Abstract

Alcoholism remain a serious cause of morbidity and mortality, despite progress through neurobiological research in identifying new pharmacological strategies for its treatment. Drugs that affect neural pathways that modulate the activity of the cortico-mesolimbic dopamine system have been shown to alter drinking behavior, presumably because this dopaminergic system is closely associated with rewarding behavior. Ondansetron, naltrexone, topiramate, and baclofen are examples. Subtyping alcoholism in adults into an early-onset type, with chronic symptoms and a strong biological predisposition to the disease, and a late-onset type, typically brought on by psychosocial triggers and associated with mood symptoms, may help in the selection of optimal therapy. Emerging adults with binge-drinking patterns also might be aided by selective treatments. Although preliminary work on the pharmacogenetics of alcoholism and its treatment has been promising, the assignment to treatment still depends on clinical assessment. Brief behavioral interventions that encourage the patient to set goals for a reduction in heavy drinking or abstinence also are part of optimal therapy.

Alcohol dependence in the U.S. ranks 3rd on the list of preventable causes of morbidity and mortality (1). In 2000, the U.S. had 20,687 alcohol-related deaths, excluding accidents and homicides, costing the nation about $185 billion (1).

Alcohol dependence often follows a chronic relapsing course (2) similar to other medical disorders such as diabetes. Despite its psychological and social sequelae, once established, alcohol dependence is essentially a brain disorder. Without a pharmacological adjunct to psychosocial therapy, the clinical outcome is poor, with up to 70% of patients resuming drinking within 1 year (3, 4). Therefore, psychosocial intervention alone is not optimal treatment for alcohol dependence. Furthermore, it appears that brief interventions (e.g., brief behavioral compliance enhancement treatment (BBCET) (5) or medical management (MM) (6)) are sufficient to optimize treatment with an efficacious medicine, and there is no need for more formal or intensive psychotherapy. Indeed, in a recent study, intensive psychotherapy was shown to be less effective than a brief intervention plus a placebo pill for the treatment of alcohol dependence (7). Hence, there is no longer a clinical rationale to delay starting pharmacotherapy, which can be provided with a brief psychosocial intervention in general practice.

SUBTYPES OF ALCOHOLISM

Alcohol dependence is a heterogeneous disorder. Many authorities agree that there are different subtypes of alcoholic, although this is not encapsulated within Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) (8). As adapted from Cloninger's classification scheme (9), there are at least two different subtypes of alcoholism. Type B-like or early-onset alcoholism is characterized by high familial loading, a broad range of impulse-dyscontrol traits, and an early onset (before the age of 25 years) of problem drinking (Case 1). In contrast, Type A-like or late-onset alcoholism is characterized by a later age of onset of problem drinking (typically 25 years or older), a preponderance of psychosocial morbidity, and low familial loading for the alcoholism disease (Case 2). While several complicated, theoretical, and retrospective constructs have been used to delineate alcoholic subtype (10–12), it appears that a single question—“…at what age did drinking become a problem for you?” (13)—can be applied in clinical practice to segregate subtypes of alcoholism. How the subtype of alcoholism an individual possesses can determine the choice of pharmacotherapy (14) is discussed below. Subtype classification of the alcoholism disease does, however, remain somewhat controversial. For example, others have proposed more elaborate classification schemes—with up to four subtypes—that might respond differentially to particular therapeutic agents (15, 16). In the future, more contemporary and accurate alcoholic subtype classification schemes that employ molecular genetic markers predominantly, either with or without additional epidemiological or psychosocial determinants, may be more predictive of drinking outcomes and therapeutic response to medications (14).

HAZARDOUS DRINKING IN EMERGING ADULTS

Alcohol use in emerging adulthood is prevalent (17), and much of the drinking occurring during this period could be categorized as hazardous (Case 3). Binge drinking remains frequent among college students despite increased prevention efforts over the past decade (18, 19); 40% of college students have binged in the past 2 weeks according to the College Alcohol Study surveys.

Although college-age binge drinking is often viewed as rite of passage into adulthood, hazardous drinking in emerging adults is associated with serious consequences. Approximately 1500 to 1700 deaths and 600,000 injuries, including 200,000 serious injuries, occur in the U.S. each year among college students (20, 21). The range of health risks and psychosocial consequences due to hazardous drinking among emerging adults includes motor vehicle accidents, legal problems, personal injuries, date rape and other types of violence, unwanted or unprotected sex, sexually transmitted diseases, blackouts, and missing classes (22, 23). Indeed, rates of these problems are high. In 2001, nearly 700,000 students aged 18 to 24 years were assaulted by another college student who had been drinking (21). Over 400,000 students had unprotected sex, and 100,000 reported being too intoxicated to know whether or not they had consented to sex (21). Short-term problems associated with drug and alcohol use in emerging adulthood include violence, depression, and unprotected sex (19, 24). The risk for sexually transmitted diseases due to multiple sex partners and unprotected sex is increased during periods such as “spring break” when casual sex, impulsivity, and reduced availability of condoms are compounded with increased use of, or bingeing on, alcohol or drugs (25). College students (25%) report drinking-related academic problems such as missing classes, falling behind, doing poorly on exams and papers, or getting lower grades (19, 26, 27). Alcohol-related consequences are more likely among those classified as hazardous vs. non-hazardous drinkers (28).

Severe or binge drinking may have long-term negative health consequences, even among those who avoid injuries. Those who drink severely or binge drink between the ages of 18 and 24 years are more likely to progress to alcohol abuse or dependence diagnoses (29, 30). Despite being at particularly high risk, college students do not differ from non-college students on alcohol dependence criteria (31, 32); results in these two studies are mixed on whether the two groups differ in alcohol abuse rates. Because episodic severe or binge drinking and alcohol use disorders are common among all emerging adults, research on college students generalizes well to other emerging adults. However, their residence status relates to risk for diagnosis, with more alcohol abuse and less alcohol dependence occurring among students living off campus (31).

Among college students, 31% in one large study met diagnostic criteria for alcohol abuse and 6% for alcohol dependence (33). Emerging adults evidencing an alcohol use disorder generally have associated problems such as alcohol-related blackouts and increased craving for alcohol (34). The long-term effects can be serious as severe or binge drinking during college can predict rates of alcohol use disorders up to 10 years later (35, 36).

ALCOHOL DEPENDENCE AND DEPRESSION

Data on 43,000 adults from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) (37) indicated that among those with a 12-month or lifetime history of major depressive disorder, the rate of alcohol use disorder was 14% and 40%, respectively (38). The NESARC data also reported that among those with major depression, the odds ratio for alcohol dependence ranges from 1.3 to 2.1 (38); however, higher ratios of 4 to 7 have been reported by others (39, 40), suggesting some shared genetic linkages (41). Older women who live alone may be particularly prone to alcohol misuse and depression due to loneliness (Case 2) (42). Depressive symptoms also occur frequently among those with alcohol dependence, especially during withdrawal when insomnia, anxiety, and dysphoric mood (43) can complicate the course of the illness (44). Therefore, all practitioners, when presented with an alcohol-dependent patient, should routinely examine for depressive symptoms including suicidal ideation.

NEUROBIOLOGY OF ALCOHOL DEPENDENCE

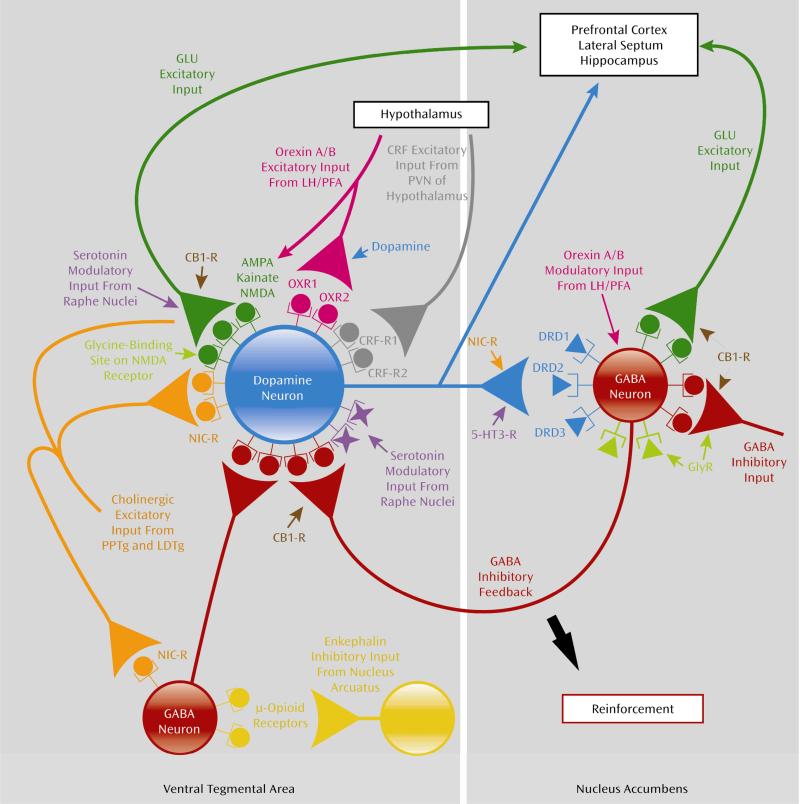

New pharmacological treatments target modulation of the cortico-mesolimbic dopamine system, a network that governs alcohol's reinforcing effects, which are associated with its abuse liability (45). As shown in Figure 1, several neurotransmitter systems interact and modulate the cortico-mesolimbic dopamine system (46). The expression of the reinforcing effects of alcohol is a summation of neurotransmitter systems involved with drive, mood, and cognition. Interestingly, the more promising agents for the reduction of heavy drinking or the prevention of relapse to heavy drinking appear to be those that modulate the cortico-mesolimbic dopamine system through the opioid, glutamate, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), or serotonin (5-HT) systems. Indeed, due to counter-regulatory neuroadaptation, agents that block cortico-mesolimbic dopamine system neurons directly typically lack therapeutic efficacy and might even provoke an increase in alcohol consumption (47). Lately, there has been improved understanding of how stress-related neurotransmitters (e.g., corticotrophin-releasing factor) in the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, as well as neuroregulators and neuropeptides (e.g., hypocretin, vasopressin, and neuropeptide Y) in the external amygdala, modulate the reinforcing effects of alcohol and other drugs of abuse (48). Medications that target these antistress pathways, which go beyond the cortico-mesolimbic theory and have been coined romantically as the “dark side” of addiction, are being explored as putative therapeutic agents to decrease or prevent relapse.

Figure 1.

Neuronal pathways involved with the reinforcing effects of alcohol and other drugs of abuse. Cholinergic inputs arising from the caudal part of the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus (PPTg) and laterodorsal tegmental nucleus (LDTg) can stimulate ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons. The ventral tegmental area dopamine neuron projection to the nucleus accumbens and cortex, the critical substrate for the reinforcing effects of drugs of abuse (including alcohol), is modulated by a variety of inhibitory [gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and opioid] and excitatory [nicotinic (NIC-R), glutamate (GLU), and cannabinoid-1 receptor (CB1-R)] inputs. The glutamate pathways include those that express alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionate (AMPA), kainate, and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. Serotonin-3 receptors (5-HT3-R) also modulate dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens. The glycine system, orexins, and corticotropin-releasing factor also are shown. CRF-R1, CRF-R2=corticotropin-releasing factor receptors 1 and 2; DRD1, DRD2, DRD3=dopamine receptors D1, D2, and D3; GlyR=glycine receptor; LH/PFA=perifornical region of the lateral hypothalamus; OXR1, OXR2=orexin receptor types 1 and 2; PVN=paraventricular nucleus. Adapted and embellished from Johnson (46) (copyright © 2006 American Medical Association; all rights reserved).

EVALUATING AND TREATING ALCOHOLISM

Taking an alcohol history

The NIAAA Clinician's Guide (49) recommends that a first step in identifying at-risk drinking, alcohol abuse, or alcohol dependence is for the practitioner to screen patients effectively in general health settings including in emergency departments, during hospital visits, and in outpatient or community clinics. All patients presenting for medical care should be asked the screening question: “Do you sometimes drink, beer, wine, or other alcoholic beverages?” If the answer to that question is “yes”, a 5-minute screening questionnaire, the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (50), should be administered. An AUDIT score of <8 for men and <4 for women should be used by practitioners as an opportunity to reinforce drinking habits within “safe” drinking limits, which are ≤4 standard drinks/day and ≤14 standard drinks/week for men <65 years old and ≤3 standard drinks/day and ≤7 standard drinks/week for women <65 years. For those over 65, the “safe” limit for both men and women is ≤3 standard drinks/day and ≤7 standard drinks/week. One standard drink is 0.5 oz of absolute alcohol, equivalent to 10 oz of beer, 4 oz of wine, or 1 oz of 100-proof liquor (51). An AUDIT score of ≥8 for men or ≥4 for women—suggestive of excessive drinking—should prompt even more detailed questions about the patient's drinking.

Detailed questions about drinking should start with the first time the patient: took a drink, drank regularly, recognized that drinking was a problem (i.e., by causing physical harm or accidents, discordant relationships with family or friends, failure to perform obligations at school or work, and legal problems such as driving under the influence), had to drink more to get a “buzz” or a “high”, experienced insomnia, sweating, tremors, or nausea several hours after cessation of drinking, and noticed spending most of the day thinking about or actually drinking irrespective of the consequences. Each of these questions about first drinking-related behaviors should be followed up by establishing the behavior's severity and course. Based on the patient's responses, especially those pertaining to the preceding 12-month period, a diagnosis of alcohol abuse or dependence can be made according to DSM-IV-TR criteria (8). Finally, the practitioner should quantify carefully the amount of alcohol consumed each week in standard drinks. A useful method for ascertaining this reliably would be for the practitioner to ask patients to pour into a clean measuring jug the amount of their preferred beverage that they consume, on average, each day. If the patient binges on weekends or at other times, the practitioner should ask him or her to pour an amount of water into the measuring jug equivalent to how much alcohol he or she consumed during the heaviest drinking day. The practitioner must establish whether the patient is still actively drinking, has recently stopped, or has been abstinent for a verifiable amount of time. Information pertaining to current drinking level, especially in the preceding month, should be compared with drinking levels after the initiation of treatment to chart progress.

Diagnosis and pharmacotherapeutic options

The first patient is a middle-aged schoolteacher who meets DSM-IV-TR (8) criteria for alcohol dependence. The age of problem drinking onset could not be ascertained. The patient does, however, have a possible family history of alcohol dependence in his father and antisocial traits, as well as medical complications that include high blood pressure and cholesterol and liver impairment. In all, this patient has a severe form of alcohol dependence with a chronic and pervasive course. The first step in treatment should be to negotiate a drinking goal with the patient. Whilst the gold standard of a positive treatment outcome is complete abstinence, some patients need to be helped toward this goal by setting increasingly lower levels of heavy drinking.

Given the severe nature of the patient's alcohol dependence and the fact that he is still drinking heavily and had important medical complications, my choice of pharmacotherapy is topiramate. An additional advantage of topiramate in this patient is that because it is excreted mostly unchanged by the kidneys in the urine (52), there would be reduced risk of the medication worsening his developing liver impairment. Topiramate, a sulfamate-substituted fructopyranose derivative, has been shown in two large-scale, randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trials to improve all drinking outcomes including a reduction of heavy drinking and a promotion of abstinence (53, 54). Topiramate is presumed to decrease its anti-drinking effects by cortico-mesolimbic dopamine system modulation through the facilitation of GABA function via a non-benzodiazepine site on the GABA-A receptor (55) and the antagonism of glutamate activity at alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid and kainate receptors (56). Topiramate also has been shown to decrease the medical consequences of alcohol dependence including obesity, hypertension, liver abnormality, and high cholesterol; however, it is unknown whether this is an effect independent of its anti-drinking properties (57). Topiramate is generally well tolerated, and the more common adverse events associated with its use include paresthesia, taste perversion, anorexia, and difficulty with concentration.

Topiramate treatment should be initiated at a dose of 25 mg/day and titrated over 8 weeks up to 300 mg/day (Table 1) (53) while a brief intervention such as BBCET is provided on a weekly basis (5). Care should be taken in titrating the dose of topiramate slowly, and even tardier dose-escalation schedules should be considered, if necessary. The practitioner should be aware that topiramate's efficacy appears to be evident at a dose as low as 100 mg/day. Therefore, stopping topiramate titration at this dose (i.e., 100 mg/day) may be considered if tolerability is a problem. Although the clinical trials for alcohol dependence in the U.S. typically report shorter-term outcomes (i.e., 3–6 months), prudent clinical practice would suggest that most patients need to be treated for 6 months to 1 year to increase the likelihood of a remission.

Table 1.

Topiramate Dose Escalation Schedule for Treatment of Alcohol Dependence

| Week | Morning Dose | Afternoon Dose | Total Daily Dose |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 mg | 1×25-mg tablet | 25 mg |

| 2 | 0 mg | 2×25-mg tablets | 50 mg |

| 3 | 1×25-mg tablet | 2×25-mg tablets | 75 mg |

| 4 | 2×25-mg tablets | 2×25-mg tablets | 100 mg |

| 5 | 2×25-mg tablets | 1×100-mg tablet | 150 mg |

| 6 | 1×100-mg tablet | 1×100-mg tablet | 200 mg |

| 7 | 1×100-mg tablet | 1×100-mg and 2×25-mg tablets | 250 mg |

| 8 | 1×100-mg and 2×25-mg tablets | 1×100-mg and 2×25-mg tablets | 300 mg |

| 9 | 1×100-mg and 2×25-mg tablets | 1×100-mg and 2×25-mg tablets | 300 mg |

| 10 | 1×100-mg and 2×25-mg tablets | 1×100-mg and 2×25-mg tablets | 300 mg |

| 11 | 1×100-mg and 2×25-mg tablets | 1×100-mg and 2×25-mg tablets | 300 mg |

| 12 | 1×100-mg and 2×25-mg tablets | 1×100-mg and 2×25-mg tablets | 300 mg |

Reprinted from Johnson et al. (53), with permission from Elsevier.

An alternative treatment medication for this patient would be baclofen—an agonist at pre-synaptic GABA-B (bicuculline-insensitive) receptors that appears to act by modulation of G-protein-gated inwardly rectifying potassium channels (GIRK, Kir3) to suppress cortico-mesolimbic dopamine system neurons (58). Related to this patient, baclofen might be useful as it has shown promise to treat alcohol dependence, particularly among those with liver impairment (59). Baclofen is excreted primarily through the kidneys. Like topiramate, it is recommended to titrate baclofen, from a starting dose of 5 mg three times daily in the first 3 days, and then to the ceiling dose of 10 mg three times daily. Unlike topiramate, baclofen is administered to patients who have already become abstinent, possibly by the use of a reducing dose of the benzodiazepine chlordiazepoxide on an outpatient basis. While baclofen might itself aid in reducing alcohol withdrawal symptoms (60), its cessation should be gradual to avoid the emergence of withdrawal symptoms of its own such as confusion, hallucinations, anxiety, perceptual disturbance, and extreme muscle rigidity with or without spasticity. Common adverse events associated with baclofen administration include headaches, insomnia, nausea, hypotension, urinary frequency, and, rarely, excitement and visual abnormalities (61).

The second patient is an elderly lady who meets DSM-IV-TR (8) criteria for alcohol dependence. Alcohol dependence among the elderly is often under-diagnosed, and every practitioner should be diligent to inquire about drinking habits in this age group (62). The first step in treatment should be to negotiate a drinking goal with the patient. Because of the high association of morbidity and mortality among elderly alcohol-dependent patients, the practitioner should negotiate a goal, or a sequence of targets, that culminate in abstinence.

Given the age of the patient, which may make her prone to forgetfulness, and her relative isolation, my choice of pharmacotherapy would be Vivitrol®, an injectable form of naltrexone. After a period of abstinence (3–5 days), which might require supportive benzodiazepine treatment (i.e., a reducing dose of chlordiazepoxide), the patient can be scheduled to receive Vivitrol® 400 mg/month for 4 months. Vivitrol®, administered on a monthly basis, has an efficacy and adverse-event profile that is similar to that of oral naltrexone. Vivitrol® administration should be accompanied by a brief intervention (e.g., BBCET or MM).

Notably, while consideration would be given toward adding an antidepressant such as a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) to the medication regime, it would not be appropriate to do this at present with this patient for three reasons. First, the patient does not meet DSM-IV-TR (8) criteria for major depression, and the reported “gloominess” is likely to lift as her drinking outcomes improve, particularly if there are fewer episodes of heavy drinking or increasing periods of abstinence. Second, SSRIs have mainly shown added benefit in comorbid alcohol-dependent and depressed patients when the symptoms of dysphoric mood are marked and accompanied by suicidal ideation (63). Third, the patient's age of problem drinking onset would have to be determined more accurately because SSRIs can trigger an increase (rather than a decrease) in alcohol consumption among late-onset alcoholics.

The clinical hallmarks of the third patient are those of an emerging adult who meets DSM-IV-TR (8) criteria for alcohol dependence. The first step in treatment should be to educate the patient about the health risks associated with his dependence on alcohol and sensitize him to the risky behaviors in which he engages. In this age group, a motivation-based approach appears to be most useful in setting treatment goals that, typically, focus on reducing binge and heavy drinking episodes.

Given that the patient has a moderate severity of alcohol dependence, is still drinking, and had an early onset of problem drinking with a strong family history, the optimal treatment option would be ondansetron, a 5-HT3 antagonist that exerts its anti-drinking effects through cortico-mesolimbic dopamine system modulation. Ondansetron has been shown to improve the drinking outcomes of early-onset alcoholics. Adverse events are mild (usually constipation, headaches, and sedation), and the starting dose of 4 μg/kg twice daily should be maintained throughout treatment. Unfortunately, however, ondansetron is not, at present, available commercially at the therapeutic treatment dose for alcohol dependence, so it is not a practical alternative outside research treatment settings.

An alternative pharmacotherapeutic option would be the mu-opioid antagonist naltrexone, accompanied by a brief intervention provided on a weekly basis (such as medical management, which was shown to be effective in the COMBINE study (7)). Naltrexone was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1994 for the treatment of alcohol dependence, and its anti-drinking properties have been attributed to cortico-mesolimbic dopamine system modulation (47). Furthermore, therapeutic response to naltrexone appears to be enhanced among those with a family history of alcoholism (64). Naltrexone should be provided at a dose that escalates up to 100 mg/day after the patient has been abstinent for 3 to 5 days. A reducing dose of benzodiazepines (i.e., chlordiazepoxide) can be prescribed on an outpatient basis according to a standardized schedule (66) to facilitate the achievement of the brief period of abstinence needed before pharmacotherapy is started. Common adverse events associated with naltrexone treatment include nausea and somnolence. Treatment should be continued for as long as possible (i.e., at least 2 months).

To date, no published study has examined exclusively the utility of pharmacotherapy coupled with a brief intervention for the treatment of alcohol dependence among emerging adults. Hence, this recommendation is an extrapolation from adult studies with overlapping populations. Notably, among emerging adults, the mainstay of treatment has been brief intervention alone. However, the severity of established alcohol dependence in this patient, rather than just alcohol abuse, suggests that additional pharmacotherapy would be needed to obtain a favorable treatment outcome.

Nevertheless, a brief motivational intervention that has been used frequently to treat college students who binge drink — the Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS) (65) — may be used as the adjunct to the pharmacotherapy. The BASICS program provides personal feedback, motivation, and strategies that enhance normative drinking patterns (67). It is typically given as a low-intensity intervention, every 2 weeks, over about 8 weeks. The BASICS program is the most well-validated, motivation-based, brief intervention that has been employed in treating emerging adults with alcohol-related disorders.

Clinical monitoring

An important aspect of clinical monitoring is continuing to quantify drinking behavior and setting appropriate target goals for the reduction or cessation of alcohol consumption. Brief interventions such as BBCET or MM offer a convenient method for setting treating goals while providing motivation and reinforcing medication compliance. Presently, the clinical evidence points to the use of these brief interventions with medications rather than to intensive or more formal psychotherapies as adjuncts to pharmacotherapy. Notably, because brief interventions are more generalizable to general practice, their use with efficacious pharmacotherapies should broaden access to care.

In sum, despite the apparent disparity of presentation of the three patients in this report, non-specialist practitioners in an office-based practice can manage them all successfully. Any assistance needed with detoxification can be done on an outpatient basis, and hospital admission for detoxification should be considered only in extreme cases (66). These would include a previous history of seizures or delirium tremens or serious medical complications such as uncontrolled diabetes or fulminant heart disease.

Other pharmacotherapeutic options

Other pharmacotherapeutic choices are available that could have been provided for the patients presented here. From the list of other FDA-approved medications, disulfiram (an inhibitor of alcohol dehydrogenase) could have been considered. However, disulfiram treatment was not proposed because its efficacy appears dependent on having a partner ensure compliance with the medication (68), rendering it a “psychological pill”. Its effects thus derive from the agreement of the patient to take a medication that is part of a daily pledge of abstinence. Furthermore, disulfiram has no effect at reducing the urge or propensity to drink, which newer medications such as naltrexone, ondansetron, and topiramate have been reported to do (47). Acamprosate (a modulator of glutamate neurotransmission at metabotropic-5 glutamate receptors) (69) also has been FDA approved for the treatment of alcohol dependence, principally on the basis of European studies, but the failure of two large double-blind U.S. studies has cast doubt on its efficacy (47).

Several new molecular targets are being researched actively for the treatment of alcohol dependence (see Figure 1) (46). Apart from those already mentioned, active research is being done to evaluate the efficacy of promising agents such as the neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist, LY686017 (70) and gabapentin (a modulator of voltage-gated N-type calcium channels) (71). Because recent double-blind trials have not found efficacy for aripiprazole (72) or the cannabinoid receptor-1 antagonist, rimonabant, in the treatment of alcohol dependence, there is less optimism in the pursuit of these targets.

Medication combinations, by being able to target several neurotransmitters simultaneously, also hold the promise of greater efficacy in the treatment of alcohol dependence. However, this research is in its infancy, and the early promise of combining naltrexone and acamprosate (73) appears unlikely to pan out (7). Other medication combinations are currently being tested, and the results of these studies are expected soon (47).

Future pharmacogenetic approaches

Personalized medicine promises to optimize treatment response to ensure that the “right” medicine is provided to a specific group of people with a disease who would benefit the most. Although examination of the pharmacogenetic effects on treatment response has aroused the most clinical interest, other fields, such as metabolomics, are equally important to our understanding of the biological factors that govern sensitivity to drug effects.

In a retrospective analysis of a double-blind clinical trial of alcohol-dependent individuals of European descent who received naltrexone, Oslin et al. (74) reported that those with one or two copies of the opioid receptor micro 1 (OPRM1) Asp40 allele, compared with their homozygous counterparts, were less likely to return to heavy drinking and had a longer time to return to heavy drinking. A similar pattern of results was reported in the COMBINE study (75), but the size of the effect was small, and the results are contradicted by other clinical studies that have examined the role of the OPRM1 Asp40 allele in predicting treatment response to naltrexone (76) and the mu-opioid receptor antagonist nalmefene (77). Hence, the role of the OPRM1 Asp40 allele in predicting response to naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence remains to be established firmly.

Serotonergic function is an important mediator of mood, impulsivity, and appetitive behaviors, including alcohol consumption. Of the mechanisms controlling synaptic 5-HT concentration, perhaps the most compelling relates to the functional state of the pre-synaptic 5-HT transporter (5-HTT). The 5-HTT is responsible for removing 5-HT from the synaptic cleft (78). Indeed, up to 60% of neuronal 5-HT function is gated by the 5-HTT. The 5-HTT gene is found at the SLC6A4 locus on chromosome 17q11.1–q12, and its 5′-regulatory promoter region contains a functional polymorphism known as the 5-HTT-linked polymorphic region (79, 80). The polymorphism is an insertion/deletion mutation in which the long (L) variant has 44 base pairs that are absent in the short (S) variant. Due to the differential transcription rates between LL allelic variants compared with their SS counterparts, variation at the 5-HTT gene is an interesting candidate for examining sensitivity to alcohol and treatment response to ondansetron among alcohol-dependent individuals. It is, therefore, of interest that alcohol-dependent individuals who are L-allelic variants, compared with their SS counterparts, may have greater craving for alcohol (81). Furthermore, a recent pilot study in the human laboratory has suggested that individuals with the LL genotype might be particularly responsive to ondansetron (82). Results of the first large-scale, prospective pharmacogenetic study in the alcoholism field to test whether 5-HTT gene allelic variation predicts therapeutic response to ondansetron are awaited eagerly. If the results of this study are positive, it has the potential to make a personalized approach to the treatment of alcohol dependence a reality, whereby potential responders are identified through specific genetic markers and treated with ondansetron.

SUMMARY

Alcohol dependence is a heterogeneous chronic, relapsing brain disorder. All practitioners should be familiar with its early detection. Alcohol dependence is treatable, and the use of efficacious pharmacotherapies has opened up the potential of office-based treatment by non-specialists. Appropriate pharmacotherapy, along with a brief psychosocial intervention, constitutes optimal treatment. Choice of therapy can be guided by the patient's history of alcoholism and the stage of life and, in the future, perhaps by pharmacogenetics.

Three Different Types of Alcoholism (format as patient vignettes).

Case # 1. Chronic alcoholism

A 55-year-old schoolteacher visited his family practitioner complaining of headaches that start soon after awaking at about 4:00 AM, usually at the beginning of the week. The headaches have been getting worse over the past year, have a moderately intense dull and aching quality, and are typically located in the back of the patient's head but he cannot be sure. They are relieved about 1 hour after breakfast, which consists of cereal, and, occasionally, by taking 1 g of acetaminophen.

On taking his medical history, the family practitioner found out that the patient's father had the reputation of a “man who could hold his drink” but died in a hunting accident at the age of 50 years. The patient reported that he has been married three times, at ages 19, 22, and 25 years. None of his marriages lasted more than 2 years, and he said that his ex-wives became “controlling and difficult” about his lifestyle.

Further inquiry about the patient's lifestyle by his doctor revealed that he likes to “hang out” with his mates at weekends, starting from happy hour after payday on Thursday. These drinking habits with “buddies” have persisted since he left high school. The patient did not recall exactly how much alcohol he drank but believed that it was “definitely” more than two six-packs each day from Thursday to Sunday. He reported being able to “hold his drink” like his father and denies getting drunk. Indeed, he boasted that he has had no problems driving himself home although he received a citation for driving while intoxicated about a year ago, a charge that was dismissed due to a legal technicality. The patient did not recall the age at which he started to consume alcohol. He denied using any illicit drugs and became angry when asked about this.

On physical examination, the family practitioner found that the patient was obese (body mass index 29) and hypertensive (blood pressure 150/100), and his biochemical analysis revealed elevated liver enzymes (alanine aminotransferase 99 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase 80 U/L, and gamma-glutamyltransferase 210 U/L), albumin 28 g/L, and cholesterol (221 mg/dL.

Case # 2. Late-life alcoholism

A 66-year-old, retired, single teacher presented to her family practitioner because she often feels “gloomy”. The patient reported that there was no clear pattern to her gloominess but that watching the news about the financial crisis over the last 2 years had not helped. Indeed, the patient described that the financial crisis had caused her to lose most of her pension and that she was now contemplating a return to some kind of work. The patient was pessimistic about her work prospects—“Who would hire me at this age?” she intimated. She reported that lately she had been drinking more, and now needed a “nightcap” as well as a morning “pick-me-up” to feel like herself. These drinks consisted of two large Bloody Marys. With lunch and dinner, she also usually had two to three glasses of red wine. However, the patient said, “I am not an alcoholic; I have never gotten into any trouble.” She did, however, look forward to her drinks, which she called “comforters”, and said that these are the first items on her shopping list. The patient reported that over the last 6 months, she has tended to drink more to feel “nice”, and had occasional headaches in the morning, which she attributed to “getting old”.

Further inquiry about the patient's lifestyle by the family practitioner revealed that she had few friends and lived in a small retirement community. The patient's sleep was disturbed by awaking early—at about 4:00 AM—with difficulty returning to sleep. Her reported energy level was appropriate for her age. Her appetite had lessened over the last month, but her weight had remained unchanged.

Case # 3. Alcoholism in college

A 21-year-old college student was seen in the emergency room (ER) after falling off his bicycle. The patient had suffered some minor abrasions to his forearm and bruising to his head. A skull x-ray revealed an old calcified linear fracture that had healed, from a previous fall about 4 months earlier

The ER doctor elicited from the patient that he had frequent episodes of falling off his bike, usually in the early evening or late at night. When questioned about his drinking, the patient replied that he is the “usual” college kid and he only drinks on weekends with friends from his fraternity. The patient did not recall how much alcohol he consumed over the weekend—“perhaps a few kegs between me and three friends”—but admitted that getting up for classes on Monday was a “drag” and he often only makes his afternoon classes. He said that sometimes, a little drink in the morning helps to “calm the nerves”. Also, the patient reported that he always looks forward to spring break as he has “the time of his life”—the only time when girls “do not even care about using condoms”. The patient started to drink when he was 16 years old, having been “initiated” by an uncle. He said that over the last year he had been better able to keep up with his friends to “feel good” but it was still less than his friends consumed. Whilst the patient denied that drinking was a problem, he admitted that his mother and an older brother had attended Alcoholics Anonymous meetings “just to see what happened there”. He also reported that he sometimes shares a joint of marihuana with his friends but does not use any other illicit drugs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism for its support through grants 2 R01 AA010522-13, 7 R01 AA010522-12, 5 R01 AA012964-06, 5 R01 AA013964-05, 5 R01 AA014628-04, and 7 U10 AA011776-10; the National Institutes of Health for its support through University of Virginia General Clinical Research Center Grant M01 RR00847, and Robert H. Cormier Jr. for his assistance with manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES Prof. Johnson is a consultant to Johnson & Johnson (Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs LLC), ADial Pharmaceuticals, Organon, Transcept Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Psychological Education Publishing Company (PEPCo LLC), and Eli Lilly and Company.

Copy on all editorial correspondence: Robert H. Cormier, Jr. cormier@virginia.edu

REFERENCES

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 10th Special Report to the U.S. Congress on Alcohol and Health. National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Bethesda, MD: 2000

- 2.McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O'Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284:1689–1695. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swift RM. Drug therapy for alcohol dependence. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1482–1490. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905133401907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finney JW, Hahn AC, Moos RH. The effectiveness of inpatient and outpatient treatment for alcohol abuse: the need to focus on mediators and moderators of setting effects. Addiction. 1996;91:1773–1796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson BA, DiClemente CC, Ait-Daoud N, Stoks SM. In: Brief Behavioral Compliance Enhancement Treatment (BBCET) manual, in Handbook of clinical alcoholism treatment. Johnson BA, Ruiz P, Galanter M, editors. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore, MD: 2003. pp. 282–301. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pettinati HM, Weiss RD, Miller WR, Donovan D, Ernst DB, Rounsaville BJ. Medical Management Treatment Manual: A Clinical Research Guide for Medically Trained Clinicians Providing Pharmacotherapy as Part of the Treatment for Alcohol Dependence. Volume 2. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Bethesda, MD: 2004. (COMBINE Monograph Series). DHHS Publication No. 04-5289. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anton RF, O'Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, Donovan DM, Gastfriend DR, Hosking JD, Johnson BA, LoCastro JS, Longabaugh R, Mason BJ, Mattson ME, Miller WR, Pettinati HM, Randall CL, Swift R, Weiss RD, Williams LD, Zweben A, COMBINE Study Research Group Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence — The COMBINE Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2003–2017. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th edition. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, D.C.: 2000. text revision. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cloninger CR. Neurogenetic adaptive mechanisms in alcoholism. Science. 1987;236:410–416. doi: 10.1126/science.2882604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Babor TF, Dolinsky ZS, Meyer RE, Hesselbrock M, Hofmann M, Tennen H. Types of alcoholics: concurrent and predictive validity of some common classification schemes. Br J Addict. 1992;87:1415–1431. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb01921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Babor TF, Hofmann M, DelBoca FK, Hesselbrock V, Meyer RE, Dolinsky ZS, Rounsaville B. Types of alcoholics, I. Evidence for an empirically derived typology based on indicators of vulnerability and severity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:599–608. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080007002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuckit MA, Tipp JE, Smith TL, Shapiro E, Hesselbrock VM, Bucholz KK, Reich T, Nurnberger JI., Jr An evaluation of type A and B alcoholics. Addiction. 1995;90:1189–1203. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.90911894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller WR, Marlatt GA. Manual for the comprehensive drinker profile. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson BA. Serotonergic agents and alcoholism treatment: rebirth of the subtype concept—an hypothesis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:1597–1601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lesch OM, Dietzel M, Musalek M, Walter H, Zeiler K. The course of alcoholism: long-term prognosis in different types. Forensic Sci Int. 1988;36:121–138. doi: 10.1016/0379-0738(88)90225-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lesch OM, Walter H. Subtypes of alcoholism and their role in therapy. Alcohol Alcohol Suppl. 1996;1:63–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG. Volume II: College students and adults ages 19–40. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Bethesda, MD: 2003. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clapp JD, Lange JE, Russell C, Shillington A, Voas RB. A failed norms social marketing campaign. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64:409–414. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson TF, Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts: findings from 4 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study surveys: 1993–2001. J Am Coll Health. 2002;50:203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hingson RW, Heeren T, Zakocs RC, Kopstein A, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63:136–144. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hingson R, Heeren T, Winter M, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24: changes from 1998 to 2001. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:259–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleming MF, Barry KL, MacDonald R. The alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) in a college sample. Int J Addict. 1991;26:1173–1185. doi: 10.3109/10826089109062153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kypri K, Langley JD, McGee R, Saunders JB, Williams S. High prevalence, persistent hazardous drinking among New Zealand tertiary students. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37:457–464. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/37.5.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bruner AB, Fishman M. Adolescents and illicit drug use. JAMA. 1998;280:597–598. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.7.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Apostolopoulos Y, Sönmez S, Yu CH. HIV-risk behaviours of American spring break vacationers: a case of situational disinhibition? Int J STD AIDS. 2002;13:733–743. doi: 10.1258/095646202320753673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Engs RC, Diebold BA, Hanson DJ. The drinking patterns and problems of a national sample of college students, 1994. J Alcohol Drug Educ. 1996;41:13–33. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Presley CA, Meilman PW, Cashin JR. Alcohol and drugs on American college campuses: use, consequences, and perceptions of the campus environment, Vol. IV: 1992-1994. Core Institute, Southern Illinois University; Carbondale, IL: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Presley CA, Pimentel ER. The introduction of the heavy and frequent drinker: a proposed classification to increase accuracy of alcohol assessments in postsecondary educational settings. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67:324–331. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muthén B, Shedden K. Finite mixture modeling with mixture outcomes using the EM algorithm. Biometrics. 1999;55:463–469. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hill KG, White HR, Chung IJ, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF. Early adult outcomes of adolescent binge drinking: person- and variable-centered analyses of binge drinking trajectories. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:892–901. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS. Another look at heavy episodic drinking and alcohol use disorders among college and noncollege youth. J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65:477–488. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Slutske WS. Alcohol use disorders among US college students and their noncollege-attending peers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:321–327. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knight JR, Wechsler H, Kuo M, Seibring M, Weitzman ER, Schuckit MA. Alcohol abuse and dependence among U.S. college students. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63:263–270. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin CS, Kaczynski NA, Maisto SA, Bukstein OM, Moss HB. Patterns of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence symptoms in adolescent drinkers. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56:672–680. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jennison KM. The short-term effects and unintended long-term consequences of binge drinking in college: a 10-year follow-up study. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30:659–684. doi: 10.1081/ada-200032331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Neill SE, Parra GR, Sher KJ. Clinical relevance of heavy drinking during the college years: cross-sectional and prospective perspectives. Psychol Addict Behav. 2001;15:350–359. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.4.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grant BF, Kaplan K, Shepard J, Moore T. Source and Accuracy Statement for Wave 1 of the 2001–2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Bethesda, MD: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1097–1106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lynskey MT. The comorbidity of alcohol dependence and affective disorders: treatment implications. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;52:201–209. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang J, El-Guebaly N. Sociodemographic factors associated with comorbid major depressive episodes and alcohol dependence in the general population. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49:37–44. doi: 10.1177/070674370404900106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McEachin RC, Keller BJ, Saunders EF, McInnis MG. Modeling gene-by-environment interaction in comorbid depression with alcohol use disorders via an integrated bioinformatics approach. BioData Min. 2008;1:2. doi: 10.1186/1756-0381-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blow FC, Barry KL. Use and misuse of alcohol among older women. Alcohol Res Health. 2002;26:308–315. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Merikangas KR, Gelernter CS. Comorbidity for alcoholism and depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1990;13:613–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thase ME, Salloum IM, Cornelius JD. Comorbid alcoholism and depression: treatment issues. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 20):32–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hemby SE, Johnson BA, Dworkin SI. In: Neurobiological basis of drug reinforcement, in Drug addiction and its treatment: nexus of neuroscience and behavior. Johnson BA, Roache JD, editors. Lippincott-Raven; Philadelphia: 1997. pp. 137–169. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson BA. New weapon to curb smoking: no more excuses to delay treatment. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1547–1550. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.15.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson BA. Update on neuropharmacological treatments for alcoholism: scientific basis and clinical findings. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75:34–56. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koob GF, Le Moal M. Plasticity of reward neurocircuitry and the `dark side' of drug addiction. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1442–1444. doi: 10.1038/nn1105-1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Bethesda, MD: Helping patients who drink too much: a clinician's guide, updated 2005 edition. 2005 NIH Publication No. 07-3769.

- 50.Reinert DF, Allen JP. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): a review of recent research. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:272–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miller WR, Heather N, Hall W. Calculating standard drink units: international comparisons. Br J Addict. 1991;86:43–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb02627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shank RP, Gardocki JF, Streeter AJ, Maryanoff BE. An overview of the preclinical aspects of topiramate: pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, and mechanism of action. Epilepsia. 2000;41(suppl 1):S3–S9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Johnson BA, Ait-Daoud N, Bowden CL, DiClemente CC, Roache JD, Lawson K, Javors MA, Ma JZ. Oral topiramate for treatment of alcohol dependence: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:1677–1685. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13370-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Johnson BA, Rosenthal N, Capece JA, Wiegand F, Mao L, Beyers K, McKay A, Ait-Daoud N, Anton RF, Ciraulo DA, Kranzler HR, Mann K, O'Malley SS, Swift RM, Topiramate for Alcoholism Advisory Board, Topiramate for Alcoholism Study Group Topiramate for treating alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298:1641–1651. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.White HS, Brown SD, Woodhead JH, Skeen GA, Wolf HH. Topiramate modulates GABA-evoked currents in murine cortical neurons by a nonbenzodiazepine mechanism. Epilepsia. 2000;41(suppl 1):S17–S20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Johnson BA. Recent advances in the development of treatments for alcohol and cocaine dependence: focus on topiramate and other modulators of GABA or glutamate function. CNS Drugs. 2005;19:873–896. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200519100-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Johnson BA, Rosenthal N, Capece JA, Wiegand F, Mao L, Beyers K, McKay A, Ait-Daoud N, Addolorato G, Anton RF, Ciraulo DA, Kranzler HR, Mann K, O'Malley SS, Swift RM, Topiramate for Alcoholism Advisory Board, Topiramate for Alcoholism Study Group Improvement of physical health and quality of life of alcohol-dependent individuals with topiramate treatment. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1188–1199. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.11.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cruz HG, Ivanova T, Lunn ML, Stoffel M, Slesinger PA, Lüscher C. Bidirectional effects of GABA(B) receptor agonists on the mesolimbic dopamine system. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:153–159. doi: 10.1038/nn1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Addolorato G, Leggio L, Ferrulli A, Cardone S, Vonghia L, Mirijello A, Abenavoli L, D'Angelo C, Caputo F, Zambon A, Haber PS, Gasbarrini G. Effectiveness and safety of baclofen for maintenance of alcohol abstinence in alcohol-dependent patients with liver cirrhosis: randomised, double-blind controlled study. Lancet. 2007;370:1915–1922. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61814-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Addolorato G, Leggio L, Abenavoli L, Agabio R, Caputo F, Capristo E, Colombo G, Gessa GL, Gasbarrini G. Baclofen in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome: a comparative study vs diazepam. Am J Med. 2006;119:276.e13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.New Zealand Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Authority (MEDSAFE) Alpha-baclofen. 1999 Data sheet, http://www.medsafe.govt.nz/profs/datasheet/a/alphabaclofentab.htm. [PubMed]

- 62.Blazer DG, Wu LT. The epidemiology of at-risk and binge drinking among middle-aged and elderly community adults: National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:1162–1169. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cornelius JR, Salloum IM, Ehler JG, Jarrett PJ, Cornelius MD, Perel JM, Thase ME, Black A. Fluoxetine in depressed alcoholics: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:700–705. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830200024004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Krishnan-Sarin S, Krystal JH, Shi J, Pittman B, O'Malley SS. Family history of alcoholism influences naltrexone-induced reduction in alcohol drinking. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:694–697. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. Brief alcohol screening and intervention for college students (BASICS): a harm reduction approach. Guilford Press; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ait-Daoud N, Malcolm RJ, Jr, Johnson BA. An overview of medications for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal and alcohol dependence with an emphasis on the use of older and newer anticonvulsants. Addict Behav. 2006;31:1628–1649. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Blume AW, McKnight P, Marlatt GA. Brief intervention for heavy-drinking college students: a 4-year follow-up and natural history. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1310–1316. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ait-Daoud N, Johnson BA. In: Medications for the treatment of alcoholism, in Handbook of clinical alcoholism treatment. Johnson BA, Ruiz P, Galanter M, editors. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore, MD: 2003. pp. 119–130. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Harris BR, Prendergast MA, Gibson DA, Rogers DT, Blanchard JA, Holley RC, Fu MC, Hart SR, Pedigo NW, Littleton JM. Acamprosate inhibits the binding and neurotoxic effects of trans-ACPD, suggesting a novel site of action at metabotropic glutamate receptors. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:1779–1793. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000042011.99580.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.George DT, Gilman J, Hersh J, Thorsell A, Herion D, Geyer C, Peng X, Kielbasa W, Rawlings R, Brandt JE, Gehlert DR, Tauscher JT, Hunt SP, Hommer D, Heilig M. Neurokinin 1 receptor antagonism as a possible therapy for alcoholism. Science. 2008;319:1536–1539. doi: 10.1126/science.1153813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brower KJ, Myra Kim H, Strobbe S, Karam-Hage MA, Consens F, Zucker RA. A randomized double-blind pilot trial of gabapentin versus placebo to treat alcohol dependence and comorbid insomnia. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:1429–1438. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00706.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Anton RF, Kranzler H, Breder C, Marcus RN, Carson WH, Han J. A randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of aripiprazole for the treatment of alcohol dependence. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28:5–12. doi: 10.1097/jcp.0b013e3181602fd4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kiefer F, Jahn H, Tarnaske T, Helwig H, Briken P, Holzbach R, Kampf P, Stracke R, Baehr M, Naber D, Wiedemann K. Comparing and combining naltrexone and acamprosate in relapse prevention of alcoholism: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:92–99. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Oslin DW, Berrettini W, Kranzler HR, Pettinati H, Gelernter J, Volpicelli JR, O'Brien CP. A functional polymorphism of the mu-opioid receptor gene is associated with naltrexone response in alcohol-dependent patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1546–1552. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Anton RF, Oroszi G, O'Malley S, Couper D, Swift R, Pettinati H, Goldman D. An evaluation of mu-opioid receptor (OPRM1) as a predictor of naltrexone response in the treatment of alcohol dependence: results from the Combined Pharmacotherapies and Behavioral Interventions for Alcohol Dependence (COMBINE) study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:135–144. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.2.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gelernter J, Gueorguieva R, Kranzler HR, Zhang H, Cramer J, Rosenheck R, Krystal JH, VA Cooperative Study #425 Study Group Opioid receptor gene (OPRM1, OPRK1, and OPRD1) variants and response to naltrexone treatment for alcohol dependence: results from the VA Cooperative Study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:555–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Arias AJ, Armeli S, Gelernter J, Covault J, Kallio A, Karhuvaara S, Koivisto T, Mäkelä R, Kranzler HR. Effects of opioid receptor gene variation on targeted nalmefene treatment in heavy drinkers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:1159–1166. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00735.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lesch KP, Greenberg BD, Higley JD. In: Serotonin transporter, personality, and behavior: toward dissection of gene-gene and gene-environment interaction, in Molecular genetics and the human personality. Benjamin J, Ebstein RP, Belmaker RH, editors. American Psychiatric Publishing; Washington, D.C.: 2002. pp. 109–136. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Heils A, Teufel A, Petri S, Stober G, Riederer P, Bengel D, Lesch KP. Allelic variation of human serotonin transporter gene expression. J Neurochem. 1996;66:2621–2624. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66062621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Heils A, Mossner R, Lesch KP. The human serotonin transporter gene polymorphism—basic research and clinical implications. J Neural Transm. 1997;104:1005–1014. doi: 10.1007/BF01273314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ait-Daoud N, Roache JD, Dawes MA, Liu L, Wang X-Q, Javors MA, Seneviratne C, Johnson BA. Can serotonin transporter genotype predict craving in alcoholism? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:1329–1335. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00962.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kenna GA, Zywiak WH, McGeary JE, Leggio L, McGeary C, Wang S, Grenga A, Swift RM. A within-group design of nontreatment seeking 5-HTTLPR genotyped alcohol-dependent subjects receiving ondansetron and sertraline. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:315–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00835.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]