]. Despite these findings relatively frequent mucosal involvement in vivo is a rare event; there is no predisposition to sex; age of onset varies from 36 to 81 years, with an average of 61 years. Oral sites most frequently involved are the tongue, palate, gingiva, buccal mucosa, lips, and oropharynx. In almost all patients, the lesions skin prior to the mucosa over a period of time ranging from 7 months to 40 years [67].

2.4. Groups 4: Primary Oral Lesions (Excluding Lymphoproliferative Disorders) That Are Associated with Systemic Lymphoproliferative Disorders, That Is, Paraneoplastic Pemphigus

Here is a list of non-specific signs and symptoms present in association with lymphoproliferative disorders of the oral cavity: lymphadenopathy, trismus, erythema, epiphora, pain, swelling, facial asymmetry or swelling of buccal mucosa, sinusitis, increased lacrimation and abscesses of the lacrimal sac, diplopia, nasal obstructions, sepsis, fever, runny nose, prosthetic instability, headache, and paresthesia idiopathic epistaxis. Suspicion of malignancy usually develops only after these inflammatory symptoms have not responded to conventional treatment protocols, upon which more accurate evaluations are required. Although oral lymphomas are extremely rare [68, 69], they can occur earlier and be placed in the differential diagnosis with non-specific inflammatory processes. Moreover, the early recognition of these subtle cancers can decrease their morbidity [70].

Paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP), or paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome is a rare autoimmune vesiculobullous disease first described by Anhalt et al. in 1990 in patients with occult malignancies [71, 72]. The PNP may have mucocutaneous and systemic manifestations. Erosive eye lesions, sinuses, oral cavity, the gastrointestinal system, and respiratory and genital epithelium could affect them. Clinically, lesions may occur as polymorphic, such as pemphigus, bullous pemphigoid, erythema multiforme, the graft-versus-host disease, and lichen planus [73–75] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Paraneoplastic pemphigus: multiple erosions affecting the marginal gingival.

Dermatomyositis (DM) is a rare inflammatory microangiopathic disease that affects skeletal muscles, with clinical externalization as characteristics mucocutaneous manifestations.

Oral lesions in paraneoplastic DM (leucoerythroplasia and ulcerative lesions) have rarely been described in the literature [76–79]. The DM is totally resolved if the underlying disease is treated and the resurgence of DM expresses relapse of malignancy [76, 79].

In the literature, there are reports of a single case of multiple myeloma with first manifestation at the oral level under the clinical aspects of lichen planus, showing extensive and irregular erosions present at buccal mucosa, labial, palatal mucosa, and ventral tongue [80].

2.5. Group 5: Primary Lymphoproliferative Disorders That May Eventually Invade Oral Cavity Yielding Lesions (Excluding Lymphoproliferative Disorders)

The literature contains many works that correlate the paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP), a rare autoimmune vesiculobullous disease underlying a malignancy [71, 72], with typical oral lesions of lichen planus [81] or lichenoid reactions [82]. In the literature there are numerous works reported that associate mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP) with malignancies, including lung cancer [83], pancreatic adenocarcinoma [84], gastric adenocarcinoma [85], and squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva [86] there are only two cases reported of MMP with oral manifestations associated to lymphoproliferative disorders: a B-cell lymphoma [87] and chronic lymphocytic leukemia [88]. It has been described in the literature that large amount of cases have connection between bullous pemphigoid (BP) and lymphoproliferative disorders such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia [89–91] and lymphoblastic lymphoma [92].

Necrotizing oral processes, although rare in the general population, can rapidly evolve in devastating stages in immunocompromised patients [93–96] and are often associated with periodontal disease. These are patients with lymphoproliferative disorders such as acute lymphoblastic leukemia, which developed necrotic processes at the level of the oral cavity not associated with typical ulcer-necrotizing periodontal diseases, but by bacteria in the oral cavity unusually found as Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Patients with impaired lymphocyte function or reduced counts of neutrophils, due to lymphoproliferative disorders, have led to the acquisition of new infections and/or exacerbation or reactivation of latent infection (periapical periodontitis and herpes simplex). In many cases the clinical presentation of oral infections may be atypical when compared to those normally seen in healthy patients.

The origin of odontogenous infection of the pulp and periodontal is frequently observed in patients with lymphoproliferative disorders and should be suspected when orofacial pain, extensive dental restorations, and dental caries and periapical radiopacity occur [97, 98].

Oropharyngeal candidiasis is the most common fungal infection in cancer patients [99–101]. The candidiasis may present as pseudomembranous candidiasis, erythematous, hyperplastic, or angular cheilitis. The symptoms include general discomfort, dysgeusia, xerostomia, and mouth burn. Deep fungal infections should be suspected in patients with solitary ulcer that does not retreat. This group includes infections such as aspergillosis, histoplasmosis, and that by Zygomycetes, and the treatment requires aggressive treatment with intravenous azoles, amphotericin B, and echinocandins [102].

Primary infection or reactivation of herpes viruses is common in patients with lymphoproliferative disorders especially during the advanced stages of the disease. Infection with herpes simplex is most common in these patients; the reactivation of the Varicella-Zoster virus (VZV) is less common [103]. Epstein-Barr virus infection (EBV) is associated with oral hairy leucoplakia, a very rare whitish lesion that occurs on the lingual lateral margins in myelosuppressive patients [104, 105]. Infection by Cytomegalovirus (CMV) can occur on any intraoral mucosal surface in the form of an ulcer-free character of specificity, which persists for weeks or months.

Because of thrombocytopenia in the course of lymphoproliferative disorders, intraoral bleeding is commonly observed, which is present with petechiae, bruising, and occasionally with the formation of hematomas (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Thrombocytopenia: traumatic hematoma of the soft palate.

2.6. Group 6: Oral Complications Due to Systemic Treatment for Lymphoproliferative Disorders (i.e., Chemotherapy, Radiotherapy, Autologous, or Allogeneic Bone Marrow Transplant)

Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy —

In addition to what is included in this paper the oral infectious complications (bacterial, fungal, viral), previously treated on immunosuppression induced by lymphoproliferative disorder, and here remembered as a possible consequence of drug-induced immunodeficiency, we will consider the common characteristic found in the course of oncohaematology treatment regimens. Patients with lymphoproliferative disorders who are treated with high doses of radiotherapy at the head and neck level, associated with aggressive chemotherapy regimens, are at greatest risk of developing oropharyngeal mucositis. Xerostomia is often present in patients with lymphoproliferative disorders treated with radiotherapy in the head and neck region due to damage of the major salivary glands, which are still included in the irradiation of tumors. As another long-term complication of radiation therapy for head and neck lymphomas in patients who underwent radiotherapy, we noticed the osteoradionecrotic maxillary bone as a result of permanent damage of the capillary bed of bone and osteocytes caused by radiation.

Autologous Transplantation —

Oral complications are observed in 85% of cases of patients after autologous bone marrow transplantation (ABMT). These complications are due to the effects derived from antiblastic chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Infections occur during the period of severe marrow aplasia and may be secondary to the conditions of the oral cavity before the transplant. Patients treated for lymphoproliferative disorders are at increased risk of relapse of the primary disease so as to develop subsequent tumors both hematologic [106] and nonhematologic in this regard we consider the oral squamous cell carcinoma as a second primary solid tumor after allogeneic transplant [107].

A variety of circulating autoantibodies can be found from 20% to 61% of patients undergoing autologous bone marrow transplant [108–111], and a number of these patients may demonstrate autoantibody-mediated diseases such as myasthenia gravis and autoimmune cytopenias [112] and some cases of oral diseases, such as oral vesiculobullous (pemphigus and pemphigoid) [113–116].

The Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is a multisystem immunologic reaction resulting from the action of immunocompetent cells transplanted from a donor to an immunodeficient host [117]. The recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HTC) are at greater risk of developing the disease from acute and chronic graft versus host. The likelihood of developing GVHD depends on the type of conditioning regimen (ablative vs. totally reduced intensity regimens). GVHD in oral lesions, although infrequent, can be observed, and rarely require specific treatment. Chronic GVHD typically develops after the hundredth day, with an incidence ranging from 25% to 40% after allo-HCT [107, 117] (Figure 5). The mouth is one of the locations most commonly affected by events such as lichenoid mucositis (including ulcers), pain, odynophagia, dysgeusia, hypofunction of the salivary glands, caries decayed teeth, and rarely sclerotic processes that lead to a hypomobility and a reduction in functionality [10, 118].

Figure 5.

Oral cGVHD: ulceration of the buccal mucosa.

Supportive Therapy —

Bisphosphonates are drugs used in combination with chemotherapy in the treatment of hypercalcemia secondary to malignancy, lytic bone metastases and multiple myeloma [119–121]. Starting from 2003, an increasing number of cases that describe the correlation between osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) and administration of intravenous bisphosphonates were published in the literature [122–131] (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Bisphosphonates-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Spontaneous necrotic bone exposure.

2.7. Group 7: AIDS-Related Lymphoproliferative Disorders of the Oral Cavity

Approximately 10% of all cases of non-Hodgkin lymphomas in the United States and Europe are AIDS related [132–134]. Typically, AIDS-related NHL has a predilection for extranodal sites and appears in the head and neck, in 50-60% of cases [135–144]; they have an aggressive course and a poor prognosis [145–147]. In histopathology these lymphomas are B-cells derived and characterized by widespread growth, pleomorphism, high-grade morphology, frequent mitotic figures, and increased tendency to develop into necrosis [148–153]. Lymphomas of head and neck may involve the gingiva, palate, tongue, tonsils, nasopharynx, orbits, parotid glands, jaw breasts, soft tissues, and hypopharynx. These tumors are associated with severe immunosuppression and a poor response to chemotherapy.

3. Conclusions

Lymphoid neoplasms are heterogeneous malignant disorders of the lymphatic system characterized by uncontrolled proliferation of lymphoid cells or their precursors. With regard to the primary localizations of lymphoproliferative disorders, a careful examination of the head and neck, oral, and oropharyngeal area is necessary in order to identify suspicious lesions and their early detection. An early diagnosis may allow treatment at early stages of the disease, resulting in a better prognosis for the patient. Numerous complications have been described and frequently found at oral level, due to pathology or different therapeutic strategies. These complications require a precise diagnosis and measures to oral health care. Furthermore, the evaluation of patients after treatment for lymphoma is essential to prevent relapse and to recognize early any eventual secondary localizations.

In all this, oral pathologists, as well as dental practitioners, have a central role in the treatment and long term monitoring of these patients, having the opportunity and the duty to examine and make a diagnosis at the level of hard and soft tissue of the oral cavity.

References

- 1.Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, Isaacson PG. Classification of lymphoid neoplasms: the microscope as a tool for disease discovery. Blood. 2008;112(12):4384–4399. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-077982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouqot JE. Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology. 2nd edition. Philadelphia, Pa, USA: WB Saunders; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson T, Chabner BA, Young RC, et al. Malignant lymphoma. I. The histology and staging of 473 patients at the National Cancer Institute. Cancer. 1982;50(12):2699–2707. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19821215)50:12<2699::aid-cncr2820501202>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seymour JF, Solomon B, Wolf MM, Janusczewicz EH, Wirth A, Prince HM. Primary large-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the testis: a retrospective analysis of patterns of failure and prognostic factors. Clinical Lymphoma. 2001;2(2):109–115. doi: 10.3816/clm.2001.n.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woodman R, Shin K, Pineo G. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the brain. A review. Medicine. 1985;64(6):425–430. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198511000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeman CR, Shustik C, Brisson M-L, et al. Primary malignant lymphoma of the central nervous system. Cancer. 1986;58(5):1106–1111. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860901)58:5<1106::aid-cncr2820580521>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DePena CA, Van Tassel P, Lee Y-Y. Lymphoma of the head and neck. Radiologic Clinics of North America. 1990;28(4):723–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epstein JB, Epstein JD, Le ND, Gorsky M. Characteristics of oral and paraoral malignant lymphoma: a population-based review of 361 cases. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontics. 2001;92(5):519–525. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.116062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaugars GE, Burns JC. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the oral cavity associated with AIDS. Oral Surgery Oral Medicine and Oral Pathology. 1989;67(4):433–436. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(89)90387-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mawardi H, Cutler C, Treister N. Medical management update: non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endodontology. 2009;107(1):e19–e33. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Waal RIF, Huijgens PC, van der Valk P, van der Waal I. Characteristics of 40 primary extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphomas of the oral cavity in perspective of the new WHO classification and the International Prognostic Index. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2005;34(4):391–395. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kemp S, Gallagher G, Kabani S, Noonan V, O’Hara C. Oral non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: review of the literature and World Health Organization classification with reference to 40 cases. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endodontology. 2008;105(2):194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castoldi G, Liso V. Malattie del Sangue e Degli Organi Ematopoietici. 5th edition. Milano, Italy: McGraw-Hill; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Todd GB, Michaels L. Hodgkin’s disease involving Waldeyer’s lymphoid ring. Cancer. 1974;34(5):1769–1778. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197411)34:5<1769::aid-cncr2820340527>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinkus GS, Thomas P, Said JW. Leu-M1, a marker for Reed-Sternberg cells in Hodgkin’s disease. An immunoperoxidase study of paraffin-embedded tissues. American Journal of Pathology. 1985;119(2):244–252. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stein H, Gerdes J, Schwab U. Identification of Hodgkin and Sternberg-Reed cells as a unique cell type derived from a newly-detected small-cell population. International Journal of Cancer. 1982;30(4):445–459. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910300411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cook HP. Oral lymphomas. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology. 1961;14(6):690–704. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(61)90226-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bailey BJ, Brindley PC. Manifestations of malignant lymphomas in the head and neck. Transactions of American Academy of Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology. 1970;74(2):283–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terplan K. Über die intestinale form der lymphogranulomatose. Virchows Archiv. 1922;237(1-2):241–264. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bathard-Smith PJ, Coonar HS, Markus AF. Hodgkin’s disease presenting intra-orally. British Journal of Oral Surgery. 1978;16(1):64–69. doi: 10.1016/s0007-117x(78)80057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyer B, Roswit B, Unger SM. Hodgkin’s disease of the oral cavity. Journal of Roentgenology. 1959;81:430–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dulci G, Di Blasi F. On a case of pseudotumor of the parotid-Hodgkin’s disease localized in intraparotid lymphatic tissue. Annali di Stomatologia. 1964;13:447–455. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glińska H, Pawlicki M. Hodgkin’s disease with rare localization. Nowotwory. 1972;22(1):63–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marzetti E, Marzetti A, Palma O, Pezzuto RW. Plasmacytomas of the head and neck. Acta Otorhinolaryngologica Italica. 1996;16(1):6–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bladé J. Mieloma múltiple y gamma patía monoclonal idiopática. Diagnóstico, pronóstico y tratamiento. Medicina Clínica. 1988;90:704–714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sánchez-López JD, Martínez Plaza A, Marcos Vivas A. Mieloma solitario de presentación mandibular. Diagnóstico y tratamiento. Archivos de Odontoestomatología. 1999;15:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rollón-Mayordomo A, Manso-García F, Oliveras-Moreno JM, Restoy-Lozano A, Salazar-Fernandez C. Plasmocitoma de huesos faciales: revisión de 3casos. Revista Española de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial. 1993;15:169–175. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loh HS. A retrospective evaluation of 23 reported cases of solitary plasmacytoma of the mandible, with an additional case report. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 1984;22(3):216–224. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(84)90101-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schreiman JS, McLeod RA, Kyle RA, Beabout JW. Multiple myeloma: evaluation by CT. Radiology. 1985;154(2):483–486. doi: 10.1148/radiology.154.2.3966137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kyle RA. Multiple myeloma. Review of 869 cases. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 1975;50(1):29–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmed AR, Avram MM, Duncan LM, et al. A 79-year-old woman with gastric lymphoma and erosive mucosal and cutaneous lesions. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349:382–391. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc030016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cangiarella J, Waisman J, Cohen J-M, Chhieng D, Symmans WF, Goldenberg A. Plasmacytoma of the breast: a report of two cases diagnosed by aspiration biopsy. Acta Cytologica. 2000;44(1):91–94. doi: 10.1159/000326233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ganesh M, Sankar NS, Jagannathan R. Extramedullary plasmacytoma presenting as upper back pain. Journal of The Royal Society for the Promotion of Health. 2000;120(4):262–265. doi: 10.1177/146642400012000415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang J, Pandha HS, Treleaven J, Powles R. Metastatic extramedullary plasmacytoma of the lung. Leukemia and Lymphoma. 1999;35(3-4):423–425. doi: 10.3109/10428199909145749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gianom D, Famos M, Marugg D, Oberholzer M. Primary extramedullary plasmacytoma of the duodenum. Swiss Surgery. 1999;5(1):6–10. doi: 10.1024/1023-9332.5.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Panosian MS, Roberts JK. Plasmacytoma of the middle ear and mastoid. American Journal of Otology. 1994;15(2):264–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ceccolini E, Palmerio B, Patrone P. Extramedullary cutaneous plasmacytoma. Cutis. 1991;48(2):134–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sulzner SE, Amdur RJ, Weider DJ. Extramedullary plasmacytoma of the head and neck. American Journal of Otolaryngology. 1998;19(3):203–208. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(98)90089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Booth JB, Cheesman AD, Vincenti NH. Extramedullary plasmacytomata of the upper respiratory tract. Annals of Otology, Rhinology and Laryngology. 1973;82(5):709–715. doi: 10.1177/000348947308200515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wiltshaw E. Extramedullary plasmacytoma. British Medical Journal. 1971;2(757):p. 327. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5757.327-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liebross RH, Ha CS, Cox JD, Weber D, Delasalle K, Alexanian R. Clinical course of solitary extramedullary plasmacytoma. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 1999;52(3):245–249. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(99)00114-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fernández-Pérez A, Fernández-Sánchez A. Solitary extramedullary plasmocytoma of the nasal cavity. Acta Otorrinolaringologica Espanola. 1989;40(5):391–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bangerter M, Hildebrand A, Waidmann O, Griesshammer M. Fine needle aspiration cytology in extramedullary plasmacytoma. Acta Cytologica. 2000;44(3):287–291. doi: 10.1159/000328466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Casado-Morente JC, Povedano-Rodriguez V, Piedrola-Maroto D, Conde-Jimenez M, Jurado-Ramos A. Mediofacial degloving in extramedullary plasmacytoma with orbital invasion. Acta Otorrinolaringologica Espanola. 2000;51(1):71–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rakover Y, Bennett M, David R, Rosen G. Isolated extramedullary Med Oral 2003;8:269–80. Neoplasia células plasmáticas/Plasma cell neoplasia 280 plasmacytoma of the true vocal fold. The Journal of Laryngology & Otology. 2000;114:540–542. doi: 10.1258/0022215001906093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uceda-Montañés A, Blanco G, Saornil MA, Gonzalez C, Sarasa JL, Cuevas J. Extramedullary plasmacytoma of the orbit. Acta Ophthalmologica Scandinavica. 2000;78(5):601–603. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2000.078005601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hidaka H, Ikeda K, Oshima T, Ohtani H, Suzuki H, Takasaka T. A case of extramedullary plasmacytoma arising from the nasal septum. Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 2000;114(1):53–55. doi: 10.1258/0022215001903672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rodríguez Fernández AM, Martí Peña M, González Nuñez MA, Aparicio Pérez M, Avila García J. Solitary extramedullary plasmocytoma of the nasal fossa and paranasal sinuses. Acta Otorrinolaringologica Espanola. 1991;42(6):461–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gaffney CC, Dawes PJDK, Jackson D. Plasmacytoma of the head and neck. Clinical Radiology. 1987;38(4):385–388. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(87)80231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alhan E, Calik A, Kucuktulu U, Cinel A, Ozoran Y. Solitary extramedullary plasmocytoma of the breast with kappa monoclonal gammopathy. Pathologica. 1995;87(1):71–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ascari E, Merlini G, Riccardi A. Il mieloma multiplo. In: Atti XC Congresso della Società Italiana di Medicina Interna; 1989; pp. 263–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goldman AB. Multiple myeloma. In: Traversas JM, Ferrucci JT, editors. Radiology: Diagnosis, Imaging, Intervention. Philadelphia, Pa, USA: Lippincott JB; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Flick WG, Lawrence FR. Oral amyloidosis as initial symptom of multiple myeloma: a case report. Oral Surgery Oral Medicine and Oral Pathology. 1980;49(1):18–20. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(80)90026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lewin RW, Cataldo E. Multiple myeloma discovered from oral manifestations: report of case. Journal of Oral Surgery. 1967;25(1):68–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Henderson D, Rowe NL. Myelomatosis affecting the jaws. British Journal of Oral Surgery. 1968;6(3):161–172. doi: 10.1016/s0007-117x(68)80031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee S-H, Huang J-J, Pan W-L, Chan C-P. Gingival mass as the primary manifestation of multiple myeloma Report of two cases. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontics. 1996;82(1):75–79. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(96)80380-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Epstein JB, Voss NJS, Stevenson-Moore P. Maxillofacial manifestations of multiple myeloma. An unusual case and review of the literature. Oral Surgery Oral Medicine and Oral Pathology. 1984;57(3):267–271. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(84)90182-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Raubenheimer EJ, Dauth J, de Coning JP. Multiple myeloma presenting with extensive oral and perioral amyloidosis. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology. 1986;61(5):492–497. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(86)90393-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moss RL. Multiple myeloma with maxillary myelomatous epulis and malignant pheochromocytoma. Report of a case. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology. 1958;11(9):951–959. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(58)90134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lambertenghi-Deliliers G, Bruno E, Cortelezzi A, Fumagalli L, Morosini A. Incidence of jaw lesions in 193 patients with multiple myeloma. Oral Surgery Oral Medicine and Oral Pathology. 1988;65(5):533–537. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(88)90135-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kakagia D, Tamiolakis D, Lambropoulou M, Kakagia A, Grekou A, Papadopoulos N. Systemic B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia first presenting as a cutaneous infiltrate arising at the site of a herpes simplex scar. Minerva Stomatologica. 2005;54(3):161–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Macaulay WL. Lymphomatoid papulosis. A continuing self-healing eruption, clinically benign—histologically malignant. Archives of Dermatology. 1968;97(1):23–30. doi: 10.1001/archderm.97.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Allabert C, Estève E, Joly P, et al. Mucosal involvement in lymphomatoid papulosis: four cases. Annales de Dermatologie et de Venereologie. 2008;135(4):273–278. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2007.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gomez-De La Fuente E, Rodriguez-Peralto JL, Ortiz PL, Barrientos N, Vanaclocha F, Iglesias L. Oral involvement in mycocis fungoides: report of two cases and a literature review. Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 2000;80(4):299–301. doi: 10.1080/000155500750012234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Long JC, Mihm MC. Mycosis fungoides with extracutaneous dissemination: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1974;34(5):1745–1755. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197411)34:5<1745::aid-cncr2820340524>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Epstein EH, Jr., Levin DL, Croft JD, Jr., Lutzner MA. Mycosis fungoides. Survival, prognostic features, response to therapy, and autopsy findings. Medicine. 1972;51(1):61–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Damm DD, White DK, Cibull ML, Drummond J, Cramer JR. Mycosis fungoides: initial diagnosis via palatal biopsy with discussion of diagnostic advantages of plastic embedding. Oral Surgery Oral Medicine and Oral Pathology. 1984;58(4):413–419. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(84)90335-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kapadia SB, Desai U, Cheng VS. Extramedullary plasmacytoma of the head and neck. A clinicopathologic study of 20 cases. Medicine. 1982;61(5):317–329. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198209000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Birt BD. The management of malignant tracheal neoplasms. Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 1970;84(7):723–731. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100072443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rog RP. Beware of malignant lymphoma masquerading as facial inflammatory processes. Oral Surgery Oral Medicine and Oral Pathology. 1991;71(4):415–419. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(91)90419-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Anhalt GJ, Kim SC, Stanley JR, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus. An autoimmune mucocutaneous disease associated with neoplasia. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1990;323(25):1729–1735. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199012203232503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lane JE, Woody C, Davis LS, Guill MF, Jerath RS. Paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome (paraneoplastic pemphigus) in a child: case report and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2004;114(4):e513–e516. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nousari HC, Deterding R, Wojtczack H, et al. The mechanism of respiratory failure in paraneoplastic pemphigus. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;340(18):1406–1410. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905063401805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang J, Zhu X, Li R, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus associated with castleman tumor: a commonly reported subtype of paraneoplastic pemphigus in China. Archives of Dermatology. 2005;141(10):1285–1293. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.10.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nguyen VT, Ndoye A, Bassler KD, et al. Classification, clinical manifestations, and immunopathological mechanisms of the epithelial variant of paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome: a reappraisal of paraneoplastic pemphigus. Archives of Dermatology. 2001;137(2):193–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Healy CM, Tobin A-M, Kirby B, Flint SR. Oral lesions as an initial manifestation of dermatomyositis with occult malignancy. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endodontology. 2006;101(2):184–187. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Seno A, Tokuda M, Yamasaki H, Akiyama K. A case of amyopathic dermatomyositis presenting blister and oral ulcer. Ryumachi. 1999;39(6):836–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Agbo-Godeau S, Bertrand JC. Lip ulceration in paraneoplastic dermatomyositis. Apropos of a case. Review of the literature. Revue de Stomatologie et de Chirurgie Maxillo-Faciale. 1993;94(5):287–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Callen JP. The value of malignancy evaluation in patients with dermatomyositis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1982;6(2):253–259. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(82)70018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bowden JR, Scully C, Eveson JW, Flint S, Harman RRM, Jones SK. Multiple myeloma and bullous lichenoid lesions: an unusual association. Oral Surgery Oral Medicine and Oral Pathology. 1990;70(5):587–589. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(90)90404-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Camisa C, Helm TN, Liu Y-C, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus: a report of three cases including one long-term survivor. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1992;27(4):547–553. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70220-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stevens SR, Griffiths CEM, Anhalt GJ, Cooper KD. Paraneoplastic pemphigus presenting as a lichen planus pemphigoides-like eruption. Archives of Dermatology. 1993;129(7):866–869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Egan CA, Lazarova Z, Darling TN, Yee C, Yancey KB. Anti-epiligrin cicatricial pemphigoid clinical findings, immunopothogenesis, and significant associations. Medicine. 2003;82(3):177–186. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000076003.64510.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ostlere LS, Branfoot AC, Staughton RCD. Cicatricial pemphigoid and carcinoma of the pancreas. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 1992;17(1):67–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1992.tb02541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Uchiyama K, Yamamoto Y, Taniuchi K, Matsui C, Fushida Y, Shirao Y. Remission of antiepiligrin (laminin-5) cicatricial pemphigoid after excision of gastric carcinoma. Cornea. 2000;19(4):564–566. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200007000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sivalingam V, Shields CL, Shields JA, Pearah JD. Squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva associated with benign mucous membrane pemphigoid. Annals of Ophthalmology. 1990;22(3):106–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bystryn J-C, Hodak E, Gao S-Q, Chuba JV, Amorosi EL. A paraneoplastic mixed bullous skin disease associated with anti-skin antibodies and a B-cell lymphoma. Archives of Dermatology. 1993;129(7):870–875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Seth RK, Su GW, Pflugfelder SC. Mucous membrane pemphigoid in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cornea. 2004;23(7):740–743. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000126437.33375.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cuni LJ, Grüenwald H, Rosner F. Bullous pemphigoid in chronic lymphocytic leukemia with the demonstration of antibasement membrane antibodies. American Journal of Medicine. 1974;57(6):987–992. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(74)90179-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Goodnough LT, Muir WA. Bullous pemphigoid as a manifestation of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1980;140(11):1526–1527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Misery L, Cambazard F, Rimokh R, et al. Bullous pemphigoid associated with chronic B-cell lymphatic ieukaemia: the anti-230-kDa autoantibody is not synthesized by leukaemic cells. British Journal of Dermatology. 1999;141(1):155–157. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Parra CA, López González G, Pizzi de Parra N. Bullous pemphigoid and lymphoblastic lymphoma. Medicina Cutanea Ibero-Latino-Americana. 1979;7(1–3):51–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jones AC, Gulley ML, Freedman PD. Necrotizing ulcerative stomatitis in human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive individuals: a review of the histopathologic, immunohistochemical, and virologic characteristics of 18 cases. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontics. 2000;89(3):323–332. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(00)70097-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Eisele DW, Inglis AF, Jr., Richardson MA. Noma and noma neonatorum. Ear, Nose and Throat Journal. 1990;69(2):119–120, 122–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.El Baze P, Thyss A, Vinti H, Deville A, Dellamonica P, Ortonne J-P. A study of nineteen immunocompromised patients with extensive skin lesions caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa with and without bacteremia. Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 1991;71(5):411–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Patton LL, McKaig R. Rapid progression of bone loss in HIV-associated necrotizing ulcerative stomatitis. Journal of Periodontology. 1998;69(6):710–716. doi: 10.1902/jop.1998.69.6.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Brennan MT, Runyon MS, Batts JJ, et al. Odontogenic infection: odontogenic signs and symptoms as predictors of odontogenic infection—a clinical trial. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2006;137(1):62–66. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Flynn TR, Shanti RM, Hayes C. Severe odontogenic infections, part 2: prospective outcomes study. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2006;64(7):1104–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Finlay PM, Richardson MD, Robertson AG. A comparative study of the efficacy of fluconazole and amphotericin B in the treatment of oropharyngeal candidosis in patients undergoing radiotherapy for head and neck tumours. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 1996;34(1):23–25. doi: 10.1016/s0266-4356(96)90130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Epstein JB, Gorsky M, Hancock P, Peters N, Sherlock CH. The prevalence of herpes simplex virus shedding and infection in the oral cavity of seropositive patients undergoing head and neck radiation therapy. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontics. 2002;94(6):712–716. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.127585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Davies AN, Broadley K, Beighton D. Salivary gland hypofunction in patients with advanced cancer. Oral Oncology. 2002;38(7):680–685. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(01)00133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Böhme A, Karthaus M. Systemic fungal infections in patients with hematologic malignancies: indications and limitations of the antifungal armamentarium. Chemotherapy. 1999;45(5):315–324. doi: 10.1159/000007222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Boeckh M, Kim HW, Flowers MED, Meyers JD, Bowden RA. Long-term acyclovir for prevention of varicella zoster virus disease after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation—a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Blood. 2006;107(5):1800–1805. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lerman MA, Laudenbach J, Marty FM, Baden LR, Treister NS. Management of oral infections in cancer patients. Dental Clinics of North America. 2008;52(1):129–153. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Epstein JB, Sherlock CH, Greenspan JS. Hairy leukoplakia-like lesions following bone-marrow transplantation. AIDS. 1991;5(1):101–102. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199101000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bassal M, Mertens AC, Taylor L, et al. Risk of selected subsequent carcinomas in survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(3):476–483. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.7235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Demarosi F, Bez C, Sardella A, Lodi G, Carassi A. Oral involvement in chronic graft-vs-host disease following allogenic bone marrow transplantation. Archives of Dermatology. 2002;138(6):842–843. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.6.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lister J, Messner H, Keystone E, Miller R, Fritzler MJ. Autoantibody analysis of patients with graft versus host disease. Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Immunology. 1987;24(1):19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Rouquette-Gally AM, Boyeldieu D, Prost AC, Gluckman E. Autoimmunity after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. A study of 53 long-term surviving patients. Transplantation. 1988;46(2):238–240. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198808000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Smith CIE, Hammarström L, Lefvert A-K. Bone-marrow grafting induces acetylcholine receptor antibody formation. The Lancet. 1985;1(8435):p. 978. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)91742-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Smith CIE, Norberg R, Möller G, Lönnqvist B, Hammarström L. Autoantibody formation after bone marrow transplantation. Comparison between acetylcholine receptor antibodies and other autoantibodies and analysis of HLA and Gm markers. European Neurology. 1989;29(3):128–134. doi: 10.1159/000116395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sherer Y, Shoenfeld Y. Autoimmune diseases and autoimmunity post-bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 1998;22(9):873–881. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Herr AL, Hatami A, Kokta V, Dalle JH, Champagne MA, Duval M. Successful anti-CD20 antibody treatment of pemphigus foliaceus after unrelated cord blood transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2005;35(4):427–428. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Szabolcs P, Reese M, Yancey KB, Hall RP, Kurtzberg J. Combination treatment of bullous pemphigoid with anti-CD20 and anti-CD25 antibodies in a patient with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2002;30(5):327–329. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Delbaldo C, Rieckhoff-Cantoni L, Helg C, Saurat J-H. Bullous pemphigoid associated with acute graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 1992;10(4):377–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Burger J, Gmür J, Bruckner-Tuderman L. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, a rare late complication of allogeneic bone marrow transplantation? Bone Marrow Transplantation. 1992;9(2):139–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Eggleston TI, Ziccardi VB, Lumerman H. Graft-versus-host disease: case report and discussion. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontics. 1998;86(6):692–696. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90206-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Schubert MM, Correa MEP. Oral graft-versus-host disease. Dental Clinics of North America. 2008;52(1):79–109. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Dhillon S, Lyseng-Williamson KA. Zoledronic acid: a review of its use in the management of bone metastases of malignancy. Drugs. 2008;68(4):507–534. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200868040-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Lipton A. Treatment of bone metastases and bone pain with bisphosphonates. Supportive Cancer Therapy. 2007;4(2):92–100. doi: 10.3816/SCT.2007.n.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Saad F, Gleason DM, Murray R, et al. Long-term efficacy of zoledronic acid for the prevention of skeletal complications in patients with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2004;96(11):879–882. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Marx RE. Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: a growing epidemic. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2003;61(9):1115–1117. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(03)00720-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Biasotto M, Chiandussi S, Dore F, et al. Clinical aspects and management of bisphosphonates-associated osteonecrosis of the jaws. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica. 2006;64(6):348–354. doi: 10.1080/00016350600844360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Coleman RE. Risks and benefits of bisphosphonates. British Journal of Cancer. 2008;98(11):1736–1740. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Adamo V, Caristi N, Saccà MM, et al. Current knowledge and future directions on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer patients. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 2008;9(8):1351–1361. doi: 10.1517/14656566.9.8.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Sambrook PN, Ebeling P. Osteonecrosis of the jaw. Current Rheumatology Reports. 2008;10(2):97–101. doi: 10.1007/s11926-008-0018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Pendrys DG, Silverman SL. Osteonecrosis of the jaws and bisphosphonates. Current Osteoporosis Reports. 2008;6(1):31–38. doi: 10.1007/s11914-008-0006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Watts NB, Marciani RD. Osteonecrosis of the jaw. Southern Medical Journal. 2008;101(2):160–165. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31816127d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Woo S-B, Kalmar JR. Osteonecrosis of the jaws and bisphosphonates. Alpha Omegan. 2007;100(4):194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.aodf.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Ruggiero SL, Woo S-B. Biophosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. Dental Clinics of North America. 2008;52(1):111–128. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Sawatari Y, Marx RE. Bisphosphonates and bisphosphonate induced osteonecrosis. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America. 2007;19(4):487–498. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Dal Maso L, Serraino D, Franceschi S. Epidemiology of AIDS-related tumours in developed and developing countries. European Journal of Cancer. 2001;37(10):1188–1201. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00120-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Rabkin CS. AIDS and cancer in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) European Journal of Cancer. 2001;37(10):1316–1319. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Biggar RJ, Frisch M, Goedert JJ. Risk of cancer in children with AIDS. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284(2):205–209. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Jordan RCK, Chong L, DiPierdomenico S, Satira F, Main JHP. Oral lymphoma in HIV infection. Oral Diseases. 1997;3(supplement 1):S135–S137. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.1997.tb00346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Franceschi S, Dal Maso LD, La Vecchia CL. Advances in the epidemiology of HIV-associated non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and other lymphoid neoplasms. International Journal of Cancer. 1999;83(4):481–485. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19991112)83:4<481::aid-ijc8>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Singh B, Poluri A, Shaha AR, Michuart P, Har-El G, Lucente FE. Head and neck manifestations of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. American Journal of Otolaryngology. 2000;21(1):10–13. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(00)80118-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Coté TR, Biggar RJ, Rosenberg PS, et al. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma among people with aids: incidence, presentation and public health burden. International Journal of Cancer. 1997;73(5):645–650. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19971127)73:5<645::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Levine AM, Seneviratne L, Espina BM, et al. Evolving characteristics of AIDS-related lymphoma. Blood. 2000;96(13):4084–4090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Carbone A, Gloghini A, Larocca LM, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated Hodgkin’s disease derives from post-germinal center B cells. Blood. 1999;93(7):2319–2326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Carbone A, Gaidano G, Gloghini A, Ferlito A, Rinaldo A, Stein H. Aids-related plasmablastic lymphomas of the oral cavity and jaws: a diagnostic dilemma. Annals of Otology, Rhinology and Laryngology. 1999;108(1):95–99. doi: 10.1177/000348949910800115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Delecluse HJ, Anagnostopoulos I, Dallenbach F, et al. Plasmablastic lymphomas of the oral cavity: a new entity associated with the human immunodeficiency virus infection. Blood. 1997;89(4):1413–1420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Delecluse HJ, Anagnostopoulos I, Dallenbach F, et al. Plasmablastic lymphomas of the oral cavity: a new entity associated with the human immunodeficiency virus infection. Blood. 1997;89(4):1413–1420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Brown RSD, Campbell C, Lishman SC, Spittle MF, Miller RF. Plasmablastic lymphoma: a new subcategory of human immunodeficiency virus-related non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Clinical Oncology. 1998;10(5):327–329. doi: 10.1016/s0936-6555(98)80089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Levine AM, Seneviratne L, Espina BM, et al. Evolving characteristics of AIDS-related lymphoma. Blood. 2000;96(13):4084–4090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Levine AM. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related lymphoma: clinical aspects. Seminars in Oncology. 2000;27(4):442–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Human Immunodeficiency Viruses and Human T-Cell Lymphotropich Viruses, Vol. 67. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research ok Cancer/ World Health Organization; 1996. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Knowles DM, Chamulak GA, Subar M, et al. Lymphoid neoplasia associated with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS): The New York University Medical Center Experience with 105 patients (1981–1986) Annals of Internal Medicine. 1988;108(5):744–753. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-108-5-744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Knowles DM. Immunodeficiency-associated lymphoproliferative disorders. Modern Pathology. 1999;12(2):200–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Carbone A, Gloghini A. AIDS-related lymphomas: from pathogenesis to pathology. British Journal of Haematology. 2005;130(5):662–670. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Carbone A, Gloghini A, Canzonieri V, Tirelli U, Gaidano G. AIDS-related extranodal non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas with plasma cell differentiation. Blood. 1997;90(3):1337–1338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Carbone A, Tirelli U, Gloghini A, et al. The pathologic spectrum of AIDS-related non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. In: Abraham NG, Tabillo A, Martelli M, et al., editors. Molecular Biology of Hematopoiesis. 6th edition. New York, NY, USA: Plenum Press; 1999. pp. 191–202. [Google Scholar]

- 153.Carbone A. Emerging pathways in the development of AIDS-related lymphomas. Lancet Oncology. 2003;4(1):22–29. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(03)00957-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]