Abstract

Objective

Exposure to tobacco smoke substantially increases arterial atherothrombotic events and venous thrombosis. Smokers exhibit higher circulating levels of tissue factor (TF) than do non-smokers, but the underlying mechanisms have not been reported. Because TF released from cells into plasma is always carried by membrane microvesicles (MVs, also called microparticles), we now investigated whether exposure of human monocyte/macrophages to tobacco smoke induces their release of MVs and whether these MVs are procoagulant.

Methods and Results

We found that exposure of human THP-1 monocytes and primary human monocyte-derived macrophages (hMDMs) to tobacco smoke extract (TSE, 3.75%) significantly increased their total and TF-positive MV generation. Importantly, MVs released from TSE-treated human monocyte/macrophages exhibited three-to-four times the procoagulant activity (PCA) of control MVs, as assessed by TF-dependent generation of factor Xa. Exposure to TSE increased TF mRNA and protein expression and cell-surface TF display by both THP-1 monocytes and primary hMDMs. In addition, TSE exposure caused activation of JNK, p38, and ERK MAP kinases, as well as apoptosis, a major mechanism for MV generation. Treatment of THP-1 cells with inhibitors of ERK, MEK, Ras, or caspase 3, but not p38 or JNK, significantly blunted TSE-induced apoptosis and MV generation. Surprisingly, neither ERK nor caspase 3 inhibition altered the induction of cell-surface TF display by TSE, indicating an effect solely on MV release. Of note, inhibition of ERK or caspase 3 essentially abolished TSE-induced generation of procoagulant MVs from THP-1 monocytes.

Conclusions

Tobacco smoke exposure of human monocyte/macrophages induces cell-surface TF display, apoptosis, and ERK- and caspase 3-dependent generation of biologically active, procoagulant MVs. These processes may be novel contributors to the pathologic hypercoagulability of active and second-hand smokers.

Introduction

As of 2002, an estimated 1.3 billion (1.3 × 109) people in the world actively smoked cigarettes, and even more individuals are exposed to second-hand tobacco smoke.1, 2 Tobacco smoke substantially increases the risk of atherothrombotic disease in coronary, cerebral, and peripheral arteries,1, 3–8 as well as venous thrombosis.9–11 Public smoking bans are associated with rapid, significant reductions in atherothrombotic cardiovascular events,3, 12 and this beneficial effect promptly disappeared in one municipality when it lifted its ban.13 Moreover, much of the decline in cardiovascular events in America and Europe during the past two-to-three decades has been attributed to management of the major conventional cardiovascular risk factors, including reductions in cigarette smoking.12, 14, 15

Despite its wide importance, the underlying pathologic mechanisms for cardiovascular harm from tobacco smoke remain poorly understood.3 Here, we focused on microvesicles (MVs, also called microparticles), which are released from the plasma membrane during cell activation or apoptosis and have been shown to play an important role in thrombus formation.16–20 MVs transport tissue factor (TF), a transmembrane molecule that initiates coagulation in vivo.16–20 Several studies have shown that cigarette smoking increases TF expression on peripheral monocytes,21 by cultured mouse alveolar macrophages,22 and in atherosclerotic lesions.23 Smokers have higher plasma concentrations of TF than do non-smokers, and smoking just two cigarettes in a row increases their TF levels even further.24 Nevertheless, we are aware of no prior reports characterizing cellular mechanisms for increased plasma TF in smokers. In the current study, we sought to determine whether exposure of human monocyte/macrophages to tobacco smoke induces the release of MVs, and if so, whether these smoke-induced MVs are procoagulant and what cellular processes might be responsible for their production.

Materials and Methods

The human THP-1 monocytic cell line (ATCC, Manassas, VA) was maintained in RPMI-1640 with 10% FBS. Primary human monocyte-derived macrophages (hMDMs) were prepared from fresh Buffy coats by selecting monocytes by adherence followed by differentiation into macrophages.20 Tobacco smoke extract (TSE) was prepared as previously described.25, 26 At the beginning of each experiment, THP-1 monocytes or hMDMs were transferred to serum-free RPMI/BSA supplemented with different concentrations of TSE, ranging from 0% (control) to 3.75% (v:v), and then incubated at 37°C for 2–20h (0h denotes harvest immediately before adding TSE). In time-course studies of kinase activation, cells were placed into serum-free medium simultaneously; TSE was added at different times; and then all cells were harvested simultaneously. In experiments using kinase or caspase 3 inhibitors, the compounds were added to cells 1h before the addition of TSE and remained until the end of the experiment, at concentrations of 10 μM SP600125, 10 μM SB202190, 10 μM U0126, 20 μM PD98059, 20 μM FTI, and 100 μM Z-DEVD-FMK. Flow cytometric characterization of microvesicles and cells were performed according to our published protocols.20 Additional experimental details are provided in the Supplementary Materials (available online at https://atvb.ahajournals.org).

Results

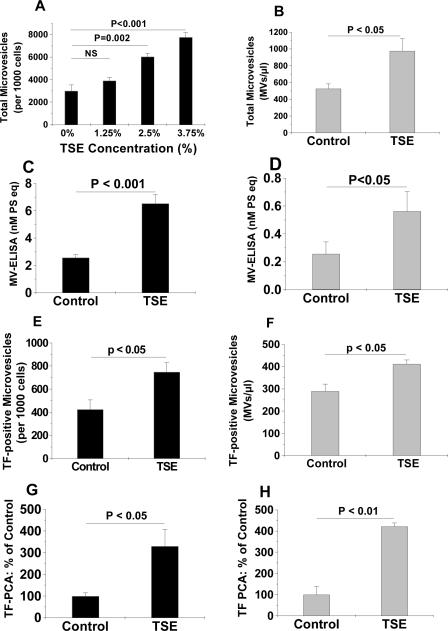

We found that exposure of human THP-1 monocytes to TSE significantly increased total MV release, in a dose- (Fig. 1A) and time- (Suppl. Fig. I) dependent manner. Smoke-induced MV release was confirmed by two independent assay methods (Fig. 1A, 1C). Likewise, TSE significantly stimulated total MV generation from primary hMDMs (Fig. 1B, 1D). In addition, the numbers of TF-positive MVs released from TSE-treated human THP-1 cells (Fig. 1E) and hMDMs (Fig. 1F) were significantly higher than those from control cells incubated without TSE. Importantly, we found that TSE treatment of THP-1 cells (Fig. 1G) or hMDMs (Fig. 1H) for 20h tripled the procoagulant activity (PCA) of their MVs.

Figure 1. TSE increases the generation of total, TF-positive, and procoagulant microvesicles from human monocytes and primary human monocyte-derived macrophages.

Exposure of human THP-1 monocytes (Panels A,C) or primary hMDMs (Panels B,D) to TSE for 20h significantly increased total MV generation. Panel A shows a dose-dependent response; panel B used a fixed concentration of TSE (3.75%); MVs in panels A and B were quantified by flow cytometry. Panels C and D show TSE (3.75%)-induced generation of MVs, as measured by ELISA. Panels E and F show concentrations of TF-positive MVs released from control and TSE-treated THP-1 cells (E) or hMDMs (F). Panels G and H show the procoagulant activities of MVs isolated from culture supernatants of THP-1 monocytes (G) and hMDMs (H) after 20h of exposure to control medium or medium supplemented with 3.75% TSE, as indicated. Displayed are means±SEMs, n=4–6. In Panel A, P< 0.001 by ANOVA; displayed are significance levels for individual pairwise comparisons by the SNK test (NS, not significant). In Panels B–H, the displayed P-values were computed using Student's t-test.

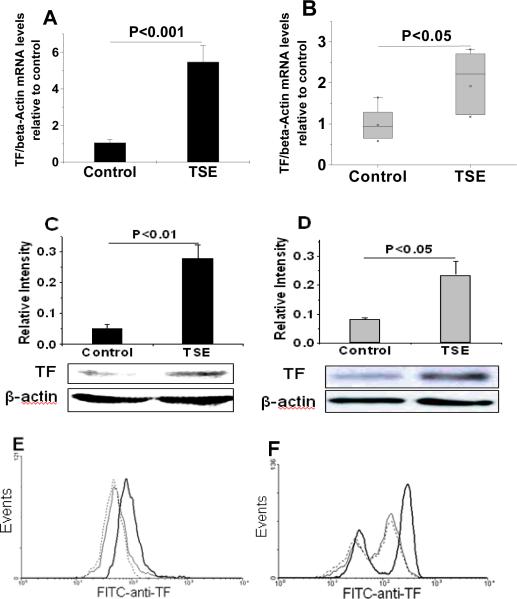

Because MVs are released from the plasma membrane, we next examined whether tobacco smoke affects expression and cell-surface display of TF on human THP-1 monocytes and hMDMs. We found that exposure to TSE (3.75%) for 2h increased TF mRNA levels in both THP-1 cells (Fig. 2A) and primary hMDMs (Fig. 2B) measured by real-time quantitative PCR. Exposure of THP-1 cells and hMDMs to TSE for 6h substantially increased their content of TF protein (Fig. 2C, 2D) and stimulated cell-surface TF display (Fig. 2E, 2F). In a time course, display of TF on the surface of THP-1 cells peaked at 6h after addition of TSE and was still elevated at 20h, compared to baseline (Suppl. Fig II). The decline from 6h to 20h may reflect, in part, the release of cellular TF into the medium on MVs.

Figure 2. Exposure of human monocyte/macrophages to TSE induces TF mRNA, protein, and cell-surface display.

Panels A and B show levels of TF mRNA, measured by real-time quantitative PCR, in THP-1 cells (A) and hMDMs (B) after a 2-h exposure to control medium or 3.75% TSE. Panels C and D show quantifications and representative immunoblots of total TF content of THP-1 cells (C) and hMDMs (D) after a 6-h exposure to control medium or 3.75% TSE as indicated. Panels E and F show flow cytometric histograms of cell-surface TF display by THP-1 cells (E) and hMDMs (F) after a 6-h incubation in control media (dashed lines) or 3.75% TSE (heavy black lines). Cells that were treated with 3.75% TSE for 6h but stained with an isotype control antibody are shown as thin black lines (E, F). The experiments in each of the panels were repeated at least three times, and the column graphs display means±SEMs (A, C, D) or medians in box-and-whisker plots (B). In Panels A–D, the displayed P-values were computed using Student's t-test. The Mann-Whitney rank-sum test was used for Panel B.

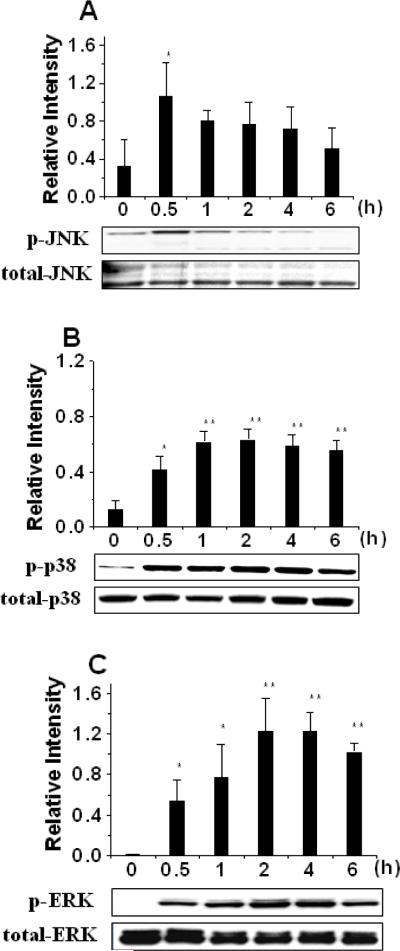

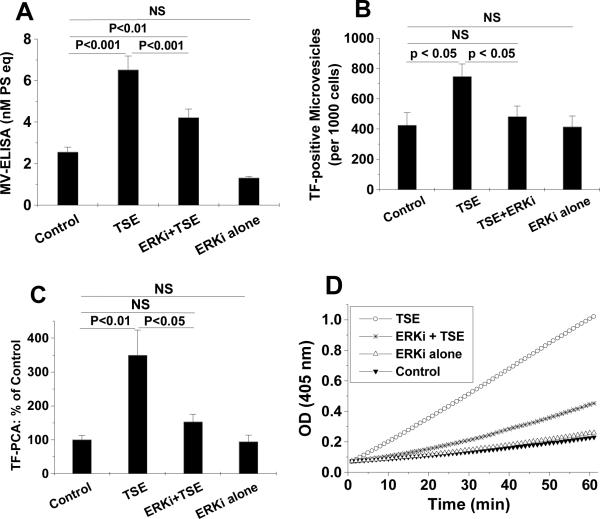

Tobacco smoke has been reported to activate a number of intracellular signaling pathways,27–33 but their roles in smoke-induced MV generation are unknown. Consistent with prior literature in other cell types,27, 34, 35 we found that exposure of THP-1 monocytes to TSE increased phosphorylation of three major MAP kinases, i.e., JNK, p38 and ERK (Fig. 3). The time courses differed considerably: phospho-JNK was increased at 0.5h, but returned to nearly its baseline level after 1–6h of TSE exposure (Fig. 3A). In contrast, phospho-p38 and phospho-ERK were partially induced at 0.5h, peaked at 2–4h, and the increase lasted throughout the entire 6-h period of TSE exposure (Fig. 3B, 3C). We then sought to determine which, if any, of these activated MAP kinases might be involved in TSE-induced generation of biologically active MVs. Inhibitors of ERK or its upstream molecules MEK and Ras significantly decreased total MV generation from TSE-exposed THP-1 cells, in some cases to levels statistically indistinguishable from control, as measured by flow cytometry (Suppl Fig. III) or ELISA (Fig. 4A). Inhibitors of JNK or p38, however, did not affect TSE-induced MV generation, and none of the above-mentioned inhibitors significantly affected MV generation in the absence of TSE (Fig. 4A for the ERK inhibitor, not shown for the rest). Surprisingly, treatment of THP-1 cells with the ERK inhibitor did not significantly affect TSE-induced display of TF on the cell surface (Suppl Fig. IV), yet ERK inhibition decreased TSE-induced generation of TF-positive MVs to a level indistinguishable from control, implying an effect solely on MV release (Fig. 4B). Most importantly, ERK inhibition essentially blocked the ability of TSE to stimulate the release of procoagulant MVs from THP-1 monocytes (Fig. 4C, 4D). Thus, TSE activates the ERK MAPK pathway, and this activation is crucial for the generation of procoagulant MVs.

Figure 3. Exposure of THP-1 monocytes to TSE activates MAP kinases.

Displayed are quantifications and representative immunoblots of phosphorylated and total JNK (panel A), p38 (panel B) and ERK (panel C) after the indicated periods of exposure of human THP-1 cells to 3.75% TSE. All cells were harvested simultaneously; TSE was added at the indicated times before harvest. Quantifications in the column graphs indicate the ratios of band intensities of phosphorylated to total forms, averaged from three independent experiments. In each Panel, P< 0.001 by ANOVA; *p<0.05 and **p<0.01 compared to values at 0h by the SNK test.

Figure 4. Inhibition of ERK blocks TSE-induced generation of total, TF-positive, and procoagulant microvesicles.

Treatment of THP-1 monocytes with the ERK inhibitor U0126 (ERKi) substantially inhibited the ability of TSE (3.75%) to induce the generation of total MVs, as measured by ELISA (Panel A). The ERK inhibitor blocked TSE-induced generation of TF-positve MVs, assessed by flow cytometry (Panel B), and essentially abolished the TSE-induced increase in procoagulant activity (PCA) of purified MVs (Panels C and D). The PCA results in panel C are from 3–5 independent experiments. Panel D shows representative kinetic curves of TF-dependent factor Xa generation by isolated MVs in vitro, indicating that our measurements were taken without saturation of the assay. P< 0.01 by ANOVA for panels A–C, and individual pairwise comparisons by SNK are displayed.

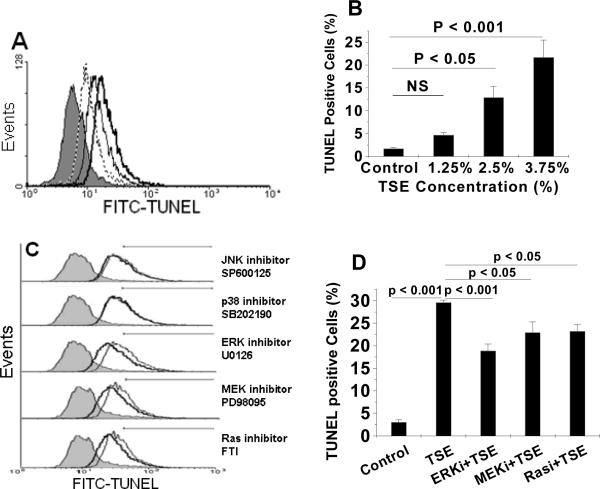

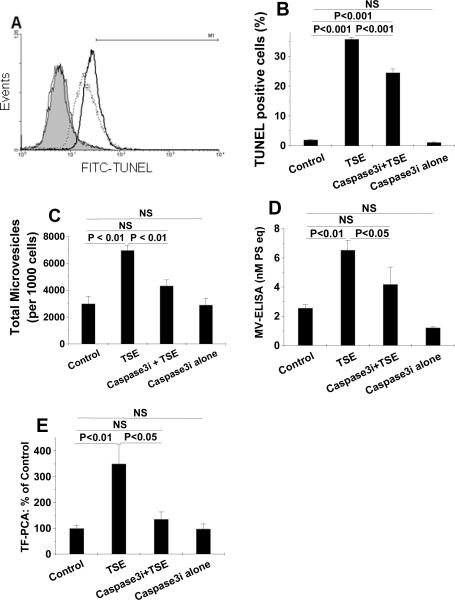

We next examined the role of programmed cell death in the production of procoagulant MVs after TSE exposure. Consistent with prior literature in other cell types,36–39 TSE exposure of THP-1 monocytes caused cell-surface exposure of phosphatidylserine (PS) (Suppl Fig. V-A, V-B) and dose-dependent DNA fragmentation detected by TUNEL staining (Fig. 5A, 5B). Likewise, exposure of human primary hMDMs to 3.75% TSE also substantially increased apoptosis, as determined by TUNEL staining (Suppl Fig. V-C, V-D). Inhibition of ERK, MEK, or Ras, but not JNK or p38, partially decreased TSE-induced apoptosis, as assessed by TUNEL staining (Fig. 5C, 5D; none of these inhibitors affected TUNEL staining of THP-1 cells in the absence of TSE, not shown). Finally, the caspase 3 inhibitor, Z-DEVD-FMK, substantially inhibited TSE-induced apoptosis (Fig. 6A, 6B) and decreased TSE-induced generation of total MVs measured by flow cytometry (Fig. 6C) and by MV-ELISA (Fig. 6D). Like the ERK inhibitor, Z-DEVD-FMK did not affect TSE-induced TF display on the cell surface (not shown), but decreased TSE-induced procoagulant activity of the purified MVs released from THP-1 cells essentially to baseline (Fig. 6E).

Figure 5. Tobacco smoke exposure induces apoptosis and MV generation in part through the Ras-MEK-ERK pathway.

Panel A shows a representative histogram from flow cytometry of TUNEL staining of THP-1 monocytes after exposure to control medium (0% TSE, filled grey curve), or medium supplemented with 1.25% (dotted line), 2.5% (thin black line), or 3.75% (heavy black line) TSE for 20h. Panel B displays quantification of TUNEL-positive THP-1 cells by flow cytometry after exposure to the indicated concentrations of TSE. Panel C shows representative histograms of TUNEL staining of THP-1 monocytes after exposure to control medium (0% TSE, filled grey curve), or medium supplemented with 3.75% TSE without (thin black line) or with indicated inhibitors (heavy black line) for 20h; note that the x-axis scale is logarithmic. The horizontal lines indicate intensities considered to be TUNEL-positive for quantification in Panel D. Panels B and D indicate quantifications of TUNEL-positive cells from 3–4 independent experiments; P<0.001 by ANOVA for both panels B and D; displayed are individual pairwise comparisons by SNK.

Figure 6. Apoptosis is required for TSE-induced MV generation by human THP-1 monocytes.

Panel A shows representative histograms of TUNEL staining of THP-1 cells after exposure to 0% TSE (control, filled grey curve), or 3.75% TSE without (heavy black line) or with (dashed line) caspase 3 inhibition by Z-DEVD-FMK (Caspase3i). As an additional control, the thin black line shows TUNEL staining cells after treatment with Caspase3i without TSE. The horizontal line (M1) indicates intensities considered to be TUNEL-positive for quantification in Panel B. Panel B displays quantifications of TUNEL-positive THP-1 cells after exposure to the indicated agents. Panels C and D show total MV generation from THP-1 cells, measured by flow cytometry (C) or ELISA (D), after exposure to control medium (Control), 3.75% TSE, and/or the Caspase3i, as indicated. Panel E shows the procoagulant activity of isolated MVs released by THP-1 cells after exposure to control medium (Control), 3.75% TSE, and/or the Caspase3i, as indicated. In panels B–E, results from 3–6 independent experiments are shown; P< 0.01 by ANOVA for each of those panels; and the individual pairwise comparisons were performed by SNK. In all panels, TSE exposure lasted 20h and treatment with Caspase3i began 1h before the addition of TSE and remained until the end of the study.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that exposure of human monocytes and primary human macrophages to tobacco smoke provokes the generation of highly procoagulant membrane MVs, in a process requiring ERK activation and apoptosis. These cellular mechanisms may contribute to the link in clinical and population studies between tobacco smoke exposure – both active and second-hand – and a high risk of thrombotic events.3, 21, 23, 24, 40–42 Our results may also help explain why acute cigarette smoking increases plasma TF concentrations in current smokers and why active smokers have higher levels of circulating TF than non-smokers.24 Consistent with this model, exposure of healthy non-smokers to second-hand smoke was recently reported to increase circulating concentrations of MVs, although their potential pro-thrombotic effects were not evaluated.43 Additional studies reported that exposure of experimental animals to tobacco smoke induces apoptosis of several different cell types,36–39 which we infer should increase their production of MVs. Thus, our current findings are likely to be relevant in vivo.

Regarding intracellular signaling pathways, we found that TSE exposure caused transient activation of JNK, and sustained activation of p38 and ERK (Fig. 3), but only ERK appeared to be involved in TSE-induced apoptosis and MV generation. ERK MAP kinases are known for their involvement in cell survival,44, 45 but recent evidence suggests that ERK activation can also contribute to cell death under certain conditions.44, 45 For example, the Ras/MEK/ERK pathway was reported to play a key role in apoptosis induced by UVA irradiation46 or a calcium ionophore.44 Based on our results, TSE induces TF expression and cell-surface display (Fig. 2) through a process independent of ERK or caspase 3 (Results). In other circumstances, TF expression is regulated47, 48 or not49 through ERK activation. Our TSE-exposed cells then underwent apoptosis and extensive apoptotic vesiculation, which depend on ERK and caspase 3 and lead to the release of biologically active TF on highly procoagulant MVs (Fig. 1, 4, 6). Additionally, the presence of PS on the MV surface is a key identifying characteristic during flow cytometry and ELISA analyses, and this unique surface phospholipid promotes the catalytic efficiency of complexes in the blood coagulation cascade,19, 20, 50 especially for apoptotic MVs.20, 51–53

The relative importance of TSE-induced TF released on MVs or remaining on cells may depend on the context. For example, biologically active TF transported by monocyte-derived MVs can become targeted into developing thrombi via the interaction of PSGL1 on the MV surface with P-selectin displayed by newly activated platelets.17 In contrast, the direct recruitment of intact monocytes or macrophages into early experimental clots appears to be minimal.54, 55 In a pathophysiologic setting, atherosclerotic plaques contain MV-associated TF56 and cell-associated TF,23, 57 both of which we presume would increase in smokers23, 24 and thereby contribute to thrombus formation and acute vessel occlusion upon plaque rupture.

Overall, our findings indicate that exposure of human monocyte/macrophages to tobacco smoke induces cell-surface TF display, apoptosis, and ERK- and caspase 3-dependent generation of biologically active, procoagulant MVs. These processes may be novel contributors to pathologic hypercoagulability caused by active and second-hand exposure to tobacco smoke.

Condensed abstract.

Tobacco smoke exposure substantially increases the risk of arterial atherothrombotic events and venous thrombosis, but the underlying pathologic mechanisms remain poorly understood. In the current study, we found that exposure of human monocyte/macrophage to tobacco smoke extract (TSE) substantially induces the generation of biologically active, procoagulant microvesicles in a process requiring ERK activation and apoptosis. These microvesicles could be novel contributors to the pathologic hypercoagulability caused by active and second-hand exposure to tobacco smoke.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

A preliminary report of this work was presented at the AHA Scientific Sessions – 2008 (Circulation 2008;118 [Suppl. 2]:S478). The authors thank Dr. Elias G. Argyris for generously providing primary hMDMs.

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by American Heart Association (AHA)-Great Rivers Affiliate Beginning Grant-In-Aid (to MLL), Temple University Department of Medicine Career Development Award (to MLL), and NIH-HL73898 (to KJW).

Footnotes

Disclosure: None

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Barnoya J, Glantz SA. Cardiovascular effects of secondhand smoke: nearly as large as smoking. Circulation. 2005;111:2684–2698. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.492215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang G, Kong L, Zhao W, Wan X, Zhai Y, Chen LC, Koplan JP. Emergence of chronic non-communicable diseases in China. Lancet. 2008;372:1697–1705. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61366-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ambrose JA, Barua RS. The pathophysiology of cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease: an update. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1731–1737. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhatnagar A. Cardiovascular pathophysiology of environmental pollutants. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H479–485. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00817.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhatnagar A. Environmental cardiology: studying mechanistic links between pollution and heart disease. Cir Res. 2006;99:692–705. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000243586.99701.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ezzati M, Henley SJ, Thun MJ, Lopez AD. Role of smoking in global and regional cardiovascular mortality. Circulation. 2005;112:489–497. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.521708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teo KK, Ounpuu S, Hawken S, Pandey MR, Valentin V, Hunt D, Diaz R, Rashed W, Freeman R, Jiang L, Zhang X, Yusuf S. Tobacco use and risk of myocardial infarction in 52 countries in the INTERHEART study: a case-control study. Lancet. 2006;368:647–658. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69249-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He Y, Lam TH, Jiang B, Wang J, Sai X, Fan L, Li X, Qin Y, Hu FB. Passive smoking and risk of peripheral arterial disease and ischemic stroke in Chinese women who never smoked. Circulation. 2008;118:1535–1540. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.784801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Syed FF, Beeching NJ. Lower-limb deep-vein thrombosis in a general hospital: risk factors, outcomes and the contribution of intravenous drug use. QJM. 2005 Feb;98(2):139–145. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hci020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lowe GD. Common risk factors for both arterial and venous thrombosis. Br J Haematol. 2008;140:488–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Severinsen MT, Kristensen SR, Johnsen SP, Dethlefsen C, Tjonneland A, Overvad K. Smoking and venous thromboembolism: a Danish follow-up study. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:1297–1303. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyers DG, Neuberger JS, He J. Cardiovascular Effect of Bans on Smoking in Public Places: Asystematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1249–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sargent RP, Shepard RM, Glantz SA. Reduced incidence of admissions for myocardial infarction associated with public smoking ban: before and after study. Br Med J. 2004;328:977–980. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38055.715683.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, Critchley JA, Labarthe DR, Kottke TE, Giles WH, Capewell S. Explaining the decrease in U.S. deaths from coronary disease, 1980–2000. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2388–2398. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardoon SL, Whincup PH, Lennon LT, Wannamethee SG, Capewell S, Morris RW. How much of the recent decline in the incidence of myocardial infarction in British men can be explained by changes in cardiovascular risk factors? Evidence from a prospective population-based study. Circulation. 2008;117:598–604. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.705947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giesen PL, Rauch U, Bohrmann B, Kling D, Roque M, Fallon JT, Badimon JJ, Himber J, Riederer MA, Nemerson Y. Blood-borne tissue factor: another view of thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2311–2315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Falati S, Liu Q, Gross P, Merrill-Skoloff G, Chou J, Vandendries E, Celi A, Croce K, Furie BC, Furie B. Accumulation of tissue factor into developing thrombi in vivo is dependent upon microparticle P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 and platelet P-selectin. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1585–1598. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mackman N. Role of tissue factor in hemostasis, thrombosis, and vascular development. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1015–1022. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000130465.23430.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morel O, Toti F, Hugel B, Bakouboula B, Camoin-Jau L, Dignat-George F, Freyssinet JM. Procoagulant microparticles: disrupting the vascular homeostasis equation? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2594–2604. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000246775.14471.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu ML, Reilly MP, Casasanto P, McKenzie SE, Williams KJ. Cholesterol enrichment of human monocyte/macrophages induces surface exposure of phosphatidylserine and the release of biologically-active tissue factor-positive microvesicles. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:430–435. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000254674.47693.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holschermann H, Terhalle HM, Zakel U, Maus U, Parviz B, Tillmanns H, Haberbosch W. Monocyte tissue factor expression is enhanced in women who smoke and use oral contraceptives. Thromb Haemost. 1999;82:1614–1620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Churg A, Wang X, Wang RD, Meixner SC, Pryzdial EL, Wright JL. Alpha1-antitrypsin suppresses TNF-alpha and MMP-12 production by cigarette smoke-stimulated macrophages. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;37:144–151. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0345OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matetzky S, Tani S, Kangavari S, Dimayuga P, Yano J, Xu H, Chyu KY, Fishbein MC, Shah PK, Cercek B. Smoking increases tissue factor expression in atherosclerotic plaques: implications for plaque thrombogenicity. Circulation. 2000;102:602–604. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.6.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambola A, Osende J, Hathcock J, Degen M, Nemerson Y, Fuster V, Crandall J, Badimon JJ. Role of risk factors in the modulation of tissue factor activity and blood thrombogenicity. Circulation. 2003;107:973–977. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000050621.67499.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carp H, Janoff A. Possible mechanisms of emphysema in smokers. In vitro suppression of serum elastase-inhibitory capacity by fresh cigarette smoke and its prevention by antioxidants. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978;118:617–621. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1978.118.3.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yao H, Edirisinghe I, Yang SR, Rajendrasozhan S, Kode A, Caito S, Adenuga D, Rahman I. Genetic ablation of NADPH oxidase enhances susceptibility to cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation and emphysema in mice. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1222–1237. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hellermann GR, Nagy SB, Kong X, Lockey RF, Mohapatra SS. Mechanism of cigarette smoke condensate-induced acute inflammatory response in human bronchial epithelial cells. Respir Res. 2002;3:22. doi: 10.1186/rr172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuo WH, Chen JH, Lin HH, Chen BC, Hsu JD, Wang CJ. Induction of apoptosis in the lung tissue from rats exposed to cigarette smoke involves p38/JNK MAPK pathway. Chem-biol Interact. 2005;155:31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arredondo J, Chernyavsky AI, Jolkovsky DL, Pinkerton KE, Grando SA. Receptor-mediated tobacco toxicity: cooperation of the Ras/Raf-1/MEK1/ERK and JAK-2/STAT-3 pathways downstream of alpha7 nicotinic receptor in oral keratinocytes. FASEB J. 2006;20:2093–2101. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6191com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li CJ, Ning W, Matthay MA, Feghali-Bostwick CA, Choi AM. MAPK pathway mediates EGR-1-HSP70-dependent cigarette smoke-induced chemokine production. Am J Physiol. 2007;292:L1297–1303. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00194.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Syed DN, Afaq F, Kweon MH, Hadi N, Bhatia N, Spiegelman VS, Mukhtar H. Green tea polyphenol EGCG suppresses cigarette smoke condensate-induced NF-kappaB activation in normal human bronchial epithelial cells. Oncogene. 2007;26:673–682. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee YC, Chuang CY, Lee PK, Lee JS, Harper RW, Buckpitt AB, Wu R, Oslund K. TRX-ASK1-JNK signaling regulation of cell density-dependent cytotoxicity in cigarette smoke-exposed human bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 2008;294:L921–931. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00250.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Birrell MA, Wong S, Catley MC, Belvisi MG. Impact of tobacco-smoke on key signaling pathways in the innate immune response in lung macrophages. J Cell Physiol. 2008;214:27–37. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim H, Liu X, Kohyama T, Kobayashi T, Conner H, Abe S, Fang Q, Wen FQ, Rennard SI. Cigarette smoke stimulates MMP-1 production by human lung fibroblasts through the ERK1/2 pathway. COPD. 2004;1:13–23. doi: 10.1081/COPD-120030164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mercer BA, Wallace AM, Brinckerhoff CE, D'Armiento JM. Identification of a cigarette smoke-responsive region in the distal MMP-1 promoter. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;40:4–12. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0310OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aoshiba K, Tamaoki J, Nagai A. Acute cigarette smoke exposure induces apoptosis of alveolar macrophages. Am J Physiol. 2001;281:L1392–1401. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.6.L1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.D'Agostini F, Balansky RM, Izzotti A, Lubet RA, Kelloff GJ, De Flora S. Modulation of apoptosis by cigarette smoke and cancer chemopreventive agents in the respiratory tract of rats. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:375–380. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.3.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rangasamy T, Cho CY, Thimmulappa RK, Zhen L, Srisuma SS, Kensler TW, Yamamoto M, Petrache I, Tuder RM, Biswal S. Genetic ablation of Nrf2 enhances susceptibility to cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in mice. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1248–1259. doi: 10.1172/JCI21146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fujihara M, Nagai N, Sussan TE, Biswal S, Handa JT. Chronic cigarette smoke causes oxidative damage and apoptosis to retinal pigmented epithelial cells in mice. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3119. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Howard G, Thun MJ. Why is environmental tobacco smoke more strongly associated with coronary heart disease than expected? A review of potential biases and experimental data. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107(Suppl 6):853–858. doi: 10.1289/ehp.99107s6853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raupach T, Schafer K, Konstantinides S, Andreas S. Secondhand smoke as an acute threat for the cardiovascular system: a change in paradigm. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:386–392. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schroeter MR, Sawalich M, Humboldt T, Leifheit M, Meurrens K, Berges A, Xu H, Lebrun S, Wallerath T, Konstantinides S, Schleef R, Schaefer K. Cigarette Smoke Exposure Promotes Arterial Thrombosis and Vessel Remodeling after Vascular Injury in Apolipoprotein E-Deficient Mice. J Vasc Res. 2008;45:480–492. doi: 10.1159/000127439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heiss C, Amabile N, Lee AC, Real WM, Schick SF, Lao D, Wong ML, Jahn S, Angeli FS, Minasi P, Springer ML, Hammond SK, Glantz SA, Grossman W, Balmes JR, Yeghiazarians Y. Brief secondhand smoke exposure depresses endothelial progenitor cells activity and endothelial function: sustained vascular injury and blunted nitric oxide production. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1760–1771. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhuang S, Schnellmann RG. A death-promoting role for extracellular signal-regulated kinase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:991–997. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.107367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhuang S, Yan Y, Daubert RA, Han J, Schnellmann RG. ERK promotes hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptosis through caspase-3 activation and inhibition of Akt in renal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F440–447. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00170.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu JP, Schlosser R, Ma WY, Dong Z, Feng H, Liu L, Huang XQ, Liu Y, Li DW. Human alphaA- and alphaB-crystallins prevent UVA-induced apoptosis through regulation of PKCalpha, RAF/MEK/ERK and AKT signaling pathways. Exp Eye Res. 2004;79:393–403. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guha M, O'Connell MA, Pawlinski R, Hollis A, McGovern P, Yan SF, Stern D, Mackman N. Lipopolysaccharide activation of the MEK-ERK1/2 pathway in human monocytic cells mediates tissue factor and tumor necrosis factor alpha expression by inducing Elk-1 phosphorylation and Egr-1 expression. Blood. 2001;98:1429–1439. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.5.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bea F, Puolakkainen MH, McMillen T, Hudson FN, Mackman N, Kuo CC, Campbell LA, Rosenfeld ME. Chlamydia pneumoniae induces tissue factor expression in mouse macrophages via activation of Egr-1 and the MEK-ERK1/2 pathway. Cir Res. 2003;92:394–401. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000059982.43865.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Devaraj S, Dasu MR, Singh U, Rao LV, Jialal I. C-reactive protein stimulates superoxide anion release and tissue factor activity in vivo. Atherosclerosis. 2009;203:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.05.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zwaal RF, Schroit AJ. Pathophysiologic implications of membrane phospholipid asymmetry in blood cells. Blood. 1997;89:1121–1132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Henriksson CE, Klingenberg O, Ovstebo R, Joo GB, Westvik AB, Kierulf P. Discrepancy between tissue factor activity and tissue factor expression in endotoxin-induced monocytes is associated with apoptosis and necrosis. Thromb Haemost. 2005;94:1236–1244. doi: 10.1160/TH05-07-0463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lechner D, Kollars M, Gleiss A, Kyrle PA, Weltermann A. Chemotherapy-induced thrombin generation via procoagulant endothelial microparticles is independent of tissue factor activity. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:2445–2452. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stampfuss JJ, Censarek P, Bein D, Schror K, Grandoch M, Naber C, Weber AA. Membrane environment rather than tissue factor expression determines thrombin formation triggered by monocytic cells undergoing apoptosis. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:1379–1381. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1207843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McGuinness CL, Humphries J, Waltham M, Burnand KG, Collins M, Smith A. Recruitment of labelled monocytes by experimental venous thrombi. Thromb Haemost. 2001;85:1018–1024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gross PL, Furie BC, Merrill-Skoloff G, Chou J, Furie B. Leukocyte-versus microparticle-mediated tissue factor transfer during arteriolar thrombus development. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:1318–1326. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0405193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leroyer AS, Isobe H, Leseche G, Castier Y, Wassef M, Mallat Z, Binder BR, Tedgui A, Boulanger CM. Cellular origins and thrombogenic activity of microparticles isolated from human atherosclerotic plaques. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:772–777. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Osterud B, Bjorklid E. Sources of tissue factor. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2006;32:11–23. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-933336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.