Abstract

Background

Brain arteriovenous malformations (BAVM) are a tangle of abnormal vessels directly shunting blood from the arterial to venous circulation and an important cause of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH). EphB4 is involved in arterial-venous determination during embryogenesis; altered signaling could lead to vascular instability resulting in ICH. We investigated the association of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and haplotypes in EPHB4 with risk of ICH at clinical presentation in BAVM patients.

Methods and Results

Eight haplotype-tagging SNPs spanning ∼29 kb were tested for association with ICH presentation in 146 Caucasian BAVM patients (phase I: 56 ICH, 90 non-ICH) using allelic, haplotypic, and principal components analysis. Associated SNPs were then genotyped in 102 additional cases (phase II: 37 ICH, 65 non-ICH) and data combined for multivariable logistic regression. Minor alleles of 2 SNPs were associated with reduced risk of ICH presentation (rs314313 C, P=0.005; rs314308 T, P=0.0004). Overall, haplotypes were also significantly associated with ICH presentation (χ2=17.24, 6 df, P=0.008); 2 haplotypes containing the rs314308 T allele (GCCTGGGT, P=0.003; GTCTGGGC, P=0.036) were associated with reduced risk. In principal components analysis, 2 components explained 91% of the variance, and complemented haplotype results by implicating 4 SNPs at the 5′ end, including rs314308 and rs314313. These 2 SNPs were replicated in the phase II cohort, and combined data resulted in greater significance (rs314313, P=0.0007; rs314308, P=0.00008). SNP association with ICH presentation persisted after adjusting for age, sex, BAVM size, and deep venous drainage.

Conclusions

EPHB4 polymorphisms are associated with risk of ICH presentation in BAVM patients, warranting further study.

Keywords: cerebrovascular disorders, genetics, hemorrhage, receptors, risk factors

Brain arteriovenous malformations (BAVM) are an abnormal tangle of dysplastic vessels which shunt blood from the arterial to the venous circulation at low resistance with no intervening capillary bed. BAVMs are a relatively rare but important cause of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), which may result in death or permanent disability.1-3 They are thought to be sporadic vascular lesions, but familial occurrence has been described, supporting the hypothesis that genetic factors may play a role in the disease etiology and progression.4 We have previously reported association of BAVM hemorrhage with genetic polymorphisms in two inflammatory cytokine genes, tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin 6, suggesting inflammation may be important in ICH pathogenesis.5, 6 Furthermore, a number of studies have reported increased expression of various components of angiogenesis and inflammation pathways, in BAVM tissue.7, 8

EPHB4 encodes the EPH (erythropoietin-producing hepatocellular) receptor B4 (protein abbrev. EphB4), a tyrosine kinase receptor expressed in venous endothelial cells. As the cognate receptor for the arterial endothelial cell ligand ephrinB2 (encoded by EFNB2), EphB4 plays an important role in embryonic vascular development, especially in arterial-venous determination.9 Mutant mice that lack Ephb4 or Efnb2 die at embryonic day 9.5 as a result of defective angiogenic remodeling and vasculogenesis.10-12 The primitive blood vessels form; however, the primary vascular plexus fails to develop into a hierarchical system of large vessels and capillaries, resulting in a phenotype resembling BAVMs. Recently, a mouse model of perinatal brain arteriovenous fistula formation suggested that Notch and ephrinB2/EphB4 signaling pathways are essential for balanced arteriovenous development during blood vessel formation.13 EphrinB2/EphB4 signaling also regulates blood vessel morphogenesis and patterning of the postnatal vascular system, and functions in blood vessel permeability, inflammation, wound healing and pathological (tumor) angiogenesis.14-18 Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and Notch pathways influence venous EPHB4 gene expression;19, 20 thus, altered EphB4 signaling could affect the integrity of the vascular wall eventually leading to rupture. The purpose of this study was to investigate whether polymorphisms in the EPHB4 gene are associated with ICH risk at initial presentation in BAVM patients.

Materials and Methods

Patient Population

This was a cross-sectional study of Caucasian adult BAVM patients. The main group factor was whether or not the patients presented initially with ICH. ICH presentation was defined as new intracranial blood on computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. All other presentations without evidence of new bleeding, including seizure, focal ischemic deficit, headache, apparently unrelated symptoms or asymptomatic, incidental discovery were coded as unruptured. BAVM cases were recruited at University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) or at Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program of Northern California (KPMCP),21 and classified using standardized guidelines.22 The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of UCSF and KPMCP, and all subjects provided written, informed consent and blood or saliva specimens for genetic studies.

The study was conducted in 2 phases. In phase I, unrelated Caucasian BAVM cases (n=236; 90 ICH, 146 non-ICH) from our larger prospective BAVM registry were genotyped for 8 haplotype-tagging SNPs in EPHB4. 146 BAVM patients (56 ICH, 90 non-ICH) were successfully genotyped for all 8 SNPs and were included in the phase I cohort (haplotypic and principal components analyses described below required that all patients have genotypes for all 8 SNPs). Of the 90 patients excluded from phase I due to missing genotype data for one or more of the 8 SNPs, 63% of these (n=57) were subsequently included in the phase II cohort with complete data for the 2 significantly associated SNPs (Bonferroni corrected P<0.0063) along with 45 newly recruited patients (n=102 total patients, 37 ICH, 65 non-ICH). Subsequently, a joint analysis of 248 subjects was performed. To minimize the possibility of population stratification confounding our results, we included only Caucasian subjects in all analyses.

Polymorphism Selection and Genotyping

We selected eight haplotype-tagging SNPs (2 exonic, 4 intronic, and 2 intergenic) for a ∼29 kb region encompassing the EPHB4 gene. Using data from the HapMap project (http://hapmap.org), SNPs with a minor allele frequency >2% in the Caucasian CEU or Han Chinese in Beijing (CHB) samples were selected using the Tagger algorithm23 implemented in Haploview (dbSNP build 125 on NCBI human genome build 35),24 with pairwise selection and r2>0.8. Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood lymphocytes using a salt modification method (Gentra Systems). Polymorphism-spanning fragments were amplified by polymerase chain reaction and genotyped by Beckman Coulter SNPstream 48plex technology or by template-directed primer extension with fluorescence polarization detection. 6, 25 Genotyping was performed by investigators blinded to clinical status.

Statistical Analysis

Single Marker Association

SNP and haplotype association analyses were carried out using the software package plink v1.01 (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/∼purcell/plink/index.shtml).26 Individual SNPs were screened for association with ICH using the 1-degree of freedom (df) allelic χ2 test. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for each SNP. Correction for multiple testing was applied using the Bonferroni method. Nominal P values are reported with a corrected threshold for significance of P≤0.0063 (P=0.05/8).

When the true genetic model is not known, the codominant or additive genetic model (with fewer df) has been recommended.27 Therefore, to limit the number of tests and reduce the df for that test, all statistical analyses were performed assuming an additive genetic model, unless otherwise stated. Genetic variants significantly associated with ICH were further evaluated in a joint analysis of 248 patients using Intercooled Stata 9 statistical software (Stata Corp, Texas). Logistic regression analysis was performed for different genetic models (codominant, dominant, and additive), with further adjustments for age, sex (female versus male), and recruitment site (UCSF versus KPMCP). Additional adjustments for BAVM size and deep venous drainage were performed for the subset of 180 patients with complete morphologic data.

Haplotype Association

Eight-SNP fixed and 3-SNP sliding window haplotype frequencies were inferred using the expectation-maximization algorithm. Both a global likelihood ratio test (LRT) of association comparing the overall haplotype distribution between ICH and non-ICH BAVM cases, and haplotype-specific tests of association comparing each haplotype vs. all other haplotypes were performed. Degrees of freedom are equal to number of haplotypes tested minus 1 and significance was set at α < 0.05. Only common haplotypes with a minor allele frequency greater than 1% were considered for analysis.

Principal Components Analysis

Principal components (PC) analysis has been proposed as an alternative method for testing disease-SNP associations. This approach captures the linkage disequilibrium information within a candidate region without the need to predict haplotypes or determine haplotype blocks.28 Briefly, this method reduces the number of correlated SNPs into uncorrelated linear composite variables (PCs) that contain most of the variance. Using phase I data, we performed principal components analysis of the covariance matrix of 8 SNPs, with each SNP coded as having 0, 1 or 2 copies of the minor allele (additive genetic model) (Stata 9). PCs meeting a threshold of >0.80 variance explained were retained, as the small amount of variance explained by additional PCs does not provide enough information to justify the additional df required to include them.28 PCs were included as predictor variables in a test of association with ICH presentation using logistic regression analysis. A significant association of PCs implies that the combination of SNPs in the PC is associated with ICH. SNPs with larger factor loadings in the PC are interpreted as explaining the majority of the variation among the linear combination of SNPs.

Linkage Disequilibrium

The strength of linkage disequilibrium (LD) between SNPs at the EPHB4 locus was estimated by computing the correlation coefficient (r2) in Haploview using all genotype data from the 248 BAVM patients.29 An r2 value of 1 indicates perfect LD (complete correlation) whereas an r2 value of 0 indicates no LD.

Case-control Analysis

We also conducted a secondary case-control analysis of all 248 BAVM patients (93 ICH and 155 non-ICH) and 225 healthy controls of self-reported Caucasian ancestry. Controls were healthy volunteers from the same clinical catchment area without significant past medical history recruited for a pharmacogenetics study conducted at UCSF.30 Assuming an additive genetic model, logistic regression analysis was performed to obtain ORs and 95% CI for SNPs rs314313 and rs314308, adjusting for age and sex.

Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium

Adherence of genotype distribution to Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was evaluated for the 8 EPHB4 SNPs using χ2 goodness-of-fit tests. All SNPs were in HWE among cases except for rs314308 (P=0.01). However, this SNP was in HWE among healthy controls and was included in further analyses as deviations from HWE in cases could be indicative of a true association.31, 32

Results

Patient Population

The demographic and morphological characteristics for the BAVM patients are summarized in Table 1. ICH cases were younger than non-ICH cases (P=0.005) and had significantly smaller BAVM size (P=0.031); there was no significant difference in sex or presentation of deep venous drainage.

Table 1. Clinical Characteristics of BAVM Patients with and without ICH Presentation.

| Characteristic | BAVM Cases | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICH n=93 |

Non-ICH n=155 |

Total n=248 |

||

| Age at diagnosis, mean ±SD, y | 34.4 ± 17.6 | 40.8 ± 16.6 | 38.4 ± 17.2 | 0.005† |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 47 (50.5) | 69 (44.5) | 116 (46.8) | 0.358 |

| Female | 46 (49.5) | 86 (55.5) | 132 (53.2) | |

| BAVM size, mean size ±SD, cm* | 2.6 ± 1.5 | 3.1 ± 1.5 | 2.9 ± 1.5 | 0.031† |

| Deep venous drainage* | ||||

| Yes | 18 (23.1) | 19 (15.3) | 37 (18.3) | 0.165 |

| No | 60 (76.9) | 105 (84.7) | 165 (81.7) | |

Values are No. and (percent), unless indicated otherwise.

Counts do not add up to total due to missing data. A total of 180 patients had complete phenotypic data.

P, χ2 test, except for

t test.

Phase I Analyses

We genotyped eight haplotype-tagging SNPs located in the EPHB4 gene in 56 ICH and 90 non-ICH BAVM cases. All SNPs were polymorphic (minor allele frequency >1%), and genotype frequencies (Table 2) differed significantly between ICH and non-ICH cases for rs314353 (P=0.010), rs314308 (P=0.006), and rs314313 (P=0.012).

Table 2. Genotype Frequencies of EPHB4 Polymorphisms in Phase I BAVM Patients by ICH Presentation.

| ICH n (%) |

Non-ICH n (%) |

Total n (%) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs314346 | ||||

| TT | 7 (12.5) | 26 (28.9) | 33 (22.6) | 0.056 |

| CT | 34 (60.7) | 48 (53.3) | 82 (56.2) | |

| CC | 15 (26.8) | 16 (17.8) | 31 (21.2) | |

| rs314353 | ||||

| GG | 9 (16.1) | 36 (40.0) | 45 (30.8) | 0.010 |

| AG | 37 (66.1) | 42 (46.7) | 79 (54.1) | |

| AA | 10 (17.9) | 12 (13.3) | 22 (15.1) | |

| rs2230585 | ||||

| GG | 18 (32.1) | 38 (42.2) | 56 (38.4) | 0.274 |

| AG | 28 (50.0) | 43 (47.8) | 71 (48.6) | |

| AA | 10 (17.9) | 9 (10.0) | 19 (13.0) | |

| rs144173 | ||||

| GG | 14 (25.0) | 37 (41.1) | 51 (34.9) | 0.116 |

| AG | 32 (57.1) | 43 (47.8) | 75 (51.4) | |

| AA | 10 (17.9) | 10 (11.1) | 20 (13.7) | |

| rs314308 | ||||

| CC | 39 (69.6) | 41 (45.6) | 80 (54.8) | 0.006 |

| CT | 15 (26.8) | 33 (36.7) | 48 (32.9) | |

| TT | 2 (3.6) | 16 (17.8) | 18 (12.3) | |

| rs2250818 | ||||

| CC | 25 (44.6) | 51 (56.7) | 76 (52.1) | 0.352 |

| CT | 27 (48.2) | 33 (36.7) | 60 (41.1) | |

| TT | 4 (7.1) | 6 (6.7) | 10 (6.8) | |

| rs314313 | ||||

| TT | 39 (69.6) | 40 (44.4) | 79 (54.1) | 0.012 |

| CT | 14 (25.0) | 41 (45.6) | 55 (37.7) | |

| CC | 3 (5.4) | 9 (10.0) | 12 (8.2) | |

| rs2247445 | ||||

| GG | 25 (44.6) | 52 (57.8) | 77 (52.7) | 0.303 |

| AG | 27 (48.2) | 33 (36.7) | 60 (41.1) | |

| AA | 4 (7.1) | 5 (5.6) | 9 (6.2) | |

P value, χ2 test

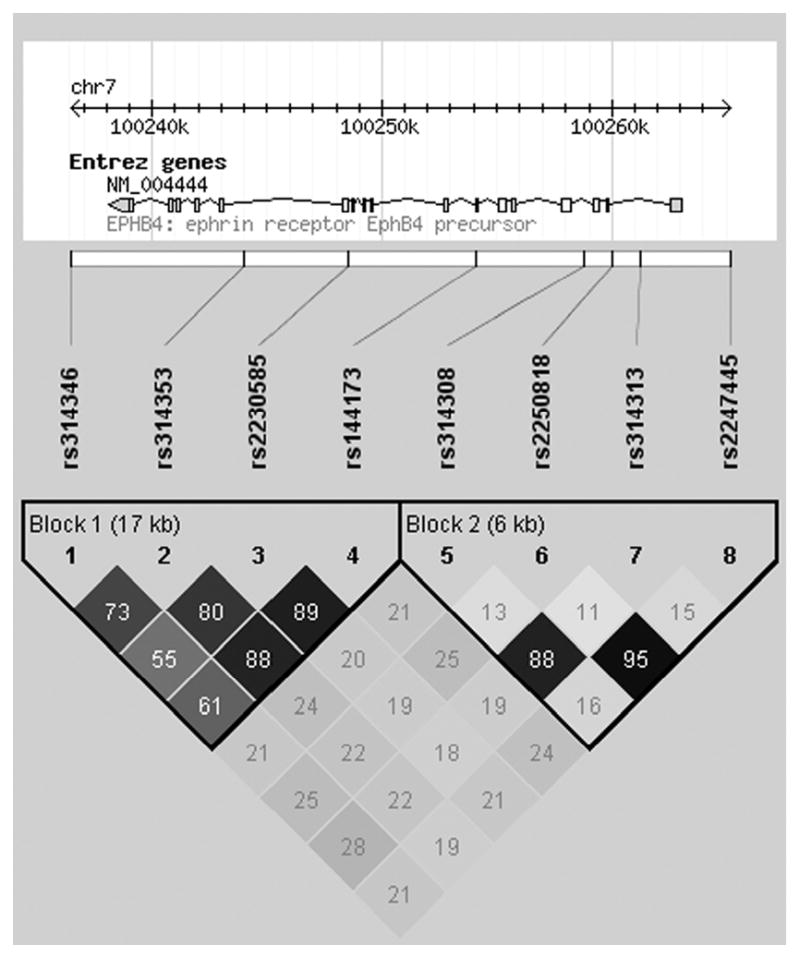

Allelic association analysis identified 4 markers nominally associated with ICH presentation (P<0.05, Table 3). The minor alleles of 2 SNPs remained significantly associated with reduced risk of ICH presentation after Bonferroni correction: rs314313 (C; OR=0.45, 95% CI=0.25 – 0.79) and rs314308 (T; OR=0.36, 95% CI=0.20 – 0.65). These two SNPs, located in intron 1 and intron 3, respectively, were in high LD (r2=0.88, Figure 1), and located in the same LD block.

Table 3. Phase I Allelic Association of EPHB4 Polymorphisms with ICH Presentation.

| Polymorphism | ICH MAF |

Non-ICH MAF |

OR | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs314346_C | 0.571 | 0.444 | 1.67 | 1.04-2.68 | 0.0348 |

| rs314353_A | 0.509 | 0.367 | 1.79 | 1.11-2.89 | 0.0167 |

| rs2230585_A | 0.429 | 0.339 | 1.46 | 0.90-2.38 | 0.1234 |

| rs144173_A | 0.464 | 0.350 | 1.61 | 0.99-2.61 | 0.0520 |

| rs314308_T | 0.170 | 0.361 | 0.36 | 0.20-0.65 | 0.0004* |

| rs2250818_T | 0.313 | 0.250 | 1.36 | 0.81-2.30 | 0.2443 |

| rs314313_C | 0.179 | 0.328 | 0.45 | 0.25-0.79 | 0.0053* |

| rs2247445_A | 0.313 | 0.239 | 1.45 | 0.86-2.45 | 0.1669 |

MAF, minor allele frequency.

Significant after Bonferroni correction at P<0.0063.

Figure 1. Linkage Disequilibrium Structure for EPHB4 Locus.

EPHB4 SNPs are represented in order on the chromosome. The strength of linkage disequilibrium between SNPs is represented both numerically and by the depth of shading (r2) computed using all genotype data from the 248 BAVM patients. Two haplotype blocks exist in this EPHB4 region: block 1, SNPs rs314346 – rs144173, and block 2, rs314308 – rs2247445.

Next, we performed haplotype analyses in attempt to refine the association signal. Overall, seven common haplotypes were predicted with frequencies between 2-37%. A global test of association comparing the overall haplotype distribution between ICH and non-ICH cases was significant (χ2=17.24, df=6, P=0.008). Two haplotypes containing the minor allele of rs314308 (T) were associated with reduced risk (GCCTGGGT, P=0.003; and GTCTGGGC, P=0.036) of ICH presentation (Table 4). The more common haplotype (GCCTGGGT, frequency ICH=0.157; frequency non-ICH=0.318) was consistent with the individual SNP analysis, as it contains the minor alleles for the two significantly associated SNPs. Sliding windows of 3-SNP haplotypes excluded SNPs rs314346 and rs314353, as the first two windows including these SNPs were not associated with ICH status (data not shown).

Table 4. Phase I EPHB4 Fixed Window Haplotype Association with ICH Presentation.

| Frequency Estimates | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Haplotype (5′ → 3′) | ICH | Non-ICH | P Value* |

| Global P Value | 0.008 | ||

| Specific Haplotypes | |||

| GCCTGGGT | 0.157 | 0.318 | 0.003 |

| GTCTGGGC | 0.000 | 0.040 | 0.036 |

| ATTCGGAC | 0.046 | 0.011 | 0.065 |

| GTCCAAAC | 0.417 | 0.330 | 0.138 |

| GTCCGGGT | 0.278 | 0.233 | 0.397 |

| GTCCGGGC | 0.065 | 0.045 | 0.479 |

| GTCCAGAC | 0.037 | 0.023 | 0.479 |

Specific haplotype P value is a comparison of each individual haplotype to all other haplotypes

To complement haplotype analysis, we performed principal components analysis, which identified eight PCs. The first two PCs explained 91% of the total variance in the locus. The third PC explained 5.4% of the variance, while the remaining five PCs together explained only 3.7% of the total variance. Therefore, only the first two PCs were retained for further analysis.

The first PC explained 56.9% of the variance, and all 8 SNPs had approximately equal factor loadings (Table 5). The second PC explained an additional 34.1% of the variance, with the four SNPs at the 5′ end of EPHB4 having higher factor loadings (>45%). rs314313 and rs314308 had positive factor loadings while rs2247445 and rs2250818 had negative factor loadings, suggesting that the minor alleles present on positively loading SNPs correlated with major alleles on negatively loading SNPs on PC2. Both PC1 (P=0.013) and PC2 (P=0.021) were independently associated with ICH when used directly as predictor variables for ICH presentation in a logistic regression model.

Table 5. Phase I Principal Components Analysis of 8 SNPs within the EPHB4 Locus.

| Principal Component | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymorphism | 1 | 2 | |

| rs314346 | 0.4178* | 0.0593 | |

| rs314353 | 0.4539 | 0.0401 | |

| rs2230585 | 0.4399 | 0.0759 | |

| rs144173 | 0.4542 | 0.0747 | |

| rs314308 | -0.3045 | 0.4977 | |

| rs2250818 | -0.1618 | -0.5184 | |

| rs314313 | -0.2763 | 0.4467 | |

| rs2247445 | -0.1563 | -0.5172 | |

| Variance (%) | 56.9 | 34.1 | |

| Logistic Regression: | |||

| Global P Value = 0.003 | P = 0.013 | P = 0.021 | |

Values are principal component loadings

Joint Analysis

To replicate the findings, SNPs rs314313 and rs314308 were genotyped in a phase II cohort of BAVM cases (37 ICH, 65 non-ICH). Phase I and phase II cases were similar with respect to age, sex, hemorrhagic status at initial presentation, BAVM size, and deep venous drainage (Supplemental Table). Allele and genotype frequencies were similar in both cohorts. Both SNPs were associated with ICH presentation in the phase II cohort (rs314313: OR=0.53, 95% CI=0.28 – 1.00, P=0.051; rs314308: OR=0.54, 95% CI=0.29 – 1.00, P=0.050) with risk estimates similar to those observed in the phase I cohort presented in Table 3.

We then evaluated both cohorts together as a combined dataset, which included 93 ICH and 155 non-ICH cases. SNPs rs314313 (OR=0.48, 95% CI= 0.31 – 0.74, P=0.0007) and rs314308 (OR=0.43, 95% CI=0.28 – 0.66, P=0.00008) were significantly associated with ICH. The co-dominant and dominant models for the two associated SNPs are presented in Table 6. Compared to the homozygote major allele group, the OR for the heterozygote and homozygote minor allele groups suggest an additive effect, with risk estimates approximately halving for each copy of the minor allele.

Table 6. Association of EPHB4 Gene Polymorphisms and Risk of ICH in Combined Dataset.

| Polymorphism | OR | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs314313 | |||

| TT | 1.00 (reference) | n/a | 0.003* |

| CT | 0.44 | 0.25 – 0.77 | 0.004 |

| CC | 0.29 | 0.10 – 0.82 | 0.020 |

| Any C vs. TT | 0.41 | 0.24 – 0.69 | 0.001† |

| rs314308 | |||

| CC | 1.00 (reference) | n/a | 0.001* |

| CT | 0.52 | 0.30 – 0.92 | 0.024 |

| TT | 0.20 | 0.07 – 0.55 | 0.002 |

| Any T vs. CC | 0.42 | 0.25 – 0.71 | 0.001† |

Co-dominant model, 2 df test

Dominant model, 1 df test

Multivariable logistic regression analysis, assuming an additive genetic model and adjusting for age, sex and recruitment site in the combined cohort, yielded similar results for rs314313 (OR=0.51, 95% CI=0.33 – 0.79, P=0.002) and for rs314308 (OR=0.49, 95% CI=0.32 – 0.74, P=0.001). Further adjustments for BAVM size, and deep venous drainage in the subset of 180 patients with complete morphologic data also did not change results (rs314313: OR=0.53, 95% CI=0.32 – 0.88, P=0.014; rs314308: OR=0.48, 95% CI=0.29 – 0.79, P=0.004).

Case-control Analyses

To determine if SNPs rs314313 and rs314308 were also associated with BAVM disease susceptibility, we performed a case-control analysis. Genotype frequencies for the Caucasian controls (rs314313: TT 41.3%; CT 48.5%; CC 10.2% and rs314308: CC 41.3%; CT 43.1%; TT 15.6%) were similar to BAVM cases reported in Table 2, and both SNPs were in HWE in controls. However, controls were younger than cases (30.5 ± 5.7 years vs. 38.4 ± 17.2 years, P<0.001), with a similar sex distribution (42.7% vs. 46.8% male, P=0.370).

When all 248 BAVM cases (ICH and non-ICH combined) were compared to controls in an additive genetic model adjusting for age and sex, SNPs rs314308 (OR=0.76, 95% CI=0.58-0.99, P=0.046) and rs314313 (OR=0.76, 95% CI=0.57 – 1.02, P=0.066) were marginally associated with reduced risk of BAVM. However, the overall reduced risk appeared to be driven by the difference between the 93 ruptured BAVM cases and controls: rs314313 (OR=0.50, 95% CI=0.33 – 0.77, P=0.002) and rs314308 (OR=0.48, 95% CI=0.32 – 0.72, P<0.001). SNPs were not associated with unruptured BAVM risk when 155 non-ICH cases were compared to controls: rs314313 (OR=0.94, 95% CI=0.67 – 1.32, P=0.713) and rs314308 (OR=0.95, 95% CI=0.70 – 1.30, P=0.746). These findings suggest the SNP association results are specific to ICH presentation and not BAVM status.

Discussion

We provide the first report of an association between polymorphic variants in the EPHB4 gene with risk of ICH at presentation in patients harboring BAVM. Using three different statistical approaches, we identified 2 SNPs (rs314313 and rs314308) located proximal to the 5′ end of the EPHB4 gene that contribute to a 50-60% reduction in risk of ICH in BAVM patients who carry the minor alleles. Furthermore, case-control analyses support the findings that these two SNPs influence hemorrhagic risk, but not BAVM risk.

The two associated EPHB4 SNPs are located in intronic regions not well-conserved with no known function. Hence, they are likely not causal alleles, but surrogate markers in linkage disequilibrium with functional polymorphisms located elsewhere in the EPHB4 gene or closely neighboring gene. Interactions between EPHB4 and genes that map to the same chromosomal region (+/- 10 Mb) have not been reported. However, there are examples in the literature of non-coding sequences functioning as gene regulatory elements.33 The primary transcript of the EPHB4 gene is alternatively spliced. However, the two intronic polymorphisms found to be associated with reduced risk of ICH presentation in BAVM patients are not located near a splice site; thus are not likely to influence splicing efficiency. The SNPs are located adjacent to exons that encode the extracellular ligand binding domain. One explanation for our findings is that these SNPs may be in disequilibrium with other EPHB4 SNPs located in exons that may be protective of ICH by affecting EPHB4 gene or encoded protein expression, or influencing receptor-ligand binding. Changes in ephrinB2/EphB4 interaction may have an effect on vessel wall stability and response to shear stress that could make vessels prone to hemorrhage.

The role of Eph receptors and their ligands in vascular function became apparent when genetic loss-of-function experiments revealed ephrinB2 and its receptors (EphB2, EphB3 and EphB4) control arteriovenous assembly and differentiation during development; both ephb4-/- and efnb2-/- embryos suffer from severe vascular phenotypes including fatal abnormalities of capillary formation.10-12 Eph receptor-ligand signaling is not limited to vascular development, and has been implicated in adult vascular biology including in tumor angiogenesis and progression,14, 34-36 and more recently in monocyte adhesion and transmigration through the vascular endothelium.37 Additional studies have implicated ephrin/Eph receptor interactions in inflammation.18

Inflammation contributes to the pathogenesis of several vascular malformations including cerebral cavernous malformations,38 intracranial aneurysms, 39, 40 and abdominal aortic aneurysms.41, 42 Recent studies have demonstrated the presence of inflammatory cells (neutrophils and macrophages) in BAVM tissue, suggesting a role for inflammation in BAVM disease progression and rupture.43 Additionally, we have previously reported an association of the IL6 -174 GG genotype with BAVM hemorrhagic presentation, and IL-1β promoter polymorphisms associated with increased risk of subsequent ICH and BAVM susceptibility, further implicating inflammatory processes in BAVM rupture.6, 44

While ephrins and Eph receptors are fundamentally involved in embryonic vascular development, it is now known that they are abundantly expressed in both endothelial and epithelial cells in adult mammals, and studies suggest that Eph receptors may play a role in inflammation by regulating the permeability of endothelial and epithelial barriers.18 Rat models have shown that during later stages of inflammation there is a decrease in the expression of several Eph receptors, including EphB4, on leukocytes and endothelial cells, promoting adhesion of leukocytes to endothelial cells.18 These reports suggest that EphB4 could play a regulatory role in maintaining the integrity of the vascular wall. We speculate that dysregulated EphB4 function, caused either by structural changes in the protein, changes in the gene or protein expression or altered receptor signaling could result in intracranial vessel abnormalities that increase the risk of BAVM hemorrhage.

Our study had several limitations: (1) the analysis was restricted to Caucasians, and results may not extend to other race/ethnic groups; (2) false positive associations could be introduced by unrecognized population substructure differences between ICH and non-ICH cases; and (3) given the small size of the cohort, replication in additional cohorts is needed to provide a more reliable estimate of the effect size and rule out false positive results. Future studies will need to evaluate a larger number of BAVM patients and assess whether these EPHB4 SNPs also confer future ICH risk, as well as examine functionality.

In conclusion, we identified 2 SNPs located at the 5′ end of EPHB4, rs314313 and rs314308, associated with a reduced risk of hemorrhagic presentation in Caucasian BAVM patients, but not with BAVM susceptibility. These findings suggest that genetic variation in EPHB4 contributes to the risk of hemorrhage in patients with BAVM and warrant further investigation into the role of Eph receptors in BAVM hemorrhage.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the UCSF BAVM Study Project members (http://avm.ucsf.edu), KPMCP BAVM Study Project members for their collaboration, and patients for their participation.

Sources of Funding This study was supported in part by an American Stroke Association Bugher Fellowship and National Institutes of Health Ruth L. Kirschstein NRSA T32 Award (S.W.), and National Institutes of Health (National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke) grants K23 NS058357 (H.K.), R01 NS034949 (W.L.Y.), and P01 NS044155 (W.L.Y.).

Footnotes

Journal Subject Codes: [50] Cerebral Aneurysm, AVM, & Subarachnoid hemorrhage; [62] Intracerebral Hemorrhage; [89] Genetics of cardiovascular disease

Disclosures: None.

Brain arteriovenous malformations (BAVMs) are a relatively rare but important cause of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) in young adults, a potentially life-threatening disorder. While the pathogenesis of BAVM and ICH is unknown, candidate genes that function in the development or maintenance of the vasculature may serve as markers of disease risk. The EPH receptor B4 (encoded by EPHB4) is involved in the development of the vasculature and functions in blood vessel permeability, inflammation, wound healing and pathological angiogenesis. However, the role of EPHB4 gene polymorphisms as risk factors for BAVM and ICH has not yet been studied. In this genetic association study, we tested 8 single nucleotide polymorphisms in the EPHB4 gene in 248 Caucasian BAVM patients (93 ICH, 155 non-ICH) and 225 healthy controls for associations with BAVM and ICH at initial presentation. We found that 2 SNPs and haplotypes in EPHB4 were associated with a reduced risk of hemorrhagic presentation in Caucasian BAVM patients, but not with disease susceptibility. Our observations suggest that the risk of ICH presentation may differ between individuals with BAVM, depending on genetic risk factors that may affect the development and/or maintenance of the vasculature.

References

- 1.Choi JH, Mohr JP. Brain arteriovenous malformations in adults. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:299–308. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleetwood IG, Steinberg GK. Arteriovenous malformations. Lancet. 2002;359:863–873. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07946-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rost NS, Greenberg SM, Rosand J. The genetic architecture of intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2008;39:2166–2173. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.501650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Beijnum J, van der Worp HB, Schippers HM, van Nieuwenhuizen O, Kappelle LJ, Rinkel GJ, Berkelbach van der Sprenkel JW, Klijn CJ. Familial occurrence of brain arteriovenous malformations: a systematic review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:1213–1217. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.112227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Achrol AS, Pawlikowska L, McCulloch CE, Poon KY, Ha C, Zaroff JG, Johnston SC, Lee C, Lawton MT, Sidney S, Marchuk D, Kwok PY, Young WL. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-238G>A promoter polymorphism is associated with increased risk of new hemorrhage in the natural course of patients with brain arteriovenous malformations. Stroke. 2006;37:231–234. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000195133.98378.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pawlikowska L, Tran MN, Achrol AS, McCulloch CE, Ha C, Lind DL, Hashimoto T, Zaroff J, Lawton MT, Marchuk DA, Kwok PY, Young WL. Polymorphisms in genes involved in inflammatory and angiogenic pathways and the risk of hemorrhagic presentation of brain arteriovenous malformations. Stroke. 2004;35:2294–2300. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000141932.44613.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hashimoto T, Lawton MT, Wen G, Yang GY, Chaly T, Jr, Stewart CL, Dressman HK, Barbaro NM, Marchuk DA, Young WL. Gene microarray analysis of human brain arteriovenous malformations. Neurosurgery. 2004;54:410–423. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000103421.35266.71. discussion 423-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shenkar R, Elliott JP, Diener K, Gault J, Hu LJ, Cohrs RJ, Phang T, Hunter L, Breeze RE, Awad IA. Differential gene expression in human cerebrovascular malformations. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:465–478. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000044131.03495.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams RH. Molecular control of arterial-venous blood vessel identity. J Anat. 2003;202:105–112. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2003.00137.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerety SS, Wang HU, Chen ZF, Anderson DJ. Symmetrical mutant phenotypes of the receptor EphB4 and its specific transmembrane ligand ephrin-B2 in cardiovascular development. Mol Cell. 1999;4:403–414. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80342-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adams RH, Wilkinson GA, Weiss C, Diella F, Gale NW, Deutsch U, Risau W, Klein R. Roles of ephrinB ligands and EphB receptors in cardiovascular development: demarcation of arterial/venous domains, vascular morphogenesis, and sprouting angiogenesis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:295–306. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang HU, Chen ZF, Anderson DJ. Molecular distinction and angiogenic interaction between embryonic arteries and veins revealed by ephrin-B2 and its receptor Eph-B4. Cell. 1998;93:741–753. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81436-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim YH, Hu H, Guevara-Gallardo S, Lam MT, Fong SY, Wang RA. Artery and vein size is balanced by Notch and ephrin B2/EphB4 during angiogenesis. Development. 2008;135:3755–3764. doi: 10.1242/dev.022475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erber R, Eichelsbacher U, Powajbo V, Korn T, Djonov V, Lin J, Hammes HP, Grobholz R, Ullrich A, Vajkoczy P. EphB4 controls blood vascular morphogenesis during postnatal angiogenesis. EMBO J. 2006;25:628–641. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gale NW, Baluk P, Pan L, Kwan M, Holash J, DeChiara TM, McDonald DM, Yancopoulos GD. Ephrin-B2 selectively marks arterial vessels and neovascularization sites in the adult, with expression in both endothelial and smooth-muscle cells. Dev Biol. 2001;230:151–160. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nikolova Z, Djonov V, Zuercher G, Andres AC, Ziemiecki A. Cell-type specific and estrogen dependent expression of the receptor tyrosine kinase EphB4 and its ligand ephrin-B2 during mammary gland morphogenesis. J Cell Sci. 1998;111(Pt 18):2741–2751. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.18.2741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogawa K, Pasqualini R, Lindberg RA, Kain R, Freeman AL, Pasquale EB. The ephrin-A1 ligand and its receptor, EphA2, are expressed during tumor neovascularization. Oncogene. 2000;19:6043–6052. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ivanov AI, Romanovsky AA. Putative dual role of ephrin-Eph receptor interactions in inflammation. IUBMB Life. 2006;58:389–394. doi: 10.1080/15216540600756004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang G, Zhou J, Fan Q, Zheng Z, Zhang F, Liu X, Hu S. Arterial-venous endothelial cell fate is related to vascular endothelial growth factor and Notch status during human bone mesenchymal stem cell differentiation. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:2957–2964. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Limbourg A, Ploom M, Elligsen D, Sorensen I, Ziegelhoeffer T, Gossler A, Drexler H, Limbourg FP. Notch ligand Delta-like 1 is essential for postnatal arteriogenesis. Circ Res. 2007;100:363–371. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000258174.77370.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim H, Sidney S, McCulloch CE, Poon KY, Singh V, Johnston SC, Ko NU, Achrol AS, Lawton MT, Higashida RT, Young WL. Racial/ethnic differences in longitudinal risk of intracranial hemorrhage in brain arteriovenous malformation patients. Stroke. 2007;38:2430–2437. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.485573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joint Writing Group of the Technology Assessment Committee American Society of Interventional and Therapeutic Neuroradiology, Joint Section on Cerebrovascular Neurosurgery a Section of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons and Congress of Neurological Surgeons, Section of Stroke and the Section of Interventional Neurology of the American Academy of Neurology. Reporting terminology for brain arteriovenous malformation clinical and radiographic features for use in clinical trials. Stroke. 2001;32:1430–1442. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.6.1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Bakker PI, Yelensky R, Pe'er I, Gabriel SB, Daly MJ, Altshuler D. Efficiency and power in genetic association studies. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1217–1223. doi: 10.1038/ng1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsu TM, Kwok PY. Homogeneous primer extension assay with fluorescence polarization detection. Methods Mol Biol. 2003;212:177–187. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-327-5:177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PI, Daly MJ, Sham PC. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lunetta KL. Genetic association studies. Circulation. 2008;118:96–101. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.700401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gauderman WJ, Murcray C, Gilliland F, Conti DV. Testing association between disease and multiple SNPs in a candidate gene. Genet Epidemiol. 2007;31:383–395. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Devlin B, Risch N. A comparison of linkage disequilibrium measures for fine-scale mapping. Genomics. 1995;29:311–322. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.9003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shu Y, Brown C, Castro R, Shi R, Lin E, Owen R, Sheardown S, Yue L, Burchard E, Brett C, Giacomini K. Effect of genetic variation in the organic cation transporter 1, OCT1, on metformin pharmacokinetics. Mol Ther. 2008;83:273–280. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee WC. Searching for disease-susceptibility loci by testing for Hardy-Weinberg disequilibrium in a gene bank of affected individuals. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:397–400. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Czika W, Weir BS. Properties of the multiallelic trend test. Biometrics. 2004;60:69–74. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2004.00166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pennacchio LA, Ahituv N, Moses AM, Prabhakar S, Nobrega MA, Shoukry M, Minovitsky S, Dubchak I, Holt A, Lewis KD, Plajzer-Frick I, Akiyama J, De Val S, Afzal V, Black BL, Couronne O, Eisen MB, Visel A, Rubin EM. In vivo enhancer analysis of human conserved non-coding sequences. Nature. 2006;444:499–502. doi: 10.1038/nature05295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kertesz N, Krasnoperov V, Reddy R, Leshanski L, Kumar SR, Zozulya S, Gill PS. The soluble extracellular domain of EphB4 (sEphB4) antagonizes EphB4-EphrinB2 interaction, modulates angiogenesis, and inhibits tumor growth. Blood. 2006;107:2330–2338. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martiny-Baron G, Korff T, Schaffner F, Esser N, Eggstein S, Marme D, Augustin HG. Inhibition of tumor growth and angiogenesis by soluble EphB4. Neoplasia. 2004;6:248–257. doi: 10.1593/neo.3457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noren NK, Lu M, Freeman AL, Koolpe M, Pasquale EB. Interplay between EphB4 on tumor cells and vascular ephrin-B2 regulates tumor growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:5583–5588. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401381101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pfaff D, Heroult M, Riedel M, Reiss Y, Kirmse R, Ludwig T, Korff T, Hecker M, Augustin HG. Involvement of endothelial ephrin-B2 in adhesion and transmigration of EphB-receptor-expressing monocytes. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:3842–3850. doi: 10.1242/jcs.030627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shenkar R, Shi C, Check IJ, Lipton HL, Awad IA. Concepts and hypotheses: inflammatory hypothesis in the pathogenesis of cerebral cavernous malformations. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:693–702. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000298897.38979.07. discussion 702-693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hashimoto T, Meng H, Young WL. Intracranial aneurysms: links between inflammation, hemodynamics and vascular remodeling. Neurol Res. 2006;28:372–380. doi: 10.1179/016164106X14973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kataoka K, Taneda M, Asai T, Kinoshita A, Ito M, Kuroda R. Structural fragility and inflammatory response of ruptured cerebral aneurysms. A comparative study between ruptured and unruptured cerebral aneurysms. Stroke. 1999;30:1396–1401. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.7.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lenk GM, Tromp G, Weinsheimer S, Gatalica Z, Berguer R, Kuivaniemi H. Whole genome expression profiling reveals a significant role for immune function in human abdominal aortic aneurysms. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:237. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shimizu K, Mitchell RN, Libby P. Inflammation and cellular immune responses in abdominal aortic aneurysms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:987–994. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000214999.12921.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen Y, Zhu W, Bollen AW, Lawton MT, Barbaro NM, Dowd CF, Hashimoto T, Yang GY, Young WL. Evidence for inflammatory cell involvement in brain arteriovenous malformations. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:1340–1349. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000333306.64683.b5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim H, Hysi PG, Pawlikowska L, Poon A, Burchard EG, Zaroff JG, Sidney S, Ko NU, Achrol AS, Lawton MT, McCulloch CE, Kwok PY, Young WL. Common variants in interleukin-1-beta gene are associated with intracranial hemorrhage and susceptibility to brain arteriovenous malformation. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;27:176–182. doi: 10.1159/000185609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.