Abstract

Recent developments in electrophysiological and optical recording techniques enable the simultaneous observation of large numbers of neurons. A meaningful interpretation of the resulting multivariate data, however, presents a serious challenge. In particular, the estimation of higher-order correlations that characterize the cooperative dynamics of groups of neurons is impeded by the combinatorial explosion of the parameter space. The resulting requirements with respect to sample size and recording time has rendered the detection of coordinated neuronal groups exceedingly difficult. Here we describe a novel approach to infer higher-order correlations in massively parallel spike trains that is less susceptible to these problems. Based on the superimposed activity of all recorded neurons, the cumulant-based inference of higher-order correlations (CuBIC) presented here exploits the fact that the absence of higher-order correlations imposes also strong constraints on correlations of lower order. Thus, estimates of only few lower-order cumulants suffice to infer higher-order correlations in the population. As a consequence, CuBIC is much better compatible with the constraints of in vivo recordings than previous approaches, which is shown by a systematic analysis of its parameter dependence.

Keywords: Multichannel recordings, Spike train analysis, Higher-order correlations, Cell assembly hypothesis

Introduction

More than 50 years after its first conception (Hebb 1949), the idea that entities of thought or perception are represented by the coordinated activity of (large) neuronal groups has lost nothing of its attraction (e.g., Wennekers et al. 2003; Harris 2005; Sakurai and Takahashi 2006). Now known as the “assembly hypothesis”, the concept of a single, unified principle underlying such diverse computational tasks as association and pattern completion (e.g., Palm 1982), binding (e.g., Singer and Gray 1995), language processing (e.g., Wennekers et al. 2006), or memory formation and retrieval (e.g., Pastalkova et al. 2008) has inspired numerous theoretical and experimental neuroscientists. However, whether or not the dynamic formation of cell assemblies constitutes a fundamental principle of cortical information processing remains a controversial issue of current research (e.g., Singer 1999; Shadlen and Movshon 1999; van Vreeswijk 2006). While initially mainly technical problems limited the experimental surge for support of the assembly hypothesis (state-of-the-art electrophysiological setups in the last century allowed to record only few neurons simultaneously), the recent advent of multi-electrode array and optical imaging techniques reveals fundamental shortcomings of available analysis tools (Brown et al. 2004).

Based on the efficacy of synchronized presynaptic spikes to reliably generate output spikes (Abeles 1982; König et al. 1995; Diesmann et al. 1999), the temporal coordination of spike timing is a commonly accepted signature of assembly activity (e.g., Gerstein et al. 1989; Abeles 1991; Singer et al. 1997; Harris 2005). Consequently, approaches to detect assembly activity have focused on the detection of correlated spiking. Statistically, coordinated spiking of large neuronal groups has been associated to higher-order correlations among the corresponding spike trains (Martignon et al. 1995, 2000), where “genuine higher-order correlations” are assumed, if coincident spikes of a neuronal group cannot be explained/predicted by the firing rate and pairwise correlations alone. Mathematical frameworks for the estimation of such correlations exist (Nakahara and Amari 2002; Martignon et al. 1995; Schneider and Grün 2003; Gütig et al. 2003), however, run into combinatorial difficulties, as they assign one correlation parameter for each group of neurons and thus require in the order of 2N parameters for a population of N simultaneously recorded neurons. Comparing the number of parameters to the available sample size of typical electrophysiological recordings (e.g. a population of N = 100 neurons implies ∼1030 parameters while 100 s of data sampled at 10 kHz provide ∼106 samples) illustrates the principal infeasibility of this approach. In fact, the estimation of such higher-order correlations runs into severe practical problems even for populations of N∼10 neurons (Martignon et al. 1995, 2000; Del Prete et al. 2004).

Due to the limitations of multivariate approaches, most studies in favor of cortical cell-assemblies resort to pairwise interactions. And indeed, the existence and functional relevance of pairwise interactions has been demonstrated in various cortical systems and behavioral paradigms (e.g., Eggermont 1990; Vaadia et al. 1995; Kreiter and Singer 1996; Riehle et al. 1997; Kohn and Smith 2005; Sakurai and Takahashi 2006; Fujisawa et al. 2008). However, although pairwise analysis can indicate highly correlated groups of neurons (Berger et al. 2007; Fujisawa et al. 2008), knowledge of higher-order correlations is essential to conclude on large, synchronously firing assemblies (see examples in Fig. 4 for illustration). The importance to transcend pairwise descriptions of parallel spike trains is further underscored by the strong impact of higher-order correlations on the dynamics of cortical neurons (e.g., Bohte et al. 2000; Kuhn et al. 2003). Taken together, we believe that the increasing number of simultaneously observable neurons can only be exploited by analysis techniques that go beyond mere pairwise correlations but are nevertheless applicable given the limited sample size of electrophysiological data (Brown et al. 2004).

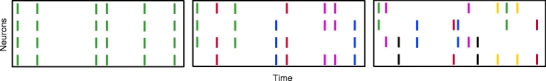

Fig. 4.

CuBIC results for three example data sets with identical rates and pairwise correlations, but different higher-order correlations (each column shows one data set). Amplitude distributions (top, logarithmic y-scale) illustrate the correlation structure of the respective CPP. Below are the raster displays of the activities of N = 100 processes demonstrated for a period of the first 2 s of a total simulation time of T = 100 s. The third panels from top show the population spike counts of the data, computed with a bin width of h = 5 ms. Their histograms (of the total simulation time) are shown in the fourth panel as the complexity distribution Z (blue bars) and its logarithmically transformed version (green line graph, y-axis on the right). The bottom panels show the results of CuBIC, i.e. the p-values for subsequent hypothesis tests assuming increasingly higher ξ in the null-hypotheses  . The left graph shows the results for the second cumulant (m = 2), the graph on the right uses the third cumulant (m = 3), respectively. Red filled circles denote p-values below a significance level of α = 0.05. Correlation in the data sets was induced by events of amplitude ξ

syn = 2 (Set1, left), ξ

syn = 7 (Set2, middle), and ξ

syn = 15 (Set3, right), that were injected in addition to the background spikes at ξ = 1. In all data sets, the carrier rate ν and the relative probabilities of events of amplitude 1 and ξ

syn were chosen to mimic N = 100 neurons with identical firing rates (10 Hz). We let 70 of those neurons fire independently (neuron IDs 1-70) and N

C = 30 to form a homogeneously correlated subgroup with a count-correlation coefficient of c = 0.01 (neuron IDs 71 - 100), yielding higher-order event rates

. The left graph shows the results for the second cumulant (m = 2), the graph on the right uses the third cumulant (m = 3), respectively. Red filled circles denote p-values below a significance level of α = 0.05. Correlation in the data sets was induced by events of amplitude ξ

syn = 2 (Set1, left), ξ

syn = 7 (Set2, middle), and ξ

syn = 15 (Set3, right), that were injected in addition to the background spikes at ξ = 1. In all data sets, the carrier rate ν and the relative probabilities of events of amplitude 1 and ξ

syn were chosen to mimic N = 100 neurons with identical firing rates (10 Hz). We let 70 of those neurons fire independently (neuron IDs 1-70) and N

C = 30 to form a homogeneously correlated subgroup with a count-correlation coefficient of c = 0.01 (neuron IDs 71 - 100), yielding higher-order event rates  of ν

2 = 43.5 Hz in Set1, ν

7 = 2.07 Hz in Set2 and ν

15 = 0.41 Hz in Set3. Test parameters: α = 0.05, ξ

max = 15, m

max = 4

of ν

2 = 43.5 Hz in Set1, ν

7 = 2.07 Hz in Set2 and ν

15 = 0.41 Hz in Set3. Test parameters: α = 0.05, ξ

max = 15, m

max = 4

In this study, we present a novel cumulant based inference procedure for higher-order correlations (CuBIC). The method is specifically designed to detect the presence of higher-order correlations under the constraints of the limited sample size typical of standard experimental paradigms. This is achieved by combining three basic ideas. First, CuBIC is based on the binned and summed spiking activity across all recorded neurons (population spike count). This transforms the multivariate problem to estimate all ∼2N model parameters into a parsimoniously parametrized univariate problem, thereby dramatically reducing the required sample size. Furthermore, pooling the spiking activity avoids the need for sorting the multi-unit spike trains recorded on a single electrode into isolated single neuron spike trains. Correlations among the individual spike trains are measured by the cumulants of the population spike count. Importantly, the cumulant correlations of higher order used here do not conform to the higher-order parameters of the exponential family used by, e.g., Schneidman et al. (2006). Second, we use the compound Poisson process (e.g., Snyder and Miller 1991; Daley and Vere-Jones 2005) as a flexible, intuitive, and analytically tractable model of correlated spiking activity. Here, correlations among spike trains are modeled by the insertion of additional coincident events in continuous time (Holgate 1964; Ehm et al. 2007; Johnson and Goodman 2008; Staude et al. 2010). As a consequence, the conceptual difference between the discretely sampled data (population spike count) and the continuous time spike trains is an explicit feature of the present framework. And third, we formalize the observation that even small correlations of lower order can imply synchronized spiking of large neuronal groups (Amari et al. 2003; Benucci et al. 2004; Schneidman et al. 2006).

The first and second ideas are elaborated in Section 2. Based on the compound Poisson process, Section 3 thoroughly formalizes the third idea, where we analytically derive confidence intervals for a hierarchy of statistical hypothesis tests. The tests are then combined to compute a lower bound  for the order of correlations in a given data set . Importantly, the inferred lower bound

for the order of correlations in a given data set . Importantly, the inferred lower bound  can considerably exceed the order of the estimated correlations. Thereby, CuBIC avoids the direct estimation of higher-order correlations, which is practically infeasible for orders of

can considerably exceed the order of the estimated correlations. Thereby, CuBIC avoids the direct estimation of higher-order correlations, which is practically infeasible for orders of  , but nevertheless reveals their presence. As shown by extensive Monte Carlo simulations (Section 4), using the third cumulant suffices to reliably detect existing correlations of order > 10 in large neuronal pools (here N∼100 neurons with average count-correlation coefficients of c∼0.01). Thus, CuBIC achieves an unprecedented sensitivity for higher-order correlations in scenarios with reasonable sample sizes, i.e. experiment durations of T < 100 s. The Discussion section relates the cumulant-based correlations used here to the higher-order interaction parameters of the exponential family (e.g., Martignon et al. 1995; Nakahara and Amari 2002; Shlens et al. 2006) and critically discusses the implications of the hypothesized compound Poisson process. Preliminary results have been presented previously in abstract form (Staude et al. 2007).

, but nevertheless reveals their presence. As shown by extensive Monte Carlo simulations (Section 4), using the third cumulant suffices to reliably detect existing correlations of order > 10 in large neuronal pools (here N∼100 neurons with average count-correlation coefficients of c∼0.01). Thus, CuBIC achieves an unprecedented sensitivity for higher-order correlations in scenarios with reasonable sample sizes, i.e. experiment durations of T < 100 s. The Discussion section relates the cumulant-based correlations used here to the higher-order interaction parameters of the exponential family (e.g., Martignon et al. 1995; Nakahara and Amari 2002; Shlens et al. 2006) and critically discusses the implications of the hypothesized compound Poisson process. Preliminary results have been presented previously in abstract form (Staude et al. 2007).

Measurement & model

Measurement

Assume an observation of a large number of parallel spike trains. To measure correlation, we describe such a population as a succession of “patterns”,  (T denotes transpose), one pattern for every time bin of width h. The components of X are the binned, discretized spike trains, i.e. X

i(s) is the spike count of the ith neuron in the interval [s,s + h). Given these patterns, we define the population spike count Z(s) at s as the total spike count in the sth bin (Fig. 1)

(T denotes transpose), one pattern for every time bin of width h. The components of X are the binned, discretized spike trains, i.e. X

i(s) is the spike count of the ith neuron in the interval [s,s + h). Given these patterns, we define the population spike count Z(s) at s as the total spike count in the sth bin (Fig. 1)

|

Fig. 1.

Schema of the compound Poisson process and its measurement. Left half: spike event times (horizontal bars) of individual neurons x 1(t),...,x N(t) and tick marks of the carrier process z(t) (top) with the associated amplitudes (numbers above the ticks), represented in continuous time. The population spike count Z(s) (below the spike trains) counts the number of spikes across all neurons in bins of width h (dotted lines). Right half: distribution of the amplitudes a j of the carrier process z(t) (amplitude distribution f A, top) and distribution of the population spike count Z(s) (complexity distribution f Z, bottom, estimated from 100 s of data with the given amplitude distribution and a bin size of h = 5ms; dashed line: Poisson fit, corresponding to an independent population with the same firing rates). To construct a population of correlated spike trains, amplitudes a j are drawn for all events t j in the carrier process i.i.d from f A. The individual processes x i(t) are then constructed by copying every event at t j of the carrier process z(t) into a j “child” processes x i(t) (the specific process IDs are here drawn randomly from {1,...,N}). Correlations of order ξ are induced, whenever events in the carrier process are copied into more than ξ processes, i.e. if the amplitude distribution assigns non-zero probabilities for amplitudes ≥ ξ (see Theorem 1 in Section 2.4)

The variable Z(s), from here on referred to as the “complexity” of the population at s, counts the number of spikes that fall into the interval [sh,(s + 1)h), irrespective of the neuron IDs that emitted these spikes. In the case where the X i are binary (“1” for one or more spikes in the bin, “0” for no spike), Z(s) is simply the number of neurons that spike in the time slice. As opposed to most other frameworks for correlation analysis (e.g., Aertsen et al. 1989; Martignon et al. 1995; Grün et al. 2002a; Nakahara and Amari 2002; Shlens et al. 2006), however, the method presented in this study does not assume binary variables. As a consequence, our term “complexity” as the “number of spikes per bin in the population” does not comply with the “number of active neurons per bin” used in binary frameworks.

To regard the values of Z(s) in different bins as i.i.d. random variables, we here assume that Z(s) and Z(s + k) are independent for k ≠ 0 (zero memory), and that the distribution of Z(s) does not depend on the time bin s (stationarity). We name the resulting distribution of population spike counts

|

the “complexity distribution” of the population. The validity of these assumptions with respect to real spike trains, and potential adaptations of CuBIC, are discussed in Section 5.3.

Despite ignoring the specific neuron IDs that contribute to the patterns X(s), the complexity distribution nevertheless contains information about the correlation structure of the population. For instance, if the counting variables {X i}i ∈ {1,...,N} are independent Poisson counts, the corresponding population spike count, being the sum of the independent Poisson variables, is again a Poisson variable, and thus the complexity distribution f Z is a Poisson distribution. Correlations change the relative probabilities for patterns of high and low complexities as compared to the independent case, as can be seen by comparing the complexity distribution of the correlated population and its independent Poisson fit in Fig. 1 (blue bars and dashed gray line, respectively; see also Grün et al. 2008a and Louis and Grün 2009). We quantify such deviations from independence by means of the cumulants κ m[Z] of the population spike count Z.

Correlations and cumulants

Like the more familiar (raw) moments  of a random variable Z, the cumulants κ

m[Z] characterize the shape of its distribution (see Appendix A and, e.g., Stratonovich 1967; Gardiner 2003). Most common are the first two cumulants, the expectation and the variance. These admit simple expressions in terms of the moments:

of a random variable Z, the cumulants κ

m[Z] characterize the shape of its distribution (see Appendix A and, e.g., Stratonovich 1967; Gardiner 2003). Most common are the first two cumulants, the expectation and the variance. These admit simple expressions in terms of the moments:  and

and  . Similar expressions for higher cumulants, however, are exceedingly complicated (see Stuart and Ord 1987 for explicit expressions for m ≤ 10).

. Similar expressions for higher cumulants, however, are exceedingly complicated (see Stuart and Ord 1987 for explicit expressions for m ≤ 10).

The most important property of cumulants, and their advantage over the raw moments is that the cumulant of the sum of independent random variables is the sum of their cumulants. For m = 2 and  , for instance, we have the well-known variance-covariance relationship

, for instance, we have the well-known variance-covariance relationship

|

1 |

Equation (1) shows that  if

if  , which is the case if the X

i are (pairwise) uncorrelated. Cumulant correlations of higher order, the so-called “mixed” or “connected” cumulants, are a straightforward generalization of the covariance in exactly this sense: if the population has neither pairwise nor triple-wise cumulant correlations, then

, which is the case if the X

i are (pairwise) uncorrelated. Cumulant correlations of higher order, the so-called “mixed” or “connected” cumulants, are a straightforward generalization of the covariance in exactly this sense: if the population has neither pairwise nor triple-wise cumulant correlations, then  (see Appendix A for a concise definition, and Gardiner 2003, for a general introduction). Higher-order cumulant correlations generalize the covariance also with respect to the fact that

(see Appendix A for a concise definition, and Gardiner 2003, for a general introduction). Higher-order cumulant correlations generalize the covariance also with respect to the fact that  implies

implies  . That is, if the multivariate random vector X decomposes into independent subgroups, then the cumulant correlations vanish (Streitberg 1990). For notational consistency, we will from now on stick to the cumulant notation, e.g., use “first/second cumulant” instead of the more familiar terms “mean/variance”.

. That is, if the multivariate random vector X decomposes into independent subgroups, then the cumulant correlations vanish (Streitberg 1990). For notational consistency, we will from now on stick to the cumulant notation, e.g., use “first/second cumulant” instead of the more familiar terms “mean/variance”.

A further consequence of Eq. (1) is that κ

2[Z] is influenced only by the single process statistics (via  ) and pairwise correlations (via

) and pairwise correlations (via  ). No higher-order correlations contribute to the second cumulant. This holds also for higher cumulants, i.e. κ

m[Z] depends on correlations among the X

i of maximal order m. And finally, in the same way that κ

2[Z] depends on pairwise correlations and the single process statistics, also κ

m[Z] does not measure pure mth order correlations, but depends on correlations of all orders up to m. While a correction of the second cumulant for the influence of the single process statistics would be straightforward (subtracting

). No higher-order correlations contribute to the second cumulant. This holds also for higher cumulants, i.e. κ

m[Z] depends on correlations among the X

i of maximal order m. And finally, in the same way that κ

2[Z] depends on pairwise correlations and the single process statistics, also κ

m[Z] does not measure pure mth order correlations, but depends on correlations of all orders up to m. While a correction of the second cumulant for the influence of the single process statistics would be straightforward (subtracting  in Eq. (1), see Appendix B), correcting higher cumulants for the influence of correlations of lower order is exceedingly complicated. We therefore employ a parametric model for Z, the compound Poisson process (see next section), the parameters of which can be interpreted straightforwardly in terms of higher-order correlations among the X

i.

in Eq. (1), see Appendix B), correcting higher cumulants for the influence of correlations of lower order is exceedingly complicated. We therefore employ a parametric model for Z, the compound Poisson process (see next section), the parameters of which can be interpreted straightforwardly in terms of higher-order correlations among the X

i.

We would like to stress that the higher-order correlations defined by cumulants differ strongly from the higher-order parameters of the exponential family used by, e.g. Martignon et al. (1995), Nakahara and Amari (2002), Shlens et al. (2006). The relationship between these two frameworks is discussed in more detail in Section 5.1 (see also Staude et al. 2010).

Model

As opposed to the discretized, i.e. binned, population spike count Z(s) of the previous section, the proposed model operates in continuous, i.e. unbinned time. That is, we model the process  , where

, where  denotes the ith unbinned, continuous-time spike train (i = 1,...,N) with spike-event times

denotes the ith unbinned, continuous-time spike train (i = 1,...,N) with spike-event times  . The model we propose for z(t) is that of a compound Poisson process (CPP)

. The model we propose for z(t) is that of a compound Poisson process (CPP)

|

2 |

where the event times t

j constitute a Poisson process, and the marks a

j are i.i.d. integer-valued random variables, drawn independently for all t

j. The marks a

j determine the number of neurons that fire at time t

j, and will be referred to as the “amplitude” of the event at time t

j. The probability that an event has a specific amplitude is determined by the amplitude distribution f

A, i.e.  (see Fig. 1). The Poisson process that generates the events t

j is called the “carrier process” of the model and its rate ν is the “carrier rate”. Processes of this type are also referred to as generalized, or marked, Poisson processes (see e.g. Snyder and Miller 1991 for a general definition and Ehm et al. 2007 for an application to spike train analysis).

(see Fig. 1). The Poisson process that generates the events t

j is called the “carrier process” of the model and its rate ν is the “carrier rate”. Processes of this type are also referred to as generalized, or marked, Poisson processes (see e.g. Snyder and Miller 1991 for a general definition and Ehm et al. 2007 for an application to spike train analysis).

To interpret the CPP as the lumped process of a correlated population of N spike trains, and to utilize the CPP for the generation of artificial data, the events of z(t) are assigned to individual processes x i(t) (i = 1,...,N). The simplest model draws the a j process IDs that receive a spike at t j as a random subset from {1,...N}, independently for all event times t j (Fig. 1). This results in a homogeneous population of correlated Poisson processes, where all processes have the same rate, all pairs of processes have identical correlations, and so on. The SIP/MIP models presented in Kuhn et al. (2003) are special cases of this more general model (see also Appendix B for examples). As the inference procedure CuBIC presented in the remainder of this study is based solely on the summed activity, however, it is not affected by the details of the copying procedure. In particular, CuBIC does not presuppose that the population is homogeneous.

Relating measurement and model

To interpret the continuous-time model parameters ν and f

A in terms of correlations among the counting variables X

i, we now relate the former to the cumulants of the population spike count Z. First of all, note that as the carriers process z(t) is a Poisson process, the population spike counts in different bins are i.i.d. For l = 1,...,N, define the processes y

l(t) that determine all event times t

j in Eq. (2) with given amplitude a

j = l (compare Appendix A). Then the CPP z(t) admits the representation  . As a consequence, the discretized population spike count satisfies

. As a consequence, the discretized population spike count satisfies  , where the Y

l are the counting variables obtained from the processes y

l(t) using a bin size h. As the event times t

j of z(t) follow a Poisson process and the subsequent amplitudes a

j are independent, the y

l(t) are independent Poisson processes. The rate ν

l of y

l(t) is given by ν

l = f

A(l)·ν (l = 1,2,...). Hence, the Y

l are Poisson variables with parameter ν

l

h. As a consequence, all cumulants of Y

l are identical and given by κ

m[Y

l] = ν

l

h (m = 1,2,...; Gardiner 2003). The scaling behavior of the cumulants

, where the Y

l are the counting variables obtained from the processes y

l(t) using a bin size h. As the event times t

j of z(t) follow a Poisson process and the subsequent amplitudes a

j are independent, the y

l(t) are independent Poisson processes. The rate ν

l of y

l(t) is given by ν

l = f

A(l)·ν (l = 1,2,...). Hence, the Y

l are Poisson variables with parameter ν

l

h. As a consequence, all cumulants of Y

l are identical and given by κ

m[Y

l] = ν

l

h (m = 1,2,...; Gardiner 2003). The scaling behavior of the cumulants  for all m (Mattner 1999) yields

for all m (Mattner 1999) yields

|

Using ν

l = f

A(l)·ν and  , we finally have

, we finally have

|

3 |

Equation (3) is the central equation of this study and requires a few more remarks. First, it implies that the first two cumulants of the population spike count, κ 1[Z] and κ 2[Z], are determined solely by the carrier rate ν and the first two moments of the amplitude distribution, μ 1[A] and μ 2[A]. As κ 1[Z] and κ 2[Z] determine firing rates and pairwise correlations in the population (Appendix B, Eqs. (24) and (26)), we conclude that all CPP models with identical carrier rate ν and identical μ 1[A] and μ 2[A] generate populations with identical rates and pairwise correlations. Differences in higher-order correlations can thus be modeled by choosing different higher moments for f A (see Section 2.4 for the precise relationship between the entries of the amplitude distribution and higher-order correlations in the population). This makes the CPP a very flexible and convenient model to generate artificial data sets with identical firing rates and pairwise correlations, yet different higher-order correlations (see Section 4 and Appendix B for examples, and Kuhn et al. 2003; Ehm et al. 2007; Staude et al. 2010 for alternative parametrizations).

Second, the moments of the strictly positive, integer-valued variable A increase with the order, i.e. satisfy μ m[A] ≤ μ m + 1[A] for m ≥ 1. By Eq. (3), this implies that also the cumulants of Z increase with the order, i.e. κ m[Z] ≤ κ m + 1[Z]. This is a reformulation of the fact that insertion of joint spikes as done in the CPP generates only positive correlations (e.g., Brette 2009; Johnson and Goodman 2008, Johnson and Goodman, unpublished manuscript), and it shows that certain combinations of cumulants cannot be realized by the CPP.

Terminology

The conceptual difference between the measured data (the counting variables X i and the complexity distribution f Z) and the parametric model that we assume to underlie this measurement (the CPP) is crucial for the remainder of this study. To illustrate this difference, note that f Z depends on the bin size h used in the discretization. Larger bin widths increase the probabilities for high complexities, while smaller bin widths increase the probability for empty bins. The parameters of the CPP, on the other hand, do not change with the bin size. For instance, if all events of z(t) have amplitude a j = 1, i.e. the amplitude distribution has a single peak at ξ = 1, the population consists of independent Poisson processes, irrespective of the bin size used for the analysis, or even the number of recorded neurons. In other words: patterns of complexity Z ≥ 2 can occur by chance, while events of amplitude ξ ≥ 2 do not occur by chance but imply correlations in the population. The order of the correlation, in turn, is determined by the amplitudes of the events in the corresponding CPP (see Appendix A for the proof):

Theorem 1

Let

be a compound Poisson process with amplitude distribution

f

A

, and let

be a compound Poisson process with amplitude distribution

f

A

, and let

be the vector of counting variables obtained from the x

i(t) with a bin width h

. Then the components of

X

have correlations of order m

if and only if f

A

assigns non-zero probabilities to amplitudes ≥ m.

be the vector of counting variables obtained from the x

i(t) with a bin width h

. Then the components of

X

have correlations of order m

if and only if f

A

assigns non-zero probabilities to amplitudes ≥ m.

The above theorem confirms the intuitive conception that, within the framework of the CPP, correlations of a certain order m require injected coincidences into at least m processes (events of amplitudes ≥ m). Also, a population with only pairwise but no higher-order correlations has events of maximal amplitude m = 2. Importantly, correlations in the above theorem are defined strictly on the basis of the discretized counting variables X i. As a consequence, they do not resolve (and do not depend on) the perfect temporal precision of the coincident events in the CPP: if the events of z(t) were copied into the individual processes with a temporal jitter that is small with respect to the bin size h, the correlations among the counting variables will hardly be affected (see Section 5.3.3 for a more detailed discussion). Note also that events of amplitude ξ induce not only correlations of order ξ, but also of orders < ξ.

Cumulant based inference of higher-order correlations (CuBIC)

This section describes our cumulant based inference procedure for higher-order correlations (CuBIC). The outcome of CuBIC is a lower bound  on the order of correlation in the spiking activity of large groups of simultaneously recorded neurons. As will be shown in Section 4, this lower bound can exceed the order of the cumulants that were estimated for the inference. Thereby, CuBIC can provide statistical evidence for large correlated groups without the discouraging requirements on sample size that direct tests for higher-order correlations have to meet. This is achieved by exploiting constraining relations among correlations of different orders. For illustration, consider as an example the extreme situation of 4 simultaneously recorded neurons, where all neuron pairs have a correlation coefficient of c = 1. As c = 1 implies identity for all pairs of spike trains, all four spike trains of this example must be identical (Fig. 2, left). In other words, a spike in one neuron implies joint spike events in all the other neurons. Thus, the data must have correlation of order 4.

on the order of correlation in the spiking activity of large groups of simultaneously recorded neurons. As will be shown in Section 4, this lower bound can exceed the order of the cumulants that were estimated for the inference. Thereby, CuBIC can provide statistical evidence for large correlated groups without the discouraging requirements on sample size that direct tests for higher-order correlations have to meet. This is achieved by exploiting constraining relations among correlations of different orders. For illustration, consider as an example the extreme situation of 4 simultaneously recorded neurons, where all neuron pairs have a correlation coefficient of c = 1. As c = 1 implies identity for all pairs of spike trains, all four spike trains of this example must be identical (Fig. 2, left). In other words, a spike in one neuron implies joint spike events in all the other neurons. Thus, the data must have correlation of order 4.

Fig. 2.

Strong pairwise correlations imply higher-order correlations. Raster plots show populations that have a single event amplitude that differs in the three panels (left: all events have amplitude 4, middle: amplitude 3, right: amplitude 2). Note that an increase in pairwise correlations in the right population can only be achieved by increasing the event amplitude and thereby the order of correlation. The plots thus illustrate the populations that are maximally correlated with correlations of order ≤ 4 (left), ≤ 3 (middle) and ≤ 2 (right)

The key observation of this example is that the order of correlation we inferred ( ) exceeds the order m of the measured correlations (here m = 2). CuBIC formalizes this example in the framework of the CPP, and generalizes it in two aspects:

) exceeds the order m of the measured correlations (here m = 2). CuBIC formalizes this example in the framework of the CPP, and generalizes it in two aspects:

Assume the correlation coefficients had been somewhat smaller than 1: do we still need correlation of order 4 to explain the measured pairwise correlation? Or would correlation of order 3 as in Fig. 2, middle, or even of order 2 as in Fig. 2, right, suffice to explain the measured correlations? In other words: What order of correlation is minimally required to explain the measured pairwise correlations?

Can we formulate a similar reasoning for measured correlations of higher order? What order of correlation is minimally required to explain the measured correlations of third (fourth,...) order?

The next section details our approach to answer the first question. The results are then generalized to answer the second question (Section 3.2). Finally, we explain how CuBIC combines the results to infer a lower bound for the order of correlation in a given data set (Section 3.3).

Testing pairwise correlations (m = 2)

We approach the first aspect with a hierarchy of statistical hypothesis tests, labeled by the integer ξ. For fixed ξ, the null hypothesis  states that the pairwise correlations (thus the superscript “2”) in the population are compatible with the assumption that there is no correlation beyond order ξ; the alternative

states that the pairwise correlations (thus the superscript “2”) in the population are compatible with the assumption that there is no correlation beyond order ξ; the alternative  states that correlation of order higher than ξ is necessary to explain the pairwise correlations. Rejection of e.g.

states that correlation of order higher than ξ is necessary to explain the pairwise correlations. Rejection of e.g.  in favor of

in favor of  thus implies the existence of correlation of at least order 5. The test statistics to decide between these alternatives is the second sample cumulant of the population spike count, and the compound Poisson process provides the framework to analytically derive the required confidence bounds.

thus implies the existence of correlation of at least order 5. The test statistics to decide between these alternatives is the second sample cumulant of the population spike count, and the compound Poisson process provides the framework to analytically derive the required confidence bounds.

The null hypothesis

The formulation of a null hypothesis requires a careful distinction between the random variable that describes the experiment, and the data sample that is tested against the hypothesis. For a fixed value of the test parameter ξ, this section formulates the null hypothesis  , using the random variable Z′ that describes the population spike count of a neuronal population. Section 3.1.2 explains how a given data sample {Z′1,...,Z′L} is tested against

, using the random variable Z′ that describes the population spike count of a neuronal population. Section 3.1.2 explains how a given data sample {Z′1,...,Z′L} is tested against  .

.

The null hypotheses  is based on the CPP model whose population spike count has the maximal second cumulant under the constraints that (a) the first cumulant equals that of a given population spike count Z′, and (b) the maximal order of correlation in the model is ξ. Using the amplitude distribution f

A to parametrize its correlation structure, this CPP model is the solution of the constrained maximization problem

is based on the CPP model whose population spike count has the maximal second cumulant under the constraints that (a) the first cumulant equals that of a given population spike count Z′, and (b) the maximal order of correlation in the model is ξ. Using the amplitude distribution f

A to parametrize its correlation structure, this CPP model is the solution of the constrained maximization problem

|

4 |

where ν and f

A are the CPP parameters that determine the population spike count Z. We rewrite Eq. (4) by observing that the second constraint ( ) together with Eq. (3) implies

) together with Eq. (3) implies  . With ν

l = f

A(l)·ν (Section 2.3), we thus have

. With ν

l = f

A(l)·ν (Section 2.3), we thus have

|

5 |

where the dot denotes the standard scalar product. Using Eq. (5) and the vector notation  and

and  , the maximization problem of Eq. (4) becomes

, the maximization problem of Eq. (4) becomes

|

6 |

In Eq. (6), both the function to maximize ( ) and the constraint (

) and the constraint ( ) depend linearly on the parameters

) depend linearly on the parameters  . Problems of this type, so-called Linear Programming Problems, are uniquely solvable, e.g. using the Simplex Method (Press et al. 1992, Chapter 10.8). The solution yields the upper bound for the second cumulant

. Problems of this type, so-called Linear Programming Problems, are uniquely solvable, e.g. using the Simplex Method (Press et al. 1992, Chapter 10.8). The solution yields the upper bound for the second cumulant  and the corresponding parameter vector

and the corresponding parameter vector  . The carrier rate and amplitude distribution of the CPP that maximizes Eq. (6) are then given by

. The carrier rate and amplitude distribution of the CPP that maximizes Eq. (6) are then given by  and

and  .

.

Assume that the combination of firing rates and pairwise correlations in the population can be realized with correlations of order ≤ ξ. Then, the second cumulant of its population spike count Z′ must be smaller than the upper bound  computed in the previous section. We thus formulate the null hypothesis

computed in the previous section. We thus formulate the null hypothesis

|

The alternative hypothesis

|

states that, within the framework of the CPP model, the pairwise correlations in the population imply the presence of correlation of order > ξ.

Test statistics and their distributions

The derivations in the previous section require the cumulants κ 1[Z′] and κ 2[Z′] of the random variable Z′. Given only a data sample {Z′1,...,Z′L} of size L, we estimate these quantities by the standard sample mean and (unbiased) sample variance (Stuart and Ord 1987)

|

The test of the data sample against  requires the distribution of the test statistics k

2 under the null hypothesis. To derive this distribution, recall that

requires the distribution of the test statistics k

2 under the null hypothesis. To derive this distribution, recall that  and

and  , where the κ

i[Z′] are the unknown cumulants of the variable Z′ that underlies the sample (Stuart and Ord 1987). The trick of CuBIC is to assume in

, where the κ

i[Z′] are the unknown cumulants of the variable Z′ that underlies the sample (Stuart and Ord 1987). The trick of CuBIC is to assume in  that Z′ is the population spike count of the CPP that solves Eq. (6) after the unknown cumulant κ

1[Z′] has been substituted with its estimate k

1. Under this assumption, all cumulants of Z′ can be computed by inserting the model parameters ν

* and

that Z′ is the population spike count of the CPP that solves Eq. (6) after the unknown cumulant κ

1[Z′] has been substituted with its estimate k

1. Under this assumption, all cumulants of Z′ can be computed by inserting the model parameters ν

* and  into Eq. (3), which yields

into Eq. (3), which yields

|

7 |

Given sample sizes of L > 10.000 (roughly corresponding to 10–100 s of data, see Section 4.2 and Fig. 6(d)), the distribution of k

2 under  is well approximated by a normal distribution. Taken together, under

is well approximated by a normal distribution. Taken together, under  the test statistics k

2 is normal with mean

the test statistics k

2 is normal with mean  and variance given by Eq. (7), such that the p-value for the test against

and variance given by Eq. (7), such that the p-value for the test against  is

is

|

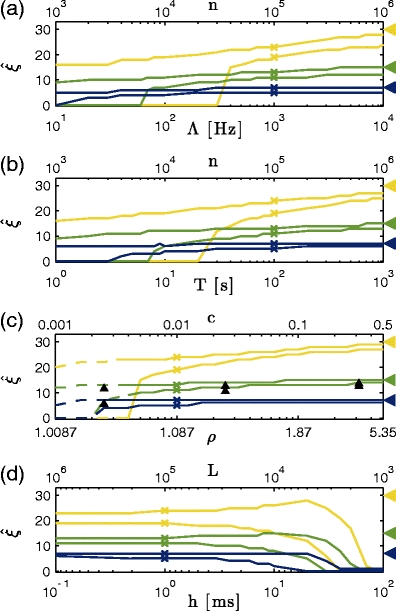

Fig. 6.

Parameter dependence of CuBIC for m = 3. Shown are the percentiles ξ

05 and ξ

95 (lower and upper curves of same color, respectively; see Fig. 5(b)), as a function of (a) the population firing rate Λ, (b) the duration of the experiment T, (c) the correlation strength ρ, and (d) the bin width h for data sets with correlation of maximal order ξ

syn = 7 (dark blue), ξ

syn = 15 (green) and ξ

syn = 30 (yellow). Crosses denote default parameter combinations (Λ = 103 Hz, T = 100 s, ρ = 1.087 and h = 1 ms) one of which is varied in the different panels. Additional x axes show corresponding values of the total spike count n = ΛT (a and b), the pairwise correlation coefficient c assuming a population of N = 100 neurons, N

C = 30 of which are homogeneously correlated (c), and the sample size  (d). Arrowheads on the right indicate ξ

syn, which is the optimal value for ξ

95. Data points for the dashed lines in (c) contain data sets were k

2 did not significantly exceed k

1 (compare Section 4.2.2). Upward arrowheads in (c) denote the percentiles for the parameter combinations of Fig. 5(b)

(d). Arrowheads on the right indicate ξ

syn, which is the optimal value for ξ

95. Data points for the dashed lines in (c) contain data sets were k

2 did not significantly exceed k

1 (compare Section 4.2.2). Upward arrowheads in (c) denote the percentiles for the parameter combinations of Fig. 5(b)

The rejection of the null hypothesis  for a given ξ implies that the pairwise correlations in the data are not compatible with the assumption that there is no correlation beyond order ξ. Thus, rejecting

for a given ξ implies that the pairwise correlations in the data are not compatible with the assumption that there is no correlation beyond order ξ. Thus, rejecting  implies that ξ + 1 is a lower bound for the order of correlation.

implies that ξ + 1 is a lower bound for the order of correlation.

Testing higher-order correlations (m > 2)

We now generalize the tests with measured pairwise correlations (m = 2) to exploit also estimated correlations of higher order (m > 2). The difference to the tests with m = 2 is that the upper bound for the mth cumulant involves all cumulants up to order m − 1. The generalization of the maximization problem (Eq. (4)) reads

|

8 |

where, as before, the κ i[Z′] are the cumulants of the random variable Z′. Using the ν-parametrization of Eq. (5), we can rewrite Eq. (8) as the Linear Programming Problem

|

9 |

where Ξm − 1 is a (ξ×m − 1)-dimensional coefficient matrix with entries  , and

, and  is the column-vector of the first m − 1 cumulants of Z′. Solving Eq. (9) yields both the maximal mth cumulant

is the column-vector of the first m − 1 cumulants of Z′. Solving Eq. (9) yields both the maximal mth cumulant  and the rate vector

and the rate vector  , which again can be used to compute the corresponding model parameters ν

* and

, which again can be used to compute the corresponding model parameters ν

* and  .

.

In direct analogy to the case m = 2, the (m,ξ)-null hypothesis  states that correlation of orders 1,2,...,m are compatible with the assumption that there is no correlation beyond order ξ. This implies that κ

m[Z′] falls below the upper bound

states that correlation of orders 1,2,...,m are compatible with the assumption that there is no correlation beyond order ξ. This implies that κ

m[Z′] falls below the upper bound  , and we define

, and we define

|

To test a sample {Z′1,...,Z′L} against  , we estimate correlations of order m by the mth sample cumulant of the population spike count, the so-called the mth k-statistics k

m (Stuart and Ord 1987; the sample mean and unbiased sample variance defined above are the first two k-statistics). And again, we assume that Z′ is the population spike count of the CPP model that solves Eq. (4) after the unknown κ

i[Z′] have been replaced by the estimates k

i (i = 1,...,m − 1). Then, the test statistics k

m is normally distributed with mean

, we estimate correlations of order m by the mth sample cumulant of the population spike count, the so-called the mth k-statistics k

m (Stuart and Ord 1987; the sample mean and unbiased sample variance defined above are the first two k-statistics). And again, we assume that Z′ is the population spike count of the CPP model that solves Eq. (4) after the unknown κ

i[Z′] have been replaced by the estimates k

i (i = 1,...,m − 1). Then, the test statistics k

m is normally distributed with mean  and variance

and variance  , where expressions for

, where expressions for  can be found in the literature (Stuart and Ord 1987). The p-value of

can be found in the literature (Stuart and Ord 1987). The p-value of  is thus given by

is thus given by

|

10 |

Note that after substituting the true cumulant vector  by its estimate

by its estimate  in Eq. (9), the resulting constraint

in Eq. (9), the resulting constraint  consists of m − 1 equations for the ξ positive parameters ν

1,...,ν

ξ. Unfortunately, there can be combinations of estimated cumulants for which these equations cannot be solved. In this case, Eq. (9) does not posses a solution, and the corresponding null hypothesis cannot be tested (see also Section 3.3).

consists of m − 1 equations for the ξ positive parameters ν

1,...,ν

ξ. Unfortunately, there can be combinations of estimated cumulants for which these equations cannot be solved. In this case, Eq. (9) does not posses a solution, and the corresponding null hypothesis cannot be tested (see also Section 3.3).

Computing the lower bound

In the preceding section, CuBIC was presented as a collection of hypothesis tests  , labeled by the indices m (the order of the estimated cumulant) and ξ (the maximal order of correlation in the null). We now combine these tests to infer a lower bound

, labeled by the indices m (the order of the estimated cumulant) and ξ (the maximal order of correlation in the null). We now combine these tests to infer a lower bound  for the order of correlation in a given data set. To do so, recall that rejecting

for the order of correlation in a given data set. To do so, recall that rejecting  for given m and ξ implies that the combination of the first m cumulants requires correlation of order > ξ. As a consequence, every rejected hypothesis

for given m and ξ implies that the combination of the first m cumulants requires correlation of order > ξ. As a consequence, every rejected hypothesis  implies that ξ + 1 is a lower bound for the highest order of correlation in the data. The question thus is: which of these bounds should we use?

implies that ξ + 1 is a lower bound for the highest order of correlation in the data. The question thus is: which of these bounds should we use?

Evidently, we aim to infer the highest order of correlation that is present in the data. Hence, the objective is to find the maximum of all the lower bounds that were obtained from the hierarchy of tests. We thus aim for the pair (m,ξ) with the highest value of ξ such that the corresponding null hypothesis  is rejected.

is rejected.

A conceptual algorithm for this search is presented in Fig. 3. It consists of two nested loops: for a fixed order of the estimated cumulant m, the inner loop searches the highest ξ for which  is rejected; the outer loop iterates over subsequent orders m. The free parameters of the algorithm are the test level α, and, to ensure termination of the loops, upper bounds for the cumulant (m

max) and the maximal order of correlation assumed in the null (ξ

max; see Section 5 for their choice). After initializing the test variables (m = 2, ξ = 1,

is rejected; the outer loop iterates over subsequent orders m. The free parameters of the algorithm are the test level α, and, to ensure termination of the loops, upper bounds for the cumulant (m

max) and the maximal order of correlation assumed in the null (ξ

max; see Section 5 for their choice). After initializing the test variables (m = 2, ξ = 1,  ), we estimate the first m cumulants from the data by computing the corresponding k-statistics. Next, we check if Eq. (9) is solvable for the current values of m and ξ (yellow box). This check consists of two steps. The first step checks if the first m − 1 estimated cumulants increase with order m, a requirement of the CPP model assumed to underlie the data (left rhomb in yellow box; compare last paragraph of Section 2.3). If this is not the case, then k

1 ≤ k

2 ≤ ... ≤ k

m′ − 1 is false for all m′ ≥ m, which implies that Eq. (9) cannot be solved for m′ ≥ m. If the solution, i.e. the maximal cumulant

), we estimate the first m cumulants from the data by computing the corresponding k-statistics. Next, we check if Eq. (9) is solvable for the current values of m and ξ (yellow box). This check consists of two steps. The first step checks if the first m − 1 estimated cumulants increase with order m, a requirement of the CPP model assumed to underlie the data (left rhomb in yellow box; compare last paragraph of Section 2.3). If this is not the case, then k

1 ≤ k

2 ≤ ... ≤ k

m′ − 1 is false for all m′ ≥ m, which implies that Eq. (9) cannot be solved for m′ ≥ m. If the solution, i.e. the maximal cumulant  and the model parameters ν

* and

and the model parameters ν

* and  , are not available, however, the corresponding p-values (Eq. (10)) cannot be computed. In this case, no hypothesis

, are not available, however, the corresponding p-values (Eq. (10)) cannot be computed. In this case, no hypothesis  with m′ ≥ m can be tested, and the procedure is terminated. If the first m − 1 estimated cumulants are in principle compatible with the CPP, we check in the second step if the current value of ξ can solve Eq. (9) (right rhomb in yellow box). If this is not the case, ξ is increased by 1 until either Eq. (9) can be solved, or ξ reaches its upper bound ξ

max. In the former case, the data are tested against

with m′ ≥ m can be tested, and the procedure is terminated. If the first m − 1 estimated cumulants are in principle compatible with the CPP, we check in the second step if the current value of ξ can solve Eq. (9) (right rhomb in yellow box). If this is not the case, ξ is increased by 1 until either Eq. (9) can be solved, or ξ reaches its upper bound ξ

max. In the former case, the data are tested against  (blue box), in the latter case the test is skipped. At rejection of

(blue box), in the latter case the test is skipped. At rejection of  (rightward arrow at the box p

m,ξ < α) we set

(rightward arrow at the box p

m,ξ < α) we set  and, unless ξ reached the upper bound ξ

max, repeat the inner loop with ξ set to ξ + 1. The loop terminates with

and, unless ξ reached the upper bound ξ

max, repeat the inner loop with ξ set to ξ + 1. The loop terminates with  , which is the largest lower bound for the current value of m. As we reject the “zeroth” hypothesis

, which is the largest lower bound for the current value of m. As we reject the “zeroth” hypothesis  by convention (every data set has correlations of order > 0), this holds even if the tests for the current value of m were skipped. The inner loop is repeated with new m set to m + 1, until m reaches the upper bound m

max. Finally, the lower bounds obtained for the different values of m are compared, and their maximum is returned as the absolute lower bound

by convention (every data set has correlations of order > 0), this holds even if the tests for the current value of m were skipped. The inner loop is repeated with new m set to m + 1, until m reaches the upper bound m

max. Finally, the lower bounds obtained for the different values of m are compared, and their maximum is returned as the absolute lower bound  . A MatLab-implementation of the proposed algorithm is available upon request.

. A MatLab-implementation of the proposed algorithm is available upon request.

Fig. 3.

Procedure to infer the highest lower bound  for the order of correlation in a given data set. The pair (m,ξ) with the highest ξ such that the corresponding null hypothesis

for the order of correlation in a given data set. The pair (m,ξ) with the highest ξ such that the corresponding null hypothesis  is rejected is found by two nested loops. For any given m, the inner loop over ξ increases the lower bound

is rejected is found by two nested loops. For any given m, the inner loop over ξ increases the lower bound  , whenever Eq. (9) can be solved (right rhomb in upper yellow box) and the corresponding hypothesis is rejected (p

m,ξ < α). This loop terminates (p

m,ξ ≥ α or ξ ≤ ξ

max) with

, whenever Eq. (9) can be solved (right rhomb in upper yellow box) and the corresponding hypothesis is rejected (p

m,ξ < α). This loop terminates (p

m,ξ ≥ α or ξ ≤ ξ

max) with  , which is the highest lower bound for the current value of m. The outer loop runs over the order of estimated cumulants m. The procedure terminates if the first m − 1 estimated cumulants violate the constraints of the CPP model (left rhomb in upper yellow box), or if the the order of the cumulant m reached the predefined upper bound m

max (rhomb below lower blue box). Finally, the bounds for different m are compared and their maximum

, which is the highest lower bound for the current value of m. The outer loop runs over the order of estimated cumulants m. The procedure terminates if the first m − 1 estimated cumulants violate the constraints of the CPP model (left rhomb in upper yellow box), or if the the order of the cumulant m reached the predefined upper bound m

max (rhomb below lower blue box). Finally, the bounds for different m are compared and their maximum  is returned

is returned

Simulation results

Illustration

Before we present a systematic analysis of the proposed procedure in Section 4.2, we illustrate CuBIC’s sensitivity by a comparison of three sample data sets (Fig. 4). All three data sets are based on the same number of neurons (N = 100) with identical firing rates (λ = 10 Hz) and pairwise correlations (c = 0.01 in N

C = 30 and c = 0 in the remaining 70 neurons). The difference between the data sets lies solely in their higher-order correlation structure, i.e. their maximal order of correlation (Fig. 4, top panels). All sets have amplitudes at ξ = 1 that generate independent “background spikes”. Correlations are induced by additional events of amplitudes ξ

syn > 1 that differ across data sets: ξ

syn = 2 in Set1 (left), ξ

syn = 7 in Set2 (middle), and ξ

syn = 15 in Set3 (right). Thus, Set1 has correlation of order 1 and 2, Set2 has correlations up to order 7, and Set3 has correlations up to order 15. The identical pairwise correlations in the three data sets are achieved by adjusting the rate  of the higher-order events (see Appendix B for the relationship between the model parameters ν,f

A and the population statistics N,N

C,λ and c). Test parameters were set to ξ

max = 15 and m

max = 4.

of the higher-order events (see Appendix B for the relationship between the model parameters ν,f

A and the population statistics N,N

C,λ and c). Test parameters were set to ξ

max = 15 and m

max = 4.

The similarity of the raster displays and population spike counts (Fig. 4, 2nd and 3rd from top) of the three data sets may illustrate that such standard visualization methods cannot reveal the differences in the higher-order properties of the data sets. Larger probabilities for patterns of high complexity induced by the higher-order correlations present in Set2 and Set3 are visible in the complexity distributions (third row of panels) only when plotted on a logarithmic scale (green lines). The low rates of the higher-order events imposed by the small pairwise correlations (ν 7 = 2.07 Hz in Set2, ν 15 = 0.41 Hz in Set3) makes their detection in the three distributions (bars) very difficult on a linear scale.

The identical pairwise correlations in all three data sets are reflected in identical results for tests with m = 2. For all data sets,  is rejected (p < 0.05, indicated by red marks) only for ξ = 1, implying that the pairwise correlations are significant and events of amplitude 1 are not enough to explain the data. As

is rejected (p < 0.05, indicated by red marks) only for ξ = 1, implying that the pairwise correlations are significant and events of amplitude 1 are not enough to explain the data. As  is retained for ξ > 1 in all data sets (p > 0.05), the lower bound for m = 2 is

is retained for ξ > 1 in all data sets (p > 0.05), the lower bound for m = 2 is  (see Fig. 3), i.e. the tests with m = 2 do not imply correlation of order ≥ 2 in any of the data sets.

(see Fig. 3), i.e. the tests with m = 2 do not imply correlation of order ≥ 2 in any of the data sets.

Test results with m = 3 differ strongly for the three data sets (Fig. 4, lower panels, right graphs). For Set1, only  is rejected and all

is rejected and all  for ξ ≥ 2 are retained. Hence

for ξ ≥ 2 are retained. Hence  . For Set2,

. For Set2,  is rejected for ξ = 1,...,6, yielding

is rejected for ξ = 1,...,6, yielding  , while for Set3 the rejection of all null-hypotheses for ξ ≤ 12 yields

, while for Set3 the rejection of all null-hypotheses for ξ ≤ 12 yields  . In all tests with m = 4 (data not shown), the smallest values for ξ that solved Eq. (9) yielded non-significant p values (for Set1 p

4,2 = 0.5, for Set2 p

4,9 = 0.8, for Set3 p

4,16 = 0.67). Hence, no hypothesis with m = 4 was rejected except for

. In all tests with m = 4 (data not shown), the smallest values for ξ that solved Eq. (9) yielded non-significant p values (for Set1 p

4,2 = 0.5, for Set2 p

4,9 = 0.8, for Set3 p

4,16 = 0.67). Hence, no hypothesis with m = 4 was rejected except for  which is rejected by convention. Thus,

which is rejected by convention. Thus,  in all data sets. For the total lower bounds

in all data sets. For the total lower bounds  , we thus obtain

, we thus obtain  for Set1,

for Set1,  for Set2, and

for Set2, and  for Set3.

for Set3.

The lower bound corresponds to the maximal order of correlation in Set1 (ξ syn = 2) and Set2 (ξ syn = 7). Only for Set3 the lower bound falls short of the true maximum by 2 (ξ syn = 15), but nevertheless indicates correlations of higher order than in Set2. Taken together, the three examples illustrate that CuBIC reliably detects differences in higher-order statistics, even if firing rates (here λ = 10 Hz) and very small pairwise correlations (here c = 0.01 in 30 out of 100 neurons) are identical.

Parameter dependence of test performance

Several parameters are likely to influence CuBIC’s performance. For instance, the number of recorded neurons, N, the collection of firing rates, λ

1,...,λ

N, the duration of the experiment, T, and the bin size, h, influence the amount of available data and can thus be expected to effect test results. Also the correlation structure, i.e. the rate and the order of injected coincidences, parametrized by the N − 1 probabilities of the amplitude distribution f

A, is likely to affect the performance of the method. However, some of the parameters mentioned above are in fact redundant with respect to the test statistics used here, i.e. the k-statistics of the population spike count Z. For instance, Z depends only on the summed firing rate  , but not on the precise combination of the rates of individual neurons. To analyze the parameter dependence of CuBIC (Section 4.2.3), we focus on parameters that are relevant in experimental data and avoid the above-mentioned redundancies. Furthermore, we restrict our analysis to tests with the third cumulant, thus study the inner loop in Fig. 3 for m = 3. To keep notation simple, we drop the subscript 3 and write

, but not on the precise combination of the rates of individual neurons. To analyze the parameter dependence of CuBIC (Section 4.2.3), we focus on parameters that are relevant in experimental data and avoid the above-mentioned redundancies. Furthermore, we restrict our analysis to tests with the third cumulant, thus study the inner loop in Fig. 3 for m = 3. To keep notation simple, we drop the subscript 3 and write  in the remainder of this section. The upper bound for ξ was ξ

max = 30 in all simulations.

in the remainder of this section. The upper bound for ξ was ξ

max = 30 in all simulations.

Parameters

We investigate the performance of CuBIC with respect to five parameters: the duration of the experiment, T, the total firing rate of the population,  , the bin width used to discretize the data, h, and two parameters, ξ

syn and ρ, that characterize the correlation structure (amplitude distribution, f

A) of the data. We here consider amplitude distributions that consist of two isolated peaks only: a “background-peak” at ξ = 1 and a second peak at ξ = ξ

syn that determines the maximal order of correlation in the data (see for examples Fig. 4, top row). The relative height of the two peaks is parametrized by the moments ratio

, the bin width used to discretize the data, h, and two parameters, ξ

syn and ρ, that characterize the correlation structure (amplitude distribution, f

A) of the data. We here consider amplitude distributions that consist of two isolated peaks only: a “background-peak” at ξ = 1 and a second peak at ξ = ξ

syn that determines the maximal order of correlation in the data (see for examples Fig. 4, top row). The relative height of the two peaks is parametrized by the moments ratio

|

11 |

where  is the ith moment of A.

is the ith moment of A.

Substituting the moments μ

i[A] in Eq. (11) by the cumulants of Z via Eq. (3) shows that ρ equals the Fano Factor of the population spike count, i.e.  (see e.g., Kumar et al. 2008; Kriener et al. 2008). This interpretation is valid for arbitrary amplitude distributions, and provides a method to estimate ρ from data. For a more intuitive interpretation of ρ, consider a population of N neurons with identical firing rates, where a sub-population of N

C neurons forms a homogeneously correlated subgroup, while the remaining N − N

C neurons fire independently (compare rasters displays in Fig. 4). In this case ρ relates to the (average) pairwise count correlation coefficient c of the correlated subgroup

(see e.g., Kumar et al. 2008; Kriener et al. 2008). This interpretation is valid for arbitrary amplitude distributions, and provides a method to estimate ρ from data. For a more intuitive interpretation of ρ, consider a population of N neurons with identical firing rates, where a sub-population of N

C neurons forms a homogeneously correlated subgroup, while the remaining N − N

C neurons fire independently (compare rasters displays in Fig. 4). In this case ρ relates to the (average) pairwise count correlation coefficient c of the correlated subgroup

|

12 |

For a derivation of this relation see Appendix B, Eq. (29). In case of a completely homogeneous population with N = N

C, this simplifies to  (compare e.g., Kumar et al. 2008; Kriener et al. 2008). In either case, the correlation parameter ρ determines the effect of higher-order events on the pairwise correlations in the population.

(compare e.g., Kumar et al. 2008; Kriener et al. 2008). In either case, the correlation parameter ρ determines the effect of higher-order events on the pairwise correlations in the population.

Quantification of test performance

We asses CuBIC’s performance by Monte-Carlo techniques. That is, we compute the lower bound for the order of correlation  (Figs. 3 and 5(a)) for each of 1000 data sets that are simulated from the CPP model with identical parameter combinations. The resulting (estimated) distribution

(Figs. 3 and 5(a)) for each of 1000 data sets that are simulated from the CPP model with identical parameter combinations. The resulting (estimated) distribution  then indicates the range of lower bounds for this particular parameter combination. We thus study the parameter dependence of CuBIC’s performance by the parameter dependence of the distribution of

then indicates the range of lower bounds for this particular parameter combination. We thus study the parameter dependence of CuBIC’s performance by the parameter dependence of the distribution of  (Fig. 5(b)). For the specific parameter combination of Fig 5(a), for instance, lower bounds fall almost exclusively between

(Fig. 5(b)). For the specific parameter combination of Fig 5(a), for instance, lower bounds fall almost exclusively between  and

and  (Fig. 5(b), bottom panel). Increasing the correlation parameter ρ gradually sharpens and shifts

(Fig. 5(b), bottom panel). Increasing the correlation parameter ρ gradually sharpens and shifts  to higher values of

to higher values of  (Fig. 5(b)). CuBIC performs optimally if the lower bound corresponds to the maximal order of correlation in all Monte-Carlo simulations, i.e. if

(Fig. 5(b)). CuBIC performs optimally if the lower bound corresponds to the maximal order of correlation in all Monte-Carlo simulations, i.e. if  for all data sets. In this case,

for all data sets. In this case,  is a delta-peak located at ξ

syn (Fig. 5(b), top panel).

is a delta-peak located at ξ

syn (Fig. 5(b), top panel).

Fig. 5.

Quantification of test performance. (a) p-values for tests against  and the resulting lower bound for the order of correlation

and the resulting lower bound for the order of correlation  (here

(here  ) for one data set (parameters: ξ

syn = 15, Λ = 103 Hz, T = 100 s, ρ = 1.02 and h = 1 ms). Red filled circles denote rejected hypotheses, i.e. p-values below 0.05. (b) Three estimated distributions of lower bounds

) for one data set (parameters: ξ

syn = 15, Λ = 103 Hz, T = 100 s, ρ = 1.02 and h = 1 ms). Red filled circles denote rejected hypotheses, i.e. p-values below 0.05. (b) Three estimated distributions of lower bounds  , each obtained via Monte-Carlo simulations of 1000 data sets with identical parameter combinations. Parameters as in (a), only for different values of the correlation parameter (bottom: ρ = 1.02, middle: ρ = 1.2; top: ρ = 3.75). The two percentiles

, each obtained via Monte-Carlo simulations of 1000 data sets with identical parameter combinations. Parameters as in (a), only for different values of the correlation parameter (bottom: ρ = 1.02, middle: ρ = 1.2; top: ρ = 3.75). The two percentiles  and

and  are marked by arrowheads (see text for interpretation), also at the corresponding parameter values in Fig. 6(c). Observe the shift and sharpening of

are marked by arrowheads (see text for interpretation), also at the corresponding parameter values in Fig. 6(c). Observe the shift and sharpening of  towards the maximal order of correlation in the data ξ

syn = 15 (dashed line) for increasing ρ

towards the maximal order of correlation in the data ξ

syn = 15 (dashed line) for increasing ρ

To further reduce complexity, we will discuss the parameter dependence of  by means of the two percentiles (black triangles in Fig. 5(b))

by means of the two percentiles (black triangles in Fig. 5(b))

|

CuBIC performs optimally if  is a delta peak as in Fig. 5(b), top panel, i.e. if ξ

05 + 1 = ξ

syn = ξ

95. More generally, a value of ξ

05 ≫ 0 indicates that CuBIC reliably infers the existence of higher-order correlations (

is a delta peak as in Fig. 5(b), top panel, i.e. if ξ

05 + 1 = ξ

syn = ξ

95. More generally, a value of ξ

05 ≫ 0 indicates that CuBIC reliably infers the existence of higher-order correlations ( in 95% of all cases), while a value of ξ

95 ≤ ξ

syn guarantees that the actual order is not overestimated (

in 95% of all cases), while a value of ξ

95 ≤ ξ

syn guarantees that the actual order is not overestimated ( in less than 5% of all cases, no false positives).

in less than 5% of all cases, no false positives).

As mentioned before (Section 3.3), certain combinations of sample cumulants, e.g. k

2 < k

1, represent untestable data sets and yield lower bounds of  . To avoid border effects for extremely small pairwise correlations (ρ < 1.05), we set

. To avoid border effects for extremely small pairwise correlations (ρ < 1.05), we set  not only if k

2 < k

1 but also if k

2 does not significantly exceed k

1, i.e. if

not only if k

2 < k

1 but also if k

2 does not significantly exceed k

1, i.e. if  is retained (marked as dotted lines in Fig 6(c)).

is retained (marked as dotted lines in Fig 6(c)).

Results

Figure 6 shows the dependence of CuBIC’s performance on the population firing rate Λ (Fig. 6(a)), the duration of the experiment T (Fig. 6(b)), the correlation strength (population Fano Factor) ρ (Fig. 6(c)) and the bin width h (Fig. 6(d)) for different values of ξ syn (crosses in Fig. 6(a–d) denote the default parameters that are fixed while only one of them is varied).

Changes in the population firing rate Λ, the duration of the experiment T, and the correlation strength ρ have qualitatively very similar effects on the performance (Fig. 6(a), (b), and (c), respectively). For all analyzed values of ξ

syn (dark blue, green, and yellow lines) and small values of either of the parameters, i.e. Λ = 10 Hz (Fig. 6(a)), T = 1 s (Fig. 6(b)) or ρ = 1.0087 (Fig. 6(c)), the distributions of lower bounds  extend from ξ

05 = 0 (lower lines) to ξ

95 < ξ

syn (upper lines below colored triangles). Hence, lower bounds might not exceed the trivial value of

extend from ξ

05 = 0 (lower lines) to ξ

95 < ξ

syn (upper lines below colored triangles). Hence, lower bounds might not exceed the trivial value of  for such small parameter values. Increasing either of the parameters gradually shifts

for such small parameter values. Increasing either of the parameters gradually shifts  , i.e. ξ

05 and ξ

95, to higher values of

, i.e. ξ

05 and ξ

95, to higher values of  , thus indicating improved performance. The exact quality of the performance, captured by the width of

, thus indicating improved performance. The exact quality of the performance, captured by the width of  , i.e. the distance between ξ

05 and ξ

95, and in particular its difference from ξ

syn (colored triangles, compare also Fig. 5(b)), depends crucially on the order of correlation ξ

syn present in the data.

, i.e. the distance between ξ

05 and ξ

95, and in particular its difference from ξ

syn (colored triangles, compare also Fig. 5(b)), depends crucially on the order of correlation ξ

syn present in the data.

For ξ

syn = 7 (dark blue lines), CuBIC performs optimally (ξ

05 + 1 = 7 = ξ

95, compare Fig. 5(b)) for experiment durations of T > 100 s (Fig. 6(b)) and a wide range population Fano Factors (ρ ≥ 1.17, Fig. 6(c)). Such optimality is not guaranteed for the analyzed range of the population firing rate Λ, although population rates above Λ = 400 Hz yield a lower percentile of ξ

05 = 5, indicating close-to-optimal performance ( in 95% of all cases, Fig. 6(a)). Smaller values of either of the parameters shift

in 95% of all cases, Fig. 6(a)). Smaller values of either of the parameters shift  to lower values, indicating impaired performance. Nevertheless, as the lower percentile ξ

05 is considerably larger than zero even for population rates as low as Λ = 20 Hz, experiment durations of T = 6 s and population Fano Factors of ρ = 1.02, CuBIC reliably detects the presence of higher-order correlations for a wide range of parameter combinations.

to lower values, indicating impaired performance. Nevertheless, as the lower percentile ξ

05 is considerably larger than zero even for population rates as low as Λ = 20 Hz, experiment durations of T = 6 s and population Fano Factors of ρ = 1.02, CuBIC reliably detects the presence of higher-order correlations for a wide range of parameter combinations.

In the other extreme, where the same pairwise correlations (identical value of ρ) are realized by correlations of order ξ

syn = 30 (yellow lines),  falls short of its optimum (ξ

05 + 1 = 30 = ξ

95, see Fig. 5(b), top panel) even for high values of all investigated parameters, i.e. population rates of Λ = 104 Hz, experiment durations of T = 103 s and correlation strengths of ρ = 5.35 (Fig. 6(a), (b) and (c), respectively). Note, however, that also here ξ

05 ≫ 0 even for moderate values of Λ, T and ρ, implying that the presence of higher-order correlations is reliably detected, albeit not their actual order. For the default values Λ = 103 Hz, T = 100 s and ρ = 1.087 (yellow crosses in Fig. 6(a–d)), for instance, lower bounds for ξ

syn = 30 fall between

falls short of its optimum (ξ

05 + 1 = 30 = ξ

95, see Fig. 5(b), top panel) even for high values of all investigated parameters, i.e. population rates of Λ = 104 Hz, experiment durations of T = 103 s and correlation strengths of ρ = 5.35 (Fig. 6(a), (b) and (c), respectively). Note, however, that also here ξ

05 ≫ 0 even for moderate values of Λ, T and ρ, implying that the presence of higher-order correlations is reliably detected, albeit not their actual order. For the default values Λ = 103 Hz, T = 100 s and ρ = 1.087 (yellow crosses in Fig. 6(a–d)), for instance, lower bounds for ξ

syn = 30 fall between  and

and  in 90% of the analyzed data sets (ξ

05 = 19, ξ

95 = 24).

in 90% of the analyzed data sets (ξ

05 = 19, ξ

95 = 24).

Test performance for ξ

syn = 15 (green lines) is somewhere in between the often optimal results for ξ

syn = 7 and the more indicative results for ξ

syn = 30. In short, optimal performance is achieved only for high population Fano Factors (ρ ≥ 3.75, rightmost black triangle in Fig. 6(c)), while the presence of higher-order correlations is reliably detected ( ) for a wide range of parameters (Λ > 70 Hz, Fig. 6(a), T ≥ 80 s, Fig. 6(b), and ρ ≥ 1.02 Hz, Fig. 6(c)).

) for a wide range of parameters (Λ > 70 Hz, Fig. 6(a), T ≥ 80 s, Fig. 6(b), and ρ ≥ 1.02 Hz, Fig. 6(c)).

The qualitative similarity between Fig. 6(a) and (b) result from the identical effect of the varied parameters, Λ and T, on the expected spike count n = ΛT (Fig. 6(a), (b), top x axis). As n affects the quality of the estimators k i , both Λ and T influence test results in a similar manner. The similar ρ-dependence results from the fact that increasing ρ increases the probability for high-amplitude events f A(ξ syn), which simplifies their detection (Fig. 6(c)).

Changes in the bin width h (Fig. 6(d)) affect CuBIC’s performance for all values of ξ

syn in a very similar way. Increasing h decreases the lower percentile from ξ

05 ≫ 0 at h = 0.1 ms to ξ

05 = 0 for h = 100 ms, irrespective of ξ

syn. The upper percentiles ξ

95 (upper lines) can even show non-monotonic behavior: for ξ

syn = 15 (green) and ξ

syn = 30 (yellow), ξ