Abstract

Background

Physicians are encouraged to counsel overweight and obese patients to lose weight.

Purpose

It was examined whether discussing weight and use of motivational-interviewing techniques (e.g., collaborating, reflective listening) while discussing weight predicted weight loss 3 months after the encounter.

Methods

40 primary care physicians and 461 of their overweight or obese patient visits were audio recorded between December 2006 and June 2008. Patient actual weight at the encounter and 3 months after the encounter (n=426), whether weight was discussed, physicians’ use of Motivational-Interviewing techniques, and patient, physician and visit covariates (e.g., race, age, specialty) were assessed. This was an observational study and data were analyzed in April 2009.

Results

No differences in weight loss were found between patients whose physicians discussed weight or did not. Patients whose physicians used motivational interviewing–consistent techniques during weight-related discussions lost weight 3 months post-encounter; those whose physician used motivational interviewing–inconsistent techniques gained or maintained weight. The estimated difference in weight change between patients whose physician had a higher global “motivational interviewing–Spirit” score (e.g., collaborated with patient) and those whose physician had a lower score was 1.6 kg (95% CI=−2.9, −0.3, p=.02). The same was true for patients whose physician used reflective statements 0.9 kg (95% CI=−1.8, −0.1, p=.03). Similarly, patients whose physicians expressed only motivational interviewing–consistent behaviors had a difference in weight change of 1.1 kg (95% CI=−2.3, 0.1, p=.07) compared to those whose physician expressed only motivational interviewing–inconsistent behaviors (e.g., judging, confronting).

Conclusions

In this small observational study, use of motivational-interviewing techniques during weight loss discussions predicted patient weight loss.

Over 60% of Americans are overweight or obese.1 Physician counseling may help patients lose weight as studies indicate that physician counseling leads to increases in physical activity and improvement in nutrition.2–5 Although many studies have examined patient, physician, or chart reports of weight loss counseling,2, 6–9, 10 few have examined actual weight-loss conversations. A recent study found that physicians counseled one third of the overweight and obese patients to lose weight.11 However, physicians may feel frustrated about such counseling as they rarely see their patients lose weight.12, 13

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force14 recommends that physicians provide “intensive counseling.” One type of counseling that has been effective for alcohol use and smoking15 and has shown promise in weight loss16 is motivational interviewing. Motivational interviewing is designed to motivate those ambivalent about changing behavior and is a collaborative approach to help patients reach their own goals. Motivational interviewing includes understanding the patients’ perspective, accepting patients’ motivation or lack of motivation for changing, helping patients find their own solutions to problems and discover their own internal motivation to change, and affirming the patients’ own freedom to change. Motivational interviewing–consistent behaviors include praising (e.g., “That’s great that you lost four pounds!”), collaborating (e.g., “I’m here to help you achieve your goals. What can I do to help?”), and evoking “change statements from patients (e.g., “What are some good things that could come from your losing weight?”). Motivational interviewing–inconsistent behaviors include judging, confronting, and providing advice without permission. For instance, before physicians give suggestions for what patients could do, to respect patient autonomy, physicians should ask patients permission about whether patients want to hear the suggestions. However, there have been no studies examining the relationship between physician counseling behaviors and subsequent patient weight loss. Further, there is a dearth of well-designed trials examining motivational interviewing in healthcare settings.17 The aims of this observational study were to determine whether physicians discuss weight, and whether discussing weight and using motivational-interviewing techniques during weight-related conversations was related to weight loss 3 months after the encounter.

Methods

Recruitment: Physicians

Project CHAT (Communicating Health: Analyzing Talk) was approved by Duke University Medical Center IRB. Primary care physicians (n=54) from academically affiliated and community-based practices were told the study would examine how they address preventive health (not that it was specifically about weight-loss counseling). When asked what the study was about, only one physician and 7 patients guessed it was about weight. Forty agreed to be in the study (74%) while 14 refused (new to practice, recently ill, not enough patients, leaving practice, patient flow concern, do not support research). Participating physicians gave written consent, completed a baseline questionnaire, and provided an electronic signature for generating letters to their patients. Physicians were paid $50 for completing the questionnaires, and $20 for each audio-recorded encounter. Per physician, 11–12 patient visits were audio-recorded with an attempt to obtain equal proportions of overweight and obese patients.

Recruitment: Patients

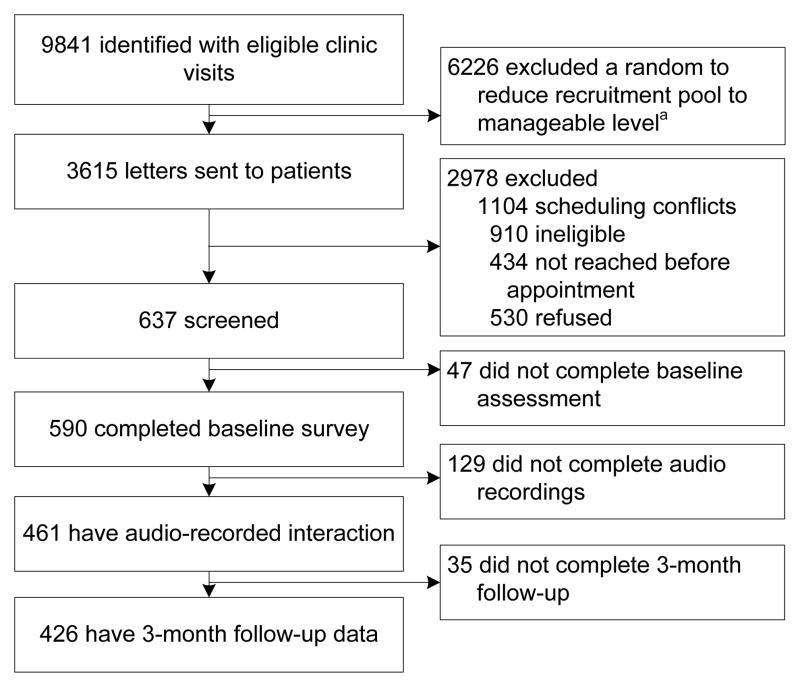

Physicians’ electronic clinic rosters were reviewed weekly to identify patients scheduled for non-acute visits. A letter introducing the study to patients included a toll-free number to refuse contact. One week later, patients were called to review eligibility and administer the baseline questionnaire. Eligible patients were aged ≥18 years, English-speaking, cognitively competent, not pregnant and had a BMI ≥ 25. Before the encounter, patients provided written consent. Immediately following the encounter, they completed a post-encounter questionnaire. Vital signs (e.g., blood pressure, temperature (to mask the focus on weight)) were taken, and $10 was provided for completing the questionnaire (Figure 1). Weight and vital signs were assessed 3 months after the encounter. Patients were paid $20 for doing this survey. Three months was chosen to allow enough time for patients to change but not too much time to not be able to attribute the changes to the physician counseling. Data collection occurred between December 2006 and June 2008. Data analysis occurred in April 2009.

Figure 1.

Recruitment/participant flow

Coding audio recordings: Quantity

The presence of three primary weight-related topics were coded: nutrition, physical activity, and BMI/weight (e.g., “With my work schedule, I am always on the road and often end up having to eat out for all meals” and “Looking at your chart here, your BMI is 26.5, which classifies you as overweight”). Total time for each encounter spent on weight-related topics was calculated. Total time each patient was in the room with the physician was recorded.

Coding audio recordings: Quality

Motivational Interviewing

Two independent coders, with 30 hours of training, assessed motivational interviewing using the Motivational Interview Treatment Integrity scale (MITI).18 The MITI has been shown to be a reliable and valid assessment of motivational-interviewing techniques.19, 20 Inter-rater reliability was assessed using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) to take into account the differences in ratings for individual segments, along with the correlation between raters.21 They assessed global ratings of “Empathy” (1–5 scale, ICC= .70) and “motivational-interviewing Spirit,” (1–5 scale, ICC=.81), which included three components: evocation (eliciting patients’ own reasons for change), collaboration (acting as partners) and autonomy (conveying that change comes only from patients).

Coders also identified six physician behaviors including: (1) closed questions (yes/no, ICC=.82), (2) open questions (ICC=.78), (3) simple reflections (conveys understanding but adds no new meaning, ICC=.45), (4) complex reflections (conveys understanding and adds substantial meaning, ICC=1.0), (5) motivational interviewing–consistent behaviors (asking permission, affirming, providing supportive statements, and emphasizing control, ICC=.70), and (6) motivational interviewing–inconsistent behaviors (advising without permission, confronting, and directing, ICC=.77).

Primary outcome measure, predictor variables and covariates

The primary outcome was weight, based on actual weight measured on a calibrated scale by study personnel at baseline and 3 months later. Participants were asked to remove their shoes, any jackets or outerwear, and belongings from their pockets before standing on the scale. There were two primary analyses. First, overall weight change and the difference in weight change were assessed between patients whose conversations included weight discussions and those that did not. In separate models, the effects of the following five motivational–interviewing techniques on weight change were examined within patients whose conversations included weight-related discussions: (1) motivational-interviewing Spirit (score >1), (2) Empathy (score >1), (3) Open questions (any open questions), (4) Reflections (any simple and/or complex reflections), and (5) behaviors consistent and inconsistent with motivational interviewing. For the last model, a score was created defined as motivational interviewing–inconsistent behaviors/(total motivational interviewing–consistent + inconsistent behaviors).

Patient-level covariates (14 included): gender, age, race, comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, arthritis, and hyperlipidemia), HS education, economic security (enough money to pay monthly bills), weight designation of overweight (BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2) or obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), actively trying to lose weight, motivated to lose weight, comfortable discussing weight, and confident about losing weight.

Physician-level covariates (9 included): gender, race (white, Asian or Pacific Islander versus African-American), years since medical school graduation, specialty (family versus internal medicine), self-efficacy to weight counseling, barriers to weight counseling, comfort discussing weight, insurance reimbursement concerns, and prior training in behavioral counseling.

Visit-level covariates (4 included): minutes spent addressing weight issues, explicit discussion of patient BMI (i.e., physician said “weight”), type of visit (preventive or chronic), and who initiated the weight discussion.

Analyses

The study was powered to detect differences between patients who had weight-related discussions and those who did not. For 80% power, the cluster adjusted sample size estimate was n=480 patients to detect a 1-kg difference in weight change over the 3-month period between patients who had weight-related discussions with their physician and those that did not. A discussion-participation level of 60% was assumed, an ICC of 0.01, SD of 3.3 kg, α= 0.05, 40 physicians with 12 patients per physician, and a loss to follow-up of 5%–10%. Because the literature on physician motivational-interviewing counseling on patient behavior was sparse, the estimated power did not include the motivational-interviewing technique predictors (i.e., motivational-interviewing Spirit) in the weight-related subset. However, power was estimated for a subgroup analysis examining the effect of a continuous communication style predictor on weight change in the subgroup who had weight-related discussions (subgroup n=320). It was calculated to have greater than 80% power to detect a change in weight of 0.50 kg for a 1 unit SD increase in the communication style measure. All analyses were performed using SAS software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Weight change was assessed between baseline and 3 months and the association of discussions of weight with weight loss (Model 1a and 1b). In a second set of models (Models 2a–2e), an examination was made of the association between use of each of the five motivational-interviewing techniques and weight loss within the subset of patients who had a weight discussion. Fit hierarchic models were fit that accounted for repeated measures of weight within the same patient as well as multiple patients clustered within the same physician.22 The physician clustering effect was used to account for extra variance due to patients having more similar weight change when they saw the same physician. SAS PROC MIXED was used to fit the hierarchic models to incorporate all patients with at least one time-point. This modeling framework yields unbiased estimates when missing data are unrelated to the unobserved variable.23

For Model 1a, the primary predictor was time (baseline/3-month follow-up). For Model 1b, the primary predictors were weight-related discussion (yes/no), time and time*weight-related interaction. For each of the models (Model 2a–2e), the primary predictors were a three-level predictor with one level that indicated no motivational-interviewing technique possible (no weight discussion) and the other two levels were the state of use of each motivational-interviewing technique (yes/no) for those who had weight discussions, time, and the interaction between the three-level motivational-interviewing technique variable and time. The three-level predictor was used so that all patients would be included in the analyses and estimated means would be adjusted appropriately as well as yielding robust estimates of SEs. The tests for differences in weight change between the use of the motivational-interviewing technique within the group who had weight discussions were contrasts set up within the time by three-level motivational interviewing–technique variables. The relationship between weight change and the proportion of motivational interviewing–inconsistent behaviors was tested. All models also included covariates that were defined a priori at the patient (e.g., age, gender, race), physician (e.g., gender, specialty, years since medical school) and visit level (e.g., type of visit) as described above.

Results

Sample characteristics

Physicians discussed weight with patients in 69% of encounters (Table 1). Mean patient weight at baseline was 91.7 kg (SD=21.1). Some physicians (38%) reported prior training in behavioral counseling (Table 2). African-American female physicians were more likely to refuse participation than their white, male counterparts (p=.005) and younger patients were more likely to refuse (p<.001). Three-month follow-up was completed on 426 patients (92%).

Table 1.

Patient and visit characteristics for total sample and patients in weight-related discussions

| Total (N=461) | Discussed weight (n=320) | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients | M (SD) or %(n) | M (SD) or %(n) |

| Baseline weight (kg) | 91.7 (21.1) | 93.9 (21.2) |

| Obese (BMI >= 30) | 54% (248) | 61% (194) |

| Race | ||

| White/Asian | 65% (300) | 61% (196) |

| African American | 35% (161) | 39% (124) |

| Male | 34% (158) | 34% (108) |

| Age | 59.8 (13.9) | 58.4 (13.3) |

| > High School Education (missing=1, 1)2 | 67% (306) | 68% (217) |

| Economic security: Pay bills easily (missing=13, 11) | 86% (387) | 88% (272) |

| Medical history | ||

| Diabetes | 31% (142) | 33% (104) |

| Hypertension (missing=1, 0) | 69% (316) | 68% (217) |

| Hyperlipidemia (missing=1, 1) | 56% (257) | 56% (180) |

| Arthritis | 47% (215) | 43% (136) |

| Very motivated to lose weight vs somewhat to not at all3 | 52% (241) | 58% (184) |

| Very confident can lose weight vs somewhat to not at all confident (missing 1, 0)4 | 36% (165) | 36% (115) |

| Very comfortable discussing weight with MD vs somewhat to not at all (missing 1, 0)5 | 76% (350) | 73% (234) |

| Tried to lose weight in past month | 47% (217) | 49% (158) |

| Visit factors | (N=461) | (n=320) |

| Total patient–medical personnel in-room time (minutes) | 25.4 (10.3) | 25.9 (10.2) |

| Total time spent discussing weight (minutes) (missing=15, 0) | 3.3 (3.3) | 4.2 (3.4) |

| Who initiated the weight discussion | ||

| Physician | 35% (163) | 36% (115) |

| Patient | 55% (254) | 64% (205) |

| Weight not discussed | 10% (44) | 0% (0) |

| Type of encounter (missing 3, 2) | ||

| Preventive | 36% (163) | 39% (123) |

| Chronic care | 64% (295) | 61% (195) |

| Explicit weight discussion (missing 15, 0) | 64% (286) | 76% (242) |

Patients were considered “counseled” when physicians used motivational-interviewing techniques when discussing weight

Missing data at baseline (total sample, counseled sample)

Motivation to lose weight/address weight (1=Not at all to 7 = Very much)

Self-efficacy to lose weight/address weight (1=Not at all confident to 5 = Very confident)

Comfort discussing weight (1=Not at all comfortable to 5 = Very comfortable)

Table 2.

Physician characteristics

| Physicians | (N=40) |

|---|---|

| Race | |

| White/Asian/Pacific Islander | 85 % (34) |

| African-American | 15% (6) |

| Male | 40% (16) |

| Years since med school graduation | 22.1 (8.0) |

| Specialty | |

| Family physician | 46% (19) |

| Internist | 54% (21) |

| Self-efficacy to address weight1 | 4.0 (0.7) |

| Comfort discussing weight2 | 4.4 (0.9) |

| Barriers to discussing weight with patients3 | 2.5 (0.8) |

| Prior training in behavioral counseling | 38% (15) |

| Concerns about reimbursement4 | 3.0 (1.6) |

Self-efficacy to lose weight/address weight (1=Not at all confident to 5 = Very confident)

Comfort discussing weight (1=Not at all comfortable to 5 = Very comfortable)

Barriers (1=Strongly disagree to 5= Strongly agree)

Concerns about reimbursement (1= Not very concerned to 5= Very concerned)

Quality of conversations

Physicians and patients spent a mean of 3.3 minutes in total per encounter discussing weight-related topics. Use of motivational-interviewing techniques during weight-related discussions was modest. Weight-related discussions contained the following proportions: motivational-interviewing–Spirit >1 (12%), Empathy >1 (6%), reflective listening (38%), and open questions (38%). Behaviors consistent and/or inconsistent with motivational interviewing were used in 92% of counseled encounters; the mean proportion of motivational interviewing–inconsistent behaviors in this group was 72%. All 40 physicians had weight-related discussions with some of their patients; 33 physicians had weight-related discussions with over 50% of their patients. For motivational-interviewing techniques use, 22 physicians had a score of >1 on motivational-interviewing Spirit with at least one of their patients, 35 made a reflection with at least one of their patients, 14 had an Empathy score of >1 with one of their patients, and 36 asked open questions of at least one patient. Encounters were 63.4 seconds (SE=36.0) shorter when physicians used motivational interviewing–consistent behaviors compared to motivational interviewing–inconsistent behaviors (p=.08). Encounters were 82.7 seconds (SE=25.0) longer when physicians made reflections (p=.001) and 61.9 seconds longer (SE=37.1) when they had a higher motivational interviewing–spirit score (p=.10).

Primary and secondary aims

In the hierarchic models, no significant physician clustering effect was found; therefore, the random physician effect was dropped from Models 1a and 1b effects.24 In these models, there was not enough heterogeneity in patient weight among physicians to estimate the variance. The correlation between baseline and 3-month weight was very high, estimated at 0.98.

After controlling for all patient-, physician-, and visit-level covariates, the estimated mean weight change between baseline and 3 months in this study was 0.0 kg (95% CI = −0.3, 0.4; p=0.95, Model 1a, Table 3). The estimated difference in change in weight over 3 months between patients in encounters with weight-related discussions and those without was 0.1 kg (95% CI = −0.7, 0.8; p=.84, Model 1b).

Table 3.

Estimated mean weight and differences in weight change over 3 months in kg from models including patient-, physician- and visit-level covariates The sample n=429 includes all patients except 32 with missing data), ICC=0.0;

| Model | Estimated Weight in kgs (M, SE) | Estimated difference in weight change [95% CI]b | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 3-month | |||

| Model 1aa | ||||

| Time | 91.7, 0.7 | 91.7,0.7 | 0.0[−0.3,0.4]b | 0.95 |

| Model 1b | ||||

| Discussed weight | 91.8,0.9 | 91.9,0.9 | ||

| No weight discussion | 91.2,1.6 | 91.2,1.6 | 0.1[−0.7,0.8] | 0.84 |

For Model 1a the difference in change is the estimated overall change in weight between baseline and 3 months; there are no group comparisons in this model; covariates include weight discussion covariate as well as patient-, physician- and visit-level covariates.

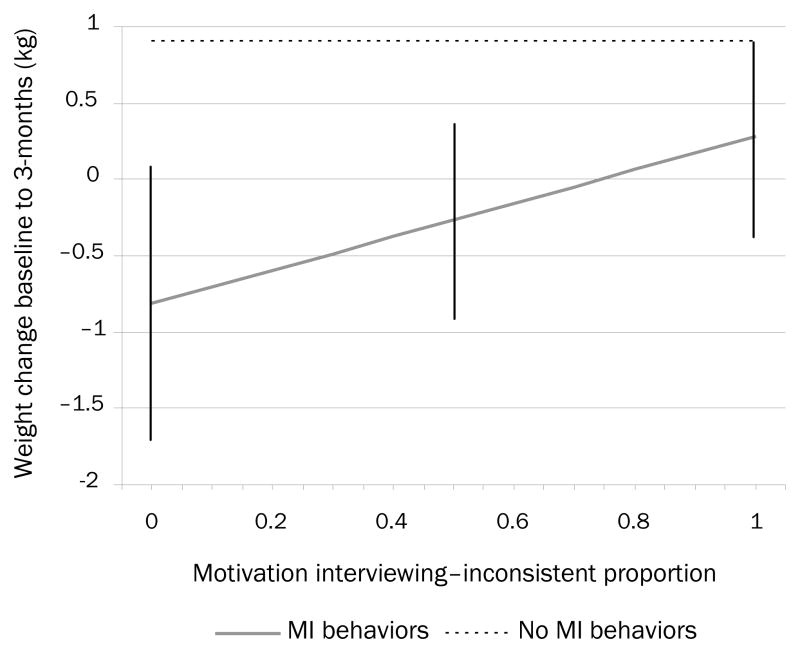

After controlling for all patient-, physician-, and visit-level covariates, patients experienced greater weight loss 3 months post-encounter when their physician used recommended motivational-interviewing counseling techniques when discussing weight (Table 4). From Model 2a, the estimated difference in weight change between patients whose physician had a high global “motivational interviewing–Spirit” score (>1) in their encounter (e.g., collaborated with patient) and those whose physician had a low score (=1) was 1.6 kg (95% CI = −2.9, −0.3; p=.02). Patients whose physician had a high motivational interviewing–spirit score in that encounter lost an estimated 1.4 kg (95% CI = −2.6, −0.2), whereas those patients whose physician had a low motivational interviewing–Spirit score gained an estimated 0.2 kg (95% CI = −0.2, 0.6). The estimated difference in weight change between patients whose physician used reflective listening in their encounter and those whose physician did not was 0.9 kg (95% CI = −1.8, −0.1; p=0.03, Model 2b). Patients whose physician used reflective listening in their encounter lost an estimated 0.5 kg (95% CI = −1.2, 0.1) whereas those whose physician did not use reflective listening gained an estimated 0.4 kg (95% CI = −0.1, 0.9). From Model 2e, the motivational interviewing–inconsistent proportion was fixed at 0 and 1 respectively, and the estimated difference in weight change between patients whose physician expressed only motivational interviewing–consistent behaviors and whose physician expressed only motivational interviewing–inconsistent behaviors was 1.1 kg (95% CI = −2.3, 0.1; p=0.07). Patients whose physician used only motivational interviewing–consistent behaviors in their encounter lost an estimated 0.8 kg (95% CI = −1.8, 0.1), whereas those whose physician used only motivational interviewing–inconsistent behaviors gained an estimated 0.3 kg (95% CI = −0.3, 0.3). The higher the motivational interviewing–inconsistent proportion, the less weight loss occurred (Table 4, Figure 2).

Table 4.

Estimated mean weight and differences in weight change over 3 months in kg from models including patient-, physician- and visit-level covariates. The sample n=429 includes all patients except 32 with missing data, ICC=0.0.

| Model | Estimated Weight in kgs (M, SE) | Estimated difference in weight change [95% CI]a | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 3-month | |||

| Model 2a | ||||

| Motivational-interviewing Spirit >1 | 95.4, 2.7 | 94.0, 2.7 | ||

| Motivational-interviewing Spirit = 1 | 91.4, 1.0 | 91.6, 1.0 | −1.6[−2.9,−0.3] | 0.02 |

| Model 2b | ||||

| Reflections | 93.2, 1.5 | 92.7, 1.5 | ||

| No reflections | 91.0, 1.2 | 91.4, 1.2 | −0.9[−1.8,−0.1] | 0.03 |

| Model 2c | ||||

| Open questions | 92.9, 1.5 | 92.9, 1.5 | ||

| No open questions | 91.2, 1.2 | 91.1, 1.2 | 0.1[−0.8,0.9] | 0.86 |

| Model 2d | ||||

| Empathy >1 | 101.4, 3.8 | 100.5, 3.8 | ||

| Empathy = 1 | 91.2, 1.0 | 91.1, 1.0 | −1.0[−2.8, 0.8] | 0.26 |

| Model 2e | ||||

| Motivational-interviewing behaviors | ||||

| Motivational interviewing–consistent onlyb | 91.8, 2.3 | 91.0, 2.3 | ||

| Motivational interviewing–inconsistent only | 91.4, 1.3 | 91.7, 1.3 | −1.1[−2.3,0.1] | 0.07 |

| No motivational-interviewing behaviors | 88.5, 3.4 | 89.4, 3.4 | 0.9[−0.6,2.5] | 0.25 |

Difference in change in weight between baseline and 3 months between the groups (i.e., the motivational interviewing–Spirit group loses weight over 3 months and the no motivational interviewing–Spirit groups gains weight); the difference in weight changes is 1.6 kg (estimate from contrast set up in the model of the motivational interviewing by time interaction term).

For Model 2e, the motivational interviewing–inconsistent proportion was fixed at 0 and 1, respectively, to get estimates for the group with motivational interviewing–consistent behaviors only and the group with motivational interviewing–inconsistent behaviors only.

Figure 2.

Estimated weight change from baseline to 3 months for patients with encounters with (1) no motivational-interviewing behaviors (consistent or inconsistent) and (2) by motivational interviewing–inconsistent proportion for patients with encounters with both motivational- interviewing behaviors (consistent and inconsistent). Vertical bars are 95% CIs on estimates of weight change for specific motivational interviewing–inconsistent proportions (0, 0.5 and 1 specifically).

Discussion

There are three important findings from this study. First, physicians are discussing weight with overweight and obese patients. Second, their weight-related discussions may not have been particularly effective given low use of motivational-interviewing techniques. Third, use of motivational-interviewing techniques during weight-related discussions was associated with patient weight loss. The proportion of encounters in which physicians discussed weight with patients is higher than that found in other studies.7, 11 This might be due to the attention obesity has received lately both in the media and in professional settings. Discussing weight did not affect patient weight loss, however. This might be because these discussions were not very effective. Physicians had low use of motivational-interviewing techniques, which was not surprising as less than half of physicians reported any training in behavioral counseling. Furthermore, physicians did not know the study was about weight-loss counseling or use of motivational-interviewing techniques.

Although discussing weight made no difference, it was hypothesized that use of motivational-interviewing techniques would be related to patient weight loss and found that indeed, when physicians used motivational-interviewing techniques, patients were more likely to lose weight in the next 3 months. A weight loss of 1.4 kg over 3 months can be considered a clinically relevant outcome.25 One possible explanation for these findings is that more-motivated patients engender more motivational interviewing–adherent counseling from physicians. However, patient-, physician-, and visit-level covariates that would explain individual differences and their relationship to weight were controlled. Because this study controlled for a priori confounders, the findings are relatively robust. These findings, however, should be confirmed in an RCT.

To our knowledge, only one other study has examined how physicians address weight.11 Tai-Seale’s study recorded 352 encounters, but coded only the presence of weight-related discussions, not the quality of the counseling or the effect of the counseling on patient weight loss. This study is the first to examine longitudinally the effects of weight-loss counseling on patient weight after the visit.

This study has some strengths and weaknesses. First, both patients and physicians were blinded to knowing the study was about weight. They were not primed to talk about weight; therefore, the results are more robust. Second, this very large data set of patient–physician encounters (N=461) was adequately powered to detect differences even based on a low level of use of motivational-interviewing techniques. Weaknesses include a high level of patient refusal, not assessing medication use, potential problems with generalizability due to lack of younger, lower-income patients, and an observational study design. As can be stated for any observational study with only two time points, regression to the mean can be a significant issue. Regression to the mean occurs when two variables are imperfectly correlated.14 In this study, the correlation between baseline and 3-month weight was very high, estimated at 0.98. Based on this high correlation and some diagnostic plots (results not shown) that can be used to evaluate the magnitude of regression to the mean,27 it likely is not regression to the mean as a significant issue in this study. Although the study was observational, approximately equal numbers of obese and overweight patients per physician were enrolled. Further, a large number of a priori designated relevant visit, physician and patient covariates, including for example patient motivation were controlled.

Results of the current study indicate that physicians may have the power with their words to help patients change. When physicians discuss weight in a way that is collaborative, supports patient autonomy, and allows the patient to be the driver of change, the patient may be more likely to change. Given the importance of obesity, the next step would be to evaluate whether physician motivational interviewing–consistent behaviors leads to longer-term weight changes, and whether using a randomized controlled design, physicians can be trained to provide more motivational interviewing–consistent behaviors and whether this leads to weight loss.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Xiaomei Gao, Katherine Stein, Elena Adamo, Cara Mariani, Dr. Mary Beth Cox, Dr. Christy Boling, and Dr. Theresa Moyers for their work on this project. We also would like to thank the gracious physicians who agreed to be formally acknowledged (Martha Adams, MD, Catherina Bostelman, MD, Joyce Copeland, MD, Lawrence Greenblatt, MD, Ronald Halbrooks, MD, Elaine Hart-Brothers, Jennifer Jo, MD, Thomas Koinis, MD, Evangeline Lausier, MD, Anne Phelps, MD, Barbara Sheline, MD, Allen Smith, MD, Tamra Stall, MD, Gloria Trujillo, MD, Kathleen Waite, MD, Daniella Zipkin, MD) and patients who agreed to have the physician encounters audio-recorded.

This work was supported by grants R01CA114392, R01DK64986, and R01DK075439.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.CDC. U.S. Obesity Trends 1985–2007. Overweight and Obesity. 2007 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/obesity/trend/maps/

- 2.Galuska DA, Will JC, Serdula MK, Ford ES. Are health care professionals advising obese patients to lose weight? JAMA. 1999;282(16):1576–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodondi N, Humair J-P, Ghali WA, Ruffieux C, Stoianov R, Seematter-Bagnoud L, et al. Counseling overweight and obese patients in primary care: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2006;13(2):222–8. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000209819.13196.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pollak KI, Ostbye T, Alexander SC, Gradison M, Bastian LA, Brouwer RJN, et al. Empathy goes a long way in weight loss discussions. J Fam Pract. 2007;56(12):1031–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loureiro ML, Nayga RM., Jr Obesity, weight loss, and physician’s advice. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(10):2458–68. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nawaz H, Adams ML, Katz DL. Physician patient interactions regarding diet, exercise, and smoking. Prev Med. 2000;31(6):652–7. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sciamanna CN, Tate DF, Lang W, Wing RR. Who reports receiving advice to lose weight? Results from a multistate survey. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(15):2334–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.15.2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans E. Why should obesity be managed? The obese individual’s perspective. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23(Suppl 4):S3–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800912. discussion S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehrotra C, Naimi TS, Serdula M, Bolen J, Pearson K. Arthritis, body mass index, and professional advice to lose weight: implications for clinical medicine and public health. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(1):16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phelan S, Nallari M, Darroch FE, Wing RR. What do physicians recommend to their overweight and obese patients? J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22(2):115–22. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.02.080081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tai-Seale T, Tai-Seale M, Zhang W. Weight counseling for elderly patients in primary care: how often and how much time. J Health Hum Serv Adm. 2008;30(4):420–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foster GD, Wadden TA, Makris AP, Davidson D, Sanderson RS, Allison DB, Kessler A. Primary care physicians’ attitudes about obesity and its treatment. Obes Res. 2003;11(10):1168–77. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruelaz AR, Diefenbach P, Simon B, Lanto A, Arterburn D, Shekelle PG. Perceived Barriers to Weight Management in Primary Care: Perspectives of Patients and Providers. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(4):518–522. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0125-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, 2009. AHRQ Publication No. 09-IP006] 2009 Available from: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/pocketgd.htm.

- 15.Rubak S, Sandbaek A, Lauritzen T, Christensen B. Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(513):305–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Webber KH, Tate DF, Quintilliani LM. Motivational interviewing in Internet Groups: a pilot study for weight loss. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(6):1029–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knight KM, McGowan L, Dickens C, Bundy C. A systematic review of motivational interviewing in physical health care settings. Br J Health Psychol. 2006;11(Pt 2):319–32. doi: 10.1348/135910705X52516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moyers TB, Martin T, Manuel JK, Hendrickson SM, Miller WR. Assessing competence in the use of motivational interviewing. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;28(1):19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thyrian JR, Freyer-Adam J, Hannover W, Roske K, Mentzel F, Kufeld C, et al. Adherence to the principles of Motivational Interviewing, clients’ characteristics and behavior outcome in a smoking cessation and relapse prevention trial in women postpartum. Addict Behav. 2007;32(10):2297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pierson HM, Hayes SC, Gifford EV, Roget N, Padilla M, Bissett R, et al. An examination of the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity code. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;32(1):11–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86(2):420–8. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verbeke G, Molenberghs G. Linear Mixed Models for Longitudinal Data. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. New York: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown H, Prescott R. Statistics in practice; Variation: Statistics in practice. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2006. Applied mixed models in medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dansinger ML, Gleason JA, Griffith JL, Selker HP, Schaefer EJ. Comparison of the Atkins, Ornish, Weight Watchers, and Zone diets for weight loss and heart disease risk reduction: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2005;293(1):43–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ward SH, Gray AM, Paranjape A. African Americans’ perceptions of physician attempts to address obesity in the primary care setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(5):579–84. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0922-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campbell DT, Kenny DA. A primer of regression artifacts. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]