Abstract

D-Amphetamine (AMPH) downregulates the norepinephrine (NE) transporter (NET), although the exact trafficking pathways altered and motifs involved are not known. Therefore, we examined the cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in AMPH-induced NET regulation in human placental trophoblast (HTR) cells expressing the wild-type (WT)-hNET and the hNET double mutant (hNET-DM) bearing protein kinase C (PKC) resistant T258A+S259A motif. NET function and surface expression were significantly reduced in cells expressing WT-hNET but not in cells expressing hNET-DM following AMPH treatment. AMPH inhibited plasma membrane recycling of both WT-hNET and hNET-DM. In contrast, AMPH stimulated endocytosis of WT-hNET, and did not affect hNET-DM endocytosis. While PKC or calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase-II (CaMKII) inhibition or depletion of calcium failed to block AMPH-mediated downregulation of WT-hNET, NET-specific blocker desipramine (DMI) completely prevented AMPH-induced downregulation. Furthermore, AMPH treatment had no effect on phospho-CaMKII immunoreactivity. The inhibitory potency of AMPH was highest on hNET-DM, intermediary on T258A and S259A single mutants and lowest on WT-hNET. Single mutants exhibited partial resistance to AMPH-mediated downregulation. AMPH accumulation was similar in cells expressing WT-hNET or hNET-DM. The results demonstrate that reduced plasma membrane insertion and enhanced endocytosis account for AMPH-mediated NET downregulation, and provide the first evidence that T258/S259 motif is involved only in AMPH-induced NET endocytosis that is DMI-sensitive, but PKC and CaMKII independent.

Keywords: NE transport, norepinephrine transporter (NET), D-amphetamine (AMPH), PKC, endocytosis, desipramine

INTRODUCTION

NET is a critical mediator of NE inactivation and presynaptic catecholamine homeostasis (Iversen 1971; Schomig et al. 1989; Trendelenburg 1991). NET knockout mice exhibit diminished NE clearance, elevated extracellular NE levels, reduced tissue NE concentrations, and altered dopamine (DA) signaling (Xu et al. 2000; Keller et al. 2004). NET expressed both in the CNS and periphery is an important target for tricyclic antidepressants, NET-selective reuptake inhibitors, and psychostimulants, including cocaine, methylphenidate and AMPH (Tatsumi et al. 1997). Topological predictions indicate that NET and its homologs possess 12 transmembrane domains with NH2 and COOH termini located intracellularly. Recently reported high-resolution structure of LeuT (Yamashita et al. 2005), a prokaryotic sodium-dependent leucine transporter with significant homology to NET and related neurotransmitter transporters supports this 12 transmembrane domains topology. Cocaine and other AMPH-like psychostimulants target monoamine transporters and this action is well recognized as a primary contributor in the addictive properties of these drugs (Robinson and Berridge 1993; Markou et al. 1998).

AMPH inhibits NE uptake in HEK 293 cells expressing hNET and nisoxetine binding sites are reduced following AMPH exposure (Zhu et al. 2000). A recent study by Dipace et al demonstrated a link between AMPH induced reductions in cell surface NET levels and increased NET-syntaxin 1A (SYN1A) interaction at the plasma membrane (Dipace et al. 2007). NET directly interacts with SYN1A and that the interaction occurs between the cytoplasmic domain of SYN1A and the NH2 terminus of NET (Sung et al. 2003). To date, studies have not yet addressed the effects of psychostimulant drugs on NET trafficking mechanisms exocytosis and endocytosis, which would ultimately determine the levels of transporter on the plasma membrane and hence NE transport capacity.

Our recent studies demonstrated that PKC activation stimulates NET internalization (Jayanthi et al. 2004) and identified a trafficking motif involved in PKC-mediated NET downregulation and established a close link between transporter phosphorylation and transporter internalization (Jayanthi et al. 2006). Having known that both PKC activation and AMPH downregulate NET functional expression, in the present study, we took advantage of PKC-resistant hNET-DM to explore the trafficking and signaling mechanisms involved in AMPH-induced NET downregulation. We demonstrate that in HTR cells, AMPH downregulates WT-hNET by a cumulative effect of inhibiting transporter insertion into the plasma membrane and stimulating endocytosis. Intriguingly, the PKC-insensitive hNET-DM was resistant to AMPH-induced NET endocytosis. NET-specific blocker DMI, but not the inhibition of PKC or CaMKII or depletion of Ca2+ prevented AMPH-induced NET downregulation. These results indicate that AMPH-induced transporter regulation is PKC-independent regardless of the involvement of common T258/S259 motif.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Human placental trophoblast (HTR) cell line was a kind gift from Dr. Charles H. Graham, Queen’s University, Ontario, Canada. Mouse monoclonal antibody to hNET was from Monoclonal Antibody Technologies (Atlanta, GA). Anti-phospho-CaMKII antibody was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Mouse anti-TfR antibody was from Zymed Laboratories (South San Francisco, CA). Anticalnexin antibody was from Stressgen Biotechnologies (Victoria, BC, Canada). KN-62 and KN-93 were from Alexis Biochemicals (San Diego, CA). Cell permeable myristoylated-AIP (autocamtide-related inhibitory peptide) was from EMD Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA, USA). Other reagents were of the highest grade possible from standard sources such as Sigma and Pierce.

Cell culture, transfections and development of stable cell lines

HTR-hNET or HTR-hNET-DM cell lines expressing hNET or hNET-DM or T258A or S259A single mutants were generated following transfection of HTR cells with WT-hNET or hNET-DM or hNET-T258A or hNET-S259A cDNAs and selecting stable transformants in the presence of 5 μg/ml blasticidine (Jayanthi et al. 2006). Stable cells were cultured in a mixture of RPMI 1640 (Mediatech-Cellgro, Manassas, VA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, and penicillin (100 units/ml) - streptomycin (100 μg/ml) containing (1.0 μg/ml blasticidine). Cells seeded in 24-well cell culture plates (100 thousand cells/well) or 12-well plates (200 thousand cells/dish or well) were allowed to grow in an atmosphere of 95% air/5% CO2 for 48 hrs and used for the following experiments. To equalize expression levels of WT and DM NETs, HTR cells were transiently transfected with 0.5 or 1 μg of WT-hNET or 1 or 2 μg of hNET-DM per well in 24 or 12 well plates respectively using FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (Roche Diagnostics) and used for NE uptake, biotinylation and AMPH accumulation experiments.

Treatments and NE uptake assay

HTR-hNET or HTR-hNET-DM or HTR-hNET-T258A or HTR-hNET-S259A stable cells, NE uptake was measured in the presence of increasing concentrations of AMPH to calculate apparent inhibition constant (Ki) values. HTR-hNET or HTR-hNET-DM stable cells as well as HTR cells transiently transfected with 0.5 μg WT-hNET cDNA or 1 μg hNET-DM cDNA were treated with the vehicle or AMPH (10 μM) for 1, 5, 15 and 60 min at 37°C in 0.5 ml of Krebs-Ringer-HEPES (KRH) buffer pH 7.4 (120 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 2.2 mM CaCl2 10 mM HEPES, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 5 mM Tris, and 10 mM D- glucose) containing 100 μM ascorbic acid and 100 μM pargyline (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Prior to NE uptake initiation, AMPH was removed and cells were washed twice with 2 ml of KRH buffer. NE uptake measurements were performed by incubating the cells for 10 min at 37°C, with 50 nM [3H]-NE (35.0 Ci/mmol L-[7,8-3H] norepinephrine, GE healthcare, Chalfont, St. Giles, UK). Assays were terminated by removing the radiolabel and by rapid washings of cells three times with 1 ml ice-cold KRH buffer. Cells were solubilized in 0.5 ml 1% SDS and the accumulated [3H]-NE was quantified by liquid scintillation counting (Beckman Coulter Inc., Brea, CA, USA). Specific NE uptake was measured by subtracting the NE uptake measured in the presence of 10 μM desipramine (DMI) from the total NE uptake measured in the absence of DMI. Ki values were determined by nonlinear least-squares fits, using two-parameter logistic equations (Kaleidagraph, Synergy Software, Reading, PA): the percentage of specific NE transport remaining = 100/[1 + (IC50/[I])n]. The IC50 is the concentration of AMPH giving 50% inhibition, [I] is the AMPH concentration, and n is the slope (Hill coefficient). IC50 values were converted to Ki values by using the Cheng and Prusoff correction for substrate concentration (Cheng and Prusoff 1973). Data are represented as the means ± SEM of six independent measurements on three separate batches of cells.

AMPH uptake/accumulation assay

Intracellular accumulation of AMPH was measured by incubating HTR cells transfected with 0.5 μg WT-hNET cDNA or 1 μg hNET-DM cDNA for 10 min at 37°C with 10 nM [3H]D-AMPH (40 Ci/mmol Amphetamine, D [ring-2, 3, 5-3H] hydrochloride, American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc. St. Louis, MO) as described above for NE uptake assay. When used at 10 μM concentration, [3H]AMPH accumulation was measured with 10 nM [3H]AMPH and the rest substituting with nonradioactive AMPH. Intracellular accumulation of AMPH was also measured in HTR-hNET and HTR-hNET-DM stable cells using 10 μM AMPH.

Cell surface NET measurements by surface biotinylation

Cell surface biotinylation and immunoblot analyses were employed as described earlier (Jayanthi et al. 2004; Jayanthi et al. 2006) to quantify the amount of NET protein distributed between cell surface and intracellular pools. HTR cells transiently transfected with 1 μg WT-hNET cDNA or 2 μg hNET-DM cDNA or HTR-hNET and HTR-hNET-DM stable cells were treated with the reagents as described elsewhere. Following treatments, cells were quickly washed with ice-cold PBS/Ca-Mg and incubated with the cell membrane impermeable reagent, sulfo-NHS-Biotin (1.5 mg/ml, Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL) for 1hr at 4°C in PBS/Ca-Mg (138 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 1.5 mM KH2PO4, 9.6 mM Na2HPO4, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM CaCl2, pH 7.3). The biotinylating agent was removed by incubating twice with 100 mM glycine for 30 min. Cells were washed with PBS/Ca-Mg and lysed at 4°C with 700 μl RIPA buffer (10 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate), containing protease inhibitors. Lysates were centrifuged at 20,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. Protein concentrations of the supernatants were determined by DC protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). 400 μl of supernatant containing 1 μg protein/10 μl (total of 40 μg of protein) from each fraction were incubated with NeutrAvidin beads (Pierce) for 1 hr at room temperature. The beads were washed three times with RIPA buffer and adsorbed proteins were eluted in 50 μl Laemmli buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 20% glycerol, 2% SDS, 5% ß-mercaptoethanol and 0.01% bromophenol blue). An aliquot (40 μl) of total cell lysate from each sample and all (50 μl) of avidin bound samples were analyzed by immunoblotting with NET-specific antibody. To visualize intracellular NET, equal amounts (40 μl) of unbound fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting with NET-antibody. To validate equal loading and the surface localization of biotinylated NET protein, corresponding total and bound blots were stripped and reprobed with anticalnexin antibody. Band intensities were quantified using NIH ImageJ (v. 1.62). Exposures were precalibrated to insure quantitation within the linear range of the film and multiple exposures were taken to validate linearity of quantitation. Values of total, nonbiotinylated and surface NET proteins were normalized using levels of calnexin immunoreactivity in total cell extract and values averaged across three experiments.

Measurement of NET recycling/exocytosis to plasma membrane by surface biotinylation

NET insertion into the plasma membrane was measured as described before (Jayanthi et al. 2006). Cells were washed with PBS/Ca-Mg and incubated twice with 1 mg/ml sulfo-NHS-acetate (Pierce) in PBS/Ca-Mg for 1 hr at 4°C (trafficking nonpermissive condition) to block all the free amino groups (Lee-Kwon et al. 2003). After washing away the sulfo-NHS-acetate with cold PBS/Ca-Mg, the cell membrane impermeable sulfo-NHS-Biotin (1 mg/ml) in PBS/Ca-Mg containing AMPH (10 μM) or the vehicle (prewarmed at 37°C) was added to the cells and incubated further for indicated time periods at 37°C (trafficking permissive condition). Biotinylated NETs inserted into the plasma membrane (surface) and nonbiotinylated (intracellular) NETs were analyzed as described above. Biotinylated transferrin receptor (TfR) was analyzed by stripping the blot followed by reprobing with TfR antibody. The accumulation of biotinylated NET or TfR at each time point was measured by quantifying the band densities using NIH ImageJ (v. 1.62).

Measurement of NET endocytosis by reversible biotinylation

Reversible biotinylation was performed as described (Jayanthi et al. 2006). HTR-hNET or HTR-hNET-DM cells were cooled rapidly to 4°C to inhibit endocytosis by washing with cold PBS and surface biotinylated with a disulfide-cleavable biotin (sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin; Pierce) and free biotinylating reagent was removed by quenching with glycine. NET endocytosis was initiated by incubating the cells with prewarmed media containing AMPH (10 μM) or the vehicle for indicated time periods at 37°C. At the end of incubations, the reagents were removed, and fresh pre-chilled media were added to stop the endocytosis. The cells were then washed and incubated twice with 250 μM sodium 2-mercapto-ethanesulfonate (MesNa, Sigma, St. Louis, MO), a reducing agent in PBS/Ca-Mg for 20 min at 4°C to dissociate the biotin from cell surface-resident proteins via disulfide exchange. To define total biotinylated NETs, one dish of biotinylated cells was not subjected to reduction with MesNa, and directly processed for extraction followed by isolation by avidin beads. To define MesNa-accessible NETs, another dish of cells was treated with MesNa immediately (at 0 time) following biotinylation at 4°C to reveal the quantity of surface NET biotinylation that MesNa can reverse efficiently. Following treatments, cells were solubilized in RIPA and biotinylated NET protein was separated from non-biotinylated proteins by using NeutrAvidin beads. Biotinylated proteins were eluted from beads and resolved by SDS-PAGE. NET proteins in the fractions were visualized with NET-specific antibody as described under “surface biotinylation” section. NET bands were scanned and the band densities were quantified by NIH ImageJ (v. 1.62) software.

RESULTS

hNET-DM is resistant to AMPH-mediated downregulation

Figure 1A shows that following thorough washings (2X times with KRH assay buffer), cells treated with 10 μM AMPH for 1, 5, 15, and 60 min produced a significant reduction in NE transport by HTR cells transiently or stably expressing WT-hNET (Fig. 1A & 1C). Nearly 20% inhibition was found following 5 min AMPH treatment reaching a maximum of 30% inhibition following 15 or 60 min treatments. In parallel experiments, NE transport by HTR cells transiently or stably expressing hNET-DM was not significantly altered by AMPH at all time points tested, and if at all, a small nonsignificant (10-15%) inhibition was observed following 5 and 15 min AMPH treatment (Fig. 1B & 1D). As can be noted from Figures 1C and 1D, NE uptake by HTR-hNET-DM cells is less compared to NE uptake by HTR-hNET cells due to reduced expression of hNET-DM (Fig. 2D). It is possible that the decreased NE uptake observed in WT-hNET following AMPH incubation and washing could arise as a result of exchange of intracellularly accumulated AMPH with extracellular NE. Therefore, biotinylation and immunoblotting experiments were performed to assess changes in surface NET following AMPH treatments and the results are presented in Fig. 2. Quantified band densities of biotinylated NET (85 kDa bands) expressed in percent of vehicle control or reduction in surface NET by AMPH in % are presented in the bar graphs (lower panels). As shown in Fig. 2, 5 min AMPH treatment of HTR cells transiently expressing WT-hNET or hNET-DM produced small non-significant reductions in the surface immunoreactivity of WT-hNET (Fig. 2A) and hNET-DM (Fig. 2B). Significant reductions in cell surface expression of WT-hNET but not that of hNET-DM were observed following 15 and 60 min AMPH treatments (Fig. 2A-2C). Quantified data in bottom panel show 20% and 50% reduction in cell surface levels of WT-hNET following 15 and 60 min AMPH treatment compared to respective vehicle treatments (Fig. 2A & 2C). Quantified data in bottom panel show nonsignificant reductions (5-10%) in cell surface levels of hNET-DM following 5 and 15 min AMPH treatment compared to respective vehicle treatment (Fig. 2A & 2B). 60 min AMPH treatment completely failed to alter surface levels of hNET-DM (Fig. 2C). The decreases in cell surface immunoreactivity paralleled with increases in intracellular NET levels (shown as inverted bars; Fig. 2A-2C). The results are relatively consistent with AMPH effect on NE transport. There were no significant changes in total NET protein levels following 5, 15 and 60 min AMPH treatment. When reprobed with anti-calnexin antibody, no differences in the calnexin levels were observed in the total fractions between treatments suggesting equal loading and transfer of proteins (Fig. 2A-2C), and also calnexin was not detected in the bound fractions suggesting no contamination with intracellular proteins (data not shown). Essentially similar results were obtained when HTR-hNET or HTR-hNET-DM stable cells were used (Fig 2D). Bar graphs show reductions in cell surface NET densities following AMPH treatment for 5, 15 and 60 min (Fig. 2D). Significant reductions (25% and 45%) in NET cell surface densities were seen only in HTR-hNET cells following 15 and 60 min AMPH treatments respectively (Fig 2D). It is important to note that at short AMPH treatment time points, small less significant decreases in cell surface hNET-DM (Fig. 2D) observed correlate with small less significant inhibition of NE transport by AMPH observed in HTR-hNET-DM cells (Fig. 1 D).

Figure 1. AMPH inhibits NE uptake by HTR cells expressing WT-hNET, but not the hNET-DM.

HTR cells transiently expressing WT-hNET or hNET-DM (A&B) or HTR-hNET or HTR-hNET-DM stable cells (C&D) were treated with 10 μM AMPH for 1, 5, 15 and 60 min at 37°C. Following treatments, cells were washed twice with transport assay buffer and NE uptake assays were performed as described under Materials and Methods section. To define specific NE transport via NETs, parallel uptake assays were carried out in the presence of 10 μM DMI. Data derived from three separate experiments, each in triplicate are given as mean ± S.E.M. *s indicate significant changes in NE transport following AMPH treatment compared to vehicle treatment (p < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test).

Figure 2. AMPH down-regulates cell surface expression of WT-hNET, but not hNET-DM.

HTR cells transiently expressing WT-hNET (A) or hNET-DM (B) were treated with vehicle or 10 μM AMPH for 5 and 15 min at 37°C. (C) HTR cells transiently expressing WT-hNET or hNET-DM were treated with vehicle or 10 μM AMPH for 60 min at 37°C. HTR-hNET or HTR-hNET-DM stable cells were treated with vehicle or 10 μM AMPH for 5, 15 and 60 min (D) at 37°C. Following treatments, cells were biotinylated with sulfo-NHS-biotin as described under Materials and Methods section. Equal aliquots from total (T) and avidin unbound fractions (UB) and entire eluates from avidin beads representing bound fractions (B) were loaded on to gels and the blot was probed with NET monoclonal antibody. Representative blots show two species of NET-specific bands at ~85 kDa and ~48 kDa. The amount of biotinylated and nonbiotinylated NETs were quantified using NIH image, and the densities of ~85 kDa band from three separate experiments are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Densities of biotinylated NETs are shown in upright bar graphs (A-D) and densities of nonbiotinylated NETs are shown in inverted bar graphs (A-C). *s indicate significant changes in cell surface and intracellular NETs following AMPH treatment compared to respective vehicle treatment (*, p < 0.01 by Student’s t-test). The blots corresponding to total were reprobed with anti-calnexin antibody to insure equal protein loading. *s indicate significant reductions in cell surface NET levels following AMPH treatment (*, p < 0.01 by Student’s t-test).

AMPH reduced plasma membrane recycling/exocytosis of both WT-hNET and hNET-DM

Reduction in the plasma membrane expression of NET following AMPH could arise either from an inhibition in the plasma membrane insertion or from an increase in the endocytosed NET or from a net result of both. Figure 3 shows the results from biotinylation experiments performed to measure the plasma membrane insertion of NET in HTR-hNET and HTR-hNET-DM stable cells following AMPH treatment. There was no biotinylated NET or TfR at zero time point in sulfo-NHS acetate treated cells suggesting that all pre-existing surface NETs or TfRs are completely blocked (from modification by biotinylation), and thus, that biotinylated NET observed in subsequent time points after warming the cells to 37° C represents newly delivered or recycling NET only. Results in figure 3 show a gradual time-dependent increase in NET levels on the plasma membrane of HTR-hNET and HTR-hNET-DM cells following vehicle treatment reaching a plateau by 30 min. This represents constitutive recycling of NET to and from the plasma membrane. The constitutive plasma membrane recycling of NET was significantly reduced following AMPH treatment of HTR-hNET (Fig. 3A) or hNET-DM (Fig. 3B) cells at 1, 5 and 15 min time points. However, AMPH had no significant effect on NET plasma membrane recycling beyond 15 min treatment time-point. Time-dependent increases in plasma membrane TfR levels were observed under similar conditions indicating that under trafficking permissive conditions, majority of NET protein reaches the plasma membrane in 30 min. AMPH had no significant effect on TfR recycling (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. AMPH decreases NET plasma membrane recycling of both WT-hNET and hNET-DM following short time treatments.

(A) HTR-hNET and (B) HTR-hNET-DM stable cells were treated with sulfo-NHS-acetate to block all the free amino groups prior to biotinylation with sulfo-NHS-biotin in the presence of vehicle or 10 μM AMPH for indicated time periods. Isolation of biotinylated and nonbiotinylated proteins and immunoblotting of NET proteins were performed as described under Materials and Methods section. A representative blot from biotinylation experiments shows changes in surface density of NETs following AMPH treatment. Biotinylated NETs (85 kDa) were quantified using NIH image, and band densities measured as % of total from three different experiments are shown in the lower panel as the mean ± S.E.M (Bar graphs). *s indicate significant changes in the recycling of plasma membrane NET following AMPH treatment compared to respective vehicle treatment at each time point (p < 0.05 by Student’s t-test). The blots were reprobed with anti-TfR antibody to examine drug-specific effect.

While AMPH stimulated WT-hNET endocytosis, it had no effect on hNET-DM endocytosis

AMPH downregulated WT-hNET and failed to downregulate hNET-DM (Figs. 1&2). Moreover, AMPH inhibited plasma membrane delivery of both WT-hNET and hNET-DM (Fig. 3). Therefore, next, we examined the internalization of WT-hNET and hNET-DM under basal/constitutive condition, and following treatment with AMPH using reversible biotinylation strategies and by quantifying the fraction of surface NET that moves in a time-dependent manner to an intracellular compartment. Biotin from biotinylated proteins remaining on the surface at the end of a particular treatment protocol was removed by treatment with MesNa, a non-permeant reducing agent that reduces disulfide bonds and liberates biotin from biotinylated proteins at the cell surface. The amount of biotinylated proteins resistant (inaccessible) to MesNa treatment or reversal of biotinylation is defined as “the amount of protein endocytosed or internalized”. Incubation of the cells at 37°C in the absence or presence of AMPH before MesNa reversal of surface biotinylation permitted evaluation of NET internalization occurring in the absence of AMPH (basal endocytosis) versus AMPH-mediated changes in NET internalization. The amount of NET that is biotinylated in the absence of MesNa represents total biotinylated transporter. MesNa treatment immediately after biotinylation showed less than 2-3% of total biotinylated NET indicating very little internalization and establishing the efficiency of biotin removal from surface biotinylated NET. Following treatment with vehicle alone, a gradual increase in biotinylated NET immunoreactivity was seen over time in HTR cells stably expressing WT-hNET (Fig. 4A) or hNET-DM (Fig. 4B) reaching a plateau by 30 min. This increase in the internalized NET represents constitutive or basal endocytosis. When compared to vehicle, AMPH significantly increased WT-hNET immunoreactivity (Fig. 4A), but failed to show any significant effect on hNET-DM internalization at all time points examined (4B). The percent internalization was shown in the lower panels. In HTR-hNET or HTR-hNET-DM cells, a maximum of ~50% of surface biotinylated NET was internalized by 30 min under unstimulated (basal) conditions. A 25-30% increase in NET immunoreactivity was observed only in HTR-hNET cells following AMPH treatment at the time-points examined. On the other hand, NET immunoreactivity was unaltered in HTR-hNET-DM cells following AMPH treatment (Fig. 4B). Under similar conditions, time-dependent internalization of TfR was not affected by AMPH treatment. These results collectively demonstrate that enhanced transporter endocytosis contributes to AMPH-mediated transporter downregulation. The results also demonstrate that hNET-DM exhibits resistance to AMPH-induced endocytosis.

Figure 4. AMPH-induced NET endocytosis is blunted in hNET-DM.

(A) HTR-hNET and (B) HTR-hNET-DM stable cells were biotinylated with sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin and incubated with vehicle or 10 μM AMPH for indicated time periods. Following MesNa treatment, biotinylated (internalized) NETs were isolated and analyzed as described under Materials and Methods section. Representative immunoblots from three separate experiments are given in upper panels. The bar graphs show biotinylated NET levels. The densities of ~85 kDa band from three separate experiments are given as mean ± S.E.M. *s indicate significant changes in NET internalization following AMPH treatment compared to vehicle treatment at each time point (p < 0.05 by Student’s t-test). The blots were reprobed with anti-TfR antibody to examine drug-specific effect.

AMPH-induced NET downregulation is neither Ca2+/CaMKII nor PKC -dependent, but DMI-specific

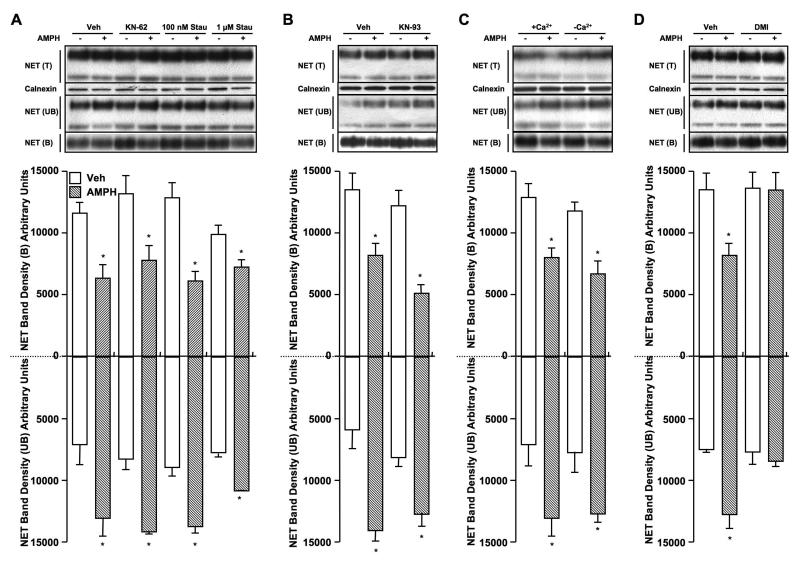

Since we found that the PKC-insensitive T258A/S259A double mutant is resistant to AMPH mediated NET downregulation, and many signaling pathways including PKCs and CaMKs exist in the placental trophoblasts (Daoud et al. 2005; Knofler et al. 2005), we explored the possible signaling mechanism involved in AMPH- mediated NET downregulation. First we examined the effect of PKC or CaMKII inhibition on AMPH-induced changes in the NET surface expression using biotinylation assay. We examined cell surface NET expression in HTR-hNET cells following AMPH treatment in the presence or absence of staurosporine, KN-62 or DMI. As shown in figure 5A, neither staurosporine (PKC inhibition) nor KN-62 (CaMKII inhibition) blocked AMPH-induced reductions in cell surface NET levels. KN-93, another CaMKII inhibitor also failed to block AMPH-induced NET downregulation (Fig. 5B). In addition, depletion of Ca2+ using BAPTA-AM treatment did not prevent AMPH-mediated decrease in surface NET (Fig. 5C). Together these results indicate that AMPH-mediated NET downregulation is neither PKC nor Ca2+/CaMKII dependent. Next we asked the question whether AMPH-induced NET downregulation is sensitive to NET- specific blocker by testing AMPH effect in the presence or absence of DMI. Surprisingly, AMPH-induced reduction in NET surface level was completely blocked by pretreatment with DMI (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5. PKC- or CAMKII- independent and DMI-sensitive NET down-regulation by AMPH.

HTR-hNET stable cells were pretreated with (A) vehicle or 10 μM KN-62 or 100 nM or 1 μM staurosporine; (B) vehicle or 10 μM KN-93; for 10 min at 37°C and incubations were continued in the presence or absence of 10 μM AMPH for 60 min; (C) HTR-hNET cells were treated with the membrane-permeant Ca2+ chelator BAPTA-AM (10 μM) in Ca2+-free KRH buffer for 2 h at 37 °C to deplete both external and internal Ca2+ as described earlier (Jayanthi et al. 2004) or in parallel incubated in normal KRH buffer, and then treated with vehicle or 10 μM AMPH for 60 min at 37 °C; (D) HTR-hNET cells were treated with vehicle or 10 μM DMI (NET-specific blocker) for 10 min at 37°C and incubations were continued in the presence or absence of 10 μM AMPH for 60 min. Drug-treated cells were used for biotinylation assays as described under Materials and Methods section. Equal aliquots from total (T) and avidin unbound fractions (UB) and entire eluates from avidin beads representing bound fractions (B) were loaded on to gels and the blots were probed with NET monoclonal antibody. Representative blots show two species of NET-specific bands at ~85 kDa and ~48 kDa. The amount of biotinylated and nonbiotinylated NETs were quantified using NIH image, and the densities of ~85 kDa band from three separate experiments are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Densities of biotinylated NETs are shown in upright bar graphs and densities of nonbiotinylated NETs are shown in inverted bar graphs. *s indicate significant changes in cell surface and intracellular NETs following AMPH treatment compared to respective vehicle treatment (p < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test). The blots corresponding to total were reprobed with anti-calnexin antibody to insure equal protein loading.

To further confirm whether or not CaMKII is involved in AMPH-mediated NET downregulation, we measured changes in cell surface NET levels in HTR-hNET cells following AMPH treatment in the presence or absence of a specific cell permeable CaMKII inhibitor, AIP. As shown in Fig. 6, AIP at 20 μM concentration failed to block AMPH-induced reductions in NET surface density. There were no significant changes in total NET protein levels following treatments with kinase inhibitors or DMI (Figs 5 & 6). To confirm that KN-93, KN-62 and AIP were effective in inhibiting CaMKII, we tested their effects on phospho-CaMKII (p-CaMKII) levels following 10 and 60 min treatments (Fig. 6B & 6C). KN-93 and KN-62 both were effective in reducing p-CaMKII immunoreactivity, as assessed by immunoblot experiments with anti-phospho-CaMKII antibody. Immunoreactivity of p-CaMKII was also reduced by 20 μM AIP treatment, but to a lesser extent (Fig. 6B & 6C). Under the treatment conditions employed, all three inhibitors were effective in reducing p-CaMKII immunoreactivity maximally by 10 min (Fig. 6B), and sustained for 60 min (Fig. 6C). In addition, interestingly, AMPH treatment alone for 60 (Fig. 6B) or 10 min (Fig 6C) did not alter p-CaMKII levels.

Figure 6. AIP failed to block AMPH-induced NET downregulation and AMPH did not alter phospho(p)-CaMKII levels.

(A) HTR-hNET stable cells were pretreated with vehicle or 20 μM AIP for 10 min at 37°C and incubations were continued in the presence or absence of 10 μM AMPH. Drug-treated cells were used for biotinylation assays as described under Materials and Methods section. Equal aliquots from total (T) and avidin unbound fractions (UB) and entire eluates from avidin beads representing bound fractions (B) were loaded on to gels and the blots were probed with NET monoclonal antibody. Representative blots shows two species of NET-specific bands at ~85 kDa and ~48 kDa. The amount of biotinylated NET was quantified using NIH image, and the densities of ~85 kDa band from three separate experiments are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Bar graph shows biotinylated NET band densities as % of vehicle. *s indicates significant changes in surface NET immunoreactivity following AMPH treatment compared to respective vehicle-control (p < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test). (B) HTR-hNET stable cells were treated with vehicle or 10 μM KN-93 or 10 μM KN-62 or 20 μM AIP for 10 min at 37°C and incubations were continued in the presence or absence of 10 μM AMPH for 60 min. (C) HTR-hNET stable cells were treated with vehicle or 10 μM KN-93 or 10 μM KN-62 or 20 μM AIP for 60 min at 37°C and incubations were continued in the presence or absence of 10 μM AMPH for 10 min. Equal aliquots of cell extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-p-CaMKII antibody and the p-CaMKII immunoreactive bands were shown.

AMPH is more potent in inhibiting hNET-DM as well as T258A and S259A single mutants

Since AMPH-induced NET downregulation was sensitive to NET-specific inhibitor DMI, and having known that AMPH failed to downregulate hNET-DM, we next examined whether hNET-DM as well as T258A and S259A single mutants exhibit any changes in the affinity for AMPH. AMPH when present during transport assay, inhibited NE uptake by both HTR-hNET, HTR-hNET-DM, HTR-hNET-T258A and HTR-hNET-S259A cells in a dose dependent manner. The apparent Ki values (in μM) for AMPH were 0.44 ± 0.01, 0.086 ± 0.01, 0.123 ± 0.01 and 0.212 ± 0.02 in HTR-hNET, HTR-hNET-DM, HTR-hNET-T258A and HTR-hNET-S259A cells respectively. Thus, AMPH was 4 to 5 times more potent in inhibiting hNET-DM and 2-3 times more potent in inhibiting the single mutants compared to WT-hNET.

AMPH-mediated NET downregulation is partially blunted in HTR-hNET-T258A and HTR-hNET-S259A cells

As shown in Fig. 7, AMPH treatment reduced the cell surface levels of T258A and S259A mutant NETs by about 15-20%. In parallel experiments, AMPH produced a 40% reduction in WT-hNET cell surface levels. Although AMPH inhibition of single mutants was significantly less compared to AMPH inhibition of WT-hNET, the single-site mutants behave as though contributing additively when present together, and that may be the case with the DM.

Figure 7. AMPH-induced NET downregulation is partially blocked in HTR-hNET-T258A and HTR-hNET-S259A cells.

HTR-hNET, HTR-hNET-T258A and HTR-hNET-S259A stable cells were treated with vehicle or 10 μM AMPH for 60 min at 37°C and used for biotinylation assays as described under Materials and Methods section. Equal aliquots from total (T) and avidin unbound fractions (UB) and entire eluates from avidin beads representing bound fractions (B) were loaded on to gels and the blots were probed with NET monoclonal antibody. Representative blots shows two species of NET-specific bands at ~85 kDa and ~48 kDa. The amount of biotinylated NET was quantified using NIH image, and the densities of ~85 kDa band from three separate experiments are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Bar graph shows biotinylated NET band densities as % of vehicle. * and # indicate significant changes in cell surface NET following AMPH treatment compared to respective vehicle treatment (*, p < 0.01; #, p ≤ 0.05; by Student’s t-test).

AMPH accumulation in HTR cells expressing hNET-DM cells is not significantly different from that of HTR cells expressing WT-hNET

Having known that AMPH-induced NET downregulation is blunted in HTR cells expressing hNET-DM and since hNET-DM is more sensitive to AMPH inhibition, we next examined whether there are differences in intracellular accumulation of AMPH in HTR cells expressing WT-hNET or hNET-DM using radiolabeled AMPH. When used at 10 nM (below Ki) concentration, there was a time-dependent increase in AMPH accumulation in HTR cells transiently transfected with either 0.5 μg WT-hNET cDNA or 1μg hNET-DM cDNA (Fig. 8A). Following short time (1 & 5 min) incubations, AMPH accumulation (at 10 nM) was slightly higher (not at significant level) in cells expressing hNET-DM compared to cells expressing WT-hNET, and there were no differences beyond 5 min (Fig. 8A). When used at 10 μM concentration (used in all experiments in this study), AMPH accumulation was similar in HTR cells expressing WT-hNET or hNET-DM at all time points examined, and interestingly there was no time-dependency in AMPH accumulation (Fig. 8B). AMPH accumulation was significantly higher in HTR-hNET stable cells compared to HTR-hNET-DM stable cells due to higher versus lower NET protein expression levels (Fig. 8C).

Figure 8. AMPH accumulation is similar in HTR cells expressing either WT-hNET or hNET-DM.

HTR cells transiently expressing WT-hNET or hNET-DM were incubated with 10 nM AMPH (A) or 10 μM AMPH (B) in transport assay buffer and AMPH accumulation was measured as described under Materials and Methods section. (C) HTR-hNET or HTR-hNET-DM stable cells were incubated with 10 μM AMPH in transport assay buffer and AMPH accumulation was measured as described under Materials and Methods section. To define specific AMPH accumulation via NETs, parallel uptake assays were carried out in the presence of 100 μM DMI. Data derived from three separate experiments, each in triplicate are given as mean ± S.E.M.

DISCUSSION

Transport function is a measure of functional transporters present on the cell surface. Cell surface transport levels are dictated by transporter entry to the cell surface (exocytosis) as well as its exit from the surface (endocytosis). Results from the present study delineated the altered trafficking mechanisms dictating AMPH-mediated NET downregulation, and identified the structural motif contributing to DMI-sensitive AMPH-induced downregulation. Exposure of AMPH inhibits NE uptake and NET plasma membrane insertion and increases NET endocytosis. AMPH-triggered NET endocytosis is linked to T258/S259 motif and contributes to decreased cell surface NET. It is important to note that while decreased NET exocytosis/recycling and increased NET internalization account for AMPH-induced downregulation of WT-hNET, only decreased exocytosis/recycling may account for small nonsignificant decreases observed in NE uptake by hNET-DM and in the steady state levels of cell surface hNET-DM at short-time points. Notwithstanding the limitations and complexities of the techniques used, the data presented in this study indicate that T258A/S259A motif is involved only in AMPH-mediated internalization, but not in NET exocytosis/recycling.

It is evident that monoamine transporters are subjects to regulation by transport function, where substrates and antagonists modulate kinase and/or transporter-associated protein mediated regulation (Ramamoorthy and Blakely 1999; Saunders et al. 2000; Daws et al. 2002; Kahlig et al. 2004). PKC-resistant hNET-DM exhibits increased affinity toward substrate, NE (Jayanthi et al. 2006) and is more sensitive to inhibition by substrate-like ligand, AMPH (present study). Remarkably, hNET-DM is resistant to AMPH-induced endocytosis. However, the inhibition of transporter entry to cell surface following AMPH treatment observed in HTR-hNET cells remained intact in HTR-hNET-DM cells. Moreover, staurosporine failed to block AMPH-induced NET downregulation in HTR-hNET cells. It is important to note some of the differences we observed between PKC- and AMPH- mediated NET downregulation. Our previous study demonstrated that PKC activation stimulates raft-mediated NET endocytosis and does not affect transporter recycling to the plasma membrane (Jayanthi et al. 2006). AMPH-induced NET downregulation is partially blocked in HTR cells expressing T258A and S259A single mutants. It appears that T258A and S259A single mutants contribute additive resistance to AMPH-induced downregulation when present together. This behavior of single mutants is different from our previous findings where T258A and S259A single mutants retain their response to PKC activation unlike the DM (Jayanthi et al. 2006). Therefore, the results collectively suggest that T258/S259 motif is involved in AMPH-mediated NET downregulation, but in a PKC-independent manner and possibly independent of PKC-mediated phosphorylation at this motif. It is possible that the presence of threonine and serine residue itself at these positions may be important for AMPH-induced NET down-regulation since single mutants also behave similarly as the double mutant. It is possible that different conformational changes occurring due to PKC phosphorylation or binding of NET ligand render the transporter susceptible for trafficking changes by mechanisms yet to be identified.

A recent study has demonstrated accelerated DAT endocytosis and decreased DAT delivery to the plasma membrane following acute AMPH treatment (Boudanova et al. 2008). Although it is debatable whether AMPH-induced transporter downregulation is PKC-dependent (Cervinski et al. 2005; Chen et al. 2009) or independent (Boudanova et al. 2008), multiple mechanisms such as altered Ca2+-dependent protein kinases, protein-protein interactions and even altered transport function have been implicated in AMPH-mediated DAT regulation (Saunders et al. 2000; Gnegy et al. 2004; Kantor et al. 2004; Fog et al. 2006; Wei et al. 2007). Ca2+-mediated mechanisms regulate NET trafficking and interaction with transporter associated proteins (Apparsundaram et al. 1998; Sung et al. 2003; Dipace et al. 2007). In catecholaminergic cell line CAD, CaMKII dependent (KN-93 sensitive) NET-SYN1A association is implicated in AMPH-mediated NET downregulation (Dipace et al. 2007). In HTR cells, neither CaMKII nor PKC is involved in AMPH-mediated NET downregulation. Pretreatment with a specific cell permeable CaMKII inhibitor (AIP) (Aromolaran and Blatter 2005) as well as Ca2+ depletion did not block AMPH-induced NET downregulation. Moreover, AMPH treatment did not alter phospho-CaMKII immunoreactivity in HTR cells. Under the conditions tested, all three CaMKII inhibitors reduced basal phospho-CaMKII immunoreactivity suggesting that they are efficient in inhibiting CaMKII. PKC-mediated NET downregulation in HTR cells is also Ca2+-independent (Jayanthi et al. 2004). While the discrepancies between our studies and others remain to be understood, one possible explanation could be the use of two different host expression systems that may be influenced by cell specific factors.

Mutation of PKC-sensitive motif T258/S259 located near the cytoplasmic end of the fifth transmembrane domain (TM5) prevented AMPH-mediated NET downregulation. Deletion of amino acids 28-47 from NH2-termininus accelerates AMPH-mediated decrease in surface NET through CaMKII-dependent increase in NET-SYN1A interaction (Dipace et al. 2007). Interestingly, many factors such as intracellular Ca2+, activation of PKC, and inhibition of CaMKII or PP2A all regulate NET-SYN1A interaction (Sung et al. 2003; Sung et al. 2005; Dipace et al. 2007; Sung and Blakely 2007). NET- SYN1A interaction is implicated in regulating not only the surface expression but also the catalytic activity of NET (Sung et al. 2003). It is possible that SYN1A interaction at the N-tail may regulate permeation pathway located possibly at or near TM5. The location of T258/S259 phosphorylation site near the cytoplasmic end of TMD-5 is highly conserved among biogenic amine transporters. It has been postulated that modification of T276 in SERT via PKG-dependent phosphorylation alters TM5 conformation that leads to increased catalytic activity (Zhang et al. 2007) and altered SERT-PP2Ac interaction. Thus, our understanding has been that the conformational changes occurring due to AMPH binding and/or translocation may dictate the ability of AMPH to downregulate NET via phosphorylation dependent or independent mechanism with or without the influence of NET interacting proteins.

Our findings from previous study (Jayanthi et al. 2006) and this study indicate that the hNET-DM shows higher affinity toward substrates. Two non-transportable NET-specific ligands, DMI and nisoxetine were 2-3 fold less potent in inhibiting hNET-DM (data not shown). We believe that the differences observed in the affinities for the ligands may not be a factor for AMPH not having an effect on hNET-DM internalization, because hNET-DM exhibits higher affinity toward AMPH. However, the physiological significance of these differences needs to be determined. It is important to note that the transport constants for WT and DM in HTR-hNET and HTR-hNET-DM stable cells were similar to those reported earlier using transiently transfected cells (Jayanthi et al. 2006). Km: 5.45 ± 0.36 and 0.89 ± 0.25 μM; Vmax: 424 ± 12.5 and 64 ± 4.9 pmoles/100K cells/10 min in HTR-hNET and HTR-hNET-DM cells respectively. AMPH not having an effect on hNET-DM could be attributed to differences in the NET protein expression levels contributing to differences in AMPH accumulation. However, hNET-DM, when expressed to WT-hNET expression levels still exhibits resistance to AMPH-induced downregulation. In addition, at 10 μM concentration, AMPH accumulation was similar in HTR cells expressing either WT-hNET or hNET-DM. Although AMPH accumulation was higher in HTR-hNET stables compared to HTR-hNET-DM stables, given the fact that hNET-DM is resistant to AMPH-induced NET downregulation independent of expression levels indicate that intracellular AMPH levels do not contribute to observed differences between WT-hNET and hNET-DM behaviors.

Monoamine transporters undergo phosphorylation/ dephosphorylation and transporter substrates are known to modulate the degree of phosphorylation and transport function (Vaughan et al. 1997; Ramamoorthy et al. 1998; Ramamoorthy and Blakely 1999; Cervinski et al. 2005). Substrate translocation or ligand occupancy may influence the equilibrium of protein conformation required for transporter phosphorylation and/or transporter association with other regulators, which in turn may dictate transporter trafficking. In this regard, it should be noted that AMPH-induced NET downregulation is sensitive to NET-specific blocker DMI. Although the exact molecular link between AMPH-induced NET endocytosis and T258/S259 motif is not absolutely clear, it is tempting to speculate that WT-hNET when bound to DMI may adopt a conformation that is similar to that of hNET-DM. Future studies examining influx/efflux mechanisms that may be altered in hNET-DM and conformational analysis of this double mutant will further our understanding of NE transport regulation by AMPH.

In summary, our studies define a novel motif with in the NET and its role in the regulation of AMPH mediated NET activity and down regulation. Sequestration of surface transporters could be one of the cellular feed back mechanisms regulating the cell surface availability of transporters for AMPH to act, and provide a possible protective mechanism against the pathophysiological effects of chronic AMPH. The fact that T258+S259 is a potential regulatory motif, and the mutation of these sites renders NET to have high affinity for AMPH and strikingly, prevents AMPH-triggered NET endocytosis signifies the role that T258/S259 motif plays in regulating NET in response to AMPH. T258/S259 might be a potential site of action where by cellular signaling molecule(s) may target NET in response to AMPH binding. Genetic and pharmacological studies show that NET depletion or inhibition attenuate neuronal toxicity (Rommelfanger et al. 2004; Verrico et al. 2007; Sofuoglu and Sewell 2009). Evidence also exists demonstrating an association between AMPH response and NET gene variants (Dlugos et al. 2007; Dlugos et al. 2009). We thus speculate that dysregulation of NET linked to T258/S259 motif may disrupt normal transporter internalization and a prolonged disruption would allow more surface NETs available for AMPH, which in turn may lead to abnormal release of NE and higher uptake of AMPH into neurons or placental trophoblasts that ultimately manifest in neurotoxicity or teratogenicity associated with AMPH abuse. Further understanding of the regulatory cascades linked to T258/S259 motif will provide highly novel insights into AMPH modulated NE neurotransmission and its impact on behavior.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the grant GM081054 from National Institutes of Health/National Institute of General Medical Sciences awarded to LDJ.

Abbreviations

- NET

norepinephrine transporter

- AMPH

D-amphetamine

- PKC

protein kinase C

- CaMKII

Calcium/calmodulin dependent protein kinase-II

- DAT

dopamine transporter

- DMI

desipramine

- HTR

human placental trophoblast

- KRH

Krebs-Ringer-HEPES buffer

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- SERT

serotonin transporter

- SYN1A

syntaxin 1A

REFERENCES

- Apparsundaram S, Galli A, DeFelice LJ, Hartzell HC, Blakely RD. Acute regulation of norepinephrine transport: I. protein kinase C-linked muscarinic receptors influence transport capacity and transporter density in SK-N-SH cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;287:733–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aromolaran AA, Blatter LA. Modulation of intracellular Ca2+ release and capacitative Ca2+ entry by CaMKII inhibitors in bovine vascular endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;289:C1426–1436. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00262.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudanova E, Navaroli DM, Melikian HE. Amphetamine-induced decreases in dopamine transporter surface expression are protein kinase C-independent. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54:605–612. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervinski MA, Foster JD, Vaughan RA. Psychoactive substrates stimulate dopamine transporter phosphorylation and down-regulation by cocaine-sensitive and protein kinase C-dependent mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40442–40449. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501969200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Furman CA, Zhang M, Kim MN, Gereau R. W. t., Leitges M, Gnegy ME. Protein kinase Cbeta is a critical regulator of dopamine transporter trafficking and regulates the behavioral response to amphetamine in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;328:912–920. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.147959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Prusoff WH. Relationship between the inhibition constant (K1) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daoud G, Amyot M, Rassart E, Masse A, Simoneau L, Lafond J. ERK1/2 and p38 regulate trophoblasts differentiation in human term placenta. J Physiol. 2005;566:409–423. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.089326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daws LC, Callaghan PD, Moron JA, Kahlig KM, Shippenberg TS, Javitch JA, Galli A. Cocaine increases dopamine uptake and cell surface expression of dopamine transporters. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;290:1545–1550. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dipace C, Sung U, Binda F, Blakely RD, Galli A. Amphetamine induces a calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II-dependent reduction in norepinephrine transporter surface expression linked to changes in syntaxin 1A/transporter complexes. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:230–239. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.026690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dlugos A, Freitag C, Hohoff C, McDonald J, Cook EH, Deckert J, de Wit H. Norepinephrine transporter gene variation modulates acute response to D-amphetamine. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:1296–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dlugos AM, Hamidovic A, Palmer AA, de Wit H. Further evidence of association between amphetamine response and SLC6A2 gene variants. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;206:501–511. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1628-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fog JU, Khoshbouei H, Holy M, Owens WA, Vaegter CB, Sen N, Nikandrova Y, Bowton E, McMahon DG, Colbran RJ, Daws LC, Sitte HH, Javitch JA, Galli A, Gether U. Calmodulin kinase II interacts with the dopamine transporter C terminus to regulate amphetamine-induced reverse transport. Neuron. 2006;51:417–429. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnegy ME, Khoshbouei H, Berg KA, Javitch JA, Clarke WP, Zhang M, Galli A. Intracellular Ca2+ regulates amphetamine-induced dopamine efflux and currents mediated by the human dopamine transporter. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66:137–143. doi: 10.1124/mol.66.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iversen LL. Role of transmitter uptake mechanisms in synaptic neurotransmission. British J Pharmacol. 1971;41:571–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1971.tb07066.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayanthi LD, Samuvel DJ, Ramamoorthy S. Regulated internalization and phosphorylation of the native norepinephrine transporter in response to phorbol esters. Evidence for localization in lipid rafts and lipid raft-mediated internalization. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19315–19326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311172200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayanthi LD, Annamalai B, Samuvel DJ, Gether U, Ramamoorthy S. Phosphorylation of the norepinephrine transporter at threonine 258 and serine 259 is linked to protein kinase C-mediated transporter internalization. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:23326–23340. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601156200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahlig KM, Javitch JA, Galli A. Amphetamine regulation of dopamine transport. Combined measurements of transporter currents and transporter imaging support the endocytosis of an active carrier. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:8966–8975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303976200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantor L, Zhang M, Guptaroy B, Park YH, Gnegy ME. Repeated amphetamine couples norepinephrine transporter and calcium channel activities in PC12 cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;311:1044–1051. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.071068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller PC, 2nd, Stephan M, Glomska H, Rudnick G. Cysteine-scanning mutagenesis of the fifth external loop of serotonin transporter. Biochemistry. 2004;43:8510–8516. doi: 10.1021/bi035971g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knofler M, Sooranna SR, Daoud G, Whitley GS, Markert UR, Xia Y, Cantiello H, Hauguel-de Mouzon S. Trophoblast signalling: knowns and unknowns--a workshop report. Placenta. 2005;26(Suppl A):S49–51. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee-Kwon W, Kawano K, Choi JW, Kim JH, Donowitz M. Lysophosphatidic acid stimulates brush border Na+/H+ exchanger 3 (NHE3) activity by increasing its exocytosis by an NHE3 kinase A regulatory protein-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:16494–16501. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300580200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markou A, Kosten TR, Koob GF. Neurobiological similarities in depression and drug dependence: a self- medication hypothesis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1998;18:135–174. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramamoorthy S, Blakely RD. Phosphorylation and sequestration of serotonin transporters differentially modulated by psychostimulants. Science. 1999;285:763–766. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5428.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramamoorthy S, Giovanetti E, Qian Y, Blakely RD. Phosphorylation and regulation of antidepressant-sensitive serotonin transporters. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2458–2466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The neural basis of drug craving: an incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1993;18:247–291. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90013-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rommelfanger KS, Weinshenker D, Miller GW. Reduced MPTP toxicity in noradrenaline transporter knockout mice. J Neurochem. 2004;91:1116–1124. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders C, Ferrer JV, Shi L, Chen J, Merrill G, Lamb ME, Leeb-Lundberg LM, Carvelli L, Javitch JA, Galli A. Amphetamine-induced loss of human dopamine transporter activity: an internalization-dependent and cocaine-sensitive mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6850–6855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.110035297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schomig E, Fischer P, Schonfeld CL, Trendelenburg U. The extent of neuronal re-uptake of 3H-noradrenaline in isolated vasa deferentia and atria of the rat. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 1989;340:502–508. doi: 10.1007/BF00260604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofuoglu M, Sewell RA. Norepinephrine and stimulant addiction. Addict Biol. 2009;14:119–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00138.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung U, Blakely RD. Calcium-dependent interactions of the human norepinephrine transporter with syntaxin 1A. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;34:251–260. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung U, Jennings JL, Link AJ, Blakely RD. Proteomic analysis of human norepinephrine transporter complexes reveals associations with protein phosphatase 2A anchoring subunit and 14-3-3 proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;333:671–678. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung U, Apparsundaram S, Galli A, Kahlig KM, Savchenko V, Schroeter S, Quick MW, Blakely RD. A regulated interaction of syntaxin 1A with the antidepressant-sensitive norepinephrine transporter establishes catecholamine clearance capacity. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1697–1709. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01697.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsumi M, Groshan K, Blakely RD, Richelson E. Pharmacological profile of antidepressants and related compounds at human monoamine transporters. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;340:249–258. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01393-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trendelenburg U. The TiPs lecture: functional aspects of the neuronal uptake of noradrenaline. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1991;32:334–337. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90592-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan RA, Huff RA, Uhl GR, Kuhar MJ. Protein kinase C-mediated phosphorylation and functional regulation of dopamine transporters in striatal synaptosomes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15541–15546. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.24.15541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verrico CD, Miller GM, Madras BK. MDMA (Ecstasy) and human dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin transporters: implications for MDMA-induced neurotoxicity and treatment. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;189:489–503. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0174-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Williams JM, Dipace C, Sung U, Javitch JA, Galli A, Saunders C. Dopamine transporter activity mediates amphetamine-induced inhibition of Akt through a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II-dependent mechanism. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:835–842. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.026351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Gainetdinov RR, Wetsel WC, Jones SR, Bohn LM, Miller GW, Wang YM, Caron MG. Mice lacking the norepinephrine transporter are supersensitive to psychostimulants. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:465–471. doi: 10.1038/74839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita A, Singh SK, Kawate T, Jin Y, Gouaux E. Crystal structure of a bacterial homologue of Na+/Cl--dependent neurotransmitter transporters. Nature. 2005;437:215–223. doi: 10.1038/nature03978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YW, Gesmonde J, Ramamoorthy S, Rudnick G. Serotonin transporter phosphorylation by cGMP-dependent protein kinase is altered by a mutation associated with obsessive compulsive disorder. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10878–10886. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0034-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu MY, Shamburger S, Li J, Ordway GA. Regulation of the human norepinephrine transporter by cocaine and amphetamine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;295:951–959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]