Abstract

Tgif1 (TG-interacting factor) represses gene expression by interaction with general corepressors, and can be recruited to target genes by transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) activated Smads, or by the retinoid X receptor (RXR). Here we show that Tgif1 interacts with the LXRα nuclear receptor and can repress transcription from a synthetic reporter activated by LXRα. In cultured cells reducing endogenous Tgif1 levels resulted in increased expression of LXRα target genes. To test the in vivo role of Tgif1, we analyzed LXRα dependent gene expression in mice lacking Tgif1. In the livers of Tgif1 null mice, we observed significant derepression of the apolipoprotein genes, Apoa4 and Apoc2, suggesting that Tgif1 is an important in vivo regulator of apolipoprotein gene expression. In contrast, we observed relatively minimal effects on expression of other LXR target genes. This work suggests that Tgif1 can regulate nuclear receptor complexes, in addition to those containing retinoic acid receptors, but also indicates that there is some specificity to which NR target genes are repressed by Tgif1.

Keywords: Tgif, LXR, Apolipoprotein, Transcription, Repressor

The nuclear receptor (NR) family of transcription factors is a large family of transcriptional regulators, which control many complex gene expression programs in metazoan organisms [Mangelsdorf et al., 1995]. Nuclear receptors interact with both transcriptional corepressors and coactivators, and the balance between these antagonistic interactions is regulated in large part by the binding of specific ligands to the nuclear receptors [Shibata et al., 1997; Xu et al., 1999]. The liver X receptors (LXRs) are members of the NR family of transcription factors, which respond to oxidized cholesterol [Kalaany and Mangelsdorf, 2006], and play critical roles in regulating lipid metabolism and controlling cholesterol homeostasis. There are two LXRs: LXRα (NR1H3), which is highly expressed in liver, and is found at significant levels in a number of other tissues, including intestine, macrophages, adipocytes and kidney; and LXRβ (NR1H2), which is ubiquitously expressed. LXRs are activated by binding of physiological levels of oxysterols, which are cholesterol metabolites [Janowski et al., 1996; Lehmann et al., 1997]. LXRs function as heterodimers with the retinoid X receptor (RXR), and are predominantly pre-bound to their recognition sites on DNA. In most cases, LXR-RXR dimers bind to a direct repeat element, separated by four base pairs (DR4) [Chawla et al., 2001; Willy and Mangelsdorf, 1997]. As with other NR dimers, the spacing and orientation of the repeated half sites plays a major role in determining which genes are regulated by which NR complex [Khorasanizadeh and Rastinejad, 2001].

A major role of LXRs is to regulate the dietary uptake and subsequent metabolism of cholesterol [Handschin and Meyer, 2005; Kalaany et al., 2005; Kalaany and Mangelsdorf, 2006; Zelcer and Tontonoz, 2006]. LXRα null mice have enlarged livers, with the accumulation of excess cholesteryl esters, clearly pointing to a role for LXRα in cholesterol metabolism [Peet et al., 1998]. Interestingly, loss of LXRβ has no phenotype in the liver, suggesting that LXRα is the major player in this tissue [Alberti et al., 2001]. LXRs increase cholesterol breakdown in mice, by activating expression of the Cyp7a1 gene, which encodes the rate limiting enzyme in the conversion of cholesterol to bile acids [Lehmann et al., 1997]. A second way in which LXR activity regulates serum cholesterol levels is by increasing expression of a number of cholesterol efflux transporters. In the intestine, increased expression of ABCG5 and ABCG8 (ATP binding cassette transporters), in response to LXR activation, results in decreased absorption of dietary cholesterol and lower serum cholesterol levels [Berge et al., 2000]. Additionally, these two cholesterol efflux transporters are critical for the secretion of cholesterol to bile, in the liver [Yu et al., 2002]. The ABCA1 transporter is also an LXR target, and promotes cholesterol efflux from macrophages to the liver, via lipid-poor lipoproteins, such as ApoA-1 [Costet et al., 2000]. The lowering of cholesterol levels by LXR activation makes LXR agonists attractive candidates for cholesterol lowering drugs. However, activation of LXR also increases lipogenesis in the liver, resulting in increased triglyceride levels in the liver, and transient increases in plasma triglyceride levels [Joseph et al., 2002; Schultz et al., 2000]. In part this is due to LXR-mediated activation of expression of Srebp1c (sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 1), which is a key regulator of lipogenesis within the liver [Horton et al., 2002; Repa et al., 2000]. Additionally, expression of other enzymes involved in fatty acid production, such as fatty acid synthase, is also increased in response to LXR activation [Tontonoz and Mangelsdorf, 2003]. This clearly underscores the complex role that LXR plays in cholesterol and lipid metabolism.

Tgif1 is a homeodomain protein of the TALE family, which have a three amino acid loop extension (hence TALE) between helices one and two of the homeodomain [Bertolino et al., 1995]. Tgif1 binds directly to DNA or interacts with TGFβ-activated Smad proteins [Bertolino et al., 1995; Wotton et al., 1999a]. Once Tgif1 is recruited to a specific target gene, it is a context-independent transcriptional repressor [Wotton et al., 1999b]. Tgif1 was first identified as a protein which binds a retinoid response element (RXRE) from the rat cellular retinol binding protein II (CRBPII) gene [Bertolino et al., 1995]. More recently, we demonstrated that Tgif1 interacts with the retinoid X receptor (RXR), and recruits transcriptional corepressors [Bartholin et al., 2006]. Tgif1 interacts directly with the mSin3 corepressor via its carboxyl-terminal domain and recruits class I histone deacetylases (HDACs) [Sharma and Sun, 2001; Wotton et al., 2001; Wotton et al., 1999b]. Within its amino-terminal repression domain, Tgif1 contains a short amino acid motif (PLDLS) which interacts with the transcriptional corepressor CtBP (carboxyl-terminus binding protein) [Melhuish and Wotton, 2000]. A point mutation in Tgif1 from a patient with holoprosencephaly, alters the PLDLS motif and disrupts binding of CtBP to Tgif1, underscoring the importance of CtBP interaction for Tgif1 function [Gripp et al., 2000; Melhuish and Wotton, 2000]. Tgif1 targets general corepressors to specific regulatory elements either by direct DNA binding or by interaction with other DNA bound factors. The closely related Tgif2 functions similarly to Tgif1: it interacts directly with DNA, or with TGFβ activated Smads and represses gene expression. Although Tgif2 does not interact with CtBP, it can recruit the mSin3/HDAC complex, suggesting some level of functional redundancy [Melhuish et al., 2001; Melhuish and Wotton, 2006].

Apolipoproteins are lipid binding proteins which act as both lipid vehicles, and can affect the metabolism of bound lipids [Hegele, 2009]. In mice and humans, Apoa4 is part of a coordinately regulated, conserved gene cluster, with Apoa1, Apoc3 and Apoa5 [Zannis et al., 2001]. A second conserved cluster of four apolipoprotein genes, which includes Apoe and Apoc1/c2/c4, is also a target for regulation by LXR, primarily via a common enhancer element [Laffitte et al., 2001; Mak et al., 2002]. Expression of Apoa4 is relatively high in intestine, and low in liver. However, hepatic Apoa4 expression can be induced by cholesterol, in part via LXR [Liang et al., 2004; Williams et al., 1986]. Expression of human APOA4 in transgenic mice resulted in decreased formation of atherosclerotic plaques when induced either by diet, or in an Apoe null background [Duverger et al., 1996; Ostos et al., 2001]. Apoa4 regulates cholesterol metabolism, and promotes transport of cholesterol from extra-hepatic tissues to the liver, where it can be secreted to bile [Dvorin et al., 1986]. The antiatherogenic effect of Apoa4 may also be due to its ability to decrease cholesterol oxidation [Ferretti et al., 2002]. Oxidized LDL can increase atherogenesis through the formation of foam cells, and by affecting monocyte recruitment, and binding to endothelium [Frostegard et al., 1991; Parthasarathy et al., 1987].

Here we show that Tgif1 can repress transcription via LXRα nuclear receptor complexes, and that in cultured cells, Tgif1 regulates LXRα target genes. However, in mice Tgif1 may play a more limited role, effectively fine tuning the regulation of a specific subset of LXR-responsive genes. We show that two conserved apolipoprotein gene clusters are deregulated in the absence of Tgif1, and that Apoa4 and Apoc2 appear to be the most affected genes within these clusters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids and oligonucleotides

Tgif1 and RXRα expression and Tgif1 shRNA plasmids have been described previously [Bartholin et al., 2006]. Myc-tagged nuclear receptor plasmids were created by PCR in pCDNA3, with 6 Myc tags (a gift of Y. Ito). Original pCMX- LXRα and LXRβ plasmids were kindly provided by D.J. Mangelsdorf. The DR4 and DR3 reporter constructs were created in pGL2 basic into which a minimal TATA element from the Adenovirus MLP had been inserted. Two copies of a double stranded oligonlucleotide with the appropriate response element were cloned into the BglII site (see Table S1 for sequences).

Cell culture and siRNA knock-down

NMuLi and HepG2 cells were maintained in DMEM with 10% FBS, J774 and RAW cells in RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS and COS1 cells were grown in DMEM with 10% BGS. For knock-down, cells were plated in 12 well plates and transfected with Dharmacon SMARTpool oligonucleotides (see Table S1 for sequences), using DharmaFECT reagent 2, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was isolated 48 to 72 hours after transfection. The control pool (mouse siGENOME Non-targeting siRNA pool #1) was used for the non-targeting control.

Tgif1 gene disruption and mice

The Tgif1 null mutation has been described previously [Bartholin et al., 2006]. Tgif1 null mice in a C57BL/6J strain background were generated by crossing the F1 generation 5 times to C57BL/6J to generate the N6 generation (as described [Bartholin et al., 2008]). Male mice were maintained on a regular chow diet, or transferred to a mock western diet (Harlan TD 96121; 21% milk fat, 1.25% cholesterol) for 15 weeks, from the age of 6 weeks. Peripheral macrophages were isolated from the peritoneal cavity, four days after IP injection with 1.5ml of 4% Thioglycollate (DIFCO). Peritoneal macrophages were cultured overnight with or without ligand, as indicated. All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Virginia.

DNA and RNA analyses

DNA was purified from tail snip or ear punch and genotyped as described [Bartholin et al., 2006]. RNA was isolated and purified using Absolutely RNA kit (Stratagene). Tissues for RNA isolation were snap frozen on dry ice, stored at −80°C and then homogenized from frozen in RNA lysis buffer (Absolutely RNA kit), using a Polytron PT 2100. For qRT-PCR, cDNA was generated using Superscript III (Invitrogen), and analyzed in triplicate by real time PCR using a BioRad MyIQ cycler and Sensimix Plus SYBRgreen plus FITC mix (Quantace). Intron spanning primer pairs were selected using Primer3 (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/). See Supplemental Table 1 for primer sequences. Expression was normalized to Rpl4 using the delta Ct (Livak) method, and is shown as mean plus standard deviation of triplicates for cell lines, knock-down experiments, peripheral macrophage analyses and tissue expression panel. For analysis of gene expression tissues from three mice per genotype on each diet were analyzed and data is shown as mean +/- standard error of the mean.

Immunoprecipitation and western blotting

COS1 cells were transfected using LipofectAmine (Invitrogen). 36 h after transfection, cells were lysed by sonication in 100 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.8, 20% glycerol, 0.1% Tween 20, 0.5% NP40 with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Immunocomplexes were precipitated with Flag M2-agarose (Sigma). Following SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, proteins were electroblotted to Immobilon-P (Millipore) and incubated with antisera specific for Flag (Sigma) or Myc (9E10). Proteins were visualized with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit Ig (Pierce) and ECL (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Endogenous protein complexes were precipitated from two confluent 15cm dishes of COS1 cells using a mouse monoclonal LXRα specific antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and Tgif1 was detected using a rabbit polyclonal TGIF-specific antiserum [Wotton et al., 1999a].

Luciferase assays

HepG2 cells were transfected using Exgen 500 (MBI Fermentas) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were transfected with the appropriate luciferase reporter, the Renilla transfection control (phCMVRLuc; Promega), and the indicated expression constructs. After 48 hours firefly luciferase activity was assayed using firefly substrate (Biotium) and Renilla luciferase was assayed with 0.09μM coelenterazine (Biosynth), using a Berthold LB953 luminometer. For experiments with the siRNA vector, luciferase activity was assayed 60 hours after transfection. Nuclear receptor ligands (GW3965 and vitamin D3; Sigma) were added for the final 18 hours, as indicated.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed essentially as described [Wells and Farnham, 2002]. Briefly, NMuLi cells were treated with GW3965 for 16 hours, or left untreated, and were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 20 minutes at 37°C. Following chromatin isolation, DNA was sheared by sonication to between 200 and 1000bp in length. For ChIP from whole liver, freshly isolated tissue was gently dissociated into a conical tube and cross-linked for 20 minutes at 37°C. Immunoprecipitations were carried out using 2μl of a polyclonal Tgif1 antiserum [Wotton et al., 1999a], or 2μl of preimmune serum. The oligonucleotides used for PCR are listed in Supplemental Table 1. For input controls, 10% of the input chromatin was purified without IP. IP and input chromatin was analyzed by qPCR with a BioRad MyIQ cycler and Sensimix Plus SYBRgreen plus FITC mix (Quantace). Relative binding was determined by the ΔΔCt method, normalizing the specific immunoprecipitation (IP) signal to that in the pre-immune (PI) and the input sample (relative binding = 2((Ct[input]-Ct[IP])-(Ct[input]-Ct[PI]))).

RESULTS

Tgif1 represses an LXR-dependent transcriptional reporter

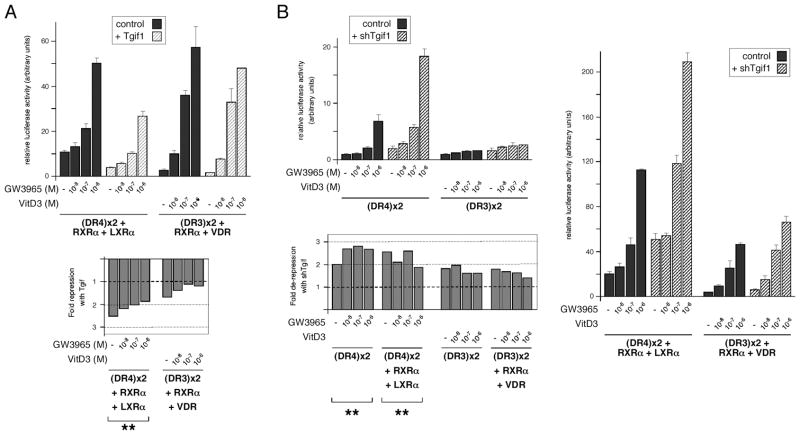

To test whether Tgif1 could repress nuclear receptor mediated transcriptional reporters, in addition to those activated by RAR/RXR, we created two copy DR3 and DR4 luciferase reporters. HepG2 cells, which we have previously used to assay effects of Tgif1, were transfected with the DR4 reporter, together with expression vectors encoding RXRα and LXRα, and increasing amounts of a Tgif1 plasmid. Cells were treated with a range of concentrations of LXR ligand (GW3965), and assayed for luciferase activity. As shown in Figure 1A, Tgif1 significantly repressed (p < 0.01) the activity of the DR4 reporter in the presence of coexpressed RXRα and LXRα. Tgif1 repressed by about 2.5-fold in the absence of ligand and this dropped to about 2-fold with increasing ligand. In similar experiments using the DR3 reporter and coexpressed RXRα and VDR Tgif1 failed to repress significantly (Figure 1A). We next tested the effects of reducing endogenous Tgif1 expression using a previously tested shRNA plasmid. Reporters were transfected alone and with the appropriate nuclear receptor combination, and treated with the same range of ligand concentrations. We observed a significant 2- to 3-fold derepression of the LXR-activated DR4 reporter by Tgif1 knock-down, with and without coexpressed RXRα and LXRα (Figure 1B). As with over-expression, Tgif1 knock-down had no significant effect on the DR3 reporter.

Fig. 1.

Tgif1 represses nuclear receptor transcriptional reporters. A: HepG2 cells were transfected with the indicated luciferase reporters and expression constructs, and luciferase activity was assayed after 40 hours. Ligand was added as indicated for 18 hours prior to analysis. Luciferase activity normalized to a transfection control is shown, with the fold-repression by coexpressed Tgif1 shown below. B: HepG2 cells were transfected with luciferase reporters and nuclear receptor expression constructs as indicated, together with a control pSUPER vector or one with an shRNA targeting TGIF1. Cells were assayed for luciferase activity 72 hours after transfection, with ligand treatment for the final 18 hours as indicated. Data are presented as normalized luciferase activity and as fold-derepression by shTGIF1. Ligand concentrations were 10−8, 10−7 and 10−6 M for GW3965 and vitamin D3. The significance level for repression (Tgif1 over-expression) and de-represssion (with shTGIF1) is shown: ** p < 0.01.

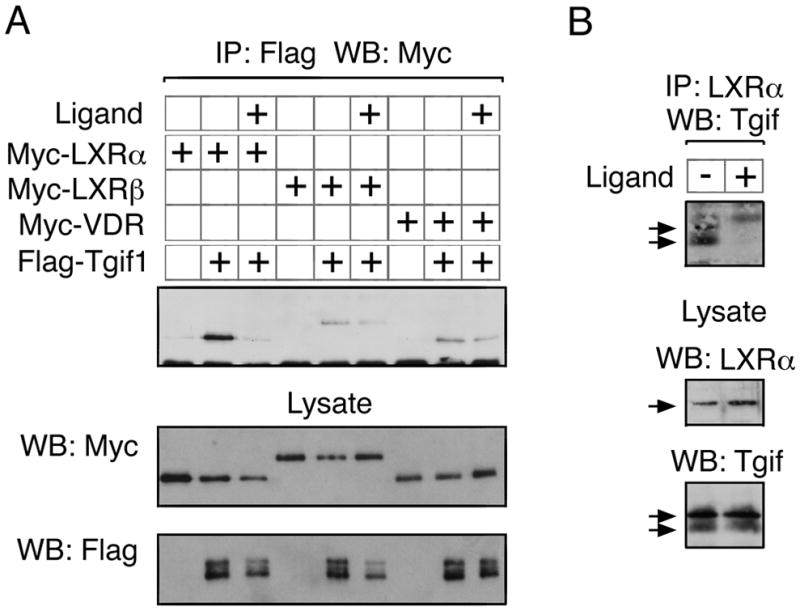

Based on the effects of Tgif1 on LXR-dependent luciferase reporters, we next tested whether Tgif1 and LXR interact in cells. COS1 cells were transfected with Myc-epitope tagged nuclear receptor constructs, together with Flag-tagged Tgif1 or a control vector, and either left untreated or incubated with ligand for 18 hours. Protein complexes were collected on anti-Flag agarose, and the precipitates analyzed for the presence of Myc-tagged nuclear receptors by western blot. As shown in Figure 2A, LXRα clearly coprecipitated with Tgif1 and this interaction was greatly reduced by treatment with ligand. Similar results were observed with both LXRβ and VDR, although in both cases, the interaction appeared to be less robust, and the effect of ligand was also less clear. To test whether we could detect the interaction of Tgif1 with LXRα, without the need for overexpression of either protein, we precipitated endogenous LXRα from COS1 cells, which had been left untreated or incubated overnight with GW3965. Precipitates were analyzed for the presence of Tgif1 using a polyclonal Tgif-specific antiserum. Tgif1 coprecipitated with LXRα, and this interaction was clearly decreased by the addition of ligand (Figure 2B). Taken together, these results suggest that Tgif1 can interact with LXRα to repress transcription, preferentially in the absence of ligand.

Fig. 2.

Tgif interaction with LXR. A: COS1 cells were transfected with the indicated expression constructs, and ligand (10−6 M GW3965 for LXRα and LXRβ; 10−6 M vitamin D3 for VDR) was added for 18 hours as indicated. 40 hours after transfection, cells were lysed, and protein complexes collected on anti-Flag agarose. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by western blot for the presence of Myc epitope-tagged nuclear receptors (upper panel). Expression of the transfected proteins was analyzed by direct western blot of the lysates (lower panels). B: Endogenous LXRα was immunoprecipitated from COS1 cells, which had been left untreated, or incubated with 10−6 M GW3965 for 18 hours. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by western blot for the presence of Tgif (upper), and expression in the lysates is shown below. Specific bands are indicated with arrows.

Tgif1 represses endogenous LXR target genes

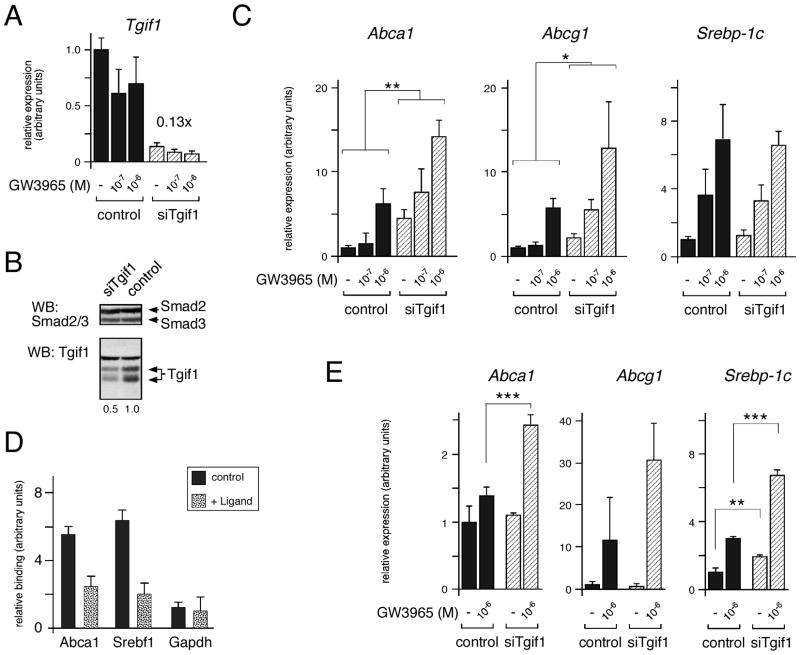

We next tested whether Tgif1 might play a role in regulating the expression of LXR-mediated gene expression at the endogenous level. To facilitate the analysis of endogenous gene expression in both mice and in cultured cells we first tested the NMuLi mouse liver cell line. NMuLi cells were transfected with Dharmacon Smartpool siRNA oligonucleotides targeting mouse Tgif1, or with a control pool of oligonucleotides. 48 hours after transfection with siRNAs, cells were either treated with ligand for a further 18 hours, or left untreated, prior to isolation of RNA. As shown in Figure 3A, we observed greater than 85% knock-down of Tgif1 mRNA. Western blot analysis with a Tgif-specific antiserum confirmed that there was a decrease in Tgif1 protein levels in cells transfected with the siTgif1 pool (Figure 3B). The knock-down NMuLi cells were next analyzed by real time quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) for expression of a panel of LXR-target genes. We tested expression of four different ABC transporter genes, which are LXR targets and are important modulators of cholesterol efflux [Kalaany and Mangelsdorf, 2006]. Additionally, we tested expression of the LXR-regulated isoform of the Srebf gene (encoding Srepb1c), which is a transcription factor that regulates a number of genes involved in lipid metabolism. As shown in Figure 3C, the expression of both Abca1 and Abcg1 was increased by knock-down of Tgif1, (p < 0.01, and p < 0.05, respectively). Expression of Abcg5 and Abcg8 was too low in these cells to reliably determine whether Tgif1 knock-down affected their expression (data not shown). In contrast to the increased expression of Abca1 and Abcg1, we did not observe a significant increase in Srebp-1c or total Srebf1 expression when we reduced expression of Tgif1 (Figure 3C and data not shown). Both the Abca1 and Srebf1 genes contain functional DR4 elements within their promoter regions, to which LXR has been shown to bind [Wagner et al., 2003]. To test whether Tgif1 was present at the LXR responsive region of the Abca1 promoter we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis from NMuLi cells treated with or without GW3965. Chromatin was precipitated with a Tgif-specific antiserum, or with the pre-immune serum, and precipitates were analyzed by q-PCR for the presence of the promoter region of the Abca1 gene, the Srebf1 promoter, or an unrelated gene (Gapdh). As shown in Figure 3D, the LXR responsive regions of the Abca1 and Srebf1 genes were enriched in the Tgif precipitates from control cells, and this enrichment clearly decreased on addition of ligand. Since Tgif1 appears to be recruited to both the Srebf1 and Abca1 promoters, but there was no apparent derepression of Srebp1c expression in NMuLi cells with Tgif1 knock-down, we tested the effects of knocking down Tgif1 in HepG2 cells. As shown in Figure 3E, we observed a significant increase in Abca1 and Srebp1c expression in the Tgif1 knock-down cells. Together, these data suggest that Tgif1 can regulate expression of at least some endogenous LXR target genes in cultured cells.

Fig. 3.

Tgif1 knock-down derepresses Abca1 expression. A: NMuLi cells were transfected with siRNAs targeting Tgif1, and cells were treated with GW3965 for 18 hours as indicated (10−7 and 10−6 M). Expression of endogenous Tgif1 mRNA was analyzed by qRT-PCR 72 hours after transfection with siRNAs. B: NMuLi cells transfected with siTgif1 or a control pool were analyzed by western blot for Tgif1 and Smad2/3 as a loading control. Specific bands are indicated, and the relative expression of Tgif1 is shown below. C: The NMuLi knock-down RNAs were analyzed by qRT-PCR for expression of Abca1, Abcg1 and Srebp-1c. Relative expression is shown in arbitrary units, as mean + s.d., as determined by the ΔCt method (significant changes are indicated: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01). D: Association of Tgif1 with the DR4 containing regions of the Abca1 and Srebf1 promoters was analyzed by chromatin immunoprecipitation. Tgif1 recruitment to the Gapdh promoter was analyzed as a control. Samples were from NMuLi cells treated with or without GW3965 (10−6 M), as indicated. Data is shown (in arbitrary units) as relative enrichment in the Tgif-specific precipitation, normalized to input chromatin and precipitation with pre-immune serum. E: HepG2 cells were transfected with siRNAs targeting Tgif1, and cells were treated with GW3965 for 18 hours as indicated. Expression of Abca1, Abcg1 and Srebp1c was analyzed by qRT-PCR 72 hours after transfection, and is shown in arbitrary units (significant changes are: ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

Increased expression of Tgif2 in Tgif1 null macrophages

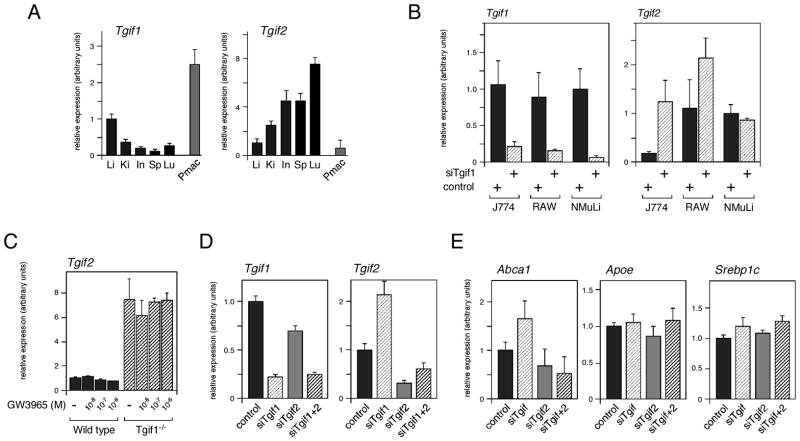

LXRα is highly expressed in a limited number of tissues, including liver, kidney, testis and macrophages. We were, therefore, interested to compare Tgif1 expression levels in these tissues. We isolated RNA from a panel of mouse tissues and tested expression of Tgif1, Tgif2 and of the genes encoding the Tgif1-interacting corepressors, Ctbp1 and Ctbp2, by qRT-PCR. Additionally, peritoneal macrophages were isolated and cultured for 24 hours in vitro prior to RNA isolation. As shown in Figure 4A, Tgif1 expression was highest in liver and peripheral macrophages, whereas, Tgif2 was more highly expressed in lung, intestine, spleen and kidney, than in either liver or macrophages. Ctbp1 and Ctbp2 were both expressed at relatively high levels in all tissues tested, but were lower in liver than in other tissues (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Tgif1 and Tgif2 expression levels. A: Tgif1 and Tgif2 expression in a panel of mouse tissues, and peripheral macrophages, was analyzed by qRT-PCR. Li: liver, Ki: kidney, In: intestine, Sp: spleen, Lu: lung, Pmac: peripheral macrophages. B: Expression of Tgif1 and Tgif2 was assayed by qRT-PCR in J774 and RAW macrophage cell lines with Tgif1 knock-down. NMuLi cells are shown for comparison. Fold change in expression relative to the control (set equal to 1) is shown above. C: Peripheral macrophages were isolated from wild type and Tgif1 null mice and incubated with GW3865 (10−8, 10−7, 10−6 M) as indicated. Tgif2 expression was analyzed by qRT-PCR. D: Both Tgif1 and Tgif2 were knocked down in RAW cells (as indicated), and expression was measured by qRT-PCR. E: Expression of Abca1 and Abcg1 was analyzed by qRT-PCR in RAW cells transfected with the indicated siRNAs.

Based on the high expression of Tgif1 in peripheral macrophages, we next tested the effects of Tgif1 knock-down in two mouse macrophage cell lines. However, we observed no significant changes in expression of a number of LXR target genes, or genes involved in lipid metabolism (data not shown). Similarly, comparison of LXR target gene expression between wild type and Tgif1 null peripheral macrophages revealed no significant changes (data not shown). Interestingly, knock-down of Tgif1 in both RAW cells and in J774 resulted in an up-regulation of Tgif2, suggesting that in macrophages Tgif2 expression may be inhibited by Tgif1 (Figure 4B). In contrast, this effect on Tgif2 was not seen in NMuLi cells. We next tested the expression of Tgif2 in peritoneal macrophages from either wild type or Tgif1 null mice. As with the cell lines, we observed up-regulation of the expression of Tgif2 in primary macrophages, and this was not affected by treatment with GW3965 (Figure 4C). Some increase in Tgif2 expression in the liver of Tgif1 null mice was also observed (see Table 1 and Table S2). To test whether reducing both Tgif1 and Tgif2 levels could affect expression of LXR target genes in macrophages, we knocked down both genes in RAW cells, and tested expression of LXR target genes. Despite, obtaining a dramatic decrease in both Tgif1 and Tgif2 we did not detect any significant changes in LXR target gene expression (Figure 4D, E and data not shown). These data show that in macrophages Tgif2 expression is up-regulated in response to decreased Tgif1 levels. Thus loss of Tgif1 function may in part be compensated for by increased expression of Tgif2, although in macrophages this does not appear to contribute to regulation of LXR target genes.

Table 1.

Gene expression analysis in liver.

| Chow1 | High fat | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gene | rel exp2 | Sig3 | rel exp | Sig3 | diet WT4 | diet Tgif−/− |

| Tgif2 | 2.89 | * | 1.68 | 0.87 | 0.51 | |

| Abca1 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.29 | 0.29 | ||

| Abcb11 | 0.97 | 0.55 | 3.19 | 1.80 | ||

| Abcb4 | 1.77 | * | 0.95 | 7.70 | 4.14 | |

| Abcg1 | 0.91 | 1.74 | 0.97 | 2.03 | ||

| Abcg5 | 1.58 | 1.06 | 22.79 | 15.29 | ||

| Abcg8 | 2.23 | * | 0.96 | 14.10 | 6.05 | |

| Acaca | 1.56 | ** | 1.69 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |

| Acacb | 1.13 | 2.53 | *** | 7.92 | 17.80 | |

| Angptl3 | 0.83 | 0.85 | 4.45 | 4.56 | ||

| Cd36 | 1.05 | 0.88 | 2.38 | 1.98 | ||

| Cyp7a1 | 0.77 | 0.37 | ** | 39.41 | 19.00 | |

| Dgat1 | 0.77 | ** | 0.67 | 0.71 | 0.61 | |

| Dgat2 | 1.02 | 1.10 | 0.78 | 0.84 | ||

| Fasn | 1.07 | 1.49 | 0.81 | 1.13 | ||

| Lpl | 1.03 | 1.06 | 1.16 | 1.19 | ||

| Scarb1 | 0.70 | ** | 0.73 | 0.33 | 0.34 | |

| Scd1 | 1.26 | 1.28 | 3.79 | 3.86 | ||

| Hnf4a | 1.28 | ** | 0.62 | *** | 4.63 | 2.25 |

| Chrebp1 | 0.90 | 0.69 | 0.53 | 0.41 | ||

| Couptf2 | 0.98 | 0.80 | 2.21 | 1.80 | ||

| Foxo1 | 1.08 | 0.78 | * | 1.78 | 1.29 | |

| Lrh1 | 1.38 | 0.94 | 1.26 | 0.85 | ||

| LXRa | 0.94 | 0.78 | 3.64 | 3.03 | ||

| Pgc1a | 1.96 | * | 0.94 | 1.76 | 0.84 | |

| Shp | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.28 | 0.28 | ||

| Srebf15 | 0.66 | 1.29 | 2.53 | 4.92 | ||

| Srebp1c | 0.80 | 1.00 | 4.24 | 5.31 | ||

Notes

Mice were maintained on a normal chow diet or fed a high fat, high cholesterol diet for 15 weeks.

Expression is shown as Tgif null relative to wild type, for each diet.

Significance was analyzed by student’s T test.

p < 0.1;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01.

Expression is compared between diets for each genotype.

Expression of Srebf1 (including both Srebf1 isoforms), and the Srebp1c isoform alone were analyzed.

Analysis of the role of Tgif1 in liver

To further analyze the in vivo effects of Tgif1 on LXR mediated gene expression and lipid homeostasis, we took two approaches. First we analyzed serum and tissue lipid levels in wild type and Tgif1 null mice, and second, we tested expression of a panel of LXR target genes, and other genes involved in lipid metabolism, primarily in the livers of these animals. Wild type and Tgif1 null mice, on a relatively pure C57BL6/J strain background were used for this analysis, since mice of this strain are known to be sensitive to diet induced atherosclerosis. Wild type and mutant mice were maintained on a normal chow diet, or at 6 weeks of age were transferred to a mock western diet, with high fat and high cholesterol (21% milk fat, 1.25% cholesterol), and analyzed after another 15 weeks. With the number of animals tested, we did not observe any significant genotype dependent differences in weight gain over this period. Serum and liver tissue from male mice on both diet regimens were analyzed for cholesterol and triglyceride levels. Comparison of serum and tissue lipid profiles between wild type and mutant mice did not reveal any dramatic effect of loss of Tgif1 on lipid homeostasis (data not shown).

To test whether loss of Tgif1 from the animal resulted in any significant changes in expression of LXR target genes, or genes involved in lipid metabolism, we analyzed a panel of genes by qRT-PCR from three mice of each genotype, on either diet. We analyzed expression first from liver, since Tgif1 expression was relatively high in liver, and the liver plays a major role in lipid metabolism. We tested expression of genes encoding ABC transporters, enzymes involved in cholesterol and triglyceride metabolism, apolipoproteins, as well as genes encoding a number of transcriptional regulators. As shown in Table 1 (also see Supplemental Table 2), expression of the genes encoding several metabolic enzymes was significantly altered in the Tgif1 null animals. For example, expression of Acaca, which encodes the liver isoform of a rate-limiting enzyme in fatty acid synthesis, increased in the absence of Tgif1. However, expression of Dgat1, which encodes an enzyme involved in triglyceride synthesis, was decreased in the Tgif1 null mice. Additionally, Cyp7a1 expression decreased in the Tgif1 null on the high fat diet. Cyp7a1 is a rate limiting enzyme, and major regulated step, in the synthesis of bile acids. Among the transcription factors analyzed, only expression of Hnf4α changed significantly. However, expression increased in the Tgif1 null on the regular chow diet, but decreased in the null when fed the mock western diet. We observed little change in expression of Abc transporter genes, many of which are regulated by LXRα in liver, although there was some increase in Abcb4 and Abcg8 (Table 1). We also tested the effects of a short term induction of LXR actrivity, rather than the 15 week high fat diet, as this may have induced additional changes to liver function, independent of direct LXR mediated effects. Mice were treated daily for three days with the LXR agonist, T0901317, and RNA was prepared from the liver 18 hours after the final treatment. We analyzed expression of a sub-set of the genes shown in Table 1, and observed significant increases only in expression of Acaca and Acacb, suggesting that the regulation of these two genes in liver may indeed be sensitive to both LXR and Tgif1 (Supplemental Table 3). Together with the analysis of lipid homeostasis, this gene expression data suggests that Tgif1 is not a major in vivo regulator of LXR-mediated gene expression in the liver.

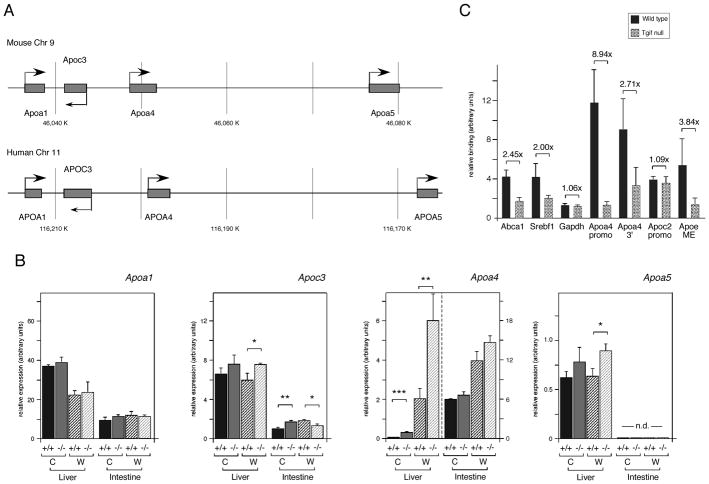

Increased hepatic Apoa4 expression

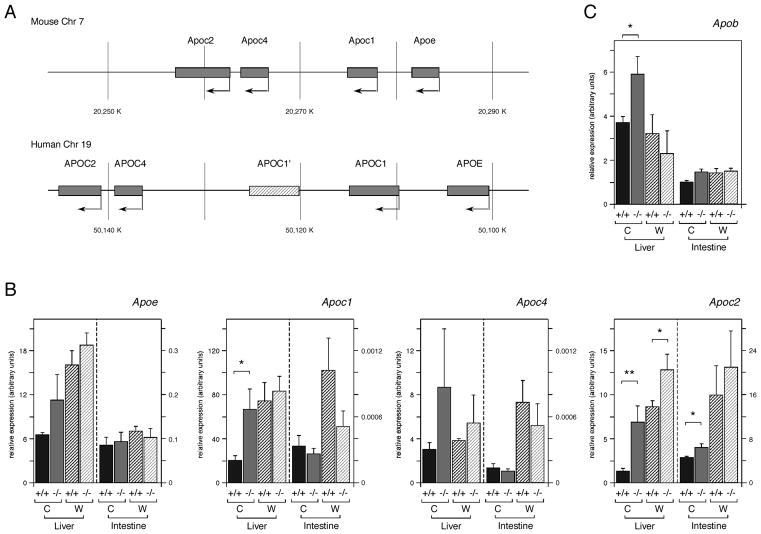

The genes for which we observed the most dramatic changes in expression in Tgif1 null livers encode apolipoproteins, such as Apoa4 and Apoc2. Apolipoproteins constitute the protein component of serum lipoproteins, which transport lipids, including cholesterol and triglycerides. Apoa4 is part of a conserved gene cluster in mice and humans (on chromosomes 9 and 11 respectively), together with Apoa1, Apoc3 and Apoa5 (see Figure 6A). Apoa4 is expressed at a relatively low level in liver, but can be induced by LXR ligands [Liang et al., 2004; Williams et al., 1986]. A second conserved apolipoprotein gene cluster is present on mouse chromosome 7 (and human 19), which contains Apoe/c1/c4/c2 (Figure 5A). Expression of the genes in this cluster is coordinately regulated and is responsive to LXR [Allan et al., 1997; Mak et al., 2002]. We first analyzed expression of the chromosome 7 Apoe/c1/c4/c2 apolipoprotein gene cluster. We observed some increase in hepatic expression of Apoe and Apoc1 in the Tgif1 null animals on the regular chow diet, and Apoc4 also increased, but was highly variable from animal to animal (Figure 5B; see also Table S3). Apoc2 expression in the liver increased significantly in the Tgif1 null, where it was increased by more than 5-fold on the chow diet and 1.5-fold on the mock western diet (Figure 5B, Table S4). Since genes of this cluster are also expressed in intestine, we examined expression in intestine from wild type and null mice. There was some increase in Apoc2 expression in the intestine of Tgif1 null animals. We also tested expression of Apob, which is not part of either conserved gene cluster, and observed a small increase in expression in the liver of Tgif1 null animals on the normal chow diet (Figure 5C). In macrophages, the Apoe/c1/c4/c2 gene cluster has been shown to be LXR-regulated via a common enhancer, which contains a DR4 element [Mak et al., 2002]. However, we observed no significant increase in expression of genes in this cluster in Tgif1 null peripheral macrophages, or in RAW cells with knock-down of Tgif1 (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Tgif1 represses Apoa4 expression in liver. A: The conserved Apoa4 containing gene clusters from mouse and human are shown schematically. B: Expression of the four genes of the Apoa4-containing gene cluster was analyzed by qRT-PCR, from Liver and intestine from 3 wild type and 3 Tgif1 null mice on a regular chow [C] or mock western [W] diet. Data is shown as the mean expression (+ s.e.m.), determined by the ΔCt method. Significant differences, as determined by the student’s T test, are indicated for comparison between genotypes on the same diet. The significance levels are: * <0.1, ** <0.05., *** <0.01. C: Tgif1 recruitment to LXR target genes in whole mouse liver was analyzed by ChIP. Liver from wild type and Tgif1 null mice was dissociated, chromatin cross-linked, immunoprecipitated with a Tgif anti-serum or the pre-immune and analyzed by q-PCR. Relative binding, normalized to input and pre-immune is shown. The DR4 containing regions of the Abca1, Srebf1 and Apoa4 promoters were analyzed, as well as a region from 3′ of the Apoa4 gene, which also contains a DR4 element. The Apoc2 promoter and the macrophage enhancer (ME) from the Apoe/c cluster were also tested for Tgif recruitment. The Gapdh promoter was tested as a negative control. The fold difference between wild type and null is shown above each.

Fig. 5.

Analysis of expression of the Apoe/c1/c4/c2 gene cluster in the absence of Tgif1. A: The Apoa1/c3/a4/a5 gene cluster on mouse chromosome 7 is shown schematically, with the conserved human gene cluster below. The APOC1′ gene in the human gene is a pseudogene generated by a duplication of part of the human cluster. B: Expression of the four genes of the Apoe/c1/c4/c2 gene cluster was analyzed by qRT-PCR. Liver and intestine RNAs from 3 mice per group (wild type and Tgif1 null, on a regular chow [C] or mock western [W] diet) were tested. Data is shown as the mean expression (+ s.e.m.), determined by the ΔCt method. C: Expression of Apob is shown as for B. Significant differences, as determined by the student’s T test, are indicated for comparison between genotypes on the same diet. The significance levels are: * <0.1, ** <0.05.

We next analyzed the chromosome 9 gene cluster in both liver and intestine. As shown in Figure 6B (see also Table S4), we observed a 4.9-fold increase in Apoa4 expression in Tgif1 null liver compared to the wild type. Wild type mice on the mock western diet had 33-fold greater Apoa4 expression than on the regular chow diet, and this expression increased by a further 3-fold in the absence of Tgif1. There was a small, but not statistically significant, increase in Apoa4 expression in the intestine of Tgif1 null mice on the mock western diet, as well as a small change in Apoc3 in both tissues and some increase in hepatic Apoa5 expression (Figure 6B and Table S4). To test whether Tgif1 was present at the regulatory regions of the Apoa4 gene, we performed ChIP analyses from whole mouse liver, using livers from either wild type or Tgif1 null mice. Following dissociation and cross-linking of the liver tissue, chromatin was precipitated with a Tgif-specific antiserum, or with pre-immune serum, and analyzed by qPCR. We first tested for enrichment of the Abca1 and Srebf1 promoter regions analyzed previously in NMuLi cells. Both Abca1 and Srebf1 were somewhat enriched compared to the Gapdh control in the anti-Tgif precipitates from wild type livers, and this was diminished in the Tgif1 null liver (Figure 6C). We next analyzed two regions from the Apoa4 gene, which have both been reported to respond to LXR [Liang et al., 2004]. The Apoa4 promoter region, which contains a DR4 element was highly enriched in the Tgif precipitates from the wild type liver, compared to those from the null. Additionally, we observed some enrichment of the region 3′ of the Apoa4 gene, which has also been suggested to bind LXR (Figure 6C). Analysis of the Apoc2 promoter region and the macrophage enhancer (ME), which contains a functional LXR response element, revealed that Tgif1 was enriched at the ME, but was not found at the Apoc2 promoter (Figure 6C). Thus, Tgif1 may be able to play a more general role in regulating expression of the Apoe/c1/c4/c2 gene cluster. Together, these data suggest that a primary effect of loss of Tgif1 is the up-regulation of apolipoprotein gene expression in the liver, which most dramatically affects Apoa4 and Apoc2.

DISCUSSION

Here we demonstrate that Tgif1 is an in vivo regulator of hepatic expression of at least two apolipoprotein genes. In the liver of Tgif1 null mice, we see significantly increased expression of Apoa4 and Apoc2, and Tgif1 is present at the Apoa4 promoter.

We have previously demonstrated that Tgif1 can repress retinoid regulated transcriptional reporters via an interaction with RXR [Bartholin et al., 2006]. Since RXR is a heterodimeric partner for a number of nuclear receptors, this prompted us to test whether Tgif1 could also regulate other nuclear receptor mediated transcriptional responses. We show that Tgif1 represses a transcriptional reporter which is activated by LXRα. At least in these tissue culture assays, Tgif1 appeared to preferentially repress responses that are dependent on LXRα, and we show that Tgif1 and LXRα interact. This repression of LXRα dependent responses may reflect a true physiological preference for LXRα, but it may also be in part due to the use of a liver cell line for these reporter assays. However, this clearly raises the possibility that Tgif1 may be a more general nuclear receptor corepressor. Whether this effect of Tgif1 depends on RXR, or is via a direct interaction between Tgif1 and LXR remains to be tested, but our previous work suggests that for RARα and PPARγ, RXR coexpression can increase interaction with Tgif1 [Bartholin et al., 2006].

Based on the apparent preferential repression of LXRα dependent reporters by Tgif1 we tested the in vivo effects of Tgif1 on nuclear receptor mediated gene expression. In cultured cells, we show that there is a modest effect of Tgif1 knock-down on expression of two known LXRα target genes. However, the key test of Tgif1 function was to analyze the effects of a Tgif1 null mutation in mice. Tgif1 is expressed in a number of tissues in which cholesterol signaling via LXRα is important, including liver and peripheral macrophages. In contrast, the related Tgif2 was much less well expressed in these two cell types. We observed a dramatic upregulation of Tgif2 expression in macrophages with reduced expression of Tgif1, and this was also apparent in Tgif1 null liver tissue. A similar increase in Tgif2 expression in the absence of Tgif1 is also seen in early embryogenesis [Powers et al., 2010]. This clearly points to a role for Tgif1 in regulating Tgif2 expression, and suggests that increased expression of Tgif2 may compensate for loss of Tgif1 function. Further analysis of gene expression in macrophage cell lines with Tgif1 knock-down, and in Tgif1 null peripheral macrophages did not reveal a significant role for Tgif1 in regulating LXR mediated gene expression in these cells, despite the relatively high Tgif1 expression levels. It is possible that up-regulation of Tgif2 compensates for loss of Tgif1, but since Tgif2 levels in macrophages start out quite low, it is unlikely that this is the whole explanation.

Our analysis of hepatic gene expression in wild type and Tgif1 null animals revealed a restricted pattern of gene expression changes. Most of the direct LXRα target genes tested were not significantly derepressed in the absence of Tgif1, and we did not observe dramatic changes in many genes involved in cholesterol metabolism. The notable exception, was the clear de-repression of specific apolipoprotein genes. Comparison of our in vitro data and the in vivo suggest an apparent contradiction. In vitro it appears that Tgif1 can regulate LXRα mediated gene expression, even when assayed at the endogenous level, whereas in a whole animal, loss of Tgif1 does not have a wide-spread effect on LXR-mediated gene expression. This suggests that in the intact mouse, these gene regulatory programs are well buffered by multiple regulatory inputs which maintain the robustness of the system. An additional possibility is that while Tgif1 may be part of a general nuclear receptor corepressor complex, and might therefore be recruited to numerous target genes, it may only play an important role at a subset of these genes, or under very specific circumstances. For example, Tgif1 may be a regulator of Apoa4 and Apoc2 due to the specific combination of other regulatory inputs. An obvious candidate for this would be repression by Tgif1 of genes, which are coordinately activated in response to TGFβ and LXRα signaling. Indeed, there is evidence for a role for TGFβ signaling in the regulation of the Apoa4 containing gene cluster [Kardassis et al., 2000], but we have as yet been unable to link TGFβ signals to the effects on Apoa4 seen with altered Tgif1 levels. An alternative possibility is that the genes which are particularly sensitive to altered Tgif1 levels, are actively repressed by Tgif1 in combination with other specific transcriptional repressors. Apoa4 expression in liver is relatively low compared to Apoa1 and Apoc3, whereas in intestine, Apoa4 levels are much higher. The combination of Tgif1 with other specific repressive mechanisms might serve to maintain low levels of hepatic Apoa4 expression, and thereby render Apoa4 more sensitive to loss of Tgif1. Unlike Apoa4, we are not aware of any evidence for regulation of Apoc2 by TGFβ, and expression in both liver and intestine is relatively high. Understanding how Tgif1 regulates Apoa4 and Apoc2 expression, and indeed the effects Tgif1 has on the entire gene clusters, will clearly be of future interest. Each of these genes is contained within a relatively compact gene cluster, and their regulation is likely to comprise a combination of specific and coordinate regulatory mechanisms, which may complicate any analysis of the specific role of Tgif1. However, our ChIP data suggest that Tgif1 is recruited to the Apoa4 promoter, which contains a functional DR4 element. Similarly, we observe enrichment of Tgif1 at the DR4 element containing macrophage enhancer within the Apoc2 gene cluster. This is consistent with a potential role for Tgif1-LXRα interactions, and suggests that regulation by Tgif1 is direct, rather than being entirely via changes in expression of other regulatory factors.

In summary, we have shown that in addition to retinoid responsive gene expression, Tgif1 can regulate LXRα mediated transcription, and we suggest that in vivo it will regulate specific subsets of genes, dependent on other regulatory inputs. We identify Apoa4 and Apoc2 as two LXRα target genes which are regulated by Tgif1. This work suggests that Tgif1 has the potential to regulate transcription via multiple NR complexes in addition to RAR/RXR, but also suggests that its effects are likely to be specific to relatively small subsets of NR target genes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Drs. D.J. Mangelsdorf. and Y. Ito for plasmids, and Drs. C.C. Hedrick and W. Shi for advice. This work was supported by a grant from the NIH: HD39926, to D.W., and by a grant form the American Heart Association (09GRNT2060150) to D.W.

References

- Alberti S, Schuster G, Parini P, Feltkamp D, Diczfalusy U, Rudling M, Angelin B, Bjorkhem I, Pettersson S, Gustafsson JA. Hepatic cholesterol metabolism and resistance to dietary cholesterol in LXRbeta-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:565–73. doi: 10.1172/JCI9794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan CM, Taylor S, Taylor JM. Two hepatic enhancers, HCR.1 and HCR.2, coordinate the liver expression of the entire human apolipoprotein E/C-I/C-IV/C-II gene cluster. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:29113–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.46.29113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholin L, Melhuish TA, Powers SE, Goddard-Leon S, Treilleux I, Sutherland AE, Wotton D. Maternal Tgif is required for vascularization of the embryonic placenta. Dev Biol. 2008;319:285–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholin L, Powers SE, Melhuish TA, Lasse S, Weinstein M, Wotton D. TGIF inhibits retinoid signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:990–1001. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.3.990-1001.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berge KE, Tian H, Graf GA, Yu L, Grishin NV, Schultz J, Kwiterovich P, Shan B, Barnes R, Hobbs HH. Accumulation of dietary cholesterol in sitosterolemia caused by mutations in adjacent ABC transporters. Science. 2000;290:1771–5. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolino E, Reimund B, Wildt-Perinic D, Clerc R. A novel homeobox protein which recognizes a TGT core and functionally interferes with a retinoid-responsive motif. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:31178–31188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.31178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla A, Repa JJ, Evans RM, Mangelsdorf DJ. Nuclear receptors and lipid physiology: opening the X-files. Science. 2001;294:1866–70. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5548.1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costet P, Luo Y, Wang N, Tall AR. Sterol-dependent transactivation of the ABC1 promoter by the liver X receptor/retinoid X receptor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:28240–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003337200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duverger N, Tremp G, Caillaud JM, Emmanuel F, Castro G, Fruchart JC, Steinmetz A, Denefle P. Protection against atherogenesis in mice mediated by human apolipoprotein A-IV. Science. 1996;273:966–8. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5277.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorin E, Gorder NL, Benson DM, Gotto AM., Jr Apolipoprotein A-IV. A determinant for binding and uptake of high density lipoproteins by rat hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:15714–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti G, Bacchetti T, Bicchiega V, Curatola G. Effect of human Apo AIV against lipid peroxidation of very low density lipoproteins. Chem Phys Lipids. 2002;114:45–54. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(01)00201-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frostegard J, Haegerstrand A, Gidlund M, Nilsson J. Biologically modified LDL increases the adhesive properties of endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis. 1991;90:119–26. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(91)90106-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gripp KW, Wotton D, Edwards MC, Roessler E, Ades L, Meinecke P, Richieri-Costa A, Zackai EH, Massague J, Muenke M, Elledge SJ. Mutations in TGIF cause holoprosencephaly and link NODAL signalling to human neural axis determination. Nat Genet. 2000;25:205–8. doi: 10.1038/76074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handschin C, Meyer UA. Regulatory network of lipid-sensing nuclear receptors: roles for CAR, PXR, LXR, and FXR. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;433:387–96. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegele RA. Plasma lipoproteins: genetic influences and clinical implications. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:109–21. doi: 10.1038/nrg2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton JD, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. SREBPs: activators of the complete program of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis in the liver. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1125–31. doi: 10.1172/JCI15593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janowski BA, Willy PJ, Devi TR, Falck JR, Mangelsdorf DJ. An oxysterol signalling pathway mediated by the nuclear receptor LXR alpha. Nature. 1996;383:728–31. doi: 10.1038/383728a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph SB, Laffitte BA, Patel PH, Watson MA, Matsukuma KE, Walczak R, Collins JL, Osborne TF, Tontonoz P. Direct and indirect mechanisms for regulation of fatty acid synthase gene expression by liver X receptors. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:11019–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111041200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaany NY, Gauthier KC, Zavacki AM, Mammen PP, Kitazume T, Peterson JA, Horton JD, Garry DJ, Bianco AC, Mangelsdorf DJ. LXRs regulate the balance between fat storage and oxidation. Cell Metab. 2005;1:231–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaany NY, Mangelsdorf DJ. LXRS and FXR: the yin and yang of cholesterol and fat metabolism. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:159–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.033104.152158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardassis D, Pardali K, Zannis VI. SMAD proteins transactivate the human ApoCIII promoter by interacting physically and functionally with hepatocyte nuclear factor 4. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:41405–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007896200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khorasanizadeh S, Rastinejad F. Nuclear-receptor interactions on DNA-response elements. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:384–90. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01800-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laffitte BA, Repa JJ, Joseph SB, Wilpitz DC, Kast HR, Mangelsdorf DJ, Tontonoz P. LXRs control lipid-inducible expression of the apolipoprotein E gene in macrophages and adipocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:507–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.021488798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann JM, Kliewer SA, Moore LB, Smith-Oliver TA, Oliver BB, Su JL, Sundseth SS, Winegar DA, Blanchard DE, Spencer TA, Willson TM. Activation of the nuclear receptor LXR by oxysterols defines a new hormone response pathway. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3137–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y, Jiang XC, Liu R, Liang G, Beyer TP, Gao H, Ryan TP, Dan Li S, Eacho PI, Cao G. Liver X receptors (LXRs) regulate apolipoprotein AIV-implications of the antiatherosclerotic effect of LXR agonists. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:2000–10. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak PA, Laffitte BA, Desrumaux C, Joseph SB, Curtiss LK, Mangelsdorf DJ, Tontonoz P, Edwards PA. Regulated expression of the apolipoprotein E/C-I/C-IV/C-II gene cluster in murine and human macrophages. A critical role for nuclear liver X receptors alpha and beta. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:31900–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202993200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangelsdorf DJ, Thummel C, Beato M, Herrlich P, Schutz G, Umesono K, Blumberg B, Kastner P, Mark M, Chambon P, et al. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell. 1995;83:835–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melhuish TA, Gallo CM, Wotton D. TGIF2 interacts with histone deacetylase 1 and represses transcription. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:32109–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103377200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melhuish TA, Wotton D. The interaction of C-terminal binding protein with the Smad corepressor TG-interacting factor is disrupted by a holoprosencephaly mutation in TGIF. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39762–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000416200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melhuish TA, Wotton D. The Tgif2 gene contains a retained intron within the coding sequence. BMC Mol Biol. 2006;7:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostos MA, Conconi M, Vergnes L, Baroukh N, Ribalta J, Girona J, Caillaud JM, Ochoa A, Zakin MM. Antioxidative and antiatherosclerotic effects of human apolipoprotein A-IV in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:1023–8. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.6.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathy S, Fong LG, Otero D, Steinberg D. Recognition of solubilized apoproteins from delipidated, oxidized low density lipoprotein (LDL) by the acetyl-LDL receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:537–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.2.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peet DJ, Turley SD, Ma W, Janowski BA, Lobaccaro JM, Hammer RE, Mangelsdorf DJ. Cholesterol and bile acid metabolism are impaired in mice lacking the nuclear oxysterol receptor LXR alpha. Cell. 1998;93:693–704. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81432-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers SE, Taniguchi K, Yen W, Melhuish TA, Shen J, Walsh CA, Sutherland AE, Wotton D. Tgif1 and Tgif2 regulate Nodal signaling and are required for gastrulation. Development. 2010;137:249–59. doi: 10.1242/dev.040782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repa JJ, Liang G, Ou J, Bashmakov Y, Lobaccaro JM, Shimomura I, Shan B, Brown MS, Goldstein JL, Mangelsdorf DJ. Regulation of mouse sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c gene (SREBP-1c) by oxysterol receptors, LXRalpha and LXRbeta. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2819–30. doi: 10.1101/gad.844900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz JR, Tu H, Luk A, Repa JJ, Medina JC, Li L, Schwendner S, Wang S, Thoolen M, Mangelsdorf DJ, Lustig KD, Shan B. Role of LXRs in control of lipogenesis. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2831–8. doi: 10.1101/gad.850400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M, Sun Z. 5′TG3′ interacting factor interacts with Sin3A and represses AR- mediated transcription. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:1918–28. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.11.0732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata H, Spencer TE, Onate SA, Jenster G, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O’Malley BW. Role of co-activators and co-repressors in the mechanism of steroid/thyroid receptor action. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1997;52:141–64. discussion 164–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tontonoz P, Mangelsdorf DJ. Liver X receptor signaling pathways in cardiovascular disease. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:985–93. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner BL, Valledor AF, Shao G, Daige CL, Bischoff ED, Petrowski M, Jepsen K, Baek SH, Heyman RA, Rosenfeld MG, Schulman IG, Glass CK. Promoter-specific roles for liver X receptor/corepressor complexes in the regulation of ABCA1 and SREBP1 gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5780–9. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5780-5789.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells J, Farnham PJ. Characterizing transcription factor binding sites using formaldehyde crosslinking and immunoprecipitation. Methods. 2002;26:48–56. doi: 10.1016/S1046-2023(02)00007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SC, Bruckheimer SM, Lusis AJ, LeBoeuf RC, Kinniburgh AJ. Mouse apolipoprotein A-IV gene: nucleotide sequence and induction by a high-lipid diet. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:3807–14. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.11.3807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willy PJ, Mangelsdorf DJ. Unique requirements for retinoid-dependent transcriptional activation by the orphan receptor LXR. Genes Dev. 1997;11:289–98. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wotton D, Knoepfler PS, Laherty CD, Eisenman RN, Massague J. The Smad Transcriptional Corepressor TGIF Recruits mSin3. Cell Growth Differ. 2001;12:457–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wotton D, Lo RS, Lee S, Massague J. A Smad transcriptional corepressor. Cell. 1999a;97:29–39. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80712-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wotton D, Lo RS, Swaby LA, Massague J. Multiple modes of repression by the smad transcriptional corepressor TGIF. J Biol Chem. 1999b;274:37105–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. Coactivator and corepressor complexes in nuclear receptor function. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:140–7. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(99)80021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Hammer RE, Li-Hawkins J, Von Bergmann K, Lutjohann D, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Disruption of Abcg5 and Abcg8 in mice reveals their crucial role in biliary cholesterol secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16237–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252582399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zannis VI, Kan HY, Kritis A, Zanni E, Kardassis D. Transcriptional regulation of the human apolipoprotein genes. Front Biosci. 2001;6:D456–504. doi: 10.2741/zannis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelcer N, Tontonoz P. Liver X receptors as integrators of metabolic and inflammatory signaling. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:607–14. doi: 10.1172/JCI27883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.