SUMMARY

This article describes a family-based HIV prevention and mental health promotion program specifically designed to meet the needs of perinatally-infected preadolescents and their families. This project represents one of the first attempts to involve perinatally HIV-infected youth in HIV prevention efforts while simultaneously addressing their mental health and health care needs. The program, entitled CHAMP+ (Collaborative HIV Prevention and Adolescent Mental Health Project-Plus), focuses on: (1) the impact of HIV on the family; (2) loss and stigma associated with HIV disease; (3) HIV knowledge and understanding of health and medication protocols; (4) family communication about puberty, sexuality and HIV; (5) social support and decision making related to disclosure; and (6) parental supervision and monitoring related to sexual possibility situations, sexual risk taking behavior and management of youth health and medication. Findings from a preliminary evaluation of CHAMP+ with six families are presented along with a discussion of challenges related to feasibility and implementation within a primary health care setting for perinatally infected youth.

Keywords: Perinatally-infected preadolescents and their families, family communication, challenges with feasibility and implementation, parental supervision and monitoring, social support and decision making

As a result of improvements in HIV medical treatment, increasing numbers of perinatally-infected children are surviving into adolescence and beyond. Yet these youth continue to live with a stigmatizing, still potentially fatal, chronic illness (Havens, Mellins, & Hunter, 2002; Lindegern, 2001; Grosz, 2001). They must cope with the numerous health care demands of the illness as well as the effect of HIV on normative developmental processes, including puberty, growth, peer relations, and sexuality. Furthermore, given the epidemiology of pediatric HIV, the majority of perinatally infected children are born into families who have struggled with poverty, inner-city stressors, drug use, and often previous loss due to parental HIV. Thus, this is a population at high risk for poor behavioral and mental health outcomes.

To date, few studies have examined the emotional and behavioral sequelae of perinatal HIV infection in older youth, although a few studies indicate that younger children present with high rates of mental health problems (Havens, Whitaker, Ehrhardt et al., 1994; Mellins et al., 2003) and clinical reports indicate that as perinatally HIV-infected children reach adolescence, sexual behavior and substance use emerge as significant issues (Ledlie, 2000; Havens and Ng, 2001). Involvement in sexual and drug risk taking behavior not only threatens the safety and well being of the HIV-infected child, but also poses a significant public health threat for transmission of the virus. Corresponding with the limited literature on behavioral outcomes of perinatal HIV infection, few efficacy-based interventions have been developed to decrease risk taking behavior and improve the mental health and well-being of perinatally HIV-infected youth and their families.

This article describes a family-based HIV prevention and mental health promotion program specifically designed to meet the needs of perinatally-infected preadolescents and their families. The process by which youth, adult caregivers, health care providers and HIV prevention scientists came together to adapt an existing evidence-based HIV prevention program will be detailed here. Issues specific to this population, including HIV as a stigmatizing disease, communication about HIV within and outside the family, adherence to medical treatment, child and parental mental health issues, are discussed. The preliminary impact of the program and related feasibility and implementation challenges are presented and next steps for research and program development are detailed.

NEED FOR PSYCHOSOCIAL INTERVENTIONS FOR PERINATALLY HIV-INFECTED YOUTH

Pediatric HIV

Nationally, more than 13,502 children less than 13 years of age are living with HIV infection (CDC, 2000) with the vast majority of these children exposed perinatally and growing up in inner city environments, such as New York City (NYC). Corresponding with the epidemiology of HIV disease in women, the majority of HIV-infected children in NYC are African American (55%) and Latino (35%), living in poverty, and affected by parental substance use (NYC DOH, 2004). Fortunately, antiretroviral therapies, when used effectively during pregnancy and the birth process, have significantly diminished the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (Cooper, 2002), virtually eradicating pediatric HIV for future generations. However, use of HIV antiretrovirals, as well as other medications that prevent opportunistic infections has resulted in decreased morbidity and mortality for children with established HIV disease (De Martino, 2000; Epstein, Little, & Richman, 2000). Thus, increasing numbers of perinatally infected children are surviving into their teens and beyond, yet needing to incorporate a stigmatizing, chronic illness into their development and transition through adolescence.

Stigma Associated with Perinatal HIV Infection and Disclosure

Perinatally infected adolescents must confront the social ramifications of having a chronic stigmatized disease. Complicating their adjustment is the fact that many youth are not told about their illness until they enter their second decade of life (Mellins et al., 2002; Wiener, Battles, & Heilman, 1998). Caregivers are often afraid of the negative consequences of disclosure including child distress, child anger at parent for infecting them, and inappropriate disclosure to others (Havens, Mellins, Pilowsky, 1996; Mellins et al., 2002). For youth who do know their diagnosis, there are complicated decisions related to disclosure of serostatus that may impact friendships, relationships with sexual partners, and the risk for HIV transmission. For HIV-infected children, caregiver concerns about disclosure of child HIV status to the child may be one of the most significant barriers to adequate parent-child communication around sexuality, drug use, and adherence. Limited parent-child communication is of concern given that several studies have found that youth with more frequent and open parent-child communication have better psychological adjustment, (Amerikaner, Monks, Wolfe, & Thomas, 1995) as well as delayed sexual activity, fewer partners, and more use of contraception (Baumeister, Flores, & Marin, 1995; Fox & Inazu, 1980; Klein & Gordon, 1990; Kotchick et al., 1999; Miller et al., 1998; O’Sullivan et al., 1999; Pick & Palos, 1997).

Antiretroviral Adherence

To achieve viral suppression, combination antiretroviral therapy often requires multiple daily doses of three or more medications over an indefinite period. These therapies have created challenges for both youth as well as their adult caregivers (Mellins et al., 2003; Chesney et al., 2000), Adherence has emerged as a major treatment obstacle. Pediatric adherence is complicated by issues of volume, taste, and repeated, potentially unpleasant, child-caregiver encounters related to adherence. HIV-infected youth frequently have irregular daily schedules due to school, after-school activities, and medical appointments. This, coupled with the desire to lead as normal a life as possible may make it very difficult for youth to adhere to strict medication regimens. In addition, there are numerous adherence challenges for the adult caregivers of these youth including remembering frequent doses, accurately identifying varied pills and liquids, integrating multiple medications into daily activities, and maintaining privacy (Byrne et al., 2002).

Unfortunately, even brief episodes of non-adherence to ART can permanently undermine treatment and lead to reduced efficacy of and increased resistance to medications (Patterson et al., 2000). In addition, many older perinatally-infected children, during early days of antiretroviral treatment, received monotherapy before the importance of combination treatment was understood. Thus, many perinatally infected adolescents are living with multidrug resistant HIV that, not only impairs the health of the youth, but can also be transmitted to others through sexual and drug use behaviour. This grim reality becomes a serious public health issue as youth approach adolescence, a time of increased experimentation with sexual behavior and drug use. For HIV-infected youth, engaging in any type of risk behavior increases opportunities for transmission of HIV (including ART-resistant strains of the virus) to others. The fact that perinatally infected children are now becoming adolescents in relatively large numbers presents a public health concern that warrants immediate attention, particularly in NYC, home to over 20% of the HIV-infected women and children in the U.S. (Centers for Disease Control, 2002; NYC Department of Health, 2002).

Mental Health Needs and Functioning of Perinatally Infected Children

Studies of children with other chronic debilitating diseases have shown increased rates of mental health problems, including depression or social withdrawal (Abrams, 1990; Grosz, 2001; Havens, 2001; Mellins, 2001). Perinatally HIV infected youth may be at particularly high risk for mental health problems given the high rates of co-morbid mental health and substance use disorders in HIV-infected women, the potential inheritability of these disorders, and the stressful family and social environments often associated with parental mental illness and substance abuse (Havens, Mellins, & Ryan, 1997). Clinical reports indicate that adolescents with perinatal HIV infection are presenting with: (1) serious mental health difficulties, including mood, anxiety, and behavioral problems, and (2) high-risk sexual behaviors and substance use (Abrams, 1990; Grosz, 2001; Havens, 2001; Mellins, 2001). Furthermore, emotional and behavioral difficulties, including social problems, anxiety, depression, as well as other disorders associated with impulse control problems and affective dysregulation, potentially related to the neurological and cognitive sequelae of HIV, have been found in 12 to 44% of younger HIV-infected children (Abrams & Nicholas, 1990; Corsi et al., 1991; Mellins et al., 2003; Tardieu et al., 1995).

In summary, the potential for stigma and disclosure issues, difficulties with adherence to multiple medications, and mental health problems may place HIV-infected youth at high-risk for multiple behavioral difficulties as they age. However, the authors know of no efficacy-based interventions that target the unique needs of perinatally HIV-infected youth and their families, as the youth approach adolescence. Thus, the authors developed a new program, CHAMP+ (Collaborative HIV Prevention and Mental Health Project-Plus), based on models of family-based prevention developed for other populations of inner city adolescents. The program and preliminary evaluation of CHAMP+ presented here is an important opportunity to further understand the needs of perinatally infected youth and their families and examine issues related to feasibility, implementation, and impact, of prevention programs that target unique risk factors and attempt to bolster protective influences in this population.

DEVELOPMENT OF CHAMP+

The Original CHAMP Model and Consumer Involvement

The Collaborative HIV-Prevention and Adolescent Mental Health Family Program (CHAMP) served as a template for the intervention developed for perinatally HIV-infected youth, CHAMP+. The original CHAMP Family Program was developed in response to the increasing need to reduce urban adolescent HIV exposure in inner-city populations. CHAMP’s original goal was to increase understanding of sexual development and HIV risk within the urban context, while applying that understanding of development to an intervention program (Paikfoff, 1997; McKay et al., 2000). The content and structure of the CHAMP Family Program were influenced by research findings and a collaborative partnership. A longitudinal study conducted with 315 urban, African American early adolescents and their families provided the empirical basis and conceptual framework for the intervention (Paikoff, 1997). In addition, the development of the CHAMP intervention program was shaped by a collaborative partnership between urban community parents, school staff, and university-based researchers.

Creating culturally sensitive interventions through collaboration with consumers is necessary in light of increasing evidence that HIV prevention programs designed for urban minority youth have faced significant obstacles to involving participants (Dalton, 1989; Gustafson et al., 1992; Stevenson & White, 1994). Specifically, Stevenson and White (1994) identified obstacles to the implementation of HIV prevention programs that include: (1) denial of the epidemic in minority communities related to stigma; (2) distrust of majority cultural institutions; and (3) myths/beliefs regarding AIDS contraction, transmission and origin. Also, cultural concerns arise when research on health problems that disproportionately affect minority communities are investigated by “outsiders” (Dalton, 1989; Thomas & Quinn, 1991). Involving consumers in research can effectively help researchers address many of these issues (Hatch et al., 1993; Madison et al., in press). One particularly effective model is to have community members take a driving role, with research staff to develop programs of research and services to meet consumer needs (Hatch et al., 1993). This model was used in the development of the original CHAMP family program. More specifically, consumers and health care providers were integrally involved in the program’ in its design, oversight and preliminary testing.

The primary goals of the original CHAMP Family Program curriculum are to: (1) foster discussion of sexual possibility situations; (2) make links between family processes and children’s participation in sexual possibility situations (in particular, stressing family communication, rule setting, monitoring, support, and provision of clear values); and (3) increase care-giver and youth understanding of puberty and HIV/AIDS in order to prepare families for the coming changes of adolescence. CHAMP is delivered via multi-level group modalities, which include both multiple family sessions and parent/child group sessions (McKay et al., 2000; Madison, McKay et al., 2000).

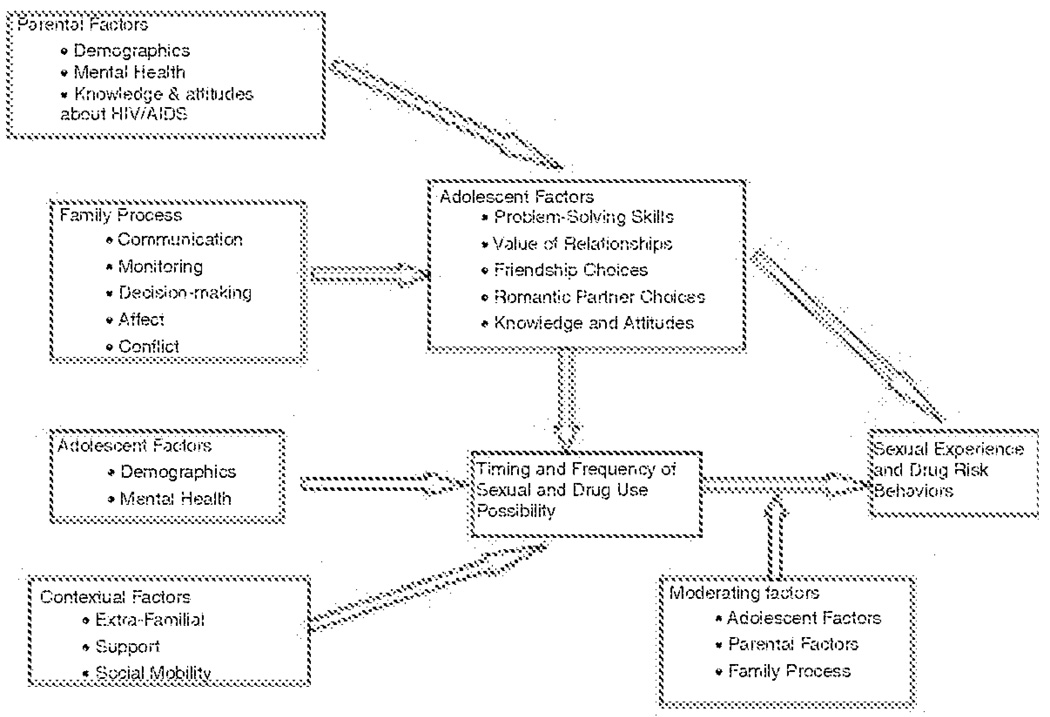

Given the goals of promoting communication and support both within and between families, the idea of combining families into groups is a logical format for program delivery. In addition to entire family needs, however, children and parents within families have individual needs as well. For parents, these needs include support from other parents, and frank discussion of strategies for supervision and monitoring, as well as chances to discuss information and communication strategies separately from their children. For children, these needs include developing peer supports, as well as social problem skills to assist in recognizing different types of risk situations, and negotiation/self-assertion skills to deal with such situations. Thus, a combination of multiple family sessions and parent/child sessions are used. Based upon the previous research related to risk and protective influences for urban youth, as well as findings from the CHAMP Family Study (see Paikoff, 1997 for summary), a theoretical model guiding the development of the original CHAMP Family Program was created (see Figure 1). In depth descriptions of the CHAMP model, program, and preliminary results of large clinical trials evaluations have been presented elsewhere (see Madison et al., 2000; McKay, Chasse et al.; 2004).

FIGURE 1.

CHAMP Family Program Theoretical Model

Creating CHAMP+ Curriculum

A collaboration was forged between HIV-infected early adolescents, their adult caregivers, pediatric HIV primary care providers, and university-based HIV prevention scientists in order to adapt the CHAMP Family Program to address the complex needs of children with perinatally-acquired HIV. The collaborative partnership took place in 2002 at an urban pediatric AIDS center, Harlem Hospital Center, an area that especially mirrors the complexities of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in NYC. Following the model of consumer involvement used in previous adaptations of CHAMP, consumers (five caregivers of perinatally HIV-infected youth and three HIV+ teenagers) met with university-based research staff for a period of six months to: (1) identify salient issues related to HIV, family life, and youth development and risk; (2) review existing CHAMP Family Program to assess appropriateness of content, format, etc:, and (3) develop new intervention content based upon perceived needs. Simultaneously, research staff met with HIV health care providers at the hospital to gather input related to programmatic content and feasibility of integrating a test of CHAMP+ into the hospital’s service delivery system. These health care providers have worked with the families they serve for 10–12 years and are, therefore, very familiar with the strengths and needs of the families.

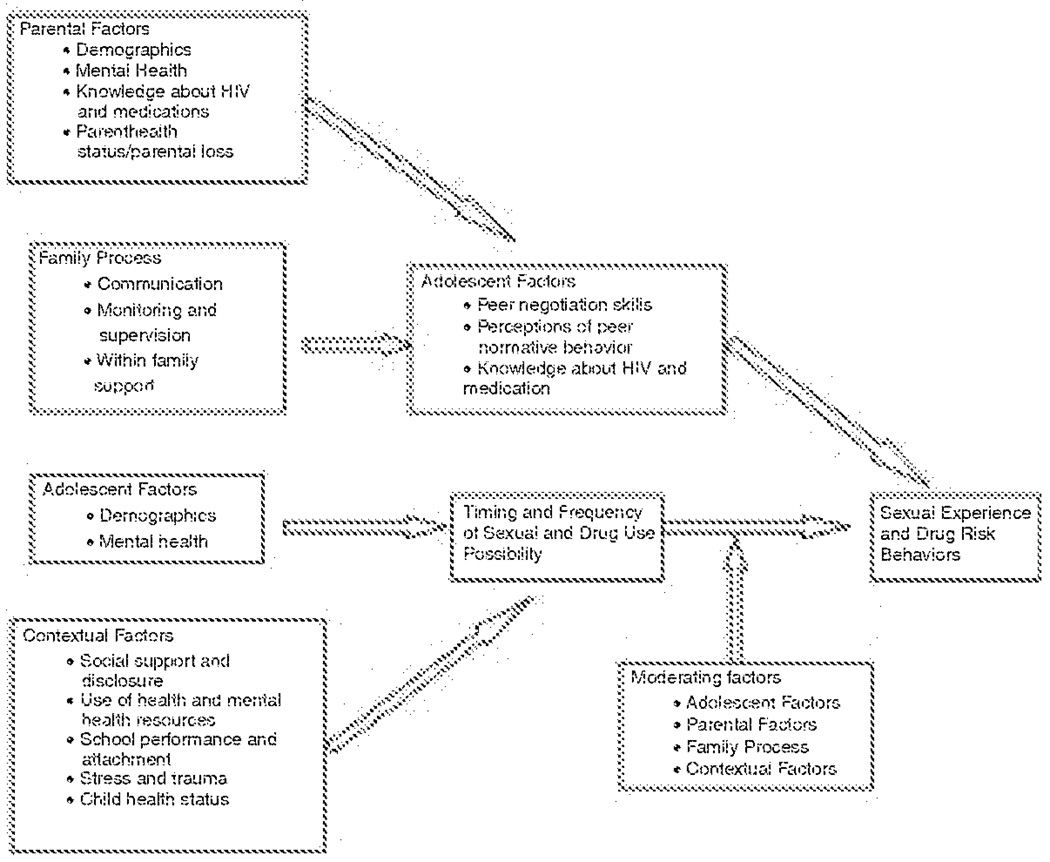

Information gathered from the collaborative partnership, including the constant involvement of consumers, was critical to the adaptation and development of CHAMP into the new intervention program. Although the format of the original CHAMP program was maintained, additional sessions were added to CHAMP+ and changes were made to programmatic content. Key changes that were made to the CHAMP theoretical model and program include consideration of: (1) the impact of HIV on the family; (2) loss and stigma associated with HIV disease; (3) HIV knowledge and understanding of health and medication protocols; (4) family communication about puberty, sexuality and HIV; (5) social support and decision making related to disclosure; (6) parental supervision and monitoring related to sexual possibility situations and sexual risk taking behavior; and (7) parental supervision related to helping youth manage their health and medication. CHAMP+ programmatic content was also revised to encompass family level issues such as death of a parent or HIV status of the parent. Key changes were then made to the CHAMP theoretical model (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

CHAMP+ Theoretical Model

CHAMP+ Family Curriculum and Program

CHAMP+ aims to intervene with families by targeting specific child, parent, and family factors within the context of HIV. The program relies on theories of community collaboration while also utilizing a strength and family-based approach. The goal of the program is to increase family communication while creating an environment that supports and encourages families to raise healthy children.

The family-based curriculum focuses on communication skills, relationship maintenance skills (negotiation and refusal skills), social support, and HIV education. Children and caregivers learn these skills by participating in a variety of interactive activities, discussions, role-plays, and games, etc. The curriculum is appropriate for both youth and caregivers; it is developmentally appropriate for preadolescent HIV-infected children, and also appropriate for the varied caregiver/child relationships (i.e., biological, kin, or adoptive caregivers).

CHAMP+ PILOT STUDY

Methods

Setting

The CHAMP+ Family Program was pilot-tested over 10, two-hour sessions at Harlem Hospital’s Family Care Center. The sample included children receiving their HIV primary care at Harlem Hospital’s Family Care Center and their respective caregivers. The Family Care Center at Harlem Hospital is a comprehensive care and research program that has been providing multidisciplinary medical, psychological, and social services to HIV-infected and affected children and their families since 1986. Currently there are approximately 130 children, ages newborn to 21 years of age, who are infected with HIV/AIDS in care. The populations reflect the larger population of perinatally HIV-infected children in NYC (NYC Department of Health HIV/AIDS Surveillance, 2003).

Recruitment

Families were recruited based on the study’s eligibility requirements. In order to participate in the CHAMP+ Family Program, caregivers had to be the legal guardian of the child, the biological or adoptive caregiver of the child, and had to have lived with the child for at least one year prior to study commencement. Child eligibility requirements included that the child received his/her HIV primary care at Harlem Hospital Center and that the child had been disclosed his/her HIV+ status prior to study commencement. A total of six families (n = 6 care-giver/child dyads), or 12 participants, were recruited for the CHAMP+ Family Program pilot study. However, one family (caregiver and HIV+ girl) decided not to participate because of the time commitment.

Gender

Although gender was not an inclusion/exclusion criteria, all child participants (n = 5) were male. They were nine to 12 years of age, African American, infected with perinatal HIV, and had been told about their diagnosis. Again, gender was not an inclusion/exclusion criteria, but all caregiver participants (n = 5) were female. They were 39 to 70 years of age, African American, and either the biological (n = 3) or adoptive (n = 2) caregiver of the child. During the introductory intervention session, all participants signed written consent forms informing them of the research study, the possible benefits and risks to participating, and confidentiality. Both the program and debriefing exit-interview (see below) received Institutional Review Board approval.

Procedures

In order to examine issues raised and modifications made to the program during implementation, process notes were taken during sessions by a trained observer. A debriefing exit-interview was developed to evaluate the effectiveness of the CHAMP+ Family Program. A trained graduate student administered the confidential individual interview questionnaires to all child and caregiver participants post-intervention within 2 weeks. Exit interviews consisted of a series of structured questions using Likert scales, as well as a number of qualitative questions assessing issues of program feasibility, participant satisfaction, and perceptions of family change (see Appendix, Exit Interview Questions). Qualitative process notes were collected throughout the planning and implementation phases of the intervention, while in depth qualitative interviews and standardized questionnaires were administered to all participants at the completion of the pilot intervention.

APPENDIX.

Exit Interview

| (1) Since participating in CHAMP+ how connected or close do you feel to your child/caregiver? | ||

| Closer | About the same | Not close |

| (2) Since participating in CHAMP+, do you feel that the level of communication with your child/caregiver has changed? | ||

| More communication | No change | Less communication |

| (3) Since participating in CHAMP+, how comfortable do you feel discussing topics such as puberty? | ||

| More comfortable | The same | Less comfortable |

| (4) Since participating in CHAMP+, how comfortable do you feel discussing topics such as HIV? | ||

| More comfortable | The same | Less comfortable |

| (5) Since participating in CHAMP+, how comfortable do you feel discussing topics such as sex? | ||

| More comfortable | The Same | Less comfortable |

| (6) Since participating in CHAMP+, how confident are you that you can ask medical staff a question re: your/child’s HIV? | ||

| More confident | The same | Less confident |

| (7) Since participating in CHAMP+, how confident do you feel that you can initiate a conversation with you caregiver/child if there is something you want to talk about? | ||

| More confident | The same | Less confident |

| (8) Since participating in CHAMP+ how connected or close do you feel to your family? | ||

| Closer | About the same | Not close |

| (9) Since participating in CHAMP+, how connected or close do you feel to other CHAMP+ participants? | ||

| Closer | About the same | Not close |

| (10) Since participating in CHAMP+, how connected or close do you feel to CHAMP+ facilitators? | ||

| Closer | About the same | Not close |

| (11) Since participating in CHAMP+, how connected or close do you feel to the medical staff at Harlem Hospital? | ||

| Closer | About the same | Not close |

Content analysis involved two raters, trained in qualitative data analysis, separately reviewing process notes and exit interviews to identify (a) barriers to participation, (b) deviation from original CHAMP+ material, (c) perceptions of family change, and (d) “lessons learned.” The first step in qualitative data analysis was to identify the most prominent themes that could reliably be identified by the two raters. The raters reviewed all process notes and qualitative data from the exit interviews and marked phrases and paragraphs containing material relevant to the aims of the process evaluation. Themes were distinguished within those topics and used to develop a coding nomenclature for each question. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus discussion; final codes resulting from that process were then assigned. This coding nomenclature then was used by both raters separately to review and to code all of the qualitative data (process notes and qualitative exit interview questions). The level of rater coding agreement was 88.3%, denoting excellent reproducibility (Rosner, 2000).

Results

The process evaluation of the CHAMP+ Family Program pilot study suggests that overall, the participants perceived their involvement as beneficial. Study findings, based on participants’ perception of change as detailed in the post-intervention exit interviews and process notes, showed enhancement of the caregiver/child relationship, increased communication, increased participant self-efficacy regarding family communication, and social network expansion with others affected by HIV. Specific findings are presented below.

Participant Satisfaction

Caregiver/Child Relationship

Results from the exit interviews revealed that 80% (n = 8) of participants felt “closer or more connected” to their caregiver or child after participating in the CHAMP+ Family Program, Results in this section are based on responses to structured questions where participants chose from a Likert scale (see Appendix, Exit Interview Questions). Qualitative findings from the exit interviews also showed that caregivers and children felt more connected after participating in the intervention program, as noted in the following quote from an HIV+ mother:

[CHAMP+] helped me to get to know my son more and the issues he has. I loved it. My son and I have gotten even closer since [the program].–HIV+ mother

Communication

After participating in CHAMP+, 60% (n = 6) of participants reported that the level of communication with their care-giver or child had increased (see Appendix, exit interview question two). For example, during the second CHAMP+ intervention session, caregivers spoke about wanting to “snoop” in order to know what was going on in their child’s life. However, by the last intervention session it was evident that caregivers were communicating directly with their children instead of “snooping” to gain information. The majority of participants reported feeling more comfortable discussing sensitive topics with their caregiver or child such as puberty (70%, n = 7), HIV (60%, n = 5), and sex (50%, n = 5). See Appendix, exit interview questions three, four, and five. Qualitative findings from the exit interviews and process notes also revealed that CHAMP+ increased participants’ level of perceived communication:

Communication is definitely a plus, especially for mothers who don’t know what or how to ask.–Caregiver participant

I got to express myself.–HIV+ boy

We can talk about those ‘boy things’ now and he won’t get upset, just laughs.–HIV+ mother

Self-Efficacy Regarding Communication

Study findings revealed increased self-efficacy among participants in their ability to ask questions or initiate conversation. After participating in CHAMP+, the majority of participants reported feeling more confident that they could ask medical staff an HIV-related question (80%, n = 8). The majority of participants also reported feeling more confident that they could initiate a conversation with their respective caregiver or child if there was something they wanted to talk about (80%, n = 8). See Appendix, exit interview questions six and seven. Qualitative findings from the exit interviews also showed increased self-efficacy among participants. For example:

He’s talking more and asks questions about certain things, where-as in the past he wouldn’t ask.–HIV+ mother

Social Network Expansion

After participating in CHAMP+, participants perceived that their social network with others affected by HIV had expanded. Results from the exit interviews revealed that participants felt “closer or more connected” to their family (40%, n = 4) and other CHAMP+ participants (70%, n = 7). See Appendix, exit interview questions eight and nine. Findings also showed social network expansion with others affected by HIV among participants:

[The other kids in CHAMP+] all have the same thing, and they know what I mean.–HIV+ boy

Its part of a comfortability–We can talk more now and he knows that [other participants] are going through the same things we are, he sees how other moms react.–HIV+ mother

Results from the exit interviews also revealed that participants felt “closer or more connected” to CHAMP+ facilitators (80%, n = 8) and the medical staff at Harlem Hospital (80%, n = 8) (see Appendix, exit interview questions 10 and 11). In order to minimize conflict of interest and social desirability of participant response, CHAMP+ staff members were comprised of non-medical personnel. This allowed participants to speak freely without worrying about jeopardizing their child’s healthcare. One HIV+ caregiver spoke of the mistrust she felt towards the establishment where she routinely received her medical care:

Have you ever had a doctor tell you like [CHAMP+ facilitator] just did? No, they never give you stats or tell you options. They only tell you to take the regiment.–HIV+ caregiver

In conclusion, the exit interview, administered to all participants post-intervention, and the process notes revealed quantitative and qualitative findings related to perceptions of family change and issues related to participant satisfaction.

This group is ringing chimes in my head–been doing good–asking questions.–Adoptive caregiver

It really helped me a lot. Things I would never have thought about, it made me think of.–Adoptive caregiver

After school he would always ask, Mommy are we going today?–Adoptive caregiver

Yeah, feeling better about myself.–HIV+ boy

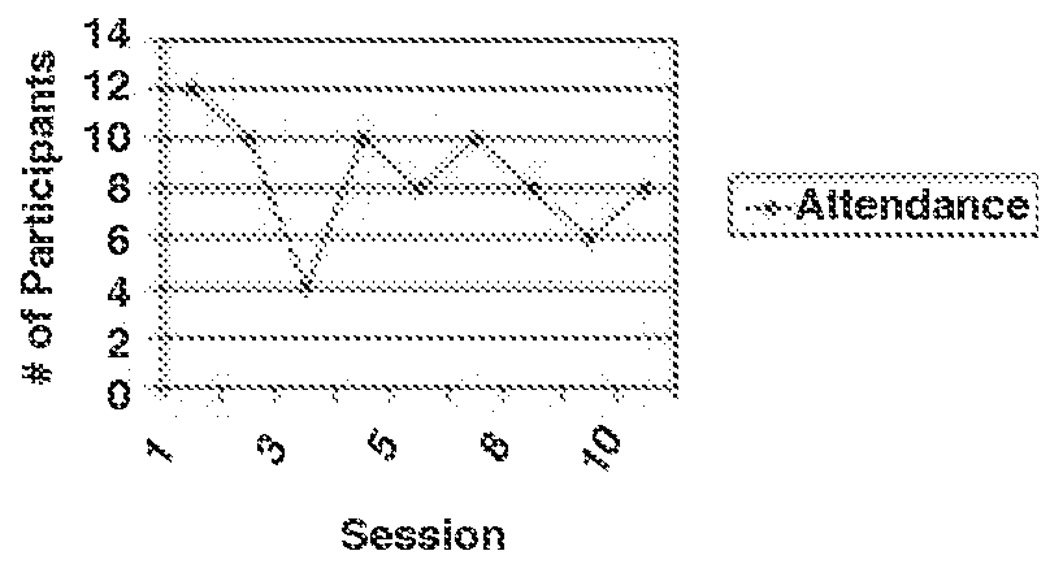

Barriers to Participation

Content analysis of the process notes revealed specific barriers to participation in the intervention. Obstacles included both personal and programmatic barriers which are detailed below. It is important to emphasize, however, that even though feasibility related barriers were identified during the CHAMP+ pilot, they did not appear to severely impact participation of families involved in the pilot. As Figure 3 evidences, with the exception of session #3, during which a serious snow storm occurred, family participation rates remained quite high throughout the implementation of the CHAMP+ program. Records of attendance at CHAMP+ Family Program intervention sessions indicated an attendance rate of: session one (n = 12), session two (n = 10), session three (n = 4), session four (n = 10), session five (n = 8), session six (n = 10), session seven (n = 10), session eight (n = 8), session nine (n = 6), and session 10 (n = 8).

FIGURE 3.

CHAMP+ Pilot Test Participant Attendance

Participant Personal Barriers

Participant personal barriers to participation included issues related to impaired adolescent and caregiver health, time commitment (a total of six families were recruited, but one chose not to participate due to too big a time commitment), caregiver personal needs, and family health. Given the sub-optimal health status of this population, it was not surprising that impaired health proved to be the most frequent personal barrier to participation in the CHAMP+ Family Program.

Programmatic Barriers

During preparation for the CHAMP+ pilot study, a focused series of meetings between members of the investigative team and health care staff (physicians, nurses, health educators) revealed a number of site-specific barriers, including: (1) space constraints; (2) available time of site staff to facilitate the intervention; and (3) need for coordination of refreshments, staffing, and child care materials. Each of these issues was successfully addressed using a solution-focused approach that supported site staff to develop acceptable remedies to each feasibility barrier identified. This approach yielded considerable success as ten sessions of the CHAMP+ program were delivered during the pilot study. However, other programmatic barriers to participation were identified throughout the course of the pilot included issues related to weather, transportation, childcare, and discussion of sensitive topics. Weather appeared as the most frequent programmatic barrier to participation, as the intervention program occurred over the course of the winter and holiday months.

Modifications to the CHAMP+ Family Program Curriculum

Issues of Disclosure and Privacy

Although study findings indicated that the intervention was perceived as beneficial to participants, the process evaluation also revealed several areas where the CHAMP+ Family Program needs to be further tailored to meet the needs of families affected by pediatric HIV. Despite the extensive collaborative and planning stages of CHAMP+, HIV-related issues surfaced continued to emerge during program implementation that resulted in further modification of the intervention protocol. For example, participants continually expressed issues of HIV-related secrecy, disclosure and stigma throughout CHAMP+ Family Program intervention sessions:

No matter how much we talk about it, stigma and people are still there–Caregiver participant

People look at us differently because of the virus.–HIV+ child

Why isn’t he reacting like I did–no emotion (laid back)–I didn’t want to face or accept or deal with it until I came here and Dr. A said something–Caregiver participant

Recent disclosure was especially significant for this group as one child, who was asked if he had any questions during session 2, asked point blank, “How do you cure HIV, how it happens, and how to stop it?” One caregiver spoke about how telling her child that he was adopted was more of an issue for her than disclosing illness. Another HIV+ caregiver said: “My motto is don’t tell nobody.”

Qualitative analyses of the process notes indicated that issues of HIV/AIDS-related stigma and disclosure were the most frequently reported issues that arose during program implementation. Since participants clearly needed to express these issues, it was difficult to complete lesson modules. Several sessions thus needed to be altered in order to incorporate such concerns.

Resulting Modifications of CHAMP+ Material

As a result of feedback, existing CHAMP+ curricula were continually modified. Deviation from original curricula was noted, and CHAMP+ programmers modified the delivery of remaining sessions accordingly. For example, the original CHAMP session on ‘Talking and Listening’ was modified to ‘Talking and Listening within the Context of HIV.’ In addition, HIV-related content was moved forward in the program, while communication-related content (which was originally planned for earlier sessions) was moved towards the end of the program. Addressing these concerns first, was critical to helping families consider more general parenting and prevention issues.

Besides issues of HIV/AIDS-related stigma and disclosure, certain programmatic content, including parent-child relationships, children’s worries/concerns, HIV knowledge, and child sexuality emerged as themes that required revision of the CHAMP+ curriculum.

DISCUSSION

In the pilot study described in this article, a family-based HIV prevention program, CHAMP, provided important intervention design elements for the design and pilot of an intervention for HIV+ preadolescents and their families, entitled CHAMP+. To adapt CHAMP into the CHAMP+ program, issues specific to this population, including HIV as a stigmatizing disease, disclosure of the illness to the child and those within and outside the family, adherence to medical treatment, multiple losses experienced by families and fears about the future were incorporated into the curriculum.

In designing the CHAMP+ pilot project, consumers were involved in roles of critical importance through meetings to design the program. As a result of these meetings, the content of the CHAMP Family Program was changed and additional sessions were added, although the format of program delivery was maintained. The preliminary evaluation of the program revealed that the collaboration between HIV-infected youth, their adult caregivers, pediatric HIV primary care providers, and HIV prevention scientists yielded a program that reflected the special needs of families affected by pediatric HIV. Study findings, based on participants’ perception of change as detailed in the post-intervention exit interviews and process notes, showed enhancement of the caregiver/child relationship, increased communication, increased participant self-efficacy, and social network expansion with others affected by HIV.

However, the process evaluation also revealed several areas where the CHAMP+ Family Program needed to be further tailored to meet the needs of families affected by pediatric HIV. More specifically, issues related to HIV stigma, disclosure, and secrecy proved to be of even great importance than anticipated for the study sample. Thus, the overall ‘lessons learned’ from the process evaluation of the CHAMP+ Family Program was that addressing issues of secrecy, HIV disclosure, and stigma in the early sessions of an intervention are critical to the development of an acceptable preventative intervention for this population. Failure to address these issues prior to the delivery of health promotion messages will undermine any preventative intervention efforts.

Conclusions

The public health implications of the transition of HIV/AIDS from an acute, lethal disease to a sub-acute chronic disease are enormous (Brown, Lourie, & Pao, 2000). Perinatally HIV-infected preadolescents are quickly emerging as a group at risk of engaging in behaviours that jeopardise their own health, and that of others. Programs and services are urgently needed that help perinatally HIV-infected children in making the transition from childhood into adolescence and that engage them in HIV prevention efforts.

A process evaluation of the CHAMP+ Family Program pilot study provided valuable insights related to a possible program structure and process. These preliminary findings will be especially beneficial to programmers seeking to plan, implement, and evaluate HIV preventative interventions with HIV-infected populations of youth and their families. These results suggest that families affected by pediatric HIV accepted and identified with a family-based model, implemented in a clinical setting.

However, this was an exploratory, pilot study implemented with only 10 participants (five caregiver/child dyads). Results must be interpreted with caution, as the sample is not large enough to generalize to the larger pediatric HIV population. Clearly, the CHAMP+ Family Program needs to be implemented with a larger sample to determine if the preliminary results are replicable.

Given current estimates and the millions more children projected to be born with perinatally acquired-HIV internationally, particularly in resource poor countries, progressive and innovative approaches to preventative interventions for HIV+ youth are needed. A family-based model such as CHAMP+ that seeks to intervene with perintally HIV-infected youth during the crucial time of adolescence may not only enhance the youths’ quality of life, but may also dramatically reduce the spread of HIV/AIDS.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the significant contributions of participating families and consultants.

Funding from the New York State Psychiatric Institute, HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies Grant (P30 MH43520) is gratefully recognized. Dorian Traube is currently a pre-doctoral fellow at the Columbia University School of Social Work supported by a training grant from the National Institutes of Mental Health (5T32MH014623-24).

Footnotes

COPYRIGHT NOTICE: The copy law of the United States (Title 17 U.S. Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship or research”. Note that in the case of electronic files, “reproduction” may also include forwarding the file by email to a third party. If a user makes a request for, or later uses a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of “fair use”, that user may be liable for copyright infringement. USC reserves the right to refuse to process a request if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. By using USC’s Integrated Document Delivery (IDD) services you expressly agree to comply with Copyright Law.

REFERENCES

- Abrams E, Nicholas S. Pediatric HIV Infection. Pediatric Anals. 1990;19(8):482–487. doi: 10.3928/0090-4481-19900801-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amerikaner M, Monks G, Wolfe P, Thomas S. Family interaction and psychological health. Journal of Counseling and Development. 1995;72:614–620. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister LM, Flores E, Martin BV. Sex information given to Latina adolescents by parents. Health Education Research. 1995;10:233–239. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Furstenberg FF. Adolescent sexual behavior. American Psychologist. 1989;44:249–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne M, Honig J, Jurgrau A, Heffernan SM, Donahue MC. Achieving adherence with antiretroviral medications for pediatric HIV disease. AIDS Reader. 2002;12(4):151–154. 161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, et al. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: The AACTG adherence Instruments. AIDS Care. 2000;12:255–266. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS Surveillance report. 2002 Website: http://www.cdc.gov.

- Cooper ER, Charurat M, Mafenson L, et al. Combination antiretroviral strategies for the treatment of pregnant HIV-1 infected women and prevention of perinatal HIV-1 transmission. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2002;29(5):484–494. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200204150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsi A, Albizzati A, Cervini R, et al. Hyperactive disturbance in the behavior of children with congenital HIV infection. In Abstract of the Seventh International AIDS Conference, Vol 2, Abstract WD 4380; June 16–21, 1991; Florence, Italy. 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton HL. AIDS in blackface. Daedalus. 1989;118(3):205–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Martino M, Tovo PA, Balducci M, Galli L, Gabiano C, Rezza G, Pezzotti P. Reduction in mortality with availability of antiretroviral therapy for children with perinatal HIV-1 infection. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:190–197. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein BJ, Little SJ, Richman DD. Drug Resistance among Patients Recently Infected with HIV. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;347(23):1889–1890. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200212053472315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox GL, Inazu JK. Patterns and outcomes of mother-daughter communication about sexuality. Journal of Social Issues. 1980;36(1):7–29. [Google Scholar]

- Grosz J. Children with HIV infection becoming teenagers. Psychosocial and developmental tasks. Paper presented at Pediatric AIDS and Mental Health Issues in the Era of Art Conference, jointly sponsored by NIMH Center for Mental Health research on AIDS and The Office of Rear Diseases, NIH; September 10th; Washington DC. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson KE, McNamara JR, Jensen JA. Informed consent: Risk and benefit disclosure practices of child clinicians. Psychotherapy in Private Practice. 1992;10(4):91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Hatch J, Moss N, Saran A, Presley-Cantrell L, Mallory C. Community research: Partnership in black communities. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1993;9(6, Suppl):27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havens JF, Mellins CA, Hunter J. Psychiatric Aspects of HIV/AIDS in childhood and adolescence. In: Rutter M, Taylor E, editors. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: Modern Approaches/Fourth Edition. Oxford: UK Blackwell; 2002. pp. 828–841. [Google Scholar]

- Havens J, Ng W. The Context of HIV/AIDS Infections of Children in the United States. Paper presented at Pediatric AIDS and Mental Health Issues in the Era of Art Conference, jointly sponsored by NIMH Center for Mental Health research on AIDS and The Office of Rear Diseases, NIH; September 10th; Washington DC. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Havens JF, Whitaker AH, Feldman JF, Ehrhardt AA. Psychiatric morbidity in school-age children with congenital human immunodeficiency virus infection: A pilot study. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics (Supplement, “Priorities in psychosocial research in pediatric HIV infection”) 1994;15:S18–S25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller SE, Bartlett JA, Schleifer SJ, Johnson RL, Pinner E, Delaney B. HIV-relevant sexual behavior among a health inner-city heterosexual adolescent population in an endemic area of HIV. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1991;12:44–48. doi: 10.1016/0197-0070(91)90040-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein M, Gordon S. Sex Education. In: Walker CE, Roberts MC, editors. Handbook of Clinical Child Psychology. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1990. pp. 933–949. (1990) [Google Scholar]

- Kotchick BA, Dorsey S, Miller KS, Forehand R. Adolescent sexual-risk taking behavior in single-parent ethnic minority families. Journal of Family Psychology. 1999;31(1):93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Kranzler EM, Shaffer D, Wasserman G, Davies M. Early childhood bereavement. Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry. 1990;29:513–520. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199007000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledlie Susan W. The psychosocial issues of children with perinatally acquired HIV disease becoming adolescents: A growing challenge for providers. AIDS Patient Care & Stds. 2000;15(5):231–236. doi: 10.1089/10872910152050748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindegren [Retrieved April 6, 2004];Center for Disease Control. 2001 from Website://www.cdc.gov/hiv/projects/perinatal/materials/meeting_summary.htm.

- Lipsitz JD, Williams JBW, Rabkin J, Remien RH, Bradbury M, El-Sadr W, Goetz R, Sorrell S, Gorman J. Psychopathoiogy in male and female intravenous drug users with and without HIV infection. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:1662–1668. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.11.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon ME, Silber TJ, D’Angelo LJ. Difficult Life Circumstances in HIV-infected adolescents cause or effect? AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 1997;11:29–37. doi: 10.1089/apc.1997.11.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison S, Bell CC, Sewell SD, Nash G, McKay MM, Paikoff RL CHAMP Collaborative Board. Collaborating with communities in intervention and research: Approaching an “ideal” partnership. Manuscript to be published in Psychiatric Services. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Madison S, McKay M, Paikoff R, Bell C. Community collaboration and basic research: Necessary ingredient for the development of a family based HIV prevention program. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2000;12:75–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay M, Baptiste D, Coleman D, Madison S, McKinney L, Paikoff R CHAMP Collaborative Board. In: Preventing HIV risk exposure in urban communities: The CHAMP family program. Pequegnat W, Szapocznik J, editors. Thousand Oaks, CA: Working with Families in the Era of HIV/AIDS; 2000. pp. 67–87. [Google Scholar]

- Mellins CA, Bracks-Cott E, Dolezal C, Richards A, Abrams E. Patterns of HIV status disclosure to perinatally infected HIV-positive children and subsequent mental health outcomes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;7:101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Mellins CA, Ehrhardt AA, Grant WF. Psychiatric symptomatology and psychological distress in HIV-infected mothers. AIDS and Behavior. 1997;1:233–245. [Google Scholar]

- Mellins CA, Smith R, O’Driscoll P, Magder L, Brouwers P, Chase C, Blasini I, Hittleman J, Llorente A, Matzen E the NIH NIAID/NICHD/NIDA-sponsored Women and Infant Transmission Study Group (WITS) High rates of behavioral problems in perinatally HIV-infected children are not linked to HIV disease. Pediatrics. 2003;111:384–393. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.2.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaels D. The Orphan Project: Estimates of children and youth orphaned by maternal death from HIV/AIDS in New York State. New York: Press release, Albany; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Miller K, Forehand R, Kotchick BA. Adolescent sexual behavior in two ethnic minority samples the role of family variables. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;61:85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison MF, Petitto JM, Have TT, Gettes DR, Chiappini MS, Weber AL, Brinker-Spence P, Bauer RM, Douglas SD. Depressive and Anxiety Disorders in Women with HIV infection. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:789–796. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison MF, Petitto JM, Have TT, Gettes DR, Chiappini MS, Weber AL, Brinker-Spence P, Bauer RM, Douglas SD. Depressive and Anxiety Disorders in Women with HIV infection. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:789–796. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DA, Moscicki B, Vermund S, Muenz L the Adolescent medicine HIV/AIDS Research Network. Psychological distress among HIV+ adolescents in the REACH study: Effects of life stress, social support, and coping. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;27:391–398. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for HIV, S., and TB Prevention. New York: US AIDS Surveillance Report; 2001. Retrieved 10/17/2003, 2003, from http://www.statehealth.facts.kff.org. [Google Scholar]

- New York City Department of Health, Office of AIDS Surveillance. HIV/AIDS Surveillance update. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas SW, Abrams EJ. Boarder Babies with AIDS in Harlem: Lessons in Applied Public Health. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(2):163–165. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.2.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan L, Jaramillo BMS, Moreau D, Meyer-Bahlburg HL. Mother- daughter communication about sexuality in clinical sample of Hispanic adolescent girls. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1999;21:447–469. [Google Scholar]

- Paikoff RL. Early heterosexual debut: Situations of sexual possibility during the transition to adolescence. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1995;65:389–401. doi: 10.1037/h0079652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paikoff RL. Applying developmental psychology to an AIDS prevention model for urban African American youth. Journal of Negro Education. 1997;65:44–59. [Google Scholar]

- Papola P, Alvarez M, Cohen HJ. Developmental and Service Needs of School-Age Children With Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection: A Descriptive Study. Pediatrics. 1994;94(6):914–918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, Brester M, Vergis EN, Squier C, Wagener MM, Singh Z. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2000;1333:21–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-1-200007040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pick S, Palos PA. Impact of the families on the sex lives of adolescents. Adolescence. 1997;30:667–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier DA, Farmer M, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LS, Goodwin FK. Co-morbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drugs of abuse. Journal of American Medical Association. 1990;264:2511–2518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Foley-Anton SF, Carroll K, Budde D, et al. Psychiatric Diagnosis for Treatment-Seeking Cocaine Abusers. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;48:43–51. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810250045005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Children of sick parents. London: Oxford University Press; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson HC, White JJ. AIDS prevention struggles in ethno cultural neighborhoods: Why research partnerships with community based organizations can’t wait. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1994;6(2):126–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardieu M, Mayaux MJ, Seibel N, Funk-Brentano L, Straub E, Teglas J, Blanche S. Cognitive assessment of school-age children infected with maternally transmitted human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Journal of Pediatrics. 1995;126:375–379. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(95)70451-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SB, Quinn SC. The Tuskegee syphilis study, 1932 to 1972: Implications for HIV education and AIDS risk education programs in the black community. American Journal of Public Health. 1991;81(11):1498–1505. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.11.1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener LS, Battles HB, Heilman NE. Factors associated with parent’s decision to disclose their HIV diagnosis to their children. Child Welfare. 1998;77:115–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]