Summary

Keratinocytes contribute to melanocyte transformation by affecting their microenvironment, in part, through the secretion of paracrine factors. Here we report a loss of expression of nuclear receptor RXRα in epidermal keratinocytes during human melanoma progression. We show that absence of keratinocytic RXRα in combination with mutant Cdk4 generated cutaneous melanoma that metastasized to lymph nodes in a bigenic mouse model. Expression of several keratinocyte-derived mitogenic growth factors (Et-1, Hgf, Scf, α-MSH and Fgf2) were elevated in skin of bigenic mice, while Fas, E-cadherin and Pten, implicated in apoptosis, cellular invasion and melanomagenesis, respectively, were downregulated within the microdissected melanocytic tumors. We demonstrated that RXRα is recruited on the proximal promoter of both Et-1 and Hgf, possibly directly regulating their transcription in keratinocytes. These studies demonstrate the contribution of keratinocytic paracrine signaling during the cellular transformation and malignant conversion of melanocytes.

Significance

Malignant melanoma continues to evade modern curative efforts as a result of the complex and elusive nature of metastatic tumors. We demonstrated that RXRα expression is lost in epidermal keratinocytes during melanoma progression in humans. We have presented evidence for the association of keratinocytic nuclear receptor RXRα-mediated paracrine/juxtacrine signaling and the malignant transformation of melanocytic tumors. The present work highlights cooperative effects of aberrant keratinocytic signaling and activated Cdk4 in melanoma metastasis. This mouse model will allow greater understanding of the mechanisms responsible for transition towards a malignant phenotype. Manipulation of these receptor-mediated signaling pathways could hold therapeutic value when combating metastatic disease.

Keywords: RXRα, melanomagenesis, Cdk4, DMBA/TPA, paracrine, ChIP, LCM

Introduction

Cutaneous melanoma remains the deadliest form of skin cancer. Early detection can lead to effective treatment, but metastatic melanoma is typically non-responsive to current therapies and the median time of survival for patients is less than a year (Chin et al., 2006). Melanoma originates from pigment-producing cells in the skin called melanocytes that play a role in the epidermal response to UV radiation. In recent years, animal models that mimic genetic aberrations linked to melanomagenesis in humans have led toward a better understanding of underlying molecular mechanisms (Larue and Beermann, 2007).

Keratinocytes encompass and support the skin epidermal layer through a constant cycle of proliferation and differentiation. Epidermal proliferation is regulated through secretion of keratinocytic autocrine growth factors that influence receptor-mediated signals within the cell (Cook et al., 1991). The transfer of melanin from melanocytes to keratinocytes aids in the prevention of UV-induced genetic mutations and requires interaction between these two cell types (Scott, 2006). Communications between melanocytes and keratinocytes rely upon paracrine signaling that utilize soluble factors such as endothelin 1 (Et-1), fibroblast growth factor 2 (Fgf2), stem cell factor (Scf), alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH) and hepatocyte growth factor (Hgf); all of which have been shown to influence melanocyte mitogenesis, melanogenesis, and melanomagenesis (Cui et al., 2007; Halaban et al., 1988; Halaban et al., 1992; Hirobe, 2005; Imokawa et al., 1992; Kunisada et al., 1998). Aberrant paracrine signaling might result in the transformation of melanocytes to malignant cells (Mangahas et al., 2004; Otsuka et al., 1998).

The steroid hormone receptor protein retinoid-X-receptor α (RXRα), a member of the type II nuclear receptor (NR) superfamily, mediates biological effects in part through the regulation of gene transcription. RXRα is able to heterodimerize with some 15 NR family members and occupy corresponding response elements present in the promoters of target genes (Chambon, 1996; Mangelsdorf et al., 1995). RXR/NR heterodimerization modulates gene transcription (activation and/or repression), and acts on multiple developmental and differentiation processes (Altucci and Gronemeyer, 2001).

Three subtypes of the RXR protein are present in mammals, with RXRα being the predominant form expressed in murine epidermis (Fisher and Voorhees, 1996; Mangelsdorf et al., 1992). The RXRα-null mutation is embryonic lethal in mice, thereby preventing analysis of in vivo function of this protein in skin homeostasis and diseases (Sucov et al., 1994; Kastner et al., 1994). To circumvent this problem, Cre/loxP technology was utilized to selectively delete the RXRα protein in epidermal keratinocytes (Metzger et al., 2003). The RXRαep−/− mouse line displayed alopecia, epidermal keratinocytic hyperproliferation, aberrant terminal differentiation and an inflammatory reaction within the skin (Li et al., 2001). In a two-step chemical carcinogen model using topical applications of the tumor initiator 7, 12-dimethyl-benz[a]antracene (DMBA) and tumor promoter 12-0-tetradecanoylphorbol-13 acetate (TPA), RXRαep−/− mice developed a higher number of dermal melanocytic growths (nevi) compared to control mice. Only nevi from RXRα mutant mice progressed to human-melanoma-like tumors, suggesting that RXRα-mediated distinct non-cell autonomous molecular events appear to regulate suppression of nevi formation and melanoma progression (Indra et al., 2007). Of note, the tumors that formed in RXRαep−/− mice after DMBA/TPA treatment rarely invaded or metastasized to distal organs.

Cyclin-dependant kinase 4 (CDK4) protein, a product of the Ink4a locus, has been implicated in the development of cutaneous melanoma (Curtin et al., 2005; Kamb et al., 1994). An arginine to a cysteine point mutation in the CDK4 protein found in familial melanoma (Cdk4R24C/R24C) prevents the kinase activity of CDK4 from being inhibited by the G1/S phase regulator p16, leading to an increase in cell-cycle activity (Wolfel et al., 1995; Zuo et al., 1996). Cdk4R24C/R24C knock-in mice harboring this activated form of Cdk4 demonstrated increased susceptibility to melanoma formation after DMBA/TPA treatment (Rane et al., 1999; Sotillo et al., 2001). Mice containing the Cdk4R24C/R24C mutation in cooperation with deregulated receptor tyrosine kinase signaling, or activated Ras, has been shown to promote development of spontaneous and carcinogen-induced metastatic melanoma (Hacker et al., 2006; Tormo et al., 2006).

In this study, we evaluated expression of RXRα protein in normal human skin, tumor adjacent normal, benign nevi, in situ and malignant melanoma. We investigated the contributions of Cdk4R24C/R24C and keratinocytic RXRα to influence metastatic progression in a mouse model. Expression of several keratinocyte-derived growth factors, implicated in melanomagenesis, were upregulated in the skin of bigenic mice, and recruitment of RXRα was shown on the promoters of Et-1 and Hgf. We also confirmed a downregulation of factors (Fas, E-cadherin and Pten) implicated in apoptosis, invasion and survival within the melanocytic tumors.

Results

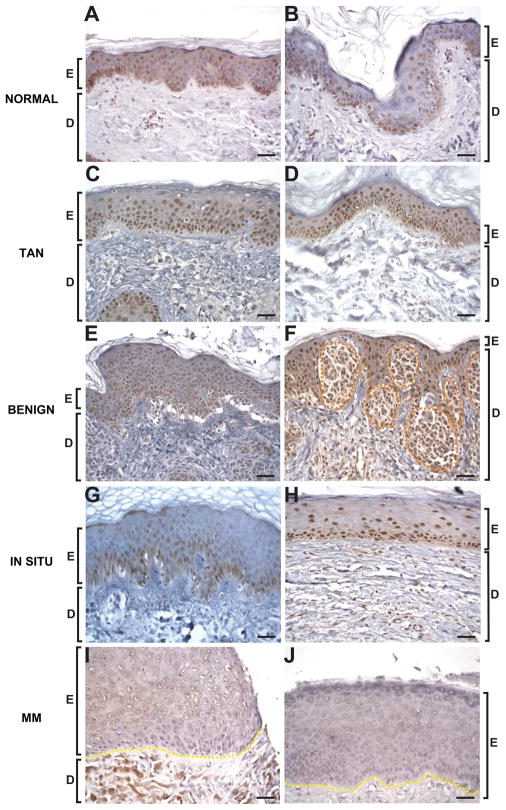

Downregulation of RXRα protein in epidermal keratinocytes during human melanoma progression

Our earlier studies demonstrated that loss of keratinocytic RXRα in a non-cell autonomous manner regulated melanocyte homeostasis during DMBA/TPA-induced melanomagenesis (Indra et al., 2007). It has been previously shown that a loss of nuclear RXRα protein in melanocytes correlates with melanoma progression in human patients (Chakravarti et al., 2007). We therefore investigated expression levels of RXRα protein in epidermal keratinocytes by immunohistochemistry (IHC) of normal human skin, tumor adjacent normal (TAN) epithelium, benign nevi, in situ melanoma and malignant melanoma samples from tissue microarray and de-identified human tissues. Normal and TAN epidermis showed strong nuclear RXRα expression in most, if not all, basal keratinocytes, as well as in the suprabasal layers (Figures 1A–D). The epidermis adjacent to benign nevi displayed a hyperplastic appearance that was also present in the in situ and malignant melanoma samples. Most keratinocytes, as well as nests of nevus cells, exhibited strong nuclear RXRα expression in the benign nevi (Figures 1E and 1F). A general trend of reduced expression (~50%) of RXRα protein was seen in suprabasal keratinocytes for in situ melanomas (Figures 1G and 1H, Table S1), and a marked absence of RXRα protein was seen in all layers of epidermis from malignant melanoma samples (Figures 1I and 1J, Table S1). A Fisher’s Exact test showed a significantly low probability (p < 0.001) that loss of keratinocytic RXRα expression would be seen only in these two tissues, suggesting an association with metastatic progression in humans.

Figure 1.

Reduced expression of keratinocytic RXRα during melanoma progression in human skin. Representative localization of RXRα protein within the epidermis of normal (A,B), tumor adjacent normal [TAN] (C,D), benign melanocytic nevi (E,F), in situ melanoma (G,H) and malignant melanoma [MM] sections (I, J). Brown staining represents RXRα expression (except for the dermal pigmentation present in malignant melanoma sections), counterstained with Harris hematoxylin. E, epidermis; D, dermis. Orange dashed line encompass nests of nevus cells, yellow dashed lines indicates epidermal-dermal junction. Scale bar = 33μm.

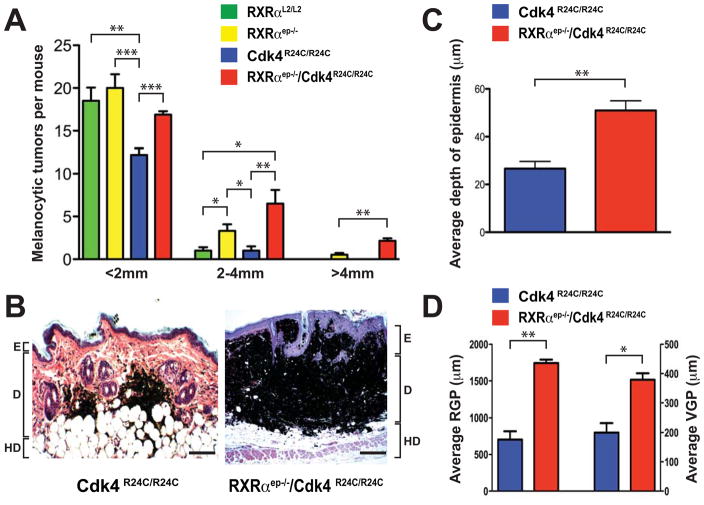

Loss of keratinocytic RXRα in cooperation with activated Cdk4 leads to larger melanocytic tumors in mice

Involvement of the p16/CDK4 pathway has been implicated during melanomagenesis in humans (Curtin et al., 2005; Kamb et al., 1994; Wolfel et al., 1995; Zuo et al., 1996). We hypothesized that the increased melanocyte proliferation reported in our previous study (Indra et al., 2007) could be due to deregulated cell cycle control. Additionally, the use of activated Cdk4, paired alongside a secondary genetic alteration of melanocytic signaling pathways, has been shown to promote formation of metastatic melanomas in mouse models (Hacker et al., 2006; Tormo et al., 2006). We therefore investigated the cooperative effects of activated Cdk4, in parallel with loss of keratinocytic RXRα, towards melanoma metastasis. To that end, we have bred the RXRαep−/− and Cdk4R24C/R24C mice to generate RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C bigenic mice and utilized the two step carcinogenesis (DMBA/TPA) protocol (DiGiovanni, 1992). RXRαL2/L2 (floxed RXRα mice containing LoxP sequences flanking exon 3) mice were used as wild-type controls, and those with single mutation (RXRαep−/− and Cdk4R24C/R24C) served as additional controls. Although all mice in each cohort developed melanocytic tumors (MT) within the timecourse of the study, a greater number of MTs grew to sizes larger than 2mm in diameter in both the RXRαep−/− and RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C mice compared to the RXRαL2/L2 or Cdk4R24C/R24C mice. Strikingly, the bigenic mice developed a significantly higher number of MTs larger than 4mm in size compared to the RXRαep−/− mice (Figure 2A, Figure S1). The appearance of melanocytic tumors arose within a similar timeframe of 7–8 weeks in all treatment groups, however decreased tumor latency was observed in mice lacking RXRα in epidermal keratinocytes (Figures S1B and S1C). All subsequent comparative studies were performed on RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C and Cdk4R24C/R24C mice to determine the contribution of keratinocytic RXRα signaling on melanomagenesis.

Figure 2.

Formation of larger melanomas in RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C bigenic mice. (A) Size distribution of melanocytic tumors in RXRαL2/L2, RXRαep−/−, Cdk4R24C/R24C and RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C mice after DMBA/TPA treatment. The number of tumors, less than 2 mm, 2–4mm and greater than 4 mm in diameter, were determined in the four groups of mice, as indicated. Values are expressed as mean +/− SEM. (B) Histological analyses of melanocytic tumors from Cdk4R24C/R24C and RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C mice. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained 5μm thick paraffin skin sections of biopsies taken after DMBA/TPA treatment. E, epidermis; D, dermis; HD, hypodermis. Scale bar = 62μm. (C, D) Increased epidermal thickness, and higher radial growth phase (RGP) and vertical growth phase (VGP) of melanocytic tumors in RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C mice. Statistical significance was calculated using unpaired Student’s t-test with GraphPad Prism software. Statistical relevance indicated as follows; * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001.

To further characterize the MTs formed in the dorsal skin of the Cdk4R24C/R24C and RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C mice, we performed hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of 5μm thick paraffin sections of melanocytic tumors from both genotypes (Figure 2B). A significant increase in epidermal thickness was observed in the skin from RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C skin compared to Cdk4R24C/R24C alone (Figure 2C). This phenotype is a hallmark of mice bearing an epidermal ablation of RXRα, as the basal layer keratinocytes maintain a hyperproliferative state (Li et al., 2001). Importantly, both the radial growth phase (RGP) and vertical growth phase (VGP) of the MTs in the dermis were significantly increased in the bigenic mice compared to the control mice (Figure 2D). Similar results were seen when comparing the bigenic mice to both RXRαL2/L2 and RXRαep−/− mice (data not shown). Altogether the above results suggest a synergistic effect of RXRα ablation and activated Cdk4 in the development of cutaneous melanoma.

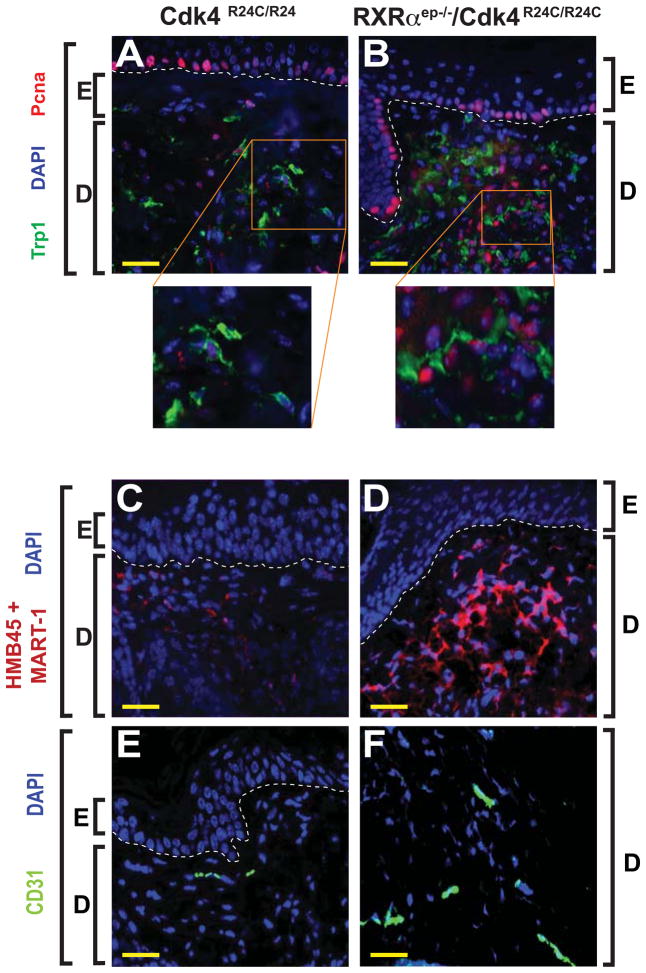

Immunohistochemical analyses of melanocytic tumors from RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C bigenic mice

We performed IHC using specific antibodies for markers of proliferation, malignant conversion, and vascularization, to further characterize the MTs from the bigenic mice. Immunohistochemical staining was performed on paraffin sections of tumors taken from Cdk4R24C/R24C and RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C mice after DMBA/TPA treatment. To investigate the mitogenicity of the MTs, we co-labeled with antibodies directed against the proliferation marker Pcna and the melanocyte-specific enzyme tyrosinase related protein 1 (Trp1) (Jimenez et al., 1988; Waseem and Lane, 1990). A significantly higher percentage (67% vs 21%) of Trp1+ cells were co-labeled with Pcna (Trp1+/Pcna+) in the RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C skin compared to the Cdk4R24C/R24C skin [(p < 0.01), Figures 3A and 3B]. In order to determine the malignant nature of the MTs from the bigenic mice, IHC was performed using an antibody cocktail directed against melanoma antigens MART-1 and HMB45 (Yamazaki et al., 2005). That combination showed increased staining in all of the MTs from the RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C compared to the Cdk4R24C/R24C mice, suggesting a larger population of malignant cells in these tumors (Figures 3C and 3D). Similarly, an increased immunoreactivity for the endothelial cell-specific marker CD31 was also detected in the bigenic mice (17% of DAPI positive cells) compared to Cdk4R24C/R24C mice (5% of DAPI stained cells), suggesting enhanced vascularization in the MTs from those mice (Wang et al., 2008) (Figures 3E and 3F). Altogether, these results (histopathological and IHC) confirm that the MTs from the bigenic mice have greater malignant tendencies compared to those from RXRαep−/− or Cdk4R24C/R24C mice.

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) characterization of melanocytic tumors in Cdk4R24C/R24C and RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C bigenic mice. (A, B) Enhanced melanocyte proliferation in melanocytic tumors from RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C mice as determined by co-labeling with anti-Trp1 [green] and anti-Pcna [red] antibodies. (C, D) IHC staining for malignant melanocytes using a cocktail of antibodies directed against melanoma antigens HMB45 and MART-1 [red]. (E, F) Increased vascularization was detected by anti-CD31 antibody [green] in melanocytic tumors from bigenic mice compared to Cdk4R24C/R24 alone. E, epidermis; D, dermis. Scale bar (in yellow) = 33μm. White dashed lines, artificially added, indicate epidermal-dermal junction. Blue color corresponds to DAPI staining of the nuclei.

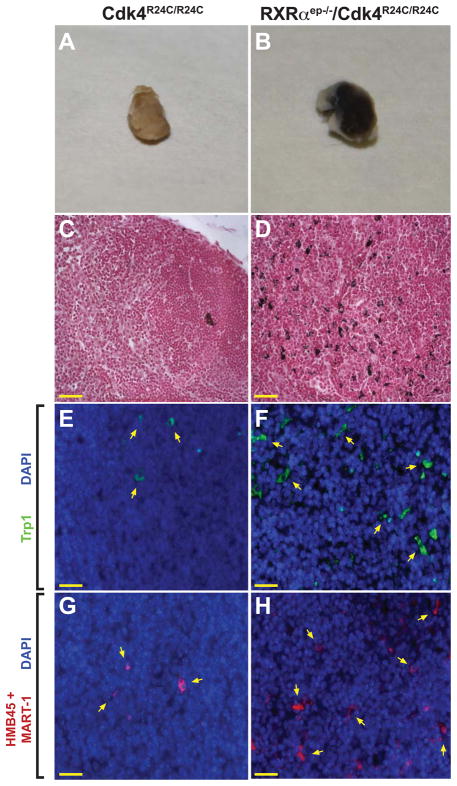

Cutaneous melanoma formed in the RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C bigenic mice metastasized to distal lymph nodes

In order to determine if combinatorial alterations of multiple molecular pathways could activate a malignant neoplastic process, we analyzed draining lymph nodes and internal organs from RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C mice for the presence of metastatic melanocytes and compared them with lymph nodes from Cdk4R24C/R24C and RXRαep−/− mice. Both the subiliac lymph nodes from each of the six surviving bigenic mice were enlarged and hyperpigmented compared to only a single lymph node belonging to one of the eight control Cdk4R24C/R24C mice (Figures 4A and 4B). Additional distal organs did not exhibit sign of metastasis in the bigenic or control mice (data not shown). Fontana Masson staining for detecting melanin granules on paraffin sections identified the presence of numerous pigmented cell types in the bigenic lymph nodes, compared to an occasional pigmented cell found in the control mice (Figures 4C and 4D and data not shown). IHC analyses of lymph nodes using an antibody raised against the melanocyte-specific enzyme Trp1 confirmed the presence of melanocytes in the draining lymph nodes from all the bigenic mice compared to only two of the control mice (Figures 4E and 4F). Similarly, IHC analyses using a melanoma cocktail for detecting malignant melanocytes confirmed the presence of multiple malignant melanocytes in the bigenic mice compared to very few cells in the control lymph nodes (Figures 4G and 4H), thus corroborating the results obtained from the Fontana Masson staining. These results demonstrate that the RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C line represents a melanoma mouse model with a tendency for metastatic progression.

Figure 4.

Lymph node metastasis in RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C mice. (A, B) Excised draining lymph nodes from Cdk4R24C/R24C and RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C mice after DMBA/TPA treatment. (C, D) Fontana-Masson staining of draining lymph nodes from Cdk4R24C/R24C and RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C mice after carcinogenic treatment. Melanin granules stain black and red corresponds to Nuclear Fast Stain. (E, F) IHC staining was performed using antibodies directed against Trp1 [green]. (G, H) IHC staining was performed using antibodies directed against HMB45 and MART-1 [red]. Scale bar (in yellow) = 33μm. Blue corresponds to DAPI staining of the nuclei.

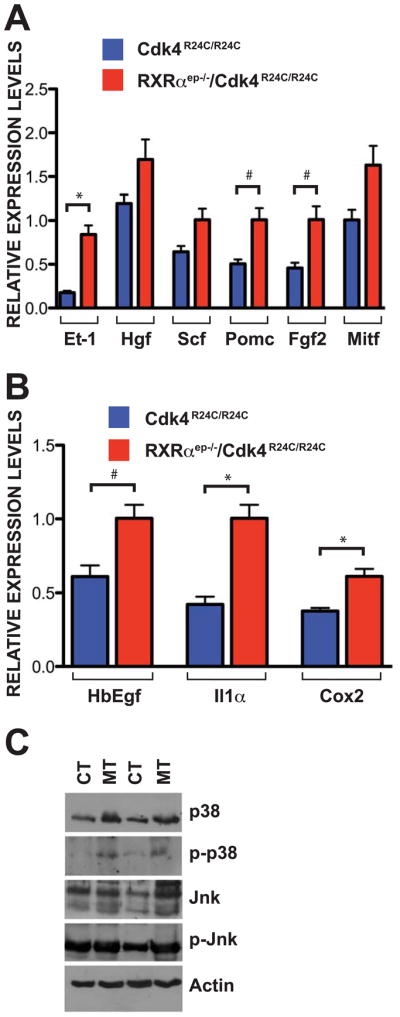

Upregulation of mitogenic factors and regulatory proteins in the skin of bigenic mice

It has previously been shown that various mitogenic growth factors secreted by keratinocytes exert both autocrine and paracrine effects in the microenvironment of the skin and contribute to melanoma formation. We therefore investigated if expression of specific soluble factors are altered in the skin of our bigenic mice. We also examined activation of regulatory proteins that lie downstream of those signaling pathways in both Cdk4R24C/R24C and RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C skin (Recio and Merlino, 2002; Tada et al., 2002).

To determine if expression of genes encoding soluble growth factors are altered at the transcriptional level, we utilized quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) to examine the relative mRNA levels in skin of RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C mice compared to the Cdk4R24C/R24C mice. Significant increases in mRNA expression level were seen for the paracrine factor Et-1 (~3.5 fold) in the skin of bigenic mice (Figure 5A). Similarly, expression of other factors such as Hgf (~1.5 fold), Fgf2 (~1.5 fold), Pomc (the precursor peptide of α-MSH, ~2 fold) and Scf (~2 fold) were also upregulated in RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C mice. We then evaluated the transcription factor Mitf that regulates expression of several genes implicated in proliferation, survival and apoptosis of melanocytes (Levy et al., 2006), since amplification of Mitf has been linked to malignant conversion of MTs (Garraway et al., 2005). Interestingly, relative mRNA levels of Mitf-M, a melanocyte specific isoform, were also found to be increased (~1.5 fold) in the skin of RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C mice compared to the control group (Figure 5A). Similarly, relative mRNA levels of Il1α and Cox2 expression were significantly upregulated (~2 fold and ~1.5 fold, respectively), and a ~1.4 fold increase was seen in HbEgF transcript levels in the skin of bigenic mice (Luger and Schwarz, 1990; Tripp et al., 2003) (Figure 5B). Protein levels and phosphorylation status of key MAPK protein family members were measured to determine if altered MAPK signaling is responsible, at least in part, for increased melanomagenesis in the bigenic mice. A modest increase in expression level of p38, Erk and Jnk proteins, and an increased phosphorylation of p38 and Jnk, was seen in the skin of RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C compared to Cdk4R24C/R24C mice (Figure 5C, and data not shown).

Figure 5.

Increased expression of paracrine factors and regulatory proteins in the skin of RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C mice. (A) Enhanced expression of mitogenic paracrine factors and regulatory proteins in skin of RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C mice compared to Cdk4R24C/R24C mice after 25 weeks of DMBA/TPA treatment. Relative mRNA transcript levels of endothelin 1 (Et-1), hepatocyte growth factor (Hgf), stem cell factor (Scf), proopiomelanocortin (Pomc), fibroblast growth factor 2 (Fgf2) and microphtalmia-associated transcription factor (Mitf) were measured. (B) Enhanced expression of autocrine factors in skin of RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C mice compared to Cdk4R24C/R24C 25 weeks after DMBA/TPA treatment. Relative mRNA transcript levels of heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HbEgf), interleukin 1-alpha (Il1α) and cyclooxygenase 2 (Cox2) were measured. (C) Western blot analysis of different proteins in the mitogenic MAPK pathway on skin extracts from RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C [MT] and Cdk4R24C/R24C [CT] mice 25 weeks after DMBA/TPA treatment. Antibodies used were against p38, phospho-p38, Jnk, phospho-Jnk. Data (A and B) represents mean ± SEM. All reactions were performed in triplicates using skin samples collected from a minimum of three different mice in each group. Statistical analyses were done using GraphPad Prism software and significance level (*) were set at p < 0.05. # = Not significant.

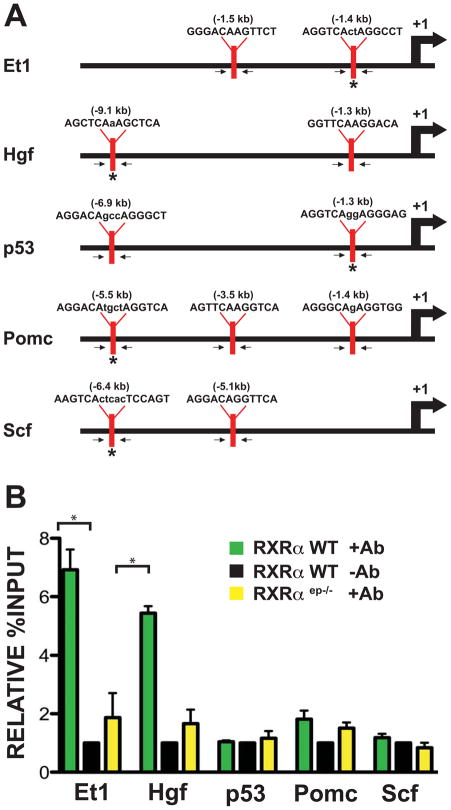

Nuclear receptor RXRα is recruited to the promoter of genes encoding paracrine factors Et-1 and Hgf in keratinocytes

It is possible that absence of RXRα in keratinocytes is increasing the basal rate of transcription for specific soluble communication factors in the skin of RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C mice through a derepression mechanism. In order to verify if keratinocytic RXRα plays a direct or indirect role in regulating the expression of soluble growth factors at the transcriptional level, we performed ex vivo chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments on extracts from primary mouse keratinocytes and determined if RXRα protein is recruited onto the promoter of target genes.

The promoters of numerous keratinocyte-derived soluble growth factors were selected as potential candidates of RXRα-mediated cell signaling. A region of ~10kb upstream of the transcriptional start site was screened for possible binding motifs of RXRα/NR heterodimers. Sequences on the promoters of Et-1, endothelin 3 (Et-3), fibroblast growth factor 7 (Fgf7), Hgf, p53, proopiomelanocortin (Pomc), nerve growth factor (Ngf), nitric oxide synthase (Nos) and Scf were targeted for further investigation and primers were designed to capture these regions (Figure 6A, data not shown). Amplification of isolated chromatin using specific primers was performed on wild-type primary keratinocytes, as well as on those collected from mutant RXRαep−/− mice. Increased promoter occupancy by RXRα protein was detected by ChIP assay 1.4kb and 9.1kb upstream of the transcriptional start site of the Et-1 and Hgf gene promoters, respectively (Figure 6B). These results suggest that RXRα is recruited to the promoter of paracrine mitogenic factors Et-1 and Hgf in murine keratinocytes.

Figure 6.

Nuclear receptor RXRα associates with target gene promoter encoding soluble growth factors in primary keratinocytes. (A) Putative RXREs identified upstream of the transcriptional start site of genes for specific soluble growth factors such as Et-1, Hgf, p53, Pomc and Scf. Arrows indicate position of primers designed to capture all potential binding sequences, asterisks (*) indicate location of results shown in figure. The position of transcriptional start site is indicated as +1, promoter diagrams not to scale. (B) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed on primary keratinocytes using antibody against RXRα protein and results were analyzed by qPCR using specific primers (indicated in A). RXRα association on consensus sequences for RXRα/NR heterodimers located on the promoters of Et-1, Hgf, p53, Pomc and Scf genes in wild type keratinocytes was compared to cells lacking RXRα protein or wild type cells immunoprecipitated with an irrelevant antibody. Endothelin 1, Et-1; proopiomelanocortin, Pomc; hepatocyte growth factor, Hgf; stem cell factor, Scf. Statistical analyses was done by Student’s unpaired T-test using GraphPad Prism software and significance level (*) were set at p < 0.05.

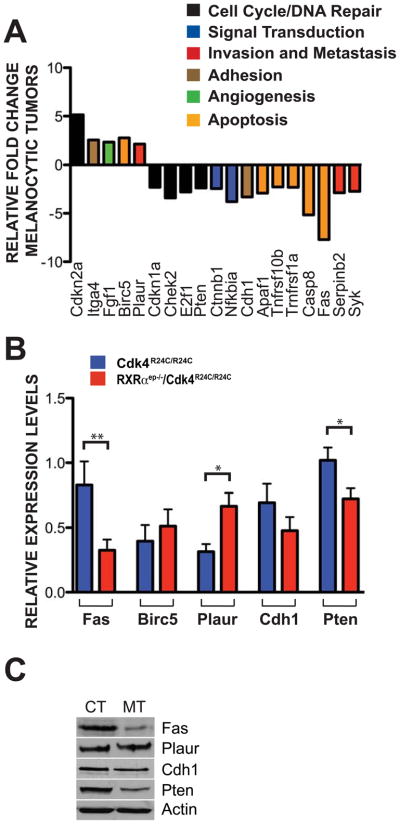

Altered gene expression in the melanocytic tumors of RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C mice

Laser-capture microdissection (LCM) was performed on frozen sections of melanocytic tumors from Cdk4R24C/R24C and RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C mice to investigate the influence of RXRα epidermal ablation on melanoma progression. Seventy percent of the pigmented melanocytic tumors were extracted from the surrounding tissue (Figures S2A and S2B). Total RNA was isolated, amplified and converted to cDNA to evaluate the differential expression of genes commonly implicated in neoplastic processes by using a qPCR-based gene array (Cancer PathwayFinder Array, SABiosciences). Approximately 30 genes were differentially regulated more than 2-fold in the array, pertaining to several distinct biochemical processes, and data was analyzed using the ddCT method (Figure 7A and Table S2). The death receptor Fas, which is involved in the extracellular response to apoptosis, was downregulated more than 7-fold. Other genes involved in apoptosis inhibition and downregulated in the mutant melanocytic tumors were caspase 8 (~5 fold), Apaf1 (~3 fold), Bcl2l1 (~4 fold), Tnfrsf10b (~2 fold), Tnfrsf1 (~2 fold), E2F1 (~3 fold), Chek2 (~3 fold), CDKN1a (~2 fold), while Birc5/survivin was upregulated (~3 fold). Elements of the plasminogen activation pathway, Plaur and Serpinb2, were up- and down-regulated (~2 and ~3 fold, respectively) in the RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C melanomas compared to those in Cdk4R24C/R24C tumors. Additionally, members of signal transduction and adhesion pathways which were upregulated included Cdkn2a (~5 fold), Itgα4 (~2 fold), and Ffg1 (~2 fold), while Syk, Nfkbia, Cdh1/E-cadherin, Pten and Ctnnb1 were downregulated (~3, ~4, ~3, ~2 and ~2 folds, respectively) (Figure 7A). We performed qRT-PCR validation on LCM samples from control and bigenic mice for some of the interesting candidates implicated in melanomagenesis such as Fas and Birc5/survivin (apoptosis), Plaur and Cdh1/E-cadherin (invasion), and the tumor suppressor Pten. The results obtained further confirmed our initial PCR array data (Figure 7B). Furthermore, western blot validation was used to determine if similar changes were present at the protein level. A downregulation in Fas, Cdh1/E-cadherin and Pten protein levels, and a mild upregulation for Plaur expression, were observed in the bigenic MTs. Birc5/survivin was not detectable by either western blot or IHC in either group (Figure 7C and data not shown). Altogether, these results demonstrate a differential regulation of apoptotic and invasive mechanisms within the transformed melanocytes from the bigenic MTs.

Figure 7.

Altered expressions of genes in laser capture microdissected (LCM) melanocytic tumors. (A) Relative fold change differences ≥ 2 of RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C mRNA transcripts taken from LCM isolated melanocytes compared to Cdk4R24C/R24C mice. Amplified cDNA was analyzed using a RT2 Nano PreAMP cDNA Synthesis Kit and evaluated using a Mouse Cancer PathwayFinder PCR Array System. Gene expression was normalized to a panel of housekeeping genes (B2m, Hprt1, Rpl13a, Gapdh, Actb). (B) Validation of PCR array results using relative mRNA transcript levels of Fas, Birc5, Plaur, Cdh1 and Pten from LCM captured melanocytes of Cdk4R24C/R24C and RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C mice treated with DMBA/TPA for 25 weeks. (C) Validation of PCR array results using western blot detection for protein levels in both RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C [MT] and Cdk4R24C/R24C [CT] melanocytic tumors using antibodies against Fas, Plaur, Cdh1 and Pten. All experiments were done using a minimum of three biological replicates from each group of mice. Data represents three individual experiments and in all cases are expressed as mean +/− SEM. Statistical significance was calculated using unpaired Student’s t-test with GraphPad Prism software. Statistical relevance indicated as follows; * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01.

Discussion

Formation of metastatic melanoma in RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C mice

We have shown that deletion of RXRα in keratinocytes contributes to the development of cutaneous melanoma after carcinogen treatment (Indra et al., 2007). Since melanocytes in the previous study were not genetically modified, it suggests an influence of paracrine signal(s) from RXRα-ablated epidermal keratinocytes on melanocyte biology during melanomagenesis. Our present study demonstrated that the addition of activated Cdk4 contributes to the malignant transformation and metastatic potential of proximal melanocytes. IHC studies on human tissues confirmed decreased expression of nuclear receptor RXRα in melanocytes during melanoma progression, thereby corroborating the results reported earlier (Chakravarti et al., 2007). In addition, we showed downregulation of RXRα expression in tumor adjacent keratinocytes from human in situ and malignant melanoma samples. Our results suggest a protective role of keratinocytic RXRα against aggressive tumor formation, the lack of which resulted in a significantly increased RGP and VGP in the bigenic RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C tumors. In order to achieve vertical growth, the nevus must acquire characteristics of both tumorigenicity and mitogenicity, properties that enable cellular proliferation within a foreign matrix (Hearing and Leong, 2006). The increase in Pcna+/Trp1+ cells within the RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C melanocytic tumors verified the presence of a large population of proliferating melanocytes. Increased staining against melanoma antibody cocktail HMB45 and MART-1 detected in the RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C tumors correlated well with the higher VGP in those mice. Similarly, CD31 staining in the bigenic skin implied that the larger MTs formed in those mice would necessitate additional vascular formation for nutritional support. Altogether, these data confirm that melanocytic tumors formed in the absence of keratinocytic RXRα, and in the presence of activated Cdk4, have increased metastatic capabilities compared to the control mice. It has been previously shown that the loss of the transcriptional regulator Taf4 in epidermal keratinocytes can lead to melanocytic tumors with invasion of lymph nodes after carcinogen treatment (Fadloun et al., 2007). It remains to be determined whether Taf4 and RXRα act through the same or different paracrine/juxtacrine pathways to regulate melanocyte homeostasis. Activating mutations in N-Ras and its downstream effector B-Raf are frequent events in human nevi and melanomas (Papp et al., 1999; Demunter et al., 2001; Garnett and Marais, 2004). Importantly, N-Ras and B-Raf mutations are mutually exclusive, strongly suggesting that both oncogenic activities are in the same linear pathway deregulating the mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. Mice bearing oncogenic N-RasQ16K or a B-RafV600E have been shown to develop melanomas mimicking the genetics and pathology of the human disease (Ackermann et al., 2005; Dhomen et al., 2009). It is possible that keratinocytic RXRα mediated NR pathway(s) also cooperate with the N-RasQ16K or B-RafV600E driven MAPK pathway towards melanoma progression in humans.

Loss of keratinocytic RXRα and increased melanomagenesis are associated with altered expression of paracrine growth factors

Previous in vitro studies have confirmed the role of numerous mitogenic factors produced in and released from keratinocytes that are involved in regulating the proliferation and differentiation of mammalian epidermal melanocytes through receptor -mediated signaling pathways. Among those factors are Et-1, α-MSH (the mature cleavage product of Pomc), Hgf, Scf and Fgf2 all of which have profound mitogenic and melanogenic effects on cultured mouse and human melanocytes (Abdel-Malek et al., 1995; Imokawa et al., 1992; Hirobe, 1992; Swope et al., 1995; Hirobe, 2001; Hirobe, 2003; Hirobe, 2004). Enhanced secretion of most of these paracrine factors upon loss of keratinocytic RXRα could potentially mediate increased mitogenesis and melanomagenesis in the bigenic mouse model. Interestingly, increased secretion of most of these paracrine factors have been seen in the skin of neonatal RXRαep−/− mice after UV exposure (Wang and Indra, unpublished data).

Downstream effectors that propagate signaling cascades initiated by these ligand-receptor interactions are not mutually exclusive of each other, but instead interact through crosstalk at multiple levels, such as the activation of Ras-MAPK pathway (van Biesen et al., 1995). It is noteworthy that the stress activated kinases p38 and Jnk, both of whose expression and subsequent phosphorylation were enhanced in the skin of RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C mice, have been shown to lie downstream of Hgf/Met signaling pathways and activate proliferation of melanoma cells (Recio and Merlino, 2002). We showed an enhanced expression of the melanocyte master regulator Mitf in the mutant skin, whose expression is shown to be regulated by both MAPK and p38 signaling (Vance and Goding, 2004 and references therein). Although independence from other cell types is a hallmark of metastatic potential, it is possible that upregulation of mitogenic factors from keratinocytes into the extracellular locale provides a pro-carcinogenic environment for melanocytic transformation (Haass and Herlyn, 2005).

Our ex vivo ChIP data demonstrated that RXRα/NR dimer was recruited on the promoter of both Et-1 and Hgf genes in murine keratinocytes. It has been previously shown that absence of RXR/NR dimers from the regulatory regions of the soluble cytokine Tslp lead to a dramatic increase in transcript levels for Tslp (Li et al., 2006). We propose a similar model of derepression on the promoters of specific soluble growth factors such as Et-1 and Hgf in our RXRαep−/− mice that increases the basal transcriptional activity due to loss of RXRα/NR. It has been reported that UV induction of Pomc is directly controlled by p53 (Cui et al., 2007). Although we have identified potential RXR/NR response elements on the promoters of both p53 and Pomc, our ChIP data did not confirm recruitment of RXRα to the promoters of either gene, suggesting an alternative mechanism(s) of Pomc regulation by RXRα.

Molecular alterations of apoptosis, invasion and mitogenic signaling in the malignant melanomas from RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C mice

We used LCM technology to show the inherent functional differences between the melanocytic tumors from Cdk4R24C/R24C and RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C mice. A significant downregulation of the death receptor Fas, which has been linked to apoptotic resistance in melanocytic lesions and melanoma cell lines (Bullani et al., 2002), was observed in the MTs from bigenic mice. The ability to disregard pro-apoptotic external stimuli in these transformed melanocytes would confer a selective advantage for both malignant transformation and therapeutic resistance (Ivanov et al., 2003; Niedojadlo et al., 2006). There was also an upregulation of the caspase activation inhibitor Birc5/Survivin, which is shown to be highly expressed in malignant melanoma but absent in normal melanocytes (Grossman et al., 1999; Ryu et al., 2007), suggesting that melanomas from RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C mice might utilize multiple pathways to attenuate apoptotic signals.

The invasion-linked protein Plaur was expressed at a higher level in the microdissected RXRαep−/−/Cdk4R24C/R24C melanomas. Although the process is poorly understood, the plasminogen-activation system has been shown to play an important role in hypoxic-induced metastasis through the upregulation of the receptor Plaur (Rofstad et al., 2002). Changes in expression levels for genes related to adhesion would be expected between tumor types with differing metastatic potential. In the MTs of bigenic mice, we showed a downregulation of Cdh1/E-cadherin expression, loss of which is a hallmark transition for metastatic progression (Hsu et al., 1996, Ryu et al., 2007). It is noteworthy that UV-induced production of Et-1 by keratinocytes is known to downregulate E-cadherin expression in both melanocytes and melanoma cells (Jamal and Schneider, 2002). Finally, a downregulation of the tumor suppressor Pten was shown in melanomas from bigenic mice, as has been previously reported in certain cases of primary melanomas. Loss of Pten favors melanoma formation by reducing apoptosis and promoting cell survival (Stahl et al., 2003; Tsao, et al., 2003).

Presently, there are concerted efforts toward producing mouse models that recapitulate the processes of human cutaneous melanoma with a goal of providing effective therapeutic strategies (Ibrahim and Haluska, 2009). Findings have led to recent advances in targeted therapy against factors implicated in melanoma progression (Solit et al, 2006; Bedikian et al, 2006), but have been less effective in preventing metastases. Further studies of mouse models investigating the individual contribution of paracrine factors during melanomagenesis are necessary. Additionally, investigations using sequentially timed ChIP and re-ChIP experiments are necessary to determine both the temporal events and recruitment cascades of regulatory proteins specific to transcriptional regulation of growth factors such as Et-1 and Hgf. Screening for genetic polymorphisms for RXRα in keratinocytes, in addition to melanocytes, is warranted in human melanoma patients, as we demonstrate keratinocytic contributions to both melanomagenesis and metastatic spread.

Methods

Mice

Generation of RXRαep−/− (Li et al., 2001) and Cdk4R24C/R24C (Rane et al., 1999) mice have previously been described. Cohorts of 8–10 sex and age-matched mice were shaved and treated with 50μg DMBA in 100μl of acetone. Five days after DMBA application, 5μg TPA in 200μl acetone was applied topically twice a week for up to 25 weeks. All mice were shaved weekly, and the number and size of melanocytic tumors were recorded. Mice were housed in our approved University Animal Facility with 12h light cycles, food and water were provided ad libitum, and institutional approval was granted for all animal experiments.

All other procedures a relocated in the Supplementary Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Professor Pierre Chambon, Daniel Metzger and Gary DeLander for both comments and critical review of the manuscript. We thank Cliff Pereira at OSU for help in statistical analysis, Anda Cornea at OHSU for assistance with LCM and Daniel Coleman for aid in sample processing. These studies were supported by grant ES016629-01A1 (AI) from NIEHS at National Institutes of Health, an OHSU Medical Research Foundation grant to AI, and by a NIEHS Center grant (ES00210) to the Oregon State University Environmental Health Sciences Center. We also thank Drs. Wayne Kradjan and Gary DeLander of the OSU College of Pharmacy for continuous support and encouragement.

References

- Abdel-Malek Z, Swope VB, Suzuki I, Akcali C, Harriger MD, Boyce ST, Urabe K, Hearing VJ. Mitogenic and melanogenic stimulation of normal human melanocytes by melanotropic peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:1789–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackermann J, Frutschi M, Kaloulis K, McKee T, Trumpp A, Beermann F. Metastasizing melanoma formation caused by expression of activated N-RasQ61K on an INK4a-deficient background. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4005–11. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altucci L, Gronemeyer H. Nuclear receptors in cell life and death. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2001;12:460–8. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00502-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedikian AY, Millward M, Pehamberger H, Conry R, Gore M, et al. BCL-2 antisense (oblimersen sodium) plus dacarbazine in patients with advanced melanoma: the Oblimersen Melanoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4738–45. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullani RR, Wehrli P, Viard-Leveugle I, Rimoldi D, Cerottini JC, Saurat JH, Tschopp J, French LE. Frequent downregulation of Ras (CD95) expression and function in melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2002;12:263–70. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200206000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarti N, Lotan R, Diwan AH, Warneke CL, Johnson MM, Prieto VG. Decreased expression of retinoid receptors in melanoma: entailment in tumorigenesis and prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4817–24. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambon P. A decade of molecular biology of retinoic acid receptors. FASEB J. 1996;10:940–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin L, Garraway LA, Fisher DE. Malignant melanoma: genetics and therapeutics in the genomic era. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2149–82. doi: 10.1101/gad.1437206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook PW, Pittelkow MR, Shipley GD. Growth factor-independent proliferation of normal human neonatal keratinocytes: production of autocrine- and paracrine-acting mitogenic factors. J Cell Physiol. 1991;146:277–89. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041460213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui R, Widlund HR, Feige E, Lin JY, Wilensky DL, Igras VE, D’orazio J, Fung CY, Schanbacher CF, Granter SR, et al. Central role of p53 in the suntan response and pathologic hyperpigmentation. Cell. 2007;128:853–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin JA, Fridlyand J, Kageshita T, Patel HN, Busam KJ, Kutzner H, Cho KH, Aiba S, Brocker EB, Leboit PE, et al. Distinct sets of genetic alterations in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2135–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demunter A, Ahmadian MR, Libbrecht L, Stas M, Baens M, Scheffzek K, Degreef H, De Wolf-Peeters C, van den Oord JJ. A novel N-ras mutation in malignant melanoma is associated with excellent prognosis. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4916–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhomen N, Reis-Filho JS, da Rocha Dias S, Hayward R, Savage K, Delmas V, Larue L, Pritchard C, Marais R. Oncogenic Braf induces melanocyte senescence and melanoma in mice. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:294–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digiovanni J. Multistage carcinogenesis in mouse skin. Pharmacol Ther. 1992;54:63–128. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(92)90051-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadloun A, Kobi D, Pointud JC, Indra AK, Teletin M, Bole-Feysot C, Testoni B, Mantovani R, Metzger D, Mengus G, et al. The TFIID subunit TAF4 regulates keratinocyte proliferation and has cell-autonomous and non-cell-autonomous tumour suppressor activity in mouse epidermis. Development. 2007;134:2947–58. doi: 10.1242/dev.005041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher GJ, Voorhees JJ. Molecular mechanisms of retinoid actions in skin. FASEB J. 1996;10:1002–13. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.9.8801161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnett MJ, Marais R. Guilty as charged: B-Raf is a human oncogene. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:313–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garraway LA, Widlund HR, Rubin MA, Getz G, Berger AJ, Ramaswamy S, Beroukhim R, Milner DA, Granter SR, Du J, et al. Integrative genomic analyses identify MITF as a lineage survival oncogene amplified in malignant melanoma. Nature. 2005;436:117–22. doi: 10.1038/nature03664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman D, Mcniff JM, Li F, Altieri DC. Expression and targeting of the apoptosis inhibitor, survivin, in human melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:1076–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haass NK, Herlyn M. Normal human melanocyte homeostasis as a paradigm for understanding melanoma. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2005;10:153–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1087-0024.2005.200407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker E, Muller HK, Irwin N, Gabrielli B, Lincoln D, Pavey S, Powell MB, Malumbres M, Barbacid M, Hayward N, et al. Spontaneous and UV radiation-induced multiple metastatic melanomas in Cdk4R24C/R24C/TPras mice. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2946–52. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halaban R, Langdon R, Birchall N, Cuono C, Baird A, Scott G, Moellmann G, McGuire J. Basic fibroblast growth factor from human keratinocytes is a natural mitogen for melanocytes. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:1611–9. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.4.1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halaban R, Rubin JS, Funasaka Y, Cobb M, Boulton T, Faletto D, Rosen E, Chan A, Yoko K, White W, et al. Met and hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor signal transduction in normal melanocytes and melanoma cells. Oncogene. 1992;7:2195–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearing VJ, Leong SPL. From melanocytes to melanoma: the progression to malignancy. Totowa, N.J: Humana Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hirobe T. Basic fibroblast growth factor stimulates the sustained proliferation of mouse epidermal melanoblasts in a serum-free medium in the presence of dibutyryl cyclic AMP and keratinocytes. Development. 1992;114:435–45. doi: 10.1242/dev.114.2.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirobe T. Endothelins are involved in regulating the proliferaion and differentiation of neonatal mouse epidermal melanocytes in serum-free primary culture. J Invest Dermatol Symp Proc. 2001;6:25–31. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirobe T, Osawa M, Nishikawa SI. Steel factor controls the proliferation and differentiation of neonatal mouse epidermal melanocytes in culture. Pigment Cell Res. 2003;16:644–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-0749.2003.00092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirobe T, Osawa M, Nishikawa SI. Hepatocyte growth factor controls the proliferation of cultured epidermal melanblasts and melanocytes from newborn mice. Pigment Cell Res. 2004;17:51–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-0749.2003.00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirobe T. Role of keratinocyte-derived factors involved in regulating the proliferation and differentiation of mammalian epidermal melanocytes. Pigment Cell Res. 2005;18:2–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2004.00198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu MY, Wheelock MJ, Johnson KR, Herlyn M. Shifts in cadherin profiles between human normal melanocytes and melanomas. J Invest Dermatol Symp Proc. 1996;1:188–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim N, Haluska FG. Molecular pathogenesis of cutaneous melanocytic neoplasms. Annu Rev Pathol. 2009;4:551–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.3.121806.151541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imokawa G, Yada Y, Miyagishi M. Endothelins secreted from human keratinocytes are intrinsic mitogens for human melanocytes. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:24675–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indra AK, Castaneda E, Antal MC, Jiang M, Messaddeq N, Meng X, Loehr CV, Gariglio P, Kato S, Wahli W, et al. Malignant transformation of DMBA/TPA-induced papillomas and nevi in the skin of mice selectively lacking retinoid-X-receptor alpha in epidermal keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1250–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov VN, Bhoumik A, Ronai Z. Death receptors and melanoma resistance to apoptosis. Oncogene. 2003;22:3152–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal S, Schneider RJ. UV-induction of keratinocyte endothelin-1 downregulates E-cadherin in melanocytes and melanoma cells. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:443–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI13729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez M, Kameyama K, Maloy WL, Tomita Y, Hearing VJ. Mammalian tyrosinase: biosynthesis, processing, and modulation by melanocyte-stimulating hormone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:3830–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.11.3830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamb A, Gruis NA, Weaver-Feldhaus J, Liu Q, Harshman K, Tavtigian SV, Stockert E, Day RS, 3rd, Johnson BE, Skolnick MH. A cell cycle regulator potentially involved in genesis of many tumor types. Science. 1994;264:436–40. doi: 10.1126/science.8153634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastner P, Gronodona JM, Mark M, Gansmuller A, LeMeur M, Decimo D, Vonesch JL, Dolle P, Chambon P. Genetic analysis of RXR alpha developmental function: convergence of RXR and RAR signaling pathways in heart and eye morphogenesis. Cell. 1994;78:987–1003. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90274-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunisada T, Yoshida H, Yamazaki H, Miyamoto A, Hemmi H, Nishimura E, Shultz LD, Nishikawa S, Hayashi S. Transgene expression of steel factor in the basal layer of epidermis promotes survival, proliferation, differentiation and migration of melanocyte precursors. Development. 1998;125:2915–23. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.15.2915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larue L, Beerman F. Cutaneous melanoma in genetically modified animals. Pigment Cell Res. 2007;20:485–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2007.00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy C, Khaled M, Fisher DE. MITF: master regulator of melanocyte development and melanoma oncogene. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:406–14. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Chiba H, Warot X, Messaddeq N, Gerard C, Chambon P, Metzger D. RXR-alpha ablation in skin keratinocytes results in alopecia and epidermal alterations. Development. 2001;128:675–88. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.5.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Hener P, Zhang Z, Kato S, Metzger D, Chambon P. Topical vitamin D3 and low-calcemic analogs induce thymic stromal lymphopoietin in mouse keratinocytes and trigger an atopic dermatitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11736–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604575103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luger TA, Schwarz T. Evidence for an epidermal cytokine network. J Invest Dermatol. 1990;95:100S–104S. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12874944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangahas CR, dela Cruz GV, Scheider RJ, Jamal S. Endothelin-1 upregulates MCAM in melanocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123:1135–9. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangelsdorf DJ, Borgmeyer U, Heyman RA, Zhou JY, Ong ES, Oro AE, Kakizuka A, Evans RM. Characterization of three RXR genes that mediate the action of 9-cis retinoic acid. Genes Dev. 1992;6:329–44. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangelsdorf DJ, Thummel C, Beato M, Herrlich P, Schutz G, Umesono K, Blumberg B, Kastner P, Mark M, Chambon P, et al. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell. 1995;83:835–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger D, Indra AK, Li M, Chapellier B, Calleja C, Ghyselinck NB, Chambon P. Targeted conditional somatic mutagenesis in the mouse: temporally-controlled knock out of retinoid receptors in epidermal keratinocytes. Methods Enzymol. 2003;364:379–408. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(03)64022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedojadlo K, Labedzka K, Lada E, Milewska A, Chwirot BW. Apaf-1 expression in human cutaneous melanoma progression and in pigmented nevi. Pigment Cell Res. 2006;19:43–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2005.00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka T, Takayama H, Sharp, Celli G, LaRochelle WJ, Bottaro DP, Ellmore N, Vieira W, Owens JW, Merlino G, et al. c-Met autocrine activation induces development of malignant melanoma and acquisition of the metastatic phenotype. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5157–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp T, Pemsel H, Zimmermann R, Bastrop R, Weiss DG, Schiffmann D. Mutational analysis of the N-ras, p53, p16INK4a, CDK4, and MC1R genes in human congenital melanocytic naevi. J Med Genet. 1999;36:610–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rane SG, Dubus P, Mettus RV, Galbreath EJ, Boden G, Reddy EP, Barbacid M. Loss of Cdk4 expression causes insulin-deficient diabetes and Cdk4 activation results in beta-islet cell hyperplasia. Nat Genet. 1999;22:44–52. doi: 10.1038/8751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recio JA, Merlino G. Hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor activates proliferation in melanoma cells through p38 MAPK, ATF-2 and cyclin D1. Oncogene. 2002;21:1000–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rofstad EK, Rasmussen H, Galappathi K, Mathiesen B, Nilsen K, Graff BA. Hypoxia promotes lymph node metastasis in human melanoma xenografts by up-regulating the urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1847–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu B, Kim DS, Deluca AM, Alani RM. Comprehensive expression profiling of tumor cell lines identifies molecular signatures of melanoma progression. PLoS One. 2007;2:e594. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott . Melanosome Trafficking and Transfer. In: Nordlund, editor. The Pigmentary System. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Solit DB, Garraway LA, Pratilas CA, Sawai A, Getz G, et al. BRAF mutation predicts sensitivity to MEK inhibition. Nature. 2006;439:358–62. doi: 10.1038/nature04304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotillo R, Garcia JF, Ortega S, Martin J, Dubus P, Barbacid M, Malumbres M. Invasive melanoma in Cdk4-targeted mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13312–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241338598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl JM, Cheung M, Sharma A, Trivedi NR, Shanmugam S, Robertson GP. Loss of PTEN promotes tumor development in malignant melanoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2881–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sucov HM, Dyson E, Gumeringer CL, Price J, Chien KR, Evans RM. RXR alpha mutant mice establish a genetic basis for vitamin A signaling in heart morphogenesis. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1007–18. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.9.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swope VB, Medrano EE, Smalara D, Abdel-Malek ZA. Long-term proliferation of human melanocytes is supported by the physiologic mitogens α-melanotropin, endothelin-1, and basic fibroblast growth factor. Exp Cell Res. 1995;217:453–59. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada A, Pereira E, Beitner-Johnson D, Kavanagh R, Abdel-Malek ZA. Mitogen- and ultraviolet-B-induced signaling pathways in normal human melanocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:316–22. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tormo D, Ferrer A, Gaffal E, Wenzel J, Basner-Tschakarjan E, Steitz J, Heukamp LC, Gutgemann I, Buettner R, Malumbres M, et al. Rapid growth of invasive metastatic melanoma in carcinogen-treated hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor-transgenic mice carrying an oncogenic CDK4 mutation. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:665–72. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripp CS, Blomme EA, Chinn KS, Hardy MM, LaCelle P, Pentland AP. Epidermal COX-2 induction following ultraviolet irradiation: suggested mechanism for the role of COX-2 inhibition in photoprotection. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:853–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao H, Mihm MC, Jr, Sheehan C. PTEN expression in normal skin, acquired melanocytic nevi and cutaneous melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:865–72. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(03)02473-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Biesen T, Hawes BE, Luttrell DK, Krueger KM, Touhara K, Porfiri E, Sakaue M, Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ. Receptor-tyrosine-kinase- and G beta gamma-mediated MAP kinase activation by a common signalling pathway. Nature. 1995;376:781–4. doi: 10.1038/376781a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance KW, Goding CR. The transcription network regulating melanocyte development and melanoma. Pigment Cell Melananoma Res. 2004;17:318–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2004.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Stockard CR, Harkins L, Lott P, Salih C, Yuan K, Buchsbaum D, Hahim A, Zayzafoon M, Hardy RW, et al. Immunohistochemistry in the evaluation of neovascularization in tumor xenografts. Biotech Histochem. 2008;83:179–89. doi: 10.1080/10520290802451085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waseem NH, Lane DP. Monoclonal antibody analysis of the proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA). Structural conservation and the detection of a nucleolar form. J Cell Sci. 1990;96(Pt 1):121–9. doi: 10.1242/jcs.96.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfel T, Hauer M, Schneider J, Serrano M, Wolfel C, Klehmann-Hieb E, DE Plaen E, Hankeln T, Meyer zum Buschenfeld KH, Beach D. A p16INK4a-insensitive CDK4 mutant targeted by cytolytic T lymphocytes in a human melanoma. Science. 1995;269:1281–4. doi: 10.1126/science.7652577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki F, Okamoto H, Matsumura Y, Tanaka K, Kunisada T, Horio T. Development of a new mouse model (xeroderma pigmentosum a-deficient, stem cell factor-transgenic) of ultraviolet B-induced melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:521–5. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo L, Weger J, Yang Q, Goldstein AM, Tucker MA, Walker GJ, Hayward N, Dracopoli NC. Germline mutations in the p16INK4a binding domain of CDK4 in familial melanoma. Nat Genet. 1996;12:97–9. doi: 10.1038/ng0196-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.