Abstract

ATP-driven efflux transporters at the blood-brain barrier both protect against neurotoxicants and limit drug delivery to the brain. In other barrier and excretory tissues, efflux transporter expression is regulated by certain ligand-activated nuclear receptors. Here we identified constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) as a positive regulator of P-glycoprotein, multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (Mrp2), and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) expression in rat and mouse brain capillaries. Exposing rat brain capillaries to the CAR activator, phenobarbital (PB), increased the transport activity and protein expression (Western blots) of P-glycoprotein, Mrp2, and BCRP. Induction of transport was abolished by the protein phosphatase 2A inhibitor, OA. Similar effects on transporter activity and expression were found when mouse brain capillaries were exposed to the mouse-specific CAR ligand, 1,4-bis-[2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)]benzene (TCPOBOP). In brain capillaries from CAR-null mice, TCPOBOP did not increase transporter activity. Finally, treating mice with 0.33 mg/kg TCPOBOP or rats with 80 mg/kg PB increased P-glycoprotein-, Mrp2-, and BCRP-mediated transport and protein expression in brain capillaries assayed ex vivo. Thus, CAR activation selectively tightens the blood-brain barrier by increasing transport activity and protein expression of three xenobiotic efflux pumps.

Introduction

The brain capillary endothelium, which comprises the blood-brain barrier, is a major obstacle to the delivery of therapeutic drugs to the brain. In addition to low-permeability tight junctions between cells, brain capillary endothelial cells express ATP-driven drug-efflux pumps (ABC transporters) at the luminal plasma membrane (e.g., P-glycoprotein, BCRP, Mrp2, and Mrp4) (Abbott et al., 2010). These both limit CNS accumulation of small drugs (P-glycoprotein, BCRP, Mrp4) and facilitate the excretion of drug metabolites and waste products of CNS metabolism (Mrp2). Certainly for P-glycoprotein (Miller et al., 2008) and probably for BCRP, increased transporter expression selectively tightens the barrier to drugs that are substrates, and reduced transporter expression selectively loosens the barrier.

In hepatocytes and other barrier and excretory tissues, PXR and CAR, both former orphan nuclear receptors, coordinately up-regulate the expression of phase I and phase II drug metabolism and increase excretory transport mediated by ABC transporters (Wang and Negishi, 2003; Xu et al., 2005). This up-regulation occurs in response to receptor ligands that are endogenous metabolites (e.g., bile acids) and xenobiotics (e.g., therapeutic drugs, dietary constituents, and environmental toxicants) (Stanley et al., 2006). Recent studies with isolated rodent brain capillaries and brain capillary endothelial cells show transcriptional up-regulation of P-glycoprotein, BCRP, and Mrp2 by ligands that activate PXR (Bauer et al., 2004, 2006, 2008). It is noteworthy that treating “humanized” transgenic mice with the hPXR ligand rifampin increased P-glycoprotein expression at the blood-brain barrier and substantially reduced CNS efficacy of the P-glycoprotein substrate methadone (Bauer et al., 2006). Thus, increased expression of P-glycoprotein at the blood-brain barrier influenced drug CNS pharmacodynamics.

Although there are clearly ligands that activate only one of the two receptors, the list of known PXR and CAR ligands do overlap to some extent (Moore et al., 2003). The same could be said about target genes and PXR and CAR promoter elements (Xie et al., 2000; Wei et al., 2002). As with PXR, CAR regulation of transporter expression is less well studied than the induction of xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes. Recent reports suggest increases in ABC transporter mRNA in response to CAR ligands (Kast et al., 2002; Burk et al., 2005; Jigorel et al., 2006), but to date, there are few reports showing increased transporter protein expression (Xiong et al., 2002; Lombardo et al., 2008) and none showing increased transporter activity. We report here that CAR mRNA and protein are expressed in isolated rat and mouse brain capillaries and that CAR activation increases the expression and transport activity of the blood-brain barrier P-glycoprotein, BCRP, and Mrp2 in vitro and in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

Rabbit polyclonal CAR antibody was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), mouse polyclonal P-glycoprotein antibody was from Covance Research Products (Princeton, NJ), and antibodies against Mrp2 and BCRP were from Alexis Biochemicals (San Diego, CA). NBD-CSA was custom-synthesized (Schramm et al., 1995), and BODIPY-prazosin was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Valspodar (PSC833) was kindly provided by Novartis (Basel, Switzerland). 3-[[3-[2-(7-Chloroquinolin-2-yl)vinyl]phenyl]-(2-dimethylcarbamoylethylsulfanyl)methylsulfanyl] propionic acid (MK571) was obtained from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). (3S,6S,12aS)-1,2,3,4,6,7,12,12a-Octahydro-9-methoxy-6-(2-methylpropyl)-1,4-dioxopyrazino[1′,2′:1,6]pyrido[3,4-b]indole-3-propanoic acid 1,1-dimethylethyl ester (Ko143) (Allen et al., 2002) was a kind gift from Dr. Alfred H. Schinkel of the Netherlands Cancer Institute (Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Sodium PB, PCN, TCPOBOP, OA, LTC4, wortmannin, Texas red (sulforhodamine 101 free acid), mouse monoclocal β-actin antibody, fumitremorgin C (FTC), Ficoll, and all other chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). All reagents were of analytical grade or the best available pharmaceutical grade.

Animals.

All experiments were performed in compliance with National Institutes of Health Animal Care and Use Guidelines and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (Research Triangle Park, NC). Male retired breeder Sprague-Dawley rats (6–9 months; Taconic Farms, Germantown, NY), male C3H mice (Charles River Laboratories, Inc., Wilmington, MA), and CAR knockout mice (kindly provided by Dr. Masahiko Negishi, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences/National Institutes of Health; bred on C3H background) were housed in temperature-controlled rooms under a 12-h light/dark cycle and were given ad libitum access to food and water. At the time of use, mice were 10 weeks old and weighed 24.8 ± 1.5 g. Animals were euthanized by CO2 inhalation followed by decapitation. For in vivo treatment of mice, PCN or TCPOBOP dissolved in corn oil (Sigma-Aldrich) was given once a day for 2 days by intraperitoneal injection at a dose of 50 mg/kg (PCN) and 0.33 mg/kg (TCPOBOP). Controls received the same volume of corn oil. On day 3, brain capillaries were prepared and immediately used for transport experiments and capillary membrane isolation for subsequent assay by Western blotting. For in vivo treatment of rats, PB dissolved in normal saline solution was given once a day for 4 days by intraperitoneal injection at a dose of 80 mg/kg. Control rats received the same volume of saline solution. On day 5, brain capillaries were prepared and immediately used for transport experiments and capillary membrane isolation for subsequent assay by Western blotting.

Capillary Isolation.

The detailed procedures for capillary isolation have been described previously (Miller et al., 2000; Hartz et al., 2004). In brief, white matter, meninges, midbrain, choroid plexus, blood vessels, and olfactory lobes were removed from the brains under a dissecting microscope, and brain tissue was homogenized. Tissue was kept in cold PBS (2.7 mM KCl, 1.5 mM KH2PO4, 136.9 mM NaCl, 8.1 mM Na2HPO4, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM d-glucose, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate) throughout the isolation procedure. An aliquot of 30% Ficoll was added to an equal volume of brain homogenate and capillaries were separated from the parenchyma by centrifuging at 5800g for 20 min. Capillary pellets were washed with 1% BSA in PBS and passed through a syringe column filled with glass beads. Capillaries bound to the glass beads were released by gentle agitation, washed with PBS, and used immediately for experiments.

CAR Immunostaining.

Brain capillaries were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde/0.25% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 10 min, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 min, and washed with PBS. After blocking with 1% BSA in PBS for 30 min, capillaries were incubated with rabbit anti-CAR antibody (1:200) in PBS with 1% BSA at 37°C for 60 min, washed with PBS with 1% BSA, and then incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (1:500) in PBS with 1% BSA at 37°C for 60 min. After further washing in PBS with 1% BSA, tissue was transferred to chambers for confocal microscopy. Negative controls were treated identically, except they were not exposed to primary antibody.

Transport.

Confocal microscopy-based transport assays with isolated rat and mouse brain capillaries have been described previously (Hartz et al., 2004). All experiments were carried out at room temperature in coverslip-bottomed imaging chambers filled with PBS. Protocols for specific experiments are described in respective figure legends. In general, brain capillaries were exposed for 1 to 3 h to CAR and PXR activators without or with additional inhibitors. Fluorescent substrates NBD-CSA for P-glycoprotein (Miller et al., 2000; Hartz et al., 2004), Texas red for Mrp2 (Bauer et al., 2008), and BODIPY-prazosin for BCRP (Shukla et al., 2009) were added, and luminal substrate accumulation was assessed 1 h later. In some experiments, specific inhibitors of transport were included in the incubation medium. To acquire images, the chamber containing the capillaries was mounted on the stage of a Zeiss model 510 inverted confocal laser-scanning microscope and imaged through a 40× water-immersion objective (numeric aperture, 1.2) using a 488- (for NBD-CSA or BODIPY-prazosin) or 543-nm (for Texas red) laser line for excitation. Images were saved to disk, and luminal fluorescence was quantitated by Image J software as described previously (Miller et al., 2000). Data shown are for a single experiment that is representative of three to five replicates.

Western Blots.

Membranes were isolated from control and ligand or activator-exposed capillaries as described previously (Hartz et al., 2004; Bauer et al., 2006). Membrane protein was assayed by the Bradford method. An aliquot of the membrane protein was mixed with NuPAGE 4× sample buffer (Invitrogen), loaded onto 4 to 12% Bis-Tris NuPAGE gel, electrophoresed, and then transferred to an Immobilon-FL membrane (Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA). The membrane was blocked with Odyssey Blocking Buffer (Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) at room temperature for 1 h and then immunoblotted overnight with antibodies against P-glycoprotein, Mrp2, or BCRP, an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (Li-Cor Biosciences). The membrane was stained with corresponding goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse fluorescence dyes IRDye 680 (or IRDye 800) in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20 at room temperature for 45 min and then imaged using an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (Li-Cor Biosciences). β-Actin (42 kDa, 1:2000) was used as a loading control; the corresponding secondary antibody was IREDye goat anti-mouse antibody (1:15,000). NewBlot Polyvinylidene Difluoride Stripping Buffer (5×; Li-Cor Biosciences) was used to strip the membranes when needed. The membrane was scanned to ensure complete antibody removal before reprobing the membrane.

Statistical Analyses.

Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. Statistical analyses of differences between groups was by one-way analysis of variance (Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test) using Prism software version 4.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). Differences between two means were considered significant when P < 0.05.

Results

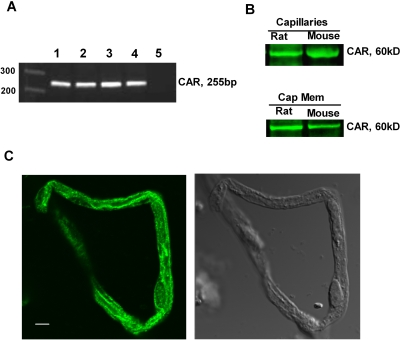

mRNA for CAR has been detected in human brain capillaries (Dauchy et al., 2008) but not in the rat (Akanuma et al., 2008). We show here by three criteria that CAR mRNA and protein are present in freshly isolated brain capillaries from rat and mouse. First, reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction assays produced specific CAR amplicons in rat and mouse brain capillary RNA (Fig. 1A). The PCR products were confirmed by direct sequencing to be identical with the rat and mouse CAR genes. Second, Western blots of total capillary lysates yielded a single, clear protein band (∼60 kDa) when an antibody against CAR was used. CAR protein was also detected in membranes isolated from rat and mouse brain capillaries (Fig. 1B). A previous report had localized CAR to the plasma membrane in mouse liver (Koike et al., 2005). The physiological significance of membrane-localized CAR is not yet clear. Third, immunocytochemical studies demonstrated that CAR protein was extensively distributed in the cytoplasm and the nucleus of rat brain capillary endothelial cells (Fig. 1C). Staining of capillary plasma membranes was also visible, consistent with our capillary membrane Western blots.

Fig. 1.

CAR expression in the rat and mouse brain capillaries. A, reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction showed CAR expression in rat and mouse liver and brain capillaries. 1, rat liver (positive control); 2, rat brain capillaries; 3, mouse liver (positive control); 4, mouse brain capillaries; 5, negative control. B, Western blot showing CAR protein expression in rat and mouse brain capillaries and capillary membrane fractions. C, immunostaining for CAR protein in freshly isolated rat brain. Representative confocal image shows CAR was distributed throughout the cytoplasm, plasma membrane, and the nucleus of the endothelial cells. Left, CAR immunostaining image; right, transmitted light image. White scale bar, 10 μm.

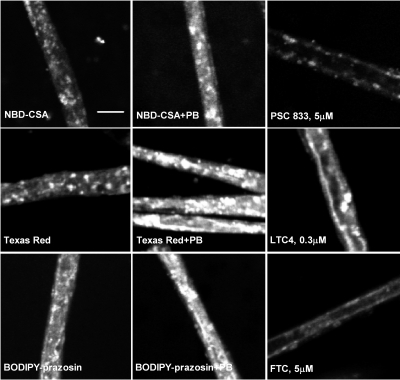

Having established that CAR is expressed in brain capillaries from rat and mouse, we examined the possibility that CAR alters the transport activity and protein expression of three ABC transporters: P-glycoprotein, Mrp2, and BCRP, shown previously to be CAR targets in hepatocytes (Kast et al., 2002; Jigorel et al., 2006). The transport activity assay we used included freshly isolated brain capillaries, fluorescent transport substrates, confocal microscopy, and quantitative image analysis to measure substrate accumulation in capillary lumens (vascular space). Previous studies validated NBD-CSA and sulforhodamine 101 free acid (Texas red) as specific substrates for P-glycoprotein and Mrp2, respectively (Miller et al., 2000; Hartz et al., 2004; Bauer et al., 2008). A recent report indicates that BODIPY-prazosin can serve the same function for BCRP (Shukla et al., 2009); we have confirmed this in preliminary experiments, which show inhibition of luminal BODIPY-prazosin accumulation by the metabolic inhibitor NaCN and by the specific BCRP inhibitors FTC and Ko143 but not by PSC833 (inhibits P-glycoprotein) or LTC4 (inhibits Mrps; see Supplemental Figure 1). Representative confocal images of rat brain capillaries incubated to steady state (60 min) with the three fluorescent substrates are shown in Fig. 2. In each control image, fluorescence is concentrated in the luminal space, and, for each, luminal fluorescence was substantially reduced when capillaries were exposed to a specific transport inhibitor (i.e., PSC833 for P-glycoprotein, LTC4 for Mrp2, and FTC for BCRP). Measurements of the effects of these transport inhibitors are shown in each panel of Fig. 2. In every case, inhibitors reduced basal (control) accumulation of respective substrates by at least 50%. Previous studies indicate that residual luminal substrate accumulation is nonspecific, probably representing diffusive entry plus binding to cellular elements (Hartz et al., 2004; Bauer et al., 2008).

Fig. 2.

Representative confocal images of rat brain capillaries showing luminal accumulation of fluorescent substrates specific for P-glycoprotein (A; 2 μM NBD-CSA), Mrp2 (B; 2 μM Texas Red) and BCRP (C; 2 μM BODIPY-prazosin). In each case, exposing capillaries to 1 mM PB for 3 h before incubation with transport substrate increased luminal substrate accumulation. Luminal accumulation was substantially reduced when specific transport inhibitors were added to the medium (5 μM PSC833 for P-glycoprotein, 0.3 μM LTC4 for Mrp2, and 5 μM FTC for BCRP). White scale bar, 10 μm.

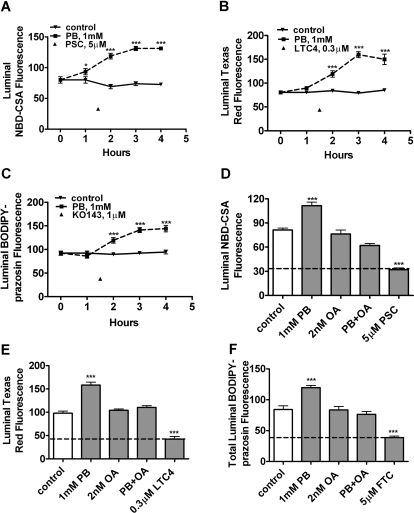

Figure 2 also shows that exposing rat brain capillaries to PB (1 mM) significantly increased luminal accumulation of NBD-CSA, Texas red, and BODIPY-prazosin. PB-induced increases in transport occurred over a period of several hours with maximal stimulation of transport occurring at 3 h for all three substrates (Fig. 3, A–C). Note that in these experiments, luminal substrate accumulation in control capillaries did not change over the 4-h time course, confirming the metabolic stability of the isolated capillary preparation.

Fig. 3.

Increased transport activity of P-glycoprotein (A and D), Mrp2 (B and E), and BCRP (C and F) in isolated rat brain capillaries after exposure to 1 mM PB. A to C, time course of PB action. Capillaries were exposed to PB for the time indicated. During the last hour of incubation, 2 μM NBD-CSA (A), 2 μM Texas Red (B), or 2 μM BODIPY-prazosin (C) was present in the medium. D to F, effect of OA inhibition of PP2A with on PB-induced increases in transport (4-h exposure). In both sets of experiments, capillaries treated with PSC833 (P-glycoprotein), LTC4 (Mrp2), FTC, or Ko143 (BCRP) indicate specific inhibition of transport. Shown are mean ± S.E.M. for 8 to 12 capillaries from a single preparation (pooled brains from 10 rats). **, p < 0.01, significantly higher than control; ***, p < 0.001, significantly higher than control.

CAR activation involves the recruitment of cytoplasmic CAR retention protein and dephosphorylation by PP2A (Yoshinari et al., 2003; Timsit and Negishi, 2007). Consistent with a role for PP2A in CAR activation, 10 nM OA inhibited PB up-regulation of cytochrome P450 2B genes in rodent liver (Kawamoto et al., 1999). With rat brain capillaries, we found that pretreatment with 2 nM OA abolished the PB-induced increase in transport activity for all three transporters; OA, by itself, had no effect on transport (Fig. 3, D–F).

In the remaining experiments, we exposed capillaries to CAR PB or TCPOBOP for 3 h and then assayed steady-state substrate accumulation after an additional hour of incubation with ligand plus fluorescent substrate. For each treatment, we calculated specific transport as the difference between accumulation without and with transport inhibitor (PSC833 for P-glycoprotein, LTC4 for Mrp2, and FTC for BCRP). With rat capillaries, increases in specific transport caused by exposure to 1 mM PB averaged 76 ± 5% (five preparations), 183 ± 36% (three preparations), and 82 ± 3% (three preparations) for P-glycoprotein, Mrp2, and BCRP, respectively (Fig. 4, A–C). For all three transporters, increases in activity were abolished by either actinomycin D or cyclohexamide, indicating a dependence on transcription and translation (Fig. 5). Consistent with increased translation, Western blots showed that PB exposure increased protein expression for all three transporters (Fig. 4D). Quantitation of bands from four experiments indicated that normalized band density for P-glycoprotein, Mrp2, and BCRP had increased by 58 ± 10, 38 ± 5, and 40 ± 5%, respectively (all significantly increased by paired t test, P < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Up-regulation of P-gp-, Mrp2-, and BCRP-mediated transport and expression in rat brain capillaries after exposure to 1 mM PB in vitro. A to C, increases of specific transport activity over multiple experiments (five preparations for P-glycoprotein, three preparations for Mrp2, and three preparations for BCRP). D, Western blots showing increased expression of all three ABC transporters in capillaries exposed to 1 mM PB for 5 h.

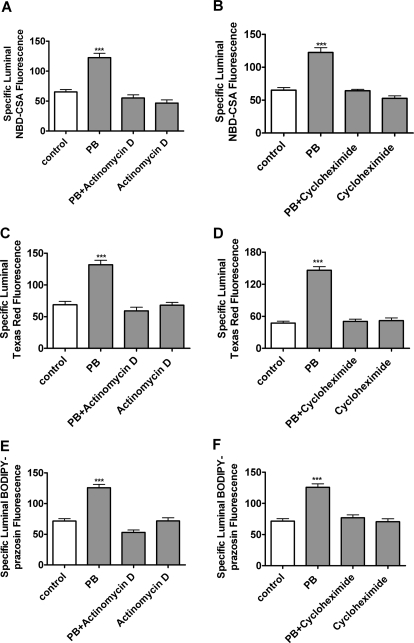

Fig. 5.

Inhibiting transcription (A, C, and E; 1 μM actinomycin D) or translation (B, D, and F; 100 μg/ml cycloheximide) blocked the effects of 1 mM PB on P-glycoprotein, Mrp2, and BCRP transport activity. Shown are mean ± S.E.M. for 8 to 12 capillaries from a single preparation (pooled brains from 10 rats). **, p < 0.01, significantly higher than control; ***, p < 0.001, significantly higher than control.

Mice provide two advantages for the study of CAR regulation of ABC transporters: TCPOBOP is a specific and potent CAR ligand (Timsit and Negishi, 2007), and CAR-null mice have been produced (Ueda et al., 2002). In mouse brain capillaries, transport activity for P-glycoprotein, Mrp2, and BCRP increased after exposure to 50 to 250 nM TCPOBOP (Fig. 6, A, C, and E). As shown above for PB induction of transport in rat brain capillaries, 10 nM OA blocked these effects of TCPOBOP in mouse capillaries (Fig. 6, B, D, and F).

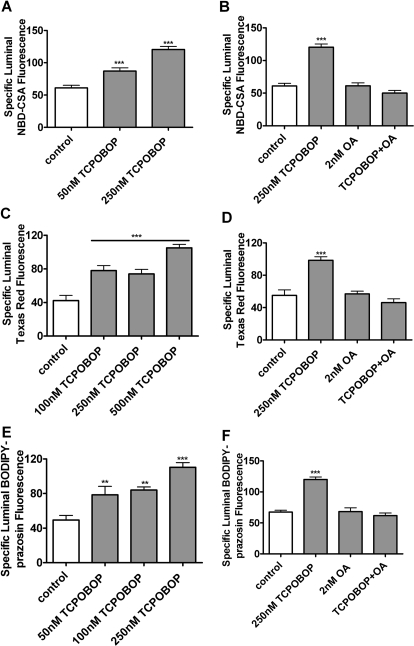

Fig. 6.

TCPOBOP increases transport activity in mouse brain capillaries in vitro. Freshly isolated mouse brain capillaries were exposed to TCPOBOP for 4 h; during the last hour, fluorescent substrates (NBD-CSA for P-glycoprotein, Texas Red for Mrp2, and BODIPY-prazosin for BCRP) and transport inhibitors were present in the medium. A, C, and E, concentration-dependent induction of transport with TCPOBOP. B, D, and F, induction was abolished when capillaries were pretreated for 30 min (before TCPOBOP exposure) with the PP2A inhibitor OA. Shown are mean ± S.E.M. for 8 to 12 capillaries from a single preparation (pooled brains from 10 rats). **. p < 0.01, significantly higher than control; ***, p < 0.001, significantly higher than control.

To further confirm the role of CAR in the modulation of ABC transporter activity and expression, parallel experiments were conducted in brain capillaries isolated from CAR-null mice. These knockout mice were bred on a C3H background (Ueda et al., 2002; Jackson et al., 2006), so the appropriate wild-type controls are the animals used in the experiments shown in Fig. 6. Exposing capillaries from CAR-null mice to 250 nM TCPOBOP did not increase transport mediated by P-glycoprotein, Mrp2, or BCRP (Fig. 7). Consistent with previous experiments in rat and mouse (Bauer et al., 2004, 2006), PCN, a specific ligand for rodent PXR, significantly increased transport on P-glycoprotein and Mrp2. Transport on BCRP was also increased by PCN exposure, suggesting for the first time that BCRP is a PXR target gene in brain capillaries. This finding is in agreement with results from primary human hepatocytes (Jigorel et al., 2006) and from in vivo dosing experiments with wild-type and PXR-null mice (Anapolsky et al., 2006).

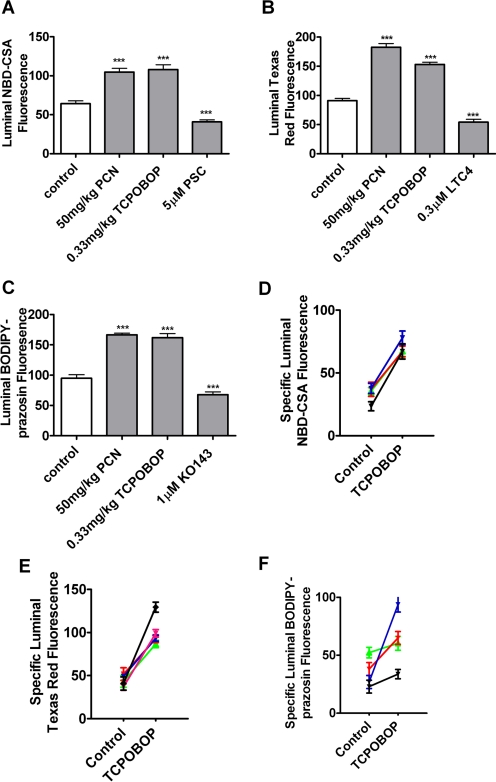

Fig. 7.

TCPOBOP does not increase transport activity in brain capillaries from CAR-null mice. Same protocol as described in Fig. 6. A, P-glycoprotein; B, Mrp2; C, BCRP. Shown are mean ± S.E.M. for 8 to 12 capillaries from a single preparation (pooled brains from 10 rats). *, p < 0.05, significantly higher than control; ***, p < 0.001, significantly higher than control.

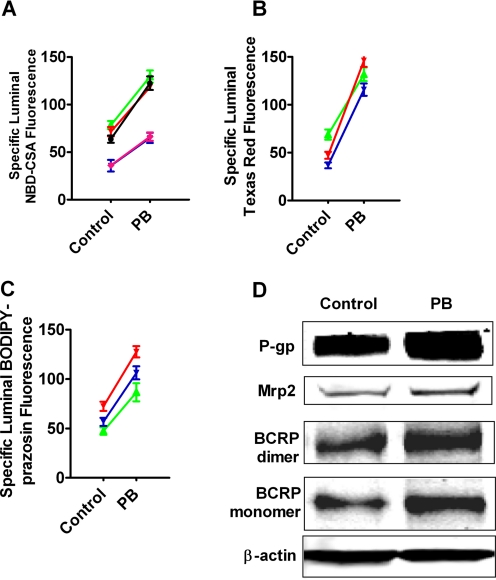

Taken together, these in vitro experiments with rat and mouse brain capillaries show that the xenobiotics PB and TCPOBOP activate the nuclear receptor CAR, leading to increased transport activity and protein expression for three ABC transporters: P-glycoprotein, Mrp2, and BCRP. To determine the effect of CAR ligand exposure on blood-brain barrier transporter activity and expression in vivo, we treated mice with PCN (50 mg/kg) or TCPOBOP (0.33 mg/kg) for 2 days by intraperitoneal injection and then isolated brain capillaries to determine transport activity and transporter expression. Livers were also collected, and liver membranes were prepared as a positive control. The dose levels were chosen based on the published data showing significant induction by CAR or PXR (Zelko et al., 2001; Bauer et al., 2004). Figure 8, A to C, shows that treating mice with PCN or TCPOBOP significantly increased the transport activity of P-glycoprotein, Mrp2, and BCRP in brain capillaries. Pooled results from four to five separate preparations showed that specific transport on P-glycoprotein, Mrp2, and BCRP increased on average by 93, 149, and 120%, respectively (Fig. 8, D–F). Consistent with increased transporter expression, Western blots showed that TCPOBOP treatment increased immunoreactivity for all three transport proteins in membranes isolated from both brain capillaries and liver (Fig. 9). Quantitation of bands from three dosing experiments indicated that normalized band density for P-glycoprotein, Mrp2, and BCRP had increased by 57 ± 3, 30 ± 3, and 37 ± 6%, respectively (all significantly increased by paired t test, P < 0.01 for P-glycoprotein, P < 0.05 for Mrp2 and BCRP).

Fig. 8.

Increased transport activity and expression of P-glycoprotein, Mrp2, and BCRP after exposure to CAR and PXR ligands in vivo. C3H mice were treated by intraperitoneal injection with 50 mg/kg PCN (PXR ligand) or 0.33 mg/kg TCPOBOP (CAR ligand) daily for 2 consecutive days. Brains and livers were collected on day 3. A to C, transport in freshly isolated mouse brain capillaries (1-h incubation with fluorescent substrate plus inhibitors). A, NBD-CSA; B, Texas Red; C, BODIPY-prazosin. Shown are mean ± S.E.M. for 8 to 12 capillaries from a single preparation (pooled brains from 10 mice). *, p < 0.05, significantly higher than control; ***, p < 0.001, significantly higher than control. D to F, increases in specific transport activity of P-glycoprotein, Mrp2, and BCRP over four to five TCPOBOP dosing experiments.

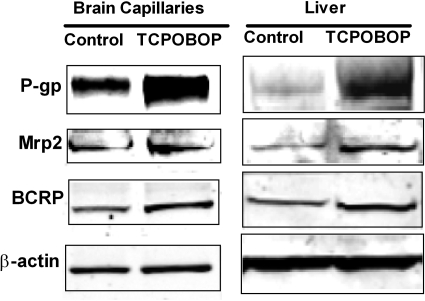

Fig. 9.

Increased protein expression of P-glycoprotein, Mrp2, and BCRP after exposure to CAR ligand TCPOBOP in vivo. Western blots of P-gp, Mrp2, and BCRP in membranes from brain capillaries and livers of vehicle-injected (control) mice and mice treated with the CAR ligand TCPOBOP.

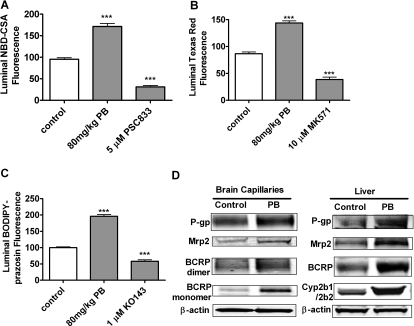

In a second set of in vivo experiments, we treated rats by intraperitoneal injection with 80 mg/kg PB for 4 days and isolated brain capillaries to determine transport activity and transporter expression. Figure 10 shows that, as with TCPOBOP in mice, PB treatment in rats increased the transport activity of P-glycoprotein, Mrp2, and BCRP in brain capillaries and increased protein expression of the transporters in brain capillary membranes and in liver membranes.

Fig. 10.

Increased transport activity and expression of P-gp, Mrp2, and BCRP after exposure to the CAR activator PB in vivo. Rats were treated with intraperitoneal injection with 80 mg/kg PB daily for four consecutive days. Brains and livers were collected on day 5. A to C, transport in freshly isolated brain capillaries (1-h incubation with fluorescent substrate plus inhibitors). A, NBD-CSA; B, Texas Red; C, BODIPY-prazosin. Shown are mean ± S.E.M. for 8 to 12 capillaries from a single preparation (pooled brains from 10 rats). ***, p < 0.001, significantly higher than control. D, Western blots of P-glycoprotein, Mrp2, and BCRP in membranes from brain capillaries and livers of vehicle-injected (control) rats and rats treated with the CAR activator PB.

Discussion

We demonstrated previously the up-regulation of blood-brain barrier P-glycoprotein and Mrp2 by ligands that activate the nuclear receptor PXR (Zelko et al., 2001; Bauer et al., 2004, 2006, 2008). The present experiments suggest that blood-brain barrier BCRP is also a PXR target, a finding that is in agreement with results from primary human hepatocytes (Jigorel et al., 2006) and from in vivo dosing experiments with wild-type and PXR-null mice (Anapolsky et al., 2006). The present results for rodent brain capillaries identify another ligand-activated receptor through which xenobiotics and endogenous metabolites can influence blood-brain barrier transport function. By three distinguishing criteria, we established for the first time that the ligand-activated nuclear receptor CAR is an inducer of expression and transport activity of multiple ABC transporters at the blood-brain barrier.

First, we demonstrated the expression of CAR at the mRNA and protein levels in extracts from freshly isolated rat and mouse brain capillaries and by immunostaining intact rat brain capillaries. CAR expression was detected in a number of barrier and excretory tissues (Lamba et al., 2004; Nannelli et al., 2008), but attempts to establish the expression of this receptor at the blood-brain barrier were inconclusive. That is, Akanuma et al. (2008) were unable to detect CAR and PXR mRNA in a rat brain capillary fraction and in a rat brain capillary endothelial cell line. However, Dauchy et al. (2008) found low but detectable levels of CAR (and PXR) mRNA in brain capillaries isolated from patient biopsies and in an immortalized human cerebral microvascular cell line.

Second, we show here that exposure of isolated brain capillaries to PB for rat and TCPOBOP for mouse increased transport activity and protein expression of P-glycoprotein, Mrp2, and BCRP. Increases in transport activity induced in vitro averaged 80 to 150% over control values, roughly equivalent to that reported previously for PXR induction of P-glycoprotein-mediated transport in rat brain capillaries (Bauer et al., 2004). PB-induced increases in transport activity were abolished when capillaries were exposed to actinomycin D or cyclohexamide, indicating a dependence on transcription and translation. Consistent with the involvement of CAR, increases in specific transport were abolished by the PP2A inhibitor OA, a known modulator of CAR activity. No such increases in transport activity were seen in capillaries from CAR-null mice exposed to TCPOBOP. Capillaries from CAR-null mice were able, however, to respond to the PXR ligand PCN with increased transport activity of P-glycoprotein, Mrp2, and BCRP. These findings certainly implicate CAR in the up-regulation of transporter protein expression in brain capillaries. However, they do not speak to the mechanism by which this happens (i.e., through direct activation of transcription by CAR binding to response elements in the promoter region of the transporter genes or indirect action through CAR-induced signaling).

Finally, treating mice with TCPOBOP or rats with PB increased P-glycoprotein-, Mrp2-, and BCRP-mediated transport in brain capillaries and protein expression of all three transporters in membranes from brain capillaries and liver (present study). Previous studies of CAR regulation of these efflux transporters in cells and tissues have focused on changes in transporter expression at the mRNA level (Kast et al., 2002; Burk et al., 2005; Jigorel et al., 2006). Thus, our results are particularly important, because they are the first to demonstrate for any tissue that in vivo exposure to a specific CAR ligand can increase ABC transporter-mediated transport and transporter protein expression. Note that the level of transporter induction seen here with TCPOBOP is roughly equivalent to that seen in dosing studies with PXR ligands (Bauer et al., 2006). Those latter experiments showed substantial pharmacodynamic effects of elevated P-glycoprotein expression in a transgenic mouse expressing human PXR and treated with rifampin.

CAR ligands include endogenous bile acids, therapeutic drugs, dietary constituents, and environmental pollutants (Stanley et al., 2006). All of these classes of chemicals contain substrates for transport on at least one of the ABC transporters studied here. Thus, through CAR activation, xenobiotics can induce the expression of blood-brain barrier efflux pumps that limit their own access to the CNS. However, they can also induce the expression of efflux transporters for which they are not substrates. Consider PB, a CAR ligand (not a PXR ligand) and an anticonvulsant that clearly enters the CNS. This drug is not a P-glycoprotein substrate and is not likely to be a substrate for other drug efflux pumps. Through CAR-mediated induction, PB has the potential to increase the expression of P-glycoprotein and thus selectively tighten the blood-brain barrier to many CNS-acting drugs, not including PB. Thus, as with PXR, the consequences of CAR induction of efflux transporters at the blood-brain barrier may be far-reaching. Indeed, given the promiscuity of PXR and CAR, and the use of CAR and PXR activators to treat cholestasis and jaundice (Zollner and Trauner, 2009), it is likely that a large segment of the population is already induced. One wonders about the extent to which placing patients on a diet devoid of PXR and CAR ligands might improve drug delivery to the CNS.

Although CAR and PXR were initially described as xenosensors that coordinated hepatic responses to xenobiotics, recent evidence indicates that they are also important regulators of hepatic energy metabolism. In liver, both receptors regulate expression of genes in pathways that control both lipid and carbohydrate metabolism, including genes that code for enzymes and transporters (Rezen et al., 2009). At least some of the same effects are likely to be seen in nonhepatic tissues. At present, it is not clear how and to what extent CAR and PXR ligands are able to alter energy metabolism and metabolite transport at the blood-brain barrier. However, given the importance of ATP for the maintenance of the selective properties of the barrier, both receptors could indirectly alter the permeability characteristics of the endothelium to xenobiotics, nutrients, metabolites, and ions.

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article (available at http://molpharm.aspetjournals.org) contains supplemental material.

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

doi:10.1124/mol.110.063685.

- ABC

- ATP-binding cassette

- CNS

- central nervous system

- CAR

- constitutive androstane receptor

- PXR

- pregnane X receptor

- PCN

- pregnenolone 16α-carbonitrile

- TCPOBOP

- 1,4-bis-[2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)]benzene

- NBD-CSA

- [N-°(4-nitrobenzofurazan-7-yl)-d-Lys8]-cyclosporine A

- Mrp

- multidrug resistance-associated protein

- BCRP

- breast cancer resistance protein

- OA

- okadaic acid

- PB

- phenobarbital

- LTC4

- leukotriene C4

- FTC

- fumitremorgin C

- PP2A

- protein phosphatase 2A

- BSA

- bovine serum albumin

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- PSC833

- valspodar

- MK571

- 3-[[3-[2-(7-chloroquinolin-2-yl)vinyl]phenyl]-(2-dimethylcarbamoylethylsulfanyl)methylsulfanyl] propionic acid

- Ko143

- (3S, 6S,12aS)-1,2,3,4,6,7,12,12a-octahydro-9-methoxy-6-(2-methylpropyl)-1,4-dioxopyrazino[1′,2′:1,6]pyrido[3,4-b]indole-3-propanoic acid 1,1-dimethylethyl ester.

References

- Abbott NJ, Patabendige AA, Dolman DE, Yusof SR, Begley DJ. (2010) Structure and function of the blood-brain barrier. Neurobiol Dis 37:13–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akanuma S, Hori S, Ohtsuki S, Fujiyoshi M, Terasaki T. (2008) Expression of nuclear receptor mRNA and liver X receptor-mediated regulation of ABC transporter A1 at rat blood-brain barrier. Neurochem Int 52:669–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JD, van Loevezijn A, Lakhai JM, van der Valk M, van Tellingen O, Reid G, Schellens JH, Koomen GJ, Schinkel AH. (2002) Potent and specific inhibition of the breast cancer resistance protein multidrug transporter in vitro and in mouse intestine by a novel analogue of fumitremorgin C. Mol Cancer Ther 1:417–425 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anapolsky A, Teng S, Dixit S, Piquette-Miller M. (2006) The role of pregnane X receptor in 2-acetylaminofluorene-mediated induction of drug transport and -metabolizing enzymes in mice. Drug Metab Dispos 34:405–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer B, Hartz AM, Fricker G, Miller DS. (2004) Pregnane X receptor up-regulation of P-glycoprotein expression and transport function at the blood-brain barrier. Mol Pharmacol 66:413–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer B, Hartz AM, Lucking JR, Yang X, Pollack GM, Miller DS. (2008) Coordinated nuclear receptor regulation of the efflux transporter, Mrp2, and the phase-II metabolizing enzyme, GSTpi, at the blood-brain barrier. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 28:1222–1234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer B, Yang X, Hartz AM, Olson ER, Zhao R, Kalvass JC, Pollack GM, Miller DS. (2006) In vivo activation of human pregnane X receptor tightens the blood-brain barrier to methadone through P-glycoprotein up-regulation. Mol Pharmacol 70:1212–1219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burk O, Arnold KA, Geick A, Tegude H, Eichelbaum M. (2005) A role for constitutive androstane receptor in the regulation of human intestinal MDR1 expression. Biol Chem 386:503–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauchy S, Dutheil F, Weaver RJ, Chassoux F, Daumas-Duport C, Couraud PO, Scherrmann JM, De Waziers I, Declèves X. (2008) ABC transporters, cytochromes P450 and their main transcription factors: expression at the human blood-brain barrier. J Neurochem 107:1518–1528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartz AM, Bauer B, Fricker G, Miller DS. (2004) Rapid regulation of P-glycoprotein at the blood-brain barrier by endothelin-1. Mol Pharmacol 66:387–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JP, Ferguson SS, Negishi M, Goldstein JA. (2006) Phenytoin induction of the cyp2c37 gene is mediated by the constitutive androstane receptor. Drug Metab Dispos 34:2003–2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jigorel E, Le Vee M, Boursier-Neyret C, Parmentier Y, Fardel O. (2006) Differential regulation of sinusoidal and canalicular hepatic drug transporter expression by xenobiotics activating drug-sensing receptors in primary human hepatocytes. Drug Metab Dispos 34:1756–1763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kast HR, Goodwin B, Tarr PT, Jones SA, Anisfeld AM, Stoltz CM, Tontonoz P, Kliewer S, Willson TM, Edwards PA. (2002) Regulation of multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (ABCC2) by the nuclear receptors pregnane X receptor, farnesoid X-activated receptor, and constitutive androstane receptor. J Biol Chem 277:2908–2915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto T, Sueyoshi T, Zelko I, Moore R, Washburn K, Negishi M. (1999) Phenobarbital-responsive nuclear translocation of the receptor CAR in induction of the CYP2B gene. Mol Cell Biol 19:6318–6322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike C, Moore R, Negishi M. (2005) Localization of the nuclear receptor CAR at the cell membrane of mouse liver. FEBS Lett 579:6733–6736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamba JK, Lamba V, Yasuda K, Lin YS, Assem M, Thompson E, Strom S, Schuetz E. (2004) Expression of constitutive androstane receptor splice variants in human tissues and their functional consequences. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 311:811–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo L, Pellitteri R, Balazy M, Cardile V. (2008) Induction of nuclear receptors and drug resistance in the brain microvascular endothelial cells treated with antiepileptic drugs. Curr Neurovasc Res 5:82–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DS, Bauer B, Hartz AM. (2008) Modulation of P-glycoprotein at the blood-brain barrier: opportunities to improve central nervous system pharmacotherapy. Pharmacol Rev 60:196–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DS, Nobmann SN, Gutmann H, Toeroek M, Drewe J, Fricker G. (2000) Xenobiotic transport across isolated brain microvessels studied by confocal microscopy. Mol Pharmacol 58:1357–1367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JT, Moore LB, Maglich JM, Kliewer SA. (2003) Functional and structural comparison of PXR and CAR. Biochim Biophys Acta 1619:235–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nannelli A, Chirulli V, Longo V, Gervasi PG. (2008) Expression and induction by rifampicin of CAR- and PXR-regulated CYP2B and CYP3A in liver, kidney and airways of pig. Toxicology 252:105–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezen T, Tamasi V, Lövgren-Sandblom A, Björkhem I, Meyer UA, Rozman D. (2009) Effect of CAR activation on selected metabolic pathways in normal and hyperlipidemic mouse livers. BMC Genomics 10:384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schramm U, Fricker G, Wenger R, Miller DS. (1995) P-glycoprotein-mediated secretion of a fluorescent cyclosporin analogue by teleost renal proximal tubules. Am J Physiol 268:F46–F52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla S, Zaher H, Hartz A, Bauer B, Ware JA, Ambudkar SV. (2009) Curcumin inhibits the activity of ABCG2/BCRP1, a multidrug resistance-linked ABC drug transporter in mice. Pharm Res 26:480–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley LA, Horsburgh BC, Ross J, Scheer N, Wolf CR. (2006) PXR and CAR: nuclear receptors which play a pivotal role in drug disposition and chemical toxicity. Drug Metab Rev 38:515–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timsit YE, Negishi M. (2007) CAR and PXR: the xenobiotic-sensing receptors. Steroids 72:231–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda A, Hamadeh HK, Webb HK, Yamamoto Y, Sueyoshi T, Afshari CA, Lehmann JM, Negishi M. (2002) Diverse roles of the nuclear orphan receptor CAR in regulating hepatic genes in response to phenobarbital. Mol Pharmacol 61:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Negishi M. (2003) Transcriptional regulation of cytochrome p450 2B genes by nuclear receptors. Curr Drug Metab 4:515–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei P, Zhang J, Dowhan DH, Han Y, Moore DD. (2002) Specific and overlapping functions of the nuclear hormone receptors CAR and PXR in xenobiotic response. Pharmacogenomics J 2:117–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W, Barwick JL, Simon CM, Pierce AM, Safe S, Blumberg B, Guzelian PS, Evans RM. (2000) Reciprocal activation of xenobiotic response genes by nuclear receptors SXR/PXR and CAR. Genes Dev 14:3014–3023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong H, Yoshinari K, Brouwer KL, Negishi M. (2002) Role of constitutive androstane receptor in the in vivo induction of Mrp3 and CYP2B1/2 by phenobarbital. Drug Metab Dispos 30:918–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Li CY, Kong AN. (2005) Induction of phase I, II and III drug metabolism/transport by xenobiotics. Arch Pharm Res 28:249–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshinari K, Kobayashi K, Moore R, Kawamoto T, Negishi M. (2003) Identification of the nuclear receptor CAR:HSP90 complex in mouse liver and recruitment of protein phosphatase 2A in response to phenobarbital. FEBS Lett 548:17–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelko I, Sueyoshi T, Kawamoto T, Moore R, Negishi M. (2001) The peptide near the C terminus regulates receptor CAR nuclear translocation induced by xenochemicals in mouse liver. Mol Cell Biol 21:2838–2846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zollner G, Trauner M. (2009) Nuclear receptors as therapeutic targets in cholestatic liver diseases. Br J Pharmacol 156:7–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.