Abstract

Past studies on β-catenin in cancer cells focused on nuclear localized β-catenin and its involvement in the Wnt pathway. Our goal here was to investigate the function of β-catenin in both the cytoplasm and nucleus on the regulation of MT1-MMP expression and activity. We found that β-catenin in MDCK non-cancer cells inhibited the cell surface localization of MT1-MMP, and thus its proteolytic activity on pro-MMP2 activation, via direct interaction with the 18-amino acid cytoplasmic tail of MT1-MMP in the cytoplasm. In contrast, β-catenin in HT1080 cancer cells enhanced the activity of MT1-MMP by entering the nucleus and activating transcription factor Tcf-4/Lef, and elevating the level of MT1-MMP protein. We also found that enhancement of cell growth in 3-D/2-D type I collagen gels and of cell migration by MT1-MMP were inhibited by β-catenin in MDCK cells, whereas these functions were enhanced in HT1080 cells. In addition, regulation of MT1-MMP by β-catenin involved E-cadherin in MDCK cells and Wnt-3a in HT1080 cells. Taken together, our results present a differential effect of cytoplasmic and nuclear β-catenin on MT1-MMP activity in non-cancer cells versus cancer cells. These differences were most probably due to different subcellular locations and different involved pathways of β-catenin in these cells.

Keywords: β-catenin, MT1-MMP, interacting/associating, cytoplasmic tail of MT1-MMP

INTRODUCTION

Membrane-type matrix metalloproteinase 1 (MT1-MMP), a member of the MMP super-family, is a key protein in physiological and pathological processes from normal cell development to cancer cell growth (Seiki, 2002/2003; Hiraoka et al, 1998; Zhou et al, 2000). Its main function is as a cell surface proteinase and it displays a broad spectrum of activity against ECM components such as type I and II collagen, fibronectin, vitronectin, laminin, fibrin and proteoglycan. Various cell types employ MT1-MMP to alter their surrounding environment during angiogenesis, tissue remodeling, tumor invasion, and metastasis (Hotary et al, 2000; Stetler-Stevenson et al, 1993; Ohuchi et al, 1997; Lethti et al, 2002; d’Ortho et al, 1997; Koshikawa et al, 2000; Li et al, 2004; Brown et al, 1990; Overall and Lopez-Otin, 2002). There are three methods to regulate the activity of MT1-MMP: one is via binding to its endogenous inhibitors, TIMP-2 and TIMP3 (Will et al, 1996; Bigg et al, 2001); the second is via protein trafficking between the cytoplasm and plasma membrane (regulated by other proteins, such as Clathrin, Caveolin, Src, Rab8, etc.(Gálvez et al, 2004; Jiang et al. 2004; Uekita et al, 2001; Remacle and Roghi, 2003; Nyalendo et al, 2007; Bravo-Cordero et al, 2007); and the third is transcriptional and translational control. Transcription of MT1-MMP can be regulated by signal pathways, such as the Wnt-β-catenin-Tcf4 signal pathway (Hlubek et al, 2004; Nawtocki-Raby et al, 2003).

β-catenin is a multifunctional protein involved in both cell-cell adhesion and Wnt signaling. It has a structural role in cell adhesion by binding to cadherins at the intracellular surface of the plasma membrane and a signaling role in the cytoplasm as the penultimate downstream mediator of the Wnt signaling pathway (Fu et al, 2008; Novak and Dedhar, 1999; Takemaru et al, 2008). As an essential co-activator downstream of Wnt signaling, β-catenin regulates many biological processes essential for proper embryonic development and adult homeostasis, and also in tumor formation, growth, invasion and metastasis (Fu et al, 2008; Novak and Dedhar, 1999; Takemaru et al, 2008). β-catenin is normally found in three intracellular locations: (i) at the plasma membrane bound to cadherins and forming a link to the cytoskeleton through α-catenin; (ii) in the cytoplasm as the β-catenin pool of the cell, and (iii) in the nucleus as a mediator regulating gene expression. In the cytoplasm, β-catenin is ether free or in a complex with APC. Phosphorylation of APC and β-catenin by GSK3 results in β-catenin degradation by ubiquitination and the proteosome pathway. When Wnt is over expressed, the amount of β-catenin entering the nucleus is increased with a concomitant decrease in cytoplasm β-catenin concentration (Miller and Moon, 1996; Barth et al, 1997; Gumbiner, 1997; Polakis, 1997).

Study of the functions of β-catenin has mainly focused on two aspects of its cellular localization. One is β-catenin bound with cadherins in cell adhesion, and the other is about nuclear β-catenin participating in Wnt signaling and binding to transcription factor Lef-1/Tcf-4 to co-regulate gene expression. MT1-MMP is one target gene of Lef-1/Tcf-4 (Takahashi et al, 2002). In E-cadherin-transfected cancer cells, over-expressed E-cadherin can mediate MT1-MMP down-regulation by sequestrating free cytoplasmic β-catenin and decreasing the β-catenin entering the nucleus and decreasing β-catenin induced transcriptional activity (Nawrochi-Raby et al, 2003). Thus, a dynamic balance exists among these three pools of β-catenin: i.e., cytoplasmic, nuclear, and bound to cadherins.

Generally, E-cadherin levels are high in normal or non-cancer cells but less in cancer cells; whereas, Wnt is high in cancer cells and very low in non-cancer cells. In this study, after screening several non-cancer and cancer cell lines, we selected two typical cell lines, non-cancer MDCK cells and HT1080 cancer cells, as experimental cell line models. Our data show that β-catenin can interact/associate with MT1-MMP and inhibit its proteolysis activity and bio-functions in MDCK cells, whereas in HT1080 cells, ectopically expressed β-catenin increases the activity of MT1-MMP via Wnt signaling pathway. Inhibiting the expression of endogenous E-cadherin with siRNA in MDCK cells increased the inhibition of MT1-MMP activity, whereas, inhibiting expression of β-catenin increased the activity of MT1-MMP; but decreased in HT1080. Thus, β-catenin appears to have a new mechanism of regulating MT1-MMP that may explain the differences of β-catenin effects in normal and cancer cells, and may also provide new clues for further understanding cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and transfection

All tissue culture reagents were purchased from BRL-GIBCO. Normal cell lines, MDCK, IMR-90, CRL-2097, and cancer cell line HT1080 were obtained from the American type culture collection (ATCC) and subcloned subsequently. Cancer cells 1205LU and WM1341D were generously provided by Dr. James B McCathy’s lab (Masonic Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Minnesota). Subline MDCK-umn (Pei, 1999) is epithelial-like in cell shape and grows well in DMEM and was used throughout the experiments. The cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine sera (FBS), L-glutamine (2mM) and streptomycin/penicillin (50units/ml). 1205LU, WM1341D, IMR-90 and CRL-2097 cells were maintained in MEM with 10% FBS and streptomycin/penicillin (50units/ml). HT1080 cells were maintained as described (Pei and Weiss, 1996; Pei, 1999). All cells were cultured within a growth chamber with 5% CO2/95% air at 37°C

Before transfection, cells were seeded and cultured in 5% FBS medium for 24h. The DNA constructs and siRNAs were transfected into various cells by Lipofectamine 2000 using protocols as described by the manufactor (Invitrogen, Inc.). The transfection efficiencies with pcDNA3.1(+)-GFP plasmids were about 73% in MDCK, IMR-90, CRL-2097 cells and about 80% in HT1080, 1205LU, and WM1341D cells.

Plasmids and siRNAs

pcDNA3.1(+)uni-MT1-MMP, and MT1-MMP/ΔC (cytoplasmic tail truncation) were described previously (Hotary et al, 2000; d’Ortho et al, 1997). pcDNA3.1(+)uni-β-catenin was cloned by using general PCR methods. The PCR primers for β-catenin are: forward 5’ ACCGGATCCATGGCTACTCAAGCTGATTTGATGGAGTTGGAC 3’, and reverse 5’ CACTCTAGATTACAGGTCAGTATCAAACCAGGCCAGCTGATTGC 3’; the restriction enzymes used were BamHI and XbaI. pcDNA3.1(+)uni-Wnt-3a was constructed by our lab previously (simply, it was constructed by inserting the Wnt-3a cDNA, which was amplified via RT-PCR from cDNA library bought from Invitrogen, Inc., into pcDNA3.1(+) vector). A pool of siRNAs for the human β-catenin (sc-29209), E-cadherin (sc-35242) and Wnt-3a (sc-41106) gene and nonspecific control siRNAs (sc-37007) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Carlsbad, CA, USA.

Antibodies and chemicals

A polyclonal antibody against purified MT1-MMP catalytic domain was raised by immunizing rabbits and affinity-purified as described previously (Lehti et al, 2002; Jiang et al, 2001; Itoh et al, 2001), and an antibody against full length MT1-MMP was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Carlsbad, CA, USA. Other protein-specific antibodies were as follows: anti-β-catenin, anti-Wnt-3a, anti-E-cadherin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Carlsbad, CA, USA); anti-β-Actin (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. Danvers, MA, USA). Lipofectamine 2000 was from Invitrogen Corporation. Type I collagen was purchased from Collaborative Research, Bedford, MA. Alexa Fluor® 488 goat anti-mouse IgG and Alexa Fluor® 594 goat anti-rabbit IgG were purchased from Invitrogen Inc. Other general chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) or Fisher (Pittsburgh, PA, USA).

Generation of Stable cell line and Extracts of cytoplasm and nuclei of cells

MT1-MMP plasmids were transfected into MDCK cells by using Lipofectamine 2000, and stable clones were selected in the presence of 1mg/mL G418 as described previously (Jiang and Pei, 2003). The stable clones were screened for proMMP2 activation by a zymography assay and western blot analysis by using the anti-MT1-MMP catalytic domain antibody. At least two representative clones were selected for the experiments.

Extracts of cytoplasm and nuclei were prepared as previous described (Colangelo et al, 1998; Bachis et al, 2008). In brief, cells were homogenized in lysis buffer [10mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) pH 7.6, 15 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1mM DTT, 0.1% (v/v) Nonidet-P40, 0.5mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride, proteinase inhibitor cocktail] and incubated on ice for 10min. Nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation at 4000 × g for 10min at 4°C. The supernatant contained the cytosolic fraction. Nuclear proteins were then extracted in high salt buffer (420 mM NaCl, 25 mM HEPES pH 7.6, 25% glycerol, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.5mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride, proteinase inhibitor cocktail) by shaking at 4 °C for 30 min. Nuclear debris was removed by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 10 min; and the supernatant together with cytosolic fraction were assayed by western blot.

Zymography, Western Blotting and immunoprecipitation

Zymography gel assay was performed as described before (Jiang and Pei, 2003). In brief, cells were cultured in 12-well plate and transfected as indicated. After 24h, cells were washed 3 times with PBS and a media with 5% FBS (the source of the proMMP2) was added at 0.5 ml/well. The media were harvested 24h and 48h later for plasmid transfection and siRNA transfection experiments, respectively. The media were cleared by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 10 min, and subjected to analysis by SDS-PAGE impregnated with 1 mg/ml gelatin as described previously (Pei, 1999). The gels were incubated at 37°C overnight, stained with Coomassie Blue, destained, and then scanned. For Western blotting and immunoprecipitation experiments, the cells were cultured in media with 5µM of the MMP inhibitor GM6001 (Sigma-Aldrich) to prevent auto-degradation. These cells were lysed in lysis buffer (50mM Tris-HCl, pH7.5, 150mM NaCl, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% Nonidet P-40 and a mixture of protease inhibitors), cleared by centrifugation, and immunoprecipitation of the resulting supernants were done as described previously (Kang et al, 2000). Western blotting analysis of immunoprecipitation was done with specific antibodies as described in the figures.

Reverse Transcription PCR (RT–PCR)

Total cellular RNA was extracted from snap-frozen cell pellets using the Trizol reagent (Life Technologies, Inc., Burlington, Ontario, Canada) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Two µg of total RNA were reverse transcribed by using a reaction mixture containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 30 mM KCl, 8 mM MgCl2,10 mM DTT, 100 ng oligo(dT)12–18, 40 units of RNase inhibitor, 1 mM deoxynucleotide triphosphates, and eight units of avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (all from Pharmacia Biotech, Baie D’Urfe, Quebec, Canada). The mixture was incubated for 10 min at 25°C, then for 45 min at 42°C, and finally for 5 min at 95°C. The primers used were as follows: for MT1-MMP: sense 5’-CGC TAC GCC ATC CAG GGT CTC AAA-3’, antisense 5’-CGG TCA TCA TCG GGC AGC ACA AAA-3’ (expected product 497 bp); for beta-actin: sense 5’-GGA CTT CGA GCA AGA GAT GG-3’, antisense 5’-AGC ACT GTG TTG GCG TAC AG-3’ (expected product 234 bp). The cDNA was amplified using 35 cycles, each of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 55°C and 30 s at 72°C, followed by a 10min incubation at 72°C. In the preliminary experiments, it was confirmed that under these conditions, the RT-PCR products were obtained during the exponential phase of the amplification curve. The amplified DNA fragments were analyzed by electrophoresis in 1.2% agarose gels.

Cell Proliferation Assay and Growth of MDCK and HT1080 Cells in Three- and Two- dimensional Type I collagen Lattice

Before assaying cell growth in collagen matrices, we assayed the effect of β-catenin on MT1-MMP activity and cell proliferation in MDCK and HT1080 cells. Equal concentration of MDCK and HT1080 cells were seeded in 6-well and 96-well plates. After 24h, cells were transfected as indicating in figure 5. 48h later, cell proliferation was assayed by using both cell counting/Trypan Blue (Biocompare, CA, USA) and 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT, 5 mg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich) methods according to their instructions, respectively.

Figure 5. Effects of β-catenin on the cell proliferation of MDCK and HT1080 cells via the activity of MT1-MMP.

MDCK and HT1080 cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1, MT1-MMP or co-transfected MT1-MMP and β-catenin; and 48h later, cell proliferation were assayed by using Trypan Blue/cell counting method (A) and MTT method (B). The relative cell numbers (the ratio of transfection vs non-transfection) were showed here. The values were the average of three parallel experiment values.

To assay cell growth in 2-D and 3-D type I collagen lattices, cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a concentration of 1×105. After 24h incubation, cells were transfected with plasmids as indicated by using Lipofectamine 2000. At 24h after transfection, the same number of cells (1×103) was mixed with 500 µl of type I collagen (2.5 mg/ml) and the mixture at 37°C was added into 24-well plates to give rise to three-dimensional collagen lattices. Fresh medium containing 10% FBS was added to the wells and changed every 2 days. One week later, cells were photographed with a video camera at the University of Minnesota Biomedical Image Processing Laboratories as described previously (Kang et al, 2000). For the two-dimensional type I collagen assay, cells were transfected as described above and cultured in full media. 24h after transfection, equal amounts of tyrpsinized cells (1×103) were seeded on the surface of solidified type I collagen gels in 24-well plates. One week later, cells on the surface of 2-D type I collagen gel were photographed as described above.

Migration Assay of MDCK and HT1080 Cells

Cell motility was tested using a scratch wound assay as described before (Mercure et al, 2008). In brief, equal numbers of MDCK or HT1080 or stable MDCK cells were seeded in duplicate wells in a 6-well culture plate. After growth to about 90% confluency, cells were transfected with plasmids as indicated in individual figures. When the plates were grown to confluency in appropriate full medium containing 10% fetal calf serum, a scratch was made along the axis of the plate using a pipette tip. Cells were washed three times with PBS buffer, and media were changed after scratching. Migration of cells into the scratch was photographed at 48 h.

Immunostaining and Confocal Microscopy

Cells were grown on glass coverslips and transfected with the indicated plasmids. After being cultured with GM6001 (5µM) for 48h, cells were fixed with 4% polyformaldehyde for 20 min and incubated with PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5min. After blocking with 3% goat serum in PBS, 0.2 µg/ml anti-MT1-MMP antibody (mouse anti-human) and anti-β-catenin antibody (rabbit anti-human) were added to the cells and they were incubated at 4°C overnight. Secondary antibodies used to detect the primary antibody Alexa Fluor® 594 labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG and Alexa Fluor® 488 labeled goat anti-mouse IgG. Confocal microscopy was carried out in the Biomedical Image Processing laboratories at the University of Minnesota using a Bio-Rad MRC 1024 system attached to an Olympus microscope (Melville, NY) with a 60X oil objective. The images were processed in Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe, San Jose, CA).

Data analysis and Statistics

Experiments were carried out with three or four replicates. All quantitative data were presented as mean ± SD or SEM as noted in the figure legends. Statistical analysis was done with Student’s t test using Microsoft Excel computer program (two-tail assays unless noted in the figure legends). Values of P<0.05 are considered significant.

RESULTS

Screening β-catenin, E-cadherin and MT1-MMP in several non-cancer and cancer cell lines

To study the effects of β-catenin on the activity and function of MT1-MMP in non-cancer and cancer cells, we first screened the non-cancer cell lines MDCK, IMR-90 and CRL-2097, and cancer cell lines HT1080, 1205LU, and WM1341D for expression of the proteins β-catenin, E-cadherin and MT1-MMP. The non-cancer cells all grew in clustering phenotype, whereas cancer cells grew in a scattered morphology (fig.1A). In consideration of cell phenotypes, E-cadherin was only expressed in non-cancer cells and expression of β-catenin was higher in non-cancer than cancer cells (fig.1B(a)). Upon separation of cytoplasminc and nuclear fractions, we found β-catenin protein to be located in the cytoplasm and absent in nuclei in the non-cancer cells. On the other hand, β-catenin was located both in nuclei (mainly) and in cytoplasm in cancer cells (fig.1B(b)). Interestingly, no MT1-MMP protein was detecable in the non-cancer cells. In contrast again, all cancer cells expressed the MT1-MMP protein, with HT1080 cells having the highest expression (fig.1B(a)). Thus, there was a similar relationship of β-catenin, E-cadherin and MT1-MMP expression in these cell lines of the non-cancer or cancer groups.

Figure 1. Cell phenotype and expression of several proteins in non-cancer and cancer cell lines, and the effect of β-catenin on the activity of MT1-MMP in MDCK and HT1080 cells.

(A) Phenotypes of several non-cancer and cancer cell lines including HT1080, 1205LU, WM1341D, MDCK, IMR-90 and CRL-2097, and screening MT1-MMP, β-catenin and E-cadherin protein expression in the same cell lines. (B) The cell lines (as above) were cultured in dishes, and two dishes of each cell line were harvested and lysed in lysis buffer and cytoplasminc and nuclear extract were prepared and subjected to Western blotting. CE: cytoplasmic extracts; NE: nuclear extracts. (C) Effects of β-catenin dose on the activity of MT1-MMP in MDCK cells. MDCK cells were transfected or co-transfected with MT1-MMP or MT1-MMP and β-catenin; whereas HT1080 cells were just transfected with β-catenin (two sets of cells were done for each experiment; one for zymogram gel assay and the other for Western blot). (D) Effects of β-catenin dose on the activity of MT1-MMP in HT1080 cells. (E) and (F) The effects of β-catenin siRNA on the MT1-MMP activity in MDCK and HT1080 cells.

Comparison of the effects of β-catenin in MDCK and HT1080 cells on the activity of MT1-MMP

In cancer cells, β-catenin and E-cadherin have been reported to regulate the activities and functions of MT1-MMP through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway via transcription of MT1-MMP by binding of β-catenin with transcription factors, such as TCF-4 (Nawrocki-Raby et al, 2003; Takahashi et al, 2002). Here we compared the effect of β-catenin on the activity of MT1-MMP in non-cancer and cancer cells, and examined whether β-catenin plays a differential role between non-cancer and cancer cells.

Based on our above results, we selected the non-cancer cell line MDCK and cancer cell line HT1080 as respective models to study the role of β-catenin in regulating MT1-MMP activity. These two cell lines represent different cellular phenotypes, i.e., MDCK cells grew in clusters and HT1080 cells scattered (fig.1A); MDCK cells expressed high levels of E-cadherin and β-catenin, whereas HT1080 cells expressed a relatively low level of β-catenin and almost no E-cadherin, which may explain why MDCK cells grew in clustered and HT1080 in scattered morphology. MT1-MMP was expressed in HT1080 cells but not in MDCK cells (fig.1A and 1B(a)).

When MT1-MMP and β-catenin were co-transfected into MDCK cells, the proMMP-2 activating activity of MT1-MMP was inhibited by β-catenin in a dose-dependent manner (fig.1C); the same results were obtained in the IMR-90 and CRL-2097 cells (data not shown). However, in HT1080 cells, MT1-MMP activities were increased upon transfection of β-catenin, and the degree of activation was also increased with the dose of β-catenin (fig.1D). In addition, when MT1-MMP was co-transfected with β-catenin siRNA in MDCK cells, the activity of MT1-MMP was increased, concomitant with decreased endogenous β-catenin protein (fig.1E); whereas the activity of MT1-MMP was decreased upon transfection of β-catenin siRNA in HT1080 cells (fig. 1F). These results suggested that β-catenin can inhibit MT1-MMP activities in non-cancer cells, the MDCK cell line; but the reverse effect is observed in cancer cells such as the HT1080 cell line.

Interaction and co-localization of β-catenin and MT1-MMP

To determine if β-catenin inhibited the activities of MT1-MMP via an interaction between the two proteins, imunoprecipitation and confocal microscopy experiments were carried out. MDCK cells were transfected with MT1-MMP, and HT1080 cells were transfected with β-catenin alone. At 48 h after transfection, cells were collected and cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with either an anti-MT1-MMP antibody or an anti-β-catenin antibody. As demonstrated in Figure 2A, in MDCK cells, β-catenin was detected in the protein complex immunoprecipitated by the anti-MT1-MMP antibody; reciprocally, MT1-MMP was detected in the protein complex immunoprecipitated by the anti-β-catenin antibody (Fig. 2A). E-cadherin was not detected in the western blots of protein immunoprecipitated with either anti-MT1-MMP or anti-b-catenin antibodies (data not shown). We also examined the interaction between MT1-MMP and β-catenin when MT1-MMP was co-transfected with β-catenin in MDCK cells. The results were the same as above (data not shown). However, we could not detect the obvious interaction between MP1-MMP and β-catenin in HT1080 cells, i.e., β-catenin was not readily immunoprecipitated by the antibody against MT1-MMP (fig. 2B). Likewise, MT1-MMP proteins were not detected in the protein complex immunoprecipitated by the anti-β-catenin antibody (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. β-catenin interacts with MT1-MMP in MDCK cells but not in HT1080 cells.

MDCK cells were only transfected with MT1-MMP, whereas HT-1080 cells were just transfected with β-catenin; and then cells cultured in the full medium containing 0.5µM GM6001. At 48 h after transfection, cells were collected and lysed in IP buffer. Cell lysates were subjected to co-immunoprecipitation with an anti-MT1-MMP antibody (A and B, left panels) or an anti-β-catenin antibody (A and B, right panels) or nonspecific IgG. Immunoprecipitated proteins were analysed by western blot using antibodies as indicated.

Protein interactions can also be tested by immunostaining using Confocal Microscopy. Our confocal results of MDCK cells transfected with MT1-MMP or co-transfected MT1-MMP with β-catenin showed that MT1-MMP co-localized predominately with β-catenin in granular arrays in the cytoplasm, with no localization in the nucleus (fig.3A). But in HT1080 cells, we found that co-localization between β-catenin and MT1-MMP proteins was not detectable, and most β-catenin was in nuclei (fig. 3B). These data suggest that β-catenin interacts/associates directly with MT1-MMP in the cytoplasm of MDCK cells, but not HT1080 cells. The association of β-catenin with MT1-MMP was different in MDCK and HT1080 cells due to the differential sub-cellular location of β-catenin in these cells as described in figure 1.

Figure 3. β-catenin co-localized with MT1-MMP in the cytoplasm in MDCK, but not in HT1080 cells.

(A) MDCK cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1, MT1-MMP or co-transfected with MT1-MMP and β-catenin; and (B) HT1080 cells were transfected pcDNA3.1 or β-catenin only. Transfected cells were cultured in the full medium containing 0.5µM GM6001 in 24-well plate with glass slide. At 48h after transfection, immunofluorescence chemistry experiments were performed using the anti-MT1-MMP antibody (green) and/or anti-β-catenin antibody (red) to detect cells expressing MT1-MMP and/or β-catenin, and to detect the co-localization of MT1-MMP and β-catenin or not.

Effect of β-catenin on the transcription of MT1-MMP gene

Previous reports have shown β-catenin can enhance the activity and function of MT1-MMP via elevating its transcription and protein expression in cancer cells (Nawrocki-Raby et al, 2003; Takahashi et al, 2002). From our data, when β-catenin was over expressed in HT1080 cells by transfection, the MT1-MMP mRNA level was increased (fig 4A), as well as the cell surface activity of MT1-MMP (fig.1D). However, in MDCK cells, the mRNA levels of MT1-MMP did not change upon transfection with β-catenin, either in parental MDCK cells (fig 4B) or in stable MT1-MMP transfected MDCK cells (fig 4C). These data demonstrated that β-catenin can regulate the transcription level of MT1-MMP in HT1080 cells, but not in MDCK cells. These results further indicated that the regulation of MT1-MMP activity by β-catenin in MDCK cells was via protein-protein interactions, not on transcriptional expression.

Figure 4. Effects of β-catenin on the transcription of MT1-MMP in MDCK cells and HT1080 cells.

(A) HT1080 cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1 or β-catenin; and then cells cultured in the full medium containing 0.5µM GM6001. At 48h after transfection, RT-PCR experiment was performed by harvesting one dish cells and the PCR products were detected by running 0.8% agarose gel. (B) & (C) MDCK cells and MDCK/MT1-MMP stable cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1 or β-catenin and then did the RT-PCR experiment as the HT1080 cells described above to detect the changes of mRNA level of MT1-MMP.

Effects of β-catenin on cell proliferation, growth and migration via MT1-MMP

It was reported that MT1-MMP can up-regulate cancer cell proliferation via the ERK signaling pathway (Gingras et al, 2001; Sounni et al, 2009; D'Alessio et al, 2008). Here we assayed the effect of β-catenin on proliferation of MDCK and HT1080 cells by using the Trypan Blue (fig.5A) and MTT methods (fig.5B). From our data, we found that MT1-MMP can stimulate cell proliferation in both MDCK and HT1080 cells, whereas β-catenin only increased proliferation in HT1080 cells. When co-transfecting HT1080 cells with MT1-MMP and β-catenin, the degree of cell proliferation was greater than MT1-MMP or β-catenin alone was transfected. There was no change in the rate of cell proliferation in MDCK cells when β-catenin was transfected alone or with MT1-MMP (fig.5).

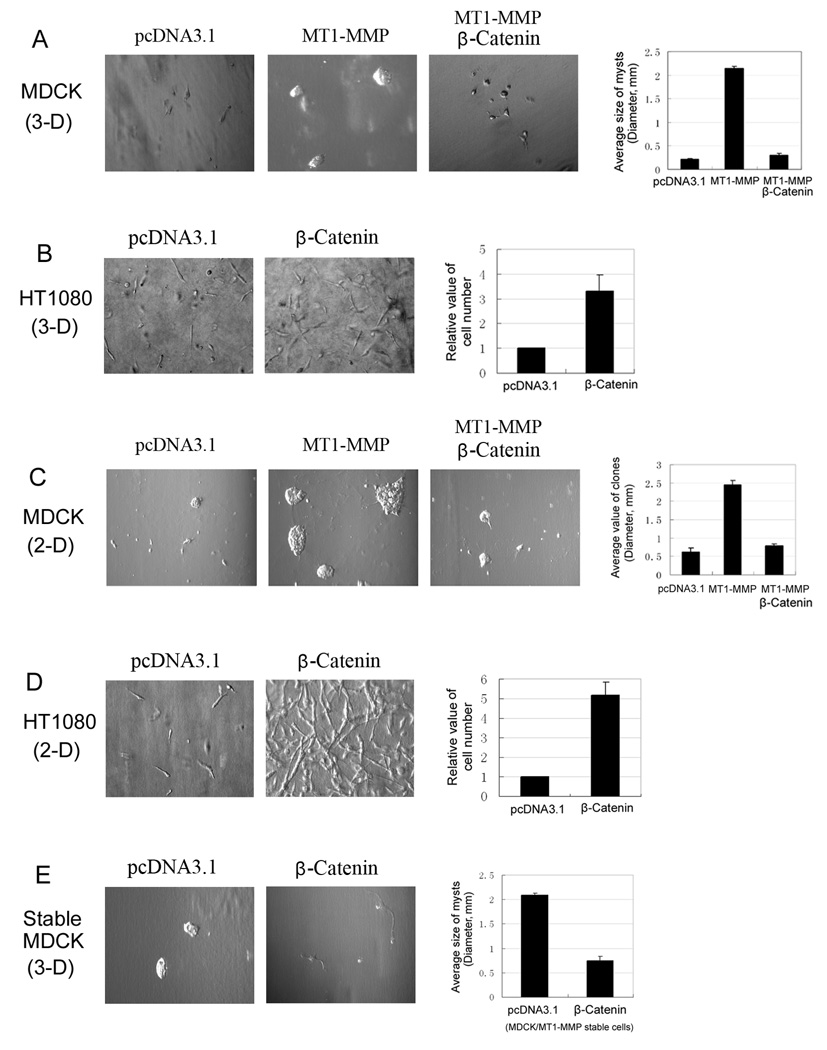

MT1-MMP plays a key role in cell growth in type I collagen gels and in cell migration (Seiki, 2002/2003; Hiraoka et al, 1998; Zhou et al, 2000). From our data above, β-catenin can inhibit the activities of MT1-MMP in MDCK cells, so it should subsequently reduce the enhancement of MT1-MMP on cell growth and cell migration. To study these points, we did cell growth and cell migration experiments. For MDCK cells, we found that transfected MT1-MMP can enhance cell growth in 3-D type I collagen gels and on 2-D type I collagen gels (Fig 6A and 6C). This affect was consistent with our previous reports (Pei and Weiss, 1996; Jiang et al, 2001). However, the enhancement of cell growth by MT1-MMP was blocked by co-transfecting β-catenin (fig 6A and 6C). In the MDCK/MT1-MMP stable cell line, the effects of β-catenin on the MT1-MMP enhanced cell growth were the same as in MT1-MMP transiently transfected MDCK cells (fig.6E). However, in HT1080 cells, cell growth was enhanced either in 3-D type I collagen gels or on 2-D type I collagen gels after transfection with β-catenin (fig 6B and 6D).

Figure 6. Effects of β-catenin on the growth of MDCK and HT1080 cells via the activity of MT1-MMP in 3-D collagen gel and on 2-D collagen gel.

(A) MDCK cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1, MT1-MMP or co-transfected MT1-MMP and β-catenin; and then cultured in six-well plate with full media. 24h later, cells were trypsined and equal amount cells (1×103) of each transfection were mixed with type I collagen (2.5mg/ml), and then cultured in the incubator in 24-well plates. After 7 days, the mysts grown from cells in three-dimensional type I collagen gel were photographed; and the average size of mysts (N=10) from each of three groups was evaluated statistically. (B) HT1080 cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1 or β-catenin and cultured in full media; and then treated the same as MDCK cells described above. (C) and (D) the transfections of MDCK and HT1080 cells were the same as above. 24h after cultured in 6-well plate, cells were trypsined and equal amount cells of each transfection were seeded and cultured on the surface of type I collagen gels (2.5mg/ml). One week later, the cells on the surface of two-dimensional type I collagen gel were photographed; the statistics value was done as above. (E) MDCK/MT1-MMP stable cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1 or β-catenin only; and then cells were performed in three-dimensional type I collagen as described above.

The effect of β-catenin on the role of MT1-MMP in cell migration was also examined. In confluent monolayer cell wound assays, MDCK cells tranfected with MT1-MMP migrated at a greater rate than control cells transfected with pcDNA3.1 vector or in cells co-transfected with β-catenin and MT1-MMP. Thus, cell migration enhanced by MT1-MMP in MDCK cells was inhibited by β-catenin (fig.7A). Enhanced migration of MDCK/MT1-MMP stable cells was also decreased by transfection of β-catenin (fig.7A). In HT1080 cells, the response to β-catenin was reversed, i.s., control cells transfected with pcDNA3.1 vector can migrate into the scratch, but the number of cells migrating into the scratch was increased after transfection with β-catenin (fig.7B).

Figure 7. Regulation of functions of MT1-MMP by β-catenin in the cell migration.

(A) MDCK and MDCK/MT1-MMP stable cells were transfected as indicated and cultured in 6-well plate with full media. After cells grew to 90% conference, cell migration assays were performed by using a scratch wound assay method as described in materials and methods. The scratch wounds and the migration cells in the scratch were photographed at 48h after scratching. (B) HT1080 cells were also transfected as indicated in figures. After transfection, cells were performed as above. The migration cells in the scratch were photographed at 24h and 48h after scratching, respectively.

These data indicated that β-catenin can greatly decrease the enhancement of MT1-MMP on cell proliferation, cell migration and cell growth in 3-D and 2-D collagen gels by interacting with MT1-MMP in non-cancer cells. However, the effects of β-catenin enhanced the function of MT1-MMP in tumor cells, probably via the Wnt pathway.

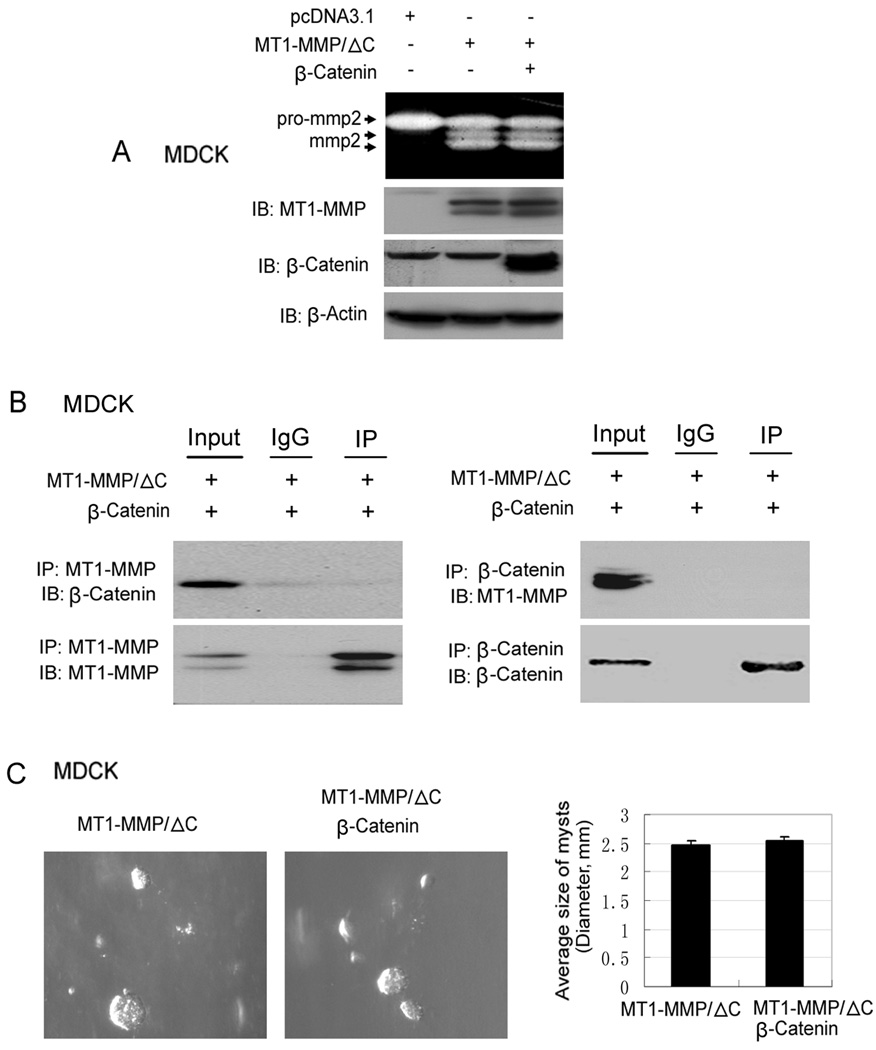

Cytoplasmic tail of MT1-MMP may be responsible for effect of β-catenin on MT1-MMP

Previous reports have shown that the cytoplasmic tail domain of MT1-MMP (C-terminal) plays an important role in the regulation and trafficking of MT1-MMP (Wang et al, 2004; Nyalendo et al, 2007; Jiang et al, 2001). Here we used the cytoplasmic tail domain deletion mutant of MT1-MMP (MT1-MMP/ΔC) to test if the C-terminal tail is a key domain of the MT1-MMP protein in the interaction effect of β-catenin on the activity of MT1-MMP in non-cancer cells. Our data show that the activity of MT1-MMP/ΔC was not affected by β-catenin when co-transfected with MT1-MMP/ΔC in MDCK cells (fig.8A). In addition, in MT1-MMP/ΔC and β-catenin co-transfected MDCK cells, β-catenin or MT1-MMP/ΔC could not be detected in the immunoprecipitated protein complex using either an anti-MT1-MMP antibody or anti-β-catenin antibody (fig.8B). Furthermore, in MDCK cells, there was no difference detected in the average size of mysts of cells grown in 3-D type I collagen gels after transfection with MT1-MMP/ΔC or co-transfection of MT1-MMP/ΔC with β-catenin (fig.8C). This is in contrast to the reduction in mysts size of MDCK cells expressing wild type MT1-MMP in 3D collagen gels (Fig.6A). Taken together, these results indicated that the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain of MT1-MMP protein plays a critical role in the interaction/association between β-catenin and MT1-MMP, and thus affects the regulation of MT1-MMP activity by β-catenin in non-cancer cells.

Figure 8. Effects of C-terminal cytoplasmic domain of MT1-MMP on the regulation of the activity of MT1-MMP by β-catenin.

(A) MDCK cells were transfected as indicated. After transfection, cells were cultured in 24-well plate with 5% FBS media. 48h later, media were harvested for zymography gel assay and cells were lysed for Western blotting assay. (B) MDCK cells were co-transfected with MT1-MMP/ΔC and β-catenin, and then cells cultured in the full medium containing 0.5µM GM6001. At 48h after transfection, cells were collected and lysed in IP buffer. Cell lysates were subjected to IP and Western blotting as above. (C) MDCK cells were transfected as indicated; and then cells were cultured in six-well plate. 24h later, cells were trypsined and equal amount cells (1×103) of each transfection were mixed with type I collagen (2.5mg/ml), and then cultured in the incubator in 24-well plate. After 7 days, the cells in three-dimensional type I collagen gel were photographed.

Wnt-3a pathway and E-cadherin involved in the effect of β-catenin on MT1-MMP

β-catenin in the Wnt-3a/β-catenin/Tcf-4 and E-cadherin/β-catenin pathways plays a critical role and participates in the regulation of gene transcription and protein expression through the transcription factor Tcf-4 (Novak and Dedhar, 1999; Takemaru et al, 2008). In view of the role proposed for Wnt-3a and E-cadherin in β-catenin regulation of MT1-MMP expression and function, it behooved us to examine the effects of Wnt-3a and E-cadherin in our cell models. We blocked Wnt-3a or E-cadherin expression by using siRNA methods. In MDCK cells, the inhibition of MT1-MMP activity by β-catenin was increased by blocking E-cadherin expression (fig.9A); but no change by blocking Wnt-3a expression (data not shown). As described above, the effect of β-catenin on MT1-MMP in HT1080 cells was opposite to its effects in MDCK cells. After blocking Wnt-3a expression in HT1080 cells, the enhancement of MT1-MMP activity by β-catenin was decreased (fig.9B(a)); and there was little change in MT1-MMP activity upon blocking E-cadherin expression (data not shown). Also in HT1080 cells, MT1-MMP activity was increased either by transfectd Wnt-3a or co-transfected Wnt-3a and β-catenin (fig.9B(b)). These results indicated that E-cadherin was involved in regulation of MT1-MMP by β-catenin in non-cancer MDCK cells and Wnt-3a participated in the effect of β-catenin on the activity of MT1-MMP in cancer HT1080 cells.

Figure 9. Effects of Wnt-3a and E-cadherin on the regulation of the activity of MT1-MMP by β-catenin.

(A) and (B) MDCK and HT1080 cells were transfected with plasmids and siRNAs of Wnt-3a and E-cadherin as indicated in figures, and then cells were cultured in media with 5% FBS. After 48h (for 8B (b)) and 72h (for 8A and 8B (a)), media were for zymography gel assay and cells cultured by medium containing 0.5µM GM6001 were lysed for Western blotting assay.

DISCUSSION

Our studies show a distinction in subcellular distribution of β-catenin in cancer and non-cancer cells, the former exhibiting nuclear β-catenin whereas the latter did not. The nuclear β-catenin in HT1080 cells was associated with Wnt/Tcf-4 activation of MT1-MMP transcription and elevated protein levels. On the other hand, in our novel discovery, cytoplasmic β-catenin was found to bind MT1-MMP, the binding of which required the 18-amino acid cytoplasmic domain of MT1-MMP.

Transcriptional regulation of the MT1-MMP gene has been described as a result of β-catenin entering the nucleus, binding to the transcription factor Tcf-4/Lef, and enhancing transcription of the MT1-MMP gene, thus regulating its mRNA and protein levels (Nawrochi-Raby et al., 2003; Takahashi et al., 2002). Our results show that β-catenin in the non-cancer MDCK cell model is in the cytoplasm and can inhibit the activity of MT1-MMP through direct interaction/association with this protein (fig.1 and fig.2A). MDCK cells had little or no endogenous MT1-MMP expression (fig. 1B), and the activity of exogenous MT1-MMP in MDCK cells was inhibited by co-transfected β-catenin as compared with cells transfected with MT1-MMP alone (fig 1C). However, in HT-1080 cancer cells, endogenous MT1-MMP activities were not decreased, but increased somewhat with transfection of β-catenin (fig. 1D). Wnt-3a protein is known to be aberrantly activated and expressed at greater levels in many cancer cells, but is at lower levels or inactivated in mature normal or non-cancer cells (Jia et al., 2008; Stemmler, 2008). Thus in the HT-1080 cells, Wnt-3a and the Wnt-3a/β-catenin/Tcf-4 pathway were highly activated, resulting in most of the β-catenin protein expressed entering the nucleus (fig. 1B and fig. 3B), enhancing the activity of the transcription complex CBP/β-catenin/Tcf-4 and thus increasing transcription, protein level and activities of MT1-MMP. These results support the concept that regulation of MT1-MMP activity by β-catenin in cancer cells occurred not by interaction in the cytoplasm, but via the Wnt/β-catenin/Tcf-4 pathway in the nucleus. In addition, the effect of β-catenin on MDCK and HT1080 cell proliferation was also different via different affecting the activity of MT1-MMP which can mediate the activation of ERK pathway (fig.5).

In normal/non-cancer cells, the Wnt-3a/β-catenin/Tcf-4 pathway is not activated and β-catenin is located in two main populations in the cytoplasm: bound to E-cadherin and as free β-catenin (Novak and Dedhar, 1999). Up to now many studies on β-catenin have focused on functions of nuclear β-catenin in cancer cells, and the possible functions of “free” β-catenin in the cytoplasm has received little attention. The dynamic balance of β-catenin between the two cytoplasmic pools (Novak and Dedhar, 1999; Takemaru et al, 2008) would indicate that binding with E-cadherin should affect the level and function of β-catenin. Here we not only found that E-cadherin could reduce the inhibition of MT1-MMP activity by β-catenin (fig.9A), but that β-catenin in the cytoplasm in non-cancer cells could inhibit the cell surface activity of MT1-MMP by direct interaction/association with it. However, the interaction of β-catenin and MT1-MMP could have regulatory effects beyond blocking its transfer to the cell surface. For example, adherens junctions undergo continual turnover under normal circumstances (Wirtz-Peitz and Zallen, 2009), and MT1-MMP can cleave cadherins in NRK-52E cells under ischemic conditions (Covington et al., 2006). Thus it is possible binding of MT1-MMP by β-catenin could position MT1-MMP in apposition to potential intracellular substrate proteins, giving it a subtle role in adherens junction remodeling and under certain conditions lead to cleavage of the cadherin or other substrates. However, it does not appear MT1-MMP and β-catenin complexes were part of adherent junctions since E-cadherin was not detected in the immunoprecipitates with anti-MT1-MMP or anti-β-catenin antibodies. Although there was a small amount of β-catenin protein in the cytoplasm of HT-1080 cells (fig.1B), there was no detectable binding interaction/association between β-catenin and MT1-MMP as evidenced by immunoprecipitation experiments.

The short 18-amino acid C-terminal cytoplasmic domain of MT1-MMP is very important in regulation of the activity and function of MT1-MMP, including trafficking of MT1-MMP from the cytoplasm to the plasma membrane (Wang et al., 2004), regulation of MT1-MMP activity by Src (Nyalendo et al., 2007), activation of ERK and cell proliferation via binding of TIMP2 (D’Alessio et al,2008), and the effect of ConA and dynamin on the activity of MT1-MMP (Jiang et al., 2001). Here in MDCK cells, β-catenin was found to bind MT1-MMP and this interaction resulted in accumulation of MT1-MMP and β-catenin in the cytoplasm and then decreased activities of exogenous MT1-MMP on the cell surface as evidenced by decreased proMMP-2 activation. In contrast, the transfected MT1-MMP/ΔC mutant without the 18-amino acid cytoplasmic domain did not bind with β-catenin, nor was its cell surface activity inhibited by co-transfection of β-catenin (fig.8). This indicates that the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain of MT1-MMP was required for interaction with β-catenin, and perhaps to be involved in regulating the activity of MT1-MMP. β-catenin has numerous binding partners, many of which are nuclear proteins (Le et al., 2008). β-catenin binds with different proteins at different sites in its central armadillo 12-repeat groove domain or its N-terminal domain (Xu and Kimelman, 2007). Although the binding parameters of β-catenin with MT1-MMP have not been determined, the 18-amino acid cytoplasmic domain of MT1-MMP is critical for this interaction to occur. This also emphasizes that the subcellular spatial segregation of different β-catenin binding partners are important for the function of these proteins (Xu and Kimelman, 2007) and for MT1-MMP this may affect association with specific substrate proteins and transport and positioning of this protease in the plasma membrane.

In summary, there is substantial evidence in the literature for the role of β-catenin as an important co-transcription factor in the nucleus in many developmental and pathological conditions, including cancer (Fu et al, 2008; Novak and Dedhar, 1999; Takemaru et al, 2008). This transcriptional activating role via binding with Tcf-4/Lef leads to increased transcription of MT1-MMP, which can facilitate growth, differentiation and migration of cancer cells. However, the most novel finding here is that cytoplasmic β-catenin of normal/non-cancer cells can directly interact/associate with MT1-MMP and inhibit its translocation to the cell surface and its resultant proteolytic activity. This implies β-catenin may have a regulatory role in the subcellular spatial segregation of MT1-MMP, which may include blocking its transport to the plasma membrane or positioning MT1-MMP in apposition to select intracellular substrate proteins and thus regulate their proteolysis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

*We would like to give our thanks to Cynthia L Croy (Department of Pharmacology, University of Minnesota) for technical assistance and research discussion.

Grant information: NIH Grant. Contract grant sponsor: Michael J. Wilson; Contract grant number: CA114418-01A2.

REFERENCES

- Bachis A, Mallei A, Cruz MI, Wellstein A, Mocchetti I. Chronic antidepressant treatments increase basic fibroblast growth factor and fibroblast growth factor-binding protein in neurons. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:1114–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth AI, Nathke IS, Nelson WJ. Cadherins, catenins and APC protein: interplay between cytoskeletal complexes and signaling pathways. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1997;9:683–690. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80122-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigg HF, Morrison CJ, Butler GS, Bogoyevitch MA, Wang Z, Soloway PD, Overall CM. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-4 inhibits but does not support the activation of gelatinase A via efficient inhibition of membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3610–3618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo-Cordero JJ, Marrero-Diaz R, Megías D, Genís L, García-Grande A, García MA, Arroyo AG, Montoya MC. MT1-MMP proinvasive activity is regulated by a novel Rab8-dependent exocytic pathway. EMBO J. 2007;26:1499–1510. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown PD, Levy AT, Margulies IM, Liotta LA, Stetler-Stevenson WG. Independent expression and cellular processing of Mr 72,000 type IV collagenase and interstitial collagenase in human tumorigenic cell lines. Cancer Res. 1990;50:6184–6191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colangelo AM, Johnson PF, Mocchetti I. beta-adrenergic receptor-induced activation of nerve growth factor gene transcription in rat cerebral cortex involves CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein delta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10920–10925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington MD, Burghardt RC, Parrish AR. Ischemia-induced cleavage of cadherins in NRK cells requires MT1-MMP (MMP-14) Am J Renal Physiol. 2006;290:F43–F51. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00179.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Alessio S, Ferrari G, Cinnante K, Scheerer W, Galloway AC, Roses DF, Rozanov DV, Remacle AG, Oh ES, Shiryaev SA, Strongin AY, Pintucci G, Mignatti P. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2 binding to membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase induces MAPK activation and cell growth by a non-proteolytic mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:87–99. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705492200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’Ortho MP, Will H, Atkinson S, Butler G, Messent A, Gavrilovic J, Smith B, Timpl R, Zardi L, Murphy G. Membrane-type matrix metalloproteinases 1 and 2 exhibit broad-spectrum proteolytic capacities comparable to many matrix metalloproteinases. Eur J Biochem. 1997;250:751–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu AK, Cheung ZH, Ip NY. Beta-catenin in reverse action. Nat Neuroscience. 2008;11:244–246. doi: 10.1038/nn0308-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gálvez BG, Matías-Román S, Yáñez-Mó M, Vicente-Manzanares M, Sánchez-Madrid F, Arroyo AG. Caveolae are a novel pathway for membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase traffic in human endothelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:678–687. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-07-0516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingras D, Bousquet-Gagnon N, Langlois S, Lachambre MP, Annabi B, Be¨liveau R. Activation of the extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) cascade by membrane-type-1 matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) FEBS Letters. 2001;507:231–236. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumbiner BM. Lateral clustering of the adhesive ectodomain: a fundamental determinant of cadherin function. Curr. Biol. 1997;7:R443–R446. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00154-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraoka N, Allen E, Apel IJ, Gyetko MR, Weiss SJ. Matrix metalloproteinases regulate neovascularization by acting as pericellular fibrinolysins. Cell. 1998;95:365–377. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81768-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hlubek F, Spaderna S, Jung A, Kirchner T, Brabletz T. Beta-catenin activates a coordinated expression of the proinvasive factors laminin-5 gamma2 chain and MT1-MMP in colorectal carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:321–326. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotary K, Allen E, Punturieri A, Yana I, Weiss SJ. Regulation of cell invasion and morphogenesis in a three-dimensional type I collagen matrix by membrane-type matrix metalloproteinases 1, 2, and 3. J. Cell Biol. 2000;149:1309–1323. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.6.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh Y, Takamura A, Ito N, Maru Y, Sato H, Suenaga N, Aoki T, Seiki M. Homophilic complex formation of MT1-MMP facilitates proMMP-2 activation on the cell surface and promotes tumor cell invasion. EMBO J. 2001;20:4782–4793. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L, Miao C, Cao Y, Duan EK. Effects of Wnt proteins on cell proliferation and apoptosis in HEK293 cells. Cell Biol Int. 2008;32:807–813. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang A, Pei D. Distinct roles of catalytic and pexin-like domains in membrane-type matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-mediated pro-MMP-2 activation and collagenolysis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38765–38771. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306618200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang A, Lehti K, Wang X, Weiss SJ, Keski-Oja J, Pei D. Regulation of membrane-type matrix metalloproteinase 1 activity by dynamin-mediated endocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13693–13698. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241293698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang T, Yi J, Yang W, Wang X, Jiang A, Pei D. Functional characterization of MT3-MMP in transfected MDCK cells: progelatinase A activation and tubulogenesis in 3-D collagen lattice. FASEB J. 2000;14:2559–2568. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0269com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshikawa N, Giannelli G, Cirulli V, Miyazaki K, Quaranta V. Role of cell surface metalloprotease MT1-MMP in epithelial cell migration over laminin-5. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:615–624. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.3.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehti K, Lohi J, Juntunen MM, Pei D, Keski-Oja J. Oligomerization through hemopexin and cytoplasmic domains regulates the activity and turnover of membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:8440–8448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109128200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le NH, Franken P, Fodde R. Tumour-stroma interactions in colorectal cancer: converging on β-catenin activation and cancer stemness. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:1886–1893. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Aoki T, Mori Y, Ahmad M, Miyamori H, Takino T, Sato H. Cleavage of lumican by membrane-type matrix metalloproteinase-1 abrogates this proteoglycan-mediated suppression of tumor cell colony formation in soft agar. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7058–7064. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercure MZ, Ginnan R, Singer HA. CaM kinase II delta2-dependent regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell polarization and migration. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294:C1465–C1475. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.90638.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JR, Moon RT. The axis-inducing activity, stability, and subcellular distribution of beta-catenin is regulated in Xenopus embryos by glycogen synthase kinase 3. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2527–2539. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.12.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawrocki-Raby B, Gilles C, Polette M, Martinella-Catusse C, Bonnet N, Puchelle E, Foidart JM, Van Roy F, Birembaut P. E-Cadherin mediates MMP down-regulation in highly invasive bronchial tumor cells. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:653–661. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63692-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak A, Dedhar S. Signaling through beta-catenin and Lef/Tcf. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;56:523–537. doi: 10.1007/s000180050449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyalendo C, Michaud M, Beaulieu E, Roghi C, Murphy G, Gingras D, Béliveau R. Src-dependent phosphorylation of membrane type I matrix metalloproteinase on cytoplasmic tyrosine 573: role in endothelial and tumor cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:15690–15699. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608045200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohuchi E, Imai K, Fujii Y, Sato H, Seiki M, Okada Y. Membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase digests interstitial collagens and other extracellular matrix macromolecules. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:2446–2451. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overall CM, Lopez-Otin C. Strategies for MMP inhibition in cancer: innovations for the post-trial era. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:657–672. doi: 10.1038/nrc884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei D, Weiss SJ. Transmembrane-deletion mutants of the membrane-type matrix metalloproteinase-1 process progelatinase A and express intrinsic matrix-degrading activity. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:9135–9140. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.9135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei D. Identification and characterization of the fifth membrane-type matrix metalloproteinase MT5-MMP. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8925–8932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polakis P. The adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) tumor suppressor. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1997;1332:F127–F147. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(97)00008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remacle A, Murphy G, Roghi C. Membrane type I-matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) is internalised by two different pathways and is recycled to the cell surface. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:3905–3916. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiki M. The cell surface: the stage for matrix metalloproteinase regulation of migration. Curr. Opin. Cell. Biol. 2002;14:624–632. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00363-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiki M. Membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase: a key enzyme for tumor invasion. Cancer Lett. 2003;194:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00699-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sounni NE, Rozanov1 DV, Remacle1 AG, Golubkov1 VS, Noel A, Strongin AY. Timp-2 binding with cellular MT1-MMP stimulates invasionpromoting MEK/ERK signaling in cancer cells. Int. J. Cancer. 2010;126:1067–1078. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetler-Stevenson WG, Liotta LA, Kleiner JDE. Extracellular matrix 6: role of matrix metalloproteinases in tumor invasion and metastasis. FASEB J. 1993;7:14334–11441. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.15.8262328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stemmler MP. Cadherins in development and cancer. Mol Biosyst. 2008;4:835–850. doi: 10.1039/b719215k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M, Tsunoda T, Seiki M, Nakamura Y, Furukawa Y. Identification of membrane-type matrix metalloproteinase-1 as a target of the beta-catenin/Tcf4 complex in human colorectal cancers. Oncogene. 2002;21:5861–5867. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemaru KI, Ohmitsu M, Li FQ. An oncogenic hub: beta-catenin as a molecular target for cancer therapeutics. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008;186:261–284. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-72843-6_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uekita T, Itoh Y, Yana I, Ohno H, Seiki M. Cytoplasmic tail-dependent internalization of membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase is important for its invasion-promoting activity. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:1345–1356. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Nie J, Pei D. Mint-3 regulates the retrieval of the internalized membrane-type matrix metalloproteinase, MT5-MMP, to the plasma membrane by binding to its carboxyl end motif EWV. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51148–51155. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400264200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Ma D, Keski-Oja J, Pei D. Co-recycling of MT1-MMP and MT3-MMP through the trans-Golgi network. Identification of DKV582 as a recycling signal. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:9331–9336. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312369200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Will H, Atkinson SJ, Butler GS, Smith B, Murphy G. The soluble catalytic domain of membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase cleaves the propeptide of progelatinase A and initiates autoproteolytic activation. Regulation by TIMP-2 and TIMP-3. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17119–17123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijnhoven BP, Dinjens WNM, Pignatelli M. E-cadherin-catenin cell-cell adhesion complex and human cancer. Br J Surg. 2000;87:992–1005. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz-Peitz F, Zallen JA. Junctional trafficking and epithelial morphogenesis. Curr Opinion Gen Dev. 2009;19:350–356. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Kimelman D. Mechanistic insights from structural studies of β-catenin and its binding partners. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:3337–3334. doi: 10.1242/jcs.013771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Apte SS, Soininen R, Cao R, Baaklini GY, Rauser RW, Wang J, Cao Y, Tryggvason K. Impaired endochondral ossification and angiogenesis in mice deficient in membrane-type matrix metalloproteinase I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:4052–4057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060037197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]